madness

As madness were up about certain at the end of the 19th century behavior - or thought patterns called, are not the accepted social norm corresponded. A goal compliant with this standard was always assumed. Most of the time, social conventions determined what was understood by “madness”. B. like the word madness for mere deviations from the conventions (cf. Latin delirare from de lira ire , originally agricultural “deviating from the straight furrow, getting off track”). However, it could also be used for psychological disorders in which a person with a comparatively normal intellectual function suffered from pathological imaginations , right up to the marking of completely bizarre and (self-) destructive actions. Symptoms of the disease were also sometimes referred to as insanity (such as those of epilepsy or a traumatic brain injury ).

The term “madness” was historically used on the one hand in different contexts with different meanings and on the other hand it was applied retrospectively to different phenomena. It is therefore a phenomenon that is difficult to isolate from a medical and cultural history point of view, can hardly be defined and in some cases is contradictory. Which deviations from the norm were still accepted as "cranky" and which were already considered "crazy" could differ considerably depending on the region, time and social circumstances. Therefore, modern disease criteria and names usually cannot be applied to the historical manifestations of madness. The diagnosis of schizophrenia today would most likely correspond to madness.

Word history

The word "madness" is a regression of the 18th century from the adjective "insane", which can be traced back to the 15th century. The model was the word "crazy", which goes back to the Old High German wanwizzi . The Old High German wan ( ie. * (E) uə-no "empty") originally means "empty, inadequate" (cf. Latin vanus , English waning ). “Wahnwitz” or “Wahnsinn” meant something like “without meaning or understanding”. Because wan and delusion (ahd. Wân "hope, belief, expectation") coincide in the history of language , the meanings have mutually influenced one another: "delusion" became a false, imagined hope , the old word component wan is now used as the etymologically unrelated " Delusion "perceived.

The Old High German knows three nouns that describe distinctive states of clouding of the mind and madness: sinnelōsĭ , tobunga and nonsensicalī . The pathological uuotnissa may have to be placed alongside these terms , which translates as the Latin dementia . The meaning of "madness through obsession" has unuuizzi . All these terms have their origins in Latin ( dementia , alienatio and insipientia ) and are very difficult to differentiate from one another.

In Middle High German there are a number of other terms to denote madness (ige); first of all tôr and narre , but also a large word field with compounds of the stem syllable sin (n) , such as unsin , unsunheit , unsinne , unsinnec , unsinnecheit , unsinneclîchen and unsinn . Then there are the aforementioned compound words of the root syllable wan as wanwiz , wanwizze and wanwitzic and compounds the root syllable romp as tobesuht , raging site , romp , tobesühtig and tobic or töbic . In Hartmann von Aue are still found hirnsühte and hirnwüetecheit .

Synonymously used terms are "madness" and "insane" ( "astray-being"). Historically, the term was also used in the terminology of psychopathology until it was replaced by the term " mental illness " in the 19th century . However , it is no longer used as a disease term in the sciences today.

Today, the words "madness" and "insane" are used in common parlance, in addition to their old meaning, in a figurative sense, both in a positive and in a negative way, to denote extraordinary, extreme conditions.

Signs or "symptoms" of madness

Since the forms of the phenomenon "madness" are very diverse, the interpretations of what is to be regarded as a symptom of this condition can be very different. In any case, the insane behaviors and expressions move in certain ways outside of the norm. Those affected are thus - in the literal sense - “crazy” from the middle of their social environment .

Often madness manifests itself through a loss of control over the affects , so that feelings are shown and lived out uninhibited. The behavior moves outside of reason, the consequences of one's own actions for oneself and others are no longer considered. Actions can be objectively meaningless or purposeless or purely instinctual . In addition, individual cognitive skills may fail. The difference between inner and outer reality is sometimes no longer recognized. The perception of reality is disturbed. Examples of the resulting catastrophic consequences can already be found in ancient mythology : Hercules kills his children in a madness, Ajax slaughters Odysseus' flock of sheep and throws himself into his own sword, the Edonian king Lycurgus cuts his own legs, Medea stabs hers Sons and Melampus castrated themselves with fatal outcome.

The specific manifestations of madness that can be perceived by outsiders move in a broad field of tension between highly increased activity and catatonic stupor . In the first extreme, manic and agitated behavior can be decisive, in the other extreme, according to ICD-10 (F32.3), depressive or indifferent dawning. (As is often characteristic of the disturbed communication ability of the person concerned, the degeneration of the spoken utterances applies echolalia : repetitive repeating phrases, Lautmalerei , reduplication , Kinderreime or -lieder ).

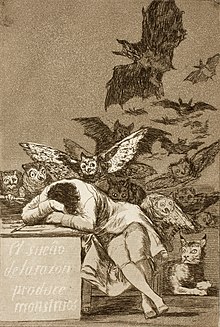

Pictorial representations

Representations of madness in art and literature can give an impression of which symptomatic manifestations were understood by "madness" in earlier times. Of course, these are sources that must be used with particular caution. It is true that an iconography of madness can only arise on the basis of a fund of already existing ideas of its manifestations. The concrete artistic representations then also have an effect on the expectations of the audience, that is, a mutual dependency of stereotypical models is to be expected. Both the aesthetic and the medical-diagnostic clinical picture are often projections that reflect reality in a distorted manner or even shape it.

