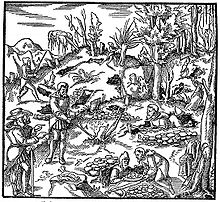

Mining and metallurgy in the Odenwald

The mining and metallurgy in the Odenwald extended documentably over a period of about 1200 years. Before that, the Romans had already mined rocks. The smelting of iron ore found on site can already be proven for the Heiligenberg for the early La Tène period (5th and 4th centuries BC).

The peak of mining work was reached in the 16th and 17th centuries up to the Thirty Years War (1618–1648). The few then decorated mountain - and hammer mills were in the course of industrialization and mainly because of not sicherzustellenden supply of metallurgical plants with coal not hold also suffered the mines at all times from problems with water leaks. In the second half of the 19th century, most of the hammer mills had to stop operating. In the same period up to the First World War , however, there was a brief revival of activities in mines. Today there are only a few evidence of the mining history of the Odenwald.

Mining areas and ancient mining

Due to the geology of the Odenwald , two mining areas are fundamentally different. In the mountain road adjacent crystalline Odenwald were silver , lead and copper mined, besides still different rocks. To the east of it in the sandstone Odenwald, however, mainly iron ore and manganese were mined, and barite mines are also known here .

Quarries were operated in Roman antiquity, and numerous remains of work pieces testify to this work, especially in the sea of rocks near Reichenbach .

swell

The oldest documented mention of mining in the Odenwald comes from January 20, 773. In the description of the borderline of the Mark Heppenheim , which was made on the occasion of a gift from Charlemagne to the Lorsch monastery , it says that the border is from Bergstrasse via the town of Winterkasten run, go over the Neunkircher Höhe and from there to the "middle Arezgrefte", ie ore mine. The location of this ore mine has long been disputed in the literature. Today it is assumed that it was one of three ore mines whose relics can be found on the upper Brombach at the foot of the Erzberg (484 m) in the district of Brombach (Fürth in the Odenwald) .

There was no evidence of mining for more than 200 years. Around the year 1000 a silver mine near Weinheim was mentioned that belonged to the Lorsch monastery . Probably around 1094 a document was written in which an annual transfer of iron consumer goods from the monastery courtyard to the monastery on the Heiligenberg was mentioned. The naming of the boiler smiths is interpreted as an indication of a continuing existence of ore mines. Gottfried Ludwig Klein, the personal physician of the Counts of Erbach, mentions a flourishing mining industry in the 13th century in his De aere, aquis et locis agri Erbacensis, published in 1754 on the basis of no longer existing documents.

A document from 1291 mentions Grube Marie in the Kohlbach near Hohensachsen , the then Count Palatine near the Rhine , Ludwig the Strict , bought it from the Strahlbergers and at the same time transferred it back to them as a fief . There are still files known from 1441 on mining in the Kirch-Brombachs area , which suggest that mining had existed for a long time. An entry in the interest book of the Schenken Georg von Erbach from 1450 reports a share in a tithe "on the mountain". The document situation only improved in the second half of the 15th century.

Mountain Regulations

The year 1472 is important for the mountain regulations as far as they concern the Odenwald. Three Mountain Regulations were issued this year. Once the first Kurpfälzische Bergordnung from 1472 , the forerunner of the great Kurpfälzische Bergordnung from 1551 . Then a mountain order, based on it and also in Electoral Palatinate, regarding mines in the Otzberger Land. At that time this area belonged to the Electoral Palatinate . The third is the Annelsbach mine clearance , the archive in Wertheim is in possession of a copy of these early mining regulations. At that time Annelsbach was owned by the Counts of Wertheim because of its membership in the Breuberg domain . However, this mine clearance essentially follows both the Electoral Palatinate mountain regime and the Breuberg regime. Even the taverns of that time, from 1532 Counts of Erbach , issued a mountain ordinance in 1512, but this is no longer preserved or handed down.

Annelsbach mine clearance from 1472

In the 16 sub-items of the Annelsbach mine clearance , the seven people who wanted to mine at the site are initially named, Annelsbach was called "Onolspach" in the spelling at the time. Wilhelm Graf zu Wertheim was the exhibitor of the order. This is followed by the sections with the assurance of safe conduct for those involved, then the actual granting of the mining right, the regulation regarding the tithe , the reservation of the separate permit to smelt the ore found, damage settlement, regulations for the felling and the transport of construction, Carpentry and cabbage wood and a renewed assurance of safe conduct for the miners, carters and rear passengers . After the provision that shares in the mine may only be sold among miners, the following six sections deal with regulations that concern the mining court , the mountain judge, lay judges, clerks and measurer as well as their remuneration. The mountain court is expressly granted only lower jurisdiction , not blood jurisdiction . The Bergordnung concludes with an oath and the date of issue: "According to our dear lord the birth of Dusent four hundred and then in the second and seventieth year / on the Tuesday after Saint Margaret's Day of the holy virgins" (July 21, 1472). In terms of language, the Mountain Regulations are clearly understandable and generally a good example of such mountain regulations.

