Museum of European Cultures

The Museum of European Cultures (MEK) is a cultural and everyday history museum in Berlin , which is a hybrid of museums for everyday culture, ethnological museums and European museums. It deals with the worlds of life in Germany and Europe from the 18th century to the present. His permanent collection presentation as well as the museum research work are aimed at cultural contacts across national and linguistic borders. With 285,000 exhibits, the Museum of European Cultures is one of the largest institutions of its kind. The collections overlap with the Nordic Museum in Stockholm and the Austrian Museum of Folklore in Vienna . However, the collections of the two museums are not explicitly dedicated to Europe. The Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean in Marseille is similar to the Museum of European Cultures in its approach, but is oriented towards the Mediterranean region. There is also an overlap with the House of European History in Brussels , which however does not have a historical collection.

The museum is part of the Association of National Museums in Berlin of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation . It was created in 1999 from the amalgamation of the Folklore Museum with the Europe Department of the Ethnographic Museum . The Bruno-Paul-Bau, the oldest building in the Dahlem Museum Quarter , has been the museum building for the presentation of the collection since 2005 . After the renovation, the permanent exhibition Kulturkontakte opened there in 2011 . Life in Europe .

The nucleus of the collection was the so-called European cupboard in the New Museum , which opened in 1859. In 1889 Rudolf Virchow founded the folklore museum in Berlin on a private initiative with the Museum for German Folk Costumes and Home Crafts. It was not until 1904 that the collection was incorporated into the Royal Museums in Berlin, but not as an independent museum, but as the Royal Collection for German Folklore of the prehistoric department of the Ethnographic Museum. Until the founding of the State Museum for German Folklore in the Association of State Museums in Berlin in 1935, the museum struggled with a considerable lack of space. During National Socialism, the museum and its director Konrad Hahm approached the national ideology in order to preserve the institutional quality on the one hand and to have greater resources available on the other. During the Second World War, 80 percent of the historical collection was lost. In the course of the division of Germany there were subsequently folklore parallel museums in West and East Berlin. Although the salvage of the remains of the collection and the resumption of museum operations began in East Berlin immediately after the war, the Museum of Folklore was not constituted until the mid-1950s and was subsequently housed in the Pergamon Museum on Museum Island . In West Berlin, the Museum of German Folklore was not re-established until 1966 on the basis of the objects returned by the American occupiers and was located in Berlin-Dahlem from the mid-1970s. In both East and West Berlin, the focus was on rebuilding the collections in the traditional lines of pre-war activity. Only gradually did this focus move away from the everyday and work culture of the village-rural area towards the life of the urban population and the present. After reunification, both museums were merged to form the Museum of Folklore and the merger with the Europe Department of the Museum of Ethnology, which had been founded in the mid-1930s, was promoted.

The collection includes tangible and intangible cultural heritage primarily from Germany and other European countries, with a focus on Eastern and Southeastern Europe. The holdings of textiles, popular graphics and photographs as well as the thematic collections on naive art , rituals and forms of religiosity as well as childhood and youth culture are significant . The historical collections of some ethnic minorities in Europe, especially the Sami and Crimean Tatars, are unique .

In 2019, the Museum of European Cultures had 24,000 visitors.

history

See also: List of Directors of the Museum of European Cultures

Prehistory: First European ethnographica in the Berlin collections (until 1889)

Objects from European folklore were shown for the first time in Berlin in the so-called European cabinet of the New Museum , which opened in 1859 and which, among other things, housed the ethnographic collection. As a result, the Ethnographic Museum was founded in 1873 , which also included a European collection with around 250 objects. In 1878 Rudolf Virchow applied to the responsible ministry to establish a national department for costumes and implements in the museum. He was inspired by the collection and exhibition of the Nordic Museum in Stockholm , founded in 1872 by Artur Hazelius , which he had visited in 1874, and the successful presentation of this collection at the Paris World Exhibition in 1878 . Virchow assumed that the items for such a department in the Ethnographic Museum would still have been available in the German regions despite advancing industrialization. However, the Ministry did not take up his initiative. The installation of the already existing European ethnographica in the museum's own building opened in 1886 was not possible due to the lack of space. That is why the idea was developed to separate the European and non-European collections: a national museum was to be created that would be devoted to the history of the European peoples with a focus on German culture. It was not just conflicting scientific opinions and funding problems that prevented such a project from being realized. The political framework also contributed to this, which after the establishment of the German Empire in 1871 resulted in a differentiating interest between the national frame of reference and colonial political goals, neglecting the European area.

Development of the museum in the empire

Virchow's commitment and the museum for German folk costumes and household products (1889–1904)

After Virchow's proposal to set up a separate department within the framework of the Völkerkundemuseum was rejected by the Ministry of Culture, he pushed ahead with the establishment of a national museum for equipment and costumes on a private initiative. For this purpose, he suggested a collection trip to Mönchgut on Rügen , as in this fishing village, which he had visited in 1886, clothing and household items were largely untouched by industrialization. The collection project was carried out by the Szczecin teacher Ulrich Jahn , who had previously carried out surveys on legends and popular beliefs in Pomerania , and financed by Louis Castan , the owner of the Berlin Panopticum . Jahn collected women's and men's costumes, fishing gear and household items such as richly decorated fescue leaves . In November 1888, the Mönchgut collection was presented in the Panopticum Castans, as there was also the necessary expertise for the display of the costume figures. Due to the success of this exhibition, Virchow founded a committee in 1889 to make further acquisitions and thus enable the establishment of a German museum for costumes and equipment . This included members of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory , museum directors, bankers, merchants and lawyers. The aim was to collect objects from pre-industrial German culture as well as from the German-speaking areas of Switzerland and Austria. In the same year, Minister of Culture Gustav von Goßler , who shared Virchow's anthropological interest, offered him seven rooms on the ground floor of the Palais Creutz in Klosterstrasse , which was used by the Hygiene Institute. On the occasion of this occasion, Virchow and the committee founded the Museum for Costumes and Crafts . On October 27, 1889, the museum was opened in the premises of the Palais Creutz under the name Museum for German Folk Costumes and Home Crafts .

Virchow saw connections to prehistory and early history in the form, decoration and purpose of the objects, but also did not neglect more recent phenomena such as national costumes, which as national costumes were increasingly in the context of recent historical and political developments. He showed particular interest in the constant forms in house construction. This was also reflected in the collection and presentation of the museum for German folk costumes and domestic products, which included house models. However, Virchow did not consider setting up an open-air museum with various types of houses. Following the example of the Nordic Museum in Stockholm, five rooms were to be set up in which various objects were to be brought together to form cultural-historical images. Only the Spreewaldstube and the Alsatian parlor were actually realized, the former being one of the museum's attractions. In preparation for the opening, various collecting trips were undertaken, which were made possible in particular by loans from the banker Alexander Meyer-Cohn , who also financed further purchases. Ulrich Jahn, who had been director of the museum since spring 1889, traveled through the Mark Brandenburg , Pomerania , Lusatia , the Vierlande and the Alte Land . Adrian Jacobsen worked for the museum in Bavaria , who had previously collected for the Völkerkundemuseum and was also the first custodian of the museum under Jahn for a short time . In Alsace and Switzerland was Robert Forrer for the museum active in Warmia and Memel was Adalbert Bezzenberger amassed, the objects for the museum. Virchow himself also collected some objects. In addition to places that were quite isolated due to the traffic situation and where a pronounced folk culture was passed on, the focus of the collecting activity was on regions with foreign populations such as the Spreewald and the Baltic States . This explains the intensive efforts to acquire a Lithuanian collection from East Prussia, which only arrived in Berlin after the museum opened. The lively collecting activity meant that the museum's premises were already too small when it opened; large stocks had to be deposited.

