Fossil Butte Member

The Fossil Butte Member ( Engl. For "Fossil hilltops layer member" or "-Unterformation") provides a lithostratigraphic subunit of the Green River Formation is that the northwest of the United States , mainly in the border area of the states of Wyoming , Utah and Idaho is widespread. It forms a section within the sedimentary sequence of Fossil Lake, which existed in the middle section of the Lower Eocene around 52 million years ago for a period of around 2 million years. Fossil Lake represents the westernmost part of the Green River lake systemThis chain of lakes comprised a total of three lakes, the deposits of which have been handed down today as the Green River Formation. The Fossil Butte Member consists of fine-grained sediments that are deposited in very thin layers on top of each other and are partly rich in fossil fuels . However, the extraordinary fossil conservation can be seen as an outstanding feature, making the sediment sequence one of the most important fossil deposits of that geological era .

The majority of the fossils come from two stratigraphically separated sites. The finds mostly include complete skeletons of vertebrates , with fish dominating. The remains of Knightia and Diplomystus should be emphasized here , the number of which is in the hundreds of thousands. But reptiles , birds and mammals are also represented to a notable extent. Particularly among the mammals, some of the more original, now extinct kinship groups stand out, with odd-toed ungulates and bats , however, two lines of development that still exist today have been proven. In addition to the vertebrates, numerous remains of insects and plants have also survived, as well as parts of the soft tissue and food. In relation to the amount of finds, the Fossil Butte Member is one of the most productive fossil sites known worldwide from the Eocene period. Due to the high biodiversity of the organisms found, the landscape of that time can be reconstructed relatively precisely. At the time of Fossil Lake's existence, the climate was tropical . Dense forests grew near the shore. In and around the lake lived a rich flora and fauna that formed a tightly woven food web.

Research into the fossil butte member began as early as the second half of the 19th century with the discovery of individual mollusks , later also vertebrates, mostly fish. Around the same time, the first privately and commercially oriented fossil retrievals began, which increased sharply in the 1960s. They continue to this day and contributed significantly to the strong growth in the number of known finds from the diverse world of Fossil Lake. Because of this commercial salvage, numerous finds from the Fossil Butte Member are represented in museums around the world. The prominent position of the fossil-bearing find layers led to the establishment of the Fossil Butte National Monument in 1972 .

Geographical location

The Fossil Butte Member is a local section or a subunit of the Green River Formation , which is named after the Green River , a tributary of the Colorado River . This subunit is mainly formed in the southwest of the US state Wyoming as well as in the extreme southeast of Idaho and in the northwest of Utah . It is part of the sediment sequence of Fossil Lake, which existed here as one of three lakes that no longer exist in the Lower Eocene . The Fossil Lake covered a large part of today's Fossil Basin , a narrow, elongated and north-south running synclinal depression, which connects directly to the west of the Green River Basin . The town of Kemmerer is only a few kilometers east of the Fossil Basin, about halfway to the Green River Basin , while Bear Lake is to the west . The area today averages between 2170 and 2300 m above sea level, and in the area of the Bull Pen it also reaches up to 2464 m. It represents a hilly to rugged rocky landscape created by erosion , which is covered with bush vegetation consisting of sage and creosote bushes . Climatically, the area is today characterized by dry, partly semi-desert-like and winter-cold conditions.

geology

On the geology of the Green River Formation

The Green River Formation extends over an area of more than 65,000 km² over large parts of the US states Wyoming , Utah and Colorado and reaches an average thickness of 600 m, in the eastern area it has its maximum with 2150 m. It consists mainly of limnic-lacustrine deposits and is one of the largest accumulations of this type in the world. These deposits represent the remains of three lakes that made up the Green River lake system , but which lasted for different lengths of time. Lake Uinta was first formed in the late Paleocene around 56 million years ago. It has its origin in what is now the Uinta Basin in Utah, later it expanded further east to Colorado in the Piceance Creek Basin . It is the largest and most southerly lake and existed for the longest, up to the end of the Middle Eocene 45 million years ago. Lake Gosiute extended north of it and filled a large part of today's Green River Basin in southwestern Wyoming (including the Washakie Basin ; both together including some minor basins are also known as the Greater Green River Basin ). It existed from the lower to the beginning of the Middle Eocene. The smallest lake and the one with the shortest lifespan was Fossil Lake, west of Lake Gosiute in what is now the Fossil Basin . It was formed around 52 million years ago in the Lower Eocene and silted up only 2 million years later. Its largest extension was around 1500 km². The Green River lake system provides a portfolio duration of approximately 11 to 12 million years ago one of the most stable known lake systems are. As it reached the age of Lake Tanganyika in East African grave system . The formation of the lakes is related to the Laramian orogeny during which the Rocky Mountains were unfolded. The Uinta Mountains unfolded in the south , the Rock Springs in the east and the Wind River Ranges in the north . Between the individual mountain ranges, wide basins were created that filled with water.

Each of the lakes of the Green River lake system formed its own deposit units, which are structured differently and accordingly named differently. In Lake Uinta, six layers can be distinguished, five in Lake Gosiute and three in Fossil Lake. The deposits mostly consist of clay , silt , sand and limestone . Some of the deposits, especially the limestones, are also enriched with fossil fuels such as kerogen , which suggest around 4.3 trillion barrels in the former Lake Uinta and Lake Gosiute. The average sedimentation rate during the formation of the Green River Formation was 10 to 18 cm annually, the highest occurred in the transition from the Lower to the Middle Eocene around 49 to 47.5 million years ago with around 1 m and more per year as deposits below the Absaroka volcanic field reached the region from the north. The Green River Formation and its strata are partially interrupted by deposits of the Wasatch Formation in the lower area and the Bridger Formation in the upper area, which consist of fluvial or alluvial sediments . This alternating storage sequence consisting of the Green River, Wasatch and Bridger Formation indicates that the lakes of the Green River lake system did not exist permanently, but periodically or episodically fell dry. Especially Lake Uinta and Lake Gosiute can therefore be referred to as Playa or lagoon-like shallow lakes. The Fossil Lake, on the other hand, was a bit more stable in comparison and also significantly deeper than the other two.

Geological structure of Fossil Lake and the Fossil Butte Member

The subsurface of the former Fossil Lake is formed by the main body of the Wasatch Formation, which in turn is stored on Triassic rocks. The sediments deposited during the time of the existence of the Fossil Lake are divided into three layers. At the bottom is the Road Hollow Member, who is also the most powerfully trained. It first emerged in the southern part of the fossil basin as a flood plain that gradually expanded northwards. The greatest thickness is 125 m. Between the Road Hollow Member and the following Fossil Butte Member there is an almost 40 m thick sandstone layer of the Wasatch Formation. The Fossil Butte Member reaches around 22 m in the bank area and around 12 m in thickness in the center of the basin. The reason for these large differences is the higher sedimentation rates on the former lakeshore. For a short time there was a connection to Lake Gosiute, since at the southernmost end of both lakes the Fossil Butte Member is interlocked with the Wilkins Peak Member of Lake Gosiute. The Fossil Butte Member is followed by the Angelo Member, both are partly separated from each other by a clay / siltstone tongue, this time only around 5 to 10 m thick, of the Wasatch Formation. The Angelo Member is followed by alluvial sediments of the Bullpen Member of the Wasatch Formation, which in turn are overlaid by the Fawkes Formation . Overall, the Fossil Butte Member represents the thinnest layer unit of Fossil Lake, which takes up about 9% of the total thickness. Thus, the formation period, based on the approximately 2 million years of existence of Fossil Lake, only covers a few ten thousand years.

While the Road Hollow Member mainly consists of sand, silt and clay stones with thin layers of limestone in between, both the Fossil Butte and the Angelo Member are largely made of limestone, the majority of which is composed of micrites . These limestone sequences are often interrupted by thin layers of tuff of volcanic origin. The basis of the Fossil Butte Members is the so-called Lower Oil shale , a kerogen-rich layer 20 to 30 cm thick that extends through the entire basin. In the southern basin area it lies on the sandstone tongue of the Wasatch Formation. The upper end is marked by an ocher-colored, volcanic tuff. In the Fossil Butte Member the deposits are finely laminated, whereby the thickness of the individual layers is well below 1 mm. The individual laminae largely do not correspond to an annual deposition rate in the sense of varves , but were sedimented at a higher frequency, possibly as a result of seasonal or episodic changes in local weather conditions. Altogether, five different types of facies can be distinguished in the limestone sequence: high-kerogen (KRLM) and low-kerogen laminated micrites (KPLM), partly buried laminated micrites (PBLM), bioturbed micrites (BM) and dolomicrites (DM). In the areas close to the banks, the bioturbated micrites dominate, in the lake basin center the kerogen-poor and -rich micrites.