Earliest mines

A book from the middle of the 18th century shows that mining in the Odenwald would flourish in the 13th century. It says: “ Nostrae ferri fodinae ac officinae ferraria periantque sunt. Docet enim memoria publica seu tabularium, iam seculo XIII easdem florit . ”(Our ore mines and iron smiths are very old. A record teaches that they flourished as early as the 13th century). The mining was done by sinking vertically into the earth and conveying the ore found in buckets with simple reels . If the site was exploited, a new shaft was simply driven a little further away. When the old shafts collapsed, pings were created , which can still be found in the field names today, for example “Erzlöcher” or “Berglöcher”. Based on the field names as the oldest mining sites, Bad König , Momart , Langenbrombach and possibly the Mossau valley can be considered examples of the earliest mining activities in the central Odenwald.

Michelstadt-Steinbach

To the west above the Steinbach district of the town of Michelstadt along the B47 in the direction of Rehbach on the northern slope side, there are spoil heaps from early mining in several places. Remnants of tunnels were also found during research in the late 1990s. Since the woods used were not suitable for dendrochronology , it was birch and fruit trees, the C14 method was used, which, however, yielded unclear results. Two periods were defined: on the one hand the 14th and on the other hand the 16th century. Due to the document situation and the type of construction of the tunnels, it can be assumed that the 14th century was more likely than a later period in which this mining area was formed. In the vicinity of the spoil heaps there is also a shaft penguin, which dates back to the 14th century due to the ease with which it was extracted. In the 18th century, attempts were made to start mining at this point, but unsuccessfully. In 1910, the remains of ancient Roman buildings were found in the same area. Since the found foundation walls are extremely untypical for a villa rustica , there is speculation that these buildings could already have something to do with mining at this point, but so far without any written or archaeological evidence of the connection.

First forest smiths and hammers

The earliest form of further processing of the ore in the Odenwald happened in forest forges . The metal was melted out in simple melting furnaces and forged into the desired equipment on the spot. The ovens are often found on slopes because the updraft at such places could be used for higher temperatures inside the ovens, following the principle of the racing oven . Early examples can also be derived from field names such as "Schmelzberg", "Schmelzbuckel" or "Hüttenbuckel"; corresponding names can be found for Weschnitz , Klein-Gumpen , Unter-Easter and Groß-Gumpen . In the first half of the 16th century, forest smiths and forest blacksmiths were explicitly named, sometimes by name, for Mossau (1512), Hiltersklingen (1512 and 1517) and Etzen-Gesäß (1541). The name Hüttenthal was first documented in 1366. The ironworks that gave it its name must have existed at that time. The associated remains of the ore wash could still be seen until 1764.

In the further course of the 16th century, a large part of the Odenwald hammer operations came into being. Only an earlier hammer loan in the second half of the 15th century is documented, located in the Breuberg domain. Whether or how long the hammer worked is not known. The attempt to open up a pit appears in a calculation from 1477/78.

Blacksmiths, mines and hammer mills

In the Odenwald there were numerous small mines with the associated smelting, hammers and forges, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries. A "Directory of the whole Morspergs [...] in anno 1576" shows how high the wood consumption was for the corresponding plants, especially for the extraction of charcoal by charcoal for the smelting furnaces. It says of a forest near Mossau: "This forest has also been cut down and charred in it.", Further: "The ninth forest [...] belongs to those in Bockenrodt, Rorbach and Ertzbacher Hueb and is alone in the Ambt Reichenbergk [ …] A tree cannot be used every day ”. The forests only recovered from the enormous demand for wood in the 19th century. To this day there are open spaces in the forest, so-called “cabbage plates”, in particular on and around the Morsberg , leveled areas on which coal piles were operated.

The Anna-Elisabeth-Grube

The Anna-Elisabeth-Grube east of Schriesheim is an old silver and vitriol mine that has been in operation for over 700 years with preserved outdoor facilities from the 18th century. The mine was first mentioned in a document in 1291, four mining orders from 1507, 1511, 1528 and 1551 are known. Curiously, the Saxon shift supervisor and mountain rider Gregor Hirsch from Schneeberg is mentioned as the first mine owner , which means a reversal of the mining hiking activity , since Baden and Hessian miners followed the mountain screeching into the Ore Mountains to mine the silver deposits discovered there at the beginning of the High Middle Ages . From 1779, after the old tunnels were rediscovered from 1530, they were mined for iron and copper vitriol ores. In 1781 a brewhouse was built for ore processing . In 1817 the mine was closed. Several attempts at new mining activities ended in the sand, until finally in 1926 the abolition of the mine field "Anna-Elisabetha" (only named in 1894) took place. After 1945 all accesses to the tunnels and shafts were filled. In 1985, on the initiative of the citizens of Schriesheim, work began on building a visitor mine, after the outdoor facilities and the mine were placed under monument protection on the initiative of the group in the same year . In 1987 a framework operating plan was drawn up for the construction and operation of the visitor mine. In 1989 the visitor trail was put into operation. In 2002 more than 100,000 visitors were welcomed.

