Inca

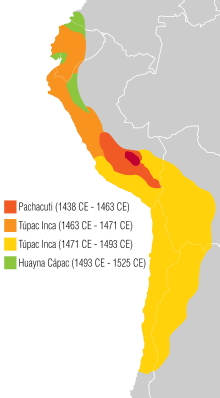

The Inka (plural Inka or Inkas ) is an indigenous urban culture in South America . Often only the ruling people of this culture are referred to as Inca . From the 13th to the 16th century they ruled over a vast empire of over 200 ethnic groups that was highly organized. At the time of greatest expansion around 1530, it covered an area of around 950,000 square kilometers, its influence extended from today's Ecuador to Chile and Argentina; an area whose north-south extension was greater than the distance from the North Cape to Sicily . In terms of developmental history, the Inca are comparable to the Bronze Age cultures of Eurasia. The ritual, administrative and cultural center was the capital Qusqu ( Cusco ) in the high mountains of today's Peru .

Originally, the term "Inca" meant the name of a tribe that, according to their own opinion, came from the sun god Inti and colonized the area around Cusco. His ruling clan later functioned as the nobility of the theocratic empire of the same name . The clergy and officers of the Inca army were recruited from here . Sapa Inka ("only Inca") was the title of the Inca ruler of the Tawantinsuyu ("land of four parts, empire of the four regions of the world" - that is the self-name of the empire).

overview

Despite an urban culture and the well-known stone monuments, the Inca culture was a predominantly peasant civilization, which was based on agricultural, cultural and rulership techniques, some of which had been developed for generations, in a millennia-old cultural landscape, and which only cost a very small, aristocratic ruling elite , urban lifestyle made possible.

The legitimacy of their power was based not least on the tributes and work done by the otherwise economically largely self-sufficient peasant communities to supply the population they ruled in the climatically, topographically and vegetatively radically different environmental zones, to bridge the gap in the event of frequent floods, drought and other disasters as well to redistribute for the supply of the armies during the frequent campaigns. Sign of lack - or even malnutrition during the Inca period were observed in a study in any examined corpse.

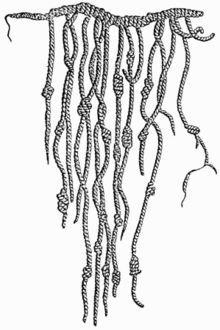

The Inca spoke Quechua ( runa simi = "language of the people"), used the knotted script Quipu (Khipu) and the Tocapu patterns, which were woven into textiles and which are not yet known as script. Since the Inca had no money, they also did not develop taxes in the European sense. Instead, they developed an official state that determined and coordinated all services and needs, all resources, tribute obligations and their distribution through extensive, exact, statistical records . The services intended for the state were therefore provided through strictly collective work: the population had to work a third of their working hours for Inti , the sun cult, and another third for the Inca, i.e. the ruling aristocracy and the military. The last third of her working time was used to support her family, the elderly, the sick, widows, orphans and those in need. The aristocracy , civil servants and the priesthood had privileges and were exempt from field and military service and from any state taxes. The nobility were allowed to wear gold jewelry. While peasants were obliged to enter into a monogamous marriage when they reached the age of twenty , male nobles were allowed to live in polygamy .

The Inca rulers and in particular their ancestors were worshiped as divine alongside the sun god Inti, the creator god Viracocha and the earth goddess Pachamama . While all other men were expressly forbidden to marry their sister, mother, cousin, aunt or niece, the Inca king married his sister when he took office, alluding to his mythical origins, who thus became Quya (Coya), queen. The Sapa Inka usually married the daughters of important princes of the subject areas in addition to his sister. His future successor was chosen by the Inca only from among the sons of the Coya, whereby he was advised by twenty relatives called councilors and the firstborn had no higher claim to the successor.

The Sapa Inca traveled through his empire in a sedan chair . You were only allowed to appear barefoot in front of him. Even the highest dignitaries had to approach the monarch with at least a symbolic burden as a sign of their humility. The Sapa Inka showed a demonstrative apathy at audiences by not addressing his interlocutors directly. He hid himself behind a wall or his face behind a precious material. As a sign of his royal dignity, he wore the maskaypacha or maskapaycha , a ribbon with the purple llawt'u (llautu), a long forehead tassel, on his head. He wore his artfully crafted robes only once. The clothes he wore, like his leftovers, were carefully collected and burned every year on the occasion of a large celebration.

Technology and medicine

The engineers, road and bridge builders did considerable work in view of the limited technological possibilities, which is illustrated by the 28-meter-long Q'iswachaka suspension bridge over the Río Apurímac , the 4,000-kilometer-long and 8-meter-wide coastal road and the 5200-kilometer and 6-meter-wide Andean road . Insurmountable rocks, such as those on steep walls above Pisac , were overcome through a tunnel. Chaski (relay runners) were out on the streets and could relay messages up to 150 miles in a day. The entire road network of the Inca had an approximate length of 40,000 kilometers and was thus larger than the Roman one. It was used within walking distance, as neither mounts nor bicycles and wagons were known. The architects erected prestigious buildings from heavy, cyclopean granite stones , which they fit together in an angular, seamless manner, and which survived the frequent earthquakes largely unscathed (but not the destruction by the Spaniards). Arched vaults were unknown to them.

The Incas have already performed successful operations on the skull and used the trepanation and scraping technique , which was also used by Stone Age peoples in Europe and Africa . Tools and weapons were made from copper and bronze . Iron was unknown. They mastered the art of weaving and made clothes from fine vicuña and alpaca wool . There were precise regulations about the design of the stand attire. The ceramic objects found have simple, colorful patterns and do not have the playfulness of earlier cultures. They played on the ocarina , a clay wind instrument, but also on quenas (qina) , the Andean flutes made of bamboo, the piruru made from jaguar or human bones or the pan or shepherd's flute Antara , made of reed or baked clay, and small belly drums at their celebrations and parties. Housing of conch (Strombus) , Pututu mentioned, which were considered daughters of the sea were used in ritual ceremonies like a trumpet, to the attention of the Apus , the mountain gods, to draw attention to the plight of people. Festivals and religious ceremonies were accompanied by music and dance - art, as in medieval Europe, was a ritual expression of religion, told of acts of war and heroism of kings and curacas - no l'art pour l'art .

The magnificent buildings, the wide road network and the accomplished handicrafts are particularly remarkable, as these cultural achievements could be accomplished predominantly with human muscle power, i.e. without wheel or wagon, without draft animals such as ox and horse, without pulley blocks , pottery wheels , bellows, pliers and without writing .

In order to supply a huge number of people for the conditions of the high mountains and to prevent famine, almost all suitable slopes in inhabited areas were terraced and watered with canals over the centuries . Experts (kamayuq) measured the average amount of water and its evaporation exactly in circular, exactly carved out of the rock, basin-shaped depressions of different depths. In addition to precise weather observation, this provided them with data about the wind and upcoming storms. Surplus from the tribute payments were stored in special storage tanks that protected from rain, in which the wind circulated and thus protected from rot. In some cases, potatoes have been "freeze-dried". 20 varieties of corn (sara) , 240 varieties of potato , beans , quinoa , amaranth , pumpkin , tomatoes , cassava , peppers , cocoa beans , avocados , papayas , peanuts , cashews and mulberry trees were grown on the high terraces . They kept llamas , ducks , alpacas and guinea pigs as pets and pack animals , the latter mainly for consumption (quechua: quwi , from Spanish cuy ).