Within the deposition sequence of the Fossil Butte Member, two very rich areas are distinguished. The sandwich bed layer ( sandwich beds for short ; also called split fish layer , orange fish layer or F-2) is located near the base of the layer member, around 2 m above the lower oil shale . It is about 4 m thick in the bank area, inside the basin it thins to about 2.5 m. The sandwich beds appear as two approximately 15 cm thick layers that are sandwiched between two 1 to 3 cm thick tufa layers and are referred to as lower sandwich beds and upper sandwich beds , with kerogenous sediments between the two layers. All of the deposits here are finely layered with an average thickness of 0.14 mm. The individual layers are usually light in color. A few meters above the sandwich beds is the 18-inch layer (also known as the black fish layer or F-1). Inside the basin it is only 30 to 40 cm thick, which is what the term 18-inch layer refers to. In the basin edge area, this find layer has not yet been clearly observed. It consists of an alternation of light brown to light gray and dark brown layers, whereby these with a thickness of 0.07 mm are only half as thick as those of the sandwich beds . More than 4000 individual layers are formed in the entire layer sequence. The 18-inch layer is covered by kerogen-rich limestone. In the upper area of the Fossil Butte Member there is a third find zone, the Mini fish layer , which was only discovered a few years ago. It is formed just below a striking, narrow tufa layer, the k-spar tuff . The tuff is an orthoclase-rich , volcanic formation, which in turn is located about 3 to 4 m below the ocher-colored tuff.

Fossil sites

Significant fossil sites are concentrated on the shores of the former lake and in the center of the lake basin. In the bank area it is mainly the sandwich beds that are exposed, in the pool interior the 18-inch layer . However, the hanging areas were also reached in places with the mini fish layer . Today there are a total of 14 sites in the form of quarries , which were named in alphabetical order (A to N) and some have been in operation for over 60 years. Significant sites in the riparian zone are on the Thompson Ranch grounds in the northeastern bank area (localities H and M) and near Warfield Springs further south (locality K). On the other hand, the inside of the pool is found on the Lewis Ranch (localities A to D). All of these quarries are privately owned. The state of Wyoming runs or rents its own sites. These include locations E to G in the center of the basin and I and J in the northern bank area. In addition to private and commercial recoveries, universities and other research institutions are also active on site, such as the Field Museum of Chicago and Brigham Young University . Tourists can also take part in some of the privately and officially managed sites.

Finds

Preservation of finds

The preservation of finds in the Fossil Butte Member is exceptionally good, so that numerous complete skeletons of vertebrates along with parts of the soft tissue and also complete remains of invertebrates and plants have come down to us. In addition, all forms of disarticulation up to completely disintegrated skeletons occur, but the latter only comprise 6.8% of the total material, other stages of disintegration a total of 23.3%. The finds run into the millions, with fish being exceptionally common, especially ray fins . It is assumed that there is one terrestrial vertebrate for every 5,000 to 10,000 rayfins found. It is estimated that more than 100,000 fossils are discovered annually, but only half of them are known or sold as the rest are damaged or incomplete. The number of fossils found has increased significantly due to commercial searches. A total of 200,000 finds were assumed for the last quarter of the 20th century.

The unusually good preservation is due to the calcareous deposits of the Fossil Butte Member. The lime comes from the surrounding mountains and was transported into the lake by streams and rivers during the existence of Fossil Lake. As a result, the lake water was saturated with lime , which then precipitated and accumulated on the lake bed. The subsequent pressing due to the sediment load created calcareous rocks, which ensured the good conservation conditions. The fossils are still permineralized , which means that the mineral-rich waters of the Fossil Lake formed crystals in the pores of the bones , which they received down to the cellular level. Mainly it is white or colorless calcite , which received the bones in their predominantly naturally yellowish color. Some fossils, for example from the 18-inch layer in the center of the lake basin and the sandwich beds on the lake shore, are dark to black in color (carbonization) due to the storage of carbon-containing pigments .

flora

Plants are numerous, but so far largely indeterminate. The fossil remains include leaves , pollen , flowers , fruits , twigs, branches and roots. Most of the finds are single and less coherent, which sometimes makes it difficult to assign the different parts of the plant such as leaves, flowers and fruits to one another. The evidence of green algae , including pediastrum , is very important and is one of the primary producers and forms the basis of food for numerous organisms living in the water. Horsetail are rather rare, but proven with Equisetum . The closely related real ferns are more diverse but still seldom . Remnants of spotted ferns , climbing ferns and floating ferns could be recovered. The latter include two freshwater-bound genera, Azolla and Salvinia . Conifers have also been observed rarely so far . However, as a special feature there is a 6 cm long find of a branch with needle-like leaves and berry-like fruits, which was identified as juniper from the cypress family . Far more common are angiosperms found. The laurel , pepper and frog-spoon types are among the more primitive . One of the most common flowering plants at all is to be assigned to the asparagus-like , possibly from the group of the amaryllis family . Several hundred inflorescences alone are known from the 18-inch layer , the individual finds measure between 4.1 and 8.8 cm. Also palmaceae among the regularly discovered plants, including those of the genus Sabalites . Their leaves can sometimes become extremely large, so specimens 4 m in length have been observed. There are also inflorescences. Another common plant is the freshwater inhabitant Ceratophyllum , which is widespread in tropical regions today .

The most diverse group of plants in the Fossil Butte Member are represented by the dicotyledons , of which there are representatives from a good 20 families. Often lotus flowers appear, which are detected via leaves, seed pods and roots. The also quite extensively documented silver trees and plane trees are closely related ; the latter, as tall trees, formed part of the closed forests around Fossil Lake. The same applies to Liquidambar from the group of saxifrage-like , but the species is rare. Also rare are trumpet and aralia plants , both of which are documented by leaves. In addition, there are inflorescences of up to 57 cm in length in the Aralia family. Particularly impressive are the fruit clusters of musk herbs with fruits from 0.8 to 1 cm in diameter. Leaf finds have not yet been proven. Furthermore, there are several types of Populus from the group of willow plants , which is evident from the differently shaped leaves. Legumes have so far been identified in three species: one from the genus Swartzia and one from the genus Parvileguminophyllum . A third is still undescribed, but includes only one, but relatively complete, plant. Nettle plants from the rose-like group are also singularly covered with only one 15 cm long leaf. In contrast, the related elm family occurs more frequently , including Cedrelospernum , which left fruits and leaves. In Fossil Lake, however, in contrast to finds from Lake Uinta, both do not occur together. Among the beech-like , the walnut family with Platycarya and Gagelstrauchgewächse with Comptonia stand out. They can often be found on the remains of branches, the former also on leaves. From myrtle plants such as Psidium , on the other hand, only seed capsules have so far been found that are found in large numbers. The soap tree-like have three families in the Fossil Butte Member. So include Rhus and Astronium to Sumachgewächsen . From Astronium , flowers with a diameter of 4 to 6 cm are known. The soap tree plants are also represented by several genera, none of which have been investigated in more detail. So far only one fruit of 6.5 cm in size has been found by Koelreuteria . Other forms that occur are Sapindus and Dipteronia . One of the most common plants of the Fossil Butte Members is Ailanthus from the bitter ash family, the finds of the Fossil Butte Members are among the oldest records in North America. The genus is passed down through up to 13 cm long leaves and numerous winged seeds. Close relatives are Chaneya , a plant that is characterized by five-leaved, flower-like fruits measuring around 3 cm. The Mallow be with Florissantia represented by a single flower. In its systematic vicinity belongs Sterculia , a very common plant that is characterized by three-pronged leaves. In addition, there are still numerous undescribed finds, as well as those whose exact family relationships are unclear, such as Lagokarpos . This plant is known for its numerous seeds, whose attached wing leaves also earned them the name "rabbit ears".

