Theremin

The Theremin (also: Thereminvox , Thereminovox , Termenvox , originally Aetherophon ) is an electronic musical instrument invented in 1920 . It is the only widespread musical instrument that is played without contact and directly generates sounds. Its name goes back to the inventor, the Russian Lev Termen , who called himself Leon Theremin in the USA .

In the Theremin, the electrical capacity of the human body influences an electrical field . The position of the hands in relation to two electrodes ("antennas") controls the strength of the change. The changing oscillation of the field is amplified and output as a sound through a loudspeaker. Although the theremin pioneered instrument making in many ways , its use remained limited to musical niches. It was used in fields as diverse as new music , science fiction films, and experimental pop music . It has only been popularized somewhat since the 1990s.

The theremin played a special role in music history through the instrument maker Robert Moog . In his youth he built Theremine and used the experience he gained there to develop the first synthesizer .

Style of play

The Theremin is played without contact by the distance between both hands and two antennas, with one hand changing the pitch and the other changing the volume. Right-handers usually influence the pitch with the right hand and the volume with the left. With a standard theremin, the player has no visual or haptic feedback about his playing style and has to rely solely on his hearing. The area of influence on the pitch is around 40 to 50 centimeters around the antenna, which means that the player's arm and body can also influence the sound.

The inventor Lew Termen attached great importance to the fact that the instrument allowed an infinitely fine variation of the notes produced without the interpreter being hindered by mechanical restrictions. For terms, this means a finer variation in pitch and volume than was possible with many mechanical instruments, but also, for example, the ability to hold a tone as long as desired. In addition, the tone of the theremin can be continuously changed over a wide frequency range without having to change the strings (such as the violin ) or the number of standing waves (such as the trombone ).

Due to the functional principle, a continuous change in pitch ( glissando ) is possible. The theremin is therefore not limited to scales and is also very suitable for generating vibrati . However, playing individual, clearly distinguishable notes is difficult. In addition, the entire rest of the body must be kept still. The tone color can be changed using buttons. Since the theremin only gives acoustic feedback, the exact positions for sound generation change over time and it is actually not physically possible to play individual tones, the theremin has proven to be an instrument that is relatively easy to learn over the years, but only is very difficult to master at a high level.

Clara Rockmore and, based on this, Lydia Kavina developed a special finger technique that enables Theremin to be played largely glissando-free. This essentially only changes the position of the fingers, while the hand and arm remain in one place. In 2006, the German thereminist Carolina Eyck developed a playing technique with eight finger positions, whereby the electromagnetic field is applied to the length of a hand, which is an octave.

Since its inception, the theremin has been a popular instrument for performances, as it was also visually spectacular. The generation of sounds “from the air” gives the instrument an aura of the extraordinary.

The sound of the theremin reminds some of a fragile female voice, but generally sounds significantly different from other instruments. Listeners and reviewers often describe it as fragile, otherworldly, eerie, or ghostly. As a monophonic instrument, it is particularly suitable for taking on a melody voice . In its early days, the theremin repertoire consisted largely of adapted pieces for violin or cello .

functionality

Theremine work on the principle of a capacitive distance sensor. The player's hand, which functions as grounding through its own mass , changes the LC resonant circuit of an oscillator via the respective electrode ("antenna") : It influences both the frequency and the quality of the resonant circuit by increasing the capacitive component of the resonant circuit and its damping influences.

Even in the first devices, the resonant circuit was formed from a coil and a capacitor connected in parallel . Since the changes in capacitance possible via the antennas are very small - they are in the picofarad range - the fundamental frequency of the resonant circuit must be well above the audible range in order to generate a significant change in frequency. In the first examples 500 kHz was chosen, a range for the basic frequency from 100 kHz to 1 MHz is typical. With these high frequencies, it is far beyond what humans can perceive acoustically. In order to make these frequency changes audible, the signal from the oscillator circuit connected to the antenna is mixed with the output signal from another oscillator with a fixed frequency. The mixture creates sum and difference frequencies; the audible tone is the difference frequency between the variable and fixed-frequency oscillating circuit. The downstream amplifier amplifies the difference frequency and makes it audible through a loudspeaker.

In order to be able to control the volume, the frequency of a third oscillator is converted into a voltage . The closer the player gets to the antenna, the lower the frequency of the oscillator and the voltage used as a control variable for the volume.

In the original version the theremin was equipped with tube oscillators ; a tetrode was used to generate the difference frequency. Modern Theremines often work with smaller transistor oscillators that can be less influenced by the environment . According to Termen, Robert Moog in particular further developed the instrument, also in variants as a kit. Building instructions appeared in magazines and electronic books.

