Eisenheim settlement

The Eisenheim settlement in Oberhausen is considered to be the oldest workers 'settlement in the Ruhr area and one of the oldest surviving workers' settlements in Germany. Eisenheim is the first German workers' settlement to be listed as a historical monument .

The first houses on the approximately seven hectare area were built in 1846, built by the later Gutehoffnungshütte (GHH), initially for their ironworkers . It was not until the second expansion stage that miners from the Osterfeld colliery were added after 1865 . At the turn of the century, around 1200 people lived in 51 one-and-a-half and two-story houses.

After partial destruction in the Second World War, plans arose to demolish the "ugly old buildings", to replace the settlement completely with new buildings and thus to " wipe out the colony era." The social structures that had evolved within the settlement were not taken into account. The resistance of the local residents was supported in the early 1970s by a Bielefeld student group led by Roland Günter . The first workers' initiative was founded in the Ruhr area, which was to become a model and incentive for many other such initiatives in the region. After a long struggle, the remaining 38 houses were saved from demolition and placed under monument protection in 1972. The sociological studies that were carried out in this context are among the “classics of social science of the 1970s” and were instrumental in the “ paradigm shift towards a public that was more oriented towards the social effects of architecture and urban planning”.

With the Museum Eisenheim in Berliner Straße, the estate has a branch of the LVR Industrial Museum in Oberhausen . The “Talking Streets - Talking Monuments” project enables the history of the settlement and that of its residents to be traced on a walk through the settlement.

Today the settlement, which also became famous through the multi-part WDR television series Die Helden von Eisenheim , is part of the Route of Industrial Culture .

history

Company housing, which initially went back to state initiatives, took place in Germany as early as the 18th century, first for farm workers and later for miners. The first example of private housing construction was a three-story workers' apartment block at the Cromford textile factory in Ratingen .

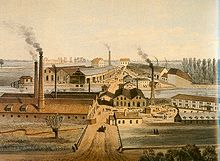

The impetus for founding Eisenheim was the onset of the railway boom at the end of the 1830s . The steelworks union Jacobi , Haniel & Huyssen (JHH), the forerunner of Gutehoffnungshütte (GHH), shifted its production focus from the production of pig iron to iron processing and produced the first rails in the region. Foreign specialists were also required for the new production processes introduced from abroad. The director of the JHH Hermann Wilhelm Lueg had the idea not only to poach foreign masters, but also to offer them attractive opportunities to settle.

The YHH had been building company housing around Sterkrade since the 1820s , but Eisenheim had been the oldest surviving settlement complex in the Ruhr area since the turn of the century. With its sixty years of construction from 1846 to 1903, it reflects the building history of housing developments in the Ruhr area in a unique way based on the various house types.

First expansion phase in 1846

On February 27, 1830, Lueg stated in connection with the expansion of the rolling mill: "Since the increased number of factory workers are lacking apartments, we want to build a large residential building for several working-class families." It was not yet clear where this should happen. In 1834 he negotiated with the mayor of Holten about the construction of 15 workers' apartments, which could not be built due to an economic downturn.

On February 8, 1844, Lueg bought 27 acres , 139 rods and 60 feet of land from the farmer Theodor Rübbekamp in the Ravelkamp and Wesselkamp districts for 2350 thalers. The location was on the Provinzialstrasse from Mülheim an der Ruhr to Dorsten , which was then being expanded as an art route. It connected the Gute Hope hut in Sterkrade with the puddling and rolling mill on the Emscher . The properties were on slightly swampy, often flooded farmland, far from the factories and other residential areas of the time. In addition to the low property prices, the planned settlement of strangers and foreigners was responsible for the choice of the remote location, as this fact was viewed with suspicion by the local rural population.

The entry in the land register dragged on for two years after the land was bought, as the landowner's approval was missing. The building application to the Osterfeld community, which was only formed in 1841, was rejected by them.

“I submitted your application for a building permit in the Osterfeld community to the community assembly in accordance with legal regulations. The same found doubts about admitting the building for their part, fearing that the building would be inhabited by many strangers and that such strangers would become an unaffordable burden in the event of illness and impoverishment of the small community. However, she does not want to withhold her consent if the union [the JHH] orders legal security for such cases. "

With the involvement of the Ministry of the Interior of the district government in Münster and the district administrator, Lueg obtained a provisional building permit. On April 6th the mayor announced that the construction work had started, on August 28th the YHH announced that seven houses would be completed in 14 days and they applied to name the settlement "Eisenheim".

"[...] we ask very much [...] that the small village that we have started to form in the Osterfeld community on the field of Wesselkamp is given the name" Eisenheim ".

It is not our intention that the colony should form a special community, but it may at least remain a peasantry or a department of the Osterfeld community.

We only want a special name so that we can overlook business communications from future residents of this colony more quickly that it concerns the colony.