fauna

Invertebrates

Invertebrate remains are quite common in Fossil Butte Member, but overall rarer than in the deposits of Lake Gosiute and Lake Uinta. Most of the finds have not yet been scientifically processed. Spiders in the Fossil Butte Member include crab spiders , jumping spiders and wolf spiders , all of which were quite small with body lengths of 8 to 15 mm. Mostly from the Sandwich beds come decapods , of which up to now the genus Procambarus and Bechleja described from the Fossil Butte Member, the latter was up to 8.6 cm. Among the ostracods is Hemicyprinotus from the group of Cyprididae represented whose shells often only 1 mm in size were. Millipedes are generally rare . Insects are the most common and diverse . Finds of several complete dragonflies are important here, some of which still have fine veining of the wings. Locusts and stone flies are rare, but nymphs have also come down to us. Among the Schnabelkerfen are sandpipers very common, mainly engaged in inch 18-layer occur frequently. The beetles have been passed down in many ways. These include, above all, the jewel beetles , which can be found with specimens up to 5 cm long. Other beetles that occur include ground beetles , weevils and Cupedidae . Hymenoptera have been identified with wasps , bees and ants , the former with three families: the wasps , the parasitic wasps and the dagger wasps . Ants occur with queens and workers, but flightless representatives are rare and mostly washed in by streams. There are also butterflies , which are among the oldest finds in the world. The most common insects of the fossil butte member are the flies from the group of two-winged birds . More than 80% are caused by hair gnats of the genus Plecia , one of the few validly described forms of the fossil butte member. The mass occurrence suggests that they appeared in swarms back then, like today's representatives. Furthermore, gnats , dixidae or fungus gnats handed. So far, the molluscs appear with few species . These include snails such as Goniobasis from the group of the Pleuroceridae and Viviparus , a swamp snail . Up to now, only river and pond mussels (Unionidae) have been identified among the mussels .

Fish and amphibians

The most extensive finds so far were provided by the fish , the remains of which literally run into the millions. Complete individuals predominate, most of which still have fine fish scales. Cartilaginous fish are indicated by two genera of stingray , Heliobatis and Asterotrygon . From both representatives, both old animals with a total length of more than 65 to 90 cm and much smaller young animals are known, as well as two fish that are probably just mating. Asterotrygon has a thicker tail than Heliobatis and is significantly rarer with 30 compared to 1000 specimens. All other fish belong to the ray fins . Sturgeon species are relatively rare and primeval because they belong to the cartilaginous organoids . The only genus represented here, Crossopholis , fed on other fish, as can be interpreted from the structure of the teeth and some food remains. Bone organoids have been detected , among other things, by the fish-like species. These include several genera with Lepisosteus , Atractosteus and Masillosteus . The last one is extremely rare with around 8 proven specimens so far. Atractosteus , on the other hand, has 300 fossil finds and, with a body length of 1.6 to 2 m, is one of the largest fish of the fossil butte member. Amia and Cyclurus , on the other hand, are close to today's bald pike . The representatives of the first genus were also quite large with a total length of around 1.4 m.

All other fish of the Fossil Butte Member can be referred to the real bony fish . Moon eyes are covered with Hiodon , but so far only occur in the former northern part of the lake, where a tributary may have flowed into it. The largest specimens found measured 25 cm. Closely related to these are the bone-wolf-like . Phareodus impresses with its highly developed pectoral fins, a set of large teeth and scales with reticulated patterns. Noteworthy finds here represent individuals who died and fossilized at a time when they were trying to swallow other fish. The herring-like and related groups form a great wealth of shapes and individuals . The larger family group includes Diplomystus , who is the second most common fish in the Fossil Butte Member with over 350,000 individual finds. He has found individuals in the embryonic stage up to fully grown, 65 cm long old animals. Closer to the herrings is Knightia , the most common fish representative with an estimated 650,000 individuals. It formed a central part of the food web in Fossil Lake and was evidently found in schools. Here, too, all stages of growth are fossil evidence, large adult animals measured up to 26 cm. The genus occurs here with two species and is also the first scientifically described fish in the entire Green River Formation. Another fish that is widely related to herrings is Notogoneus from the group of sandfish-like fish . Its deep-set mouth indicates a type of diet that is looking for the seabed. With a 12 cm long specimen previously detected only is the singular to the Hecht-like scoring Esox . The species found is in direct line with the American and chain pike and thus not with the actual pike , as a river inhabitant it probably rarely visited the lake. Amphiplaga , a fish representative only 14 cm long, is the oldest member of the bass line . The perch relatives represent another extensive group of fish. Mioplosus , whose systematic position within the perch relatives is not yet clear, represents the largest representative with body lengths of up to 40 cm. In addition, it occurs relatively frequently with around 30,000 finds. He was predatory, his prey included Diplomystus . The sea bass include two genera in the Fossil Butte Member, Priscacara and Cockerellites , which are also relatively common with 8,000 and 30,000 finds, respectively. From a phylogenetic point of view, they are close to the base of the Percoidei . Another perch relative could be described with the rarer and only 9 cm long Hypsiprisca , whose exact family assignment is currently unclear. Asineops appears enigmatic and has not yet been assigned to one of the known fish orders. The rare, up to 33 cm long fish was characterized among other things by a massive head and a very large mouth that could be opened very wide and only contained small teeth. In addition to the perch relatives already mentioned, a closer relationship with the bearded fish and glossy fish-like fish comes into consideration.

Amphibians are extremely rare and only occupied by two genera. Paleoamphiuma one of the Armmolchen , the present, 36 cm long skeleton is characterized by sharply formed front and rear legs and a toothless jaw, but the skull is received incomplete. The second genus, Aerugoamnis , represents the frogs . It is related to today's mud divers , who are recently only documented from Europe, but fossilized also appeared in North America. The roughly 4 cm long skeleton is one of the most complete of a frog from the Eocene.

Reptiles

A total of around twelve genera of reptiles have been identified so far . The find material of the turtles , consisting of numerous complete skeletons , which all represent freshwater inhabitants , is very extensive . The remains can be attributed to representatives of two sub-orders, the Halsberger tortoises and the closely related, but extinct Paracryptodira . The latter could not retract their head into the shell, which is why the skeletons are often passed down with the skull protruding from the shell. The Baenidae family, which is indicated in the Fossil Butte Member by two genera, Baena and Chisternon, is significant here . The members of the first genus reached total lengths of 11 to 37 cm, those of the second from 1.3 m, which were significantly larger. Most of the animals lived at the bottom of the lake. Within the cryptodira forming soft-shelled turtles , the largest group of finds. With Apalone , Axestemys and Hummelichelys , at least three genera are known. Axestemys delivered the largest specimens to date, which are up to 1.8 m long and have a poorly ornamented armor. Baptemys, in turn, represents the Central American river turtles , which also include today's Tabasco turtle , but is extremely rare. It reached a shell length of 60 cm, and young animals with a length of 14.5 cm have also been detected. The New World pond turtles , which occur in the Fossil Butte Member with one genus, Echmatemys , are also rare . These are small animals with a length of about 20 cm.

Finds of snakes are extremely rare. Three specimens have so far been observed by Boavus , a smaller member of the boas family , whose lengths vary between just under one to 1.2 m. The largest member of the Squamata forms Saniwa that the monitor lizards counts. Two almost complete skeletons with a total length of just over 1.3 m are known. The spine alone comprised over 140 vertebrae, 109 of them on the tail, which measured 89 cm. According to recent studies, Saniwa is one of the closest relatives of the recent genus Varanus . One 33 cm long, complete skeleton and one without a skull represent Bahndwivici , a member of the Shinisauridae . Its spine comprises 57 vertebrae, 38 of which are on the tail. Ossified skin platelets ( osteoderms ) are also preserved here. Afairiguana from the group of iguanas was rather small, only about 10 cm long and related to the Polychrus native to Central and South America . The crocodiles comprise two genera. Borealosuchus is relatively primitive , with a total length of over 4 m it is not only the largest armored lizard, but also the largest predator of the Fossil Butte Member. Several complete skeletons and also isolated skulls have come down to us. Tsoabichi , a relative of the caimans , was significantly smaller and only reached three quarters of a meter in length. The body armor can still be seen on some of the very well-preserved skeletons.

