Columbine High School rampage

|

|

This article is about suicide. For those at risk, there is a wide network of offers of help in which ways out are shown. In acute emergencies, the telephone counseling and the European emergency number 112 can be reached continuously and free of charge. After an initial crisis intervention , qualified referrals can be made to suitable counseling centers on request. |

Location of Littleton, Colorado, in the United States |

The Columbine High School rampage , also known as the Littleton School Massacre , occurred on April 20, 1999 at Columbine High School in Columbine , a suburb of Denver , Colorado near Littleton . In the rampage , two high school students shot and killed twelve students between the ages of 14 and 18, a teacher and themselves within less than an hour. Another 24 people were injured, some seriously. On the occasion of the 20th anniversary in 2019, many of the survivors said they were still suffering from the aftermath of the event.

The perpetrators - 18-year-old Eric Harris and 17-year-old Dylan Klebold - had been preparing the mass murder for months and planned not as a rampage but as a bomb attack on their school, in which several hundred people were to die. Due to a technical error, the bombs they placed in the school cafeteria for this purpose did not explode, which is why they spontaneously changed their plan and began shooting at their classmates.

Their motives could not be clarified with certainty. While the rampage was often categorized by the media as an act of revenge for bullying suffered at school , the investigative authorities, after analyzing the diaries and video recordings left by the perpetrators, assumed that their primary aim was to become famous. Individual experts also suspect a political or ideological motivation. Both perpetrators were diagnosed with severe psychological disorders post mortem .

It was not the first school rampage in the United States, but the massive media coverage made the case a worldwide sensation for the first time. The act sparked numerous public debates about possible causes and complicity, with bullying, psychotropic drugs , the responsibility of parents and teachers, subcultures , the influence of the music industry and fictional violence on young people as well as the US gun law, which is often criticized as too liberal, being discussed . In response to the incident, many schools increased their security and US police changed their tactics in intervening in rampage.

The fact is considered to be a turning point in the culture of the United States because of its far-reaching consequences and is counted among the most important historical events of the 1990s , especially by generations X and Y. The rampage at Columbine High School has become the archetype of the school shoot . The worldwide increase in school shootings after the crime is often referred to as the "Columbine Effect" because many of the later gunmen named the Littleton school massacre as an inspiration for their own crime. In the United States, students born after April 20, 1999 are referred to as the "Columbine Generation," who have never seen a world without school shoots .

prehistory

Biographies of the perpetrators

Childhood and family background

Eric David Harris was born in Wichita , Kansas , on April 9, 1981, the younger of two sons of Colorado-born couple Wayne and Katherine Harris . Due to the father's job, who was a transport pilot with the US Air Force , the family moved several times within the USA and lived in Beavercreek, Ohio , and Oscoda, Michigan , as well as in Plattsburgh , New York . Harris found the frequent moves and the associated school changes stressful, as he had to build up a new circle of friends every time. In 1993 the family finally settled permanently in Littleton, where Wayne Harris worked for an aviation security company after retiring from the military and Katherine Harris found employment with a catering company. As a child, Harris played soccer and baseball in the Little League . At the age of 12 he had an operation to correct a congenital chest deformity . In retrospect, childhood friends described him as a smart, shy, respectful, and normal boy who "didn't seem to be what the media portrayed him [after the killing spree]."

Dylan Bennet Klebold was born on September 11, 1981 in Lakewood , Colorado, grew up in Littleton and, like Harris, had a brother three years older than him. His father, Thomas Klebold, a geophysicist , worked as a consultant for oil companies and as an independent mortgage administrator. His mother Sue Klebold comes from a Jewish family in Columbus , Ohio, and worked at Colorado Community College to help people with disabilities integrate into the labor market. The family belonged to the Lutheran Church , but also cultivated Jewish traditions. Klebold was considered highly intelligent , showed an extraordinary talent for mathematics and started school one year early. At Elementary School , he took part in a program for particularly talented children. He also played soccer and was a pitcher in the Little League. His parents did not tolerate weapons in their household. Contemporaries described him as a very shy, meek boy with low self-esteem, easily humiliated and difficult to lose.

Youth and school time together

Harris and Klebold met in 1993 at Ken Caryl Middle School and became close friends. In their spare time, they often enjoyed computers, the Internet, and video games. From 1995 they attended Columbine High School in the Jefferson County School District . In the school's social hierarchy, they were at the lowest level, but contrary to original media reports they were not loners, but had a comparatively large circle of friends, which consisted mainly of nerds and computer geeks. Both of the perpetrators had no boyfriend and on their records they expressed frustration at their unrequited feelings for different girls. While Klebold was too shy to approach girls, Harris was often turned away.

According to several witnesses, both perpetrators were often bullied by the more socially successful students - so-called jocks - and were attacked both verbally and physically. For example, classmates reported several incidents in which Harris and Klebold were pelted with glass bottles or food, or insulted as " fagots ". Klee told his father that he was over 1.90 m tall and that he was not pushed around, but that Harris was often harassed. According to other witness statements, both perpetrators intimidated other students themselves and provoked conflicts with aggressive or provocative behavior. In December 1998, Harris and Klebold made a fictional short film called Hitmen for Hire as part of their video course , in which they play contract killers who shoot the torturer of a victim of bullying and blow up a school. Excerpts of the video were broadcast nationwide by US broadcaster Fox News after the rampage .

In addition to teaching, both perpetrators were involved in the school station and assisted in looking after the school's computer network; Klebold also took care of the sound engineering for performances by the theater group. While Harris was considered a good student to the end, Klebold's academic performance deteriorated over time and his teachers noticed that he slept more often in class. In December 1997, Harris wrote a school essay on "Guns in Schools," referring to several school shootings that had occurred in the United States in the previous weeks. As a solution to the problem, he suggested metal detectors and increased police presence. Klebold submitted an essay in February 1999 about a man like him who shoots jocks . His teacher was disturbed by the violent story, which is why she sought a conversation with his parents. They agreed to consult a school counselor, who warned Klebold but did not take any further action.

| School yearbook photo by Eric Harris |

|---|

|

Link to the picture |

| School yearbook photo by Dylan Klebold |

|---|

|

Link to the picture |

The rampage took place just a few days before she was due to graduate from school. Both perpetrators had already commented on future plans. Klebold had been accepted for a computer science course at the University of Arizona and had visited the campus with his parents in late March 1999; Harris had applied to the Marines and had already passed the written entrance exam with above-average results. However, his application was turned down shortly before the rampage after the recruiter learned that Harris was taking an antidepressant to treat depression . Harris is said to have reacted disappointed but not dejected to the rejection. On April 17, 1999 - three days before the rampage - Klebold went to the prom with several friends , where they saw him in a good mood and he insisted on staying in touch after graduating from school. Harris joined the after-prom party where they partied with their classmates until the wee hours of the morning.

First offenses

Starting in January 1997, Harris and Klebold went on several nightly forays in which they vandalized the houses and other property of people they did not like . They were neither caught nor noticed by their parents sneaking out of the house for hours at night. In September 1997, Harris, Klebold, and a friend of the two hacked into Columbine High School's computer system to get a list of the combination locks on the student lockers . After they opened some lockers, the school administration found out about them and they were banned from class for several days. A few months later, Klebold was temporarily suspended again for deliberately damaging a classmate's locker. The teacher punishing him later recalled that Klebold had reacted angrily to his renewed suspension and that he had been annoyed about the school system and the unequal treatment of students.