The opening of the museum for German folk costumes and domestic products met with great national and international interest. In German-speaking countries in particular, the collection efforts of the Berlin Museum were seen as competition with their own interests. Heinrich Angst , later director of the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, took a critical look at Robert Forrer's collecting trip and the emigration of national cultural assets. Michael Haberlandt , who founded the Austrian Museum of Folklore in Vienna in 1897 , published lists of Austrian objects that came to the Berlin Museum. As a result, Virchow continued to try to get the collection into the Royal Museums. Despite the separation of folklore from anthropology as a result of the founding of the Berlin Society for Folklore by Karl Weinhold in 1890, he still strived for a link to prehistory and anthropology. In 1891, Virchow, together with Albert Voss , the director of the prehistoric department of the Völkerkundemuseum, submitted an application to the Ministry of Culture for a new German Museum for Antiquities and Folklore , which would combine the museum collection with the prehistoric department of the Völkerkundemuseum and the collection of the Anthropological Society. Since this venture did not lead to success, Virchow used international exhibition participations to advertise his institution: In 1891 the Museum for German Folk Costumes and Domestic Products participated in the German Exhibition in London with room furnishings from North and East Frisia . In 1893 the museum occupied a large area at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago with a German-ethnographic exhibition . A consortium of banks and German business people in New York took over the financing of this project. For this occasion, director Jahn collected new objects on collecting trips, whose return to Germany Virchow secured in advance as a national cultural asset. The German ethnographic exhibition in Chicago was the largest presentation of a folklore collection at home and abroad to date. In 1894 the Chicago collection was loaned to the museum, and in 1898 the lengthy negotiations about a donation came to a positive conclusion. In addition to participating in international exhibitions, the museum also used the Berlin trade exhibition in 1896 in Treptower Park for self-promotion: the Patzenhofer brewery built its bar in the form of a Spreewald house, in which the museum's popular Spreewald room was then set up. At the end of the 1890s, in view of the limited space in the Palais Creutz, special exhibitions with holdings from the collection began to be held at other exhibition locations in Berlin.

For a long time, however, these efforts did not have the effect of being incorporated into the Royal Collections. In 1902, when Virchow, the museum's most important sponsor and initiator, died, the museum was given notice of the rooms in the Palais Creutz. The affiliation of the collection to the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg had already been considered, now the idea of an affiliation to the Märkisches Museum arose in order to secure it for the Reich capital. But this approach also failed, which meant that the collection continued to migrate. There were offers to take over from Weimar, where a folklore museum was planned, and from Hamburg, where objects on the folk culture of the Hamburg area had already been collected through the initiative of Justus Brinckmann and the accommodation of the collection in an extension of the Museum of Art and Industry and possibly an open-air museum were planned. The museum association planned to accept one of these offers, if the Ministry of Culture could not be accepted into the Association of Royal Museums in Berlin. James Simon , the second chairman of the association, persuaded Kaiser Wilhelm II to intervene, so that in 1904, by decision of the Ministry of Culture, the museum was assigned to the prehistoric department of the Ethnographic Museum with its own purchase budget as a collection for German folklore .

Integration into the Royal Museums as the Royal Collection for German Folklore (1904–1918)

In 1904, two years after Virchow's death, the museum was accepted into the Association of Royal Museums as the Royal Collection for German Folklore and assigned to the prehistoric department of the Völkerkundemuseum, and Karl Brunner , who had been an assistant at the prehistoric collection until then , took over the management Of the collection. The expansion of the collection was continued by the acquisitions commission of the private association, which now operated as the Association of the Collection for German Folklore . After the chairman Max Bartels died, James Simon took over the chairmanship in 1904. Around the integration of the museum into the Royal Museums in Berlin, the debate about the possible establishment of a central open-air museum in Berlin culminated in the years 1902 to 1905. A point of reference for the discussion was the Skansen Museum in Stockholm, and in such a museum the strong interest in house research, which was important both in Germany and in other European countries, could have been reflected. Ultimately, the general director of the Berlin museums, Wilhelm von Bode , did not take up these efforts, but pursued his own plans, in particular the construction of the Pergamon Museum . The open-air museum did not appear in his museum publication from 1907. The rejection by Bode led to a loss of reputation for the museum, which Brunner tried to counter with intensified activities such as participation in exhibitions in Berlin, increased contacts with the Association for Folklore and the strengthening of the scientific profile. Even Carl Schuchardt as director of the prehistoric collections position strengthened the folk art collection in the Museum Association.

The other European collections at the Völkerkundemuseum were looked after by the heads of the Near Eastern and Indian departments, but there was no systematic expansion of these holdings. Some objects were also transferred to the Collection for German Folklore. This separation of the European and German collections was to continue in the further history of the museum until the recent past. Before the First World War, significant purchases were made and donations were integrated into the collection, so that its character changed significantly in the direction of popular belief, customs and manners.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the museum's opening in 1914, Brunner set up a new collection presentation: Inspired by Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer , director of the Swiss Museum of Folklore in Basel, he grouped the holdings more closely into comparative series. At the same time, however, Brunner retained the mixed arrangement in parlor furnishings, which has been a hallmark of the exhibition since the museum opened. On the occasion of the anniversary, the General Management of the Royal Museums took the view that the museum needed better space. However, the course of the war prevented an improvement in the spatial situation.

The Collection of German Folklore in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Under the conditions of the democratic republic, the situation of the collection in the network of the now National Museums in Berlin did not improve, the spatial problem remained unsolved. Although Brunner worked on parts of the collection such as the rural wooden tools with wax decorations, peasant pottery, rune calendars and the Telgte starvation cloth, the situation remained precarious: When Brunner retired from his post on October 1, 1928, the collection had grown to 30,000 objects. however, in spite of funds approved by the Prussian state parliament in 1925 and 1928, it was not adequately accommodated. There were no government funds and, apart from the custodian, no scientific staff.

The successor to Brummer came on November 1, 1928 Konrad Hahm (1928–1943), who had been an advisor to the Reich Art Warden Edwin Redslob in Berlin since 1922 . There he mainly worked for the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Handwerkskultur. The position at the Reichskunstwart allowed Hahm to get to know administrative processes and to make both national and international contacts in the field of scientific theory, which he was able to make fruitful for his work on the collection. For example, Hahm supervised the preparations on the German side for the international folk art congress in Prague in May 1928, which was suggested by the Reichskunstwart. At this congress, the International Folk Art Commission was founded, to which 24 national commissions belonged. The German Folk Art Commission was chaired by Otto Lehmann , while Hahm held the position of managing director. The exact circumstances of the appointment of Hahm as head of the folklore collection of the National Museums in Berlin are not known; He was probably already in contact with the collection as part of the preparations for the folk art exhibition planned for 1929 in Dresden and knew its problems. As the head of the folklore collection, Hahm subsequently also took over the chairmanship of the German Folk Art Commission.

