Osterfeld colliery

| Osterfeld colliery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

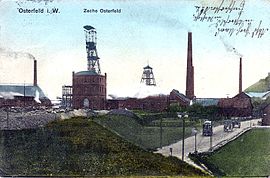

| historical postcard view from 1908 | |||

| other names | Oberhausen colliery, shaft 3 | ||

| Funding / year | Max. 2,800,000 t | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | Ruhrkohle AG | ||

| Employees | up to 5509 | ||

| Start of operation | 1879 | ||

| End of operation | 1992 | ||

| Successor use | Industrial monument, nature park | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Hard coal | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 51 ° 30 '11 " N , 6 ° 52' 34" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Osterfeld | ||

| local community | Oberhausen | ||

| Independent city ( NUTS3 ) | Oberhausen | ||

| country | State of North Rhine-Westphalia | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

| District | Ruhr area | ||

The Osterfeld colliery was a hard coal mine in Oberhausen - Osterfeld . At the beginning of the 20th century it was one of the largest and most efficient mines in the Ruhr area and was located in the Oberhausen field of the Gutehoffnungshütte (GHH) . The name of the mine is derived from the place where the mine was located. The colliery was in operation from 1879 to 1992, and its beginnings go back to the mid-19th century.

history

The search for coal

In 1853 the search for hard coal began in the municipality of Osterfeld . For this purpose, exploration wells were created through the overburden . Already in the initial phase there was a fatal accident with these wells. In addition, the drilling work at a depth of 225 meters caused great difficulties for the drilling team . The rock was so hard that the drilling progress was only 2.5 centimeters per day. In 1855 and 1856 coal was drilled in 15 places. The first coal was drilled near Eschenbrock in the Grafen-Garten. The finder of this deposit was the carpenter Hagedorn zu Essen. He managed to hit hard coal in the Eschenbrock area with three wells. Hagedorn sold his pit fields to the Gutehoffnungshütte . The Jacobi, Haniel & Huyssen smelter had three boreholes drilled between Gut Schulte-Venn and the Waghalz Bridge with its own drilling teams, but this was unsuccessful. A drilling team was also unsuccessful in the area around the Winkelheck farm. In 1873 the Gutehoffnungshütte submitted an operational plan for the construction of the Osterfeld colliery to the Gelsenkirchen Mining Authority.

The construction of the mine

1873 teufte the Zeche Oberhausen its shaft from the third The starting point of the shaft was on Zechenstrasse, today's Vestischen Strasse. On April 16, 1874, floating sand collapsed in the shaft at a depth of 34 meters , and the entire shaft broke . The shaft was therefore abandoned and in July 1874 a new shaft was added. This shaft had a shaft diameter of six meters. 1876 bay reached at a depth of 238 meters carbon . While the sinking work was still in progress, the first daytime facilities and the boiler house were erected and a boom water retention system was installed. In addition, connections to the Westfälische Bahn , the Rheinische Bahn and the Emschertalbahn were created. In 1878, in the shaft at a depth of 276 meters (m -228 NN ) the 1st sole applied and later at a depth of 377 meters (m -329 NN) the 2nd sole. In September of the same year, sinking was suspended at 397 meters. Since the colliery only had this one shaft at that time, a weather separator was installed in the shaft for weather management . The necessary negative pressure for sucking off the waste air was generated by the chimney of the boiler house.

The first years of operation

In 1879 the mine was renamed Zeche Osterfeld (shaft 1). At the same time, this operating area became independent. On October 3, 1879, the bay went into promotion . A steam hoisting machine with an output of 400 hp served as the drive . At this point in time, the construction site covers an area of 8.6 km 2 . The first coal miners and steers required for the operation of the mine came from the southern Ruhr area and the Aachen area. Laborers came from the surrounding area and the Münsterland and were trained as coal miners over the years. Almost all underground work was done manually. The coal was extracted with wedge-cutting , blasting was forbidden because of the danger of fire weather . In the distance promotion came pit pony used. In 1880, at a depth of 441 meters (−393 m above sea level), an auxiliary floor was driven in a southerly direction and the shaft was sunk deeper. The coal washing machine and the crew chews were put into operation above days . The kaue was only equipped with a large water basin in which the miners could wash themselves after work. In 1883 the third level was set at a depth of 485 meters (−437 m above sea level).