Birds

With almost two dozen genera from around a dozen orders, the birds are very well documented. The primeval jawbirds are only represented by the Lithornithidae , which are possibly flighty precursors of today's large ratites such as the ostriches . These long-legged and long-beaked birds have been identified with two genera. From Pseudocrypturus least two complete skeletons and a skull are. The genus Calciavis is also based on two skeletons, one of which is almost complete and still contains soft parts such as feathers and claws. All other finds are to be assigned to the new pine birds , whereby both water and land-dwelling representatives have been proven. The Galloanserae form a large group of new pine birds . These include Gallinuloides , one of the earliest representatives of the chicken bird . Several skeletons of this land bird were found in central areas of the former lake basin and suggest that the animals crossed the open water surface. The most common bird finds include those of Presbyornis , whose bones are found by the thousands along the shoreline. A fully articulated skeleton has not yet been recovered in the Fossil Butte Member. The bird, equipped with the body of a flamingo and the head of a duck, is referred to the geese birds and colonized the former lakeshore, which is also indicated by numerous fragmented eggs.

All other fossil finds are counted among the Neoaves . The Schwalm-like comprise three families. Fluvioviridavis , a short-legged land bird, is related to the owl swallow and is a very original member of the swallow. It has been scientifically described using a complete, but slightly dislocated skeleton from the Fossil Butte Member. Eocypselus occupies a middle position between the hummingbirds and the sailors, among other things in the type of wing design . With a skull length of only 2.3 cm, this is one of the smallest birds in the Fossil Butte Member and has been passed down through several complete skeletal finds, including one with excellent feather preservation. The rather short beak suggests an insect eater. One of the rare fossil records of the fat swallow is with Prefica . Like this, the fossil form mainly fed on fruits, but whether it also emitted echolocation calls for orientation, analogous to its modern relatives , is not clear. The rudder pods are represented by Limnofregata , a primitive member of the frigate birds . At least half a dozen skeletons and skulls were found from him, as well as feather prints. Here, fed the big bird, the m a wingspan of 1.1, reaching more, probably mainly from the numerous proven fish of the genus Knightia also heard in the closer relationship Foro which the turacos close stands, but so far only by a skeleton known . Another group of shapes are the rails . Among these is the Messelornis, next to the Presbyornis, one of the most common bird representatives, who can show more than a dozen complete or partially preserved skeletons, some of them with traditional feathers. These “Messelrallen”, named after the Messel mine in Hesse, show two different sizes that may represent male and female animals. Another railing bird, which has not yet been investigated in more detail, probably belongs to the Salmilidae family and was unable to fly due to the very few wings.

In the group of woodpeckers there is the Jakamare- like Neanis , who has a zygodactyl foot, that is, two toes looked forward and two backward, which suggests good gripping abilities. Rocket birds occur in a greater variety. A skeleton of a representative of the hoopoes or of the closely related, but extinct Messelirrisoridae has not yet been identified . Primobucco is also referred to as being closely related . It has been proven by at least 20 skeletons and, with a head length of 4 cm, is considered to be one of the smallest members of the root group of the Racken. Plesiocathartes, in turn, can be brought into closer connection with the Kurols and was originally only known from Europe. The mouse birds comprise at least two genera in the Fossil Butte Member. Celericolius was a small bird with a skull length of only 3.6 cm. In contrast to today's representatives of the order, it had significantly longer wings, which is also indicated by the traditional, up to 12 cm long hand wings, and was therefore possibly a better flier. However, the typical long tail appeared, with feathers up to 18 cm long. The bird genus was much closer to today's mouse birds than its relative Anneavis , who represents the parent group. However, it has only come down to us on a skull-less skeleton, which, however, also has feathers. The fossil remains of the parrots , which are among the oldest in the world and can be referred to at least three genera, are also important. These include the more primitive forms Cyrilavis and Tynskya and the genealogically somewhat more developed Avolatavis , which is closer to today's parrots. As a result, the parrots already show quite a high diversity in the Fossil Butte Member. However, all early forms have the simple, straight beak in common, which indicates that the diet was not yet so highly specialized. Several skeletons are referred to the broader kinship of the passerine birds , whose parent group has so far only been poorly recorded in fossil form. With Eozygodactylus , Zygodactylus and Eofringillirostrum there are three representatives. What they have in common is the zygodactyle foot structure. These primitive passerine birds thus deviate from today's forms, in which the foot is usually designed anisodactyl (with three toes pointing forward and only one to the rear). Eofringillirostrum also had a beak comparable to that of finches and probably ate hard-shelled seeds, which is one of the earliest evidence. A well-preserved skeleton has almost full plumage. According to this, the inner wing of the hand of Eofringillirostrum reached almost half of the wing length, while the tail took up a good third of the entire body length. There is also a lot of unwritten finds, such as a possible bird of prey and long-beaked animals.

Mammals

Mammals are comparatively rare so far, but are also characterized by predominantly complete skeletons. Almost ten genera are currently known that represent several large groups of forms. Some insectivore-like forms are added to the Ferae , to which today's carnivores also belong . These include palaeosinopa from the Pantolesta group , of which three almost complete skeletons have been passed down, including that of a young animal. The representatives were altogether up to 1 m long and lived semi-aquatic as predators near water, whereby they occupied the ecological niche of today's otters . Trees, on the other hand , lived in Apatemys , a member of the Apatotheria , which was only 35 cm long and was characterized by greatly elongated middle fingers analogous to the finger animals and an extremely long tail, which were ideal for climbing. A representative of the Cimolesta, which has not yet been precisely identified, also lived in the trees . This also long-tailed animal had 45 caudal vertebrae, a high number that only a few mammals can achieve today. With Hyopsodus , which is referred to the condylarthra , a mammal that lives burrowing in the ground because of its short and strong legs is known. There are also two representatives of the odd ungulate . Lambdotherium is only covered with a few fragmented remains, including a skull. It is a small predecessor of the Brontotheriidae , which flourished in the Middle and Upper Eocene. Closely related is Protorohippous , a primordial horse that has one of the most complete skeletons of earlier members of this group, with a skull about 15 cm long. Bats come with two genera before the skeletons of which are also among the most extensive. Onychonycteris , which is known about two individuals and still had claws on all wing fingers , appears very primeval. As a result, the approximately 40 g heavy animals were possibly agile climbers. With their approximately 30 cm long wings, whose area only took up around 17 cm² each, they probably managed their flights in a combination of fluttering and gliding. They looked for food, mostly insects, with their eyes, as the structure of the ossicles did not allow echolocation . The second genus is Icaronycteris , which is much more developed due to the reduction in finger claws. In addition, the animals already had echolocation. The estimated body weight of the animals was just under 14 g, the wing length was comparable to that of Onychonycteris .

Soft tissues, food scraps and trace fossils

Remains of the soft tissue , which generally rarely fossilizes, have also survived, often in the form of remains of feathers . These are partly in the skeletal structure, predominantly in the central pelvic deposits. On the basis of the found feathers of Eocypselus , in addition to an existing headdress and very long hand wings , a partly black coloration of the plumage could be shown. In addition, however, isolated springs are also known. A 24 cm long specimen is attributed to a large ratite, such as Gastornis (also called Diatryma ), which has not been proven via skeletal material. Traditional food remains were found in the gastrointestinal area of numerous fish, but also some mammals. For example, numerous bones from the Pantolest Palaeosinopa could be recognized as the remains of fish. In the bat Icaronycteris , fish scales were found in the gastrointestinal area, while a single coprolite in the pelvic area contained chitin sheaths from insects and plant material. Both Icaronycteris findings do not contradict each other, as the dentition advocates an omnivorous diet. In general, coprolites are among the most common trace fossils and were often found in connection with fish, and also with crocodiles. A special feature are traces of fish looking for food on the lake floor, which have a serpentine pattern and are associated with Notogoneus . Individual burial tunnels, especially on the lakeshore, can usually be assigned to small animals such as worms due to their small size.