On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the museum in October 1929, Hahm, together with the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the Association of German Associations for Folklore, organized an exhibition in the premises of the Academy of the Arts on Pariser Platz , which was opened by Max Liebermann . The concept of the exhibition with the separation of the objects according to material groups followed the principles that had been developed in the working group for German craftsmanship at the Reichskunstwart. With this show, Hahm intended on the one hand to convey the importance of the collection to the public and at the same time to draw attention to the unsatisfactory spatial situation. This exhibition met with great interest from the population of Berlin, whose reactions ranged from general enthusiasm to discourses on the “ethnic-German industrial diligence”. With this exhibition, Hahm was able to draw attention to his collection. The question of space remained unsolved, but by employing three academic staff and additional technical staff for library, administration and storage in work contracts, Hahm succeeded in significantly improving the personnel situation and thus increasing the efficiency of the institution. Together with the Association of Folk Studies Associations, Hahm developed concepts for the museum and submitted submissions to the Prussian Ministry of Culture. As a new museum building, three options were considered: the building complex Prinz-Albrechtstrasse 8, the Grunewald hunting lodge and the Bellevue palace . The latter two offered the possibility of setting up open-air facilities. Hahm preferred Bellevue because it was centrally located and well connected in terms of transport, but the location in Grunewald was favored by the ministerial side. In 1930 a cost estimate was issued for the necessary renovations in the Grunewald hunting lodge, but no final decision was made due to the global economic crisis.

The Folklore Collection under National Socialism (1933–1945)

Development of the collection and establishment of the State Museum for German Folklore (1935)

After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, as head of the collection, Hahm adapted his use of language to the new requirements, on the one hand, and used the unclear conditions in the cultural sector to advance his plans for the State Collection of German Folk Art on the other. This was expressed in 1933 both in the signature of a commitment to Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP and in joining the party, which he did not try to make known. While Hahm's previous sponsor, Edwin Redslob, was dismissed and the post of Reichskunstwart was removed in 1933, he pursued his plans in collaboration with Finance Minister Johannes Popitz , focusing his efforts solely on Bellevue Palace. In January 1934, the castle was taken over as a museum building and the necessary renovations began. At this point in time, the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and National Education , which was responsible for museums and which only emerged in May 1934 from the merger of the Prussian Ministry of Culture and the responsibility for education that had been outsourced from the Reich Ministry of the Interior, was not yet active.

On October 1, 1935, the State Museum for German Folklore, which was now a separate institution in the Association of State Museums in Berlin, opened in Bellevue Palace. The opening addresses were given by a Polish folklorist and the renowned experts Sigurd Erixon from Sweden and Georges-Henri Rivière from France. The exhibition on German peasant art, shown in the central building, met the ideological expectations of the National Socialists by far: It began with an introduction to Germanic peasantry, which had been taken over as a loan from the Neumünster Industrial Museum , and also included a section on symbolism , which was used to convey the particularly served the ideologically shaped image of the German peasant. On the occasion of the opening, Hahm also emphasized that his house was now emerging from a fifty-year shadowy existence, criticizing the shortcomings of the previous policy of the Ministry of Culture and contrasting it with the positive developments in National Socialism. Under Hitler's leadership, the intellectual elite and the state could have been united by a common völkisch view of history. With the opening exhibition, however, Hahm also embarked on a new curatorial path: he deviated from the regional principle of origin, which was customary in ethnology, and instead organized the objects according to material groups that corresponded to landfilling based on conservation considerations. With the presentation in spacious showcases, Hahm achieved a clear effect that differed from the chaotic impression of the former exhibition rooms. In addition, there were other modern presentation methods with the isolation of individual pieces and the colored wall design. Hahm himself related this to the aesthetics of a department store and used it as a means of establishing a connection between folk culture and high culture.

Despite his good connection with Finance Minister Popitz, Hahm struggled with limited financial resources and had to accept the minister's influence on the content. The planned opening of the Spree wing of Bellevue Palace, which was to be used for the permanent exhibition, was delayed from June 1937 to May 1938 for financial reasons. Of the five planned topics, the first, which was to deal with tribal and racial aspects, was opened Popitz recommendation to compensate for reduced funds deleted. The topic of German handicraft culture was also dropped, as the museum was already taking part in a traveling exhibition of the imperial class of German handicrafts , which was also to be shown in Bellevue Palace. Despite the limited scope, Hahm succeeded in developing from the type of the foam museum the new type of the "mobile work museum", which was characterized by changing exhibitions and lectures. This concept was perceived and adapted across national borders. Rivière's considerations to implement a “living museum” in France followed Hahm's example. Hahm bought these possibilities with the ideological commissioning of his house. Nevertheless, the permanent exhibition at Bellevue Palace never opened, as the museum had to vacate it at the beginning of 1938 so that it could be used as a guest house for the German Reich. In this situation, Hahm demanded that the responsible officers in the Ministry of Finance and Culture and the General Director of the State Museums Otto Kümmel create new jobs and the necessary spatial and financial facilities to maintain and continue the activities of the museum, particularly in educational work to increase. The museum initially moved - as suggested by Hahm - to the Prinzessinnenpalais located on Unter den Linden , while the magazine was moved to the house of the Great National Mother Lodge "To the Three Worlds" in Splittgerbergasse, which was dissolved by the National Socialists . The work of the museum subsequently concentrated primarily on the school exhibitions, four of which were devoted to a different group of materials between 1939 and 1943. These were carried out by Adolf Reichwein , who was a progressive educator and active resistance fighter in the Kreisau district .

Under Hahm, the museum also extended beyond its own limited sphere of activity: In October 1935, the German Folk Art Commission was linked as a registered association to the State Museum for German Folklore and financially assigned to the State Museums in Berlin. The commission made plans to found an institute for folk art research at the museum. Bernhard Rust , the Reich Minister for Science, National Education and Upbringing, approved a teaching assignment for research into German folk art at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin and gave the order to set up the institute at the museum, but due to an objection by the German Research Association Ahnenerbe did not take any further steps to implement it. In June 1940, the Institute for Folk Art Research was finally founded at the Berlin University and thus an affiliation to the museum was finally rejected. Against the objections of the National Socialist German Lecturer Association , Hahm received an honorary professorship .

Hahm used his contacts to the Ahnenerbe partly in the interest of the museum. Joseph Otto Plassmann , for example , who was transferring manuscripts and archives from various castles that had been relocated in France back to Paris, asked Hahm on July 30, 1940 whether he had any wishes. Hahm also pointed out the Ahnenerbe in the Netherlands, among other things, to a high loom , which aroused interest in the contact there. Hahm's Museum then benefited directly from the robbery of cultural property in the occupied parts of the Soviet Union: Hahm reminded Plassmann that the Ukrainian private scholar Zaloziecki in Chernivtsi had given his folklore collection to the German consul as a gift for his museum in order to bring it to safety before the Soviet occupation in 1940 . After the invasion of the Red Army, the collection still in Zaloziecki's house was released on the intervention of the consul. But then their trail was lost. At the beginning of 1942, Hahm inquired of the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and inquired about the whereabouts of the collection. When he learned that she was being held there, he asked for her to be released. Since this could only be done after approval by the Ahnenerbe, its director Wolfram Sievers arranged for the transfer to be carried out on the condition that all of the Hutsul materials of particular interest to Heinrich Himmler be prepared. After Hahm's death in 1943, Otto Bramm was probably nominally appointed acting director. Due to his absence due to the war, Oswald Adolf Erich ran the museum. Erich expanded the collection despite the worsening war situation, although the relocation of the holdings had already begun. Most of his acquisitions were lost to war.

