Villa Huegel (Essen)

The Villa Hügel in the Essen district of Bredeney was built by Alfred Krupp in 1870–1873 and is the former residential and state house of the Krupp industrial family .

The castle-like villa has 8,100 square meters on their living and usable area over 269 rooms and is located - in a prominent place above the Ruhr Valley and the Baldeneysee - in 28 hectares large associated Hill Park .

Today the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation is the owner of the property. The Ruhr Kulturstiftung is also located in the villa . B. concerts or exhibitions. Numerous historical rooms as well as the Krupp Historical Exhibition can be viewed during regular opening hours.

history

prehistory

The creation of the villa goes hand in hand with the changes in Friedrich Krupp AG . In 1862, Alfred Krupp introduced power of attorney to the company. He intended to limit his role in the rapidly growing company to strategic decisions and the supervisory function. It was customary to live on company premises up to now, but this “withdrawal” is also reflected in the relocation of the family's place of residence.

In the autumn of 1863 Krupp visited the current site and in January 1864 decided to purchase as much as possible of the former Klosterbuschhof estate. To speed up the move, the Klosterbuschhof was first extended by a tower and converted into a villa. The first sketches of the building were made by Krupp himself and submitted to the company's internal construction office, initially under the direction of Ferdinand Barchewitz, and from 1863 under the direction of Gustav Kraemer , for further processing. After Kraemer had taken over the management of the construction office, Barchewitz made plans based on Krupp's sketches, which served as the basis for further planning.

The construction of the villa

After soil investigations had shown that there were a number of old shaft systems on the site that had to be secured in the course of the construction work, work on the actual villa finally began in 1869. From Nice, Krupp instructed the power of attorney to prepare the work for laying the foundation. The first thing to do was to look for an architect. On April 15, 1869, a corresponding advertisement appeared in the Deutsche Bauzeitung . However, since this did not get the desired response, two more advertisements were published on September 30th. The lack of understanding that was to trigger the conflict between the later architects and the client was already becoming apparent. Krupp pushed for a tender for the materials for the construction of the villa and the construction of a port for their delivery, although no concrete plans for the building were yet available. The fact that there were no usable plans from which the future shape of the villa could be seen made the search for an architect more difficult. Richard Lucae , for example, turned down a job on the grounds that, in his opinion, Barchewitz's plans would have to be completely revised.

Since no suitable architect had been found by October 4th, Kraemer suggested contacting the Cologne cathedral master builder Richard Voigtel in order to at least clarify the material issue. Also because Krupp was afraid of fire, non-combustible materials such as stone, steel or glass were used wherever possible. Furthermore, he personally went in search of qualified architects who should implement the project. In doing so, however, two points turned out to be the greatest difficulty: On the one hand, Barchewitz's plans were seen as out of the question, and on the other, Krupp's frequent interference and his view of the role of the architect as an assistant to his ideas deterred competent experts. This criticism voiced by Kraemer, however, bounced off Krupp.

In a letter dated October 13, 1869, he replied to Kraemer: “Even if it is not in Berlin, the rest of the great civilized globe will surely provide a conductor of practical work as we need him ... in sizes and locations, such as I do not want to change the connections between the rooms and the location of the buildings, because I want the whole thing to be carried out according to my terms like comfort and convenience and this can only be achieved here under my eyes at daily meetings. "

On January 23 and 24, 1870 Richard Voigtel, Paul Emanuel Spieker , Julius Emmerich , Gustav Hans Karl Diechmann and Gustav Kraemer met for a conference on the construction of the villa. Ferdinand Barchewitz was no longer invited. The relationship between him and Krupp had cooled down in the meantime, and from that day on he was only responsible for the outbuildings and farm buildings. Spieker agreed to revise Barchewitz's plans. Together with Johann Eduard Jacobsthal , he presented a revised plan to Krupp. The changes, such as loggias or balconies , were rejected by Krupp and had to be deleted from the plans.

Spieker once commented on the planning process in a letter to a colleague: "With the vague secret that covers the situation, you drive around in the fog with a pole!" Then he went looking for a suitable architect for the Construction management. However, he pointed out to Krupp that just his idea of the salary of 2,400 to 3,000 thalers per year would not attract a well-known architect. August Orth, for example, he reported, had an income of between 6,000 and 8,000 thalers per year to the best of his knowledge. His first proposal, Victor von Weltzien, was rejected by Krupp due to his aristocratic origins. His second suggestion, Eduard Schwarz, also met with little approval, as he had not completed his master builder examination. After an intensive exchange of letters, on April 1, 1870, Schwarz finally stopped, so that construction work could be resumed.

The construction management was under great pressure from the start. After the start of the work, Schwarz first had to confirm in writing that the shell would be completed by October 1870. In addition, there were frequent reprimands and warnings from Krupp. Any material lying around that was not in its intended place was noted in writing by Krupp. After the basement ceiling had been completed on July 15, the application for the construction of a residential building was finally submitted to the building police. Although the area of the property was not known, the approval was granted without any problems.

