Erin colliery

| Erin colliery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

| Headframe of shaft 7 | |||

| Mining technology | Underground mining | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Start of operation | 1867 | ||

| End of operation | 1983 | ||

| Successor use | Technology and business park, green spaces | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Hard coal | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 51 ° 32 '47.6 " N , 7 ° 18' 17.2" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Castrop | ||

| local community | Castrop-Rauxel | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Recklinghausen | ||

| country | State of North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

| District | Ruhr area | ||

The bill Erin was a coal - mine in Castrop-Rauxel .

history

1866 to 1900

1858 consolidated the Irish mining entrepreneur William Thomas Mulvany several pit field possessions in the area of Castrop . As a reminder of its homeland, the new pit field was given the name of the goddess Erin , a form of the Gaelic name Eire , which stands for Ireland .

Under capital acquisition by the Prussian mining and metallurgical AG Mulvany began with the sinking of the shafts 1 and 2 at Charles Street in Castrop. Coal mining began as early as 1867. The design and expansion of the mine was carried out according to standards that were adopted from the Anglo-Saxon coal mining industry . Shafts 1 and 2 were only 20 m apart. As was customary on some British collieries at the time, a common machine house could be built between the shafts and the cable guide could be diverted into the shaft via two arms from the gable ends of this house. In 1870, a coking plant with beehive ovens was put into operation on the mine .

In the following years there were several firedamp explosions with fatalities, and severe water ingresses repeatedly led to business interruptions, which considerably weakened the operating company's capital base. In 1877 the Prussian Mining and Hütten AG filed for bankruptcy . The Erin colliery was only kept open temporarily and only produced coal for its own use.

From this fact, it is explained that the bill Erin as the others founded by Mulvany mines not Hibernia and Shamrock in establishing the Hibernia AG was included as a mining company.

In 1882, Friedrich Grillo founded a new Erin union . This union invested extensively in the drowned mine workings and swamped them with success. In 1887 the Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks-AG (GBAG) acquired the Erin mine and coking plant . In the following years the coking plant was replaced by a new building. The conveyor system for shafts 1 and 2 was replaced by a construction that is unique in the Ruhr area : two small German strut frames , which were connected by a gangway, were erected as " Siamese twins " over the shafts.

Between 1889 and 1891 the Erin 3 shaft was sunk east of shafts 1 and 2 as a cable car and weather shaft and put into operation. This also significantly reduced the risk of firedamp. First an iron headframe was erected over this shaft. The subsidy has now increased considerably, bringing GBAG to first place among the German coke-producing companies.

For improvement of the weather guiding and concentration of the promotion on pit 1/2 was drilled 1890 as pure air shaft shaft 4-1892 beside pit 1/2. In addition, Erin 5 shaft was sunk in the northeast field from 1892 to 1895 as a further pure weather shaft .

1900 to 1953

From 1905, Shaft 3 was temporarily operated as a separate conveyor system. From this shaft the independent device of the northeast field was made. Shaft 5 was continued as a weather shaft for conveyor shaft 3. Due to the lack of processing facilities on shaft 3 , the coal extracted was forwarded to shaft 1/2/4 by horse-drawn trams . In 1908, shaft 3 was sunk to the fourth level - 498 m ( 380 m below sea level ). In 1909, shaft 2 received a new headframe, followed by hoisting cages with 4 levels for 2 cars each and a new hoisting machine . In 1912, shaft 1 received a new headframe and the hoisting machine was converted from a drum to a Koepe conveyor system. In 1913 the record annual output of 625,560 tons was achieved with 2,475 employees . In 1914, shaft 1 reached the fourth level at -457 m ( 387.7 m below sea level ). In 1915 the coking plant reported a record production of 210,000 tons. In 1919 it fell to 55,845 t due to the recession. 1921 bay 5 became the fourth sole drilled.

