Slupsk

| Slupsk | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | District-free city | |

| Area : | 43.15 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 54 ° 28 ' N , 17 ° 2' E | |

| Residents : | 90,769 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 76-200 - 76-210, 76-215, 76-216, 76-218, 76-280 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 59 | |

| License plate : | GS | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 6 ( E 28) Gdansk ↔ Szczecin | |

| DK 21 → Trzebielino - Miastko | ||

| Ext. 210 Ustka ↔ Dębnica Kaszubska - Unichowo | ||

| Rail route : | Gdańsk – Stargard railway line | |

| Piła – Ustka railway line | ||

| Next international airport : | Danzig | |

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 43.15 km² | |

| Residents: | 90,769 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 2104 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 2263011 | |

| Administration (as of 2018) | ||

| City President : | Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka | |

| Address: | Plac Zwycięstwa 3 76-200 Słupsk |

|

| Website : | www.slupsk.pl | |

Słupsk [ ˈswupsk ], German Stolp , is a city in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship and the administrative seat of the district of the same name .

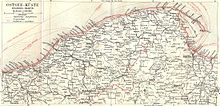

Geographical location

The city is located in Western Pomerania on the banks of the Stolpe (Słupia) river , around 18 kilometers from the Baltic Sea coast at an altitude of 26 meters above sea level, and extends over an area of 43.15 square kilometers.

The neighboring cities of Koszalin (Köslin) in the southwest and Lębork (Lauenburg i. Pom.) In the east are about 70 kilometers and 50 kilometers away, respectively. The distance to Gdansk in the east is about 110 kilometers and to Stettin in the southwest about 190 kilometers.

history

The Stolper Bär , an amber figure that was found near Stolp before 1887, dates back to prehistoric times . It is exhibited in Szczecin today .

In the 9th century, a Kashubian settlement was built on the east bank of the Stolpe River, at a flat ford, and soon afterwards a castle. In old documents, Stolp is written as Ztulp , Slup , Slupz , Ztulpz , Schlupitzk and Schlupz . A village called Slup was mentioned in a document as early as 1013. The name is possibly derived from the Old Slavic word stlŭpŭ for column or stand - that is, from the fish stand in the river, a device for fishing. A castellany, also known as Land Stolp , belonged to the castle. The trade route from Danzig to Stargard led through the ford at Stolp . From the 12th century the settlement was part of the Duchy of Pomerania , ruled by the noble family of the Griffin , which was under Polish influence from 1121, German from 1181 and Danish from 1186 to 1227.

After a sideline of the griffins died out due to the death of Duke Ratibor II and the collapse of Danish supremacy over Pomerania, the Stolper Land and Stolp Castle came into the possession of the Dukes of Pomerania from the Samborid dynasty in 1227 and remained so until its extinction in the male line in 1294. The Duchy of the Samborids had achieved complete independence from Krakow in 1227, after the assassination attempt on Duke Leszek I under Swantopolk II . In 1240, Stolp is mentioned as the location of a certificate from Swantopolk II, in which he exchanged the village of Ritzow in Stolper Land (Latin for dyocesi Zlupensi ) for two horses for his chaplain Hermann . Duke Swantopolk II. Of Pomerania in 1265 gave the town the city charter by Lübischem law . In 1276 merchants and craftsmen from Westphalia and Holstein founded a new settlement on the west bank of the river. Two years later a Dominican monastery was founded. After Duke Mestwin II died in 1294 without leaving a male heir, the Pomeranian succession dispute broke out . Although Pommerellen had shaken off the sovereignty of the Krakow dukes in 1227, Mestwin II had concluded a succession treaty in Kempen in 1282 without consulting the Pomeranian Griffins and without considering earlier contracts with Przemysław II , then Duke of Greater Poland . This led to the fact that after Mestwin II's death, Polish and Bohemian rulers tried to succeed the rulers in Pomerania, one after the other: Przemysław II (1294-1296), Władysław I. Ellenlang (1296-1299 and 1306-1308), and Wenceslaus II. (1299-1305). Wenceslaus III , the successor of Wenceslas II and Polish titular king , awarded the lands of Schlawe and Stolp to the Brandenburg Ascanians in exchange for the Lausitz region and an alliance against Władysław I. Ellenlang. The Brandenburgers had already bought up the liens on these lands from Wizlaw II , Prince of Rügen, in 1277 . After the fatal attack on Wenceslaus III. Władysław I. Ellenlang prevailed again in 1306 as ruler of Pomerania. The Swenzonen , high Pomeranian administrative officials, were previously entrusted with the administration of Pomerania by the kings of Bohemia. These fell out with Władysław I. Ellenlang and declared themselves Brandenburg vassals in 1307. In 1308 the Brandenburg margraves marched on behalf of the Swenzones in Pomerania and tried to enforce their previously acquired rights militarily. But in the same year they were ousted from Danzig and the eastern parts of Pomerania by the Teutonic Knights . But they were able to hold their own in the Land of Stolp. Margrave Waldemar finally entrusted the Swenzonen family with the administration of the land .

In 1309 the Polish Duchy of Pomerania was effectively divided between two German feudal states in the Treaty of Soldin . The western part with the states of Stolp, Schlawe, Rügenwalde and Bütow went to the Brandenburgers, the larger part with the main fortress of Danzig to the Teutonic Order . On September 9, 1310, Stolp's Lübische right granted to the city in 1265 was expanded by Margrave Waldemar and confirmed again in 1313.

In 1317 , the Pomeranian Duke Wartislaw IV. Acquired the Brandenburg property of Pomerania, including the town and country of Stolp, from the Griffin family and tied them more closely to the Griffin family. After Stolp became prosperous, the citizens acquired the port of Stolpmünde and the village of Arnshagen in 1337 . Between 1329 and 1388 the city was pledged three times to the Teutonic Order by the Pomeranian dukes Bogislaw V , Barnim IV and Wartislaw V , who had run into financial difficulties due to numerous wars. Because the dukes could not redeem the city, but the residents did not want to live under the rule of the order, the citizens themselves raised the transfer fee of 6,766 silver marks according to Luebisch weight . That was an enormous amount for the time. In 1365 Stolp became a member of the Hanseatic League and in 1368 was granted the right to mint finch's eyes .

