Johannes Bugenhagen

Johannes Bugenhagen (born June 24, 1485 in Wollin , Duchy of Pomerania ; † April 20, 1558 in Wittenberg , Electorate of Saxony ), also called Doctor Pomeranus , was an important German reformer and companion of Martin Luther .

After studying in Greifswald and working in Treptow at Rega , Bugenhagen joined Luther's ideas in 1521, became pastor at the Wittenberg town church , teacher at Wittenberg University and general superintendent of the Saxon spa district in 1523 . As a reformer he developed new church ordinances for Braunschweig , Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , Denmark , Hamburg , Hildesheim , Holstein , Lübeck , Norway , Pomerania and Schleswig . During the development of the church ordinances and the translation of the Bible, it has achieved lasting significance for the evangelical Lutheran church . As a friend of Martin Luther, he was not only his confidante and confessor , but also married Katharina von Bora , baptized their children and gave the funeral oration for Luther.

Life

Early years

Almost nothing is known about Bugenhagen's youth. His father Gerhard Bugenhagen was a councilor, possibly also mayor, in Wollin . The family received support from the Abbess Maria of the Cistercian monastery in Wollin, a sister of the Pomeranian Duke Bogislaw X. Bugenhagen probably attended school in Wollin until he was 16, because there were no indications of going to school in Szczecin. Then he enrolled on January 24, 1502 at the University of Greifswald and got to know the basic themes of Artes . In the summer of 1504 he left the university without having obtained a degree. At the end of the year he started out as a teacher at the city school in Treptow an der Rega and was appointed rector there.

Here he taught Latin and interpreted the Bible on his own initiative. He found interested listeners among the citizens of the city as well as the monks from the nearby monastery. The school's reputation reached as far as Livonia and Westphalia and attracted students from there. Although he had not studied theology, Bugenhagen was ordained a priest in 1509 and confirmed as vicar at the Treptower Marienkirche. He immersed himself in theology and was in contact with the humanist Johannes Murmellius in 1512 , who made him aware of the writings of Erasmus of Rotterdam . He kept in contact with the monks of Belbuck Monastery and exerted a strong influence there. In 1517 he was therefore given the position of a lecturer in the Belbuck Monastery at the monastic school set up shortly before by Abbot Johann Boldewan . On behalf of the abbot, he interpreted the Holy Scriptures and the church fathers here for the monks .

Also in 1517, Bugenhagen began work on a chronicle of Pomerania on behalf of his sovereign, Duke Bogislaw X. To do this, he went on an extensive journey through Pomerania to collect historical materials and traditions. On May 27, 1518 he handed the completed chronicle to the Duke with a dedication letter. This chronicle Pomerania , with slightly humanistic features, is the first coherent account of Pomeranian history, written in Latin and a model for the later High and Low German chronicles of Pomerania by Thomas Kantzow . Bogislaw X. was commissioned at the request of the Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony as a counterpart to a history of Saxony that is in progress.

Martin Luther's writings soon reached Bugenhagen . According to tradition, at a dinner with the Treptow clergy in the house of the pastor of the Marienkirche Otto Slutow (Schlutow) the landlord presented the tract "De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae, praeludium" ( From the Babylonian captivity of the church ) to Martin Luther. At first he is said to have dismissed this writing as heresy. But when he worked on it more carefully, a change of heart should have taken place in him. Because of this, he wrote to Luther to learn more about him. Luther remained friendly and sent Bugenhagen his “Tractatus de libertate Christiana” (treatise on the freedom of the Christian), which contained the sum of the understanding of faith developed by Luther at that time.

First years in Wittenberg

Studies and first lectures at the university

Inwardly touched by the new ideas, Bugenhagen went to Wittenberg in March 1521, where he entered into a close exchange of ideas with Luther and Melanchthon. In his time as a monk he still had a scholastic approach, although he tried to gain undisguised access to biblical thinking through a special turn to biblical hermeneutics . After he became acquainted with the writings of Johannes Murmellius , humanistic influences gained in importance when determining an authentic text in the Treptow era. When he encountered Luther's writings, his theological interest changed significantly. From now on, the concept of sin is no longer determined by the understanding of sin as a transgression of the commandments, but in the direction of his characteristic saying “Our whole life is sin, even after we have become righteous through Christ”.

The understanding of Scripture is entirely determined by justification (iustificatio impii) , in that Scripture and justifying faith in Christ are related to one another. Bugenhagen develops the theme of the justification of the sinner within the framework of a theology of temptation . In Wittenberg he wanted to develop this approach further and therefore enrolled on April 29, 1521 to hear the Reformation theology from a qualified mouth. In the Elbe city he was first accepted by Philipp Melanchthon , who took him into his house and at his table. Since November 3, 1521, he has given academic lectures on the Psalms published in 1524. Bugenhagen was an eyewitness to the events of the Wittenberg movement , but held back conspicuously. However, events have not left him unmoved. Through his marriage to Walpurga on October 13, 1522, he took a clear position on the question of celibacy .

Start of his activity as a city pastor

After the old parish priest Simon Heins died at the beginning of September 1523, Bugenhagen was elected as parish priest at the city church on October 25th, 1523 by the city council and the representatives of the community of Wittenberg on Luther's recommendation . In this capacity he proved to be a loyal follower of Luther, whose confessor and friend he became. His sermons, which he evidently liked to give, were often very long, which also provoked humorous criticism from Luther and his friends. Nevertheless, he unfolded the richness of the word in a simple but impressive way. He did not fail to address current issues in his sermons in order to give his congregation the necessary orientation for the Christian way of life.

Theological activity

In addition to the varied pastoral service, Bugenhagen continued his exegetical lectures at the university, edited lecture manuscripts for printing and authorized transcripts for publications. After numerous of his comments on Old and New Testament publications had appeared, his reputation as a Reformation interpreter was consolidated and made him known as a theologian beyond the borders of the empire. In September 1524, the city of Hamburg tried to get him, but this failed because of the objection of the council, which saw itself bound by the Worms Edict and found his marriage offensive. Even a one-year appointment to Danzig failed because of the veto of the Wittenberg municipality.

After the exegetical theological foundation, practical tasks in the church structure as well as pastoral theological problems increasingly began to determine his thinking and acting. In short writings he dealt with the organization and the right use of the Lord's Supper with confession and other ceremonies. In 1525 he wrote the congratulatory text De conjugio episcoporum et diaconorum on the marriage of the Lichtenburg preceptor of the Augustinian order Wolfgang Reissbusch. In it he welcomes the marriage of a clergyman as an order of God and tries to justify it theologically. This reflects an observable transition from the Reformation movement to shaping the Protestant church system. In this context it should not be left unmentioned that it was he who officiated on June 13, 1525 when Luther married Katharina von Bora .

Initially, he acted a little carelessly in this transformation process. He wrote to Johann Hess and argued against the interpretation of the words of institution and the resulting understanding of the Lord's Supper in Andreas Bodenstein and Huldrych Zwingli . When Zwingli replies directly to him, Bugenhagen gives in. Nonetheless, he ushers in a new stage in the Lord's Supper dispute, in which Luther and Zwingli took a direct stand against each other. He has not shown restraint here. Above all, he dealt with Martin Bucer and Johannes Brenz . In the following years, writings such as Letter to Christians in England or Christian Admonition to Christians in Livonia emerged, which show that Bugenhagen was not limited to his work in Wittenberg, but that his judgment and support were in demand in many places.

His work “From the Christian Faith and Right Good Works”, the “Sendbrief to the Hamburgers”, written in 1525 and printed in 1526 , describes the foundations of his Reformation theology and interpretation of church reform and called controversial theologians like Augustinus van Ghetelen on the scene. Because of the experience he had gained in shaping his congregation in Wittenberg, and his writing, Bugenhagen also gained reputation outside of Wittenberg. But he was first to experience the dark period of the plague that raged in Wittenberg in 1527/28, when he and Luther stayed on site to support his community and to give lectures to the remaining students on the first four chapters of the Corinthians.

Farewell to Wittenberg

Melanchthon and Justus Jonas the Elder , however, had left the city with their families and the university was relocated to Jena . After Bugenhagen's sister Hanna Rörer died of the plague in 1527 , Luther asked him to move into his house. Another stroke of fate struck him here when his two-year-old son Michael succumbed to an illness on April 26, 1528. In the meantime, negotiations between the city of Braunschweig and the University of Wittenberg had been held since March 1528 and were successfully concluded towards the end of April. The result was the posting of Bugenhagen to Braunschweig, where he and his family left on May 16.