In the same year, the work was overshadowed by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War on July 19. The majority of the French stonemasons left the construction site and some of the German workers were drafted into military service. Only forty stone saws, 300 bricklayers and 450 earthworkers were employed in the construction. In addition, Spieker and Jacobsthal gave up their positions prematurely and therefore the plans were not completely revised. In August, Schwarz called a conference for all those involved in the construction, as it became more and more obvious that the deadline for completion could no longer be met. Due to the shortage of materials and personnel, the completion of the shell has been postponed to November 30th. Furthermore, part of the natural stone cladding was replaced by brick. In addition, warnings that mining damage was to be feared in the southeastern area of the main building had to be ignored, as otherwise the construction process would be endangered. In November, the shell could be completed on the new date.

But already at this point in time cracks appeared in the structure. So the affected foundations should be supported. Since the necessary soil investigations were not yet completed, the scope of the work could not yet be estimated. Heavy rains in the autumn had undermined the foundations, so that on December 23, 1870 the ground below the southwest corner sagged around 20 cm and the bay window was torn off from the building. Krupp's anger over this misfortune was directed almost exclusively against Schwarz, who was already with his family in Berlin that day. He vented his anger in a twelve-page letter. He wrote that Schwarz preferred "to pursue the pleasure of leaving work on Saturday evenings instead of dedicating the holidays to securing the building".

Black's time was running out. Construction management was transferred to the Funcke and Schürenberg construction business . Kraemer, who was also affected by the events, defended Schwarz in a letter dated December 28th and even threatened to give notice if Krupp's order with regard to the construction management were not reversed. In another letter from Kraemer dated January 4, 1871, several executives of the Krupp construction office joined him. In addition, the completion date, which Krupp had arbitrarily set for October 1871, was not accepted. Krupp responded by setting up a separate construction office for the construction site and commissioning Julius Rasch to manage the office. From that day on, Kraemer was only responsible for construction activities on the factory premises. Black was now subordinate to Rasch. He immediately filed for leave. He was finally released on March 1, 1872.

Right at the beginning of his activity, Rasch initiated numerous changes in the organizational structure of the construction office. With this approach, he turned a large part of the workforce against himself. Nevertheless, work was resumed, but Krupp did not advance quickly enough.

Things quickly went no better than his predecessors in terms of the relationship with Krupp. As early as May 1872, Krupp got in touch with Paul Emanuel Spieker so that he, together with Johann Eduard Jacobsthal, could quickly put him in his place. In addition, he was showered with reprimands and reminders. In the end, the villa was completed under the management of Rasch and the Krupp family moved in on January 10, 1873. The planned construction time was thus exceeded by around a year and a half.

The villa through the generations

1888–1902: Friedrich Alfred Krupp

While Alfred Krupp's contemporaries judged the interior furnishings to be rather modest and reserved, Friedrich Alfred Krupp attached greater importance to sumptuous, comfortable living spaces. Together with his wife Margarethe Krupp (1854–1931) - advised by his brother-in-law Felix von Ende - he laid the foundations for the Krupp art collection, in which the important collection of Flemish tapestries (between 1500 and 1760) stood out. For the amusement of the Krupps and their prominent guests, tennis courts, riding facilities, reading and play rooms as well as a community center with a bowling alley were built.

The number of employees rose just as rapidly as the company's turnover: in 1876 they managed to get by with 66 employees, but in 1902 just 570 employees were enough for Krupp's “court”. During this time, there is also a lot of visitors to the villa (see also: Section "Social life" )

1902–1915: Bertha Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach

Bertha Krupp , the client's granddaughter, inherited the global company in 1902 at the age of only 16. Four years later she married Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach , who thus became the new owner of Villa Hügel. The large couple revitalized the villa and commissioned numerous conversions (see also: section “Conversions” ). The already magnificent interior was expanded with enthusiasm, as was the Friedrich Alfred Krupp collections.

1915–1952: Alfried Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach

The 1920s passed the villa without any major changes, as did the First World War . After Margarethe Krupp's death in 1931, Bertha, Gustav and Alfried Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach used the small house as a residence for a time. Alfried Krupp took over the Fried company in 1943. Croup. He was the last family member to live in Villa Hügel. In April 1945 the property was confiscated by the American occupation forces and declared the seat of the Allied Coal Control Commission . It was returned to the family in 1952.

The Villa Hügel today

In 1953 the Krupp family opened their former residence to the public. Exhibitions have been held here since then. The Villa Hügel also served as a place of representation for the Krupp Group. In 1984, Berthold Beitz set up the Ruhr Cultural Foundation, which succeeds Villa Hügel eV and organizes the major art and cultural exhibitions in the villa. The main building with many historical rooms can be visited today. The Krupp historical exhibition is housed in the adjoining building, the Little House. The Krupp archive has also been located in the villa since 1905 .