In devastating fires of 1395 and 1477, the city burned down except for the town hall, remains of the city fortifications with a few gate towers, the churches and a few houses. In 1478 the plague raged in the city. In 1497 a flood caused great damage. In 1481 Stolp took part in a peace alliance between the Pomeranian and penal cities. In 1507, Duke Bogislaw X. had the Stolper Castle built. The city was repeatedly ravaged by fires and epidemics between 1544 and 1589. Around two thousand people were killed. Years of dispute with the dukes left the city impoverished and forced them to withdraw from the Hanseatic League. In 1630 Stolp was conquered by Sweden in the Thirty Years War . Wallenstein's troops occupied the town in 1637. Swedish troops under General Banner drove it out and completely ruined Stolp. After the end of the war in 1648, Stolp fell to Brandenburg in the Peace of Westphalia, like all of Western Pomerania . In 1655 the city was ravaged again by a fire. In the 17th and 18th centuries, cruel witch trials took place in Stolp. In the winter of 1708/09 there was very strong frost in Western Pomerania, and in February 1709 the Stolpe flooded after heavy rainfall, and the area from the city wall to the old town was flooded.

In 1769 Frederick the Great founded a cadet institute for the Pomeranian nobility in Stolp on the recommendation of his chief finance, war and domain councilor Franz Balthasar Schönberg von Brenkenhoff . The institution, which stood on the corner of Langen Strasse near the castle, was initially only designed for 48 cadets, who were taught, accommodated and fed free of charge. In 1777 the cadet house received extensions; For this purpose, two adjacent town houses were bought and demolished. The number of cadets was then increased to 96 in 1778; in the three-story cadet house was taught in six classes. In 1793, 96 cadets were also trained there. One of the teachers at the school was the well-known topographer and non-fiction author Christian Friedrich Wutstrack . There were also Royal Prussian cadet schools in Berlin , Potsdam , Kulm and, since 1793, in Kalisch . In 1788 Wutstrack founded a public library in Stolp, which contained several thousand volumes. The Wutstrack library was later partially incorporated into the cadet school.

During the Franco-Prussian War between 1806 and 1807, Polish troops formed from insurgents who had invaded Pomerania succeeded in occupying Stolp for a week on February 19 .

From 1807, Stolp was the only such institution in Prussia due to the loss of the cadet institutes in Kulm and Kalisch and the closure of the cadet institute in the Potsdam military orphanage . It was therefore moved to more central Potsdam in 1811; The city used the building in Stolp as a home for the disabled.

After the Prussian administrative reforms after the Congress of Vienna , Stolp belonged to the district of the same name in the administrative district of Köslin in the Prussian province of Pomerania from 1816 and became the seat of the district administration. In 1848 the Stolper shipowners had 25 merchant ships. In 1857 Stolp received a grammar school. In 1862 a gas works was put into operation in Stolp. The Köslin – Stolp railway line was opened in 1869, followed by the extension to Sopot a year later, and the Stolp – Stolpmünde line in 1878 . In 1894 the construction of the circular railway to Rathsdamnitz began. On April 1, 1898, Stolp left the district and formed its own urban district with around 26,000 inhabitants . Construction of the new town hall began in 1899 and was completed with the inauguration on July 4, 1901. At the beginning of the 20th century, Stolp had an old castle, a new town hall, a Bismarck monument , a grammar school connected to the upper secondary school, a fräuleinstift and was the seat of a regional court. In 1910 the Kaiser Wilhelm monument was inaugurated on the town hall forecourt in the presence of the imperial family.

In 1910 Stolp got a tram network with four lines in meter gauge and in 1926 an airfield .

Until the Second World War , Stolp was a garrison location and a commercial town with an important furniture industry, amber processing, machine factories and embroidery. Stolp became known beyond the Pomeranian borders, among other things, through the Camembert Stolper Jungchen, which has been produced there since August 21, 1921 in the cheese dairy of the southern German manufacturer Heinrich Reimund . This soft cheese is now back in the km 25 of Slupsk City Zielin remote (dt. Sellin ) produced.

Around 1930 the district of Stolp had an area of 41.9 square kilometers and there were 2,271 residential buildings in eleven different residential areas in the city area:

- Covering shop

- At the Dornbrink

- Expansion at Gumbin

- Chausseehaus near Neumühl

- Hildebrandtshof

- Wage Mill

- Saint George

- Schützenheim

- Stumble

- Forest hangover

- Fulling Mill

In 1925 there were 41,605 inhabitants in Stolp, who were distributed over 10,921 households.

In 1938 the radio station Stolp was established.

Women pen

In 1288 a Premonstratensian nunnery was founded in Stolp , which was subordinate to the abbot of the Belbuck monastery. After the Reformation in Pomerania, Duke Barnim II moved in the property of the women's monastery in 1669 and allocated certain income to the women of the monastery. This enabled this church institution to continue to exist as a women's foundation.

Parties and elections until 1945

Politically, Stolp was considered a liberal stronghold until the First World War . The Progressive People's Party (FVP) won 43.3% of the vote and the SPD 30.9% in the 1912 Reichstag election . In the Weimar Republic, the picture changed. In the 1924 Reichstag election , 44.3% of the residents of the German National People's Party (DNVP) voted. One reason for this was the feeling of insecurity that arose after Stolp suddenly found itself in a border region due to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty and the resulting separation of the Polish Corridor - the new Polish border was only about 50 km away from the city.

Before the National Socialist takeover of power on January 30, 1933, the city parliament of Stolp with 37 seats was composed as follows: 17 civil unity lists, 15 SPD, 2 NSDAP , 1 DDP, 2 others. In the last free Reichstag election in Stolp on November 6, 1932 , 36.1% voted for the NSDAP, 24.4% for the SPD, 23.0% for the DNVP and 7.8% for the KPD.