Since maybe 50 families will live there in the future, this branch deserves a special name.

The next village, Osterfeld, in whose municipality the building site is located, is half an hour away and there is no connection with houses. Without an official name being given, people would in future invent names to designate the place more precisely, because Osterfeld cannot be said for once and could give rise to errors and confusion.

So we ask you to endorse the name "Eisenheim" and recommend us with great devotion. "

Tourneau again did not comply with the request and referred to the government. When the first tenants had already moved in, the royal government in Münster approved the naming and the building application on January 6, 1847.

“The union of the Gute-Hoffnungs-Hütte zu Sterkrath [sic] has been granted permission with a higher permit to build 32 acres of land in the community of Osterfeld, Recklinghausen district, the so-called Weselkamp, and located in the village farmers' union , Corridor 1 No. 385/315, the name "Eisenheim" to be used. "

The problems with the distribution of social burdens through such settlements were only clarified in 1876 by the Prussian Settlement Act, which regulated the question of the risk of support in favor of the communities.

The English traveler TC Banfield described Eisenheim - the Masters' Houses on Provinzialstrasse - in the summer of 1846 as follows:

“On the way, our host took us past some houses (cottages) that the company had built for the workers according to an appealing plan. The houses, of which only one row had been built, although a large rectangle had been planned, stood together in twos, in gardens that separated them from the provincial road. Between each group of two there was a pump used by the houses; in between there was a path leading to the land behind the houses. This land should belong to every house in strips the size of a Prussian morning "

Due to the discussion about the social follow-up costs, Lueg changed the type and property characteristics of the planned houses several times in his applications. First of all, he announced a house "for capable masters and workers of the right kind". Then in March 1846 he applied for the "construction of barracks-like apartments ". Initially, Lueg had planned to sell the houses to the users on the basis of a premium house system, as was common in the Saarland mining industry. The loan rewards should be deducted directly from wages. But then he decided on a rental basis. The two tenement houses were consequently built.

Most recently, a total of eleven residential buildings were built: first in the spring of 1846 seven master houses along Provinzialstrasse (today Sterkrader Strasse), followed in late summer and autumn by the semi-detached house in Kasernenstrasse (today Fuldastrasse No. 5-7) and two two-story residential buildings on Communalweg (today Wesselkampstrasse No. . 27/29 and 31/33).

In 1848 around 128 people in 30 families lived in the settlement. They came from Saarland, the Palatinate, the Bergisches Land and the Prussian eastern provinces as well as neighboring countries, some also came from the neighborhood. They were mostly Catholics. The residents were not only masters, but also foremen and skilled workers , simple workers and day laborers . Most of them worked in the half an hour's walk on the Emscher, which was then still flowing further south.

Second expansion stage 1865/66

The second expansion stage was associated with a long-lasting economic upturn. From 1842 to 1865 the workforce of the metallurgical union had increased from 2000 to almost 5000. Gutehoffnungshütte AG (GHH), formed in 1873, was able to get back into pig iron production by smelting local ores with coke at the Friedrich Wilhelms-Hütte in Mülheim. Both ironworks I and the Neu-Oberhausen rolling mill were built. The development turned into a start-up boom .

From 1865 ten more residential buildings were built, seven in Berliner Straße (No. 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20) and two in Wesselkampstraße (No. 19/21 and 23/25).

Third expansion phase in 1872

The single settlement house built in 1872 (Wesselkampstrasse No. 35) represents a revolutionary innovation. There is no earlier evidence for this type, so it can be assumed that it was developed by an unknown planner in the GHH. The cross ground plan was modified so that the apartments and the entrances were relocated to the respective house sides. Each of the four families had their own private area outside and could almost indulge in the illusion of living in their own house.

The fact that only one house was built in this phase also reflects the founders' crash of 1873. The GHH responded by dismissing 1/3 of the employees. The expansion of the settlement was initially stopped. The settlement now consisted of 21 residential buildings. The number of households had roughly doubled to 66, but the number of residents almost quadrupled. There were now 224 men and 194 women living in the settlement.

Fourth expansion stage from 1897

The fourth expansion stage was shaped by the mining industry . The north migration of the mining had already advanced over the Emscher. In addition to its two existing collieries in Oberhausen and Osterfeld , the GHH sacked three other mines in the Oberhausen area. The number of miners employed by GHH doubled during the expansion to 9,000, with a total GHH workforce of 18,000. A large part of the employees came from the Prussian eastern provinces and from Poland. The social consequences of this rapid population growth were devastating. The corporations started building company housing again. The GHH alone built fourteen new settlements, some with more than 100 houses, but this was only enough for a minority of five to six percent of the workforce. The main function of the company housing construction was to bind a small layer of permanent workers to the respective plant.

