Aboriginal

Aborigines ( English [ ˌæbəˈɹɪdʒɪniːz ], "native people") is a common collective name for the indigenous peoples of Australia . Their ancestors settled the continent from the north about 40,000 to 60,000 years ago. Aborigines are not a single people , but consist of many peoples, tribes or clans with often very different customs and languages: Depending on the definition and source, before the arrival of the British there were around 200 to 700 different tribes of the Aborigines , who mainly acted as hunters and gathererslived With the arrival of the Europeans from 1788 onwards, their number fell from an estimated 300,000 to 1,000,000 inhabitants to 60,000 in 1920, mainly due to imported diseases , but also due to violent conflicts with the settlers over land rights. About three quarters of the 464,000 Aborigines now live in cities and have largely adapted to the modern way of life, as the authorities in Australia pursued an, often violent, assimilation policy for decades . Most likely, the Aboriginal traditions have been preserved in the Northern Territory , where Europeans settled late. There they live among themselves in most places, which is why almost 60% of the Aborigines speak an indigenous language ( Australian languages ) at home.

Surname

The word Aborigine (from the Latin ab origine "from the beginning") generally means native people in English ; it was originally the name for the indigenous people in Latium ( Aborigines (Italy) ), a region in central Italy . As a name specifically for the Aborigines of Australia, it was first documented in writing in 1803; now considered Aborigines in English as derogatory and is Aboriginal replaced. Aborigines usually describe themselves in their respective languages, for example Koori in southeast Australia or Anangu in the center. In English they call themselves black fellas . The German language continues to use the term Aboriginal.

In German usage, the term Aborigines is usually understood to mean all native inhabitants of the continent, while in Australia a distinction is made between Aborigines and the Torres Strait Islanders , the original inhabitants of the islands in the Torres Strait in the strait between the Australian continent and New Guinea . In the local language one speaks of the Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders , First Australians or Indigenous People , if the entirety of the native inhabitants of the state of Australia and their descendants are to be referred to.

The Aborigines of Australia used to be called Australnegers in German-speaking countries. This term , which is mostly considered racist today, comes from the racial theories that were widespread and influential, especially in the 19th and into the middle of the 20th century, they are now considered outdated and scientifically no longer tenable.

A person is defined as an Aboriginal when he or she is a descendant of Aboriginal people , describes himself as an Aboriginal , and is accepted as such by the community in which he lives.

Cultural areas

Due to the common lineage of the Australian population , the isolation lasting at least 35,000 years and the diverse common cultural characteristics, Australia is considered to be a cultural area in its own right on a global scale .

Based on the work of Nicolas Peterson, the Australian ethnic groups were further subdivided into another 17 cultural areas. Peterson's work was based on the main water routes and their course: He postulated that the groups of Aborigines lived along the water sources, whereby there were interrelationships between the groups along the water courses and there was thus a cultural exchange, combined with a relative cultural homogeneity, came. In contrast, the areas between the watercourses formed natural barriers because of the water and food shortages, so that relationships with people in other river systems were less frequent.

The largest cultural area in terms of area is the desert cultural area , which covers about 40% of the country and includes the arid parts of the country with the Simpson Desert , Gibson Desert , the Great Sand Desert and several smaller deserts.

history

prehistory

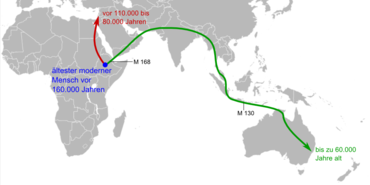

The time when the indigenous population reached Australia is not clear. Mitochondrial DNA comparisons (mtDNA) suggest that Aboriginal descendants of humans were one of the first waves of emigration from Africa . These ancestors left Africa 100,000 to 130,000 years ago to spread across Europe , Asia and along the coast of Southeast Asia to Australia.

David Reich (2010) from Harvard University , in collaboration with Mark Stoneking (1997) from the team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, also found genetic evidence that the Aborigines and smaller scattered groups of people in Southeast Asia, so-called Negrito peoples , like the Mamanwa in the Philippines , also have DNA from the Denisova people . However, not all Negrito peoples have DNA from the Denisova people; the Onge , natives of the island of Little Andaman , and the Malaysian Jehai , for example, have been found to have no traceable Denisovan genetic make-up. These data have been interpreted to mean that the gene flow may have occurred in mainland Southeast Asia, and suggest that the Denisova people were once widespread in East Asia.

At that time, Australia was part of the Sahul continent and connected to New Guinea by a land bridge. A land bridge to the Asian mainland never existed, so that settlement of Greater Australia would not have been possible without crossing the Wallacea Sea. This would not have been possible by swimming, and since the invention of seaworthy boats over 60,000 years ago is considered very unlikely, a very early settlement of Australia is largely rejected. Nonetheless, some assume a first, very early wave of immigration from people who were almost completely extinct due to the Toba catastrophe about 75,000 years ago, which is why Aborigines are only genetically related to the Papuan peoples in the mountains of New Guinea and some Indian people Ethnic groups like the Veddas . The rest of Asia was repopulated by a second wave of emigration from Africa.

The most common period for the arrival of the Aborigines is between 40,000 and 50,000 BC. Called BC. The somewhat more precise date of 48,000 BC. BC is based on measurements of settlements in Northern Australia using thermoluminescence dating . Radiocarbon dating has been used to date many other sites to 38,000 B.C. Measured. These values are doubtful, since the radiocarbon method can only measure well for up to 30,000 years.

Alan Cooper's working group carried out a large-scale study of the mitochondrial DNA of 111 Australian aborigines, which had been stored and made available by the University of Adelaide with the consent of the participants from archive material from the period from 1920 to 1970 . It was confirmed that immigration from Asia began around 50,000 years ago. The routes of propagation, according to Cooper et al., Took place over the common continent Sahul along both the east coast and the west coast of Australia. In doing so, the immigrant human groups formed individual, local and permanent communities . This assumption is supported by the research of some linguists , since many Australian languages developed in isolation .

Genetic studies have shown that the Aborigines came from a wave of emigration from Africa 62,000–75,000 years ago. Further genetic studies set their establishment as an independent cultural group at an age of 50,000 years. They encountered various other hominids on their way to Australia , including a previously unknown group whose genes contributed around 4% to those of the native Australians. The Australian aborigines are the earliest continuous representatives of modern man outside Africa, because today's Europeans and Asians can be traced back to another wave of emigration 24,000 years later.

On the Warratyi rock overhang in the Flinders Ranges in the state of South Australia , traces of human activity were found in 2016, the age of which was dated between 45,000 and 49,000 years. This date is around 10,000 years before the previously accepted date for settling inner Australia. The site also showed that works of art and tools were used by people. These finds are the oldest of their kind in Southeast Asia and Australia and are each also 10,000 years older than the previously known finds.

The Mungo Man , whose remains were found near Lake Mungo in New South Wales in 1974 , is the oldest human to be found in Australia to date. Even if its exact age is controversial among scientists, it is assumed to be around 40,000 years. Nearby was Mungo Lady found from the same period; a complex cremation ritual can be proven with her . Stone tools found at the lake could be determined to be 50,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is located in the southeast of Australia, many archaeologists assume that the first humans must have arrived in northwest Australia a few thousand years earlier.

While Mungo Man was classified as graceful man because of his skull shape and its size, there was in Kow Swamp ( Victoria ) finds of human remains that are classified as robust and estimated to be about 15,000 years ago. At this time the last maximum of the current ice age lasted . The different anatomies were used to support theories about two or three waves of immigration to Australia. However, there are no systematic differences in the mtDNA between these skeletal types, which is why a single early wave of immigration is assumed again. Differences in appearance are now explained as evolutionary adaptations to the colder climatic conditions through selection and gene flow .

After 3000 BC Chr.