Harris ran a blog- like AOL website, on which he wrote from the beginning of 1997 about his increasing hatred of his fellow human beings and society, reported about his first successes in building explosive devices and made death threats against classmates. People at risk included Brooks Brown, a friend of both perpetrators with whom Harris had temporarily fallen out. In February 1998, a self-made pipe bomb was found in Harris' neighborhood, the maker of which the police could not determine. The following month, Brown was referred to Harris' website by Klebold, and Brown's parents called the police. This checked the website and worked out - also in the light of the bombing - an application for a judicial search warrant for Harris 'parents' house. However, the request was forgotten as the officer in charge was assigned other duties, leaving Harris unmolested. After the rampage, senior Jefferson County Sheriff's Office officials decided in a secret meeting with the district attorney to conceal the application. In April 2001, however, its publication was finally ordered by the court after investigative journalists learned of the Browns 'complaint and, together with victims' relatives, sued for access to the files. The failure to follow up and the non-disclosure of the application did not result in any legal consequences for the officers. Harris' Internet entries had been removed by AOL and given to the FBI shortly after the rampage .

On January 30, 1998, Harris and Klebold broke into a van from which they stole electrical appliances. They were picked up by a police patrol and arrested with the stolen property near the scene of the crime. In return for her admission of guilt, the imposition of a prison sentence was waived. Instead, on March 25, 1998, they were required to participate in a twelve-month program for first-time juvenile offenders (Diversion Program) , during which they were required to do community service, attend counseling sessions, and undergo anti-aggressiveness training . They showed themselves to be insightful and cooperative, so that they were allowed to terminate the program early at the beginning of February 1999 due to a good forecast. In the final report, Klebold was recognized as having "very great potential," and Harris said, "Eric is a very intelligent young man who is likely to have success in life." Following the program, they began a one-year probationary period.

Planning and preparing for the act

Original plan

From the notes left by the perpetrators, it appears that they planned the crime for over a year. Klebold, who had been keeping a kind of diary since March 1997, first expressed the idea of getting a gun and running amok in November 1997. In February 1998, he was the first to mention the planned attack in his notes. Harris wrote in his diary conducted from April 1998 increasingly specific about their plan, which originally consisted of several acts: first, they planned two homemade propane gas bomb using timed detonators to explode in the school cafeteria. Afterwards, they wanted to shoot as many of the survivors of the explosion as possible while they were fleeing the school building. Eventually, more time bombs were supposed to detonate in their cars in the school parking lot, killing the arriving police officers, rescue workers and reporters. They intended to kill several hundred people and even risked the deaths of their own friends. Computer simulations carried out later by the investigators showed that an explosion of the bombs in the cafeteria would very likely have caused the ceiling to collapse and resulted in such a high number of victims. In the event that they survived the first three acts of their plan, Harris - two years before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 - toyed with the idea of hijacking a plane and crashing it over New York City in his diary. They studied the processes and habits at their school, determined hand signals with which they would communicate with one another during the attack, and targeted the month of April 1999 for the commission.

Arsenal of weapons

During the rampage, Harris fired a sawed-off pump gun and a semi-automatic Hi-Point Carbine gun . Klebold used a semi-automatic TEC-9 and a double-barreled sawed-off shotgun . They fired a total of 188 shots on the day of the incident. In addition to the firearms and self-made propane gas bombs , their accumulated weapons arsenal also consisted of several knives and a total of almost 100 self-made Molotov cocktails , carbon dioxide and pipe bombs , which they stored in various hiding places in their rooms and on the day they were in rucksacks, sports bags and attached to their harnesses Carried bodies with them. Investigators later found evidence that the perpetrators had worked to make napalm , which they did not use on the day of the crime.

The firearms and ammunition they had obtained from their adult friends Robyn Anderson, Mark Manes and Philip Duran, who did not know what the weapons should be used for. The 18-year-old Anderson bought the three rifles in November 1998 at a weapons exhibition from private individuals for the perpetrators who were still underage. The TEC-9 was acquired by Klebold in January 1999 for $ 500 from Manes; the contact had been made by Duran. Harris and Klebold earned the money to buy weapons as temporary workers for a pizza delivery chain. On March 6, 1999, they drove to a wooded area with Manes, his girlfriend, and Duran to practice shooting while they were filmed by Duran. The recordings were released after the fact and known as the Rampart Range . Manes accompanied the perpetrators to two more target practice sessions shortly before the rampage.

Your plan went unnoticed until the very end. While their closest friends knew the two were building bombs and had obtained weapons, they did not see them as a serious threat. Some of the statements made by the perpetrators, which their friends interpreted in retrospect as possible hints of the crime, were not recognized as such in advance or taken seriously. However, a few times Harris and Klebold were on the verge of being spotted in their preparations. Harris is said to have told a friend that his father found one of his pipe bombs in February 1998. Wayne Harris then kept the bomb in the parents' bedroom and later let it explode outdoors. (Since it was just a hearsay testimony , Wayne Harris denied the incident, and there was no further evidence that it actually did occur, Harris' father was not prosecuted.) In December 1998, an employee at the gun shop called, from whom Harris had ordered ammunition at his parents' house to inform them that the goods had arrived. Harris's father, who answered the call, thought the order was wrong and asked no further questions.

Self-presentation

Harris and Klebold were the first school shooters who staged themselves as antiheroes in the media and created their own “ brand ” by disseminating their ideas on the Internet, making cultural references to music, films and video games and leaving numerous notes and sketches for posterity that should provide information about their intentions, approach and motivation. The author André Grzeszyk wrote about their self-portrayal: “[They], aware of what would happen, managed their inheritance through their notes even before their death - their own image as they later wanted to see it reconstructed in the media. The fact that their diaries were published by the police [...] did the rest to make them known worldwide. "According to the journalist Joachim Gaertner, Harris and Klebold depicted the crime in their notes in a kind of literary fantasy and it becomes clear," [ …] How the two became more and more intoxicated with their own fantasies, how they soaked up hatred and aggression, how they took their own texts as a promise of the ultimate and then real kick. ”The monstrousness of their deed and their fantasies stand in striking contrast their everyday, ordinary life testimonies and one suspects that these two teenagers were not monsters, but surprisingly normal.

From March 15, 1999, the two shot several videos that they had intended for the public. On the tapes they presented themselves as their self-made alter egos “Reb” (Harris) and “VoDkA” (Klebold) and talked about their plan of attack and their motives. The videos became known as basement tapes because they were shot mostly in the basement of the Harris family's home. The recordings were shown to the parents of the perpetrators, victims' relatives and a select group of journalists, but were never published due to concerns about copycat offenders and were destroyed in 2011. A summary of their content as well as quotes from the perpetrators were nevertheless published by the press and announced with the official police report.

The self-portrayal of the two perpetrators can also be seen in their clothing: In their videos they shot themselves, they often showed themselves with upside down baseball caps , sunglasses and long black, trench- like coats. On the day of the tattoo, they hid their weapons under these coats and wore combat pants, combat boots and self-designed T-shirts. In Harris' shirt, the inscription was Natural Selection ( Natural Selection ) and Klebold's shirt standing Wrath ( anger ) written. They also shared a pair of black, fingerless gloves, with Harris putting on the right glove and Klebold putting on the left. The aesthetic they created with their outfits was later copied by several copycat criminals.

Sequence of events

Events just before the rampage

On the morning of April 20, 1999, the perpetrators left their homes before sunrise. Instead of taking bowling lessons, they went to a shop to get the propane bottles for their bombs. Then they drove to the Harris family home, where they finished building the bombs, loaded their cars and shot a short farewell video - the last part of the basement tapes . They then drove separately to a nearby park, where they planted a bomb and set the time fuse to 11:14 a.m. The explosion of this bomb was initially intended to distract the police from the actual crime scene, but only caused a grass fire that was ignored by the emergency services.

