Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester

Simon IV. De Montfort (* around 1160; † June 25, 1218 before Toulouse ), lord of Montfort-l'Amaury , Épernon and Rochefort , was the military leader of the Albigensian crusade from 1209 until his death . He became the 5th Earl of Leicester by inheritance and, due to his conquests in the Albigensian Crusade, Vice-Count of Carcassonne and Béziers , Count of Toulouse and Duke of Narbonne .

Early years

Parentage and family

Simon was the son of Simon (IV.) De Montfort , whom he succeeded in 1188 as lord of Montfort-l'Amaury, Épernon and Rochefort. Although he was the fifth of his name from the Montfort family, the ordinal number "IV" has established itself for him as a result of an error in older historical research, since his father has long been considered identical to his grandfather Simon III. († 1181) was identified. His mother was Amicia de Beaumont († 1215), the eldest daughter of Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester . Around 1190 he married Alix de Montmorency , a daughter of Bouchard IV. From the widely ramified house of Montmorency in northern France . Together they had six, maybe eight children:

- Amaury VII. De Montfort (* around 1199, † 1241).

- Guy de Montfort (* around 1199, † April 4, 1220): iure uxoris Count of Bigorre .

- Amicia de Montfort († February 20, 1252): ∞ with Gaucher de Joigny († before 1237), Sire of Châteaurenard.

- Simon de Montfort (* around 1208, † August 4, 1265): Earl of Leicester and Lord High Steward of England.

- NN (* February 1211, †?): Daughter, probably born in Montréal , baptized by Dominikus de Guzmán , became a nun in the Cistercian monastery of Saint-Antoine-des-Champs near Paris. Probably identical to Pétronille.

- Robert de Montfort (* / †?).

- Pétronille de Montfort (* / †?): Named in 1237 as the sister of her brother Simon.

- Laure de Montfort (filiation disputed; † after 1227): ∞ with Gerard II. De Picquigny, Vidame von Amiens .

The Montfort estates, with their headquarters in Montfort-l'Amaury, were concentrated in the historic Yvelines landscape , where they gained a predominant position over the other local lord families by the 12th century due to the skillful increase in ownership of the older generations. Overall, they belonged to the baronial class of Île-de-France , which is why they are not counted among the high feudal nobility of Northern France. Due to its borderline to the Norman duchy , which belonged to the " Angevin Empire " in the late 12th century , the family still had a certain importance, which could be consolidated through multiple ties to the neighboring Norman nobility. Simon's mother, for example, was a member of one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman families who owned large estates in both France and England. After her brother Robert de Beaumont, 4th Earl of Leicester , died in 1204 without heirs, Amicia inherited half of his property as well as the right to the county of Leicester and the office of Lord High Steward , a position of importance at the court of the English king at the time . This inheritance was granted to Simon in 1206, and in early 1207 the inheritance was shared with his aunt Margarete de Beaumont and her husband Saer de Quincy, 1st Earl of Winchester , although Simon retained the legal right to the title of Earl of Leicester. But because he confessed his allegiance to the latter in the conflict between King John of England and King Philip II of France , all English goods were confiscated from him by King John in February 1207 and the income confiscated. However, under papal pressure, he had to transfer it to Ranulph de Blondeville, 4th Earl of Chester , in 1215 , who was allowed to administer it as trustee of his cousin Simon and to use her income until Simon took possession of it.

If Simon appears in contemporary documents and chronicles as "Count Simon" or as "Count of Montfort", it is a matter of courtesy stating that he is entitled to inheritance in the English county of Leicester. Demonstrating his claim to them, he called himself exclusively "Earl of Leicester" in his own documents. The Seigneurie Montfort-l'Amaury was only upgraded to a county for his son, to compensate for the loss of power in Languedoc .

Fourth crusade

Little is known about Montfort's early years; presumably he often spent it in the wake of his uncle Robert de Beaumont. In January 1195 he appeared as one of three guarantors of his uncle's promise of peace to King Philip II August.

On December 28, 1199, Montfort took together with Count Theobald III. von der Champagne and Louis von Blois took the cross for the Fourth Crusade , after having previously listened to the sermons of Fulk von Neuilly at a tournament in Écry . He was also joined by his younger brother Guy . The company was soon under the control of the Venetian Maritime Republic , which took over the army's ship transport to Syria. In return, the republic demanded the use of the crusader army for its own interests in order to besiege the Adriatic port city of Zara , although Pope Innocent III. warned the crusaders against attacking Christians. After Zara had nevertheless been stormed and the leaders had decided to divert the crusade to Constantinople , Montfort and some loyal followers left the crusade army at the court of the King of Hungary in April 1203. From there they traveled independently to Outremer to take part in some campaigns against the Saracens , while the crusade continued to Constantinople, Venice's greatest trade rival, and conquered this city in the spring of 1204.

When exactly Montfort returned to his homeland is unclear, he was first mentioned in documents in 1206 when he testified that his mother had sold Breteuil to the French king.

Crusade against the Albigensians

Election to leader

Simon de Montfort's name is inseparable from that of Pope Innocent III in 1208 . declared Albigensian Crusade , of which he was the military leader for several years until his death. His motives for participating in this company remain unclear; that one day he would become the leader of the crusade and thus the main beneficiary of his conquests, was still in the stars at the beginning of this campaign. Allegedly, he first had to go through Duke Odo III be persuaded by Burgundy to participate, as the goal of this crusade would not be compatible with his Christian ethos. Because instead of against unbelieving Moors or Saracens in Outremer or Spain, the campaign should be carried out against the Cathar religious community , also called "Albigensians" , which is widespread in the southern French region of Languedoc or Occitania , and whose doctrine is dualistic Form of Christianity acted, but which was classified by the Roman Catholic Church as heretical and therefore condemnable. For their part, the Cathars had recognized the manifestation of the Antichrist in the Church of the Pope . After the Roman Church had tried in vain for several years to push back Catharism through sermons and missions, Pope Innocent III was. first came to the conclusion in 1207 that only a crusade could destroy heresy and its accomplices. In order to create the necessary incentives for such an enterprise, he had laid down the principle of the confiscation of all goods from convicted heretics or their supporters by the crusaders, which equates to a principle of conquest that will be decisive for Simons de Montfort's future actions.

However, the Pope had wanted the King of France, Philip II August , to be the leader of the crusade, who, however, had turned down several requests to take the cross and was generally rather disinterested in this undertaking. Thus, the crusade legate Arnaud Amaury , abbot of Cîteaux, and the three great secular princes Odo III were at the head of the crusade army, which gathered in Lyon in the spring of 1209 . posed by Burgundy , Hervé of Nevers and Walter of Saint-Pol . Montfort himself initially belonged to the army as a simple crusader and took part in the conquests of Béziers (July 22nd) and Carcassonne (August 15th), where he had distinguished himself through his bravery in the latter. The Vice Count of Béziers-Carcassonne, Raimund Roger Trencavel , was imprisoned in a dungeon as a supporter of the heresy and declared forfeited of his titles and domains in accordance with the applicable expropriation principle. After both the Counts of Nevers and Saint-Pol as well as the Duke of Burgundy had rejected the now vacant fiefs, the legate Arnaud Amaury found in Simon de Montfort, as the next-ranked nobleman, the all too willing recipient and thus also a new military leader of the crusade. The reasons for Montfort's acceptance of the Trencavel legacy are also controversial, it is possible that he considered it to be a compensation for the Beaumont legacy he lost a few years earlier. He immediately expressed his gratitude to Arnaud Amaury by donating three houses in Carcassonne, Béziers and Sallèles to the Cistercians , who had previously been expropriated by heretics. The deed of donation was the first that he signed as “Vice Count of Béziers and Carcassonne”. Montfort also immediately reinstated the church tithe, which had not been levied in Languedoc for generations, and introduced annual interest of three denarii per household in favor of the Holy See.

