Zionism

Zionism (from " Zion ", the name of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and designation for the residence of YHWH , the God of the Israelites ) denotes a national movement and nationalist ideology that aims at a Jewish nation state in Palestine , wants to preserve and justify it.

Historical roots

Antiquity

The term "Zionism" refers to Zion as the name for the Temple Mount in Jerusalem . After the destruction of around 800 BC The first Jerusalem temple was built there (586 BC) and the exile of a large part of the Judeans, Zion in Babylonian exile (586-539 BC) became a synonym for the temple city and the hopes of Judaism associated with its reconstruction .

Since the fall of the northern Reich of Israel (722 BC) and the southern Reich of Judah (586 BC ), exiled Jews formed communities outside of the heartland of Israel ( Jewish Diaspora , Hebrew Galuth ). Her hope of a return to Zion and the renewal of her own community in Israel was awakened by prophets who, in exile, announced the return of the Judeans deported to Babylon and the rebuilding of the temple cult in their own country. They referred the promised gathering of all Jews scattered in the land of Israel on the land, populous and promise of blessing of YHWH to Abraham ( Gen 12.1-3; 17.8 EU ), with the Tanakh , the history of Israel begins. With this they linked the expectation that one day all peoples would recognize the God of Israel and obey his disarmament law. This will bring about peace between nations ( Isa 2,3f EU ; Mi 4,2f EU ; see swords for plowshares ).

After the conquest of Babylon by the Persians , the Jews were able to use it in 538 BC. Returned to their homeland of Israel, but several Jewish diaspora communities remained.

There were repeated revolts by Jews against the Roman rule over Judea . The Romans triumphed in the Jewish War (66–70), destroyed the second Jerusalem temple and deported numerous residents of Judea to Rome. After the Bar Kochba uprising (135), the Romans forbade the Jews to settle in Jerusalem and renamed the province of Judea to Syria Palestine . Tiberias became the Jewish center there , but most of the Jews settled outside Palestine. The connection to the biblical “promised land” and the longing for Zion remained. In Judaism's daily prayer of eighteen , the plea for the early rebuilding of Jerusalem and thus for the renewal of Israel is contained.

middle age

In late antiquity and in the early Middle Ages , the Jews initially lived as tolerated minorities in numerous diaspora communities. With the spread of Christianity , the situation of Jews in Christian countries worsened. The Jewish communities remaining in Palestine were almost exterminated by the Crusaders in 1096, during the First Crusade . In the 12th century, Jews began to express their longing for Eretz Israel more and more. The Spanish-Jewish poet Yehuda ha-Levi , author of the songs of Zion , died presumably in 1141 on the crossing to the promised land, the Jewish doctor and scholar Moses ben Maimon , who died in Cairo in 1204 , was buried in Tiberias according to his wishes . Between 1210 and 1211 a large number of French Tosafists went to Palestine in order to settle there permanently ( immigration of the three hundred rabbis ).

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain (1492) and Portugal , the Ottoman Empire took in many persecuted Jews, some of whom settled in Palestine. In Safed they formed a new theological center of Judaism of that time. Here the Kabbalah was cultivated, the Shulchan Aruch and the Zohar were printed. In it the land of Israel was declared to be the center of the world, in which God "dwells" ( Shechina ). Therefore the redemption of all peoples depends on the return of the Israelites.

Early modern age

In the 17th century, large groups of European Jews tried again and again to emigrate to Israel. They often gathered around rabbis who promised the dawn of a messianic age : for example Isaiah Horovitz in Prague in 1621 , but especially Shabbtai Zvi , who declared himself the Messiah in 1666 and, even after his forced conversion to Islam, aroused expectations that all scattered Jews would return home soon. His followers declared 1706 the year of his return. Judah ha-Hasid gathered those willing to leave the country and in 1700 reached Jerusalem with about 1000 followers, where about 1200 Jews lived at that time. His followers built the Hurva Synagogue on the land he had bought . But Judas' death, just days after buying the property, caused many of his followers to leave the city or to convert to other religions. The Hurva Synagogue was completely destroyed in the Arab-Israeli War in 1948 and only rebuilt sixty years later and re-inaugurated on March 15, 2010.

Advocates of English Puritanism believed that they could bring about first the admission of Jews to England, then the return of all scattered Jews to Israel as promised in the Bible ( restoration of the jews ) and then their conversion to Christ as a preliminary stage of the end times. Henry Finch wrote the book The Worlds Great Restoration in 1621 . Or, the Calling of the Jewes . At their request, Oliver Cromwell lifted the ban on settling Jews in England, which had existed since 1290, in 1655. After his death, the idea of a Jewish settlement in Palestine remained popular with all Christian denominations in England and was advocated by Enlightenment figures such as John Locke and Isaac Newton . Corresponding ideas are widespread in Christian Zionism up to the present day.

In the wake of Hasidism , which emerged around 1750, some Hasidic Jews settled in Safed . After the Ottoman rulers imposed high taxes and tariffs on the Jewish communities of Palestine , many Jewish immigrants left the country again. Around 1800 there were only about 5,000 Jews living in Palestine.

Conditions of origin

European nationalism and colonialism

From 1789 onwards, the upswing of European nation-states intensified their competitive struggles for supremacy in the Middle East. Now liberal philanthropists and philosemites developed plans for Jewish communities outside Europe. In 1833 the viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali , started an uprising in Syria and Palestine, which led to their de facto separation from the Ottoman Empire. In Great Britain, government circles then considered settling Jews without an autonomous state in a self-governing Palestine in order to preserve the Ottoman Empire. In 1838 the Globe , organ of the British Foreign Office, first described this idea. The Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews , founded in 1809 , the first European organization for Jewish mission , influenced British Middle East policy under Lord Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) with neo-Puritan conversion and settlement plans for Jews.

In 1840 the Damascus affair led to pogroms against Jews in Syria. The British government then marched into Damascus. Their representatives justified this as a contribution to the national emancipation of the Palestinian and European Jews.

In Switzerland , Henry Dunant (1828–1910), the founder of the Red Cross , advocated the settlement of Jews in Palestine.

Jewish settlement projects

Mordechai Immanuel Noah (1785-1851), Consul of the USA in Tunis until 1815, after his recall, advocated the idea of a Jewish city of his own as a place of refuge for all persecuted Jews before Palestine could be repossessed. In 1825 he founded the city of Ararat on Grand Island , New York . He promoted immigration to Jewish communities internationally, but met with widespread rejection and ridicule. In Germany only a few members of the Association for Culture and Science of the Jews considered emigrating. Noah published his Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews in 1844 , an appeal to support a Jewish state in Palestine.

Sir Moses Montefiore (1784–1885) first traveled to Palestine in 1827 and then became a strict believer. From then on, he planned to promote Jewish emigration to the “promised land” financially as well as through industrial and agricultural settlements. In 1840 he prevented further pogroms in the Ottoman Empire through his visit . He planned a settlement project, bought land from large Arab landowners in Palestine and made it available to persecuted Jews. In 1857 he founded the first new Jewish settlement outside the old city of Jerusalem after the Jewish quarter there had become too small for the newcomers.

The French Adolphe Crémieux (1796–1880) founded the Alliance Israélite Universelle AIU in 1860 . This promoted only limited immigration of European Jews who were at risk in their homeland to Palestine, and also to other areas, for example in Latin America, on an equal footing. Because of its cosmopolitanism , the AIU expressly rejected mass immigration of Jews into a single country; this endangers the security of all Jews. Among other things, she tried to dissuade the Ottomans from allowing greater immigration to Palestine.