From April 1923 to July of the same year Erin was under French occupation (passive resistance). With 3,272 employees, an annual production of only 188,930 tons was achieved. Bit by bit , pit fields were swapped with the neighboring plants. When the United Steel Works AG was established in 1926, mining in the area around Castrop and Sodingen was reorganized. The Teutoburgia colliery in Herne , which was closed in 1925 , was connected to the Erin 1/2/4 mine . Teutoburgia 1 shaft was still used as a cable car shaft, Teutoburgia 2 shaft only served as a weather shaft from 1934 onwards. In 1929 a hammer head winding tower was erected above shaft 3 , which originally stood above shaft 2 of the United Westphalia colliery in Dortmund . A year later the coking plant of the Erin 1/2/4 mine was replaced by a modern new building.

In 1937 the production in shaft Erin 3 was stopped because it was planned to expand shaft 1/2/4 into a central conveyor system. The production reached one million tons of fat and gas coal per year. To further expand the colliery, work began in 1943 to optimize the weather management in the western field. The Erin 6 weather shaft that was started for this purpose had to be deferred due to the ongoing war events.

The mine was badly damaged in a bombing raid on January 3, 1945 and production was stopped on February 27. After another attack, coke production had to be stopped on March 13th. Shortly after the occupation by American troops on August 8/9. April the colliery came under British administration. While production was resumed on April 19, coke production began on October 11, 1945 with the start-up of batteries 1 and 3. It was not until 1951 that all war damage was removed. Shaft 6 was completed between 1948 and 1951.

The Erin colliery was continued under its own operating company from 1951. This was a wholly owned subsidiary of GBAG. From 1951 to 1953 the new main shaft 7 was sunk at the shaft system 1/2/4. This received a full-walled headframe of the Dörnen type and was supposed to take over the central product and material conveyance function.

1953 to 1983

From 1956 the Erin colliery was run by the Dortmund mining company. Up to 1962, shafts 1 and 2 were gradually taken out of production. The twin frame Erin 1/2 was gradually replaced by a smaller facility. From then on, the shafts were only operated as weather shafts.

In 1966 the Erin colliery implemented rationalization measures, above all an increasing automation of the longwall mining operations .

In 1967 the sale of the coal mine Erin at the Eschweiler mine association (EBV), which at this time some mines in Herne and Castroper area acquired (see Fig. Colliery Lorraine , bill count Schwerin ).

Under the leadership of the EBV, the Erin colliery was allocated reserve fields from Lorraine and Graf Schwerin . The Lothringen 6 shaft was adopted as a weather shaft.

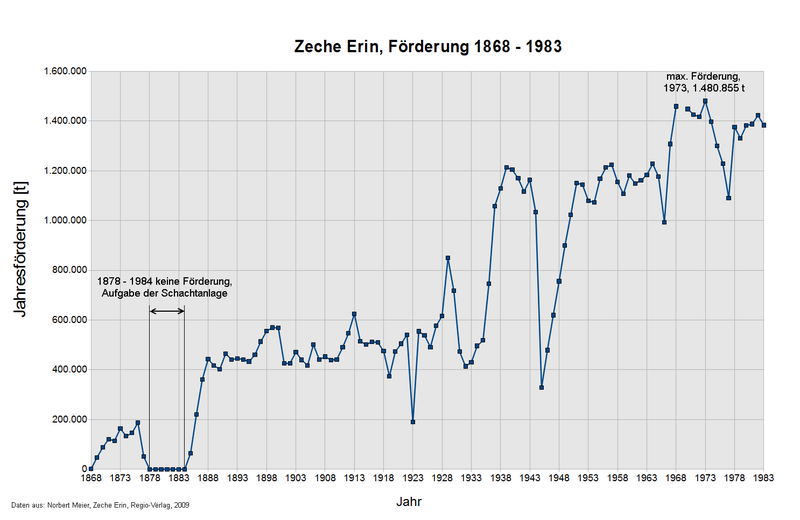

Operating figures

The highest annual output was achieved in 1973 with 1,480,855 t. In 1957, coke production peaked at 832,330 t. Likewise the workforce with 4,799 employees.