Dating

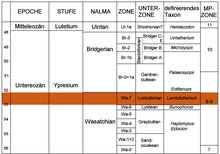

The composition of the mammalian fauna is important for the relative dating of the fossil butte member. Statements about the age of a site compared to others can be made about the appearance or disappearance of certain forms and also about their anatomical changes over time, usually recognizable by the teeth, a process known as biostratigraphy . Significant for the Fossil Butte Member is the occurrence of the odd- toed ungulate Lambdotherium , which is considered a key fossil in North America and indicates the local stratigraphic level of North American land mammals (NALMA = North American Land Mammal Ages ) Lostcabinium . The subsequent Gardnerbutteum is characterized by the occurrence of the Brontotherien representative Eotitanops , which is later replaced by his successor Palaeosyops . In the previous Lysetium , the arthropod Bunophorus represented the character form. The Lostcabinium, named after the Lost Cabin Member of the Wind River Formation in Wyoming, where Lambdotherium is a typical evidence, is in turn a subunit of the North American fauna level Wasatchium from about 56 to Dated 52.1 million years ago. Accordingly, the Wasatchian can roughly be assigned to the lower section of the geochronological stage of the Ypresian (about 56 to 47.8 million years ago) within the Lower Eocene series , which covers the same period. The Wasatchium is regionally divided into 8 phases (Wa-0 to 7), of which the Lostcabinium occupies the uppermost (Wa-7). This phase lasted from 53 to 52.1 million years ago, which can be taken as an approximate age classification of the Fossil Butte Member.

Only a few absolute age dates from the Green River Formation are available, but data from the orthoclase-rich , volcanic tuff (k-spar tuff) near the upper edge of the Fossil Butte Member were obtained using the potassium-argon method . These resulted in an age of 51.66 million years and, according to today's criteria, should be 51.97 million years. Since the dated tuff lies above the layers in which it is found, the value represents the minimum age (terminus ante quem) and thus confirms the biostratigraphic age estimate.

Landscape reconstruction

In contrast to the dry and winter cold conditions of the region today with an average altitude of 2100 m above sea level, Fossil Lake existed at a significantly lower altitude under tropical and subtropical climates. Corresponding conditions can be found today on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico . The warm climate is indicated above all by the numerous palm and soap tree plants , as well as by the crocodiles and monitor lizards . The herring fish Knightia played a central role in the lake. It was found in large schools and lived as the primary consumer of the numerous green algae. It served as a food basis for secondary consumers such as Crossopholis , Lepisosteus or Amia , who in turn were eaten by tertiary consumers, the crocodiles, monitor lizards or trionychid turtles .

Was that the lake in principle süßwasserhaltig show besides some fish such as the aforementioned Crossopholis and Amia especially the molluscs Goniobasis and Viviparus to like insects, the dragonfly and also enjoy various aquatic plants, such as the epidermis . However, the formation of dolomite and salt minerals indicate temporary salinity, but hardly any fossils have been preserved in this area. It was only in the overlying Angelo Member that the lake became completely salinated, which led to the extinction of the entire fish fauna there. Occasionally, however, within the Fossil Butte Member, there was evidence of mass extinction of fish, including Knightia , Mioplosus and Cockerellites . This can be observed particularly well at the base of the 18-inch layer , and in the Mini fish layer , where hundreds of fish lie in an area of just one square meter. Some of these fish deaths can be traced back to volcanic activity in the near or far , such as cockerellites , whose mass occurrence lies beneath a volcanic ash. Others may be related to short-term changes in water chemistry due to the abundance of algae. This could affect Knightia , for example , as herrings are very sensitive to environmental changes.

The lake was fed by individual streams and rivers, as the Esox find indicates. Water plants such as sea lilies and swimming ferns existed near the lake shore , between which schools of juvenile fish could hide. The Ufersaum served some birds like presbyornis as a breeding site. Palm forests grew on the shore, the trees of which were used by birds and tree-climbing mammals. The abundant world of insects served them as well as the amphibians and smaller scale creeps as a food basis. The plants in the undergrowth were largely used by the identified unpaired ungulates, although semi-aquatic predators such as Palaeosinopa also went on prey in the bank area .

Comparison with simultaneous sources

Fossil finds are known from the entire Green River Formation, but the Fossil Butte Member contains, among other things, the most comprehensive material in terms of the richness of shapes of the aquatic creatures and exceeds all other 13 layers of the formation taken together. In the lying Road Hollow Member, fish remains appear in the middle section, which include Knightia , Diplomystus and Priscacara . In addition, there are individual crocodile teeth, remains of turtles, birds and mammals. The hanging Angelo Member also contains occasional fish finds, in addition to turtle, crocodile and bird remains as well as undetermined mammal bones. The invertebrates are made up of molluscs and shellfish. However, since the Fossil Lake was very saline at the time the Angelo Member was formed, a large part of the aquatic fauna died out.

Numerous finds also come from Lake Gosiute and Lake Uinta, but usually the fossils are not as complete as those of the Fossil Butte Member. In several sections of the sediment sequence of Lake Gosiute, silicified wood and trunk remains were found, which indicate a multiple transgression and regression of the former water level. Some of the aquatic species could possibly switch between the two lakes during the short-term connection of Fossil Lake with Lake Gosiute, but these also died in Lake Gosiute due to increasing salinity during the formation of the Wilkins Peak Member or migrated into the fresh water of the incoming rivers. The Laney Member, which is the uppermost section of the Green River Formation in Lake Gosiute and, with a radiometrically dated age of around 49 million years, belongs to the beginning of the Middle Eocene, and is therefore younger than the Fossil Butte Member, proved to be important. In addition to numerous insects, including ants , a fish fauna occurs that is fundamentally different from that of the Fossil Butte Member and contains only a few common forms, such as the already mentioned Knightia and Diplomystus as well as Amia and Phareodus . Deviating here, among other things, Gosiotichthyes , one of the dominant forms with thousands of finds, and Erismatopterus occur. Some complete skeletons are available from a frog, which can probably be assigned to Eopelobates , and from various reptiles, mostly crocodiles and turtles, such as von Trionyx . In addition, much of the found material of the Presbyornis bird known from the Green River Formation comes from here. In contrast, mammal finds are very rare. However, in the edge area of the Green River Basin there are numerous outcrops with rich but small pieces of finds, such as near Little Muddy Creek in the southwest. In addition to unidentified remains of fish and birds, these include at least 12 genera of reptiles and 23 of mammals. They can be assigned to different biostratigraphic positions. The oldest fauna association (Little Muddy I) is around the same time as the Fossil Butte Member and also belongs to the Lostcabinium due to the occurrence of Lambdotherium , but the finds come from a local variant of the Wasatch Formation. The youngest fauna community (Little Muddy VII) , on the other hand, corresponds to the outgoing bridgerium of the bridger formation . Of the finds found, those of Little Muddy III , Little Muddy V and Little Muddy VI can be directly correlated with the Green River Formation of Lake Gosiute. Particularly noteworthy is the occurrence of early primates such as Omomys , Washakius or Notharctus , which are not found in the Fossil Butte Member. This also applies to other modern lines of development of the higher mammals, such as the cloven-hoofed animals , which are represented by Diacodexis and Bunophorus , or the rodents with Paramys and Knightomys . Other significant outcrops can also be found in other areas of the Green River Basin. The region around the New Fork River and the Big Sandy River , two tributaries of the Green River in the northeastern part of the basin, from which more than 1200 mammal remains originate, should be emphasized . While the finds from the Laney Member are extremely fragmented and hardly identifiable, the predominant and identified material belongs to the foothills of the Wasatch Formation in the horizontal and the Bridger Formation in the hanging wall. The fauna spectrum is similar to that in the southwestern basin area. Overall, the individual occurrences often occur in a rather isolated manner and their relationships to one another have not yet been fully clarified.

