Hadza

The Hadza (also Hadzabe , Hadzapi , Tindiga , Watindiga , Kindiga , Kangeju ) are an ethnic group in the central north of the East African state of Tanzania , whose number is estimated at around a thousand today. They are scattered on the banks of Eyasi Lake in the central Rift Valley , with a position of about 35 ° east longitude and 3 degrees south latitude , in proximity to the south Ngorongoro - protected area and in the adjacent Serengeti plane. This inaccessible and less fertile area of savannah and woodland, the size of which is given in the 21st century at around 4000 square kilometers or two thirds of this area, represents a final retreat from what used to be a much larger habitat.

The Hadza are traditionally hunters and gatherers and are one of the last near-natural communities to still use stone tools or to have used them in the recent past. In addition, they live in this original way in a region that is often referred to as the “cradle of mankind” and is in the immediate vicinity of important prehistoric sites (compare human tribal history ). For this reason, since the second half of the 20th century, they have been finding great interest among scientists who see them as a model ethnic group for questions in anthropology , human development and early human research .

In the meantime their influence by the modern age is growing . The number of members of the people who still follow the traditional nomadic way of life is estimated at a few hundred. Through a series of very long-term historical developments and also through modern social and economic changes, their way of life as well as their cultural and ethnic identity and existence are acutely threatened.

The name designation

Various names have been used for the Hadza in travel and specialist literature. Since the African languages were predominantly writtenless, written versions first go back to European authors, with German and English authors choosing different spellings according to the patterns of their mother tongues. In addition, as in many cases around the world, there are both own and external names by neighboring peoples, i. H. in this case by members of other language families.

Hadza is an own name and simply means "human being, human being". Hadzabe or Hadzabee is the plural form and Hadzapi ( Hadzaphii ) means "they are people". Hatza and Hatsa are German spellings from older times. Today, through the course of colonial history and Anglo-American research literature, the English spelling has prevailed.

Tindiga goes back to a word of Swahilisprache (in East Africa has long been considered the lingua franca or common language , and today as the national language of Tanzania is) watindiga, what "people / people of / from the swamp thorn plants" or something free "residents of the swamp thorn plant area" means and can be traced back to a large water source in Mangola. Kitindiga then denotes their language; Kindiga is obviously a variant form of the same from one of the local Bantu languages; Wakindiga would be a plural form (for the language families see prehistory below ).

Kangeju is an abandoned form of the name of unclear origin from the older German-language literature.

The English name bushmen was coined in colonial times for the traditionally very similarly living hunters of southern Africa (today the collective name San , which comes from the settled neighboring peoples of that region) was coined and borrowed into German as Bushmen or Bushmen . This expression was also carried over to the Hadza of East Africa and was occasionally used for it in German scientific literature until the end of the 20th century.

The Hadza themselves dislike such expressions of settled foreign peoples "because of their derogatory and discriminatory connotations " or "overtones".

The geographical framework: habitat and climate

The Hadza habitat has been narrowed to about a quarter of its original size in the last sixty years and before that it extended much further, especially in the west and south-west. It is estimated that it has shrunk by as much as 90 percent from its previous size over the past hundred years. Today there are four different areas in which the Hadza live during the dry season: west of the southern end of Lake Eyasi , between Lake Eyasi and the Yaeda swamp east of it, east of the Yaeda valley in the Mbulu highlands and north of the valley around the village of Mang'ola. They can easily move from one habitat to the next during drought. The westernmost area is accessed via the southern end of Lake Eyasi, which dries up first in the dry season, or via the escarpment of the Serengeti plateau on the north shore. The Yaeda Valley can also be easily crossed. During the rainy season, the Hadza live between and outside the described areas, as these are then difficult to access.

The Hadza way of life and subsistence economy (see below The traditional way of life ) is "closely linked" to the ecological conditions of the woodland and savannah landscape in which they live. Your Waldland- Habitat is from trees of the genus Acacia , Commiphora and Adansonia digitata (see below foraging ) dominates, is typically hilly and rocky, with scattered natural springs and seasonal streams. At the edges of Lake Eyasi and the Yaeda valley, the rocky hills merge into alluvial sand plains. Depending on the season, this area can be quite hot, dry and windy, but it can also have lush greenery.

The climate in northern Tanzania is characterized by a clear seasonality: the rainy season lasts from December to May, followed by the dry season from June to November. This natural rhythm also shapes the life of the Hadza, who is directly dependent on natural food sources, with water supply, vegetation and the animals' reproductive phases.

(See also geography of Tanzania .)

History and prehistory

prehistory

The Hadza have long been considered the last representatives of the indigenous people of East Africa. The latest genetic studies by an international research group, in which scientists from the German Max Planck Institute for the History of Man in Jena were also involved, support this view.

Around the middle of the first millennium BC Cattle- breeding peoples of the South Kushite languages came from the Ethiopian highlands to northern Tanzania and settled there. This began a long-term development that was to prove fatal for the Hadza. About a millennium later, peoples who are part of the extended family of the Bantu languages and who achieved food surpluses through agriculture and iron processing, immigrated from West Africa via Central Africa to both southern Africa and East Africa and gradually displaced the original wild-hunting peoples in all these regions into inaccessible and inaccessible inhospitable areas. Today they make up the majority of the population in the entire central, southern and eastern part of the continent. Thus, one has to assume a long-term (in this case even several millennia-long) coexistence of peoples with fundamentally different ways of life, as it is now also assumed for the prehistory of Europe.

(See also History of Africa and History of East Africa .)

history

Earlier modern times

In the late 18th century, militarily very powerful, semi-nomadic cattle breeders of Nilotic languages , especially the well-known Maasai , who come from the area of today's South Sudan , settled in today's Tanzania and - similar to the European migration of the people of late antiquity - set a " domino movement " there earlier resident peoples in motion. Since the 12th century, trading posts for Arab seafarers have been established and subsequently a chain of small city-states on the coast and on offshore islands of the Indian Ocean . From there, supra-regional caravan routes to the west into the Central African Congo metropolitan area were gradually established from the early 19th century . Metals and especially the so-called “white” and “black gold”, ivory and slaves found their way to the coast and on to other territories by ship. In return, firearms and gunpowder were brought inland (see East African slave trade ). Although the warlike superior Maasai kept northern Tanzania free from Arab traders, so that the trade routes ran further south, local African peoples also acted as suppliers and intermediaries for them. At that time the considerable population depletion and local extermination of the once very numerous elephants also began in the area of the Hadza, for whom they traditionally served as a source of food (see below for food acquisition ). It is also likely that women and children of the Hadza fell victim to the slave trade through African hands. The Hadza, on the other hand, fought a war with the Maasai for a long time, triggered by a misunderstanding caused by their fundamental cultural differences: Since the hunters had no idea of human "ownership" of animals, they made use of the grazing cattle that appeared in their habitat the shepherd nomads as prey animals. In the thinking of the Maasai, whose life and thinking were traditionally determined by cattle breeding, however, this meant “ robbery ”, which was punishable by the death of those regarded as “guilty”. Against this unexpected use of force, the Hadza tried to defend themselves with their weapons (see below for finding food ). The oldest German travel reports describe these processes as a real “hunt” by the Maasai on Hadza.

Colonial times

In the late 19th century, the region came into the focus of the colonial powers until the colony of German East Africa was forcibly established in 1885 . These new forms of rule and economy marked a new deep turning point in the history of the Hadza. They led u. a. increased "competing land claims between humans and wild animals":

"From the numerous reports by European explorers of the 19th century, one can infer that the abundance of game in East Africa before the colonial era must have been unimaginably great and extended over huge areas, the game population of which is now either low or has completely disappeared."

