Cuneiform law

As cuneiform writing law (also in the plural cuneiform writing rights ) one describes the legal systems of the ancient oriental high cultures handed down in cuneiform sources , primarily the Sumerians , Akkadians , Assyrians , Babylonians , Elamers , Hittites and Hurrites .

It has been handed down primarily in the form of private legal documents, court documents and trial protocols that originate from the civil law area. In addition, there are occasional collections of laws that relate to regulations on private law, public law , service law and criminal law. In addition, decrees and instructions, international treaties, letters and a few other sources are available for the reconstruction of the cuneiform legal systems.

Research on cuneiform law was promoted in the first half of the 20th century mainly by German and Czech legal historians from the circles of Paul Koschaker and Mariano San Nicolò . Since her death, scientific activities in this field have mainly been carried out by representatives of Assyriology . French jurisprudence also dealt with cuneiform legal cultures very early on, but without a school comparable to the German one having developed there. In the meantime, cuneiform law has become an international field of research.

The interest of historical jurisprudence in the legal systems of the ancient oriental high cultures is primarily based on academia today. It is generally assumed that Greek and Roman law were influenced by the cuneiform legal systems, but so far it has not been possible to convincingly demonstrate a concrete reception of ancient oriental law in classical antiquity. Isolated attempts to do this, which are still being made to this day, mostly fail due to the lack of the necessary sources, so that they are always dependent on speculation. As a result, ancient oriental law can only be classified with difficulty in a “general legal development” which, above all, has today's European civil law as the end result. Modern jurisprudence therefore considers the practical importance of ancient oriental law to be rather low overall, which is why it has a very subordinate position in academic teaching at law faculties in Germany compared to Roman and Germanic law. There is greater interest on the part of biblical theology , which deals primarily with cuneiform law in the context of comparative law studies and which has been able to prove several receptions of cuneiform law in biblical law.

Research history

Research into cuneiform legal sources began in 1877 with the publication of the Documents juridiques de l'Assyrie et de la Chaldée by the legally trained Assyriologist Julius Oppert together with Joachim Ménant. This was followed by four publications by the legal historian Josef Kohler in cooperation with the Assyriologist Felix Ernst Peiser . In addition, there were around 300 texts of legal and business content published by Peiser in 1896 alone from all epochs of ancient Mesopotamia and a number of other publications by Johann Strassmaier , Knud Tallquist and Claude Johns, for example . After that, the investigation of cuneiform law stalled again.

In the winter of 1901/1902 Jacques de Morgan discovered the stele of the Codex Ḫammurapi on his expedition to Susa . His edition became the basis for a series of comparative law studies with the Old Testament. This was followed by publications of other ancient Babylonian legal documents by Kohler, Peiser, Moses Schorr , Édouard Cuq and Arthur Ungnad . In addition, the Leipzig law professor Paul Koschaker, in collaboration with Arthur Ungnad, Benno Landsberger , Heinrich Zimmer and Johannes Friedrich, made significant progress in research into ancient Eastern legal sources. He finally established the term "cuneiform law" and established research principles, which his Munich colleague Mariano San Nicolò followed in particular . Subsequently, at the chairs of Koschakers and Nicolòs in Leipzig and Munich, a series of monographic studies on cuneiform writing were carried out by their students Julius Georg Lautner, Martin David , Wilhelm Eilers , Josef Klíma and Viktor Korošec . Even Herbert Petschow studied with Koschaker and had later Gerhard Ries for students, which in turn teacher Guido Piper was. The term "cuneiform law" was initially used to describe the Assyrian-Babylonian legal history, after the solution of the Hittite problem by Bedřich Hrozný in the First World War, however, the "legal history of all peoples who use cuneiform to record their legal monuments (...)."

After the First World War, research into cuneiform rights experienced a boom. The first Sumerian, Hittite and Central Assyrian legal documents were published. The texts from Kültepe , Nuzi and Arrapḫa , Susa, Mari , Ugarit and Alalaḫ were added . After the Second World War, the Lipit-Ištar Codex was reconstructed and the laws of Ešnunna were discovered. In the period that followed, these sources were edited and commented on, so that a legal interpretation was attempted for almost every one of these ancient oriental collections of law. Overall, however, this work was mainly done by Assyriology, since the interest in ancient legal history, with a few exceptions such as Herbert Petschow, Gerhard Ries, Guido Pfeifer as well as Richard Haase and Raymond Westbrook , after the deaths of Koschaker and San Nicolòs 1950s mainly focused on Roman law again . Outside of Germany, too, the emerging research into cuneiform writing was mainly carried out by Assyriologists. In France, for example, Emile Szlechter, Elena Cassin and Denise Cocquerillat, in England Godfrey Rolles Driver in collaboration with John C. Miles, and in the Netherlands Anton van Praag presented corresponding studies. The French legal historian Guillaume Cardascia , who also dealt with ancient oriental law, was an exception . In the Soviet Union , too, researchers such as Igor Michailowitsch Djakonow , Alexander Ilyich Tyumenew and Magaziner dealt with this topic. There were also a few scientists in other countries, such as Sibylle Bolla in Austria, Giuseppe Furlani in Italy, Sedat Alp in Turkey, Raymond Philip Dougherty and Jacob Joel Finkelstein in the USA. All in all, the cuneiform sources of law have hardly been legally developed to this day and are even regarded by some legal historians as of little significance.

Interest in cuneiform legal documents has increased again over the past few years. On the part of jurisprudence, Raymond Westbrook, who has since died, was primarily concerned with ancient oriental law. In Germany, more recent contributions are from Guido Pfeifer and Jan Dirk Harke . In the field of Assyriology, numerous works on texts with legal content were created. Notable contributions were made by Hans Neumann , Cécile Michel, Sophie Démare-Lafont, Dominique Charpin, Francis Joannès, Cornelia Wunsch, Michael Jursa and others. Harry Angier Hoffner (Jr.) dealt specifically with Hittite law .

Sources

Cuneiform legal sources have come down to us from almost all epochs of the nearly 3000-year history of ancient Mesopotamia . They can be roughly divided into two groups, namely in legal documents written in clay and in legal collections recorded on various written carriers.

The former are available from around the later first half of the 3rd millennium BC and were initially written in Sumerian and later also in Akkadian . The majority of these are contracts that offer an insight into institutes of private law. They are supplemented by court documents, which are also primarily based on private law facts, but also provide insight into the organization of the judiciary and the practice of jurisprudence . Such sources come primarily from the context of archives, especially private archives, so that knowledge of private law fluctuates greatly in different regions and at different times depending on the number of such archives found.

From the end of the 3rd millennium BC The legal collections are added as a further source group. Starting with the Codex Ur-Nammu , they contain regulations on private law, service law , criminal law and commercial law . The question of whether they are examples of state demonstrations of will that provide information about legislative acts has not yet been finally clarified. In any case, they reflect the law in force at the time. These legal collections are mostly handed down in numerous copies that come from school contexts and thus also offer insights into legal training. This group of sources also includes numerous decrees , which initially mainly clarified social law issues, but later also contain various service instructions and the like. Its legislative character can hardly be doubted.

Intergovernmental agreements that attest to international legal relations between Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Egypt and other neighboring regions constitute a special case. However, it is disputed whether the term international law can be used here.

There are far fewer sources of law available in Anatolia than in Mesopotamia. Almost all of them date from the 2nd millennium BC. And can be traced back to the Indo-European people of the Hittites, whose legal ideas differ significantly from those of Mesopotamia. In contrast to Mesopotamia, there are hardly any private documents for Anatolia, so that knowledge about private law issues in everyday life must be drawn from around 200 paragraphs of the so-called Hittite laws . There are also sources of constitutional law such as the succession decree of Telipinu I and the Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty , but also declarations of allegiance , decrees and court records.