About 4230 years ago there was an immigration of people from the Indian subcontinent and mixing with the Aborigines. At that time, the processing of plant parts and the manufacture of stone tools suddenly changed. The dingo , for example, probably came to Australia with seafarers from Timor or New Guinea about 4000 years ago . Today's Aborigines resemble the graceful form of the people again.

Since the 16th century, probably from around 1700, collectors of sea cucumbers came from Makassar every year during the rainy season to the north coast and in particular to Arnhem Land , where this stay influenced the culture of the Yolngu . The first European known to meet Aborigines was Willem Jansz , who set foot on the west coast of Australia in 1606. This was followed by a number of other explorers .

In contrast, the Tasmanians lived in isolation from the Aborigines of the mainland for around 12,000 years after the end of the Ice Age. As the water level rose, the 250 km wide Bass Strait was created , which separated Tasmania from the mainland.

The Aborigines survived all climatic changes and successfully adapted to the changing environment. There is great debate about how much they have changed their environment themselves. One discussion revolves around the role of the Aborigines in eradicating the marsupial megafauna . Some attribute this disappearance to climate change, others believe that the animals were easy prey because of their slowness and innocence. A third possibility would be that the extinction was caused indirectly by human changes in the environment, especially fire .

There is evidence that a substantial change has occurred within indigenous Australian culture over time. Rock paintings in different locations in Northern Australia clearly show different styles that can be linked to different historical periods. Some of these rock art suggest that the last great ice age 20,000 years ago was accompanied by continental drought and the spread of sand dunes with decreased activity and greater specialization in the use of materials and food among the Aborigines.

After 1788

British colonization of Australia began in 1788 with the arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay . The first contacts between the members of the first fleet under Arthur Phillip and the Aborigines are said to have been mostly peaceful at first, as Phillip instructed the Aborigines to be treated well. Food was traded because the colonists could not yet provide for themselves. Bennelong , a member of the Eora , was a mediator between the two cultures who learned English and taught its language and thus contributed to an understanding.

According to estimates by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Aboriginal population decreased from the original 300,000 to 1 million by 1920 to 60,000. Large parts of the Aborigines died of imported diseases such as influenza or the smallpox epidemic of 1789 , in which, among other things, more than 50% of the Darug died. Women's sterility increased because of sexually transmitted diseases, which they contracted mainly through prostitution and sex slavery. Henry Reynolds estimates that 3,000 settlers and 20,000 Aborigines died in violent clashes. In the 19th and early 20th centuries there were many clashes, some of which were fatal, and a wave of massacres of Aborigines , such as the Myall Creek Massacre or the Cape Grim Massacre , in some of which the Native also participated -Police Corps , a police force made up mostly of Aboriginal people. Access to food sources was usually the trigger for conflict. As the settlers 'sheep and cattle destroyed watering holes and grasslands, Aboriginal people lost their livelihood and instead began to hunt the settlers' cattle to feed themselves. In addition, Aborigines did not know anything like land ownership ; Rather, they see themselves as custodians of the land that they care for and guard, but from which they can also take what they need, as long as it is not endangered.

In an attempt to defuse the conflict, Aboriginal peoples were assigned protectorates by a committee of the British government in the mid-19th century. There they were supposed to build settlements and practice agriculture based on the model of the colonialists. In Tasmania, the Tasmanians were rounded up with the Black Line in the Black War in the 1830s and deported to Flinders Island . The term Black Line goes back to the fact that the soldiers were dressed in black and drove the locals in front of them in a line a few meters away from the man next to them. Most recently in the 1950s and 1960s it was enforced in the Western Desert that Aborigines give up their traditional way of life as nomadic hunters and gatherers and that nuclear weapons tests should be carried out in the area of Maralinga Tjarutja . A small group from the Pintupi people , called the Pintupi Nine , lived as fully nomads in the traditional way of life until 1984.

Chief Protectors such as George Augustus Robinson or the Aboriginal Protection Boards were later given extensive rights based on laws such as the Aboriginal Protection Act 1869 in Victoria ; For example, control over the Aborigines with regard to their place of residence, their work, their marriages, their social life and other aspects, as well as the right to decide on the whereabouts of the children.

At the end of the 19th century, Christian churches established missions in the areas of the Aborigines, for example Hermannsburg, and began not only to spread Christian teaching, but also to offer medical help and schools.

From the beginning of the 20th century until the 1970s, Aboriginal children were systematically forcibly removed from their families on the reservations and given up for adoption in white families or in missions. The boys were trained to be farm workers and the girls to be domestic helpers. When the working age was reached, they were forwarded to the surrounding farms. This inhumanity by the notion Stolen Generations (Engl. Stolen generation ) in the Australian and the human history. The main goal was to assimilate especially Aborigines with partly white ancestors and to let them become part of the white society. There was the conviction that after four generations there was no longer any aboriginal part of the gene. Depending on the region and period, about 1/10 to 1/3 of all children were affected. The 1997 Australian Human Rights Commission's Bringing Them Home report addressed the issue of stolen generations and resulted in National Sorry Day being established.

Aboriginal political movements

Human rights

In principle, Aborigines were given the right to vote as British citizens along with the white settlers when the Australian colonies gained self-determination in the 1850s. As a result, Queensland in 1885, Western Australia in 1893 and also the Northern Territory in 1922 introduced laws that explicitly excluded the Aborigines from the right to vote. In South Australia, on the other hand, the right to vote for the British, which had existed since 1856, was expanded to include female Aborigines in 1895 with the introduction of women's suffrage . Queensland was the last state to give Aborigines the right to vote in 1965. The often cited referendum from 1967, however, has nothing to do with the right to vote, but confirmed that the Aborigines in the Australian constitution should be legally equated with other ethnic groups and included in the census .

Although Aborigines received Australian citizenship on Australia Day 1949 like all other British citizens up until then, there were still laws that restricted Aborigines in their civil rights, depending on the state or territory: There were laws that forbade marriages between whites and Aborigines; As a ward of the state, alcohol was forbidden to them; it could still be determined where they or their children lived. Aborigines still received no benefits from the state old-age and disability pension; it was not until 1964 that they received the right to own real estate. There were exceptions for the veterans of the Second World War and, as an exception, Aborigines like the painter Albert Namatjira were granted full civil rights if they could prove that they led a "white" way of life.

In both the First and the Second World War Aborigines had participated as soldiers, which both the setting of the Aborigines to the existing discrimination as well as altered by the whites. Even before the Second World War, the International Labor Organization (ILO) had dealt with conventions against forced labor in 1930 and labor by Aborigines in 1936; Employing families was outlawed. Furthermore, these regulations were extended in 1957 to include the rights of indigenous groups; Minorities were allowed to use traditional law. In the following 1950s, a global political climate developed that sensitized the general public: Australia violated these conventions and Aborigines used this to make their concerns known to the world and to influence politics and change it. The Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 seeks to curb discrimination based on ancestry and repeals any discriminatory laws that still existed in the states or territories.

Politics and Social Rights

After the First World War, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) was founded in 1925 , the first political organization that formulated the social and political interests of the Aborigines, who opposed the kidnapping of Aboriginal children from their families and for free access to schooling and land rights traditional settlement area and against the influence on living conditions by the white administration. The AAPA disbanded in 1927 because of systematic persecution by the police and the Aboriginal Protection Board . In the 1930s, Aboriginal strikes for better food and treatment in Christian missions led by Europeans, such as the 1939 Cummeragunja Walk-off . The first monthly magazine an Aboriginal, Jack Patten , published for Aboriginal people was Abo Call .

The first demands for full civil rights and land rights arose. Two political organizations, the Australian Aboriginal League and the Aboriginal Progressive Association , formed and formulated these demands. This development was successful, because they succeeded in enforcing the Day of Mourning as a day of protest and disbanding a control organization over the life of the Aborigines, the Aboriginal Protection Board, in 1940. The world war ended the developing political opposition.