On the other hand, the slave trade was stopped and intensive efforts to protect wildlife began during German rule . The German colonial administration also used military means to stop the further violent spread of the Maasai to the south and thus probably saved the existence of the Hadza as an independent ethnic group with their ancestral way of life for more than another century. When the German Empire lost the First World War and the so-called Schutztruppe had to capitulate to the British colonial army at its end in November 1918, German rule in East Africa was in fact over after 33 years. The republican successor state was forced to formally cede all colonies in the following year . Tanganyika was now a mandate under British administration. Among other things, this had the consequence that the language medium of the research literature dealing with the Hadza also changed (compare below the chronological list of older literature on the topic). The new masters made brief attempts in 1927 and 1939 to forcibly settle groups of the Hadza as farmers, which in each case led to illnesses and several deaths in their community and increased the Hadza's distrust of strangers again. Since the late 1950s were - coinciding with the beginning of modern anthropological fieldwork among the Hadza - prominent, with the active help of German scientists as particularly Bernhard Grzimek the population biology intensified research on the wildlife and initiatives on how effective protection in Tanzania. These efforts continue unchanged to this day (see also: Nature Conservation History , Serengeti and Frankfurt Zoological Society ). Both the Hadza and the tourism industry , from which the Hadza are currently increasingly affected, benefit from the preservation of ecosystems and wild animal populations made possible by this to this day (see below: Existential threat and open future ).

Period of state independence

Tanganyika achieved political independence in December 1962 and was united with the island territories off the mainland to form today's Republic of Tanzania almost two years later. The new form of government turned out to be by no means advantageous for the Hadza, because in the years 1964-65 the new government enforced a forced settlement of most Hadza in villages through military action, which in the following period was due to the unusual density of settlements and poor hygienic conditions caused by infectious diseases and epidemics resulted in large population losses. Therefore, most of the surviving Hadza later left the settlements to return to their ancestral way of life (which is described in the following chapter on the traditional way of life ).

(See also History of Tanzania .)

(For the current consequences of the developments outlined here, which began in earlier millennia and centuries, see below Existential threat and open future . )

Research history

The research of the Hadza by representatives of the science of European tradition began with German-speaking explorers from the colonial era. Erich Obst already reported on the caring style of upbringing of this ethnic group. Modern research on Hadza began in 1958 - four years before Tanzania's political independence - when the British anthropologist James Woodburn, initially still a student at Cambridge University , first undertook long-term field research. Because he made a variety of personal contacts there and also learned the Hadza language, medical examinations were later possible with his participation, which required familiarity with the test subjects . In 1965, one year after completing his doctorate with his first dissertation on the Hadza, he designed an exhibition in the British Museum on this ethnic group. There were several other visits to Hadzaland by the mid-2010s.

The British zoologist Nicholas Blurton-Jones first carried out field research on wild animals from 1957 before turning to the behavioral ecology of wild -hunting peoples . After studies with the ! Kung in southern Africa (from 1970) and comparative studies in Malaysia and with the Navajo in Arizona (USA), his path led him to the Hadza, where he carried out repeated research from a first “pilot visit” from 1982 to 2000. He is considered a pioneer in human sociobiology .

N. Blurton-Jones became the teacher and inspirational scientific mentor for the Texas, US-born anthropologist Frank Marlowe (1954-2019), who studied with him for six years. F. Marlowe visited the Hadza for the first time in 1993, carried out extensive research on site in the following two years and, on his last visit in 2014, looked back on 21 years of field research experience. After his early retirement due to illness, the investigations are continued by his academic students and a small international network of Hadza researchers, who mainly come from North America, Great Britain and a few other European countries as well as Japan.

The traditional way of life

Overview

The traditional Hadza way of life is characterized as follows:

- They live as nomads and do not set up permanent settlements , but temporary camps.

- You lead a mobile life without real estate ownership and with only a few possessions, all of which can be carried by people themselves when changing camps - without pack animals, vehicles or transport equipment - with the help of carrying straps or in their hands.

- The acquisition of food takes place through wild harvesting. They know no agriculture or cattle breeding, traditionally no domesticated animals or plants , no horticulture and no beekeeping (see also: traditional economic system ).

- They do not keep stocks.

- This way of life makes a complete adjustment to the natural conditions and natural rhythms (course of the day and course of the year / see above the geographical framework ) and the changing natural food supply imperative.

- There is no formal training and no specialized professions.

- There is no in-house smelting and processing of metal.

- There is no production of textiles.

- Equipment is usually only manufactured for personal use. There is no money economy and, apart from a few equipment, no material wealth can be accumulated or inherited (compare: subsistence economy ). Differences in yield result exclusively from individual skills.

- A portion of the food purchased is consumed immediately - during the gathering or immediately after the successful hunt - another portion after returning to the common camp with one's own family and a further portion with all current group members - without contractual obligations, concrete promises, special advance or immediate consideration of the recipient - shared.

- However, it often happens that hunters defraud the other group members by secretly smuggling the prey into the village. If they are discovered in the process, the others abuse them violently. In constructed economic games you often offer little to your fellow players and most offers are rejected in principle, regardless of the amount. The Hadza generally share out of fear of gossip and exclusion.

- Life takes place in groups (traditionally also known as hordes in ethnology ), the composition of which among the Hadza is not fixed in the long term, but fluctuates. (Compare: Local Communities .)

- There is no political organization, no formal social hierarchy , no ranks or offices (in such cases one speaks of an acephalic society ).

- In principle, all group members have the same access to the resources - in such a case one speaks of an egalitarian society .

- There is no such thing as an organized religion . Religiousness manifests itself primarily in traditional mythology and there is a lack of hierarchy and offices, as well as - with one exception - also fixed rites and rituals . (Compare: Lack of religious organization in ethnic religions .)

- There is a clear and strict division of labor between the sexes, with some minor overlaps in activities.

- There is a free choice of adult life partner for both sexes. They often live in serial monogamy .

- It is customary for children to be brought up very attentively and at the same time freely, as they receive a lot of attention from both parents, but also have to fulfill their own duties early on.

Mobile life

The Hadza live nomadically in mobile camps. The group size is not fixed and not uniform. J. Woodburn stated in 1968 that he had found between one and a hundred and an average of 18 people per camp. During his extensive field research in the mid-1990s, F. Marlowe found that the ten camps he had recorded in detail housed between ten and 108 and an average of 29.1 people. They were left every one to two months, but visits or permanent group changes by individuals or families are even more frequent. Camps as a whole are abandoned when the local resources of drinking water and food are exhausted and the load of parasites in a camp becomes too great, or if a camp has died. The size and duration of the storage are essentially based on the local environmental conditions.

In the rainy season (see above climate ), simple round huts are built by families from long branches and long grass, the shape of which has been compared with upturned bird nests (see the picture on the side). In the dry season, all life takes place outdoors. People sleep in groups around a central fire on antelope skins, which usually come from impalas . When changing bearings, the entire belongings are carried along.

clothing

E. Obst reported at the beginning of the 20th century that the Hadza bought clothes in barter. During her stay in Hadzaland in 1930, Dorothea Bleek observed that all the men she met wore a piece of clothing, mostly made of calico , in addition to their leather belt , “to cover their nakedness”. However, these were "the most civilized members of their tribe" and she quotes J. F. Bagshaw, who met men who wore nothing but leather belts and bags. From this, and from the fact that all of the clothes mentioned came from European production, she concluded that men's clothing was a relatively new phenomenon among the Hadza.

“[…] The women, on the other hand, all wore two or three pieces of leather clothing that corresponded exactly to the clothing of the Bushman tribes who live in and south of the Kalahari , namely a wild animal skin apron, round for the married woman, tasselled for a girl, one Wildlife skin back apron that also hangs from the belt, and a fur or leather coat that hangs from the shoulders and is tied around the waist when a baby is carried in it. Children do not wear clothes, little boys only wear a belt and some jewelry, little girls wear a tiny fringed apron, to which a little fur coat is later added. Both sexes can be seen with whatever pearls they can get, mostly European or Indian made. I did not see any pearls made from ostrich egg shells . Copper ribbons that are worn around the neck or arms are in great demand. "

(See the picture .) Since D. Bleek's time and with increasing contact with other peoples, the Hadza have acquired more and more clothing in barter trade, both European-style, today often from clothing donations, and for women those of African tradition and origin: colored printed cotton towels , which are known throughout the Greater Region under the names Kanga and Kitenge .