story

The earliest written sources for the history of the Inca are the Spanish conquistadors , who tell of their observations upon arrival in Peru. Missionaries and chroniclers recorded the oral traditions of the Inca. The extensive works of two Peruvian chroniclers who wrote a few decades later are particularly important: Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616) and Waman Puma de Ayala (born around 1540, died around 1615). These records reflect the Inca self-image after they became the dominant tribe in the Andes through tactics and conquests. The suppression of the memory of the Andean predecessor cultures, which was already practiced in the Inca Empire, is traced in these chronicles. There is only imprecise information about the first eight Inca rulers up to Huiracocha Inca , and history is mixed with mythology. It was not until the beginning of the 15th century, with the reign of the Inca Pachacútec Yupanqui , who is considered the real architect of the great empire, that more reliable historiography began. The picture obtained from this must be supplemented and compared with the findings of archeology, which leads to tensions. While the older historiography followed the statements of the chroniclers relatively closely, there is now a tendency to question the stories of the chroniclers more critically and to weight their subjectively colored narratives more heavily. Using archaeological findings, the Finnish researcher Martti Pärssinen comes to the view that the previously assumed chronology of the Inca empire must be questioned and probably partially revised. It should always be taken into account that all of the knowledge that has been handed down from the Inca comes from the context of the world that was already shaped by the Spanish conquest and that there are no written sources that represent an authentic voice from the Inca culture before the Conquista.

origin

In Inca mythology, there are several legends about the origins of the Inca. The best known was passed down by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, a mestizo who moved to Spain , whose mother came from the Inca rulers and had access to pre-Hispanic traditions. According to him, the first Inca Manco Cápac , the son of the sun, and his sister Mama Ocllo were sent by the sun god Inti to make the world a better place. On the sunny island in Lake Titicaca , according to other myths in the cave Paritambo, they came into the world. The sun god gave them a golden staff. They should set up their abode where they succeeded in driving the staff into the earth with one blow. After a long hike, they found a place and founded the city of Qusqu (Cusco) there, which the Incas believed was the “navel of the world”.

The mythical Lake Titicaca, a deep blue or silvery glittering water surface of 8,000 square kilometers expansion with several islands, including the moon and the sun island on which the ritual stone Titiqaqa is that considered Quechua -speaking Incas, like the Aymara -speaking descendants of the people of Tiwanaku as holy.

Contrary to their myth of origin , the Inca may actually have come from the Amazon lowlands, which can be inferred from the cultivation of the potato and cassava plant originally cultivated in forest areas and from frequent depictions of the jaguar, which only occurs in the tropical lowlands. As a messenger of the sun , the condor was as sacred to the Inca as all previous cultures, but unlike them they never depicted it. Also the fact that they spoke their own idiom before their arrival in the Cusco basin, that of the Uru and Chipaya is said to have been related and whose characteristics some experts associate with the Peruvian Amazon region, speaks for this thesis.

Rise and Expansion

The Inca founded the city of Cusco around the year 1200, which was divided into two halves, Upper Cusco ( Hanan Qusqu or Hunan Qusqu) and Lower Cusco ( Urin Qusqu or Hurin Qusqu). The first five Inca rulers, who bore the title Sinchi (quechua, "warlord", actually "strong"), ruled from Lower Cusco, the subsequent rulers with the title Sapa Inka resided in Upper Cusco.

The Incas increased the importance of their own culture by deliberately destroying any evidence of the achievements of their predecessor cultures and degrading their enemies as hostile barbarians. At first they promoted Aymara as a lingua franca, until they later established Quechua as the general language. At the same time, it is known that the Incas made use of the experiences of earlier cultures, in particular the Wari culture , which perhaps served as a model for them because they had dominated a similarly large territory 700 years earlier.

When the Inca arrived in the Cusco area, various other tribes lived here, including the Gualla and Sauasera . The Gualla were attacked by the relatively small Inca people and all of them killed. The Sauasera then joined forces with another tribe and tried to defend themselves against the intruders. The Inca also defeated this tribal union and set about subjugating the other tribes. By occupying the irrigation systems of the Alcabiza and the tribute they imposed on the Culunchima , they brought the area between the two rivers Watanay and Tullumayu under their control.

As a cult object, Inti played a major role in the conquests. It was kept in a straw box and venerated as a sanctuary. The descendants of the first Inca Manco Cápac did not dare to open the box. Only the fourth Inca Mayta Cápac had the courage to do so. Legend has it that the sacred object Inti was able to speak and give advice for the conquests.

The second Inca Sinchi Roca , referred to as the Scout, began a peaceful expansion towards Lake Titicaca through the voluntary integration of the Puchina and Canchi villages , which others joined.

His successor Lloque Yupanqui as the third Inca set out to conquer Lake Titicaca with an army of six to seven thousand men. The Ayahuiri opposed this expansion with determined military resistance, which the Inca ultimately broke with reinforcements. To get from there against the Colla , an Aymara -speaking hill tribe near Lake Titicaca, to be able to go to war, he left as expedition base a fortress (Pucara) build and set up a force of ten thousand men under the command of his brother Manco Capac before moving to Callao relocated , today's port of Lima . At the head of an army he conquered the province of Hurin Pacassa as far as the slopes of the Sierra Nevada in the Central Cordillera.

After his marriage to Mama Caba he fathered three sons, whose eldest, Mayta Cápac , became the fourth Inca. In a protracted war against the Alcabiza, he divided the army into four parts, which he subordinated to four commanders, and forced his enemies to retreat to a hill. There the Inca besieged their opponents for fifty days and blocked their irrigation systems until the Alcabiza surrendered and were then treated well by the victors. Mayta Cápac survived further battles and finally married Mama Taoca Ray , with whom he fathered the two sons Cápac Yupanqui and Apo Tarco Huaman ( waman = "falcon").

The fifth Inca Cápac Yupanqui led campaigns against more distant peoples for the first time: to put down unrest in the land of the Colla, he set out with an army. The chiefs of the Cari and the Chipana , who were weakened by an ongoing feud against each other and feared nothing more than that their opponent might ally with Cápac Yupanqui, both vied for an alliance, which the Inca used to integrate both tribes into his sphere of influence. His wife Mama Curihilpay ( Qorihillpay or Chuqui Yllpay ) was a daughter of the chief of Anta, who was previously an enemy of the Inca . According to the chronicler Vaca de Castro, she was the daughter of the Curaca of the mighty Ayarmaca . From this point on, the Inca gained regional importance.

The sixth Inca Inca Roca married the daughter of the ruler of the Wallakan ( Guayllacan or Huallacan ). The seventh Inca Yáhuar Huácac emerged from this connection . The fact that one of his sons was taken hostage by a neighboring tribe for years during his youth relativizes the power of the Incas at that time. The relationship to the neighboring Ayarmaca, who until then had been on an equal footing with the Inca, changed at this time. The increasing dominance of the Inca led to conflicts. Finally, the Ayarmaca were won through the marriage of the daughter of the ruler Tocay Cápac (Tuqay Qhapaq) to Yahuar Huacac . With this connection there was also a military amalgamation.

Under the eighth Inca Huiracocha Inca , who extended his sphere of influence to Pisac (from P'isaq = " Tinamu ") in the Urubamba Valley ("plane of the spiders"), the actual expansion of the Inca Empire began. The Inca had good economic relations with the Quechua people , which were strengthened by the marriage between Huiracocha Inca and the chief's daughter. Their enemies, the Chanca , also represented a threat to the Inca and Cusco. Huiracocha's efforts to subdue this enemy were initially unsuccessful; only his son Cusi Yupanqui succeeded in mobilizing the two tribes Cana and Canchi as allies against the Chanca. Finally, Cusco was besieged by the Chanca (traditionally this event is dated to 1438), but despite their numerical superiority, they did not succeed in taking the city. Eventually they were spectacularly defeated by Cusi Yupanqui with the help of the allies he had won. Since then, the battlefield has been called Yawarpampa (Quechua: "blood plane") and served the cult of remembrance of this victory, which Cusi Yupanqui wanted to have achieved as a savior guided by the sun god, which was cultivated in the following epoch.

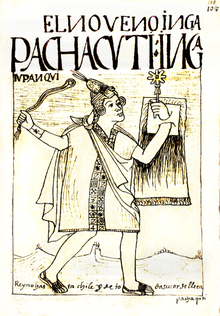

In the same year, Cusi Yupanqui became the ninth Sapa Inca, who took the name Pachacútec (Quechua: "reformer of the world", "changer of the world", "savior of the earth"). The military success against the Chanca had apparently made it possible for him to assert himself against his half-brother Urqu, who was actually intended as heir to the throne by Huiracocha Inca, who succeeded his father in his retirement home. Since this change of power, which was accompanied by a political, cultural and religious change, there have been more precise historical records.