Despite the extensive sources, a coherent and systematic presentation of the cuneiform law is missing. There is also a lack of any legal or political theory or legal historical news, so that a comprehensive picture of the legal systems reproduced in cuneiform has not yet been able to be constructed.

Private law documents and court records

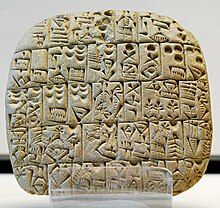

Certificates were usually written on clay tablets, which were 4 × 4 cm in size, were dried in the sun and were partially covered with a clay cover that reproduced their contents. These documents can be differentiated into business documents (contracts) and process documents on the basis of their characteristic form.

Business documents under private law were always objectively stylized as witness protocols until the Neo-Babylonian period . This is the description of the legal transaction. Their basic scheme always remains roughly identical:

- Subject of the contract

- Parties

- legal activity

- If applicable, a waiver clause or eviction clause

- Witnesses and scribes

- date

Such documents were sealed by at least one party who entered into a commitment. In this respect, the clay tablets, which are usually always made as evidence documents in Mesopotamian law, could have a dispositive effect - a fact that became increasingly important over the course of time. Often relatives of the selling party sealed the document, thereby simultaneously expressing a waiver of the assertion of rights of appeal . The other witnesses sealed to prove the authenticity of the document. That the seal was not a formal requirement is shown by the fact that, for example, certificates of obligation were often unsealed.

In the Neo-Babylonian period, a new document form appeared, which represented the legal transaction as a dialogue. The proposal and its acceptance by the contracting parties were presented as direct speech. The names of the parties and the legal activity moved to the beginning of the document. The latter was introduced by the formula “ina ḫud libbišu” (in the joy of his heart), which is regarded as the first approach to a will theory . Only the donation and disposition in the event of death remained objectively stylized in the Neo-Babylonian era, always describing the action of the seller.

A special group among the documents are the so-called Kudurrus , up to one meter high limestones, which were provided with representations of deities and god symbols in the upper area and in the lower part and on the following pages carried the text of a transfer of real estate. The term comes from the Middle Babylonian period , but is also used for similar monuments from other epochs and regions. They documented the transfer of collective property of a local social group into the private property of deserving private individuals and placed this transfer under the protection of the gods. When placed in public, they developed an abstract effect. The contracting parties were presumably issued a certificate about the respective legal transaction.

Process documents have come down to us in a relatively small number. In terms of content, they encompassed a broad spectrum and existed in the form of written judgments, usually only a few copies, provisional court minutes, memoranda of the scribes and much more. They came either from actual legal practice or from legal training. A systematic presentation of these documents from all epochs has not yet been presented. Such documents contain all the important data about the process: the opponents, allegations, evidence and the verdict. Above all, as judgments set out in writing, they served the trial winner as proof of the rights granted to him, which is why they usually remained with him. The Sumerian ditilla documents, which were kept in official archives, are an exception to this , although they too are primarily concerned with civil law disputes.

Legal collections, edicts, instructions

The best-known, if not the largest group of cuneiform legal sources are the legal collections, the majority of which date from the second half of the 3rd and the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. Are handed down. They can be roughly divided into so-called codes or collections of laws and decrees / edicts.

The few surviving collections of laws are the Sumerian codices Ur-Nammu (CU) (approx. 2100 BC), the Lipit-Ištar (CLI) (approx. 1900 BC), the Akkadian codices Ešnunna (CE) (approx . 1770 BC), the Ḫammurapi (CḪ) (approx. 1750 BC), the Central Assyrian Laws (MaG) (14th century BC) and the New Babylonian Law Fragment (NbGf) ( 7./6 Century BC) and the Hittite Laws (HG) (16th – 12th centuries BC).

They each consist of a legal and a non-legal part, whereby the legal part is made up of the so-called paragraphs. These are classifications of modern scientists based on the stylization of legal propositions. These legal clauses always contain a conditional clause that defines the regulated facts and is introduced by the words tukumbi (Sumerian) or šumma (Akkadian) as well as a main clause that defines the legal consequences. Formally, this formulation corresponds exactly to the expression in omen collections and in medical-diagnostic texts of the ancient Orient. Stefan Maul in particular therefore assumes that this is not just a formal closeness, but that based on the religious and ideological ideas behind the texts, it can be assumed that these genres have the same meaning. The compilation of the legal clauses follows a system based on external factual contexts.

The non-legal part is made up of the pro and epilogue , which differ from the legal clauses in terms of language and content. Based on literary templates and other inscriptions, the ruler is legitimized, his deeds are praised and general ethical convictions are presented. In particular, the king's concern for law and justice in the sense of maintaining the divine world order is thematized and used to legitimize legislation.

One of the decrees is the oldest known document of this kind, the reform texts of Urukagina , which were stylized as a contract between him and the city god Ningirsu and are handed down on three clay cones and an oval stone slab. They contain regulations in the area of tax law, marriage law, public safety, funeral fees and cult. This motive to eliminate grievances in the country is typical of ancient oriental decrees and edicts, which hardly made any determinations for the future, but mostly tried to eliminate existing problems. They mostly aimed at social and economic grievances. This also applies to three surviving decrees from ancient Babylonian times, which go back to Šamšu-iluna , Ammi-ṣaduqa and an unknown king. The decree of succession to the throne of Telipinu and the decree of Tudhalija IV are somewhat more recent .

State treaties

The intergovernmental treaties, which were recorded on various written carriers, form a special source of law in the ancient Orient. Corresponding documents were concluded between Babylonia and Assyria, between the Hittites and Egypt and between various principalities. All in all, the Hittite treaties are best attested and researched.

The oldest known intergovernmental agreement is the almost 4,500 year old vulture stele of the Eannatum of Lagaš . First there is a detailed report on a conflict between two rival cities . What follows is the core of the document, a peace treaty dictated by the victor , which the defeated opponent had to conjure up to six gods. Right-symbolic acts are then named. A friendship treaty with Lugal-kimaš-dudu von Uruk has also come down to us from Eannatum's nephew En-metena . Here the legal transaction is referred to as "fraternization". This name can still be found in the 14th century BC. In the international correspondence of the Egyptian pharaohs Amenophis III. and Akhenaten from Tell el-Amarna . During this time, two legal transactions were already distinguished in the friendship contract: the statute (Akkadian: riksu / rikiltu ), which is drawn up for the contractual partner, and the oath (Akkadian: mamītu ), which is taken upon acceptance of the partner's statute.

The better researched Hittite treaties are divided into vassal treaties and parity treaties. There was a form for the vassal contracts , which usually consisted of seven sections:

- Preamble with the name of the issuing ruler

- History and justification of the vassal's duty of loyalty

- actual contract terms

- Provisions on the safekeeping of the document

- Provisions on reading the document

- Invocation of the Divine Witnesses

- Curse and blessing formulas

Such treaties were unilateral agreements in which the ruler stipulated his conditions and the vassal swore an oath to accept them, parallel to the friendship treaties in Mesopotamia. As a rule, their content consisted of positive duties, especially in the military field, but also tribute payments as well as duties to cease and desist, which mainly related to the respective foreign policy. As a concession , the vassals were occasionally guaranteed the right of their descendants to succeed to the throne.

The structure of the parity state treaties differed only slightly from the form of the vassal treaties, whereby the fraternization with the contractual partner was named as the reason for the vassal's duty of loyalty. In contrast to the vassal agreements, these were bilateral agreements. Each party made regulations and made commitments. Such documents were usually issued in duplicate with one copy each in the language of the two parties. The ruler was always mentioned first on the tablet of his language. Otherwise the texts of both copies matched.