The hanging with animal skins, on the other hand, is a modern invention of profit-oriented entrepreneurs in today's tourism industry (see existential threat below ) who want to serve the clichéd expectations of their financially strong customers from the countries of the northern hemisphere from supposedly “ authentic natives”. This follows the traditions of European literary and art history , as well as of the media of North American popular culture in the representation of "wild people" and not those of the Hadza himself.

(For information on the original clothing, see also below about the German documentary film series made in the 1930s in the Filmography chapter .)

Food acquisition

Traditionally, the Hadza also looked for food outside the described areas as far as the Serengeti. However, their sphere of influence is limited to a few biotopes, so that, according to Raymond Dasmann's definition, they are among the last “ ecosystem people ” on earth. Although hunting is banned in the Serengeti, the Tanzanian authorities recognize that this is a special case and are not enforcing the regulations. Likewise, the Hadza are the only ethnic group in Tanzania that does not have to pay taxes. According to the results of field research, adults spend an average of four to six hours a day looking for food.

There are traditionally four forms of food acquisition among the Hadza:

- Wild plants and their parts are collected: plucked or shaken from trees and bushes, picked up from the ground and dug up.

- Nests of wild bees are exploited.

- Wild vertebrates of various sizes and taxonomic groups are actively hunted .

- Carcasses of animals that have died due to natural causes or other hunters and have not yet decayed too far are tracked down and fully or partially exploited.

The composition of the menu is not only determined by individual ability and luck, but varies to a large extent with the seasonal offer that nature has in store. A modern study gives the following distribution of food for the total amount of food (measured in terms of food energy ) consumed in a Hadza camp within a year:

| Food source | proportion of | |

|---|---|---|

| Baobab fruit | 14% | |

| Tubers | 13% | |

| Nuts, stone fruits & legumes | 13% | |

| Berries & Figs | 9% | |

| honey | 11% | |

| Big game | 25% | |

| Birds & small game | 7% | |

| Food acquired through bartering (from neighboring peoples engaged in agriculture) | 8th % |

Thus the ratio of plants: honey: meat was 49:11:32.

Plant food supply tubers (z. B. various species Vigna fructescens, Vigna macrorhyncha, Coccinia sp., Eminia entennulifa, Ipomoea transvaalensis, Vatoraea pseudolablab ), the African baobab ( Adansonia digitata ) or baobab with its fruits , berries (of plant species such as Cordia crenata and sister species of the same genus, the star bushes Grewia bicolor and Grewia villosa or from the toothbrush tree ( Salvadora persica ) and other fruits (such as those of the marula tree or elephant tree , Sclerocarya sp. and others) and edible leaves. Mulberry figs ( Ficus sycomorus ) are a supreme Popular food with baboons like the Hadza, which they pick up from under the trees or shake off. The oily seeds of the baobab are not only obtained from picked fruits, but also regularly picked by the Hadza women from the dung of baboons, which do not open or digest them The honey , highly valued by the Hadza, comes from the East African highland bee and some wild bee species . The men not only take a lot of effort, but also dangers when they exploit bees' nests in a great tree height without rope protection (compare below health burdens and dangers ). The Hadza are part of a complex symbiotic network of four species. The large honey indicator or black throated honey indicator ( indicator indicator ), a bird up to 20 cm in size, feeds mainly on beeswax , which schizomycetes ( Micrococcus cerolyticus ) living symbiotic in its intestine allow it to digest by splitting into fatty acids , but is not itself able to break open bees' windows. It therefore indicates to the honey badger ( Mellivora capensis ), which is up to 70 cm tall, strongly built and protected from stings by thick fur and a layer of fat, as well as to human hunters, by means of a characteristic call and conspicuous movements, of bee nests, which it developed thanks to its very fine structure The olfactory sense of smell uses the fragrant beeswax to find out, and instinctively guides them over long distances to their location, in the expectation of subsequently profiting from the animal or human plunder of the nests in the form of wax and brood as food for themselves. (For the importance of honey, see below research among the Hadza as a 'model ethnicity' of anthropology . )

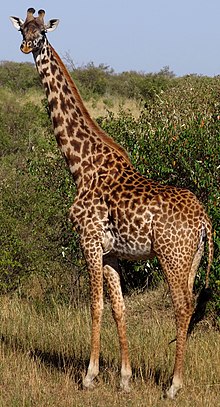

Hunting guide the Hadza almost exclusively with arrow and bow by (compare bow hunting ). They use wooden tipped arrows for hunting birds and game of small to medium size. Larger arrows, traditionally provided with stone tips, are made for hunting big game. As a result of expanded trade contacts over the years, iron hammered into stone is mainly used for this today. For the hunt for larger prey, the arrows are prepared with poisonous plants . The desert rose Adenium obesum , which is called panju, panjub or panjube in their language , is primarily used for this, as well as Strophanthus eminii, which they call shanjo . Both plants belong to the dog poison family ( Apocynaceae ). The size and mass of the prey today ranges from elephants to giraffes (in the Hadza habitat there are Maasai giraffes ), whose maximum weight is given as 1930 kg. DF Bleek learned in 1930 that "the meat of giraffes and ostriches is preferred because of its good taste" (meaning the Maasai ostrich , Strutio camelus massaicus ). The available arrow poisons are not strong enough for hunting African steppe elephants ( Loxodonta africana ). The hippos ( Hippopotamus amphibius ), which weigh up to 3,200 kg , used to be found in Lake Eyasi and were occasionally shot with wooden spears. Today they, like black rhinos ( Diceros bicornis ), are extinct in the Hadza habitat. Steppe baboons were described as a particularly sought-after meat meal and thus hunted prey , with the brain being consumed by the hunters together at the end of the meal. Prey animals such as porcupines (represented in Tanzania by Hystrix cristata ) have to be dug out of their burrow in hours of work, which is not avoided despite the considerable risk of injury. Since the populations of large game in the habitat of the Hadza have clearly declined compared to earlier times (see history above and existential threat below ), they are now dependent on consuming more of the birds that occur there in a large number of species. In "savannas, dry thorn-bush steppes, light forests, but also rocky terrain with individual bushes and trees" " helmet guinea fowl " "outside the breeding season in often very strong colonies." These birds, up to 63 cm in size and weighing up to 1,600 g (represented in Tanzania by the subspecies Numida meleagris reichowi ) were already a culinary attraction in Europe in antiquity and early modern times, which is why North and West African subspecies were domesticated at that time, and they often enrich the menu of the Hadza hunters (see the picture ). The fully grown an average of 0.130 kg heavy Mourning Collared Dove ( Streptopelia decipiens ) is above average frequently shot and the hunters have also frequently on numerous occurring small mammals avoid like the grown 1.8 kg to 5.4 heavy hyrax ( Procavia capensis ) that close with them related and frequently socialized smaller bush hyraxes ( Heterohyrax brucei ) from 1.3 to 2.4 kg and in rodents ( Rodentia ) (the sequences see in the short training film with links ), as well as with the Hadzajägern sympatrically living leopard ( Panthera pardus ) are dependent on rock hyrax as their main food in shortage situations such as high mountain regions.