Gunsmiths at the Roten Kandel

At the Roten Kandel , a mountain near Erzbach , numerous traces of mining in the form of pings, slag heaps, remnants of smelting furnaces, etc. were found during the First World War . What was unusual, however, were the finds of cast and forged weapon parts. There were two iron handle bushes , one of which was a failed casting, the other had been successful, but it still had to be drilled out. A so-called powder chamber was also found. This is a hollow round piece forged together from several parts, which is provided with a handle. In the medieval artillery it was filled with powder and clamped into the mount behind the gun barrel. After ignition, it could be exchanged for another, previously filled powder chamber, so it had the function of increasing the cadence . Other remains of mining activities have also been found. An investigation in 1930 came to the result that this place was an armory from the 13th or 14th century that was owned by Erbach.

Lower hammer at Michelstadt

The former lower hammer near Michelstadt possibly dates back to 1554. In a hall book , which is in the archive of the Counts of Erbach-Fürstenau in Fürstenau Castle , a "smelter" is mentioned. A document from 1572 names a hammer factor Feuchter. He should take care of the infidelity that occurs regarding the ore mines and the hammer. Later miners and experts in the iron industry from Tyrol and Hungary were called to the Odenwald. Heinrich Liveherr is mentioned on his epitaph in the town church of Michelstadt in 1613 as the “factor” of the hammer. An entry in the interest book of the nearby Steinbach monastery from the last quarter of the 16th century still mentions "Wurtenburgisch trade union". Wood and forest purchases for this hammer mill are known from 1609/10 and 1612/13. In 1615 the work was pledged by the Counts of Erbach, from the same year an order is known to a pastor to give 500 guilders to the “Eyßenwerk towards Fürstenau”. In 1623 new buildings were erected, after which the Thirty Years War ruined all further efforts and the hammer mill was completely "ruined".

It was not until 1650 that the hammer was awarded again. In 1660 Conrad Ensinger leased the hammer, and from 1668 he had the so-called “manor house” built. It was a stately, thirteen-axis, two-story building with a hipped roof . According to the description from the monument topography of the Odenwald, the manor house was "significant as one of the oldest industrial residential buildings in Hesse". The building was demolished in 2008 against the resistance of the Lower Monument Protection Authority and numerous local historians. After Ensinger's death, his wife continued to run the hammer until her death in 1693. In 1699 the hammer was pledged to Nikolaus Salzwedel from Frankfurt . In 1727, the "admodiator" of the hammer mill Mathias Benjamin Fahlmer died, his gravestone is preserved in the old cemetery chapel in Michelstadt. In 1737 24 quintals of iron were processed per day . In the 18th century, the hammer was leased several times until a wire drawing shop was finally set up in 1858 with the abandonment of one of two blast furnaces. The blast furnace operation was closed several times, for example in 1864 and 1869, but then restarted in some areas. In 1864, 125 tons of ingots of iron were processed, the amount of cast iron was 165 tons. In 1882 the old buildings were finally demolished, and in 1900 the forging activities were also discontinued.

At the grace of God in Ober-Ramstadt

The mine for God's grace near Ober-Ramstadt is mentioned for the first time in a document from 1506, two Dutchmen were enfeoffed with it. As early as 1512 there was another loan, including to a miner from the mining town of Schwaz in Tyrol. A year later, however, this Lupold wage declared that it had "blocked itself". The mine itself was supposed to be digging for silver. After decades of standstill, mining activities were not resumed until 1577, with ore samples showing silver and copper. In addition to taking samples, as is proven by a number of invoices, a dowser with a divining rod was also used. Two years later, Landgrave Wilhelm IV of Hessen-Kassel commented on this in a letter. In 1578 the mine was measured and all shafts and tunnels were precisely named. The lower floor was at that time at a depth of about 18 meters. An exact inventory of the mine is also from the same year. From 1580 there is still an account of the remuneration paid for the miner, which was handed down to the tusks, pump servants and reel servants.

The main problem with the mining, which is worthwhile because of the high silver content, was the strong water ingress into the mine. Despite numerous attempts, it was not possible to get the water problems under control. In 1583, the mountain master Hans Stadler, also from Tyrol, died, for whom no successor could be found. Mining ceased altogether just three years later. In 1598 the personal physician of Landgrave Ludwig V , Dr. med. Joachim Strupp , enfeoffed with the mine. Despite repeated attempts in the 16th and 17th centuries, no new operation came about. One of the last mining rights was granted in 1878 under the name of Grube Anna , but operations were no longer started. In 1907 the remains of the mine were examined; many of the medieval routes and tunnels were still there.