Most European Jews rejected emigration to Palestine and the program of a Zionist nation. The Orthodox Judaism condemned with the exception of national religious founded in 1902. Mizrachi the creation of a Jewish state as blasphemy and breaking of the Torah . Only God could free the Jews from the diaspora , for which they would have to wait until the arrival of the Messiah . Liberal Jews viewed themselves as members of their respective nations and stood up for their emancipation , which should bring them more religious tolerance and democratic rights. They viewed Zionism as a threat to their social assimilation and a betrayal of their nation, as well as a factor that encouraged anti-Semitism. Both the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith in the German Reich and the Bund in Wilna , representing the Jewish workers in Eastern Europe, represented anti-Zionist views and founded appropriate committees .

For Jewish historians like Jakob Katz , authors who contributed directly to the emergence of Zionism in religious Judaism are regarded as Mevassre Zion (“harbingers of the Zion idea”) . Rabbi Judah Alkalai (1798–1878) from Sarajevo, for example, published his work Hear Israel in 1834 ; The gift of Judah followed in 1845 . In it he declared simply waiting for God's redemption to be wrong. Rather, this begins with the Jews' own efforts: “They have to unite and organize, elect leaders and leave their exile. [...] The organization of an international corporation is already the first step towards salvation. The Messiah, son of Joseph, will emerge from the midst of the elders. This was the first time that a traditionally socialized rabbi combined orthodox belief in the Messiah with modern democratic politics.

Zwi Hirsch Kalischer (1795–1874) from Thorn wrote the book Drischath Zion (Zion's Production) in 1861 . Only in Palestine are the Jewish people safe from further dispersion, dissolution and persecution and can recognize their destiny. In this struggle for national independence, the Jews should take the nationalism of the European peoples as an example: “If many Jews settle [in the land of Israel] and their prayers increase on the holy mountain, then the Creator will answer them and the day of redemption accelerate. ”Both rabbis initiated a rethinking in Jewish orthodoxy that prepared the later Zionist movement.

Not all groups of Orthodoxy joined the secular Zionist program: In 1912 the Agudat Jisra'el was founded, which is still critical of the secular program today. The Neturei Karta , founded in 1938, also rejects the Israeli state.

The early socialist Moses Hess (1812–1875) wrote Rome and Jerusalem in 1862 with the subtitle The Last Nationality Question . In it he saw the epoch after the French Revolution as the "spring of nations" in which one nation after another awakens to a new national life. After Italy (“Rome”), which achieved its national statehood in 1859, the last turn was the Jewish people, “which not for nothing has defied the storm of world history for two millennia and [...] always from all corners of the world directed towards Jerusalem and is still judging. ”With this, Hess was the first modern Jewish author to express the idea of a Jewish nation in the“ promised land ”. He believed that the Jewish repopulation of Palestine was the prerequisite for a revitalized Jewish culture that was gradually dying away in the diaspora in Europe: “With the Jews, far more than with the nations that are oppressed on their own soil, everyone must have national independence precede political and social progress. "

The book did not yet describe any practical settlement steps and in 1862 received little public attention. It did not find enthusiastic approval from the Zionists until the 1890s. From then on, Hess was considered the founder of socialist Zionism, from which the kibbutz movement and the Israeli Labor Party later emerged.

anti-Semitism

In the 19th century, anti-Semitism spread as a political ideology in Europe, especially in Russia , Germany , Austria and France . Its aim was the exclusion and expulsion of all, including the baptized and socially integrated Jews. The limitation and withdrawal of recently acquired civil rights of the Jews also demanded bourgeois and Christian-conservative social circles, as the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute showed. This challenged all promises of liberalism of equality and tolerance and made them appear more and more like an illusion.

In March 1881 there was a wave of pogroms in Russia , which marked the beginning of further serious riots against Jews in the following years. They were often initiated or led by local authorities and tolerated and fueled by tsarism .

First Aliyah

The Russian pogroms from 1882 to 1903 caused an uncoordinated flight of Jews from Eastern Europe to various destinations. Some groups wanted to acquire their own settlement areas in the USA in order to build socialist communities there. They referred to themselves as Am Olam ("world people") and demarcated themselves from those who preferred to go to Palestine. However, their plans failed in the following years.

Only a fraction of emigrating Jews chose Palestine as their new home. Eastern European Jewish families had gradually settled there since around 1870. As farmers, they practiced arable farming and cattle breeding and cultivated desert land for this purpose. This perspective seemed obvious to many simple and religious Jews, but was hardly determined and organized by Zionist motives. By 1904 their number had grown to around 24,000, mostly Eastern European Jews.

History until 1945

Chibbat Zion

The Eastern European collection movement Chibbat Zion (“ Zion's love”) , which emerged from 1880, is considered to be the actual beginning of the Zionist movement . Their local associations were represented in many Russian and Romanian cities and called themselves Chowewe Zion ("Friends of Zion"). They gathered around 3,000 people willing to emigrate for joint settlement projects in Palestine. In the summer of 1882, the Bilu student group was the first to achieve this goal and built the settlement of Rishon-le-Zion ("First in Zion").

This pioneering work with the plow became a model for other groups of settlers. This is how Gedera came into being in the former Judea , Rosh Pinah and Yesod Hamaalah in Galilee , and Zichron Ja'akow in Samaria . The Petach Tikwah settlement north of Jaffa , founded by Jews from Jerusalem in 1878 , was renewed.

Leo Pinsker

Until 1881 the doctor Leo Pinsker (1821-1891) had strictly rejected national Jewish efforts in his hometown of Odessa . Under the influence of the nationwide pogroms, he traveled to Western Europe in order to sound out the willingness to accept persecuted Russian Jews. In the summer of 1882 he wrote the book Autoemancipation in Berlin in a few weeks and warned: " To be looted as a Jew or to be protected as a Jew is equally shameful and equally embarrassing for the human feeling of the Jews." The core of the problem is their exclusion by the Hatred of their environment. Its cause is the adherence of the scattered Jewish communities to their unity as Judaism. This had the effect of the “ghostly apparition of a walking dead” on the peoples of Europe and triggered a “judophobia”. All the often illogical arguments put forward by the enemies of the Jews are only a rational concealment of their deep psychosis , which has been inherited for 2000 years. This disease can only be cured by removing its cause, the extraordinary situation of the Jews. Like all other peoples, they must finally have their own homeland, a state, in order to be on a par with other nations. Only the Jews themselves could achieve this “solution to the Jewish question ”. Not the granting of their equality by others, but only their self-liberation as an independent and self-confident nation could give them respect. Wherever they were being persecuted, they should emigrate immediately: not to a new dispersion, but to a closed area in order to build a community there with the consent of the great powers. The place is of secondary importance: It could be in Palestine or in North or South America. This appeal appeared anonymously and initially met with little response. In 1884 Pinsker became a leader of the Eastern European "Friends of Zion" and thus took over their goals in Palestine. Due to the sometimes unexpected practical problems faced by the settlers, Pinsker's original goal of building a Jewish nation-state initially receded: The self-organization of the Friends of Zion threatened to fail and had to accept donations from wealthy patrons. Above all, the commitment of Edmond Rothschild (1845-1934) helped it to survive and changed it to a philanthropic aid organization without national claims.