According to the authorities, the perpetrators reached the south parking lot of Columbine High School at around 11:10 a.m., on the premises of which there were an estimated 2,000 students and 140 employees on that day. Klebold parked his car in front of the school cafeteria, Harris parked a hundred yards away near the student entrance. Brooks Brown saw Harris arrive and walked up to him and asked him why he hadn't come to class that morning. According to Brown, Harris replied that it no longer mattered and asked him to leave the school premises. Brown complied with the request.

According to the police report, the perpetrators entered the cafeteria, monitored by four video cameras, shortly after 11:14 a.m., where around 500 people were staying at the time. Unnoticed, they put down two sports bags, each containing a propane gas bomb with a timer set to 11:17 a.m. Due to a video tape change, the time between 11:14 a.m. and 11:22 a.m. was not recorded by the surveillance cameras, which is why the placement of the bombs was not filmed according to official information. However, an evaluation of the published video recordings carried out by amateurs later raised doubts about the missing recording and the official timing of the crime. According to the amateur evaluation, Harris could already be seen on the videotape at 10:58 am when he brought in one of the two sports bags; A few seconds later, Klebold appeared in the surveillance camera image with the other sports bag in hand. The authorities did not comment on the amateur evaluation and pointed out that the investigations into the case had been concluded.

11:19 am: The rampage begins

|

Fatalities and injuries at the beginning of the rampage |

| 1. Rachel Joy Scott , 17 years old, killed. |

| 2. Richard Castaldo , 17 years old, injured. |

| 3. Daniel Lee Rohrbough , 15 years old, killed. |

| 4. Sean Graves , 15 years old, injured. |

| 5. Lance Kirklin , 16 years old, injured. |

| 6. Michael Johnson , 15 years old, injured. |

| 7. Mark Taylor , 16 years old, injured. |

| 8. Anne Marie Hochhalter , 17 years old, injured. |

| 9. Brian Anderson , 16 years old, injured. |

| 10. Patricia Nielson , 35 years old, injured. |

| 11. Stephanie Munson , 16 years old, injured. |

| 12. William David Sanders , 47 years old, killed. |

After the perpetrators placed the bombs in the cafeteria, they returned to their cars, where they armed themselves and waited for the explosion. Since this did not happen due to a technical error, they spontaneously changed their plan and opened fire on nearby students at 11:19 a.m. at the top of the stairs to the west entrance of the school. They also set off pipe bombs and threw them down the stairs and onto the roof of the school building. The first fatality was 17-year-old Rachel Scott , who had spent her lunch break with Richard Castaldo of the same age on the lawn in front of the west entrance and was shot by Harris. Castaldo sustained multiple gunshot wounds and suffered permanent paraplegia from the waist. Daniel Rohrbough, Sean Graves and Lance Kirklin were hit by multiple gunshots as they came up the stairs. 15-year-old Rohrbough succumbed to his injuries on site.

Next, the perpetrators shot a group of five students who were on a hill next to the stairs. Michael Johnson and Mark Taylor were seriously injured, the three other students escaped physically unharmed. While Harris continued to shoot, Klebold went down the stairs to the side entrance of the cafeteria to see - as investigators later suspected - why the bombs hadn't exploded. On the way there he shot again at the already fatally injured Rohrbough and at close range at Kirklin, who was also injured on the ground. He survived, but later had to undergo several surgical procedures. Paralyzed from the waist down from his gunshot wounds, Graves had made it to the side entrance of the cafeteria in search of cover, where he lay lying and pretended to be dead when Klebold stepped over him as he entered the cafeteria.

At the beginning of the rampage, the students in the cafeteria had mistaken the shooting that could be heard from outside as a prank for the senior class or a film production for Harris' and Klebold's video course. The teacher William David “Dave” Sanders, however, recognized the danger early on and asked the students to get to safety, whereupon they fled the cafeteria or hid under tables and in the kitchen. Klebold glanced briefly around the cafeteria without firing or approaching the bombs, and then returned to Harris on the stairs, from where they continued to fire at students fleeing. Anne Marie Hochhalter was hit by Harris' gunshots and suffered permanent paraplegia from the waist.

Teacher Patricia Nielson, who supervised the break inside the building, believed in a video shoot with toy guns when she spotted Harris with his gun through the glass panels of the front door, and went outside to stop it. It was only when Harris shot the glass door through, grazed her shoulder with a graze, and the student Brian Anderson next to her was injured by broken pieces of metal and glass that Nielson realized the gravity of the situation. She and Anderson turned and ran to the library, where Nielson told the students in attendance to take cover under the tables.

At about 11:22 am Jefferson County Deputy Neil Gardner, who patrolled Columbine High School, was radioed to the school's south parking lot by a caretaker. When Gardner got there in his patrol car around 11:24 a.m., he was shot at by Harris while getting out of the car. Gardner took cover behind his car and returned fire, but missed both perpetrators, who then went into the school building, where they shot down the hallways and dropped pipe bombs. Student Stephanie Munson was injured and Dave Sanders was shot, who was still busy warning students and getting them to safety. With the help of a colleague, he was seriously injured and brought to a classroom, where students barricaded themselves with him, gave first aid and called the emergency number several times. He died a few hours later due to excessive blood loss before rescue workers could take him to hospital. Harris reappeared in the west entrance around 11:26 a.m. and engaged in another shootout with Gardner before retreating back into the building.

11:29 am to 11:35 am: What happened in the library

|

Fatalities and injuries in the library |

| 13. Evan Todd , 15 years old, injured. |

| 14. Kyle Albert Velasquez , 16 years old, killed. |

| 15. Daniel Steepleton , 17 years old, injured. |

| 16. Makai Hall , 18 years old, injured. |

| 17. Patrick Ireland , 17 years old, injured. |

| 18. Steven Robert Curnow , 14 years old, killed. |

| 19. Kacey Ruegsegger , 17 years old, injured. |

| 20. Cassie René Bernall , 17 years old, killed. |

| 21. Isaiah Eamon Shoels , 18 years old, killed. |

| 22. Matthew Joseph Kechter , 16 years old, killed. |

| 23. Mark Kintgen , 17 years old, injured. |

| 24. Lisa Kreutz , 18 years old, injured. |

| 25. Valeen Schnurr , 18 years old, injured. |

| 26. Lauren Dawn Townsend , 18 years old, killed. |

| 27. John Robert Tomlin , 16 years old, killed. |

| 28. Nicole Nowlen , 16 years old, injured. |

| 29. Kelly Ann Fleming , 16 years old, killed. |

| 30. Jeanna Park , 18 years old, injured. |

| 31. Daniel Conner Mauser , 15 years old, killed. |

| 32. Corey Tyler DePooter , age 17, killed. |

| 33. Jennifer Doyle , 17 years old, injured. |

| 34. Austin Eubanks , 17 years old, injured. |

The perpetrators entered the library at 11:29 a.m., where Nielson, three other employees and over 50 students were hiding under the desks and in adjacent rooms. Since Nielson had dialed 911 and held the phone at around 11:25 a.m., the following events - gunshots, explosions, and exchanges - were recorded in the 911 call. The first four of the 26-minute recordings were later published.

After the perpetrators had unsuccessfully asked the jocks present in the library to come out of their hiding places, they took fire at the individual tables. According to eyewitnesses, they backed each other and their actions were coordinated. After 15-year-old Evan Todd was injured by flying splinters of wood, 16-year-old Kyle Velasquez was fatally shot by Klebold. Then the perpetrators shot through the library window at the police who had meanwhile arrived in front of the school building, but only caused property damage. The police returned fire, whereupon the perpetrators withdrew from the windows and continued shooting under the tables and throwing explosive devices. Meanwhile, they laughed and harassed the students crouched under the tables.