Wald-Michelbacher Hammer

The history of the hammer in Wald-Michelbach , also called Huy'scher Hammer , goes back to the year 1565. Since Wald-Michelbach belonged to the Electoral Palatinate, a certificate relating to the hammer was issued by Elector Friedrich III. issued on August 20, 1565. Hans Caton was called the owner of the hut. The hammer appears to have been operated successfully, as evidenced by documents of extensive timber purchases. His son, Johann Caton, continued to run the hammer. He built the magnificent Renaissance building of the hammer around 1600. Caton probably died after 1623 without children of his own.

The hammer lay broke during the Thirty Years' War, only then was it sold to David Steiger from Basel . He received a number of privileges, but he exchanged the hammer mill for another in 1657. The new hammer owner was the aforementioned Conrad Ensinger, who later also ran the Lower Hammer in Michelstadt. His widow also continued to run the hammer mill in Wald-Michelbach, according to a source from the 18th century, it consisted of two works and also operated gun casting . The annual rent was set at 30 guilders. He was succeeded by Johann Ezechiel Haffner. The operation was probably successful in that in 1701 another iron smelter was set up in Ober-Waldmichelbach. Nevertheless, Haffner died impoverished, his "unwary son" is said to have been responsible. The hammer was sold again in 1727 to the Mannheim merchant Johann Heinrich Weyl, but in 1739 he had to let his creditor Baud use it. After Weyl's death in 1747, a 23-year legal dispute ensued between his descendants and those of Baud, which was only ended by a settlement in 1770. Ultimately, Weyl's daughters sold the hammer to Adam Schmitt and his son in 1776, who in turn sold it to Johann Wolfgang Renner in 1779. He had the business renewed for the high sum of 12,000 guilders and ran it very profitably. The new house at Hammer was also built in 1779. A stone tablet shows the year and Renner's monogram. His son continued the business, then a Baron von Riedheim and Christian Huy from 1853, which is where the hammer got its nickname. In 1865, like many others, the hammer operation was stopped and the building was converted into a mill.

Lead and later copper mine near Reichenbach

The start of a lead mine near Reichenbach can be set to 1513 through a loan. In 1530, Elector Ludwig V of the Palatinate enfeoffed the Erbacher taverns with the right to dig lead. The already mentioned smelter Hans Caton received permission to dig copper. However, the mine was only in operation from 1590 to 1593, and here, too, the problems with penetrating water could not be solved. The mine reached a depth of 22 meters. A drawing of the 9 meter high waterwheel reel from 1592 is still preserved as a photograph from 1936, i.e. before the Erbachisches Archiv was destroyed in 1944. In 1600 a company was founded to start the mine again, but this attempt ended unsuccessfully in 1604. Another award is known from 1619. The Thirty Years' War probably ended all further efforts here as well. In the later 17th century there were two attempts to mine copper and, in the meantime, silver, but both failed.

From 1841 copper mining started again with two new shafts. The work was initially successful, so that another shaft and various tunnels were created, but after a few years the work was stopped. This time the smelting of the copper-bearing rock did not succeed to a satisfactory extent. Another five attempts, the last in 1935, were also unsuccessful.

More mines and hammers

Another iron ore mine existed in Weschnitz. It was in operation from 1546 to 1708 at the latest and was reopened in the 19th century. In the 1950s, the remains of a small mine were found in Ober-Easter , which was documented in 1579. There was a copper mine in Roßdorf for three short periods, roughly from 1500 to 1506, then from 1577 to 1586 and much later from 1858 to 1860. Mines in Großwallstadt , Großostheim , Mömlingen and Eisenbach are known further east .

The hammer mill in Hirschhorn existed from 1651 to around 1760. In 1734 a hammer mill was built in Aschbach , before that there was a smelter from 1763. Melts and hammers also existed in Ober-Klingen , Nieder-Modau , Wahlen and Gammelsbach . For Rehbach the existence of a blast furnace from 1576 to 1578 is known. Remnants of the wall found in the village lake in 1957 were interpreted as remains of the ore wash. These remains of mining were also removed without need and against protest in 1998 on the occasion of desludging.

Later mining and hammering activity

In the late period of the Odenwald mining, some hammer operations and mines were still being built. The downfall of mining activities could not be stopped. This was due on the one hand to the emerging industrialization and the resulting competition from large companies in the iron and steel industry, on the other hand to the infrastructure of the Odenwald, and there was no guarantee that the smelting works would always be adequately supplied with hard coal.

A few new mines were built, which is due to the increased demand for manganese in the 19th century. During the First World War, medieval slag heaps were cut down on a large scale and smelted again. The medieval technique could not melt more than 26% of the iron content from the ore, in the case of manganese even only 7.7%. The repeated smelting was a profitable use of the slag.

Late hammer companies

The iron hammer in Ober-Ramstadt goes back to 1688, the hammer and smelting right was awarded to Christian Will in that year. The smelter was abandoned as early as 1708, the hammer operation suffered from a temporary iron deficiency. Plans, measurements and inventory lists from the 18th century are still available. The last tenants were Frankfurt merchants, most recently Johann Jakob Friedrich in 1788. The hammer was shut down in 1817.

