Crawley

Borough of Crawley | |

|---|---|

| Queen's Square, a large pedestrianised shopping area in the town centre Queen's Square, a large pedestrianised shopping area in the town centre | |

| Motto(s): "I Grow and I Rejoice" | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Ceremonial county | West Sussex |

| Admin HQ | Crawley |

| Founded | 5th century |

| Borough status | 1974 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough |

| • Governing body | Crawley Borough Council |

| • MP: | Laura Moffatt (L) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.36 sq mi (44.96 km2) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Total | (Ranked ) |

| • Density | 5,750/sq mi (2,221/km2) |

| • Ethnicity (2001 Census) | 88.5% White 8.3% S.Asian 1.1% Afro-Carib. |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| Postcode | |

| Area code | 01293 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-WSX (West Sussex) |

| ONS code | 45UE |

| OS grid reference | TQ268360 |

| NUTS 3 | UKJ24 |

| Website | www.crawley.gov.uk |

Crawley () is a town and local government district with Borough status in West Sussex, England. It is 28 miles (45 km) south of London, 18 miles (29 km) north of Brighton and Hove, and 32 miles (51 km) northeast of the county town of Chichester, covers an area of 17.36 square miles (44.96 km2) and had a population of 99,744 at the time of the 2001 Census.

The area has been inhabited since the Stone Age, and was a centre of iron-making in Roman times. Crawley developed slowly as a market town from the 13th century, serving the surrounding villages in the Weald; its location on the main road from London to Brighton brought a steady passing trade, encouraging the development of coaching inns. It was connected to the railway network in the 1840s. Gatwick Airport, now one of Britain's busiest international airports, opened on the edge of the town in the 1940s, encouraging commercial and industrial growth. After the Second World War, the British Government planned to move large numbers of people and jobs out of London and into new towns around South East England. The New Towns Act 1946 designated Crawley as the site of one of these.[1] A master plan was developed for the establishment of new residential, commercial, industrial and civic areas, and continuous rapid development greatly increased the size and population of the town in a few decades.

The town comprises 13 residential neighbourhoods based around the core of the old market town, and separated by main roads and railway lines. The nearby communities of Ifield, Pound Hill and Three Bridges were absorbed into the new town at different stages of its development. As of 2008, expansion is planned in the west and northwest of the town, in co-operation with Horsham District Council.[2] Economically, the town has developed into the main centre of industry and employment between London and the south coast of England. A large industrial area supports various industries and services, many of which are connected with the airport, and the commercial and retail sectors continue to expand.[1]

History

Origins

The area may have been settled during the Mesolithic period: locally manufactured flints of the Horsham Culture type have been found to the southwest of the town. Tools and burial mounds from the Neolithic period, and burial mounds and a sword from the Bronze Age, have also been discovered.[3][4] Crawley is on the western edge of the High Weald, which produced iron for more than 2,000 years from the Iron Age onwards.[5] Goffs Park—now a recreational area in the south of the town—was the site of two late Iron Age furnaces.[6] Ironworking and mineral extraction continued throughout Roman times, particularly in the Broadfield area where many furnaces were built.[3][7]

In the 5th century, Saxon settlers named the area Crow's Leah—meaning a crow-infested clearing, or Crow's Wood[4]—although the name changed considerably over time. The present spelling appeared by the early 14th century.[3] By this time, nearby settlements were more established: the Saxon church at Worth, for example, dates from between 950 and 1050 AD.[8]

Although Crawley itself is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, the nearby settlements of Ifield and Worth are recorded.[9] The first written record of Crawley dates from 1202, when a licence was issued by King John for a weekly market on Wednesdays.[10] Crawley grew slowly in importance over the next few centuries, but was boosted in the 18th century by the construction of the turnpike road between London and Brighton. When this was completed in 1770, travel between the newly fashionable seaside resort and London became safer and quicker, and Crawley (located approximately halfway between the two) prospered as a coaching halt.[11] By 1839 it offered almost an hourly service to both destinations.[4][12] The George, a timber-framed house dating from the 15th century, expanded to become a large coaching inn, taking over adjacent buildings. Eventually an annexe had to be built in the middle of the wide High Street; this survived until the 1930s.[13] The original building has become the George Hotel, with conference facilities and 84 bedrooms; it retains many period features including an iron fireback.[14][15]

Crawley's oldest church is St John the Baptist's, between the High Street and the Broadway. It has 13th century origins,[16] but there has been much rebuilding (especially in the 19th century) and the oldest part remaining is the south wall of the nave, which is believed to be 14th century. The church has a 15th-century tower (rebuilt in 1804) which originally contained four bells cast in 1724. Two were replaced by Thomas Lester of London in 1742; but in 1880 a new set of eight bells were cast and installed by the Croydon-based firm Gillett, Bland & Company.[17][18][19]

Railway age and Victorian era

The Brighton Main Line was the first railway line to serve the Crawley area. A station was opened at Three Bridges (originally known as East Crawley)[20] in the summer of 1841. Crawley railway station, at the southern end of the High Street, was built in 1848 when the Horsham branch was opened from Three Bridges to Horsham. A line was built eastwards from Three Bridges to East Grinstead in 1855. Three Bridges had become the hub of transport in the area by this stage: one-quarter of its population was employed in railway jobs by 1861 (mainly at the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway's railway works near the station).[21] The locally famous Longley company—one of South East England's largest building firms in the late 19th century, responsible for buildings including Christ's Hospital school and the King Edward VII Sanatorium in Midhurst—moved to a site next to Crawley station in 1881.[22] In 1898 more than 700 people were employed at the site.[23]

There was a major expansion in housebuilding in the late 19th century. An area known as "New Town" (unrelated to the postwar developments) was created around the railway level crossing and down the Brighton Road;[4][21] the West Green area, west of the High Street on the way to Ifield, was built up; and housing spread south of the Horsham line for the first time, into what is now Southgate. The population reached 4,433 in 1901, compared to 1,357 a century earlier.[24] In 1891, a racecourse was opened on farmland at Gatwick. Built to replace a steeplechase course at Waddon near Croydon in Surrey, it was used for both steeplechase and flat racing, and held the Grand National during the years of the First World War.[3] The course had its own railway station on the Brighton Main Line.[25]

In the early 20th century, many of the large country estates in the area, with their mansions and associated grounds and outbuildings, were split up into smaller plots of land, attracting haphazard housing development and small farms.[21] By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Crawley had grown into a small but prosperous town, serving a wide rural area as well as its own population and those passing through on the A23 London–Brighton road. Three-quarters of the population had piped water supplies, all businesses and homes had electricity, and piped gas and street lighting had been in place for 50 years.[21] An airfield was opened in 1930 on land near the racecourse. This was a private concern until the Second World War when it was claimed by the Royal Air Force.[3]

