Goetheanum

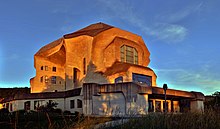

The Goetheanum is a building in Dornach in the canton of Solothurn , around ten kilometers south of Basel . It serves as the seat and conference venue of the General Anthroposophical Society and the School of Spiritual Science as well as a festival hall and theater building . It is named after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . After the previous building, also known as the Goetheanum, was destroyed by arson on New Year's Eve 1922/23, the building that exists today was built on the same site between 1925 and 1928. Both designs come from Rudolf Steiner , the founder of anthroposophy . What is striking about the monumental exposed concrete building with its wide-spanned roof is the extensive lack of right angles. The monolithic - organic building, stylistically often attributed to Expressionism , appears sculpturally formed and, according to Steiner's idea, should express "the essence of organic design". Together with other stylistically similar buildings in the vicinity, the Goetheanum , which has been a listed building since 1993, forms an ensemble that is one of the cultural assets of national importance in the canton of Solothurn . As a basic structural model, the Goetheanum has also given impulses for the entire anthroposophical architecture , which for example includes the buildings of many Waldorf schools .

history

Location search of a community location

In 1902, Rudolf Steiner was elected General Secretary of the German section of the Theosophical Society in Berlin , from which the anthroposophical movement later emerged. The Federation of European Sections of the Theosophical Society held an annual international congress. In 1907 Steiner succeeded in organizing this international congress on German soil for the first time. For this, spaces were required that were suitable both for discussing ideological questions and for artistic performances. In that year he began his architectural work by temporarily redesigning the rented rooms of the Tonhalle in Munich for this event, which has gone down in anthroposophical history as the Munich Congress . The artistic interior decoration of the hall consisted of seven high boards with columns painted on them, as well as tondi , which alternated with the seven apocalyptic seals. The plastic design of the capitals represented certain planetary development states of the earth, which should differ depending on the spiritual perception. The design of the rented hall already indicated that the artistic intention was to create a real building.

Munich developed into the most important meeting place for the members of the German section of the society. Their events mostly took place in rented theater and congress rooms. After first gaining experience with the rehearsal of plays by Édouard Schuré , Steiner himself began to try his hand at writing and directing spoken theater . In 1910 he created The Gate of Inauguration , a mystery drama that was heavily based on Goethe's fairy tale of the green snake and the beautiful lily. The rehearsal took place together with professional and amateur actors in a kind of summer retreat . In the years that followed, up to 1913, the project grew into a tetralogy with a performance of around seven hours each. With the growing number of members, the desire arose to have separate rooms for intellectual work and artistic creation all year round. Steiner himself feared that without a permanent community space the current he was promoting would perish again, and in 1912 he was instrumental in securing the separation from the Theosophical Society. His goal was a European-Christian movement, which from then on called itself anthroposophy .

By Steiner's design of the Munich Tonhalle, the supporter Ernst August Karl Stockmeyer felt inspired to deal with the art and architecture ideas. Stockmeyer painted and modeled a domed room with columns in Malsch near Karlsruhe , which only had a single opening in the main dome. The opening was designed in such a way that at the beginning of spring around 9 a.m., sunlight would fall on a certain point inside. Stockmeyer showed Steiner his design in the spring of 1908. Steiner was fundamentally very interested in the planning for the so-called Malsche model . However, a monumental building without a suitable stage and auditorium did not seem suitable to him. In addition, the location in a secluded wooded area that Stockmeyer had chosen for it was difficult to access in terms of traffic. The occult building was realized as an accessible model; However, after laying the foundation stone on the night of April 5 to 6, 1909, Steiner never returned to the site and the project was quickly forgotten. Nevertheless, it is regarded as a model for Steiner's setting of the "Sun Temple" in his first two mystery dramas. The building, which had been abandoned for many years, was recognized as a cultural monument by Baden-Württemberg in 1976 . Since then, an association has taken care of the maintenance and care of the building.

Johannesbau project in Munich

On Steiner's initiative, the architect Carl Schmid-Curtius (1884–1931) was commissioned to draw up designs for a property in Munich- Schwabing . The building project envisaged a double-domed building and was named Johannesbau after the main character Johannes Thomasius from Rudolf Steiner's Mystery Dramas. Steiner's involvement in the plans was limited to the design of the stage and minor detailed work. However, the plan for this construction met with considerable resistance from the city authorities, the neighboring church and local residents, and negotiations for the realization of the construction project proved to be protracted.

In the fall of 1912, Steiner met the dentist Emil Grosheintz (1867-1946), an active, wealthy member who had already attended the Munich Congress, during a series of lectures in Basel. Grosheintz invited Steiner to his country estate in Dornach, the Brodbeck house. Since Steiner had doubts about reaching an agreement for the building project in Munich, he was interested in the neighboring and barely built-up, slightly hilly area in the Birstal. Grosheintz offered him the property and Steiner visited it in March 1913 together with an architect. The site seemed suitable for structural and formal reasons - at that time the canton of Solothurn had no building law at all - so that after the Munich experience, nothing was risked in this regard. Steiner liked the anthroposophical milieu in the nearby city of Basel, as did the landscape atmosphere in the neighboring Hermitage in Arlesheim , where part of the legend of St. Odile might have taken place. The fact that the Battle of Dornach took place on July 22nd, 1499 on the hill that was selected for the construction of the new center and its surroundings , in which Switzerland emancipated itself from the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , was not seen as an obstacle. Due to the historical background, the location is sometimes referred to as "Blood Hill".

Schmid-Curtius had to keep reworking the original plans for the Johannesbau in Munich in order to meet the requirements that were made out of consideration for the surrounding buildings. That is why Steiner increasingly considered a building in Dornach to be more suitable, especially since the planned building would be more effective on the undeveloped hill. The plan for the Johannesbau in Munich was finally rejected on January 12, 1913 by the Minister of State for the Interior Maximilian von Soden-Fraunhofen in Munich on the grounds of "aesthetic points of view", against which an appeal was lodged. Steiner was then given the opportunity to obtain building land in the neighborhood of Stift Neuburg near Heidelberg - Alexander von Bernus wanted to give it to him - but the planning and preparations for the purchase of the property had already been geared towards Dornach in advance, so Steiner accepted his friend's offer on Declined September 19, 1913. The decision to build in Switzerland was actually made in June 1913, and the foundation stone was laid on September 20 of the same year. A few days after the foundation stone was laid, on October 6, 1913, the rejection of their objection to the original decision of the State Ministry, which had meanwhile become meaningless for the anthroposophists, was received.

First Goetheanum

The solemn laying of the foundation stone on September 20, 1913 (for the ceremony, see also here ) aroused both curiosity and fears among the 2100 inhabitants of the community at the time. The pastor Max Kully from neighboring Arlesheim, in particular, saw Steiner's teachings as a “serious error” and tried to prevent construction by petitioning the Solothurn government two days after the foundation stone was laid. Thereupon the government asked the anthroposophical society to give it insight into its teachings. In response, she received an extensive collection of literature, which she passed on to the episcopal chancellery for review. Since she couldn't do anything with it, Kully's objection was ineffective. The anthroposophists tried to calm the heated mood by declaring in the local newspapers and stated that as "residents of the small villa colony they will live very quietly on their property".