Lake Uinta, on the other hand, had the lowest diversity of all three lakes, including all vertebrate groups, with only a few shapes. The most important layer member here is the Parachute Creek Member, which forms the upper end of the local sequence of the Green River Formation and is to be assigned to the late Middle Eocene. So far, only six to eight species have been detected in fish. However, two complete frog skeletons with preserved skin remains should be emphasized, from which one individual had just escaped metamorphosis . Some skeletons and partial skeletons of scale reptiles have also been documented, including a relative of the Chinese crocodile tail lizard with exquisitely traditional scale skin . A complete but poorly preserved bat skeleton stands out among the mammals. Also noteworthy are proven trace fossils of birds and mammals that were found in Parachute Creek Member and further in one of the lying sections. The mammalian tracks represent the remains of three-toed animals, which may be attributed to smaller odd- toed ungulates , possibly an early representative of the three-toed horse. In addition to the vertebrate fauna, which is rather poor in shape, a very extensive and significant invertebrate fauna has been handed down. This includes Miagrammopes and Hersiliola as representatives of the spiders, Gyaclavator as a member of the bed bugs , Agulla from the group of camel neck flies or, with Colemanus , hymenoptera . There is also a rich flora.

Research history

The beginning in the 19th century

The exploration of the Green River Formation dates back to the early 19th century. In 1840 a missionary named S. A. Parker reported about insect finds. Sixteen years later the geologist John Evans first discovered a fossil fish in what is now Laney Member of Lake Gosiute, which he sent to Philadelphia to see Joseph Leidy (1823-1891), one of the founders of paleontology in North America . He identified the fish as herring and named it Clupea humilis . The fish was later renamed Knightia eocaena because the previous name was already occupied by another species of fish. Leidy had described one of the most common fish finds in the Green River Formation, the species was later discovered in the Fossil Butte Member. The earliest finds from the Fossil Butte Member described Fielding Bradford Meek (1817–1876) in 1870, which were molluscs that came from Fossil Hill , later renamed Fossil Butte and today the type locality and namesake of the Fossil Butte Member . The year before, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden had already briefly mentioned the rock units of the Green River and Wasatch Formations for the fossil basin, which became the basis for further geological work in later times. Albert Charles Peale (1849–1914), who accompanied several expeditions from Hayden to the Rocky Mountains, then a decade later presented a first detailed description of the sequence of layers on the Fossil Butte and briefly discussed the fish fossils known up until then. Also in the late 1870s Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897) collected various vertebrates, mostly fish, on the Twin Creek Site of Fossil Lake, the scientific analysis of which he published from 1877 onwards. In total, Cope named more than 30 species of fish from the Fossil Butte Member, 14 of which are still recognized today. In 1895, Cope sold his entire fossil collection, comprising around 13,000 objects, to the American Museum of Natural History , including 150 fossil remains from the Fossil Butte Member.

The Cope-Marsh feud , also known as Bone Wars , which Cope and his rival Othniel Charles Marsh (1832–1899) fought over prestigious fossils , also fell into this early phase of research . However, the Fossil Butte Member was only a minor episode and concerned the stingray Heliobatis . This had already been described by Marsh in 1877, while Cope suggested the name Xiphotrygon for the same genus in 1879. After the feud gradually subsided, only a few researchers dealt with the Fossil Butte Member in the late 19th century, for example Alpheus S. Packard with decapods in 1880, Léo Lesquereux with plants in 1887, and Samuel H. Scudder with insects in 1890 and Charles R. Eastman with birds and fish in 1900.

Commercial digs

Since the beginning of the 1870s, the outcrops of the Fossil Butte Member have been visited by various commercially active graves and fossil collectors. These include A. Shoomaker, who sold finds to Marsh in 1877, and Chas Smith, who dug in the 1880s. At the end of the 19th century and beyond, several families established themselves, some of whom spent several generations looking for different sites. The first was the Haddenham family, who moved to the Fossil Lake area around 1880. David Haddenham first accompanied Robert Lee Craig to the 18-inch layer around 1918 , who had been working here since 1897. He was followed by his son and grandson until the 1970s. The Carl and Shirley Ulrich family started their search in 1947 and continue to do so today. They were also among the first to use modern preparation tools and procedures. In the 1970s, Sylvester Tynsky and his sons established themselves with fossil searches in the Fossil Butte Member, where they worked in the sandwich beds and are still in the fourth generation today. Other important families that became active around the same period include those of Virl and Shirley Hebdon and those of Tom Lindgren.

Found presentation

Due to the fact that numerous finds are salvaged, restored and then sold by private entrepreneurs, many finds, including some of the best from the Fossil Butte Member, can be viewed in museums worldwide. The largest collection is in the Field Museum in Chicago , which has been conducting field research on site for several decades. The outstanding importance of the Fossil Butte Member was officially recognized in 1972 with the establishment of the 33.2 km² Fossil Butte National Monument . The visitor center there, which is around 430 m² in size, also shows significant finds from the shift unit.

literature

- Lance Grande: The lost world of Fossil Lake. Snapshot from deep time. University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2013, ISBN 978-0-226-92296-6 , pp. 1-425.

- JP Graham: Fossil Butte National Monument. Geologic Resources Inventory Report. Natural Resource Report NPS / NRSS / GRD / NRR — 2012/587. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado 2012 ( online ).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e M. Elliot Smith, Alan R. Carroll, Brad S. Singer: Synoptic reconstruction of a major ancient lake system: Eocene Green River Formation, western United States. Geological Society of America Bulletin 120 (1/2), 2008, pp. 54-84.

- ↑ a b c d e f H. Paul Buchheim, Robert A. Cushman Jr., Roberto E. Biaggi: Stratigraphic revision of the Green River Formation in Fossil Basin, Wyoming: Overfilled to underfilled lake evolution. Rocky Mountain Geology 46 (2), 2011, pp. 165-181.

- ↑ a b J. P. Graham: Fossil Butte National Monument. Geologic Resources Inventory Report. Natural Resource Report NPS / NRSS / GRD / NRR — 2012/587. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado, 2012.

- ^ Lance Grande: The Eocene Green River Lake System, Fossil Lake, and the history of the North American fish fauna. In: J. Flynn (Ed.): Mesozoic / Cenozoic Vertebrate Paleontology: Classic Localities, Contemporary, Approaches. American Geophysical Union, 1989, pp. 18-28.

- ↑ a b c Lance Grande, H. Paul Buchheim: Paleontological and sedimentological variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30 (1), 1994, pp. 33-56.

- ^ A b c d John-Paul Zonneveld, Gregg F. Gunnell, William S. Bartel: Early Eocene fossil vertebrates from the Southwestern Green River Basin, Lincoln and Uinta Counties, Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (2), 2000, pp. 369-386.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 1–16.

- ^ US Department of the Interior / US Geological Survey: Assessment of In-Place Oil Shale Resources of the Green River Formation, Greater Green River Basin in Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah. Oil Shale Assessment Project Fact Sheet 2011 ( [1] ).

- ^ A b c H. Paul Buchheim: Paleoenvironments, lithofacies and varves of the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation, Southwestern Wyoming. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30 (1), 1994, pp. 3-14.

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 371–379.

- ^ Samuel P. Sullivan, Lance Grande, Adrienne Gau, Christopher S. McAllister: Taphonomy in North America's Most Productive Freshwater Fossil Locality: Fossil Basin, Wyoming. Fieldiana Life and Earth Sciences 5, 2012, pp. 1-4.

- ↑ a b c d e Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 97–182.

- ↑ a b c d e f Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 351–364.

- ^ John Strong Newberry: Brief description of fossil plants, chiefly Tertiary, from Western North America. Proceedings of the US National Museum 5, 1883, pp. 502-514.

- ↑ Patrick S. Herendeen, Donald H. Les, David L. Dilcher: Fossil Ceratophyllum (Ceratophyllaceae) from the Tertiary of North America. American Journal of Botany 77, 1990, pp. 7-16.

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 279-305.

- ↑ Steven R. Manchester: Attached Reproductive and Vegetative Remains of the Extinct American-European Genus Cedrelospermum (Ulmaceae) from the Early Tertiary of Utah and Colorado. American Journal of Botany 76 (2), 1989, pp. 256-276.

- ^ Sarah L. Corbett, Steven R. Manchester: Phytogeography and Fossil History of Ailanthus (Simaroubaceae). International Journal of Plant Sciences 165 (4), 2004, pp. 671-690.

- ↑ Danette M. McMurran, Steven R. Manchester: Lagokarpos lacustris, a New Winged Fruit from the Paleogene of Western North America. International Journal of Plant Sciences 171 (2), 2010, pp. 227-234.