New Town

In May 1946, the New Towns Act 1946 identified Crawley as a suitable location for a New Town;[1] but it was not officially designated as such until 9 January 1947.[26] The 5,920 acres (2,396 ha) of land set aside for the new town were split across the county borders between East Sussex, West Sussex and Surrey. Architect Thomas Bennett was appointed chairman of the Development Corporation for the town. A court challenge to the designation order meant that plans were not officially confirmed until December 1947. By this time, an initial plan for the development of the area had been drawn up by Anthony Minoprio.[27] This proposed filling in the gaps between the villages of Crawley, Ifield and Three Bridges.[28] Bennett estimated that planning, designing and building the town, and increasing its population from the existing 9,500 to 40,000, would take 15 years.[29]

Work began almost immediately to prepare for the expansion of the town. A full master plan was in place by 1949. This envisaged an increase in the population of the town to 50,000, residential properties in nine neighbourhoods radiating from the town centre, and a separate industrial area to the north.[27] The neighbourhoods would consist mainly of three-bedroom family homes, with a number of smaller and larger properties. Each would be built around a centre with shops, a church, a public house, a primary school and a community centre.[28] Secondary education was to be provided at campuses at Ifield Green, Three Bridges and Tilgate.[30] Later, a fourth campus, in Southgate, was added to the plans.[31]

At first, little development took place in the town centre, and residents relied on the shops and services in the existing high street. The earliest progress was in West Green, where new residents moved in during the late 1940s. In 1950 the town was visited by the then heir to the throne, Princess Elizabeth, when she officially opened the Manor Royal industrial area. Building work continued throughout the 1950s in West Green, Northgate and Three Bridges, and later in Langley Green, Pound Hill and Ifield. In 1956, land at "Tilgate East" was allocated for housing use, eventually becoming the new neighbourhood of Furnace Green.[27]

Expectations of the eventual population of the town were revised upwards several times. The 1949 master plan had allowed for 50,000 people, but this was amended to 55,000 in 1956 after the Development Corporation had successfully resisted pressure from the Minister for Town and Country Planning to accommodate 60,000. Nevertheless, plans dated 1961 anticipated growth to 70,000 by 1980, and by 1969 consideration was given to an eventual expansion of up to 120,000.[27]

Extended shopping facilities to the east of the existing high street were eventually provided. The first stage to open was The Broadwalk in 1954, following by the official opening of the Queen's Square development by Her Majesty The Queen in 1958. Crawley railway station was moved eastwards towards the new development.[27]

By April 1960, when Thomas Bennett made his last presentation as chairman of the Development Corporation, the town's population had reached 51,700; 2,289,000 square feet (212,700 m2) of factory and other industrial space had been provided; 21,800 people were employed, nearly 60% of whom worked in manufacturing industry; and only seventy people were registered as unemployed. The corporation had built 10,254 houses, and private builders provided around 1,500 more. Tenants were by then permitted to buy their houses, and 440 householders had chosen to do so by April 1960.[29]

A new plan was put forward by West Sussex County Council in 1961. This proposed new neighbourhoods at Broadfield and Bewbush, both of which extended outside the administrative area of the then Urban District Council. Detailed plans were made for Broadfield in the late 1960s; by the early 1970s building work had begun. Further expansion at Bewbush was begun in 1974, although development there was slow. The two neighbourhoods were both larger than the original nine: together, their proposed population was 23,000. Work also took place in the area now known as Ifield West on the western fringes of the town.[32]

By 1980, the council identified land at Maidenbower, south of the Pound Hill neighbourhood, as being suitable for another new neighbourhood, and work began in 1986. However, all of this development was undertaken privately, unlike the earlier neighbourhoods in which most of the housing was owned by the council.[32]

In 1999, plans were announced to develop a 14th neighbourhood on land at Tinsley Green to the northeast of the town. However, these were halted when proposals for possible expansion at Gatwick Airport were announced.[33] As of 2008, discussions are underway with Horsham District Council concerning the possible future provision of new housing on Crawley's western fringes; much of the land proposed for development currently lies within Horsham's administrative boundaries.[2]

Governance

Crawley Urban District Council was formed in May 1956 from the part of the Horsham Rural District which covered the new town.[34] The Local Government Act 1972 led to the district being reformed as a borough in April 1974,[35] gaining a mayor for the first time.[36]

The Urban District Council received its coat of arms from the College of Heralds in 1957. After the change to borough status a modified coat of arms, based on the original, was awarded in 1976, and presented to the council on 24 March 1977. It features a central cross on a shield, representing the town's location at the meeting point of north–south and east–west roads. The shield bears nine martlets representing both the county of Sussex and the new town's original nine neighbourhoods. Supporters, of an eagle and a winged lion, relate to the significance of the airport to the locality. The motto featured is I Grow and I Rejoice—a translation of a phrase from the Epistulae of Seneca the Younger.[35]

Initially the district (and then borough) council worked with the Commission for New Towns on many aspects of development; but in 1978 many of the commission's assets, such as housing and parks, were surrendered to the council. The authority's boundaries were extended in 1983 to accommodate the Bewbush and Broadfield neighbourhoods.[37]

The borough remains part of the local two-tier arrangements, with services shared with West Sussex County Council. The authority is divided into 15 wards, each of which is represented by two or three local councillors, forming a total council of 37 members. Most wards are coterminous with the borough's neighbourhoods, but two neighbourhoods are divided: Broadfield into North and South wards, and Pound Hill into "Pound Hill North" and "Pound Hill South and Worth". The council is elected in thirds.[38]

As of the 2008 local elections, the authority is Conservative-controlled, with seats allocated as follows:

| Political Party | Seats held |

|---|---|

| Conservative | 26 |

| Labour | 9 |

| Liberal Democrat | 2 |

The party gained control in May 2006 for the first time since the borough was created. Previously the authority had always been Labour controlled.[39]

Crawley Borough is coterminous with the parliamentary constituency of Crawley. The current Member of Parliament for the constituency is Laura Moffatt, a member of the Labour Party and the Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for Health, Alan Johnson.[40][41] In the 2005 General Election, the winning margin was the slimmest of any UK constituency: Laura Moffatt won by just 37 votes.[42]

Since 1973, Crawley has been twinned with Dorsten, Germany.[43]

Geography

At 51°6′33″N 0°11′14″W / 51.10917°N 0.18722°WInvalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function (51.1092, -0.1872), Crawley is in the northeastern corner of West Sussex in South East England, 28 miles (45 km) south of London and 18 miles (29 km) north of Brighton and Hove. It is surrounded by smaller towns including Horley, Redhill, Reigate, Dorking, Horsham, Haywards Heath and East Grinstead.[44] The borough of Crawley is bordered by the West Sussex local authority areas of Mid Sussex and Horsham districts, and the Mole Valley and Tandridge districts and the Borough of Reigate and Banstead in the county of Surrey.[45][46]