In the pictorial representations, the madness manifests itself occasionally through distorted facial expressions , unnaturally twisted posture, contradicting or senseless gestures , through absurd actions, depiction of hallucinations or simply with the help of physiognomy .

The face is the preferred region of the body, which is used to identify the madness. First and foremost, inharmonious, asymmetrical or distorted facial features up to grimaces and wide open or twisted eyes indicate mental states beyond normality. Facial expressions that are inappropriate for the situation, such as laughing in a grief situation, are particularly strong indicators of existing madness.

The gestures of the madmen are often contradictory or indefinable. Theatrical contortions and reluctant directions of movement of different parts of the body are just as much a part of it as unusual relaxation or tension of the muscles. As extremes, completely cramped attitudes or sagging collapse are possible. When depicting women, there can be an erotic and indecent component.

For the reasons already mentioned, the medical illustrations must not be assessed less critically in terms of their source value than the artistic designs.

See also the section Examples from the Fine Arts below .

Literary descriptions

A haunting description of the madness can already be found in a section of the Iwein von Hartmann von Aue . The lion knight Iwein misses a deadline set by his wife and thus loses her favor. Thereupon he flees from the farm, becomes addicted and ekes out his life in the forest as an unclothed maniac:

dô wa sîn riuwe alsô grôz

daz im in daz hirne schôz

an anger ande a tobesuht,

he broke sîne site and sîne zuht

and tender abe sîn want, because

he was blôz sam a hand.

sus he ran across gevilde

naked to the wild.

(Loosely translated: His suffering became so great that madness and frenzy drove him crazy. He lost decency and education, tore his clothes off until he was completely naked. In this guise he ran across the fields into uninhabited areas. )

He is later cured by a magic ointment that the fairy Feimorgan herself made a long time ago, and he overcomes his identity crisis by assessing his previous life as a dream and henceforth believing himself to be a farmer . He is then clothed and taken to the Countess of Narison's castle, where he becomes completely healthy. The description of the etiopathogenesis as well as the symptoms and the healing of insanity was seen here early on .

In Georg Heym's story Der Irre the whole horror of complete, senseless madness is depicted. The patient, released from an asylum, begins an ominous procession through the surrounding area, where he also meets two children:

“He caught up with the children and tore the little girl out of the sand. It saw the contorted face overhead and cried out loudly. The boy screamed too and wanted to run away. Then he got hold of it with his other hand. He hit the two children's heads together. One, two, three, one, two, three, he counted, and at three the two little skulls always crashed together like pure thunderstorm. Now the blood was coming. That intoxicated him, made him a god. He had to sing. A chorale occurred to him. And he sang:

'A strong castle is our God / […] There are no equals on earth.'

He accentuated the individual bars loudly, and with each one he let the two little heads collide, like a musician putting his cymbals together. When the chorale ended, he dropped the two shattered skulls from his hands. He began to dance around the two corpses in ecstasy. He swung his arms like a big bird and the blood on it leaped around him like a fiery rain. "

One of the most impressive descriptions of madness is probably the grotesque Notes of a Madman by Nikolai Wassiljewitsch Gogol . The detailed representation of the constant denial of reality and flight into a dream world with simultaneous physical decline represents a very impressive and delightful artistic design of mania . It describes the first person 's story of the official Poprischtschin, who one day meets two talking dogs, who claim to be in correspondence with one another. Poprishchin is unhappily in love with his boss's daughter, who is beyond his reach, and gives in to his depression. Soon he was able to confiscate and read the dogs' letters, and later he learned from the newspaper that the Spanish throne was orphaned. He recognizes himself as the legitimate king of Spain. Raised in such a high position, he steps in front of his beloved Sophie and prophesies that they will find each other. Poprishchin is admitted to the insane asylum , but believes he is in Madrid, but the senior physician is the Spanish inquisitor.

See also the section Examples from the literature below .

to form

Innumerable forms of madness have been distinguished and a number of classification systems have been proposed throughout history. The historical differential diagnosis included, among other things, dementia , dementia praecox , amentia , insania, melancholia , amor , mania , furor , ebrietas , lykanthropia , ecstasy , phrenitis (hence "frenetically") , somnium, lethargy , delirium , coma , cataphora , noctambulismus , ignorantia , epilepsia , apoplexia , paralysis , hypochondriasis and somnambulism . In the following, only a few of the most important shapes are presented here.

"Useful madness"

In ancient times , poetic inspiration and seerism could represent "positive" forms of madness. In ancient Greek μανία, manía "the frenzy" is related to the very similar Greek μαντις, mantis , that is "the seer", "the prophet ". The ecstasy was also considered madness, especially the Dionysian frenzy .

Plato differentiates between four forms of productive madness: the mantic , mystical , poetic and erotic madness. "Divine madness" can lead to true knowledge and thus has a positive connotation.

Similar to the ancient view, there was also sanctioned madness in the Middle Ages. This was expressed in spiritual ecstasy, raptures or visions . In addition, saints could go into "good" madness.

Unreasonable

In the modern era defining characterization of madness takes Immanuel Kant in his Anthropology in pragmatic ways before (1798). This groundbreaking division is based on the dichotomy of reason and unreason . Those whom he categorizes as “crazy” are assigned the disease forms “madness”, “madness” and “absurdity”. His assessment of madness as a “methodical shift”, which is characterized by “self-made ideas of a falsely poetic imagination”, became the classic definition of madness in the 18th and 19th centuries. For Kant, on the other hand, “madness” is a systematic , albeit only partial, disorder of reason, which expresses itself as “positive unreason”, since those affected use different rules of reason than the healthy. What all forms of madness have in common is the loss of common sense ( sensus communis ) , which is replaced by a logical obstinacy (sensus privatus) .