Braunschweig

Arrival and general conditions

Four days later, on May 20, 1528, Bugenhagen arrived in Braunschweig, where he initially found accommodation with a citizen of the city. On the evening of the same day, all 13 Protestant preachers who were already active in Braunschweig gathered in the Andreas Church and had to recognize Bugenhagen as their teacher there by the laying on of hands.

In Braunschweig, the Lutheran teaching was spread by Gottschalk Kruse as early as 1521. The first mass in German was celebrated in the Braunschweig Cathedral at Easter 1526, despite the prohibition by the old church . The first baptism in German took place in the Advent season in 1527. The changes in worship life demanded by reform-minded clergy and the population took on ever clearer contours. On March 11th a council regulation had already been presented, which comprised 18 points, but left a few questions unanswered. At the end of March, two parishes had drafted a real reform program aimed at a thoroughgoing church reform. Therefore a comprehensive reforming and reorganization of the church system had become an inevitable necessity.

Start of activity in Braunschweig

On Ascension Day, May 21, 1528, Bugenhagen stepped into the pulpit for the first time in the overcrowded Brothers Church , which until the Reformation belonged to a Franciscan monastery . Numerous people who had not found a place had to make do with another preacher in the churchyard. First of all, Bugenhagen briefly gave an account of his appointment to the city, in order to then devote himself to the church feast day “ Ascension of Christ ”. In accordance with his Wittenberg custom of preaching twice on Sundays and public holidays, he stood in the pulpit again in the evening, just as he was a lively preacher. He was able to bring the Wittenberg theology to the Braunschweig people directly and, on top of that, from a qualified mouth. Increasingly, his sermons also gave him the lead to prepare his listeners for the church order, from the point of view that a properly understood church order emerges from the preaching of the gospel. He emphasized that good works belong to true and truly living faith and follow from justifying faith.

The Brunswick church order

In the basic questions of the church order , he said, among other things, that there must be learned preachers. These should primarily be superintendents who are supported by an assistant and must also be adequately cared for. So that theologians could meet the demands of the time, he created a biblical exegetical lectorium to train the preachers. He took up the topic of the abolition of the feast of Corpus Christi , as well as the problem of authorities, worked out the basics of the school system, regulated the welfare of the poor, made specifications for baptism and mass in German and began with catechism sermons . Although the Braunschweiger identified with his ideas of the church order, difficulties arose in their preparation. So the different interests, wishes and ideas often collided.

In order to give the future church order a uniform form that should be valid for the church system of the entire city and, if possible, a document to be adopted unanimously, an agreement had to be reached with empathy, patience, tact and negotiating skills. On September 5, 1528 it was done: The council, the council jury, the guild masters of the 14 guilds eligible for counseling and the 28 captains of the five soft forms of the city of Braunschweig, Altewiek , Altstadt , Hagen , Neustadt and Sack met and took the Bugenhagenscheid , which was written in Low German Church order in all forms. The following day, a Sunday, the officially sealed introduction of the Reformation in Braunschweig was announced from every pulpit in the city. After three and a half months of strenuous work, in which he had served as the city's first superintendent, the city officials asked Bugenhagen to stay.

Departure from Braunschweig

A house had already been made available to him for this purpose and he wanted to keep him as superintendent for life. However, new tasks were already waiting for the reformer. On the one hand, the city of Hamburg had been advocating him for a long time; The problems in Bremen had also come to a head with the death of Heinrich von Zütphen . For this reason, the Magister Martin Görlitz , who had been active in Torgau, was elected superintendent for Braunschweig on September 18, 1528 and was introduced to his office by Bugenhagen. The desired objective for the city was thus achieved, and Bugenhagen went to Hamburg with his family on October 10, 1528. As a result of Bugenhagen's reformatory activity, the cities of Braunschweig and Göttingen joined the Schmalkaldic League “on the Sunday after Trinity” in 1531 .

Hamburg

Arrival and general conditions

In Hamburg there had already been efforts in 1524 to appoint Bugenhagen as part of the advancing Reformation movement. In view of the circumstances at that time, however, the decision was not made according to the wishes of the Hamburgers. In the meantime, however, the Reformation ideas had already reached broad circles of the population at the beginning of 1526, so that the majority of citizens turned to the new doctrine. However, due to the popularity, the situation in Hamburg was not free of conflict. Again and again disputes flared up with the old-believing clergy of the Nikolaikirche, which led to an intensifying pulpit polemic and the discontinuation of traditional ceremonies. The council tried to calm the resulting unrest by attempting to admonish the opposing parties to Christian unity in a disputation at the town hall. However, it wasn't long before the problems reappeared.

Bugenhagen himself, who had already suggested the establishment of a “common box” (God's box order) for poor relief with the publication “Vom Christian Glaub und Rechts gute Werken”, printed in 1526 , thus laid a basic orientation for a church and community life. The forces of the Old Believers lost more and more authority, so that the Reformation side had already practically pushed through the Reformation due to its strong position. But what was needed in Hamburg was a personality who had a high degree of authority, had expertise and had experience to guarantee the security of the Reformation. Nikolaus von Amsdorff , who had already tried to take on this position in April, failed because he did not speak the Low German language. That is why they tried to get Bugenhagen to be appointed to Hamburg after his time in Braunschweig, because he was seen as the right person. The Hamburg Council reserved accommodation in the so-called “Doktorei”, which Bugenhagen moved into on October 8th when he arrived in Hamburg. On the following day, a festive welcome dinner was held in his house in his honor, and on October 10th the three Hamburg mayors greeted him in all manner.

The activity in Hamburg

But Bugenhagen soon realized that it was not possible to transfer the Braunschweig order to the situation in Hamburg. In spite of the advanced Reformation and the inclination of members of the order to the gospel, differences arose in Hamburg above all in disputes between the council, the citizenship and pre-reformatory tendencies in the monastic area. At first he began to give his sermons according to the same pattern as in Braunschweig. Here, too, the disputes with the rigid old-believing cathedral chapter and the nuns of the Harvestehude Cistercian convent , who did not allow Protestant preachers at their church institutions, were inevitable .

During his time in Hamburg he also took part in the Flensburg disputation against the teachings of Melchior Hofmann . He already knew this from his visits to Wittenberg in 1525 and 1527. Hofmann made himself known primarily because he represented a divergent, “enthusiastic” opinion of the Lutheran doctrine of the Lord's Supper and thus caused a lot of unrest in his areas of activity. As a result, he had already been expelled several times after having been proven to have deviating teachings. In 1527 he found refuge in Kiel , came out again with pamphlets, and there was a disputation on April 7, 1529 chaired by the Danish Crown Prince and Duke of Schleswig and Holstein , later Christian III. from Denmark . Hofmann argued in this negotiation according to a view similar to that of Zwingli and Bodenstein and explained: “The bread that we receive is figuratively and sacramentally the body of Christ, not truthful, but I do not consider it bad bread and wine, but it is me a memory ”. Bugenhagen, who gave the final word at this disputation, critically examined Hofmann's thoughts point by point in a comprehensive treatise. In doing so, he referred theologically and exegetically to the meaning of the Wittenberg understanding of the Lord's Supper and referred to the tradition of the words of the institution of the Lord's Supper in Holy Scripture. On April 11th Hofmann was convicted of being a false teacher. Since he refused to withdraw, he had to leave the country within five days.

The Hamburg church order

When he returned to Hamburg, Bugenhagen devoted himself again to drawing up the church ordinance, which for him meant an unwanted extension of his stay in Hamburg. Above all, the stubborn behavior of the Cistercian nuns of the St. Johannis monastery preoccupied him, so that he wrote the text "Wat me van dem Cluster leuende holden schal mostly sheared before de Nunnen vnde Bagynen" (Hamburg 1529), in which he wrote the monastery life as not criticized form of shaping life based on the Gospel. All efforts of the chapter at the Mariendom and the Cistercian nuns were unsuccessful. Bugenhagen had to ignore these points in his church order. Nevertheless, with his monastery pamphlet he had given the communities and the council an instrument so that afterwards, by demolishing the monastery on February 10, 1530, more radical measures could be taken. On May 15, 1529, the church ordinance was formally adopted, and on May 23, it was solemnly proclaimed from all pulpits in the city. After hard work, Bugenhagen had now also achieved his goal of a generally applicable church order in Hamburg. Above all, however, the survival of the old church system has a diminishing effect.