Crawley lies in the Weald between the North and South Downs. Two beds of sedimentary rock meet beneath the town: the eastern neighbourhoods and the town centre lie largely on the sandstone Hastings Beds, while the rest of the town is based on Weald Clay.[47][48] A geological fault running from east to west has left an area of Weald Clay (with a ridge of limestone) jutting into the Hastings Beds around Tilgate.[48] The town has no major waterways, although a number of smaller brooks and streams are tributaries for the River Mole which rises near Gatwick Airport and flows northwards to the River Thames near Hampton Court Palace. There are several lakes at Tilgate Park and a mill pond at Ifield which was stopped to feed the Ifield Mill.[49]

In 1822 Gideon Mantell, an amateur fossil collector and palaeontologist, discovered teeth, bones and other remains of what he described as "an animal of the lizard tribe of enormous magnitude", in Tilgate Forest on the edge of Crawley. He announced his discovery in an 1825 scientific paper, giving the creature the name Iguanodon.[50] In 1832 he discovered and named the Hylaeosaurus genus of dinosaurs after finding a fossil in the same forest.[51]

Climate

Crawley has a temperate climate in common with most areas of Great Britain: its Koppen climate classification is Cfb. Its mean annual temperature of 9.6 °C is similar to that experienced throughout the Weald, and slightly cooler than nearby areas such as the Sussex coast and Greater London.[52] Rainfall is considerably below England's average (1971–2000) level of 838 mm, and every month is drier overall than the England average.[53]

The nearest weather station is at Gatwick Airport.

| Template:Climate of Crawley and Gatwick |

Neighbourhoods and areas

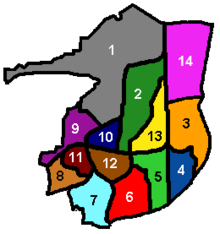

There are 13 residential neighbourhoods,[54] each with a variety of housing types: terraced, semi-detached and detached houses, low-rise flats and bungalows. There are no residential tower blocks. Many houses have their own gardens and are set back from roads. Each neighbourhood is based around a shopping parade, community centre and church, and has a school and recreational open spaces.[32] The Development Corporation's intention was for neighbourhood shops to cater only to basic needs, and for the town centre to be used for most shopping requirements. The number of shop units provided in the neighbourhood parades reflected this: despite the master plan making provision for at least 20 shops in each neighbourhood,[55] the number actually built ranged from 19 in the outlying Langley Green neighbourhood to just seven in West Green, close to the town centre.[29]

Each of the 13 residential neighbourhoods is identified by a colour, which is shown on street name signs in a standard format throughout the town: below the street name, the neighbourhood name is shown in white text on a coloured background.[56]

| Number on map |

Name | Colour | Construction commenced[32] |

Population[57] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Langley Green | Grey | 1952 | 7,286 |

| 2 | Northgate | Dark Green | 1951 | 4,407 |

| 3 | Pound Hill | Orange | 1953 | 14,716 |

| 4 | Maidenbower | Blue | 1987 | 8,070 |

| 5 | Furnace Green | Light Green | 1960 | 5,734 |

| 6 | Tilgate | Red | 1955 | 6,198 |

| 7 | Broadfield | Sky Blue | 1969 | 12,666 |

| 8 | Bewbush | Light Brown | 1975 | 9,081 |

| 9 | Ifield | Purple | 1953 | 8,414 |

| 10 | West Green | Dark Blue | 1949 | 4,404 |

| 11 | Gossops Green | Maroon | 1956 | 5,014 |

| 12 | Southgate | Brown | 1955 | 8,106 |

| 13 | Three Bridges | Yellow | 1952 | 5,648 |

There are areas which are not defined as neighbourhoods but which are closely associated with Crawley:

- The Manor Royal industrial estate is in the north of the town. Although it is part of the Northgate ward, it is allocated a colour: its street name signs feature the word "INDUSTRIAL" on a black background.

- Crawley's town centre is in the southernmost part of Northgate. Its street name signs do not follow the standard format of the neighbourhood signs, but display only the street name.

- Gatwick Airport was built on the site of a manor house, Gatwick Manor, close to the village of Lowfield Heath. Most of the village was demolished when the airport expanded, but some buildings, including the Grade II*-listed St Michael's church,[58] remain. These lie on the airport's southern boundary, between the perimeter road and the A23 close to Manor Royal. In the picture, the road to the left, Old Brighton Road South, is truncated abruptly at the airport boundary, a short distance from the runway.

- Worth was originally a village with its own civil parish, lying just beyond the eastern edge of the Crawley urban area and borough boundary;[59] but development of the Pound Hill and Maidenbower neighbourhoods has filled in the gaps, and the borough boundary has been extended to include the whole of the village. The civil parish of Worth remains, albeit reduced in size, as part of the Mid Sussex district.

Demography

| Year | Population[24] |

|---|---|

| 1901 | 4,433 |

| 1921 | 5,437 |

| 1941 | 7,090 |

| 1961 | 25,550 |

| 1981 | 87,865 |

| 2001 | 99,744 |

At the last census in 2001 the population of Crawley was recorded as 99,744.[60] This accounted for 13.2% of the population of the county of West Sussex. The growth in population of the new town—around 1,000% between 1951 and 2001[24]—has outstripped that of most similar-sized settlements. For example, in the same period, the population of the neighbouring district of Horsham grew by just 99%.[61]

The borough has a younger and more ethnically diverse population than that of West Sussex as a whole. Approximately 64.5% of the population is aged below 45, compared to 55% of the population of West Sussex, and 15.5% of people are from an ethnic background other than White British, compared to just 6.5% throughout the county. People of Indian and Pakistani origin account for 4.5% and 3% of the population respectively.[62][63]

The borough has a population density of around 22 persons per hectare[64] (54 persons per acre), making it the second most densely populated district in West Sussex, after Worthing. The social mix is similar to the national norm: around 50% are in the ABC1 social category,[65] although this varies by ward, with just 44% in Broadfield North[66] compared to 75% in Maidenbower.[67]

The proportion of people in the borough with higher education qualifications is lower than the national average. Around 14% have a qualification at level 4 or above, compared to 20% nationally.[68]

Economy

| Labour Profile[69] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total employee jobs | 79,700 | |

| Full-time | 58,100 | 72.9% |

| Part-time | 21,600 | 27.1% |

| Manufacturing | 7,500 | 9.4% |

| Construction | 1,800 | 2.2% |

| Services | 70,100 | 87.9% |

| Distribution, hotels & restaurants | 19,600 | 24.6% |

| Transport & communications | 23,900 | 30.0% |

| Finance, IT, other business activities | 15,400 | 19.3% |

| Public admin, education & health | 9,600 | 12.1% |

| Other services | 1,600 | 2.0% |

| Tourism-related | 6,600 | 8.3% |

Crawley originally traded as a market town. The Development Corporation intended to develop it as a centre for manufacturing and light engineering, with a dedicated and purpose-built industrial zone.[55] The rapid growth of Gatwick Airport provided opportunities for businesses in the aviation, transport, warehousing and distribution industries. The significance of the airport to local employment and enterprise was reflected by the formation of the Gatwick Diamond partnership. This venture, supported by local businesses, local government and SEEDA, South East England's Regional Development Agency, aims to maintain and improve the Crawley and Gatwick area's status as a region of national and international economic importance.[70]