"Just normal madness"

The term mishegas comes from Yiddish and describes the (mild) madness that is found in every normal person. A meshuganer, on the other hand, is someone you think is really crazy.

melancholy

Another form of "madness" was already described in antiquity, but has gained popularity as a " fashionable disease " , especially among the educated since Renaissance humanism : the disease of melancholy . In the Middle Ages , the constitutional type of the melancholic was considered to be the least desirable, since it was predisposed to be poor in physique, unattractive appearance and unpleasant personal and mental traits. But in melancholy as a disease a possibility of self-genialization, already hinted at by Aristotle and Cicero, was hidden, which in humanism was now cultivated in a "cult of melancholy". Torquato Tasso , who began to suffer from delusions after the conclusion of his monumental epic La Gerusalemme Liberata , is an eloquent example. Even Schelling resorted to the old doctrine that only people who are a little insane, could be creative (nullum magnum ingenium sine dementia quadam) . This form of self-styling gradually became unpopular in the later 19th century.

Mania and hysteria

In contrast to melancholy, there was always mania (frenzy). This was defined as delirium sine febre cum furore et audacia . In contrast to melancholy, the greater wildness, excitement and heat of mania are emphasized here. Joannes Fernelius wrote:

"[The mania ...] is similar in thoughts, words and works to the madness of the melancholy, but torments and drives the sick around with irascibility, argument, shouting, horrible looks, with far greater physical impetus and mental confusion."

Originally reserved for women, hysteria (pnix hysterike) was believed to be caused by female reproductive predispositions . For example, a change in the position of the uterus in the woman's body should be able to induce feelings of suffocation, which were counted among the causes of this type of madness. In the second half of the 19th century, women were often mutilated by doctors for this reason (see below).

Other forms

Sometimes non-mental illnesses and defects were also counted as madness, such as epilepsy or rabies ( rabies ) , even fictional phenomena such as lycanthropy or dance madness (which, however, has its real counterpart in St. Substance-induced disturbances of consciousness such as intoxication and intoxication ( alcohol consumption , hallucinogens , plant toxins) could also be subsumed under madness.

Special forms are the permanent states that go back to purely organic causes, such as "innate stupidity" (amentia congenita) or massive intellectual disability (dullness and stubbornness: coma, lethargy, katoché, dementia ).

The love disease ( amor hereos , morbus amatoris ) is an insanity, which is established at unfulfilled or unrequited love. An example of the anonymous Mare leads The buzzard in front of the 14th century, the son of a king loses his bride and in pathological heartache into increases. His despair grows with crying and tearing hair. Then madness falls over him and the king's son becomes an animal. Until the happy ending he vegetates as a forest person.

In that medically and scientifically determined way of thinking, which from the beginning of the Enlightenment to the middle of the 20th century, had a significant impact on the history of Europe, health was the measure of the concept of normality for broad sections of the population and vice versa. As a result, everything that was not “normal” was easily regarded as “pathological” in bourgeois society. This could include anything that did not correspond to the cultural, social, moral or legal ideas of the time of acceptable behavior or forms of existence (e.g. homosexuality ). Those who did not conform or were marginalized should be "healed" and "reintegrated" as far as possible. A stereotypical ideal of a "healthy", i. H. an idea of what should be considered “healthy” and “normal” has always been present underground for reasons of the necessary distinction. At the same time, however, this ideal could also be deliberately misused for targeted exclusion (as happened in later times, e.g. through the psychiatricization of dissidents in the Soviet Union ).

Cause attributions

The first to deal with the complex of the concept of madness was Plato. In his Phaedrus dialogue he distinguishes between two main forms: that madness that is caused by human disease and that that is caused by divine gift. Then a distinction is made between natural and supernatural attempts to explain the madness.

Supernatural explanatory models

Magical pagan ideas

The Babylonians (about 19th to 6th centuries BC) and Sumerians (about 2800 to 2400 BC) considered madness to be caused by possession , sorcery , demonic malice, the evil eye, or by breaking a taboo . It was a judgment and a punishment at the same time.

In ancient Greece , too , the popular view was mostly based on an “possession by evil spirits ”. There was also the idea that madness was sent by a divine power. While the somatic disease “madness” for the soul , as Plato explains in the Timaeus , is evil, according to this concept, divine madness led to true knowledge and was therefore positively connoted. In the ancient myths , however, it almost always led to self-destruction and the killing of innocent people - mostly family members - when the gods sent mad. As a rule, madness was considered to be self-inflicted by hubris , pride or ambition.

In the Middle Ages , "ordinary" madness in most people's minds was caused by the devil or brought about by witches . In particular, uncontrolled action and language speaking ( glossolalia ) were viewed as devilish (Latin maleficum ).