Despite the above-mentioned restrictions, with the adoption of the church order, the church system in Hamburg was finally converted to the Reformation principles in a binding form. It was laid down in it that “the pure word and the pure gospel freely” preached, the sacraments used in accordance with the institution of Christ, everything in church life that contradicts the word of God or that does not justify it, removed from the church of Christ, for the youth with good schools and the available or expected material resources should be used for the poor as well as for proper worship. A look at the situation in Hamburg shows the high degree of caution with which Bugenhagen, supported by the representatives of the Reformation municipalities, devoted himself to drafting the church regulations. The intermingling of theological penetration and organizational regulation also gave the Hamburg order the dual character of a basic document and, at the same time, instructions for the organization of the Lutheran church system in the city. In some respects, beyond the specific Hamburg objective, it formed a draft for the Christian way of life in an evangelical community with education and upbringing, preaching and worship, securing the spiritual and material prerequisites for evangelical preaching and, last but not least, guaranteeing the diaconal and social dimension of the evangelical Lifestyle. Bugenhagen had "given the Reformation form of faith the appropriate shape in church affairs" in Hamburg.

The establishment of the Hamburg Johanneum

Before returning to Wittenberg, he was able to open the Johanneum , the city's first public Latin school, with a festive Latin speech on May 24, 1529 in the vacated Johanniskloster , thereby demonstrating the great importance he, the former Treptower schoolmaster, had in the construction and the promotion of an effective Reformation school system. In doing so, he himself took the first step towards realizing the extensive and detailed provisions on the establishment and design of the city's Latin school formulated in the church ordinance. Due to an electoral recall to Wittenberg, Bugenhagen and his family left Hamburg on June 9, 1529. As a farewell gift and as an expression of gratitude for what had been achieved in Hamburg, he was presented with an honorary gift of 100 florins. His wife, who had apparently stood by him quietly and inconspicuously during this time, was also presented with 20 guilders.

Return journey and stay in Wittenberg

Another stay in Braunschweig

He wanted to travel back via Harburg and Braunschweig. In Braunschweig, Bugenhagen had to realize that the conditions there had developed extremely unfavorably. In the period since his departure in October 1528, there had been a strong reaction from the Old Believers. Duke Heinrich , too , had increasingly expressed his displeasure with the religious innovations in the city, which had an impact. In the spring of 1529 there was a relatively strong unrest in the city, not least because the council behaved in a tactical manner towards the duke and tensions had built up between the citizens and the council. At the same time problems arose with the monasteries, for which a clear procedural orientation was still lacking. The monks were expressly forbidden to leave their monasteries and to show themselves in public. Some of them then left the city, apparently reluctantly. This created further problems. The Duke obtained, not least against the background of the protest at Speyer , where the Reformation cause voted unfavorably and the Worms Edict was reinstated, a reprimand against Braunschweig, in which the city was asked to reopen the monks to allow.

At the same time, a spectacular iconoclasm in the city led to a progressive strengthening and effectiveness of imperative ideas, especially with regard to the transubstantiation doctrine of the understanding of the Lord's Supper . Soon after Bugenhagen's departure for Hamburg, several of the Reformation preachers began to represent positions in the doctrine of the Lord's Supper that had been expressly rejected as sacramentary in the church order. In the design of Lord's Supper celebrations, imperative influences came more and more into play. So there was an increasing danger of a division in the communities. Superintendent Görlitz was not able to counteract this development effectively, despite honest efforts, especially since the council did not provide sufficient support here either.

Immediately after his arrival in the city around Ascension Day in 1529, Bugenhagen intervened to regulate and clarify the confused situation, which was additionally burdened by demands from the Duke and the Imperial Regiment. He immediately tried to counteract the deviations in the understanding of the Lord's Supper with appropriate sermons. He was apparently able to move the council to take clearer action against the abusers of the sacrament. His efforts were ineffective. Although he had grown fond of Braunschweig's place of work, he had to follow the call of his elector and leave Braunschweig on June 20, 1529.

Short Wittenberg effectiveness

On the evening of June 24, 1529, he returned with his family to Wittenberg and was greeted by the council with a welcome drink. The Wittenberg parish had its pastor again, and Luther, who had represented the parish office for so long, was able to devote himself to his own tasks again. In Wittenberg, Bugenhagen himself was immediately involved in the preparations for the Marburg Religious Discussion . However, he did not take part in this; Instead, he devoted himself to the renewed discussion of the resistance question and took part in the drafting of the Torgau articles on the Augsburg Reichstag , which were included in Articles 22 to 28 of the Confessio Augustana . However, he did not take part in this Reichstag either, since he and Caspar Cruciger the Elder stayed at the town church in the interests of the Wittenberg community. Above all, he took advantage of the assistance for the progress of the Reformation in the Low German area. He represented Luther at the first church visits in the Saxon spa district, preached to his community and gave lectures at the university. While doing so, he read about 1st Corinthians. During this time, an only partially preserved interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles was created. When the conflict between Luther and Zwingli reached its climax, two representatives of the city of Lübeck approached him in June 1530 and asked him to draw up the church rules in their city. Therefore he went to Lübeck in October 1530.

Lübeck

Framework conditions and arrival

The old travesty city of Lübeck was pushed out of its middle position in the Baltic Sea trade at the time of the Reformation , as the Dutch expanded their trade into the Baltic Sea, England took its own trade and Denmark, as well as the Duchy of Prussia and the Hanseatic City of Danzig, assumed the dominance of Lübeck wanted to get rid of. The external difficulties increased internal tensions. Since 1522 a Reformation movement capable of action and gaining influence had developed in Lübeck. At the head of this bourgeois opposition were non-patrician merchants who called for an aggressive foreign policy towards the Netherlands and Denmark and did not see their interests sufficiently defended by the patrician council. This opposition hoped that the introduction of the Reformation would improve their social situation. Increased tax claims - u. a. the imperial Turkish tax - in the fall of 1529 made it possible for the bourgeois opposition to submit their demands to the council. It made the tax permit dependent on their fulfillment. A so-called “sixty-four” committee became the governing body of the opposition. In the summer of 1530, the council had to consent to the introduction of the Reformation. With this, the opposition succeeded in enforcing the demand for an evangelical reorganization of church life.

The Lübeck church order

In the agreement between the council and the community of June 30th, one of the demands is to create a binding order for church life (i.e. church, school and social welfare). So the question of Bugenhagen's appointment came into focus. On October 28, 1530, Bugenhagen arrived from Wittenberg with his family in the Hanseatic city, relatively willing, given the political importance of Lübeck. Luther again took over his representation in the Wittenberg parish office, but had no idea how long Bugenhagen would be occupied with this church-regulating work. Long work was required in Lübeck, too, which was undermined above all by the conservative council, which largely rejected the Reformation as an uproar.

Above all, however, Bugenhagen found support from the opposition, so that the church ordinance he had drawn up was finally passed and implemented on May 27, 1531. On Trinity Sunday, 1531, this was read out and celebrated in a festive service in all churches. After the resolution was passed, Bugenhagen, warned by the experience in Braunschweig and Hamburg, stayed in the city for almost a year to support the Reformation in Lübeck, which is important for the Protestant forces in the empire, with advice and action. As in Hamburg, the church ordinance led to the establishment of a Latin school , the Katharineum , in the premises of the Franciscans' St. Catherine 's Monastery . The first rector of the school and first superintendent of the Lübeck church was Hermann Bonnus , no doubt on Bugenhagen's recommendation.

Further work in Lübeck

During his stay in Lübeck, inquiries were sent to Bugenhagen several times from other locations in Lower Germany. The advice and judgment of the Reformation theologian, experienced in practical questions of church organization, were sought after. So the Rostock council turned to him with a request for an expert opinion on the existing problems of shaping Reformation church life. He also found time in Lübeck for literary work, which inevitably slackened off from Bugenhagen's various other stresses from around 1527. This is how, among other things, his writing “Against the Chalice Thieves” (1532), which is backed by rich material from church history and directed against the old religious practice of the Lord's Supper, was created there .

