Assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy

In the assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy , 35th President of the United States of America , Kennedy (1917–1963) was fatally wounded by two rifle shots on November 22, 1963 in Dallas . When a suspect was Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested (1939-1963) and two days later in police custody from the nightclub owner Jack Ruby killed (1911-1967).

The Warren Commission set up by Kennedy's successor Lyndon B. Johnson came to the conclusion that Oswald was the sole culprit. A later called House of Representatives Committee of Inquiry (HSCA) found, however, that there were probably several perpetrators. There is no clear forensic evidence for this; rather, recent studies of the available material have corroborated the lone perpetrator thesis. However, the question remains controversial to this day. The attack polarized the public for a long time. The majority of Americans believe that Kennedy was the victim of a conspiracy . A number of conspiracy theories are still under consideration. The investigation of the murder case was hampered from the start by mishaps, omissions and mistakes by the investigative authorities, doctors and investigative commissions. Historians predominantly represent Oswald's individual perpetrators.

The events in Dallas

Kennedy's trip through Texas

Kennedy's trip to Texas , which would take him to San Antonio , Houston , Fort Worth, and Dallas , had been announced in September 1963. The President had three goals in this trip:

- To create the mood for his re-election in 1964,

- Raise funds for the upcoming presidential campaign and

- to settle the dispute within the Democratic Party of Texas, which raged between the Conservatives around Governor John Connally and the Liberals around Senator Ralph Yarborough . In the presidential election three years earlier - in addition to Kennedy's clear commitment to equal rights for African Americans - this controversy had contributed to the fact that he only achieved an extremely narrow majority in Texas, even though Lyndon B. Johnson , who was nominated as Vice President , came from Texas.

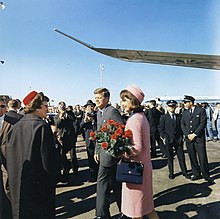

The president was accompanied by his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier-Kennedy , who had never been on a campaign trip before. Also because of their presence, the mood of the population was very warm when the presidential couple drove through San Antonio and Houston in an open car. The public in Dallas, a city known as the "hotbed of right-wing conservatism," was skeptical of the president's visit. On the day of his visit, an association called the “Investigative Committee of Free and American-Thinking Citizens” placed an advertisement in which Kennedy was accused, among other things, of having “scrapped the Monroe Doctrine in favor of the 'spirit of Moscow'”. This alluded to the president's Cuban policy, which had become much more cautious after the debacle in the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis , in which the Third World War could only just be avoided. A leaflet also circulated in the form of a wanted poster in which Kennedy was wanted for high treason .

There was also concern that Adlai Stevenson , the US Ambassador to the United Nations , was spat at and beaten with protest signs by angry demonstrators in the Dallas Memorial Auditorium on October 24. The day before, right-wing general Edwin Walker , a member of the John Birch Society , had accused Kennedy and Stevenson at the same place of planning to hand over sovereignty of the United States to the UN, which was in fact a communist conspiracy. On November 18, 1963, a planned Kennedys motorcade through Miami had to be canceled because the police had learned about assassination plans.

Nevertheless, the security was inadequate: While 350 police officers from the city of Dallas were for the protection of the president been turned off - a third of its total strength -, also forty members of the state police and fifteen Deputy Sheriff of Dallas County . In addition, 28 Secret Service agents had come to Dallas to protect the President, but only twelve of them accompanied the motorcade in which Kennedy wanted to drive past 200,000 onlookers from Dallas Love Field Airport to the Dallas Trade Mart. There he wanted to give a speech in which he wanted to acknowledge the continuation of the US military engagement in Southeast Asia . Unlike in Tampa , which Kennedy had visited a few days earlier, the roofs along the route were not secured. Kennedy drove in a 1961 Lincoln Continental X-100 with the top down - official sedans with a bulletproof roof did not yet exist. There were also no Secret Service agents on the bumper, which might have saved the president. Political scientist Larry J. Sabato attributes the overwhelming sense of security that prevailed in Kennedy and those around him, on the one hand, to his willingness to take risks, and, on the other, to the fact that no assassination attempt has been successful since the Secret Service had transferred the president's personal protection in 1901 was. Kennedy himself saw the threat of an attack, but remained calm. His assistant Kenneth O'Donnell later recalled his fatalistic words:

"If someone really wanted to shoot the President of the United States, it wouldn't be a difficult job: one day you would only have to go up to a tall building with a rifle with a telescopic sight, no one could do anything about such an attack."

The assassination attempt on the president

With Kennedy in the car sat his wife Jackie , Governor John Connally , his wife Nellie Connally , driver William Greer and a bodyguard, both from the Secret Service. When the motorcade was only four kilometers from the venue, it was heading for the Texas state textbook depot on Houston Street, which borders Dealey Plaza to the west . Here the cars turned in a 120 ° curve in a westerly direction onto Elm Street. Abraham Zapruder , an amateur filmmaker, was about halfway between the schoolbook depot and a grass hill behind a wooden fence and filmed the President's car driving by on normal 8 mm color film .

Shortly before, Governor Connally's wife had turned to the President sitting behind her, in view of the many friendly waving people on the roadside, with the words: “Mr. President, you can't say Dallas doesn't love you, "and Kennedy had agreed," No, you certainly can't say that. "Those were his last words. Shortly afterwards, at 12:30 p.m., three rifle shots were fired. According to the Warren Commission's later so-called single bullet theory , the first failed, the second bullet penetrated Kennedy's neck, Connally's chest and wrist and injured his thigh. He sank into the lap of his wife sitting next to him, who hugged him and prevented his lungs from collapsing . Since Kennedy was wearing a corset for health reasons , he stayed upright so that the third shot hit him in the head, the right half of which burst open. Jackie Kennedy climbed onto the back of the limo and picked up some of her husband's brain matter that had splashed there. The Secret Service man Clint Hill , who had jumped on the car, pushed her back into her seat. The driver, who had slowed down after the second shot to look for the president, now accelerated the car to escape. Several eyewitnesses saw the gun barrel sticking out of a window on the fifth floor of the school book warehouse.

Kennedy was rushed to the emergency room at Parkland Memorial Hospital at 12:35 p.m., where fourteen doctors were on hand to help him. His skin color was ashen to bluish-white, his eyes no longer responded to light stimuli, but his heart was still beating. After he was undressed and intubated , doctors noticed a small gunshot wound below the Adam's apple that caused him to lose oxygen. Therefore, a tracheostomy was performed. A cardiac massage was ineffective and led only to the fact that large amounts of blood and brain matter from the gaping wound in his head were lost. A closer examination of the wound was no longer carried out. Kennedy was probably brain dead by the time he was admitted . At around 1 p.m., doctor Kemp Clark signed the death certificate . Shortly afterwards, a Catholic priest arrived and offered him the sacraments .

In an impromptu press conference in the hospital, press officer Malcolm Kilduff announced the death of the president. Doctors Malcom Perry and Clark described the President's injuries, describing the front neck wound as an entry wound and the gaping head injury as an exit wound. They would not have found a bullet point on the head.

Under Texas law, the body should have stayed in Dallas to be examined by the judge of the peace . Secret Service agents managed to get him aboard Air Force One and flown to Bethesda Naval Hospital near Washington for an autopsy . Prior to takeoff, Lyndon B. Johnson took the oath of office as the 36th President of the United States on board the aircraft.

At Bethesda Naval Hospital, three doctors autopsied Kennedy's body from 8 p.m. to 4 a.m. The president's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy , and Jackie Kennedy were at the hospital urging a swift conclusion. For this reason, several standard procedures such as a head shave to expose the fatal wound or a comparison of the bullet holes in the body and clothing were omitted, because these had remained in Dallas. There was also no comparison of the results with those of the Parkland Hospital: Since they did not know that the tracheotomy had covered the second wound in the throat, the doctors at Bethesda X-rayed the body, suspecting a bullet . Unlike the doctors in Dallas, they concluded that the two shots hit Kennedy from behind, and they also found the bullet holes on Kennedy's neck and head.