Christian-religious ideas

Already in the Old Testament , madness is a punishment that can be traced back to divine intervention. So it says in Dtn 28,28: “The Lord strikes you with madness, blindness and insanity” . Such a punishment hits the figure of Nebuchadnezzar from the account in Dan 4,1–34 . Nebuchadnezzar is an arrogant tyrant who persecutes the Jews . A heavenly voice announces the deepest humiliation to him. He goes mad and has to live like an animal and eat grass for seven years. This figure of Nebuchadnezzar is the model for the medieval view of the causes of madness. Since he was humiliated because of the arch-sin of pride , there were close links between sin and madness: Hugo von St. Viktor , for example, emphasized the educational aspect of Nebuchadnezzar's madness. As a result, in the Middle Ages, madness was often attributed to the action of God .

Madness is usually interpreted as obsession. The most obvious case in the Old Testament is found with King Saul ( 1 Sam 9 : 2–31, 13). Saul draws the wrath of God for not completely exterminating the Amalekites , and is possessed by an evil spirit that torments him with madness and frenzy: “The following day an evil spirit of God came over Saul again, so that he was in his house got into a frenzy ” (1 Sam 18:10). This story was used over and over again in the Middle Ages to support the theory of demon and devil possession , especially during the Inquisition . It was not until the middle of the 17th century that Dutch Calvinists began to interpret this passage from the Bible in the sense of describing a mental illness.

There are also cases of madness in the New Testament . The most prominent example is the healing of the possessed of Gerasa by Jesus ( Mt 8.28-34; Mk 5.1-20, Lk 8.26-40). Matthew says:

“You couldn't tame him, not even with chains. He had often been handcuffed and tied up, but he had broken the chains and tore the fetters; no one could conquer him. Day and night he screamed incessantly in the burial caves and on the mountains and hit himself with stones. "

But the apostles were also able to heal madness (for example in Acts 5:16 ).

In the Inquisition, the concept of insanity was condensed as a form of possession by demons, devils and evil spirits.

The idea of the struggle for the soul also gained importance in the late Middle Ages and early modern times (see also Prudentius , Psychomachia ). This included that the forces of God and the devil fought for the soul of man. Mental confusion has been suggested as a possible consequence .

Natural explanatory models

Spiritual and moral defects

In the Homeric epic the Greek μαινεσθαι (mainesthai) meant “to rush ”, “to romp” or “to be out of your mind”. This behavior outside of the norms was usually due to the loss of affect control . The ancient Greeks understood “ordinary” madness to be the impairment or elimination of the sober mind, for example through pain , anger , hatred or the desire for revenge . In the Attic tragedy , too , which deals with existential and elementary conflicts, madness was seen as a loss of the self , which could have catastrophic consequences for those affected and the community.

After the end of the Middle Ages, which was mainly based on the explanatory model of possession, Johann Weyer (1515–1588) published the pamphlet De praestigiis daemonum against the witch's hammer and the Inquisition in 1563 . He saw madness as a disease of the mind and opposed religious errors with a rational medical paradigm. However, he remained a lone fighter who was unable to assert himself against superstition and clergy . Nevertheless, he was able to rely on Theophrast von Hohenheim ( Paracelsus ) (1493–1541) and Felix Platter (1536–1614) who, like him, were pioneers of medical psychiatry . Platter claimed that not all forms of insanity are automatically caused by demons. In the “common people” in particular, they often find “simple lunatics”; not every mentally disturbed person is automatically cursed .

Since the 13th century - according to Michel Foucault - the understanding of madness gradually began to change. He gradually joined the list of vices that heralded the immorality and irrationality of the person concerned. In the 15th century, madness was no longer necessarily in a demonic context. Instead, the individual “human weakness” of those affected was often brought to the fore: folly and folly are the responsibility of the individual who is unable to curb his discipline and excess. The wrong behavior results in madness. This is considered to be the weakness and defectiveness of its wearer and subsequently becomes a stigma . Accordingly, the fool , as someone who moves at the limits or outside the norms, is exposed to ridicule.

The “Age of Enlightenment ” developed the meaning of madness as a malfunction of an originally well-designed reason. Madness is conceived as the defective mode of natural reasonableness. This enlightening elaboration of reason produces madness - as unreason - as a necessary counterpart in order to be able to constitute the concept of reason meaningfully at all. In this concept, the complementary pair of terms limit and condition each other. Michel Foucault considers this development to be responsible for the parallel beginning of the exclusion of insane and the insane from society . Arthur Schopenhauer points to the mutual dependency of reason and madness when he postulates that animals are incapable of madness.

Physical causes

The Greek medicine declared insane by an abundance of "black bile" (Greek. Μέλαινα χολή, Melaina cholé ). This humoral-pathological conception was already devoid of religious and magical ideas. This theory of "black bile" (lat. Bilis atra ) became popular again in humanism and the Renaissance . Their dark juices and sooty vapors - it was believed - settle down on the brain , which was already recognized as the seat of the mind, wore it down and made it brittle. The “yellow bile” (lat. Bilis pallida or bilis flava ), on the other hand, could cause heated frenzy according to Daniel Sennert and thus be the reason for the choleric madness. Just as for mania, the “yellow bile” was also considered the cause of epilepsy, which is more in the border area of the concept of madness, but historically it was often added to it.

Melancholy was classified as a disease of the heart , which, in contrast to the brain, was seen as the seat of mind and feeling . However, this location was not undisputed. Girolamo Mercuriale, for example, described melancholy as a disorder of the imaginatio in the front part of the brain. There was great agreement that phrenitis - an inflammation of the meninges - is a possible cause of madness, the cause of which in turn is "grim, bitter bile that irritates the fibers of the brain" (Joannes Fantonus, 1738). The spleen , which was considered to be the reservoir of the black bile juices produced by the liver , also played a special role . If the “black bile” were not properly attracted by the spleen and mixed with the blood, it would get into the brain and cause great damage there (Ioannes Marinellus, 1615).