During their stalking walks, the hunters habitually search the horizon for vultures circling in flight . In their area, besides other species, these are above all white-backed vultures ( Gyps africanus, also referred to by some authors as pygmy griffon vultures or Pseudogyps africanus ), "the" character vultures "of the wild steppes", which fly over large areas for signs of dead animals finally in large numbers, with up to hundreds of individuals, can be found on a carcass. (See pictures. ) By using this as a guide, the Hadza regularly manage to get hold of fallen game and cannibalize it for themselves. They also become aware of the rift of animal predators and can often steal their prey or part of it. (On this subject, however, see Physics and Health / Health Impacts and Hazards below . ) Even the carcasses of elephants, which the Hadza cannot actively hunt because of their size, have traditionally been a source of no small amounts of meat and extremely for them coveted animal fat. Today, their stocks have been severely decimated by centuries of ivory hunting (see story above ), which accordingly limits the food supply for the Hadza that has existed for thousands of years. (For the long-term ecological consequences of the extinction of the largest mammals in Hadzaland, rhinos and elephants, see threats to existence below . )

Depending on the natural growth and reproduction cycles, certain food sources can dominate the menu for a limited phase. During the ripening period of the berries of a Cordia species ( Cordia sinensis ), the Hadza consume large quantities of the fruits, which are their main food for about two months. During the breeding season of weaver birds - in this case were red-billed weaver ( Quelea quelea ) documents - the young birds are captured in large numbers from the nests. This bird species, up to 12 cm in size, forms "smaller or larger breeding colonies [...] The largest [...] can cover an area of several hundred hectares and contain an estimated ten million nests." [These] are usually found in trees, especially acacias , and occasionally in rushes . They are artistically woven, round in shape with a side entrance, and resemble those of the fire weavers and widas . […] The young stay in the nest for sixteen days […] ”. The breeding season in East Africa occurs twice a year, from December to February and from May to July. Up to 6000 nests can be counted in a tree. Since the breeding behavior is highly synchronized, all birds often leave the breeding area 40 days after the first start of breeding. The nests attract a whole range of predators, ranging from the long- feeler shrimp Acanthoplus discoidalis to reptiles and large birds to big cats - and also includes the Hadza, which push the young birds out of the nests in groups with poles made from long branches and on them Participate in food abundance. Root tubers, on the other hand, which are the least popular food category in view of their comparatively low energy content, are considered to be "fall back food", which is reliably available in equal quantities all year round and which can therefore be used at any time when there is a shortage of other, more popular foods. (To illustrate the topics dealt with in this chapter, see the short instructional film, the film preview, the illustrated reports and the picture gallery under literature , filmography and web links in addition to the pictures on the right .)

religion

According to the ongoing surveys of the evangelical-fundamentalist conversion network Joshua Project , other religions are viewed by the Hadza, like many other things, with rejection and distrust. According to this, 95 percent of the ethnic group profess their traditional religion. The remaining 5 percent are Christians.

Traditionally, the Hadza have neither clear ideas about God , nor spiritual specialists or prayers , no sacred buildings , sacred objects or images , neither religious morals nor ideas about life after death . Nevertheless, there is a belief in supernatural powers and cult acts , so that the assessment of some earlier authors - the Hadza have no religion - is now considered outdated.

As is often the case with egalitarian hunters, cosmogony and mythology are subject to constant change and know no dogmas : every Hadza has his own ideas and interpretations of religious traditions. In this respect, there are only a few corresponding beliefs.

The sun, moon, stars, and human ancestors are considered supernatural beings. The sun occupies a central position: In heaven she is the wife of the moon Seta under the name Ishoko , who constantly pursues her but never reaches her. The stars are the children of the divine couple. In relation to the creation story , however, the sun is thought of as masculine and called groves (as told by Hadza men ). According to Kohl-Larsen, however, Haine is Ishoko's husband ( identified elsewhere as the moon ), while according to his records, the sun is regarded as the mistress of the animals that created the animal world, the mythological giants and some strange people; protects the animals, but also directs the luck of the hunt. So it is considered a good wish for a hunter to pronounce Ishoko's name.

In the creation of man - or the Hadza - Haine (the sun) only plays a passive role in that the giant Hohole and his wife Tsikaio had to hide from him. After a cobra bite, the giant dies. His wife must first eat the dead man's leg in order to be strong enough to carry him. Then she moves to a baobab tree and gives birth to her son Konzere there. Tsikaio and Konzere, on the other hand, are considered the ancestors of the Hadza who eventually climbed from the baobab or - according to another version - came to earth via the neck of a giraffe.

The Hadza believe that neighboring peoples practice damaging magic and can curse them. They do not practice witchcraft themselves , although their central ritual theme, epeme, clearly has magical traits. The causes of physical suffering are often associated with breaking taboos about epemes . Epeme is by far the strongest expression of Hadza religious ideas. It is about manhood , hunting, the new moon and the relationship between the sexes. Epeme is both a kind of spiritual power that the hunter ingests through the consumption of the meat of certain animals, as well as the name of a ceremony that plays a crucial role in the social structure and religion of the Hadza.

Hadza women also keep secrets from men. Female circumcision, the clitoridectomy , is organized by women alone and is viewed as a purely woman's business. After the operation, the newly circumcised young women hunt the men, especially their potential husbands, with specially decorated staffs and attack them violently. Since the late 20th century there has been some evidence that Hadza women might decide on their own initiative to give up circumcision soon.

Epeme

The first successful hunt for big game (such as rhinoceros, hippopotamus, giraffe, buffalo, gnu or lion) turns a Hadza boy into an epeme man . Young people in their early twenties are actively encouraged to do so, but it can also happen that much younger people are ordained in this way . In contrast, men over 30 are classified as epemes even without hunting success. Only Epeme men have the privilege to eat certain parts of the large game ( Epeme meat : kidney, lungs, heart, throat, tongue and genitals). However, they are only allowed to do this together with at least one other Epeme man. Likewise, children, women and uninitiated men are forbidden to watch Epeme men eat Epeme meat. If these taboos are broken, the Hadza assume that a bad misfortune will hit the "sinner".

The epeme dance ritual of the same name is carried out on all moonless nights in complete darkness, so that the participants can hardly see anything. The Epeme men are considered holy beings and dance one after the other in hard and stiff performance for one to two minutes, while they call and sing to the women who sing as accompaniment in a sacred whistling language that is used solely for this context. At first the women sit there, but as the dance progresses they get up and dance with increasing grace around the man, who performs this performance several times, each time extending it a little. After a man leaves, he gives his dance equipment (black cape, feather headdress, ankle bells, rattle) to another man and the dance repeats itself accordingly.

The epeme ritual is considered indispensable for the well-being of the Hadza. It can be interpreted as a recurring ceremonial reconciliation between men and women.

mythology

There are some mythological characters that are believed to be. This includes, for example, Indaya, who plays the role of a cultural hero : it is said of him that he rose from death and went to the Isanzu , who worked in the fields , in order to bring customs and goods to the Hadza from there. This also explains the friendly position towards the Isanzu ethnic group. Malicious giants with human weaknesses also appear in Hadza mythology. Sometimes the help of strangers or a god - including an Isanzu man - plays a role.

The language

description

The Hadza language, called Hadzane by them , is isolated , but has typological similarities to the Khoisan languages . These similarities were mainly seen in the use of clicks or clicks . The word order is flexible: the basic order is verb - subject - object (VSO), but verb-object-subject (VOS) and the juxtaposition to subject-verb-object (SVO) are both very common. What are nouns (nouns) genus or grammatical gender (masculine and feminine = male and female) and number or number (singular and plural = singular and plural). They are indicated by suffixes (appended end syllables) as follows:

| Sg. | Pl. | |

|---|---|---|

| m. | -bii | |

| f. | -ko | -bee |

Adjectives and verbs are also inflected with intermediate and final syllables . There were no numerals except itchame (one) and pie (two) before they were borrowed from neighboring languages.