Indirect sources

In addition to the extensive legal sources and other legal texts, there are also a number of historical sources available from the Ancient Near East that offer insights into legal life.

Lexical lists form a special type of text that is typical of the ancient Orient. These are dictionary-like compilations of mostly Sumerian words or phrases and their Akkadian equivalents. These compilations were collected according to their subject area into series, which over time became canonical training texts, similar to the legal collections of definitions today. Two series are of particular importance for ancient oriental legal history, both of which come from the library of Aššurbanipal (7th century BC). The better known of the two is the ana ittīšu series , which contains numerous standard formulations for legal documents and some of them with explanatory examples. The other is the series ḪAR.ra , to which a precursor goes back to the early 2nd millennium BC. Exist. Early texts in this genre date from the early Babylonian period .

A considerable number of letters have survived from the ancient Orient, coming from almost all areas of public and private life. Such letters could, depending on the sender and the occasion, be a legal document themselves. They are mostly indirect sources because the sender is referring to applicable law. For example, ancient Assyrian law is known almost exclusively from letters from dealers.

Finally, historical documents and literary works can also provide information about legal ideas. This applies in particular to the inscriptions , annals and autobiographies of the rulers, who, in addition to their heroic deeds, often also report on their work in the field of legislation and jurisdiction. Therefore, these sources should only be evaluated with great caution, as they are tendentious and, above all, are based on the ideas of the rulers as to how the law should be structured and therefore do not necessarily depict real legal circumstances.

The same applies to the richly transmitted myths, legends and wisdom literature of the ancient Orient, some of which convey legal information. Here, too, caution is advised when excerpting .

Legislation and case law

Statutory and Common Law

The question of what courts based their decisions on is not always easy to answer for the ancient Orient. There is some evidence that courts relied on precedents and recognized previous decisions as a source of law. In the epilogue of the Codex Ḫammurapi it is emphasized that the person seeking law should refer to the words used there and thus get his or her right. However, there is no evidence of a citation of the legal sources in court, just as little as the verdicts related to it, at most the existence of a corresponding legal text was established. In particular, it must be assumed that the courts primarily applied customary law that was handed down in ancient traditions. This also explains why Hittite officials were instructed to judge according to local tradition.

legislation

In the ancient Orient, the king played the central role in legislation and jurisdiction, at least ideally. Ultimately, legitimized by the gods, he had to stand up for the maintenance of the world order, whereby he had to orientate himself primarily on two principles: On the one hand, the more static principle of truth or law (Sumerian nì-gi-na , Akkadian kittum ) and on the other hand the more dynamic principle of justice (Sumerian nì-si-sá , Akkadian mīšarum ). The practical exercise of this function by the king is difficult to prove. As legislators it occurs clearly only by decrees appears as a judge at least in individual law sets the legal collections him as for the neck jurisdiction identify responsible. To what extent this corresponded to reality cannot be determined based on the available documents. In the area of civil law, in particular, no direct influence of the king in the case law can be proven; rather, for pragmatic reasons, it can be assumed that litigation and case law were carried out by local bodies on behalf of the king. Legislation was usually made ad hoc to eliminate current problems. In addition, some scientists assume that legislation was not primarily used to create new law, but primarily to adapt existing regulations.

The legislative character emerges most clearly in the case of the decrees , which can essentially be assigned to three areas: Constitutional law , administrative law and commercial law . There are only a few examples of the former that regulate the relationship between palace and temple, the succession to the throne or the decision-making process of the council of elders. Ordinances on administrative law were usually addressed to high officials or institutions in the state apparatus and either laid down procedures or tried to counteract corruption. The most widespread effects were provided by commercial law decrees that either adjusted tariffs or canceled debts and were therefore also of importance for private individuals. For this reason, it must be assumed that they received validity through public announcement.

The so-called legal collections , whose character was hotly debated in science and which became known far beyond the boundaries of ancient oriental studies, enjoyed particular scientific interest . Since, according to their form, the direct setting of legal norms that cover many areas of legal relationships, legal historians have repeatedly referred to them as legal books, codifications of applicable law or reforms of applicable law. Assyriology was skeptical of the idea that it was a matter of promulgated law, and in some cases the documents were denied any legal character. In this way, the interpretations as dedicatory inscriptions, which extol the righteous deeds of the ruler or model laws for the training of lawyers, which collect but do not collect applicable law, were added as further possibilities to the legal understanding of these texts. The scientific discussion focused on the questions about the completeness of the codices, their systematics and their legal force, all of which, however, cannot be answered either positively or negatively, so that the place in the life of this type of monument has not yet been clarified.

Jurisprudence

In Mesopotamia several levels of authority developed with the central and supreme royal court, the provincial jurisdiction and local courts. A regulation as to when which of these instances could be invoked cannot be determined, but some legal collections indicate that capital crimes fell within the royal jurisdiction. Since Amar-sin's time at the latest , other judges have been appointed alongside the king and city princes. These were people from various professional groups who also held the office of di-ku 5 and maškim . The former was the actual judge, the other a kind of "investigating judge" who is usually translated as "commissioner" in secondary literature. From ancient Babylonian times, the judicial office was exercised by various officials, including in the area of royal jurisdiction the " grand judge" (diqu gallu) , in the area of provincial jurisdiction the governor (šakkanakkum) and at the local level the mayor of a city ( rabiānum or ḫazannum ) or the council of elders (šubītum) belonged.

Throughout all epochs it remains unclear whether the judicial office was more of a profession or a function. It is clear that there was no formalized legal training. But in different cases the same people appear again and again as judges, which suggests a more or less firm basis for this office. In any case, there was no term for a courthouse until the Neo-Babylonian period; instead, public places such as temples or gates were given as the place of the trial. Striking and ultimately only explainable through ideological ideas is that at the latest in the 1st millennium BC. The legal process was also transferred to the area of incantation and ritual practices.

A lawsuit was initiated by one of the disputing parties or, if royal interests were involved, by a government agency. Women and men could appear as plaintiffs, and slaves could do so in the Neo-Babylonian era. Only children are not proven as plaintiffs in any epoch of the ancient Orient. To initiate a civil process, a clay tablet was given to the officer in charge, whereupon a summons was sent to the opposing party. If he did not comply with the charge, he immediately lost the process. Alternatively, a lawsuit could be handed over directly to the opposing party. In ancient Babylonian times, the court examined the legal requirements and the judges initiated the proceedings.

A number of pieces of evidence were admitted in court. This included, in particular, the questioning of "experts", the unofficial and sworn testimony , the party oath, the documentary evidence and the divine judgment (ordal). If it turned out in the course of the taking of evidence that witnesses had given false testimony , they could be declared culprits. The party oath could also be an independent piece of evidence, whereby a distinction must be made between promissory (promising) and assertoric (affirming) oath. By taking the oath, the person making the statement entered the judgment area of a deity who would punish a false oath. The party oath was subsidiary to the witness oath, which is why most of the oaths were sworn by witnesses. Even if the oath of a single witness was sufficient for the decision-making, the courts of the Ur-III period had up to five witnesses swear their statements. The oath of the maškim (commissioner) was also of particular importance . Documentary evidence is documented differently in different epochs, with a special focus on the late Babylonian period. If a party was unable to provide the required document, it lost the process. It is noticeable that in the late third millennium, no previous court documents, so-called ditilla , were used, but the maškim of the first trial had to testify. In substance, the court decision was demonstrably binding from the end of the third millennium. A judgment could no longer be overturned in a second proceeding on the same matter. The ancient Babylonian judges passed a judgment called purussum after examining the dispute (awātum amārum) . Initially, it was postulated in research that this judgment could be accepted or rejected by the parties. The reason given was that documents had been found according to which the same matter could not be judged again (Akkadian tuppum la ragāmim ). This was considered evidence of the rejection of a judgment. This interpretation is significantly influenced by the doctrine of litis contestatio (defendant's rejection of the action) as a contract, which has now also become obsolete in Roman legal history. In fact, judgments are likely to be an authoritative display of will, the execution of which was mostly in the hands of the victorious party.