Interior layout of the villa

Like the external appearance of the building, the interior division was also determined by Alfred Krupp himself. The social rooms should be on the ground floor. These were grouped in groups of three around the great hall. The first floor was intended for the private rooms. These also included private business premises. On the second floor, in addition to the rooms for the staff, there were also attic and storage rooms. The basement was occupied by the kitchen, the pantries and the bathrooms for the staff. This arrangement was maintained until the end of the occupation of the villa, even if the living ideas of the generations following Alfred Krupp changed.

Technical equipment of the villa

The aim of the planning was to install the latest technical achievements of the time in the villa.

heater

Hot water heating

Alfred Krupp asked the system that each room could be heated to an individual temperature and that the air had to be free of any odors.

The first sketches of this system showed the main house with a drum-shaped, slotted ventilation attachment. This was reminiscent of the systems for ventilation of the Krupp cast steel factory that were common at that time . Apart from an attached flagpole, this technical facility should not be concealed in any way. Krupp decided on a low-pressure hot water heating system and had this carried out by the Berliner Kupfer- und Messingwerke C. Heckmann company. Two boilers were planned, which were located in the middle of the western basement. The southern half supplied the eastern half of the building, while the northern half was intended for the western part. The supply lines were distributed under the ceiling of the basement and then branched off vertically into the individual floors through cutouts in the wall. The radiators were columnar and stood like separate ovens on the walls. The ones in the corners were provided with capitals and feet like Greek columns. In the larger rooms, the radiators were hidden behind panels. All the radiators had pipes running through them, through which air flowed. In total, the system cost around 100,000 thalers, around a sixth of the total cost.

The Krupps noticed immediately after moving in that this technology was still in its infancy at that time. On the very first day, Alfred Krupp described the heating system as an unusable system. In February he wrote to the Dresden engineer Carl Friedrich Emil Kelling: “In the house one after the other gets sick from Zug.” So it had to be taken out of service after a short time. This deficiency finally led to Julius Rasch's dismissal in the summer of 1873.

In the following years the heating system was modified and repaired several times. It never met Krupp's expectations. Alfred Krupp's great-grandson, Berthold von Bohlen und Halbach , remembered in 1982 that the family was regularly ravaged by a wave of infections at the beginning of each heating season.

It should be noted that the main reason for the failure of the first heating system was the size of the main house. The same system that was installed in the smaller lodging house worked to the satisfaction of the host. In connection with the renovation plans, he said “that the rest of the little house should stay like this, because the heating can be regulated very well”.

First warm air heating

In the main house there is a Krupp invention of the lesser known type, which is still widely used today: the world's first modern warm air heating system . This combination of heating and ventilation is seen as the forerunner of air conditioning.

As early as 1873, a review commission suggested adding an injection and extraction system to the system. However, this was rejected for cost reasons. Another suggestion was to use electric lighting. The heating of the air from the gas lighting was a major problem as this, in conjunction with the stairwell, created a large part of the train in the house. The young electric lighting, which Edison had only patented the light bulb in the same year, was able to eliminate this problem.

After several offers had been obtained, an emergency meeting was called on March 27, 1882 in the garden pavilion of the villa. Since Krupp had evidently learned from the skirmish of competence during the construction of the villa, the management of the renovation should be in the hands of a specialist company. It was also decided to replace the previous hot water heating with hot air heating.

For this purpose, the boilers should be replaced by so-called calorifers . It was planned to accommodate this in a new building to be built around 50 meters from the lodging house. There, the outside air should be sucked in, heated to around 50 ° C and fed into the building. The plan was to heat around 40,000 m³ of cold air per hour and to channel it into the main, lodging and library building. Of these, around 27,500 m³ should be moistened with 213 liters of water. Some of the existing ovens could be used for the new heating. Nevertheless, 105 new heating openings had to be created, 51 of them on the ground floor. While the supplied air was distributed in several common pipes within the house, the exhaust air for each room was discharged via a separate pipe. To increase the suction, the pipes from the sideboards, kitchens, sinks and toilets were fitted with gas flames. The exit of the exhaust air pipes was right behind the roof balustrade, with at least two per room, the upper one being used in summer and the lower one in winter. These could be controlled from both the room and the basement.

The heating building was arranged in such a way that even the 18 meter high chimney could not be seen through the roof of the library. Three calorifers were installed there, two of which were intended for the main house. It was planned to equip these with hygrometers and anemometers so that the system could be controlled remotely.

The plant had its acid test in the winter of 1882/83. As with the first heater, the system did not run as expected. On the one hand, the upper rooms were not warm, but the basement and ground floor rooms were so hot that the parquet on the ground floor warped. In addition, the fans of the system could be heard throughout the house. Krupp expressed suspicions that the construction had deviated from the plans. An undated letter has come down to us in which other owners of the same heating system were written to to provide information about their heating systems and their function.

In order to still achieve satisfactory operation of the heating, Krupp ordered a comprehensive test run. The different heating settings should be tested in different weather conditions. He himself didn't want to move back into the house until the stoker was able to heat the rooms as originally planned for at least 14 days. The series of measurements began on March 8, 1883 and ended on March 31 at temperatures between −3 ° C and +7 ° C. During this time a total of 59.4 tons of coal and 12.1 tons of coke were used. The average water consumption was 370 liters per hour.