A special feature: special names for dead animals

Hadza has received some attention for a dozen "celebratory" (J. Woodburn) or "triumph" ("triumphal", R. Blench) names for dead animals. They are grammatically not nouns, but verb forms in the imperative . They are used to announce a successful hunt (or capture of a carcass) and thus to draw attention to the specific prey. They are these (in the imperative singular):

| animal | Generic name | Triumphant name |

|---|---|---|

| zebra | dóngoko | hantáii |

| giraffe | zzókwanako | Hawaii |

| Cape buffalo | naggomako | tíslii |

| leopard | nqe, tcanjai | henqêe |

| lion | séseme | hubuee |

| Eland | khomatiko | hubuii |

| impala | p (h) óphoko | dlunkúii |

|

Gnu hartebeest |

bisoko qqeleko |

zzonoii |

| Other large antelope | hephêe | |

| Little antelope | hingcíee | |

| Black rhinoceros | tlhákate | hukhúee |

| Elephant hippo |

beggáuko wezzáiko |

kapuláii |

|

Warthog boar |

dláha kwa'i |

hatcháee |

| baboon | neeko | nqokhóii |

| African ostrich | khenangu | hushúee |

The words are somewhat generic: henqêe can be used for any spotted cat , hushuee (hushuwee) for any running ratite . "Lion" and "Elen" use the same root. Blench (2008) estimates that this may have something to do with the fact that the eland is considered magical in the region.

Physique and health

Physique and general health

Some very detailed scientific studies are also available today on the physique and health of the Hadza. In a series of measurements published in 2000, the gender-specific average body measurements of adults were determined as follows:

| In men | In women | |

|---|---|---|

| body length | 1.625 m | 1.513 m |

| Body fat percentage | 11% | 20.4% |

| Body mass index ( body mass index ) | 20.2 | 20.6 |

Serious supply bottlenecks do not occur even in years of drought and medical examinations have shown that the Hadza have a very balanced diet, which gives them far better health than their field-farming neighbors.

Health burdens and hazards

The Hadza are exposed to a long series of sometimes considerable health problems. Some of them share it with the other peoples of the country and other tropical regions . Thus, infectious diseases , respiratory and diarrheal diseases often, and in tropical endemic and feared tropica malaria . These three are the main causes of the very high child mortality rate .

Other stress factors result from their specific habitat and their way of life. Even the vegetation harbors risk of injury from numerous thorn plants :

“[...] To march through Hadzaland in the dark is a challenge; Thorn bushes and pointed acacia trees dominate the area and even during the day there is no way to avoid getting stung, scratched and pierced. A long hike in the Hadza Wilderness can feel like getting a gradual full body tattoo. The Hadza spend a significant amount of their recovery time digging up thorns for one another with the tips of their knives. "

(For the problem of thorn plants, see the threat to existence and open future below . ) When exploiting bees' nests in trees - especially baobab (see above for food acquisition , with the picture ) - from z. Sometimes at high altitudes, Hadza men regularly suffer falls and often broken bones, sometimes with fatal consequences. Aging men with diminishing physical strength, who do not want to give up the pleasure and prestige-promising honey hunt, are particularly at risk. In their habitat the Hadza occasionally come into contact with various venomous snakes . What is particularly feared here is by far the largest on the continent, the black mamba ( Dendroaspis polylepsis ) usually up to 2.50 m long, in individual cases up to 4.30 m long , which, in contrast to the other species of the genus, mostly lives on the ground. "Mambas produce highly effective mixtures of toxins in their poison glands " with a predominantly neurotoxic effect and their bite leads to death in the event of larger amounts of poison injected without intensive medical treatment through progressive paralysis of the muscles and thus respiratory arrest, and can even "become life-threatening within minutes". They are described by biologists as terrifying and with "extremely strong poison", but are only aggressive during the breeding season. Even scorpions put their hunting poison a defense. They sting if you "accidentally press or squeeze the animal, [...] or if you reach under wood or stones where scorpions are sitting", as well as children who play with them. The species that are dangerous to humans all belong to the family Buthidae , of which Parabuthus leiosoma is common in East Africa.

Large vertebrates are also dangerous. In the past, Hadza regularly suffered fall injuries while fleeing in the confusing and impassable terrain from attacking black rhinos and elephants, whose populations are now drastically reduced, but this brings new dangers with it (see threat to existence below ). Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) are usually not aggressive, but with a body mass of up to 680 kg, they attack hunters very vigorously after they have been injured and can inflict very dangerous wounds on hunters. Therefore, they are counted among the known causes of death for Hadza men.

The Hadza hunters often try to rob large and thus defensive animal hunters of their prey: the Maasai lion ( Panthera leo massaicus ), the leopard ( Panthera pardus / see above for food acquisition ) and the spotted hyena ( Crocuta crocuta ), who are usually between 40 and 65 kg, but in some specimens it weighs more than 80 kg and the "[e]" with strong teeth, that is, large teeth and strong masticatory muscles, enables the leg bones of large ungulates to be broken without difficulty . Hyenas actually have a scissor bite in the area of the molar teeth ”(see the corresponding illustration ). Hadza men occasionally pay for such attempts with their lives, despite their armament.

Remedies

The Hadza also have various kinds of remedies themselves. Even after snakebites, various - not specifically identified - plants are administered that they themselves describe as effective. While "there is little hope with the most venomous snakes, as they can kill a person in minutes or seconds, these plants apparently help with less venomous, yet still fatal, snakes as many people say they were saved that way." These wild plants are also in demand as barter goods from neighboring peoples of the Hadza. Such traditionally used snake venom and scorpion venom antidotes have been described many times in Africa. For at least two such plants, which are also known as medicinal plants in Tanzania and also as arrow poisons in other countries on the continent, an effectiveness against snake poisons was proven in the late 20th century using scientific and experimental methods: for the wild violet tree ( Securidaca longepedunculata ) from the family of polygalaceae ( Poligalaceae ), "a legendary medicinal and poisonous plant Africa", and for the herb Diodia scandens of the family Rubiaceae ( Rubiaceae ).

Existential threat and open future

introduction

The Hadza, who have been able to keep their way of life largely unchanged for thousands of years, are now acutely threatened in their way of existence, collective identity and culture. While they were probably saved from extinction at the end of the 19th century by the intervention of the German colonial administration, today a whole series of developments that have lasted for a very long time accumulate, which mutually reinforce one another and which are joined by modern social and economic factors and developments. On the other hand, there is resistance on the ground and among people in solidarity in Europe and North America, which seeks to create awareness for this situation and to encourage counter-movements.

Threatening factors and developments

overview

Long lasting developments

- The farming and cattle breeding neighboring peoples traditionally treat the Hadza with disdain (compare the name above ) and without considering their way of life and needs. This continues in the majority population of the modern state, the rulers of which all come from settled peoples. (Compare the violent settlement programs above in history and prehistory .)

- Since the colonial times, the Europeans have transferred their ideology of progress in the sense of a modern state and a profit-maximizing, formal science-based and nature-exploiting, technical and economic innovation-seeking way of life to the ruled peoples and largely adopted them. Many citizens and politicians in the modern state of Tanzania regard the existence of a people with the largely unchanged original way of life of nomadic hunters as a manifestation of backwardness and a "shame for the nation."

- Traditionally, the Hadza have no social or political organization beyond their family and their own group with a fluctuating composition. This has proven itself in the traditional way of life, but makes it largely defenseless against external threats: you could only offer individual resistance. The hunters of East Africa, whose last cultural descendants are the Hadza, withdrew for thousands of years, which is no longer possible today. Nor do they traditionally have the formal or school education ( see below ) that would enable them to actively represent their interests in the modern world.

- For millennia, the greatest threat has come from - viewed over long periods of time - continuous population growth of the sedentary and food surplus producing population of the Greater Region, which has accelerated since the 19th century. The accompanying increase in the number of livestock among the sedentary and partially nomadic peoples increases the growing need for land.

- This led and still leads to increasing settlement of previously free land and its permanent agricultural use.

- At the same time, resources on land, wild plants and water are increasingly being used by mobile herds of livestock and are therefore no longer available to wild animals and wild-hunter nomads.