Nathan Birnbaum

Nathan Birnbaum (1864–1937), originally from Vienna , is considered to be the creator of the term Zionism , which first appeared in writing in the magazine Selbst-Emancipation , which he published, on May 16, 1890, and which quickly became the common name for the Jewish national movement, not only among supporters and opponents of Zionism, but also among anti-Semites. Although a Zionist, Birnbaum, unlike Theodor Herzl , called for full, including ethnic and cultural equality for Jews in the diaspora ( The National Rebirth of the Jewish People in His Country , 1893) and later turned away from Zionism.

USA

Louis Brandeis was an American lawyer and first Jewish judge on the United States Supreme Court . He was appointed by US President Woodrow Wilson in 1916 and remained in office until 1939. Brandeis was a key spokesman for American Zionism and a supporter of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party in the United States.

Theodor Herzl

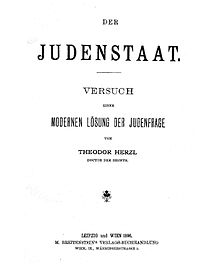

Faced with German racial anti-Semitism, as represented by Karl Eugen Dühring and Wilhelm Marr from around 1880 , Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) had turned into a Zionist. During the Dreyfus affair in France in 1895 he wrote the book Der Judenstaat - An attempt at a modern solution to the Jewish question . In it he carried out his idea of a sovereign state organization in order to give the haphazard and scattered emigration of European Jews a common goal and to secure settlement actions under international law. At first, Herzl did not necessarily think of a Jewish state in Palestine; East Africa and South America were also agreeable to him. He hardly justified his idea with religious motives, but with the failure of Jewish emancipation, especially in the supposedly “civilized” countries of Europe. Up until then he had seen France in particular as a haven of social and cultural progress. Now he judged that anti-Semitism would never go away and that all efforts by the Jews to assimilate would only reinforce it. The only way out could therefore be the gathering of the Jews in their own country.

Unlike the books of its predecessors, Herzl's book received a lot of attention and gave the impetus for the international merger of the existing national Jewish associations. On August 29, 1897, 200 delegates elected by their associations met in Basel for the first Zionist congress . There Herzl, together with the organizer David Farbstein, called for a Jewish state in Palestine that was legalized under international law for the first time. In response, the established World Zionist Organization ( World Zionist Organization WCO, abbreviated) with the program: "Zionism aims at the creation of a publicly legally secured homeland in Palestine for the Jewish people." This was the common goal of all Zionist movements. The word “Jewish state” was avoided in order not to define the shape of the desired community. In order to involve the friends of Zion, the declaration named as the first means of achieving the goal: "The appropriate promotion of the settlement of Palestine with Jewish farmers, craftsmen and tradesmen." Herzl thus achieved priority for diplomacy and was initially able to plan for new Jewish settlements without international law deny. He pointed out that illegal settlement construction by the ruler of Osmania and thus Palestine, Sultan Abdülhamid II , was only used as a bargaining chip for conditions. In the following years he tried to convince him and other leaders, including Wilhelm II , but without decisive success. Despite increasing criticism of his approach, he remained chairman of the action committee until his death in 1904.

Directions

In the course of time, Zionism differentiated itself into different political directions, the only common feature of which was the goal of a homeland for the Jews in the Land of Israel. The four major political camps - Religious Zionists (Misrachi), Socialists, Revisionists and General Zionists - cover the spectrum of the State of Israel with many splinter groups to this day.

Socialist Zionism

From 1900 a socialist Zionism developed mainly from Russia. The Marxist Poalei Tzion and its theoretician Ber Borochov achieved great importance and shaped the kibbutz and labor movement in Palestine. In Eastern Europe there were also the non-Marxist Zionist-Socialists around Nachman Syrkin , who did not commit to Palestine as a future settlement area, and the Sejmists around Chaim Shitlovskij , who wanted to achieve cultural and political autonomy in Russia as an intermediate step towards their own area. Even bourgeois, religious and nationalist Zionists formed their own organizations, each with their own ideas of how to achieve and shape the desired Jewish state.

Meanwhile, Zionism also met with determined resistance in the European labor movement. Ideologically, the basic idea of Zionism of an "eternal hostility to Jews" contradicted the socialist-materialist analysis of society. The Zionists were accused of wanting to solve the problem of anti-Semitism by ultimately fulfilling the anti-Semites' demand for the exclusion of Jews through emigration, instead of fighting for a fundamental reorganization of the situation that would ultimately also remove the breeding ground for anti-Semitism . The assessments of social democratic theorists ranged from the charge that Zionism was pure utopia to its classification as an arch-reactionary ideology. Jakob Stern concluded in a review of Herzl's Jewish State that Zionism wanted to avoid the fight against anti-Semitism.

Since the Stuttgart Congress of the International in 1907, where colonialism played a prominent role, the Socialist Monthly , the most important organ of the revisionists in the SPD, behaved differently . From then on they saw Zionism as a kind of “socialist colonial policy” and emphasized the achievements of the Zionists in the sense of a “cultural humanity”, such as the reclamation of land. Eduard Bernstein in particular looked thoughtfully at the relationship between Zionism, anti-Semitism and socialism. As one of the few Social Democrats, Bernstein did not see anti-Semitism as a problem that could be resolved by resolving economic contradictions; he warned of its occurrence in large parts of the bourgeoisie and saw this as more dangerous than "racket anti-Semitism". Bernstein viewed this expansion of anti-Semitic attitudes as conducive to Zionism and concluded from it that Zionism would also function as an emancipatory movement against mechanisms of oppression such as anti-Semitism.

Cultural Zionism

The pursuit of a fundamental renewal of Jewish culture, represented by Achad Ha'am in the Zionist movement around 1900 as an indispensable prerequisite for a Jewish national consciousness, was described as cultural Zionism . The “ Jewish question ” that Zionism was supposed to answer was, in the eyes of the cultural Zionists, first of all the question of the future of Judaism under the conditions of modernity.

Achad Ha'am distanced himself early on from Herzl's “Congress Zionism”, who viewed Zionism more pragmatically as a response to European anti-Semitism and the economic hardship of the Jews in Eastern Europe and not as a cultural renewal movement. Nevertheless, his ideas already played an important role at the founding congress of the WZO, especially in the debates on the “cultural question”. At its center was the revival of the Hebrew language as the future national language .

In contrast to Herzl, Achad Ha'am had a realistic assessment of the Arab reactions to Jewish immigration, which Herzl, in naive hope, assessed as welcoming. Ha'am, however, clearly underestimated the threat posed by anti-Semitism to European Jews, so that cultural Zionism lost its importance after the Holocaust and the founding of Israel. As an Eastern Jew, despite his rational attitude, he was more closely connected than Herzl to Jewish traditions and in particular to Hasidism , which is why he gave priority to a cultural-religious renaissance of Judaism, while Herzl and other Zionists placed the anti-Semitic danger in the foreground.

The Cultural Zionists organized themselves in 1901 within the framework of the WZO by founding the Democratic-Zionist Fraction .

Religious Zionism

Revisionist Zionism

The Revisionist Zionism is a civic, anti Socialist nationalist direction within Zionism. In 1925, Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky , who saw himself as the true successor to Theodor Herzl , whom he admired , founded the New Zionist Organization . The youth organization Betar and the paramilitary Irgun Zwai Leumi followed . The revisionist faction wanted to review and reassess Zionism, which was dominated by Chaim Weizmann's world of thought. Weizmann, then chairman of the World Zionist Organization , was, in Jabotinsky's view, too little committed to a state of its own.