A considerable number of court documents reflect the entire evidence taken by the court. Subsequently, the taking of a specific oath was ordered in relation to this evidence. After the oath was taken by one or both parties to the dispute, a judgment was stipulated in these documents. On the other hand, there are documents that confirm the performance of an oath and pass a corresponding judgment. Therefore, a number of scientists assume that such processes will be terminated by a conditional judgment of evidence, so that after the alleged fact has been sworn in, the decision would have become unconditional without further ado.

The sources provide relatively little information on the jurisdiction in Anatolia . For example, the “ instance train ” is only known in its basic features. The beginnings of jurisprudence among the Hittites lay in the clan jurisdiction, in which the head of the clan of the injured party decided on the sentence. How far this right extended is shown not least by Article 49 of King Telipinu's succession decree , which excluded him from the jurisdiction of the neck and granted this power of judgment only to the head of the clan. It was not until the Middle Kingdom that jurisdiction passed from the patriarchs to the elders of a settlement. In the course of time, these too lost their influence, especially as the central power increased in importance. They were eventually replaced by functionaries called lú.meš DUGUD , whose exact position remains the subject of research. Your judgment was final. Those who revolted against it awaited the death penalty. The royal court was responsible for particularly serious offenses related to the palace, such as adultery, "sorcery" and "sodomy". But local courts were also able to present difficult cases there. Violation of such a judgment was threatened with the extermination of the entire family.

The procedure could regularly only be initiated in writing. No distinction was made between civil and criminal proceedings. Occasionally received trial protocols prove the outstanding importance of the witness evidence, but the documentary evidence was also permitted. Witnesses, like the parties to the dispute themselves, could be sworn in before a deity. If the evidence with these means did not succeed, the divine judgment in the form of a water ordal was possible as a last resort, but nothing is known about the evaluation.

Legal development

We do not know when in the ancient Orient or when the law came into being worldwide. It is probably a process that has lasted hundreds of thousands of years and resulted in the emergence of legal cultures. Only with the advent of writing do they become historically tangible, a process that began in Mesopotamia for the first time worldwide. Thus, the ancient oriental legal system is the oldest known in the world.

It is not a uniform legal system with a stringent development, but rather a product of different peoples and cultures with different languages in an area that at times extended from the Egyptian border to Iran. Sources from this area are available to very different degrees, with the beginning and end times in particular being strongly underrepresented. The ancient oriental legal history begins with the first documents written in pictographic script in Sumer in the first half of the third millennium BC and is nearing its end at the end of the fourth century BC. This means that there are no sources that attest to the clash and mutual influence of ancient oriental law with the legal system of the Hellenistic world.

3rd millennium BC Chr.

The earliest written evidence for a cuneiform law originated in the early dynastic period (2900 / 2800–2340 BC) in connection with the development of the first states and the hierarchization of society that came with it. These are so-called field purchase contracts that are set in stone. They come from the politically highly fragmented later Babylonia and from the Diyala area . From the 26th century BC, clay tablet finds were added, of which the 40 copies from Fāra form the most famous corpus , which for the first time offers a better insight into the legal system of this time. This material from private archives testifies to the private sector actions of the people of that time. The contracts have a uniform list form. The land acquisition at the time was therefore already an established legal institution that had the time of origination of the documents reached a developed stage already. It served as evidence to ward off possible contestations of the contract and, as is almost always the case with Mesopotamian cuneiform law, had no constitutive effect .

From the middle of the 3rd millennium BC The purchase of people, which is first documented in the legal documents from Girsu . This can be linked to the indebtedness of free sections of the population, which necessitated the sale of children or other family members into slavery . In contrast to the Fāra texts, however, the texts from Girsu do not come from private houses, but from the archive of the Baba temple administration , i.e. an institutional household. Accordingly, members of the ruling family or members of the administration appeared as buyers. In both archives it is clear that the legal validity of the transaction was confirmed by legal symbolic acts. In the case of Girsu, contractual penalties were also included in the contracts for the first time , which mainly related to a possible legal action against vindication . They promised the unlawful surrender plaintiff that the contract, made in the form of a barrel nail, would be slapped in the mouth, a threat of punishment that can be proven in Mesopotamian law in other eras as well.

The existence of established law is not clearly documented in the early dynastic period, but at least in the form of the so-called reform texts of the Urukagina of Lagaš there are clear indications of ordinances that were issued by state authority. Above all, they proclaimed restorative measures against grievances in economic and social life and contained a debt repayment waiver, as was also often carried out in later epochs of the ancient Orient on the occasion of a change of government. Already after Urukagina's seventh year of reign, Lagaš fell to Umma .

Significant changes in the Mesopotamian legal system occurred in the Akkad period (2340-2200 BC), when Sargon of Akkad established the first large territorial state . A large number of private contracts and court documents have come down to us from the area of this state, which included all of Mesopotamia and neighboring Elam . They were drawn up in Umma, Girsu, Adab , Nippur and Isin in Sumerian and in Kiš , Sippar , Ešnunna , Tutub and Ga-Sur in Akkadian and document the legal institutions of purchase, lease, rent, donation, loan, oaths and judicial decisions .

The largest group among the finds of legal documents are still the purchase contracts, which now had animals as their subject in addition to real estate and slaves. The most famous documents of this group are the Maništūšu Obelisk and the Stone of Sippar . Both are evidence of the purchase of arable land on a large scale. Corresponding private documents written on clay were still in the tradition of the early dynastic period, although their list-like character clearly declined. These documents followed a fixed scheme and for the first time contained declarations of liability in the event of a third party claim on the purchase item. A good insight into legal regulations is offered in particular by letters of obligation as debt certificates for purchased items for later payment. To secure these sales contracts, deposit orders and guarantees were common practice.

Within the procedural law in the Akkad period the separation between promissory and assertoric oaths took place, whereby the former was taken with invocation of the king, rarely a deity or high official, the latter always in the temple in front of symbols of the gods. The latter was used together with the river ordal as decisive evidence in court.

After a period of turmoil as a result of foreign rule by the Guteans and the formation of states in southern Babylonia, which ultimately could not prevail, Ur-Namma founded a territorial state from the city of Ur in the late 3rd millennium BC. The kings of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (2100–2000 BC) ruled there for around 100 years . Compared to the previous epochs, more legal documents are known from this period. These include, above all, the Codex Ur-Namma, which is supplemented by around 20,000 legal documents and ditilla documents from Nippur and Girsu . The latter were informal minutes of court hearings, which were then kept in the archives of the city prince. During the 3rd Dynasty of Ur these documents mainly dealt with personal and family law disputes. Commercial law and law of obligations can be derived from other private law documents.

The Codex Ur-Namma is only preserved in fragments in old Babylonian inscriptions, which probably go back to a stone monument. The total scope of the work is therefore not known - for the time being it is assumed that there are around 50 paragraphs. It is under discussion whether it is actually the dynasty founder Ur-Namma or rather his successor Šulgi . This codex serves primarily as a source for research into the handling of capital crimes, marriage law, slave law, real estate law, inheritance and liability law, with collective bargaining provisions as well as commercial and obligation law. It is known from legal documents that the death penalty was rarely imposed; property fines were more common.