Only miners from the Osterfeld colliery were settled in the new residential units in Eisenheim, including many Poles, which led to objections from the "long-established" Eisenheimers: For example, one foreman wrote that "over the years they have created a quiet and comfortable stay", which one saw threatened by the influx of "foreign colliery workers".

Due to the bottlenecks in the housing market and the low wages, there was an overcrowding in the housing estates. Sometimes five instead of four families lived in a settlement house. In addition there was the boarding and roosting system . This means that individual, young, single miners use the same sleeping quarters - based on their working hours - in shifts . During a revision, eight boarders were found in one apartment; the average in an investigation for the Recklinghausen district was 2.4 per apartment. The nominal number of 186 existing households in Eisenheim is also likely to have been exceeded.

A total of 30 apartment buildings were built under the name Eisenheim II. First the existing gaps were filled: Kasernenstrasse (Fuldastrasse no. 3, 9, 11), Communalweg (Wesselkampstrasse no. 37, 39, 41, 43) and Berliner Strasse (no. 4, 6). According to Hermann Lueg's original plans, Koloniestrasse and Eisenheimerstrasse were laid out as connecting roads within the settlement. This also shortened the route to Vestischen Strasse to the north, where an easily accessible business district had now developed. In 1898, further houses were built along the north side of the new Koloniestrasse (Werrastrasse No. 2, 4, 6, 10) and another house opposite the house at Wesselkampstrasse 43 on the Osterfeld mine.

In the same year, tram line 1 was opened, which led on Provinzialstraße - past the Masters' Houses - to Sterkrade. In 1901 the houses in the settlement were given house numbers and gas pipes were laid in the master houses on Provinzialstrasse. The settlement received street lighting with gas lights.

After a four-year break, the expansion was continued with the buildings in Eisenheimer Strasse (No. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). The last houses were built in 1903 on Eisenheimer Straße (No. 2, 4) and Koloniestraße (Werrastraße No. 1, 3, 5, 7). Another house stood at the railway underpass opposite Wesselkamp No. 39. The total number of houses was now 51 houses. From an administrative point of view, the GHH housing management made a distinction between the older apartments, which were assigned to the rolling mill as Eisenheim I, and Eisenheim II, which was subordinate to the Osterfeld colliery.

On October 1, 1905, the Catholic School West was opened on Wesselkampstrasse. In the opening year it was visited by 135 children. The school was closed in 1943 due to the air raids. It was not rebuilt after the war, the children then went to the neighboring Catholic Osterfelderheideschule in shifts . The construction of a children's home in 1911 was the last major structural expansion of the settlement.

After the end of the First World War, individual streets, such as Berliner Strasse, were given power poles. The entire electrification of the settlement lasted until the 1930s. At the beginning of the last century, only the houses on thoroughfares were connected to the urban sewer system; most of them were only connected to the urban sewer system in the 1970s. Until then, the houses drained into the street gutters and the faeces from the outhouses in the toilet blocks were used as fertilizer along with the manure in the gardens of the settlement . Until the renovations in the 1970s, most of Eisenheim's houses had neither a bathroom nor a toilet.

In the course of the 1930s, the streets were renamed to their current names. The first garage was built in Eisenheim in October 1938 . Otto Loos, Weselkampstrasse 29, received the approval to build a corrugated iron garage, but with the condition that it be planted against view from the street.

War damage and reconstruction

At the beginning of the Second World War, a bunker was built in the middle of the settlement in 1942 . On the evening of March 30, 1944, 23 (according to other sources 41) people were killed and 32 others injured when a single air mine dropped by a De Havilland Mosquito exploded immediately in front of the bunker entrance . Several houses were completely destroyed by bombing during the war, including two of the masters' houses on Sterkrader Strasse. The other masters' houses between Fuldastrasse and Eisenheimer Strasse were poorly repaired and were inhabited until 1952. The files give examples of the catastrophic situation. A colliery worker rented the stable of a destroyed master's house because, in addition to his family of seven, he also had to accommodate relatives who had fled from the east. Another family, three adults and two children, lived in the laundry room of a destroyed master's house. The bunker was also used as accommodation until the 1950s.

Nine houses on Werra- and Fuldastraße that were completely or partially destroyed were rebuilt in a simplified form between 1946 and 1958. The cost per house was around 15,000 DM . The five masters' houses on Sterkrader Strasse between Eisenheimer Strasse and Fuldastrasse were demolished beginning in 1948. From 1952 four three-story apartment blocks were built in their place. The possibility of providing more residential units on the same floor space could generate higher returns. The installation of a bathroom and toilet also led to higher rents. The former Hofweg behind the houses was called "Marmeladenstrasse" by the people of Eisenheim, as the residents there had to pay a considerable part of their wages for the rent, which is why there was often jam as a topping on bread - instead of sausage.

