Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (born 37/38 AD in Jerusalem ; died around 100 probably in Rome ) was a Jewish-Hellenistic historian.

As a young priest from the Jerusalem upper class, Josephus played an active role in the Jewish War : in the spring of 67 he defended Galilee against the Roman army under Vespasian . In Jotapata he was taken prisoner by the Romans. He prophesied to the general Vespasian his future empire. As a freedman , he accompanied Vespasian's son Titus in the final phase of the war and thus witnessed the conquest of Jerusalem (70 AD) . With Titus he came to Rome the following year, where he spent the rest of his life. He received Roman citizenshipand from then on lived on an imperial pension and the produce of his estates in Judea. He used his leisure time to write several works in Greek:

- a history of the Jewish War (cited in this article as: Bellum ),

- a history of the Jewish people from the creation of the world to the eve of this war (cited as: Antiquitates ),

- a short autobiography as an appendix (quoted as: Vita )

- and as a late work a defense of Judaism against the criticism of contemporary authors (cited as: Contra Apionem ).

Roman historians only mentioned Josephus as a Jewish prisoner with an oracle about Vespasian's empire. For all information about his biography one is therefore dependent on the Bellum and the Vita .

The writings of Josephus were preserved because they were discovered by Christian authors as a kind of reference work as early as late antiquity . Readers of the New Testament found useful background information in Josephus : he was the only contemporary author who wrote about Galilee in detail and with his own local knowledge. The city of Jerusalem and the temple there are also described in detail. Josephus mentioned John the Baptist and probably also Jesus of Nazareth - however, this text passage (the so-called Testimonium Flavianum ) has been revised in a Christian way and the original wording is uncertain. In the Bellum Josephus described in detail the suffering of the people in besieged Jerusalem. He broke with the conventions of ancient historiography, which obliged him to be objective in order to complain about the misfortune of his homeland. Since Origen, Christian theologians interpreted these war reports as God's judgment against the Jews, a consequence of the crucifixion of Jesus, which in their eyes was caused by Jews .

For the history of Judea from around 200 BC From BC to AD 75, Josephus' works are the most important ancient source. His unique selling point is that, as an ancient Jew, he gives information about his childhood and youth on the one hand and his role in the war against Rome on the other. However, the reader never encounters the young Galilean military leader directly, but rather contradicting images that an older Roman citizen created of his former self.

More recent research deals with how Josephus sought his way as a Jewish historian in the Rome of the Flavians . The inhabitants of Rome were constantly confronted with the subject of Judea, because Vespasian and Titus celebrated their victory in an insurgent province with a triumphal procession, coinage and monumental architecture as if it were a new conquest. Josephus set himself the task, as one of the defeated, to tell the story of this war to the victors in a different way. The result is a hybrid work that combines the Jewish, the Greek and the Roman. That makes Josephus an interesting author for post-colonial reading .

Surname

"[I am] Iṓsēpos, son of Matthías, from Jerusalem, a priest."

This is how Josephus introduced himself to the reader in his first work. It had the common Hebrew name יוסף Jôsef and transcribed it as Ἰώσηπος Iṓsēpos into Greek , with non- aspirated p, probably because Greek personal names ending in -phos are rather rare. He remained true to the Hebrew naming conventions, so that the name by which he must have been known in his youth can be reconstructed:יוסף בן מתתיהו Jôsef ben Mattitjāhû .

Josephus himself did not use the Roman name Flavius Iosephus in his writings. It is only attested by Christian authors from the late 2nd century onwards. In view of Josephus' close ties to Emperor Vespasian after the Jewish War, however, it can actually be assumed that he granted him Roman citizenship . Presumably, as was common practice, Josephus took over the prenomen and the gentile noun of his patron, whose full name was Titus Flavius Vespasianus , and added his previous non-Roman name Iosephus as a third component of the name ( cognomen ). Accordingly, it can be assumed that his Roman name was Titus Flavius Iosephus , even if the praenomen Titus is not attested in the ancient sources.

Life

Family of origin and youth

Josephus stated that he was born in the first year of the reign of Emperor Caligula ; elsewhere he mentioned that his 56th year was the 13th year of the reign of Emperor Domitian . This results in a date of birth between September 13, 37 and March 17, 38. The family belonged to the Jerusalem upper class and owned land in the outskirts of the city. According to the Vita , father and mother came from the priestly-royal family of the Hasmoneans , although this is not explained further in the case of the mother. The father Matthias belonged to the first of 24 priestly service classes. However, Matthias could not trace himself back to the Hasmoneans in a purely patrilineal generation . He was descended from a daughter of the high priest Jonathan .

Ernst Baltrusch suspects that Josephus wanted to present his traditional Jewish-priestly socialization in the autobiography in such a way that it was understandable for the Roman readership as an aristocratic educational path - alien and familiar at the same time:

Josephus had a presumably older brother Matthias, named after his father, and was brought up together with him. At around 14 he was known as a child prodigy ; "The high priests and the noblemen of the city" had met with him repeatedly to get details of the Torah explained. A literary topos , for comparison we can cite Plutarch's biography of Cicero : the parents of classmates attended class to admire Cicero's intelligence.

Just as a young Roman left home at the age of 16 to prepare for participation in public life under the supervision of a tutor, Josephus stylized the next step in his biography: First he explored the philosophical schools of Judaism (as such he presents Pharisees and Sadducees and Essener ): "With strict self-discipline and with great effort I went through all three." Then he entrusted himself for three years to the direction of an ascetic named Bannus , who was staying in the Judean desert . The Bannus episode is an example of how Josephus invited the reader to transcultural readings:

- In the Jewish tradition, the desert was a place of religious experience.

- Frequent pourings of cold water, as practiced by Bannus, were easily understandable in the context of Greco-Roman bathing culture.

- The idea of a vegetarian clad in tree bark, however, gave the whole thing an exotic note : Herodotus's description of Indians and Scythians echoes.

Nothing certain can be inferred from the vita about an actual stay in the desert of the youthful Josephus .

At the age of 19, Josephus returned to Jerusalem and joined the Pharisees. For a young man of the upper class, the choice of the Sadducee religious party would have been closer. But if he has already decided in favor of the Pharisees, it is difficult to understand why his historical works paint a rather negative image of them. In the context of the Vita it can be stated that Josephus fulfilled the expectations of the audience: his years of apprenticeship had led to a life decision, and so he had an inner orientation when he stepped out into public. The Vita would be misunderstood if one inferred from it that Josephus lived according to Pharisaic rules in everyday life. It was desirable for public figures to set aside the philosophical inclinations of their youth in favor of their political tasks.

Formative for Josephus' work was not being a Pharisee, but being a priest , to which he repeatedly referred. This is the reason why he can interpret his own tradition competently and the reader can trust his presentation. Temple service for young priests began at the age of 19 or 20. His inside knowledge shows that Josephus knew him from personal experience. In his vita he passed the years from 57 to 63 AD with silence. He gave the impression that he had only taken on the role of an observer during these politically turbulent times.

Rome trip

According to Plutarch , one could begin a public career in two ways, either by parole in a military action or by appearing in court or participating in an embassy to the emperor. Both required courage and intelligence. The Vita of Josephus corresponded well to this ideal by highlighting Josephus' trip to Rome in 63/64. He wanted to obtain the release of Jewish priests whom the Prefect Felix had "arrested for a slight and fictitious cause" and then had them transferred to Rome so that they could answer before the emperor. It remains unclear whether Josephus acted on his own initiative or by whom he was commissioned. A rendition to Rome suggests more serious charges, perhaps political ones.

The literary formation of this episode of the Vita is obvious. Josephus stated that he became acquainted with Aliturus, an actor of Jewish descent, in a circle of friends who made contact with Nero's wife Poppaea Sabina . Through their intervention, the priests were released. Aliturus may be a literary figure modeled on the well-known mime Lucius Domitius Paris . Fittingly for an author of the Flavier period, this would have been an ironic point against the conditions at Nero's court: actors and women ran the business of government. The episode of the trip to Rome shows the reader of Vita that her hero was suitable for diplomatic missions. Research is debating whether, in the opinion of the Jerusalemites, the Rome Mission replaced Josephus with qualified and lacking military experience for the responsible task of defending Galilee.

