Landsberger Bund (Styria)

The Landsberger Bund was a conspiracy of nobles in Styria in 1292. It was directed against Duke Albrecht I of Habsburg and had supporters in Bavaria , Salzburg and Carinthia . The conspiracy is named after the original name of Deutschlandsberg Castle in western Styria .

The uprising , based on the Landsberger Bund , was unsuccessful from a military point of view; it collapsed after about two months. However, the demands of those involved from Styria were largely fulfilled voluntarily by the victorious Albrecht. The expectations of their supporters were not fulfilled. The conflicting interests of Salzburg and the Habsburgs persisted and led to further conflicts.

This union has nothing to do with the alliance of some imperial estates in southern Germany 1556 to 1599, which is also known as the " Landsberger Bund ".

prehistory

Interregnum after the end of the Babenberg rule, Ottokar Přemysl

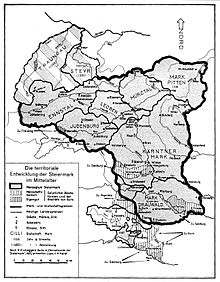

With Friedrich II. The last Babenberger to rule in Austria died in 1246 . The Babenbergers had also been dukes of Styria on the basis of the Georgenberger Handfeste since 1192 and had laid down important legal bases of the Duchy of Styria in this contract.

After the Babenbergs, King Ottokar of Bohemia initially prevailed in the southeastern areas of the Holy Roman Empire during the interregnum . He had become ruler of Austria in 1251. Through the Peace of Vienna he became Duke of Styria in 1261, and also Duke of Carinthia through the Podiebrad Treaty of 1269 . This was the first time that these inner Austrian states were united in one hand. Ottokar died in 1278 in the battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen against the troops of Rudolf von Habsburg , who had been elected Roman-German king in 1273 .

Beginning of the Habsburg rule

Rudolf von Habsburg initially ruled Austria and Styria himself and in 1282 appointed his sons Albrecht and Rudolf as rulers. From 1283 Albrecht was sole ruler. In 1286, Albrecht's father-in-law Meinhard von Görz-Tirol was enfeoffed with Carinthia . Austria, Styria and Carinthia thus remained under the influence of the Habsburgs and their families.

Albrecht soon became unpopular. The reason for this was the preference for supporters from his Swabian homeland (which at that time also included large parts of German-speaking Switzerland with the headquarters of the Habsburgs ) and his efforts to strengthen the Habsburgs' domestic power . In Styria, Albrecht was accused of not having carried out the hereditary homage and of supporting the behavior of his deputy (governor, provincial administrator ) Abbot Heinrich von Admont . This abbot had suffered displeasure because he had been commissioned to restore princely possessions to the sovereign after they had fallen into different hands without justification in the past turmoil. This approach was not new; it continued Rudolf's policy of revision. However, Albrecht had issued a letter of protection for this, which also covered arrests, the collection of taxes and the confiscation of castles. On this basis, the abbot had repeatedly acted with force , for example against Pernegg Castle . Abbot Heinrich had been hated as "the worst kind of people slayer" and was described as "the devil's chaplain and window hole".

The support that the Styrian nobles had promised the Habsburgs in the Reiner Oath against King Ottokar "unanimously and under all circumstances with body and good" had already decreased significantly after a few years. Some participants in the Reiner Oath 1276 were allies in the Landsberger Bund 16 years later.

During Albrecht's reign, the memory of King Ottokar in Austria and Styria was positively remembered by parts of the nobility, although a number of Austrian and Styrian nobles fought against Ottokar alongside Rudolf von Habsburg. The reign of Ottokar was held up to Albrecht as a counterexample.

Tensions with Salzburg

Albrecht tried to get hold of the Archdiocese of Salzburg in Styria under his control and thus came into conflict with Salzburg. The Salzburg exclaves in Upper Styria (in the Ennstal ), in West Styria (around the Sulmtal and Laßnitztal ) and in Lower Styria (near Pettau , Gurkfeld and Rann ) formed a "state within the state" in Styria. It was also about the profitable trade in salt from the salt pans of the Salzkammergut . In 1290, his father Rudolf von Habsburg had granted Albrecht the bailiff, which was disputed with Salzburg, over property of the Admont Abbey (founded from Salzburg) inside and outside Austria and Styria. This had brought Albrecht a position of power in Salzburg's sphere of influence. In this context, Rudolf had declared that the Archbishopric of Salzburg had no more rights to the bailiwick of the Admont Monastery (and thus its goods) than those that Salzburg had (already) given the Austrian dukes as a fief.

Even before the Landsberg Bund, there had been fighting in the Ennstal (the " salt war ") and the destruction of Neuhaus Castle (Trautenfels) in the upper Ennstal in 1289/1290 due to unresolved sovereignty . This dispute was decided by Rudolf on June 19, 1290 in Erfurt essentially in favor of his son Albrecht. Disputes over the occupation of the Salzburg bishopric after the death of Bishop Rudolf von Hoheneck followed. The future Bishop Konrad from Salzburg had become the personal opponent of Abbot Heinrich von Admont, who had also applied for the Salzburg bishopric.