According to estimates, the cost of repairing one of the masters' houses on Sterkrader Strasse in the early 1960s would have been DM 50,000, an expense that was no longer considered worthwhile in the event of a planned “total renovation” (read: demolition) of the settlement, so that the The two remaining Masters' Houses were also demolished in 1962. This place is still undeveloped today. At the end of the 1960s, the house at Weselkampstraße 42 on the works railway embankment was the last to be demolished in the settlement.

First listed workers' settlement in Germany

Impending demolition

After the Second World War, the allied forces wanted the powerful Ruhr concerns to be disentangled. The GHH only operated the further processing of steel under its old name. The production of steel was continued by Hüttenwerke Oberhausen AG ( HOAG ). Mining was assigned to Bergbau AG Neue Hope . Eisenheim was placed under the management of the HOAG, but most of the apartments were given to miners, so that the Bergbau AG decided on the allocation of the apartments. With the onset of the coal crisis , the societies' interest in their old settlements died out. These had already been written off ; in contrast, the housing companies benefited from the state housing construction subsidies . The trade unions also shared this way of thinking with their own company Neue Heimat .

Both the HOAG, the city administration and the media were determined to remove the "ugly old buildings", "veterans" of a "colony era". Headlines like “Here the oldest 'colony' of the GHH is enchanted with one blow. You won't recognize the old iron home, so to speak, when everything is finished. ”Were meant as a promise.

In 1961 a plan was presented to completely demolish Eisenheim and to build a “state-of-the-art settlement” in its place. The reason why Eisenheim was not torn down immediately was that there were plans to widen the federal road 223 at the same time . Two demolition plans blocked each other. The reason: Each of those involved - city administration and HOAG - wanted to get the best out of each other and so in both projects - each opposing - the mutual ownership relationships were played off against each other.

Eisenheim's owners changed several times: First, the HOAG was transferred to August Thyssen Hütte AG , today the estate has been managed by the TreuHandStelle für Bergmannswohnstätten , now THS GmbH , since 1992 .

The residents initially resisted the demolition plans with little success with letters to the editor. In 1968, at least the development plan was changed to the effect that a few historic buildings should be preserved and otherwise two-story apartment buildings and private homes should be built. In 1969 a list of signatures against the demolition plans was initiated.

Eisenheim research center for workers' housing in the Ruhr area

At Pentecost 1972, Roland Günter came to Eisenheim with a project group from the Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences . He already knew the settlement from his time as an employee of the state conservator and had heard about the demolition plans. His original plan was to document the settlement before it was destroyed. With the help of modern research and survey methods - also by Günter's wife Janne - the special social relationships that made up the quality of a workers' settlement were researched: the personal relationships with one another, but also the private and public paths within the settlement and the function of the self-created ones Buildings of the residents.

The project group organized exhibitions, press conferences, meetings, film screenings and other activities that drew media attention to Eisenheim. But the international scientific community also took note of Eisenheim. The residents founded a workers' initiative in 1972 , which was soon to become a model for 50 other such initiatives in other threatened settlements in the Ruhr area. A district council, formed from the general assembly of all residents, represented interests externally and prepared actions.

The first result of these efforts was that in 1972 Eisenheim was placed under monument protection by the state curator as the first workers' settlement in the Federal Republic .

Roland Günter, for whom Eisenheim was a regular stopover between his place of residence in Bonn and his place of work in Bielefeld, decided, inspired by an action by Günter Wallraff in Greece , to chain himself up in Eisenheim in the event of a demolition campaign. In the summer of 1974, Roland and Janna Günter and their two children moved into an apartment in one of the houses on Werrastrasse. The move received wide media coverage. Günter devoted a full-page report to Die Zeit : “Professor in the workers' settlement”. Against the argument of the settlement owners that the demolition was necessary because the houses have no toilet and no bath and the flushing water flows into the gutter, the family built a sewer to Fuldastraße, a bath and a toilet at the price of 6000 DM at the time, as well as another heater fed by a liquid gas tank into the apartment. At the time, this was countered by the new building price for subsidized social housing of 120,000 DM.

From 1974 to 1980 the secretariat of the Eisenheim Research Center for workers' housing in the Ruhr area was practically in the kitchen of the apartment . The main research areas were the structure of the settlement, especially the use of architecture, the working-class language and working-class culture. The studies were able to counter the mainstream of the time , which produced high-rise buildings according to the “length times width times money” scheme, with a lively alternative. Architects, geographers and social scientists benefit from the studies that highlighted the practical values of the settlement, which its residents took for granted, but which were called into question by the demolition ideology. By disclosing this practical knowledge , the self-confidence and the ability to act of the settlement residents could be strengthened. The research center also became the secretariat and contact point for the 50 other workers' initiatives in the Ruhr area.