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 307-344.

- ^ Alpheus S. Packard: Fossil Crawfish of the Tertiaries of Wyoming. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 5, 1880, pp. 435-436.

- ↑ Rodney M. Feldmann, Lance Grande, Cheryl P. Birkhimer, Joseph T. Hannibal, David L. McCoy: Decapod Fauna of the Green River Formation (Eocene) of Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 55 (4), 1981, pp. 788-799.

- ^ Samuel H. Scudder: The tertiary Insects of North America. US Geologic and Geographic Survey of the Territories, Report 13, 1890, pp. 1-734 (pp. 585-586).

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 57-93.

- ↑ Marcelo R. Carvalho, John G. Maisey, Lance Grande: Freshwater stingrays of the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Early Eocene), with the description of a new genus and species and analysis of ist phylogenetic relationships (Chondrichthyes: Myliobatiformes). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 284, 2004, pp. 1-136.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lance Grande: Paleontology of the Green River Formation with a review of the fish fauna. The Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 63, 1980, pp. 1-333.

- Jump up ↑ Lance Grande: Eohiodon falcatus, a new species of hiodontid (Pisces) from the Late Early Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 53, 1979, pp. 103-111.

- ↑ Louis Taverne: New insights on the osteology and taxonomy of the osteoglossid fishes Phareodus, Brychaetus and Musperia (Teleostei, Osteoglossomorpha). Bulletin de L'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 79, 2009, pp. 175-190.

- ↑ Lance Grande: A Revision of the Fossil Genus Diplomystus, With Comments on the Interrelationships of Clupeomorph Fishes. American Museum Novitates 2728, 1982, pp. 1-34.

- ↑ Lance Grande: A Revision of the Fossil Genus Knightia, With a Description of a New Genus From the Green River Formation (Teleostei, Clupeidae). American Museum Novitates 2731, 1982, pp. 1-22

- ↑ Lance Grande, Terry Grande: Redescription of the type species for the genus † Notogeneus (Teleostoi: Gonorynchidae), based on new, well-preserved material. Journal of Paleontology 82, Supplement Memoir 70, 2008, pp. 1-31.

- ↑ Lance Grande: The first Esox (Esocidae: Teleostei) from the Eocene Green River Formation, and a brief review of esocid fishes. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19 (3), 1999, pp. 271-292.

- ^ A b Donn Eric Rosen, Colin Patterson: The structure and relationships of the Paracanthopterygian fishes. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 141, 1969, pp. 357-474.

- ^ John A. Whitlock: Phylogenetic Relationships of the Eocene Percomorph Fishes † Priscacara and † Mioplosus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (4), 2010, pp. 1037-1048.

- ↑ Olivier Rieppel, Lance Grande: A Well-Preserved Fossil Amphiumid (Lissamphibia: Caudata) from the Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18 (4), 1998, pp. 700-708.

- ↑ a b c Amy C. Henrici, Ana M. Báez, Lance Grande: Aerugoamnis paulus, New Genus and New Species (Anura: Anomocoela): First Reported Anuran from the Early Eocene (Wasatchian) Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation, Wyoming. Annals of Carnegie Museum 81 (4), 2013, pp. 295-309.

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 185-188.

- ^ Eugene S. Gaffney: The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 147, 1972, pp. 241-320.

- ↑ a b Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 189–213.

- ↑ Oliver Rieppel, Lance Grande: The anatomy of the fossil varanid lizard Saniwa ensidens, based on a newly discovered complete skeleton. Journal of Paleontology 81 (4), 2007, pp. 643-665.

- ↑ Jack L. Conrad, Oliver Rieppel, Lance Grande: Re-assessment of varanid evolution based on new data from Saniwa ensidens Leidy, 1870 (Squamata, Reptilia). American Museum Novitates 3630, 2008, pp. 1-15.

- ↑ Jack L. Conrad: An Eocene shinisaurid (Reptilia, Squamata) from Wyoming, USA. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (1), 2006, pp. 113-126.

- ↑ Jack L. Conrad, Oliver Rieppel, Lance Grande: A Green River (Eocene) polychrotid (Squamata: Reptilia) and a re-examination of iguanian systematics. Journal of Paleontology 81 (6), 2007, pp. 1365-1373.

- ^ Christopher A. Brochu: A New Alligatorid from the Lower Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming and the Origin of Caimans. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (4), 2010, pp. 1109-1126.

- ^ Peter Houde, Storrs L. Olson: Paleognathous Carinate Birds from the Early Tertiary of North America. Science 214, 1981, pp. 1236-1237.

- ↑ Sterling J. Nesbitt, Julia A. Clarke: The anatomy and taxonomy of the exquisitely preserved Green River Formation (early Eocene) lithornithids (Aves) and the relationships of Lithornithidae. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 406, 2016, pp. 1–91 doi: 10.5531 / sd.sp.25 .

- ↑ Gerald Mayr, Ilka Weidig: The Early Eocene bird Gallinuloides wyomingensis - a stem group representative of Galliformes. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (2), 2004, pp. 211-217.

- ^ A b c d Ilka Weidig: New Birds from the Lower Eocene Green River Formation, North America. Records of the Australian Museum 62, 2010, pp. 29-44.

- ↑ a b c d e Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 215-258.

- ↑ Gerald Mayr, Michael Daniels: A new short-legged landbird from the early Eocene of Wyoming and contemporaneous European sites. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46 (3), 2001, pp. 393-402.

- ↑ Sterling J. Nesbitt, Daniel T. Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke: Podargiform Affinities of the Enigmatic Fluvioviridavis platyrhamphus and the Early Diversification of Strisores (“Caprimulgiformes” + Apodiformes). PlosOne 6 (11), 2011, p. E26350 ( [2] ).

- ^ A b Daniel T. Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke, Sterling J. Nesbitt, Felicia B. Kulp, Lance Grande: Fossil evidence of wing shape in a stem relative of swifts and hummingbirds (Aves, Pan-Apodiformes). Proceedings of the Royal Society B 280, 2013 280, pp. 1471-2954.

- ↑ Storrs L. Olson: An early Eocene oilbird from the Green River formation of Wyoming (Caprimulfiformes: Steatornithidae). Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon 99, 1987, pp. 57-69.

- ↑ Storrs L. Olson: A Lower Eocene Frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, 35, 1987, pp. 1-33.

- ↑ Storrs L. Olson, Hiroshige Matsuoka: New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa, 1046, 2005, pp. 1-15.

- ^ Storrs L. Olson: A new family of primitive landbirds from the Lower Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming. Science series of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 36, 1992, pp. 127-136.

- ↑ Alan Feduccia: Neanis schucherti restudied: Another Eocene piciform bird. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 27, 1976, pp. 95-100.

- ^ Alan Feduccia, Larry D. Martin: The Eocene zygodactyl birds of North America (Aves: Piciformes). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 27, 1976, pp. 101-110.

- ^ Daniel T. Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke: Primobucco mcgrewi (Aves: Coracii) from the Eocene Green River Formation: New Anatomical Data from the Earliest Constrained Record of Stem Rollers. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (1), 2010, pp. 215-225.

- ↑ Ilka Weidig: The first New World occurrence of the Eocene bird (Aves:? Leptosomidae). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 80 (3), 2006, pp. 230-237.

- ↑ Daniel Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke: New fossil mousebird (Aves: Coliiformes) with feather preservation provides insight into the ecological diversity of an Eocene North American avifauna. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160, 2010, pp. 685-706.

- ↑ Peter Houde, Storrs L. Olson: A radiation of coly-like birds from the Eocene of North America (Aves: Sandcoleiformes new order). In: KE Campbell Jr. (Ed.): Papers in Avian Paleontology honoring Pierce Brodkorb. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series 36, 1992, pp. 137-160.

- ^ Daniel T. Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke, Lance Grande: Stem Parrots (Aves, Halcyornithidae) from the Green River Formation and a Combined Phylogeny of Pan-Psittaciformes. Journal of Paleontology 85 (5), 2011, pp. 835-852.

- ^ Daniel Ksepka, Julia A. Clarke: A New Stem Parrot from the Green River Formation and the Complex Evolution of the Grasping Foot in Pan-Psittaciformes. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32 (2), 2012, pp. 395-406.