High phase of the Inca

Pachacútec, who presumably took over the government while his father was still alive, in the first third of the 15th century, is considered to be the real creator of the Inca empire during its expansive heyday. After the suppression of rebellions at the beginning of his reign, he expanded the rule in the central Andes from Lake Titicaca to Junín , Arequipa and the coast. His organizational achievements and reforms, which made the effective administration of the ever larger area of rule possible in the first place, are valued as being on a par with his military successes. By assigning a part of the empire to each of the four cardinal points , he created the quartered Tawantinsuyu , the empire made up of “four regions belonging together” (Quechua: tawa “four”, tawantin “ fourness ”, suyu “land”; Hispanicized : Tahuantinsuyo ), whose axes are divided met in Cusco as an intersection; as a symbol for this the banner of the Incas was created. Within the districts called suyu , there existed smaller regional units ("provinces"), the boundaries of which were based on topographical features and which mostly had an urban center.

Under Pachacútec, Cusco developed into the ritual, political and cultural center of the empire. Compared to the older Viracocha worship, which his father represented, Pachacútec made the sun god he preferred to be the highest authority in the gods of the Inca state; As a national identification center, the Inticancha sun temple was designed in a glamorous way. In the vicinity of the capital, Pachacútec had agricultural terraces built for the cultivation of maize in order to ensure the supply of the population. Canals to the Saphi and Tullumayu Rivers , which ran through the entire city, supplied the residents with fresh water and kept them clean. By expanding and building new trunk roads, Pachacútec created one of the most important prerequisites for the expansion of the Inca Empire and knew how to secure the internal cohesion of the country through a uniformly organized administration, including the previous ruling structures based on local units. The standardization measures included the implementation of Quechua as the general lingua franca and business language in areas with other languages.

During his reign there were also repeated uprisings and setbacks. Despite his military success, Pachacútec had his brother Cápac Yupanqui, who, as a military leader in the pursuit of rebellious Chanca soldiers, advanced farther north than planned, possibly to eliminate him as a competitor. Another brother of the ruler undertook a campaign against hostile lowland peoples east of the Andes in the Montaña jungle with the intention of subjugating the Amazon , but got no further in the impenetrable jungle area surrounded by hostile peoples. The second campaign of conquest under Pachacútec's personal direction also failed because the ruler had to return to Cusco in a great hurry to put down a rebellion. As more recent finds show, however, the Inca Empire extended significantly further into the Amazonian lowlands and these parts of Amazonia probably came under Inca control earlier than previously assumed on the basis of historiographical records.

In 1471, Túpac Yupanqui was the tenth Sapa Inca to take over the rule of the empire from his father, with whom he had ruled for a while. Under his leadership the Inca empire achieved the greatest expansion. The most important step was the subjugation of the Chimú empire on the Pacific coast, the only great power rivaling the Inca empire for expansion. Presumably the Inca took over some organizational elements, e.g. B. the right-angled town planning, and various handicraft techniques of the Chimú. Further conquests served to incorporate the areas of today's Ecuador as far as Quito in the Inca state, as well as the expansion or consolidation of the area controlled by the Inca in the Amazonian lowlands and in today's northern and central Chile to the area of today's Santiago de Chile . After the conquest of Quito, the Inca is said to have rafted from Ecuador for more than a year to explore suspected island worlds further north.

The extreme southern limit of the Inca rule was previously suspected either on the Río Maipo (near Santiago de Chile) or on the Río Maule about 300 km further south. The advance of the Inca to the south apparently came to a standstill under Yupanqui's father in what is now central Chile, where a decisive battle handed down from the Inca Garcilaso and which ended unfavorably for the Inca is said to have taken place on the Maule River . It is usually dated to around 1485. However, there were verifiable trade and social contacts between Inca and Mapuche Indians far south of the Maule, at least as far as the Río Bío Bío . Here, too, according to the assumption of archaeologists, there could have been influences up to a hundred years before this time. According to chroniclers, the Inca only withdrew to the area north of the Atacama Desert in the decades shortly before the arrival of the Spaniards and gave up control of the valleys to the south. Overall, the Inca state almost doubled in size during the reign of Túpac Yupanquis, also as a result of the wars that were waged across the width between Santiago del Estero in what is now northwestern Argentina and the Río Maule.

Under Túpac Yupanquis rule the eastern slopes of the Andes were fortified. The Inca Duke Guacane, a descendant of the Inca Huayna Cápac, built on his orders the fortress Fuerte de Samaipata on the eastern slope of the Andes , where he housed some of his wives, whom he had eunuchs and soldiers protect. Nevertheless, under the leadership of their chief Grigotá, the Chiriguano managed to put the Inca to flight, kill the eunuchs, burn down the fortress and kidnap the concubines and sun virgins. The Inca retaliated by sending an army to retake Samaipata, rebuild the fortress and make it part of their line of defense on the eastern slopes of the Andes to protect against incursions by the lowland tribes.

High dignitaries of the inferior tribes initially retained important administrative functions. However, they had to send their sons to Cusco, where they received training and indoctrination in the style of the Inca and also served them as hostages. In this way, the Inca ensured inner peace, and repeated propaganda emphatically demonstrated all the advantages brought to the defeated. Túpac Yupanqui had the four imperial provinces divided into sub-provinces of 10,000 households (hunu) each , which were divided into groups of 5000, 1000, 500, 100 and 50 tributary households, which in turn were divided into units of ten (chunka) . The larger units were headed by officials from the Inca bureaucracy, while the smaller units were headed by the local nobility. This administrative structure, built on the perfection of the decimal system, tightened the central authority in the population, which is characterized by extreme ethnic, linguistic and cultural differentiation, with a complicated mosaic of political claims, and on the other hand also reduced the privileges of the long-established nobility. This gradually established a system of civil servants, which occasionally led to massive opposition from disgruntled "natural provincial lords".

As the first ruler after the mythical founder of the empire Manco Cápac, Túpac Yupanqui married his sister and fathered children with her. After his death (he may have been murdered) a bitter rivalry broke out between the two closest widows over the succession of their sons, which was fought with every possible means of court intrigue up to and including civil war. Finally, after eliminating his rival , Huayna Cápac succeeded him as the eleventh Sapa Inka in 1493. In the first years of his rule he was assisted in government affairs by an uncle. He moved his headquarters to Tomibamba (where today's Cuenca is located), where he is said to have fathered over 200 sons and daughters. Huayna Cápac waged unsuccessful campaigns against jungle Indians east of the Andes and moved the border in the north in difficult battles against the warlike Cara or Caragui tribes, who put up tenacious and sustained resistance, as far as the Ancasmayo River (its exact location in today's Ecuadorian - Colombian border area is not established). For this purpose, huge height fortresses with stone protective walls were built as a base of operations. With this the Tawantinsuyu had reached its maximum extent and the empire reached its administrative limits.

Signs of decline and civil war

In his final years, the ruler is said to have received the first reports of bearded, white men approaching the coast on board ships. Huayna Cápac's desired successor was his son Ninan Cuyochi, who had always lived by his father's side and accompanied him on his campaigns. But shortly before his father's death, the son and a quarter of a million people succumbed to a strange epidemic (possibly smallpox ) that had probably already been introduced indirectly by Europeans and had spread from Central America. When Huayna Cápac died shortly afterwards, probably from the same epidemic, a dispute between his sons Huáscar and Atahualpa broke out over the succession to the throne, which culminated in a long and bloody civil war. Whether Huayna Cápac had determined a succession to the throne and which one it was cannot be reliably reconstructed, as the situation was later presented differently by the supporters of the two competitors. According to one version, Huayna Cápac is said to have decided to divide the empire between the two: Atahualpa was to receive the northern region administered from Quito , Huáscar the southern part with Cusco as the seat of government. According to another version, Huáscar should be the successor and Atahualpa should administer the north as provincial lord.