Klebold wounded Daniel Steepleton, Makai Hall and Patrick Ireland, who were under the same table, with his shots. (Ireland suffered temporary paralysis on one side from his gunshot wounds and lost consciousness several times over the next few hours before he made it to one of the library windows on his own, through which he fell from the first floor into the arms of rescue workers at 2:38 p.m. left.) Harris killed 14-year-old Steven Curnow and seriously injured Kacey Ruegsegger. He then shot 17-year-old Cassie Bernall from close range, with the recoil of his gun breaking his nose. Witnesses later reported that he appeared dazed from then on.

In the meantime, Klebold had discovered the 18-year-old African American Isaiah Shoels under a table and abused him with racist remarks. After trying in vain to pull Shoels out from under the table, Harris shot him. Klebold killed 16-year-old Matthew Kechter, who was next to Shoels. Then Harris threw a bomb under the table, which was Steepleton, Hall and Ireland. Hall managed to throw the bomb away before it exploded in midair. After Klebold shot Mark Kintgen, he fired under a table near the entrance, under which several girls had taken cover. He injured Lisa Kreutz and Valeen Schnurr and killed 18-year-old Lauren Townsend. Harris shot under another table, injuring John Tomlin and Nicole Nowlen. When 16-year-old Tomlin tried to move out of Harris' line of fire, he was shot dead by Klebold. Harris then killed 16-year-old Kelly Fleming. His shots also injured Jeanna Park and Lisa Kreutz, who was already shot by Klebold.

The perpetrators only allowed one student to leave the library: when Harris asked who was under one of the desks, John Savage, whom both perpetrators knew, had revealed himself. When Savage asked if they would kill him, Klebold hesitated for a moment and then told him to leave, whereupon Savage ran away. Fifteen-year-old Daniel Mauser, who had been at the table next door to Savage, was the only student who defended himself by banging a chair against Harris. Then he was shot by Harris. 17-year-old Corey DePooter was the library's last fatality. He died when the perpetrators fired multiple shots at 11:35 am, also injuring Jennifer Doyle and Austin Eubanks. Although the perpetrators had enough ammunition to kill the rest of the students in the library, they did not fire any more shots at them. The Columbine -author Dave Cullen believes that Harris had lost interest in the killing at this time and Klebold everything was indifferent.

11:36 a.m. to 12:08 p.m .: Final phase and suicide of the perpetrators

At 11:36 a.m., the perpetrators left the library. They wandered aimlessly through the hallways and passed several classrooms in which many students were still hiding. Some of them later reported that the perpetrators made eye contact with them through the door windows but made no move to enter the classrooms. Instead, they shot into empty rooms. The video cameras filmed at 11:44 a.m. how the perpetrators came down the stairs to the cafeteria, where at that time some students were still hiding under the tables. By shooting and throwing an explosive device in the direction of the two propane gas bombs, the perpetrators tried to detonate them, but only caused a fire. The fire drove the students out of their hiding places and they ran out through the emergency exits. The activated sprinkler system flooded the cafeteria.

Around 12:00 p.m. the perpetrators returned to the library, where at that time, in addition to the ten dead, there were only Patricia Nielson, who was hiding in a closet, and the seriously injured Patrick Ireland and Lisa Kreutz. The other students had fled through the emergency exits in the meantime. Cullen suspects that the perpetrators wanted to watch the explosion of their car bombs planned for 12:00 noon from the library, which however also failed to occur due to a technical error. Through the windows they had one last exchange of fire with the police before retreating inside the library.

| Death of the perpetrator |

| 35. Eric David Harris , 18 years old, suicide. |

| 36. Dylan Bennet Klebold , 17 years old, suicide. |

One of the two perpetrators lit another Molotov cocktail, then they committed alongside one another suicide by pointing their guns against themselves. Based on the positions in which their bodies were found, investigators concluded that Harris was the first of the two to shoot himself. The Molotov cocktail caused a fire that started the sprinkler system in the library at 12:08 p.m. On the basis of the later secured evidence at the scene of the crime, it was found that the perpetrators were already dead at this point.

Use of the police and rescue services

At 11:23 am, the operations control center had issued the first emergency call to all police and rescue vehicles in the vicinity of Columbine High School. In the minutes and hours that followed, almost 800 police officers from 35 different law enforcement agencies arrived on site with their vehicles. The officers encircled a school building, watching the outputs, evacuated those students who had made it out of the building, and gave fire . Paramedics and firefighters took care of the injured and took them to the surrounding hospitals.

The emergency services later reported about chaotic conditions. Hundreds of panicked people fled the school, gunfire and explosions could be heard inside the building and helicopters circled over the premises. The emergency lines were completely overloaded as hundreds of students who were still in school called for help on their cell phones. Police officers questioned those who had fled to get a precise picture of the situation in the building, but received contradicting information about the number of attackers, their appearance and exact whereabouts, and the weapons they used. Parents who heard about the gunshots at Columbine High School on the news headed to school and had to be prevented by emergency services from approaching the building.

At 12:06 p.m., the first Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) unit entered the school building, a second SWAT team followed at around 1:15 p.m. The officers sequentially checked every room in the school and evacuated numerous students who were taken to the nearby Leawood Elementary School, where the waiting family had now gathered. According to the authorities, one of the SWAT teams reached the room where Dave Sanders was at around 2:42 pm, but for whom any help was too late. The first officers entered the library at 3:22 p.m. and shortly afterwards reported the discovery of the ten victims and the deaths of both perpetrators. They also rescued Lisa Kreutz, who was almost bleeding to death, and evacuated Patricia Nielson from her hiding place and the three other employees from the adjoining rooms. At 4:00 p.m., the sheriff announced the death of the perpetrators to the media and erroneously estimated the number of fatalities at about 25. In fact, 15 people - including the perpetrators - died in the rampage. Three of the total of 24 wounded suffered their injuries while trying to escape the perpetrators.

Preliminary investigation

After numerous witnesses identified Harris and Klebold as attackers, investigators obtained search warrants for their parents' homes. On the day of the crime, the officers secured ammunition, material for building bombs, a page from the Anarchist Cookbook , calculations, diagrams, a schedule and the basement tapes in Harris' room . Pipe bombs and several records were confiscated from Klebold's room. On the night of April 20-21, 1999, ATF officers searched the school building for explosives and checked every one of the almost 2,000 student lockers and around 700 rucksacks that students had left behind during their escape. Some of the captured bombs had already exploded and caused massive damage to the building, but several bombs were still intact and had to be detonated in a controlled manner. After the building was secured, around 40 officers began securing tracks over an area of almost 25,000 m 2 . The list of the seized evidence finally comprised 30,000 pages. The bodies of the victims and perpetrators were not transferred to forensic medicine until the day after the rampage.

In the first 72 hours after the rampage began, the police interrogated around 500 witnesses, and later another 5,000 interrogations followed. At the beginning of the investigation, the officers believed, due to the scale of the crime, that there must be other people involved , and so some school friends of Harris and Klebold came under suspicion. Three of them were arrested on the day of the crime, but released shortly afterwards for lack of evidence. Robyn Anderson and Mark Manes surrendered to police the day after the rampage and in May 1999, respectively, and confessed to having obtained the guns from the perpetrators. In total, the investigation, which involved around 100 officials from 20 different authorities, lasted six months. The Jefferson County Sheriff's Office published its results in the official Columbine Report in May 2000 . In November of the same year, the authority brought out around 11,000 pages with the recorded testimony. Up to October 2003 further documents with a total volume of 15,000 pages were published successively. In 2006 the Sheriff's Office published the more than 900 pages of the perpetrators' personal records and documents (Columbine Documents) .

The investigation report published in May 2000 stated that Daniel Rohrbough was first hit by Harris' shots, but then was shot dead by Klebold from close range. Rohrbough's parents questioned this version of the incident because they saw the investigation report as inconsistent. Rather, they suspected that their son was accidentally killed by a police officer. The subsequent independent investigation by the Sheriff's Office of neighboring El Paso County came in April 2002 on the basis of the ballistic report and several testimonies to the result that the fatal shot had been fired "without reasonable doubt" by Harris.