Induced by the agitation of the reformation outsider Johann Campanus , who has apparently appeared in the Lower Rhine region since 1530 with an idiosyncratic anti-Trinitarian doctrine , whose work Luther and Melanchthon also draw his attention to, he also writes against the anti-Trinitarian . In the last weeks of his stay in Lübeck, Bugenhagen, who had been involved in the creation of the Low German will in an advisory capacity in Wittenberg since 1524, worked on translating the Bible into Low German. As a result of this work, the magnificently furnished Lübeck Bible was published in 1533/34 , the first full Low German Bible, which went down in history as the “Bugenhagen Bible” even before Luther's High German Complete Edition . On April 30, 1532, he made his way back to Wittenberg.

Back in Wittenberg

Works as the main pastor of the Wittenberg parish

Returning to Wittenberg on May 5, 1532, Bugenhagen again faced an abundance of tasks. Luther, who had represented Bugenhagen, had taken care of the congregation, but he himself was bound by a variety of duties, and because of his temporary illness, the field service was exposed to considerable interruptions. Bugenhagen was supported by the deacons Sebastian Fröschel , Georg Rörer and Johann Mantel , but problems arose in the Christian life of the congregation which made him resign himself more than once. Because for the time being the Wittenberg community was not consolidated. However, he mastered this with tenacious persistence and imparted the foundations of Reformation faith and life to the community on the basis of the Bible and the catechism. A not insignificant factor may also have been his long sermons, which Luther criticized several times. Once he remarked ironically: “Every priest must have his own private sacrifice. Ergo the Pomeranus sacrifices his listeners through his long sermons, because we are his victims. And today he sacrificed us in an extraordinary way ”. If, as an exception, Bugenhagen came to the end earlier or had someone else replaced him, it could happen that the Wittenberg housewives were behind schedule with their lunch preparations when the family returned from the town church.

Appointment as doctor of theology

At the university, Bugenhagen lectured on the prophet Jeremiah. When, on April 28, 1533, the head of the Hamburg church box asked the Wittenberg theologians that Johannes Aepinus , who was elected superintendent of the city of Hamburg , should do a doctorate in theology, the Wittenberg faculty first realized how small the number of evangelical theologians had been. Because of the unclear legal situation, no theological doctoral doctorates had taken place since 1525. In the course of Aepinus' doctorate, the theological faculty made the decision to doctorate Caspar Cruciger the Elder , who had been sponsored for several years in the interests of the necessary improvement in teaching, and the Bugenhagen licentiate to doctorate in theology. The elector Johann Friedrich , who was in Wittenberg for deliberations and for whom the promotion of his state university was an urgent concern, supported the application. He paid the costs and offered to be present. On the evening of June 16, 1533 Melanchthon was still working out the theses to be defended.

The following day, in the Wittenberg Castle Church , chaired by Luther, in the presence of the Saxon Elector, Dukes Ernst and Franz von Braunschweig, Duke Magnus von Mecklenburg, as well as other nobles and representatives of the university, the disputation of the doctoral candidates took place in a brilliant setting Demonstration of new legal relationships held. For the Wittenberg doctorate should from now on emphasize the special qualifications of Protestant theologians in leading supervisory positions in cities and territories. Bugenhagen, who initially wanted to withdraw from the project by referring to his age, had to defend his six theses about the church (“De ecclesia”). He emphasized the obligations imposed on an evangelical office in relation to secular laws, provided they do not contradict the law of God. He distinguished from the church orders, which according to Col. 2, 16 could not bind the conscience. Opposed to them is freedom that cannot be abolished by any creature in the world. His remarks met with particular approval from the Elector. The next day, the dean of the theological faculty, Justus Jonas the Elder, held a meeting in the castle church. Ä. the solemn promotion of the three theologians completed. Luther had contributed the new doctoral formula, which stated that the doctorate would be carried out by virtue of apostolic and imperial political authority, both of which were attributed to God.

The general superintendent

The following day, a banquet, the so-called doctor's feast, was given at the castle by the elector. On this occasion, Bugenhagen was given the position of superintendent for the electoral district on the right bank of the Elbe . This was the first time that the office of general superintendent was introduced in the Protestant church, which was to last until 1817 (the provost of Kemberg initially took over the area on the left bank of the Elbe). According to Bugenhagen, the bishop's office of general superintendent was connected with the pastor's office at the Wittenberg town church. As a result, this office was carried out by the highest representatives of the theological faculty at Wittenberg University. Because the office was connected to the University of Wittenberg, it was transformed into a superintendent's office when it was moved to the University of Halle in 1817. The office developed out of the necessity of the church visits suggested by Luther, which have not yet been carried out in full. Gregor Brück (Pontanus), who processed the documents in 1527, recognized numerous grievances and problems that had already emerged during the first church visit. He therefore suggested to Johann the Steadfast to continue the visitations. The prince was not to experience this, however, and only his son Johann Friedrich undertook a second church visit in 1533. For this, church structures were required, from which among other things the office of general superintendent of the spa district arose.

The Wittenberg church order

Before Bugenhagen could devote himself to the visitations, he had to work out an official church order for Wittenberg. It sounds almost grotesque that Bugenhagen's actual place of work was still lacking a church ordinance, while in Braunschweig, Hamburg and Lübeck he had already drawn up Reformation church ordinances and put them into effect. In Wittenberg, of course, there was no real lack of church order. As early as 1522, during the time of the Wittenberg Movement, the council had issued regulations on January 24th, and then Bugenhagen and Justus Jonas the Elder had drawn up regulations for the ceremonies at the All Saints' Monastery (castle church). However, with Luther's “German Mass” in 1525 and his “Baptismal Book” from 1526, Bugenhagen with his concise “Order for the Wedding Ceremony ” in 1524 and again with Luther's “Little Grape Book for the Simple-Minded Pastor” in 1529, Wittenberg already had certain pre-forms of a regular church order.

It is therefore not surprising that the Wittenberg church order did not bring about any far-reaching changes in Wittenberg, but only laid down a lot of things that had already proven themselves. The structure of the Wittenberg order is similar to the north German order. Only two special features are noticeable. As was the case with Bugenhagen, the election of the city pastor had to be made by the representatives of the university and ten representatives of the council and the community, and the pastor's office was connected with the general superintendent for the right-Elbe area of the spa district. As a second peculiarity, Bugenhagen goes into Luther's recommendation to set up girls' schools and specifies them in the Wittenberg order compared to the north German orders. If Bugenhagen only intended reading in his North German church ordinances, he continues in the Wittenberg order and also wants to teach the girls to write and arithmetic. This means that specifically Christian content takes a back seat and the image of a “Christian housemother” is omitted. Subsequently, Bugenhagen was involved in the already mentioned church visits, which took him through Herzberg, Schlieben and Baruth in addition to his parishes, which are directly subordinate to the parish. During this time he stayed in Wittenberg only occasionally; further visitation trips led him u. a. in the office of Belzig. During this time he also took part in around 100 reports, whenever a statement was requested from the Wittenberg reformers, made recommendations on filling positions and advised on the introduction of the Reformation in Anhalt.

Pomerania

Framework

After the death of Duke Bogislaw X. the forces of the Reformation gained more and more foothold in the cities of Pomerania. On the one hand, Bogislaw had implemented an inwardly flexible religious policy, with limited tolerance of Protestant representatives as long as their sermons did not lead to an uproar. The then Bishop Erasmus von Manteuffel and Bogislaw's sons Georg and Barnim IX had to submit to this policy . continue this policy. In doing so, consideration was also given to imperial politics, because Pomerania was an imperial fief until 1530, and Charles V had decided on its award seven years after Bogislaw's death. That is why the Reformation was tacitly tolerated. After Georg's death in October 1532 the land was divided between Barnim IX., Who took over Pomerania-Stettin, and Georg's son Philipp I , who received Pomerania-Wolgast. During this division, emphasis was placed on maintaining the unity of the state and largely uniform governments were created.