On November 25, 1963, John F. Kennedy was buried in a state funeral in Arlington National Cemetery.

The arrest of Oswald

Immediately after the shooting, the numerous security forces who were present rushed to the textbook warehouse. Some also ran in the opposite direction to the grass mound, believing the gunshots came from there. They climbed over the fence and looked for possible shooters in the parking lot and the railway area beyond. Three tramps were found in a freight wagon who were arrested but released three days later. Since there was no other way to hide in the area, the search was soon stopped. In the canteen of the school book warehouse, Lee Harvey Oswald , a 24-year-old casual worker who had been working in the school book warehouse since October 15, 1963, was checked by a police officer. His supervisor, Roy Truly, testified that he was a member of the workforce, so he was able to leave the building before it was cordoned off by security forces. He walked several blocks, then rode an omnibus that was not moving due to the traffic jam caused by the events, and switched to a taxi that dropped him off near his home in Oak Cliff, a residential area of Dallas. Oswald arrived at his apartment around 1 p.m.

A few minutes after the murder, the police gave a personal description of the alleged assassin, who had been seen by several witnesses at the window of the school book warehouse. At around 1:15 p.m., the police officer saw JD Tippit Oswald, who had left his apartment and was now walking, and stopped him. After a brief exchange of words Oswald killed the policeman with four shots from a revolver the company Smith & Wesson , caliber 38, and fled. The police stopped him in a movie theater and arrested him. Because he resisted, there was a scuffle in which a policeman was injured in the hand and Oswald in the face. An angry mob of over a hundred people had gathered in front of the cinema to lynch Oswald , mistakenly assuming that the police had arrested him for the Kennedy assassination and not for the murder of Tippit.

In the meantime, the police had searched the school book depot. On the fifth floor, behind stacks of book boxes, she found a repeating rifle with a telescopic sight , which the security forces initially described as a Mauser . It was later discovered that it was an Italian make of the Mannlicher-Carcano model from the Second World War. Next to it were three empty cartridge cases. A handprint of Oswald's on the weapon could be detected, and the traces on the projectile that had injured Connally's thigh matched the profile of the gun barrel . Oswald had ordered the rifle and revolver in the months before under the false name Alek Hidell from post office boxes in New Orleans and Dallas.

Oswald was questioned by the FBI and the Dallas police in their headquarters under generally chaotic circumstances: regular protocols were not drawn up, and the press had largely free access to the police building. Police chief Jesse Curry wanted to counter rumors that Oswald was being mistreated in police custody. Not only the officials, but also Oswald had the opportunity to speak to the press. Here, as during the interrogations, he denied any involvement in the Kennedy murder and declared that he should be made a “ scapegoat ” (English: patsy ).

The murder of Oswald

Because it was to be feared that if the press continued to report intensively, it would no longer be possible to find an unbiased jury who did not yet know anything about the case, it was decided to transfer Oswald to the Dallas District Jail. Although there had been death threats, the date was announced with the same generosity to the press as the initial interrogation. However, the transfer was delayed because the vehicle originally intended was too small to accommodate the guards. Another delay arose because Oswald had asked to take his sweater with him. At 11:21 a.m. on November 24, 1963, the guards took him into the garage in the basement of the police headquarters, almost exactly at the same time as Jack Ruby , a Dallas nightclub owner with ties to the Mafia , who had entered the building moments earlier. With the words: "You killed my president, you rat," Ruby fired at him in front of the television cameras. Oswald was taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital with a shot in the stomach, where he died shortly after of internal bleeding.

Ruby was sentenced to death for murder in March 1964 . He died of a pulmonary embolism in January 1967 . He made various statements about his motives. Shortly after his shooting at Oswald, he is said to have stated according to testimony that he shot in order to spare Jackie Kennedy, whom he admired, from giving testimony during the trial and because he wanted to refute the suspicion that a Jewish conspiracy was behind the murder of the President: The inflammatory report from the self-proclaimed "Investigation Committee" had, among other things, carried a Jewish name.

Public reactions

Expressions of grief

The death of the charismatic president struck the American public as a shock. When Walter Cronkite , the newscaster for television station CBS, announced the death of the president nationwide at 2:38 p.m. New York time , he fought back tears. Everywhere people were crying in public, strangers began to talk and touch on the street. Many Americans left their jobs to watch reports on the attack on the radio or television. Church bells rang across the country, and American football games , which took place everywhere like every weekend, were canceled. The Boston Symphony Orchestra changed the program in the middle of a concert and played the funeral march from Beethoven's 3rd Symphony . All theater performances on Broadway were canceled, and in the evenings the advertising lights in Times Square in New York went out. Political opponents of Kennedy and racists only made occasional expressions of joy. Almost everyone later remembered exactly where he was when he heard of the events in Dallas. More than half of the population suffered from physical symptoms of grief such as a lack of appetite or sleep , nervousness or nausea .

Politicians abroad expressed their deep concern. Winston Churchill spoke of an immeasurable loss for the USA and the world, the President of Venezuela , Rómulo Betancourt , had to cancel a press conference because of a crying fit. In Chile and Brazil a state mourning lasting several days was declared . Crowds of people flocked to the American embassies to sign the condolence book. The mourning was particularly great in West Berlin : on November 25, 250,000 people flocked to Schöneberg Town Hall , the square where Kennedy had given his big speech a few months earlier . The Governing Mayor Willy Brandt said:

“A flame has gone out for all people who hope for a just peace and a better life. The world became a lot poorer that evening. "

First doubts about Oswald's sole responsibility

A study carried out in November 1963 found that the people of the United States felt especially compassion for the widow and children, complained that a young, dynamic politician had been murdered at the height of his power, and felt great shame that " something like this could happen in our country ”. The evaluation of the political effects at home and on relations with foreign countries followed as relatively insignificant; people had confidence in the new government. It was particularly emphasized that the population by and large recovered quickly. This was mainly attributed to the fact that around 90% owned a television set and were able to take part in the events after the attack and in funeral ceremonies almost continuously for days, which meant that they could say goodbye to Kennedy in a process that lasted several days.

The polls also showed that initially only 29% of Americans believed in Oswald's sole responsibility. Much of the mainstream press advocated the lone perpetrator theory. Oswald's prejudice was criticized in letters to the editor and occasionally in editorials. The doubts were based on the sometimes erroneous and contradicting press reports of the hectic first days, the statements of the doctors at Parkland Hospital who spoke at a press conference of a bullet wound in the throat, and on the murder of Oswald by Ruby, which aroused suspicion, Oswald should have been silenced.

The doubts about the single perpetrator thesis came primarily from Europe: In France a series of articles appeared in the magazine L'Express , in Germany similar articles appeared in the Berliner Morgenpost and in the world . In June 1964 a Who Killed Kennedy Committee was formed in Great Britain , which included prominent left-wing intellectuals such as the philosopher Bertrand Russell , the publisher Victor Gollancz and the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper . The committee relied primarily on a catalog of critical questions that the American lawyer Mark Lane had published on December 19, 1963 in the small, radical left New York weekly National Guardian . Lane had offered Oswald's mother his services to represent her son posthumously. After the Warren Report was published, he summarized his criticism in 1966 in the book Rush to Judgment - a first bestseller on the Kennedy assassination attempt. In the same year Edward Jay Epstein published an expanded version of his master's thesis . It was titled Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth and also became a bestseller. Lane and Epstein were able to fall back on the research of committed and often female lay people. Like many of the first American doubters of the single perpetrator theory, including the two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling , you came from the left-wing liberal milieu. By the 1950s they themselves had become victims of conspiracy theories followed by the McCarthyist government , and now the Vietnam War shattered their belief in the liberal rule of law . Now they believed that Kennedy had been shot because, in his speech to American University on June 10, 1963 , he had spoken out in favor of an end to the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union.