Due to a request from the mining authorities in 1881, according to which all mines must have a second escape route, the Osterfeld colliery was connected underground with the Oberhausen colliery in 1885 . On December 4, 1885, a firedamp explosion occurred in a department of the colliery , in which twelve miners were killed. The department had to be given up as a result. In the following year, a pit fan was installed above ground . The fan was driven by a steam engine and brought a noticeable improvement in the ventilation and better weather cooling . In 1895 a coking plant was put into operation. In 1897 the 4th level was set at a depth of 586 meters (−538 m above sea level). This bottom was not applied directly from the main shaft , but via a blind shaft . Due to increasing coal production, the deteriorated pit air again. The factory management therefore decided to dig a second shaft.

From 1898, next to shaft 1, shaft 2 with a diameter of five meters was sunk. The starting point of this shaft was 185 meters east of shaft 1. In 1897, shaft 2 reached the Carboniferous at a depth of 238 meters. A penetration was made with the 2nd sole. The shaft was equipped with a new pit fan. In July 1900, the Osterfeld 2 shaft was used as a weather shaft and Osterfeld 1 shaft as a fresh weather shaft.

The 20th century

In 1902 the weather shaft (shaft 2) reached the 4th level, the production started and the rod water retention was replaced by a more modern water retention with two piston pumps . These pumps were driven by steam and installed on the 4th level. In 1903 the shaft reached its final depth of 612 meters, all the setting Riche and the tray guide were installed. The Gutehoffnungshütte AG intended to step up coal production. In order to be able to offer higher conveying capacities, according to the plans of the plant management, it was not enough just to increase the workforce, but an additional shaft was required. The sinking work for weather shaft 3 began in 1903. The shaft attachment point was north of shafts 1 and 2. The shaft had a shaft diameter of 6.1 meters. In the same year the shaft was penetrated with the third level. In November 1904 the shaft was penetrated with the fourth level. In 1905 two new pit ventilators were put into operation, which were able to extract 16,000 m 3 of weather per minute. In 1906, the weather shaft 3 went into operation as a moving shaft. Shafts 1 and 2 now served as weather shafts and shaft 3 as fresh weather shafts . In 1907 a new first level was set at a depth of 296 meters (−248 m above sea level). This new level served to align the north field.

After 1905, technical improvements to the mining operations began. Mine locomotives were used to support the route, and the 170 mine horses were gradually sent to retire. In the main water drainage system, the two steam-driven pumps were replaced with two electric centrifugal pumps . The electricity for the two pumps was generated by a generator installed above ground . Despite the ventilation via three shafts, the Osterfeld mine workings remained at great risk of fire weather . In particular, the further expansion of the mine building forced the plant management to act. For this reason, the sinking of the weather shaft 4 began in 1912. The shaft was located in the north field, 1.7 kilometers north of shafts 1 to 3. On July 3, summer there was another mine accident. 16 miners lost their lives in a firedamp explosion . During the investigation by the mining authorities into the accident, human error was found to be the cause. Five boreholes were drilled in one break for the purpose of blasting . A coal seam was also drilled during this drilling work. During the following blasting work , dynamite was used instead of the weather explosive prescribed for such blasting . Its detonation ignited the methane flowing out of the boreholes , which flowed out of the coal seam. In 1914, the weather shaft 4 reached the Carboniferous at a depth of 314 meters. A penetration was made with the 2nd sole.