Military leader in the Jewish war

When Josephus returned to Judea, the uprising was already underway, which then expanded into war against Rome. Josephus wrote that he tried to moderate the Zealots with arguments . “But I couldn't get through; because the fanaticism of the desperate had spread too much. ”Then he sought refuge in the inner temple area until the zealot leader Manaḥem was overthrown and murdered (autumn 66). However, the temple was not a center of the Peace Party, on the contrary: The temple captain Elʿazar had his power base there, and Josephus seems to have joined Elʿazar's group of zealots.

A punitive expedition by the governor of Syria, Gaius Cestius Gallus , ended in the autumn of 66 with a Roman defeat at Bet-Ḥoron ; afterwards the Roman administration in Judea collapsed. Long-smoldering conflicts between different population groups escalated. Chaos was the result. "In fact, a group of young Jerusalemites from the priestly aristocracy immediately tried to take advantage of the uprising and establish a kind of state in Jewish Palestine ..., but with very little success" ( Seth Schwartz ).

Already in the first phase of the uprising it was "groups and people beyond the traditional power and constitutional structures" who determined the politics of Jerusalem. Nevertheless, Josephus made a point of stylizing the Jerusalem of the year 66 as a functioning polis ; a legitimate government sent him to Galilee as a military leader, and he was also responsible to it. In the Bellum , Josephus only enters the political stage at this moment, and as strategos in Galilee he does everything possible to help the cause of the rebels to succeed - until, under dramatic circumstances, he goes over to the side of the Romans. The presentation of the later written Vita is different: Josephus is sent here together with two other priests by the “leading people in Jerusalem” with a secret mission to Galilee: “So that we can move the evil elements to lay down our arms and teach them that it is better to keep them available for the elite of the people. "

Strategically, Galilee was of great importance, as it was foreseeable that the Roman army would advance towards Jerusalem from the north. In the Bellum , Josephus had numerous places fortified and trained his fighters in the Roman style. Louis H. Feldman commented: Of course it was possible that Josephus accomplished great military achievements, but he could just as well have copied ancient military manuals when he was writing the Bellum Report on one's own measures conspicuously correspond to the procedure recommended there.

The Vita tells how political opponents brought Josephus into distress several times, but each time he turned the situation to his own advantage. In the sense of his secret mission, the Vita is not about an effective defense of Galilee, but about keeping the population calm and waiting to see what the Roman army would do, and so their hero apparently wanders from village to village for weeks without a plan.

What the historical Josephus did between December 66 and May 67 can only be guessed. Seth Schwartz assumes that he was one of several Jewish warlords who competed in Galilee, an “adventurer acting on his own” and thus less a representative of the state as a symptom of the political chaos. There were armed groups in Galilee even before the war began. Josephus tried to create a mercenary army out of these unorganized gangs. With this he was relatively unsuccessful and with his militia only had a small power base of a few hundred people in the town of Tarichaeae on the Sea of Galilee , according to Schwartz. He bases his analysis on the vita :

- Sepphoris , one of two important cities in Galilee, remained strictly loyal to Rome.

- Tiberias , the other major city, chose to resist but did not submit to Josephus' command.

- "The rural areas were dominated by a wealthy and well-connected personality", namely Johannes von Gischala . He was later one of the leading defenders of Jerusalem, was carried along in the triumphal procession of the Flavians and spent the rest of his life in Roman prison.

In the spring and summer of 67 three Roman legions arrived in Galilee, reinforced by auxiliary troops and armies of client kings, a total of around 60,000 soldiers under the command of Vespasian . The rebels could not face this superiority in a battle. But Josephus really intended to stop the Roman army. After taking Gabara, Vespasian advanced towards Jotapata . Josephus met him from Tiberias and holed up in this mountain fortress. The decision to seek battle with Rome here shows Josephus' military inexperience.

Josephus describes the defense of Jotapata in detail in the Bellum . Jotapata withstood the siege for 47 days, but was finally conquered. What then follows gives the impression of a literary fiction: Josephus "stole himself through the middle of the enemy" and jumped into a cistern, from there into a cave, where he met 40 distinguished Jotapaten people. They held out for two days, then their hiding place was betrayed. A Roman friend of Josephus brought Vespasian's offer: surrender to life. Josephus had now returned to his priesthood, his qualifications to interpret holy scriptures and to receive prophetic dreams. He prayed:

“Since you like it that the people of the Jews that you created are sinking on their knees, and all happiness has passed to the Romans, I willingly surrender myself to the Romans and stay alive. I call on you to testify that I am not taking this step as a traitor, but as your servant. "

So far there has been no talk of prophetic dreams, and calling on God to witness is not part of the prayer but the oath form: These elements explain why Josephus does not die heroically but must survive for the reader. Mind you, Josephus surrenders not because resistance to Rome would be pointless, but because he has a prophetic message to deliver. The 40 Jotapaten were determined to commit suicide. Josephus suggested that lot should be chosen as to who should be killed next. Josephus and a man whom by agreement he should have killed were the last remaining and surrendered to the Romans. That Josephus manipulated the lottery procedure is an obvious suspicion; However, this is only expressly stated in the medieval Old Slavic translation of the Bellum .

In the Roman camp

Prisoner Vespasians

According to Josephus, Vespasian went to Caesarea Maritima just a few days after the fall of Jotapata . Josephus spent two years there in chains as a prisoner of war. Since he was a usurper , the legitimation through deities was of great importance for Vespasian's later empire. And he received such omina , among other things from the God of the Jews .

“In Iudaea he once consulted the oracle of the God of Carmel. The oracles made him very confident, insofar as they seemed to promise that he would succeed in what he had in mind and planned, however important it was. And Josephus, one of the noble prisoners, assured confidently and very decisively, when they put him in chains, that he would be freed by this very man shortly, but then he would already be emperor. "

Tacitus mentioned the oracle on Mount Carmel and omitted the prophecy of Josephus. Due to mentions in Suetonius and Cassius Dio it is probable that "Josephus 'saying found its way into the official Roman list of Omina." If one accepts the dating of Josephus' capture to the year 67, he was speaking of Vespasian at a point in time as future Emperor when Nero's rule began to falter, but Vespasian's rise was not yet in sight. The Bellum's text is corrupt; Reinhold Merkelbach suggests a conjecture and paraphrases the oracle-style saying of Josephus as follows:

“You want to send me to Nero? Do you think that this is still possible (= is he still alive at all)? How long will Nero's successors stay (in government)? You yourself are emperor [...] "

It has been assumed that Josephus only predicted military success for him, or that Vespasian already had corresponding ambitions at this point in time and the prophecy arose out of a kind of creative collaboration between the general and his prisoner.

As the illustration in Suetonius and Cassius Dio shows, Josephus linked the fulfillment of his prophecy with his change of status in such a way that Vespasian had to release him in order to be able to use the prophecy for himself. Otherwise, Josephus' ability to foresee the future would have been devalued. On July 1, 69, the legions stationed in Egypt proclaimed Vespasian as emperor. Josephus was released afterwards. His chain was severed with an ax to remove the stigma of imprisonment. Vespasian took him to Egypt in October 69 as a symbol of his legitimate claim to the throne. He stayed in Alexandria for about eight months , keeping his distance from the atrocities of the civil war and waiting for developments in Rome. Vespasian received other Omina and acted as a miracle worker himself. One sees stagings and propaganda measures in favor of the future emperor. During this phase there was hardly any contact with Josephus, who used the time privately and married an Alexandrian woman.

In the wake of Titus

Josephus came with Titus from Egypt to Judea in the spring of 70 and witnessed the siege of Jerusalem . He served the Romans as an interpreter and interviewed defectors and prisoners. Josephus wrote that he was in danger from both warring parties. The Zealots tried to get the traitor under their control. On the other hand, some members of the military disapproved of Josephus being in the Roman camp because he brought bad luck.