After the takeover of power, freedom of opinion was no longer guaranteed. Nevertheless, on March 12, 1933, the NSDAP was unable to win a majority in the city parliament with 16 seats, the SPD and the Black-White-Red (KSWR) each won 10 seats. In the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , the National Socialists did not receive a majority of votes from Stolp either; 49.5% voted for the NSDAP . With the introduction of the Prussian Municipal Constitutional Law of December 15, 1933 and the German Municipal Code of January 30, 1935, the leader principle was enforced at the municipal level on April 1, 1935 .

In the Reichsbahn repair shop in Stolp there was an external labor camp of the Stutthof concentration camp .

Expulsion and the time after 1945

On March 8, 1945, the Red Army took Stolp without a fight and burned down the city center the following night. The city was placed under the administration of the People's Republic of Poland in April 1945 . She introduced the place name Słupsk for Stolp , drove out the established inhabitants until 1947 and settled the place with Poles .

From 1945 to 1950 Słupsk belonged to the administrative region III ("Pomorze Zachodnie", West Pomerania) formed in March 1945, which from 1946 was called the Szczecin Voivodeship ("Województwo szczecińskie", 1945-1950), then until 1975 to the Koszalin Voivodeship . During the existence of the Slupsk Voivodeship between 1975 and 1998, it was its capital. Since 1998, Slupsk has belonged to the newly formed Pomeranian Voivodeship .

Current condition

Today the city is an industrial center of the region; Agricultural machinery, ship accessories, furniture, confectionery, shoes, household goods and cosmetics are manufactured in the city. Large shopping centers emerged in the periphery. The Słupsk Special Economic Zone in the north of the city has offered tax breaks for companies wishing to settle here for a period of ten years since 1997. Słupsk is also home to many educational institutions. There is a teaching college, a marketing and management college, various high schools and technical colleges. Culturally, Słupsk attracts with many historical buildings, the Central Pomeranian Museum, the city orchestra, a theater, a puppet theater, galleries, libraries and cinemas. Because of its proximity to the Baltic Sea and the seaside resort of Ustka (Stolpmünde) , the city is also a tourist center in summer. The Swepol high-voltage direct current transmission substation has been located near Slupsk since 2000 . 2014, the city was awarded the European Prize awarded for their outstanding efforts to idea of European unification.

Demographics

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1600 | approx. 3,800 | |

| 1650 | 2,200 | |

| 1740 | 2,599 | |

| 1782 | 3,744 | including 40 Jews . |

| 1794 | 4,335 | including 39 Jews. |

| 1812 | 5,083 | including 55 Catholics and 63 Jews. |

| 1816 | 5,236 | 58 Catholics and 135 Jews. |

| 1831 | 6,581 | including 36 Catholics and 239 Jews. |

| 1843 | 8,540 | 58 Catholics and 391 Jews. |

| 1852 | 10,714 | including 50 Catholics and 599 Jews. |

| 1861 | 12,691 | 45 Catholics, 757 Jews, one Mennonite and 46 German Catholics . |

| 1875 | 18,328 | |

| 1880 | 21,591 | |

| 1885 | 22,442 | |

| 1890 | 23,862 | of which 669 Catholics and 832 Jews |

| 1900 | 27,293 | including 25,628 Evangelicals and 769 Catholics |

| 1905 | 31,154 | with the garrison (a regiment of hussars No. 5), of which 951 were Catholics and 548 Jews. |

| 1910 | 33,762 | thereof 31,728 Evangelicals and 1,100 Catholics |

| 1925 | 41,602 | 39,678 Protestants, 1,200 Catholics, 18 other Christians and 469 Jews |

| 1933 | 45,299 | thereof 43,220 Evangelicals, 1,275 Catholics, three other Christians and 389 Jews |

| 1939 | 48,060 | of which 44,628 Protestants, 1,460 Catholics, 698 other Christians and 209 Jews |

- Population development until today

Districts

- Nadrzecze

- Ryczewo (Ritzow)

- Śródmieście (inner city)

- Słupska Specjalna Strefa Ekonomiczna (SSSE for short, Special Economic Zone)

- Westerplatte

- Zatorze

Religions

From the Reformation until the end of the war in 1945, the majority of the population of Stolp was Protestant. At the beginning of the 20th century, Stolp had four Protestant churches (including the Marienkirche with a high tower and the Johannis- or Schlosskirche, built in the 13th century, formerly a church of a Dominican monastery ), a Catholic church and a synagogue .

Most of the Polish migrants who immigrated after the end of the war in 1945 were also Christian and belonged to the Roman Catholic Polish Church.

traffic

The city is located at the intersection of Landesstraße 6 (formerly Reichsstraße 2 , now also Europastraße 28 ) with Landesstraße 21 (formerly Reichsstraße 125 ) as well as the Voivodship roads 210 and 213 . It is also the railway junction of the two state railway lines 202 and 405 on the line from Stargard to Gdansk and the line from the Piła – Ustka line ( Schneidemühl - Stolpmünde ).

A tram network was in operation between 1910 and 1959. Trolleybuses ran in the city between 1985 and 1999 .

The Słupsk-Redzikowo airfield ( ICAO code: EPSK) is located in the Redzikowo (Reitz) district of the rural community .

Attractions

Buildings

- Duke Bogislaws X. castle from the Griffin family: It was built in 1507 and rebuilt in the Renaissance style between 1580 and 1587. After it was destroyed by fire in 1821, it served as a grain store for a long time (until 1945). After the Second World War, it was restored to its appearance in the 16th century. Today it houses u. a. the Central Pomeranian Museum with the “Treasures of the Pomeranian Dukes” on the ground floor. The picture gallery from the 14th to 18th centuries and the former knight's hall are located on the 1st floor, but are reserved for events etc.