Since the Second World War, unemployment in Crawley has been low: the rate was 1.47% of the working-age population in 2003.[71] During the boom of the 1980s the town boasted the lowest level of unemployment in the UK.[72] Continuous growth and investment have made Crawley one of the most important business and employment centres in the South East England region.[1]

Manufacturing industry

Crawley was already a modest industrial centre by the end of the Second World War. Building was an important trade: 800 people were employed by building and joinery firms, and two—Longley's and Cook's—were large enough to have their own factories.[21] In 1949, 1,529 people worked in manufacturing: the main industries were light and precision engineering and aircraft repair. Many of the jobs in these industries were highly skilled.[21][55]

Industrial development had to take place relatively soon after the new town was established because part of the Corporation's remit was to move people and jobs out of an overcrowded and war-damaged London. Industrial jobs were needed as well as houses and shops to create a balanced community where people could settle.[73] The Development Corporation wanted the new town to support a large and mixed industrial base, with factories and other buildings based in a single zone rather than spread throughout the town. A 267-acre (108 ha)[73] site in the northeastern part of the development area was chosen. Its advantages included flat land with no existing development; proximity to the London–Brighton railway line, the A23 and the planned M23; space for railway sidings (which were eventually built on a much smaller scale than envisaged); and an adjacent 44-acre (18 ha) site reserved for future expansion, on the other side of the railway line (again, not used for this purpose in the end). Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) opened the first part of the industrial area on 25 January 1950;[10] its main road was named Manor Royal, and this name eventually came to refer to the whole estate.[55]

The Corporation stipulated that several different manufacturing industries should be developed, rather than allowing one sector or firm to dominate. It did not seek to attract companies by offering financial or other incentives; instead, it set out to create the ideal conditions for industrial development to arise naturally, by providing large plots of land with room for expansion, allowing firms to build their own premises or rent ready-made buildings, and constructing a wide range of building types and sizes.[21][55]

Despite the lack of direct incentives, many firms applied to move to the Manor Royal estate: it was considered such an attractive place to relocate to that the Development Corporation was able to choose between applicants to achieve the ideal mix of firms, and little advertising or promotion had to be undertaken. One year after Manor Royal was opened, eighteen firms were trading there, including four with more than 100 employees and one with more than 1,000.[55] By 1964, businesses which had moved to the town since 1950 employed 16,000 people; the master plan had anticipated between 8,000 and 8,500. In 1978 there were 105 such firms, employing nearly 20,000 people between them.[21][55]

Service industry and commerce

While most of the jobs created in the new town's early years were in manufacturing, the tertiary sector developed strongly from the 1960s. The Manor Royal estate, with its space, proximity to Gatwick and good transport links, attracted airport-related services such as logistics, catering, distribution and warehousing; and the Corporation and private companies built many offices throughout the town. Office floorspace in the town increased from 55,000 square feet (5,100 m2) in 1965 to a conservative estimate of 453,000 square feet (42,100 m2) in 1984.[55] Major schemes during that period included premises for the Westminster Bank (later part of NatWest), British Caledonian, and The Office of the Paymaster-General—a government ministry within the remit of HM Treasury.[55] The five-storey Overline House above the railway station, completed in 1968, is used by Crawley's NHS Primary Care Trust and various other companies.[74][75]

Major employers based in the town as of 2008 include Thales Group, Unilever, Doosan Babcock Energy, GlaxoSmithKline, Virgin Atlantic Airways and its associated travel agency Virgin Holidays, Barclaycard and the Office of the Paymaster-General. British Airways took over British Caledonian's headquarters near the Manor Royal estate, renamed it "Astral Towers" and based its British Airways Holidays and AIRMILES divisions there.[76][77]

Shopping and retail

Even before the new town was planned, Crawley was a retail centre for the surrounding area: there were 177 shops in the town in 1948,[21] 99 of which were on the High Street.[55] Early new town residents relied on these shopping facilities until the Corporation implemented the master plan's designs for a new shopping area on the mostly undeveloped land east of the High Street and north of the railway line.[73] The Broadwalk and its 23 shops were built in 1954, followed by the Queen's Square complex and surrounding streets in the mid-1950s.[32] Queen's Square, a pedestrianised plaza surrounded by large shops and linked to the High Street by The Broadwalk, was officially opened in 1958 by Queen Elizabeth II.[21] The town centre was completed by 1960, by which time Crawley was already recognised as an important regional, rather than merely local, shopping centre.

In the 1960s and 1970s, large branches of Tesco, Sainsbury's and Marks & Spencer were opened (the Tesco superstore was the largest in Britain at the time). The shopping area was also expanded southeastwards from Queen's Square: although the original plans of 1975 were not implemented fully, several large shop units were built and a new pedestrianised link—The Martlets—was provided between Queen's Square and Haslett Avenue, the main road to Three Bridges.[55] The remaining land between this area and the railway line was sold for private development by 1982;[55] in 1992 a 450,000 square feet (41,800 m2)[78] shopping centre named County Mall was opened there.[79] Its stores includes major retailers such as Debenhams, Boots, W H Smith and British Home Stores as well as over 80 smaller outlets.[80] The town's main bus station was redesigned, roads including the main A2220 Haslett Avenue were rerouted, and some buildings at the south end of The Martlets were demolished to accommodate the mall.