Psychological profile of the perpetrator

Basis of profiling

In retrospect, case analysts from the FBI created a psychological profile of the perpetrators based on the diaries and video recordings they left behind. They came to the conclusion that Harris was a homicidal psychopath , while Klebold was depressed and suicidal . Dwayne Fuselier, chief investigator on the case, said: “[Eric] went to school to kill people and he didn't care if he was going to die while Dylan wanted to die or if he didn't care others would die too. ”Sociologist and author Ralph Larkin criticized this characterization as“ simplified ”. They devour the identities of the perpetrators and reduce them to a label. The author Rita Gleason is of the opinion that this blanket account of the perpetrators neglects the influence of their life experiences: “Eric Harris was not meant to kill. Dylan Klebold's self-hatred did not develop in a vacuum . "

Both perpetrators wrote in their diaries about feeling excluded and not accepted as well as about their lack of self-esteem. Otherwise, however, their notes show significant differences in their content and writing style. While Harris predominantly expressed anger, contempt, hatred and thoughts of murder in his diary, Klebold wrote primarily about his depression and suicidal thoughts, as well as his loneliness and search for true love. According to psychologist Peter Langman , Harris' spelling appears clear and eloquent, but Klebold's trains of thought would appear confused and disorganized. Harris drew weapons and swastikas , while Klebold painted hearts. Their different personalities were also shown on the basement tapes . According to Fuselier, the photos would have seemed to the layman as though Klebold was the more dominant of the two. He was loud, unrestrained and angry, while Harris appeared calm and controlled and preferred to give instructions behind the camera. But Klebold betrayed himself through his eyes, with which he repeatedly sought Harris' confirmation.

Harris

Many experts believe that Harris was a psychopath who met numerous criteria on Robert D. Hare's psychopathy checklist . According to Fuselier, he was, among other things, manipulative , empathetic and unscrupulous, superficially charming and a habitual liar who enjoyed deceiving others. However, the psychopathy diagnosis is also viewed critically by some authors. One of the arguments against this characterization is the fact that Harris did show feelings such as sadness, depression or loneliness and was described by contemporaries as capable of empathy. In addition, no behavioral problems such as animal cruelty are known from his childhood. The extreme violence he showed and his suicide were also untypical for a psychopath. Gleason complains that the diagnosis was only made on the basis of diary and video recordings. Since Harris could no longer be examined personally, she (like the diagnoses in Klebold's case) should not be treated as a fact.

Langman and psychologist Aubrey Immelman describe Harris as an anti-social , sadistic , narcissistic, and paranoid personality. According to Immelman, he fulfills the criteria of the personality syndrome that Otto F. Kernberg calls “malicious narcissism”. His sadistic nature was expressed by the fact that he mocked and harassed his victims during the rampage and wrote about torture and rape fantasies in his diary. Langman believes that by building a facade of superiority, Harris attempted to compensate for low self-esteem , which is believed to be due to the unstable social environment during his childhood and his congenital chest deformity. He had the exaggerated need for recognition that is typical of a narcissist, whereby his narcissism exceeded the limit of megalomania . This can be seen, for example, in the fact that he compared the planned attack in his diary with the riots in LA and the Second World War . Hare believes that Harris' tirades of hate toward all of humanity were the expression of a complex of superiority .

Klebold

People who knew both perpetrators were particularly shocked by Klebold's involvement. In his outward appearance, he was a quiet and shy but normal teenager with plans for the future who participated in social life and was liked by many of his peers. Neither his family nor his closest friends suspected that behind this facade was a lonely and depressed person who had been suicidal two years before the crime and who trusted his diary to scratch himself . He sought relief from alcohol and smoked marijuana . As with many other gunmen, his depression and self-loathing eventually turned into anger and hatred of others. Cullen and Langman believe that Klebold could have been helped if someone had recognized their mental health problems.

In addition to the depression, post mortem characteristics of a self-insecure-avoidant , a passive-aggressive and a dependent personality disorder were identified. Langman also thinks it possible that Klebold had a schizotypic personality disorder . Among other things, his strange spelling, his feeling of alienation from himself , his external appearance, which others describe as "peculiar", and his sometimes paranoid and delusional thoughts speak for this . In his fantasy world, he rose to be a godlike being in order to cope with his loneliness and social fears. According to Immelman and Fuselier, Klebold also had sadistic traits, but these are not as pronounced as in Harris' case. Although Klebold also exhibited psychopathic behaviors, experts do not consider him a psychopath because - atypical of a psychopath - he expressed guilt, remorse and shame in his notes. Langman thinks that Klebold compensated for his insecurity with his psychopathic behavior: "The shy boy who did not have the courage to ask a girl out on a date became an intimidating mass murderer."

Perpetrator dynamics

Because of the profiles created, Harris is often seen as the mastermind and the driving force behind the rampage, while Klebold is classified as a follower. Several witnesses reported that Klebold submitted to Harris in the course of the crime. He followed his instructions and tried to impress him. Langman believes that there have been several occasions during the rampage that Klebold - unlike Harris - spared potential victims. Gleason, on the other hand, does not see a pure follower in Klebold. He had been able to assert himself against Harris and had a significant part in the planning, preparation and execution of the act.

Some experts, including Fuselier, consider it absurd that Klebold would have carried out the deed without Harris. It is more likely that Harris would have committed the act alone or in later adulthood, an even greater crime. Other experts, such as the psychiatrist Frank Ochberg, who supported the FBI in creating the perpetrator profiles, however, assume that neither of the two gunmen would have committed the crime without the other. The presence of the other had encouraged her in her plan and at the same time she prevented one of them from withdrawing from the plan. According to Cullen, based on the perpetrator profile created by the FBI, the sadistic, psychopathic Harris and the angry, unpredictable Klebold were an explosive couple who fed each other. Without the enthusiasm of the hot-headed Klebold, the cool, controlling Harris would have lacked the stamina to implement the plan.

According to Langman, the fact that Harris and Klebold became accomplices is because they were drawn to their opposites. Harris was able to take on the role of leader, which corresponded to his need for recognition, and the insecure, dependent Klebold found support with him. Andrew Solomon has the impression that Klebold participated in the murder for Harris' sake, and that Harris participated in the suicide for Klebold's sake. Larkin says that both perpetrators "desperately needed" each other. Harris gave Klebold's life drive, purpose and purpose; For Harris, Klebold was a willing ally who confirmed his worldview. Together they were a force to be reckoned with, but separately only a few nerds at the bottom of the social hierarchy of Columbine High School.

Motivation to act

There was intense speculation about the perpetrators' motives, but they could not be clarified with any certainty. In early media reports, a neo-Nazi background was suspected, among other things because the rampage took place on April 20 - Adolf Hitler's birthday -, Klebold had racially insulted one of the victims and some witnesses reported that the perpetrators showed the Hitler salute after a bowling strike . However, the investigators could not confirm the neo-Nazi motive. Although Harris wrote in his diary about his admiration for the Nazis , he made no connection to the planned attack. There were also other testimonies according to which Klebold - who himself had Jewish ancestors - did not share Harris' interest in National Socialism . In addition, after viewing the basement tapes , the investigators came to the conclusion that the perpetrators had actually set April 19, 1999 as the date of the crime. Apparently due to a delay in the delivery of ammunition, they finally postponed the planned attack to the following day. Their records do not provide any justification for the original choice of April 19 as the date, but it is believed that they were intended to celebrate the anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995.