It was important to Josephus that he did not take part in looting in conquered Jerusalem. Titus had allowed him to take whatever he wanted from the rubble. But he only released captured Jerusalemites from slavery and received "holy books" from the spoils of war as gifts. Steve Mason comments: Josephus was always interested in books, and the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple added many valuable manuscripts to Josephus' private library. By freeing prisoners of war, Josephus proved himself to be an aristocratic benefactor of his friends. He was also able to save his brother Matthias in this way.

Writer in the Rome of the Flavians

The population in the metropolis of Rome was very heterogeneous. Glen Bowersock highlights a group of immigrants: elites from the provinces who have been "transplanted" to Rome by members of the Roman administration in order to write literary works in the spirit of their patron. Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote a monumental history of Rome, while Nikolaos of Damascus wrote a world history that Josephus later used extensively. Both can be seen as role models for Josephus.

“And when he [Titus] embarked for Rome, he took me on board and did me all honor. After our arrival in Rome I experienced special care on the part of Vespasian: He gave me accommodation in the house he had lived in before he came to power, honored me as a citizen of Rome and granted me financial support [...] "

Josephus arrived in Rome in the early summer of 71. As one of the many clients of the Flavian imperial family, he was accommodated. Since he did not live in the imperial residence on the Palatine Hill , but in the Domus der Flavians on the Quirinal , one cannot conclude from this that Josephus had easy access to the imperial family and was able to exercise political influence. Suetonius mentioned that Vespasian gave Latin and Greek rhetors a hundred silver denarii a year. It is believed that Josephus also benefited from this imperial pension. According to Zvi Yavetz , the perks that Josephus listed in the Vita ranked him among doctors, magicians, philosophers and jesters - the less important people in Titus' entourage.

The triumph that Vespasian and Titus celebrated in Rome in 71 for their victory over Judea was described by Josephus in a particularly colorful and detailed manner. It is the most comprehensive contemporary description of an imperial triumphal procession. This event must have been difficult to bear for the large Jewish population of Rome. It is all the more astonishing that Josephus gave the celebrations in the Bellum a cheerful note and presented the cult objects looted in the temple as the main attractions. Apparently he found some consolation in the fact that the showbread table and menorah were later set up in a worthy place in the Templum Pacis . The temple curtain and the Torah scroll were kept in the imperial palace after the triumph, insofar as Vespasian took them under his protection - if one tried to gain something positive from it. Josephus 'description of the triumph in Bellum emphasized the Flavians ' loyalty to tradition (which corresponded to their self-image); the prayers and sacrifices that accompanied the triumphal procession, according to Josephus, happened exactly according to ancient Roman custom - he blinded off that they belonged to the cult of Jupiter Capitolinus . One can assume that he, who prophesied the empire to Vespasian, was also put on display in the triumphal procession; but nothing is said about this with Josephus.

Hannah M. Cotton and Werner Eck paint the picture of a lonely and socially isolated Josephus in Rome; symptomatic of this is the dedication of three works in the 1990s to a patron named Epaphroditos. This could not be about Nero's freedman of the same name , because he fell out of favor around the same time as Josephus' works were published. Probably Epaphroditos is meant by Chaeronea - highly educated and wealthy, but not a member of the socio-political elite.

Jonathan Price also suspects that Josephus did not have access to literary circles in the capital, if only because his Greek was not so flawless that he could have presented his own texts in these circles. Eran Almagor judges somewhat differently: a high command of the language was actually required in the Second Sophistic . But non-native speakers could also be successful if they confidently addressed their role as outsiders and thus also the originality (or hybridity) of their work.

Tessa Rajak points out that when Josephus lived in Rome, he still had connections in the eastern Mediterranean: through his country estates in Judea, but above all through his marriage to a noble Jewish woman from Crete. Josephus' work contains no information on the circumstances under which he met this woman or her family.

Marriages and children

Josephus casually mentioned his wife and mother in a (literary) speech he gave to the defenders of the besieged Jerusalem. Both were in the city and apparently died there. When Josephus was captured by the Romans, Vespasian arranged for him to marry "a local girl from the Caesarean women prisoners of war ." As a priest, Josephus should not have married a prisoner of war. This woman later separated from Josephus on her own initiative when he was released and accompanied Vespasian to Alexandria. He entered into a third marriage in Alexandria. Josephus and the anonymous Alexandrian had three children, one of whom was Hyrcanus (born 73/74), who reached adulthood. When he then lived in Rome, Josephus sent his wife away because he "disliked her character traits [...]". He married a fourth time; He describes this marriage as a happy one: his wife was "at home in Crete, but Jewish by birth [...], her parents were extremely elegant [...], her character distinguished her from all women [...]." two sons named Justus (born 76/77) and Simonides Agrippa (born 78/79). It is no accident that Josephus withholds the names of the women in his family. This corresponds to the Roman custom of referring to women only by the name of their gens .

Last years of life

In the Vita Josephus mentions the death of Herod Agrippas II. Photios I noted in the 9th century that Agrippa's year of death was the "third year of Trajan ", i.e. H. the year 100. From this the statement often found in the literature is derived that Flavius Josephus died after 100 AD. However, many historians date Agrippa's death to 92/93. Then it is likely that Flavius Josephus died before the fall of Domitian (September 8, 96) or that he ended his literary activity. This is supported by the fact that there is no reference to the emperors Nerva or Trajan in his work .

plant

linguistic proficiency

Josephus grew up bilingual in Aramaic and Hebrew. He acquired a good knowledge of the Greek language in early childhood, but probably received no literary rhetorical lessons. In his own estimation, he had a better command of Greek in writing than orally. His works are typical examples of Atticism , as it was cultivated as a reaction to Koine Greek in the imperial era. After the very good Greek of Bellum , Antiquitate s and Vita are qualitatively inferior; With Contra Apionem a higher language level is achieved again.

Since he lived in Rome, knowledge of Latin was essential for Josephus. He did not address them, but the evidence speaks for it: All of Josephus' Greek writings show a strong influence of Latin, both on syntax and on vocabulary. This remained consistently high, while the Aramaic color waned over time.

Aramaic first work

In the foreword of the Bellum , Josephus mentioned that he had previously compiled and sent a text on the Jewish War "for non-Greeks from within Asia in their mother tongue." This writing has not survived, it is not mentioned or quoted anywhere else. It could be z. E.g. a group of Aramaic letters that Josephus may have addressed to relatives in the Parthian Empire during the war . Jonathan Price notes that Josephus sought his first audience in the East. He suspects that Josephus was most likely to have success later in Rome with readers with roots in the eastern Mediterranean.

Older research assumed that Josephus' works were commissioned by Flavian propaganda. A text written in Greek would, however, have been understandable in the Parthian Empire and its political message would have been easier to control. That makes an Aramaic propaganda script implausible.

Jewish War (Bellum Judaicum)

Soon after his arrival in Rome (71 AD), Josephus began, probably of his own accord, to work on a historical work on the Jewish War. Staff “for the Greek language” supported him, as he later wrote in retrospect. The research opinions on the contribution of these employees vary widely: Representatives of the maximum position assume that strangers with a classical education would have contributed significantly to the text. A minimal position, on the other hand, would be the assumption that Josephus had his texts checked for linguistic errors before publication to be on the safe side. In any case, the Bellum is not an expanded translation from the Aramaic, but a work designed from the outset for a Roman audience.

If writing was his own idea, that does not mean that Josephus could or would write objectively about the war. Since he had a client relationship with the Flavians, it was natural to portray them positively. "The Flavian house had to emerge from the conflict with the Jewish people as an unsullied victor," said Werner Eck . The main culprit, therefore, was the wicked zealots , who more and more defiled the temple and dragged the entire Jerusalem population with them into ruin:

"Those who forced the hand of the Romans to intervene against their will and let the fire fly on the temple, were the tyrants of the Jews."

But Rome should be partly to blame for the outbreak of war. Josephus had a number of incompetent prefects appear in the Bellum because he could not dare to criticize their superiors, the senatorial governors of Syria .

In the foreword, Josephus confessed to the meticulously accurate historiography in the manner of a Thucydides , but also announced that he wanted to complain about the misfortune of his homeland - a clear break in style that should not have pleased every ancient reader. His dramatic-poetic historiography expanded the established form of war representation to include the perspective of the suffering population. Blood flows in rivers, corpses are rotting on the Sea of Galilee and in the alleys of Jerusalem. Josephus combined self-experienced and symbolic images to create impressive images of the atrocities of war: starving refugees eat their fill and die of excess. Auxiliary soldiers slash defectors' bodies because they hope to find gold coins in their bowels. The noble Jewess Maria slaughters her baby and cooks him.