Because the reputation of the Washington establishment, which was unanimously behind the Warren Report, threatened to suffer as a result of the growing doubts about Oswald's sole responsibility, a CIA memo of April 1, 1967 advised the critics of the Warren Report to pursue selfish goals and to bring them close to communist propaganda. The CIA developed a campaign that made the hitherto little-used expression English conspiracy theory popular for these doubts . This was intended to ridicule and de-legitimize the belief that there was a conspiracy behind the attack.

Birth of the Kennedy Myth

The Kennedy murder was seen as a historic turning point . After 1963, the negative side of American politics began to show itself more and more clearly, starting with the race riots to the murders of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy , the Vietnam War and ending with the Watergate affair . In counterfactual speculation , it has often been concluded that these unpleasant developments could have been avoided if Kennedy had not been assassinated. Even Oliver Stone was in his film JFK - Tatort Dallas assume that it would not come under Kennedy to the Vietnam War.

A Kennedy myth emerged that raised the president to a salvific figure. His widow, who in an interview described the life and reign of her husband as Camelot , also contributed to this, the mythical castle of King Arthur and his round table. As a result, the attack appeared to be regicide, a grave sacrilege . According to a 2003 Gallup poll, Kennedy was considered the greatest American president alongside Abraham Lincoln .

Explanations for the popular conspiracy theories

According to a thesis of the American journalist Tom Bethell , which has been adopted by several researchers, people tend in an irrational way to name a cause of a correspondingly large size for a traumatically experienced event. In Kennedy's case, it is said to have already seemed an unsatisfactory explanation to his widow that only a “silly little communist” could have murdered her husband: “He didn't even have the satisfaction of being murdered for civil rights .” Similarly the Berlin historian Knud Krakau attributes the emergence of a veritable "conspiracy theories industry" ( as early as 1966/67, the Esquire magazine listed sixty conspiracy and murder variants of the Kennedy assassination) to the fact that the officially offered declaration for the early death of the popular president in the The public was perceived as unsatisfactory: The Warren Commission's report submitted in September 1964 did not provide a plausible motive for the alleged individual perpetrator, Oswald. The widespread demand for a "'healing' explanation" has spawned conspiracy theories that "hit a well-functioning market mechanism".

Social psychological studies on the genesis of conspiracy discourses did not confirm Bethell's thesis. The philosopher Gerd H. Hövelmann believes that the unusually large number of conspiracy theories on the Kennedy murder is more due to the high degree of visibility of this crime and to the, in his opinion, overt forgery and manipulation of evidence that was used in the investigation of the murder and in defense of Oswald's sole perpetrator.

Investigations

FBI investigation

After the assassination attempt on Kennedy, the FBI got involved in the investigation of the Dallas police. On November 24, 1963, a few hours after Oswald was shot, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover declared : "What I care most about is to get something out that can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin" .

On December 9, 1963, just 17 days after the assassination, the FBI report was released. President Johnson had urged it to be published quickly. It found that three projectiles had been fired: the first hit Kennedy in the back, the second Connally, and the third was the fatal head shot.

One of the reasons why the FBI tried to end the investigation as quickly as possible was concerns about its own reputation: In the weeks before the assassination, one of its agents had collected information about Oswald, an avowed Marxist-Leninist who was in the Soviet Union had lived. A few weeks before the attack, the agent had spoken to Oswald's Belarusian wife twice but never met him. Oswald himself had asked him in writing not to bother his wife any further. This complaint and other documents about him were destroyed after Oswald's murder, out of concern that it might become known that the FBI had been closely on the killer but had not prevented the assassination attempt.

Warren Commission

The Warren Commission (official name: Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy ) was convened by Kennedy's successor in office, Johnson, on November 29, 1963, to investigate the circumstances of the attack. It is named after its chairman, Earl Warren , who was then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court .

In addition to Warren, the commission consisted of six members:

- Allen Welsh Dulles , former director of the CIA , fired by Kennedy for unsuccessful Bay of Pigs invasion

- Senator John Sherman Cooper ( Republican )

- Senator Richard B. Russell ( Democrat )

- Congressman Gerald Ford (Republican, later US President)

- Congressman Hale Boggs (Democrat)

- John Jay McCloy , Former President of the World Bank and High Commissioner in the Federal Republic of Germany,

The Commission acted in a focused and rushed manner. Warren urged the commissioners to have the report ready before the next presidential election campaign began in the summer of 1964 . The commission met 51 times, more than 600 witnesses were questioned, and around 3,000 pieces of evidence were seized. Russell and McCloy attended only a few sessions. The real work was done by assistants like Arlen Specter . In particular, Ford, who changed the autopsy report for lack of time, and Dulles, who made sure that the assassinations of CIA agents on Castro were not an issue. Keeping this secret and nipping speculation about a communist conspiracy in the bud was the declared aim of the commission, which was therefore made up exclusively of trustworthy members of the Washington establishment.

After only ten months of work based on the results of the investigation by the Dallas police and the FBI, the result was first communicated to the media in September 1964, followed by the publication of the 888-page final report, the Warren Report (Warren Report). Some time later, a total of 26 volumes of hearing minutes and evidence appeared.

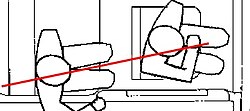

The commission came to the conclusion, published in the Warren Report, that Oswald was the sole perpetrator and that there had been no conspiracy. Oswald fired three shots from the fifth floor of the school book depot at the presidential limousine and killed John F. Kennedy. It didn't take a marksman to fire three shots through a group of trees at a moving target within 4.8 to a maximum of seven seconds. The first shot went wrong, the second caused Kennedy's neck wound and all injuries to Connally, who was sitting in front of him, and the third was the fatal head shot. In addition, Oswald is responsible for the death of the patrol officer Tippit. The commission assumed that Oswald's psychological disruption was the motive. She did not want to see a conspiracy behind his murder either, Ruby had acted spontaneously and alone. In addition, the Warren report criticized the obvious weaknesses in the personal protection of the president, which subsequently led to his significant improvement.

The Warren Report left many contemporaries unsatisfied. Especially the history of the "critically so-called magic bullet " (Engl .: magic bullet ) to have led to seven injuries to Kennedy and Connally, pushed many places in disbelief. It also soon became known that the commission had not followed up any evidence suggesting more than one perpetrator. At no point had commission members questioned the results of the FBI's work, neither photographs nor x-rays taken during the autopsy were available to them. Indeed, President Johnson had instructed commissioners not to investigate any evidence of involvement by Cuba or other states, as deliberately scattered by Cubans in exile in the days after the attack: the president feared the news that Cuba or the Soviet Union were behind the attack , could conjure up the danger of a third world war . Senator Russell heard the warning from him on November 29, 1963:

"We have to keep this out of the arena where they testify under oath that Khrushchev and Castro did this or that and are driving us into a war that can kill forty million Americans in an hour."

Johnson publicly praised the report after it was published, but in background discussions he doubted its conclusions and suspected a connection between the Kennedy assassination and the CIA's secret projects to assassinate foreign statesmen.

The prevailing view today is that the Commission did not conduct an impartial and open-ended investigation into the case. The commission did not consider the possibility that there were other perpetrators or that Oswald was innocent.

Prosecutor Jim Garrison's investigation

Based on these inconsistencies, the prosecutor struggled Jim Garrison in New Orleans in March 1967, a judicial inquiry on with which he wanted to demonstrate that the Kennedy assassination result was a conspiracy by the CIA in which Oswald, the pilot David Ferrie said in Oswald had completed pre-military training in his youth, and Clay Shaw , an obscure businessman he suspected worked for the CIA, was involved. Garrison had Shaw arrested and brought numerous evidence against the sole perpetrator of Oswald. A number of the evidence gathered by Garrison suggested that Oswald was indirectly acting on behalf of the CIA, in an unofficial group to which his killer Ruby belonged.