In 1946, Aborigines began to revolt against their living conditions: The focus was initially on their payment as drovers; With strikes, such as the Aboriginal Stockmen's Strike / Pilbara Strike , which was carried out by 600 cattle drovers until 1949, they tried to ensure that they were not only rewarded with natural produce or very low wages.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, parts of the Aboriginal salary were withheld by the state, which is nowadays discussed as stolen wages and leads to corresponding demands for payment.

The Aborigines were also active internationally in the 1970s against racism . In 1971 there was massive protest against apartheid policies around South Africa's national rugby team, called Springboks , who were on a 6-week tour of Australia. The Australian government was forced to declare a state of emergency in Brisbane as a result of the protests . Were known Gary Foley and another activist, were arrested by the police because of the protest. This dispute had consequences for sport in South Africa, because it denounced the racist politics of South Africa worldwide and racist sports teams were excluded internationally.

In 1972 the so-called tent embassy was erected in Canberra , the capital of Australia, in which the demand for the sovereignty of the Aborigines as an independent nation was expressed. The last living founder of the tent embassy, Miachel Ghillar Anderson , is currently the most important advocate of this political demand.

In the 1970s, a political movement of the Aborigines, the Outstation Movement , developed, which pursued the resettlement in their ancestral areas taking into account their cultural and social interests. Settlements were mainly established in remote areas in the Northern Territory , Western Australia and Australia . In the Northern Territory, about 30 percent of the local Aborigines live in about 500 homelands scattered across the country. The current (2015) ruling Prime Minister of Western Australia Colin Barnett plans to close around half of the 241 Out-Station settlements. He is supported by the Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott , both of whom are members of the Liberal Party of Australia .

On February 13, 2013, the House of Commons passed The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Bill , a law that recognizes the Aboriginal people as the first residents of Australia. This law - the passage in the upper house is considered certain - must, however, be confirmed by a referendum in order to obtain constitutional status. A referendum on this matter has been announced by the Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard .

Land rights

From the 1960s onwards, the question of land rights increasingly became the focus of political interest. Australia was described by Captain James Cook in 1770 as almost uninhabited and later - despite the presence of the Aborigines - declared Terra Nullius .

One action that also attracted international attention was the Yolngu Bark Petition , in which in 1963 Yolngu filed a petition written on tree bark against the construction of a bauxite mine on their traditional land. The tent embassy set up on the lawn in front of the Old Parliament House in Canberra in 1972 was intended to underline not only the demand for recognition of an independent Aboriginal nation but also its claim to land. In 1971, Neville Bonner became the first Aborigine to enter the Australian parliament.

In 1966, 200 Gurindji cattle drovers struck the Wave Hill Cattle Station for equal wages with the white workers, since they had only received a low wage or in kind until then. The nine-year strike over labor rights soon became a federal matter when the Gurindji demanded the return of their land, and in 1975 Prime Minister Gough Whitlam returned much of it to Vincent Lingiari on his behalf .

With the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 the possibility of claiming land rights was granted for the first time and large areas became the property of Aborigines again. In 1993, organizations like Native People of Australia, led by Eddie Mabo, won the Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) the so-called Native Title , which grants property rights to crown land (state-owned land) that is historically assigned to a certain tribe. In some cases, however, mining and water rights are excluded, except for personal use.

Land rights movements are also combined with ecological demands. One of the first Aboriginal peoples to get their land back under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 , but not the mining rights, were the Mirarr . When uranium was discovered in 1960, the Mirarr successfully resisted mining in the Jabiluka mine in Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory , Australia . The Mirarr have been resisting since 1971 and in 1998 some 5,000 Aboriginal and environmental activists from around the world occupied the area for eight months, 550 of whom were arrested. In 2002 the mining was stopped because of the falling uranium price.

The Aborigines do not understand the right to land as property in the sense of German (or Roman) property law. Australian law now recognizes the legal relationship to land ownership by the Aborigines. There are different entitlement regulations, especially depending on the federal state. It can be seen that in the north the native title and land use rights in the south-east play a role. 1.1 million square kilometers of land were given to the Aborigines from 1966 to 1991, which is about 15% of the land area of the Australian continent.

Living situation today

| area | Aboriginal | Population share |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 140,000 | 2.1% |

| Queensland | 113,000 | 2.7% |

| Western Australia | 75,000 | 3.8% |

| Northern Territory | 64,000 | 31.5% |

| South Australia | 24,000 | 2.4% |

| Victoria | 28,000 | 0.6% |

| Tasmania | 15,000 | 3.1% |

| ACT | 4,000 | 1.2% |

While the number of Aborigines was estimated at only 60,000 in 1920, it rose to 265,000 in the 1991 census and to 464,000 by 2006. In addition to an expanded definition of who is Aborigine, it is also attributed to the increased self-confidence to call oneself an Aboriginal. The increased recognition of the Aborigines is also reflected in symbolic gestures, such as the depiction of David Unaipon on the Australian 50 dollar note since 1995, Gwoya Jungarai on the 2 dollar coin since 1987, Len Waters , an Aboriginal pilot in the Second World War , since 1995 and Cathy Freeman , the first Aboriginal figure depicted on a postage during her lifetime, since 2000. The latter is noteworthy because until 1997 it was not allowed to depict living persons on postage stamps in Australia, except personalities of the Monarchy.

However, many problems are still unsolved: Compared to the total population of Australia, the indigenous people - and especially those who live in rural areas - belong to the poorest part of Australian society; At 20%, their unemployment rate is almost three times as high as that of the average population, they have less education, their life expectancy is on average ten years below that of the white population, child mortality is twice as high and their share is less than four Percent of the population made up 20% of all prison inmates. These differences are explained by the loss of functioning social structures due to the policy of assimilation and the general lack of work and health care in rural areas.

In June 2007 the Australian government announced the Northern Territory National Emergency Response , discussed in the media under the term "Intervention": The occasion was the Little Children are Sacred report of the Northern Territory, which documented the spread of child sexual abuse . Various measures have been taken with the aim of creating a safe environment for children. These include the prohibition of alcohol and pornography in Aboriginal communities, but above all extensive medical screening of children, more police and more teachers. The intervention is logistically supported by the military. The communities have lost their self-administration. Supporters of the intervention welcome the government's action against the situation in Aboriginal communities. Critical voices complain above all that the intervention is racist, since part of the social welfare for all Aborigines in this area is controlled by the state, including those who have not become socially conspicuous. It is also criticized that the intervention took place without consulting those affected or that it was paternalistic and completely destroyed the existing Aboriginal culture. With regard to alcohol, it should be noted that the proportion of Aborigines with risky alcohol consumption of 11 percent does not differ statistically significantly from that of the non-indigenous population. Instead, alcohol degradation is slowed down in a particularly large number of Aborigines due to a lack of enzyme, and even small amounts of alcohol lead to abnormal behavior in Aborigines.

Theoretical equality of the Aborigines and a latent racist practice still diverge widely, as shown in a report published in May 2018 by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. According to this report, the total number of minors criminally indicted is decreasing significantly while the number of indicted, detained and supervised Aboriginal youth is increasing. In 2012/2013, indigenous youths were fifteen times more likely to be under judicial supervision than their white peers; this parameter has risen to 18 in the last five years. In 2017, an average of 5,359 adolescents between the ages of 10 and 17 were supervised every day, half of them from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, although their children only make up 5 percent of the total Australian age group. The report does not analyze the multiple reasons (for example the frequent sexual abuse of minors in Aboriginal communities) for the comparatively high crime rate.

society

Traditional lifestyle

The population was very likely constant for thousands of years. Even before the arrival of the Europeans, the most densely populated regions of Australia, still today, on the coasts in the southeast and in the valley of the Murray River . However, there were tribes all over the continent who had adapted their living and eating habits, technologies and hunting methods to the respective environment in all cases, regardless of whether it was the cold and humid highlands of Tasmania or the dry and hot interior of the continent.