The drafts for the Johannesbau in Munich were used as the planning basis for the first Goetheanum. The idea of a double dome building with two interlocking dome segments was already included in this project: two domes of different sizes , which rest on two rotundas of different sizes , penetrate one another. The large dome over the auditorium was 18 meters above the stage, which was covered by the small dome, and the highest point of the dome was 27.2 meters above the ground. The domes in the auditorium and the stage were supported by wooden pillars with a pentagonal cross-section made of different types of wood. The ratio between the small and large dome was 3: 4. The radius of the small circle was 12.40 meters, that of the large one 17 meters. The radius of the column circle in the stage area was 9.40 meters, in the audience area 13 meters. Both domes were covered on the outside with blue-green-silver Norwegian slate from Voss . The stage section on the ground floor was surrounded by a semicircular part for the backdrop and the adjoining cloakrooms, which were arranged in the manner of a transept. At Steiner's request, the base structure was cast in concrete, as this enables a special shape and allows the structure to adapt to the surrounding Jura mountain range. The concrete basement was completed in February 1914, so that the wooden scaffolding for the superstructure could begin.

The superstructure on a concrete base with Art Nouveau elements was also made entirely of wood. The principle of metamorphosis should represent the supporting element of the entire building concept. The forms of the capitals developed continuously from the previous one. The same was true of the architraves connecting the columns . The ceiling paintings of the two domes were done with vegetable colors throughout. Steiner developed a special glass grinding technique for the motifs of the windows.

It was intended not only to liven up the form as it was expressed in Art Nouveau , but also to create an organic-plastic building that was to become the formative element of the architecture. In the interplay of the arts (painting, sculpture, architecture) in the interior design, an important element of Art Nouveau was achieved for the first time: "The integrated total work of art: a uniform building idea had included all the arts." This realized another ideal of modern art, the idea the work community: specialists, artists and untrained assistants from 17 countries worked together to create the joint building. This ideal was so strong among those involved that even during World War I, members of hostile nations worked together. Construction work continued even during the war. The interior decoration was commissioned by the German oriental painter Hermann Linde , who was one of the founders of the Johannesbau-Verein.

Steiner emphasized that the location in Dornach has a special fatefulness: “The fact that the building is not listed here [Munich] is not our fault, it is our karma . It is our fate that it is performed in a lonely place, but in a place which, given its local location, has an importance for the spiritual life of modern times. ”His followers had no choice but to go to Dornach to follow if they wanted to be close to the spiritual center. Therefore, the building was followed by the settlement of many anthroposophists who built houses for themselves on the Dornach hill (→ buildings in the area ). The influx of people doubled the population of the municipality within a few decades. Since he partially disagreed with the appearance of the newly built houses, he appealed on January 23, 1914, that they should be designed in such a way that you can tell that they belong to the “big picture”. The emergence of the settlement in Dornach is part of the movement that began at the end of the 19th century, which gave rise to a number of life-reforming artist colonies such as Monte Verità in Ticino .

In the first quarter of 1914 up to 600 workers were busy with the construction work on the construction site, and the topping-out ceremony could already be celebrated on April 1 of the same year . By 1917, over 3.6 million Swiss francs flowed into the Johannesbau; the value of the land was put at CHF 218,000. However, the financial situation deteriorated from the beginning of the First World War, so that the work stagnated.

It was not until 1918 that the name Goetheanum prevailed over Johannesbau . Steiner adored Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who, in addition to his poetry, which partly relied on esoteric aspects, also produced scientific works , including his theory of colors (→ Goetheanism ). Goethe used his doctrine of metamorphosis and the discovery of the " primordial plant " to explore the spiritual and spiritual worlds. Steiner found starting points for his efforts to gain knowledge in Goethe's work. With the renaming one wanted to remove the ground from speculation about the meaning of the name John and the association to John the Baptist or the Evangelist John . In addition, naming it after a recognized poet and writer seemed more appropriate, as the anthroposophists at that time were still fighting hard for recognition in society. The building was finally opened under the name Goetheanum on September 26, 1920.

Fire in the Goetheanum

On the night of January 1, 1923, the building, insured for 3,183,000 Swiss francs , was probably completely destroyed by arson ; all that was left was the concrete base.

According to investigations, the fire must have started as a smoldering fire between the walls so that it could spread slowly and unnoticed. The arsonist (s) were never identified. Since the members of the anthroposophical movement were repeatedly attacked and molested, one thesis suggests that the fire was started by those people who were hostile to the anthroposophists. Steiner commented on this as follows:

“Just now and then, after the terrible fire accident, it came to light again what adventurous ideas in the world are linked to everything that was meant by this Goetheanum in Dornach and what was supposed to be carried out in it. There is talk of the most terrible superstition that is supposed to be spread there. "

A suspicion was directed against the clockmaker and anthropologist Jakob Ott from Arlesheim. This was missing in the days after the fire. On January 10th, bone fragments were found on the site of the fire, which with a certain degree of probability are assigned to his person. According to a report published in 2007, Ott is said to have had an accident as a helper during the extinguishing work.

The writer and satirist Kurt Tucholsky wrote on the occasion of a lecture by Steiner in Paris in 1924:

“They set fire to his“ Steinereanum ”in Switzerland, an act that is thoroughly repugnant. It is said to have been a noble, domed building that looked like it was made of stone. But it was made of wood and plaster, like the whole teaching. "

Reconstruction plans

Just three months after the fire, in March 1923, Steiner published his plans for reconstruction in the weekly newspaper Das Goetheanum . His idea was not only to offer space for artistic and scientific work, but also to create space for the administration of society. The new building should be significantly larger, including the floor height. In a speech on June 17th of the same year, he spoke out against rebuilding the building in its old form. At this point it remained open how the construction project should be implemented. Although the sum insured was available after the claim , there were moral concerns among anthroposophists about using this “foreign capital” for it.

On December 31, 1923, the anniversary of the fire disaster, Steiner specified his construction plans. He stated that the new building should be less round, but rather a "partially round building, partially angular building" and completely made of concrete. The upper floor was intended for the large hall with a stage, the middle floor for scientific and artistic work, on the ground floor space was provided for the rehearsal stage, which will later be replaced by the so-called Grundsteinsaal. At that time, Steiner estimated construction costs of 3 to 3.5 million francs. It was already clear to him at the time that his project was breaking new ground. In his New Year's Eve lecture he said:

"If the Goetheanum is to come into being as a concrete building, it must emerge from an original thought, and everything that has been done in concrete building up to now is actually not a basis for what is to be built here."

At the end of March 1924, Steiner made a 1: 100 scale model of the new building from red-brown modeling clay from England ( Harbutt's Plasticine ). The model stood on a six-centimeter-high block of wood, which was intended to approximate the substructure and roughly corresponded to the floor plan of the double-domed building. The more precise design for the plinth substructure was not made until autumn 1924. With the completion of the model, several architects under the direction of Ernst Aisenpreis began to work out the plans so that the building request could be submitted to the government of the Canton of Solothurn. The ten plans and the application were submitted on May 20, 1924. After examining the application, the government council granted the building permit on September 9, 1924, but imposed conditions that still had to be taken into account. The first structural condition related to fire safety in the stage area and the installation of an extinguishing system. The second edition was issued with regard to the color design of the facade and the roof surfaces: They should be adapted to the site according to the ideas of the council. The government council said in the minutes:

“[...] As far as the construction forms of the project are concerned, it must be stated that they cannot be compared with the traditional construction forms in our country, because the building in its external form does not adapt to any architectural style. The question arises as follows: How will the building relate to the surrounding villages and the landscape? We note that due to the significant distance from Dornach and Arlesheim, the building and the anthroposophical houses that already exist in the vicinity, which are built with a similar character to the projected temple, are to be regarded as an isolated assembly. Numerous groups of trees complete the whole settlement after Dornach. The details of the building only come into view in the vicinity, so that the group of buildings in the surrounding villages is not impaired in the sense of the local community.