A regeneration strategy for the town centre, "Centre Vision 2000", was produced in 1993.[81] Changes brought about by the scheme have included 50,000 square feet (4,600 m2) of additional retail space in Queen's Square and The Martlets, and a mixed-use development at the southern end of the High Street on land formerly occupied by Robinson Road (which was demolished) and Spencers Road (shortened and severed at one end). An ASDA superstore, opened in September 2003, forms the centrepiece.[82] Robinson Road, previously named Church Road, had been at the heart of the old Crawley: a century before its demolition, its buildings included two chapels, a school, a hospital and a post office.[83]

There are plans to expand Crawley's central shopping area northwards on to land currently occupied by the Town Hall and office buildings. The borough council's premises would be moved to a new site—possibly the land currently occupied by Sussex House on the High Street—and The Boulevard would become a large pedestrianised shopping area.[84][85] A 255,000 square feet (23,700 m2) John Lewis department store, to be opened in 2013, would be the anchor store. The scheme, named "Town Centre North", is designed to make Crawley a major regional shopping destination.[86]

Public services

Policing in Crawley is provided by Sussex Police. The borough forms part of the North Downs division,[87] and is itself divided into three areas for the purposes of neighbourhood policing: Crawley East, Crawley West, and Crawley Town Centre.[88] A separate division covers Gatwick Airport.[87] There is a police station in the town centre, open for 16 hours a day.[89] Statutory emergency fire and rescue services are provided by the West Sussex Fire and Rescue Service which operates a fire station in the town centre.[90] The South East Coast Ambulance Service is responsible for ambulance and paramedic services.[91]

Crawley Hospital in West Green is operated by West Sussex Primary Care Trust. Some services are provided by the Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, including a 24-hour walk-in centre for non-life threatening injuries.[92] The Surrey and Sussex has been judged as "weak" by the Healthcare Commission.[93]

Thames Water is responsible for all waste water and sewerage provision. Residents in most parts of Crawley receive their drinking water from Southern Water; areas in the north of the town around Gatwick Airport are provided by Sutton & East Surrey Water; and South East Water supplies Maidenbower.[94]

EDF Energy Networks is the Distribution Network Operator responsible for electricity.[95] Gas is supplied by Southern Gas Networks who own and manage the South East Local Distribution Zone.[96]

The provision of public services was made in co-operation with the local authorities as the town grew in the 1950s and 1960s. They oversaw the opening of a fire station in 1958, the telephone exchange, police station and town centre health clinic in 1961 and an ambulance station in 1963. Plans for a new hospital on land at The Hawth were abandoned, however, and the existing hospital in West Green was redeveloped instead.[27] Gas was piped from Croydon, 20 miles (32 km) away, and a gasworks at Redhill, while the town's water supply came from the Weir Wood reservoir south of East Grinstead and another at Pease Pottage.[27][97]

Transport

Crawley's early development as a market town was helped by its location on the London–Brighton turnpike. The area was joined to the railway network in the mid-19th century; and since the creation of the new town, there have been major road upgrades (including a motorway link), a guided bus transit system and the establishment of an airport which has become one of Britain's largest and busiest.

Road

The London–Brighton turnpike ran through the centre of Crawley, forming the High Street and Station Road. When Britain's major roads were classified by the British government's Ministry of Transport between 1919 and 1923,[98] it was given the number A23. It was bypassed by a new dual carriageway in 1939 (which forms the A23's current route through the town), and then later to the east side of the town by the M23 motorway, which was opened in 1975. This connects London's orbital motorway, the M25, to the A23 at Pease Pottage, at the southern edge of Crawley's built-up area. The original single-carriageway A23 became the A2219.

The M23 has junctions in the Crawley area at the A2011/A264 (Junction 10) and Maidenbower (Junction 10A). The end of the motorway at Pease Pottage is Junction 11. The A2011, another dual-carriageway, joins the A23 in West Green and provides a link, via the A2004, to the town centre. The A2220 follows the former route of the A264 through the town, linking the A23 directly to the A264 at Copthorne, from where it then runs to East Grinstead.

Rail

The first railway line in the area was the Brighton Main Line, which opened as far as Haywards Heath on 12 July 1841 and reached Brighton on 21 September 1841. It ran through Three Bridges, which was then a small village east of Crawley, and a station was built to serve it.[99]

A line to Horsham, now part of the Arun Valley Line, was opened on 14 February 1848. A station was provided next to Crawley High Street from that date.[100] A new station was constructed slightly to the east, in conjunction with the Overline House commercial development, and replaced the original station which closed on 28 July 1968. The ticket office and Up (London-bound) platform waiting areas form the ground floor of the office building.[101]

Ifield railway station is now within the Crawley urban area. Opened as Lyons Crossing Halt on 1 June 1907 to serve the village of Ifield, it was soon renamed Ifield Halt, dropping the "Halt" suffix in 1930.[102]

Regular train services run from Crawley to London Victoria and London Bridge stations, Gatwick Airport, Croydon, Tunbridge Wells, Horsham, Bognor Regis, Chichester, Portsmouth and Southampton. Three Bridges has direct links with Brighton.[103][104]

Bus and Fastway

Crawley was one of several towns where the boundaries of Southdown Motor Services and London Transport bus services met. In 1958 the companies reached an agreement which allowed them both to provide services in all parts of the town. When the National Bus Company was formed in 1969, its London Country Bus Services subsidiary took responsibility for many routes, including Green Line Coaches cross-London services which operated to distant destinations such as Watford, Luton and Amersham. A coach station was opened by Southdown in 1931 on the A23 at County Oak, near Lowfield Heath: it was a regular stopping point for express coaches between London and towns on the Sussex coast. This traffic started to serve Gatwick when the airport began to grow, however.[105] When the National Bus Company was broken up, local services were provided by the new South West division of London Country Bus Services, which later became part of the Arriva group. Metrobus acquired these routes from Arriva in March 2001, and is now Crawley's main operator.[106] It provides local services between the neighbourhoods and town centre, and longer-distance routes to Horsham, Redhill, Tunbridge Wells, Worthing and Brighton.[107]

In September 2003 a guided bus service, Fastway, began operating between Bewbush and Gatwick Airport.[108] A second route, from Broadfield to the Langshott area of Horley, north of Gatwick Airport, was added on 27 August 2005.[109]

Gatwick Airport

Gatwick Airport was licensed as a private airfield in August 1930.[110] It was used during the Second World War as an RAF base, and returned to civil use in 1946. There were proposals to close the airport by the late 1940s, but in 1950 the government announced that it was to be developed as London's second airport.[111] It was closed between 1956 and 1958 for rebuilding. Her Majesty The Queen reopened it on 9 June 1958. A second terminal, the North Terminal, was built in 1988.[112] An agreement exists between BAA plc and West Sussex County Council preventing the building of a second runway until 2019. Nevertheless, consultations were launched in 2002 by the Department for Transport, at which proposals for additional facilities and runways were considered. It was agreed that there would be no any further expansion at Gatwick unless it became impossible to meet growth targets at London Heathrow Airport within existing pollution limits.[113]

Sport and leisure

Crawley Town F.C. are Crawley's main football team. Formed in 1896, they moved in 1949 to a ground at Town Mead adjacent to the West Green playing fields. Demand for land near the town centre led to the club moving in 1997 to the new Broadfield Stadium, now owned by the borough council.[114] As of the 2007/2008 season, Crawley Town play in the Blue Square Premier, the highest level of non-league competition in England. Two other local teams play in the Sussex County Football League: Three Bridges F.C. and Ifield Edwards F.C.. Crawley Rugby Club is based in Ifield,[115] and a golf course was constructed in 1982 at Tilgate Park.[116]