The time of the two world wars

The First World War

With the outbreak of the First World War and the associated mobilization , many miners were drafted into the war within a short period of time. As a result of this measure, the number of underground workers at the Osterfeld colliery was halved. The plant management tried to compensate for this by deploying young miners underground who were not yet 16 years old. But even this measure could not stop the decline in the workforce, until 1915 the workforce continued to decline. In the following years the weather shaft 4 was sunk deeper and in 1916 reached the 4th level. The shaft was given a brick-built, 43-meter-high headframe . The electric hoisting machine was located in the tower head . From 1922 were in the range promotion only compressed air locomotives and diesel locomotives used, there were at Zeche Osterfeld no pit pony. In 1924 the weather shaft 4 was put into operation as a cable car shaft . From 1928 to 1931 the coking plant was extensively renovated. In 1930 and 1931 there were considerable sales problems. For this reason, Gutehoffnungshütte AG took several measures to adjust funding. At first an attempt was made to adjust the promotion by means of party shifts to the sales, but this measure did not bring any permanent solution to the sales problem. The next step was taken in 1931 with the closure of the Hugo and Oberhausen collieries and the Sterkrade and Jacobi coking plants. In 1931 the mine field of the closed Oberhausen colliery was taken over by the Osterfeld colliery. From 1932 the Osterfeld colliery was expanded into a large mine. On February 1, 1933, the Sterkrade colliery with the Hugo shaft was taken over. The Sterkrade colliery was taken out of production in March 1933. The coal mined in the Sterkrade field was transported underground to the Osterfeld colliery, where it was brought to the surface. The Osterfeld 1 to 3 shafts were retained as conveyor shafts, the Sterkrade 1 and Sterkrade 2 shafts, the Hugo shaft and the Osterfeld 4 shaft were responsible for the cableway, ventilation and material transport.

Even underground after 1933, more modern equipment was continuously used. The coals were removed from the seams with a pick hammer , and where harder coals were pending, cutting machines were used. The coal extracted was conveyed to the loading points with vibrating chutes and steel link belts. Thanks to these more modern techniques, it was possible to increase the mining output in the mine’s seven operations to 560 tons per day. In 1935 the digging of shaft 4 began. In 1936 the 5th level was set at a depth of 780 meters (−740 m above sea level). In 1938, the 5th level was set in the Sterkrade 1 shaft at the same depth. Due to the increase in production in the German hard coal mining industry, the economic situation in Germany improved. A further increase was not possible at that time with the state of mining technology and could only be achieved with more workers. For this reason, on April 1, 1938, the Nazi regime introduced the so-called "Göring Ordinance", with which working hours were increased from 8¾ to 9¾ hours. Nevertheless, a large number of workers were also lacking at the Osterfeld colliery and despite the increasing number of employees, not all vacant jobs could be occupied.

The second World War

In 1942 a breakthrough was made on the 5th level between the Osterfeld and Sterkrade mine fields . The colliery suffered severe damage in the Second World War . Shaft 3 was hit by a direct bomb on March 26, 1944. The hoisting ropes were torn , as a result of which the hoisting cages fell into the shaft. The debris from the hoisting cages destroyed the shaft installations and the shaft lining . The subsequent repairs lasted until May of the same year. In November of the same year, shaft 3 was hit again in another bomb attack. The headframe was destroyed and fell on the manhole cover. The shaft thus failed for the promotion. In addition, the hoisting machine building with the hoisting machines and the mine fan were completely destroyed in this bombing. On March 24, 1945, the Sterkrade power plant was badly damaged by a bomb hit, which brought operations to the mine to a standstill. On March 30, American troops occupy the Osterfeld colliery. After the end of World War II the mine was badly damaged. Not only shaft 3, but also many company buildings were destroyed.