Viewed from a greater distance, the building will only present itself as a silhouette, and in our opinion this will be less intrusive than was the case with the earlier dome construction. The building will adapt to the terrain all the better if the correct color accentuation of the roof surfaces (slate covering) and the facade is ensured.

However, the building will never appear to be down-to-earth and only the future will tell whether one can come to terms with these types of construction. "

After the changes required by the authorities had been incorporated, a second planning application was submitted on November 11, 1924, which was approved by the building department on December 1. In the event of a rejection, Steiner had envisaged the property of a castle near Winterthur . The original plan provided for the remaining concrete base of the previous building to be integrated into the new building. The sketches of the first building application accordingly show the Goetheanum still with the old base. However, a closer examination of the terrace revealed that the stability of the significantly larger structure could not be guaranteed after the fire damage, so that a new base construction had to be created.

Second Goetheanum

At the beginning of 1925, the demolition of the old plinth began. Parts of the foundation next to the terrace were blown away. A short time later, on March 30, 1925, Rudolf Steiner died at the age of 64; he could no longer experience the completion of the second Goetheanum. To carry out the construction work, the Anthroposophical Society set up its own construction office in order to provide skilled workers, material and construction machinery on its own. The procedure thus deviated from the construction of the first Goetheanum, in which the Basel construction company was still involved as an entrepreneur, with which it was not entirely satisfied. Between 1925 and 1928, an average of 100 people were involved in the construction, including carpenters, joiners, iron benders, bricklayers and cement workers, foremen, concretes, electricians, mechanics and painters. The company received many letters, some of them from abroad, from people who wanted to participate in the construction; some of them were already involved in the first construction. The construction work was progressing well: the summer of 1926 began with the wooden cladding and steel reinforcement of the roof structure, which was accessible at the topping-out ceremony on September 29 of this year, Michaelmas Day . The collection of donations proved to be problematic. In addition to the around 3.1 million francs from building fire insurance, a further 1.5 million francs were needed to cover costs. In addition to circulars, slide lectures were held in many European cities from May 22 to November 9, 1927 to collect the funds.

On September 29, 1927, a wooden statue was moved to the eastern part of the still unfinished structure. The construction site received a lot of local and international attention and was visited by personalities from architecture and politics. In addition to Imai Kenji , who visited the building in 1926, Le Corbusier and the then Swiss Federal President Giuseppe Motta visited the Goetheanum construction site in 1927 . The population was also increasingly interested in the building. Thousands of interested parties asked whether they could be guided through the unfinished building. For this reason, a tour took place on July 1, 1928, in which over 1,000 people took part. The official opening was made on September 29, 1928.

With its huge dimensions, the concrete building of the second Goetheanum is a unique example of “organic architecture”. The three-dimensional exterior walls with their double-curved surfaces differ from earlier attempts to design the concrete wall freely, as with Antoni Gaudí . The function of the pillars is seen not only as a load-bearing, ambitious one, but also as one that goes from top to bottom and connects the building with the earth. The choice fell on the building material concrete because of the fire safety and probably also because the reconstruction with this building material was possible relatively quickly and inexpensively.

Interior construction and renovation

By 1929 the building, with a partial expansion inside, consumed 4,765,491 francs, by the end of 1934 it was around 5,188,000 francs. Because the majority of the donations flowed from Germany, construction work stalled during the Second World War , and further interior work could only be continued in the 1950s. The Great Hall remained unfinished until 1957 and was not finished until the beginning of the 21st century with its ceiling paintings, the new seating and the hotly debated columns, which were taken over from the first Goetheanum. Overall, the construction costs amounted to seven million Swiss francs, which corresponds to an inflation-adjusted value of around 98 million francs in 2005.

The Goetheanum was used as a half-finished shell for many years after it opened. The south staircase was completed in 1930, the corner stone hall with up to 450 seats was expanded in 1952 and renovated in 1989. The name of the hall is related to the location of the first cornerstone; no new foundation stone was laid for the second Goetheanum. The first expansion of the large hall took place between 1956 and 1957. It was not until 1996 to 1998 that the main hall received its current design. West entrance (1962–1964), north wing (1985–1989) and the English Hall with a capacity for 200 people (1969–1971) were not realized until decades after the opening in 1928.

At the time of construction, the long-term properties of concrete were not yet sufficiently known. Due to the sometimes very thin concrete layers of the load-bearing concrete framework - only six centimeters thick in places - and a water-cement ratio of more than 0.5, water gets into the reinforcement and starts rusting. The corroding steel expands and also blasts off small pieces of the exterior concrete, which causes double damage. The first relatively small-scale repair work on the facade was undertaken in the 1970s, for which the entire building had to be scaffolded. The terrace was renovated in the 1980s. During the renovation work at the beginning of the 1990s, the concrete had to be chipped off piece by piece, around five centimeters deep, and rusted off with a high-speed water jet at 1.5 times the speed of sound . A new layer of concrete could then be applied. The work on the monument was financed with donations and grants from the Canton of Solothurn. The stage technology was completely renewed in 2013-2014 for a total of 9 million francs.

description

location

The Dornach Hill, on which the Goetheanum stands, is formed by a mountain formation that geologically belongs to the Swiss Jura . The western end - called "Felsli" -, on which the Goetheanum stands, is a ledge consisting mainly of limestone . Parts of the hill had to be redesigned for the construction and the exact easting of the Goetheanum.

The area in Oberdornach is connected to the public transport network from Goethenaumstrasse. The walking paths around the Goetheanum are also available to the public. The Rüttiweg, the Albert Steffenweg and the Rudolf-Steinerweg open up the area. The prominent location underlines the size and monumentality of the building.

Architecture and construction technology

The Goetheanum with its base substructure extends 90.2 meters in an east-west direction and 85.4 meters in a north-south direction. The superstructure is 72 meters long, 64 meters wide and 37.2 meters high. With 110,000 cubic meters, of which 15,000 cubic meters are concrete, the enclosed space is almost twice as large as in the previous building with 66,000 cubic meters. The area taken up is 3,200 square meters, the surface of the base 3,300 and the building construction 5,500 square meters. The concave and convex shapes of the exposed concrete building are reminiscent of a monumental bunker - as the architecture critic Christoph Hackelsberger sees it - and its jagged shape unfolds a light-dependent aesthetic. The external dimensions and the exposed location at 370 m above sea level. M. located hills in the valley of the Birs make the Goetheanum visible far beyond the borders of the community.

The three-part main portal is located on the representative west facade - embedded in the supporting base construction. Above this, a sweeping terrace frames the Goetheanum all around. Two monumental glass surfaces rise above the base, the lower one is profiled like a spider web and has a two-winged door that allows access to the terrace from the inside. The window front above is divided into rectangular segments and beveled at the upper edge. The two window fronts form the west facade of the risalit-like , organically shaped building, which is the main architectural characteristic of the Goetheanum. The roof, covered with gray shingles, arches like the shell of a turtle as if protectively over the entire construction. On both sides of the west facade, two columns flank - so-called aerial roots (→ aerial roots ) - and protrude into the inner courtyard formed by the balcony. However, these do not have a structurally supporting function. Since the roof load is borne by the hall walls, the air roots are separated from the roof with expansion joints . The building is characterized by beveled corners and trapezoids , which can be found in different versions on many components, such as the trapezoidal pillar heads at the north and south entrances.

On the long sides, at the level of the concert hall, there are slender windows, while in the east-facing part, small windows with mostly changing polygonal outlines dominate. This design continues in the rather simple and less monumental-looking east facade. It is strictly symmetrical to the vertical line. There are parking spaces for Goetheanum staff on the east and north sides.