Atahualpa, who was born in Tomibamba, was the result of his father's marriage to Tocto Koka, the last living princess of the Scyrs dynasty from Quito, Ecuador. Until then, he had always lived in the north with his father. Huáscar, who had spent his life in Cusco and whose mother Ruahua Occlo was a sister of Huayna Cápac and daughter of Túpac Yupanquis, saw himself as the only legitimate son of the Inca after the death of Ninan Cuyochi. Huáscar wanted to seize the opportunity, distributed abundant valuable gifts to the nobility, gave away beautiful acllas , had his potential political opponents killed, tortured or thrown into dungeons, appointed a new high priest (the incumbent Villac Umu knew the decrees of Huayna Cápac, near whom he had always been) and, following tradition, asked his mother for the hand of his sister Chuqui Huipa , since according to the custom of the Inca the enthronement was always connected with the marriage of the ruler to his sister. But his mother disliked his methods, which is why she rejected Huáscar's advertising. With the support of the priesthood, however, Huáscar succeeded in portraying courtship as a command from the gods, so that his mother could no longer refuse. Atahualpa, meanwhile, basked in the majority support of the generals. Unlike Huáscar, he had not appointed a noble Inca nobleman as general, but with Chalcuchímac and Quisquis and their field commanders Rumiñawi and Ukumari fanatical warriors from the north who, together with him, sought to rule over the whole of Tahuantinsuyu.

After a fierce battle, Huáscar's army was defeated by the battle-hardened troops from the northern territory in 1532. He was captured, many of his closest relatives were brutally murdered and their bodies were displayed on stakes in the streets. Atahualpa's generals persecuted the entire Inca aristocracy. The result was not only the almost complete annihilation of the royal ayllu, including wives and babies, but also of the priesthood, the highest officials, the Amautu (Inca scholars), and even the Quipucamayoc (knots). As a result, he was the absolute ruler of the entire Inca empire, but had irreparably damaged the absolute authority of the Inca.

Downfall

In April 1532 Francisco Pizarro landed on the Peruvian coast and marched deep into the interior of the Inca Empire under observation by Inca scouts. Pizarro found an empire that was involved in a fratricidal war between the brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar. The rapid expansion of the Inca and their forced regime with deportations had caused enormous discontent among the subjugated peoples, which contributed to the instability of the empire, and to the uprisings of the peoples, who now saw an opportunity for liberation, which Pizarro systematically used.

Pizarro intended to take Atahualpa hostage as part of his plans. When Pizarro's troop set out for the interior of the country in September 1532, according to his chronicler Francisco de Xerez, they consisted of 191 people, and there were an unknown number of other non-European companions. In Cajamarca an initiation ceremony for young nobles of the Incas was planned, which was to take place in the presence of Atahualpa and a larger entourage. There Atahualpa awaited the arrival of the Spaniards and hoped to present them to the people as his vassals. The soldiers of Pizarro were outnumbered by the Inca army, but found a suitable place for an ambush in Cajamarca, with an empty square surrounded by buildings and walls, and arranged to meet with Atahualpa. On November 15, 1532, he appeared with a larger ceremonial entourage and, among other things, bodyguards employed as musicians. Several tens of thousands of Inca soldiers from his army remained in the area as a parade and there was only one road access to the square. After the apparently friendly exchange of the previous day, Atahualpa did not expect an attack from the Spaniards, which, however, suddenly came out of the buildings shortly afterwards and panicked those present. Atahualpa was captured without resistance and, according to various sources, several thousand Incas were massacred in the enclosed space ( Battle of Cajamarca ). Atahualpa offered Pizarro to buy himself out for a room full of gold and silver. In the following months, temples and treasuries of the empire were looted for this purpose. In May the promised gold and silver were delivered, melted down and divided among Pizarro's men.

Atahualpa continued to rule during the imprisonment. He had his brother Huáscar killed to prevent him from reaching another agreement with the Spaniards. The leaders of the Inca army were not tasked with a liberation, but were distributed in the intervening time of captivity to various provinces of Chinchasuyu in order to maintain control and took action in Cuzco against the remaining supporters of Huáscar. Atahualpa was not released after the precious metals were handed over and was ultimately sentenced to death in a fictitious process. On July 26, 1533 he was executed by strangling . Túpac Huallpa , a younger brother of Huáscar, supported Pizarro in the trial with a false accusation against Atahualpa in order to bring about the takeover of power and the unification of the Inca Empire with his death. Túpac Huallpa was crowned the new Inca ruler, agreed to a vassalage to the Spanish king, and with Huallpa's support they set off for Cusco.

Some of the peoples earlier subjugated by the Inca sided with the conquerors in the hope of gaining independence. Atahualpas General Quisquis, who had occupied the capital, tried in vain to stop the Spaniards and their allies. Pizarro reached Cusco on November 15, 1533 and was greeted by many nobles as liberators. Túpac Huallpa died on the way to Cusco, Pizarro appointed Manco Cápac II , a half-brother of Atahualpas and Huáscars, to the Sapa Inka. Manco Cápac was initially closely allied with Pizarro, but soon realized that he was just a puppet of the Spaniards. In 1536 he organized a general uprising, besieged Cusco and attacked the newly founded capital Lima, which brought the Spanish into dire straits. Ultimately, however, the uprising failed and Manco and his supporters withdrew to Vilcabamba on the eastern slope of the Andes. From there he continued to resist the Spanish invaders through guerrilla actions until he was murdered in 1544 by seven Spaniards who had fled to him after internal Spanish conflicts. His sons Sayri Túpac and Titu Cusi Yupanqui were able to maintain the independence of Vilcabamba. Times of resistance and peaceful coexistence alternated until the Spanish viceroy declared war in 1572 after the assassination of a Spanish ambassador Vilcabamba. On July 24, 1572, the last Inca ruler, Túpac Amaru , was captured and beheaded two months later in Cusco.

State and administration

business

Mitma and Mit'a

The focus of the Andean way of life was the farm work of the Ayllu ("tribe, clan, clan, house community, family"), which was carried out in harmony with nature and in which the free landed, livestock and harvest were collectively owned by the free. The ayllu , not the family, was the basic unit of the social structure. In pre-Inca times it consisted exclusively of blood relatives. In the Inca times, the blood-related bond was weakened, inasmuch as the Ayllu all belonged to one territorial unit, one place of residence. The mutual support in field work, Ayni , survived the colonial days in rural areas. Weddings tended to take place within the ayllu . Parallel paternal and maternal lineages were formed, according to which men were descended from the paternal side and women from the maternal side.

A vertical economy was typical of Andean traditions long before the Inca. Every ecological-climatic vertical and horizontal zone of the Andes limits the inhabitants to the use of certain latitudinally stratified resources, such as certain arable crops, pastures, livestock, salts, metals and ores , firewood and construction wood, honey and fruit. The problem of uneven distribution of these resources, which in most parts of the world was solved through trade relations even in pre-industrial times, enables a class of traders to appropriate resources, to create capital and to unevenly distribute capital and resources. The Andean communities solved this problem through autonomous production on the different "floors". An Ayllu or an ethnic group maintained various production sites in the vertically arranged, ecological zones, depending on the season and agricultural and grazing cycles, from the Pacific coast to the cold mountain meadows of the Altiplano to the tropical forests on the eastern slope of the Andes, which were jointly managed and formed an " archipelago ". In this economic system, in addition to raw materials and food, there were also people who saw themselves obliged to mutual solidarity through family relationships. This complex archipelago economy was particularly pronounced in the Aymará kingdoms.

Production sites far away from the village were already managed in pre-Inca times by the mitmaqkuna ("resettlers") as a kind of village division of labor. Not to be confused with this is the general work obligation developed by the Inca with the increasing number of peoples to be integrated into their empire with'a , a compulsory service for the benefit of the sun god Inti and the Inca.

The integration of a señoríos went hand in hand with the redistribution of the agricultural area, which was updated at regular intervals: About a third of the area was used for the state and the Inca aristocrats and their bureaucracy, another third for the sun cult or the Clergy. The last third was available for collective subsistence . Individuals were not allowed to own land as personal property, so they were unable to make a profit from any surplus. Depending on marital status, individual age and the number and age of children, the number of Tupu , the fixed measure of the size of the agricultural area, varied . Seed, field work and harvest on the crown estates traditionally represented the tribute that had to be paid to the ruler in lieu of taxes. The Incas extended this system to the redistributed areas. At the same time, they increased the total area under cultivation through the terracing and irrigation. The Incas also increased efficiency by introducing herds of llama and alpaca to mountain regions in which they were previously not native, and by influencing the crops grown. With the surpluses generated in this way, supplies were collected in separate stores (qullqa) of the Inca and the temple. These supplies made it possible for large numbers of people to be used as Mitmaq in the construction of terraces, forts, temples, palaces, roads, bridges, irrigation canals and in mines. For the construction of terraces, canals and reservoirs, and even for the whole of Cusco and the Tahuantinsuyu, the architects created three-dimensional stone “blueprints” made of rock that are true to area and angles, several of which have survived in the Colca Cañon .