Although the most valuable museum holdings were moved to cellars, bunkers and manor houses at nine different locations in Berlin , Brandenburg and Western Pomerania during the last years of the war , the museum lost around 80 percent of its collection during the war. The objects brought from the Berlin flak tower at the zoo to the potash shafts in Thuringia were transported to Wiesbaden by the American occupation after the end of the war, while the remaining parts of the inventory remaining in the flak tower were transported to the Soviet Union by the Soviet occupying forces in the summer of 1945 with other high-quality museum goods.

The Eurasia Department at the Ethnographic Museum

The Eurasia Department was set up in the Museum of Ethnology at almost the same time as the Museum of German Folklore was founded. In it the collections of the Sámi and other Finno-Ugric speaking ethnic groups in Russia were summarized. These objects were acquired at the end of the 19th century and administered by the Indian department. Another inventory was 500 Tartar objects that were acquired by the Findeisen couple in the Crimea. From 1928 to 1934, Hans Findeisen was employed by the museum in several contracts for work, but despite several efforts, he was not given a permanent position. The Africanist and ethnologist Hermann Baumann took advantage of Findeisen's departure to take over a custody at the museum that he would not have received in the Africa department. With the support of the General Director of the State Museums, Otto Kümmel , who was also director of the Völkerkundemuseum, Baumann established the Eurasia department at the end of 1934. A year earlier he had curated the special exhibition From Digging Stick to Plow and published the accompanying catalog in which he Germanic ideology propagated by the National Socialists. This ideological support together with his NSDAP membership since 1932 should have helped Baumann to his advancement within the museum. He sought to expand the museum's European and North Asian collections. The first step was an exchange between the Völkerkundemuseum and the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde: the former transferred the few objects from German-speaking areas, the latter surrendered its European holdings. In addition, she started her own gainful activity from 1935. The most important acquisition was an exchange between the Völkerkundemuseum and the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne in 1937; Berlin surrendered 300 non-European artifacts, which were referred to as duplicates, and received a collection of over 600 objects in return. Other exchanges concerned folklore museums from Ukraine and Estonia. Baumann's own interest in the ethnology of Europe and North Asia does not seem to have existed, since he neither undertook collecting trips nor published on these topics. However, he used the department he was trying to establish as a career vehicle. Between 1935 and 1939, on the other hand, the photo reporter Gustav Adolf Küppers , who was committed to the blood-and-soil ideology , undertook five collecting trips through Southeastern Europe for the museum, which provided access to around 3500 ethnographica and 1600 ethnographic photographs from Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and Yugoslavia provided. Baumann left the museum in 1939 for a professorship in ethnology at the University of Vienna, and Küppers was also able to use his activities for the museum for his further career as a consultant in the Balkans department of the military economic staff at OKW .

Folklore parallel museums in East and West (1945–1989)

Development in East Berlin

After the end of the war, Werner Stief (1905–1982) was the only remaining research associate at the museum, which is why in May 1945 he was given management responsibility. In addition to the restoration of parts of the storage building on Splittgerbergasse, the safeguarding of the collections by excavations in the destroyed wing of the building and the return of relocation sites were central to the early museum work after the war. All textiles and objects made of leather, wood and paper were burned in the rubble of the warehouse, and much of the ceramics were also destroyed. However, parts of Andree-Eysen's votive collection were secured. In 1945 employees were able to return objects that had been relocated to smaller cellars in Berlin-Lichtenberg and on Jüdenstrasse. Relocating the holdings outside of Berlin turned out to be more difficult. In the course of 1946 the employees brought back the 10,000 volumes of the library and some pieces of furniture from Kirch Baggendorf . In 1947 a small proportion of the objects were returned to Gut Bauer near Lasan , and a few more pieces of furniture followed two years later. Both furniture and clothing were lost from the collection because they had been given to displaced persons. The around 3,000 objects stored in Lebus Castle were still there at the end of the war, but were not returned immediately and were lost to the museum over time. In addition to a few summary inventories, the museum lacked almost the entire scientific documentation of the collection; the main catalog with detailed object descriptions as well as drawings and object photos was almost a total loss. This made it difficult to identify the rescued collections.

Active museum work slowly started again in 1945. Photo lectures were held and courses on weaving, knitting and spinning were held. In December 1946, the museum took part in the exhibition Reunion with museum items organized by the Soviet military administration in the Berlin Palace used by the Museum of Applied Arts . In addition to his work as director of the Folklore Museum, Stief worked as a curator at the Ethnographic Museum in the American zone of occupation. Although the Soviet military administration had prohibited the relocation of cultural property, he moved library holdings and working materials from the Soviet to the American zone. With the currency reform of August 14, 1948, Stief gave up his position as director and subsequently only worked for the Völkerkundemuseum in West Berlin. The spatial location of the museum was precarious. In the first half of 1948, Stief did not respond to the municipal authorities' offer to make Köpenick Castle available as a museum location. As a result, instructions were issued to leave the building in Splittgerbergasse and to store the collections in the basement of the Berlin Palace. In autumn 1948 Ludwig Justi, as General Director of the National Museums in Berlin, was able to reverse this decision. In the course of the demolition of the Berlin Palace, the holdings of the Kunstgewerbemuseum were relocated to the restored wing of the former lodge building and its director Martin Klar also took over the provisional management of the folklore museum.

As a result, the State Museum for German Folklore eked a shadowy existence in the network of the State Museums in Berlin. Wolfgang Steinitz as director of the Institute for Folklore of the German Academy of Sciences and Paul Nedo , director of the Central House for Lay Art in Leipzig, campaigned publicly for the collection. Steinitz included the collection in the exhibition German Folk Art as part of the German Festival of Folk Art in Berlin in the summer of 1952. However, this did not change the location of the museum. In addition, there were considerations to incorporate the collection into the Central House for Lay Art in Leipzig. Such considerations met with Justi's resistance, who wanted to keep them as part of the Berlin State Museums. The State Commission for Art Affairs , however, did not feel responsible for the folklore collection, even if the class for social sciences of the German Academy of Sciences positioned itself on October 1, 1953 with a resolution for the reopening. Justi maneuvered under the conditions with the renaming of the museum in the Museum of Folk Art, which was to address the responsibility of the State Commission for Art Affairs, and the provision of premises in the restored Pergamon Museum . He also improved the staffing. The future direction of the museum remained controversial, however, a planned folk art exhibition was postponed several times and ultimately not realized. However, in 1953 collection activities were resumed, which had been almost completely discontinued after the war: between 1953 and 1955, between 2500 and 3000 objects were added to the museum's collection. These came on the one hand from private collectors like Hans Hahne from Halle , who from 1918 had collected around 1,000 objects, some of them with Berlin provenance - for example from the Chicago collection - and on the other hand from the holdings of other museums in the GDR.