Bavaria and Hungary

For Bayern , there were also reasons for the influence of the Hapsburg (and attributed to them Meinhardiner to restrict in Carinthia): There were claims Duke Otto from Bavaria to the rule in Hungary . The possession of Styria would have made a route to Hungary possible for the Bavarian dukes that would have been entirely within their own sphere of influence. On this route across the Salzach , Enns, Kammer and Murtal valleys , no expenses for tolls and customs duties would have been incurred. Transports and travelers between Bavaria and Hungary would not have had to cross the foothills of the Alps , in which the opposing Habsburgs ruled. Even high Alpine passes (impassable for months in winter) would not have been usable because the Schober Pass would have been the lowest crossing over the Alps. During this time, Salzburg was only in the process of breaking away from Bavaria; it was not until later in 1292 that Adolf von Nassau gave it full jurisdiction as a spiritual principality, "principatus pontificalis" . Styria had originally been Bavarian territory anyway: it had been separated from Bavaria in 1180 . In 1254 large parts of it came to Hungary. In 1261 it fell to King Ottokar and after him to the Habsburgs. The interest in the recovery of Styria by Bavaria meant that the conspirators received military support from Bavaria.

The Habsburgs were also interested in ruling Hungary and thus became competitors of the Bavarian dukes. The struggle for Hungary was a great burden for Albrecht. After the Güssing feud on August 28, 1291, in the Peace of Pressburg, he had already had to return the city of Pressburg, Güssing and other areas to the Hungarians and it had happened that armed forces from Hungary passed Vienna to the Enns and thus into the vicinity of the sphere of influence of Bavaria and Salzburg.

Traffic routes

Another reason for the emergence of tensions was that efforts were made from Bavaria and Salzburg to dominate the Alpine passes to the south. B. the Tauern passes and thus the traffic connections to Northern Italy and the Adriatic Sea . The increase in power of the Habsburg-friendly Meinhardins in Carinthia (and Tyrol ) had become unpleasant for these efforts. On the other hand, the Habsburgs were interested in controlling the connections between their home country in the Duchy of Swabia and their new possessions in the east of Austria. Your relationship with Carinthia and the possession of Styria were important steps in this direction. A Styria that would have been within Bavaria's sphere of influence would have brought the Habsburgs great disadvantages in this context as well.

The inner-alpine paths, even if they were only mule tracks in some cases , were more important in this time than in later centuries: the roads were bad, a horse could only carry about twice as much weight even with a wagon as a pack animal without a wagon could only carry a narrow one Way needed. These roads only lost their importance later with the subsidence of the war, the rise of the economic position of the cities ( city federations ), the consolidation of the seat of the Habsburgs for the area around Vienna and the improvement of the rolling stock.

Development in Switzerland: Federal Letter 1291

In Switzerland, a federation was concluded at the beginning of August 1291 , which included mutual assistance against unlawful interference with the rights of allies. That this union gave a suggestion for the alliance of the Styrian nobles is dealt with in the Styrian rhyme chronicle and despite some doubts it is seen as likely. At the same time as the uprising in Styria, there were uprisings against Duke Albrecht in Switzerland in 1291/92 .

organization

Involved

The Landsberger Bund was a conspiracy of a group of nobles, not a general uprising. Not all of the Styrian aristocrats took part.

Ulrich von Pfannberg , Friedrich von Stubenberg and Hartnid von Wildon are named as leaders of the group . The Archdiocese of Salzburg played a leading role, which is referred to as patronage or chairmanship and which is also expressed in the formulation of the Federal Letter. The involved bishop of Seckau was Leopold . Participants in the deliberations that led to the Landsberger Bund (although the list is different in the texts at hand) were the owner of the castle (German) Landsberg, Archbishop of Salzburg Konrad and, on the part of the Styrian Count Ulrich von Pfannberg, Count Walther von Sternberg, Mr. Hartnid von Wildon (for himself and his cousin Herrand), Mr. Friedrich von Stubenberg (for himself and for Otto von Stubenberg and Wulfing von Ernfels), Mr. Rudolf von Raß and Mr. Friedrich von Weißeneck . Negotiations in Leibnitz , the seat of the Salzburg vice cathedral office, had preceded.

At the same time, negotiations with Duke Otto von Niederbayern took place . The Archbishop of Salzburg made an alliance with him. Otto was given the prospect of rule over Styria.

The Styrian group of conspirators found an important supporter in Count Ulrich von Heunburg , the Carinthian governor appointed in 1270, who is also described as the leader of the uprising that followed. After Albrecht's dismissal, he was promised the margraviate of Saunien in Lower Styria.