Due to the plastic modeled exterior of the Goetheanum with its many curved surfaces and sharp ridges, the finely divided formwork effort was extremely high. The work carried out by the carpenter Heinrich Liedvogel (1904–1977) was characterized by the fact that thin strips had to be bent when wet in order to nail them over frames . This created the necessary forms that could later be poured with concrete. The conception of the structure from the inside to the outside can be read from the irregularly shaped windows out of the wall. The statics and calculation of the concrete work were carried out by the Basel engineering office Leuprecht & Ebbell. A total of around 15,000 cubic meters of concrete and 990 tons of round steel were used for reinforcement . Due to the size and the new method at the time of construction, the Goetheanum is playing a pioneering role in the history of concrete construction. Before that, comparable concrete rib structures were only realized in the Centennial Hall in Wroclaw (1911–1913) and the airship halls of Orly (1922–1924).

As an engineer, Ole-Falk Ebbell-Staehelin played a key role in the construction of the second Goetheanum. He was already responsible for the construction of the concrete base for the first Goetheanum, the boiler house and the Duldeck house. His work for the second Goetheanum is one of the pioneering achievements of engineering in the early days of concrete construction - at the beginning of the construction project, he is said to have even doubted its feasibility. In 1952 he was also involved in the calculation of the reinforced concrete girders in the course of the renovation work for the foundation stone hall.

Interior design and equipment

Ground floor and west wing

The Goetheanum is essentially divided into two functionally different areas. The internal east part houses the stage and the associated rooms, the west, north and south wings are open to the public. On the ground floor, in the south and west areas, there are reception, information, conference office and cafeteria in the foyer, as well as cloakroom, a bookstore, postcard sales and some offices. The ground floor also houses the corner stone hall, the terrace hall and the English hall. The interior design of the rooms partly cites the outer forms, in particular the bevelled corners can be found on doors, frames , lampshades, cladding and even the green emergency lights to mark the emergency exits . In relation to the size of the building, there are comparatively few works of art such as statues, sculptures, busts or pictures in the corridors and walls of the Goetheanum. The largest sculpture is the representative of humanity .

The Grundsteinsaal, originally conceived as a rehearsal stage without auditoriums for the big stage, has had space for 450 visitors since 1952 and is used for lectures, celebrations as well as theater and eurythmy performances. The comparatively low room still has all the technical facilities that are necessary for a theater. During the renovation from 1989 to 1991, the room was decorated with large areas of wall paintings based on sketches by Rudolf Steiner.

The English Hall, designed by the architect Rex Raab , was expanded between 1969 and 1971 and also adorned with wall paintings and serves as a lecture and lecture hall. The naming of the hall is a reminder that members and sponsors from England in particular made the expansion possible with their donations. The simple terrace room is used for group work and is also used as a space for changing exhibitions.

In the west facade is the representative main portal, which is formed by three mighty double-wing doors in the base building. From there you can get to the cloakrooms in the great hall and the foyer . This entrance leads to the massive west staircase, which is formed by a generous and wide double spiral staircase. On the first floor, a glass front crossed by iron struts leads to the west with double-leaf glass doors to the base substructure used as a terrace . To the east, a corridor leads to the administration wing of the Goetheanum. The interior of the unpainted and unpainted west staircase, which largely follows the structural forms in the form of flat swinging flying buttresses and thus makes many internal details of the construction visible, was designed by Rex Raab and Arne Klingborg .

Stained glass window

The further way up the stairs to the Great Hall leads to a red window in the form of a triptych - hardly recognizable from the outside . The theme of this window and the others in the Great Hall is the individual development of people, their striving for knowledge and further development. In the left window a man looks down from a mountain with his head bowed; his gaze out of fear, hatred, ridicule and doubt obscures the view of the grayish animals rising. The middle window shows a serious-looking face with lotus flowers framed by angels. The integration of this individual into the cosmos is represented by the zodiacal images of Leo, Taurus and the planet Saturn . In the lower part is a depiction of the Archangel Michael, who took courage in the fight with the dragon. Finally, in the right picture, the beings have gained a clear view of spiritual heights.

The other windows in this series are located in the auditorium of the Great Hall, arranged on both sides from the entrance to the stage in a sequence of colors green, blue, violet and pink. Since the windows within the Great Hall could not be designed as a triptych, as in the first Goetheanum, “the high windows are divided into three different motifs”.

The green windows represent the fight with evil. The snake, which pierces the earth with a piercing look, symbolizes the cool and sharp intelligence in the north window. In the south window, the evil is represented as a tempting angel, which, although offering people the prospect of knowledge and independence, turns them away from the spiritual world. In anthroposophy, these two forms of evil are called Ahriman and Lucifer .

The secrets of the room are revealed in the blue windows. The so-called "spiritual student" recognizes the connection between macro and microcosm . The south window shows the structure of the body, the representations in the north window deal with the connection between the human senses - represented by the sense of sight and touch - and the cosmos.

The violet windows show the path of soul and spirit (spiritual soul) and their development over time. According to Rudolf Steiner's understanding, they go through a long series of incarnations and thus acquire skills and life experience. In the south window the spiritual soul moves from the spiritual world into the earthly and is between death and new birth. Depicted as a Janus head , she simultaneously looks into the past and the future. A pair of parents is shown below the situation. In the north window, the spirit soul begins its state with death - represented by a corpse surrounded by its relatives. The winding path of life leads him backwards in several stations from the old man to the baby and from there to higher spheres. On this path man deals with the question of how he relates to Christ and God; indicated by the cross of Golgotha and the tablets of the law .

The theme of the pink windows is that dimension that pursues purely spiritual goals beyond space and time. The south window indicates in its representations the meditation of the spiritual being of the people. The north window poses the question of how man relates to Christ and how Christ deals with Lucifer and Ahriman.

The windows are by the Russian artist Assja Turgenieff , who already worked on the construction of the first Goetheanum. The manufacture of the windows dragged on for decades, so that they could not be inaugurated until Pentecost 1945. The thickness of the glass plates is around 17 millimeters. The colors of the ground discs were created by adding metals and metal salts. For example, the red window received additions of gold , the green window was colored by iron salts. The motifs were created with a water-cooled grinding head in order to avoid tension and cracks on the workpiece.

Great Hall

The large hall, which can seat almost 1,000 people, consists of a trapezoid opening towards the square stage . The diverging walls give the audience in the back tiers the impression of being very close to the stage thanks to their perspective effect. The shape of the square and trapezoid running into each other is a metamorphosis of the double dome of the first Goetheanum . For the design of the Great Hall, seven pillars were constructed on each side, the first and the seventh merging with the corners of the hall, which was also intended as a structural metamorphosis to the first Goetheanum. The seven columns and capitals with the architrave curved over them had already been designed there. Through the four glass windows on the north and south walls, the auditorium is illuminated in an immanent colored light during the day .

The flat, also trapezoidal ceiling is painted with scenic pictures using plant colors. The ceiling painting covers around 560 square meters and consists of a steel frame suspended from the ceiling, onto which a mixture of plaster of paris, lime and sand has been sprayed. The ceiling painting above the organ shows the creation process in deep blue tones, namely the Elohim work into the earth, symbolized by light beings. The further representation of eyes and ears belong to the created being. The picture continues with the Old Testament paradise scene, in which man has to resist the seduction of the snake. In addition, Greece and the Oedipus motif are shown. At the side edges in the middle part - facing the stage - on the left the Atlantis destroyed by a water catastrophe and on the right the Lemuria destroyed by fire ; these two fictional places play a role in Steiner's spiritual research. Towards the stage, Indian, Persian and Egyptian people are depicted as representatives of the first historically known high cultures. Above the stage in the east, scenes are depicted one above the other in the form of the letters IAO: God's anger and melancholy (I), the dance of the seven (A) and the circle of the twelve (O). This should be an invitation to unite the diverging forces of thinking, feeling and willing.