The king played the crucial role in establishing and maintaining law and justice as divine principles. Therefore, he presented himself as a legislator and restorer, while his involvement in jurisprudence could only be proven in one case. The jurisdiction lay with the royal officials in the respective cities, which the énsi presided over as the highest judicial authority . A professional judiciary did not exist, the participation of the temple in the judiciary can only be proven in isolated cases.

2nd millennium BC Chr.

In the second millennium BC The sources on the ancient oriental legal systems are much more extensive. They no longer only come from southern Mesopotamia, but also from the neighboring regions of Syria , Anatolia and Iran and can be assigned to different peoples.

Babylonia

Old Babylonian time

After the fall of the empire of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, southern Mesopotamia was again characterized by a highly fragmented political landscape, with Amurrian princes increasingly at the head of the small states. This only changed with King Ḫammu-rapi of Babylon , who conquered almost all of Mesopotamia and united it in one state. For both periods of this ancient Babylonian period (2000–1596 BC) extensive sources on legal history are available, which in addition to legal collections and edicts as well as legal documents also include letters from which information about legal practice can be obtained.

The Codex Lipit-Ištar is a fragmentary legal collection from the early Babylonian period . It was reconstructed from clay tablet copies found in Nippur of a stele that had not yet been found and, in addition to the prologue and epilogue, contains around 40 Sumerian-language paragraphs that allegedly go back to King Lipit-Ištar of Isin . According to the prologue, it was linked to a debt cancellation waiver. Her legal part dealt in particular with questions of marriage and inheritance law, slave stealing and release, ship rental, property as well as liability and replacement obligations. None of the previously known paragraphs threaten the death penalty; instead there are references to compensation and fines in criminal law, which, with the exception of Section 17, did not follow the principle of talion . Legal collections also existed in other Sumerian cities of the early Babylonian epoch, but only a few fragments of these came to light in Kiš and Nippur. Then there are the three texts in the series ana ittīšu. Somewhat more recent is the Codex Ešnunna, the oldest Akkadian-language legal collection, which has also only survived in fragments in the form of clay tablet copies. It was found in Tell Ḥarmal (Šaduppum) . Only the legal part of this Codex has survived, which includes a preamble and 60 paragraphs that follow a complex order. They concern maximum prices and minimum wages, questions of contract law and criminal law. In addition to compensation and fines, the Codex Ešnunna also recognized the death penalty.

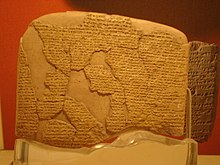

In contrast, the Codex Ḫammurapi is not only preserved in fragmentary clay tablet copies, but also in the form of an almost intact 2.25 m high diorite stele , which was probably originally set up in Sippar. Presumably copies existed in different cities. According to popular opinion, it is the most important collection of law in Mesopotamia. In addition to the prologue and epilogue, the Codex contains 282 paragraphs that were presumably copied over and over again for teaching purposes in all subsequent epochs of the Ancient Orient. They can be divided into two major sections, of which the first (§§ 1–41) deals primarily with public order (procedural law, capital offenses, duty to serve the king), while the second deals with private law (property law, family law, bodily harm and property damage, tenancy law, slave law). The death penalty is conspicuously common, or the Talion principle is applied. The above-mentioned penalties for offenses against a palace or temple are particularly severe. Especially in the case of Codex Ḫammurapi, its legal nature is repeatedly denied, since there are no references to the Codex in the legal documents that have been handed down. On the other hand, it is argued that legal practice was nevertheless followed in the sense of the Codammurapi Codex, even if it was not explicitly referred to.

In addition to the large collections of laws, edicts have been received from some rulers that have the fixed expression mīšaram šakānum (setting justice) in common. They were almost always decreed by the king at the beginning of his reign and usually contained debt and tax exemptions, the waiver of arrears and the exemption of debt slaves. Above all they served the restoration of the divine / public order by stabilizing the economic and social conditions. A mešarum edict of the Babylonian king Ammi-ṣaduqa , of which clay tablet copies were found in Sippar , also belongs to this group . In probably 22 paragraphs it ordered the cancellation of some taxes and arrears as well as private debts and the release of debt slaves. The coercion of royal service personnel to perform work in the private interest of civil servants was expressly prohibited and threatened with the death penalty. The legal validity of this edict is evidenced by a process document that directly refers to it.

The legal documents give a good insight into the jurisprudence in ancient Babylonian times. It is not uncommon for women to appear as legal subjects in the numerous private law documents, especially when it is a question of a widow, a divorced woman or a nadītum . The legal status of slaves had not changed significantly compared to the 3rd millennium. The legal documents document marriage and inheritance law as well as adoption, as well as surety and pledge, loan, purchase, lease and rent.

Central Babylonian Period

The empire of apammurapis already experienced its decline under his successors until his dynasty in 1595 BC. As a result of the conquest of Babylon by the Hittite Muršili I finally had to give up power. After a century with no historical sources , Babylonia was ruled by a dynasty of the Kassites (approx. 1475–1137 BC), presumably from the East Tigris region, who brought an era of calm and stability. Only a few sources of legal history are known from this period. They are limited to private law and court documents as well as the now prominent kudurrus, the majority of which are dated to the middle of the 14th to the middle of the 13th century. However, some texts have come down to us from the early Kassite empire Ḫana on the Middle Euphrates, i.e. from the period up to the 18th or early 17th century BC. Despite these unsatisfactory sources, the legal system of the Middle Babylonian period is of outstanding scientific importance, as it is the link between the better-known legal systems of the ancient and neo-Babylonian periods.

The well-known legal documents of the Middle Babylonian period dealt with the institutes of credit, marriage, employment, the sale of cattle , barter and especially purchase. The objects of the purchase contract were primarily movables, including slaves and cattle in particular, which were sold for natural goods, handicrafts or (other) cattle. Up until the 12th century, the purchase price to be paid was offset in gold, and thereafter in silver. Real estate purchase agreements have hardly been found at all, which is attributed to the coincidence of tradition .

Noticeable are the changes in the contract forms that began in the late Middle Babylonian period and were later finally established in the Neo-Babylonian period. From Šagarakti-šuriaš onwards, the wording in sales contracts changed, and the first "dialogue documents" also come from Nippur and Ur. It is noticeable that such contracts often contain liability for attempting a vindication, which was threatened either with double performance of the subject matter of the contract or with hammering a copper nail into the mouth of the vindicant.

Very little is known about the Kassite trial. However, according to the few documents from Nippur, jurisdiction was incumbent on the mayor (ḫazannu) , a regular judge (dajjānu) or, on the orders of the ruler, the governor (šandabakku) . In addition to the witness and party oath, the Wasserordal is also proven as evidence. A key find from the Middle Babylonian period are the kudurrus, stone documents that were set up in the temple and deal with royal donations of land. Such gifts could be made to the temple, priests, members of the ruling dynasty and high officials and could be associated with special privileges, but also obligations. Apparently, despite the donation, the king retained at least part of the power of disposal over the given land.

Assyria

Ancient Assyrian Period

In contrast to Babylonia, there are almost no sources for the ancient Assyrian legal system (approx. 2000–1750 BC) from Assyria itself. Instead, our knowledge is derived almost exclusively from the so-called Cappadocian tablets from central Turkey, especially from the location Kültepe , but also from excavations in Alışar Höyük and Boğazköy , the later Hittite capital Ḫattuša . Old Assyrian traders operated trading colonies there called kārum . Research assumes that these mainly from the 19th century BC. Texts originating in BC reflect the ancient Assyrian legal conceptions.