After the Second World War, the reconstruction of the Osterfeld colliery was initially severely hampered by the regulations of the Allies. Nevertheless, important repairs were carried out in the following months and cleaned up for days. Production was resumed on June 29, 1945. Since many miners tried to provide their families with food on so-called hamster trips due to the food shortage, operations started very slowly. In December of the same year the mine was occupied by English occupation troops. However, even with this measure, the mine could not be brought back to an increased capacity any faster. In October of the same year, the Göring Ordinance was repealed and the eight-hour shift was reintroduced at the mine. In January 1946, shaft 2 was able to go back into production. In 1948, central shaft 3 was re-drilled. The coal washing plant and the coking plant were then renewed. In 1949 the Hugo shaft was renamed to Hugo Daniel shaft. Furthermore, this operating area was outsourced as an independent, but closed operating area.

The destroyed shaft 3 was restored from 1948 to 1950 and put back into operation on May 8, 1950. In honor of the former director of GHH AG Paul Reusch , the shaft was renamed "Paul Reusch shaft". A new mine ventilator was put into operation at the Osterfeld 4 shaft this year. From this point on, shaft 4 took over part of the weather from the Osterfeld colliery. On May 28, 1952, the Osterfeld, Franz Haniel and Jacobi collieries were spun off from the GHH due to a decree of the Allied occupying powers. The mines were transferred to a newly founded company, Bergbau AG Neu Hoffnung. In the mid-1950s, the conveyor systems in Shaft 1 were so technically outdated that they no longer met the requirements. In order to modernize the conveyor systems, from 1956 onwards, most of the ropeway and material transport were made via the Osterfeld 4 shaft. In 1957 the mine was reintegrated into the HOAG.

The coal crisis

For various reasons, sales stagnated in 1957 and, as a result, the coal crisis . Many mines had to be closed, others were modernized to adjust production. Even the Osterfeld colliery was not spared from the coal crisis. In the course of this crisis, the new operating company Hüttenwerke Oberhausen AG (HOAG) undertook extensive measures to concentrate funding. In September 1957, various renovations began. Shaft 1 was equipped with a new type of four-rope vessel conveyor in 1957 . At the same time, a closed winding tower was built over the shaft . The headframe had a height of 72 meters and was clad with anodized aluminum sheets. A 4.4 megawatt electric tower hoisting machine was installed in the tower. There were also numerous modernization measures underground. Friction punches were now used in the struts , which significantly improved the extraction of coal, since a punch-free mining front was now made possible for longwall mining . Extraction at the Osterfeld colliery continued to be carried out using hammers and cutting machines. In 1958, instead of the shaking chute, only scraper chain conveyors were used to convey the coal extracted in the face . In 1959 the Hugo Daniel shaft was put back into operation up to the 5th level. In 1963, the sinking of the northern weather shaft began in the northern field. This shaft was planned for the ventilation of the northern field and was later only called northern shaft. The shaft starting point of the north shaft was in Schmachtendorf. The shaft had a shaft diameter of 7.3 meters and was created using the freezing process. In addition, around 1963 two blind shafts were sunk to reveal the 6th level. The breakthrough took place in 1965 with the Franz Haniel and Jacobi collieries, the north shaft reached the Carboniferous at a depth of 446 meters and the breakthrough with the third level took place at a depth of 530 meters (−474 m above sea level). In 1966 the 5th level was set at a depth of 766 meters (−710 m above sea level), and in 1967 the 6th level was set at a depth of 975 meters (−919 m above sea level). In 1967 the north shaft reached its preliminary final depth at 1020 meters.