Not unlike melancholy is the complex of love sickness, amor hereos or amatorius disease . The connection is obvious here, although madness as a physical illness caused by unfulfilled love as early as 600 BC in antiquity. Is described by the poet Sappho and also appears again in the Corpus Hippocraticum .

Links were drawn early on between injuries to the brain and insanity. Wilhelm von Conches (around 1080–1154) already described the causes of the madness through injuries to the brain: the person affected loses one ability, but keeps the other areas of the brain that are undamaged. Also Mondino di Liuzzi (ca. 1275-1326) created a Ventrikellehre the pathology : "failure of mental power are with lesions of the relevant parts of the brain equated" ( ref . Kutzer, p 68f).

The positivistic psychiatry made the claim that all phenomena of madness not only have to be traced back to a comprehensible-causal, physical cause, but also have to be remedied. The spirit, the soul, was now seen as a mere puppet of the brain organ. This scientifically and anatomically based psychiatry finally established itself in the second half of the 19th century. The psychiatric paradigm was that diseases of the mind are diseases of the brain. As a result, the term “madness” as a nosological specialist term was obsolete and replaced by the term “mental illness”.

At the end of the 19th century the connection between madness and sexuality became the focus of interest. Based on the opposing pair of nature and culture , gender now played an important role. Wilde, members of the lower class and women belonged to the realm of the instinctual , men to bourgeois civilization . Because of the “ pathogenicity of the female abdomen” and the “inferiority of female nerves”, women were considered particularly vulnerable : puberty , menstruation , childbirth and menopause were considered dangerous. The localization of the "focus of the disease" led to the specific term of hysteria (from Greek ὑστέρα, hystera " womb "). During this time, women were granted mental health only as a brief interruption to their gender-related illness.

Modern psychiatry and neurology research the neurobiological basis of mental disorders. For example, changes in the metabolism of nerve cells in the brain can be detected in schizophrenia . On the basis of these findings, psychiatry endeavors to develop new therapies for mental disorders.

Mental disorders

After the term "madness" was replaced in the 19th century by the term mental illness, which was derived from the idea that a spirit or a soul resides in a person and that this could be sick (see psychoanalysis ), the term changed in 20th century again.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of insanity based on empirical observation began in 1793, when the physician and philanthropist Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) became head of the Parisian institutions for the sick, insane and reformatory, first in Bicêtre , then in Salpêtrière . He introduced more humane treatment methods and classified the inmates according to their individual problems. Whenever possible, he referred them to other institutions wherever possible. He accommodated the madmen who stayed behind in their own separate areas, depending on their symptoms. The madness that was thus "isolated", as it were, could now be examined in its peculiarities using empirical scientific methods. The externally visible signs of illness, which Pinel meticulously observed and linked to the patient's individual biography , became decisive for the future classification of insanity through his monograph Nosographie philosophique ou méthode de l'analyse appliquée à la médecine (Paris 1798) .

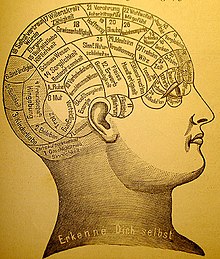

For the doctor Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828), insanity was one of the diseases that basically had material causes. In his Viennese practice after 1785 he began to study the anatomy of the brain and basic neurological issues between organ structure and function. He came to the conclusion that the brain consists of many individual units, the individual failure of which could lead to specific forms of madness. With this he founded phrenology (Greek phren " diaphragm ", as the seat of the soul in ancient Greece), whose connection with craniology (Greek cranion "skull") promised the determination of intelligence , character and shape by simply measuring the shape of the skull to enable the moral constitution of a person.

Today, mental disorders and illnesses are no longer summarized under a general term such as “madness”, but finely differentiated using various diagnostic systems, such as the DSM 4 of the American Psychiatric Association or the ICD-10 of the WHO ; The list of mental disorders provides a good overview of the wide diagnostic spectrum of these disorders .

Therapies

Magical Therapy

A cure for insanity has often been attempted through magical means , with the risk of 'driving out the devil through the Beelzebub (i.e. another devil)'. From a Christian point of view, obsession with evil spirits was properly countered when the Holy Spirit enters the sick person with an exorcism or at least drives away the demon. Spiritual healing methods were always available to Catholic believers . In addition, they could also undertake pilgrimages to special pilgrimage sites or have masses read. In later times, the Protestant churches preferred prayer , spiritual counseling and reading the Bible .

Surgical therapy

Drilling ( trepanations ) in stone age skulls could be interpreted as the first historically tangible evidence of a confrontation with what was later called madness. Paleopathologists suggest that these may have been attempts at surgical treatment of the mentally ill, in which "evil spirits" were to be given a way to escape from the patient's skull. Similar treatment methods are also known from later times (see fig.).

The dark side of psychiatric medicine became apparent in the highly dubious attempts at surgical therapy of the 19th and 20th centuries, such as hysterectomy , clitoridectomy and lobotomy . Against mid-20th century still without anesthesia used electroconvulsive therapy has left the public frightening notions of tormenting "electroshock" for the treatment of the mentally ill.