Some texts contain information on procedural law. Accordingly, the kārum had its own jurisdiction in internal affairs. The highest judicial decisions, however, lay with the city assembly of Aššur , the so-called bīt ālim . Obviously, the plaintiff could influence the choice of judge. From some documents it can also be seen that state law existed, which, however, is not directly attested in the texts found so far. In the contracts received between local residents of Kültepe, the death penalty was often threatened for breach of contract, but always subordinated to a fine. This applies equally to sales contracts as to marriage, adoption or inheritance contracts. In the contracts between Assyrian traders, however, the death penalty is completely absent, so that it must be attributed to the Anatolian legal system.

The traditional marriage contracts show that both partners are legally equal, regardless of whether the marriage was between natives, between Assyrians or between natives and Assyrians. Marriage certificates, which can be assigned to the Assyrian traders, grant the husband and wife a right to divorce and oblige both of them to pay a divorce price. Depending on whether a man in the kārum married a local or an Assyrian woman, he was permitted to marry again with a qadištum in Aššur. It is also noticeable that the testator was able to settle his estate himself in his will, whereby the wife or his biological descendants were usually favored.

The ancient Assyrian trade and obligation law is best known, which is documented in the numerous documents about transactions by ancient Assyrian traders. Common means of securing contracts were the guarantee and the pledge, whereby the guarantee occurred as a presentation and default guarantee. There was also joint and several liability . The deposit was usually a security deposit, not a replacement deposit. As a document about a debt, a so-called "debt document" was regularly issued, which, in contrast to the obligation note, did not name the reason for the debt.

Central Assyrian Period

In the ancient Assyrian period, under Šamši-Adad I, an Upper Mesopotamian Empire was established, which however soon perished in the course of the conquests of Ḫammurapis. It was not until the 14th century that northern Mesopotamia, the Central Assyrian state (1380 BC to 912 BC), was a major power that was in constant conflict with Babylonia and reappeared from the 11th century through the wars with the Arameans Lost influence. The legal historical sources of this epoch, most of which come from the capital Aššur, are extensive and include, in addition to private law documents, re-established law in the form of legal collections and decrees.

The so-called Central Assyrian Laws (MaG) are of particular importance as a fragmentary collection of legal propositions for research into Assyrian law. The clay tablets probably go back to the reign of Ninurta-apil-ekur in the 12th century BC. BC back. At least in part, they represent a compilation of older law. The better preserved panel A contains 59 paragraphs that deal with women and are therefore referred to as the mirror of women . These legal provisions concern criminal regulations for theft and stolen goods, blasphemy, bodily harm and homicides, sexual offenses and questions of marriage law. On panel B there are 20 more paragraphs that deal with property law. 13 other poorly preserved panels deal with movables (movable property), liability and inheritance law. The nature of the Central Assyrian laws is controversial because, unlike the Codex Ḫammurapi, for example, they represent a selective compilation of earlier law. It was therefore debated whether it was possibly a scholar's legal book rather than a demonstration of the will of a royal legislature. The law reflected in the Central Assyrian documents can be proven in some of the legal documents received as valid at that time.

The so-called court and harem decrees from the time of Tukulti-apil-Ešarra I can clearly be attributed to established law . Here, too, there is a compilation of legal rules, which until the time of Ashur-uballit I. decline. In particular, they regulated behavior at the royal palace and especially in the harem, with violations usually being severely punished.

There are also many legal documents that come from the excavations in Aššur. They include marriage and adoption contracts, sales contracts, but particularly numerous loan deeds. In contrast, relatively little is known about Central Assyrian procedural law. What is of particular interest, however, is the criminal law, which conferred penal power on the injured party and his relatives. In addition to the death penalty, penalties often included mutilation, beatings, property sentences and forced labor.

Hittite Empire

After the end of the Assyrian presence, central Turkey initially took its own path in its legal development. The Indo-European people of the Hittites produced a territorial empire there, which at times competed with the centers of power on the Nile, Euphrates and Tigris, but differed considerably in its legal system. In particular, collections of laws and decrees as well as constitutional contracts as well as some court protocols have survived. Private law documents, however, are missing in the source material.

A particularly important source are the so-called Hittite laws , sometimes also called Hittite legal clauses (HRS). With regard to their legal nature, it is assumed that these are the guiding principles of the royal court in whose archive they were found. They are handed down in the form of fragmentary clay tablets of different ages, which make it clear that they have changed over time and depending on local conditions. It is therefore probably a matter of statutory law, which was binding on subordinate, local courts. A temporal tendency from harder to milder penalties can be observed. The paragraphs were summarized by the ancient scribes in two tables, which were designated by their initial words "If a man" (takku LÚ-aš) and "If a vine" (takku GIŠ GEŠTIN-aš) . There are references to another tablet that was titled "Third Tablet: 'When a Man' '". In contrast to the legal collections from Mesopotamia, the division of paragraphs in the Hittite laws is not based on their stylization, but on the lines of separation drawn by the Hittite scribes. They deal with the killing of people, bodily harm, kidnapping, family law, unpunished killing, official duties, pets, theft, arson, agricultural law, collective bargaining law, religious and sexual criminal law. Its system is essentially based on the division into different legal areas, within which the legal property concerned was sorted according to the weight of the matter.

Various constitutional documents were also available from the Old Ethite period, including inscriptions on the rulers, but also the political will of Ḫattušilis I and the decree of the great king Telipinu . They mainly concern the regulation of the succession to the throne.

Numerous service instructions provide information about the internal structure of the Hittite state. Those about the so-called bēl madgalti (Lord of the Watch ) are particularly revealing . This was responsible for ensuring military security and civil order in provinces on the imperial border. He was particularly responsible for the jurisdiction in his area of responsibility. Other service instructions concern the relationship between slave and master and the sale of royal gifts.

Legal documents are available from all epochs of the Hittite Empire and consist mainly of international treaties and diplomatic correspondence with the rulers of Kizzuwatna , Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria and Aḫḫijavā . The most famous find of this group is the peace treaty with Egypt exhibited today in extracts in the UN building in New York . There are also numerous vassal treaties . In addition, some court documents have been preserved that deal with the embezzlement of royal beasts of burden, equipment and weapons.

Arrapḫa and Mukiš

After the disintegration of the old Babylonian state, some Hurrian dynasties came to power in northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia , which lay between the Hittite and Assyrian spheres of influence and were established during the second half of the second millennium BC. B.C. under the pressure of their two neighbors went down again. Several thousand clay tablets have come down to us from this time, which also contain legal historical information and most of them come from the excavations in Arrapḫa , Jorgan Tepe (both today in the city of Kirkuk ) and Tell Açana . They show that the Assyrian-Babylonian legal tradition had a considerable influence on these states. Some of them go back to the 3rd millennium BC.

Arrapḫa with the capital of the same name was part of the Mitanni Empire as a small kingdom . The legal documents found there in Nuzi (Jorgan Tepe) show that their form was strongly in the Babylonian tradition, while the conceptions of content were more closely related to the Assyrian ones. Local developments, which also include the use of local vocabulary, make it clear that this is not just a matter of adopting from other legal systems.