There were differences in the wild-hunting way of life in individual cases, for example the Gunditjmara had a sophisticated system of aquaculture and eel breeding, they also built stone dwellings and had a permanent place of residence. There was also a seafaring tribe, the Ngaro , who remained largely unknown. This tribe lived in the sea area of the Whitsunday Islands and safely navigated and hunted in outrigger canoes in the sea.

In the course of the European expansion, the indigenous people were increasingly displaced into the previously almost uninhabited, drier parts of the country, where there was significantly less game. Massive deforestation and the conversion of large areas into agricultural and livestock areas changed the appearance of the landscape. In particular, the associated introduction of neozoa such as rabbits, cats, dogs, foxes, horses, buffalo and sheep damaged the local fauna and flora considerably and made it increasingly difficult to continue the traditional way of life. Since the Europeans settled in the arid regions over time all areas that had access to water, the Aborigines had little choice but to also settle near where there was water and access to (modern) food. This development permanently destroyed people's independence and led to the decline of traditional knowledge .

Most of the indigenous people in the outback earn their livelihood today by working on farms and ranches, as tour guides or by selling handicrafts. Since the 1970s, the traditional hunting and collecting techniques have again played a more or less important role in many local communities . In largely assimilated groups, the men's hunt (with cars and rifles) is practiced as a socially highly valued weekend sport, but in the more traditional groups in the “outstations”, hunting and gathering serve to supplement subsistence . In some regions, after the land rights have been clarified, there is an increasing return ( retraditionalization ) to the original procurement of food (in some cases initiated by tourism). In this way, smaller groups try to reduce their dependence on the settlements and to revive the social practices of the elderly. The implementation is difficult depending on the region. On the one hand, the long interruption of the hunt saved the game population, on the other hand, the influences of the white settlers have damaged the ecosystems in some cases permanently. In addition, it is not foreseeable what consequences modern hunting methods will have.

nutrition

All of Australia's indigenous people were hunter-gatherers , with the people who lived on the coast or on rivers also being fishermen who also caught turtles and dugongs in the tropical north . All Aboriginal tribes and communities used and managed their food sources and supplies using different, sophisticated methods; However , they did not farm . There were two different tribes operating economic eel farms in what is now Victoria . They used complex and extensive systems with irrigated ponds; one on the Murray River in the north of the state and one in the southwest near Hamilton , from where they traded as far as the Melbourne region . But also in the area of today's Sydney a large cultivation and trading center developed. The typical food, the bush food , consisted of a variety of foods , for example kangaroo , emu and its eggs, wombat , goanna , snakes , birds, especially in the deserts also many insects such as honey ants or witchetty maggots and on the coasts Mussels and crustaceans . In addition, many varieties of plant food such as nuts , fruit and berries were also used. In the desert areas, for example, the bush banana (Marsdenia australis) and the bush tomato (Solanum centrale), in the tropical north the bush plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana). Some groups, such as B. the Martu today also have domestic cats on their menu. This has created a “quasi-natural” corrective in the ecosystem that somewhat reduces the harmful effects of cats on biodiversity .

The primary tool used in hunting was the spear , which was thrown by means of a woomera or by hand. Boomerangs were used in both the northern and southern deserts, with the non-returning variant (better known as the throwing stick ) being more effective and more common than the returning variant . It could be used to kill kangaroos, for example.

Reports on institutionalized cannibalism are scientifically referred to as “hearings, second and third hand reports, exaggerations, false citations and deliberate lies”. Burial rituals were misinterpreted, but reports of cannibalism were also deliberately circulated in order to discredit Aborigines as savages who could be denied human rights and had their land taken away.

Nomadic life

In some areas, the Aborigines were semi-sedentary, especially in less arid areas where fishing allowed them to become more sedentary. Furthermore, most of the indigenous tribes were seminomadic and moved in a regular rhythm through a certain area, in which they followed their food sources and settled in the same place again and again at the same time. By examining the accumulation of waste, archaeologists have shown that some of these places have been visited annually for thousands of years. In the dry areas, the Aborigines were exclusively nomads who moved over large areas in search of food.

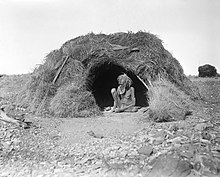

They lived in simple huts or under windscreens made of twigs or bark. Fixed huts made of branches, tree bark, grass and reeds were only built for longer stays. Members of other tribes were not allowed to enter the camps unless they were invited. If a messenger was sent to a different tribe, it would have to wait some distance away before being given permission to come closer. Some Aborigines kept dingoes as companion animals in order to use them when hunting or to warm themselves on them during cold nights.

Ecology and fire

The indigenous peoples of Australia used fire for a variety of purposes. It is believed that this first happened around 7000 years ago.

The controlled firing of dry grasslands, bushes and forests served the Aborigines to create paths through thickets and prickly wood, to promote existing crops and to initiate new growth, to create hunting opportunities and useful plants for immediate consumption or cooking, for heat generation or also for the transmission of messages, as well as for spiritual purposes. The use of the purpose-oriented fire followed certain rules, which were based on the course of the vegetation and the needs of the Aborigines. It was used for the growth of edible plants or to promote the ingestion of hunted animals, but also to reduce the risk of uncontrolled bushfires .

Early European explorers and settlers captured Aboriginal customs with fire. The fires spread across the landscape throughout the year. Most of the fires were of relatively low intensity and in most cases only burned small areas, which rarely resulted in large-scale uncontrollable bushfires.

Fire is also an important part of Aboriginal culture, and knowledge of its use has been passed down from generation to generation.

It is also believed that with the burning of plants, the Aboriginal people also influenced the early monsoon rains and, with it, the climate of Australia. There is, however, great disagreement about the extent to which firing has contributed to changing the environment.

initiation

The initiation was carried out in several stages over several years: For example, the young people got to know their totem , supported by age-appropriate stories of the dream time and new chants. But they also learned strategies for dealing with conflicts.

Usually between the ages of 10 and 12, adolescent boys underwent an initial rite of initiation, which could last for weeks. They were separated from their mothers and were not allowed to speak or be spoken to. Part of the initiation rites is the walkabout , an introductory ritual for thirteen-year-old Aborigines who are going their own dream path for the first time.

Especially in Central Australia, for example at Arrernte, Pitjantjatjara and Luritja, circumcision is common at this age . In these peoples, subincision is also practiced in later adolescence .

In a final initiation stage at the age of 16 or 17, the skin of young men and women was scarified in almost all peoples , making them marriageable. The scars were two to four simple juxtaposed lines on the shoulder, chest or stomach, which were created with a sharp stone knife, depending on the people. As a sign of initiation, it was common among peoples of the coast to remove or change a tooth, or to add a piercing.

Kinship system

The key to understanding their social structure lies in their complex web of kinship relationships and their implications, which existed in various forms in all parts of Australia and which still exist today, particularly in Central Australia.

The basis of kinship relationships is not the Eskimo system , which is widespread in Western cultures , but the Iroquois system . The Eskimo system consists of a nuclear family: father, mother, brother and sister. The Iroquois system expands the concept; so all sisters of the mother are also called mother. Analogously, all brothers of the father are called fathers. Only if the gender changes in the parent generation (on the maternal or paternal side), other terms are used. So you only have uncles on the maternal side and aunts only on the paternal side. The aunt on the maternal side is called the mother and the uncle on the father's side is called the father. The system also extends to cousins. The children of the mother's sister (who is also referred to as mother) are not cousins, but brothers and sisters. This also applies to the children of the father's brother (who is referred to as the father). According to this, one can only have cousins if they are the children of the parents' siblings and change gender (brother of mother / sister of father). This distinction is important because only those identified as cousins can be considered as marriage partners. This is a so-called cross - cousin marriage , which is also known from other cultures.