Josephus' image of Titus is ambivalent. The Bellum provides illustrative material and at the same time excuses for the cruelty that has been said of it . An example: Titus sends out horsemen every day to pick up poor Jerusalemites who have ventured out of the city in search of food. He has them tortured and then crucified within sight of the city . Titus felt sorry for these people, but he could not let them go, so many prisoners could not be guarded, and finally: Their painful death should move the defenders of Jerusalem to surrender. The Bellum upholds the fiction that (thanks to the mildness of Titus) everything could have been fine if only the Zealots had given in.

That Titus wanted to spare the temple runs as a leitmotif through the entire work, while all other ancient sources suggest that Titus had the temple destroyed. In order to relieve Titus of the responsibility for the temple fire, Josephus accepted to portray the legionnaires as undisciplined as they penetrated the temple area. That, in turn, did not give Titus and his commanders a good report. The majority of today's historians, like Jacob Bernays and Theodor Mommsen, consider the portrayal of Josephus to be implausible and prefer the version of Tacitus , which has been passed down through Sulpicius Severus . That this was the official version is also shown by a display board with the triumphal procession depicting the temple fire. Tommaso Leoni takes the minority opinion: the temple was burned down against the will of Titus through the collective indiscipline of the soldiers, but after the city was taken, the only option was to commend the victorious army. What had happened was interpreted in retrospect as being in accordance with the orders.

Once completed, Josephus circulated his work in the usual way by distributing copies to influential people.

“I had such enormous confidence in the truth (of my report) that it seemed appropriate to me first of all to take the chief generals of the war, Vespasian and Titus, as witnesses. First of all, I gave the books to them, after those many Romans who had also participated in the war; but then I was able to sell them to many of our people. "

Titus was so taken with the Bellum that he declared it the authoritative report on the Jewish War and had it published with his signature, according to the Vita . James Rives suspects that Titus was increasingly interested in being considered a gracious Caesar and therefore approved of the image that Josephus painted of him in the Bellum .

The last date mentioned in the book is the inauguration of the Templum Pacis in the summer of 75. Since Vespasian died in June 79, Josephus' work was apparently ready before this date that he could present it to him.

Jewish antiquities (Antiquitates Judaicae)

Josephus stated that he had completed this extensive work in the 13th year of Domitian's reign (93/94 AD). He designed the 20 books of Jewish antiquities based on the model of the Roman antiquities that Dionysius of Halicarnassus had written a century before him, also 20 books. Antiquities ( ἀρχαιολογία archaiología ) has the meaning of early history here.

The main theme of the antiquities is presented programmatically at the beginning: From the course of history the reader can recognize that following the Torah (the “excellent legislation”) helps to a successful life (εὐδαιμονία eudaimonía “happiness in life”). According to Josephus, Jews and non-Jews alike should orientate themselves towards this. From creation to the eve of the war against Rome (66 AD), the story is told in chronological order. In doing so, Josephus initially followed the biblical description, some of which he rearranged. Although he claimed that he had precisely translated the sacred texts, his own achievement in the Antiquitates was not translation, but free retelling, geared to the tastes of the public. He probably had language skills and access to the Hebrew text, but he used existing Greek translations because this made his work much easier. He did not mark where his Bible paraphrase ends in Book 11, giving the impression that the antiquities were altogether a translation of Jewish holy scriptures into Greek.

In his description of the Hasmoneans (Books 12-14), Josephus had to fend off the obvious idea that their struggle for freedom against the Seleucids in 167/166 BC. With the revolt of the Zealots against Rome in 66 AD. The most important source is the 1st Book of the Maccabees (1 Makk), which Josephus had in Greek translation. This work was probably written down during the reign of John Hyrcanus or in the first years of Alexander Jannäus (around 100 BC). It served the legitimation of Hasmonean rule; for 1 Makk the Hasmoneans were not a party that competed with others, but fighters for “Israel”, their supporters were the “people”, their domestic opponents were all “godless”. Josephus claimed in the Vita to be related to the Hasmoneans and gave his son the dynastic name Hyrcanus. But in the antiquities he removed the dynastic propaganda that he read in 1 Makk. In Contra Apionem , Josephus defined what, from his point of view, legitimized a war: “We calmly endure the other impairments, but as soon as someone wants to force us to touch our laws, we start wars as the weaker ones, and we end up in misery to the utmost Josephus entered these motifs in his paraphrase of 1 Makk. So the fight was for the freedom to live according to traditional laws - and if necessary to die as well. The picture of the founder of the dynasty, Simon, is less euphoric than in 1 Makk; Johannes Hyrcanus is honored as ruler, but his actions in government are criticized in detail. With Alexander Jannäus his cruelty and the increasing domestic political tensions under his government relativize the territorial gains that he achieved with his aggressive foreign policy.

While he was able to use the world history of Nikolaos of Damascus for the reign of Herod (books 15-17) , no such high-quality source was available to him for the subsequent period. Book 18, which deals with the time of Jesus of Nazareth and the early church , is therefore “patchwork”. Josephus had a relatively large amount of information about Pontius Pilate , who was mentioned in the Bellum as one of the prefects of the pre-war period. Daniel R. Schwartz suspects that he was able to inspect archival material in Rome that arose in connection with the hearing of Pilate about his administration.

In the historical-critical exegesis of the New Testament there is broad consensus that the mention of Jesus of Nazareth ( Testimonium Flavianum ) was revised in Christian terms in late antiquity. The original text of Josephus cannot be reconstructed with certainty. According to Friedrich Wilhelm Horn , however, it is likely that Josephus wanted to say something about the urban Roman Christians he had heard of during the years of his stay in Rome. He also had information about Jesus from earlier times that reached him in Galilee or Jerusalem. Josephus was somewhat astonished to find that the "tribe of Christians" still worshiped Jesus even though he had been crucified. However, the Testimonium Flavianum is not well placed in context. A complete Christian interpolation is unlikely, according to Horn, but cannot be ruled out.

According to Josephus' presentation, John the Baptist taught an ethical way of life. Like the Synoptic Gospels , Josephus also reports that Herod Antipas had the Baptist executed and that many contemporaries criticized this execution. Josephus did not establish a connection between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth. In contrast to the Testimonium Flavianum , the authenticity of Josephus' description of the Baptist is very likely. This is supported by their early evidence in Origen , their typical Josephian vocabulary and their content, which differs markedly from the Anabaptist image of the New Testament.

From my life (Vita)

Autobiography writing became fashionable in the last decades of the Roman Republic; the Vita of Josephus "represents the oldest [surviving] example of its genus." The main part deals with the few months that the author spent as a military leader in Galilee. The Roman siege of Jotapata and the capture of Josephus omits the Vita. Linguistically, the Vita is the worst of Josephus' works. It is unclear what Josephus intended with this apparently hastily written down text. It is designed as an appendix to the Antiquities , i.e. it was written down in 93/94 AD or shortly afterwards. It can be assumed that the Vita , like this great work, was addressed to educated non-Jews in Rome who found Jewish culture interesting. The Vita consistently expects the audience to sympathize with an aristocrat who has paternalistic care for ordinary people and therefore tries to keep them calm with tactical maneuvers.

Most research has assumed that an opponent from the time in Galilee would reappear years later in Rome and raise allegations that troubled Josephus: Justus of Tiberias . However, it was known of Josephus in Rome that he had been a military leader of the rebels and, according to his own account in the Bellum, even a particularly dangerous opponent of Rome. Justus couldn't shock anyone in the 1990s by claiming that young Josephus was anti-Roman. Steve Mason therefore proposes a different interpretation: that Josephus is constantly challenged by rivals and confronted with accusations in the Vita , serves the purpose of emphasizing the good character (ἦθος ẽthos ) of the hero all the better. Because rhetoric needs opposing positions that it can overcome with arguments. In this respect, Josephus of the Vita needs enemies. Uriel Rappaport, on the other hand, sees self-portrayal in the Bellum and in the Vita as being based on the author's personality. This suffered from the fact that he had failed as a military leader and that his education according to Jewish and Roman criteria was only moderate. That is why he created an ideal self in the literary figure "Josephus" : the person he would have liked to be.