In addition, the Inca practiced an institution that exerted a very special fascination on the Spaniards: mitmay . The chronicler Pedro Cieza de León distinguished the political, economic and military mitimae. With the conquest of a province, garrisons of military mitmay were set up to secure the border . The warriors of the conquered peoples, such as the Chanca or the Cañari, were integrated into the professional Inca army. The defeated had to provide a contingent of soldiers for the new campaign. For political security, some of the subjugated people, such as 30,000 to 40,000 Chachapoyas , were forcibly resettled in a comparable climate zone in the interior of the Reich. (Later, of all people, the Chachapoya provided the royal guard.) Other tribes who were loyal to the Inca and who had the necessary knowledge to colonize this zone, such as: B. the inhabitants of the Cochabamba valley, were resettled in the conquered province on the periphery . The strategic goal of these deportations was to culturally and ethnically separate the peoples incorporated into the empire from their roots and to create a multi-ethnic settlement instead of a single population with a common language, tradition and identity in order to prevent uprisings. Settled Mitimae and the indigenous population observed each other with suspicion, thus reducing the risk of subversive political rebellion for the Inca. The different ethnic groups were obliged to keep their traditional clothing, hairstyle and way of life so that they could easily be identified as members of their tribe.

At the same time, along with the settlement and redistribution, the Inca changed the use of the agricultural land. In this way, the Mitimae also fulfilled an economic function that contributed to the formation of stocks. With the conquest of the Chimú kingdom in 1476, the Inca also adopted their methods of mass production of ceramics, textiles and metalworking in factories .

The Spaniards turned it into the Mita , in which male indigenous people who did not belong to an encomienda were forced to do labor services for payment, especially in mines.

Yanacona and Camayos

In addition to the “agricultural labor tax” and the Mitimae, the Inca developed another working relationship, the yanakuna (yanas) ( yana = “black”, also “complementary”), which have a special, hereditary status of the individual and their family to the state or a individual representatives included. In literature this status is sometimes treated as a state slave , sometimes as a serf or as a personal servant. He could be called a "personal follower". The Yanacona belonged to the household of certain Inca rulers, to whom they were indebted to personal loyalty throughout their lives. In return, they were generally exempt from agricultural labor tax and mitimae. Their work was varied: they could collect firewood, tending a flock of llama, weaving fabrics, harvesting coca leaves, doing handicrafts, as a porter in the army, as a guard of an Inca depot or as an official of a provincial governor in the Supervision of Mitimae colonists exist. One third of the agricultural land claimed by the Inca was occasionally farmed by the Yanaconas. Their loyalty to their Inca ruler exceeded that of the native ethnic group or the Ayllu. There are records, for example, by the chronicler Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa , according to which the Sapa Inca Túpac Yupanqui was the founder of the Yanacona institution, who wanted to punish with death a group of indigenous people who had rebelled against his rule. His wife is said to have advocated the conversion of the death penalty into life-long forced labor . Most of the Yanaconas were probably originally prisoners of war who served in the Inca palace or in the temples.

Another group that enjoyed a special civil status within the Inca culture were the Camayos . Like the Yanaconas , they worked in the imperial households in Cusco and the province, were exempt from agricultural labor tax, but did not gain the positions of trust and power of the Yanaconas . The Camayos were specialized craftsmen who were committed to their profession for life: they worked as stonemasons , carpenters, potters, dyers, weavers of high-quality textiles, silver and goldsmiths, honey collectors, herbalists, litter-bearers, gladiators , bodyguards, and specialized in feather- , Wood, bone and shell work, the mining of precious ores or work in salt mines. It was not uncommon for entire villages to specialize in a particular handicraft as handicraft camayos and, like the Mitimae, could be resettled or given as a gift to a provincial prince. The Inca state ensured their reproduction through food in exchange for their handicrafts or through fields which it made available to them. The status of the Camayo was hereditary; special achievements brought honor and prestige up to the appointment to the court in Cusco and were also richly rewarded materially. The status of the Camayos did not allow social advancement .

Jurisprudence

Sins and crimes were judged in Tawantinsuyu by judges (huchakamayuq) at their own discretion (the Inca knew no script). Pachacútec codified the laws in his realm. Inca jurisprudence made a distinction between crimes against the state and its institutions and crimes against individuals and the social order. The procedure consisted of testimony, interrogation, occasional torture or “ divine judgment ” and then a verdict without the possibility of objection.

The killing as one of the worst crimes was punished from a social point of view: the murder of a Kuraka was punished with quartering, the murder of an ordinary peasant only with whipping. Deliberate murder was also punished more severely than manslaughter out of jealousy or in an argument. The sustained injury to a person who was then no longer able to speak to himself was punished by the fact that the offender had to feed his victim. If this was not possible for him, his sentence became considerably more severe while the Inca took care of the victim.

The penalties imposed for adultery were drastic: not only the lovers, but also all their descendants up to the age of ten were imprisoned and knocked off rocks or stoned. A love affair with an Aclla not only led to a death sentence against the couple and their descendants, but also against all living beings in the village, yes against nature: even animals and plants were executed. Burglary, laziness, damaging bridges or killing seabirds were also punishable by death. With the height of the social class and in the event of recurrence, the severity of the punishments also increased.

Communal property had a higher value than private property, which was also reflected in the gradation of the penalties associated with its violation. They could consist of a warning, cutting off the hair, tearing the coat, whipping, or cutting off the nose, ears or hands. Drawing water from a public well, hunting on communal land without a permit, or damaging or setting bridges on fire was severely punished. The “judgment of God” mentioned above consisted of locking a suspect in a cell with wild animals. If he survived this two days, his innocence was proven.

The “Court of Twelve”, to which civil jurisdiction was subordinated, was subordinate to the Sapa Inka.

training

From the ideology peculiar to the Inca state, education already had a special meaning, as the Incas claimed to have brought culture to the “barbarians” of their environment. Inca Roca (around 1350 C.E.) is said to have conceived the foundation of a school in his “Speech from the Throne” . However, according to Garcilaso de la Vega, he was of the opinion: “It is not advisable for the children of the common people to learn the sciences that belong only to the nobles, lest they become arrogant and endanger the state. Let them learn the works of their fathers; that's enough for them. "

According to Baten and Juif, this segregating access to education is supported by a demonstrably low human capital at the beginning of the 16th century. The number alphabetism of the Peruvian indigenous people in the early 16th century was half that of the Spanish and Portuguese. This suggests that the Inca had a low human capital even before the Spanish colonization.

Education was only given to the young, male nobles in Cusco. There the schools were concentrated in a quarter in which the amawta , the scholars and the harawiq , the poets lived. This quarter was called yachaywasi ("house of knowledge, house of learning") and its importance for Tahuantinsuyu is compared to a university. The four most important subjects were the language Runa Simi or Quechua, the religion Intis, the Quipu knot script and the art of war. The study of language included poetry and music, religion included knowledge of astronomy and astrology, the Inca calendar, but also a not very well developed philosophy, writing the mathematics and the fundamentals of statistics, and finally the science of war also the historiography of the Inca and geography . The Inca calendar consisted of a 365-day solar year (wata) , which comprised twelve months of thirty days each. To compensate for the lunar and solar years, the twelve months were followed by five or six days off.

The Akllawasi , considered by the Spaniards to be monasteries, were open to the most beautiful girls in the empire . Here they received an intensive and methodical education in good behavior, housework, weaving and the sun religion from the Mamakuna .