“Probably for the first time in Germany, the function of the numerous connecting paths, the public and private spaces and the 'buildings' created by the residents themselves was examined in this level of detail. The various studies that were carried out in Eisenheim, which can now be regarded as 'classics' of the social sciences of the 1970s, thus played a major role in the ' paradigm shift ' in a public that has since then been more focused on the social effects of architecture and urban planning. "

The Günters' house became a guest house for a large number of renowned visitors who supported the rescue of Eisenheim and created a national and international stage for this issue.

The difficult way of salvation

At the 1974 Architects' Day, Federal President Gustav Heinemann highlighted Eisenheim as an example of “social architecture” as opposed to “purely technical and economic solutions”. In the same year, the city of Oberhausen applied with the votes of all parliamentary groups for redevelopment in accordance with the Urban Development Act . This required an assessment. This was followed in 1975 by the unanimous decision ( SPD , CDU , FDP of the city parliament ) to preserve and renovate the settlement.

The North Rhine-Westphalian Interior Minister Burkhard Hirsch (FDP) was still against Eisenheim. He got into a dispute with the state curator Günther Borchers and the chairman of the Council of Europe commission for monument protection, the MdB and MEP Olaf Schwencke (SPD). Then he tried to transfer responsibility for a demolition to the department of Social Minister Friedhelm Farthmann (SPD) with the argument that the settlement would be severely impaired by the neighboring Osterfeld coking plant . But the Oberhausen MdL Heinz Schleußer (SPD) intervened. In 1976, the year of the Bundestag election, the three big parties - each for themselves - discovered the advantages of the workers' settlements typical of the district. Most recently, Interior Minister Hirsch had to accept a state funding program for living areas with a special social structure (official German for workers' housing estate).

In January 1977, during a broadcast by Hallo OB Van with the title “What the war did not destroy, the redevelopment destroyed” on the square in front of the bunker, Carmen Thomas announced the news of the rescue of the settlement in the form of a letter from Minister Farthmann . The media-effective staging was immediately used to call on the city administration to end the demolition of the Rhine Prussia settlement that had just begun .

In 1978 the workers' initiative received one of the first cultural prizes from the Kulturpolitische Gesellschaft .

A "large technical commission" has now been set up to organize the necessary renovation measures, the sewer system, the installation of sanitary facilities and the interior work. Participants were residents, social architects and consultants chosen by the Eisenheimers, the city administration represented by the Office for Redevelopment, members of parliament, August Thyssen Hütte AG as the owner, the redevelopment agency (Thyssen build and live) and the housing administration of Ruhrkohle AG . In a “small technical commission”, the daily problems between the two social architects Ernst Althoff and Niklaus Fritschi and the construction management of the Thyssen company were discussed in weekly Monday conferences .

A container estate was set up in the area around the bunker, in which the residents could live while their apartments were being renovated. After initial skepticism, this close coexistence developed into an even stronger sense of unity .

“The time in the container was wonderful. Everything was very neat. The paths in front of the containers were paved. There were flowers on the edge. We sat outside in the evening. We celebrated a lot. "

At that time, almost 500 people lived in the remaining 39 houses, around 75 percent of whom were workers. The majority of them worked in collieries, and a smelting settlement had become a colliery colony.

In 1981 the renovation was completed. In what is now the Eisenheim Museum, the rescue of the settlement was documented and a basic set of furniture was created from household resolutions to represent the previous life situation in the settlement. In 1996, for the 150th anniversary of the settlement, the project “ Talking streets - talking monuments ” followed. On more than 70 boards, most of which are attached to the buildings, you can find out - in passing - the "... contexts of the construction phases and life in and between the houses."

Twenty years later, Roland Günter commented on the situation in the workers' settlements as follows:

“I would like the many people in workers' housing estates to remember: ten years of toughest conflicts with demolition and speculation gangsters. We didn't win this battle so that egomania is now gnawing the settlements beyond recognition. They should find out where they live and what such settlements mean for culture. "

architecture

Various house types were used in the 60-year construction period. In Eisenheim, the cross ground plan was revolutionized in a unique way and in this form became a model for other settlements in the Ruhr area.

The first houses still reflect that the character of the settlement, whether urban or rural, had not yet been determined. The Ruhr area was and is not a classic city that developed from a center. Joseph Roth described it (in relation to food) as follows:

“A big city has centers, streets connected by the meaning of a plant, it has a history and its development that can be monitored is reassuring. It has periphery and a very decided limit. But here are a dozen beginnings, here are a dozen ends. Country wants to begin, but a wire is already running and denying it. "

The area around Eisenheim was a heathland. The newly created industrial sites and the stations of the Cologne-Mindener Railway formed the crystallization points for new settlements. In Eisenheim, as in many other workers' settlements, a rural type of construction prevailed, as the workers who were to be recruited by them mostly came from a rural environment and were also supposed to provide for themselves by keeping livestock and growing vegetables.