For example, he publicly screened the Zapruder film for the first time , which had been submitted to the Warren Commission, but was only known to the public in a few frames published by LIFE magazine . In the film you can see that Kennedy's head seems to fly back when the shot is fatal, although the alleged shooter is said to have been sitting behind him in the school book depot and not in front of him on the grassy hill. Garrison also put the course of the bullet, which according to the Warren Report should have left a total of seven wounds on Kennedy and Connally, as completely implausible. Several of his witnesses testified to have seen Oswald with Shaw or Ferrie or even heard them discuss the planned murder at a party.

However, Garrison's reasoning collapsed when Ferrie died of a ruptured brain aneurysm on February 22, 1967 and it was revealed that the second lead witness had made his testimony under the influence of hypnosis and the sleeping pill thiopental . Within just an hour of January 29, 1969, the jury came to the unanimous conclusion that Shaw was innocent in what American publicist Gerald Posner called Garrison's "fiasco".

Garrison published two non-fiction books on the results of his investigation, A Heritage of Stone in 1970 and On the Trail of the Assassins in 1988 (1992 edition: Who shot John F. Kennedy? - On the trail of the Dallas murderers ).

Ramsey Clark's Committee

In 1968, a committee chaired by then Attorney General Ramsey Clark dealt with the medical findings of the dead president. The committee came to the conclusion that the storage and origin of the evidence presented to it were not always fully documented, but nevertheless confirmed on their basis the results of the Warren Commission, according to which Kennedy was killed by two bullets, the one behind and above him must have been fired from the position in which it was located.

Church committee

The Church Committee of the US Senate investigated the illegal gathering of information by the CIA and FBI after the Watergate scandal in 1975 and also consulted their behavior in the Kennedy assassination. It concluded that the FBI, the primary investigative body of the Kennedy assassination, was being urged by Director Hoover and unnamed "senior government officials" to rush through the investigation. The Church report indicated that senior members of both agencies may deliberately fail to disclose potentially important information.

House Select Committee on Assassinations

Because conspiracy theories about the murders of the Kennedy Brothers and Martin Luther King continued to circulate, a House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was entrusted with further investigation in 1976 . After three years of work, it presented a report in 1979 that essentially confirmed the findings of the Warren Commission, but criticized the FBI's investigations as " seriously flawed" . Although the FBI had adequately determined Oswald's past life and perpetration, it did not properly pursue the possibility of a conspiracy. The report named the failure of the secret services to cooperate as the cause of these errors, as well as “time pressure and the desire of the national leaders to allay public fears that there had been a conspiracy”.

The committee confirmed the single bullet theory that Oswald shot Kennedy three times and killed him with the third shot. It made it highly probable, however, that there was another, unidentified shooter who fired a fourth shot from the grassy hill at Dealey Plaza, but missed it. Behind the Kennedy assassination there was a “conspiracy” (the English word conspiracy in this context is synonymous with the criminal association of German criminal law). The committee members could not say who was involved. Based on the evidence available to them, they concluded that neither the Soviet nor the Cuban governments nor the FBI were involved in the murder. An involvement of the American mafia or of Cubans in exile hostile to Castro cannot be ruled out.

The basis for assuming a second shooter were recordings of radio contact between a motorcycle policeman in Kennedy's escort and a police station, which were made with DictaBelt plastic tape . No immediate shots can be heard on the recording for the human ear. The HSCA entrusted a specialist company to examine the tape. Comparing the impulse patterns of the recording with those made with a rifle of the same type at Dealey Plaza, the result was that there was a 50 percent probability that a fourth shot could be heard from the direction of the grassy hill. A more detailed investigation by the computer scientists Weiss and Aschkenasy came to the conclusion that the probability is up to 95%.

National Academy of Sciences

In 1982, the National Academy of Sciences presented the results of a ballistic-acoustic test it had carried out on behalf of the US Department of Justice . A committee of scientists chaired by the physicist Norman Ramsey had checked the results of the HSCA, according to which a DictaBelt recording of the Dallas police showed a fourth shot that had been fired from the grass mound. The scientists came to the conclusion that this shot did not occur. The corresponding popping noises were only recorded about a minute after the fatal shooting at Kennedy. On March 28, 1988, the Justice Department told the United States Senate Judiciary Committee that the HSCA's conclusion that there had been a conspiracy was erroneous. The question of whether four shots can be heard on the DictaBelt recording is still controversial.

American Bar Association mock trial

In August 1992, the American Bar Association , an association of American lawyers, judges and law students, carried out a " mock trial " (quasi-trial) against Oswald. A real criminal case had not been able to take place because of the murder of Oswald. The process lasted two days and there was no clear result. The jury found Oswald guilty of the murder of President Kennedy by a majority of seven to five votes; however, since the American Courts Constitution requires jury unanimity for criminal trials , that result would have resulted in an acquittal in a real trial. All seven judges who took part in or observed the mock trial said they had found Oswald guilty.

Examination Board for Assassination Documents

In the fall of 1964, President Johnson ordered that the Warren Commission's files be on hold for 75 years (i.e. until 2039). In 1992, on the other hand, Congress passed a law , probably in connection with the numerous conspiracy theories that emerged after Oliver Stone's filming of the Garrison Trial and that were in conflict with the secrecy of these files, (English: President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992 ), according to which all files relating to the Kennedy assassination attempt must be made available to the public by 2017 at the latest, unless the President of the United States agrees to an extension of the secrecy. By 1998, a "Committee for the Sifting of Murder Documents" (English: Assassination Records Review Board ; short: ARRB) collected and published around 400,000 sheets of documents. A large part of the files, especially those of the HSCA, the police authorities, the secret services and the military, are still considered secret and remain closed to the public. The ARRB, whose task was merely to make the files accessible, nevertheless carried out several investigations and criticized in a report similar to the Clark Committee, above all, the sloppy handling of documents and pieces of evidence from the autopsy of the president, which was described as a real "tragedy" has been. Today the files are in a National Archives and Records Administration building in College Park, Maryland.

US President Donald Trump announced in October 2017 that he would publish the files that had not yet been released after the confidentiality period had expired on October 26, 2017, but after concerns from security authorities only released parts of the documents that had remained secret and gradually dropped more Share files. At the end of April 2018, he decided that some documents would remain unpublished for security reasons.

Doubts about the single perpetrator thesis

Witnesses

Several hundred people witnessed the attack at Dealey Plaza. Many of them made statements that do not fit the Warren Commission's account. Fifty witnesses testified that they heard shots fired from the front, from the grassy mound in Dealey Plaza. Several eyewitnesses said they were on the grass hill or at the underpass gunsmoke rising or see men with guns running away.

Witnesses in the school book warehouse also gave statements that do not match the results of the Warren report: Oswald is said to have been in the break room on the first floor a quarter of an hour before the shooting - according to the Warren Report, he had been in the fifth since 11:55 a.m. Floor; Just a minute and a half after the shooting, a policeman checked Oswald, who was drinking a Coke, on the ground floor of the school book depot with his gun drawn. Oswald is said to have by no means made a breathless impression, although in the version of the Warren Report he must have run down five floors immediately after the murder. Critics of the lone perpetrator thesis also question the statements of witnesses who saw Oswald before or after the murder of Tippit, especially since there are no eyewitnesses for the minutes immediately before their encounter.

In the years and decades that followed, reports were published by various witnesses claiming to have seen one or more suspicious gunmen on the grassy hill or near the fence behind it. These people are said to have worn a suit, uniform, bomber jacket or the clothes of railway workers, depending on the version. Some of these reports describe events that do not match the film and photo documents of the events and can therefore be considered falsified. According to Larry Sabato, others appear credible, but since the Warren Commission had refrained from listing and questioning all of the eyewitnesses who were present at Dealey Plaza, it is no longer possible to determine with certainty whether and to what extent these reports are based on real observations are based.