In 1968 the Ruhrkohle AG was founded and the mining operations of the HOAG were incorporated into the newly founded Ruhrkohle AG. The Osterfeld colliery was affiliated to "Bergbau AG Oberhausen". This year began to sink the shaft 1 deeper, in addition, the north shaft went into operation. Bergbau AG Oberhausen set new goals for its mines. The Osterfeld colliery should produce an average output of 10,500 tonnes of hard coal per day. These coals should be used to supply the attached coking plant. At that time the mine was producing from two main mining areas. On the one hand from the southern part of the construction site with the Osterfeld 1 to 4 shafts and on the other from the north field with the Hugo Daniel shaft. Based on these requirements, the plant management decided to relocate the entire dismantling to the northern field. The remaining parts of the deposit in the southern field were abandoned. In 1969 shaft 2 was closed and backfilled . At the beginning of the 1970s, special measures were sought to control the rock pressure occurring in the greater depths . In order to be able to better control the pressure on the extension of the line , hydraulically setting building materials were used to backfill the extension segments. In the period from 1971 to 1973 the "Osterfeld 1/3" coking plant was completely renovated. For this purpose, a new coke oven system was installed south of the existing coke batteries. This system consisted of 96 large-capacity ovens that corresponded to the latest environmental standards. The new coking plant went into operation on March 15, 1973. The plant could produce up to 4,300 tons of coke per day. 1974 began to sink the weather shaft 5 deeper and the north shaft finally began its service as a northern cable car system. The 6th level became the main delivery level. In November 1974 a mine fire broke out in a mining operation in the Gustav seam after the mining work was completed . Extinguishing work was carried out immediately by the mine rescue team. For this purpose were dismantling routes dammed and the fire was inerting of nitrogen suffocated. The measures were so successful that just four weeks later the neighboring company was able to start mining without risk.

In 1975 shaft 5 was penetrated with the 6th level. The coal mined was now conveyed from the north shaft to the Osterfeld shafts via an eleven-kilometer large belt system. In 1977 the 7th level was aligned in the Osterfeld 5/6 construction site over a conveyor mountain . The 7th level, also called the 1200 meter level, was at a depth of 1250 meters (−1210 m above sea level). A start was made to dig the weather shaft 8 (north shaft) deeper. In 1979 the 7th level was set in Weather Shaft 8 at a depth of 1252 meters (−1196 m above sea level). The material was transported on the soles by battery and diesel locomotives. Monorails and diesel trolleys were used for transport in the seams. Passenger trains were used between the cable car shafts so that the miners could get to and from their workplaces quickly. These trains ran at regular intervals according to a given timetable. Conveyor belts at a speed of 2.5 meters per second were used by the miners for driving along the mining sections . In 1980, the breakthrough occurred in the Osterfeld 1/3 construction site over the Hugoberg with the 7th level of weather shaft 8. In 1981, the 7th level became the main production level and the digging of shaft 6 began. In 1982 the 7th level between shaft 4 and shafts 5 and 6 broke through. In 1983 shaft 6 was open to traffic up to the 7th level. Due to the climatic difficulties in the northern field, a weather cooling machine with a cooling capacity of 7.5 megawatts was put into operation on the northern shaft in 1983 . In order to supply the underground operations with sufficient building material , a central building material supply was installed. In 1984 shaft 4 was equipped with a new headframe. At that time, the mine field covered an area of 44.5 km 2 . Most of the mine field lay under the northern part of the city of Oberhausen. Only in the west and north was the minefield slightly below the areas of the cities of Dinslaken and Duisburg .

The last few years until the shutdown

The worsening sales situation for coking coal and coke led to the gradual decommissioning of the Osterfeld production site from the end of the 1980s . The coking plant was shut down on March 13, 1988. The coking plant's facilities were demolished by autumn 1990. In 1989 Ruhrkohle AG decided to merge the "Osterfeld" colliery with the neighboring Lohberg colliery to form the " Lohberg-Osterfeld mine ". The Osterfeld production site was to be abandoned and the rest of the mine field was to be dismantled from the “Lohberg” mine . This merger was completed on July 1, 1989.