Furthermore, revenge for the bullying suffered, lack of social acceptance and exclusion was discussed as possible motives in the media. According to witnesses, the perpetrators are said to have said several times during the rampage that they would take revenge for what their classmates had done to them for years. They also expressed their intentions for revenge and pent-up anger in their notes and on the basement tapes . They also kept “hate lists” with the names of students who had attacked or offended them in the past. The investigating authorities, on the other hand, viewed the motive for revenge critically because the perpetrators had not targeted their tormentors and were not bullied by any of the victims killed. Rather, the investigators assumed that the motive for the rampage was the pursuit of fame. From what they said in the video recordings and written records they left behind, it is clear that Harris and Klebold were aware that the act would make them celebrities. In one of the videos they discussed which Hollywood director should film their story, and Harris wrote in his diary that he wanted to leave a lasting impression on the world. FBI agent Mark Holstlow stated, “[They] wanted to be immortal [...] They wanted to be famous. And they are. They are notorious. "

Larkin believes they were both interested in revenge and fame. While the killing of their victims during the rampage was indiscriminate, their real plan was to destroy the whole school and murder everyone in it, as they blamed all their classmates for their low social status. At the same time, they wanted to become famous for the spectacular extent of their act of revenge they had hoped for. Her act also had a political character: Harris and Klebold understood that their pain and humiliation were shared by millions of other students, and carried out their attack on behalf of a larger collective. Cullen criticizes that such a view turns two brutal mass murderers into folk heroes.

According to Langman, Harris wanted to play God, dominate others and decide between life and death. His will to destroy was motivated by his own ideology. He despised the values of civilization and dreamed of wiping out what he saw as unsuitable humanity. It was therefore no coincidence that he wore a T-shirt with the words Natural Selection on it, but rather his message to the world. Klebold's motivation is less clear, but the act was probably an outlet for his anger and a way out of his suffering.

Consequences of the act

Coping with trauma for those affected

The event was tantamount to a social catastrophe and not only traumatized the students, teachers, emergency services and reporters who had directly witnessed the rampage, but also had a domino effect - similar to the indirectly affected relatives, friends and colleagues as well as the entire community of Littleton stressful out. In the days after the crime, many people sought refuge in the local churches or exchanged views with those who were also affected, while others preferred to withdraw or hide the events. Coping with grief and trauma was made more difficult by intrusive sensational journalists, disaster tourists and threats from free riders . Some of the victims later committed suicide, including six fire department first responders, Anne Marie Hochhalter's mother and a school friend of Matthew Kechter, who was in the classroom where Dave Sanders died on the day of the incident.

For the remainder of the school year, Columbine High School students were taught at nearby Chatfield High School. In the meantime, all damage and traces reminiscent of the crime have been removed from the school building. As part of the renovation, which cost $ 1.2 million, the stairs to the west entrance were redesigned, the original library was completely removed, and the cafeteria below was converted into a two-story atrium . The sound of the fire alarm, which could be heard for hours in the school building on the day of the act, was also changed to save the students from reliving the events over and over again. On August 16, 1999, Columbine High students returned to their school and had two additional counselors added to the staff. The reopening was preceded by a gathering entitled “Take Back the School”, attended by around 2,000 people. In June 2001 the new library, financed by donations, was inaugurated.

Many victims suffered permanent damage and disability from their gunshot wounds. The costs of their medical care and rehabilitation amounted to up to seven-figure sums in individual cases. The victims and their dependents received financial support from a donation fund of US $ 3.8 million. Some of the donations were also made available for trauma therapies . Numerous survivors of the rampage - including those who had not sustained any physical injuries - sometimes suffered from survivor guilt syndrome and other forms of post-traumatic stress disorder for years after the crime . For many of them, coverage of another mass shooting, such as the mass murder in Las Vegas in 2017, leads to retraumatisation .

The media followed the fate of several victims and bereaved relatives over the years and reported, for example, about Sean Graves' and Patrick Ireland's recovery from their paralysis or Austin Eubanks, who developed an opiate addiction for years while treating his injuries and in May 2019 at the age of 37 years died of a heroin overdose. Some survivors and bereaved people came to terms with what they had experienced by writing memoirs or becoming activists . Shortly after the crime, students from Columbine High School traveled to Washington, DC , to campaign for gun law to be tightened. Since the use of social media was not yet widespread at the end of the 1990s, the echo in the media and the population at that time was significantly lower than in the protest movements March for Our Lives and Never Again MSD , which were launched in response to the school massacre of Parkland emerged in 2018.

Search for causes and co-responsible

After the crime, the causes and culprits were sought in numerous public discussions. According to Schildkraut and Muschert, the only ones in whose direction the finger was not pointed were the perpetrators themselves. Experts like Peter Langman emphasize that school shoots are too complex to be traced back to a single cause or to be explained with simple answers. Rather, it is important to take into account a number of influencing factors and the fact that the perpetrators are usually mentally disturbed young people.

Bullying and the school's social climate

Many Columbine High School students reported after the rampage that bullying was part of everyday life at their school and was largely ignored or tolerated by the school management and teaching staff, as the bullying perpetrators were mostly successful athletes who were preferred by the teachers were treated. Brooks Brown later described the situation as follows: “When people wanted to know what Columbine was like, I told them about the bullies who relentlessly pounced on anyone they believed was among them. Teachers turned a blind eye to abuse of their students because they weren't the favorites. ”Some students and parents suggested that the failure of teachers to intervene and the unequal treatment of students contributed to Harris and Klebold developing revenge fantasies would have. Brown said, "Eric and Dylan are responsible for this tragedy, but Columbine is responsible for Eric and Dylan."

An official investigation into the social climate at Columbine High School scheduled in 2000 confirmed the veracity of the bullying reports, but found that few of these incidents were reported to the school administration, which is why they underestimated the extent of the violence was. A study published in 2002 by the US Secret Service and the United States Department of Education, which examined 37 school shootings in the United States, found that the perpetrators had been victims of bullying in the majority of cases. Many US school districts responded to the problem by introducing new or tightening existing anti-bullying policies. In addition, 44 US states passed laws requiring schools to introduce anti-bullying programs.

However, many experts and authors consider the bullying factor to be overrated in the case of Columbine. For example, Langman said: "[...] the degree to which Eric and Dylan were harassed was exaggerated and their harassment and intimidation of other students was overlooked or trivialized [...] It was said that bullying was so widespread in Columbine High School that the school had a poisoned culture. Even if so, it doesn't tell us why Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold of all the thousands of students who went through this poisoned culture ran amok. "

Side effects of psychiatric drugs

The autopsy of Harris and Klebold's bodies revealed that neither of them had been under the influence of alcohol or drugs during the crime. However, a therapeutic amount of the antidepressant fluvoxamine, sold under the US tradename Luvox, has been found in Harris' body . He was prescribed to take the drug as part of outpatient psychotherapy, which he had been in since February 1998 because of depression. At the beginning of the therapy, he was prescribed Zoloft , but after complaining of obsessive-compulsive negative thoughts, he switched to fluvoxamine in April 1998, the dose of which was gradually increased to 200 mg per day over the coming months.

After the fact, critics of psychiatric drugs claimed that the drug's side effects drove him on the rampage. This claim was countered by saying that Harris had homicidal thoughts even before taking fluvoxamine. In addition, he and Klebold, who had not been under the influence of medication, had the idea for the act months before the start of drug therapy. A causal connection between the commission of the crime and the fluvoxamine intake could not be proven. The civil lawsuits filed by some victim families against the Luvox manufacturer Solvay , which, among other things, were accused of not providing sufficient information about possible side effects of the drug, were later withdrawn.