Residential houses

Rural small house

The Masters' Houses on Provinzialstrasse. Year of construction 1846

- It was a one and a half story, eaves brick buildings. They were plastered white with a circumferential, floor- dividing cornice and niches in the masonry above the doors and windows.

- They contained two separate living units with entrances next to each other at the front and each with its own kitchen exit at the back. Three rooms were on the ground floor, two rooms in the floor space of the mezzanine. The living space per residential unit was a total of 70 m².

- Attached to it were two one-story brick toilet / stable buildings with separate access for each residential unit.

Urban three-window house

"Kaserne" Fuldastrasse No. 5/7. Year of construction 1846

- This is a two-storey semi-detached house with a brick pitched roof. It has a two-tier eaves cornice and is kept in the townhouse style, which is based on the urban three-window house .

- It originally contained a total of eight residential units, each with two adjacent house entrances and a common hallway behind with access to the courtyard for two families on the first and second floors. Each apartment had three rooms with 25, 13.5 and 17 m².

- The brick toilet / stable building is separate. A common toilet for each ground floor and upper floor unit was located at the house.

- The house type followed the barracks concept and was designed for tenants. The assumption that the barracks was initially a cruet , i.e. a single home, is wrong. The first residents were families of skilled workers. The name goes back to Frederician barracks , which were not crew quarters but housing complexes for soldiers and their families.

Combination type I

Two-storey eaves houses at Wesselkampstrasse No. 27/29 and 31/39, built in 1846

- These were brick buildings painted yellow with a simple, floor-dividing cornice on the front.

- They originally contained four apartments each. The room layout was identical to that of the barracks apartments, but each with a total of only 43 m². These were the smallest apartments in Eisenheim. The floor plan and the view resembled the urban three-window house of the barracks. The free-standing construction and the attached stable / toilet construction, however, resembled the master's houses and thus the small rural house.

- The toilet / stable buildings were built on and had their own gable roof.

- Like the barracks, this type of building had two disadvantages: shift workers working at night did not have adequately protected relaxation rooms during the day and the hallway had to be shared between the ground floor and the upper floor apartment, a potential for neighborhood disputes.

Combination type II

One and a half storey eaves houses in Wesselkampstrasse No. 19/21 and 23/25. Year of construction 1865/66

- These are yellowish painted brick buildings with doorways lying next to each other. They have a floor-dividing cornice and a flat, three-tiered eaves. In the front wall of the house there are rectangular arched niches on the mezzanine. In their external appearance they resemble the houses built at the same time on Berliner Straße.

- However, they only contained two master apartments per house. Five rooms and an attic with a living space of 96 m² per apartment. They were the most generously equipped apartments in Eisenheim. They were given exclusively to "civil servants", foremen and technical employees of the Gutehoffnungshütte

- The toilet / stable building is a single-storey brick building with a pent roof that falls away from the house and is separate from the house.

- In the mid-1930s, the level of the street was raised so that the house entrances are now below street level.

Cross type

Basic shape based on the Mühlhauser pattern

Berliner Straße, built in 1865/66

- A house shape that was first used on a large scale in the cité ouvrière in Mulhouse, Alsace .

- It is a one and a half storey eaves house in brick. The facade with smooth surfaces and clear proportions has a classicistic appearance. Basalt frames and cassette-shaped niches over the doors and windows are above the doors. The wall anchors were attached to protect against mountain damage . There is a protruding chimney on each of the narrow sides.

- The houses were laid out as a four-family house with a cross plan. There are two house entrances next to each other, one facing the courtyard and one facing the street.

- Through the front door you entered the first living room, which also contained the stairs to the upper floor. On the ground floor and the upper floor, another room each led from the room with stairs. With a total living area of 55 m², another room was gained.

- The one-story brick toilet / stable building is located separately above the courtyard.

- In Oberhausen, this type of house was first used in the Knappenviertel .

Cross type with separate entrances

Wesselkampstraße 35: built in 1872

- This is a one and a half storey eaves house made of brick with a two-tiered eaves and arched windows. The increase on the street side was made during a later renovation.

- With this type of cross, the entrance to the individual apartments was relocated to the four outer walls.

- The entrance to the house led into a small hallway with stairs. On the ground floor there was a living room and a kitchen, on the upper floor there were two bedrooms. The living space was 50 square meters.

- This type of house was first used in this house in Oberhausen. The clear separation of sleeping and living areas ensured that shift workers could sleep undisturbed in the upper rooms during the day.

- Since the life of families also often took place in front of the houses, it was possible for the first time to assign each family their own courtyard area.

- The one-story brick toilet / stable building is located separately above the courtyard.

Variants of the third expansion stage

Werrastraße 10, built in 1898 and Eisenheimer Straße No. 5, built in 1902.

- There are two house shapes derived from the variant from 1872. They only differ in the different brick ornaments. They are more cautious about the houses built after 1900.