After the completion of the second Goetheanum, the shell of the hall was used for almost 30 years and only refurbished in the following decades. The first glass windows were installed in the 1930s and the organ in the early 1950s . The first interior work with simple shapes took place in 1957 under the direction of Johannes Schöpfer (1892–1961). Since the originally suspended asbestos ceiling was not only problematic because of the health hazard, but also was not an optimal solution acoustically or visually, an ideas competition for the redesign took place. However, the designs were controversial and did not lead to a definitive solution for decades. Only when the authorities in the 1980s demanded the dismantling of asbestos-containing components in closed rooms used by people for health reasons, the shell was hollowed out in 1989 and redesigned in the second half of the 1990s.

The problematic acoustics of the first hall building could not be satisfactorily solved by adding sound-absorbing parts to a hall of this size. In June 1994 the board of the Goetheanum decided to commission planning work for the renovation of the large hall. In an interim report in February 1995, it was shown that the acoustics could still not be satisfactorily solved and threatened to mess up the schedule. For this reason, acousticians traveled to the Goetheanum on March 6th to sound out the possibilities on site. They made the suggestion that the half-pillars should be detached from the outer wall and instead free-standing, non-load-bearing pillars should protrude about 2.5 to 3 meters into the room at the edge of the rows of seats. The acousticians' proposal had to be checked for its consequences for statics and costs and was finally approved for implementation on October 23, 1995 by the building authorities subject to conditions relating to fire safety. Construction began on August 12, 1996 with a ceremony in which Ulrich Oelssner as architect and Christian Hitsch as artistic director took part. The demolition and dismantling of the inventory began. The removed glass windows were temporarily stored in the cellar. On November 25th, the asbestos removal work was completed and the demolition had progressed so far that one could see the roof beams from the hall. In December, work on the pillars and architraves began in parallel, and the demolition work was completely completed by the end of the month. In January 1997, the reinforcement scaffolding was installed in the south wall, which was later filled with shotcrete . The north wall and the ceiling, which were later to be hewn for the final shape, were also built according to the same principle. To make it easier to design with the concrete, pumice and limestone were added instead of the usual river gravel. For the reddish hue, iron oxide powder was added as an inorganic pigment.

On February 14, 1997 the concreted organ gallery was completed. The ceiling construction suspended from the roof structure was filled with 35 tons of gypsum-lime plaster on July 23, 1997, and the painting of the ceiling could begin on October 16. At the beginning of 1998 the glass windows were reinstalled and the hall was ready to go back to operation on April 3rd. The construction costs for the renovation of the hall came to around 25 million francs and were largely financed by donations.

The hall construction, which was completed in 1998, earned praise for the removal of asbestos, the improvement of the light, the chairs and the acoustics and the installed conference technology. The builders were also confronted, and to this day, with strong criticism from the international membership and the public, who consider the artistic design to be a mistake. According to this "retro accusation", the first Goetheanum was built into the second in a mannerist manner, thus taking a step backwards, instead of continuing Steiner's great artistic disenchantment from the first to the second building inside the hall.

stage

The large hall houses an almost cubic stage space behind the stage curtain. It measures 23 meters wide, 21.4 meters high to the Schnürboden and 19.4 meters deep. It is said to have been the largest stage in Europe until the 1960s. On both sides of the main stage, separated by wide gates, there are smaller side stages in the north and south wing, which are used for the preparation of scenery and props. The stage portal has a height of 8.5 meters, so that the upper stage measures 12.9 meters. It can accommodate curtains, veils, decorations and variable stage sets . The stage floor has sliding parts that can be raised or lowered as needed. The stage machinery also includes mechanical noise machines mounted on the walls. For example, the sound of rain is made by a rotating drum with gravel and the sound of thunder by a steel ball falling into a wooden canal. The basic design of the stage goes back to the year of construction in 1928; 2013 to 2014 the stage technology was overhauled and modernized after 85 years of operation. The lighting system on the Goetheanum stage is designed to bathe the entire stage area in flood light, as is usual for eurythmy ; This art of movement is less about punctual light accents from spots and chasers than about a large-scale color design that encompasses the entire stage space. The system, which is mounted on a lighting bridge in the ceiling on both sides of the central luminaire and in the side pillars, is able to create a wide range of color effects as well as to make the light in the edge area very differentiated. The control booth for the lighting technology is on the left, the sound technology is symmetrically on the right behind the spectator stands.

organ

The organ in the Great Hall was built in 1957 by Orgelbau Kuhn from Männedorf with 28 registers . The instrument stands on a gallery made of shotcrete above the entrance portal opposite the stage. The prospectus , built using elm wood, was created in 1998 and adapts to the architectural style of the Goetheanum.

With the redesign of the large hall, it was necessary to adapt the organ according to Steiner's specifications. Therefore, the instrument was reinstalled in 2000 and completely revised in 2004 by the Saalfeld organ building company Rösel & Hercher , equipped with a new console and new action, and adapted to the sensitive room acoustics and re-voiced.

The organ today has 30 sounding stops on two manuals and one pedal and works with slider chests . Both the register and the game mechanisms are electric.

In terms of sound, the instrument has two special features, taking up Steiner's comments on the music. On the one hand, the pitch is C = 128 Hz, which corresponds to a 1 = 432 Hz. On the other hand, a special, music-philosophically inspired mood was created , which was developed by the anthroposophist Maria Renold (1917–2003) and which dispenses with the usual tempering in favor of many perfect fifths (twelve-fifths scale).

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Annotation:

- R = register supplemented by Rösel

South and north wings

The south entrance is used most frequently in daily operations. Similar to the west staircase, the design principle of the outside continues inside. It is noticeable that a handrail profile is incorporated into the railing, which corresponds to the grip of the human hand. The stairwell in the south wing and the associated vestibule were completed in 1930. Further expansions were carried out in 1951 and 1993. In 1981, a conference room was built in this component on the first floor, an exhibition room was completed in 1935 on the 5th floor and the so-called south studio followed in 1993 on the 6th floor. The north staircase, completed from 1987 to 1991, leads to the north hall on the 5th floor (1986 ) and on the 6th floor to the north studio (1987). In contrast to the western part, the walls and ceilings in the stairwell are painted with warm tones. The color scheme from the 1980s goes back to the concept of the Swedish painter Fritz Fuchs (* 1937).

Representative of humanity

The so-called representative of humanity with the work title The representative of humanity between Lucifer and Ahriman is the largest sculpture in the Goetheanum with a height of over eight meters and a mass of 20 tons . It was created by Rudolf Steiner and Edith Maryon from August 1914 at the time of the first Goetheanum . Since it was not installed in the Goetheanum at the time, because it was still unfinished, but in the high atelier of the carpenter's workshop, it survived the fire. The carved wooden sculpture, which was originally supposed to stand at the back of the stage in the Great Hall of the first Goetheanum, has been in a separate exhibition room on the 5th floor since 1935, accessible via the southern staircase. In the same exhibition room there is a model of the first Goethean conversion on a scale of 1:20 that can be accessed from the inside.