The proponents of the single perpetrator thesis also refer to a large number of witnesses who confirmed it, such as Howard Brennan, who saw Oswald with the rifle at the window on the fifth floor and from whom the first description of the perpetrator comes. The overwhelming majority of all ear witnesses (76.7%) only heard three shots, and only 8.7% could remember four or more shots. Other lists of testimony come to a majority in favor of the grass hill as the starting point for the shots. The different statements of the ear witnesses regarding the direction from which the shots came can be explained if one takes into account echo effects . In addition, eyewitness accounts are often unreliable and there are often shifts in the memory image when witnesses take things they read or heard from others to be their own memories. In particular, the Zapruder film and Oliver Stone's film JFK - Tatort Dallas might have obscured or falsified the memories of witnesses. In addition, there were reports from people who only wanted to make themselves important or for other reasons claimed to have been there. Jim Leavelle, a former Dallas Police Department officer, estimated in 2011 that if you gathered everyone who claimed to have been on the grass hill on November 22, 1963, " Rose Bowl Stadium would not be enough."

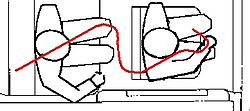

Zapruder movie

The Zapruder film provides important counter-arguments against the version of the Warren report - according to James D. Perry, "the strongest objective evidence of a conspiracy". The film shows Kennedy's head and whole body being thrown backwards. If the fatal shot had come from the textbook store his limousine had just passed, a sudden forward movement would have been expected. Proponents of the single perpetrator thesis point out that Kennedy actually moved a little forward when viewing the Zapruder film in single frames. The backward movement of his head could be explained by the explosive effect of the hit or by a neurological reaction to the injury, which triggered a spasmodic stiffening of the back and shoulder muscles. The force of the gunshot alone could have moved the head a few inches, but not the entire body of the president.

The reactions from Governor Connally seen in the Zapruder film have also led to criticism of the Warren Commission's findings. Critics object that Connally is seen reacting to his gunshot wound 1.6 seconds later than Kennedy. He said something similar later. This delay, according to critics of the Warren Report, is inconsistent with its assumption that both men were injured by the same bullet. Therefore, there must have been another shooter. (See also below under counter arguments ).

Although the Zapruder film is considered by many to be evidence of a conspiracy, other conspiracy theorists believe it is a fake : On the night of November 24, 1963, it was in a CIA laboratory and there was massive manipulation, which is considered to be unnatural recognize rapid movements, impossible shadows, people appearing or disappearing in individual images, etc. The photo engineer Roland Zavada, who analyzed the film on behalf of the ARRB at the end of the 1990s, said, however, that he had not discovered any indications of manipulation.

Oswald

Critics of the lone perpetrator thesis have further doubts about Oswald's personality: On the one hand, he was by no means “psychologically shattered”, as the Warren report claimed. On the other hand, he had absolutely no motive to murder Kennedy. As an avowed leftist, Oswald should have been more interested in the president continuing the policy of detente and de-escalation towards the Soviet Union, towards Cuba and Vietnam, which he initiated after the missile crisis and the Bay of Pigs adventure. A month before the attack, Oswald had announced that the Kennedy administration was doing "a pretty good job of civil rights." Supporters of the lone perpetrator theory, on the other hand, refer to Oswald's problematic personality, his tendency to violence and his left-wing radical political convictions, which were manifested after his arrest in the fact that he told the police that he had done nothing to be ashamed of - and not that he didn't shoot anyone. He greeted the press with a raised fist.

A few weeks before the attack, Oswald is said to have tried to get his driver's license and to buy an expensive car that he could not afford with his labor wages. He expects a larger sum in the near future, he said. This can be interpreted as an indication of a reward that his clients or co-conspirators would have promised him for his deed.

Some critics of the lone perpetrator thesis doubt the assertion of the Warren Report that Oswald had no relations with the American secret services: With a communist, whom Oswald had known himself to be since he was 16, who served on the security-relevant base of the U-2 spy aircraft and then defected to the enemy in the Soviet Union, who after his return ostentatiously campaigned for Castro's Cuba and even tried to get a visa there, that is not credible. In addition, Oswald also had relationships with Castro opponents and anti-communists such as George de Mohrenschildt, a Russian emigrant who had contacts with the CIA and who in the months before the attack became a close friend and probably also a financier of Oswald.

Others dispute Oswald's left-wing political views. The historian David E. Kaiser believes that Oswald's clumsy actions for the left-wing Fair Play for Cuba Committee (German: "Committee for a fair deal with Cuba"), of which he was general secretary and only member in New Orleans, could only have served this purpose to upset its reputation, just as the FBI's COINTELPRO intended. The address Oswald gave on his leaflets was also in a house where Guy Banister, a former FBI man with ties to both anti-communist Cubans in exile and the Mafia, had his office. Prosecutor Garrison and other critics of the single perpetrator thesis took this as evidence that Banister had something to do with the attack; Oswald is said to have been seen with him too. This is countered by the fact that Banister's office was in the same building, but could only be reached from a different street. Rather, Oswald had given a fictitious address that was close to where he worked at the time.

The CIA kept extensive files on Oswald, but when the CIA station in Mexico City requested information about him, they received a narrow file that only covered the period up to 1961. The then responsible CIA employee Jane Roman evaluated this in an interview in 1995 as evidence that the CIA had a "strong interest in Oswald", which should only be known to the initiated. The Cuban and Soviet embassies in Mexico City were under surveillance by the CIA, but the personal description they sent to the FBI and other federal agencies on October 10 did not describe Oswald, but a significantly older, sturdier man with receding hair. In the recording of a tapped phone call between Oswald and the Soviet embassy, the caller speaks in poor, barely understandable Russian. Oswald himself had lived in the Soviet Union for two years and spoke Russian with his wife - he had no language problems. Files from the CIA headquarters in Mexico were in 1971 by James Jesus Angleton , head of the counterintelligence department aside managed the CIA, personally. This has led to suspicions that it was not Oswald himself who applied for a visa for Cuba in Mexico, but only someone who claimed to be him, and that the CIA had something to hide.

In addition, at the end of September or beginning of October 1963, Oswald is said to have visited a Cuban woman in exile by the name of Sylvia Odio together with two determined anti-communists of the anti-Castro movement in order to acquire donations; In a phone conversation a few days later, one of the two companions made disparaging remarks to her about Oswald, who was “loco”, that is, mad and who had expressed the erroneous opinion, “You Cubans could kill Kennedy for what he did to you in the Bay of Pigs ". It is countered that Odio was no longer sure when a photo of Oswald was presented to her; At the end of September he was also on the way to Mexico City, where he tried in vain to obtain a visa for Cuba. At the beginning of October, the witness had already moved from Dallas. On September 25, according to a testimony, Oswald was not in Dallas but in Houston , where he tried to make a local call to get in touch with a member of the Socialist Labor Party . The American political scientist John McAdams therefore suspects that the visit to Odio was just one of more than a hundred Oswald sightings that became known everywhere after the assassination - even in places where Oswald could not have been. In addition, the episode contradicts the conspiracy narrative, according to which Oswald should have been presented as a leftist. An appearance with Castro opponents therefore makes no sense.

The "Backyard Photos"

Photos from March 31, 1963, in which Oswald poses in his back yard with communist newspapers and a rifle in hand, are described by critics of the lone perpetrator thesis as fakes because after his arrest Oswald denied their authenticity and the shadows on his face and his Body should come from different positions of the sun. In addition, Oswald actually had a different face shape. The sun is high and centered over the bridge of the nose because the nasal shadow is short and symmetrical to the bridge of the nose. Both sides of the neck would therefore have to be illuminated in the same way by the sun and the shadow of the body would have to be short and straight backwards, i.e. H. parallel to the bridge of the nose. But neither is the case.