Termen's original theremin played almost pure sine tones . Later it added sideband frequencies to terms , which allow a richer timbre by connecting several pairs of oscillators in parallel. Termen's original instrument played in a range of about five octaves . It was able to generate vibrations between 0 and 2000 Hertz , but it can be assumed that frequencies down to 60 Hz can only be reproduced by the loudspeaker.

Newer experimental theremins since the 1980s are able to process movement in three dimensions and not just two dimensions. Since the 1990s there have also been Theremines with data outputs that can be connected to software and computers , which enhances their musical expression.

history

The theremin has been a spectacular novelty since the 1920s. While his followers saw in him a serious instrument, it could celebrate the greatest successes on show stages. The composers who composed for the theremin included Percy Grainger ( Free Music in graphic notation), Joseph Schillinger , Bohuslav Martinů and Edgar Varèse . With the disappearance of its inventor Lew Termen, who was imprisoned in the Soviet Union for several decades from 1938 , musicians and composers largely lost interest in the instrument. In the 1950s it was able to conquer niches in film music and among hobbyists. Pop bands started using it in the 1960s. In pop, however, the theremin was replaced by the much more versatile synthesizer after just a few years . Only with glasnost , the reappearance of Lew terms, the widespread use of electronic music and the urge for performativity in electronic music did the theremin experience a renaissance since 1990. Since then, the theremin has been more widespread than ever before, but never got beyond a niche existence.

Prehistory, invention and first presentation

The invention of the theremin came at a time when various engineers and musicians were beginning to use electricity to generate sound. In 1837 a Dr. Page from Massachusetts found a doorbell that made tones using a magnet and a coil of copper wire. Thaddeus Cahill's electromechanical telharmonium from the 1890s required two players, took up a whole room and had to be transported in several freight wagons. The invention of the vacuum tube made it possible for the first time to build such instruments with a size and weight that a person could handle. Cinema organs used since the early 20th century electricity as an aid to sound generation, which is also played with a keyboard Audion Piano by Lee De Forest was technically a direct precursor of the theremin.

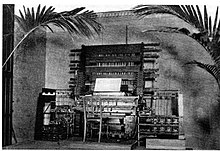

The theremin was invented in 1919 by the Russian physics professor Lev Sergejewitsch Termen, who later called himself Leon Theremin in the West . At the time, Termen was conducting physical and electronic experiments at the Petrograd Physical-Technical Institute and collaborating with engineers at the Moscow State Institute of Musicology. It was first shown in 1920 in Petrograd at the Physikalisch-Technische Institut. The Theremin was presented to the public in Moscow in 1921 at the 8th All-Soviet Electrotechnical Congress. The instrument he called Aeterophon there generated the pitch by hand movements in the air, but he still controlled the volume with a pedal. In contrast to the other electrical musical instruments of the time, Termen did not rely on a keyboard for operation, but on a new type of interaction with the hands in the air. By 1923, Termen had developed his instrument to such an extent that the volume could also be controlled with a hand movement in the air; he himself now called it Thereminvox. While early models still worked via headphones or funnels, the technology was so advanced in the mid-1920s that speakers could also be connected. Since 1929 the theremin had four instead of three octaves.

During these years in Russia, Termen developed other instruments that combined music with colors, light or smells. Instruments similar to the theremin, which were based on traditional instruments in their handling, were the Trautonium from 1930, as well as a purely electrical device like the Ondes Martenot from 1923. In 1914 the Italian futurist Luigi Russolo developed several dozen (partly electro) mechanical synthesizers who have favourited intonarumori . In particular, the Ondes Martenot, which can be played with a keyboard, were often used as a replacement for the theremin in the following decades, as they are easier to play and available in larger numbers. The Dynaphone , developed by Edgar Varèses close friend René Bertrand , dates from 1927 . As early as 1929, an "Aetherophon" was manufactured in Germany by the Koch & Sterzel company in Leipzig , but it probably had a pedal control for the volume. It was also during this period that Jörg Mager developed the Sphärophon , which during the National Socialist era was inglorious in denouncing the Theremin as "Jewish".

Early years

The instrument initially met with enthusiastic reception. It seemed to embody progress and the future. Lenin was enthusiastic. After Termen himself, the violinist Konstantin Kowalski began to play the instrument regularly, performing both classical repertoire and specially composed pieces. Terms, the instrument and the musical prodigy Clara Rockmore traveled as ambassadors of socialist progress through Europe, where they fascinated the concert audience. After several years of trying in vain for a patent in Western Europe, Termen managed to get one after a show trip to the USA. Rockmore, who was also referred to as the "High Priestess of the Theremin", staged her appearances as séancelike events in which she played a comparatively conventional program with great virtuosity (works by Stravinsky , Ravel , Tchaikovsky ).