The north field with the north shaft was initially integrated into the mine building of the new composite mine . The coal mined from the Osterfeld construction site was conveyed underground to the Lohberg site via a conveyor belt. This belt line was over five kilometers long and went into operation on January 2, 1992. The conveyor belt was controlled with the latest process control technology, the drive motors were driven by frequency converters. This ensured optimal loading and utilization of the conveyor belts . In October 1993, the wells "Osterfeld" 4 and "Hugo Haniel" were filled in November followed the shafts "Osterfeld" 1 and "Osterfeld" 3. These shafts were with mountain official approval only teilverfüllt. On November 10, 1993, the preparation and on January 12, 1994 the winding tower of the "Osterfeld" 1 shaft was blown up. By the end of the first quarter of 1995, the other daytime facilities of the “Osterfeld 1/3” colliery were demolished, except for the headframe of the “Paul Reusch shaft” and some entrance buildings. The Sterkrade 2 shaft and the pit ventilators were kept in operation until December 1995, after which the shaft was partially filled and the facilities demolished. The operation of the Kaue was closed on March 31, 1998. After the closure of the chews in the Osterfeld operating area, the miners were relocated to the Lohberg operating area. From there, the miners of a mining area were transported by bus to the Osterfeld construction site until May 31, 1998 in order to drive the last mining operation to the end. In 2006 the north shaft was backfilled and the daytime facilities demolished in November 2007. The area was greened again.

Promotion and workforce

The first known production and workforce figures come from 1878, when 213 miners produced 30,000 tons of hard coal. In 1879, 400 miners were already employed at the mine, who produced around 81,000 tons of hard coal. In 1885, 161,977 tons of hard coal were extracted. This promotion was provided by 713 miners. In 1890, 1,083 miners extracted 278,252 tons of hard coal. In 1893, production reached the 500,000 ton mark. In 1895, 525,690 tons of hard coal were extracted. The workforce was 1609 miners. In 1900, 2051 miners extracted 569,415 tons of hard coal. In 1905, 3378 miners extracted 999,500 tons of hard coal. In 1910, production passed the one million mark. With 4844 miners 1,251,754 tons of hard coal were extracted. In 1913, 1,196,848 tons of hard coal were mined by 4,133 miners. When the First World War broke out in 1914, the number of miners underground was halved, and production fell to 2500 tons per working day. In 1915, 3460 miners extracted 763,000 tons of hard coal. From 1916, women were employed in day-to-day production. The underground workforce was increased by prisoners of war. This made it possible for the colliery to produce around 800,000 tons of hard coal again in 1917.

After the First World War, the number of employees rose again, but the number of subsidies fell again. In 1920, 3513 miners extracted 674,149 tons of hard coal. In 1925, around 984,000 tons of hard coal were mined by 3830 miners. In 1930, 2,908 miners extracted 826,784 tons of hard coal. After 1931 almost 2,500 miners were laid off due to the merging of the Hugo and Osterfeld collieries. In 1935, 3,294 miners extracted 1,728,129 tons of hard coal. In 1940, the funding exceeded the 2 million mark. 2,366,733 tons of hard coal are mined by 4,750 miners. This corresponds to an average of 8500 working days. At the end of the Second World War, production sank well below one million tons of hard coal. With 3,522 miners 303,096 tons of hard coal are mined. The production was thus roughly at the level of 1892. In 1950 the production exceeded the one million tons mark again. With 5509 miners, 1,246,475 tons of hard coal were mined. In 1955, 6,381 miners extracted 2,059,436 tons of hard coal. In 1960, 5510 miners extracted 2,063,301 tons of hard coal. In 1965 there was a slight increase in funding, despite a decrease in the number of employees. 4680 miners extracted 2,156,294 tons of hard coal.

In 1970 production sank again below two million tons. With 3,068 miners 1,735,872 tons of hard coal are mined. In 1975 the two million ton mark was exceeded again. 2,375,523 tons of hard coal were mined by 4,538 miners. In 1980, 4,755 miners extracted 2,691,779 tons of hard coal. In 1981, the maximum production of the mine was achieved, it was around 2,800,000 tons of hard coal. A mix of gas, gas flame and fat coal was promoted. The workforce this year was 4836 miners. In 1985, 4088 miners extracted 2,198,852 tons of hard coal. The last known production and workforce figures for the mine are from 1988, with 3720 miners, 2,190,901 tons of hard coal were extracted.