The system just explained is egocentric, because it starts from a person (ego) and develops relationships with other group members. This egocentric picture, however, only emerges from an analysis of the actual kinship system. This is explained below:

In contrast to the Western consanguinity system , Aboriginal people do not distinguish between related and unrelated. In their sense, each group member is related to all others. The system described here is used in different variations by almost all Australian Aborigines. In this way, even newcomers from other groups or people from outside (e.g. anthropologists or linguists who have lived with a clan for a long time) can be easily integrated. Once you have a position in this system, you can find out your relationship (and the corresponding name) to every other member of the group: The entire clan is divided into two moieties (from French: French moitié : half; English: moiety ), which are represented by certain associated group totems (animals, plants, places). This classification is important for marriage rules and rituals. It is forbidden to marry a person with the same moiety or the same totem. You always marry exogamously, i.e. in the other moiety. In religious rituals, the members of the two moieties have different roles. There is also a further subdivision into so-called skin groups (literally in English: skin group). Skin group is an anthropological term and does not designate a real skin group or color. Most clans have four skin groups (two per moiety), but there are also many examples with six or eight skin groups .

A concrete example to illustrate this: The tribe of the eastern Arrernte, who live in central Australia, has a system with four skin groups . (The north-eastern arrente have eight skin groups , the central arrente have six). A person belongs to one of the following skin groups : Either the Kemarre , Perrurle , Penangke or Peltharre . The first two groups belong to a moiety; the latter to the second moiety.

This results in the following marriage rules.

- A Kemarre man marries a Peltharre woman . The children belong to the Perrurle group .

- A Perrurle man marries a Penangke woman . The children belong to the Kemarre group .

- A Penangke man marries a Perrurle woman . The children belong to the Peltharre group .

- A Peltharre man marries a Kemarre woman . The children belong to the Penangke group .

The system is cyclical and repeats itself after two generations. Even in the more complex systems with six or eight skin groups , a cycle is repeated after every second generation.

The real importance of this system lies in the fact that the various skin groups have tasks in the trunk. For example, the system determines: who is hunting for whom? Who is raising which children? Who is the guardian of the language? Who is allowed to perform certain rituals and who is not? Who is holding the death ceremony? Furthermore, certain rules apply, according to which the members must behave. The rules include manners such as distance, politeness or jokes. The system of skin groups thus takes on many functions that are determined by the political or economic system in Western societies.

Traditional social structure

On the basis of this group totemistic kinship system, the local Aboriginal groups were divided into clans ; if specific hunting groups are considered, one speaks of hordes as the smallest economic association. Originally, these groups were organized throughout Australia without a political rulers (→ acephaly ) and socially without a clear hierarchy (→ egalitarian society ). That means, in principle, all group members were equal to each other and there was neither rich nor poor, neither common nor nobles nor chiefs . Only older people enjoyed special recognition for their wisdom and the so-called Clever Men / Women for their magical powers. Due to this social structure, strictly speaking, it is not correct to designate the largest linguistic and cultural units of related clans as tribal societies , because apart from the “ we-feeling ” there was no higher-level unit.

Religions

In the ethnic religions of all Aboriginal peoples, the misleading expression "dream time" (English: dreaming or dreamtime ) is at the center of spiritual thought. The stories of the dreamtime describe the time of creation, the ancestral spirits such as the Byamee , the rainbow snake or the great kangaroo , which formed the land, the plants and living beings. A well-known example is the Uluru myth , which is part of Tjukurpa , the term for dream time in the Pitjantjatjara language. Numerous rock paintings , carvings and dances show the beings of the dreamtime and, in the imagination of most of the tribes, originally come from this. Earlier ethnology believed to be seen in the dreamtime and ancestral beings or the cultural heroes high god conceptions. Today, however, it is believed that the Aborigines have no actual gods .

In addition, traditional knowledge about the country is passed on through dream time stories. For example, the songlines are descriptions of the country and are a guide to walkabout . Furthermore, the laws, the moral system and the kinship system are part of the dream time.

Everyone is connected to the "spirits and the law of dreamtime". This law also included the initiations of the youth, which were specific to each area. They were staged in ceremonies such as the corroboree , which were not of a sacred nature, for example with tribal dances, which in European interpretation only have entertainment value (everything has metaphysical references with the Aborigines). Other ceremonies were secret.

Not all Dreamtime stories are available to everyone: children hear simple versions; these have also been passed on to outsiders. Other stories are just for women or just for men, most of initiated (English: and some exclusively for the elderly elder ) who respected authorities.

Primary importance for the religious life of the Australians were the totem ancestors , which are connected to earthly life. The totem connects the group with their ancestors, it determines their present cohesion, and it is the basis of the extremely complicated exogamic marriage regulations. While there is a strict ban on eating the totem in general, eating the totem plant or animal can be ritually permitted or even required. The presence of the totem reminders is experienced in the hum of the buzzing wood . The cult is also closely connected with totemic views . The rites are founded by the totem ancestors, and the practitioners consider themselves to be of the same nature as these ancestors because of their totemic ties. Songs and dances that accompany their rituals are considered the creations of the totem ancestors.

Even if the content of songlines and the meaning of certain places and totems is not always known, the criteria according to which responsibility and “property” are assigned are described in detail. In most tribes, the location of the first perceived child movement in the womb (less often the birth itself) determines which totem associated with the location is given.

Today 73% of the Aborigines profess a Christian denomination, as missions in the protectorates of the Aborigines not only built schools and health care, but also spread their teaching. 1.3% profess traditional religions and the rest no religion. According to the ongoing surveys of the evangelical-fundamentalist conversion network Joshua Project , however, between 30 and 70% of many tribes still profess an ethnic religion . Syncretistic hybrid forms have hardly developed in Australia, the Aborigines saw Christianity more as an additional "religious path" (this may be the reason for the different numbers). The practice of traditional religions is mainly found in remote settlements in central and northern Australia. A revitalization movement that began in the 1960s and 70s led to a general revival. However, a lot of old knowledge has been destroyed by the rigid mission policy.

languages

It is debatable how many Australian languages existed before the arrival of the Europeans. The numbers vary between 200 and 300; one usually agrees on about 250, of which about half of these languages have since become extinct. Only 20 languages are actively passed on to children today; the remaining 100 or so languages are only used by middle-aged and elderly people, which means that with every further decade some of these languages will disappear. Arrernte (2800 speakers), Djambarrpuyngu, a Yolngu language (2700), and Pitjantjatjara (2600) are still most widespread today . They are all spoken in the Northern Territory, where 59% of the Aborigines still speak an indigenous language at home. In cities like Sydney and Melbourne, where most of the Aboriginal people live, the rate is only 1%. In total, there are still around 50,000 people in Australia who mainly speak an indigenous language. Bilingual programs have been offered in schools since 1973 in parts of Australia with high Aboriginal populations.

Linguistically, the Australian languages are divided into two groups: Arthur Capell differentiated between languages with only suffixes and languages with suffixes and prefixes . The latter are spoken in northern Australia - between the Kimberleys in the west and the Gulf of Carpentaria in the east. The first group covers the entire rest of the continent. In a 1966 paper, Geoffrey O'Grady, Stephen A. Wurm, and Kenneth Hale theorized that the suffix group was a closely related family of languages that spanned 7/8 of the continent. This family was named Pama-Nyunga by O'Grady, Wurm and Hale , after the words for "human" in the two most remote areas of this language family (northeast Queensland and southwest Western Australia). The second group (with prefixes and suffixes) is defined by exclusion, i.e. as Non-Pama-Nyunga . It does not form a single language family, but was initially divided into 28 (later into 26) language families. This group represents 90% of the linguistic diversity on 1/8 of the continent.

In northern Australia, the contact between white settlers and the Aborigines developed into a Creole language based on the English language , the Kriol , which is still spoken by around 4,000 people today. The vast majority (86%) only speak Australian English , although there is also a variant of Aboriginal English .