The authenticity of the images has been confirmed by several photography specialists. The American computer science professor Hany Farid came to the conclusion in his investigation in 2009 that it was "highly unlikely that anyone could have done such a perfect forgery with the technology that was available in 1963". Oswald's widow later repeatedly stated that she took the pictures herself. An employee of The Militant newspaper , to which Oswald had sent the pictures to prove his revolutionary determination in April 1963, also confirmed that she had received them, but at the same time was amazed at the naivety with which the sender presented a Trotskyist and a Stalinist newspaper at the same time .

Autopsy results

Critics of the Warren Report point to inconsistencies between the reports by doctors at Parkland Hospital and the autopsy results from the Bethesda Naval Hospital. In Dallas, doctors thought the wound on Kennedy's throat was an entrance wound. During the autopsy, the larynx wound was described as being much larger, but this can be traced back to the tracheal incision made in the Parkland Hospital. Parkland Hospital doctor Robert McClelland insisted until his death that the large wound on the back of Kennedy's head was an exit wound. The Warren Commission only used the written reports from Parkland Hospital; X-rays and photographs were not used. As a result, suspicions were raised that the pictures had been stolen or altered. One author hypothesized that Kennedy's body was stolen en route from Dallas to Washington and was secretly manipulated to make entry wounds appear as exit wounds. The timing of this cannot be reconciled with the transport reports, especially since the coffin was never unobserved.

Commissioner Gerald Ford had the location of the gunshot wound on the back changed in the Warren Report: only an entry wound on Kennedy's neck would match a shot from behind and above. A lower wound on the back would also better match the bullet hole in Kennedy's clothes. Against this, advocates of the single perpetrator thesis argue that the president waved at the moment of the shot, causing his jacket to bulge.

The statements from the Bethesda and Parkland Hospitals also differ in whether the head wound affected the occiput or the parietal bone above the right ear, whether the brain or cerebellar mass was visibly protruding, and whether or not head hair was hanging on the wound; the doctors at Parkland Hospital hadn't noticed the second, smaller head wound. John McAdams points out the widespread inaccuracy in the distinction between "parietal bone" and "occipital bone"; many of the witnesses who claimed to have seen a bullet wound in the back of the head contradicted each other, and the statements of other witnesses were also clearly not reliable: for example, five witnesses who were present at Parkland Hospital testified that they had a gash on their left Side seen from Kennedy's head. Larry Sabato explains the discrepancies in the statements of both medical teams with errors and mistakes, which can be attributed to the time pressure under which they worked and to exhaustion: the autopsy at Bethesda Hospital lasted until the early hours of the morning. These errors, but above all that the body was illegally removed from Dallas, are a cause of the ongoing controversy.

In a review of the autopsy report from Bethesda Naval Hospital, the Clark Panel, to which all photographs and x-rays were available, fully endorsed the results of the Warren report in 1968. The allegedly forged X-rays and photographs of the autopsy at Bethesda Naval Hospital were checked by X-ray technician John Stringer in the National Archives in November 1966 and found to be exactly the same as the images he had taken three years earlier. They confirm that Kennedy was hit by gunfire coming from behind.

ballistics

Several ballistic arguments are made by critics of the lone perpetrator thesis . Above all, the story of the “ single bullet theory ”, which is said to have resulted in seven injuries to Kennedy and Connally, is met with skepticism. This ball was found almost undeformed on Connally's stretcher in Parkland Hospital. Critics speculate that it did not simply fall out of the governor's wound, but was deliberately placed there. During interrogation by the Warren Commission, the finder of the bullet was urged to state that he might have found the bullet on Connally's stretcher. On other occasions, he had given a different stretcher as the location.

A neutron activation analysis in 2004 revealed that all bullets and fragments found, including that of Connally's stretcher, came from two shots fired from the same Mannlicher-Carcano rifle. This was contradicted by a study by Texas A&M University from 2007, according to which it cannot be ruled out that the projectiles and remains of projectiles found were fired from different rifles of the same brand.

According to historian Michael L. Kurtz, Connally's back wound, which his attending surgeon from the Parkland Hospital described as a normal bullet wound, speaks against the theory of the single bullet ; if the bullet had previously hit another object, a larger wound would have been expected. It is also unlikely that a bullet that has penetrated several bodies would remain undeformed. According to experts on gunshot wounds, test shots on animal carcasses and on a human corpse with the alleged assassination rifle had resulted in significant deformation of the projectiles. Connally and his wife also remembered that two different bullets hit him and the President.

Jim Garrison had pointed out during the trial that this sphere must have changed direction several times in order to follow the course assumed by the Warren Commission. Proponents of the lone perpetrator thesis, on the other hand, state that the critics assumed that Kennedy and Connally were sitting in the wrong seating arrangement: The latter was sitting in the significantly lower emergency seat immediately in front of the President, so according to a three-dimensional computer analysis made as part of the ABA mock trial in 1992 that a single bullet could actually have inflicted all seven wounds and could only have been shot from a high position behind Kennedy.

The American computer animation expert Dale Myers designed a 3D simulation of the attack on the basis of all available films, photographs and blueprints over a period of ten years. The result was 2003's documentation The Kennedy Assassination: Beyond Conspiracy ( "The Kennedy assassination - beyond the conspiracy") on ABC shown that a Emmy won. If you follow this simulation, the shots that Kennedy and Connally hit came from a narrow corner that also includes some windows on the fifth floor of the school book warehouse, including the one from which Oswald is said to have shot.

It is also controversial whether it was technically possible for a rather average shooter like Oswald to fire three shots through a group of trees at a moving target within a maximum of seven seconds.

Critics of the Warren Report also refer to the witness James Tague, who was standing near the underpass at the time of the crime and was slightly injured by a fragment of a projectile. It is unlikely that this came from a bullet that was fired in the school book warehouse at the other end of the square, 150 meters away. The Warren Commission had also declared itself unable to reliably assign the ricochet to one of the three shots. Gerald Posner suspects that it came from Oswald's first, missed shot.

Ruby

Critics of the lone perpetrator thesis also interpret Oswald's murder as an indication of a conspiracy. The nightclub owner Jack Ruby, who had ties to the American mafia , did not act spontaneously in this version and to spare Jackie Kennedy, whom he admired, from the painful criminal trial, but to prevent the real backers and backgrounds of the assassination from coming to light. Whether Ruby acted spontaneously or had tried several times in the two days before to get to Oswald to shoot him is controversial: After Gerald Posner , on November 24th he could not have known that Oswald was about to be transferred; Nor did his behavior immediately before the murder - he had sent money to one of his strippers in a Western Union office and left his dog in the car - did not indicate a planned assassination attempt; According to David E. Kaiser , he could have had informants within the Dallas Police Department who would have given him the rendition date. In this context, it is also controversial how Ruby got to the police headquarters. He himself testified that he walked over the access ramp, whereas the statement of the police officers who guarded the ramp is against. He could therefore have entered the building via a side entrance. Then he would have lied, which is taken as an indication that he wanted to cover up the true background of his act.

A year after his conviction, Ruby hinted in a television interview that he himself was the victim of a conspiracy:

“The world will never know the real facts: in other words, my real motives. […] Unfortunately, these people, who have so much to gain and who had a strong motive for putting me in the position I am in, will never allow the real facts to come out into the world. "

Ruby asked the chairman of the Warren Commission to give evidence to President Johnson in Washington in order to convince him that he was not part of a conspiracy. If he were to testify in Dallas, he and his siblings would be in mortal danger. Warren refused. These fears are explained by Ruby's mental health, which has deteriorated significantly since his trial. According to his sister Eva before the Warren Commission, he was haunted by the paranoid notion that the US government was planning a Holocaust against all Jews who would serve as a scapegoat for the Kennedy murder. Ruby believed that 160 million Jews had already been murdered on the lower floor of the Dallas prison where he was being held. Shortly before his death he declared again that there was nothing to hide, that he had acted all alone.