About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem)

The last work by Josephus, written between 93/94 and 96 AD, deals with ancient hostility towards Jews. In a first part Josephus pointed out that Judaism is a very old religion, although it is not mentioned in the works of Greek historians (which only shows their ignorance). His counterparts were the "classical Greeks", not their descendants, Josephus' contemporaries. In order to defend his own culture, he attacked the cultural dominance of this Greek nation. In the second main part, Josephus turned to the anti-Jewish clichés of individual ancient authors. A positive representation of the Jewish constitution (2.145–286) is inserted, in which the voices of the critics have meanwhile been forgotten. Thematically, this part touches on the representation of the Mosaic Law in antiquities , but in Contra Apionem the Jewish community is understood less politically than philosophically. Josephus coined the term theocracy for this :

“Some left monarchies, others less to rule, while others left power in the community to the multitudes. Our legislature, on the other hand, [...] - as one could say with an idiosyncratic expression - designed the community as a theocracy in which he assigned rule and power to God. "

Josephus understood theocracy differently from today's usage: a state in which political power lies with the clergy . “In the theocracy intended by Josephus, on the other hand, God exercises his rule 'directly'.” This community is a literary greatness, designed by Josephus with a view to a Roman audience and populated with “ toga- wearing Jews” (John MG Barclay), the orientate themselves on actually ancient Roman values: love for country life, loyalty to traditional laws, piety towards the dead, restrictive sexual morality.

The subject of the ban on images shows how carefully Josephus chose his words . The other side had criticized the fact that Jews did not put up statues in their synagogues for the emperors. Josephus admitted: “Well, Greeks and some others think it is good to put up pictures.” Moses forbade the Jews to do this. The typical Roman setting up of statues is secretly becoming the custom of "Greeks and a few others". In Contra Apionem the author repeatedly plays with a “Greek” stereotype: talkative, inconsistent, unpredictable and therefore contrary to legal thought and dignity, Roman values (cf. Cicero's rhetorical strategy in Pro Flacco ). Other honors for the emperors and the people of the Romans are permitted, especially the sacrifices for the emperor. Josephus ignored the fact that the temple had not existed for a good 20 years. He counterfactually asserted that sacrifices were made there daily for the emperor at the expense of all Jews.

In preparation for Contra Apionem , Josephus had apparently studied the works of Jewish authors from Alexandria intensively. He also gave his late work stylistic brilliance and a new, fresh vocabulary (numerous Hapax legomena ), which is striking in comparison with the simple Vita written shortly before.

Impact history

Roman readers

“Of the Jews of that time, Josephus enjoyed by far the greatest respect, not only among his compatriots, but also with the Romans. He was even honored in Rome by setting up a statue, and the writings he wrote were honored for inclusion in the library. "

If this statement by Eusebius of Caesarea can be used historically at all, then Josephus was more likely to be known to Vespasian for the prophecy of the empire than as an author. There are few traces of a contemporary pagan reception of his work. Occasional similarities between the Jewish War and the Histories of Tacitus can also be explained by the fact that both authors accessed the same sources. The Neo-Platonist Porphyrios quoted individual passages from Bellum in his work “On abstaining from the ensouled”. The speeches of Libanios (4th century) may also show knowledge of Josephus' works.

Christian readers

Josephus' works were frequently used by authors of the early church and have probably only now, increasingly since the 3rd century, gained greater prominence. The following reasons can be given for the popularity of his writings with Christians:

- He was the only non-Christian contemporary author to mention Jesus of Nazareth ( Testimonium Flavianum ).

- His account of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple could be read as the fulfillment of a prophecy of Jesus. A text like Lk 19,43-44 EU is considered by many historical-critical exegetes as a Vaticinium ex eventu : An original eschatological threatening word of Jesus of Nazareth was reshaped under the impression of the war events. It was a different story for ancient and medieval theologians. With the Bellum in hand, it was possible to prove that Jesus' words had literally been fulfilled. This argument can be found in authors as diverse as Eusebius of Caesarea , Walahfrid Strabo , Johannes von Salisbury , Jacobus de Voragine or Eike von Repgow and many later.

- In the history of its impact, the Testimonium Flavianum was “overshadowed by a large-scale reinterpretation that can only be described as pseudo-historical,” says Heinz Schreckenberg : the assertion of a causal connection between the crucifixion of Jesus and the destruction of Jerusalem. Origen accused Josephus of covering up why Jerusalem was really destroyed: as divine punishment of the Jews for rejecting Jesus Christ. In ever new rhetorical variants, authors of the early church took up the motif of collective punishment , for example John Chrysostom , who claimed that Christ himself destroyed Jerusalem and scattered the survivors into all countries. They now roam about as refugees, “hated by all people, despicable, abandoned to all, to suffer bad things from them. So it is right!"

- His work contained a great deal of useful information about the New Testament environment. An example: For the Christian reader, Josephus' description of Galilee and in particular the almost paradisiacal landscape on the Sea of Galilee set the stage for the work of Jesus and his disciples. This description of the landscape ( ekphrasis ) in Bellum contrasts with the bloodbath that the Roman army will soon wreak there.

- Eusebius of Caesarea found in Contra Apionem both arguments against pagan religions and reasons for the superiority of Christianity over Judaism. With his late work, Josephus provided language assistance for the newly forming Christian apologetics .

- Josephus had related Roman and Jewish history to one another. Medieval readers found it very appealing to be able to combine the Bible and antiquity into one overall picture. The positive portrayal of Roman actors in Josephus resulted in a positive view of pagan, pre-Constantine Rome, which could be seen as proto-Christian. The Roman emperors who went to Jerusalem to carry out a criminal court were the crusaders' identification figures. This idea becomes explicit in the crusade encyclical attributed to Pope Sergius IV , which promised the fighters against the Muslims the same remission of sins that Vespasian and Titus would have obtained through the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70. This text was probably not written until the time of the First Crusade (1096-1099) in the Abbey of Saint-Pierre (Moissac) . It is hardly surprising that chroniclers of the Crusades such as Fulcher of Chartres and Wilhelm of Tire kept referring to Josephus, often in connection with the topography of the Holy Land.

- When Dominicans and Franciscans gathered arguments to refute the Talmud in the 13th century , Josephus became a key witness. He represented z. For Raymund Martini , for example, a proto-Talmudic, “correct” Judaism could be invoked to portray contemporary Jewish religious practice as “wrong” - in the final analysis, Josephus thus provided reasons for burning the Talmud .

The way in which the work of Josephus was dealt with corresponded to the ambivalent attitude of Christian authors towards Judaism as a whole, which on the one hand was claimed as part of their own tradition and on the other was rejected. Unlike Philo of Alexandria , Josephus was not declared a Christian because his testimony about Jesus and the early church had more value if it was the vote of a non-Christian. Nevertheless, Hieronymus introduced Josephus like a church writer in his Christian literary history (De viris illustribus) , and medieval library catalogs also classified the works of Josephus with the church fathers. In the modern edition of Latin church writers, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum , Volume 37 was intended for the Latin translation of Josephus; of this, only the volume 37.6 appeared with the text of the Contra Apionem .

Latin poetry and translation

The reception of Josephus in Latin was twofold: a free paraphrase of Bellum ( pseudo-Hegesippus ) was created as early as the 4th century . This work interprets the destruction of Jerusalem as a divine judgment on the Jewish people. There are certainly passages in the Bellum where Josephus interprets the events of the war in this way, but Pseudo-Hegesippus emphasized this idea more strongly and, according to Albert H. Bell's analysis, is less of a Josephus adaptation than an independent work of history. The actual translations into Latin, which are available for the three larger works, but not for the Vita, are somewhat more recent . The first thing to do was to translate the Bellum . The translations of Antiquitates and Contra Apionem followed, they were started in Cassiodor's monastery and completed in the middle of the 6th century.