In 1956 Ulrich Steinmann (1906–1983), who had changed to the museum as an employee in the previous year, was appointed director of the Museum of Folk Art. On the one hand, he continued to rebuild the collection and set up the first exhibition of the Museum für Volkunst in 16 rooms of the north wing on the upper floor of the Pergamon Museum. This followed traditional patterns of listing technological, thematic and mostly landscape aspects and was characterized by the large gaps in the existing structure. When the Soviet Union returned parts of the holdings of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin to the GDR in autumn 1958, the museum's collections, which now also comprised around 400 returned objects, were put into storage. After Wolfgang Steinitz intervened again, a single room of 300 square meters on the ground floor of the Pergamon Museum was made available to the museum, which had been called the Museum für Volkskunde again since 1958. In response to this spatial situation, the museum expanded with a branch in Wandlitz , where Steinmann showed the collection of agricultural implements that he had brought together from 1967 as a study collection in cooperation with the Wandlitz Museum of Local History in a converted barn. As a result, a study collection on fishing was also shown there. In cooperation with the Office for Monument Preservation of the Magistrate of Berlin and the Council for Museum Affairs of the GDR , a suitable historical building structure in East Berlin was sought, in which the museum could have been housed, and appropriate concepts developed. In 1960 Steinmann also pursued considerations for an open-air museum, which was based on ideas shortly after the turn of the century, which is why he also acquired entire workshop equipment for the museum. Ultimately, however, there was no solution to the space problem.

As part of the considerations for a new museum building, a collection profile was developed that was increasingly geared towards the material culture of the " proletariat " and also more closely met the ideological demands made on folklore in the GDR. Steinmann retired in November 1971. After a one-year transition phase, he was succeeded by Wolfgang Jacobeit (1921–2018) as director. Under his leadership, the focus of the museum's work shifted to organizing temporary exhibitions. The space provided was used more effectively and the exhibitions were also shown in other museums in the GDR and abroad, but other aspects of the museum's work suffered due to the high workload and the inclusion of only a small part of the own collection. For example, the number of new acquisitions fell significantly. In February 1980 Jacobeit moved to the Humboldt University in Berlin as a professor . At this point in time, an exhibition concept developed with various cooperation partners took effect, which also led to a reorientation of the collection activities in order to do justice to the requirement of depicting the everyday culture of the workers. Among other things, students took part in the collection of relevant documents, and written and photographic documentation was created. This preparation should serve as a model for future museum work. Under the direction of the new director Erika Karasek (1934-), the exhibition Big City Proletariat - On the way of life of a class was opened in October 1980 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the State Museums. In this exhibition the museum did justice to the ideological demands made on it more than before. In the seven years of its running, the museum has seen more than a million visitors to the exhibition. In 1984 the magazine was rearranged to make room for the inventory to be expanded. In addition, the creation of photo documentation has now been systematically focused on. Since larger rooms could only be expected after the reconstruction of the Museum Island was completed, the aim was to continue to present individual areas of the collection in longer-running presentations similar to the exhibition on the Big City Proletariat. For example, for the 100th anniversary of the Museum of Folklore, the exhibition Clothing between traditional costume and fashion was set up, in which both the history of the collection and various aspects of clothing culture were presented.

Development in West Berlin

In West Berlin , the history of the museum did not continue until 1959, when the 40 boxes with 3580 objects that had been moved from their relocation sites in Thuringia to Wiesbaden were returned. The management of the museum was taken over by Lothar Pretzell (1909–1993), who was an expert on the confiscation of Jewish property during the Nazi era and who had headed the Salzburg Museum Carolino-Augusteum during World War II . Initially the collection was attached to the Museum für Völkerkunde , in 1963 the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde was founded as part of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The museum was assigned storage rooms on the former barracks area on Gardeschützenweg in Berlin-Lichterfelde . The museum in Lichterfelde did not have any suitable exhibition rooms. During his directorate, Pretzell was only able to go public with two exhibitions, Folk Art and Crafts in 1964 and Precious Folk Goods in 1967. In these exhibitions he presented his additions to the collection, most of which could be assigned to folk art. Overall, Pretzel was able to expand the collection again from around 3,500 objects when he took office to over 20,000 objects when he retired in 1974.

Theodor Kohlmann (1932-2011) followed Pretzell as director. As early as 1968, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation decided to rebuild the storage building of the Secret State Archives in Berlin-Dahlem , which had been destroyed during the war, and to use it as a building for the Museum of German Folklore. The move took place in 1974 and the permanent exhibition was opened to the public in April 1976. In this, on over 2000 square meters in 74 exhibition units, the domestic situation and working life of the pre-industrial and early industrial times in rural areas were presented. The special exhibition area also made it possible to present further holdings of the museum at regular intervals. In the 1970s and 1980s, the museum's collection strategy increasingly developed in the direction of everyday culture in rural and increasingly urban areas. The exhibition Servant Spirits. The life and working world of urban servants from 1981 was considered an important signal. As with the sister museum in East Berlin, however, the claim of the collection policy to also focus on current dynamics was ultimately only partially fulfilled.

Cooperation between East and West as well as between the ethnographic and folklore collections

Until the beginning of the 1960s, necessary connections existed between the folklore collections in East and West Berlin for reasons of work. With the following personnel changes, however, they slackened more and more, especially since there was a ministerial directive prohibiting the employees of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin in the east from contacting institutions of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in the west. As a result, both collections developed largely independently, knowledge of the respective processes on the other side of the Berlin Wall was only available in the context of private contacts and by following the reporting. Contacts were only resumed in October 1989 on the occasion of the museum's centenary, which the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde and the Museum für Volkskunde celebrated with exhibitions and conferences. In November 1989, for example, the international conference on everyday history in ethnographic museums took place in the Museum of Folklore on Museum Island . Opportunities for collection and presentation in international comparison took place, in which scientists from the Federal Republic also took part and which enabled an exchange across the fallen iron curtain. The event reacted dynamically to the changing conditions in the context of the wall that had fallen a few days earlier .

In the course of the 1980s, an increasing cooperation developed in Berlin-Dahlem between the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde and the Europe Department at the Museum für Völkerkunde. They organized joint conferences and exhibitions. Among other things, the show White Vests, Red Robes , shown in 1983/84 , in which European folk costumes were presented in the overall context of costume development with regard to the development of their colors and their meaning, emerged from this cooperation. It was one of the most successful exhibitions of the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde with both a high audience response and a positive reception.

Folklore Museum at the National Museums in Berlin / Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (1990–1999)

As a result of German reunification , the two folklore collections of the State Museums were merged in 1992 under the aegis of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation with continuity of staff. Kohlmann remained director, while Karasek became his deputy in her function as director of the former East Berlin museum. When Kohlmann retired in 1994, the director's position could not be advertised because the Berlin State Museums had to cut posts. Therefore Karasek followed him as his deputy. The name change from the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde to the Museum für Volkskunde in the course of the merger of the two institutions referred to the changes in content and concept that were initiated in the early 1990s. In addition, efforts were made to merge with the Europe department of the Museum of Ethnology to create a museum of European ethnology. In addition to the conceptual work on aligning such a museum to conferences and in publications, special exhibitions such as tartan skirt and lederhosen. European neighbors in symbols and clichés in 1994 tried out ideas for presentations from the holdings of both institutions. After the question raised by Karasek at a conference in Stuttgart in 1992 as to whether museums for European ethnology would be a perspective for the future and initial conceptual considerations for such a museum met with some controversial reactions, the 11th conference of the cultural history museums working group took place in the German Society for Folklore in Berlin on the subject of ways to Europe. Approaches and problem areas take place in the museums . At this point in time, the merger with the Europe department of the Völkerkundemuseum as part of the restructuring of the National Museums in Berlin had already been decided and the waterworks at Müggelsee in Berlin-Friedrichshagen , which had housed the Museum for the History of Water Management, was discussed as a possible location. International participants who were familiar with similar European-oriented projects in other European countries broadened their perspectives. However, the conference also met with criticism from within German folklore.