Counter arguments

- The Mannlicher-Carcano rifle was the same weapon with which Oswald had already carried out an unsuccessful assassination attempt on the right-wing radical General Edwin Walker on April 10, 1963 . One of the two explains that it was initially identified by two police officers as a Mauser, which is variously cited as evidence against Oswald's sole perpetrator, by using the brand name Mauser as a generic name for a repeating rifle. In fact, both rifles look similar. Footage showing how the weapon was found shows that it was a Mannlicher Carcano.

- Political scientist John McAdams explains the numerous sightings of Oswald, which are cited as evidence of his involvement in a conspiracy, as implausible constructions of memories that only occurred after the attack. A large number of alleged eyewitnesses vividly recalled having seen Oswald in places where he could not have been. Fourteen residents of the small town of Alice testified that they saw or even spoke to him in the first week of October 1963 - but Oswald was demonstrably several hundred kilometers further north in Dallas and with his family in Irving on those days .

- Oswald had been seen carrying an elongated object wrapped in paper as he entered the warehouse on the morning of November 22nd. When asked about it, he had said that it was curtain rods that he needed to decorate his room. The paper was in the warehouse, but no curtain rod. In addition, Oswald's room was already furnished with curtains, that is, he was telling the untruth.

- Two fragments of spheres were found in Kennedy's car where they had damaged the inside of the windshield . This can only be explained if the shot was fired from behind.

- Computer-aided evaluations of the Zapruder film showed that Connally was hit much earlier than he himself stated. Movements of the right arm and hand, the lapel and the hat can be seen shortly after Kennedy was hit. The movement on the lapel matches the gunshot wound he suffered there.

- The assumption of conspiracy theorists such as Jim Garrison and Jim Marrs, members of several large organizations (the Mafia, the CIA, the FBI, the American military ...) were involved in the Kennedy murder is considered to be implausible: the more confidants the alleged Conspiracy, the higher the likelihood that information about it will eventually leak to the public.

- The list of over one hundred violent or unsolved deaths of witnesses or alleged accomplices in the assassination compiled by Jim Marrs contrasts with more than 10,000 people questioned and survived by the Warren Commission or other investigative boards into the Kennedy assassination. Secret Service man Roy Kellerman was also included in the list, who died of a heart attack in 1984 at the age of 69. According to John McAdams, this shows the lack of plausibility of this “list of deaths”, because to silence a witness after he has repeatedly made his detailed knowledge public for 19 years would be nonsense.

conspiracy theories

The critics of the single perpetrator thesis have put forward a large number of clues and arguments why Oswald could not be the perpetrator or at least not the sole perpetrator. However, they have not been able to agree on a coherent counter-thesis that would answer the open questions more conclusively than the Warren Report. Who was really behind the conspiracy against Kennedy, which they assumed, is also controversial among them. In a 2003 Gallup survey of 471 Americans over the age of 18, the Mafia (37% of respondents) were named as the alleged perpetrators, followed by the CIA (34%) and third Place Kennedy's successor Johnson (18%) and then Cuba and the Soviet Union (each 15%).

mafia

An obvious subject for conspiracy speculation was La Cosa Nostra , the American mafia. In this perspective, the attack could be a reaction to the considerable pressure of persecution under which Kennedy's brother Robert, as Minister of Justice, had put leading figures in organized crime, namely Sam Giancana , Santo Trafficante and Carlos Marcello . They all benefited from generous loans that Jimmy Hoffa , the head of the mafia-affiliated Teamster union, used to give them from his organization's pension fund. The impending conviction of Hoffa threatened to dry up this source of finance. As a result, Kennedy appeared to be ungrateful to the mafia, because on the one hand the gangsters had worked closely with the CIA on various attacks on Castro as part of Operation Mongoose . On the other hand, Giancana had donated for Kennedy's election campaign through his friend Frank Sinatra and shared his lover Judith Campbell with Kennedy. After the attack, the Mafia used Rubys as a henchman to remove the uncomfortable Oswald.

According to a statement by his lawyer Frank Ragano, Trafficante is said to have said to him in Italian on March 13, 1987 in Tampa :

“Carlos [meaning Carlos Marcello] screwed it up. We shouldn't have killed Giovanni [that is, John F. Kennedy] . We should have killed Bobby [meaning Robert Kennedy] . "

Since Trafficante was not in Tampa on that day, but in Miami , this statement is considered implausible.

CIA

Many conspiracy theories surrounding the Kennedy assassination mention the CIA. According to a report in the New York Times, Kennedy is said to have threatened after the Bay of Pigs fiasco that he wanted to "split the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it to the wind." This is seen as the main reason for opposition. Oswald appears in these speculations either as a willless tool that one has made submissive with the means of mind control, as they were tried out under MKULTRA in the 1960s , or as a mere straw man. The real shooters were the three vagrants who the police arrested shortly after the attack on the station premises, but soon let them go again. In two of them, some critics of the Warren Report recognized the CIA men and later Watergate intruders Frank Sturgis and E. Howard Hunt , but the Dallas police files now released show that they were really simple tramps. Historian John Newman believes that the CIA built Oswald as a straw man and scapegoat. As evidence, he cites, among other things, Oswald's visit to the Soviet embassy in Mexico City and his contact with a "Comrade Kostin" - allegedly a KGB agent who is said to be involved in assassinations and sabotage activities. After the attack, this contact had fueled the fear that the Soviet Union might be behind it; Johnson used him to force Warren to take over the chairmanship of the committee named after him and to end the investigation into a conspiracy.

Lyndon B. Johnson

Kennedy's successor, Lyndon B. Johnson , is said to be behind the assassination, as he has now become president and has been shown to slow down the Warren Commission's investigation. According to a later statement by his secretary Evelyn Lincoln , Kennedy no longer wanted to run with him in the 1964 presidential election, but with Terry Sanford . According to Barr McClellan's attorney , Johnson reportedly said to his alleged lover Madeleine Duncan Brown the day before the assassination : “The day after tomorrow these goddamn Kennedys will never bother me again. It's not a threat - it's a promise. ”After the television's History Channel released this version in 2003, former Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, as well as some former employees , protested . The broadcaster had McClellan's information checked and on April 2, 2004 publicly declared the allegation that Johnson was involved in the Kennedy murder to be unfounded and apologized to his widow for the broadcast.

Fidel Castro

According to some conspiracy theorists, Fidel Castro had Kennedy murdered in retaliation for the numerous murder attempts that the CIA and Mafia were jointly responsible for against him. In September 1963, Castro publicly warned that US leaders would not live safely if they believed they could have him killed.

In 2006, in his documentary Rendezvous with Death: Why John F. Kennedy Had to Die , the German journalist Wilfried Huismann put forward the thesis that Oswald had received US $ 6,500 in September 1963 for his offer to kill Kennedy at the Cuban embassy in Mexico City . The US government knew that - Johnson told an ABC journalist in 1968: "Kennedy tried to catch Castro, but Castro was the first to get him" - but did not pursue this lead for fear of war. In the German media, Huismann's thesis was received with skepticism, among other things because the alleged handover of the murder wages should have taken place in the embassy, which, however, as the Cubans were well aware, was bugged by the Americans . Only Oswald's wish to return to the Soviet Union via Cuba can be recognized from the eavesdropped telephone calls at the embassy; there was no mention of an assassination attempt on the president.

Soviet Union

The allegation that the Soviet Union was behind the attack was made by British lawyer Michael Eddowess in a book published in 1975. Then Khrushchev made sure that it was not Oswald himself, but a doppelganger who returned to the USA under his name, who then shot the president on behalf of the KGB . The motive is said to have been revenge for the humiliation suffered in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Jack Ruby was also a KGB agent. In 1981, to prove his thesis, Eddowess arranged for Oswald's body to be exhumed . However, a comparison with Oswald's dental medical records showed that the real Oswald was in the grave.