It is not known whether the system worked to the satisfaction of the users overall.

Second warm air heating

After the construction of a new waterworks in 1914, the warm air heating was replaced by a modern steam district heating system. This also took over the preparation of the hot water.

Water supply

Since the supply of the villa via the waterworks of the city of Essen was obviously not trusted, there were first indications as early as 1870 of a plan for a separate waterworks for the villa. On June 27, 1865, a contract was signed between the Prussian government and Alfred Krupp for the withdrawal of 300 liters of water per minute. Since, according to initial calculations, the expected water consumption for the Krupp systems was greater, an application was made for 0.25 m³ per second. As it was not explained in more detail why a larger amount was required, this application was rejected. After it was explained that it was planned to also supply the workers' settlement via this waterworks, the application was granted and the withdrawal of 0.08 m³ per second was permitted.

In the waterworks, Woolf's balancing steam engines were used to pump the water. The water was pumped into the basins above the villa in order to guarantee the water supply and, above all, the provision of any necessary extinguishing water in the event of a failure. The pools were designed to accommodate eight days of demand.

The waterworks was completed in late 1874 and the three pumps started operating on December 10th. A fourth pump followed in 1880.

There were also reasons for complaint about the water supply. Krupp wrote: "The horizontal conduction of the pipes and the pressure in them cause a blow every time they are used, which can be heard in all rooms, in the bedroom you can hear the use of a closet announced by a blow every time."

In 1882 they began to renew the water pipes. Nonetheless, the quality of the water steadily decreased. From 1897 the drinking water had to be boiled. As an alternative to drawing water from the Ruhr, attempts were made to supply water via wells, but this was unsuccessful due to the daily volume of 1,925 m³. In the short term, water even had to be drawn from the city network. In 1901 the Wolfsbachtal waterworks were built with an annual capacity of 12,000,000 m³. From then on, this was used to supply both the villa and the cast steel factory . The amount of water required in 1916 was around 600,000 m³. The old pumps were finally replaced by new ones in 1952.

Gas lighting

Alfred Krupp initially insisted that only oil, stearin or wax lighting should be used inside the house . Nevertheless, gas lights were installed in the building from the start. Initially, only the rooms of the staff were to be equipped with gas lighting, but plans from 1870 indicated seven gas lights for the family's bathrooms alone. In 1883 the house was then completely lit with gas. Due to the subsequent installation of the gas lighting, the stop cocks and pipes could be seen throughout the house.

In order to supply the villa with gas, an application was made on September 1, 1870 to set up a gas factory. This was approved on December 17th by the Prussian state government in Düsseldorf. The factory should be below the villa on the Ruhr. This was opened in October of the following year and initially delivered around 360,000 m³ per year. Initially, this capacity was sufficient to supply the system. It was not until 1907, when the daily requirement rose to around 2000 m³, that the capacity of the plant was exhausted. From then on you were forced to get additional gas from the factory. In 1911 the gas factory on the Ruhr was given up. From 1926 onwards, the city of Essen took care of everything. In 1935 the last lighting was switched from gas to electricity after around 64 years.

In addition to the lighting, the stoves in the kitchen were also heated with gas.

Electric lighting

Electricity was used in the villa during construction. Initially, however, this was only used for operating the telegraph. Electric lighting was only brought up for discussion by Alfred Krupp's family doctor Emil Ludwig Schmidt in 1880 in order to get the drafts created by the gas lighting under control. Three years later they thought again about electric lighting. A report by Ernst Hoëcker from January 13th again pointed out the advantages of this lighting. But it was not introduced as lighting until 1889 under Friedrich Alfred Krupp . For this purpose, the Stuttgart company G. Kuhn installed a steam engine on July 10th. The associated dynamos were delivered between July 11th and August 22nd. Seven years later - in the meantime a circular to prevent the waste of electricity had already been circulated - a separate power station was set up on the Ruhr. This was subordinated to the administration of the waterworks. Just one year later, the plant had to be expanded to include another dynamo. Since at this point in time the electricity had to be temporarily stored in accumulators , their capacity also had to be continuously expanded. In 1899 the capacity of the accumulator house was exhausted with 1150 amps . Nevertheless, consumption continued to rise. As early as 1905, the consumption had risen to 2500 amperes, which at the time of 100 volts corresponded to around 250 kilowatts.

An instruction to the caretaker from the war years also gives an indication of the efficiency of the warm air heating. The nightly power consumption for electrical heating should be limited to 20,000 watts . In addition, the porters were instructed to inquire whether lighting should be used to receive expected guests or not. In addition, they had to make sure to switch them off again when the last guest had left.

From 1931, parts of the power supply were taken over by RWE . Two networks of 100 volts direct current and 380 volts three-phase current were operated. In 1935, after around 64 years, the lighting was finally switched from gas to electricity.