At the end of August 1209, however, the crusade was not as good as most crusaders had left the army for their homeland after the prescribed minimum combat time of forty days. Near Montfort there were only a handful of knights left in Carcassonne, mostly related and loyal companions from the fourth crusade. Of the great princes he was only able to persuade the Duke of Burgundy to stay longer. Opposite them stood almost the entire knighthood of a country of which Montfort was now master. As a result, he claimed feudal rule over those former Trencavel vassals who, however, had decided to resist the crusade. Montfort had now set itself the goal of submitting them, with the result that the crusade increasingly assumed the character of a feudal war that was formative for its entire duration and maneuvered Montfort into a complicated network of long-established legal habits and political orders. First he marched into the Lauragais , a stronghold of heresy, where Aimery de Montréal submitted to him without a fight. The main goal, however, was the capture of Fanjeaux , which was strongly catharic and an important traffic junction in the region. When the crusaders moved in, the large Cathar community fled to the exile Montségur under their leader Guilhabert de Castres . Montfort, on the other hand, first made the acquaintance of the monk Dominikus de Guzmán , who had been preaching against heresy with modest success for a few years with a few converts. Montfort made Fanjeaux his actual headquarters, from where he could undertake star-shaped raids into the surrounding area. With the capture of Laurac , Saissac , Villesiscle and finally Limoux , the most important towns in the Lauragais were captured within a few days. Only the castles of Lastours , a strong nest of resistance, were able to successfully defend themselves against a siege, whereupon the Duke of Burgundy began his journey home and thus further weakened the crusader army. In September 1209, however, the town leaders of Castres offered voluntary submission and held several hostages for their loyalty. They also handed over two arrested Cathars who were burned at the first stake under the aegis of Montfort.

Around the same time, Montfort took up the siege of Preixan , a city that did not belong to the domains of the Trencavel, but to Count Raimund Roger von Foix , with which he committed a clear violation of the law. Although the count was considered a sympathizer of the Cathars, he had submitted to the church a few months earlier and thus placed himself and his country under the protection of the Holy See. Montfort negotiated his free entry into the city with the Count, who immediately arrived before Preixan, so as not to touch the other Count's domains for his promise. He broke this promise when, in September 1209, the abbot of Saint-Antoine de Frédélas offered him the shares of the Count of Foix, with whom he had been enemies for years, over the joint rule of Pamiers . Montfort immediately occupied this city and at the same time Mirepoix and Saverdun , i.e. in fact the entire lowlands of Foix, whose highlands he thus cut off from Toulousain, which was entirely in view of his already mature plans. He then moved to the north, where, after taking Lombers and Albi without a fight , he subjugated the Albigeois . Raimund Roger von Foix, who saw the Preixan Pact as broken, used his absence to drive the Crusaders out of the city and to launch a direct attack on Fanjeaux on September 29th, which the Crusaders were able to repel. These were also the last military activities of the year 1209, after which the crusaders withdrew to their winter quarters.

Political conditions in Languedoc

On November 10, 1209, the young Raimund Roger Trencavel died in his prison in Carcassonne. The immediately immediate rumor of Montfort's murder assignment was rejected by the crusade writers as unjustified. They attributed his death to a dysentery he had contracted while in captivity . On November 24th, Montfort met the widow of his deceased predecessor in Montpellier , who on behalf of her son, Raimund II Trencavel , ceded all Trencavel rights to him for an annuity of 3,000 sous and the reimbursement of her dowry of 25,000 sous. The young Trencavel, who was never to acknowledge this sale of his rights, was placed in the care of the Count of Foix.

Another important meeting was in Montpellier with King Peter II of Aragón , because the Crown of Aragon was the overlord of the vice-counties of Béziers and Carcassonne and the Trencavel had therefore been their vassals. Montfort now hoped for recognition from the king as his vassal, with which his takeover of the vice-counties would be sanctioned under secular law, which until now was based solely on the principle of prey declared by the pope. In addition to buying the Trencavel rights, he had therefore already sent his knight Robert Mauvoisin to Rome in October with a letter with which he wanted to obtain the Pope's approval for his election as crusade leader and his appointment to the vice-counties. The crusade was not only under the direction of the Holy See, the Pope was also the secular overlord of the King of Aragón, since the latter had willingly given vassalage to Rome in 1068 as an expression of a Catholic creed. King Peter II personally traveled to Rome in 1204 to meet Pope Innocent III. to swear the feudal oath. The word of the Pope was also of importance in matters of the geopolitical order of Languedoc and Montfort now hoped, based on a positive answer from Rome, to receive the recognition of the Aragonese king. However, the positive reply from the Pope had only just been written in November and was sent to Languedoc, where it was not due to arrive until December 1209. In Montpellier, King Peter II refused to recognize Montfort. In all matters of secular feudal law, the king had been ignored until then, and his vassals were either deposed or attacked without his consent, even if they enjoyed the protection of the Holy See. Regardless of this, Montfort continued his efforts to establish a good relationship with the king, which, however, were observed with growing suspicion from his side and which ultimately ended tragically.

Count Raimund VI provided another decisive power factor in the region . of Toulouse , who ruled the most powerful of all the principalities of Occitania. For his domains he was by right a vassal of the French king, although this vassal only existed on paper, de facto the county of Toulouse had been a sovereign principality for generations. More than any other Occitan prince, Raymond VI. the suspicion of heresy and was considered the most important patron of the Cathars. For the crusade legates, above all Arnaud Amaury, the overthrow of the Count of Toulouse as a prerequisite for a successful fight against heresy had been out of question from the start. Among other things, they had made the count responsible for the murder of legate Pierre de Castelnau in 1208, who had only provided the pretext for the crusade. Count Raimund VI. but had initially skilfully avoided confrontation with the crusade by submitting to the church in good time, and had placed his lands under the protection of the Holy See. But in September 1209 the crusade legates had taken the refusal of the city superiors of Toulouse to take the required oath of allegiance to the church, the excommunication also about Raymond VI. to speak out and clear the way for fighting it. This opened up new perspectives for Montfort to conquer the largest principality in Languedoc.

Submission of the Carcassé

In the meantime, however, the situation had deteriorated considerably for the crusade by the winter of 1209. While Montfort was staying in Montpellier, about forty towns that he had subjugated over the past few months had fallen away from him and driven out the crusader garrisons. These included important places such as Castres, Lombers and Montréal. This had taken place under a general uprising of the local knighthood, who after the shock of the first successes of the crusade had now found themselves ready to resist it. Only after his wife had brought the first reinforcement troops since the beginning of the crusade in Pézenas in March 1210 , could Montfort begin an offensive to recapture the defected places. First he subjugated Montlaur, then Alzonne and finally Bram . The recaptures were accompanied by executions of local nobles whom Montfort now regarded as renegade vassals. In order to intimidate the population he first used the means of terror in Bram to demonstrate the consequences of the resistance against him. He had 100 citizens of the city gouged out their eyes and left only one eye so that it could lead people to the castles of Lastours , the stubborn nest of resistance of Pierre Roger de Cabaret . After destroying the vineyards of Cabaret and Minerve, after a two-week siege in April he took Alaric Castle at the foot of the Corbières , home of the later infamous Faydit Xacbert de Barbaira .

Thereupon Montfort was held by King Peter II to Pamiers for a summit conference with Raimund VI. invited by Toulouse and Raimund Roger von Foix, which ended without result. Montfort then mocked the Count of Foix by pulling in arms up to his castle. However, under pressure from the Aragonese king, he had to guarantee the integrity of the Foix domains for a year. Instead, he took up the siege of Minerve , which was one of the most heavily fortified Cathar nests in the region. The siege lasted seven weeks from early June to mid-July 1210 and was the longest of the entire crusade to date. The crusaders were decisively strengthened here by the arrival of a large contingent, in which, according to Wilhelm von Tudela's words, knights from Champagne , Maine and Anjou , Brittany , Friesland and Germany participated. On July 22nd, the defenders announced their surrender and handed over the castrum to Montfort. 140 Cathars present were burned in the first major mass cremation of the crusade. Only three women could be persuaded to save, through the mother of Bouchard de Marly . The fall of Minerve had resulted in the voluntary submission of Montréal, Ventajou and Laurac.