The group of figures is dominated by the central representation of a free-standing, energetic and steadfast Christ (→ Steiner's Christology ), who has raised his left hand and whose right arm points downwards. A rock formation forms the background from which a figure of Lucifer with broken wings protrudes on the right . Lucifer is plunged into the depths because of the superior power of Christ. The base of the sculpture is an implied cave in which the emaciated Ahriman is. Both Lucifer and Ahriman are depicted one more time to the left of Christ. In the 1960s, the first extensive restoration of the sculpture group and its preliminary studies were carried out. Despite the religious appeal, anthroposophists emphasize that the human representative is not a religious sculpture, but has to do with the entire fate of humanity. Contrary to the technically correct name, Rudolf Steiner deliberately described the statue as a wooden sculpture and not as a sculpture. He differentiated the term because he saw the manufacturing process of the sculpture as a living process from which the block of wood emerges into the "plastic". The sculpture was listed as a historical monument in 2011.

An actual interpretation of the figure remains difficult and the literature that has appeared on it offers a multitude of possibilities. The historian Helmut Zander , who dealt extensively with the history of anthroposophy in his habilitation thesis, described the representative of humanity as a sculptural ensemble, which in Steiner's worldview stands between materialism and spiritualism and is a kind of redeemer in the face of human threats. The question of which of the two artists had a decisive influence on the creation of the sculpture has been interpreted in recent research more in favor of Maryon, after her role had initially remained under-highlighted.

In 1935, a small “urn room” was set up as a prayer room in the same construction phase as the exhibition room for the group of the representative of humanity. It served the urn with the ashes of Rudolf Steiner and some of his employees and was ceremoniously opened on the tenth anniversary of Steiner's death. The entrance is in the exhibition room at the height of the plinth opposite the sculpture. In 1992 Steiner's urn - and then the others that had accumulated - were then buried in the memorial grove near the Rudolf Steiner Halde , so that this room has not been used since then.

Non-public spaces

The Goetheanum hardly has a cellar. The few and low basement rooms were expanded in the 1990s and used as an archive, warehouse and for technical facilities. The archive is connected from the basement to the boiler house via an underground corridor, and has been since the time of the first Goetheanum. The lack of basement rooms is compensated for by many rooms, niches and corridors. There is already a cavity around the Great Hall, which in places between the roof and the ceiling reaches a height of seven meters. The roof is supported by girders to which steel rods are attached for suspension. The lighting bridge with the central lighting unit is housed in such a space. The cavity continues on the sides into the air roots . Above the large hall there are two props stores on the top platform, which, among other things, accommodate thousands of theater costumes. From these rooms you can get into the spaces between the colored glass windows and the armored glass , which are only around 80 centimeters wide . Other rooms around the stage area can only be reached via two internal stairwells. They contain offices for stage operations, cloakrooms, an employee café and storage rooms for backdrops and props. Up until the 2000s, the north-eastern staircase was only in the raw state in the upper section and consisted only of concrete and iron reinforcement.

Ventilation and fire fighting system

There are a total of twelve ventilation systems throughout the house. In a ventilation system, fresh air is sucked into the basement from the so-called atrium - a free space between the superstructure and the terrace in the north-east - and then, after it has passed the heating units, is distributed under the floor of the large hall via ducts with a large cross-section . The large cross-sections ensure, on the one hand, that the airflow is not perceived as a draft, and on the other hand, the ventilation is technically extremely quiet. The air circulating in the hall is collected via the glass windows and the central light. The heat still contained in it is extracted by heat pumps and fed into the cellar to preheat the fresh air. The exhaust air is blown out through the roof.

In the same circuit, the air temperature can be reduced compared to the outside temperature. Two large water basins with 160 cubic meters of rainwater and 220 cubic meters of sprinkler water are available for cooling. If necessary, both pools can be used for fire fighting via a sprinkler system in the Goetheanum. The water for the toilets is available at the end of the fire-fighting water pipes. The water in the sprinkler basin is cooled to 6 ° C using heat pumps and the excess heat is fed into the rainwater basin. The water, which is cooled down with cheaper night-time electricity, can be channeled through the ventilation system into the hall during the day and cool it down by up to seven degrees.

Park and buildings in the area

The Goetheanum and the surrounding park form an ensemble that belongs together. Around the Goetheanum there are currently (as of September 2011) over 180 private residential buildings as well as administrative and functional buildings, some of which were also designed by Rudolf Steiner. The concept of the “colony” had already emerged when the first Goetheanum was being built.

Since it opened in the second half of 2011, you can explore the most important buildings in the settlement in Dornach and neighboring Arlesheim on the four architecture trails on the Dornach Hill.

The organic form of the Goetheanum is continued in the landscape design of the hill with furniture such as bench seats, garden gates or lanterns as well as landmarks. This also includes a viewing platform that can be reached via seven steps arranged in a ring . This is at the height of the so-called dragon's tail, from which a view of the northwest side of the Goetheanum is possible. The excavation of the Goetheanum was used to design the hilly landscape .

For the planting of the area around the Goetheanum, Steiner issued the instruction that the simplest and cheapest possible plants and trees should be used. To this day, the garden is largely an orchard meadow . Some parts are planted with evergreens and privet hedges . Steiner chose both the garden architecture design of the 45,000 square meter site and its planting in such a way that the main attention is drawn to the Goetheanum. To the west of the Goetheanum runs a wide avenue with benches and road stones 77 and 125 centimeters high every eight meters. The avenue is a “promenade” for those “who step out of the building, but still want to remain in its full range” - says Bernardo Gut about the design.

Landscape park

The landscape park at the Goetheanum was redesigned and laid out in 1954 by the anthroposophical garden architect Max Karl Schwarz (1895–1963) from Worpswede , according to Steiner's only partially implemented garden concept . Max Karl Schwarz was one of the most important pioneers of biodynamic horticulture and the architect of the first anthroposophical settlement project in Loheland near Fulda, as well as the inventor of various composting methods. He began with the care of the Rhaetian gray cattle, which was already extinct in Switzerland, and introduced the biodynamic management of the landscape park at the Goetheanum, which is still in place today, and which was precisely tailored to the small and long-lived cattle variety. He has also published and implemented this many times in his well-known gardener farm concepts for the self-sufficiency of families and communities.

Boiler house

The heating building erected in 1915, the first concrete building in this ensemble, is one of the most striking buildings around the Goetheanum. The two-storey substructure with windows on each floor has a sculptural superstructure that is reminiscent of a sphinx due to its shape . The chimney is concealed behind a branching, tree-like structure. According to Steiner, the smoke is divided into a physical and an ethereal part; the physical is represented by the chimney, the etheric by its laterally escaping branches. The boiler house on the northern edge of the hill still serves as a heat supply. However, in the early 1990s, the original coal-fired heating system was replaced by a gas-powered combined heat and power unit . This made it possible to heat 15 more buildings. The boiler house, which is connected to the Goetheanum via an underground tunnel, produces around 250 kW of heat and 190 kW of electricity.

Transformer house

Another noteworthy functional building is the transformer house at a road crossing in the southwest of the hill. The building, designed by Rudolf Steiner and built in 1921, stands out due to its cubic cantilevers with gable roofs reaching in all directions. The overhead lines branched off at its gable ends. Today it is operated by the local electricity company and is still used as a public power supply. It is unknown whether Steiner thought of safety aspects when separating the transformer and boiler houses from the Goetheanum. He understood technology as an "ahrimanic-demonic force" that was to be revealed by means of "inherent" architecture in order to render its negative forces harmless. At the same intersection opposite the transformer house is the building called the dining room . It serves as a cafe, restaurant, boutique and bakery.

Carpentry and high atelier

Southeast of the Goetheanum is the carpenter's workshop from 1913. It is a simple, wood-paneled building and was the carpentry's place of work during the construction of the first and second Goetheanum, but also a place for cultural events such as lectures and performances. The building was erected as a temporary measure for the joinery and carpentry work of the first Goetheanum. The barrack-like building, originally without foundations, now covers an area of 2800 square meters. It was used when the Goetheanum was not yet completed, and then until today, for rehearsals and as a lecture hall. The dilapidated carpentry complex, which also includes the high atelier, was expanded and renovated in the 1980s. The buildings also received foundations under their wooden structure. Rudolf Steiner's work studio, located next to the high atelier, became his hospital room from October 1924. He spent his last six months in it and there he died on March 30, 1925.