Increasingly, several cities took the opportunity to intensify their striving, which had been pursued since the last decade of Bogislaw's rule, to regain the independence that had largely been lost or diminished by his domestic political reforms. The increasingly effective Reformation movement, which manifested itself primarily in evangelical sermons, the introduction of the German mass and the Lord's Supper in both forms, but did not lead to serious consequences for the organization of the church, was combined with this striving for independence on the part of the cities and democratic movements among the citizens . Some of them protested against mismanagement and sought at least a partial reorganization of the balance of power. After the pressure of the Reformation forces became more and more urgent, the Pomeranian dukes decided in the summer of 1534 to introduce the Reformation in their country. It was even intended to integrate the Bishop von Manteuffel into the reorganization of the church in order to create as little unrest as possible during the reorganization.

The Pomeranian Church Order

On December 13, 1534 a state parliament was established in Treptow a. R. held, including the bishop of Cammin, the monastery estates, the nobility, the cities, the evangelical representatives of the cities Christian Ketelhot ( Stralsund ), Paul vom Rode ( Stettin ), Johannes Knipstro ( Greifswald ), Hermann Riecke ( Stargard ), Jacob Hogensee ( Stolp ) and Johannes Bugenhagen were invited. However, no agreement could be reached. Nevertheless, the dukes enforced the draft resolution against the church representatives and the nobility as legal and valid. Bugenhagen was asked to draft church regulations for the duchy. This turned out to be difficult due to the controversial state parliament. So Bugenhagen was only able to work out a church order that took account of the needs and was practicable as the basis for the reformatory regional church to be created. A church order was required that concentrated on the essentials, but at the same time offered a sustainable and feasible basis for the design of a unified church system.

Apparently, by the beginning of January 1535, Bugenhagen had worked out a Pomeranian church ordinance in its final form, taking into account the state drafts, which immediately went to Wittenberg for printing and appeared in the same year. The church order itself is relatively short in relation to the order of the cities and does not contain the sermon-like theological justifications of the city orders. In it the subjects of the ministry, the "common castes" and the ceremonies are addressed. They are based on the elementary basis of the proclamation of the Gospel, to give space to the word of God in order to ensure a God-conforming life in the church. Under this aspect, explanations on the school system are also included, but the girls' schools are not mentioned as in his Wittenberg regulations. Here he also takes care of his former University of Greifswald and points out the importance of this institution for clerical and government agencies. With his recommendations in the Pomeranian church order, Bugenhagen created the canonical basis for the visitations he carried out, which were of extraordinary importance for the creation and consolidation of the Reformation church system.

Here he first invokes the express reference to the Confessio Augustana and its apology, which was later adopted in 1537 at the convent in Schmalkalden . He then explains how the ceremonies and feasts must be observed in order to get a direct reference to Jesus. At the end there are some liturgical texts and songs in German. The ordination of Johann Knipstro as general superintendent of Pomerania was a further step in the implementation of the church order. Bugenhagen's activity as a church reformer in Pomerania was thus largely over. However, he was still active as a mediator in the questions of the Pomeranian dukes and the Saxon electoral house.

Bugenhagen as a matchmaker

Bugenhagen also mediated Philip's courtship with Maria von Sachsen and in this connection traveled to Torgau in August 1535 to the court of Johann Friedrich for an examination of the bride, accompanied by Councilor Jobst von Dewitz and Chancellor Duke Barnims Bartholomaeus Suawe . Basic questions about the bride's treasure , the morning gift , the Wittum of Mary, the approximate date of the supplement, succession and other things were negotiated. After the marriage contract was concluded on February 25, 1536, Philip and Maria's wedding was celebrated in Torgau from February 27 to 29.

The political dimensions of this marriage were evident to all experts. They found their visible expression in the admission of Pomerania to the Schmalkaldic League soon after the Torgau wedding . The fact that the Pomeranian dukes subsequently turned out to be decidedly half-hearted members of the Protestant alliance cast a certain shadow over those events, but did nothing to change the fact that Pomerania was from now on regarded as a Protestant territory and belonging to the Protestant estates. With his activity in Pomerania, Bugenhagen had made a significant contribution to connecting his home country to the Reformation. Of course, he was only able to lay foundations, but he did so with his own deliberation, care and devotion and thus created something of lasting value. The expansion of the Pomeranian church into a Lutheran regional church and the full penetration of the entire country with the spirit of the Reformation Gospel remained tasks that would take decades to resolve.

The wedding of Torgau was thematized in 1553 on the so-called " Croÿ Carpet " and served the purpose of bringing together the different Lutheran doctrines that had emerged after the Schmalkaldic War into a "Tapetum Concordiae".

Bugenhagen becomes a professor

Returned to Wittenberg, he was accepted into the theological faculty as a full professor on September 19, 1535 with the dissertation "Quinta feria post Exaltationis crucis" and took over the fourth professorship at the theological faculty. Since the plague was rampant in Wittenberg at that time, he initially devoted himself to the supraregional ordinations that Luther wanted. This made Wittenberg the center of Lutheran Protestantism, and Bugenhagen increasingly assumed the role of a bishop of the Reformation. On May 26, 1536, Pommer took part in the Wittenberg Agreement with the Upper German Reformers and proved to be a negotiating partner who was willing to compromise, but also a persistent advocate of Luther's doctrine of the Lord's Supper. In the same form he also took part in the convent in Schmalkalden in 1537 and signed the Schmalkalden articles negotiated there .

Denmark

Framework

Due to the close relationships between the Hanseatic merchants, conditions were favorable for the Reformation to spread to the Nordic countries. In addition to other factors, such as the study of numerous students from Scandinavian countries in Wittenberg and the work of Lutheran preachers in these countries, this encouraged the acceptance of Reformation ideas in the trading cities. Its first sponsor was the Danish King Christian II , who had personal relationships with Wittenberg. In Denmark, townspeople and royalty and parts of the peasantry came together in the struggle for the new church against the high nobility. Since Christian II had made enemies by attempting to subjugate Sweden by force and by restricting Hanseatic privileges, he was expelled in 1523 by the nobility of his country, who found support in Sweden as well as in the Hanseatic cities. His uncle Friedrich I , the Duke of Schleswig and Holstein, ascended the throne . Friedrich achieved that on the gentlemen's day in Odense in 1527 the Lutherans were promised toleration. He was able to achieve the independence of the Danish Church from the Roman Catholic Church . In this way, he also secured the taxes that the church had previously collected. In 1531 Christian II was captured while trying to recapture his empire from Holland . After the death of Friedrich in 1533, Christoph von Oldenburg began the so-called " Count Feud ", a war against Friedrich's son Christian III, on behalf of his cousin Christian II . He was supported by the already Protestant cities of Copenhagen and Malmö, while the mostly Catholic nobility waited until almost total defeat before he met Christian III, who was known as a supporter of the Reformation. recognized as king.

When the disputes over the throne ended in 1536, Christian III. officially launched the Reformation in Denmark and Norway. On August 20, 1536, he had all bishops imprisoned who were his opponents during the last civil war, confiscated the church property in favor of the crown and took over the leadership of the church himself. Christian III wrote to the Elector of Saxony with the request that Bugenhagen and Melanchthon be sent to Copenhagen to promote the Danish efforts. However, this was refused because both were irreplaceable for the elector at the time. Again Christian III turned. on April 17, 1537 to the Elector and Luther. The latter he sent the draft church ordinance for Denmark for examination.

Arrival and work in Denmark

His employer Johann Friedrich I. put Bugenhagen on leave. Around June 10, 1537, Bugenhagen set out for Denmark with his family and his traveling companion. On July 5th, he arrived in Copenhagen after traveling via Hamburg, Holstein and Schleswig . Here he immediately devoted himself to editing the previously drafted Danish church ordinance. This was worked out by him in constant exchange with the Danish representatives. Before the church ordinance could be passed, Bugenhagen carried out the coronation of Christian III on August 12, 1537 in the Copenhagen Frauenkirche with great splendor in order to create the church political prerequisites . and his wife. On September 2, the inauguration of the first seven Danish superintendents took place. In both cases it was a clear break with tradition, because both coronation and ordination were reserved for bishops. The inauguration of the superintendent is still seen as an interruption to the apostolic succession in Denmark.

For the diocese of Zealand , whose seat was in Roskilde , but also included Copenhagen, Peder Palladius was installed . The University of Copenhagen , which was founded in 1479 and had suffered constant decline, was also reopened with a solemn ceremony on September 9, 1537 at the request of the king. Among other things, Bugenhagen was commissioned to take care of the start of teaching. After the church ordinance had been extensively revised, it was signed by the king on October 2nd and thus officially adopted. It then went to press and was published on December 13th. What is striking about the church order is the “King's Letter”, in which the king's firm will found expression to keep the leadership of the newly created Lutheran Church in royal hands. Previous efforts for a stronger church independence remained unsuccessful and resulted in a state church system .