Arts and Culture

Visual arts

When Aboriginal art there is, whether it is traditional or modern works, two levels of interpretation: "[The] 'internal' stories, which are intended only for those who have the appropriate ritual knowledge, and [the ] »External« stories that are accessible to everyone. ”The artist is the owner and shareholder of the displayed content, which is only assigned to him for specific purposes. Only he has the right to use sacred patterns and depict religious content. The use of designs that belong to others, and if they are used without their permission, is a serious violation of this ancestral unwritten law.

Traditional art

Aboriginal art is one of "the oldest continuous art traditions in the world". Aboriginal art encompasses a wide range of mediums, including painting bark panels, wood and stone engravings, sculpture, sand painting, creating ceremonial clothing, and artistically decorating weapons and tools. The materials used were colors made of ocher, ashes and blood, fabric, feathers, wood, stone and shells.

The Arnhem Land and the adjacent areas have the largest number of Aboriginal artworks such rock carvings and rock paintings. The drawings and ornaments found there have been dated to an age of up to 50,000 years. Arnhem Land is also known for bark painting, sculpture and weaving. In the desert areas, in addition to rock paintings, floor drawings were also made in the sand. In the north of Queensland and on the Tiwi Islands , sculptures are particularly important as works of art.

Art is part of the main rituals in Aboriginal culture; it was and is used to mark territories, record history and support and convey narratives about the dreamtime. When the sea level rose about 10,000 years ago, sea creatures like the rainbow snake became the subject of rock painting. Rock painting was practiced until the 20th century and served, among other things, to teach anatomy , such as the so-called X - ray representation of the Barramundis.

Modern art

With new techniques and materials such as synthetic paints and canvas, further developments of these forms of expression took place: In Australia, the first major Aboriginal art exhibition took place in Victoria in 1929 under the title "Primitive Art". Albert Namatjira was instrumental in ensuring that Aboriginal art was accepted; he exhibited his watercolor landscapes for the first time in Melbourne in 1938. Queen Elizabeth II awarded him a medal in 1953 and met him personally a year later in Canberra.

The growing recognition that Aboriginal art enjoyed is reflected in the art's spread: in 1941 and 1942, in North America and Canada, Aboriginal art was first exhibited outside of Australia. In 1957/58 the art collection "The Art of Arnhem Land" was shown in Australia as a traveling exhibition, in which the artists were classified according to their styles. In 1959 the Art Gallery of New South Wales bought works by contemporary Aboriginal artists. Finally, in 1966, a painting pattern by David Malangi was shown on the Australian 1 dollar bill.

The development of the most commercially successful art movement began in 1971 and 1972, when the art teacher Geoffrey Bardon encouraged Aborigines in Papunya , northwest of Alice Springs, to paint their stories of the dream time as honey pot ant murals on the school walls there. He also instructed her in the use of modern painting materials and techniques, and encouraged her to capture her dream time on wooden boards and canvas. This mural formed the starting point for modern Aboriginal painting today. The most famous and successful artist of this movement, which came to be known as dot painting, was Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri , who bought a painting for a record price of 2.5 million Australian dollars (AUD) from the Australian state that prevent wanted this cultural asset to be sold abroad. Another successful artist of this style was Johnny Warangkula Jupurrula . He was one of the first to perfect the form of dot painting and create iconographic elements that dissolve in the picture.

Aside from painting, there were also significant milestones in other art forms: In 1988 a memorial to Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders was unveiled at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra . It consisted of 200 hollow log tombs erected as part of the 200th anniversary of the British colonization of Australia and in memory of those Aborigines who died in violent conflicts with settlers. In the same year, the new Parliament House opened in Canberra with a 196 square meter granite mosaic made of paving stones by Michael Nelson Jakamarra .

In the last few decades, numerous art centers and artist cooperatives have sprung up in Aboriginal settlements promoting the production and trade of works of art, such as the Warburton Art Project , the cooperatives in Papunya , Kintore and many others. This form of production of works of art enables the Aborigines to live on their own and without government support. Despite the distance of many artists from urban settlements, and the poverty and health problems of many artists, this rapidly growing craft is valued at half a billion Australian dollars.

Another way of younger Aboriginal art, which has developed in the cities, is Richard Bell , who as a painter also designs performances or makes videos, in which he deals politically with the relationship between whites and blacks. Although he combines traditional and modern Aboriginal art, he sharpens social contradictions both with his work and with his statements: "Aboriginal Art - that's a matter for whites!" [...] "I want my whole country back ..."

music

Traditional music is part of the traditional arts of Australia, so the same concepts and laws apply to it as to the visual arts. Here, too, there is an "inner" and an "outer" level (see above). The music is owned by a specific person or group and, among other things, transports. Obligations and contents of the tribal laws and serves to communicate historical or mythological stories or experiences that are related to it. The music is also tied to geographical conditions that are linked to one another through mythological events (“songline”).

The most important musical element of traditional Australian music are the chants, which are performed individually or with several participants. They are guided by one or more “songmen” or “women” who are responsible for the correct implementation of the ritual and who are the owners or guardians of the respective form or content. Individual songs are rarely longer than three minutes, but are often integrated into longer singing cycles (ceremonies). Chants cover the entire spectrum of meanings from personal narratives and amusement songs to highly spiritual rituals that serve to maintain the totem identity .

The rhythm is occasionally applauded to the songs, also with the cupped hands on a piece of fur (earlier) or a piece of clothing (today) in the lap, or on the buttocks.

Percussion instruments can be found in the form of clap sticks (short hardwood sticks ), which indicate the basic rhythm, but boomerangs are also used, which are hit against each other in pairs.

The northern Australian Aborigines, especially in Arnhem Land and the Kimberleys, play the yidaki ( didgeridoo ), a wind instrument from the aerophone family with a sound rich in overtones and pitches between tenor and bass. It is mostly made from the wood of the black or yellow "woolybutt" ( Eucalyptus miniata ) or the "stringybark" ( Eucalyptus tetrodonta ) hollowed out by termites , which occurs in tropical regions. Usually the yidaki is used as a rhythm instrument for the chants in ceremonies. It is traditionally rarely used as a solo instrument, even if tourists are often given the impression that the yidaki is mainly used to tell stories. The use of this instrument has spread across Australia since the 1960s and is seen by many Aborigines as a symbol of their traditional identity, even outside the area of origin.

In northern Queensland, for certain ritual purposes, a drum made from a hollow piece of eucalyptus covered with animal skin (Ubar) is played, which, like the batons, only accompanies the measure of time. Their use has fallen sharply.

The music Gumleaf (rubber sheet) is created with a simple musical instrument. Special tones are created, as well as bird calls. The musicians bring a eucalyptus leaf to their mouth and puffs of air generate sounds. Gumleaf is traditionally a music of the Aborigines, but since the British colonization there have also been whites who have mastered this music and who have been competing in an Australian championship every year since 1977. Well-known interpreters of this style of music are Herb Patten and Roseina Boston .

Occasionally the use of flutes or pipes made of hollow stalks has been documented, but they have no musical function and are more of a signal character.

The bora-bora ( buzzing wood or bull-roarer) is to be classified as a tool of spiritual perception techniques for initiations.

Another integral part of traditional music is dance. Individual dancers or groups symbolize the content conveyed by the chants with their movement patterns. The dancers and musicians are in constant contact, the music provides very specific key signals for certain dance steps and dynamic developments.

Aboriginal music is not just limited to traditional music and the use of traditional musical instruments: Aboriginal rock in Australia began with the band Yothu Yindi , which formed in 1986 and became known with the political song Homeland Movement . This band had success beyond Australia with Treaty in 1992 and successfully combined the didgeridoo with modern instruments. This band is played by Aborigines and Australians of European descent. They play old and modern music, but also pop and rock. In Germany they are known, among other things, for their collaboration with Peter Maffay on his album. This song is dedicated to the forcible removal of thousands of children from their Aboriginal parents. The song was not only popular with the Aborigines. Roach won several prizes for it and received a gold record as an award for the sales success .