- The city gates: The new gate , diagonally opposite the town hall forecourt, is a late Gothic brick building built around 1500. The vault-like gate underpass was expanded into a shop after the Second World War. The “Mühlentor” in the castle area stands on the mill canal and barred the road to Danzig and Schmolsin. It is one of the oldest structures in the city. It was partially damaged in World War II, but it was restored. Since 1980 the workshops of the museum curators and documentators have been located there.

- The “manor house”: The building is located on the site of the former ducal riding stables. It is built in half-timbered style and is attached to the mill gate. Now it includes the library, the archive and the administration of the museum parts.

- The "Richter-Speicher": This warehouse is behind the mill gate and is built as a half-timbered building. The roof is a stepped hipped roof. It was built in 1780 and now houses another part of the museum.

- The St. Hyacinth Church (Kościół Świętego Jacka ), formerly St. John's Church or Palace Church, immediately northwest of the Ducal Palace. It houses the grave monuments of Ernst Bogislaw von Croÿ († 1684), nephew of the last Duke of Pomerania, and his mother Duchess Anna von Croÿ († 1660).

- Castle mill: The castle mill, built in the first half of the 14th century, is part of the castle complex. It is a partially plastered brick building that was originally added to the 19th century. But it was changed significantly in the following centuries. The free north-eastern gable side is listed as a framework. The mill was extensively reconstructed from 1965 to 1968, and the components from the 14th century were discovered. After that, a branch of the museum was set up here to house the ethnographic exhibitions.

- Parish Church of St. Marien: A large Gothic brick basilica built around the turn of the 14th century with a mighty west tower, which is steeply inclined and crowned with a Baroque helmet from the 18th century.

- St. George's Chapel : a small octagonal late Gothic brick building built in 1492. Originally a hospital chapel on Hospitalstrasse, after a fire in 1681 rebuilt with baroque changes and moved to the new location in 1912.

- Nikolaikirche of the Premonstratensian Monastery: A late Gothic brick building from the 14th century, which was converted into a school at the time of Frederick the Great, called the monastery school before 1945 . Therefore, the ship is now divided into floors. Part of the premises is used today as a Protestant church.

- Kreuzkirche : built from 1857 to 1859 in simple neo-Gothic forms for the congregation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Prussia , used by the Evangelical Augsburg Church in Poland since 1945 .

- Town hall: Built between 1900 and 1901 in neo-Gothic brick style, with a 59 m high tower. The interiors are adorned with leaded glass windows and paintings. In the ballroom there is a glass painting with the coats of arms of the Pomeranian noble families.

- Witches' Bastion: Originally a part of the fortifications connected to the city wall that was built between 1411 and 1415. In the 17th century the building was converted into a prison for alleged witches, which was used until 1714. The first witch trial took place in Stolp in 1651. According to archival sources, a total of 18 women were executed (burned at the stake) of the women imprisoned, including a lady-in-waiting of Princess Anne of Croy . In the 19th century the building served u. a. as a warehouse. Today (2008) art exhibitions take place there.

- The old post office: A brick building from the 19th century.

- Butcher's shop: with a very well-preserved Art Nouveau interior design and tiled interior walls, which still houses a butcher's shop today.

- Upper bourgeois buildings: Some representative upper bourgeois buildings from the Wilhelminian era have been preserved in the city, such as the Hotel Zum Franziskaner from 1897 - today's (2008) Hotel Piast .

Monuments

- Commemorative plaque at the 1st community school to commemorate the deportation of the Jews, inaugurated in 2008. The inscription reads in German and Polish: “To commemorate the deportation of the Jews from Stolp and the eastern part of Pomerania in July 1942. This building was then used as a Collective warehouse. None of the transport participants returned. "

- Memorial for the German residents of the city and district of Stolp who perished between 1945 and 1947 at the Old Cemetery in Stolp, inaugurated 50 years after the expulsion.

Sports

The professional basketball team Czarni Słupsk is based in Słupsk and plays in the highest Polish league . The most important city football club is Gryf Słupsk . Until 1945 the German clubs SV Viktoria Stolp , SV Germania Stolp and SV Stern-Fortuna Stolp were based in the city.

politics

City President

At the head of the city administration is the city president . From 2014 to 2018 this was Robert Biedroń (then Twój Ruch ). He did not run for the regular election in October 2018 and instead supported the candidacy of Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka. The result was as follows:

- Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka (Electoral Committee Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka and Robert Biedroń) 53.2% of the vote

- Anna Mrowińska ( Prawo i Sprawiedliwość ) 22.6% of the vote

- Beata Chrzanowska ( Koalicja Obywatelska ) 17.5% of the vote

- Mirosław Betkowski (Election Committee “Slupsk Civic Association”) 4.7% of the vote

- Rafal Kobus ( Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej / Lewica Razem ) 2.0% of the vote

Danilecka-Wojewódzka was elected as the new mayor in the first ballot.

City council

The city council has 23 members who are directly elected. The election in October 2018 led to the following result:

- Election committee Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka and Robert Biedroń 34.1% of the vote, 9 seats

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) 26.4% of the vote, 7 seats

- Koalicja Obywatelska (KO) 25.7% of the vote, 7 seats

- Election Committee "Slupsk Citizens' Association" 7.8% of the vote, no seat

- Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej (SLD) / Lewica Razem (Razem) 5.3% of the vote, no seat

- Remaining 0.8% of the votes, no seat

Town twinning

- Arkhangelsk , Russia, since June 29, 1989

- Bari , Italy, since July 22, 1989

- Bukhara , Uzbekistan, since April 8, 1994

- Carlisle , UK, since April 3, 1987

- Cartaxo , Portugal, since September 25, 2007

- Flensburg , Germany, since June 1, 1988

- Fredrikstad , Norway, since October 11, 2012

- Hrodna , Belarus, since July 30, 2010

- Ustka , Poland, since July 13, 2007

- Vantaa , Finland, since June 8, 1987

- Vordingborg , Denmark, since May 13, 1994

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Carl Schrader Sr. , Bookseller and city council, ensured the creation of green spaces