Certificate

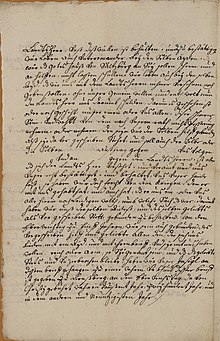

- Copy of the federal document

Participant and beginning, stamped "Archive of the Joanneum Graz"

The basis of the federal government is the “Landsberger Bundesbrief”, also known as the “Deutsch-Landsberger Bundesurkunde”, from the Eve (January 1st) 1292. According to another source, the federal government was sealed and sworn on January 2nd. The original of the certificate has not been preserved. Drafting legal documents and writing material are not to be determined from other sources and thus also not know if and to what extent the existing copies of previous translations decline. One author assumes that the original of the document was still available when a copy was made around 1731–40, but this copy is also mutilated. Whether the original actually existed back then, in the 18th century, which another author doubts, or whether the source of this copy was not an even earlier copy of the original document cannot be proven. It is possible that the original was lost in the fire of Deutschlandsberg Castle at the end of the 13th century or in one of the later conquests of this castle. Copies of the certificate (including those from the Joanneum) are in the Styrian State Archives. The treaty or the conspiracy based on it is also called "Bündnis von Deutschlandsberg", "Treaty von Deutschlandsberg", "Deutschlandsberger Bund" or "Deutsch-Landsberger Bündnis", although the place and castle were then called Landsberg . The term chosen in the lemma is also used in literature (for the degree in today's Deutschlandsberg).

The alliance document uses, as far as it is handed down in the copies, the name "Landsberg" as the location, which leaves it open whether the contract was perhaps concluded in (Windisch-) Landsberg in Lower Styria. This place was also in the sphere of influence of Salzburg (its suffragan diocese Gurk ). However, there is no evidence of this. Windisch-Landsberg would not fit the processes described in the literature any better than Deutschlandsberg, because it is remote from the rest of the events. The same applies to Landsberg am Lech , which was within the sphere of influence of the alliance partner from Bavaria. Whether the conspiracy originally had a name and what it was is unknown.

The text of the document relates to the legal status of Styria, as it was established by the Traungauers under Duke Ottokar , the Babenbergs under Duke Leopold and the Staufer German Emperor Friedrich II , and which was also recognized by Rudolf von Habsburg. The federal letter promised not to let Salzburg down and not to make any individual agreements with Albrecht I without the consent of the other federal partners. The alliance was concluded for five years. According to the rules of the Georgenberger Handfeste, the conspirators would have been obliged to seek their rights at the court of the German ruler instead of an uprising. However, Rudolf I died on July 15, 1291 and in the winter of 1291/92 the choice of his successor was not foreseeable. The conspirators also had to reckon with the fact that their opponent Albrecht would be elected king and that their applications would therefore be unsuccessful.

occasion

During Albrecht's visit to Graz in autumn 1291, a dispute broke out: Albrecht's fortune had been used up by the fighting over Hungary, and he had asked the Styrian estates for financial support. The Styrians were ready to do this, but they made certain conditions: there should be no coin valuation for five years and their right to pass on fiefdoms in the female line should be recognized. This right was expressly included in the Georgenberger Handfeste. Although his advisors advised him to do so, Albrecht emphatically declined on the advice of Abbot Heinrich von Admont, the Styrian provincial administrator. The Bishop of Seckau (a Salzburg suffragan diocese ) declared that in this case the Styrian nobles would refuse any further ties to the sovereign, there had already been harsh and unmistakable statements. Albrecht was countered that Ottokar would still be sovereign if he had controlled himself. Albrecht answered this with the question of whether this should be a declaration of war. The dispute was not settled, the parties parted in discord.

procedure

The uprising began at the beginning of 1292 when Hartnid von Wildon devastated the chamber property Albrechts Oberwildon in Central Styria, even before the feud had been formally declared ( letters of rejection ) to Albrecht . He was accused of this by his own allies because he had misappropriated the Duke's private property, which was considered ignoble. The Gjajdhof near Dobl was conquered during this phase of the uprising.

A messenger from the conspirators met on the border between Salzburg and Styria in Mauterndorf im Lungau with Archbishop Konrad IV of Praitenfurt , who had returned from his trip to the Pope in Rome (where he had been elected Bishop of Salzburg) . He informed him about Albrecht in such a way that Konrad did not travel to a conciliatory meeting with Albrecht in Vienna , as he initially planned , but went to Friesach and waited for further developments. Friesach was the administrative seat ( Vizedomamt ) of important Salzburg possessions in Carinthia and Upper Styria.