Telegraph and telephone system

External

Telecommunication in the Villa Hügel showed a particular interdependence between private business and the public sector. Parts of the staff were both public employees and privately employed.

As early as 1867, Krupp had telegraphs installed within the plant for communication. At the same time, a line was laid to the newly acquired Klosterbuschhof estate. While the lines on the factory premises were also operated and maintained by the Krupp company, the connection to the estate does not seem to have been under the sole control of Krupp. Gustav Hans Carl Diechmann, who is responsible for the telegraphs on the factory premises, replied that the lines on the factory premises were in good condition and that those on the villa premises were being replaced, but that the local railroad was more or less rotten. This suggests that the lines between the factory and the villa were operated by the Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft .

The relationship between Krupp and the railroad seems to have been strained in the years to come. In 1893, for example, the hill administration asked the Imperial Post Office Directorate to urge the railway to renew the four lines along the line, to add another line and to set up two additional telephone and telegraph lines especially for visits by the emperor.

The telephone moved into the factory premises in 1880. In 1883 the first switchboard was set up. Three years later, the villa was finally equipped with an external telephone connection. This connection cost around 500 marks including the fees for the approval .

Intern

In addition to the external telephone system, there was also an internal system consisting of a bell and flap system. The center of this system was in the doorman's room in the main building. The porter and the servant on the respective floor were then alerted via a button. The porter could then see from his room whether the call was being followed. He also had the option of waking up the staff centrally via an induction alarm clock. In addition, there was a galvanometer in the north and south-east rooms on each floor , which should report any deviation from the room temperature directly to the heater.

Clocks

Shortly after moving into the villa on December 15, 1872, the central clock of the villa, which was located in the porter's room, became the decisive clock for the entire group. Every morning at nine o'clock the person responsible for the tower clock in the factory should be notified by telegram so that it could be set. The tower clock was located on the plant's water tower at a height of 53 meters. All other clocks in the factory should then be set accordingly at twelve o'clock by only one authorized person. The clocks in the factory were then not allowed to deviate from the time on the tower clock by more than a minute. Later this was reduced to half a minute. It was even planned to hire someone to align the city clocks with the tower clock.

Others

In addition to these numerous technical facilities in the house, there was a lot more that reflected the state of the art of the time. For example, a hydraulic lift, the automobile and the first film projectors soon found their way into the villa.

Artistic equipment of the villa

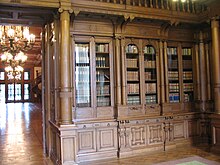

The sculptor Max Dennert created two sphinxes for the entrance to today's library .

Conversions

After Alfred Krupp's death, the interior of the villa was completely renewed in the style of the time, the old system can only be seen in side areas (stairwells, servant areas, railings). The facility consists of a smaller building and the main building, which are connected to each other by a long wing of the library and the ballroom. At the time of its construction, Villa Hügel was regarded as an object of demonstration of technical progress because of the modern technology wanted by Alfred Krupp and largely personally planned.

A complete farm belonged to the original facility, which was located in front of the neighboring house in order to ensure an independent supply. This was also torn down relatively quickly because it disrupted the overall representative image.

The extended ensemble of buildings of Villa Hills include built in 1870 as a restoration operation of the building administration of Villa beer hall hill that is now a restaurant and a hotel houses, and across the mountainside to Baldeneysee situated Station Hill . In 1894 a playhouse, the so-called Spatzenhaus, was built for the Krupp daughters Bertha and Barbara.

When creating the huge park, Alfred Krupp had fully grown trees planted so that he could see the park in its "final state" while he was still alive. Dead trees were quickly replaced by “new old ones”, which meant that the tree population in the Villa Hügel park is considerably older than the entire complex. The park is now around 28 hectares and was converted into an English landscape park in the post-war period.

Since 1953, important art exhibitions have been held regularly in the main building. For decades there have been concerts several times a year, among others by the Folkwang Chamber Orchestra. The eastern outbuilding contains a permanent exhibition on the family and company history. The park and the building can be visited for a small fee, provided that there are no exhibitions or special events organized by the Krupp Foundation .

staff

The personnel structure at the villa was regulated in detail. At the head of the staff was the caretaker, who was viewed by Alfred Krupp as a person of trust who was supposed to be "the mediator of our will". He was assisted by the cook and the housekeeper, who each had the staff of their area under themselves. All the others reported directly to the caretaker.

There were also numerous employees of various kinds. Among them were doctors, librarians, ironers, hairdressers, gardeners, house servants, housekeepers, housemaids, nannies, cooks, kitchen maids, coachmen, run boys, seamstresses, taxidermists, porters, tailors, waitresses, grooms , Caretakers, cattle maids, laundresses and white goods seamstresses. In 1903 there were a total of 502 people on the payroll. This number decreased to 421 towards the end of 1905 and rose again to 648 by 1914. In addition to these permanent employees, temporary workers were employed as required, e.g. B. for large companies.