- The eaves, one and a half story brick buildings had entrances on all four sides. In the older houses there is a brick pattern over the doors, a multi-tiered brick cornice with tooth and bevel cut friezes below the eaves and a coffered frieze with shell- shaped panels on the long sides of the mezzanine. There are dormers in the attic.

- The younger houses have arched windows with cement keystones.

- The one-story brick toilet / stall building is separate.

- This type of building can also be found in other Oberhausen colonies, such as Stemmersberg , Dunkelschlag and Ripshorster Straße .

Gardens

Each family was entitled to 200 to 300 m² of land. The land was divided into an ornamental garden part and a utility part . The ornamental garden was in the houses of the newer cross type for the families in the headboards of the houses in front of their front door. The families with the apartment facing the street or the courtyard had their ornamental garden next to the stable / toilet block. The kitchen garden was for each of the families in elongated strips behind the stable / toilet house. The areas were usually cultivated by the women and children. Together with the farm animals (pigs or goats) kept in the stalls, they served for self-sufficiency. Behind the stable / toilet house was a dung / compost heap for each family.

High bunker

The bunker was built around 1942. It is a block-shaped, massive raised bunker made of reinforced concrete. At 9:45 p.m. on March 30, 1944, 41 people, including four children, were killed and 23 people injured when a single bomb hit the bunker entrance. The alert was given too late and the bomb came from a bomber that was probably flying sporadically. After the war, the bunker served as an emergency shelter for bombed-out families until the 1950s. After that it was used for a short time to grow mushrooms . In the times of the workers' initiative, an agreement was made with a building contractor that he should pour earth all around. For the children it was a scenic area and in winter a toboggan run. But the Federal Property Office insisted on a complete evacuation. The entire bunker was made functional again for an amount unknown. The Eisenheimer say that the amount was as high as the entire cost of the redevelopment of the settlement.

The wash houses

- The wash houses were built in 1952. They are single-storey brick buildings with a hipped roof. The four entrance doors led to washing and drying rooms, one behind the other. The total area is 128 m².

Werrastrasse

- This house was expanded into the Volkshaus in 1974 . It served as a meeting and community center and as a meeting room for the district council . It was inaugurated on November 30, 1974 in the presence of futurologist Robert Jungk , who set up a future workshop. The Volkshaus was and is also used for family celebrations, bazaars and other leisure events. At times it was also the office of the Volksblatt , a newspaper for citizens' initiatives. In the front garden are works of art by the miner artist Karl Falk († 1978).

Eisenheimer Strasse

- At first this house was used as a youth center. The children's home was later moved here, giving the kindergarten that was destroyed in the war a successor institution managed by the Eisenheimers themselves.

Berlin street

- The wash house was taken out of service in 1968. It was converted into a museum in the late 1970s. A workers' apartment was furnished with furniture from an estate, and at the end of the 1980s the museum was incorporated into the LVR Industrial Museum in Oberhausen . It was completely redesigned and today contains the Eisenheim exhibition . Foundation, expansion, decline and new beginning of the oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area .

The blue tower

At the corner of Eisenheimer Strasse and Wesselkampstrasse, there was initially a coal mine of the last expansion stage. In 1911 the Gutehoffnungshütte built several children's houses in various collieries for its centenary. A photo from the 1930s suggests that the original house has been greatly enlarged through an extension and further renovations. It was a double-gabled, one-and-a-half-story brick house with a winter garden-like extension on the back wall. Two teachers looked after around fifty to sixty children. The kindergarten was destroyed in World War II.

In 2003 Roland and Janne Günter built the “Blue Tower of Many Books” on the property. It was created in teamwork with, among others, the architect Bernhard Küppers, the former city architect Bottrops and the architect of the local Albers Museum " Quadrat ".

In addition to the library, the “poets' garden” was created by Herman Prigann with texts by the poet and screenwriter Tonino Guerra .

The library is the workplace of the Günter couple and is available for smaller conferences. The 25,000 volumes as well as the archive with a focus on Eisenheim, citizens' initiatives, monument preservation, industrial culture and photo collections are available to national and international students. The library sees itself in the tradition of the cultural history library of the Aby Warburg .

The building stands in conscious contrast to the surrounding buildings, in accordance with the possibilities of monument preservation, which allow new buildings not to imitate, but to contrast. The quality of the building should prevent the building from being perceived as disruptive. Instead, a thoughtful tension should be created. The library takes up the tradition of post-war reconnection with the Bauhaus . The large panes should convey infinity and openness.

“Openness is the most important character of the Eisenheim estate. Openness here is a manifest against isolation, barricading, isolation and loneliness. A call: Neighborhood, togetherness, solidarity, learning from one another, experiencing with humanity, also "love your neighbor" - an ancient and at the same time promising sentence. "

literature

- Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind". Eisenheim - the oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history (= writings of the Rheinisches Industriemuseum . Volume 12 ). Rheinland-Verlag et al., Cologne et al. 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 .