Fictional violence in computer games and films

The media debated whether Harris and Klebold could have been induced to run amok through the consumption of fictional violence. Both perpetrators had shown a preference for the film Natural Born Killers - whose abbreviation “NBK” they used as the code word for the planned attack on their school - and often played violent computer games in their free time. Harris named one of the firearms he used in the act after a character from the first-person shooter series Doom and wrote in a school essay: “ Doom is so burned into my head that my thoughts are usually related to the game ... What I can not do in real life, I try to Doom to do "he also created his own. Doom - level , which he published on his website. After the rampage, the Simon Wiesenthal Center examined the game segments created by Harris and came to the conclusion that he had spent around 100 hours designing them and one of his versions ended in a massacre because the player was invincible.

While some post-crime studies found that media depicting violence in adolescents can increase hostility towards others and reduce their level of inhibition and empathy, other researchers found no robust evidence that aggressive and violent behavior had an impact on consumption Violence of performing computer games can be traced back. Claiming that the rampage would not have taken place without the influence of fictional violence, some victim members sued several computer game manufacturers and other entertainment companies for $ 5 billion in damages; however, the action was dismissed by the court on the grounds of artistic freedom .

In view of the public debate, the feature film Killing Mrs. Tingle (" Killing Mrs. Tingle ") was given the alternative title Teaching Mrs. Tingle at short notice before its US theatrical release on August 20, 1999 . The computer role-playing game Super Columbine Massacre RPG was released in 2005 ! , in which the rampage at Columbine High School can be re-enacted from the point of view of the perpetrators, which led to nationwide outrage and massive criticism in the USA.

US gun law

After the rampage, politicians and activists of the anti-weapons movement criticized the inadequate gun control in the USA, which enabled underage perpetrators to obtain firearms without major hurdles. As a result, over 800 bills to tighten gun law were introduced across the country, but only around ten percent of them were successful. While all bills at the federal level failed in Congress , several laws were passed in Colorado that, among other things, introduced a background check system and banned the purchase of weapons by straw men .

Despite popular protests, the National Rifle Association (NRA) held the annual meeting of the National Rifle Association (NRA) in Denver on May 1, 1999 - eleven days after the rampage - and an anti-weapons demonstration of around 8,000 people took place. Protesters included Tom Mauser holding up a sign that read, “My son Daniel died at Columbine. He'd expect me to be here today. " ("My son Daniel died of Columbine. He would expect me to be here today.") He went on to say, "There are many responsible gun owners. But it is time to understand that a semi-automatic TEC-9 weapon […] will not be used for game hunting. ” Charlton Heston , then President of the NRA, expressed his disappointment at the protest, as the weapons lobby would benefit from it Assuming complicity: "It implies that 80 million honest gun owners are somehow to blame."

Filmmaker Michael Moore used the events at Columbine High School as the starting point for his 2002 Oscar- winning documentary Bowling for Columbine , in which he questions the causes of gun violence in the United States. In one scene of the film, the surviving victims Richard Castaldo and Mark Taylor accompany him to the Kmart supermarket chain , where the perpetrators bought some of their ammunition, and in a symbolic act return the bullets that were in their bodies. Kmart responded by stopping ammunition sales across the country.

Gothic culture and music industry

Early media reports claimed that the perpetrators were members of the so-called Trench Coat Mafia . This was a group of teenage outsiders who mostly wore long black coats, were associated with Gothic culture , and were often in conflict with the jocks of Columbine High School. Although Harris and Klebold also often wore black coats to school and were friends with some members of the Trench Coat Mafia , they were neither part of the group nor were they Goths. Nevertheless, the reporting meant that the Gothic movement and students who dressed contrary to the mainstream were met with increasing distrust and hostility. Many U.S. schools have dress codes that prohibit the wearing of trench coats or black clothing.

Since Harris and Klebold had heard the music of Rammstein and KMFDM , the media accused them of having been influenced by song texts that addressed their violence. Sascha Konietzko from KMFDM then announced that the group condemned violence against others. Rammstein stated that members of the band had children of their own and would constantly strive to instill healthy and non-violent values in them. Although there have been conflicting reports as to whether the perpetrators were fans at all, Marilyn Manson , frontman of the band of the same name , was hit by a number of headlines such as "Killers Worshiped Rock Freak Manson" or "Devil-Worshiping Maniac Told Kids To Kill" was associated with the killing spree. According to Manson, this caused his record sales to collapse and he received numerous death threats.

A few days after the crime, the band canceled the rest of the US concerts on their Rock Is Dead tour out of respect for the victims and Manson declared: “The media have unfairly scapegoated the music industry and so-called Gothic kids and assumed without any real basis that artists were how i am responsible in some way. This tragedy was the product of ignorance, hatred and access to arms. I hope that the irresponsible hints of the media don't lead to kids who look different being discriminated against even more. "

Later interviewed by Michael Moore for Bowling for Columbine , when asked what he would say to the Columbine kids if he had the chance, Manson replied, “I wouldn't say a single word to them, I would listen to what they are have to say and that's what nobody did. "

The parents of the perpetrators

Shortly after the rampage, both parents made statements through their lawyers expressing their condolences to the victims. In the following years they were exposed to massive criticism as well as numerous accusations and hostility from the public. They were accused of, among other things, a lack of parental care and overlooked warning signals. According to a poll, 83 percent of the US citizens surveyed believed that their parents were partly to blame. While Wayne and Katherine Harris never publicly commented on their son's rampage or criticism of them again, the Klebolds first commented on the allegations in an interview with the New York Times in May 2004 , stating that their son was not responsible for but committed against his upbringing. Contrary to the expectations of many, the perpetrators did not come from broken families. Friends and acquaintances of their families described Wayne and Katherine Harris as well as Thomas and Sue Klebold as attentive, concerned, and committed parents who would have responded to misconduct by their children with standard parenting measures such as house arrest or the restriction of privileges. Both perpetrators expressed their appreciation for their parents on the basement tapes and that they were not to blame.

The Klebolds granted another interview in 2012 for Andrew Solomon's book Far From the Tribe . In 2016, Sue Klebold's memoir Love Is Not Enough was published , in which she tries to find explanations for what her son did and how the act could have been prevented. She sees her failure as failing to recognize the signs of her son's mental health problems. Klebold donates her share of the book's proceeds to suicide prevention, for which she has been committed since the rampage. The foreword to the book was provided by Solomon, who wrote: “I believed that your story would reveal numerous, definite mistakes [in parenting]. I didn't want to like the Klebolds because the price for that would be admitting they weren't to blame for what happened, and if they weren't to blame, neither of us are safe. Unfortunately, I liked her a lot. And so I came to the conclusion that the madness of the Columbine massacre could have emerged from any home. "

Legal processing

The parents of the perpetrators were not prosecuted. Mark Manes was sentenced to six years in prison in November 1999 for illegally selling weapons to the minor Klebold. In 2003 he was released early on parole. Philip Duran, who had helped with the deal, was sentenced to four and a half years in prison in June 2000 and was also given early parole in November 2003. Robyn Anderson could not be prosecuted because at that time in Colorado it was not illegal to purchase rifles from unlicensed dealers and pass them on to minors due to a loophole in the law . The so-called “Robyn Anderson Act” passed after the rampage now requires the consent of a parent or legal guardian to pass it on.

Numerous survivors of the rampage and the bereaved relatives of the killed victims filed civil suits for damages and compensation for pain and suffering, with the proceedings sometimes dragging on for years. Defendants included the Jefferson County's Sheriff's Office and School Board. The plaintiffs accused the police of not acting decisively enough against the two gunmen and believed that the massacre in the library and Dave Sanders' death could have been prevented by more swift action by the emergency services. The school officials were accused of overlooking warning signs. The lawsuits against the Jefferson County authorities were initially dismissed in November 2001. In the appeal, plaintiffs were awarded $ 15,000 by each of the two authorities and the proceedings were declared closed. Only Patrick Ireland and the surviving dependents of Dave Sanders were paid higher sums (US $ 117,500 and US $ 1.5 million respectively) without admission of guilt.