Taking advantage of the warm season and the reinforcement troops present, Montfort immediately took up the siege of Termes , another of the great nests of resistance in Carcassé. Despite his numerical superiority, which the influx of crusaders from northern France, Brittany and Gascony, from Brabant, Friesland, Saxony and Bavaria guaranteed, this siege lasted three months. Only on November 23, 1210 did the defenders capitulate after a dysentery broke out. Afterwards , moving along the valley of the Aude , Montfort subjugated a few more castles, Puivert surrendered after three days of siege. Then Castres and Lombers again submitted to him without a fight. At the end of 1210 there was only one significant nest of resistance left in the former Trencavel lands, the castles of Lastours.

Battle for Toulouse

While Montfort spent the whole of 1210 with military activities, the spiritual crusade leaders around Arnaud Amaury had that of Pope Innocent III. Requested investigation procedures regarding the against Raimund VI. allegations made by Toulouse sent delayed. Instead, they had confirmed the excommunication against the Count in November 1210 and at the same time extended it to the Counts of Foix and Béarn. Nevertheless, the Pope continued to push for a diplomatic solution to the situation, but Montfort could rely on his silent agreement with Arnaud Amaury, who from the winter of 1210 confronted the Count with unfulfillable conditions for his absolution and thus prevented it. At the same time, the legate had used his diplomatic talent to achieve a reconciliation between Simon de Montfort and King Peter II of Aragón. The general political weather on the Iberian Peninsula had played a role for them, where a war between the Christians and the Moors was announced, for which the king on the northern slope of the Pyrenees required calm conditions. In January 1211, at the General Council convened in Narbonne , the king finally received the homage to Simons de Montfort, which concluded his takeover of the Trencavel lands in accordance with all the rules of secular law. In return, Montfort gave a guarantee for the inviolability of the lands of Foix, which were a protectorate of Aragon. Relations with the king were strengthened a few days later in Montpellier , where the council had adjourned, through the agreement of a marriage between the Aragonese crown prince Jakob and Montfort's daughter Amicia . Because following the customs of the time, the young prince was entrusted to the Montforts family to educate . Montfort's triumph in diplomatic intrigue was at the same time by the final rejection of a reconciliation by Raimund VI. completed by Arnaud Amaury, who on February 6, 1211 once again proclaimed the condemnation of the Count and suggested its confirmation to the Pope. The outcome of the Council of Narbonne-Montpellier resulted in immediate reactions; Pierre Roger de Cabaret, discouraged, had given up his resistance and in March 1211 surrendered his castles from Lastours to Montfort without a fight. The last military obstacle in Carcassés was thus cleared and Montfort had free rein to conquer the wealthy Toulouse, which now had no notable patron.

In March 1211, Montfort had begun the siege of Lavaur , the first city in the domain of the Count of Toulouse, even before the Pope excommunicated Raymond VI in April. had confirmed. Lavaur was conquered on May 3rd, and all the resistance members were condemned as apostates and hanged, including Aimery de Montréal, who had paid homage to Montfort twice and broken his oath both times. His sister, Mistress von Lavaur, was thrown into a well by the Soldateska and stoned to death. All the Cathars apprehended in the city, between 300 and 400 in number, were burned at a stake that would not only be the largest of the entire crusade, but also the largest in the 150 years of the Cathar persecution. Among the defenders, some officers of the Count of Toulouse were also picked up, whose active action against the crusade was thus revealed, which could also justify his excommunication. The castra Montgey and Puylaurens then declared their submission without a fight, the castle Les Cassès was ready to resist, but had to surrender after a short siege. Up to 60 Cathars were burned here, on the last great pyre of the crusade.

In the summer of 1211, the first counter-attack was made by the Count of Toulouse, who took Castelnaudary, held by the crusaders, by surprise and had the strategically important Montferrand secured by his brother Baldwin . Montfort immediately took up their siege, and Baldwin's stubborn resistance surprised him. Instead of dwell in protracted battles, Montfort entered into negotiations with Baldwin, of whose bad relationship with his brother he knew. By promising him rich rewards, he succeeded in May 1211 in winning Baldwin to his side and taking Montferrand with little effort. Subsequently, Montfort took possession of Castelnaudary again and subjugated several cities along the Tarn in a real lightning strike : Rabastnes , Montégut, Gaillac and Lagrave . From there he marched along the Aveyron into the Rouergue and the Quercy . There he was in Bruniquel by Raimund VI. expected, who in a conversation offered his submission, provided his inheritance would remain intact. Montfort immediately refused, an indication that it was not in his mind to subjugate the count to the will of the church, but to take over his principality. From Bruniquel the march continued south to Montgiscard , where a large reinforcement force joined the crusaders, whereupon Montfort held himself strong enough to siege Toulouse . On June 15, 1211, the crusaders marched in front of the enemy's capital and on the following day repelled an attack by the Occitans at the bridge of Montaudran . They then devastated the fields and vineyards in the area, although they did not spare the rural population. The siege, however, ended after two weeks with a humble failure of the crusaders, who had nothing to offer against the heavily developed fortifications of the city. After there had been unrest and open quarrels among the knights as a result of supply shortages, supply trains had been regularly attacked by the Occitans, Montfort ordered the siege to be broken off on June 29th.

In order to raise the morale of his unsettled knights after this first major failure of the crusade, Montfort, taking full advantage of the forty-day successive period of the reinforcement troops, converted the retreat into another campaign of conquest. Knowing the Count of Foix in Toulouse, he marched straight south, took Autervie and crossed the Ariège to enter Pamiers. He then marched on directly to Foix via Varilhes, which was deserted by the population . He refrained from an extensive siege of the castle towering high above the city and instead devastated the surrounding area to inflict economic damage on the Count of Foix. He then took up the march north via Castelnaudary, during which several crusaders who had served their minimum combat time left him. After the destruction of Caylus Castle , he was able to move into Cahors without a fight , whose bishop had joined the crusade. De facto , Montfort was able to bring the entire Quercy under his control, where he immediately undertook a small pilgrimage to Rocamadour to the grave of the holy hermit Zacchaeus . Then he moved back to Pamiers, where he learned of new uprisings in the Lauragais and of a large campaign by the Count of Toulouse towards Castelnaudary. In fact, the Occitans had raised an army that outnumbered that of the Crusade, but was largely made up of communal militias. In Carcassonne, Montfort called all crusaders present in the region together and moved with them to Castelnaudary. Several cities such as Puylaurens, Les Cassès, Avignonet, Montferrand and Saverdun immediately seized the opportunity to drive away the thinned out crews. His numerical inferiority was able to make up for Montfort in Castelnaudary with his military skills. At Saint-Martin-Lalande he put the Count of Foix's troops to flight without his allies having supported him. Instead of fighting, the Count of Toulouse used a propaganda trick by announcing the capture and execution of Montfort, which in fact drove a large number of towns away from their Crusader garrisons and wiped out almost all of the year's military successes.

From Fanjeaux, Montfort resumed the recapture of the lost cities in the winter of 1211. This time he pursued a consistent strategy of isolation in order to cut off Toulouse from all cities and supply routes in the surrounding area. To this end, he carried out uninterrupted campaigns in the Lauragais, Aligeois, Quercy, Agenais, Périgord and Comminges, took one town after the other and even tried several times to raise the united Occitan army, which he always avoided. In April 1212, after a four-day siege, he captured the strong main pole in the Montagne Noire , which he had burned down. The following May he razed Saint-Michel-de-Lanès to the ground. The reinforcement troops that have been arriving continuously since spring 1212, including German knights under the Provost of Cologne , whose brother Adolf III. von Berg , Wilhelm III. by Jülich and Leopold VI. of Austria , made it possible for Montfort to recapture the entire Lauragais within a very short time. Then he moved to the Quercy, on the way to recapture Rabastens, Gaillac and Montégut. Then he moved in June 1212, the Agenais to once occupied by Richard the Lionheart built Penne that of a son of Raymond VI. was held, and to take Biron . At the same time, Robert Mauvoisin had conquered the nearby Marmande . After the Agenais had been secured at the end of July - the citizens of Agen had voluntarily submitted to the crusade - Montfort began the march into Toulouse in August 1212. After a three-week siege he took Moissac on September 8th , Castelsarrasin , Verdun and Montech surrendered without a fight. After the country north of Toulouse was completely brought back under his control, Montfort moved south and subjugated Pamiers from Saverdun and Auterive, thus re-establishing the ties between Foix and Toulouse. He then took the city of Muret in the Unterland des Comminges and devastated the Couserans in retaliation for the previous betrayal of his vice-count. With the capture of Samatan , Montfort had finally been able to complete the isolation of Toulouse.