Awareness of Josephus' work

There are 133 wholly or partially extant manuscripts of Josephus' works; the oldest are from the 9th / 10th centuries. Century. Entries in book directories and quotations in Florilegien also show how widespread reading Josephus was in the Middle Ages. Typically, the Testimonium Flavianum was particularly emphasized in the text, for example with red ink . Josephus was a widely read author, given that only a small portion of Christians could read.

Peter Burke has examined the reception of ancient historians since the advent of the printing press on the basis of the number of copies their works achieved. For Josephus' Bellum and Antiquitates the following picture emerges: All Latin authors (except Eutropius ) had higher editions than the Greek ones; in the Greek editions Josephus took the first two places. In the middle of the 16th century, Bellum and antiques reached their greatest popularity. Josephus' works were also read much more often in vernacular translations than in Greek or Latin versions.

After the Council of Trent , Bible translations in the Roman Catholic area from 1559 required the approval of the Holy Office of the Inquisition . After that, Italian editions of Josephus found very good sales on the Venetian book market. They were evidently a kind of Bible substitute for many readers. In the 1590s, retelling of the biblical story was also included on the index , but not the works of Josephus himself - at least not in Italy. The Spanish Inquisition was stricter and banned the Spanish translation of antiquities from 1559 onwards. This work appeared to the censor as a Rewritten Bible , while the Bellum remained a reading permitted in Spain.

The Josephus translation by William Whiston , which has been reprinted again and again since its publication in 1737, developed into a classic in the English-speaking world. In strict Protestant circles, Whiston's Josephus translation was the only Sunday reading allowed besides the Bible. This shows how strongly it was received as a biblical commentary and bridge between the Old and New Testaments.

Josephus' works as a commentary on the Bible

Hrabanus Maurus quoted Josephus frequently, both directly and through Eusebius of Caesarea and Beda Venerabilis ; his biblical interpretation is a major source for the great standard commentary of the Glossa Ordinaria. Typical of the Christian reception of Josephus in the early Middle Ages is that, in addition to reading his works, the handing down of his subject matter appears in compendia: Josephus from second or third hand. Josephus' descriptions formed the image that was made of, for example, Solomon , Alexander the Great or Herod , and that he interpreted biblical persons in a Hellenistic way as bringing culture, entered textbooks and thus became common knowledge. Among other things, Walahfrid Strabo has the motif that 30 Jews were sold into slavery for a denarius, corresponding to the 30 pieces of silver that Judas Iscariot received for his betrayal ( Talion punishment ). Josephus mentions the enslavement of the survivors several times, but does not write that 30 people were worth only one denarius: an example of the free use of the Josephus text in the early Middle Ages.

After Josephus in 10/11. While there was less read in the 19th century, interest in his work increased by leaps and bounds in north-western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. Most of the Josephus manuscripts date from this period, some of them preciously illuminated. Apparently Josephus' works were considered indispensable in a good library. As book owners, people often come across people who were involved in teaching schools, especially in Paris. Andreas von St. Viktor and Petrus Comestor , two 12th century Victorians , made frequent use of the works of Josephus. In an effort to comprehensively shed light on the literal meaning of the Bible text, they followed the school's founder, Hugo von St. Viktor . The intensive reading of Josephus was accompanied by studies of Hebrew and the evaluation of other ancient Jewish and patristic texts. Comestor's Historia Scholastica , which Josephus quoted extensively, became the standard textbook for first-year students. Folk language translations or adaptations also conveyed the content to interested laypeople.

In addition to Josephus, biblical studies today use many other ancient texts; Since the end of the 20th century, knowledge of ancient Judaism has been considerably enhanced by the Dead Sea Scrolls . Martin Hengel summed up the lasting importance of Josephus for New Testament exegesis as follows:

“Our main source is Josephus, our knowledge would shrink in ways that are difficult to imagine if his work had not been preserved. The historical framework of the New Testament lost all contours and evaporated to a mere shadow that no longer made possible a historical classification of early Christianity. "

Jewish readers

Rabbinical literature ignored the person and work of Josephus. But that is nothing special, because other Jewish authors who write in Greek have not been read either. The Talmud tells the legend that Jochanan ben Zakkai prophesied the empire to the general Vespasian (Gittin 56a – b), which both Abraham Schalit and Anthony J. Saldarini used to compare Josephus and Jochanan ben Zakkai.

Sefer Josippon - a Hebrew adaptation

It was only in the early Middle Ages that there was evidence of a Jewish reception of Josephus' work. In the 10th century someone in southern Italy, under the name of Joseph ben Gorion , wrote an eclectic history of Judaism in Hebrew from the Babylonian exile to the fall of Masada . This work is known as Josippon . He used several Latin sources, including Pseudo-Hegesippus . He edited the text in the following way:

- All Christian interpretations of the events of the war were either left out or reformulated.

- The cause of the destruction of the temple is not the crucifixion of Jesus, but the bloodshed in the temple area.

- The author of Josippon omitted the entire chapter that mentions John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth.

Several Bible commentators used the Josippon, while direct access to the work of Josephus cannot be proven with them: Rashi , Saadja Gaon , Josef Kaspi , Abraham ibn Esra . The Josippon was widely read in Jewish communities throughout the Mediterranean, which in turn was noticed by the Christian community. Here the Josippon was partly considered to be the first work mentioned by Josephus and was therefore translated into Latin. The Italian humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola tried to read the Josippon in Hebrew because of its supposedly high source value. Isaak Abrabanel , the Spanish-Jewish scholar, mostly quoted Josippon in his work, but occasionally also Josephus himself (based on the Latin translation); thus he is unique among the Jewish Bible commentators of the Middle Ages. Abrabanel's work, in turn, was studied by Christian scholars and was included, for example, in the commentaries on the English translation of Josephus by William Whiston (1737).

Discovery of Josephus' work in the 16th century

Azaria dei Rossi read Josephus' works in Latin translation and made them accessible as a source for ancient Jewish history ( Meʾor ʿEnajim , 1573–1575). From then on, Jewish scholars also had access to Josephus and not just to post-poetry.

In 1577 a Hebrew translation of Contra Apionem , the work of an otherwise unknown doctor of Iberian origin named Samuel Schullam , was published in Constantinople . This ancient apology of Judaism seems to have appealed to Schullam very much; he translated the Latin text freely and in an updated manner. That Josephus z. B. said that the non-Jewish peoples had learned to keep the Sabbath, fasting, lighting lamps and the commandments of food from their Jewish neighbors, made no sense for Schullam: this way of life differentiated Jews from their environment.

David de Pomis published an apology in Venice in 1588, which was based heavily on Josephus' Antiquitates : If non-Jewish rulers in antiquity had shown benevolence to the Jewish community and treated it fairly, as he found many examples in Josephus, then Christian authorities could that is all the more likely. De Pomis' work was put on the index , which prevented its reception for centuries.

Haskala, Zionism and the State of Israel

Negative judgments about the personality of Josephus are the rule among Jewish and Christian historians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Heinrich Graetz and Richard Laqueur are among those who simply considered Josephus a traitor . Haskala authors such as Moshe Leib Lilienblum and Isaak Bär Levinsohn saw Josephus with his Jewish-Roman identity as a role model, while at the same time sympathizing with the Zealots . Joseph Klausner's judgment is unusual : he identified himself with the Zealots and saw parallels between their struggle for independence and the contemporary struggle against the British mandate government. Nevertheless, he accepted Josephus' move to the Roman camp, because he was a scholar and not a fighter and had subordinated everything to his mission as a historian to record events for posterity.