Opponent in Judaism

The General Jewish Workers' Union (“Bund”), founded in Vilnius in 1897 , rejected the ideas of the friends of Zion and a Jewish state and instead demanded full equality for the Jewish workers of Eastern Europe and national-cultural autonomy for the Jews living there, i. H. recognition as a Jewish nationality . Some Orthodox Jews, on the other hand, saw the Zionists as apostate heretics who revolted against the divine Jewish exile and wanted to redeem themselves instead of waiting "humbly" for the arrival of the God-sent Messiah. Today, however, there are very many Orthodox Jews who are Zionists.

In Western Europe , much of Europe's Jews rejected Zionist aims and organizations until 1933. Liberal-bourgeois groups such as the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith continued to regard anti-Semitism as "curable" and the Jewish state as unnecessary or utopian. They feared that Zionist demands would only worsen the situation of European Jews and damage their integration efforts. The goal of a Jewish state was seen by them as an obstacle to the recognition of the Jewish minorities in the respective home states of Europe. They criticized early on that Zionism, like anti-Semitism, viewed Jews as “foreign bodies” in the European nation-states.

This criticism is taken up in the present by some Israeli historians such as Anita Shapira .

Uganda program

After the pogroms in Kishinev against Russian Jews on Easter 1903, Herzl proposed the British Uganda program as a provisional solution at the 6th Zionist Congress in Basel on August 26, 1903 . He stressed that it did not affect the ultimate goal of a homeland in Palestine. Nonetheless, his proposal provoked violent protests and almost divided the Zionist movement. An alliance of various groups came about which supported the proposals concerning Uganda in the period from 1903 to 1905. The Jewish Territorialist Organization (JTO) emerged from this.

Vladimir Jabotinsky , among others, took part in the 6th Zionist Congress . From then on, he fully identified with Herzl's goals and became a spokesman for Zionism. In 1923 he founded the revisionist wing and the Betar youth movement . At the 7th Zionist Congress in 1905, the Uganda program was finally dropped. Herzl's successor was David Wolffsohn (1905–1911), who advocated the practical colonization of Palestine regardless of the consent of the relevant states. The “perspective of Palestine”, with or without its own state, was also pursued by “cultural Zionism” under Ascher Ginsberg (Ahad Ha'am).

Second Aliyah

Triggered by the pogroms of Kishinev in today's Moldova in 1903, the persecution of the Jews after the Russo-Japanese War and after the failed Russian Revolution in 1905 , around 40,000 mostly young Russian Jews emigrated to Palestine between 1904 and 1914. The Jewish population there grew to around 85,000 by 1914. The immigrants were shaped by the Russian social movements and brought their thoughts to Palestine with them ( Ber Borochov , Aharon David Gordon ). The Hapoel Hazair was founded by the more social reform immigrants , while the social revolutionaries, to which the later Prime Minister David Ben Gurion belonged at the time, formed the Poalei Tzion , which, however, also took a reformist line over the years.

In 1901 the World Zionist Organization founded the Jewish National Fund (JNF) in order to specifically promote Jewish settlements in Palestine for the first time. In 1907 she founded the Palestine Office in Jaffa , which Arthur Ruppin headed. 1,909 were Jewish Colonial Trust ( "Jewish Colonial Trust") and the city of Tel Aviv founded which grew to 150,000 inhabitants by the 1938th The immigrants of the second Aliyah saw themselves as agricultural pioneers (Chaluzim). In 1909 they founded the first kibbutz, Degania, on the Sea of Galilee .

Balfour Declaration

The First World War set the Jewish settlers back enormously, as they got between the fronts of the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain. Under Ottoman sovereignty, they would only have been allowed to stay in Palestine if they had accepted Ottoman citizenship, which is why there were numerous naturalizations. This exacerbated the conflicts between the “practical” Zionists who wanted to create facts and the “political” Zionists who first wanted to gain the support of major European powers.

Above all, Chaim Weizmann , as a representative of the WZO, achieved through skilful negotiations the promise of the British government to put the already existing Jewish settlements under its protection and to allow further immigration. On November 2, 1917, British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour wrote the Balfour Declaration, named after him, to the committed British Zionist Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild : The government regards the “creation of a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people with benevolence "And will make the" greatest efforts to facilitate the achievement of this goal. " this was the first time that a European state recognized their goal of a Jewish state in Palestine. In doing so, "the civil and religious rights of the local non-Jewish population should be protected".

Agreement with Syria

In 1922 the League of Nations gave Great Britain the mandate that had actually been exercised since 1918 to implement the Balfour Declaration. Since this left open what the “national home” of the Jews should look like and how it should be reached, the WZO initially sought to clarify these questions amicably with the Arabs. They did not reject the Balfour Declaration and welcomed Jewish immigration, provided that Arab interests were taken into account.

On January 3, 1919, Weizmann concluded the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement with Faisal I , in which Syria recognized further Jewish settlement and a Jewish interest group in Palestine. The WCO renounced an autonomous government and in turn agreed to support the Arabs' striving for an independent Arab state.

Faisal made his approval of the agreement dependent on the British promise for an independent Greater Arabia. The British High Commissioner of Egypt , Henry McMahon , Faisal's father, King Hussein ibn Ali , had given this promise in writing in 1916. In return, the Arabs supported the British in their fight against the Ottomans.

Compensation with the victorious powers

On February 27, 1919, the representatives of the WZO, including Weizmann, explained their ideas to the Supreme Allied Council: the promotion of Jewish immigration and the settlement of up to 80,000 Jews annually, their officially recognized representation in Palestine, permission to set up a Hebrew education system and the preferential granting of concessions for undeveloped land to Jews. Against considerable resistance from within their own ranks, they again refrained from calling for an autonomous Jewish state government. This could only happen with a Jewish majority in Palestine. For this they achieved the approval of the European states.

Beginning of the Middle East conflict

Great Britain did not recognize the promises it had made to the Hashemites for an independent Greater Arabia during the World War . As a result, resistance against further Jewish settlement of Palestine arose among the Arabs living there and those in the wider region. They saw this now as an expression of imperialist British policy, which was directed against their goal of a Greater Arab nation. A resolution of the Syrian Congress of July 2, 1919 turned against a Jewish community "in the southern part of Syria, called Palestine". Arab delegates protested against a Jewish state in front of a commission sent by US President Woodrow Wilson .

In April 1920 the League of Nations gave Great Britain the mandate to administer Palestine and thus to fulfill the Balfour Declaration. Prime Minister David Lloyd George appointed Sir Herbert Samuel, a British Jew, as High Commissioner in Palestine. This increased the bitterness of many Arabs towards the British and the Jewish settlers of Palestine, whom they now saw as allied against themselves.

That same month, Arabs first attacked Jews in Jerusalem, looted Jewish shops, and killed and injured local Jewish residents. The British military did not intervene. In May 1921, 43 Jews were murdered in Jaffa in new Arab riots; the Jewish settlement Petach Tikwa , which was also attacked , was able to defend itself successfully.

British mandate politics

The British High Commissioner then had further Jewish immigration stopped in order to first clarify the causes of the unrest. The commission of inquiry found that Arab police had participated in attacks on Jews instead of protecting them. Previously, Zionist authorities had propagated "Hebrew work". Jews who had bought large Arab estates gave preference to new Jewish settlers and dismissed the local Arab population. The British administration now allowed Jews, but not Arabs, to carry weapons for self-defense. Winston Churchill , then British Colonial Minister, allowed further Jewish immigration without clarifying the shape and boundaries of the future Jewish state.