Glass house

The glass house or glass studio , also built in 1914, consists of two separate cylindrical structures with separate domed roofs. Between the cylinders there is a balcony on the roof of the central building that can be accessed from both of the clapboard-covered domes. The glass house was set up to work on the windows built into the Goetheanum.

Today it serves the "Natural Science Section" and the "Section for Agriculture" of the School of Spiritual Science. The west dome houses a seminar room, the east dome houses a library and the lower floor houses workshops and offices. The shape of the wooden house is reminiscent of the first Goetheanum building.

House Duldeck

To the west of the Goetheanum and not far from the footpath that leads to the west facade as a central axis , the Duldeck House , built in 1915 from concrete and in which the Rudolf Steiner Archive has been housed since 2002 , stands on the edge of the hill in a small round square . The two-storey house, which also houses rooms, is structured by a cornice , pilasters and curved beams and has a heavily modeled roof.

Friedwart House

The Friedwart house is to the northwest, directly below the Goetheanum. It was created by the architect Paul Johann Bay (1891–1952) based on designs by Rudolf Steiner. The building, originally designed as a residential building, was made available to the anthroposophical movement in 1921. After various secretariats of anthroposophical institutions, it housed the “advanced training school at the Goetheanum”, the first school in Switzerland based on Waldorf education. Today the Friedwart house is operated as a bed and breakfast hotel with 23 beds.

Rudolf Steiner Halde

The Rudolf-Steiner-Halde is halfway between the Goetheanum and the Friedwart House . The architectural peculiarity of the building, which was called "Haus Brodbeck" before the renovation and was built as a summer residence in 1905, is a northern extension designed by Rudolf Steiner and built in 1923 shortly before the second Goetheanum. In particular with regard to the use of the exposed concrete, it served as a test building for the upcoming new building project. The annex initially served as a eurythmy and was called that at that time. The entire Rudolf-Steiner-Halde was completely renovated in 2003/2004. Today it is mainly used for meetings. It houses the “Section for Fine Sciences”, the “Section for the Speaking and Musical Arts”, the finance department and the puppet theater.

Memorial grove with urn cemetery

Adjacent to the Rudolf-Steiner-Halde is the memorial grove , in which the urns of people who felt connected to the anthroposophical movement are buried.

The ashes of Rudolf Steiner, his second wife Marie von Sivers and those of the poet and writer Christian Morgenstern , who felt a special spiritual togetherness with Steiner, rest here . After Steiner's death in 1925, the urn with his ashes was initially kept in his study and death room. In 1935 a small “urn room” was set up in the Goetheanum, which contained Steiner's urns and some of his colleagues. Over the years, more urns were added before the decision was made towards the end of the 20th century to place the urns in the park of the Goetheanum.

In the course of this project, the first half of the urns was buried in the early morning hours of November 10, 1989, before sunrise, in the pine grove between the Goetheanum and Rudolf-Steiner-Halde. On November 29, 1990, in the early hours of the morning, the second part of the urns that had been in the Goetheanum until then was handed over to the earth in the memorial grove. In both cases, the urns, which were mostly made of copper, were replaced by wooden containers before burial so that the earth could soon connect with the ashes. With the burial of Rudolf Steiner's ashes on November 3, 1992 in the presence of the board of the General Anthroposophical Society and a celebration on November 21, 1992, the burial of all urns from the Goetheanum in the memorial grove was completed.

Eurythmy houses

The three eurythmy houses south of the Goetheanum were built in 1920. The residential houses designed by Edith Maryon were intended to provide living space for employees of the Goetheanum with minimal income.

De Jaager house

Also to the south is Haus de Jaager , built in 1921 , which served both as a residential building and as a studio. It is named after the Belgian sculptor Jaques de Jaager, who lived in this house and exhibited his works. The design made by Steiner for this house was implemented by the architect Paul Bay. The angular and angular structure on the one hand anticipated the current shape of the second Goetheanum somewhat; On the other hand, however, it also quotes the double dome of the first Goetheanum in a modified form. The as studio used building depends on over the other used as apartment buildings, which annex to the studio building around on three sides.

use

The Goetheanum sees itself as a conference, cultural and theater building and not as a church . Therefore, there were no church rooms or meditation rooms. Art exhibitions take place regularly in the rooms of the Goetheanum. Around 250 people work on the “Goetheanum Campus”. Every year around 150,000 people visit the Goetheanum. Around 800 colloquia , conferences and courses take place every year. The building is owned by the General Anthroposophical Society. Economically, the building is mainly maintained through event income as well as membership fees and donations from around 46,000 members.

Culture and science

Faust performances are regularly presented on the stage of the Goetheanum. Scenes from Goethe's Faust were shown in the first Goetheanum , even on the evening before the great fire. The performance practice was continued in the second Goetheanum shortly after the opening. In 1937 the Goetheanum Ensemble even traveled as an official Swiss contribution to the world exhibition in Paris with scenes from Faust . In 1938, for the first time worldwide, 106 years after the publication of the work, which had long been considered unplayable, both parts of Goethe's Faust were presented in a seven-day mammoth production (→ List of important Faust productions ). Rudolf Steiner's widow, the actress Marie Steiner von Sivers, staged the performances . The festival with complete performances of Faust I and II has continued since then. In 2015–2017, Faust I & II was again performed unabridged in its entirety, replacing the penultimate production from 2004.

The second use of the large hall, also mostly organized like a festival, concerns performances of Steiner's four mystery dramas. Mostly in a continued tradition since the world premieres in Munich and since the opening of the second Goetheanum, the performances are framed by explanatory lectures and (artistic) courses. Spectators need perseverance and patience with a total playing time of around 25 hours. Nevertheless, the game is often played in front of a sold out house (almost 1000 seats). In 2012 three performance cycles were played. The sentence “We have already thought of something like Bayreuth”, uttered 100 years ago by Steiner before the foundation stone was laid for the Donateur of the Goetheanum site in Grossheintz, has proven to be quite prophetic.

The other cultural program includes conferences on various topics from culture and science, concerts, eurythmy , opera and theater performances, visits, guided tours and exhibitions. In the last decades, the use as a congress center for the mostly multilingual annual and world congresses from the anthroposophically inspired areas of life, such as education ( Waldorf education ), medicine ( anthroposophic medicine ) and agriculture ( biodynamic agriculture ) has increased significantly. The meetings, which were almost exclusively European in the early days of the Goetheanum, have become much more international due to this development.

Administration, university, archive

The Goetheanum houses a bookstore, the editorial office of the magazine Das Goetheanum , a eurythmy school, a course in sculpture and offers many other artistic courses. The General Anthroposophical Society and the School of Spiritual Science with their eleven specialist sections have their headquarters here. The General Anthroposophical Society is the umbrella organization of the various national societies in which general issues of time and life are dealt with in study groups and reading groups. Central questions of anthroposophy are researched in the School of Spiritual Science. These include the areas of medicine, education, visual arts and social sciences. The Goetheanum also includes the facilities in its immediate vicinity, such as the garden center, restaurant and the publishing house at the Goetheanum .

In the eastern part of the building there is an anthroposophical library with over 110,000 titles, which presumably includes all relevant anthroposophical writings. In addition, the Goetheanum houses an archive with around four million documents, an art collection and the building administration's plan archive with over 8,000 architectural plans.