Custody and discipline

In the age of absolutism and mercantilism , the madman was removed from the public consciousness along with other marginalized groups who did not comply with the applicable norms of behavior or did not obey the rules and were sent to internment centers (England: workhouses , France: hôpitaux généraux , Germany: “ Zucht -, work - and madhouses ") included and thus made" harmless ". Their “unreasonableness” should be counteracted through discipline and work (often also through corporal punishment ). In some asylums, the chained sick could be seen as "monstrosities" to deter and satisfy the curiosity against entry through barred windows.

At the end of the 18th century, the Enlightenment freed the “madmen” at least from their physical chains. In principle, those affected were recognized as sick people in need of healing , although the doctor was primarily charged with isolating the madman “for his own good” and therapeutically justifying any disciplinary technique, above all “moral treatment”.

No therapy

In the Middle Ages , madness was usually attributed to the action of God or the devil. A possibility of help for those affected, who were called “natural fools”, was not available during the entire epoch.

The care of the insane was very different in the Middle Ages. Attitudes towards illness and the treatment of the sick depended heavily on their respective social milieu . The higher the social or material status of their family, the greater the chance of those affected to be looked after and cared for and, if possible, to heal their condition. Mad people from rich families were more likely to be integrated, those from poor families were often expelled.

As long as they were not considered dangerous, those affected were often left to their own devices. Some were given a fool's dress to protect themselves and warn others. The families of the madmen were subject to care and recourse : “Over right doren unde over senseless man ne sal man ok not judge; sweme sie aver scaden, ire vormünde sal it gelden. ” ( Sachsenspiegel III 3). If those affected were a public danger, they were locked up in city towers or at home, sometimes in fool's boxes or fool's cages outside the city walls . Strangers were driven out of their own territories.

Psychotherapy and psychopharmacotherapy

Nowadays, mental disorders and illnesses that used to be considered insane are usually treated with a combination of medicinal measures ( psychotropic drugs ) and psychotherapeutic methods, with the respective proportion of these two forms of therapy differing depending on the psychiatric clinical picture and therapeutic approach. In Germany, behavior therapy is mainly funded by law. The electroconvulsive therapy had come under criticism in recent decades, but will continue in bipolar disorder images in its modern form (under anesthesia) from the psychiatry used and displays with very severe depression and at least temporary success that enable behavioral therapy in some cases only. Little is known, however, about the organic causes of mental illnesses that could be directly addressed by therapy.

Sometimes, in the opinion of almost all doctors, it is necessary to temporarily remove mentally ill patients from society by means of the Mentally Ill Act and to treat them as inpatients. Mentally ill offenders in particular are placed in preventive detention in order to protect society from them. The modern psychiatric clinics have little in common with the madhouses of the 19th century , but as a sociological term they still have negative connotations.

Madness in art and literature

In the history of the arts, the representation of madness has always been shaped by voyeurism . The subject made it possible to shape the subjective, symbolic, fantastic and irrational. Dreams, fears and, above all, the ugly were worthy of images and text.

Examples from the fine arts

In the fine arts , the subject of "madness" has not been depicted excessively. Popular subjects are madness as punishment or vengeance from God or the gods, the healing of the possessed by Jesus of Nazareth, the apostles or the saints (see above); from the 16th century also representations of madmen and portraits , since the 18th century also representations from insane asylums. Here are some well-known examples:

- Typifications can be found, for example, in the drawing Das Narrenhaus by Wilhelm von Kaulbach , the fiction of a realistic scene in the courtyard of an insane asylum, in which each person in the group represented represents their own type of mental illness . The moralizing portrayal reflects a Biedermeier pathognomics, which interprets the individual facial features as symptomatic attributes of madness. Depicted types include the conceited philosopher , general and king; the fool, the melancholic , the sexually dissolute and the lovesick woman, several religious madmen, etc.

- Famous interior views from asylums can be found in William Hogarth or Francisco de Goya . Hogarth's eighth picture in the series “ A Rake's Progress ” shows a scene from Bedlam in which the insane inmates are portrayed in a very clichéd manner - for example as an imaginary emperor or pope with the appropriate, albeit caricatured, attributes. The curious visitors reflect the voyeurism of society and the viewer. Particularly noticeable is the group in the lower left corner of the picture, which is modeled on a Pietà . Goya's “Casa de Locos” offers a realistic-looking scene, which, in addition to the usual stereotypes, also seems to indicate the neglect and the desolate dawning of those left alone in the darkness of the custodial institution.

- The first portraits of the mentally ill are attributed to Théodore Géricault , who took pictures of ten patients in the Salpêtrière between 1821 and 1824 for scientific purposes, although it is no longer known which forms of madness the pictures were supposed to represent. Since the disease should be reflected in the facial features, the lighting design particularly emphasizes the physiognomy . Géricault no longer focuses on the excessively distorted or grotesque , but rather his subtle representations leave open where the line between normality and madness lies.

- Depictions of fools are only partially and marginally part of the subject of madness. There are sometimes overlaps in the attributes , by which insane people can sometimes be recognized. These are often not only shown in torn or dirty clothes, but sometimes also - to achieve a special contrasting effect - similar to the fools with symbols of authority, such as crown and scepter , which can also be clearly identified as dummies . The motif of the “world as a fool's house” is another figuratively designed variant.

See also the Pictorials section in the Symptoms section.