The statutes of Pamiers

At the end of 1212, Simon de Montfort was the de facto ruler of the county of Toulouse and the regions associated with it, with the exception of the city of Toulouse itself as well as of Montauban and a few smaller villages. But Raymond VI was still de jure. the recognized Count of Toulouse, who despite his excommunication in constant contact with Pope Innocent III. stood, who urged a reconciliation of the count instead of his removal. Raymond VI. had gone to Aragón in the late year 1212 to win the support of King Peter II for his cause.

At the beginning of the winter months, Montfort had ordered the crusade army to his quarters and had taken quarters in the palace of Pamiers himself . There he gathered his leading officers and the clergy of Languedoc in a council, the first parliament since his election as leader of the crusades, which was to decide on the principles of the political order of his conquered territory. On December 1, 1212 he set his seal under the final document, the 46 articles of which laid down the customs, ordinances and statutes of the entire "Albigensian land" (terra albigensis) , which he called "his land". Even if he renounced the Tolosan title of count, he had made it clear that he also regarded himself as the lawful ruler of this principality and that the scope of his legal framework also extended over it. The statutes of Pamiers were inspired in many respects by the Assises of Jerusalem and thus had the character of colonial laws, in that a clear distinction was made between "born in France" (francigènes) and "natives" (indigènes) . Local knights were banned from carrying weapons for twenty years, while the new French landlords were obliged to use only French knights for military service during this time. Women of the local aristocracy, widows and heiresses could marry a Frenchman at will, but for a period of ten years without the express permission of Montfort not to marry a local noblewoman. This should of course guarantee control over the inheritance of land and the settlement of the French nobility.

Ten other statutes regulated the restoration of ecclesiastical authority, with the emphasis on the return of goods and privileges to the religious institutions that had been attacked by secular rulers in previous decades. Churches fortified by lay people had to be razed again. For this purpose, the exemption from taxes for the clergy was introduced and the reintroduction of the church tithe and the collection of annual interest in favor of the Holy See, which had already been undertaken in August 1209, was confirmed. According to the usual feudal law, interest was only due to secular seigneurism, but by crediting it to the Pope, Montfort had willingly made his principality an instrument of papal imperialism. The ulterior motive was that by letting the Pope share in the material gain of the conquests, one would ultimately corrupt him for Montfort's power politics; a trump card that should actually pay off later. Of course, the fight against the heretics was codified in the statutes, with the introduction of a general confiscation of property for all convicted Cathars. These, as well as Jews , were excluded from public office for all time, although converts were only allowed to take office again after ten years. All secular landlords were obliged to fight heretics and to support the church.

Furthermore, the statutes regulate the relationships between the classes of society, such as military and compulsory service, for the use of water, pastures and forests, for legal assistance for the poor, as well as the weight of bread and even the trade conditions for Prostitution were established. Particularly grave consequences should be the determination of the inheritance law, which is "to follow the customs of the Franconian region around Paris " (morem & usum Francie circa Parisius) and which have to apply to all social classes, regardless of whether they are native or immigrant. The old Occitan law, which was based on testamentary freedom and the division of inheritance in equal parts, was thus replaced by the northern French system, which was based primarily on the birthright . Of course, this should also make it easier for the French nobility to settle in Languedoc, but this principle should be overturned after three generations due to pressure from the descendants of the French.

Decision at Muret

In December 1212, Montfort had become the legislature of a country conquered by the sword. The only obstacles that stood in the way of his legal recognition were Count Raimund VI. of Toulouse and King Peter II of Aragón, who at around the same time formed a community of interests and developed a peace plan for Languedoc with which they wanted to win the Pope over to their cause. Relations with the King of Aragon had deteriorated considerably for Montfort in the previous year. Although he had received his recognition as Vice Count of Béziers-Carcassonne in the spring of 1211, the relationship was determined by mistrust, especially on the Aragonese side. An incident that occurred only shortly afterwards caused a rupture when, in June 1211, as a fulfillment of his military duty, Montfort sent 50 crusaders under Guy de Lucy to the Iberian peninsula to support the king in the fight against the Muslim Almohads . When Montfort was besieged only a few weeks later by a superior Occitan force in Castelnaudary, he had hurriedly ordered all his knights to come, including the Spanish contingent. Because it left the king's camp just at the moment when the Almohads were besieging the Salvatierra castle ( province of Ciudad Real ), this act was viewed by Peter II as an open betrayal, which was all the more serious when the Almohads were in September 1211 Salvatierra actually conquered. The king had come to the conclusion that Montfort was not to be trusted and that he had to be put in his place. Meanwhile, Pope Innocent III was of a similar opinion. who, in a letter of January 15, 1213 to Arnaud Amaury, confessed his bitter insight that he had lost the authority to interpret the crusade, that it had degenerated into a tool of a Montfortian policy of conquest and had lost sight of its original goal of fighting heretics . Addressing Montfort, the Pope wished his reconciliation with Peter II of Aragon so that both of them could unite their military forces against the Moors in Spain. To realize this idea, the Pope had adopted the Aragonese-Tolosan peace plan by limiting Montfort to the Trencavel lands that had already been granted to him and handing Toulouse to the heir of his count under the tutelage of King Peter II.

In his letters, the Pope had approved the peace plan and ordered the suspension of the crusade, but the letters were still on the way when the conflicting parties met at Lavaur that same month , probably at disposal , for a peace talks. At this point in time, the King of Aragón had become a Catholic hero through his victory over the Almohads on the "Plain of Tolosa" ( Las Navas de Tolosa , July 16, 1212) and thus became free to clarify the situation in Languedoc. But Montfort could rely on the support of the crusade legates and the Occitan clergy, who rejected the king's peace plan on January 18, 1213 across the board. In a letter to the Pope on January 21, 1213, they set out their motives, according to which the Count of Toulouse should not be trusted and the crusade must be continued in order not to lose what had been won so far. Rather, after the Moorish, the heretical Tolosa must now also be brought down, as Arnaud Amaury put it. Without waiting for a decision by the Pope, the conflicting parties resumed the fighting. On January 27, 1213, the Counts of Toulouse, Foix, Comminges and Béarn swore the feudal oath to the King of Aragón and thus made their domains subject to his protection. King Peter II had also reminded Montfort of his vassal duties towards him and asked him to withdraw from all areas not allowed to him. Montfort reacted to this with a formal revocation of his feudal oath, which he had taken in 1211, referring to the concerns of the crusade, which was more important than the regularities of secular feudal law. In fact, this was tantamount to betrayal and a declaration of war on the Aragonese king. "I will not fear a king who fights against the will of God for the favor of a courtesan", is Montfort's comment, alluding to the king's very free moral lifestyle at that time. On May 21, the Pope gave in to pressure from his legates and withdrew his support for the Aragonese peace plan and revoked the suspension of the crusade.

Neither Montfort nor his opponents had waited to receive this letter to begin their armaments. He had established his standing quarters in Muret and from there devastated the area around Toulouse. In June 1213 he returned to Castelnaudary, where he on the day of John the Baptist (June 24) the solemn knighting oldest, has become just thirteen years old son of his Amaury committed to "Knights of Christ" in the form of a religious consecration. Back to Muret he marched to Puicelsi , whose capture failed after a lengthy siege. The Occitans then went on the counter-offensive and captured Le Pujol (today Sainte-Foy-d'Aigrefeuille) on July 20th . It was increasingly bad for the Montfort cause when at the end of the month several reinforcement contingents marched back home after completing their minimum combat time. And after the news of the imminent arrival of the Aragonese army got around, several cities freed themselves from the understaffed crusader garrisons. Montfort undertook another diplomatic offensive in August to stop the march of King Peter II by reminding him of the papal letter of May 21, according to which the king should not recognize the feudal oath of the Count of Toulouse. As early as August 16, the king replied that he “always obeyed the orders of the Pontifex Maximus.” On August 28, the king crossed the Pyrenees with 1000 knights alone and set up camp in front of Muret on September 8 . Montfort was always informed of the movements of his opponent and did not begin his march to Muret until September 10th from Fanjeaux. He hadn't been able to muster more than about 1,000 mounted men, not all of whom were knights, and in order to be able to set up a halfway powerful infantry force, he had to thin out his crews in the cities. On the same day, the forces of the Occitan allies set out from Toulouse for Muret, which, in addition to their entire knighthood, also led the Tolosan city militia with them. On September 11th, Montfort moved into Boulbonne Abbey and made his will on the same day in Saverdun. On the morning of September 12th he entered Muret through a vacant gate. There were also seven bishops and three abbots in his entourage, although the crusade legate Arnaud Amaury was absent due to illness. The prelates were led instead by Bishop Fulko of Toulouse, who was no longer sure whether the numerical inferiority of the crusaders of their victory, therefore kept constant contact with the Occitan camp and pushed for a peaceful agreement. But when the Tolosan militia attacked the city walls of Muret on the morning of September 12th, Montfort forbade any further negotiation and had his army deployed to fight.