- Ignacy Jeż (1914–2007), Polish Roman Catholic theologian, Bishop of Köslin

- Isabel Sellheim (1929–2018), German homeland researcher

- Tadeusz Werno (* 1931), Polish Roman Catholic theologian, auxiliary bishop in Kolberg

sons and daughters of the town

- Siegfried Bock († 1446), German Roman Catholic theologian, Bishop of Cammin, Chancellor of King Erichs of Denmark, Norway and Sweden

- Henning Iven († 1468), German Roman Catholic theologian, Bishop of Cammin

- Johannes Block (between 1470 and 1480–1544), German Protestant preacher

- Bartholomäus Suawe (1494–1566), German Protestant theologian and bishop, reformer

- Petrus Suawe (1496–1552), Danish diplomat

- David Crolle († 1604), German Protestant theologian, superintendent in Stolp

- Michael Brüggemann (1583–1654), German Protestant theologian, court preacher to Princess Anna von Croy in Schmolsin

- Matthias Palbitzki (1623–1677), Swedish diplomat

- Michael Watson (1623–1665), German polyhistorian and university professor

- Andreas Stech (1635–1697), German baroque painter

- Daniel Friedrich Hindersin (1704–1780), Mayor of Königsberg

- Alexander Dietrich von Puttkamer (1712–1771), district administrator of the Stolp district

- Samuel Mursinna (1717–1795), German Protestant Reformed theologian

- Daniel Heinrich Hering (1722–1807), German Reformed theologian

- Thomas Heinrich Gadebusch (1736–1804), German constitutional lawyer and historian

- Christian Ludwig Mursinna (1744–1823), German military doctor

- Konrad Gottlieb Ribbeck (1759–1826), German Protestant theologian, since 1779 teacher at the Prussian Cadet Institute in Stolp

- Johann von Massow (1761–1805), Prussian district administrator for the Rummelsburg district

- Johann Friedrich Heller (1786–1849), German Baltic Evangelical clergyman, provost of the Werroschen Sprengels in Livonia

- Hans von Sydow (1790-1853), Prussian major general and commander of the Guard Cuirassier Regiment

- Ferdinand von Doering (1792–1877), Prussian major general and head of the clothing department in the War Ministry

- Eduard von Bonin (1793–1865), Prussian general and minister of war

- Hermann Waldow (1800–1885), German pharmacist, natural scientist and poet

- Konstantin von Puttkamer (1807–1899), Prussian major general, most recently in command of the 35th Infantry Regiment

- Theodor von Kleist (1815–1886), Prussian manor owner and politician, MdH

- Karl von Zglinitzki (1815–1883), Prussian lieutenant general, most recently commander of the 4th Infantry Brigade

- Hermann von Bychelberg (1823–1908), Prussian artillery general, most recently inspector of the 3rd field artillery inspection

- Ewald Christian Leopold von Kleist (1824–1910), Prussian general of the infantry, most recently commanding general of the 1st Army Corps

- Otto Helm (1826–1902), German researcher

- Otto von Kameke (1826–1899), German painter, member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts

- Heinrich von Stephan (1831–1897), General Postal Director of the German Empire

- Berthold Suhle (1837–1904), German classical philologist and chess player

- Gustav von Glasenapp (1840–1892), Prussian officer and military writer

- Ewald Fritsch (1841–1897), co-founder of the large purchasing association of German consumer associations (GEG)

- Albert Fauck (1842–1919), German old master of deep drilling technology

- Wilhelm Dames (1843–1898), German paleontologist and geologist, university professor in Berlin

- Edmund Waldow (1844–1921), German architect

- Hanno von Dassel (1850–1918), German general

- Eduard Engel (1851–1938), German linguist and literary scholar

- Gustav Kauffmann (1854–1902), member of the Reichstag and mayor of Berlin

- Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929), German general and marshal of the Ottoman Empire

- Georg von der Marwitz (1856–1929), German general, commander of the 2nd Army in World War I

- Paul Geisler (1856-1919), German composer

- Edmund Edel (1863–1934), German caricaturist, illustrator, writer and film director

- Wilhelm Heinrichsdorff (1864–1936), German painter and draftsman, high school and university teacher

- Hedwig Lachmann (1865–1918), German writer

- Paul Gerhard von Puttkamer (1866–1941), German officer and theater manager

- Hans Schrader (1869–1948), German classical archaeologist

- Paul Fuhrmann (politician) (1872–1942), German manor owner and member of the Reichstag

- Paul Ritter (1872–1954), German historian, employee of the Leibniz edition of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Gertrud Arnold (1873–1931), German actress

- Erwin Bumke (1874–1945), German lawyer, President of the Imperial Court

- Oswald Bumke (1877–1950), German psychiatrist and neurologist

- Otto Freundlich (1878–1943), German sculptor and painter

- Arthur Blaustein (1878–1942), German lawyer, economist and university lecturer

- Walter Lichel (1885–1969), German officer, most recently general of the infantry in World War II

- Hermann Wilke (1885–1954), German politician (SPD) and trade union official

- Albert Callam (1887–1956), German party functionary (KPD) and publishing director

- Max Jessner (1887–1978), German dermatologist

- Fritz Jessner (1889–1946), German-American theater director and director

- Wienand Kaasch (1890-1945), German politician (KPD)

- Charlotte Ollendorff (1894–1943), German ancient historian

- Kurt Tuchler (1894–1978), German judge and Zionist, emigrated to Tel Aviv in 1936

- Ernes Merck (1898–1927), German racing driver

- Kurt Behnke (1899–1964), German lawyer, representative of the Supreme Official Criminal Police Office at the Reichsdienststrafhof, later President of the Federal Disciplinary Court

- Eberhard Preußner (1899–1964), German music teacher

- Wilhelm Fließbach (1901–1971), German lawyer, mayor of the city of Sopot, later judge at the Federal Fiscal Court