Examples from the literature

In literature , madness is an important motif , also as a motif of the “world as madhouse”. The scheme of action of guilt and atonement is often shaped decisively with the help of madness. It enables the development of the pathological development, a plausible representation of unbridled passions and uninhibited appearances and the psychologically justified collapse of a figure . At the same time, the reaction of different people to the confrontation with madness can be shown. This motif can at the same time largely involve the reader or viewer in the action and still allow a certain inner distance to be maintained. In general, the most severe mental disorders - which allow little developmental opportunities - are rarely presented, but rather hallucinations , "hysteria", intoxication delirium or pathological boredom .

The attributions for the causes of the madness in the literary representations usually follow the respective historical views. From a conservative point of view, madness remained the punishment for misconduct until the 19th century , since the Enlightenment it has also been the consequence of unbridled passions , with early romanticism , artistic ingenuity that got out of hand as a possible cause. From the 19th century onwards, the first "realistic" studies of the clinical picture can be found in Émile Zola , August Strindberg and Gerhart Hauptmann . In the theater of the absurd, after all, madness is the constitution of the world itself, which seems to be devoid of any meaningful meaning (e.g. Jean Genet's The Balcony ). For the protagonists , this can also mean recognizing the nonsense of a meaning given to their existence.

From the countless works of literature, only a small selection can be named here. The already mentioned Iwein des Hartmann von Aue is one of the oldest representations of madness . William Shakespeare uses madness as a creative tool several times, the most impressive is the monomaniacal obsession in Macbeth . In Sebastian Brant's satirical ship of fools , people are infected, as it were, by the collective madness of society; Similarly, in Erasmus von Rotterdam's praise of folly, social conditions are castigated. Typical representatives of romanticism are, for example, ETA Hoffmann with the depiction of Medardus in the elixirs of the devil , Nathanael in the Sandman or René Cardillac in Fraulein von Scuderi , as well as Bonaventure with the problem of a malicious world constitution or an insane world creator in the night watch . The résumés of individual actors in a world that is perceived as absurd into madness can be found in Georg Büchner's Lenz , Dostojewski's Der Doppelganger and in some of Kafka's stories (depending on the interpretation, including The Judgment , A Country Doctor , The Metamorphosis ). The descriptions of the conditions in the nursing homes, such as at the beginning of Georg Heyms Der Irre, are more socially critical .

Madness fulfills the most important function as a literary motif, but as a characterization of the final state of a character after their mental breakdown due to unbearable psychological stress. In Miguel de Cervantes ' novel Don Quixote there is no possibility of a solution between reality and illusion for the hero, Shakespeare's King Lear is broken by his hopeless situation, Othello is blinded by his jealousy; Goethe's Torquato Tasso and Aschenbach in Thomas Mann's novella Death in Venice and the protagonist in Doctor Faustus grind up the problematic of the artist . Feelings of guilt drive Hauptmann's trainman Thiel into mental derangement, as does Gretchen in Faust ; But poverty and hunger can also drive people crazy (e.g. in John Steinbeck's The Fruits of Anger , for social problems see also Allen Ginsberg's Howl ).

See also the Literary Descriptions section in the Symptoms section.

References

- ↑ Neel Burton: The Sense of Madness. Understand mental disorders ; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2011. See also zeit.de: Interview

- ↑ Wahnsinn in Etymological Dictionary of the German Language , 23rd edition 1999, p. 871

- ↑ Jörg Mildenberger, Anton Trutmann's 'Pharmacopoeia', Part II: Dictionary, Würzburg 1997, V, p. 2229.

- ↑ Hartmann von Aue: IWEIN . vv. 3231-3238; Source: http://www.fh-augsburg.de/~harsch/germanica/Chronologie/12Jh/Hartmann/har_iwei.html#3201

- ↑ Georg Heym: The lunatic . Source: https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/heym/dieb/irre1.html

- ^ Panse, Fr. and HJ Schmidt: Pieter Bruegels Dulle Griet. Portrait of a mentally ill person. Bayer, Leverkusen 1967.

- ↑ On the conception of Plato cf. Phaedr. 244 a - 245 a, 265 a - 265 b, Tim. 86 b

- ^ Yiddish Glossary ; The Yiddish Handbook: 40 Words You Should Know ; Wendy Mogel : The Blessings of a Skinned Knee : Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children , New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Singapore: Scribner, 2001, ISBN 0-684-86297-2 , pp. 190-192 ( hardcover; limited online version in Google Book Search - USA )

- ↑ Kutzer, p. 92.

- ↑ spurensuche.de

- ↑ Mk 5.3 EU

- ↑ “One should also not judge right fools or madmen; but if they harm someone, their guardians should compensate for the damage . "

literature

Cultural history

- ED Baumann : The pseudo Hippocratic script 'PERI MANIES'. In: Janus. Volume 42, 1938, pp. 9-141.

- Henri Hubert Beek: Waanzin in de middeleeuwen. Nijerk-Haarlem 1969; Reprinted Hoofddorp 1974.

- Burkhart Brückner: Delirium and madness. Self-testimonies, history and theories from antiquity to 1900. Volume 1: From antiquity to the Enlightenment. Volume 2: The 19th Century - Germany . Guido Pressler Verlag , Hürtgenwald 2007, ISBN 978-3-87646-099-4 (new, very extensive work with a focus on autobiographical evidence and the history of psychoses).