The crusaders were numerically clearly inferior to the enemy, no more than 2,000 of them opposed about 20,000 Confederates. Montfort's readiness to face this opponent in battle was already fatalistic , even suicidal. A retreat, however, would have destroyed his authority as the undisputed general, his meanwhile grown nimbus of the invincible and everything that had been won so far would have been seriously questioned in the face of the Occitan-Catalan army. So Montfort decided to accept the Battle of Muret, in which he was able to make up for his inferiority with his tactical genius, whereby a necessary portion of luck helped him to victory. He had his first two lines of battle for a direct frontal attack on the enemy, which, as expected, soon ran into trouble. But they retained the discipline and unity issued by Montfort, while the Occitan-Catalan knights gave up on the advantage of their superiority under the impression of their exuberant knight ethos in accepting duels. Nevertheless, the scales began to lean more in their favor, but instead of coming to the aid of his ranks, Montfort led a flank attack on Raimund VI with his third row after a wide left swing. carried out a reserve of the Occitans that remained in their position, so that they could no longer come to the aid of their main forces. In which King Peter II was in the front row of his knights and was finally killed there in a duel by Alain de Roucy . When word of his death got around, the Occitan-Catalan army broke up in a general and disorderly escape. Montfort then had his knights ride against the Tolosan militia, which had attacked Muret again during the battle, and had them slaughtered in a bloody slaughter.

Endangered triumph

The death of King Peter II brought Montfort a - apparently unexpected - complete victory, for the threatening power of Aragon was instantly shattered. The new king was not only a child, but was still part of the Montfort family . But instead of taking advantage of the general confusion, Montfort had resumed his policy of isolation against Toulouse, instead of invading victoriously the city that the count had previously left. Apparently he intended to seize this city only after the Pope had formally appointed him Count, under the impression of the victory of Muret. After devastating the county of Foix in October 1213, he marched into the Rhone Valley to subdue the rebellious Count of Valentinois and receive a reinforcement army. This had not happened without difficulty; Narbonne and Montpellier refused to allow him to enter, which only Nîmes granted after a threatening gesture. While he was busy clarifying the situation on the lower Rhône until the spring of 1214, there was another threat in the south from the Aragonese, who wanted to avenge the death of their king and free the young James I. The Pope was also upset about this and on January 23, 1214 even threatened Montfort with excommunication if he did not immediately hand the young king over to the custody of the papal legate. But first Montfort had to bring the Quercy back under control, where Raimund VI. had moved in and executed his apostate brother Baldwin. Meanwhile, in April 1214, a new Catalan army had entered Narbonne under Count Sanç , which was also joined by the Masters of the Hospitallers and Templars , who wanted to force the surrender of his great-nephew. Montfort went straight to the city via Carcassonne and besieged it. Before the situation could escalate further, the Legate Peter von Benevento appeared on site, to whom Montfort finally handed over the young King of Aragón. The legate also had the submission of the Counts of Foix and Comminges, as well as the city of Toulouse and Count Raymond VI, on behalf of the Pope. accepted, which should be under the protection of the Holy See until further notice.

Although Montfort had been cheated of his victory at Muret, he did not think of giving up. On May 5, 1214, he received the largest reinforcement army in Pézenas that had arrived from northern France since the beginning of the crusade. He owed this, among other things, to the new papal legate for France, Robert de Courçon , with whom he immediately got in touch and reached a mutual agreement. The legate had promised him the possession of all previous and future conquests. Already on May 3, 1214, Montfort had been able to expand his territory unexpectedly when the heavily indebted Bernard Aton VI. Trencavel transferred his vice counties of Agde and Nîmes. At the beginning of June, the marriage of Amaurys de Montfort to the daughter of the Dauphin of Vienne, which had already been agreed in December of the previous year, was carried out in Carcassonne, led by the preacher brother Dominikus de Guzmán . Then Montfort resumed his campaign, following the tried and tested isolation strategy. While his brother Guy was submitting the Quercy, Simon marched with a second army pillar into the Agenais, where he quickly regained control of several renegade cities, including Marmande. Casseneuil alone defended himself stubbornly for several weeks and was razed to the ground after his storm on August 18th and its population was massacred. In September, at the request of King Philip II of August, Montfort took over jurisdiction over the Abbey of Figeac , thus initiating his political rapprochement with the French king. In fact, Raimund VI had previously. held these judicial privileges. Then he moved to the Rouergue , where on November 7th, Count Heinrich I von Rodez took the oath of feud.

On December 6, 1214, Montfort had ended his campaign of conquest, with which he had brought the entire land of the Count of Toulouse under his control. Only the city of Toulouse itself remained to be taken to complete the conquest of the greatest Occitan principality. Montfort could rely on his - not wanted by the Pope - agreement with Robert de Courçon, whose background remains unclear. On January 8, 1215, he had called the entire Occitan clergy in Montpellier to a council that was supposed to decide on the political order of Languedoc. To Montfort's disadvantage, Courçon was not personally present at this council, which was instead chaired by Peter von Benevento. Montfort himself could not take part either, as the citizens of Montpellier had denied him access to their city, so that he had to take up quarters in a Templar house a few kilometers outside the walls and be kept informed about the progress of the talks. But the local clergy voted unanimously in his favor for the expropriation of Raymond VI, whose lands and titles were to be transferred to Simon de Montfort. However, Peter von Benevento vetoed this decision, who could appeal to a papal bull that had been received. The Raimund VI who traveled to Rome. had actually succeeded there in convincing the Pope to postpone Occitan affairs to the fourth Lateran Council convened for November 1215 . Montfort was not deterred by this downright disavowal and in the following months consolidated his de facto rule by taking over and buying several legal titles, such as the feudal lordship over Beaucaire and the Terre d'Argence . The arrival of the French Crown Prince Louis VIII at the head of a sizeable army of pilgrims, which he received in Vienne on April 20, turned out to be a stroke of luck .

With the prince at his side, Montfort was able to further consolidate his authority as the de facto sovereign by, among other things, forcing the Vice Count of Narbonne to pay homage to him. The vice-count was by right the vassal of the Duke of Narbonne - a legal title originally held by the Tolosan counts but usurped in 1212 by the crusade legate Arnaud Amaury, when he was elected Archbishop of Narbonne. But this led to the break of the former companions and ideological perpetrators, which Montfort now deepened even further when Prince Louis VIII, as the authorized representative of the church, ordered the demolition of the fortifications of Narbonne and Toulouse and in fact three weeks later the walls of Narbonne were torn down. The Tolosans, in turn, had bowed to the prince's authority and had to allow Guy de Montfort access to their city, who was supposed to supervise the demolition of their strong walls, which had to be carried out by the citizens themselves. In the first days of July 1215, Simon de Montfort was finally able to march into Toulouse as a follower of the prince and take possession of the city, which Raymond VI. had to leave in a hurry. He demonstratively moved into his quarters in the Count's Palace, the Château Narbonnais, which de facto concluded his takeover of the County of Toulouse . On July 8th, he took possession of Montauban, where Géraud V. took the oath of fief for the Armagnac , Fézensac and Fézensaguet . Shortly afterwards he said goodbye to the Crown Prince, whose forty-day “pilgrimage” was over, and then to Rome, also to his brother Guy and the Occitan clergy, led by Bishop Fulk of Toulouse, who were to represent him there at the fourth Lateran Council. Although his de jure status was not yet sealed, Montfort acted from now on as the real sovereign of Languedoc, sitting in court, resolving disputes, passing laws and receiving homage all over the country. Its establishment in the legal title of the expelled Raimund VI. he understood only as a formality that had to be done in Rome. There Pope Innocent III inclined. but first of all the matter of Raimunds VI. zu, who was unexpectedly supported by Arnaud Amaury. In addition, the Occitan princes present there raised regular charges against Montfort, who they accused of various offenses against secular and canon law and the unjustified spread of the war and the atrocities associated with it. The Occitan clergy, who were devoted to him, knew how to defend their cause against the fickle Pope. On November 30, 1215, in the final judgment of the council, the formal dismissal of Raymond VI. and the establishment of Simons de Montfort in all rights of a Count of Toulouse, who after six years of war had finally achieved his goal.