Between the 1920s and 1970s, Josephus trials were part of the program of Zionist educational work as improvisational theater . It was quite open how the matter ended for "Josephus". Shlomo Avineri described such an event by the Herzlija local group of the socialist youth organization No'ar ha-Oved , at which there were two accused: Josephus and Jochanan ben Zakkai - both of whom had left the resistance fighters' camp. After intensive negotiations, both were acquitted: Josephus for his historical works and Jochanan ben Zakkai for his services to the survival of the Jewish people after the defeat.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls led to a reassessment of Josephus in Israel in the 1950s and 1960s. Daniel R. Schwartz justifies this as follows: “The roles - originating from the soil of Palestine just at the time of the Israeli declaration of independence - were useful in the Zionist argument as evidence that Jewish claims to Palestine were legitimate, [...] but these texts gained importance only through the explanation and context provided by Josephus. So it was difficult to continue to condemn and revile him. ”The excavations in Masada under the direction of Yigael Yadin , which received a lot of public attention , were also interpreted and prepared in popular science with massive recourse to the Bellum . "The touching story of the end of Masada, told by the deeply ambivalent Josephus, became Israel's most powerful symbol and an indispensable national myth." (Tessa Rajak)

The social climate in Israel has changed since the 1973 Yom Kippur War . According to Schwartz, the patriotism of the early years gave way to a more pragmatic view of military ventures. An ancient Jew who considered a fight against Rome to be hopeless could be considered a realist in the 1980s. When Abraham Schalit expressed himself in this sense in the early 1970s, it was still a single voice.

Josephus in Art and Literature

Images of Josephus

The classic author's image of the modern Josephus prints can be found in William Whiston's English translation of the Antiquitates (1737). Josephus, an aristocratic-looking old man with a white beard, is marked as an Oriental with a pseudo-Turkish turban with jewels and a feather. Later editions of Josephus vary the headgear.

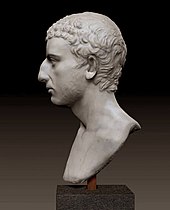

In 1891 the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen acquired the very well-preserved marble bust of a young man, a work of Roman antiquity. The provenance could not be clarified, much less the identity of the person depicted. Nevertheless, Frederik Poulsen declared in his museum catalog published in 1925 that the sitter was "undoubtedly a young Jew." Robert Eisler identified him in 1930 with Josephus and referred to Eusebius of Caesarea , who had written that Josephus had been honored in Rome by erecting a statue. Eisler, cultural historian of Jewish origin, argued with classic anti-Semitic stereotypes in that he recognized “Jewish” eyes in the depicted ancient person, but above all an un-Roman shape of the nose.

Josephus in literature

Josephus' work contributed numerous individual features to the representation of biblical subjects in world literature. The well-received, non-biblical stories of Herod and Mariamne I as well as Titus and Berenike are specifically Josephine .

Mystery games

In the Middle Ages , the bellum was received in vernacular mystery games , which interpreted the Jewish War as a deserved judgment for the crucifixion of Jesus . An example is Eustache Marcadés La Vengeance de Nostre Seigneur Jhesu Crist . Here Josephus appears unusually as a military leader; other Vengeance games give him the role of a doctor or magician. The plot of these games is often as follows: A ruling figure is attacked by a puzzling disease and can only be cured by executing God's punishment on the Jews. Vengeance games were staged with great effort across Europe . The motive of the doctor Josephus entered the Sachsenspiegel and established the royal protection of Jews there: "A Jew called Josephus achieved this peace with King Vespasian when he cured his son Titus of the gout ."

Historical novels

The Josephus trilogy (1932–1942) Lion Feuchtwanger is the most important literary examination of the personality of Josephus. The author traces the path of the protagonist from Jewish nationalist to cosmopolitan . His Josephus is enthusiastic about the biblical book Ecclesiastes and would like to bring up his son in such a way that he represents “the perfect mixture of Greek and Judaism”. But Domitian ensures that Josephus' son dies in a fictitious accident. Josephus then returns to Judea. There he dies:

“This Josef Ben Matthias, priest of the first row, known to the world as Flavius Josephus, was now lying on the embankment, his face and white beard soiled with blood, dust, feces and saliva, breathing away. […] The whole country was filled with his twilight life, and he was one with the country. […] He had searched the world, but had only found his country; because he had searched the world too early. "

In his novel "The Source" ( The Source , 1965), the American bestselling author James A. Michener tells the story of the fictional city of Makor in Galilee in 15 episodes. In one episode, Josephus, "the best soldier the Jews ever had" (p. 436) leads the defense of Makor, flees, goes to Jotapata, saves himself with forty survivors, manipulates the straws that determine the order of the killings, so that he is the last to be left and saves his life by predicting the imperial dignity of Vespasian and Titus. He thus becomes “a traitor to Galilea's Jews” (p. 463).

Dramas

In Friedrich Schiller's drama Die Räuber (1782) there is the following tavern talk (1st act, 2nd scene): Karl Moor looks up from his reading: "I am disgusted with this inkblot-end seculum when I read about great people in my Plutarch ." Moritz Spiegelberg replied: “You have to read Josephus. [...] Read Josephus, I ask you to do so. ”Reading the“ robber ”stories in the Bellum is here preparation for founding a band of robbers. Since Schiller does not explain this allusion, an audience is assumed that is familiar with the Bellum . Alfred Bassermann suspected that Schiller had found “the idea of a great robber life and at the same time the contrast between the two robber types, Spiegelbergs and Moors” in the Bellum .

Several dramas emerged in the 20th century that dealt with the personality of Josephus and his role in the Jewish War, which corresponds to the importance of this topic in Zionism.

Jitzchak Katzenelson wrote the Yiddish drama "Near Jerusalem" (ארום ירושלים Arum Yerushalayim ) in the Warsaw ghetto in 1941 . Katzenelson was actually a Hebraist; a Hebrew work "With the Shepherds: A Night in the Area of Jerusalem" (1931) was translated into Yiddish by him and updated to reflect the ghetto situation. Along with other figures in Jewish history, Josephus is conjured up by a medium and asked by Zionist pioneers ( Chalutzim ): How should his political actions be judged, and what do his writings mean for Judaism? Josephus appears as a fully assimilated Jew who has forgotten his name and his priestly origins. The ghetto situation is discussed several times: the obligation to testify to what happened for posterity, the nature of betrayal and the justification of the traitor, the importance of the rebel movement and the attempted uprising. Katzenelson respectfully referred to the works of Josephus as Sforim (Yiddish: holy books), which belonged to the canon of Jewish literature. It is not known whether the planned performance took place as a Purim play.

Nathan Bistritzky-Agmon's Hebrew drama "Jerusalem and Rome" (ירושלים ורומי Yerushalayim veRomi ) was published as a book in 1939 and premiered in 1941 by the Habimah Theater. Here Josephus advocates the reconciliation of East and West; he asks Jochanan ben Zakkai to return to Jerusalem and stop the Zealots. Fanatics are in power in both Rome and Jerusalem. Feuchtwanger's influence can be seen in the portrayal of Josephus. Shin Shalom published in 1956 in the collection " Ba-metaus hagavoah , nine stories and a drama" (במתח הגבוה, תשעה סיפורים ומחזה) a Hebrew drama about Josephus' change of page in Jotapata, "The Cave of Josephus". This is also a revised version of a work published under the same title as early as 1934/35.

Individual topics of Josephus research

Text research

The only surviving papyrus fragment with the Josephus text, Papyrus Vindobonensis Graecus 29810 (late 3rd century AD), clearly illustrates that the difference between the medieval manuscripts and the original text by Josephus is considerable: the fragment in the Austrian National Library comes from an edition of the Bellum and contains 112 words in whole or in part; This text differs nine times from all the manuscripts that Benedikt Niese had available for his scientific text edition. Of the four works by Josephus , the Bellum has come down best in comparison.

Niese procured the edition of the Greek Josephus text, which is still relevant today, an edition with an extensive text-critical apparatus (Editio maior, 7 volumes, 1885–1895) and an in many cases deviating edition with a tighter apparatus (Editio minor, 6 volumes, 1888–1895 ), which is considered to be his final edition. Since then, around 50 manuscripts have become known that Niese was not yet able to use. In several European countries translations or bilingual editions were made that made changes to Niese's text. If this trend continues, it will be unclear which Greek text experts will refer to in their publications. Heinz Schreckenberg therefore considers the creation of a new, large critical text edition to be urgently necessary, but at least a revision of Niese's work. Until then, according to Tommaso Leoni, Niese's Editio maior will, in spite of everything, offer the relatively best text of the Bellum , but this is sometimes hidden in the critical apparatus.