- Roy Porter: Madness. A little cultural history. Dörlemann, Zürich 2005, ISBN 3-908777-06-2 (An easily readable cultural-historical foray, written by a recognized expert; sometimes a little superficial)

- Michel Foucault : Madness and Society. A story of madness in the age of reason. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973; 20th edition ibid 2013 ISBN 978-3-518-27639-6 . (The "classic", great depth of knowledge, but also subjectively suggestive and to be appreciated from a critical distance)

- Michael Kutzer: Anatomy of madness. Mental Illness in Early Modern Medical Thought and the Beginnings of Pathological Anatomy. Pressler, Hürtgenwald 1998, ISBN 3-87646-082-4 (scientific historical, source-oriented investigation of theories between around 1550 and 1750)

- Klaus Dörner: citizens and madmen. On the social history and sociology of science in psychiatry. 3. Edition. Europäische Verlags-Anstalt, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-434-46227-9 (solid representation of the conditions in the "bourgeois era", approx. 1700–1850)

- Robert Castel: The psychiatric order. The golden age of the insane. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1979 a. ö., ISBN 3-518-28051-1 (systematic, psychiatric and socially critical investigation of the structures between 1784 and 1838)

- Werner Leibbrand , Annemarie Wettley : The madness. History of Western Psychopathology. Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau and Munich 1961 (= Orbis Academicus , II, 12). (Comprehensive medical history overview, somewhat out of date)

- H. Hühn: Madness. In: Joachim Ritter, Karlfried founder (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Vol. 12, pp. 36-42. (The philosophical perspective; very dense, difficult)

- Rudolf Hiestand: sick king - sick farmer. In: Peter Wunderli (ed.): The sick person in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance . Droste, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-0805-7 , pp. 61-77.

literature

- Josef Mattes: The madness in Greek myth and in poetry up to the drama of the fifth century (= Library of Classical Classical Studies , NF, Series 2; Volume 36), Winter, Heidelberg 1970, ISBN 3-533-02116-5 / ISBN 3 -533-02117-3 (Dissertation University of Mainz, Philosophical Faculty 1968, 116 pages).

- Allen Thiher: Revels in madness. Insanity in medicine and literature. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI 1999, ISBN 0-472-11035-7 (Chronological Treatise on the Connection of Madness and Literature from the Ancient Greeks to the Present)

- Madness. In: Horst S. Daemmrich, Ingrid G. Daemmrich: Topics and motifs in literature. A manual. 2nd Edition. Francke, Tübingen u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-8252-8034-9 , ISBN 3-7720-1734-7 , pp. 333–336 (short but very illuminating account of the role of the madness motif in European literature)

- Dirk Matejovski: The motif of madness in medieval poetry. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-518-28813-X .

- Oliver Kohns: The madness of sense: madness and signs in Kant, ETA Hoffmann and Thomas Carlyle (= literacy and liminality ), volume 5. Transcript, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-738-7 (dissertation University of Frankfurt am Main 2006, 361 pages).

- Susanne Rohr, Lars Schmeink (ed.): Madness in art. Cultural imaginations from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Trier 2010, ISBN 978-3-86821-284-6 .

- Gerold Sedlmayr: The discourse of madness in Britain, 1790–1815: medicine, politics, literature (= Studies on English Romanticism, NF, Volume 10), Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Trier 2011, ISBN 978-3-86821-311-9 .

- Anke Bennholdt-Thomsen, Alfredo Guzzoni: Aspects of empirical psychology in the 18th century and their literary response. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8260-5010-7 .

- Nicola Gess: Primitive thinking: savages, children and madmen in literary modernism: (Müller, Musil, Benn, Benjamin). Fink, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-7705-5469-0 .

- Bozena Anna Badura : normalized madness? Aspects of Madness in the Early Nineteenth Century Novel. Psychosozial-Verlag, Giessen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8379-2440-4 (Dissertation University of Mannheim 2013, 259 pages).

Visual arts

- Fritz Laupichler: Madness. In: Helene E. Roberts (Ed.): The encyclopedia of comparative iconography. Themes depicted in works of art. Vol. 2. Dearborn, Chicago 1998, ISBN 1-57958-009-2 , pp. 537-544 (overview of the iconography of madness, with an extensive list of works of art)

- Franciscus Joseph Maria Schmidt, Axel Hinrich Murken: The representation of the mentally ill in the fine arts. Selected examples from European art with a special focus on the Netherlands. Murken-Altrogge, Herzogenrath 1991, ISBN 3-921801-58-3 (problem-oriented individual discussions of selected works of art with classification in historical contexts)

- Miriam Waldvogel: Wilhelm Kaulbach's Narrenhaus (around 1830). On the picture of madness in the Biedermeier period (= LMU publications / history and art studies , No. 18). Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2007 (full text)

- Birgit Zilch-Purucker: The representation of the mentally ill woman in the fine arts of the 19th century using the example of melancholy and hysteria. Murken-Altrogge, Herzogenrath 2001, ISBN 3-935791-01-1 ( Insightful investigation of the problem area madness and femininity)

Web links

- Mad history - On the change of madness (diploma thesis by Gertraud Egger)

- On the history of psychiatric treatment methods by Prof. H. J. Luderer

- Is the madman sick? - Historical development by Frank Wilde

- Materials on the history of psychiatry at Brown University , in the Internet Archive ( Memento from October 15, 2008 in the Internet Archive )