Count of Toulouse

According to the resolution of the Council, all land of the expropriated Raimundiners had been granted to Montfort, with the exception of the Agenais , which was to be handed over to the young Raimund VII as an inheritance from his mother, as well as the Provencal Mark, which was a fiefdom of the Holy Roman Empire and possibly also should be returned to Raimund VII. Montfort did not think of withdrawing his occupation troops from these areas, any more than the Raimundiner intended to begin their imposed exile. In the spring of 1216 they went ashore in Marseilles and heralded the battle to regain their principality. During this time, Montfort had to resolve his conflict with Arnaud Amaury, who also refused to recognize the council resolution that explicitly included the transfer of the Duchy of Narbonne to Simon de Montfort. Montfort marched to Narbonne at the beginning of March and forced his entry into the city after he had rudely pushed aside Arnaud Amaury, who had demonstratively stood in front of the city gate. Thereupon the archbishop pronounced the excommunication over Montfort, which was to be maintained as long as he was in the city. Soon tired of the conflict, Montfort moved to Toulouse a few days later, knowing that the judgment of the fourth Lateran spoke for him. The city leaders of Narbonne had also sworn allegiance to him. In Toulouse, on the other hand, the consulate and the notables swore allegiance to him and his son on March 8, 1216, whereupon he issued a guarantee of protection for body and property to all residents and the church. On this occasion he named himself for the first time in a document as "Count of Toulouse". Thereupon Montfort went back to northern France for the first time since the beginning of the crusade in order to obtain his sanctioning according to secular feudal law by King Philip II August. In April 1216 he offered this in Melun his conquests, the Duchy of Narbonne, the County of Toulouse and the Vice-Counties of Béziers and Carcassonne, in order to immediately receive them again as a fiefdom of the French king. For France, this act sanctioned a real conquest without its king ever having to do anything for it, since Carcassonne and Béziers had previously been fiefs of the Crown of Aragon. For his part, Montfort could now consider himself the rightful owner of his conquests according to all applicable laws of the medieval feudal order.

When Montfort arrived in Nîmes on June 5, 1216 , he learned of the capture of Beaucaire by the young Raimund VII, which heralded a general uprising of the Provencal Mark against the Crusader garrisons. He immediately moved outside the city himself to besiege it, but after two months of fierce fighting he had to pay tribute to the poor supply situation of his army and give up the siege on August 15th. Unrest in the south also required his presence in Toulousain. In September 1216 the Tolosans revolted against the French and Montfort had to retreat to the Château Narbonnais after a tough street fight. After he had exploited the mediation attempt by Bishop Fulkos to arrest some consuls, he ordered a general raid in which the city was looted by his men and the remaining masonry was destroyed. In general, Montfort now abolished the venerable Tolosan consulate in order to establish direct rule through a governor appointed by him. He then proceeded to consolidate his position as ruler by means of the Gascon clergy marriage of Countess Pétronille de Bigorre with their cousin Nuño Sánchez had to cancel them on November 6 in Tarbes with his younger son, Guy de Montfort to new marry. Nuno Sanches immediately occupied the castle of Lourdes , which Montfort immediately besieged, but quickly gave up again to appear as ruler in the Couserans and Comminges , although these territories were never granted to him. In January 1217 he moved against the Count of Foix, who had been reconciled from Rome, and besieged his son in Montgrenier , which he was able to take possession of on March 25 after his defenders had been granted free withdrawal.

In April 1217, Montfort's power in the south was largely consolidated, even if new sources of fire in the uprising opened up, which Raimund VI. were stoked from Catalonia. The conflict over Narbonne had unexpectedly become topical again when on March 7th the new Pope Honorius III. granted the ducal dignity to Archbishop Arnaud Amaury. But ultimately Montfort was able to maintain his rule over Narbonne, based on the judgment of the fourth Lateran, recognition by King Philip II and the loyalty of the vice count and consuls. Apart from this episode, he was on good terms with Honorius III. endeavored, who in two bulls of December 22nd, 1216 and January 21st, 1217 confirmed the regulations of the brotherhood of Dominic de Guzmán founded in Toulouse and finally recognized them as the new Catholic order of preachers. Throughout the entire time of the crusade, the Montfort family promoted the preaching activities of the Catalan monk and his converted followers through various donations, which at the same time represented their most lasting contribution to the fight against heretics, for the purpose of which the crusade was originally launched. After many years after Montfort's death the means of war had proven to be unsuitable for the destruction of heresy, the inquisition jurisdiction established by the Dominican order was to bring resounding success and to finally eliminate Catharism from the Languedoc.

In May 1217, Montfort and his army left Toulouse to subjugate the Provencal Mark, which was now almost completely controlled by the Raimundines; he should never enter the city again. After a short train through the Termenès with the submission of Montgaillard and Peyrepertuse , he reached Bernis , which he razed to the ground and whose master he left hanging. This example quickly had an impact when almost all castles and towns on the right bank of the Rhône with the exception of Beaucaire and Saint-Gilles submitted to it voluntarily. On July 14th, he moved into Pont-Saint-Esprit , where the landlord of the strategically important city of Alès , Raymond Pelet, submitted to him. Here he also took that of Honorius III. newly appointed cardinal legate Bertrand, who brought him the unequivocal order of the Pope to work towards a peaceful solution and to bring the mighty Count of Valentinois back into the bosom of the Church. Montfort immediately turned against him, crossed the Rhône in Viviers , took Montélimar and besieged Crest . After devastating the surrounding area at the same time, the count announced his readiness to negotiate and, while the discussions were being held, he received a letter from his wife from Toulouse on September 15th. In order to keep up the pressure on the Count of Valentinois to negotiate, Montfort had kept the addressee of the embassy a secret until the Count declared his submission and handed over three castles as security. In fact, the letter contained nothing more than news of the return of Raymond VI. from Aragón at the head of an Occitan army and its entry into Toulouse without a fight on September 13, 1217. The rule of Montfort over the capital of Languedoc came to an end on this day, in a popular uprising the French occupation troops were massacred, some of which are still standing to the Château Narbonnais.

death

Montfort first moved to Baziège to summon all available knights and mercenaries with whom he marched off Toulouse in October 1217. As with Muret four years earlier, he was again ready to put everything on one card, because his army was nowhere near big enough to be able to completely enclose the city. Due to the season, it was once again thinned out in terms of personnel, which is why Alix de Montfort immediately after the return of Raymond VI. had set out for northern France to recruit a reinforcement army there. In the meantime, however, Montfort had to get by in front of the city walls with its available troops, which had been hastily rebuilt by the population in just a few weeks and behind which the largest Occitan army that was ever raised in this crusade stood ready for defense. Immediately after his arrival, Montfort took the suburb of Saint-Michel, which enabled him to move back into the Château Narbonnais. In order to prevent access to the Cité from the east as well, he then wanted to cordon off the two city bridges over the Garonne and therefore bring the suburb of Saint-Cyprien under his control. However, this failed due to a failure of the Count of Foix, from which he had to back down. Of necessity, Montfort had to prepare for a siege, which was uneventful until next spring due to the chronic shortage of personnel, supply bottlenecks and the wintry weather.