A hammer mill in Schöllenbach had existed since around 1700, possibly even earlier. The first hammer owner, Georg Schick, handed the business over to his two sons in 1718. In 1748 the plant was taken over by Johann Michael Rexroth. In 1757 the hammer went to the brothers Johann Ludwig and Johann Adam Rexroth. Her descendants ran the business until 1839, when Johann Ludwig Rexroth took it over that year. The hammer operation was stopped in 1870 and the plant was converted into a sawmill .

Other late hammers, all from the 19th century, existed in Ziegelhausen , Schönau , Eberbach , Mühlhausen and Weilbach . Some cast iron stove plates from the latter hammer factory are still available. These plates, made around 1830, are now in the local history museum in Amorbach .

Late mines

In Michelstadt, iron ore was mined, but the exact start of mining is not known. The mining areas were in the area of the Hermannsberg and the Kirchberg. From this time there are still mining lamps , one of which bears the year 1800. Mining was given up in 1830, also here because of water ingress.

The increased demand for manganese in the second half of the 19th century led to a small revival of mining at already abandoned mines or in their immediate vicinity through the introduction of new shafts and tunnels. In Bockenrod , a French company operated two mines, Gottfried and Juno , in 1898 ; it also owned the Juno mine near Rohrbach and the Fortuna mine near Erzbach . Mines near Weschnitz, Mittel-Kinzig and Waldmichelbach also emerged or took over existing facilities.

Barite mining

Heavy spar mining in Klein-Umstadt

From 1839 to 1931 heavy spar was mined underground in Klein-Umstadt . The area included about the area of today's sports field of TSV 1909 Klein-Umstadt eV . and moved behind today's Werndelinus elementary school to today's fruit tree meadows from the northern part of the village on the ridge in a south-easterly direction ⊙ . The older mining area was located southeast of the old town in the ridge of the incipient Odenwald on both sides of today's K105 road towards Radheim ⊙ . In 1858 two pits were named, which annually about 30,000 Ctr. (i.e. 1500 tons). This was about two thirds of the total mining in the Odenwald (in addition to two other barite mines in Ober-Kainsbach and Ober-Easter ). At a cost of 10–15 kr. , The hundredweight of ground rock was sold for around 40 to 50 kr. (Without or with packaging). In 1869 it was 2500 tons of annual production, generated by only eight to ten workers. The veins in the district were sometimes up to nine meters thick, but repeatedly interspersed with shear zones. The pits were meters deep and 85 drilled . In total, around 650,000 tons of rock containing barium were mined in the Umstadt area over the entire period . At least twelve corridors have been opened up in just under 100 years. From the mountain land registers we have come down to the following mines: iron ore mine luck and happiness I, iron ore mine Adelheid, iron ore mine Eisenrahm, Schwerspatbergwerk Kleestadt, Schwerspatbergwerk Edelweiss, iron ore mine Cunegonde, iron ore mine Oberweißburg, Schwerspatbergwerk Klein-Umstadt and Schwerspatbergwerk endurance. Today there are hardly any traces of mining to be found, only the spoil heaps can still be guessed in the area and small readings are still possible. In the educational trail "The Little Mountain Road - Landscape, People and Environment in Klein-Umstadt" as part of the Geo-Nature Park Bergstraße-Odenwald , the history of mining and the curiosity of the "Barite War" is explained in two information boards (see Klein-Umstadt # The UNESCO Geopark Educational Trail ).

Klein-Umstädter barbar war

The disputes had their origins in mining law . While all important ores basically belonged to the sovereign and not to the landowner (" Berg Freiheit "), barite was a "native" mineral because of its initially minor importance. While some pits had been negotiated with the landowners after negotiations about lease rights and had been digging since 1839, the Mainz citizen Karl Heck circumvented this and had the sovereign issue a prospecting license for iron ore. With this he could of course also mine the “inferior” barite in his pits. From a purely legal point of view, he even had a claim to the deposits in the pure barite mines, as the sovereign permit took precedence over the rights of the landowners. Between 1850 and 1860 there were violent disputes about barite, which, after damage to property, also led to “hitting and stabbing” in the pits. Only after this escalation did the mining authority issue a warning and Heck concluded a contract with the community. After 1879, the newly installed pumps were no longer able to cope with the penetrating groundwater and mining was not resumed on a large scale until 1906. In 1927 barite was finally recognized as a mined mineral by state law. A field railway was used at the pits , which brought the heavy spar for loading to the Klein-Umstädter station of the Odenwald Railway, which had existed since 1870 . Mining in Klein-Umstadt was stopped as early as 1931. Today there are several guided tours along the Geoppath every year.