Cubans in exile

Various militant organizations of Cubans in exile are also suspected to be behind the attack. According to the historian David E. Kaiser, they were disappointed by the ambiguous course of the Kennedy government, which, even after the Cuban Missile Crisis and the official end of Operation Mongoose, continued to rely on regime change on the island and supported or tolerated sabotage and murder attacks, but on the other hand In order to save face internationally and to avoid reprisals by the Soviet Union on the Berlin question , officially denied any connection to right-wing exile groups. Therefore, these Mafia-related groups led Lee Harvey Oswald to shoot Kennedy. The murder carried out by an apparent communist was intended to induce the United States to wage war against Cuba and eliminate the Castro regime. The same thesis of murder as part of a conspiracy against his government was also advanced by Fidel Castro, for the first time in a public speech in Havana in November 1963.

Israel

Because Kennedy had put some pressure on Israel to end its nuclear program , " the Jews " were accused of being behind the attack. In counterfactual speculation is assumed here that Israel no nuclear bombs could build if Kennedy had lived on.

Edgar Hoover

The 68-year-old FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover (1895–1972) is said to have tried to blackmail the Kennedy brothers into keeping him in office after he turned seventy, but to no avail. He also despised the liberal views of the Kennedys and their lifestyle. Therefore, he had given instructions not to disrupt the mafia's murder plans, not to pass on information about Oswald's involvement in the murder plot and thus contributed to his success. After the assassination attempt, he suppressed all indications that the mafia was involved and supported the individual perpetrator thesis. In 1964, days before his testimony on the Warren Commission, he was named FBI director for life by Kennedy's successor, Johnson.

Military-industrial complex

The so-called military-industrial complex of the US, which was supposedly preparing for an escalation of the Vietnam War after France withdrew from Indochina in 1954, must have known that Kennedy was already considering a withdrawal plan by 1965. In addition, there has been strong anger in the American military and intelligence apparatus over the fact that Kennedy had not provided open military support for the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba , which the CIA had helped organize. On the contrary, in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the United States promised to refrain from further attempts to invade Cuba. Kennedy's predecessor Dwight D. Eisenhower had already warned of the increased influence of the military-industrial complex in the USA .

State of the discussion

The perpetrator and background of the Kennedy assassination are still controversial today. According to annual Gallup surveys since 1963, only between 10 and 36% of the US citizens surveyed (2013: 30%) believed in a lone perpetrator. 50 to 81% (2013: 61%) believed in several perpetrators, most of whom suspected the Mafia as the client. The percentages for the single perpetrator thesis have risen steadily since 2001, those for the multiple perpetrator thesis have steadily decreased.

The number of book publications on the Kennedy murder that question the lone perpetrator thesis is estimated today on the basis of a special bibliography at several thousand. With a few exceptions, none of them come from trained historians. The British literary scholar Peter Knight writes in his history of the depictions of the assassination:

“Academic historians and Kennedy biographers show a striking lack of focus on the specific details of the assassination… Since the 1960s, the representation of the Kennedy assassination has become a field of either conspiracy accounts by unprofessional historians with no mainstream establishment or by novelists, artists and filmmakers. However, mainstream journalists and biographies and histories have implicitly shed light on the assassination attempt as discussions of Kennedy's death turned into debates about the legacy of his administration and the decade he represented. "

The single perpetrator thesis is still the "dominant paradigm " of the Kennedy murder. Most historical or political science accounts of Kennedy's life and politics also follow the single perpetrator theory, insofar as they deal with Kennedy's death at all. According to the Berlin history professor Knud Krakau, the reason that historiography and serious journalism tend to assume that Oswald was the sole perpetrator is that “all alternatives are even less convincing”.

Artistic reception

The Kennedy assassination attempt and the conspiracy theories that followed have become an integral part of American culture. The topic has found artistic expression in various media, often in a form that deviates from the individual perpetrator thesis.

Fiction

In the 1975 novel Illuminatus! by Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea , a satire about conspiracy theories, like Kennedy is assassinated at Dealey Plaza from five different shooters at the same time is described.

In his novel Libra , published in 1988, the postmodern novelist Don DeLillo tells how CIA agents manipulate Oswald, the actual protagonist of the book, into preparing the assassination attempt that they actually want to fail. The author leaves open why it succeeds. For DeLillo, the Kennedy assassination is a media event, an example of the loss of a coherent reality that television viewers suffer through the media over-representation of violence and the overabundance of sometimes contradicting information. In the end, Oswald is shot twice, so to speak: with Jack Ruby's revolver and with the television cameras running .

The American writer Norman Mailer dealt with the assassination attempt on Kennedy in two books, both of which represented different theses on the perpetrator. After long harsh criticism of the Warren Report, he published the novel Harlot's Ghost in 1991 , in which he allowed the protagonist, the CIA agent named Harry Hubbard, to speculate on whether or not people from his own agency were organizing the murder of Kennedy or might have covered up the truth. In 1995 an extensive biography of Lee Harvey Oswald followed. The genre classification of this book is difficult: Mailer himself called it “a special kind of non-fiction book that can be classified as a crime novel ”, the literary scholar Peter Knight calls it a “ non-fiction novel”. The work is based, among other things, on material that Mailer had found in the KGB archives, which have now been opened, as well as on interviews with former Soviet agents who monitored Oswald during his stay in the Soviet Union. From these sources Mailer drew the conclusion that Oswald acted as a lone perpetrator.

The American author Stephen King published the novel 11/22/63 in 2011 . In it, the first-person narrator Jake Epping prevents Lee Harvey Oswald from carrying out his assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy by means of a journey through time . On his return to the present, however, it turns out that this has become much worse due to the changed course of world history : The Vietnam War, which Epping actually wanted to prevent, also took place under Kennedy, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 never existed, Kennedy's successor in the presidency was George Wallace , a supporter of racial segregation who led the USA into a nuclear war , etc. Epping succeeds in reversing this change in history.

Movie

Henri Verneuil and I as Icarus had a first discussion of the Kennedy assassination attempt in 1979. Although the shot president of an unnamed state bears the (French) name Marc Jary, the plot is closely based on the assassination attempt in Dallas; so z. B. the alleged assassin the name "Daslow" (an anagram for "Oswald"). Similar to Jim Garrison's version , the assassination ultimately turns out to be a secret service conspiracy that is uncovered by Attorney General Volney (played by Yves Montand ).

In 1991 the American director Oliver Stone sparked a heated controversy with his film JFK - Tatort Dallas . Stone had the rights to the 1989 book Crossfire. The Plot That Killed Kennedy by conspiracy theorist Jim Marrs and also did extensive research on the Kennedy assassination. His film tells the research of Jim Garrison (played by Kevin Costner ) and his unsuccessful prosecution of Clay Shaw from a sympathetic perspective and adds up to "a distillation of most of the various conspiracy theories that assassins had spread over the years". He often mixed authentic film material with scenes he had shot himself in quick cuts, so that the viewer could not distinguish which images are authentic and which are not. For this, Stone was criticized by the American quality press as demagogic : He twisted history, invented people and dragged the reputation of others who really existed into the mud, he irresponsibly mixed speculation and facts and unfairly influenced the image of history in younger people Spectator. Stone, however, held that his film was conceived as a “counter- myth ” that he wanted to contrast with the “myth” spread by the Warren Commission of Oswald's sole perpetrator. He sees his approach as more postmodern, similar to Akira Kurosawa's film Rashomon - Das Lustwäldchen from 1950, which shows three different versions of the same event; it is important for him to reopen the discussion about the attack. In fact, the Kennedy assassination was discussed intensively again in the period that followed. JFK - Tatort Dallas was also a huge hit at the box office .

The 1991 feature film Jack Ruby - Im Netz der Mafia speculates on the motivation and background of Ruby (played by Danny Aiello). Among other things, he shows Ruby as an emotionally unstable, publicity-hungry person and illuminates his long-term connections to both the mafia and the police in Dallas as well as his work as an FBI informant.