- While the Hadza hunt with traditional methods and for their own livelihood had no long-term detrimental effect, since the 19th century the hunt of other peoples for the purposes of the extraction of luxury goods and prestige objects, for "sport", for entertainment and for meat - and souvenir market catastrophic consequences for wildlife, landscape and traditional hunting people.

- The diverse activities of white and African settlers, shepherds and hunters, which have been intense since the 19th century, also have serious long-term effects, e.g. In some cases indirect ecological consequences that the Hadza, who are completely dependent on local natural resources, feel directly.

- Global climate change is meanwhile also having a clearly negative impact in northern Tanzania.

- Due to the increasing spatial proximity with foreign peoples, the trade contact also increased, whereby Hadza came increasingly into contact with stimulants and intoxicants .

Modern developments

- The role of modern school education is viewed ambiguously and viewed controversially by various Hadza and external observers. Some consider this to be desirable or even essential to survive in today's world. On the other hand, there are concerns , especially for boarding school operations , that it leads to cultural alienation from their own people and their own way of life and tradition and opens up new generations to the influence, shaping and indoctrination of strangers and their values and goals.

- Economic development has been accelerated in Tanzania since the end of the 20th century. In the course of this, considerable financial resources are flowing here from abroad.

- In the 21st century, in the course of such modernization, road construction in northern Tanzania is being intensively promoted, which among other things completely changes the accessibility of the Hadza in its traditional retreat.

- Some observers, such as long-time field researchers, regard the profit-oriented exhibition tourism to the Hadza, which began to increase in the 1990s, as the greatest long-term threat following population pressure.

details

Settlement pressure

The remaining hunting and gathering grounds of the Hadza are severely threatened by interference. The Mang'ola region became the main onion growing area in East Africa and this has led to a sharp increase in population in recent years. The western habitat of the Hadza is in a private hunting area; the Hadza are officially restricted to a reserve where they are not allowed to hunt. The Yaeda Valley, long uninhabited because of the tsetse fly , is now claimed by Datooga herders. The Datooga clear the Hadza lands on both sides of the now fully populated valley as grazing areas for their goats and cattle. They scare away the game and drive it out of the area, and the clearing destroys the berries, plant roots and honeys that the Hadza rely on. In addition, the waterholes they dig for their cattle cause the shallow waterholes from which the Hadza draw their drinking water to dry out. Most Hadza are therefore no longer able to supply themselves from the wilderness alone without supplementary food such as the cereal porridge (traditionally made from millet , now mainly made from cornmeal ), which is common in East Africa as a basic diet , which is known there as ugali .

Ecological changes and hunting by strangers

Serious consequences are also expected from the hunting of the largest species of megafauna with firearms, which began in the early modern period and increasingly in the 19th century, and the consequent dramatic destruction of the population (see history and food acquisition above ): There are clear indications that the food intake and the pounding movement of black rhino and desert elephant formerly held many open parts of the landscape.

The black or pointed- lipped rhinos, the maximum weight of which is given as 1300 kg or 1500 kg,

“They particularly like to eat twigs that they grasp with their pointed upper lip like a finger or hand. Even if you see them grazing on a lawn, in reality they often only pull very small, new, tiny bushes out of it. [The English ecologist and conservationist Sir Frank] Fraser-Darling found that a rhinoceros drew 250 small flute acacias [( Vachellia drepanolobium )] out of the earth and ate them . How much rhinos can change the image of the African landscape in this way! And what consequences their extermination can have in some areas! "

You can also use your horns and your body weight to break down larger trees and then “graze the tips of the young branches. Pointed-lipped rhinos also eat the very prickly branches of the thorn bushes [...] "

"Today we can hardly believe how especially white hunters raged among the pointed-lipped rhinos [...]"

The ecological importance of the steppe elephants , which can weigh up to 6 t, lies in the large amount of food that they obtain from bushes and trees , which they can also cut down, and in the fact that they spread plant seeds and pave the way for other animals and people can. After regional extermination in antiquity and the Middle Ages, the Arab ivory trade, which began in the 17th century, conjured up a further rapid decline in elephant populations in both West and East Africa. The process was accelerated by traffic development and modern technology during the colonial era and peaked between 1830 and 1910 and then again between 1970 and 1989. Settlement pressure, deforestation and road construction, which interrupt wildlife trails, represent a threat today alongside hunting.

Due to their traditional landscape-shaping function, the lack of these species will in the long term presumably lead to unhindered and therefore increasingly dense populations of thorn trees and bushes increasing the inhospitable and impassable nature of the landscape and reducing the number of game and wild plants to which the Hadza are dependent on survival. (See also megaherbivore hypothesis .)

In 2007, the local government, which controls the Hadza lands adjoining the Yaeda Valley, leased the entire 6,500 square kilometers of the area to the Al Nahyan Royal Family of the United Arab Emirates for their use as a "personal safari recreation area" (" personal safari playground ”). Both the Hadza and neighboring Datooga were forcibly expelled and some Hadza resisting were arrested. However, after protests from the Hadza and negative reports in the international press, the contract was canceled.

Furthermore, global and regional climate changes are already making themselves felt in northern Tanzania. In the case of one of the country's landmarks, Mount Kilimanjaro on its northern border , a former volcano and at the same time the highest mountain on the continent, declining glaciers have been documented, making the decreasing amounts of precipitation in the region visible from afar. This will not be less evident in the future in the last retreat that the Hadza are forced to put up with and which is already characterized by seasonal water shortages and increasing competition for resources.

Modern show tourism

Documentation about the Hadza in news media such as the Public Broadcasting Service in the United States and the BBC in Great Britain made the Mang'ola region's Hadza a tourist attraction, with visitor numbers increasing significantly in the second half of the 1990s. The materially wealthy travelers transported in large vehicles get to see demonstrations of archery and dances supposedly "authentic savages" (see also above under clothing . ) Although this may seem to help the Hadza on a superficial view, most of the money raised is withheld by government agencies and business-minded, profit-oriented tourism companies and their employees who belong to foreign or Tanzanian peoples, instead of being used for the benefit of the Hadza. Money that Hadza - traditionally not used to any monetary economy, not even to long-term, far-sighted thinking, to no stockpiling or other long-term planning - directly receives, is immediately spent by neighboring peoples for agriculturally produced food and increasingly also for luxury goods. Tourism therefore leads in the long term to a different lifestyle, to a different, unhealthy diet and, above all, to a long-term loss of practical and cultural knowledge. In addition, it is a major contributor to alcoholism , which neighboring alcoholic beverage-producing peoples specifically promote for profit through aggressive sales behavior, and deaths from alcohol poisoning and alcohol- induced violence have been local serious problems for some time. In addition, alcohol consumption promoted the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis among the physically weakened Hadza.

Because of such ever increasing habituation effects, experienced observers see commercial show tourism as the greatest danger for the continued existence of the Hadza as an independent people with their ancestral, today unique way of life and culture based on this after population growth and settlement pressure:

"[...] It seems that the Hadza may continue to search for food for a while during the rainy season when mud prevents tourists from coming. But it may not be long before tourism is the end of year-round foraging. It will perhaps be the case that the Hadza culture, which has remained little changed in spite of the long contact with more powerful neighbors, will now, with the arrival of tourists, finally succumb to outside influences, mainly because tourists are a source of money. The irony is, of course, that the tourists come to see the hunters and once they have completely eradicated the huntings they won't come and leave the Hadza with no source of income. "

Countermovements

The experienced field researcher Nicholas Blurton Jones, on the other hand, describes the wishes of the traditionally living members of the people:

“The Hadza say they have always hunted and gathered, and often say that they wish to do so for ever. When the context arises, they explain to other Tanzanians that the bush is clean, peaceful, and safe, and that unlike farmers, they like to eat meat and the bush provides enough, even though their hunting is conducted only by traditional bow and arrow. ”

“The Hadza say they have always hunted and gathered, and often say that they wish to do so forever. On occasion, they explain to other Tanzanians that the bush is clean, peaceful and safe and that, unlike arable farmers, they like to eat meat and that the bush provides enough, although their hunt is only carried out with a bow and arrow. "

According to the ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss , they belong to the “cold cultures” whose focus is on the preservation of their traditional cultural characteristics.