- ↑ Gerald Mayr: A new raptor-like bird from the Lower Eocene of North America and Europe. Senckenbergiana lethaea 80 (1), 2000, pp. 59-65.

- ^ N. Adam Smith, Aj M. DeBee and Julia A. Clarke: Systematics and phylogeny of the Zygodactylidae (Aves, Neognathae) with description of a new species from the early Eocene of Wyoming, USA. PeerJ 6, 2018, p. E4950 doi: 10.7717 / peerj.4950 .

- ^ Daniel T. Ksepka, Lance Grande and Gerald Mayr: Oldest Finch-Beaked Birds Reveal Parallel Ecological Radiations in the Earliest Evolution of Passerines. Current Biology 29, 2019, pp. 1–7 doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2018.12.040 .

- ^ A b Kenneth D. Rose, Wighart von Koenigswald: An exceptionally complete skeleton of Palaeosinopa (Mammalia, Cimolesta, Pantolestidae) from the Green River Formation, and other postcranial elements of the Pantolestidae from the Eocene of Wyoming (USA). Palaeontographica A 273, 2005 (3-6), pp. 55-96.

- ↑ Kenneth D. Rose, Rachel H. Dunn, Lance Grande: A New Skeleton of Palaeosinopa didelphoides (Mammalia, Pantolesta) from the Early Eocene Fossil Butte Member, Green River Formation (Wyoming), and Skeletal Ontogeny in Pantolestidae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (4), 2014, pp. 932-940.

- ^ Wighart von Koenigswald, Kenneth D. Rose, Lance Grande, Robert D. Martin: First Apatemyid Skeleton from the Lower Eocene Fossil Butte Member, Wyoming (USA), Compared to the European Apatemyid from Messel, Germany. Palaeontographica A 272, 2005 (5-6), pp. 149-169.

- ^ Nancy B. Simmons, Kevin L. Seymour, Jörg Habersetzer, Gregg F. Gunnell: Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation. Nature 451, 2008, pp. 818-821.

- ↑ a b Lucila I. Amador, Nancy B. Simmons and Norberto P. Giannini: Aerodynamic reconstruction of the primitive fossil bat Onychonycteris finneyi (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Biology Letters 15, 2019, p. 20180857 doi: 10.1098 / rsbl.2018.0857 .

- ^ A b Glenn L. Jepsen: Early Eocene Bat from Wyoming. Science 154, 1966, pp. 1333-1339.

- ^ A b Nancy B. Simmons, Jonathan H. Geisler: Phylogenetic relationships of Icaronycteris, Archaeonycteris, Hassianycteris, and Palaeochiropteryx to extant bat lineages, with comments on the evolution of echolocation and foraging strategies in Microchiroptera. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 235, 1998, pp. 1-182.

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 259-278.

- ^ Anthony J. Martin, Gonzalo M. Vazquez-Prokopec, Michael Page: First Known Feeding Trace of the Eocene Bottom-Dwelling Fish Notogoneus osculus and its Paleontological Significance. PlosONE 5 (4), 2010, p. E10420 ( [3] ).

- ↑ Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 345–354.

- ^ A b W. C. Clyde, ND Sheldon, PL Koch, Gregg F. Gunnell, William S. Bartels: Linking the Wasatchian / Bridgerian boundary to the Cenozoic Global Climate Optimum: new magnetostratigraphic and isotopic results from South Pass, Wyoming. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 167, 2001, pp. 175-199.

- ^ Gregg F. Gunnell, Paul C. Murphy, Richard K. Stucky, KE Beth Townsend, Peter Robinson, John-Paul Zonneveld, William S. Bartels: Biostratigraphy and biochronology of the latest Wasatchian, Bridgerian and Uintan North American Land Mammals “Ages ". In: LR Albright III (Ed.): Papers on Geology, Vertebrate Paleontology, and Biostratigraphy in Honor of Michael O. Woodburne. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 65, 2009, pp. 279-330.

- ^ A b c M. Elliot Smith, KR Chamberlain, BS Singer, AR Carroll: Eocene clocks agree: Coeval 40Ar / 39Ar, U-Pb, and astronomical ages from the Green River Formation. Geology 38, 2010, pp. 527-530.

- ^ A b c Lance Grande: Studies of paleoenvironments and historical biogeography in the Fossil Butte and Laney Members of the Green River Formation. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30 (1), 1994, pp. 15-32.

- ^ Mark A. Loewen and Paul Buchheim: Paleontology and paleoecology of the culminating phase of Eocene Fossil Lake, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming. in: VL Santuchi and L. McClelland (Eds.): National Park Service Paleontological Research. Technical Report NPS / NRGRD / GRDTR-01, 1998, pp. 73-80.

- ↑ George E. Mustoe, Mike Viney and Jim Mills: Mineralogy of Eocene Fossil Wood from the “Blue Forest” Locality, Southwestern Wyoming, United States. Geosciences 9, 2019, p. 35 doi: 10.3390 / geosciences9010035 .

- ^ S. Bruce Archibald, Kirk R. Johnson, Rolf W. Mathewes, David R. Greenwood: Intercontinental dispersal of giant thermophilic ants across the Arctic during early Eocene hyperthermals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278, 2011, pp. 3679-3686 doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2011.0729 .

- ^ Robert M. West: Geology and vertebrate paleontology of the Northeastern Green River Basin, Wyoming. Twenty-first Annual Field Conference, Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, 1969, pp. 77-92.

- ^ Robert M. West: Geology and mammalian paleontology of the New Fork-Big Sandy area, Sublette County, Wyoming. Fieldiana 29, 1973, pp. 1-193.

- ↑ Jack L. Conrad, Jason J. Head and Matthew T. Carrano: Unusual Soft-Tissue Preservation of a Crocodile Lizard (Squamata, Shinisauria) From the Green River Formation (Eocene) and Shinisaur Relationships. The Anatomical Record 297, 2014, pp. 545-559.

- ^ Mounir T. Moussa: Fossil Tracks from the Green River Formation (Eocene) near Soldier Summit, Utah. Journal of Paleontology 42 (6), 1968, pp. 1433-1438.

- ^ Paul A. Selden, Yinan Wang: Fossil spiders (Araneae) from the Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado. Arthropoda Selecta 23 (2), 2014, pp. 207-219.

- ↑ Dmitry E. Shcherbakov: The earliest find of Tropiduchidae (Homoptera: Auchenorrhyncha), representing a new tribe, from the Eocene of Green River, USA, with notes on the fossil record of higher Fulgoroidea. Russian Entomological Journal 15 (3), 2006, pp. 315-322.

- ↑ Torsten Wappler, Eric Guilbert, Conrad C. Labandeira, Thomas Hörnschemeyer, Sonja Wedmann: Morphological and Behavioral Convergence in Extinct and Extant Bugs: The Systematics and Biology of a New Unusual Fossil Lace Bug from the Eocene. PLoS ONE 10 (8), 2015, p. E0133330 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0133330 .

- ↑ Michael S. Engel: A New Snakefly from the Eocene Green River Formation (Raphidioptera: Raphidiidae). Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 114 (2), 2011, pp. 77-87.

- Jump up ↑ J. Ray Fisher, Erika M. Tucker and Michael J. Sharkey: Colemanus keeleyorum (Braconidae, Ichneutinae sl): a new genus and species of Eocene wasp from the Green River Formation of western North America. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 44, 2015, pp. 57-67 doi: 10.3897 / JHR.44.4727 .

- ^ Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden: Geological Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers in 1859-1860. Washington, 1869, pp. 1-173 (p. 5) ( [4] ).

- ^ Paul Orman McGrew, M. Casilliano: The geological history of Fossil Butte National Monument and Fossil Basin. National Park Service Occasional Paper 3, National Park Service, Washington, DC, USA, 1975 ( [5] ).

- ^ Albert Charles Peale: Report on the geology of the Green River district. In: Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (Ed.): 11th Annual Reptort of the US Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Washington, 1879, pp. 509-646 (pp. 534-536) ( [6] ).

- ↑ a b c Lance Grande, 2013, pp. 17–41.

Web links

Coordinates: 41 ° 45 ′ 0 ″ N , 110 ° 45 ′ 0 ″ W.