Also at the beginning of 1292, a troop of 200 Bavarians crossed the Styrian border in the Ennstal and, after conquering Admont and its monastery and making rich booty , advanced into the Murtal via the Paltental , Rottenmann and Leoben . Some castles on this route were conquered, others (like Kammern , by Wulfing von Ehrenfels) were handed over voluntarily. In Bruck allies first met with strong resistance. They besieged the city from February 15, 1292 to March 3, 1292 without success. Bruck was defended by the confidante and Marshal Albrechts, Hermann von Landenberg . Duke Albrecht came to support despite the deep winter. It is reported that 600 farmers (according to other sources a contingent of a few thousand or just 300) had to pave the way for his armed forces across the snow-covered Semmering . On March 2, 1292, he was standing with his band at Kapfenberg , about an hour's walk north of Bruck. The siege ended the next day. The rebels fled through the Mur valley to the west, towards Lungau , Salzburg and Friesach. The way back via the Ennstal was blocked by a contingent of farmers led by Admont. There were several smaller fights, for example on March 5, 1292 at Kraubath near Knittelfeld and at Unzmarkt , in which Styrian rebels were captured, and at Judenburg . In the further course of these disputes, the Baierdorf weir near Schöder , which secured the transition from the Murtal to the Ennstal over the Sölkpass for Salzburg , was also destroyed . According to another source, Landenberg and his defenders initially had to give way to the onslaught, but gathered at Knittelfeld and won together with Albrecht's troops.

Afterwards Albrecht moved on to Friesach , which was captured and destroyed by his troops. The fact that a fire that destroyed Deutschlandsberg Castle around this time can also be traced back to Albrecht's punitive action is discussed in the literature.

The End

The conspirators were captured or voluntarily submitted. Albrecht turned out to be a generous winner. He confirmed the legal status of Styria (the provincial festivals ) on March 20, 1292 in Carinthia "on the ruins of Friesach" near St. Virgil (according to another source about St. Veit ) and took peacekeeping personnel measures: Abbot Heinrich von Admont was recalled and replaced by Hartnid (I.) von Stadeck as governor of Styria. These measures are also called the “Friesach comparison”. The original of his document has not been preserved, but its content is documented by later documents ( Vidimus from 1414 and Transsumpte 1424, 1443 and later). The text of the confirmations differed in details in favor of Albrecht from the original texts: The requirement for a deterioration in coins was no longer “general” approval, but only the approval of some of those affected, and the provisions on unjustified imprisonment of Styrian ministers were protected of the empire has been replaced by that of the sovereign. The amended text passages were not used again in their original version until 1339.

The recognition of the Styrian demands (which Albrecht had rejected a few months earlier) despite his victory is attributed to the fact that he wanted to keep his back free when he ran for election to the German king. Negotiations on this candidacy were ongoing in parallel to the fight against the insurrection. In this context, Albrecht had already given commitments in the event of his election. But Albrecht was defeated in the election on May 5, 1292, Adolf von Nassau, who was elected not least because he had stood against Albrecht.

Hartnid von Wildon surrendered as the last Styrian (after a siege by Berthold von Emmerberg ) and had to pledge the Lords of Wildon, Eibiswald and Waldstein to compensate for the damage of around 4,000 marks . The Admont Abbey, which had been devastated by the Bavarian and Salzburg army, received a farm and other goods as a compensation from Wulfing von Ehrenfels. Other goods came to the Habsburgs: Kaisersberg Castle had to be handed over to Albrecht after the Battle of Kraubath. The Kapfenberg Castle , which had to be handed over by Friedrich von Stubenberg, was returned to Friedrich a little later.

After Albrecht's success against the rioters from Styria, further battles took place mainly in Carinthia.

Ulrich von Heunburg retired to the Griffen Castle of the Bamberg bishops in Carinthia, which he had been able to take over by bribing their administrators (according to another source: "in tacit agreement with the Bambergers"). From there he continued to try, together with Salzburg, to thwart Albrecht's and Meinhardin's position of power. In May 1293 Ulrich von Heunburg had to give up his resistance after he and the remaining insurgents gathered around him in Carinthia had been beaten by Duke Meinhard II on Wallersberg near Griffen and his possessions were devastated.

The differences were by the Wels peace settlement of March 1293 and by an arbitration award on 24./25. May 1293 in Linz (“Congress of Linz”, “Linzer Taendung”, “Peace of Linz”) temporarily ended. After that, essentially all those involved retained their previous position. On June 11, 1293, Count Ulrich von Heunburg swore the original feud to Duke Albrecht in Vienna . He then had to take up residence as keeper of the local castle ( Burghut ) for two years in Wiener Neustadt. This is portrayed as a kind of " figured out ".

Duke Otto von Niederbayern escaped the sanctions. Although he did not come into the possession of Styria, but ruled in Hungary irrespective of the end of the Landsberger Federal 1305-1307 as Béla V .

Abbot Heinrich von Admont, whose advice to Albrecht was ultimately the triggering cause of the uprising, was murdered in April (or on May 25) 1297. The perpetrator was Durinc Grießer, the husband of his niece and one of his former favorites , whom Abbot Heinrich had imprisoned at Strechau Castle because of false accounts . Abbot Heinrich had only seldom been to his monastery since 1285 and appeared mainly as a warrior and statesman.