Schriesheim heavy spar mining

In the southern Odenwald, along fissures in the Schriesheim formation , heavy spar was mined in the 19th and 20th centuries. The remnants of these can be seen from the Pappelbachtal over the ridge of the Obere Griet to the Weittal (which was first developed here in 1800 by mining) like a string of pearls. Cracks in the earth, called pinging , and trenches in various places indicate the former aboveground and underground mining.

In the period after 1823/24 the spar pits were particularly productive and brought annual yields of around 5000 guilders. Examples are the years 1824 to 1827, when the amount of spar recovered of over 1250 t was almost exclusively shipped by ship to the Netherlands, where the barite was used for the manufacture of paint. In 1939, Schriesheim's heavy spar mining was also discontinued because all of the heavy spar had been mined. After the closure, only rock material was extracted from the old trenches on the Upper Griet to secure the underground cavities. The so-called Spatschlucht , which was created by the surface mining, has been a natural monument since 1937 due to its importance as a cultural-historical and geological testimony .

Below the Spatschlucht, in the former Wilhelm tunnel, heavy spar was also mined over a long period of time. The tunnel, which is not quite 140 m long, is no longer accessible today. A notice board reminds of previous mining activities. Since July 2000 a seismograph has been set up to record earthquake waves in a rock niche in the granite of the tunnel. It is part of the state-wide measuring network of the LGRB with currently around 50 measuring stations in Baden-Württemberg . To get to know the history, an approx. 8 km long hike along the Schriesheim loop of the Geopark path Weinheim / Schriesheim of the Geo-Naturpark Bergstrasse-Odenwald is recommended .

Gypsum mining

Since the investiture of Adelsheimer mayor Ernst on 27 July 1847 by Grand Duke Leopold of Baden with a mining claim on the Neckar slopes at Obrigheim in the Odenwald is gypsum mined. Today the pit is the largest and also the oldest continuously operated underground gypsum mine in Germany.

After many changes of ownership, in 1905 the mine went to the Portland-Cementwerke Heidelberg and Mannheim , today's HeidelbergCement AG . Currently, with over 20 miners working in one or two shifts, around 300,000 t of raw gypsum are extracted per year.

The building material for mortar and gypsum boards, in the ceramics industry , as an additive in the cement industry and not least as chalk needed and versatile raw material gypsum and its history can today in five stations on a plaster trail be explored. Visiting the gypsum pit is possible after registering on the internet.

The gypsum tunnels were used ingloriously during the Second World War . The confiscated tunnels ( Friede und Ernst ) were used for a secret National Socialist project with the cover name Goldfish and a concentration camp was set up for arms production. It was the second largest arms relocation project of the Second World War, the Berlin aircraft engine plant Genshagen of Daimler-Benz AG . From 1944 onwards, around 10,000 people from 25 European countries had to toil here as work slaves. After the war, nobody wanted to remember "Operation Goldfish" at first. Gypsum was extracted again in the tunnels. But the company "Goldfisch" has also left traces on the surface. The history trail, which was built in 1999 and is divided into ten stations, aims to preserve this story as a memory for the descendants.

Wayside shrines and tombs in memory of hammer people

In the Odenwald there are two stone wayside shrines and a stone cross that are reminiscent of hammer people. A Gothic wayside shrine near Zell in the Odenwald shows a hammer on the shaft, the figure in the attachment is interpreted as Saint Leonhard , the patron saint of the hammer mill. The so-called Mossau picture shows hammer and pliers in an inclined coat of arms on the shaft. It dates from the 16th century. The Schöllenbacher Kreuz also shows hammer and pliers on the crossbar.

Tombs and an epitaph of four hammer lords are still preserved . The epitaph for Heinrich Liveherr is located in the choir of the Michelstadt church. The text of the double epitaph, next to it for the bailiff Scherff von Scherffenstein, reads: “The honor and praise of Heinrich Liveherr der Zeit Grävl. Erp. Hammer FACTOR near Fürstenau was born in Colberg in Pomerania on July 15th, Ao 1585 Hatt with his Ehlichen Hausfrawen Dorathea Elisabet Scheferrin, who fell asleep on February 9, Ao 1613 in the Lord. 1 son and 1 wicked is blessedly different than ... to whom God has mercy. “The date of death of the live owner is not entered. He died in 1626. The reason is that Liveherr moved to Seeheim in 1614 , where he married again and had other children. When he died, the epitaph was probably forgotten.