Most of the staff was located in the immediate vicinity of the villa and was also supplied in large areas by the companies on the hillside. The convenience store was available to the staff, where they could choose and shop from a wide range of products at reasonable prices. Most of the employees were recruited from the surrounding workers' quarters and peasant communities.

Overall, there was a strict regime. In addition to honesty, punctuality, obedience, modesty, cleanliness and a sense of order, absolute discretion was required of the staff. In addition, personal relationships or even relationships between employees were strictly forbidden and, if disregarded, were punished with dismissal. Great importance was also attached to careful handling of the inventory. For example, 15 percent broken china was allowed. Anything above that was withheld from the staff's wages. Despite these rules, which are rigid from today's perspective, violations almost never occurred.

The restrictions were rewarded with extremely good pay. The porter received an annual salary of around 1,400 gold marks under Alfred Krupp. In addition, there were natural products from the management of the farm, as well as tips: This was collected centrally and flowed into the tip box. It was then distributed to the staff every six months according to a ratio. For example, the chef had a ratio of 40, the housekeeper was 30, the valet was 25, and so on. For comparison: a skilled worker had an annual salary of 1200 gold marks. For particularly long-serving employees, there was also vacation and a separate pension fund.

Social life

Large festive events were regularly held in the villa. What is noticeable here is that only some of those invited actually appeared. 588 people were invited to a ball on February 4, 1914, of which only 386, i.e. around two thirds, accepted. The high nobility from the Rhineland in particular hardly made any move to appear at Krupp's balls. Representatives from other steel companies or from banks were also often absent. The representatives of the government, the courts, the railways, local politics and the employers' associations appeared regularly. People from the fields of art, theater or literature came less often. Above all, however, representatives of the military were present, which reflected the company's position as an arms supplier.

Kaiser Wilhelm II in the Villa Huegel

A decisive change in social life at Villa Hügel began when Kaiser Wilhelm II took office in 1888. Did the emperor's predecessors, Wilhelm I and Friedrich III. , a more distant relationship to the Krupp family, this changed with the technology-loving Kaiser Wilhelm II. In the years leading up to the war, the Kaiser visited the villa eleven times. In order to do justice to the visits, Friedrich Alfred Krupp sent his caretaker to Berlin for the wedding of Friedrich Leopold of Prussia on June 24, 1889 for observation.

Wilhelm II's first visit took place on June 20, 1890. The program began at nine in the morning with the arrival of the emperor at the main office building. This was followed by a tour of three workshops, two cannon workshops, the mount construction and the shooting range. After refreshment at eleven, we went to the Krupp headquarters to visit the smelting furnace. Then it went on to the Krupp elementary school and the Schederhof household school. The midday meal was taken in a "small" group, consisting of wing adjutants , the chiefs of the military cabinet Emil von Albedyll and the secret civil cabinet Hermann von Lucanus , the tutor of Emperor Georg Ernst Hinzpeter , the personal physician Carl Fritz Wilhelm Förster , the regional president Hans Hermann von Berlepsch , District Administrator Joseph Anton Friedrich August Freiherr von Hövel , Lord Mayor Gustav Hache , another half dozen directors, three unspecified ladies and the head of the House of Krupp. A quartet of men sang with it. The visit ended shortly before nine-thirty with the emperor's departure. The visits and the program in the following years became more and more complex. In 1896 there were already forty place settings and the obligatory choir consisted of 1,100 people.

On October 15, 1906, Bertha Krupp and Gustav von Bohlen and Halbach married in the presence of the emperor . The celebrations lasted a total of five days. 125 guests were invited, as well as 60 civil servants and employees, 10 workers and 19 retired Kruppians. In addition there were the family members of the guests. Safety was a top priority. A pass had to be presented to enter the villa and patrols operated in the park. Five cooks, 19 waiters, 10 cleaning women, 19 carpenters, three saddlers and two electricians were hired to carry out the festivities.

The biggest festival before the war was the 100th anniversary on August 8th and 9th, 1912. For this purpose, the emperor traveled on the night of August 7th and stayed with his court until August 9th. Among the guests were Prince Heinrich , Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz . The festival began in the morning with the arrival of the emperor. After breakfast, a trip into town followed, where the mayor at the time, Wilhelm Holle , greeted us in front of the building of the mining association . The ceremony took place in the atrium of the company headquarters with various speeches. A factory tour followed. In the evening there was a feast with 450 invited guests. After the meal, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach and Kaiser Wilhelm II gave two speeches. On the second day, there were another factory tours.

organ

On the northern gallery of the Upper Hall is an organ that was built in 1912 by the American organ builder Aeolian Organ Company. The construction of this instrument was commissioned by Bertha and Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach . The instrument was used for house music and at social events.

In 1928 the organ manufacturer M. Welte & Söhne (Freiburg) restored and expanded the instrument . After a comprehensive overhaul by the organ building company Klais (Bonn) between 2003 and 2006, the instrument is playable again.