Museum of European Cultures (since 1999)

In 1999 the Museum of European Cultures was founded as a merger of the Museum of Folklore and the Europe Department of the Ethnological Museum. A new building for the museum had not yet been found at this point. So it happened with the exhibition Fascination Image. Cultural contacts in Europe will continue to be made public for the first time at its provisional location in the magazine wing of the Secret State Archives. This exhibition was received positively as the beginning of a new type of cultural history museum with a European focus.

With the establishment of the new institution, which Erika Karasek had worked towards for years, it went into retirement. It was followed by Konrad Vanja after as director. The question of the premises was clarified under his leadership: The Bruno-Paul-Bau at Arnimallee 25, the oldest building in the Dahlem Museum Quarter , was designated as the new museum building . There was 2005 with Zero Hour. ÜberLeben showed the first exhibition in the provisionally prepared premises in 1945 . The administration, workshops and some magazines remained in the warehouse building of the Secret State Archives. After a two-year renovation, the permanent collection presentation Kulturkontakte opened in 2011 . Life in Europe . Vanja was retired at the end of the following year. His successor was Elisabeth Tietmeyer at the beginning of 2013 , after she had been Vanja's deputy since 2002 and had co-curated the new permanent collection presentation. Since the Museum of European Cultures remained the only institution in the Dahlem museum complex after the Museum of Asian Art and the Ethnological Museum, both of which will move to the Humboldt Forum in the center of Berlin, were closed, Tietmeyer, as director, tried to reposition her house: Zum On the one hand, a new corporate identity was created that should attract more attention with the use of the color red and the acronym MEK , on the other hand it promotes networking with other museums and exhibition houses in the Berlin district of Steglitz-Zehlendorf.

collection

Outline of the history of the collection

The forerunner institutions of the museum were dedicated to the everyday culture of the lower and middle social classes and viewed the objects in particular as evidence of past rural life. Ulrich Jahn's first collection system from 1889 comprised the seven main groups of apartment, household and household items, clothing, food, art and trade, trade and traffic, as well as popular usage and belief. It was based on the experience of collecting trips to areas that were dominated by the farming economy and fishing. The area of domestic industrial production, which was particularly influential in the German low mountain range, as well as guild equipment , of which Jacobsen had only acquired a small number in Bavaria, were missing. Costumes and equipment from industrial production influenced by fashion were explicitly excluded. One of the most important acquisitions of the museum before the turn of the century took place in 1899, when Hermann Sökeland the Hindeloopener room with costumes that the existence of the Hindeloopener Museum had heard from the legate of the ethnologist Wilhelm Joest . This purchase represented one of the few additions to the collection that went beyond the borders of the German-speaking area and was related to Virchow and Jahn's great interest in the Frisians .

In the early years of the museum, the focus was equally on traditional costumes and equipment, but the focus was increasingly on the former: in 1908 there were 300 traditional costumes in the collection, making the museum the most important collection of costumes in Germany alongside the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg. Devices that were less of a focus of interest due to the space-consuming presentation in rows and groups, were increasingly collected on the basis of external suggestions: Virchow emphasized that simple devices should be more strongly represented in contrast to the richly decorated devices that were in the collection, which are numerous The opening of the Austrian Folklore Museum in 1897 gave renewed impetus to set up the devices in rows and groups, but this was not implemented until 1908 when the collection was re-presented in the Palais Creutz. In his role as temporary director of the museum, Sökeland collected equipment for the manufacture of wooden shoes and flax processing in his home town of Westphalia in 1904 and documented the respective work processes. Under the direction of Karl Brunner , several larger collections were acquired, so that the character of the museum collection changed. In 1906 the museum association bought the collection on folk culture of the Austrian Innviertel from the painter Hugo von Preen , which significantly expanded the museum's inventory of tools and equipment. Overall, the focus of the collection shifted in the direction of folklore and customs. In his function as the person responsible for the association, Sönkerland arranged multiple donations of votives , amulets , mementos and offerings from the collection of Marie Andree-Eysn from Salzburg . In 1910, her collection of votive tablets from Bavaria and Austria, comprising 1,200 pictures, came to Berlin, although she had also considered donating the Viennese collection. In 1909, on the occasion of the folk art exhibition in the Wertheim department store, an Upper Bavarian wedding or chamber car with an inventory of painted furniture from 1785 was acquired, which was a highlight of the collection. The acquisition of guild equipment from the collection of German guild antiquities compiled by Artur Hazelius for the Nordic Museum in Stockholm was also important. From 1910 onwards, a collection of models from various German farmhouses was started, based on 24 models and the new copies of which were financed by James Simon. By the outbreak of World War I, 13 new models were added to the ten old models in the collection.

- Anonymous, illustrations from the guide through the collection for German folklore. Klosterstrasse 36 , 1914

This early focus on collection efforts continued through the Weimar Republic and National Socialism. With the establishment of the State Museum for German Folklore in 1935 and the establishment of the Europe Department at the Museum for Ethnology at around the same time, there was a change in orientation: the exchange of objects between the two institutions resulted in a sharper separation of a folklore collection focused on the German-speaking area on the one hand and an ethnographic collection with a special focus on Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Many of the objects collected before 1945 lack comprehensive documentation of their provenance , particularly due to the loss of files in the Second World War . For some objects, the persecution-related withdrawal by the National Socialists cannot be ruled out, and there were occasional restitutions .

After the Second World War, the two folklore museums in divided Berlin followed the lines of tradition from the 19th century when rebuilding their respective collections. While the East Berlin Museum was able to undertake collection campaigns in the GDR, the West Berlin colleagues, due to their isolated location, were primarily dependent on acquisitions from the antique trade and flea markets as well as from collectors. In the 1980s, the museums turned more to everyday life and the world of the industrial age up to the present, but the claim of collecting today could only be met in some areas such as children's books , collector's pictures and the school system. The Europe department at the Völkerkundemuseum also pursued its traditional, cultural-regional pattern of collecting with a focus on traditional costumes, ceramics and household and economic utensils used by the rural population from southern and central-eastern Europe.

The founding of the Museum of European Cultures in 1999 was accompanied by a reorientation of the collection practice. The motivation to preserve and document a living environment in the process of disappearing finally faded into the background; instead, the museum takes a decidedly contemporary perspective. For this reason, the Museum of European Cultures began to increasingly include objects in its collection that can be assigned to the subject areas of cultural contacts, migration, and sexual and gender diversity. At the same time, the practice of participatory and multi-perspective collecting, which is in accordance with the ethical guidelines for museums of the International Council of Museums with its emphasis on close cooperation with the source communities, replaced the collecting trips of private collectors, which shaped the development of collections over a long period of time had. The historical collection was also asked about the new thematic focus. The guiding principle for the Museum of European Cultures is an open concept of Europe that tries to take account of geographical, political, historical and emotional dimensions.