The Warumpi Band, which combines hip-hop and rap, is also known.

literature

David Unaipon was the first Aboriginal to write a book called Aboriginal Legends and published it in 1927. The author Colin Johnson, who took the Aboriginal name Mudrooroo , is considered to be the founder of politically active Aboriginal literature. In 1965 he published the novel Wild Cat Falling , which went down in world literature. In this he dealt with the fate of a young Aborigine who wants to change, which he only succeeds in before a (renewed) conviction. Mudrooroo continued this theme in 1988 with Doin Wild Cats and with Wildcat Screaming in 1992. In the other short stories on the subject of "Wild Cat" he dealt with the boy's traditional and modern life experiences. Mudrooroo's father, who was African, had pretended to be an Aboriginal and therefore Mudrooroo was heavily criticized in the 1990s. Because of this unknown fact, which he was accused of concealing, he lost political importance. He published numerous other literary works and gave lectures abroad on the life of the Aborigines and above all described the difficulty that the English language creates in order to clarify the indigenous point of view.

With Sally Morgan it was the other way around. She assumed she was a child of an Indian family for years until she found out as a young girl that she was of Aboriginal origin. She processed these experiences in the novel My Place , which appeared in 1987 and attracted worldwide attention. In the work she wrote Wanamurraganya , she describes the story of her grandfather. She is also successful as a creative artist, in 1993 she won an award for her print Qutback . Today she is the director of the Center for Indigenous History and Arts at the University of Western Australia .

Another successful Aboriginal writer is Doris Pilkington , who received a literary award in 1996 for her novel Caprice - A Stockman's Daughter . In the same year she published the novel Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence , which was filmed in 2002 by Phillip Noyce under the title Rabbit-Proof Fence (Eng .: Long Walk Home ), and which is about the childhood experiences of her mother and the Stolen generation . The novel describes the escape of three Aboriginal girls from a camp set up to re-educate children from mixed marriages between native and immigrant Australians along the 3,256-kilometer-long protective fence against the rabbit plague . The fathers of these children were mostly white migrant workers and the mothers Aboriginal people.

Movie

The film industry turns to the topic of Aboriginal people in the form of documentaries and feature films.

The film Australian Rules of Paul Goldman from 2002, which on the autobiography similar amendment Deadly Unna based Phillip Gwynne, processes the subject of racism and sport. It shows the experience of two befriended 16-year-old Australian boys playing football. Gary Black (Nathan Phillips), a white man, and Dumby Red (Luke Carroll), an Aboriginal and successful football player from a fishing village, experience the latent racism of the villagers. This erupts when more than half of the village's soccer team are Aboriginal and that team wins a prize. In the ensuing violent confrontation, the young Aborigine is murdered.

Richard J. Frankland , an Aboriginal of the Gunditjmara tribe, was a singer and songwriter, writer and director. After his experiences as a member of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in 1966 he made the award-winning documentary Who Killed Malcolm Smith , a film about the high suicide rate of the Aborigines. Other films by him that deal with Aboriginal life include: Clanging Doors (1991), Songlines (1993), No Way To Forget (1996) and Harry's War (1999).

The director Wayne Blair made the film The Djarn Djarns , which received the Children's Short Film Award at the 2005 Berlinale. The film tells the story of an eleven-year-old boy, a dancer who, in his Aboriginal dance group, comes to terms with the anniversary of his father's death.

In 2006 the film 10 Canoes, 150 Spears and 3 Women was made , which was shot in the area and in the community of Ramingining with the participation of some artists from Ramingining. The significance of this film lies in the fact that it brought the cultural region and the local Aboriginal life on the edge of the Arnhem Land into the light of the international public. He received a critics award at the Cannes Film Festival . The director was the Australian documentary filmmaker Rolf de Heer . The film was shot primarily in the Australian language Ganalbingu.

The film Long Walk Home (Rabbit-Proof Fence) , which was released in 2002, deals with the fate of three children from mixed marriages who, due to legal requirements, were taken away from their mother and taken to a reformatory. They run away from there and experience racism on their return journey.

The 1971 movie Walkabout was directed by Nicolas Roeg . It is based on the 1959 novel Die Kinder (orig. The Children , later under the title Walkabout ) by James Vance Marshall . In it, two children meet a young Aboriginal who is on the walkabout, an initiation ritual in which the thirteen-year-old embarks on his dream path and has to remain alone for a long time and take care of himself. The encounter with the people of the foreign culture has a fatal effect on the Aborigine, he commits suicide.

Dance, theater and musical

Dance, singing, ceremonies and initiations have always been part of their traditional and cultural life for many Aboriginal peoples. For example, the Tiwis who live on the Tiwi Islands off Darwin learn to dance with their totems from their mother, and the dance themes change according to the occasion. However, some dances also arise spontaneously and express the emotions of the dancers, or they correspond to their ceremonies. The experiences of World War II, such as the bombing raids on Darwin, can also be found in the dances and songs of the Tiwi. Singing is always connected to their dance and new songs are constantly being created while dancing, whereby they paint their bodies with ocher. The body paintings of the Tiwis can be found as patterns on their works of art.

A Bran Nue Dae (1991) was the first musical composed by an Aborigine. In the form of a rock opera, it shows the Aboriginal boy Willy on a journey from Perth to his homeland in his search for himself, for affection and security. It is the autobiographical story of Jimmy Chi , who grew up in Broome and whom his mother sent to a Catholic mission station in Perth. After a car accident, he was first referred to a psychiatric ward; when he left this he went back to Broome and taught himself to make music and to write songs. The musical has won several awards, such as the Sidney Myer Performing Arts Awards and the Western Australian Premier's Book Awards . The musical was later made into a film.

Since the early 1990s, Aboriginal people founded successful dance theaters that formed a cultural link between the Aborigines and the white population of Australia. The Bangarra Dance Theater (Bangarra means making fire in the Wiradjuri language ) is a dance theater that was founded in 1989 by Carole Johnson and is known for its Aboriginal dance performances abroad, especially in the USA and Great Britain. It performed at the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. The Chunky Move is an Aboriginal dance theater from Southbank , Victoria that was founded in 1995 and has performed not only in Australia but also in Asia, Europe, the USA and Canada.

The play Stolen Generations , written by Jane Harrison and premiered in Australia in 1998, is about the fate of five Aboriginal children who were taken from their mothers. It was performed in Asia and the USA and allows the experience of the forced removal of the mostly "half-blooded" Aboriginal children to be understood. Another play by Jane Harrison, Rainbow's End , staged in Melbourne in 2005 , deals with the lives of three Aboriginal women fighting against and for livelihoods in a small town in the 1950s.

Sports

Aboriginal participation in sport dates back to the 19th century. The sporting activities began in English cricket and continued in athletics and Australian football . Individual athletes achieved national popularity and were able to convey emancipatory content.

Cathy Freeman achieved worldwide attention for the problems of the Aborigines in 2000 by winning the gold medal in the women's 400-meter run at the Olympic Games in Sydney, especially as she not only carried the Australian flag, but also the Aboriginal flag in the stadium showed, although actually only showing national flags is allowed.

Nova Peris , who was the first Aboriginal to win Olympic gold in hockey in 1996 and won two athletics disciplines at the 1998 Commonwealth Games, was elected to the Australian Senate in 2013 for the Northern Territory .

Another publicly successful activity was carried out by Australian rules football player Michael Long in 2004 when he began a march from Melbourne to Canberra to confront Prime Minister Howard . He had denied the suffering of the Stolen generation several times. Long achieved, among other things, because of the great publicity that the Prime Minister presented himself to a debate.