In 1920 the Zionist union Histadrut was founded with the aim of filling industries that private investors have shunned, and so over time it has become the largest employer in Palestine.

In the summer of 1921, an interim report by the High Commissioner stated that the implementation of the Balfour Declaration was dependent on the “rights of the local population”. In doing so, he practically granted the majority of the Arab population the right to reject the Jewish state. He also made the Arab nationalist Mohammed Amin al-Husseini , a later collaborator of the National Socialists , the Mufti of Jerusalem.

In 1923 the British mandate was split up. The smaller part was called "Palestine" from now on, while the larger part became Transjordan (first as a sultanate, then as the Kingdom of Jordan ). The Pan-Arabists saw their chances of having their own Greater Palestine further weakened.

From around 1925 the Zionist Hachschara ("preparation" for emigration) found itself in Germany. Zionism, however, remained an affair of a Jewish minority; of around 580,000 German Jews, only 7,500 belonged to a Zionist organization in 1932. The majority wanted to stay in Europe and work there to improve the social and legal situation for all citizens.

time of the nationalsocialism

Germany

With the coming to power of the Nazi party on 30 January 1933, the general government persecution of Jews began in Germany. The first measures taken by the Nazi regime were the “ Jewish boycott ” of April 1, as well as the “ Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ” and the “ Law on Admission to the Legal Profession ” of April 7, 1933, which gave many German Jews property, occupation and social status lost.

On August 25, 1933, the Ha'avara Agreement (“Transfer”) between the Jewish Agency , the Zionist Association for Germany and the German Reich Ministry of Economics came into force in order to facilitate the emigration of German Jews to Palestine and at the same time German exports to promote. By the end of the year around 37,000 of the 525,000 Jews living in Germany had emigrated, most of them (approx. 73%) first moved to neighboring European countries, 19% to Palestine, and 8% opted for a country overseas. In the years that followed, up to 1937, the annual number of emigrants remained far below the figure in the year of the seizure of power (23,000 in 1934, 21,000 in 1935, 25,000 in 1936 and 23,000 in 1937). The Zionist associations grew to 43,000 members by 1934.

On September 13, 1933, all major German-Jewish associations, including the Zionist, united to represent the German Jews under Leo Baeck . This wanted to strengthen their cohesion and control the flight-like emigration. For this purpose she procured z. B. Immigration Papers and Managed Abandoned Properties.

Adolf Hitler himself thought Zionism was a lie and a deceit of the Jews. In Mein Kampf he wrote that the Jews were “not thinking of building a Jewish state in Palestine in order to inhabit it, but only want an organizational center of their international world wonder, equipped with their own sovereign rights and beyond the reach of other states; a refuge for transferred rags and a college for becoming crooks ”.

After the Nuremberg Laws of September 15, 1935 had deprived German Jews of their citizenship rights, the number of people willing to leave increased, although associations such as the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith continued to encourage people to stay.

250,000 German Jews emigrated to other countries between 1933 and the outbreak of war in 1939. To do this, their Reich Representation had to raise more and more funds until their members had to surrender around 10 percent of their income to them. The Zionist Association was allowed to use this income to build training farms (hachshara), on which those wishing to leave the country learned agriculture in order to facilitate their new beginning in Palestine. From 1933 to 1941 around 55,000 Jews from the German Reich - around a quarter of all Jewish immigrants - reached Palestine. 15,000 to 20,000 of them violated British entry regulations.

In 1937, the German authorities increasingly blocked the emigration of German Jews despite the Ha'avara Agreement. Adolf Eichmann was sent to Palestine to contact the Israeli underground organization Hagana . However, Eichmann was expelled from the country. In Egypt he met al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who had allied himself with the Nazi regime since 1933 and later participated in the Holocaust.

After the annexation of Austria on March 12, 1938, the situation of Reich German Jews worsened again: the November pogroms of 1938 from November 7th to 14th destroyed the lives and property of hundreds as well as the synagogues of Jewish culture in Germany and Austria. The Évian conference of July 1938, at which representatives of 32 nations discussed the possibility of emigration of Jews from Germany and Austria on the initiative of the American President Franklin D. Roosevelt , was practically inconclusive.

In 1939, by order of Hermann Göring , the Gestapo set up a “ Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration ”. The attack on Poland on September 1, 1939 brought three million Polish Jews under German control. 7,000 of them had been murdered by the end of the year. The German invasion of the neutral Netherlands (“ Fall Gelb ”) on May 10, 1940 forced around 20,000 German-Jewish emigrants to flee again, 25,000 from Belgium and 35,000 from France.

Palestine

The National Socialist persecution of Jews accelerated the influx of European Jews to Palestine from 1935 onwards. Since the refugees were allowed to take up to £ 1,000 with them at the time, Palestine experienced an economic boom, which in turn increased the influx of Arabs there.

After the Arab uprising against the Palestinian Jews began in 1936 , the British Peel Commission rejected the implementation of the Balfour Declaration and presented a partition plan in July 1937. After that, a large part of Palestine was to be assigned to the Arabs, the smaller part with the most Jewish settlements to the Jews, Jerusalem and a coastal strip should remain British mandate territory. Weizmann, who has headed the WZO since 1935, spoke out at the 20th Zionist Congress in favor of adopting this plan in order to save as many persecuted Jews as possible. However, the representatives of the Arabs rejected the plan and demanded that the whole of Palestine be made an Arab state.

This reignited the Arab uprising. The defensive struggles of the British forced the Mufti al-Husseini to flee Palestine. The Haganah built with the help of the pro-Zionist British Orde Wingate , a powerful but purely defensive oriented unit to protect the Jewish settlements on the Plugot Laila . Their motto was Hawlaga (self-control).

Successor commissions of the British narrowed down the area allocated to the Jews more and more and finally dropped Peel's plan altogether. In the 1939 White Paper , the British government unilaterally stipulated that the Balfour Declaration had already been implemented; In five years, a maximum of 75,000 Jews should be allowed to immigrate to Palestine. At a conference in London in August 1939, Neville Chamberlain tried unsuccessfully to persuade the representatives of the WCO to renounce a Jewish state in Palestine.

The WCO, the League of Nations and Winston Churchill as opposition leader in the British House of Commons rejected this White Paper as a breach of treaty incompatible with the British mandate. But as Prime Minister Churchill retained Chamberlain's decision beyond the end of the war.

In 1937 the Mossad le Alija Bet was founded in Paris to coordinate the illegal emigration ( Alija Bet ) of European Jews, mostly by boat across the Danube to Romania and further across the Bosporus to Palestine. Many of the completely overloaded boats sank en route or were seized by the British before they reached the coast of Palestine, their inmates were interned in assembly camps and later banished to the island of Mauritius . The WZO did not even get British permission to legally accept Jewish children.

During this time, Jewish underground organizations began to carry out attacks against the British: from 1937 the Irgun (Etzel) under the leadership of Jabotinsky, to which, after the group split up in 1940, Lechi was added under the leadership of Avraham Stern . In 1941 the Palmach was founded in Palestine as a Jewish “ elite unit ” of the Hagana, while Al-Husseini met Hitler in Berlin and Erwin Rommel's Africa Corps was already in Libya . His military advance could be stopped in the second battle of el-Alamein before it reached Jewish settlements.

Shoah

With the attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Holocaust (also known as the Shoah ) began with organized mass murders, initially of Soviet Jews and the deportations of German and Eastern European Jews to ghettos and camps in Eastern Europe. The most important decisions to expand the extermination of the Jews were made between July and October 1941: the construction of extermination camps began , and German Jews were ordered to wear the Star of David throughout the Reich .