Interpretation as a temple

Looking at the exposed location, the design of the building and the central role it plays for the anthroposophists, the question inevitably arises as to whether the Goetheanum cannot be viewed as a temple . The anthroposophists themselves, however, avoid the term and speak neutrally of a “building”, especially in modern literature. This attitude did not yet exist at the first Goetheanum. The French writer Édouard Schuré , who is close to the anthroposophists, said shortly after completion that "the architectural synthesis of the building [...] has the character of a temple". The builder of the Malsch model Stockmeyer even described the building as a "sublime place of worship" in an essay in 1949, and Steiner himself commented on this before the building was built in 1911:

“In a certain way we are supposed to build a temple that is at the same time, as was the case in ancient mystery temples, a teaching facility. In the course of the history of human development, we have always called 'temples' all works of art that enclosed that which was most sacred to people. "

In fact, there are many indications of a temple being built in the first Goetheanum. Due to the special topography, the building assumed a dominant position - even more so due to the lower level of development at the time. The elaborate landscaping, the exact easting and the mystical-ceremonial laying of the foundation stone on September 20, 1913 in front of selected people reinforce the cultic character. The original plans went even further: they wanted to build a kind of wall around the double- domed structure and planned three central access roads. The houses in the immediate vicinity of the central building should be arranged in the form of a pentagram . In fact, these plans were not implemented because the natural conditions did not allow them to be realized. The interior of the stage and the auditorium also has a special design with columns and colored glass windows with sacred set pieces. Even the laying of the foundation stone itself was a date that followed a cosmic constellation, and the fact that the act took place in the light of torches, was mystically and ceremonially documented by its short-term announcement for a selected group. For all these reasons, the first Goetheanum can very well be viewed as a temple.

The second Goetheanum, as the immediate successor, takes over the orientation and location of the first building, but its design is much more restrained overall. Due to the conception with different halls and rooms, it is conceptually more geared towards the functionality for the School of Spiritual Science. Steiner and his followers were well aware of the mystical-sacred association, but they did not want it. The renaming of the first building from Johannesbau to Goetheanum should counteract this impression. An ambivalence remains. During the last renovation of the large hall, there was intense debate about artistic issues. However - according to the Goetheanum analyst Ramon Brüll in an article on the current financial situation of the Goetheanum - they failed to address the question of whether they wanted to primarily build a place of worship, a theater or a congress center. It also remains contradictory that the figure of the representative of humanity, which is significant for the anthroposophists, looks like a guardian over the entrance of a now orphaned room in the Goetheanum, which until 1993 served as a columbarium for the urn with Steiner's ashes.

The ongoing discussion about the location of this statue is another element that suggests the conclusion that there is ultimately disagreement internally in the Goetheanum as to “how much temple” is now wanted.

reception

Architectural classification

Even when the first Goetheanum was built, myths and rumors grew up about the building erected by the anthroposophists. When the foundation stone was laid for the first building, Rudolf Steiner had two copper dodecahedra made by Max Benzinger , a parchment certificate set in concrete and his hands crossed. The arrival of anthroposophists in general, the monumental building activity that then began and the elements of the Rosicrucian ceremony aroused alienation, fear or even rejection among the locals. In addition to rumors that sometimes seemed bizarre, such as that a “Buddhist monastery” would be built on the hill or that a living person would be buried when the building was founded, there were serious efforts to stop the building process via the government in Solothurn. As different as the reactions to the work of Rudolf Steiner and the Anthroposophical Society were from admiration to rejection in the past and remain controversial to this day, the evaluation of the Goetheanum is just as different. Steiner himself wrote about the Johannesbau - as the first Goetheanum was originally called - he did not build on a historically transmitted art form and denied references to Art Nouveau and Expressionism . In fact, the building actually shows parallels to architecture around 1900 and has practically no roots in older styles. The east portal in particular was reminiscent of Art Nouveau windows. The gooseneck-shaped stair posts designed by Edith Maryon and the concrete substructure also cite this formal language.

The second Goetheanum, which Steiner himself described as angular, was in part not popular even among anthroposophists. They sometimes disparagingly referred to the roughly structured substructure as “the garage”. The fact that the subsequent building can be understood as a kind of fortress is understandable in the context of the fire disaster ; it should explicitly offer “a kind of protection for those who look for spiritual things in this Goetheanum”, paraphrases Hagen Biesantz Steiner. In order to achieve this, the symbolic forms of the previous building had to be dispensed with, which led Steiner to describe the building as “much more primitive”, since one had to work with the “brittle concrete material”. The Swiss Homeland Security spoke out vehemently against the construction.

The overall aesthetic perception, but also the assessment of the architectural significance and its classification, are inconsistent. The anthroposophist Hagen Biesantz describes the building in the quasi-official publication as a “fortress-like concrete structure”, a term that even goes back to Steiner himself. The architectural historian and non-anthroposophist Wolfgang Pehnt described the building as "one of the most unique architectural sculptural inventions that the 20th century has to show". The exterior of the singular building even shows the spirit of functional brutalism - which did not exist in the 1920s - while the cubic forms of the foyer, which were designed between 1983 and 1984, cite postmodern forms. The two Italian architects Mario Brunato and Sandro Mendini, who in an article in l'architectura 1960 described Steiner as a great expressionist who created masterpieces, but ultimately did not show any new paths for modernity, were much more critical .

The Japanese architecture professor Imai Kenji , who went on a study tour through Europe in the mid-1920s, visited the still unfinished Goetheanum in 1926. Impressed by the avant-garde architecture of Walter Gropius , he contrasted the Bauhaus movement, which he called “architecture of the practical”, with Steiner's and described the latter as “architecture of eternity”. In this building he saw the “sun of peace”, which was in harmony with people, and appealed to architects to visit the Goetheanum and think about its essence and value. Dennis Sharp even found that the Dornach buildings had “erotic features” that “probably marked a closeness to nature”. Sharp, who described the Goetheanum as an open sculpture in which people move and find a new meaning for existence, saw Rudolf Steiner's progress as an architect by looking at the two Goetheanum buildings over time. Hans Scharoun even described the Goetheanum as one of the most important buildings of the first half of the 20th century.

As euphoric and emotional as some architects expressed themselves about the building, it remained completely unmentioned in some publications, such as the standard reference work of the time Penguin Dictionary of Architecture by Pevsner , Fleming and Honor, until well into the 1960s. This is all the more astonishing because it was precisely at that time that interest in Gaudí's work and in sculptural monolithic buildings - triggered by the completion of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1963 - was reawakened. The art scholar Reinhold Fäth cites the reason for the ignoring attitude towards Steiner's architecture that in many respects he was perceived as an occult rather than an actual artist. In addition, it would be necessary to read Steiner's four hundred volume complete edition in order to form a judgment, and other source materials from anthroposophical authors sometimes do not meet the scientific requirements. Only in 1971 was there a brief entry in the German edition Lexikon der Weltarchitektur . A classification of the Goetheanum remains controversial even in anthroposophical circles. In 1965, the architect Ilse Meissner-Reese wrote in an article for the magazine Progressive Architecture that the classification in "Expressionism" or even in "German Expressionism" was a constraint, since the building was completely "unclassifiable" in the real sense.

In 2004, the Swiss art journalist Susann Sitzler described her impressions of the Goetheanum as follows:

“[…] The building does not make it easy for unprepared visitors. Outside the gate, external dignity is transformed into imperious authority. Clumsy concrete beams jut out of the room, asymmetrical windows direct your gaze into the empty sky, your breath echoes strangely in the gloomy stairwells. Everything is huge and clunky. [...]