David Kantilla , also called Amparralamtua in his language , was the first "thoroughbred Aborigine" in 1961 to play in one of the highest football leagues (SANFL) in South Australia. He was descended from the Tiwi people.

Lionel Rose became the first Aboriginal to win a world boxing title in 1968; in the same year he received the award Australian of the Year , which helped him to further popularity.

It was not until the spring of 2008 that Jade North became the first Aboriginal to wear the captain's armband in a friendly between the Australian national soccer team and Singapore.

Evonne Goolagong , an Aboriginal woman, was one of the most successful Australian tennis players ever. She won the Australian Open four times , the Wimbledon Championships twice and the French Open once .

Adam Goodes, a nationally known football player who publicly discussed social discrimination, has been regularly insulted with racist insults at away games since 2013.

media

The Aborigines have been running their own television station, NITV, since 2007. It broadcasts non-stop and lets the natives report about themselves in order to counteract clichés and also to show positive developments.

See also

literature

- Geoffrey Blainey: The Triumph of the Nomads. A History of Aboriginal Australia. Overlook Press, New York 1976, ISBN 978-0-87951-043-5

- Wally Caruana: Aboriginal Art. German edition. Thames & Hudson, London 1999, ISBN 3-7852-8403-9 .

- Bruce Chatwin : Traumpfade ("The songlines"). Verlag der SZ , Munich 2004, ISBN 3-937793-28-3 .

- Ian Crawshaw: Australia walkabout - travel guide to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia . Editor of the German edition: Sabine Muschter. Intuitiv media, Kiel 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-029490-7 .

- Kate Darian-Smith, Juliane Lochner (translator): Indigenous Australia. From British colonization to the present. In: Bettina Biedermann, Heribert Dieter (Ed.): Country report Australia. Series of publications, 1275. Federal Agency for Civic Education BpB, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-8389-0175-6 , pp. 93–126

- Robyn Davidson: Tracks. Pan Macmillan Ltd, London 1998, ISBN 978-0-330-36861-2

- Ursula Dreyer: Dreaming Tracks - search for traces. On the way to intercultural dialogues. Kleio Humanities, Bremen 2006, ISBN 3-9811211-1-2 (also dissertation, University of Bremen 2006).

- AP Elkin: Aboriginal men of high degree. Initiation and Sorcery in the World's Oldest Tradition. Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont 1977, ISBN 978-0-89281-421-3 .

- Jürg Helbling: The organization of social and natural space among the Australian Aborigines. In: Paul Michel (Ed.): Symbolism of place and space. P. Lang, Bern 1997, ISBN 3-906759-19-9 , pp. 281-303.

- David Horton (Ed.): The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, society and culture. Aboriginal Studies Press (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies), Canberra 1994. Book version: ISBN 0-85575-234-3 , Windows CD-Rom 1996: ISBN 0-85575-261-0 Macintosh CD-Rom 1996 : ISBN 0-85575-278-5 .

- Robert Hughes: The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868. Vintage, London 2003, ISBN 0-09-945915-9

- Aboriginal Studies Press (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies), Canberra 1994. Book version: ISBN 0-85575-234-3 , Windows CD-Rom 1996: ISBN 0-85575-261-0 Macintosh CD-Rom 1996 : ISBN 0-85575-278-5 .

- Jennifer Isaacs: Bush Food. Aboriginal food and herbal medicine. Könnemann Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-8290-2191-7 .

- Robert Lawlor: Voices of the first day. Awakening in the aboriginal dreamtime. Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont 1991, ISBN 0-89281-355-5 .

- Gerhard Leitner: The Aborigines of Australia. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-50889-8 . 2nd edition: Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-50889-9 .

- Malcolm Prentis: A Concise Companion to Aboriginal History. English. Rosenberg Publishing, Dural Delivery Center NSW, Australia, ISBN 978-1-877058-62-2 .

- F. Rose: The Aborigines of Australia. Society and art. Leipzig 1969.

Web links

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS)

- Culture.gov.au - Australian Indigenous cultural heritage ( Memento of April 8, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- FromAnthrop

Individual evidence

- ↑ nlc.org.au ( Memento from January 19, 2013 in the Internet Archive ): History. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ N. Tindale (1974): Aboriginal Tribes of Australia. ISBN 0-520-02005-7 .

- ^ Map of Tindale (1974) Tribal Boundaries in Aboriginal Australia

- ↑ AIATIS: Aboriginal Australia ( Memento of February 13, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c ABS (1994) Year Book Australia

- ↑ a b c d e f g h ABS (2006) Population Characteristics. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians ( Memento from October 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF), accessed November 18, 2008.

- ↑ ABS (2002) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey .

- ↑ Duden-online , accessed April 26, 2009.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary: Aborigines , accessed April 5, 2009.

- ^ B. Ashcroft (2007): Post-colonial studies: the key concepts . ISBN 0-415-42855-6

- ↑ a b Julica Jungehülsing: The mission conscious. In: Geo Special Australia. Gruner + Jahr Hamburg, No. 6, 2013, pp. 70–75, p. 73, ISSN 0723-5194 .

- ↑ Duden online Aborigine , accessed July 2, 2012.

- ↑ Parliament of Australia (1981) The Definition of Aboriginality ( Memento of June 5, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ David Horten (Ed.) (1994): The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society and Culture. ISBN 0-85575-234-3 , quoted from AIATIS ( Memento from January 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ N. Peterson (1974): The natural and cultural areas of Aboriginal Australia. In Tribes and boundaries in Australia. ISBN 0-85575-048-0 .

- ^ D. Mulvaney (1999): Prehistory of Australia . ISBN 1-86448-950-2 , p. 78.

- ↑ Ewen Callaway: First Aboriginal genome sequenced . In: Nature News . September 22, 2011, doi : 10.1038 / news.2011.551 .

- ^ David Reich et al .: Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania . In: The American Journal of Human Genetics . tape 89 , no. 4 , October 7, 2011, p. 516-528 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ajhg.2011.09.005 , PMID 21944045 , PMC 3188841 (free full text).

- ^ Charles Choi: Now-Extinct Relative Had Sex with Humans Far and Wide. In: LiveScience . September 22, 2011, accessed October 6, 2013 .

- ↑ M. Ingman (2003): Genome Res. Mitochondrial Genome Variation and Evolutionary History of Australian and New Guinean Aborigines July 13; (7): pp. 1600-1606 PMID 12840039 .

- ^ AJ Redd: Gene flow from the Indian subcontinent to Australia: Evidence from the Y chromosome. In: Current Biology. Vol. 12, April 16, 2002, pp. 673-677, PMID 11967156 .

- ↑ John F. O'Connell, Jim Allen: Dating the colonization of Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea). In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 31, 2004, pp. 835-853.

- ↑ Ray Tobler, Adam Rohrlach, Julien Soubrier, Pere Bover, Bastien Llamas, Jonathan Tuke, Nigel Bean, Ali Abdullah-Highfold, Shane Agius, Amy O'Donoghue, Isabel O'Loughlin, Peter Sutton, Fran Zilio, Keryn Walshe, Alan N. Williams, Chris SM Turney, Matthew Williams, Stephen M. Richards, Robert J. Mitchell, Emma Kowal, John R. Stephen, Lesley Williams, Wolfgang Haak, Alan Cooper: Aboriginal mitogenomes reveal 50,000 years of regionalism in Australia. In: Nature. Volume 544, April 13, 2017, pp. 180-184, doi: 10.1038 / nature21416 .

- ↑ Aboriginal hair shows 50,000 years connection to country, March 9, 2017, adelaide.edu.au: online .

- ↑ Aborigines: 50,000 years "connected to their homeland". DNA analysis confirms the unique attachment of the Australian Aborigines to their land. March 8, 2017, www.shh.mpg.de: online .

- ^ Echoes of an ancient time in Australia. March 14, 2017 pangea.unsw.edu.au: online .