The registers are on pocket shops from Aeolian and Welte (1928) and are partially playable on both manuals . The instrument is swellable as a whole.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Pairing :

- Normal coupling: II / I, I / P, II / P

- Sub-octave coupling: I / I, II / II

- Super octave coupling: I / I, II / I, II / I

- Playing aids : shelves (equallage in I, in II), fixed combinations (piano, mezzoforte, forte), 5-step register crescendo , total threshold for the blinds in front of the organ chamber

- Secondary register: Chimes, Harp, each can only be registered on one manual

Hill park

The park was planned by Alfred Krupp from 1869 and completed in 1883 in his spirit. After his death in 1887, under his son Friedrich Alfred Krupp , and later Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach , the park changed more and more into a representative object. In the 1950s and 1960s, the park was extensively redesigned to become an English landscape park.

Outbuildings

Gardening

The gardening department was responsible for the garden and park design. For this purpose, it was divided into a utility and a nursery. It also had a meteorological observation station.

The first head gardener was Friedrich Bete. He held this post for almost forty years, during which time he was able to enlarge the ecology farm and expand the wildlife park into a western park. In 1897 he was replaced by Friedrich Veerhoff. He had completed his training in Kassel in the royal garden nursery Wilhelmshöhe and then worked in Erfurt , Vienna and Potsdam . Right at the beginning of his activity, he was able to increase his budget for the gardening business and hire additional assistants. He also expanded the park and the driving business.

Like the other area of the villa, the nursery was directly subordinate to the hill administration and had to make a budget calculation. The list had to be done in great detail under Alfred Krupp. So each plant had to be listed individually. Later they could be combined into larger items.

Large pavilions

The two large pavilions were on the southwest and southeast corners of the pergola . They appear for the first time in Brachewitz's plans from 1870 and were planned as a classical temple building. Later they were depicted in the Doric style and were also executed in this form in 1872. The interior was designed by Heinrich Heidsiek. At the time of their construction, these two pavilions were the only connection between the living area and the lower terrace area. Today there are paths to the lower park area at this point. They were created in the course of the redesign in 1961.

Small pavilions

The two small pavilions were intended as a direct transition between the residential building and the arcade. In the planning of 1878 they had a square floor plan and were open to the garden and pergola sides. There were also Tuscan columns in front of the corner pillars. The original interior design was also designed by Heinrich Heidsiek. It is not known whether this was implemented. From 1883 there was a statue of Wilhelm II in the northwest pavilion and one of Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Victor August Ernst in the northeast .

Arcade

The arcade was built at the same time as the two large pavilions and separated the upper from the lower terrace area. It was formed from a wall of 16 iron columns on one side and 16 oak columns on the other. The side to the garden made of oak columns was open, while wooden bars and wooden blinds were found between the iron columns as a boundary. The roof was formed by wooden girders made of oak beams and cross-shaped struts. Wooden beams served as the actual roofing across.

Stibadium

The stibadium was in the middle of the arcade . It consisted of a central and six stone pillars arranged in a semicircle, which were located on a terrace above the artificial grotto. The glass roof, which was on a wooden structure, was supported on this. A water basin was arranged in the middle. The middle column and the roof were dismantled after 1900.

grotto

The grotto was located between the two terraces below the stibadium. Although Alfred Krupp realized that there was a risk that the grotto could be recognized as unnatural, this was implemented. Construction began in 1871 and after completion consisted of three brick vaults that were faced with tufa-lime . The fact that Krupp was not impressed by the implementation, he had the first building demolished, shows in his words that, in his opinion, the architects "build such stupid things [...] and waste money on it". In 1883 the grotto was provided with plants so that it could no longer be seen at first glance.

Economy yard

The Ökonomiehof was based on the former farm of the Großbodt farmer, which was located on the original site of the estate. Parts of the courtyard were demolished while other parts were rebuilt and expanded. This is where the horses and wagons and the housekeepers should be accommodated. The riding stables were laid out in an east-west direction and formed two courtyards. The northern courtyard enclosed a riding arena, while the southern one formed an open riding arena. Krupp had also had a small study built over this stables . There was also a coach house for twenty cars with an apartment for the officials on the first floor in the Ökonomiehof . However, this collapsed in a hurricane in 1891 and was rebuilt as an unplastered brick building. In 1896 the riding arena and stables were renovated. It was noticeable that the harness room of the horse stable was very generously equipped. For example, it had a stucco ceiling and Art Nouveau décor and had a library with a reading room and a playroom with a pool table for the employees.

Officials houses

A total of three houses were built for the civil servants. The first was located south of the Ökonomiehof and was built in 1871. The second followed in 1872 on the main access road and in 1873 the third north of the Ökonomiehof on Hauptallee. The houses were built from exposed bricks in a simple architectural style.

Brandenbusch Colony

From 1895, the Brandenbusch settlement was built in the northern area of the facility especially for the workers on the site. This complex comprised a total of 34 buildings in 1897. Built in the style of a village, next to the residential building there was also a workers' lodge for 24 people, a steam laundry, a syringe house and a smokehouse. All houses consisted of two symmetrical halves and were provided with a basement and attic. Life in this area was strictly regulated. Shooting with firearms and wind rifles , the construction of stables, scaffolding, "ugly laundry stakes" and "ugly flower beds" were prohibited .