Since the founding of the Schmalkaldic League, it was clear that the development and consolidation of Protestantism not only depended on the persuasiveness of Reformation sermons and theological arguments, but also required political power in order to protect itself against the latent threat from anti-reformist forces. Even the king, with his authority and his means of power, not only tolerated this church, but also placed himself at its head as a convinced and pious Lutheran Christian. He thus took care of their prosperity as a very own concern. It was necessary to prevent undesirable developments as early as possible in order to enable the Reformation to have church-based conditions in the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway. This developed between Bugenhagen and Christian III. a personal relationship that should last until the end of your life.

With the church order, a Lutheran basis had initially been created, which the church system in the dominion of Christian III. regulated. However, this did not include the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein , which he ruled only in personal union and which only received their own church ordinance in 1542. Financial security and the participation of clergy and congregations in shaping church life were readily granted in the church order. Recommendations were also given on teaching, clergy, ceremonies, schools, the parish caste, church libraries, and superintendents and provosts. However, as soon as clergymen were elected, the king was given the right of final confirmation. After the church ordinance was signed, Bugenhagen took on the main burden of implementing the goals set out in the church ordinance as the king's main advisor.

Teacher at the University of Copenhagen

Bugenhagen could after another request by Christian III. extend his stay in Copenhagen after he received the approval of the Elector of Saxony through Denmark's accession to the Schmalkaldic League . Lectures at Copenhagen University began on October 28, 1537. Bugenhagen had already drawn up a basic order for this, which he further elaborated in the “Fundatio et ordinatio universalis Scolae Hafniensis” . It was passed at the Diet of Odense on June 10, 1539. These university regulations contained all the rules necessary for the time and preferred (typical for the time) the theological faculty. It was determined that Palladius, as Bishop of Zealand, a permanent member of the university, and two other doctoral theologians should give lectures on the Holy Scriptures. Bugenhagen and Tilemann von Hussen initially worked at the faculty as temporary members . At the philosophical faculty, the main focus was on teaching Hebrew under Hans Tausen .

After initial difficulties, the university developed splendidly and Bugenhagen was given the honor of being appointed rector of the university on October 28, 1538 . Nonetheless, the outstanding questions about the implementation of the church order pressed him. For example at baptism, where he decided that the children would not be baptized naked but dressed. During school service, he pointed out that teachers should devote themselves to their task, and at the same time criticized some undesirable developments. He impressed the clergy on the strict interpretation of the church order. But Bugenhagen also tried to mediate in the dispute between the Dukes of Pomerania and Christian III. to work the island of Rügen . However, he soon realized that religion and imperial politics were handled differently in the house of Denmark. Many unresolved grievances made his initial enthusiasm wane over time.

Departure from Denmark

Bugenhagen's departure approached with the expiry of his clearance by the Saxon elector. After he had already left Copenhagen on April 4, 1539, he stayed for a short time at Nyborg Castle , where he wrote his marriage pamphlet and his letter to the superintendent. About Whitsun 1539 Bugenhagen stayed with Christian III. in Haderslev and took part in the Diet in Odense on June 9th . Here he experienced that the now improved church order in its final Danish version was confirmed in all forms by the Reichstag and thus became a state law. On the following day, the re-establishment of the university he was in charge of also received legally binding confirmation with the signing of the king. His almost two-year service in Denmark ended with a farewell sermon before the Reichstag. On June 15, 1539 he traveled with his family via Hamburg , Celle , Gifhorn , Haldensleben and Magdeburg , and arrived back in Wittenberg on July 4, where he received a keg of beer from the Wittenberg council. Contact with Denmark was still maintained. When the Bishop of Schleswig died in 1541, Christian III offered. Bugenhagen to the bishopric in Schleswig, which he refused for reasons of age. The same motivation seems to have formed the basis for the rejection of the Camminer bishop's chair .

Last years

Foreign Affairs

When he returned to Wittenberg, Bugenhagen managed a great deal of work. Among the Wittenberg reformers there were increasingly serious disputes (e.g. Luther - Agricola ), which led to tensions. In such an environment he took part in the revision of the Luther Bible from 1539 , in which he advised Luther in particular on the choice of words for certain terms from the Upper and Lower German language area. Bugenhagen was also sent abroad. In 1542 he was invited by King Christian III. to the state parliament in Rendsburg , where the Danish church regulations were also adopted for the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein after they had been translated into Low German and adapted to the conditions in the duchies.

Immediately after his return to Wittenberg, the Schmalkaldische Bund freed Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel from the anti-reformist Duke Heinrich von Braunschweig by force of arms . Bugenhagen was installed as provisional superintendent of the state and visited the parishes with Anton Corvinus and Martin Görlitz. On September 1, he took up his post in the episcopal city of Hildesheim , where on September 26 the citizens decided in favor of the Reformation. Although the visitations met with a friendly reception in the cities of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, the monasteries in the countryside in particular refused to allow the Reformation to enter. The indifference of secular officials and the devastation of church property that the war brought with it had also contributed to the fact that the reforms were unsuccessful. The church order for Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel of 1543, which is essentially the work of Bugenhagen, was the basis for the church order of Hildesheim in 1544.

In the 1540s he also wrote letters to the reformers in Transylvania , who constantly expanded Bugenhagen's range of activities.

After the death of Luther

Luther's death on February 18, 1546 shocked him very much. He gave Luther the funeral sermon on February 22nd as a "teacher, prophet and divine reformer" with a moving voice. After Luther's death, the main burden of responsibility for the future fate of Lutheran Protestantism rested on the shoulders of Melanchthon and Bugenhagen. When Charles V began to attack the Reformation by force of arms, Bugenhagen's situation became life-threatening. Charles V besieged Wittenberg, the university had been closed, and Melanchthon had left the city with most of the teachers. But Bugenhagen felt obliged to his Wittenberg community and, through his attitude, was able to encourage Caspar Cruciger the elder , Georg Rörer and Paul Eber to stay in the city. Bugenhagen's service was also particularly attentive to the imperial observers.

After the Wittenberg capitulation , Bugenhagen faced the new employer Moritz von Sachsen with the most contradicting feelings . Nevertheless, in the interests of the city and a longed-for peace, he tried to maintain a good relationship with the new elector. For this he was scolded by the supporters of the old elector, but achieved with his demeanor that the university in Wittenberg was resumed on October 24, 1547 and so the legacy of Luther could be maintained. From November 16, 1548 until the winter semester 1557/58 he was dean of the theological faculty.

When the emperor imposed the Augsburg Interim on the Protestants , this meant a re-Catholicization against which all Protestants resisted. The Elector Moritz also did not consider this to be feasible. Negotiations were then started in Celle , in which Bugenhagen also took part. The councilors of Electoral Saxony urged to give in as much as possible to the emperor from the Protestant position in order to avoid a new burgeoning war. The result was the Leipzig Articles , which although weakened the Augsburg Interim, nevertheless represented a major break in Lutheran theology. The Wittenberg theologians were again accused by the Gnesiolutherans of having betrayed Luther and the Reformation. These disputes intensified and resulted in the formation of parties in the Protestant camp. Bugenhagen also lost many former comrades-in-arms and friends from the theological disputes that followed.

Bugenhagen's last major work, the Jonah Commentary, showed how strongly he was moved by the disputes, which were conducted in an unpleasant tone and without a willingness to communicate, and how deeply the reproaches and suspicions hit him now that his life was gradually drawing to a close. This comment has become a detailed justification for him in view of the interim disputes, in which he proves his loyalty to Luther's teaching and in some cases develops violent polemics against the Catholic Church. Bugenhagen also worked on the Passion Harmony again during this time, with the aim of expanding it into a Gospel Harmony , but was unable to complete it. When Elector Moritz improved the position of Protestantism through his campaign against the emperor and the resulting Passau Treaty and the interim problem thus became irrelevant, Bugenhagen felt this turn of events as an answer to his pleading prayer. His prayer life evidently became more and more intense in these last years, just as he devoted himself to increasing internalization with advancing age and waning vitality.