- Janne Günter : Living in Eisenheim. Work, communication and socialization in a workers' settlement. Beltz, Weinheim et al. 1980, ISBN 3-407-57021-X .

- Janne Günter, Roland Günter : “Talking Streets” in Eisenheim. Concept and texts of all panels in the oldest settlement (1846/1901) in the Ruhr area. Klartext-Verlag, Essen 1999, ISBN 3-88474-810-6 .

- Janne Günter, Roland Günter: "Talking Streets" : The boards on site .

- Roland Günter: In the Valley of the Kings. A travel book on the Emscher, Rhine and Ruhr . Klartext-Verlag, Essen 1994, ISBN 3-88474-044-X .

- Roland Günter, Janne Günter: The workers' housing estate Eisenheim in Oberhausen (= Rheinische Kunststätten. Issue No. 541). Rhenish Association for Monument Preservation and Landscape Protection , Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-86526-086-4 .

- Günter Morsch : Eisenheim. Oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area (= hiking trails to industrial history . Volume 1 ). Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 .

Web links

- Description of this settlement as part of the Route of Industrial Heritage

- City of Oberhausen: Eisenheim settlement - museum in the middle of life

- LVR Industriemuseum St. Antony-Hütte: Museum Eisenheim - The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area

- Literature on the Eisenheim settlement in the catalog of the German National Library

- Portrait: Eisenheim on Planet Wissen

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 7.

- ^ A b c Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel: Counter-defense .

- ↑ after: Rainer Wirtz in: Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 6.

- ^ A b Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 21.

- ^ "Talking streets - talking monuments" on Wikipedia Commons - photographs of the project boards.

- ↑ a b Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 24.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 11.

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 24; Morsch speaks of 32 mornings : Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 5.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 5.

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 26f.

- ↑ a b Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel The difficult birth of the settlement .

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 27.

- ↑ Vol. 2, Reprint New York, 1969 | Source = Translation: Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 28.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 9.

- ^ A b Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 17.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 12f.

- ↑ Roland Günter: Project talking streets , panel: Housing reform: The brilliant cross plan .

- ^ A b Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 10.

- ↑ see also: Miners' strike of 1889

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 13f.

- ^ A b c Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 18.

- ↑ a b Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 30f.

- ↑ a b Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 44.

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 31.

- ↑ Ralph Wilms: 41 people died in front of the bunker entrance in Eisenheim , WAZ.de , May 29, 2015

- ↑ Martin Middlebrook: The night the bombers died. The attack on Nuremberg and its consequences for the aerial warfare , Ullstein Verlag , Frankfurt 1975, ISBN 3-550-07315-1

- ↑ Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 47.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 19.

- ↑ a b Dorit Grollmann: "... for capable masters and workers of the right kind" . Eisenheim. The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area makes history. In: Landschaftsverband Rheinland Rheinisches Industriemuseum writings . tape 12 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1606-2 . , P. 57.

- ↑ Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , blackboard: Value change: From the “model settlement” to the “slum” .

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 19 f.

- ^ A b Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 20.

- ^ Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , blackboard: Das Haus Werrastraße 1 .

- ↑ Peter Dellmann, quoted from Roland Günter: Project speaking streets , panel: The house of initiatives .

- ^ Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel: The House of Initiatives

- ^ Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel: To guest .

- ^ A b Roland Günter: Project Talking Roads , blackboard: Obstacles on the way to rescue .

- ^ A b c Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel: Events around the bunker .

- ↑ Culture Prize of the Kulturpolitische Gesellschaft .

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 22.

- ^ Roland Günter: Project Talking Streets , panel: " Talking Streets - Talking Architectural Monuments ".

- ↑ Roland Günter in: Rainer Henselowsky (Ed.): Vom Kohlenpott zur Metropole Ruhr; edition rainruhr; Essen 2007; ISBN 978-3-9811598-0-6 ; P. 64.

- ↑ after: Hans-Werner Wehling: Cultural Landscape Ruhr Area in Transition. Regional, local and European aspects, in: Ulrich Borsdorf, Heinrich Theodor Grütter, Dieter Nellen (eds.): Future was always . On the history of the Ruhr Metropolis. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89861-504-4 . , P. 43.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 30ff.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 33ff.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 41ff.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 44ff.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 52.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 46.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 53.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 26.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 37.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 28f.

- ^ Günter Morsch: Eisenheim . The oldest workers' settlement in the Ruhr area. In: Hiking trails on industrial history . tape 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7927-1195-8 . , P. 26f.

- ↑ a b c information sheet on the building , as of February 20, 2010.

Coordinates: 51 ° 30 ′ 10.5 ″ N , 6 ° 51 ′ 57.3 ″ E