Effects

Albrecht's success solidified the Habsburg rule in Styria for the long term. This became part of the “crystallization nucleus” of the later Habsburg crown lands . Albrecht got the rise of his rival Adolf von Nassau to the German ruler through renewed insecurities, to feel a “tightly woven fabric of anti-Habsburg movement”, but managed to maintain his position of power through cooperative behavior (and Adolf's failures).

For the state organization of Austria and Styria, Albrecht's victory was one of the reasons why the estates in these countries could not achieve the strong position they had in Hungary and Bohemia at the end of the 13th century. As a result of their conspiracy against the sovereign and the proven corruption of individual members, the class members largely lost their position as advisors, and the councils appointed by the sovereign from his vicinity took their place. The first beginnings of the civil service in organs of the central administration emerged. The defeat of the estates was one of the reasons for the rise of sovereign power ( house power ), which no longer necessarily relied on the benevolence of the nobility. The nobility, in turn, increasingly devoted themselves to their own power base, the manorial rule . This made the peasants more dependent, the word “ subject ” came up, the proportion of free-living peasants fell (these “old free”, so-called “ Edlingers ” had free ownership of their land, were allowed to carry weapons and had their own place of jurisdiction).

The fact that, after Albrecht's success, the border between the countries against Hungary remained in one hand, facilitated troop movements in this area and contributed to the Habsburgs' later successful Hungarian policy.

For the time being, Albrecht had also prevailed against the Salzburg archbishop, who had supported the unrest. However, the Salzburg archbishops remained opponents of the Habsburgs not only in Styria: In the summer of 1292, for example, there were alliances against Albrecht, whose partners were Otto from Lower Bavaria, the Patriarch of Aquileia and the King of Bohemia . The tensions between Salzburg and the Habsburgs remained, Bavaria also showed a hostile attitude in 1294 and in 1295/96 there was another uprising of the nobility, this time in the Austrian lands. The dispute between Albrecht and the Salzburg archbishops was only ended in 1298 after lengthy preliminary consultations, an admonition from the Pope to Albrecht and other armed conflicts such as the siege of Radstadt and the destruction of the salt works in Gosau by a "truce" (Vienna Treaty of September 24th 1297).

Some ambiguities between the Salzburg archbishops and the Habsburgs persisted. The legal status of the Salzburg areas in Styria was only clarified in terms of constitutional law through the Recession of Vienna in 1535 in favor of the Habsburgs. In the organization of the Roman Catholic Church , Styria belongs to the ecclesiastical province of Salzburg even in the 21st century , although large parts of Styria are closer to Vienna .

literature

- Alfons Dopsch : An anti-Habsburg princes' union in 1292 . In: Communications from the Austrian Institute for Historical Research (MIÖG). Volume 22 year 1901. ISSN 0073-8484 , ZDB -ID 3576-2 . Pp. 600-638.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ An illegitimate child begotten by the devil (who has fallen for him) , e. B. as a banker on the windowsill . In addition to the accusation of dishonorable origin, this means an allusion to the fact that this abbot would not have received his office properly because illegitimate birth was an obstacle to consecration in the Catholic Church of that time. “Bloch” (in the figurative sense used here) is derived from the shape of a (short) piece of round wood . The word “window hole” for an illegitimate child is documented in Upper Styria , where the Admont Monastery is also located: Hermine Sumann, Otwin Pilgram, Sepp Perchtaler, Barbara Moser: Jo eanta: some no longer familiar words spoken by our ancestors. District youth Murau . Murau 2005. p. 10. There is no evidence for another explanation, according to which the expression would be derived from the lintel of a window: The lintel is the rigid beam above a window opening in a wall. This beam used to consist of a tree trunk cut to the necessary length, a block that was immovably walled in over the window opening and supported the wall parts above. In a figurative sense, the word would represent an immobile, rigid, numb posture.

- ↑ According to today's calendar , that would be January 1, 1292 . The year 1291 in a copy of the alliance deed is considered to be an error (see the change in the copy of the Joanneum, see picture; also for Krones: Prince, authorities and estates. P. 229 in the footnote), however: January 1st was at that time common in the Catholic Church as the beginning of the year (next to the beginning of the year at the birth of Christ, at Christmas); January 1st was not generally used for the beginning of the year. There were also calendars that set New Year's Day later (e.g. March 1st or Easter). For such counts, January 1st / Eve had the year of the previous Christmas (as far as it was used in its current form). A standardization of the beginning of the year on January 1st only took place in 1691 by Pope Innocent XII. instead of. The year 1291 could therefore, depending on the method used for the beginning of the year, also be correct for the time of the drafting of the documents / transcripts. It cannot be proven whether this information is actually based on an error or whether it was chosen deliberately. Since the original document is no longer available and there is no more detailed information about the history of its creation, its scribes and their origin, no final statement can be made. To use January 1st as the day of the turn of the year: Hermann Grotefend : Calculation of the German Middle Ages and the Modern Era . Glossary, keyword circumcision style .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Berthold Sutter: The historical position of the Duchy of Styria 1192-1918. In: Gernot Dieter Hasiba, Berthold Sutter (Hrsg.): Die Steiermark. Country, people, performance. Styrian Provincial Government Graz 1971. p. 334.