The new town's original leisure centre was in Haslett Avenue in the Three Bridges neighbourhood. Building work started in the early 1960s, and a large swimming pool opened in 1964. The site was extended to include an athletics arena by 1967, and an additional large sports hall was opened by the town mayor, Councillor Ben Clay, and Prime Minister Harold Wilson in 1974.[117] However, the facilities became insufficient for the growing town, even though an annexe was opened in Bewbush in 1984.[118] In 2005, Crawley Leisure Centre was closed and replaced by a new facility, the K2 Leisure Centre, on the campus of Thomas Bennett Community College near the Broadfield Stadium.[119] Opened to the public on 14 November 2005,[117] and officially by Lord (Sebastian) Coe on 24 January 2006, the centre includes the only Olympic-sized swimming pool in South East England.[120] In March 2008 the centre was named as a training site for the 2012 Olympics in London.[121]

The Development Corporation made little provision for the arts in the plans for the new town, and a proposed arts venue in the town centre was never built. Neighbourhood community centres and the Tilgate Forest Recreational Centre were used for some cultural activities,[118] but it was not until 1988 that the town had a dedicated theatre and arts venue, at The Hawth. (The name derives from a local corruption of the word "heath", which came to refer specifically to the expanse of wooded land, south of the town centre, in which the theatre was built.)[122] Crawley's earliest cinema, the Imperial Picture House on Brighton Road, lasted from 1909 until the 1940s; the Embassy Cinema on the High Street (opened in 1938) replaced it.[10][118] A large Cineworld cinema has since opened in the Crawley Leisure Park, which features ten-pin bowling, various restaurants and bars and a fitness centre.[123]

Each neighbourhood has self-contained recreational areas, and there are other larger parks throughout the town. The Memorial Gardens, on the eastern side of Queen's Square, feature art displays, children's play areas and lawns, and a plaque commemorating those who died in two Second World War bombing incidents in 1943 and 1944.[10] Goffs Park in Southgate covers 50 acres (20 ha), and has lakes, boating ponds, a model railway and many other features.[124] Tilgate Park and Nature Centre has walled gardens, lakes, large areas of woodland with footpaths and bridleways, a golfing area and a collection of animals and birds.[125]

Crawley Museum[126] is based in Goffs Park. Stone Age and Bronze Age remains discovered in the area are on display, as well as more recent artefacts including parts of Vine Cottage, an old timber-framed building on the High Street which was once home to former Punch editor Mark Lemon and which was demolished when the ASDA development was built.[10]

Education

Maintained primary and secondary schools were reorganised in 2004 following the Local Education Authority's decision to change the town's three-tier system of first, middle and secondary schools to a more standard primary/secondary divide.[127] Since the restructuring, Crawley has had 17 primary schools (including two Church of England and two Roman Catholic) and four pairs of infant and junior Schools. Most of these were opened in 2004; others changed their status at this date (for example, from a middle to a junior School). Secondary education is provided at one of six secondary schools:

- Ifield Community College

- Hazelwick School

- Holy Trinity Church of England School

- Oriel High School

- St Wilfrid's Catholic School

- Thomas Bennett Community College

Five of these have a sixth form, and one is due to open at Oriel High in September 2008.[128] The schools at Ifield and Thomas Bennett are also bases for the Local Authority's adult education programmes.[129] Pupils with special needs are educated at the two special schools in the town, each of which covers the full spectrum of needs: Manor Green Primary School and Manor Green College.

Further education is provided by Central Sussex College. Opened in 1958 as Crawley Technical College,[130] it merged with other local colleges to form the new institute in August 2005.[131] The college also provides higher education courses in partnership with the universities at Chichester and Sussex. In 2004, a proposal was made for an additional campus of the University of Sussex to be created in Crawley, but as of 2008 no conclusion has been reached.[132]

Media

Crawley has two local newspapers, each with considerable history in the area. The Crawley Observer began life in 1881 as Simmins Weekly Advertiser, became the Sussex & Surrey Courier and then the Crawley and District Observer, and took its current name in 1983.[133] The newspaper is now owned by Johnston Press.[39] The Crawley News was first published in 1979, and later took over the operations of the older Crawley Advertiser which closed in 1982.[118] The newspaper is now owned by the Trinity Mirror group and is a free publication.[134]

The town is served by the London regional versions of BBC and ITV television from the Crystal Palace or Reigate transmitters—although some terrestrial aerials in the town may pick up BBC South and ITV Meridian signals from the Midhurst transmitter.[135]

Radio Mercury began broadcasting on 20 October 1984 from Broadfield House in Crawley.[136] The station, now owned by Gcap Media, broadcasts as Mercury FM from Kelvin Way in Crawley.[137] The group has a sister station, Classic Gold Digital 1521, on the medium wave frequency.[138] Local BBC radio was provided by BBC Radio Sussex from 1983; this became part of BBC Southern Counties Radio following a merger with BBC Radio Surrey in 1994.[139]

Notable people

Mark Lemon, the first editor of satirical magazine Punch, lived at a house in the High Street for many years until his death in 1870. A blue plaque outside the George Hotel commemorates his time in the town.[14] Serial killer John George Haigh, the "Acid Bath Murderer", carried out some of his murders at a workshop in the West Green area after moving to Crawley.[140] The footballers Kevin Muscat (who has played for Australia since 1994 and had a nine-year spell in Britain, playing for four different clubs) and Faye White, the Arsenal and England women's team captain, were born in Crawley,[141][142] while Gareth Southgate (manager of Middlesbrough F.C. and a former England international) attended the town's Hazelwick School.[143] Alan Minter also achieved sporting success: born in Crawley in 1951, he won a bronze medal at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games in the light middleweight boxing category,[144] and in 1980 became the WBC world middleweight champion by beating Vito Antuofermo.[10] Athlete Daley Thompson used facilities in Crawley to train for the Olympics in 1980 and 1984.[145] Rock band The Cure were formed in Crawley in 1976 by Robert Smith, Michael Dempsey and Lol Tolhurst, all of whom attended St Wilfrid's School.[146] The same school also educated drummer Paul Stewart, guitarist Kevin Jeremiah and keyboard player Ciaran Jeremiah, all of the band The Feeling.[147] The 21st Premier of Western Australia Sir Charles Court was born in Crawley, but migrated to Australia with his family before his first birthday.[148] According to the back-story created for the virtual band Gorillaz, the fictional character 2D comes from Crawley.[149]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Select Committee on Transport, Local Government and the Regions: Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence. Supplementary memorandum by Crawley Borough Council (NT 15(a))". United Kingdom Parliament Publications and Records website. The Information Policy Division, Office of Public Sector Information. 2002. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ a b Horsham District Council & Crawley Borough Council (2007). "West and North West of Crawley". West and North West of Crawley website. Horsham District Council. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b c d e "A Brief History of Crawley". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b c d Cole, Belinda (2004). Crawley: A History & Celebration. Salisbury: Frith Book Company Ltd. 1904938191.