- Jürgen Wegener (1901–1984), German painter

- Siegfried Gliewe (1902–1982), German writer, published articles on Pomeranian local history

- Harald Laeuen (1902–1980), German journalist and author

- Flockina von Platen (1903–1984), German actress

- Paul Mattick (1904–1981), German councilor communist and political writer

- Fritz Pleines (1906–1934), German SS man and concentration camp commandant, killed in the “Röhm Putsch”

- Werner Ventzki (1906–2004), German politician (NSDAP) and government official

- Helene Blum-Gliewe (1907–1992), stage designer and architectural painter

- Walter Schüler (1908–1992), German gallery owner

- Annemarie Korff (1909–1976), German actress

- Angelika Sievers (1912–2007), German geographer, professor at the Vechta University of Education

- Heinz Theuerjahr (1913–1991), German sculptor, painter and graphic artist

- Heinz Rennhack (1913 - ????), German soccer player

- Günter Glende (1918–2004), German politician (SED), head of the Department of Business Administration of the SED Central Committee

- Cordula Bölling-Moritz (1919–1995), German journalist and author

- Lothar Domröse (1920–2014), German officer

- Kurt Semprich (1920–1999), German politician (SPD)

- Gertrud Wehl (1920–2015), German Christian missionary

- Gertraut Last (1921–1992), German actress, head of the artistic management office of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin

- Johannes Hildisch (1922–2001), German engineer, architect and numismatist

- Rudi Tonn (1923–2004), German local politician (SPD), mayor of Hürth

- Hannes Kirk (1924-2010), German soccer player and soccer coach

- Heinz Radzikowski (* 1925), German former field hockey player

- Johannes Geiss (1926–2020), German physicist, co-director at the International Space Science Institute in Bern

- Roswitha Wisniewski (1926-2017), German literary scholar and politician (CDU)

- Dietrich Schwarzkopf (1927–2020), German journalist, media politician, university professor and author

- Heinrich Gemkow (1928–2017), German historian, Vice President of the Kulturbund of the GDR from 1968 to 1990.

- Wolf Gerlach (1928–2012), German film architect for advertising films, inventor of the Mainzelmännchen

- Hans-Georg Lietz (1928–1988), German writer

- Odo Marquard (1928–2015), German philosopher

- Christian Meier (* 1929), German historian

- Jürgen von Woyski (1929–2000), German sculptor and painter

- Barbara Koerppen (* 1930), German violinist

- Siegfried Mrotzek (1930–2000), German writer and translator

- Karl-Heinz Pagel (1930–1994), German local historian from the Stolp district

- Joachim Schwarz (1930–1998), German deacon, composer, cantor and church music director

- Edgar Wisniewski (1930–2007), German architect

- Wolf-Rüdiger von Bismarck (* 1931), German administrative lawyer, former district administrator of the Plön district

- Klaus von Woyski (1931–2017), German painter, graphic artist and restorer

- Friedrich de Boor (1933–2020), German church historian

- Eitelfriedrich Thom (1933–1993), German conductor and musicologist

- Wolfgang Rödelberger (1934–2010), German music producer, composer, musician and arranger

- Ilse Bastubbe (1935–2010), German actress, voice actress and assistant director

- Bazon Brock (* 1936), German professor for aesthetics and art education

- Carl de Boor (* 1937), German-American mathematician, professor of mathematics and computer science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Gerd Aberle (* 1938), German economist and transport scientist

- Wolfgang Schneider (1938–2003), German historian and weightlifter

- Wilhelm von Sternburg (* 1939), German journalist

- Harry Klugmann (* 1940), former German eventing rider

- Siegfried Loch (* 1940), German record manager

- Jörg Hennig (* 1941), German Germanist, professor for journalism at the University of Hamburg

- Hans-Günther Schramm (* 1941), German politician (Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen), former member of the Bavarian State Parliament

- Dieter Stöckmann (* 1941), German general, most recently Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe

- Jörg Schmeisser (1942–2012), German artist

- Peter-Christian Witt (* 1943), German historian

- Joachim Holtz (* 1943), German journalist and foreign correspondent

- Ulrich Beck (1944–2015), German sociologist

- Mirosław Justek (1948–1998), Polish football player

- Danuta Olejniczak (* 1952), Polish politician (PO) and member of the Sejm

- Grażyna Auguścik (* 1955), Polish singer

- Bogusława Olechnowicz (* 1962), judoka

- Przemysław Gosiewski (1964–2010), Polish politician (PiS) and victim of the plane crash near Smolensk

- Tomasz Iwan (* 1971), Polish former football player

- Monika Wolting (* 1972), Polish literary scholar and university professor

- Magdalena Adamowicz (* 1973), Polish university professor and European politician

- Paweł Kryszałowicz (* 1974), Polish national football player

- Milena Rosner (* 1980), Polish national volleyball player

- Kamila Augustyn (* 1982), Polish badminton player

- Marek Fis (* 1984), Polish comedian

- Sarsa (* 1989), Polish singer

- Marcelina Witek (* 1995), Polish javelin thrower

Other personalities

- Joachim von Podewils , Landvogt zu Stolp until 1530 and princely district administrator (father of Felix von Podewils on Demmin and Krangen)

- Erdmuthe von Brandenburg (1561–1623), lived as a widow at Stolper Castle since 1600 (second residence in Schmolsin Castle since 1608)

- Georg Daniel Coschwitz (pharmacist) (1644–1694), physician, rural physician of the Stolp, Schlawe and Rummelsburg districts and personal physician to the Duke of Croy

- Johann Heinrich Sprögel (1644–1722), German Evangelical Lutheran clergyman, was provost and pastor at St. Marien Church in Stolp from 1705

- Barthold Holtzfus (1659–1717), philosopher and Protestant theologian, was court preacher in Stolp from 1686–1696

- Ernst Bogislav von Kameke (1674–1726), civil servant, became governor of Stolp and Schmolsin in 1707