Little is known about the state law and jurisdiction of this petty kingdom. Apparently a person called ḫalzuḫlu , who was also the highest representative of the state, presided over the judges' college of the people's judiciary in Nuzi . However, the king was able to attract lawsuits. In relation to private law, loan documents and so-called sales adoptions have been preserved. Land was probably inalienable fiefdom that could only be exchanged. In order to circumvent this sales ban, the sales adoption was concluded, in which the seller formally adopted the buyer and bequeathed the land to be sold to him, whereas the buyer made his adoptive father a "gift" equal to the purchase price. A further development of this circumstance were the so-called tidennūtu transactions , in which the debtor gave the creditor a pledge for tidennūtu and was provided with capital for it. Within a certain period of time, the debtor could take back the pledge by returning the capital. When the contract was signed, a certain emphasis was placed on formalities. For example, when real estate was sold , witnesses named mušelmû were used , who may also act as trustees . In addition to these, an announcement (šudūtu) was usually always required before a legal transaction could be concluded.

Tell Açana was called Mukiš by the Hurrites and was a small Hurrian kingdom from whose archives several hundred clay tablets were unearthed. These also include some marriage-law documents that also attest to the existence of a terḫâtu performance for Mukiš. In addition, there are above all loan documents in which mostly family members of the debtor or the debtor himself were pledged. Guarantee and donation agreements are less represented. Two interstate extradition agreements with Kizzuwatna and Tunip have survived from the 15th century .

Ugarit

Wedge Written legal documents come from the port city of Ugarit on the Syrian Mediterranean coast, where the first time an alphabetic script was developed on the basis of cuneiform. Most of the legal documents found there were nevertheless written in Akkadian. These documents belong primarily in the context of the royal palace and are primarily intergovernmental agreements with the Hittites, in which tax payments and vassal obligations were agreed. In addition, there are letters and private legal documents that document emancipations , gifts, sales, manumissions as well as adoptions, barter contracts and inheritance divisions . It is noticeable that documents bearing the royal seal do not name any witnesses for the conclusion of the contract.

Elam

East of the Tigris, in today's Iranian province of Chuzestan, was the kingdom of Elam . It experienced a cultural development that ran parallel to Mesopotamia and repeatedly came into contact or conflict with Mesopotamia. A considerable number of cuneiform texts with legal content, the legal evaluation of which has so far been pending, originate from its capital Susa . Corresponding editions have been available in French since the 1930s.

1st millennium BC Chr.

Extensive sources of legal history from the first millennium BC inform us about the legal conceptions and legal practice of the people living at the time. However, these sources are extremely unevenly distributed. Almost every tradition of state legislation is missing, and protocols from jurisprudence are also rather rare, while no other epoch has such a large number of private law documents. In addition, the cuneiform tradition continued into the Arsakid period , but in previous epochs such writing carriers were increasingly used which, unlike clay tablets, are now gone and lost forever. For this reason, sources of legal history are not equally available from all periods of the first millennium. In the later epochs in particular, when the ancient Orient came into contact with the European high cultures, they are increasingly missing.

Babylonia

The Kassite rule ended with an Elamite invasion in the 12th century. The stele of the Codex Ḫammurapi was stolen. There followed a phase of general loss of power in the Middle East, which was often associated with the Sea Peoples . At the same time, the Aramaeans spread , especially in Mesopotamia. From this epoch there is largely a lack of relevant legal history. Legal documents are only preserved from the Neo-Babylonian period (8th century - 626 BC), when Babylonia was under Assyrian rule, as well as from the late Babylonian period (626 BC - approx. 1st century BC) , with the finds becoming increasingly sparse. Babylonia never went under, but came under the rule of the local Chaldean dynasty , later the Achaemenids and, with the conquests of Alexander, under the Macedonians , the Seleucids , and finally the Arsacids and Parthians . The legal development was continuous, only a few technical modifications under the Persian rule suggest changes in legal thought.

With the Neo-Babylonian law fragment (NbGF) there is only one legal collection from this epoch . It is a student copy from the 7th or 6th century BC. BC, which, according to prevailing opinion, reflects the law applicable at the time. A total of 15 paragraphs have survived on this fragment, which presumably represent an excerpt from various models. It is about questions of real estate law, compensation, sales law and marriage law. Unlike the collections of laws, the legal clauses are formulated in a relative way, i.e. the introduction šumma was only used for additions to a main case.

Occasionally there are references to a legislative activity of the kings, such as corresponding epithets in the inscriptions of Nabu-apla-usur and Nabu-kudurri-usur I as well as indications in inscriptions and literary compositions of the Nergal-šarra-usur and the Nabû- nāʾid . Legislative activity is also assumed for the Achaemenid rulers. Last but not least, the private law documents also repeatedly refer to royal statutes.

The surviving legal documents attest to many legal relationships that are already known from previous eras. They come mainly from the private archives of rich families, especially the Egibi families from Babylon and Murašû from Nippur. There are some differences between these documents and previous eras. This includes the fact that the clay tablet covers fell out of use, rather duplicates of the tablets were made to prove their authenticity. There was also an increasing number of dialogue documents that fixed the cause and content of the contractual agreement and are therefore of particular scientific value. For the first time in legal history, the consent of both contractual partners was very clearly expressed as a prerequisite for the legal transaction to take place. The emphasis on the voluntary nature of the contract offer by the formula ina ḫud libbišu may also belong in this context .

Most legal documents come from the law of obligations. The justification of corporate relationships is often proven. The capital contribution was made according to the documents ana ḫarrāni . There are numerous sales contracts, whereby these had different forms for the sale of real estate and vehicles, a differentiation that was abandoned from the Hellenistic period in favor of the vehicle purchase form. Changes in the guarantee clauses also suggest that an originally necessary contingent was no longer necessary in later epochs.

Assyria

After its temporary loss of power, the Assyrian Empire took off from the 9th century BC. A supremacy in the Middle East and thus became the first empire in this region. By the middle of the 7th century it extended its rule to Egypt and Iran, half a century later it collapsed completely under the joint onslaught of Babylonians and Medes . There are no references to state legislation from this era, so only legal documents are available as sources. These come mainly from the capitals of the kingdom of Nineveh , Kalḫu and Aššur.

A few procedural documents inform us about the Neo-Assyrian jurisdiction. As a rule, this was in the hands of individual administrative officials, less often with judges. Courts only took action if an out-of-court dispute settlement failed; In this case the plaintiff could forcibly bring the defendant before him. Homicides were initially only punished with an atonement to the son of the victim; a death sentence was only passed if this atonement could not be performed. In the event of such a performance judgment or if the indictment was dismissed, the parties had to declare that they would waive further legal action, the disregard of which would result in fines.

Documents under private law provide information, in particular, about the legal institutions of marriage and purchase as well as about the law of obligations. So several purchase marriages are passed down, which probably came about out of the need of the seller. It is unclear what legal status the woman sold in this way was assigned. Conventional marriages in which the woman enjoyed personal protection and economic security are also documented. Overall, however, Assyrian women had fewer rights than women living in Babylonia at the same time.

Areas of law

A reconstruction of individual areas of law is difficult for the ancient Orient. This is mainly due to the fact that collections of laws primarily contained innovations, while all the rest of the law was generally known and therefore did not have to be recorded. The existing legal documents give only a scant insight into the legal practice of the time. At the same time, our modern division into areas of law , which ultimately goes back to Pandectistics , is not applicable to the ancient Orient. Because completely different classifications were used there, for example according to subject groups or according to the weight of the legal interest. The following subdivision is therefore artificial.

Constitutional law

In the ancient Orient , roughly at the same time as Egypt, associations of people formed for the first time in human history, for whom the term state can be used. These were city-states with centralized administration, which mainly developed extensive territories through military conquests. However, these were not states in the sense of national territory, state people and state power with internal and external sovereignty , but communities with a differentiating social hierarchy and different areas of power. The ancient oriental state was closely linked to mythological and religious ideas and can only be understood against this background. The ancient Orient saw man's task primarily in caring for the gods; the state, and especially the ruler, had primarily to ensure this supply. The conception of the state has undergone a considerable change in the approximately 3000-year history of the ancient Orient, the details of which cannot yet be traced.