In the introduction it was said that the Incas did not know any script. This may have to be put into perspective: The chronicler Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa already assured that Pachacútec had large, gold-framed canvases hung in the Coricancha on which the Inca history was recorded, which were later kept in the adjacent Puquincancha , the “Reichsarchiv” and caught fire along with the city during the storming of Cusco. It would also be very strange if a people who knew no script had words for script (qillqa) , writing and reading in their language . Last but not least, the astronomical knowledge that the Inca had, which goes back a long way and which can only be explained by means of complicated mathematics and geometry , cannot be explained with the help of Quipus and oral tradition alone . Thomas Barthel from the University of Tübingen reported in 1970 that, on the basis of years of research by the Peruvian archaeologist Victoria de la Jarra, he had succeeded in producing around 400 rectangular geometric images, called "Tocapu" , which recur on textiles and kero , as a species To identify pictorial writing that was closely related to the calendar system and astronomy, but was not used in the everyday life of the population. Tocapu , like astronomy and the calendar system, are cultural elements in the Andes that were probably developed well before the Inca and were only ruled by a small layer of scholars.

religion

The Inca myths were passed down orally until early Spanish colonists recorded them; however, some scholars claim that they were recorded on quipus, Andean knotted-line records. The Incas were polytheistic and believed in many gods. Important deities were Inti (sun god), Wiraqucha (creator god) and Pachamama (earth goddess). There were local deities, the Wak'a, in different parts of the empire . It was important for the Incas that they did not die by burning or that the body of the deceased was not cremated. The burning would make their life force disappear and threaten their transition to the hereafter. Those who obeyed the Inca moral code - ama suwa, ama llulla, ama quella (don't steal, don't lie, don't be lazy) - “went to live in the warmth of the sun while others spent their eternal days in the cold earth spent ".

In addition to animal sacrifices, the Incas also made human sacrifices. When Huayna Capac died in 1527, up to 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites and concubines were killed. The Incas made child sacrifices on important events such as the death of the Sapa Inka or during a famine. These sacrifices were known as qhapaq hucha .

Sun cult

In the Andes, every community, every tribe, had its own tradition, which derived its origin from a sacred place, a sacred star, or a sacred animal. Every place in the Andes has its mythological counterpart in a celestial star. All Andean peoples revered the sun and moon as a fertilizing couple.

In this transcendental context, the Incas claimed to be the sons of the sun. For their contemporaries, the military victories and the brilliant politics of the Inca rulers confirmed this unearthly origin. The Inca enforced the sun cult as the official cult of their empire: sun idols stood in all parts of the Inca empire next to a large number of worshiped (tribal) deities. The sun cult primarily served to legitimize the ruling elite. To use this cult, the Incas built temples all over their empire, which they dedicated to the sun. The best known and most important of them is the central sun temple in Cusco, the Coricancha or Qurikancha ("Golden Court", sun district). This main temple of the empire also served the cult of other deities, such as Mama Killa (the moon) and Illapa , the god of lightning and thunder, the cult of Venus and a series of stars, the weather gods and that of K'uychi , the rainbow, were put aside.

The Temple of the Sun in Cusco, truly the most holy sanctuary in the empire, did not survive the destruction during the Conquista . There are only a few descriptions and remnants of some walls that testify to the splendor of that work. They consisted of unevenly hewn natural stones that were perfectly seamlessly interlocked without cement. The circumference of the temple was more than 365 meters. Its main portal was on the north side. This, like the side entrances, was covered with gold plates. The interior of the temple had, among other treasures, the already mentioned golden disc, which represented the sun, and also a representation of the entire Inca pantheon . The mummies of the Inca rulers were placed in trapezoidal niches in the walls and decorated with golden masks and extremely finely woven fabrics. The walls were covered all around by a wide strip of gold. The adjacent room, which was dedicated to the moon goddess, was completely lined with silver. Here a silver moon disc in the shape of a woman was venerated as the bride and sister of the sun god and prayed for intercession. Gold and silver had exclusively cultic value, as gold was regarded as "the sweat of the sun" and silver as "the tears of the moon".

In its neighborhood there was also a sacred garden, in which all elements of nature, including plants and animals, were stylized as life-size, completely golden statuettes . Access to the Coricancha was denied to all who were not Inca. They brought their offerings to an adjacent square. As a token of their devotion, all visitors from their provinces brought sand with them to the capital Cusco, which is located on the divided central square, the smaller Waqaypata ("Square of Weeping"), reserved for the rulers and high nobility, and the larger Kusipata ( "Place of Joy").

As a sign of loyalty, humility and true devotion, the tribes established countless places of worship for the Inca in their provinces. The highest ceremonial place on earth is on the icy summit of Llullaillaco at an altitude of 6700 meters. Some of the cult sites can still be visited, which prove the geographical extent of the cult. The Vilcashuaman temple is located in Peru . Near the highest peak in Peru, the Nevado Huascarán, there is another temple where an Ushnu , a place of sacrifice, was located. A sun temple was also built on the sunny island on the Bolivian side of Lake Titicaca. In Caranqui , Ecuador, there was a temple that used to have jugs full of gold and silver.

The most important festival of the empire was the Inti Raymi , the winter solstice and the shortest day in the southern hemisphere on June 23 of each year. This festival was combined with thanks for all the best in the past year and at the same time the request for protection from the sun for the seeds that began soon afterwards. At these festivals, the 14 royal mummies (mallki) were carried in public procession next to the current regent. The mummies were ritually entertained with beer and meals. There was a widespread ancestral cult throughout the Andean region . However, the cult of the royal mummies was more than just ancestor worship. First and foremost, it was a fertility ceremony, because with processions and toasts, the dead kings as Illapa were asked for rain without devastating storms. In addition, they were the materialized legitimation of a dynastic-theocratic claim to rule by the Inca elite. At the same time, the cult also strengthened the ritual and social solidarity within the ten Panaqas or Panacas , the royal ayllus. The importance of this cult can possibly be read from the fact that when the Spaniards invaded Cusco, the Inca priests brought the royal mummies to safety from the conquistadors, rather than the gold. They created images of the mummy out of plaster of paris or clay, which were given authenticity with clipped hair and nails as well as his clothes. In 1559 the mummy Pachacútec was discovered by the Spaniards and transported to Lima. Indigenous people along the way bowed, kneeled and wept. It was burned to symbolize the power of the Christian religion and instead a Corpus Christi procession with 14 Catholic saints was introduced.

The chroniclers reported that about a third of the cultivated earth in each community was devoted to the sun. Agriculture, for example, gave the cult both a cultic-sacral and a fiscal-economic aspect. Everyone had to serve the empire, including the ruler himself, around whose person they developed a ritual cult. “The people of the sun do not lie, do not steal and are not lazy.” This is still the common greeting in Quechua (ama llulla - ama qillqa - ama suwa) .

Adoration of Viracocha

Although the sun cult was used as the official cult of the empire, there are still numerous reports and testimonies according to which the Inca worshiped a creator god who was named in Peru under the name Pachakamaq (son of the sun ( pacha = "earth, universe", kamay = " create, creation ”)) and in the other parts of the empire as Wiraqucha (foam of the sea, creator of earth and water) is known. According to the tradition of the Colla, Viracocha was already worshiped as the highest being among them. Pachakamaq is a deity of the central coast of Peru, the exact origin of which is uncertain. Although it seems that the first traces of Pachacámac appear in the era of the civilization of Lima. However, it seems to have flourished in the Ishmay civilization , a local civilization between the Río Rímac and Río Lurín (100–1450 AD).

According to some authors, the central deity at the Sun Gate of Tiwanaku is Viracocha. Wari ceramics are also said to show Viracocha. But already representations of gods in Chavín de Huántar probably represent Viracocha. The Mochica also prayed to their main deity, who was considered to be the creator of the world, not just of their own tribe. The Muísca also attributed the properties of Viracocha to their main deity Bochica .