- Georg Daniel Coschwitz jun. (1679–1729), medic and pharmacist, was educated in Stolp

- Christian Schiffert (1689–1765), Schulmann, was vice rector from 1717 and rector from 1722 at the Latin School of Stolp

- Franz Albert Schultz (1692–1763), Protestant theologian, was provost in Stolp from 1729–1731

- Johann von Buddenbrock (1707–1781), military, under his direction the Prussian Cadet Institute of Stolp was established

- Wilhelm Sebastian von Belling (1719–1779), hussar general in the Stolp garrison, equestrian general of Frederick the Great

- Christian Wilhelm Haken (1723–1791), pastor at St. Mary's Church from 1771, wrote about the history of Pomerania

- Johann Cunde , Schulmann, attended the Latin school in Stolp in his early youth

- Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (* approx. 1764), teacher at the Stolper Kadettenanstalt, topographer and writer

- Karl Christian von Brockhausen (1767–1829), attended cadet school in Stolp, diplomat

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), Protestant theologian, officiated 1802–1804 as court preacher in Stolp

- Leopold Friedrich von Kleist (1780–1837), postmaster in Stolp from 1811, brother of Heinrich von Kleist

- Karl Friedrich von Steinmetz (1796–1877), military, was educated in the cadet schools of Kulm, Stolp and Berlin

- Reinhard Moritz Horstig (1814-1865), German philologist and grammar school teacher, worked in Stolp from 1847

- Theodor Kock (1820–1901), classical philologist, was the high school director in Stolp

- Adolf Brieger (1832–1912), educator and writer, 1860–1863 teacher at the Stolper Gymnasium

- Friedrich Gravenhorst (1835–1915), road construction technician, worked temporarily on property tax regulation in Köslin and Stolp

- Joseph Scheurenberg (1846–1914), painter, painted frescoes in Stolp's town hall

- Hans Hoffmann (1848–1909), writer, was a teacher at the Stolper Gymnasium

- Fritz Siemens (1849–1935), psychiatrist and university professor, died in Stolp

- August von Mackensen (1849–1945), Prussian field marshal, had been chief of cavalry regiment No. 5 of the Stolper garrison since 1936

- Carl Alexander Raida (1852–1923), composer, since 1874 theater music director in Stolp

- Max Gabriel (1861–1942), composer and conductor

- Ernst Baeker (1866–1944), German composer, lived in Stolp after the First World War

- Karl Dunkmann (1868–1932), Protestant theologian, sociologist, was pastor in Stolp from 1894–1905

- Edwin Renatus Hasenjaeger (1888–1972), Lord Mayor of Stolp from 1925 to 1933

- George Grosz (1893–1959), painter, graphic artist and writer, grew up in Stolp and Berlin

- Erich Weidner (1898–1973), 1928–1931 was the director and dramaturge at the city theaters of Stolp and Danzig

- Erich Mix (1898–1971), German politician (NSDAP, FDP), 2nd Mayor of Stolp from 1931 to 1933

- Richard Langeheine (1900–1995), lawyer, politician, was Lord Mayor of Stolp

- Robert Biedroń (* 1976), mayor of Słupsk since the election on November 30, 2014, civil rights activist and from 2011 to 2014 member of the Sejm

Rural commune of Slupsk

The rural community Słupsk, to which the city itself does not belong, covers an area of 260.58 km² and has 18,110 inhabitants (as of June 30, 2019).

Sources and older chronicles

- Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann (ed.): Detailed description of the current state of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Volume 2, Stettin 1784, pp. 899-930 ( full text ).

- Otto Borck, Rudolf Bonin : The hospitals of the city of Stolp: their development and administration 1311-1911 . 1911.

- Rudolf Bonin : History of the City of Stolp . Volume 1: Until the middle of the 16th century . 1910.

- Walther Bartholdy : O Stolpa, you are honorable ...: Cultural and historical contribution to the church and town history of Stolp. For the 600th anniversary of the city and the Marienkirche . 1910, OCLC 179137513 .

- Werner Reinhold : Chronicle of the city of Stolp. Stolp 1861 ( full text ).

- Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - outline of their history, mostly according to documents. Berlin 1865, pp. 413-433 ( full text ).

- Christian Wilhelm Haken : Three contributions to explain the history of the city of Stolp. newly published by FG Feige. Stolp 1866 ( full text ).

- Johann Ernst Benno : The city of Stolpe. Attempt to present a historical representation of their fates down to the most recent times. With a view of Stolpe. Verlag CG Hendeß, Köslin 1831.

- Johann Ernst Fabri : Geography for all classes . Part I, Volume 4, Leipzig 1793, pp. 591-598 ( full text ).

literature

- Karl Hilliger: 1848/49. Historical-political images from the province of Pomerania, especially from the city of Stolp and the district of Stolp . Stolp 1898.

- Our Pommerland , vol. 6, no. 5: Das Stolper Land , Stettin 1921.

- Walter Witt: Prehistory of the city and district of Stolp . Stolp iP 1931.

- Our Pommerland, vol. 18, vol. 1–2: Das Stolper Land , Stettin 1933.

- Karl-Heinz Pagel , Heimatkreis Stolp (Hrsg.): Stolp in Pomerania - an East German city. A book about our Pomeranian homeland . Lübeck 1977. (full text)

- Karl-Heinz Pagel : The district of Stolp in Pomerania: evidence of its German past . Lübeck 1989 ( (table of contents) full text ).

- Volker Stolle, Jan Wild: For example Stolp, Slupsk: Lutheran continuity in Pomerania across population and language changes . Oberursel 1998, ISBN 3-921613-36-1 .

- Lisaweta von Zitzewitz (ed.): Początki miasta Słupska: nowe wyniki badawcze z Niemiec iz Polski . Acad. Europ. Kulice-Külz, Nowogard 1999.