The grave slab for Mathias Benjamin Fahlmer is located on the northern outer wall of the Holy Cross Chapel in Michelstadt. The inscription reads in the extract:

“MY READER! THOSE WHO HAVE CHANGED CORRECTLY BEFORE THEM COME TO PEACE AND REST IN THEIR CHAMBERS HERE. ALSO STAND AT THE CALM CHAMBER OF A FAITHFUL LOVER OF JESUS WHO IS FAITHFUL IN LIFE BEFORE GOD AND SINCERELY WALKED BEFORE HIS NEXT ONE WITH A LITTLE. IT WAS DERWEYL WOLEDLE AND ADJUSTABLE MR. MATHIAS BENJAMIN FAHLMER BEEN CENT-COUNT AT MICHELSTATT AND ADMODIATOR OF DASIGEN EISENHAMMERWERKS. HE WAS BORN AT BUKOW IN THE MARK BRANDENBURG ANNO MDCLVIII D. XXI NOV AND DIED ANNO MDCCXXXIV THE VIII AUG. SO HIS AGE WAS LXXV IAIR VIII MONTH AND XVI DAY. "

On the north wall of the cemetery chapel in Beerfelden was the grave slab for Jakob Valentin Haffner, the son of Johann Ezechiel Haffner. It is not clear from the inscription whether he was the son who was responsible for his father's troubles. It reads in extracts:

“HERE REST IN GOD THE WEYLAND NOBLE V EIGHTBARE MR. IACOB VALENTIN HAFNER HOCHGRAEFL ERBACH HAMER ADMODIATEUR AT GAMMELSBACH HE WAS DRILLED AT WESCHNITZ AO 1702 D 7TH JULII DIED AT GAMMELSBACH AO 1735 DAY 2TH AUGUST 14TH, 33 AD. "

In the Carmelite monastery church of the Annunciation in Hirschhorn, the tombstone of Wolfgang Carl Scheberle can be found in the St. Anna chapel. It says:

"ANO 1718 ON APRIL 3, THE HONOR VESTE UNDER THE NEIGHBORHOOD HER WOLFGANG CARL SCHEBERLE HER DIED THE HIGHLY IRON HAMER HIS AGE 68 JAR V 2 MONT."

See also

literature

- Philipp Buxbaum: Michelstadt in words and pictures , Börsig-Verlag, Darmstadt 1956

- Friedrich Mößinger: Mines and iron hammers in the Odenwald (= writings for local history and home care in the Starkenburger area. Issue 21/22, ZDB -ID 971701-8 ). Publishing house of the "Südhessische Post", Heppenheim 1957.

- Friedrich Mößinger: An Odenwald ore mine of the eighth century. In: The Starkenburg. Vol. 30, No. 4, 1953, ZDB -ID 244793-9 , pp. 13-14.

- Erwin Nickel : Odenwald. Vorderer Odenwald between Darmstadt and Heidelberg (= collection of geological guides 65). 2nd, expanded edition. Bornträger, Berlin / Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-443-15045-4 , pp. 56-60.

- Georg Dascher: Traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. In: Odenwald-Heimat , supplement to the Odenwälder Echo , 4, 2008, ZDB -ID 972211-7 , pp. 13-15.

- Jens-Uwe Eder, Jochen Babist: Avoiding damage to mining relics by using alternative wood- bridging technology using the example of the Weschnitz-Rohrbach mining district (municipalities of Fürth and Reichelsheim, Odenwald, Germany). Online publications of the Geo-Nature Park Bergstrasse-Odenwald; first published under the title: Avoiding Damage to Mining Relics by Means of innovative Forestry Methods illustrated by the Example of the Mining Region Weschnitz-Rohrbach. In: Jacquo Silvertant (Ed.): Recognition, Investigation and Preservation of Ancient Mining Relics. 4th International Symposium on Archaeological Mining History, Reichelsheim / Odenwald, Germany 2009. Institute Europa Subterranea, Maastricht 2009, ISBN 978-90-79491-07-0 , pp. 110–129 ( online ).

- City of Michelstadt (ed.): 900 years of Steinbach - chronicle of a village , MKK Verlags-GmbH, Michelstadt 1995

- Klaus Fahlbusch, Werner Jorns , Gudrun Loewe and Josef Röder: The Felsberg in the Odenwald. With archaeological and geological contributions on the formation of the rocky seas and the technology of the Roman granite industry. Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0792-5

- Hans Taschen: "A brief overview of the mining, metallurgy and saltworks in the Grand Duchy of Hesse" , Darmstadt 1858, Hofbuchhandlung Verlag G. Jonghaus

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Marzolff, Uwe Gross: Between Merkur and Michael: The Heiligenberg near Heidelberg in the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages , in: Heiko Steuer, Volker Bierbrauer (ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic (supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Antiquities; 58), Walter de Gruyter Verlag, Berlin, 2008, pp. 121–163, ISBN 978-3-11-020235-9 . online , accessed July 3, 2014.

- ↑ It is a copy of a Carolingian document in the Lorsch Kopialbuch from the 12th century, the Codex Laureshamensis . It should have taken place around 1170. See Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , P. 13.

- ↑ Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , P. 13.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 8.

- ↑ Codex Laureshamensis, Chronik 140, Reg. 3627, after Eder, Babist, p. 4.

- ^ Gottfried Ludwig Klein: De aere, aquis et locis agri Erbacensis atove Breubergensis, largi Odenwaldiae tractus , Frankfurt 1754. Digitized

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 12.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 35.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 21

- ↑ a b c Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 38.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , pp. 35ff.

- ↑ Ludwig Gottfried Klein, 1754, cited in Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 21.