The parents of the perpetrators as well as Manes, Duran and Anderson were also sued under civil law. In April 2001, the perpetrators' parents reached a settlement for $ 1.6 million with over 30 families of victims. The sum was evenly divided among plaintiffs and came from defendants 'homeowner insurance policies, with the Klebolds' insurer paying $ 1.3 million and the Harris family's insurance covering the remaining $ 300,000. The sued friends of the perpetrators contributed a total of another 1.3 million US dollars. Five families of the victims rejected the settlement because they asked the parents of the perpetrators to be informed so that such acts could be prevented in the future. In 2003 a settlement was reached with these families, the content of which was not made public. The Klebolds and Harrises also agreed to testify under oath and in camera in July 2003. The recorded statements were sealed by court order and will not be published until 2027. Because of their historical value, they are kept in the US National Archives.

Preventive measures

Increasing security in schools

After the rampage, numerous schools in the United States increased their security measures. The expenditures for this amounted to almost three billion US dollars in 2017 alone. The measures taken include the installation of video surveillance systems and metal detectors, increased presence of security guards or police patrols, random searches , the closing of the entrances to the school building during lessons and identification requirements for visitors. Numerous schools have also established rules of conduct in the event of a killing spree and regular amok alarm exercises. These so-called active shooter drills have proven to be effective, but at the same time they are criticized for potentially having negative psychological effects on the children.

The zero tolerance strategy pursued in many places with regard to threats to classmates or the possession of weapons on the school premises is also criticized . According to the critics, the strategy according to which even a minor violation can be expelled from school or a psychological examination can be ordered leads to disproportionate punishment of students and disregard for the rights of the individual. The FBI issued guidelines for schools on warning signal detection in 2000. After that, most school shooters would announce their act directly or indirectly (so-called leaking ). Based on this knowledge, the 24-hour Safe2Tell hotline was set up in Colorado in 2004 , which students can contact anonymously in suspected cases and which had received over 30,000 reports by the beginning of 2019.

Change of police tactics in rampaging cases

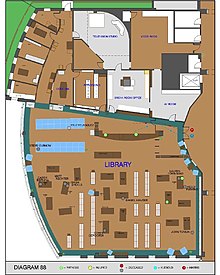

During the rampage, the patrol police, who first arrived at the scene of the crime, followed the guidelines applicable at the time and did not storm the school building immediately , but initially treated the situation like a hostage-taking and waited for the SWAT team specially trained for this scenario. However, they were not familiar with the location and had to orient themselves when entering the school using a faulty building plan and sketches by students. The situation was made more difficult by the fact that communication between the officers of the various authorities was difficult, as their radios were operated on different bandwidths and were therefore incompatible. Communication within the building was also hampered by smoke and the fire alarm that sounded for hours.

The late intervention of the police and the delays during the access led to massive criticism from the public. The officers were accused, among other things, of putting their own safety above that of the children. As a consequence, the Department of Homeland Security published the Active Shooter Protocol in 2003, a new police tactic that now provides for immediate intervention by the patrol police in the event of an "active shooter" (as opposed to a hostage-taker who does not shoot). The officers are trained to neutralize the shooter as quickly as possible and only deal with the injured victims when this goal is achieved. In addition, patrol officers are better equipped and according to medical guidelines of the US military trained (Tactical First Aid) , as the injury pattern of school shooting victims are comparable to those of soldiers in combat. Improved coordination with the fire brigade and rescue service has also meant that injured people can be rescued and cared for more quickly. The new guidelines have already proven successful in several rampages: While the rampage at Columbine High School lasted almost an hour, most rampages are now ended within minutes.

"Columbine Effect": Influence on later gunmen

There has been a significant increase in school shootings since the rampage at Columbine High School . While there had been a total of 45 school shootings in US schools from December 30, 1974 through April 20, 1999, the Parkland school massacre on February 14, 2018 was the 208th school shootout in the United States, according to USA Today States since Columbine. Up until 1999 such incidents had occurred almost exclusively in the USA, but after the internationally sensational act by Littleton, the phenomenon also suddenly spread worldwide. Experts attribute the increase to copycat criminals who take the Columbine rampage as a model or want to surpass it. Often it is about young, mentally disturbed men who feel bullied, ostracized or misunderstood and in this way want to take revenge on society or gain recognition. For them, the Littleton school massacre has become a myth and cultural script . Many of the later gunmen said they identified with the perpetrators of Columbine, admired them or were inspired by them. This is why a “Columbine effect” is often used.

Research conducted by ABC News found that as of October 2014, at least 17 rampages and 36 foiled attacks on educational institutions had been shown to have been inspired by the Littleton school massacre in the United States alone, including the 2007 Virginia Tech rampage and Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. As of November 2015, more than 40 people in the United States had been charged for planning a Columbine-style act, according to CNN . Mother Jones magazine identified over 100 cases of counterfeiting in the United States as of April 2019, including the Parkland and Santa Fe school massacres (2018); Of the 74 acts of counterfeiting that occurred in the period up to October 2015, 53 could be prevented in the planning stage, and a total of 98 people died in the completed acts. Outside the United States, the rampages of Erfurt (2002), Emsdetten (2006), Jokela (2008), Winnenden (2009), Kerch (2018) and Suzano (2019) are among the acts that were influenced by Columbine.

It is noticeable that the number of copycat acts increases around the anniversary of the rampage at Columbine High School. On the 7th anniversary on April 20, 2006 alone, ten planned acts were prevented in time in the USA. Shortly before the 20th anniversary, Columbine High School and other schools in the Denver area had to be temporarily closed because the authorities assumed a specific threat from a potential copycat offender. The manhunt for the armed 18-year-old, who is said to have been "obsessed" by the Columbine rampage, ended on April 17, 2019 when the police found her dead - the person wanted had taken her own life. The Columbine perpetrators themselves said beforehand on the basement tapes that they would inspire copycat criminals and believed that their act would start a "revolution".

reception

Media coverage

With the rampage at Columbine High School, school shootings became a media phenomenon. After the OJ Simpson Chase in June 1994, the act was the second most covered live news event in the United States of the 1990s. According to CNN, it was the US news with the highest viewing figures in 1999, and in a poll by the Pew Research Center in the same year, 92 percent of US citizens surveyed said they were watching reports on the rampage. The act thus generated greater public interest in the USA than the US presidential elections in 1992 and 1996 or the death of Lady Diana (1997).

The news of gunshots at Columbine High School spread across every news network in the country in half an hour, and many entertainment networks paused their regular programming to go live to Littleton. CNN ended its coverage of the NATO attacks in the Kosovo war at 11:54 a.m. ( UTC − 6 ) and reported from Colorado without interruption until the evening. It is estimated that there were up to 500 reporters, between 75 and 90 satellite broadcasting vehicles, and 60 television cameras from numerous US and 20 foreign television crews on site. The rapid arrival of the media was due to the fact that many reporters had been in nearby Boulder on the day of the incident to report on the latest developments in the JonBenét Ramsey murder case . Cameras filmed the refugees from the school, reporters interviewed shocked, crying pupils and television crews positioned themselves in front of the hospitals in the area to document the arrival of the victims to be treated. Since the emergency lines were always manned, some students who were still hiding at school called the broadcasters, whereupon they were interviewed live on television. A television camera captured the image of Daniel Rohrbough's body from a helicopter circling over the school. Another shot showed a sign reading “1 BLEEDING TO DEATH” that students had placed in one of the school windows to alert rescue workers to the critical condition and whereabouts of the dying Dave Sanders. The case of the seriously injured Patrick Ireland from the library window into the arms of rescue workers was also televised live.