- ^ "About The High Weald: The Iron Story". High Weald AONB Unit website. High Weald AONB Unit. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ "Life in Late Iron Age Sussex: Trade & Industry". Romans In Sussex website. The Sussex Archaeological Society. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ "Life in Roman Sussex: Crafts & Industry: Weald Iron Industry". Romans In Sussex website. The Sussex Archaeological Society. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ "Crawley Borough Council: St Nicholas Church". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ "Crawley Borough Council: St Margaret's Church". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Cole, Belinda (text adapted from original material) (2004). Crawley: An Illustrated Miscellany. Salisbury: Frith Book Company Ltd. 1904938744.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter. "Georgian England: the Peaceful Years at Home". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 98. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Pigot's Directory of Sussex. London & Manchester: Pigot. 1839. p. 681. WSC13002.

- ^ "Crawley High Street". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ a b "Crawley Town Walk" (PDF). Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ "The George Hotel". The George Hotel website. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Diocese of Chichester: St John the Baptist, Crawley". A Church Near You website. Oxford Diocesan Publications Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1940). "Parishes: Crawley". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 7: The Rape of Lewes. British History Online. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "St John the Baptist Parish Church, Crawley, West Sussex - 22nd April 2004". The Roughwood website. Mark Collins. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Dove Details". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers website. Sid Baldwin, Ron Johnston and Tim Jackson on behalf of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. 2008-02-24. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David Palmer (2003). "A brief history of Maidenbower" (PDF). Maidenbower Village website. Stuart Cummings. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j

Gray (ed.), Fred. "Crawley in the Twentieth Century". Crawley: Old Town, New Town. Paper No. 18 (Centre for Continuing Education, University of Sussex ed.). Falmer: University of Sussex. pp. 8–40. ISBN 0-904212-21-8.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help); Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Ifield: Economic History". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3. British History Online. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter. "Victorian Prosperity". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 119. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b c "Crawley District: Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter. "Into the Twentieth Century". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 146. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ "No. 37849". The London Gazette. 10 January 1947.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Crawley New Town". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3: Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) including Crawley New Town. British History Online. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b "New Town History". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2005. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Thomas P. (1961). "Crawley after Thirteen Years". Town & County Planning. XXIX (I): 18–20.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "First proposed structure plan, 1947". Nostalgia: A Crawley Observer Supplement (2): 3. 1995.

- ^ The Crawley Development Corporation's Master Plan for Crawley New Town (Map). Crawley Development Corporation. 1949.

- ^ a b c d e Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Growth of the New Town". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3: Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) including Crawley New Town. Victoria County History. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Janet Treagus (2007-05-15). "Council wins fight against new neighbourhood". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gwynne, Peter. "The New Town—Maturity". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 165. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ a b "Coat of Arms". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ "Past Mayors". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Crawley Borough Council (1997). Crawley: Official Guide. Wallington: Local Authority Publishing Co. Ltd.

- ^ "Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Crawley in West Sussex" (PDF). The Boundary Committee for England. 2002. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b "Tories Take Control". Crawley Observer. Johnston Press Digital Publishing. 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "obs" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Laura Moffatt—Labour Member of Parliament for Crawley". Official website of Laura Moffatt MP. The Labour Party. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "Laura Moffatt". Guardian.co.uk Politics website. Guardian News and Media Ltd. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "10 things about the election". BBC News Website: Election 2006. BBC. 2006-05-06. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ian Miller (2006-08-24). "Crawley Town Twinning". Crawley Observer.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Office for National Statistics (2001). "Census 2001: Key Statistics for urban areas in the South East; Map 3" (PDF). statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ "County of West Sussex: Electoral Divisions" (PDF). West Sussex County Council website. West Sussex County Council. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ "Map of Surrey's district and borough councils". Surrey County Council website. Surrey County Council. 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ "Geology of Surrey and Sussex, after Woodward (1904), based on Reynolds (1860; 1889)". Geology of Great Britain—an Introduction with Geological Maps (from the website of Southampton University). Ian West and Tonya West. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ a b Gwynne, Peter. "Crawley's Site and Situation". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ "Ifield Mill Pond". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ Thomson, Keith Stewart (2006). "American Dinosaurs: Who and What Was First". American Scientist. 94 (2): 209. doi:10.1511/2006.58.209.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Discovery of Hylaeosaurus, 1833". The Linda Hall Library, Kansas City website. Linda Hall Library. 2003. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "Mean Temperature Annual Average". Met Office. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Met Office: averages 1971–2000". Met Office website. Met Office. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ "Crawley Borough Council: Crawley's Neighbourhoods". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Crawley New Town: Economic History". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3: Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) including Crawley New Town. British History Online. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ Street Plan of Crawley (Map). 5.6" = 1 mile. Cartography by Ordnance Survey. G.I. Barnett & Sons Ltd. 1970.

{{cite map}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Neighbourhood Statistics". National Statistics website. Office of National Statistics. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ "Lowfield Heath St Michael". The Church of England website. The Archbishops' Council. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Sheet 187: Dorking, Reigate and Crawley (Map). 1:50,000. Landranger Series of Great Britain. Ordnance Survey. 1980.

- ^ "Key Figures for 2001 Census: Census Area Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Horsham District: Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Ethnic Group (UV09) dataset". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Ethnic Group (KS06) dataset". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Population Density (UV02)—Crawley Local Authority". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Approximated Social Grade (UV50)". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Approximated Social Grade (UV50)—Broadfield North Ward". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Approximated Social Grade (UV50)—Maidenbower Ward". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Qualifications (UV24)—Crawley Local Authority". Neighbourhood Statistics website. National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Labour Market Profile: Crawley". Nomis official labour market statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2007-08-02. Data is taken from the ONS annual business inquiry employee analysis and refers to 2005

- ^ "The Gatwick Diamond". Gatwick Diamond website. West Sussex Economic Partnership. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Unemployment" (PDF). Crawley Economic Profile 2004. Crawley Borough Council. 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Debates for 9 Feb 1989". House of Commons Hansard. HMSO. 1989. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ a b c New Towns Act 1946: Reports of the Aycliffe, Crawley, Harlow, Hatfield, Hemel Hempstead, Peterlee, Stevenage and Welwyn Garden City Development Corporations for period ending 31 March 1949, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (published 1949-07-28), 1949

- ^ "NHS: West Sussex PCT". NHS Choices: West Sussex PCT (list of sites). Department of Health. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ "Locallife Crawley". Locallife Crawley: Business directory. Locallife Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ "British Airways Holidays: Booking terms and conditions". British Airways Holidays Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ "About Airmiles". AIRMILES Travel Promotions Ltd, trading as AIRMILES. 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "Propertymall.com: Crawley, County Mall Shopping Centre". www.propertymall.com. MaxiMalls.com Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Christine Ease (2005-02-25). "The magnetic North". www.propertyweek.com. Property Week. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Shopping". www.countymall.co.uk. Standard Life Property. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Town Centre Strategy—Consultation Document" (PDF). Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Town Centre North, Crawley: Retail Assessment" (PDF). Crawley Borough Council website. Grosvenor Investments Ltd. 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bastable, Roger. "Old Crawley". Then & Now: Crawley. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 0-7524-3063-7.