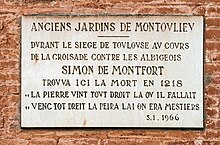

Open fighting did not begin until April 15, 1218, with the defenders not only limited to passive defense, but also deployed attacks that led to clashes in the open field. At the beginning of May Alix had returned with considerable reinforcement troops with whom Montfort was able to take Saint-Cyprien immediately, which however turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory , since a sudden flood swept away the Garonne bridges and this access to the city had become obsolete. Then he had to apply all of his siege art to the city wall and build machines with technical sophistication that were able to break through them. On June 7th, the young Raymond VII was able to enter Toulouse with a strong Provencal troop, much to the discouragement of the besiegers. After some northern French barons - who had moved to the Languedoc in the belief that they were fighting heretics - had expressed their unwillingness to have to besiege a Christian city in order to take away its rightful master, Montfort had given himself another month to deal with them to be able to conquer. Otherwise he would call off the siege. On the morning of June 24th he had given the order to attack with all men and machines, but fighting into the night the French could not force a decision. On the morning of the following day, June 25, the defenders responded with all their might with a sortie on the Crusader camp. Standing at the head of his men, Montfort threw himself into a fight which, as with Muret, was tantamount to a suicidal undertaking because of its numerical inferiority. According to the tradition of the Pierres des Vaux-de-Cernay , Montfort is said to have been aware of this fact when he addressed his companions with his last words: "Let us now go out and die for him who died for us." But in the hard-fought battle the Crusaders got the upper hand and pushed the Occitans back to the city wall at the gate of Montoulieu, where Guy de Montfort was shot with an arrow from his horse. Simon fought his way to his brother in order to rescue him from the field of fire of the opposing archers positioned on the wall, when a bullet hit him on the helmet. The Canso de la Crosada for the catapult from which the bullet was fired, served by Tolosan women and girls and their stone shall be descended at the place where he should go down was. Simon de Montfort's skull was shattered; he was dead instantly.

The next day the French crusaders and barons Amaury de Montfort paid homage as their new leader and heir to all his father's titles and domains. He had intended to continue the siege, but the knights, discouraged by the death of their long-time leader, had nothing left to do against the defenders. The cardinal legate Bertrand who was present finally decided on July 25th to lift the siege and to retreat to Carcassonne. Simon's body was carried there in a leather sack and buried in the Saint-Nazaire cathedral. After his son had to sign the surrender of the crusade proclaimed in 1208 in front of this city on January 14, 1224 and had to give up all Montfort conquests in Languedoc, he had his father's body transferred to the Abbey of Hautes-Bruyères , the traditional burial place of the House of Montfort.

judgment

As the military leader of the Albigensian Crusade and its main beneficiary, Simon de Montfort was and is one of the most controversial figures in medieval history in Western Europe. Problematic are the descriptions of the sources as well as the secondary literature, which again and again tend to tendentious stylizations of his person, either as a hero or a villain. In the Catholic historiography, starting with his "house chronicler" Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay , he has entered as a martyr who himself as an exemplary crusader (miles Christi) , filled with all the virtues of Christian chivalry and full of humility and wisdom in the Service of God to fight against the enemies of faith. Among the people who knew him, he was known for his simple manners as well as for his strict piety; At any time of the day or night he observed the prayer rules, as he was recognized for his righteousness, which he demonstrated most clearly in 1203 before Zara. He was admired for his straightforward and familiar way of life, which was often used as a counter-example to that of the Count of Toulouse.

Montfort's piety was undoubtedly militant in the ethos of his social class; he was not the only knight who felt called to take the cross twice in his life. His opponents recognized in this piety, of course, a mask of his ambition to conquer a foreign principality, and piety alone is certainly not a sufficient motive to explain his long-term and risky struggle, which he waged with all physical and mental resistance. He spent the entire last decade of his old age in the saddle. In doing so, he identified himself completely with his mission and, by setting an example, was able to persuade his followers to undertake the most dangerous efforts against a numerical superiority. He was able to successfully end 33 of 39 sieges and no less than 48 permanent places ( castra ) surrendered to him without a fight. His motivation skills and his military genius made him one of the best generals of his time, although he was often favored by the incompetence of his opponents. But supposedly even Raymond VII of Toulouse is said to have admired the leadership ability and strength of faith of his long-standing enemy. The majority of his opponents saw his courage only as an excuse for cruelty, and for them his righteousness was an alibi for his fanaticism. In fact, he was not picky about the means typical of medieval warfare, above all, he was not only familiar with the sword but also with terror as a weapon. Convinced that the law was on his side, he could safely be capable of atrocities, which, however, were also committed by his opponents, albeit to a lesser extent. Beloved on the Catholic side this filled with joy, but with Occitan poets and chroniclers it aroused horror, bitterness and sadness. For them he was a monster, for whom his virtues played no role when it came to murder, manslaughter, pillage, looting or the expropriation of property belonging to others. He deprived her of the victory of paratges (Occitan for prestige, honor) and destroyed the social order of her homeland that was based on it, so that even the Catholic Occitan Guillaume de Puylaurens later spread the horrors of war “from the Mediterranean Sea, for which Montfort was responsible to the British Sea ”.

The work of Montfort cannot be explained without reference to the political backing that he could be sure of all along. Just like the disinterest of King Philip II of France , which gave him military and political freedom of action, he could rely on the agreement of the papal legates, above all Arnaud Amaury and Robert de Courçon , who had all their influence on the fickle Pope Innocent III. spent to keep the crusade going. The motivation of these people to do so, who often appeared in direct contradiction to papal dogmatics, is insufficiently evident from the traditional sources. As decision-makers on the spot, they probably came to the conclusion that only a secular prince in Occitania who was weighed in favor of the Catholic cause could guarantee success in the fight against heresy, for which Raimund VI, branded as a friend of the Cathars, could consequently. had to be eliminated. As for the fight against heresy, the real purpose of the crusade, the actions of Montfort are contradictory. He was certainly convinced of its necessity, and with the mass burnings of Minerve in 1210 and Lavaur and Les Cassès in 1211 he had his will to do so too clearly demonstrated. However, these three spectacular examples remained the only executions on the Cathars to be recorded in his aegis. Otherwise, his religious struggle was limited to the material expropriation of convicted heretics and their supporters as well as the promotion of the preaching mission, namely the brotherhood of Dominikus de Guzmán , which had received recognition as a Catholic order during his lifetime. After Montfort's death it turned out that the means of war to combat an attitude of belief proved to be ineffective. The crusade could not seriously endanger the Catholic Church, neither in terms of its institutional structure nor in terms of its social foundation. But ten more war years had to follow before those responsible came to this conclusion.

Regardless of the actual goals of the crusade, Montfort's work was of outstanding influence on the further history of France, its Occitan south and for Aragón. His victory at Muret became a fateful moment in French history, which abruptly pushed the power of Aragon, which had grown over the generations in what is now Languedoc, back to the south of the Pyrenees . The formerly powerful, almost independent principality of Toulouse was so permanently weakened by its war that it could no longer oppose the crusade of King Louis VIII carried out in 1226 , making Montfort a forerunner of the French royal power, which was ultimately the main beneficiary of the Albigensian crusade after it At the end of 1229 he knew how to fill the power vacuum that had developed. Based on Montfort's administrative and legislative preparatory work (statutes of Pamiers), the French crown was able to establish a stable regime over the country within a very short time. In general, it should be mentioned in this context that Montfort's style of government was based on the northern French model of King Philip II August , which was the trend-setting example of his time . He gave only a few fiefs from his conquests, usually only to long-standing, deserving confidants. Otherwise, however, he intended to govern the country by means of a centralized governor system in the style of an absolute sovereign. The French crown only had to insert this system into its administration in 1229 to establish its authority in the Languedoc. For Aragón, Montfort's triumphal march marked the end of his efforts to establish a Midi Kingdom or Pyrenees Empire (imperi pirinenc) from Catalonia to Provence. Instead, the kingdom shifted its expansion to the Mediterranean under his “foster son” James I the Conqueror and became its dominant power in the Middle Ages.