In 1989, Moringe Parkipunty as an activist for the Maasai and Richard Baalow as an activist for the Hadza gave speeches for the first time as envoys from African communities at the sixth session of the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples in Geneva to address the shameless violations of community and individual rights Raise the awareness of minority groups of hunters and many groups of pastoralists in East Africa. Subsequently , non-governmental organizations were founded in Arusha , the regional metropolis of northern Tanzania, to support them and have been fighting for their rights ever since. Organizations overseas also joined this initiative such as Survival International , which is represented in several countries, and Rettet die Naturwölker in Germany (see their information portals under web links ).

In October 2011, the Tanzanian government formally recognized the land rights of a Hadza community for the first time and handed over title deeds.

In the course of international efforts to curb global climate change, so-called indigenous peoples or communities living close to nature are now seen as partners who need to be supported in their traditional way of life, among other things, as preservers of natural vegetation. In this sense, the social enterprise Carbon Tanzania is committed to the Hadza today .

In this context, the Equator Prize of the United Nations Development Program for nature-based contributions by indigenous peoples to climate protection was awarded to a representative of the Hadza in New York in 2019 .

Research among the Hadza as a model ethnicity in anthropology

Introduction: knowledge interest, context and reception

The Hadza are particularly interesting for scientists because they serve as a kind of model ethnicity for general issues in anthropology , evolutionary ecology and hominization and help to understand the "original" or "natural" way of life, the environment and the conditions in which the (early) Understanding and reconstructing people. The inferring of recent observations and always fragmentary data harbors scientific methodological pitfalls: "The reconstruction of behavior is an important part of scenarios for incarnation: Nutritional strategies such as gathering, hunting or scavenging as well as aspects of community life such as food sharing, cooperation and communication are based on individual behaviors , But the counter-arguments to the hominization models show that many weaknesses and errors in the models are based on misinterpretations in the area of behavior. ”Results from the Hadza field research are initially published as English-language articles in specialist journals, but are now also included in specialist encyclopedias such as evolutionary biology , as well as in English and German language textbooks in various disciplines such as human biology and evolutionary medicine and, since the mid-2010s, on physiology topics and health promotion in popular science magazines such as Scientific American in the US, as well as delayed in their “daughter” spectrum of science . and also in Geo in Germany.

Studies on individual topics and questions

Food procurement and nutrition

(Compare the overview above in the chapter The traditional way of life . )

According to results published in 2009, the sexes differ significantly in their specific food preferences. Of the five main categories of food among the Hadza, all named honey as their favorite food and tubers as the least valued, with baobab in the middle. But while women valued berries as their second favorite and meat only ranked fourth, it was the other way around for men with meat in second and berries in fourth.

physiology

In a study published in 2012 in Hadzaland in “several dozen” women and men, US researchers succeeded “for the first time [...] in directly measuring the daily energy expenditure of hunters and gatherers.” Because “Doctors and evolutionary biologists have long assumed , our hunter-gatherer ancestors would have consumed more energy than we city dwellers do today. Given the hard physical work that hunters keep doing, that seems perfectly logical. Many health care professionals have therefore suggested that the alleged decrease in daily energy expenditure is the reason that obesity , obesity and metabolic syndrome are becoming more common in the developed world. How could it be otherwise, in view of the high-calorie food that we do not convert into physical activity and which is therefore reflected in body fat? ”But to the“ amazement ”of the researchers, the study using the most modern scientific methods revealed:“ Hadza men eat and burn therefore an average of 11,000 kilojoules (2,600 kilocalories ) daily, Hadza women around 8,000 kilojoules (1,900 kilocalories) - that is hardly any difference to adults in the USA or in Europe. "" [...] It seemed so obvious that physically active people burn more calories that we had accepted this paradigm without critical review and without evidence . "Now the insight emerges that the energy expenditure is" largely fixed ", both in the human species, as well as in other primates and other animal species, like later studies, each with a comparison of those living in the wild with those living in human care or captivity n individuals revealed. The energy expended for physical activity is obviously saved by the organism in other places. For health care it follows: "Most medical professionals should be familiar with the old dictum that one cannot run away from poor nutrition." Physical exercise is necessary "to stay healthy and vital," but for weight control one must concentrate on the supply of nutritional energy .

A study of the intestinal flora of 188 people published in 2017 showed that they differ significantly in their species composition in the rainy or dry season - i.e. in seasons when different food sources are used.

(For further results from the field research with the Hadza see above the chapters Prehistory , The Traditional Way of Life , and Physique and Health .)

Filmography

The German documentary film series from 1941

- Data: Ludwig Kohl-Larsen: The Tindiga. A hunter-gatherer people in the drainless area of German East Africa. Germany 1941. 42 minutes. 16 mm, video.

- Background and origin: A modern summary of recordings of the "German Africa Expeditions 1934–1936 and 1937–1939 under the direction of Dr. Ludwig Kohl-Larsen ". In 1941 they were processed into five university films by the Reich Institute for Film and Image in Science and Education ( RfdU or later RWU ). (For the author, see literature below , for the title of the film, see the name designation above . )

- Source: The original recordings and other finds from the expeditions are kept in the Kohl-Larsen archive of the Museum of the University of Tübingen , on which he last researched.

- Image impression: An original image was published in the program for a re-performance in 2019.

- The themes and titles of the original single films are:

- The landscape and its inhabitants

- The Tindiga as a collector

- The Tindiga as a hunter

- Fire preparation and manual skills

- Games and dance .

The 2014 American documentary

- Dates: The Hadza: Last of the First. USA 2014. 71 minutes. Director: Bill Benenson. With appearances by various scientists such as the anthropologist Alyssa Crittenden, who also worked as an advisory expert (see the interview under web links ), the primatologist Jane Goodall and others.

- Description and production: “A documentary film about the importance of Hadza hunters and gatherers for research into human evolution and cultural survival.” The film was shot for three weeks in August 2011 in the Hadza homeland in northern Tanzania and for one week in California (UNITED STATES). It premiered in March 2014 at the Smithsonian Environmental Film Festival in Washington, DC

- View:

- Presentation of the film with ten large-format photographs on the producer's portal.

- Film preview ( trailer ) (1:44 minutes long).

- Reception:

-

Mixed-judgment review by Martin Tsai on the Los Angeles Times portal , published October 23, 2014.

- The reviewer perceives the film as a (too) “academic, but valuable view” of the Hadza. He compares the style to documentary and magazine publications, it seems far removed from the art of film , some passages are amateurish and unsuitably dry and scientific. He avoids reviving the “myth-making ethnography”, which he sees as the epitome of the famous film Nanook of the North by Robert Flaherty from 1922. Hadza's egalitarian society appears much more civilized than his own, and the film proves to be most valuable in those places where Hadza talked about their confrontations with modernity, such as schoolchildren who undertook a long and exhausting escape from a boarding school, to escape the punishments practiced there , which they had never known in their homeland.

-

Positive review by Anita Gates on the New York Times portal , published October 30, 2014 (English).

- The reviewer rates the film as “a delightful documentary [...] about a people in Tanzania who live in this way [like our ancestors before the development of agriculture] and remind us of what a sustainable way of life really looks like and how ridiculous we are are removed from it. "

-

Positive review by Camilla Power on the Anthropology News portal of the American Anthropological Association , published on May 21, 2018. The reviewer is an anthropologist at the University of East London and has conducted field research with the Hadza herself.

- C. Power calls it "a fascinating documentary about the Hadza people well worth seeing." She also remembered the "various dismayed reactions of the Hadza children" who reported their experiences in Swahili schools and found them to be "very touching." With questions about the future fate of this people, she asks as a conclusion whether, instead of developing the Hadza, we are not the ones who "have to learn lessons from them."