The corruption of the text in the antiquities is partly a result of the fact that medieval copyists approximated Josephus' Bible retelling to the Greek text of the Septuagint . A French team led by Étienne Nodet has been developing a new manuscript stemma for books 1 to 10 of the Antiquitates since 1992 , with the result that two manuscripts from the 11th century that Niese considered less important seem to offer the best text :

- Codex Vindobonensis historicus Graecus 20 (in Niese: "historicus Graecus No. 2"), Austrian National Library;

- Codex Parisinus Graecus 1419, French National Library .

The Münster edition of the Vita offers a mixed text that differs from Niese's Editio maior in that the Codex Bononiensis Graecus 3548, which is in the University Library of Bologna, has been incorporated. Although relatively late (14th / 15th century), it is classified as a witness of the best tradition.

Contra Apionem is the worst preserved work by Josephus. All Greek witnesses, including the indirect ones, are dependent on a codex in which several pages are missing; this large gap in the text must be filled in with the help of the Latin translation. Niese assumed that all of the more recent Greek manuscripts were copies of the Codex Laurentianus 69:22 from the 11th century. The translation team from Münster ( Folker Siegert , Heinz Schreckenberg , Manuel Vogel), on the other hand, rates the Codex Schleusingensis graecus 1 (15th / 16th century, library of the Henneberg School , Schleusingen ) as evidence of a partially independent tradition. Arnoldus Arlenius had used this codex for the first edition of the Greek Josephus text printed in 1544. The readings of this print edition that differ from Laurentianus are given greater weight as a result; until then they were considered to be the conjectures of Arlenius.

Archeology in Israel / Palestine

Since the middle of the 19th century, Palestine researchers have been looking for ancient sites or buildings "with Josephus in one hand and the spade in the other" - a success story that has continued into the present, according to Jürgen Zangenberg . But it is methodologically questionable. "Every interpretation, especially the supposedly only 'factual' passages, has to begin ... with the fact that Josephus is first and foremost an ancient historian."

Just as Yigael Yadin harmonized the excavation findings of Masada with the report of Josephus, the excavator of Gamla , Shmarya Guttman , found the report of the Roman conquest of this fortress in the Golan confirmed in many details. According to Benjamin Mazar , the findings of the Israeli excavations along the southern and western enclosing wall of the Temple Mount since 1968 illustrate construction details of the Herodian Temple , which are described in the Bellum and the Antiquities . More recent examples that archaeological findings are interpreted with the help of Josephus' information are the excavations in Jotapata (Mordechai Aviam, 1992–1994) and the identification of a palace and a hippodrome in Tiberias ( Yizhar Hirschfeld , Katharina Galor 2005).

The "credibility" of Josephus was discussed several times in research. On the one hand, the archaeological evidence often confirms the statements made by Josephus, or at least can be interpreted that way. On the other hand, there are examples where Josephus makes blatantly false information about distances, dimensions of buildings or population sizes. This is partly explained by copyist errors. A well-known and difficult problem in research are Josephus' descriptions of the Third Wall, i.e. H. the outer northern city fortifications of Jerusalem. Michael Avi-Yonah characterized it as a jumble of impossible distances, disparate descriptions of the same events, and a chaotic use of Greek technical vocabulary. Kenneth Atkinson worked out contradictions between the excavation results in Gamla and Masada and the description of the war in Bellum . One must assume that the Roman capture took place historically differently from that represented by Josephus. For example, due to the conditions on the mountain top, it is not even possible that 9,000 defenders fell from there when the Roman army penetrated Gamla and thus committed collective suicide. Gamla was also weakly fortified and offered little resistance to Vespasian's army. Shaye Cohen had previously questioned the combination of archaeological findings and Josephus' account of the end of Masada.

Postcolonial reading

Homi K. Bhabha has the post-colonialism developed by the thesis that colonists and colonized complex forms of interaction develop. The rulers expect the underdogs to imitate their culture. They do that too - but not properly, not completely. A basic contradiction of colonialism is that it wants to educate and civilize the colonized, but maintains a permanent difference to them: In other words, natives can become Anglicized but never English .

The colonized can use the dominant culture in a creative way for self-assertion (resistant adaption) . This approach makes it possible to read Josephus' work beyond the alternatives of Flavian Propaganda and Jewish Apologetics: Josephus and other historians with roots in the east of the empire tried “to tell their own story in an idiom that the majority culture (s) understood ), but primarily with reference to their own traditions - and for their own purposes ”.

An example from Bellum : Herod Agrippa II tries to dissuade the Jerusalemites from war against Rome by stating, in the style of imperial propaganda, that Rome ruled the whole world. His speech lets the well-known peoples of antiquity fille past with their respective special abilities; Rome defeated them all (mimicry of a gentes devictae list). Agrippa (or Josephus) does not attribute this to Jupiter's favor, but to the god of the inferior Jews. In this way, according to David A. Kaden, he destabilizes the dominant imperial discourse. It is no longer quite clear whether a Jew or a Roman is speaking. Bhabha uses the term in-between-ness to describe the situation of cultural cross-border commuters . When Josephus describes how he himself gave a speech to the defenders in their mother tongue on behalf of the Romans in front of the wall of besieged Jerusalem, he embodies in-between-ness in his own person.

Work editions

- Flavii Josephi opera edidit et apparato critico instruxit Benedictus Niese. Weidmann, 7 volumes, Berlin 1885–1895.

The best German translations or Greek-German editions are listed below. For further editions see the main articles Jewish War , Jewish Antiquities and About the Originality of Judaism . Niese introduced the book / paragraph counting that is common in literature today, while editions of works based on an older Greek text have a book / chapter / section count (e.g. Whiston's English and Clementz's German translation). The digital version of the Niese text in the Perseus Collection can be used for conversion.

- De bello Judaico - The Jewish War . Greek-German, edited and with an introduction and annotations by Otto Michel and Otto Bauernfeind . wbg academic, 3 volumes, special edition (2nd, unchanged edition) Darmstadt 2013. ISBN 978-3-534-25008-0 .

- Jewish antiquities . Translated and provided with an introduction and notes by Heinrich Clementz, Halle 1900. Volume 1 ( digitized version ) Volume 2 ( digitized version ). This translation has considerable flaws: it is based on the Greek text editions by Dindorf (1865) and Haverkamp (1726), which were already obsolete when Clementz's translation appeared; In addition, Clementz translated imprecisely, sometimes paraphrasing. After the Münster translation project was canceled, a new translation of the antiquities into German is not to be expected for the time being. At least a pre-translation of Ant 1,1–2,200 is available online: PDF .

- From my life (Vita) . Critical edition, translation and commentary ed. by Folker Siegert, Heinz Schreckenberg, Manuel Vogel. Mohr Siebeck, 2nd, revised edition Tübingen 2011. ISBN 978-3-16-147407-1 .

- About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem) . German / Ancient Greek, ed. by Folker Siegert. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008. ISBN 978-3-525-54206-4 . (Volume 1: digitized material ; Volume 2: digitized material )

literature

Aids

- A complete concordance to Flavius Josephus . Edited by Karl Heinrich Rengstorf and Abraham Schalit . Brill, Leiden 1968-1983. - Volume 1: Α - Δ. 1973; Volume 2: Ε – Κ. 1975; Volume 3: Λ – Π. 1979; Volume 4: Ρ – Ω. 1983. Supplementary volume : Dictionary of names for Flavius Josephus . Edited by Abraham Schalit, 1968.

- Heinz Schreckenberg : Bibliography on Flavius Josephus (= work on the literature and history of Hellenistic Judaism. Volume 14). Brill, Leiden 1979, ISBN 90-04-05968-7 .

Overview representations

- René Bloch: Iosephos Flavios (Flavius Josephus). Bellum iudaicum. In: Christine Walde (Ed.): The reception of ancient literature. Kulturhistorisches Werklexikon (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 7). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2010, ISBN 978-3-476-02034-5 , Sp. 397-406.

- Heinz Schreckenberg: Josephus (Flavius Josephus). In: Reallexikon für antiquity and Christianity . Volume 18. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1998, Col. 761-801.

- Irina Wandrey: Iosephos (4) I. Flavios. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 5, Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-01475-4 , Sp. 1089-1091.