- Mariusz Wojciechowski, Beata Zgodzińska: Rok 1901. Słupsk przed stu laty . Muzeum Pomorza Srodkowego w Slupsku, Slupsk 2001, ISBN 83-915776-2-7 .

- Wioletta Knütel: Lost homeland as a literary province: Stolp and its Pomeranian surroundings in German literature after 1945 . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-39781-X .

- The museum's team of authors: Guide to the Central Pomeranian Museum in Stolp / Slupsk . Slupsk 2003, ISBN 83-89329-07-7 .

- Michael Rademacher: German Administrative History Province of Pomerania - City and District of Stolp . 2006.

- Gunthard Stübs, Pomeranian Research Association: The urban district of Stolp in the former province of Pomerania . (2011).

- Roderich Schmidt : The historical Pomerania. People - places - events . 2nd Edition. Böhlau, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20436-5 , pp. 139–149 ( restricted preview ).

Web links

- City website (Polish, German, English, French, Russian, Arabic, Chinese)

- City map of Stolp, drawn in 1947 (PDF; 45.6 MB)

- Website of the Stolper Heimatkreise (German)

- Digitized German daily newspapers from before 1945.

- MY.Slupsk (German, Polish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Werner Reinhold : Chronicle of the city of Stolp . Stolp 1861, p. 2 ( online ).

- ^ Christian Wilhelm Haken : From the maiden monastery. In: Three contributions to explain the city history of Stolp (newly published by FW Feige). Stolp 1866, p. 7 ( online ).

- ^ The Slavic place names in Meklenburg. In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology . Volume 46 (1881), p. 138.

- ↑ Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - An outline of their history mostly based on documents . Sendet, Vaduz 1996 (unchanged reprint of the 1865 edition), ISBN 3-253-02734-1 , pp. 413–493 ( online ).

- ↑ Leszek I, Duke of Cracow, was the last senior duke of Poland to claim sovereignty over all Polish duchies, including the Duchy of Pomerania of the Samborids.

- ↑ James Minahan: One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, ISBN 0-313-30984-1 , p. 375.

- ^ Oskar Eggert: History of Pomerania . Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-980003-6 , p. 107.

- ^ Likewise, the Brandenburg margraves had acquired entitlement rights for the Lande Schlawe-Stolp from Duke Mestwin II in the contract at the Dragebrücke in 1273.

- ^ Witch trials in Pomerania. Hard winter of 1709. Fragment. In: J. Ph. A. Hahn, G. F. Pauli (Ed.): Pomeranian Archive of Science and Good Taste. Second volume. Stettin / Anklam 1784, pp. 117-121 ( online ).

- ^ Witch trials in Pomerania. Hard winter of 1709. Fragment. In: J. Ph. A. Hahn, G. F. Pauli (Ed.): Pomeranian Archive of Science and Good Taste. Second volume, Stettin / Anklam 1784, pp. 117–121, especially pp. 122–123 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Christian Friedrich Wutstrack : Short historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal Prussian duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1793, pp. 691-692.

- ↑ a b c d Handbook of Historic Places in Germany . Volume 12: Mecklenburg - Pomerania. Kröner, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 289-290.

- ^ Gottfried Traugott Gallus: History of the Mark Brandenburg for friends of historical information . Volume 6. Züllich / Freistadt 1805, p. 274.

- ^ New German general library . Volume 23. Kiel 1796, p. 499.

- ^ Addendum to the brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal Prussian duchy of Vor and Hinter Pomerania . Stettin 1795, p. 253.

- ↑ On the reorganization of the cadet system after the Peace of Tilsit see Curt Jany : History of the Prussian Army from the 15th Century to the Year 1914. Volume 4: The Royal Prussian Army and the German Reichsheer 1807-1914. 2nd, supplementary edition. Edited by Eberhard Jany. Biblio, Osnabrück 1967, ISBN 3-7648-1475-6 , p. 38.

- ^ E. Wendt & Co. (Ed.): Overview of the Prussian Merchant Navy . Stettin January 1848, p. 23 ( online [accessed June 4, 2015]).

- ↑ L. Wiese (ed.): The higher school system in Prussia - historical-statistical representation. Wiegandt and Grieben, Berlin 1864, p. 153 and p. 709 ( online ).

- ↑ NH Schilling : Statistical reports about the gas companies in Germany, Switzerland and some gas companies in other countries. 2nd, greatly increased edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1868, p. 323.

- ↑ a b c Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 19, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, p. 60.

- ↑ a b Gunthard Stübs and Pomeranian Research Association: The town of Stolp in the former town of Stolp in Pomerania (2011).

- ^ Leopold von Zedlitz-Neukirch : New Prussian Adelslexikon . First volume: A – D. Leipzig 1836, p. 56.

- ↑ Christian Wilhelm Haken : Three contributions to explain the city history of Stolp. newly published by FG Feige. Stolp 1866, pp. 7-17.

- ^ Słupsk in Poland is the winner of the 2014 Europe Prize. In: Website of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe . April 10, 2014, archived from the original on June 23, 2014 ; accessed on June 23, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Kratz (1865), p. 430.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Michael Rademacher: German administrative history Pomerania - Stolp district (1906)

- ↑ The family of the Pomeranian dukes, which had died out completely with the death of Bogislaw XIV , had in the end always suffered from problems of recruiting. The blame for the lack of heirs to the throne was often blamed on alleged 'witches' who allegedly were up to mischief at the court in the immediate vicinity of the duke couple concerned.

- ^ The Pomeranian Newspaper. No. 34/2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Result on the website of the election commission, accessed on August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Result on the website of the election commission, accessed on August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Meta Lublow: stumbling bookstores, a piece of local history. In: Pomerania. Journal of Culture and History. Issue 2/2013, ISSN 0032-4167 , pp. 38-41.

- ^ Archive for the history and archeology of Upper Franconia (EC von Hagen, ed.). Volume 9, second issue, Bayreuth 1864, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ spiegel.de December 1, 2014: Revolution in Poland's provinces: gay man conquers town hall of Slupsk