There are three focal points for the further development of the collection: Firstly, the documentation of processes of identity formation, on the one hand via objects that express self-chosen identities, on the other hand via those that reveal external attributions. For example, a flag was added in 2019 that combines the Sami flag with the rainbow flag and thus represents the identity of people who see themselves as Sami and queer at the same time . Second, the documentation of Europe in the world through objects that show the reception of the material and immaterial cultural heritage of Europe in other parts of the world. One perspective is formed by European migrants such as Italians who have settled in the USA, and their relationship to the culture of origin and any associated essentialization processes. Thirdly, the documentation of questions of sustainability and the relationship between culture and nature. On the one hand, new objects are included in this context, on the other hand, the old collection is questioned with regard to current problems, for example when strategies of sustainability are legitimized with references to a given or supposed tradition. In addition, stock gaps are to be closed. The birth control pill has not yet been documented in the collection of the Museum of European Cultures, although modern contraceptives have had a major impact on everyday life in Europe. There is also a focus on the documentation of intangible cultural heritage, for example through the documentation of manufacturing processes and interviews with contemporary witnesses who make references to objects in the collection. These arise either in the context of field research in preparation for exhibitions or research projects.

Collection holdings

With around 285,000 ethnographics and objects on cultural history, the Museum of European Cultures has one of the largest collections on everyday culture and popular art in Europe. This is material and immaterial cultural heritage mainly from Germany and other countries with a focus on Eastern and Southeastern Europe. The holdings of textiles, popular graphics and photographs as well as the thematic collections on naive art , rituals and forms of religiosity as well as childhood and youth culture are significant . The historical collections of some ethnic minorities in Europe, especially the Sami and Crimean Tatars, are unique . The eventful history of the museum with its various predecessor institutions is reflected in the system, which is reflected in the old holdings, the holdings of the museums from East and West Berlin and the Europe department of the Ethnological Museum as well as the new additions to the reunited museum since 1992 and then to the Museum Europäische Cultures. In the beginning, the structure according to cultural landscapes played the decisive role, but when it was founded as an independent museum in 1935, a system based on materials and subject groups was introduced, which the Museum of European Cultures continues. The museum therefore arranges its holdings in 74 subject groups with various subgroups, which mainly refer to contexts of use. The stocks are deposited at various storage locations, with the material being the primary criterion for allocation.

Significant stock groups

Significant groups in the Museum of European Cultures are work and profession , house and living , religion, belief and ritual , toys , clothing and jewelry , photography , everyday print products and popular imagery .

The stock group work and occupation belonged to the primary collection area of the museum for German folk costumes and products of the house trade. Initially folk artistic crafted objects were particularly ornate, collected and, increasingly, evidence of were guilds organized craftsmanship such as guild certificates and trophies included in the collection. From the 1970s onwards, entire workshops and ensembles were increasingly integrated into the collection. The Museum of European Cultures, for example, has a violin maker , blueprint and shoemaker workshop as well as a grocery store . The historical collection will continue to be supplemented in individual cases, the focus of the collecting activity is on conveying cultural techniques as intangible cultural heritage. For example, when a Polish turning star was acquired in 2018, its production was documented on film.

House and living has also been a central group from the earliest phase of the collection. It includes furniture, household appliances, ceramics and dishes. The collection includes entire room furnishings from rural areas of Germany and Europe from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. In addition, furniture from various social classes was documented. Household appliances were collected from different regions of Europe. The ceramics inventory includes Westerwald stoneware , Siegburg stoneware , Bunzlau ceramics and a wide variety of ceramics from the Iberian peninsula. The collection also includes porcelain and tableware made from other materials such as tinplate and plastic. While stock gaps are to be closed in the area of everyday tableware and current developments such as the EU Parliament's ban on single-use plastic products in December 2018 with the addition of a coffee-to-go cup to the collection, furniture should only be documented in individual cases can be acquired.

Pastry model for Springerle with the motif Landsknecht / ensign on horseback with flag, 1614, Bavaria.

Tuchglatscher / Plättscher to pat the finished laundry smooth, 1871, Gungelshausen .

Stollen cabinet with the inscription "Hope only to God's goodness. It brings you blessings in the middle. In the year Christy Anno 1774", 1774, Großhennersdorf .

The holdings of religion, belief and ritual are shaped by a large collection of Christian votives from different parts of Europe and sculptures with themes from Christian iconography . This stock group also includes ritual objects and secular objects from the curriculum vitae such as baptismal certificates , confirmation certificates and bridal crowns . Objects related to the course of the year such as Easter eggs , Advent calendars and Christmas decorations are also part of the collection. The two special collections by Marie Andree-Eysn and Gertrud Weinhold are important for this stock group. For example, the vast majority of Christmas cribs and crib figures come from the latter . In addition to Christianity, objects from other religions such as Judaism and Islam are also represented in the collection, but in significantly fewer numbers. Two examples of the latter are an electronic prayer chain or the first Ramadan calendar from 2010, which, as a modification of the Advent calendar, represented a leap in development in an already existing object area and was therefore included in the collection and thus exemplarily illustrates the current collection policy.

Corpus Christi altar of the Heinzelmann family, wood, plaster, painted, 293 × 122 × 42 cm, Burladingen , 1920s.

Gerhard Goder, Conchita Wurst on the crescent moon , Swiss stone pine, 157 × 100 × 60 cm, 2014.

The toy collection of the Museum of European Cultures mainly comprises objects from the 19th and 20th centuries with a geographical focus on Germany and Poland. It includes card and board games , dolls and their accessories, dollhouses , rocking animals, vehicles, handicraft toys and construction sets as well as optical, mechanical and electronic toys. Examples of contemporary developments are depicted through additions to the collection.

The clothing and jewelry collection is one of the core collections of the Museum of European Cultures. The vast majority of the objects date from the 19th and 20th centuries and document the clothing behavior of the rural and rural areas as well as of the lower and middle classes of the urban population up to the 1970s, with the focus on everyday clothing. The Museum of European Cultures has the largest collection of costumes in Europe, which covers a broad regional spectrum. The jewelry collection, which had only a few war losses, complements the inventory and offers a representative overview of accessories for rural clothing. The Museum of European Cultures works primarily to fill gaps in stocks from the 1970s and to depict current phenomena such as the globalized fashion industry with its counter-movements such as ethical and slow fashion .

Stained carpet with representations from the Old and New Testament , 150 × 150 cm, Silesia, 1750-1800.

Maria Demski, knotted wedding carpet, 1800-1820, Lötzen .

The photographic collection of the Museum of European Cultures mainly includes ethnographic photographs, mostly by unknown photographers, which document everyday life. They cover the spectrum from studio photography to amateur photography; The collection also includes unique items such as daguerreotypes and ferrotypes . Significant are the photo holdings from Southeastern Europe as well as the holdings on Sami and Crimean Tatars. In addition, part of the image archive of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory is kept at the museum. Another important bundle is the photographic documentation of Muslim prisoners of war from two camps near Berlin during the First World War by Otto Stiehl . In recent decades, the museum's collection has shifted primarily to private photo albums and bundle of snapshots as well as photo-ethnographic projects by author photographers. The photographic holdings are supplemented by private and scientific cine films. The Museum of European Cultures sees the integration of digital everyday photography as well as the digitization and documentation of the old stock as a particular challenge of its photographic collection.

The inventory group of everyday printed products mainly includes cookery and school books , sample catalogs, maps and travel guides . There are also children's books and religious literature. The inventory also includes a wide variety of luxury paper , for example in the form of collector's pictures and paper dressing figures , as well as around 30,000 postcards and 1,000 posters . Documents such as official letters, ID cards , medals , invoices, receipts , savings books , family certificates , private letters and estates also belong to this inventory group .