- ↑ Translated by Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 21

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 22.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 23ff.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , pp. 22/23.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 27.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 39.

- ↑ Winfried Wackerfuß: Cultural, economic and social history of the Odenwald in the 15th century. The oldest accounts for the Counts of Wertheim in the lordship of Breuberg, 1409–1484 , Breuberg-Neustadt: Verlag Breuberg-Bund, 1991, p. 147.

- ↑ Text partly in Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest forges in the area of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , P. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Mößinger: From the history of the Odenwälder Bergbau , in: Der Aufschluss, Zeitschrift der Vereinigung der Mineralogie und Geologie, special volume 2, 1955, pp. 75–81.

- ↑ Peter Levin: About a vein-like mineralization near Schriesheim in the south-western Odenwald , in: Der Aufschluss, Zeitschrift der Vereinigung der Mineralogie und Geologie, special volume 27, 1975, pp. 255-262.

- ^ Website of the Schriesheim visitor mine

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 26.

- ^ City of Michelstadt (ed.): 900 years Steinbach - Chronicle of a village , MKK Verlags-GmbH, Michelstadt 1995, p. 207.

- ^ City of Michelstadt (ed.): 900 years Steinbach - Chronicle of a village , MKK Verlags-GmbH, Michelstadt 1995, p. 207.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 41.

- ↑ Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , P. 14.

- ↑ Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , Pp. 14/15.

- ^ City of Michelstadt (ed.): 900 years Steinbach - Chronicle of a village , MKK Verlags-GmbH, Michelstadt 1995, p. 207.

- ^ City of Michelstadt (ed.): 900 years Steinbach - Chronicle of a village , MKK Verlags-GmbH, Michelstadt 1995, p. 207.

- ^ Philipp Buxbaum: Michelstadt in words and pictures , Börsig-Verlag, Darmstadt 1956, p. 65/66.

- ↑ a b Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 74

- ↑ Dr. med. Joachim Strupp. In 1598 he was enfeoffed with the mine in Ober-Ramstadt and a court ride on the market in Darmstadt, including freedom of the castle . Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt Best. E 12 No. 299/53.

- ↑ Bergassessor Sommer: The mining of Landgrave Georg I of Hesse near Oberramstadt in the Odenwalde. In: The ore mining . Zentralblatt für die Erzbergbau, December 1908, pp. 508-519 u. 536-545. Library of the Ruhr area Bochum, call number 8 b 73.4, 1908.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 78.

- ↑ Report from 1776, quoted in Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 55.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 56.

- ^ Reprinted in Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 51.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 79.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , pp. 84/85.

- ^ Nickel, Erwin: Odenwald - Vorderer Odenwald between Darmstadt and Heidelberg. (Collection of geological guides 65). 2nd ed. Borntraeger, Berlin 1985. p. 58

- ↑ Dascher, traces and references to early iron ore mines, smelters, hammers and forest smiths in the vicinity of the 517 meter high Morsberg. , P. 15.

- ↑ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 25.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 90.

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 92.

- ↑ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 100.

- ↑ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 102.

- ↑ Hans Taschen: “A brief overview of the mining, metallurgy and saltworks in the Grand Duchy of Hesse” , Darmstadt 1858, Hofbuchhandlung Verlag G. Jonghaus, p. 63

- ↑ Annual reports of the Grand Ducal Hessian Chamber of Commerce in Darmstadt , IV. Annual Report for 1867 to 1869, Darmstadt, 1869, p. 88

- ^ Archive information system Hessen ( Arcinsys Hessen ); Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt (HStAD); Property registers (Berg basic books) ( G 29 H ): a) Berggrund book Klein-Umstadt, Raibach and Kleestadt Vol I,. (With alphabetic owner register runtime : 1903-1990), b) Berggrund book Kleestadt and small-Umstadt, Vol I,. With alphabetic Ownership register (1904–1989), c) Mining land register Klein-Umstadt, Raibach, Groß-Umstadt, Vol. II (1931–1955)

- ↑ Geoppath, panel 10: "Barite War" in Klein-Umstadt (PDF file; 1.3 MB)

- ↑ The Kleine Bergstrasse - Landscape, People and Environment in Klein-Umstadt ( Memento from May 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 1.3 MB)

- ↑ (a) Theme park environment Baden-Wuerttemberg: The Spatschlucht in the wide valley near Schriesheim (Rhein-Neckar-Kreis) , (b) Odenwald website by Joachim Larger: From pingen, shafts and gorges: the Schriesheim heavy spar mining area and ( c) www.feldbahn-dossenheim.de: Schwerspattour ( Memento of the original from December 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Geopath Stones, Gorges and Legends Weinheim / Schriesheim ( Memento of the original from November 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file; 0.9 MB)

- ↑ Visiting the gypsum mine in Obrigheim .

- ↑ Neckarelz concentration camp memorial e. V. - Goldfish Path

- ^ Mößinger, Bergwerke und Eisenhämmer im Odenwald , p. 108.