- ↑ a b c Robert Baravalle: Castles and palaces of Styria. An encyclopaedic collection of the Styrian fortifications and properties, which were endowed with various privileges. Graz 1961, Stiasny publishing house. P. 61.

- ↑ a b Herwig Ebner : Castles and palaces in Styria. Graz, Leibnitz, West Styria. 2nd edition, Birken-Verlag Vienna 1981. ISBN 3-85030-028-5 . P. 18.

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Luschin von Ebengreuth : The Styrian country hand festivals. A critical contribution to the history of the class life in Styria. In: Contributions to the customer of Styrian historical sources. Edited by the Historical Association for Styria . Publishing house of the historical association, Graz. 9th year 1872, ZDB ID 212036-7 . P. 148.

- ^ Gerhard Stenzel: From castle to castle in Austria. 2nd Edition. Verlag Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1973. ISBN 3-218-00278-8 . Pp. 96-97.

- ^ Franz Xaver von Krones : Documents on the history of the sovereign principality, the administration and the estates of Styria from 1283-1411 in registers and excerpts. Publications of the Historical Commission for Styria Volume 9. Graz 1899. ZDB -ID 1141815-1 . Pp. 228-229.

- ↑ Berthold Sutter: The historical position of the Duchy of Styria 1192-1918. In: Berthold Sutter (Ed.): Die Steiermark. Country, people, performance. Styrian Provincial Government Graz 1956. p. 105.

- ↑ a b Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 601.

- ^ A b c d e Wilhelm Knaffl: From Deutsch-Landsberg's past. Verlag Leykam, Graz 1912. p. 130.

- ^ Knaffl: Deutsch-Landsberg's Past. Pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Alfons Dopsch: The importance of Duke Albrecht I for the formation of sovereignty in Austria (1282-98) (habilitation lecture at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Vienna on May 12, 1893). In: Anton Mayer (Red.): Leaves of the Association for Regional Studies of Lower Austria. New episode XXVII. Born in Vienna 1893. ZDB -ID 501693-9 . Pp. 249-250.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 100.

- ↑ Reiner Kreis (ed.), Franz Senger, Grete Scheuer (ed.): Der Reiner Schwur. 700 years. September 19, 1276 - September 19, 1976 . Festschrift for the ceremonial act of the Landtag in the Cistercian Abbey in 1976. Verlag Reiner Kreis, Rein, 1976. p. 5 (translation of the Reiner Oath into German by Walter Brunner).

- ^ Karlmann Tangl : The Counts of Heunburg. II. Department. From 1249-1322. In: Archive for customer of Austrian historical sources, ed. by the commission of the imperial academy of sciences set up for the care of patriotic history. Volume 25. Verlag der k.-k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1860. ISSN 1013-1264 , ZDB -ID 211416-1 . P. 182 in Google book search.

- ^ Hermann Baltl : Austrian legal history. Leykam Verlag Graz 1972. ISBN 3-7011-7025-8 . P. 109.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 606.

- ↑ Krones: Certificates . P. 14: No. 39 of June 22, 1290 in Erfurt .

- ^ Franz Ortner: Rudolf I. von Hoheneck. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , p. 187 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Krones: Certificates. P. 14: No. 38 of June 19, 1290 in Erfurt.

- ↑ a b Herbert Klein: Salzburg, an unfinished passport state . In: Theodor Mayer (Ed.): The Alps in the European history of the Middle Ages. Reichenau lectures 1961–1962. Lectures and Research Volume 12, ed. from the Constance Working Group for Medieval History . ZDB ID 223209-1 . Verlag Jan Thorbecke Konstanz Stuttgart 1965. p. 287.

- ^ Albert Muchar : History of the Duchy of Steiermark, Graz (then: Graetz), Damian and Sorge 1844–1874, VI. Volume, p. 74.

- ↑ a b c Sutter: historical position, (1956) p. 107.

- ^ A b Franz von Krones: Konrad IV. Von Fohnsdorf-Praitenfurt . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1882, p. 617 f.

- ↑ a b c d Michael Pirchstaller: The relations of the dukes Otto, Ludwig and Heinrich of Carinthia to King Albrecht of Austria. In: Publications of the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum. 3rd episode 50th issue (volume 3/50). Born in 1906. ISSN 0379-0231 . 264-265. [1] (PDF; 2.0 MB)

- ↑ a b Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 217 in Google Book Search.