All areas of popular printmaking and painting are represented in the inventory group Popular Imagery . Particularly noteworthy are the bundle of bench pictures and the collection of around 10,000 picture sheets . Furthermore, the Museum of European Cultures has products of traditional handicraft techniques and popular art from the fields of painting and sculpture. One focus is the naive art from Poland. Collecting in this area is limited to exemplary evidence of new developments. In 2016, for example, the museum acquired a graffiti by the Dutch street artist Laser .

Special collections

The Museum of European Cultures has a number of special collections that usually go back to collectors and form self-contained bundles that are no longer supplemented. The Andree-Eysn collection, with its religiously connoted objects, was a significant early addition to the museum and still makes up the majority of the stock of votives . The Gertrud Weinhold collection, The Gospel in the Apartments of the Nations, is also dedicated to the topic of religion . Ecumenical and comparative collection with its 15,000 objects. These objects mainly cover the 20th century in Germany and other European countries, especially Poland, supplemented by Christian objects from Africa and Latin America. The Weinhold Collection also includes numerous toys. With the Orth Collections, a bundle of over 1000 works compiled by the journalist Hans-Joachim Orth and his wife Christina, and the Hans-Joachim Schauß Collection , which includes over 250 sculptures, the Museum of European Cultures has a large collection of naive art from Poland. The collection of Rudolf Wissel , who, in addition to his work as a trade unionist and social democrat, was also a craft researcher, came to the West Berlin Museum in 1966 and comprises around 570 devices, tools and documents. The collection of folklorist Christa Pieske supplements the museum's holdings with wall art prints and luxury paper , while Wilhelm Kiesewetter's estate includes 162 paintings and twelve models that document his ethnographic journeys. In addition, the legacies of Planet Verlag , the largest publisher of printed matter in the GDR, produced wafers , cards, coloring books and magazines, and Volk & Welt, the second largest publisher for fiction and the most important publisher for international literature in the GDR Holdings of the museum.

Permanent collection presentation

The permanent collection presentation of cultural contacts. Life in Europe is divided into the three subject areas of encounters , borders and religiosity and presents on 700 square meters the forms and consequences of cultural contacts in Europe in a comparative way as well as a representative cross-section of the collection.

The first exhibition area, Encounters, is dedicated to the topics of trade, travel, media and migration. The dominant key object is a Venetian gondola , which refers to Venice as a place that unites many of the topics addressed in this section. The first themed island is dedicated to European trade relations using objects made of silk and glass beads . In the following themed island, the topic of travel is presented in particular with the presentation of souvenirs and a box with objects from various former Soviet republics, which Raisa Gorbacheva presented to the State Museums as a gift in 1986. A central object is the Carrettu sicilianu , built in 1904 , which Wilhelm II brought back from a trip to Sicily and which was installed in the Roman Baths in Sanssouci Park until 1937 . Used as a means of transport in the Mediterranean until the middle of the 19th century, these wagons are now exhibited in Sicily and used for pageants, while small replicas are sold to tourists. The following themed island deals with the topic of the media with a screen decorated with wafers and a paper theater with a backdrop cupboard and theater structure in which a scene from Jules Verne's The Journey Around the World is set up in 80 days . The final themed island of the Encounters section deals with the topic of migration through objects that refer to the influence of migrants and trade on the culture of food and drink . For example, the advertising figure of a doner kebab and utensils for preparing and selling doner kebabs are shown.

The topic of borders is dealt with in the second exhibition area. The first thematic island in this section is dedicated to objects from the field of clothing, customs, associations and marketing that are either typical of the area or represent places. These objects are closely related to people's identification with a place and their self-esteem. The second themed island is dedicated to the regional positioning of culture with masks and costumes . This topic is deepened in the third thematic island, which functions as an excursus, with photographs by Sabine von Bassewitz , which show self-representations of various groups from Germany. The fourth themed island is dedicated to the complex of national character , which is not reflected in the material culture of everyday life like regional culture, but is primarily communicated on a symbolic, visual, textual and musical level. On the one hand, pictorial representations of national stereotypes are shown, which in particular serve as a demarcation and are often used politically, and on the other hand, positive identification with one's own nation is addressed through the topic of sport. The topic section Borders will be concluded with the presentation of the 2010/11 commissioned work for women and men, The Europeans by Stephan Hann . The two costumes consist of different materials with a European reference and refer to traditional costumes. Artistically, the existence of a hybrid, decidedly European identity is questioned.

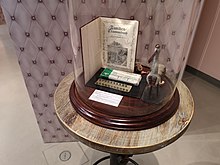

The third exhibition section is devoted to the topic of religiosity . The Christian religion, with its references to Judaism and Islam , is seen as particularly formative for Europe. The first theme island this exhibition area dedicated to the devotion in everyday life and shows, among other Votive, devotional images, Advent and Ramadan calendar and Fully equiped . The non-Christian religions are represented with Muslim prayer chains as well as menorah and kippah . This presentation particularly emphasizes the structuring influence of religion on everyday life. The second themed island is specifically dedicated to objects related to Christmas : Christmas cribs from Europe as well as Peru, Egypt and Tanzania enable a cross-cultural look beyond the borders of Europe, which refers to the relationship between Europe and the world. The complex of topics of religiosity is concluded in the basement with the presentation of the mechanical Christmas mountain in the oriental style by Max Vogel , which has been part of the collection of the Museum of European Cultures since 1999 and is the largest Christmas mountain outside the Ore Mountains.

Paper theater with backdrop cabinet and theater structure, 1890-1900.

Mechanical Christmas mountain in the oriental style by Max Vogel , started around 1885.

Events

Exhibition profile

The exhibition profile of the Museum of European Cultures and its predecessor institutions reflected the respective status and orientation of the institution. The museum for German folk costumes and domestic products, with its precarious spatial location and lack of institutional integration, took part in exhibitions such as the German Exhibition in London in 1891, the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the Berlin Trade Exhibition in 1896 in order to gain attention and status for itself to generate. This situation hardly changed beyond the integration into the Royal Museums in Berlin in 1904 and the First World War until the late Weimar Republic: In October 1929, the Collection for German Folklore organized jointly with the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the Association of German Folklore Associations an exhibition in the premises of the Akademie der Künste on Pariser Platz , the purpose of which was also to generate attention, especially for the need for sufficient space for the collection.

A change began with the changed spatial conditions of the State Museum for German Folklore after 1935. In particular, Adolf Reichwein , who was in charge of the school and museum department, prepared individual groups of materials for museum education with his school exhibitions and presented them to a younger audience. The two folklore museums in West and East Berlin relied on temporary exhibitions from the 1960s to the 1980s, precisely because of their spatial restrictions, in order to make the breadth of the holdings accessible to the public. Special exhibitions such as Big City Proletariat - On the Way of Life of a Class of the Museum of Folklore on Museum Island 1980 and Servant Spirits The life and working world of urban servants at the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde in Berlin-Dahlem from 1981 marked the development of the museums away from the focus on the traditional rural way of life towards a focus on the everyday culture of rural and increasingly urban areas. In West Berlin, for example, in 1983/84 with the exhibition White West, Red Robes, the 1983/84 first cooperation between the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde and the Europe Department of the Museum für Völkerkunde, which increasingly looked beyond the German-speaking area income and formed the basis for the later unification of both collections. This development continued after reunification in the 1990s. With exhibitions like tartan skirt and lederhosen. European Neighbors in Symbols and Clichés In 1994, possible presentation methods for the future Museum of European Cultures were tried out.