Location of the shafts

Current condition

The Oberhausen State Garden Show 1999 (OLGA for short) was later held on the site of the "Osterfeld 1/3" colliery . The “Osterfeld 4” shaft has been preserved for the time being. Since June 1990 there has been a long argument about the subsequent use of the area around the shaft. The gatehouse and the mixing hall were placed under monument protection. In addition, the office building from 1910 was classified as a mining monument. At the “Sterkrade” colliery, the headframe above the “Sterkrade 1” shaft and the associated shaft hall have been preserved as an industrial monument . From the “Hugo Haniel” shaft, you can only find the shaft cover and two signs in the area. In a meadow near the Ripshorster Bridge on the Rhine-Herne Canal , you can still find the foundations of the former machine warehouse with gates and bricks from the former “Osterfeld” colliery.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar Joachim Huske : Die Steinkohlenzechen in the Ruhr area. Data and facts from the beginning to 2005 (= publications from the German Mining Museum Bochum 144) 3rd revised and expanded edition. Self-published by the German Mining Museum, Bochum 2006, ISBN 3-937203-24-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Fritz Pamp: The Osterfeld colliery; The development up to the association with the Sterkrade colliery in 1933 . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 13, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen December 2009, ISSN 1864-7294 , pp. 4-6.

- ↑ Fr. Frölich: The Gutehoffnungshütte Oberhausen. Second book, The works of the Gutehoffnungshütte according to the status of 1910. In memory of the 100th anniversary 1810-1910

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Wilhelm and Gertrude Hermann: The old collieries on the Ruhr . In: The Blue Books . 6th edition, expanded to include a digression according to p. 216 and updated in energy policy parts, the 5th edition, completely revised. u. extended edition. Langewiesche publishing house , Königstein im Taunus 2008, ISBN 978-3-7845-6994-9 .

- ^ A b Fritz Pamp: Firedamp explosion at the Osterfeld colliery . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 3, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen April 2007, ISSN 1864-7294 , pp. 4-5.

- ↑ a b c Joachim Huske: The hard coal mining in the Ruhr area from its beginnings to the year 2000. 2nd edition. Regio-Verlag Peter Voß, Werne 2001, ISBN 3-929158-12-4 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Fritz Pamp: The mine Osterfeld; The development of the mine until 1974 . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 14, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen March 2010, ISSN 1864-7294 , pp. 4-6.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Fritz Pamp: The Osterfeld colliery; The development of the mine up to its closure in 1992 . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 15, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen June 2010, ISSN 1864-7294 , pp. 4-6.

- ↑ a b Fritz Pamp: The Osterfeld colliery; The development of the coking plant . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 16, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen September 2010, ISSN 1864-7294 , p. 6.

- ↑ North shaft blossoms . In: WAZ media group. (Ed.): WAZ. from March 5, Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitungsverlagsgesellschaft E. Brost & J. Funke, Essen September 2012. (online)

- ^ Thomas Parent: The Ruhr area; From the golden middle ages to industrial culture. 5th edition. DuMont Reiseverlag, Ostfildern 2011, ISBN 978-3-7701-3159-4 .

- ^ Fritz Pamp: Shaft IV between Tackenberg and Klosterhard . In: Osterfelder Bürgerring. (Ed.): Der Kickenberg, Osterfelder Heimatblatt. No. 1, Walter Perspektiven, Oberhausen September 2006, ISSN 1864-7294 , p. 14.

- ↑ Hugo Haniel colliery. zechensuche.de, accessed on September 1, 2013 (photos).

Web links

- Detailed history of the Osterfeld colliery (last accessed on December 6, 2012)

- Description of this sight on the Route of Industrial Culture (last accessed on December 6, 2012)

- Action Schachtes IV by the DIE LINKE.LISTE parliamentary group (last accessed on December 6, 2012)

- Osterfeld IV picture gallery on LostAreas

- Osterfeld coking plant, description and picture gallery