On October 23, 1941, Heinrich Himmler issued a general emigration ban for Jews in areas occupied by Germany, and in November also issued them expropriation and the loss of their citizenship when they were deported. Since then, Jews have no longer been able to legally emigrate. On January 20, 1942, at the Wannsee Conference, the “ Final Solution to the Jewish Question ”, which had begun in June 1941, was coordinated and organized for all of Europe by leading representatives of the Nazi authorities. In April 1942, Himmler ordered the complete deportation of all European Jews to the now completed Eastern European extermination camps. From July 1942 onwards, most of the newcomers who were deported were gassed immediately after their arrival in the camps .

The ongoing Holocaust became known outside of Germany in autumn 1941, but this did not lead to any targeted countermeasures. A Jewish brigade was formed in the British army (see Hannah Szenes ). At the Biltmore Conference in New York City in 1942, the US delegates of the WCO and the group around Ben Gurion called for the first time "to open the gates of Palestine" and to establish a Jewish Commonwealth there with a democratic constitution based on the European model. This was refused by the British government and prohibited the publication of the Biltmore program in Great Britain and Palestine. The revisionist Bergson group succeeded in the USA with high-profile and skilful campaigns against the resistance of the Zionist establishment to put the American government under pressure to found the War Refugee Board in 1944, an American state organization to rescue the persecuted Jews.

Since the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in January 1943, the number of Jewish refugees has increased again. Increasingly, the British government searched Jewish settlements in Palestine, arrested illegal immigrants and banned Zionist newspapers. In 1944 the Irgun and Lechi organizations expanded their attacks against the British. The Hagana arrested Irgun members and turned some of them over to the British. At the same time around 100,000 of the up to then 500,000 Palestinian Jews fought with the Allies in Europe against the Germans.

History since 1945

post war period

In the last months of the war, the Allies liberated some of the Nazi extermination camps, including the Auschwitz concentration camp on January 27, 1945 . But no European country except France and Sweden agreed to take in the survivors after the end of the war on May 8, 1945.

During the British election campaign, the Conservative Party promised to split up Palestine to resolve the dispute with the Arabs. The Labor Party put forward a Palestine plan that envisaged converting the entire region into a Jewish state and using generous funds to encourage Arab residents to emigrate. After its election victory, however, the Labor government only allowed 1,500 Jews to immigrate each month.

The WZO demanded that at least the surviving concentration camp inmates be allowed to immigrate; US President Harry S. Truman called on the British to immediately admit 100,000 Jewish immigrants. An Anglo-American commission formed under his pressure toured Palestine and the European assembly camps for displaced persons . She then took over Truman's request, but the British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin stuck to the low monthly quota.

Thereupon the Zionist Congress in Geneva in 1946 adopted the Biltmore program as the basis for its goals. This remained controversial in the WCO; radical groups called for open resistance to the British mandate government, others for a binational state with equal rights for Jews and Arabs. Because only in agreement with the neighboring Arab states is a Jewish state permanently viable, whereby the Arab parts of Palestine must be open to Jewish settlement. Arabs should be able to team up with Jews against large landowners. This was represented by secular left-wing Zionists, who later founded the Mapam party, and German-Jewish Zionists such as Martin Buber , Hugo Bergmann , Ernst Simon and the rabbi and later university director Judah Leon Magnes . The American Zionists around Ben Gurion and the socialist Mapai party rejected a binational state in order to be able to immediately offer a place of refuge to displaced persons with a limited Jewish state. The Arabs in and around Palestine also rejected a binational state.

Since February 1946, around 175,000 Polish Jews displaced by the Nazi regime have been deported to their home country from the Soviet Union, but rejected there by the local Poles, who had often taken over their property. 95,000 of them then fled to Palestine via Western Europe , especially since the Kielce pogrom on July 4, 1946. The Hagana, the Jewish brigade of the British Army and the Mossad jointly organized this illegal immigration of Shoah survivors (" Bericha ").

The British had 50,000 of them returned to DP camps in the American zone of occupation in Germany from 1945 to 1946, and interned others in Cyprus . During a raid on June 29, 1946, they arrested all members of the Jewish Agency and other leading Zionists who could be found in Palestine and held them for weeks in a camp in Lod .

Establishment of the State of Israel

Then in 1946 Irgun attacks increased, particularly on British railways and the Arab High Committee . Palmach units blew up ten bridges (May 16-17). In response to the terrorist attacks, the elected officials arrested all Zionist leaders on June 29th, whereupon the Irgun blew up a wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem , where the British headquarters were located , on July 22nd . The unrest then escalated through 1947 - until the United Nations approved the UN partition plan for Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish and an Arab state on November 29 .

With the UN resolution and the beginning of the British withdrawal, the Arab unrest and attacks increased again. The day after the UN partition plan was announced (November 30), the Zionist-Arab civil war began . Arab forces, consisting of village militias supported by the Arab Liberation Army and reinforced by European mercenaries such as deserters from the British army and veterans of the Croatian Waffen SS , were Jewish militias, including numerous veterans of World War II and the Palmach troops, opposite. In early December, the Arab High Committee called a three-day general strike. The Arab League could not invade until the British withdrew completely, but planned to invade the day after the withdrawal was complete.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion read the Israeli declaration of independence in Tel Aviv . The USA recognized the new state on the same day, the Soviet Union on May 17th. The British mandate ended on May 15, when the armies of Transjordan , Iraq , Lebanon , Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. Israel defeated them in the Palestinian War with the help of arms deliveries from Western and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union and the USA. Now the legal mass immigration of Jews from Europe into Israel began. As the first legislative act, the Knesset passed the Return Act in 1950 , which guarantees all persons defined as Jewish under the law the right to settle in Israel and immediately obtain Israeli citizenship.

New program

Since the founding of the state of Israel, WCO congresses have only been held in Jerusalem. The 23rd Congress in 1951 replaced the Basel Program with the Jerusalem Program , which defined the goals of the Zionist movement:

- the strengthening of the State of Israel ,

- the gathering of the dispersed in Eretz Israel ,

- maintaining the unity of the Jewish people.

This moved Israel's relationship to the Jewish diaspora and their mutual obligations to preserve Judaism into the center of considerations.

Neo-Zionism

The Zionists' dream of finding a safe home through the establishment of their own Jewish state did not come true. In an environment hostile to them, the Israelis had to fight hard for their existence and there was no question of normality in life. In June 1967 Israel defeated the threatening Arab alliance in the Six Day War and was able to conquer other areas of the biblical Eretz Israel at the same time as the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula including the Gaza Strip , the Jordanian West Bank and the Syrian Golan Heights . This triumph sparked a national and religious euphoria and revived the old Zionist spirit. In the course of this development, the discussion about the borders of Israel broke out again. At the same time, the Avoda, as the leading Zionist party, was challenged because of the reluctance to settle in the occupied territories. The settlement of the occupied territories is of central importance for neo-Zionism.

Opposing positions

Anti-zionism

A particularly widespread counter-position is anti-Zionism, which rejects and fights Zionism and the State of Israel . Many anti-Zionists emphasize the difference between their beliefs and anti-Semitism , while critics emphasize the similarities between the two ideologies.

Anti-Zionists generally understand Zionism today as a political current that supports the establishment and expansion of an Israeli territory at the expense of the Arab population. In the Arab and Islamic world, as in the rest of the world, there are organizations and people who criticize Zionism as such.