Viracocha (not to be confused with Huiracocha Inca , who was also called Viracocha), who functioned as the main god of the nobility, was worshiped in a completely different way than the sun. He had neither consecrated soil nor consecrated temples except for that of the famous oracle of Pachacámac, the Kiswarkancha in Cusco and in Racchis in southern Peru. The Inca prayers that have come down to us testify to an ardor and spiritual approach that is reminiscent of a monotheistic belief. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega , the governor of Cusco, whose mother Isabel Suárez Chimpu Ocllo was a granddaughter of the great Inca ruler Túpac Yupanquí and niece of the penultimate Sapa Inka Huayna Cápac, we owe the report that Viracocha was the true god of the Inca ; the sun was therefore a "shop window deity" in the polytheistic Andes. In any case, he specified that Viracocha was a deity worshiped before the Inca. This fact is also evidenced by the accounts of other early Spanish chroniclers such as Cristóbal de Molina , Juan de Betanzos (who was married to an indigenous man) and Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa . María Rostworowski identifies Viracocha with Tunupa. Viracocha, the turned away god, whose name means "sloping surface of the heavenly lake", which undoubtedly means Lake Titicaca, indicates the inclination of the earth's axis in relation to its orbit around the sun and the resulting tumbling motion, the precession .

Syncretism

However, when interpreting Viracocha as a creator god, even as monotheism, just as caution is required as with the portrayal of Intis as a cult object in a box of the wandering Inca, which is strongly reminiscent of the Ark of the covenant of the wandering Old Testament Jews or the descriptions of other pre-Inca deities: Chascacollyo , the Beautiful with curly hair that seems to resemble Venus; Aucha , the god of justice and retribution, who is considered the father of time since his orbit takes the longest time, seems to correspond to Saturnus ; the god of war Acayoch is reminiscent of the Roman god of war Mars ; Cuatahulya resembles the Greek messenger of the gods Hermes ; Peruya , the lord of abundance, from whom the name of the country Perú (Spanish synonymous with "gold chest") may come from, resembles Jupiter . They all have astonishing similarities with ancient gods. In view of the fact that indigenous festivals were given a Christian " varnish " after proselytizing , with which they could be continued as Christian festivals under the eyes of the Spanish colonial power, just as indigenous religious ideas were transferred to Christian saints in order to continue pre-Christian practice , makes it seem appropriate in any case to show a certain amount of skepticism towards the conspicuous accumulation of parallel ideas of the conflict between Christianity and pre-Christian-Greco-Roman-Jewish civilization on the one hand and pre-Inca and Inca religious ideas on the other. The extent to which the expectation of the Christian missionaries was anticipated by the indigenous narrators, Christian chroniclers tried to classify the events and beliefs described to them in the European-pre-Christian context for their European addressees, or to what extent a completely uninfluenced autochthonous parallelism actually existed, can best be seen from the datable material Check artefacts of religions such as temples, masks, idols, figures, frescoes, textiles, grave goods, etc.

In the Andean myth, Viracocha is strikingly similar to the Quetzalcoatl myth of the Aztecs , the god of the merchants of Cholula, México: In both myths he represented an absent, benevolent creator god, a cultural hero or civilizer who disappeared over the sea. It is noticeable that Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha are represented in their respective cultures as a feathered snake, a mythical animal that is much older than z. B. the sun god Inti. Equally striking is the parallelism of an ancient deity who mythologically unites a jaguar / puma (the symbol of the moon) and a condor . Since the jaguar does not appear in the high mountains of the Andes, but in the jungle lowlands, some researchers consider the jaguar / puma deity to be evidence of a possible origin of the Inca from the lowlands. Nigel Davies takes the view that Viracocha and Quetzalcoatl are just as unkind as the rest of the Inca and Aztec pantheons, but that Cortés and later Pizarro deliberately made use of the myths of the absent god, to whom they subsequently added the attributes of the white, bearded, benevolent Of God who returns on the occasion of an omen. James Cook , who explored the Pacific about two hundred years later , was also mistaken for the return of a benevolent deity who had long since disappeared across the sea, although he had not realized this.

The US historian William Sullivan, who analyzed the Inca myths, concluded that around 200 BC. BC Viracocha appeared in many myths as the creator god on Lake Titicaca and assigned each people their own place in a kind of cultural constitution. Each tribe had its own place of origin, its paqarina , i.e. a holy well, a spring, a stream, a tree, a cave, a rock, a mountain or a hill. Countless “sacred stones” also fulfilled the function of wak'a , places endowed with supernatural holy power. While the term Huacas refers to this source of inspiration, the term Paqarina has the function of a deed of ownership that assigned each tribe their rights to use their territory and brought them into relation to their neighbors. Each Pacarina was assigned to a star in the firmament, which also put him in a firm relationship with the tribes around him. In the myth, the Paqarina fulfilled the symbol of a gate or a bridge to the stars.

worldview

In the Inca belief, the earth (Pachamama) rests on the sea (Mamaqucha) , which represents the underworld. The earth and the sky arch above it. The mountains are therefore the links between the underworld, earth and heaven, they are the breasts of the earth goddess Pachamama. The waters of Lake Titicaca, which is considered to be the center of the world, are, according to this belief, water of the sea under the earth. The lakes in the mountains are also seen as a manifestation of the subterranean sea. In this belief, waterfalls, streams and rivers are interpreted as the veins of the mountains, as the milk of Pachamamas.

Cult of the Wak'a

The introduction or spread of the sun cult by the Inca did not mean that the worship of local deities or the practice of polytheistic and animistic beliefs was prohibited. Rather, local religions were often tolerated. The cult of the Huacas or Wak'as (holy places) appears among the tolerated religions . In Quechua, the term “wak'a” can mean anything that protrudes from the ordinary - also due to its expansion - everything that is suitable as a cult object. The wak'as are real sacred or divine places in geography (such as a mountain range, an icy mountain peak, a cave, a river, or even a tree) associated with a single deity. More precisely, a place where the spirit of personalities can be felt, as in all animistic religions. Behind this is the idea of magical energy storage. They existed in virtually every region in the Inca Empire. The holy places were among the most important of the population of the Inca Empire. The religious cult of the Wak'as, the worship of sacred places and objects, was widespread. In the area of Cusco alone, according to some reports, three hundred and fifty, according to others, over five hundred wak'as are said to have existed. Numerous sacrifices were made there seasonally or annually in order to please the gods. Stone sacrifices, the piled stones at Tibetan places of worship or functionally the Christian votive tablets in some chapels and churches were not unlike, in some places piles of stones (Apachetas) piled up too high . Sacrifice and mediators also allowed the tribal spiritual specialists to connect with the spirits of the Wak'as for their advice or help. Among the intermediaries between the spiritual underworld Uku Pacha and the world of the living Kai Pacha include the occasion of Qoyllur Rit'i of pubescent youngsters shown Ukuku ( "bear").

This idea of a sacred geography, known as the “Ceque system”, was also expressed in the ritual and economic life of Cusco. Ceque originally referred to a system of milestones and boundary stones with which the distances along the imperial roads were indicated. The Wak'as were divided into Ceque categories, represented by four imaginary lines running from the Coricancha in the city center through the two districts of the capital. Three districts were cut by nine lines each, which in turn were subdivided into groups of three. The fourth district was touched by fourteen lines. The starting point of the Ceques was the Coricancha in Cusco. These lines also had symbolic meaning and referred to each and every day of the different months in the Inca calendar. Each of these 328 calendar days of the Inca year was dedicated to its own Wak'a, which was included in the Ceque system. The individual wak'as were cared for by the residents of the respective district or in the country by the ayllu , the clan or a family. At the same time, the lines divided the districts of the capital, the geography of which was symbolically interpreted as a puma. The Inca ideas of geographical and symbolic space, of time, history, religion, astronomy, social significance and organization were linked in a complex way by the Ceque system and the associated wak'as. Its most important meaning is likely to lie in the star-moon calendar encoded in it, which regulated the agricultural cycle. Already in ancient Egypt the sun was not only worshiped as god and Pharaoh as a descendant of him, but also there the pyramids in connection with the Nile must be viewed as a "sacred landscape" arranged according to astronomical criteria.