The direct profit to be booked for the Montfort family from the Albigensian Crusade was very modest. The Peace of Paris in 1229 only confirmed the comparatively small Seigneurie Castres for the heirs of Guys de Montfort , who had already received them from his brother's hands. Otherwise, Amaury de Montfort's abandonment of the legal title accumulated by Simon during the war to the French crown made it his immediate heir, as the Trencavel lands could be directly united with the crown domain in 1229 . The county of Toulouse, however, was left with its original owner, albeit greatly reduced in size, which resulted in a late defeat for Simon's years of struggle for this principality. In addition to his own death, the Albigensian Crusade demanded a heavy toll in blood from his family; In 1220 his son Guy was killed in the battle for Castelnaudary, and in 1228 his brother Guy, for whom he had sacrificed himself before Toulouse, fell. After the Albigensian Crusade, the Montforts sank back into the rank of the subordinate French feudal nobility. Only the third son of the crusade leader of the same name achieved the highest historical reputation in England and immortalized the name Montfort there in the founding history of British parliamentarism .

literature

- Malcolm Barber: The Cathars. Heretic of the Middle Ages. Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Düsseldorf and Zurich 2003. (English first edition: The Cathars. Dualist heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow 2000).

- Rebecca Rist: The Papacy and Crusading in Europe, 1198-1245. New York 2009.

- Michel Roquebert: Simon de Montfort, Bourreau et martyr. Librairie Académique Perrin, 2005.

- Michel Roquebert: The History of the Cathars, Heresy, Crusade and Inquisition in Languedoc. German translation by Ursula Blank-Sangmeister, Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart 2012. (French first edition Histoire des Cathares. Hérésie, Croisade, Inquisition du XIe au XIVe siècle. Éditions Perrin, Paris 1999).

- Jörg Oberste : The crusade against the Albigensians. Heresy and Power Politics in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2003.

- Christine Woehl: Volo vincere cum meis vel occumbere cum eisdem: Studies on Simon von Montfort and his northern French followers during the Albigensian Crusade. 2001.

swell

The unofficial crusade writer Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay wrote a quasi-biography of Simon de Montfort with his detailed work. His naturally one-sided and glorifying report concludes with events in 1219. Furthermore, the cleric and poet Guillaume de Tudela stayed in the crusade camp, since 1211 in the entourage of Baldwin of Toulouse, who wrote the first part of the Chanson de la Croisade , written in old French , and who, despite his partiality, renounced a pointed polemic. For unknown reasons, he broke off his work in the spring of 1213, which, however, was soon continued by an anonymous Occitan poet, probably a follower of the Count of Toulouse. This continuation, written in Occitan ( Canso de la Crosada ), describes with patriotic zeal the point of view and the struggle of the Occitans against Montfort and the crusade. It also ends in 1219. Guillaume de Puylaurens describes the crusade in his chronicle from a longer period of time . Although himself a Catholic cleric and advocate of the fight against heretics, as a native Occitan he was critical of Montfort's actions and the effects of the crusade on the political order and culture of his homeland.

- Pierre des Vaux-de-Cernay = Petri, Vallium Sarnaii Monachi, Historia Albigensium et sacri belli in eos suscepti. In: Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France . Vol. 19 (1880), pp. 1-113.

- Guillaume de Puylaurens = Guillelmi de Podio Laurentii Historia Albigensium. In: Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France. Vol. 19 (1880), pp. 193-225.

- Guillaume de Puylaurens = Historiae Albigensium auctore Guillelmo de Podio Laurentii. In: Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France. Vol. 20 (1840), pp. 764-776.

- Chanson de la Croisade (Canso de la Crosada) . = La chanson de la croisade conte les Albigeois. Ed. By Paul Mayer, Vol. 1 ( Guillaume de Tudela ), 1875; Vol. 2 (Anonymous), 1879.

Remarks

- ↑ This genealogical error has continued into more recent publications, such as Roquebert, p. 136.

- ↑ a b Both Amaury VII. And Guy de Montfort were born in or shortly before 1199, as both were first mentioned in a donation to the leprosy hospital of Grand-Beaulieu near Chartres that year. See Cartulaire de l'Abbaye de Notre-Dame des Vaux de Cernay. Vol. 1, ed. by Lucien Victor C. Merlet and Auguste Moutié (1857), p. 71, note 1.

- ↑ a b Both Simon the Younger and Robert de Montfort are mentioned for the first time in a deed of donation issued by their mother in June 1218 in front of Toulouse in memory of their father to the Abbey of Notre-Dame du Val with their older brothers. In Robert's case, this is his only mention, he must have died as a child. Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 160.

- ↑ Gerard de Fracheto: Vitae fratrum Ordinis Praedicatorum necnon Cronica ordinis from anno MCCIII usque ad MCCLIV. Edited by Benedictus Maria Reichert in Monumenta Ordinis Fratrum Praedicatorum Historica. Vol. 1 (1846), p. 322.

- ↑ Roquebert, 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Alberich von Trois-Fontaines : Chronica. Edited by Georg Heinrich Pertz in Monumenta Germaniae Historica SS. 23 (1874), p. 941.

- ↑ MF-I. Darsy: Picquigny et ses seigneurs, Vidames d'Amiens. (1860), p. 35. The will of Laure de Montfort from 1227 is deposited in the register of deeds of the Abbey of Le Gard .

- ↑ Simon de Montfort enjoyed such prominence as an opponent of Johann Ohneland that, according to rumors from 1210, he was the preferred candidate of the revolting English barons for the royal throne, provided that Johann Ohneland had been successfully overthrown from it. Annales Monastici de Dunstaplia et Bermundeseia. Edited by Henry R. Luard in: Rolls Series. 36, Vol. 3 (1866), p. 33.

- ^ Levi Fox: The Honor and Earldom of Leicester: Origin and Descent, 1066-1399. In: The English Historical Review. Vol. 54 (1939), pp. 385-402. The Beaumont inheritance was transferred to the Earl of Chester in 1220 for lifelong usufruct, although the rights to the county of Leicester remained with the Montforts. In 1231 it was finally given to the younger Simon.

- ↑ Here called Simon comes Montifortis . Layettes du Trésor des Chartes. Vol. 1, ed. by Alexandre Teulet (1863), no. 438, pp. 185-186 = Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 2.

- ^ Gottfried von Villehardouin : Chronique de la conquête de Constantinople, par les Francs. Edited by JA Buchon in Collection des Chroniques nationales françaises. Vol. 3 (1828), p. 3.

- ^ Gottfried von Villehardouin: Chronique de la conquête de Constantinople, par les Francs. Edited by JA Buchon in: Collection des Chroniques nationales françaises. Vol. 3 (1828), p. 43. L'Estoire de Eracles empereur. Liv. 28, cap. IV in Recueil des historiens des croisades . (1859), Historiens Occidentaux II, p. 255.

- ↑ Here called Simon dominus Montisfortis . Layettes du Trésor des Chartes. Vol. 1, ed. by Alexandre Teulet (1863), No. 815, p. 307 = Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 15.

- ^ Letter of November 17, 1207 to the King of France and the barons of northern France with the invitation to take the cross: Innocentii III Registrorum sive Epistolarum. Edited by Jacques Paul Migne in Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina. Vol. 215, Col. 1246-1247.

- ^ Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 29.

- ↑ Laurence Marvin: Thirty-Nine Days and a Wake-up: The Impact of the Indulgence and Forty Days Service on the Albigensian Crusade, 1209-1218. In: The Historian. A Journal of History. Vol. 65 (2002), pp. 75-94.

- ^ Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 29a.

- ^ Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 30. Amaury de Montfort ceded co-rule in Pamiers to Louis VIII in October 1226. Histoire générale de Languedoc (preuves). Vol. 5, ed. by C. Devic and J. Vaissete (1842), No. 139, p. 645.

- ^ Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 32a. Simon de Montfort was recognized by the papal side as Vice Count of Albi in June 1210. Innocentii III Registrorum sive Epistolarum. Edited by Jacques Paul Migne in Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina. Vol. 216, Col. 282-283.

- ^ Catalog des actes de Simon et d'Amaury de Montfort. Edited by August Molinier in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 34 (1873), No. 35-36.