- ^ "Town Centre North". Crawley Borough Council. 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Town Centre North". Grosvenor Estates. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Town Centre North: Shopping". Grosvenor Estates. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ^ a b "Policing Your Neighbourhood: Local Policing". Sussex Police website. Sussex Police. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Sussex Police Online - District Crawley". Sussex Police website. Sussex Police. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Policing Your Neighbourhood—Local Police Stations". Sussex Police website. Sussex Police. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "West Sussex Fire & Rescue Service: Contacts". West Sussex County Council. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "South East Coast Ambulance Service—About Us". Secamb website. South East Coast Ambulance Service. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Crawley Hospital General Information". NHS website. National Health Service. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Mixed marks for South East trusts". BBC News website. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Thames Water Service Area Map" (SWF). Thames Water website. Thames Water. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "National Grid: Distribution Network Operator (DNO) Companies". National Grid website. National Grid. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "National Grid: About the Gas Industry". National Grid website. National Grid. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^

Green, Jeffrey. Crawley New Town in old photographs. Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-0472-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "CBRD In Depth: Road Numbers—How it happened". CBRD website. Chris Marshall. 2001. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Mitchell, Vic (1986). Southern Main Lines: Three Briges to Brighton. Midhurst: Middleton Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-906520-35-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mitchell, Vic (1986). Southern Main Lines: Crawley to Littlehampton. Midhurst: Middleton Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-906520-34-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Body, Geoffrey (1984). PSL Field Guide: Railways of the Southern Region. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. pp. page 75. ISBN 0-85059-664-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Mitchell, Vic (1986). Southern Main Lines: Crawley to Littlehampton. Midhurst: Middleton Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-906520-34-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "West Coastway and Arun Valley: London, East Croydon, Gatwick Airport, Arun Valley & Brighton to Hove, Worthing, Littlehampton, Bognor Regis, Chichester, Portsmouth & Southampton" (PDF). Southern timetable booklet 3 (at Southern website). New Southern Railway Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Brighton Main Line: London, East Croydon, Tonbridge and Redhill to Gatwick Airport, Three Bridges, Crawley and Horsham" (PDF). Southern timetable booklet 2 (at Southern website). New Southern Railway Ltd. 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ Kraemer-Johnson, Glyn (2005). "Old Town, New Town". Southdown Days. Hersham: Ian Allan Publishing. pp. 48–55. ISBN 0-7110-3077-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Acquisition of Crawley Depot". Go Ahead Group website. Go Ahead Group. 2001. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Timetables & Route Index". Metrobus Website. Go Ahead Group. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Fastway: Phase One Service Launched" (PDF). Fastway, Issue 6. West Sussex County Council. 2003. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Fastway information and timetable from 27 August 2005". Fastway leaflet (2005) at West Sussex County Council Roads & Transport website. West Sussex County Council. 2005. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter. "Into the Twentieth Century". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 147. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ Gwynne, Peter. "The New Town—Maturity". A History of Crawley. Chichester: Phillimore & Company. p. 160. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- ^ "Our History". BAA Gatwick Airport website. BAA plc. 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ^ "The future development of air transport in the UK". Department for Transport website. Department for Transport. 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ^ "Crawley Town Football Club - past and present". Crawley Town Football Club website. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Welcome To Crawley RFC". Crawley Rugby Football Club website. 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "Tilgate Forest Golf Centre". Crawley Borough Council website. 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ a b "End of an era". Crawley Borough Council website. 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ a b c d Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Crawley New Town: Social and cultural activities". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3: Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) including Crawley New Town. Victoria County History. Retrieved 2007-08-02. Cite error: The named reference "leisure" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "K2 Crawley". Crawley Borough Council website. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Lord Coe opens K2 sports complex". BBC News website. 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ "K2 Crawley makes Olympic training camp guide". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "History Of The Hawth". The Hawth, Crawley website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Leisure and Culture: Young People". Crawley Borough Council website. 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ "Parks and Gardens: Goffs Park". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "Tilgate Park and Nature Centre". Crawley Borough Council website. Crawley Borough Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "Crawley Museum Centre". 24 Hour Museum website. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ^ "Stage two consultation on age of transfer for Crawley schools". Press Releases. West Sussex County Council. 2002-01-13. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Educational Establishments by Major Town: Crawley". West Sussex Grid for Learning. West Sussex County Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Adult Educational Centres". West Sussex Grid for Learning. West Sussex County Council. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ Hudson, T.P. (Ed) (1987). "Crawley New Town:Further Education". A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3: Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) including Crawley New Town. British History Online. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Central Sussex College - A New Era". Central Sussex College website. Central Sussex College. 2005. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Innovative new campus set for Crawley, not Horsham". Bulletin. University of Sussex. 2004-06-16. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ West Sussex Record Office (2003). "Newspapers in West Sussex" (PDF). Local History Mini-guide to Sources No. 8. West Sussex County Council. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ "Crawley News". MediaUK website. MediaUK. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ "Transmitters". UK Free TV website. UK Free TV. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ GCap Media plc (2008). "Information about Mercury FM". Mercury FM website. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "Aircheck UK - Sussex". Aircheck website. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ "Gold (Reigate and Crawley)". MediaUK website. MediaUK. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ "BBC Southern Counties Radio". MediaUK website. MediaUK. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ "Crime Library: John George Haigh". Turner Entertainment Digital Network, Inc. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "The official Faye White website!". 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "CNN/Sports Illustrated: Kevin Muscat". CNN/Sports Illustrated (an AOL Time Warner company). 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "Southgate plans a party". The Argus. Newsquest Media Group. 1999-11-12. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "Boxing: Ross Minter carries on a boxing tradition". The Argus. Newsquest Media Group. 2001-03-21. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 21 Jul 2005 (pt 27)". United Kingdom Parliament website: Hansard (House of Commons Daily Debates). The Information Policy Division, Office of Public Sector Information. 2005-07-21. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ "BBC h2g2: The Cure". BBC. 2005-08-12. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ "Feeling Their Way to Number One". Crawley News. Reigate, Surrey: East Surrey and Sussex News and Media. 2008-02-20. p. 10. ISSN 0961-4800 Parameter error in {{issn}}: Invalid ISSN.. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Citation: The Hon Sir Charles Walter Michael Court" (PDF). Murdoch University website. 1995-03-22. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "Gorillaz: Biography". Gorillaz Partnership. 2005. Retrieved 2007-09-18.