- ↑ Hermann Wiesflecker : Meinhard the second. Tyrol, Carinthia and their neighboring countries at the end of the 13th century. Verlag Wagner, Innsbruck 1955. In: Leo Santifaller (Ed.): Publication of the Institute for Austrian Historical Research . Volume 16. ISSN 0073-8484 , ZDB -ID 3576-2 . = Raimund Klebelsberg (Ed.): Schlern writings . Volume 124. ZDB ID 503740-2 . (unchanged 2nd edition 1995 ISBN 3-7030-0287-5 ). P. 57.

- ^ Friederike Zaisberger : History of Salzburg . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1998. ISBN 978-3-486-56351-1 . Publishing house for history and politics, Vienna ISBN 3-7028-0354-8 . Pp. 35-36.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 604.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 75.

- ↑ Krones: Certificates. P. 15: No. 44 of August 28, 1291 Heimburg.

- ↑ Wiesflecker: Meinhard. P. 275.

- ↑ Klein: Salzburg Paßstaat. P. 275.

- ↑ Klein: Salzburg Paßstaat. P. 288.

- ^ Roman Sandgruber : Economy and Politics. Austrian economic history from the Middle Ages to the present. In: Herwig Wolfram (ed.): Austrian history. Verlag Ueberreuter 2005. ISBN 3-8000-3981-8 . P. 36.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 216 in Google book search.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. Pp. 613-614.

- ^ Franz Xaver von Krones : Prince, authorities and estates of the Duchy of Styria 1283-1411. Verlag Styria Graz 1900. p. 148.

- ↑ a b Helmut-Theobald Müller (ed.), Gernot Peter Obersteiner (overall scientific management): History and topography of the Deutschlandsberg district. Graz-Deutschlandsberg S. 2005. ISBN 3-90193815X . Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv und Bezirkshauptmannschaft Deutschlandsberg S. 2005. In the series: Great historical regional studies of Styria. Founded by Fritz Posch. ZDB ID 568794-9 . First volume, general part. Peter Gernot Obersteiner: settlement, administration and jurisdiction until 1848 . P. 59.

- ↑ Erich Marx: The Salzburg Vizedomamt Leibnitz. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. Edited by the Society for Salzburg Regional Studies. Salzburg 1979. ISSN 0435-8279 , ZDB -ID 2701642-0 . (Publication of the dissertation of the same name at the University of Salzburg in 1972).

- ^ Knaffl: Deutsch-Landsberg's Past. P. 129.

- ↑ Krones: Prince, Authorities and Estates. P. 147

- ↑ Krones: Certificates. P. 16: Comment on No. 45 of March 20, 1292 .

- ↑ a b Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 219 in Google Book search.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 218 in Google Book search.

- ↑ Krones: Prince, Authorities and Estates. P. 206.

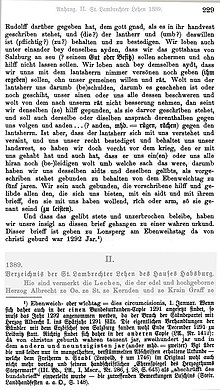

- ↑ Krones: Prince, Authorities and Estates. P. 229.

- ↑ Herfried Marek, Ewald Neffe, Herwig Ebner: Castles and palaces in Styria. Wörschach 2004. ISBN 3-9501573-1-X . P. 187.

- ↑ a b Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 97.

- ^ Baron Leopold von Stadl: Brightly shining mirror of honor of the Duke of Steyr. 3rd book p. 643 (Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv I Ms. Nr. 286, quoted from Luschin: Landhandfeste. P. 148).

- ↑ Krones: Prince, Authorities and Stands, p. 229 footnote.

- ↑ Styrian State Archive No. 1412, quoted from Knaffl, Deutsch-Landsbergs Geschichte. FN 3 p. 129 and Luschin: Landhandfeste. P. 148.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 612 footnote 2.

- ↑ a b Alois Niederstätter : 1278–1411. The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. In: Herwig Wolfram (ed.): Austrian history. Verlag Ueberreuter 2001. ISBN 3-8000-3526-X . P. 100.

- ↑ a b c Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 619.

- ↑ a b Heinz Dopsch: Konrad IV. Von Fohnsdorf-Praitenfurt. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , p. 525 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Krones: Prince, Authorities and Estates. P. 191.

- ↑ a b Wiesflecker: Meinhard. P. 276.

- ^ Gerhard Fischer: Osterwitz. a miraculous place in the high pürg. Life, joy and suffering of an area and its inhabitants. Osterwitz 2002. Editor and publisher: Osterwitz community. Production: Simadruck Aigner & Weisi, Deutschlandsberg. No ISBN. P. 221.

- ^ Niederstätter: Dominion Austria. P. 99.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 215 in Google Book search.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 78.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. Pp. 213–214 in Google Book Search.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 96.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 80.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. Pp. 219–220 in Google Book Search.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 79.

- ^ Knaffl: Deutsch-Landsberg's Past. P. 82.