Gardening

The nursery was divided into three areas: the forcing, the fruit tree and the vegetable nursery. This division was probably taken over by the farmer Großbodt. The greenhouse was built in 1871 and expanded in 1872 to include a flower, pineapple and three wine greenhouses as well as an orangery. This nursery formed the basis of what later became known as the hill nursery beyond the borders of Essen. The nursery was expanded under Alfred Friedrich Krupp. A house for the apprentices was added in 1890, a laurel house in 1895, a kitchen building and an office building in 1897. The forcing was also expanded. In 1903 the orangery was replaced by a larger building and a larger greenhouse for orchids was set up by 1914.

In 1972 the nursery in the park was closed, only the administration remained in the park. The gardening and landscaping hill nursery with around 120 employees moved to Altendorfer Straße. The outdoor facilities of the Krupp housing are looked after from here. Orders from various housing construction companies complement the field of activity. The hill nursery continues to take care of the park.

Flower making

The flower making business with two greenhouses remained. They supplied the group with flowers and plants. Later, the bindery also supplied today's Messe Essen with flowers and plants. In 1978 the entire bindery ( floristry ) was dissolved from the group and privatized. This was taken over by the then department head and master flower maker (today's name of master florist) Josef Scheiermann. 1981 Michael Scheiermann took over the business.

Sparrow House

Under Friedrich Alfred Krupp, the so-called Spatzenhaus was built in 1894 as a playhouse for the daughters Bertha and Barbara . This half-timbered house was built on a slope between the gorge and the terrace wall and includes, among other things, a playroom and a country-style kitchen. Together with a wooden arbor, it enclosed a children's playground. Here Krupp's daughters should learn to be a housewife in a playful way. The guest book of the Spatzenhaus lists Kaiser Wilhelm II and Empress Auguste Viktoria as guests.

New guest house

1914 followed with the new guest house, the last newly built building on the grounds of Villa Hügel. Today there are rooms of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation . It was built on the southeast corner of the workshop yard. It replaced the old guest house, which was meanwhile inhabited by Margarethe Krupp . The two-storey building, faced with bricks, had work, lodging and dining rooms as well as a kitchen and library.

Belvedere

In addition to the completed buildings, there were three projects that were planned but never implemented. One of them was the Belvedere . It was to be built on the southeast corner of the wall to prevent the Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft from laying the route of its railway line from Essen via Werden to Kettwig through the area of the lower terrace. It was planned as a two-storey building that would also house the porter's apartment. The lower part represented an extension of the lining wall, while the actual Belvedere was to be arranged above it. Of this building, only the base construction with the porter's apartment was implemented.

Japanese and Chinese pavilions

A second project that went unrealized was two Japanese and Chinese style pavilions. They were to be erected in 1872 to visit a Japanese and Chinese delegation. The equipment, including a fountain, should be designed in a way that is typical of the country.

Large bridges in the western park

The third project that was not implemented was a bridge in the western park. It should begin northeast of the house and lead into the western park. Krupp was impressed by the planning, but decided against the implementation due to the high costs. Instead, several small bridges were built.

Former Krupp possessions

literature

- Berthold Trenkner: Park and nursery of Villa Hügel . In: Die Gartenwelt , Volume VII, Issue 27, Richard Carl Schmicht, Leipzig 1903, pp. 313–317

- Tilmann Buddensieg : Villa Huegel. The Krupp house in Essen. Wolf Jobst Siedler Verlag GmbH, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-88680-102-0 .

- Renate Köhne-Lindenlaub: The Villa Hügel. Corporate residence through the ages. 3rd updated edition, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-422-02134-1 .

- Christa Hasselhorst : The park of Villa Hügel . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-422-02184-6 .

- Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln 2014, Documentation: Secret Villa Hügel , produced by Jörg Siepmann and Harry Flöter

- Stephen Pielhoff; Waltraud Murauer-Ziebach: In the Krupp house. The servants of Villa Hügel. (= Small row Villa Hügel). Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2016. ISBN 978-3-422-02438-0 ; review

Web links

- Description of this attraction and anchor point as part of the Route of Industrial Heritage

- Site of the Villa Hügel

- Alfried Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach Foundation - Villa Hügel and Archives

- Specialist article about the Villa Hügel at Monumente Online

- Excerpt from the list of monuments of the city of Essen (PDF)

- Literature on Villa Hügel in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Alfried Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach Foundation

- ↑ a b c d e f Tilmann Buddensieg: Villa Hügel. The Krupp house in Essen.

- ↑ Organ in the Villa Hügel. In: ruhr-guide.de. December 7, 2006, archived from the original on January 15, 2011 ; accessed on January 26, 2016 .

- ↑ www.orgelbau-klais.com: Disposition of the organ

Coordinates: 51 ° 24 ′ 25 ″ N , 7 ° 0 ′ 30 ″ E