The majority of the Palestinians and the Arab states in particular accuse the Zionist movement of driving the Palestinians out of their settlement areas and question the very right of the State of Israel to exist . They describe Zionism as an ongoing form of colonialism . This dispute forms the ideological background of the Middle East conflict .

In 1975 UN General Assembly Resolution 3379 , in which Zionism was identified as a form of racism , caused a sensation . The resolution was withdrawn on December 16, 1991 by resolution 4686 by the UN General Assembly by 111 votes to 25 with 13 abstentions. According to a statement by the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Israel made its participation in the Madrid Peace Conference in 1991 dependent on the withdrawal of the resolution. In 1998, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan described resolution 3379 as a low point in the history of the United Nations . The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), set up by the Council of Europe , published a working paper on the forms of anti-Semitism today, in which it emphasized that the claim that the State of Israel is "a racist project" manifests itself as anti-Semitism .

To this day, Zionism is a projection screen for conspiracy theories such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion . Various Islamist associations such as Hamas still refer to these protocols today .

Positions of Hillel Kook

In 1947 Hillel Kook (alias Peter Bergson) published his post-Zionist idea by arguing for a secular state of the "Hebrews" and against a "Jewish Vatican", which would include the entire Jewish diaspora and be religiously shaped. With Shmuel Merlin and Eri Jabotinsky he was a pioneer and member of the oppositional faction "La Merchav" within the Cherut, founded in 1950 . While the WCO sees this connection as essential and regards its strengthening and the gathering of Jews in and around Israel as not yet finished.

Postzionism

The term post-Zionism, first used in 1968 by the left-wing journalist Uri Avinery , calls for the state of Israel to detach itself from Zionist guidelines in order to justify its statehood independently of the influences of the diaspora. Avinery was thus close to Canaanism . Amos Elon (1971) and Menachem Brinker (1986) understood post-Zionism to be a view according to which the gathering of exiles is now complete. The meaning of the term changed in the 1990s, and since then it has more generally stood for a questioning of Zionist narratives and a further departure from the diaspora. Derek J. Penslar , Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto , defends post-Zionism against the frequent allegation that it is left-leaning and undermines the foundations of Zionist ideology, rather that post-Zionism is, as exemplified by the works of the writer Gafi Amir ( for example in the story: By the Time You're Twenty One You'll Reach the Moon ), often apolitical, pro-capitalist and glorify the autonomy of the individual. In addition to a vast rejection of the individual from the Jewish heritage, Jewish Bookshelf (dt. Jewish Bookshelf ), but there were still lines connecting the post-Zionism to Judaism and Haskalah , even with right-wing post-Zionists. Post-Zionist positions of the right are taken by the Jerusalem Shalem Center or the settlers' magazine Nekudah . Post-Zionism among secular Jews is discussed in the journal Teoryah u-Vikoret , founded by Adi Ophir . Their positions reflect postmodern thinking . The historian Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin criticizes this Western multiculturalism as “hypocrisy” , which turns a blind eye to the surrounding Arab reality and Islamic culture, as well as to Jewish tradition, from which the Mizrahim suffered.

Anti-Semitic code words related to Zionism

The term Zionist is used by anti-Semites as a code word for Jews in order not to openly name their hostility to Jews. This was evident in the early stages of the Cold War , when individual states of the Eastern Bloc launched campaigns and show trials against Jews.

The buzzword Zionist Occupied Government (ZOG) came up in the late 1970s. It takes up the old conspiracy theory that "the Jews" would conspire to establish a clandestine world government .

In 2015, the Essen District Court classified the term Zionist in the slogan "Death and hate the Zionists" accordingly and convicted a defendant of sedition . The term Zionazi has been used since the 1980s . Equating National Socialism and Zionism implies that peaceful coexistence is not possible with Zionism either, because it too relies on violence and racism and seeks control and hegemony. Last but not least, this is intended to disqualify the peace process in the Middle East.

The Iranian regime in particular regularly provides its anti-Zionist rhetoric with unequivocal anti-Semitic connotations and images, so that the "repeatedly claimed distinction between Zionists and Jews" is reduced to absurdity.

In Wilhelm Landig's right-wing esoteric novel trilogy Götzen gegen Thule (1971), Wolfszeit um Thule (1980) and Rebellen für Thule (1991), SS people fight as heroes of the novel "auxiliary troops of Mount Zion" - a code word for Jews.

See also

literature

- Historical documents

- Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): Zionism. Texts about its development. 2nd, revised edition, Fourier, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 978-3-921695-85-2 ( online excerpt ).

- Jehuda Reinharz : Documents on the history of German Zionism. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1981, ISBN 978-3-16-743272-3 .

- Francis R. Nicosia (ed.): Documents on the history of German Zionism 1933–1941. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-16-155021-8 .

- story

- Samuel Salzborn (Ed.): Zionism. Theories of the Jewish State. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2015, ISBN 978-3-8487-1699-9 .

- Tamar Amar-Dahl : Zionist Israel. Jewish Nationalism and the History of the Middle East Conflict. Schöningh, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-506-77591-7 .

- Kerstin Armborst-Weihs: The Formation of the Jewish National Movement in Transnational Exchange: Zionism in Europe up to the First World War , in: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2010, accessed on March 25, 2021 ( pdf ).

- Simha Flapan : The Birth of Israel. Myth and Reality. Melzer Semit Edition, Neu-Isenburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-937389-55-4 .

- Michael Brenner : History of Zionism. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3-406-47984-7 .

- Michael Krupp : The History of Zionism. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2001, ISBN 978-3-579-01212-4 .

- Amnon Rubinstein: History of Zionism. From Theodor Herzl to Ehud Barak. dtv, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-423-24267-7 .

- Shlomo Avineri : Profiles of Zionism. Gütersloh 1998, ISBN 3-579-02092-7 .

- Conor Cruise O'Brien : State of Siege. The history of the State of Israel and Zionism. dtv, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-423-11424-X .

- David Vital: Zionism: The Formative Years. Clarendon Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-827443-8 ; New Edition 1989.

- David Vital: Zionism. The Crucial Phase. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, ISBN 978-0-19-821932-3 .

- David Vital: The Origins of Zionism. Clarendon Press, Oxford, New York 1980, ISBN 978-0-19-827194-9 .

- Alex Bein : The Jewish question. Biography of a world problem. (2 volumes) DVA, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-421-01963-0 .

- Walter Laqueur : The Way to the State of Israel. History of zionism. Europe, Vienna 1972, ISBN 978-3-203-50560-2 .

- Germany

- John VH Dippel: The Great Illusion. Why German Jews didn't want to leave their homeland. Beltz, Weinheim / Berlin 1997, ISBN 978-3-88679-285-6 .

- Yehuda Eloni: Zionism in Germany. From the beginning until 1914. Bleicher, Gerlingen 1987, ISBN 3-88350-455-6 .

- Sabrina Schütz: The construction of a hybrid “Jewish nation”. German Zionism in the mirror of the Jüdischen Rundschau 1902–1914 (= forms of memory, vol. 68). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-8471-0930-3 . Zugl .: Regensburg, Univ., Diss.

- Lisa Sophie Gebhard, David Hamann: German-speaking Zionisms. Advocates, critics and opponents, organizations and media (1890-1938) , Peter Lang, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-631-79746-4 .

- discussion

- Susie Linfield: The Lions' Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky. Yale University Press, New Haven 2019, ISBN 978-0-300-22298-2 .

- Micha Brumlik : Critique of Zionism. European Publishing House, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-434-50609-6 .