- ↑ Marek et al. a .: Castles and palaces. P. 68.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 221 in Google Book Search.

- ↑ Burg Alt-Landenberg ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. : Herrmann von Landenberg as Secretarius and Marshal Albrechts.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 222 in the Google book search.

- ↑ a b Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 168.

- ↑ Matthäus Merian : Topographia Provinciarum Austriacarum . Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt am Mayn 1679, page 197. Digital full-text edition in Wikisource . (Version of June 7, 2012).

- ↑ a b Berthold Sutter: Styria in times of upheaval. To the struggle for Styria in the Interregnum and their achievements after 1282 to save the rule of the House of Habsburg in Austria. In: Othmar Pickl: 800 years of Styria and Austria 1192–1992: The contribution of Styria to Austria's greatness. Self-published by the Historical Commission for Styria, Graz 1992. Research on the historical regional studies of Styria. Volume 35. ISBN 3-901251-00-6 , ZDB -ID 501108-5 . Pp. 131-132.

- ↑ a b c d Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 223 in Google Book Search.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. Pp. 166-167.

- ↑ a b c Gerald Gänser: The early Habsburgs and Steiermann market (1282-1424). In: Gerhard Pferschy, Peter Krenn : Die Steiermark. Bridge and bulwark. Catalog of the state exhibition May 3 to October 26, 1986, Herberstein Castle near Stubenberg. Publications of the Steiermärkisches Landesarchives, Volume 16. Graz 1986. ISSN 0434-3891 , ZDB -ID 561078-3 . P. 96.

- ↑ Werner Tscherne : From Lonsperch to Deutschlandsberg. Self-published by the municipality of Deutschlandsberg. 1990, p. 57.

- ↑ Wiesflecker: Meinhard. P. 277.

- ↑ Krones: Certificates. P. 16: No. 45 of March 20, 1292 in Friesach.

- ↑ Walter Kleindel: Austria. History and culture data. Ueberreuter Verlag Vienna 1978. p. 66.

- ^ Luschin: Landhandfeste. Pp. 149, 183.

- ↑ Dopsch: Meaning of Albrechts. P. 255 .

- ^ Luschin: Landhandfeste. Pp. 150–151 and (date December 6, 1339) p. 183.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 88.

- ↑ a b Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 224 in Google Book Search.

- ^ Regesta Imperii (RI): RI VI, 2 n. 5, 6 and 7, in: Regesta Imperii Online Department: VI. Rudolf I - Henry VII. 1273-1313. Volume: VI, 2 Adolf von Nassau 1291–1298: print version p. 3.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 90.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 187.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 188.

- ^ Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 180.

- ↑ a b c Tangl: Count Heunburg. P. 244 in Google Book search.

- ↑ a b Herbert Stejskal: Carinthia. History and culture in pictures and documents. From prehistoric times to the present. Carinthia University Press. Klagenfurt 1985. ISBN 3-85378-500-X . P. 83.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 629.

- ^ Muchar: History of the Duchy of Styria. P. 94.

- ^ Tangl: Count Heunburg. Pp. 246–247 in Google Book Search.

- ^ Sutter, in: Hasiba: Steiermark. P. 335.

- ↑ a b Stenzel: From castle to castle. P. 101.

- ↑ Walter Zitzenbacher (Ed.): Landeschronik der Steiermark: 3000 years in data, documents and images. Brandstätter Verlag Munich 1988. ISBN 3-85447-255-2 . P. 85.

- ^ Otmar Pickl: 800 Years of Styria and Austria 1192–1992. The services of Styria for the entire state. In: Helmuth Feigl (Red.): Yearbook for regional studies of Lower Austria. New episode, Volume 62, 1996, Part 1. Declaration of the Lower Austrian Regional Studies Association for the Ostarrîchi Millenium. ISSN 1016-2712 , ZDB -ID 501694-0 , p. 187 ( PDF on ZOBODAT ).

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 626.

- ↑ Dopsch: Meaning of Albrechts. Pp. 253-254 .

- ^ Baltl: legal history. P. 96.

- ^ Karl Spreitzhofer: The Union of 1192 and the "dowry" of Styria. In: Othmar Pickl: 800 years of Styria and Austria 1192–1992: The contribution of Styria to Austria's greatness. Self-published by the Historical Commission for Styria, Graz 1992. Research on the historical regional studies of Styria. Volume 35. ISBN 3-901251-00-6 , ZDB -ID 501108-5 . P. 60.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 620.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. Pp. 617-618.

- ^ Dopsch: Fürstenbund. P. 630.

- ^ Regesta Imperii (RI): RI VI, 2 n. 1022, in: Regesta Imperii Online Department: VI. Rudolf I - Henry VII. 1273-1313. Volume: VI, 2 Adolf von Nassau 1291–1298. Pp. 380-381, around June .

- ^ Zaisberger: History of Salzburg. P. 37.

- ↑ Krones: Certificates. P. 21: No. 62 of September 24, 1297.