Priests and "chosen virgins"

The priests lived in the temples and other important religious shrines. They also fulfilled functions as fortune tellers, magicians and medicine men. The title of the chief priest of Cusco was Willaq Umu . He was often a brother or cousin of the Inca who was not allowed to marry and had to lead a chaste, ascetic life. He had to be vegetarian , only allowed to drink water, and often fasted for up to eight days in a row. His authority rivaled that of the Sapa Inka. As a token of his dignity, he wore a golden headgear called Wilachuku , which was adorned with an image of the sun. The Willaq Umu had power over all temples and religious buildings and could appoint or recall the priests. His tenure was lifelong. In addition to monitoring compliance with the sun cult, he crowned the new ruler and led the Inca wedding ceremony.

The Willaq Umu was supported in Tawantinsuyu by ten Hatun Willaq , who were only allowed to come from the Ayllu Tarpuntay . Together they formed the Supreme Council, chaired by Willaq Umu. Miloslav Stingl pointed out the parallel to the Jewish custom in Old Testament Israel, in which the priests came almost exclusively from the Levi tribe . The Hatun Willaq directed religious life in one of the ten regions. They were assisted by the spiritual administrators of the individual regions, who at the same time also had the function of the head of the local sun temple. At the lowest level of the clerical hierarchy were the numerous priests who, in addition to their task in the context of the sun cult, also took part in the veneration of the respective holy place or cult object through sacrifice and confession and were therefore also called Wak'arimachiq . In addition, they prophesied.

The "chosen women" called themselves aklla ( akllay = "choose, choose"; vestal virgin or for the Spaniards "virgins of the sun") and were in the service of the sun god (Intip akllan) or the Inca (Inkap akllan) . Only the most qualified were selected at the age of five and received very special training. They lived in the Akllawasi (House of the Chosen) on Calle Loreto in Cusco, learned housekeeping, cooking, preparing drinks, singing and music under the supervision of an "abbess". They devoted most of their time to weaving the finest luxury textiles for the Sapa Inca and priests. At the age of ten and thirteen they had to face another selection. If they had not convinced the Panap Apun ("master of the sister"), they returned to their family. The rest learned the prayers and cult activities of the sun cult, lived in strict chastity and were given away by the Sapa Inca at sexual maturity to nobles, warriors, dignitaries and engineers, whom they had to serve with their housewife and manual skills, but also with their feminine grace. Only those who pledged themselves to complete chastity and were called Intip Chinan wore a white religious robe and a veil called a pampacune and assisted in religious ceremonies. Their virginity was one of the highest taboos of the Inca, the violation of which resulted in the death of the seducer and the seduced including relatives, the home village and its curaca, even all plants and animals. Only the Inca himself was allowed to “love” these virgins. One can therefore imagine what a tremendous breach of taboo the Spaniards broke when they raped the sun maidens during the Conquista, assuming they were some kind of temple whores. Some authors regard the Aclla as a kind of native South American harem and the virgins as a kind of concubine of the Inca, which completed the number of concubines of the Inca.

The princesses of royal blood were called the Ñustas . Among them, the sister of Sapa Inka was appointed Quya (Queen), the main wife of the Inca ruler.

Divination

The prophecy had a decisive place in the Inca civilization. She was called before every action and nothing important could be done without first getting the prospect. Fortune telling was used to diagnose disease, to predict the outcome of a battle, to exorcise or to punish a crime. Divination also made it possible to determine which sacrifices had to be made to which gods. The Incas believed that life was controlled by invisible forces. To represent them, the priests resorted to divination.

Different methods of divination existed: one could watch a spider move or analyze the fall of coca leaves on a plate. Others predicted the future from corn kernels or the innards of sacrificed animals, especially sacrificed birds. Lower priests who knew how to talk to the dead were called Ayartapuc . Ayahuasca could also be drunk , which had hallucinogenic effects on the central nervous system. This drink allowed contact with the supernatural powers. Prophecies were also made from the analysis of the lungs of white lamas sacrificed daily in Cusco. The carcasses of the ritually slaughtered animals were burned on piles of artistically designed logs.

Sin and confession

Disease has traditionally been viewed in the Andes as a result of curses or sins. Every Inca priest had the duty to take confession from the Puriq ("traveler", head of an ayllus). The nobles and the Inca themselves confessed to Inti directly without the involvement of a priest. The atonement consisted of a ritual bath in the white water of a mountain stream, which was supposed to wash away sin and guilt. Terms like confession and atonement presuppose something like “sin”, which is actually a Judeo-Christian term. The ritual cleansing is also strikingly reminiscent of a Judeo-Christian context. Sinners who did not belong to the noble caste, which, due to their social position, belonged to a quasi-sin-free, pure caste and who had not confessed their grave offenses, suffered great torments after their death in a kind of underworld, a cave in the interior of the earth.

Offerings and sacrifices

There are numerous descriptions of ofrendas , sacrifices and offerings which were brought to the gods or wak'as and which belonged to the rhythm of life of the people. The Incas sacrificed certain things that they considered worthy in the eyes of the gods, especially Pachamama, mother earth. These offerings could include take the form of chicha (quechua: aqha , corn beer), corn pods, spondylus clams, or coca leaves.

Animal sacrifice

A sacrifice was made on every important occasion. The most common animal sacrifice was a llama. At the end of the celebration of the sun cult, many animal sacrifices were reported.

In La Paz , the seat of government in Bolivia, there are still markets where countless mummified lama embryos are offered. The buyers are primarily indigenous women, very rarely tourists, from whom the embryos are usually kept hidden. In the mountains, when a house is being built, a parched lama embryo is walled in to protect and bless the house and residents.

Human sacrifice

During periods of great difficulty - for example periods of drought, epidemics or illness of the Inca ruler - there was human sacrifice . Compared to the Aztecs, the number of human sacrifices in Tawantinsuyu was low.

The people who were sacrificed, whether men, women or children, were in good physical condition and in perfect constitution. The human sacrifices were often taken from the defeated people and viewed as part of the tribute. Preference was given to boys and girls around the age of ten who would happily sacrifice their lives.

Legend has it that Tanta Qarwa, a little girl of ten, was chosen by her father to be a sacrifice for the Inca. The child, probably of perfect physical appearance, was then sent to the ruler in Cusco, where celebrations and parades were held in honor of his courage. Then she was buried alive in a grave in the Andean mountains.

The children who were considered pure met the ruler. Ceremonies were held in her name. According to the Inca belief, the sacrificed child became a god the moment after death. Before being buried alive, the child was given chicha to drink, an alcoholic corn beer that was given to reduce sensory perception. The priests continued the ceremonies of honor until the spirit left the earth. Similar rites (" Capacochas ") were reported in other pre-Columbian societies, particularly the Aztecs .

The day of the Andean winter solstice (June 23 in the southern hemisphere) was celebrated as a religious festival, during which 10,000 llamas were sacrificed, their blood was collected and sprayed on steep rock faces in all parts of the empire because on this day the sun closes a gateway to the Milky Way opened the ancestors. At intervals of four years , the Incas celebrated their Qhapaqhucha -Fest ( Qhapaq = priest, astronomer, king hucha = severe energy please the king, today: "sin"), to the solemn processions of priests, dignitaries and elect 8- to 12 year old children moved to Cusco with their parents from all over the country. After several days of sacrifice by lamas, some of the children in Cusco were ritually slain or strangled.

In the course of Inca history, however, human sacrifices were replaced by sacrifices of coca, chicha, feathers, guinea pigs, by special robes woven by the sun maidens, and by white, flawless llamas. William Sullivan explains the child sacrifice in a mythological and religious way to the effect that the Inca rulers astronomically interpreted the departure of the sun from their intersection with the Milky Way in such a way that the Inca should never again have a chance to ascend to the stars and thus to their ancestors. With the child sacrifices and the incredibly high efforts to quickly and efficiently develop all resources of the Andes, the Inca rulers wanted to please the sun and the stars. H. Stop the time or the course of the sun, tie it up and thus allow the people to continue to have access to their ancestors. As a symbol, Pachacútec Yupanquí created the Intiwatana ("to tie up the sun") a rectangular cut and vertically protruding stone from a complicated rock shaped according to astronomical aspects. It was surrounded by a semicircular wall and in every larger Inca settlement, e.g. B. in Pisac , in Machu Picchu or in Paititi was to be found. Many of these strangely shaped rocks were destroyed by the Spaniards, so that their astronomical significance no longer seems to be identifiable from the fragments.

Inca myth of the flood