Mesopotamia

Royalty

The Sumerian state was headed by a ruler who, differing from place to place, called himself en (lord), lugal (king; literally: great man) or ensi (representative [of the city god]). In particular, the ensi was responsible for the administration of divine property and the execution of divine instructions as well as the maintenance of public order. At the same time he was the chief commander of the armed forces and representative of his city-state. Overall, the Sumerian state saw itself as a secondary structure of the actually divine state, an economic-religious system, which Anton Moortgat in 1945 characterized as almost " theocratic state socialism". With the unken , the ruler was supported by a council, which presumably consisted of a council of elders and a citizens' assembly and had a certain amount of decision-making space that restricted the ruler's sphere of influence.

In the Babylonian state nothing fundamental changed in this view, even if its concrete construction was different. Thus the secular state was an organ of government of the divine state, presided over by a king proclaimed by the gods. This king of the gods made use of the secular ruler (lugal), who acted as trustee for him on earth. Enlil was initially considered the king of the gods . Therefore the kingship was sometimes referred to as "enlilschaft". In ancient Babylonian times, Marduk , the city god of Babylon , was declared king of the gods, to whom a Babylonian was to be subordinated as a profane ruler. The gods chose Ḫammurapi by voting for this office. A divine choice had already made Išme-Dagon of Isin king there. Likewise, the gods could remove their king of gods from his office and transfer this to another, whereupon the city in question suffered with its gods. This reflects, for example, the Ibbi Sîn lament for the fall of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur .

The Assyrian State knows the iššiaku one the Sumerian ENSAG comparable figure.

State apparatus

The ancient oriental states quickly formed an administrative apparatus with the king at its head. As early as the third millennium there was a social class that was subordinate to the king and temple, but was above the normal people. They were commanders of the military, officials in accounting, administration and jurisdiction, the so-called "courtiers", a class of servants in Babylonia that was dependent on the king. They fulfilled the tasks of the executive and judicial branches ; the ruler exercised the legislature . In the course of time, the administration has differentiated itself into three levels: central, provincial and local administration:

The central administration , the palace with the king, had lands and possessions and regulated state affairs. The palace acted as a legal entity on behalf of the king. Officials in charge of the provincial administration were appointed directly by the ruler. As his representatives, they were always accountable to him. The local government was a governor, which often an assembly of free citizens stood to the side. These free citizens usually came from the local population. This principle of collegiality can be demonstrated particularly well in ancient Assyrian times. The rich families belonged to a council assembly ( bīt ālim , or in the trading colonies bīt kārim ), which the prince led as primus inter pares . It was not until the 14th century that the Assyrian ruler called himself “king”. Its power continued to be restricted mainly by a military aristocracy. The lowest administrative level was assigned the tasks of local self-government and jurisdiction; but also the implementation of instructions from higher-level authorities, in particular with regard to taxes and work, was part of her area of responsibility.

In addition to the secular, religiously legitimized ruler, the temple and the priesthood formed a second power in the ancient East . Up until the time of Ḫammurapi, priests in particular exercised the judiciary. The temples were independent economic units, some of which accumulated considerable wealth and had their own jurisdiction for internal affairs.

Anatolia

The Hittite state most closely resembled a corporation , with the king as head and his clan as members.

king

At all times of the Hittite Empire, the king referred to himself as the administrator of the weather god Tarḫunna and the sun goddess of Arinna , who were the actual owners of the land. He was accountable to them, just as he had to ensure the goodwill of the gods by keeping the strict festival calendar. In relation to his people and his vassals, the king remained lifted and allowed himself to be addressed as “great king”, later as “my sun”. He was usually deified post mortem.

There were frequent throne turmoil at the Hittite royal court. In order to prevent regicide , Telipinu issued a comprehensive regulation of succession to the throne in his constitution. With this he probably introduced an electoral kingship , with the popular assembly (erín.meš) choosing the ruler from the royal clan.

queen

The queen stood by the king's side as a tawananna . She held this office throughout her life. However, the king's wife could only take up this position after the death of her predecessor; until then she was called "the king's wife". According to Richard Haase , it may be a relic of a mother's right . Tawanannas had a significant influence in the Hittite state. From Mursili II. Is known that he originally from Babylonia Tawannana Gaššulawiya was accused of witchcraft and condemned. However, he could not impose the death penalty. Puduḫepa , the wife of his son Ḫattušili III. , is best known for her diplomatic correspondence with Pharaoh Ramses II .

aristocracy

The king was provided with a hierarchically structured administrative apparatus made up of functionaries. At its head were the "great", members of the royal clan and the pankuš . What is meant by the latter has not yet been clarified beyond doubt. The princes and lords had an advisory role in intra-dynastic matters, while they otherwise supervised the administrative apparatus. The great were obliged to be particularly loyal to the king and were particularly liable. Delicts that were specifically punished included breach of faith, betrayal of secrets , spreading false news, complicity in attempts to overthrow and assassinate the king, defamation of relatives of the king, failure to provide assistance to the king and offenses in connection with women.

The "governors" were subordinate to the big players, and a letter with official instructions provided information about their legal status. Accordingly, they had military tasks in particular, such as maintaining the military readiness. In addition, they exercised the office of judge in private law disputes as well as in criminal proceedings. They were allowed to pass death or banishment sentences, depending on local custom. A complaint was to be submitted to them with a sealed, written document, after which the governor had to examine the matter and, if necessary, submit it to the king. They were committed to impartiality and incorruptibility. At the communal level, the "elders" and "city councilors" in particular also carried out police duties. For example, a find had to be presented to the elders , while the mayor was primarily responsible for public safety. As a rule, the functionaries were not paid, but received inheritable lands as alimentation from which they could generate profits.

In the time of the Great Empire, the establishment of the great as part of the state structure was abolished in order not to endanger the royal sphere of influence.

"International law"

The term “international law” cannot simply be applied to the Ancient Near East, as there is only limited supranational legal order that is not necessarily based on equality. The concept of the state cannot be equated with ours either. In particular, the concept of international law is even more problematic, since the idea of the nation state only emerged in modern European times.

Nevertheless, there was a considerable amount of interstate legal relations in the ancient Orient, which is already documented in the first legal historical documents. In addition, there are over 40 received contracts from all eras, which in turn refer to numerous other agreements.

The peculiarity of the ancient oriental "international law" results from the understanding of the state as a royal household. As the lord of this household, the king could enter into binding obligations for the members of his house, i.e. his people. Accordingly, this intergovernmental law was based on the general and, above all, private law ideas of the states involved. In contrast to private law, however, there was no court against which the king was accountable. Instead, he was subject to the direct jurisdiction of the gods, who could express themselves either in self-help by a ruler whose rights were violated - in execution of the divine counsel - or in disasters or military defeats. Since the existence of the gods was never questioned, every king sought their consent first before a military conflict. Because different gods were worshiped by different peoples, this system could only function on the basis of religious tolerance.

With the rise of the first great empires, which surrounded their heartland with vassal states, this system became more complicated. As a rule, these vassals were subordinate to the great king, but to varying degrees could themselves act as subjects of international law, which resulted in extremely complex interstate relationships.

Martial law

On the whole, statements on martial law are not very reliable. Hostilities were sometimes preceded by a formal declaration of war , even if it was probably not absolutely necessary. Prisoners of war were at the mercy of the enemy ruler - they were either murdered, enslaved, or sold. Civilians were also considered prey.

diplomacy