- Ekkehard W. Stegemann (Ed.): 100 years of Zionism. About the realization of a vision. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-015577-6 .

- Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): Zionism. Thirty-four essays. Nymphenburger, Munich 1973, ISBN 978-3-485-03216-2 .

- Dmitry Shumsky: Beyond the Nation-State. The Zionist Political Imagination from Pinsker to Ben-Gurion. Yale University Press, New Haven 2018, ISBN 978-0-300-23013-0 .

Web links

- Michael Brenner: What is Zionism? From the idea to the state.

- Martin Kloke : The development of Zionism up to the founding of the state of Israel. In: European History Online . Published by the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2010

- Basic texts on the history of Zionism

- 100 years of Zionism.

- Axel Meier (Shoa.de): German Zionism during the Third Reich.

- Shoah.de: Zionism (short introduction and further links)

- Association of progressive Zionists in Germany

- Representation of the Zionists within conservative Judaism ( Memento from May 31, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- Newspaper article about Zionism in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

-

↑ Eyal Chowers: The End of Building: Zionism and the Politics of the Concrete . In: The Review of Politics . 64, No. 4, 2002, ISSN 0034-6705 , pp. 599-626, pp. 599.

Eliezer Don-Yehiya: Zionism in Retrospective . In: Modern Judaism . 18, No. 3, 1998, ISSN 0276-1114 , pp. 267-276, pp. 271.

Anita Shapira: Anti-Semitism and Zionism . In: Modern Judaism . 15, No. 3, 1995, ISSN 0276-1114 , pp. 215-232; S. 218.

Lilly Weissbrod: From Labor Zionism to New Zionism: Ideological Change in Israel . In: Theory and Society . 10, No. 6, 1981, ISSN 0304-2421 , pp. 777-803, p. 782.

Goldberg, David J .: To the promised land: A history of Zionist thought from its origins to the modern state of Israel . Penguin, London, UK 1996, ISBN 0-14-012512-4 , pp. 3 . - ↑ Michael Brenner: History of Zionism , Munich 2002, p. 8; Wording online

- ↑ Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 12.

- ^ Maryanne A. Rhett: The Global History of the Balfour Declaration. Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-1-138-11941-3 , p. 198

- ↑ Barbara Schäfer: Zionism. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia. Volume 36.Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, p. 699 f.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 15.

- ↑ Barbara Schäfer: Zionism. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia. Volume 36.Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, p. 700.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 2, p. 269 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Treue: Jewish cosmopolitanism or national Judaism? The Alliance Israélite Universelle and Zionism in Germany. In: Kalonymos 13/3, 2010, pp. 9-12.

- ↑ a b Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 21.

- ↑ Tobias Grill: Anti-Zionist Jewish Movements. In: Institute for European History (Ed.): European History Online (EGO) , November 16, 2011

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 1, p. 276.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 2, p. 272.

- ↑ Monika Grübel: Judaism. DuMont, Cologne 1996, p. 186.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 1, p. 277.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 1, p. 278 f.

- ↑ Erika Timm (ed.): A life for science / A Lifetime of Achievement. Scientific articles from six decades by Salomo / Solomon A. Birnbaum. Solomon Birnbaum's life and work. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025194-4 , p. XII f.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 1, p. 294.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 2, p. 291.

- ↑ Michael Brenner : The development of political Zionism according to Herzl. In: Federal Agency for Civic Education . March 28, 2008, accessed November 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Cf. Friends of the Association for Research on the History of the Workers' Movement (ed.): Judaism and Revolution - The World Association Poale Zion between Zionism and Communism " , special issue of Work - Movement - History , II / 2017, Berlin.

- ↑ Andreas Morgenstern: The Socialist Monthly Bulletins in the Empire - Spoke of a Worker Zionism? In: Year Book for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Volume III / 2012. Online: [1]

- ↑ Mario Keßler: Anti-Semitism, Zionism and Socialism. Mainz 1993, p. 89 ff.

- ^ Paul Mendes-Flohr : Cultural Zionism . In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 3: He-Lu. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02503-6 , pp. 454–458.

- ↑ Michael Brenner : The Development of Political Zionism according to Herzl , Federal Agency for Political Education, March 28, 2008

- ↑ Ann-Kathrin Biewener: Secularization in the Holy Land? University of Potsdam, accessed on November 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Anita Shapira: Anti-Semitism and Zionism . In: Modern Judaism . 15, No. 3, 1995, ISSN 0276-1114 , pp. 215-232, p. 218.

- ↑ Julia Bernstein : Isral-related anti-Semitism. Recognize - act - prevent. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim 2021, p. 29

- ↑ Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 93 f.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: Die Geschichte des Zionismus , p. 95.

- ↑ Walter Laqueur, The Way to the State of Israel. History of zionism. 1st edition, Europa Verlag, Vienna 1972, p. 528.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: Die Geschichte des Zionismus , p. 98.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 99.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: The History of Zionism , p. 100.

- ↑ Peter Bergson , Holocaust Encyclopedia, USHMM , accessed November 5, 2021.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: Die Geschichte des Zionismus , p. 101.

- ↑ Michael Krupp: Die Geschichte des Zionismus , p. 105.

- ↑ Alex Bein: Die Judenfrage , Volume 1, p. 404.

- ↑ [2] In: bornpower.de. , accessed April 9, 2018.

- ^ EUMC : Working definition of Antisemitism. ( Memento of January 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) 2005 (PDF)

- ^ The Avalon Project: Hamas Covenant 1988. Retrieved June 30, 2018 (Article 32).

- ↑ Roman Vater: Pathways of Early Post-Zionism. In: Jewish Radicalisms: Historical Perspectives on a Phenomenon of Global Modernity. Frank Jacob and Sebastian Kunze (eds.), De Gruyter 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-054352-0 , pp. 27 and 45 f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Derek Jonathan Penslar: Israel in History - The Jewish State in Comparative Perspective . Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), London and New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-40036-7 , pp. 84 ff .

- ↑ Brian Klug : Anti-Semitism: Is the Monster Returning? Sheets for German and International Politics No. 4/2004, p. 394 ff .; Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution : Islamism from the perspective of the protection of the constitution , Cologne 2008, p. 7.

- ^ András Kovács (Ed.): Communism's Jewish Question. Jewish Issues in Communist Archives . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2017, ISBN 978-3-11-041152-2 , p. 6 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Jeff Insko: ZOG. In : Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia. ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, p. 758

- ↑ Stefan Laurin: Whoever wishes "Zionists" to die is inciters of the people , Die Welt, January 30, 2015; R. Amy Elman and Marc Grimm: On the current status of the European Union's measures against anti-Semitism . In: Marc Grimm and Bodo Kahmann (eds.): Anti-Semitism in the 21st century. Virulence of an old enmity in times of Islamism and terror . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-053471-9 , pp. 349–366, here p. 361 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Meir Litvak, Esther Webman: From Empathy to Denial. Arab Responses to the Holocaust. Hurst & Company, London 2009, ISBN 978-1849041553 , p. 239.

- ↑ Example Al-Quds-Tag - Islamist networks and ideologies among migrants in Germany and possibilities of civil society intervention ( Memento from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 625 kB) Report by Udo Wolter for the integration commissioner of the federal government, Berlin in November 2004.

- ↑ Dana Schlegelmilch, Jan Raabe: The Wewelsburg and the "Black Sun". In: Martin Langebach , Michael Sturm (ed.): Places of memory of the extreme right . Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-00131-5 , pp. 79-100, here p. 89.