Bugenhagen no longer had a closer relationship with Elector August , at whose court he was suspected of being an interim theologian. He seldom left Wittenberg on short trips. His work in the community and at the university claimed him. In the face of the Turkish threat , the Council of Trent and the impending danger of a fratricidal war between German princes, he often fell into a gloomy apocalyptic mood. Christian III from Denmark he describes his situation in Wittenberg on January 23, 1553 in a letter: “Here I preach, read lessons in schools, write, teach church matters, examinire, ordinire and send out many preachers, pray with our churches and command everything the heavenly Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ and with my dear lords and brothers I will be plagued by devils, lies, lesterers, hypocrites and other troubles, etc.… ”.

death

Three years later, the “Doctor and Pastor zu Wittenberg” wrote a “Vermanung to all pastors and preachers of the Euangelii in the Electorate of Saxony” with the request to read it out to the congregations in the course of the next Sunday services. In this last pastoral letter of the Bishop of the Reformation, he urged the congregation to confess their sins in the face of the evil times and to turn to the consolation that could only be found in God. So he took his pastoral responsibility fully until the end of his busy life. At the age of 72 he had to give up the ministry that he had always valued. After a rapid loss of strength and a short sick bed, Bugenhagen died of old age at midnight on April 19-20, 1558 , after the deacon Sebastian Fröschel had given him pastoral encouragement with words from the Bible. On the evening of the following day he was laid to rest in the church where he had preached the word of the Scriptures to his congregation for almost three and a half decades, and Melanchthon gave him the memorial address.

effect

Along with Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon, Justus Jonas and Caspar Cruciger, Johannes Bugenhagen is one of the most important old fathers of the Protestant Church during the Wittenberg Reformation. He emerged above all as the founder of the Lutheran church system in northern Germany and Denmark, as a long-standing pastor and teacher at the university there, as a close collaborator, friend and pastor of Martin Luther. He has made extraordinary contributions to the introduction and consolidation of the Reformation, whereby his particular effectiveness went beyond theological-theoretical categories, as he played a decisive role in shaping practical, legal and social aspects of the newly created denomination with his many regional and supra-regional church orders. In this respect he was - to use two modern expressions - ultimately Martin Luther's personal assistant and at the same time legal syndic of the Evangelical Lutheran Reformation.

As an exegete of his time, he was not only valued by the Wittenberg reformers. The Upper German reformers, such as Johannes Oekolampad , often took up his exegetical work and praised it. They were part of the standard equipment of a parish library at that time. The passion harmonies that arose from his lectures were widely used and were published as a kind of folk book from the Reformation period up to the 17th century, also in Polish and Icelandic. As an appendix to hymn books as far as Greenland and Finland, they have had a religious history.

A striking feature of Bugenhagen's oeuvre was his church ordinances, which, with the exception of the Danish ordinance, were written in Middle Low German , which was then common in northern Germany . They not only contain the new regulations for church administration, offices, schools, poor relief and church services, but also theological reasons for the regulations made. Bugenhagen pays special attention to a new understanding of worship and the Lord's Supper. He moves from easily understandable explanations to more complex theological arguments, and the style is based on sermons.

The church ordinances appeared in print and were read out in the churches after their resolutions. So they were not only aimed at church and administrative experts, but also at the entire community of believers in a community. His suggestions for school service stand out from the work on church ordinances. For the first time, Bugenhagen gives simple girls the opportunity to educate themselves. In his canon of education he wanted children to be educated to be capable people not only by their parents but also by school. Education is the task of the communities. The community also has to ensure the further training of the gifted but poor boys and girls. So he also developed the institutions for poor relief in his areas of activity and regulated them by setting up a "common box" (community treasure chest) based on the Wittenberg model. The close relationship between congregation and office in his church ordinances is the distinguishing feature of the interdependence of theological justification and legal thinking. As a result, these church ordinances also became templates for other church ordinances in northern Germany. Finally, April 20 commemorates Bugenhagen as a Protestant day of remembrance.

The aftereffects also include the fact that there are comparatively many churches in northern Germany that bear the name Bugenhagen Church and that the North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church awards the Bugenhagen Medal every year on Reformation Day .

The Pomeranian reformer also found its way into modern visual arts. On the occasion of the Luther Decade (2007–2017), the popular Pomeranian artist Eckhard Buchholz completed the impressive and large-format history picture “The Pomeranian Reformer Johannes Bugenhagen May 1535 in Stralsund” (oil, 96 × 122 cm). "(The) oil painting by Eckhard Buchholz turns out to be in the Luther Decade ... with a view to Pomerania as a representation of the epochal revolution in faith and human self-understanding that has continued to have an impact in the visual arts" . (L. Mohr 2014, p. 2). The portrait is open to the public with two other works of Christian content by the artist in Stralsund's St. Marienkirche.

Remembrance day

- Evangelical Church in Germany : April 20 in the Evangelical name calendar

- Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod : April 20

Memorials

- At the Berlin Cathedral there is a memorial plaque with various reformers, which also depicts Bugenhagen.

- There is a Bugenhagen monument in Braunschweig , which was created in 1970 by Ursula Querner-Wallner.

- In Bretten , in the memorial hall of the Melanchthon House, there is the Bugenhagen reformer statue, created by Fritz Heinemann.

- On the Rubenow monument in front of the main university building, inaugurated for the 400th anniversary of Greifswald University in 1856, Bugenhagen is depicted as a representative of the theological faculty as a full sculpture. Several new church buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries, u. a. in Szczecin , as well as streets and squares in Pomerania, were or still carry the name of Bugenhagen. Mention should also be made of the Croÿ carpet from the University of Greifswald , which is probably the most important testimony to the Reformation in northern Germany. This was dedicated to Doctor Pomeranus.

- In Hamburg there is a Bugenhagen monument by Engelbert Peiffer from 1885 in front of the current location of the Johanneum in Hamburg-Winterhude , as well as a brick sculpture from 1928 by Richard Kuöhl on the Bugenhagenkirche in Hamburg-Barmbek .

- In Hildesheim was 1995 Andreasplatz Bugenhagen fountain of Ulrich Henn built. It reminds of the first church ordinance of Hildesheim, which Bugenhagen wrote.

- In Lutherstadt Wittenberg there is a memorial plaque attached to the Bugenhagenhaus (Kirchplatz 9) in 1858. In 1894 a memorial created by Gerhard Janensch was erected on the church square . In the castle church there is a statue of Bugenhagen. A street was named in his honor.

- In his home town of Wollin , a memorial plaque was placed on the site of his parents' house.

Works (selection)

- Interpretatio in Liberum, Nuremberg 1523, 1524, Basel 1524, Strasbourg 1524, Wittenberg 1526.

- Interpretatio in Epestolam ad Ramanos, Hagenau 1523.

- Annotationes in Epistolas Pauli XI, posteriores, Nuremberg 1524, Strasbourg 1524, Basel 1524.

- Historia Domini nostri J Chr.passi et glorificati, ex Evangelistis fideliiter contracta, et annotationibus aucta, Wittenberg 1526, 1540, 1546.

- Oratio, quod ipsius non sit oponio illa de eucharistia ..., Wittenberg 1526.

- Confessio de Sacramento corporis et sanguinis Christi, Wittenberg 1528.

- Dat Nye Testame [n] t düdesch: With nyen Summarie [n] edder kortem board member vp eyn yder Capittel, Cologne, Peter Quentel, 1528.

- Johannes Bugenhagen's Pomerania . Edited on behalf of the Society for Pomeranian History and Archeology with the support of the Royal Prussian Archive Administration by Otto Heinemann (Sources for Pomeranian History, Volume IV), Stettin 1900. ( digitized version ).

- The merciful city of Brunswig christlike order to Denste the hilly Evangelio… / dorch Johannem Bugenhagen… bescreven. Wittenberg 1528, 1531.

- The honorable city of Hamburg Christian order, 1529 . Ed. And transl. by Hans Wenn. Hamburg 1971.

- The Keyserliken Stadt Lübeck Christlike Ordeninge, Lübeck 1531, text with translation, explanation. u. Introduction, ed. v. Wolf-Dieter Hauschild. Lübeck 1981, ISBN 3-7950-2502-8 .

- A writing against the chalice thief, Wittenberg 1532.