-

Mixed-judgment review by Martin Tsai on the Los Angeles Times portal , published October 23, 2014.

(Compare also didactic media below under web links .)

literature

Scientific literature

(It lists reviews as well as publications that are important in the history of research and that have been cited several times. For publications and literature on special topics and peripheral areas that are only cited occasionally, see the individual references below . )

Publications based on research at the Hadza

First travel reports and research results that were published during the colonial era

(in chronological order according to the year of publication)

- (1894) Oskar Baumann : Through Maasailand to the source of the Nile: Travel and research of the Maasai expedition of the German anti-slavery committee in the years 1891-1893. Reimer-Verlag, Berlin. (Also as an English translation from 1964 and as a German reprint edition from 1968.) (The Austrian geographer O. Baumann is considered to be the European scientific discoverer of Lake Eyasi and the Ngorongoro Crater. His book contains the first known mention of the Hadza However, since they hid from him, his account of them is based solely on reports from other peoples in the region.)

- (1910) M. Krause: The arrow poison of the Watindiga. In: Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift . Pp. 1699-1702.

- (1912) Erich Obst : From Mkamala to the land of the Wakindiga. In: Communications from the Geographical Society in Hamburg . Volume 26, pp. 1-45.

- (1916) Otto Dempwolff : The Sandawe. Linguistic and ethnographic material from German East Africa (= treatises of the Hamburg Colonial Institute . Volume 34, Series B, Issue 19). Publisher L. Friederichsen, Hamburg. (O. Dempwolff served as a military doctor in the German colony and carried out linguistic and ethnographic studies, especially with the Sandawe in East Africa . In this context he met the Hadza himself, whom he mentions in passing.)

- (1924/25) FJ Bagshaw: The peoples of the Happy Valley (East Africa). Part 2. In: Journal of the African Society. Volume 24, pp. 25-33.

- (1931) Dorothea F. Bleek : The Hadzapi or Watindega of Tanganyika Territory. In: Africa. Journal of the International African Institute . Volume 4, pp. 273-286.

- (1949) B. Cooper: The Kindiga. In: Tanganyika Notes and Records. Pp. 8-15.

- (1956) HA Fosbrooke: A stone age tribe in Tanganyika. In: The South African Archeological Bulletin. Volume 11 (41), pp. 3-8.

- (1956) Ludwig Kohl-Larsen : The elephant game. Myths, giants and tribal legends. Tindiga folk tales. Erich Röth-Verlag, Eisenach and Kassel. (A collection of myths of the Hadza: From giants of the origin of the world and its natural order, and the tribe say and anecdotal tales .)

- (1958) Ludwig Kohl-Larsen: Hunters in East Africa. The Tindiga, a people of hunters and gatherers. With 119 photos by the author and 77 drawings by Hans J. Zeidler. Reimer-Verlag, Berlin (165 pages). (The prehistorian and ethnologist L. Kohl-Larsen conducted research among the Hadza who lived east and south of Lake Eyasi in 1934/38. Since his book was not translated into English, it is practically neglected in modern English-language research literature . / For the pictures taken at that time, see also above in the filmography .)

Modern research published since the independence of Tanganyika

(In alphabetic order)

- FJ Benett, NA Barnicot, JC Woodburn, MS Pereira and BE Henderson: "Studies on viral, bacterial, Rickettsial and Treponemal Diseases in the Hadza of Tanzania and a note on injuries." In: Human Biology. Volume 45, No. 2, May 1973, pp. 243-272.

- Nicholas Blurton Jones: Demography and Evolutionary Ecology of Hadza Hunter-Gatherers (= Cambridge studies in biological and evolutionary anthropology. ) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2016, ISBN 978-1-107-06982-4 . (This extensive monograph of almost 500 pages is more “specialized” than Frank Marlowe's description of Hadza (see below) and, based on the author's years of field research, is dedicated to the main topic “ Demography and evolutionary ecology of the Hadza hunters and gatherers”.)

- Alyssa N. Crittenden: 16. Ethnobotany in evolutionary perspective: wild plants in diet composition and daily use among Hadza hunter-gatherers. In: Haren Hardy, Lucy Kubiak Martens (eds.): Wild harvest: Plants in the Hominin and Pre-Agrarian Human worlds (= Studying Scientific Archeology. 2). Oxbow Books, Oxford et al. a. 2016, ISBN 978-1-78570-123-8 , pp. 319-340.

- DB Jeliffe, J. Woodburn, FJ Bennett, EFP Jeliffe: "The children of the Hadza hunters." In: Journal of pediatrics. Volume 60, No. 6, pp. 907-13.

- Frank Marlowe: Why the Hadza are still hunter-gatherers. In: Sue Kent (Ed.): Ethnicity, Hunter-Gatheres, and the “Other”: Association or Assimilation in Africa. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 2002, pp. 247-257. (An introductory essay with a central question: "Why the Hadza are still hunters and gatherers.")

- Electronic text version: see links below .

- Frank Marlowe: The Hadza. In: Carol R. Ember (Ed.): Encyclopedia of medical anthropology: health and illness in the world's cultures. Volume 2: Cultures. Springer Verlag, New York 2004, ISBN 0-306-47754-8 , pp. 689-696. (An overview chapter from the point of view of Anglo-American "Medical anthropology", which as a subject roughly corresponds to German-speaking medical ethnology.)

- Frank W. Marlowe: The Hadza. Hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. ( Origins of human behavior and culture; Volume 3.) University of California Press, Berkeley et al. a. 2010, ISBN 978-0-520-25342-1 . (This monograph summarizes on 325 pages the results of years of field research by the author, as well as the specialist literature available at the time, and undertakes an overall presentation of all aspects of the Hadza way of life and culture; a standard work that has since been cited many times in research articles.)

- Martin Porr: Hadzapi, Hadza, Hatza, Hadzabe, Wahadzabe, Wakindiga, WaTindiga, Tindiga, Kindiga, Hadzapi? A hunter culture in East Africa. Mo-Vince-Verlag, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-9804834-5-2 . (A small monograph from an archaeologist's point of view .)

- James Woodburn: The social organization of the Hadza of Northern Tanganyika. Dissertation , University of Cambridge 1964. (The first university dissertation on the Hadza. By a pioneer of modern field research who began it in the late 1950s - before the country became independent.)

- James Woodburn: An introduction to Hadza ecology. In: Richard Borshay Lee , Irven DeVore (eds.): Man the hunter: the first intensive survey of a single, crucial stage of human development - Man's once universal hunting way of life. Aldine, Chicago 1968, pp. 49-55. (An early overview, contained in an extensive collection of essays that was reprinted many times up into the 1980s, from a pioneering international conference of scientists in Chicago in April 1966 on "The human being as a hunter", i.e. comparative global research on the ethnology and ecology of the then still existing Hunter cultures, emerged.)

- James Woodburn: Hunters and Gatherers. The material culture of the nomadic Hadza. The trustees of the British Museum, London 1970, ISBN 0-7141-1510-X . (A smaller publication from the British Museum , mainly containing illustrations.)

- James Woodburn: Egalitarian Societies. In: Man. Neue Serie, Volume 17, September 1982, pp. 431-451. (A fundamental essay, published in the journal published by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland , examining basic issues of social organization in relation to food supply and way of life using African hunter cultures. It is related to the scientific, political and philosophical discussion surrounding the Egalitarian society and to what extent it is represented by “original” hordes of hunters .)

- Bwire Kaare, James Woodburn: Hadza. In: Richard B. Lee, Richard Daily (Eds.): The Cambridge encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1999, ISBN 0-521-57109-X , pp. 200-204. (A review of the Hadza, written after four decades of field research. Among colleagues, J. Woodburn is also referred to as the one who "knows most about the Hadza.")