The logarithmic representation of the key operating figures clearly shows the unchanged high level of mining and coke production during the Second World War up to 1944, as well as the 1945 slump due to the destruction of the war. Likewise, the decline in production in 1923 due to the passive resistance of the miners during the occupation of the Ruhr area by French and Belgian troops.

Location of the shafts

- Bay 1: 51 ° 32 ′ 48.7 " N , 7 ° 18 ′ 16.68" E

- Bay 2: 51 ° 32 ′ 48.2 " N , 7 ° 18 ′ 16.7" E

- Bay 3: 51 ° 33 ′ 0.7 ″ N , 7 ° 19 ′ 42.2 ″ E

- Weather well 4: 51 ° 32 ′ 47.88 ″ N , 7 ° 18 ′ 14.32 ″ E

- Weather well 5: 51 ° 33 ′ 36.7 ″ N , 7 ° 19 ′ 17.8 ″ E

- Weather well 6: 51 ° 31 ′ 58.8 ″ N , 7 ° 17 ′ 53.9 ″ E

- Bay 7: 51 ° 32 ′ 47.56 " N , 7 ° 18 ′ 17.17" E

Shutdown

The sudden onset of the sales crisis from 1982 onwards led EBV to decide to gradually withdraw from the mining business. The Erin colliery , which after almost 120 years of mining activity no longer had sufficient capacity reserves, was committed to shutdown.

On December 23, 1983 the production operation was shut down. The coking plant was extinguished in 1984. With the closure, the first and last mining colliery Castrop-Rauxels ended the era of hard coal mining in the city.

Current condition

The shafts were filled . The winding towers above shaft 7 and shaft 3 have been preserved as industrial monuments . They tell (partially illuminated) of the great mining past of the city of Castrop-Rauxel .

On the site of the Erin 1/2/4/7 colliery, a technology and industrial park has been created in some old outbuildings and on the open spaces of the former coking plant.

The former weather and cable car shaft Erin 3 is one of the oldest surviving towers of its kind. It is technologically significant and a testament to the economic history of the city. In memory of the Irish founder William Thomas Mulvany , a Celtic tree circle was built around this winding tower . The circle is supposedly based on a mythical "tree calendar" of the Celts, but is based on a modern invention.

In 1902, a miner's house was built next to the Hammerkopfturm . Its size, the architectural effort and the representative details reflect the upscale colliery housing.

Both are part of the Route of Industrial Culture .

Individual evidence

- ^ Norbert Meier: Erin colliery. Regio-Verlag, Werne, 2009, p. 58

literature

- Wilhelm Hermann, Gertrude Hermann: The old mines on the Ruhr . 6th expanded and updated edition. Verlag Karl Robert Langewiesche, successor to Hans Köster KG, Königstein i. Taunus 2008, ISBN 978-3-7845-6994-9 .

- Norbert Meier: Erin colliery: the story of an extraordinary mine . Ed .: Friends of Mining Historic Sites Ruhrrevier e. V. 1st edition. Regio-Verlag, Werne 2009, ISBN 978-3-929158-23-6 .

- Joachim Huske: The coal mines in the Ruhr area. 3rd edition, self-published by the German Mining Museum, Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-937203-24-9 .

- North Rhine-Westphalia Foundation (ed.). Erin memories. The restoration work on the Erin winding towers, Teutoburgia, Hammerkopfturm, main shaft 7. Druckerei Goergens und Lesaar GmbH, Düsseldorf.

Web links

- Description of this sight on the Route of Industrial Heritage (Erin 3)

- Description of this sight on the Route of Industrial Heritage (Erin 7)

- metropoleruhr.de: Hammerkopf tower with a Celtic tree circle and mountain officials' house

- Pictures of the Erin colliery from 1984