- De Biblie vth der vthlegginge Doctoris Martini Luthers yn dyth düdesche vlitich vthgesettet with sundergen vnderrichtingen alse men seen mach, Lübeck 1533, Fol. Magdeburg 1545.

- Kercken medals of the whole of Pamerland 1535, Wittenberg 1535, The Pomeranian Church Order, text with translation, explanation. u. Introduction, ed. v. Norbert Buske. Greifswald and Schwerin: Helms, ISBN 3-931185-14-1 .

- Ordinatio Ecclesiastica Regnorum Daniae et Norvegiae, ac Ducatumm Slesvici et Holstatiae, Copenhagen 1537.

- Biblia: dat ys de gantze Hillige Schrifft, Düdesch: Vpt nye thogerichtung, vnde with vlite corrigert, Wittenberg, Hans Lufft, 1541.

- The XXIX. Psalm interpreted, including from child baptism, Wittenberg 1542.

- Christian Kerken-Ordening in the land of Brunßwick Wolfenbüttelschen Deels, Wittenberg 1543.

- Church order of the city of Hildesheim, 1544.

- Historia des lydendes unde upstandige unses Heren Jesu Christi uth den veer Euangelisten = Low German Passion Harmony by Johannes Bugenhagen, ed. by Norbert Buske, facsimile print after d. Barther edition from 1586. Berlin and Altenburg 1985.

- Johannes Bugenhagen's Christian admonition to the Bohemians (1546), ed. u. a. by Gerhard Messler. Kirnbach 1971.

- Christian management of the merited Mr. Doctor Johann Bugenhagen / Pomerani / pastor of the churches in Wittenberg. To the laudable neighborhood / Behemen / Slesier and Lusiatier. Wittenberg by Hans Lufft 1546 and Kirnbach 1971 ed. u. a. by Gerhard Messler.

- Christian funeral sermon about D. Martin Luthern, Wittenberg 1546.

- A writing by D. Johann Bugenhagen Pomerani: Pastoris of the churches in Witteberg / To other pastors and preachers / From the present war armor, Wittenberg Print Hans Lufft 1546.

- How things went from Wittemberg in the place of this past war ..., Wittenberg 1548, Jena 1705.

- Commentarius in Jonam Prophetam, Wittenberg 1550.

literature

Press releases

- Lutz Mohr : From Christianization to the Reformation. Triptych for the "Luther Decade" complete. In: Die Pommersche Zeitung , vol. 64, volume 5 from February 1, 2014. P. 1 f.

Specialist literature

- Evangelical Church of Greifswald and Johannes-Bugenhagen-Committee (ed.): Mandatory legacy. Ecumenical Bugenhagen commemoration in Greifswald on the occasion of the Reformation in the Duchy of Pomerania 450 years ago and the 500th birthday of the reformer D. Johannes Bugenhagen, Pomeranus . Documentation of the festive day on June 24, 1985 in Greifswald and information on other events to commemorate Bugenhagen.

- Heimo Reinitzer: Tapetum Concordiae. Peter Heymans tapestry for Philip I of Pomerania and the tradition of the pulpits carried by Moses . Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-027887-3 .

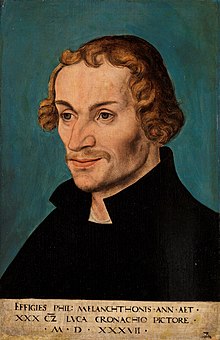

- Ferdinand Ahuis: The portrait of a reformer. The Leipzig theologian Christoph Ering and the alleged Bugenhagen picture by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Ä. from 1532 . Vestigia Bibliae 31, Bern / Berlin / Bruxelles / Frankfurt am Main / New York / Oxford / Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-0343-0683-6 .

- Kathrin Bauermeister: Johannes Bugenhagen and his reformatory work in Hildesheim Abbey. Self-published, Heyersum 2004.

- Ralf Kötter: Johannes Bugenhagen's doctrine of justification and Roman Catholicism. Studies on the Letter to the Hamburgers (1525), Research on Church and Dogma History 59, Göttingen 1994.

- Johannes Heinrich Bergsma : The reform of the mass liturgy by Johannes Bugenhagen. 1966.

- Hermann Wolfgang Beyer: Johannes Bugenhages life and work. 2nd edition, 1947.

- Anneliese Bieber / Wolf D. Hausschild: Johannes Bugenhagen between reform and reformation, the development of his early theology based on the Matthew commentary and the passion and resurrection harmony, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-525-55159-2 .

- Yvonne Brunk: The baptismal theology of Johannes Bugenhagen. Verlag Ggp Media on Demand, Hanover 2003, ISBN 3-7859-0882-2 .

- Georg Buchwald: Unprinted sermons by Johann Bugenhagen ad J. 1524–1529 . Heinsius Verlag, Leipzig 1910.

- Norbert Buske : The Pomeranian church order by Johannes Bugenhagen. Text with translation, explanation and introduction. Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin 1985, ISBN 3-931185-14-1 .

- Norbert Buske: A Bugenhagen portrait in England. The Wittenberg reformers embedded in humanism. In: Pommern 39. 2, 2001, pp. 24-27.

- Norbert Buske (Ed.): Johannes Bugenhagen: Pomerania First overall presentation of the history of Pomerania. Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin 2008, study edition Schwerin 2009, ISBN 978-3-940207-10-4 .

- Norbert Buske : Johannes Bugenhagen. His life. His time. Its effects. Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin 2010, ISBN 978-3-940207-01-2

- Irmfried Garbe, Heinrich Kröger (ed.): Johannes Bugenhagen (1485–1558). The Bishop of the Reformation. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-374-02809-2 .

- Georg Geisenhof: Bibliotheca Bugenhagiana. Bibliography of the publications of D. Joh. Bugenhagen . Leipzig 1908, M. Heinsius Nachf.

- Ludwig Hänselmann : Bugenhagen's church regulations for the city of Braunschweig based on the Low German print from 1528 with a historical introduction, the readings of the High German arrangements and a glossary, Verlag Zwißler, Wolfenbüttel 1885 ( digital copy ).

- Wolf-Dieter Hauschild / Anneliese Bieber-Wallmann: Johannes Bugenhagen. Works Volume 1 1518–1524 . Publishing house Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013.

- Wolf-Dieter Hauschild (Ed.): Lübeck Church Ordinance by Johannes Bugenhagen 1531 . Schmidt-Römhild, Lübeck 1981, ISBN 3-7950-2502-8 .

- Annemarie Hübner, Hans Wenn: Johannes Bugenhagen - The honorable city of Hamburg Christian order 1529. De Ordeninge Pomerani . Hamburg 1976, 1991.

- Ralf Kötter: Johannes Bugenhagen's doctrine of justification and Roman Catholicism. Studies on the Letter to the Hamburgers (1525) . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997.

- Hans-Günter Leder: Johannes Bugenhagen - Shape and Effect Contributions to Bugenhagen research on the occasion of the 500th birthday of Doctor Pomeranus . Ev. Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1984, license 420.205-34-84. LSV 6330. H 5485.

- Hans-Günter Leder & Norbert Buske: Reform and order from the word. Johannes Bugenhagen and the Reformation in the Duchy of Pomerania . Berlin 1985.

- Hans-Günter Leder: Johannes Bugenhagen Pomeranus - From reformer to reformer. Biography studies (= Greifswalder theological research 4), ed. Volker Gummelt 2002, ISBN 3-631-39080-7 .

- Hans Lietzmann (Ed.): Johannes Bugenhagens Braunschweiger Kirchenordnung 1528. Verlag Marcus & Weber, Bonn 1912.

- Werner Rautenberg (ed.): Johann Bugenhagen contributions on the 400th anniversary of his death. Evangelical Publishing House, Berlin 1958, License No. 420.205-115-58.

- Christopher Spehr: Reformer children. Early modern beginnings in life in the shadow of important fathers. In: Lutherjahrbuch 77 (2010), pp. 183-219, especially pp. 211-216.

- Karlheinz Stoll and Anneliese Bieber: Church reform as a service. The reformer Johannes Bugenhagen 1465–1558. Lutherisches Verlagshaus, Hanover 1985, ISBN 3-7859-0526-2 .

- Karl August Traugott Vogt : Johannes Bugenhagen - Pomeranus - life and selected writings. RL Fridrichs, Elberfeld 1867. ( digitized in the Google book search)