Lew Termen demonstrated his device for the first time in Germany in 1927 and then traveled to the USA, where he found wealthy patrons and received a patent for the Theremin in 1928 . In 1928, RCA built a 3½-octave theremin based on vacuum tubes in large numbers and wanted to conquer a mass market with it. The several thousand copies that RCA and licensees built in the late 1920s were marketed as easy-to-play instruments for the whole family. This attempt was unsuccessful; RCA only sold around 500 copies in total. The “Aetherwelle Music” of the “Original Prof. Theremin Ensemble” with W. Kalecky, A. Lubin and Martin Taubmann had very popular music examples at the demonstrable performances in Germany and Switzerland due to the skillful presentation with an introductory lecture (in particular from operas and folk songs) and the subsequent invitation to the audience to try the game themselves and gained greater prominence through radio reports.

While in Leningrad classical composers were already occupied with the theremin in the 1920s, the breakthrough in international music came with Joseph Schillinger's First Airphonic Suite , which was premiered in Ohio in 1929 . Other composers followed: Henry Cowell , Edgar Varèse ( Ecuatorial ), Percy Grainger and Leopold Stokowski wrote pieces for the theremin, with the Australian Grainger justifying his choice in the Statement for Free Music by saying that it was absurd to live in the age of flying and still being musically bound to notes and tones. With the theremin he wanted to overcome the limitations of classical instruments. Others hoped to see the start of a development in the theremin that would ultimately make musicians and their influence on the rendering of a composition disappear and leave the pure composition. While Rockmore was able to fill with their virtuosity concert halls, especially the interpreter prescribed Lucie Bigelow Rosen of New Music . Despite her less virtuoso mastery of the instrument (apart from a recently discovered pop single, her recordings are kept under lock and key by the heirs), according to contemporary sources, she was the second great virtuoso of the instrument alongside Rockmore because of her lively advertising and concert activities. Through her marriage to the banker Walter Rosen, she was endowed with financial means, and as an organizer and mentor she took care of new music in general and Lew Termen in particular. Bigelow Rosen commissioned Bohuslav Martinů and Joseph Achron , among others , to write works for them and the theremin.

The instrument made its last major appearance in 1932. That year, the Paris Opera had to call the police to cope with the crowds who wanted to see a Theremin performance. In the USA, Termen tried to remedy the dwindling enthusiasm for the instrument with a Theremin Electrical Symphony , in which a total of 16 theremins and related instruments performed in New York's Carnegie Hall .

In Nazi Germany, the theremin was regarded as a “Jewish instrument”, among other things because the company M. J. Goldberg und Sons, run by Jews, looked after Lew Termen's interests in Germany. Nevertheless, in the year of the Olympic Games in 1936, the instrument made a public appearance. The Völkischer Beobachter was enthusiastic about a demonstration in Munich. Bigelow-Rosen was only able to perform this year at the Olympic Games in Germany, since the Germans would otherwise not have given the woman, who was married to the Jewish banker Walter Rosen, a performance permit. Aesthetically, too, the theremin did not fit into the cultural policy of the time; What followers described as supernatural and spherical, classified the Nazi cultural policy as unnatural and distorted.

Despite this early enthusiasm, the instrument failed to gain acceptance among the general public. Contrary to initial hopes, the theremin turned out to be extremely difficult to play, the musical mastery of which required a high level of virtuosity. In the early 1930s, enthusiasm for the instrument waned. The economic crisis in the USA and World War II prevented the innovation from spreading widely. Termen disappeared from the USA under mysterious circumstances in 1938, only to reappear a little later in the Soviet camp system. In the Soviet Union, an increasingly anti-avant-garde cultural policy prevented occupation with the instrument and its use remained primarily limited to a few niches for the next few decades. Many compositions, and especially the pieces listed, barely knew how to make use of the possibilities of the instrument; the performances were mainly pieces that could easily have been played with a violin or cello.

John Cage , who had a strong influence on avant-garde electronic music for the following decades, deliberately refrained from using the theremin. As he wrote in his Credo of 1937, the thereminists had already destroyed the musically revolutionary possibilities of the theremin by one-sided use of a classical and traditional repertoire , so that Cage relied on electronic devices for his pieces that had not been designed as musical instruments:

“Theremin provided an instrument with genuively new possibilities, Theremenists did their utmost to make the instrument sound like some old instrument, giving it a sickingly sweet vibrato, and performing upon it, with difficulty, masterworks from the past […] Thereminists act as censors , giving the public those sounds they think the public will like "

In 1965, however, Cage was at Robert Moog (the terpsitone similar) theremins for his composition Variations V in order. These were operated by dancers on the stage through their movement and in this way regulated the control of tape recorders in the orchestra pit.

Science fiction film score

The theremin was and is used in a variety of ways. In addition to the compositions especially for the theremin, it was often used for film music, for example for the first time in 1931 by Dmitri Shostakovich for the Soviet film Odna - Alone and by Gavriil Popow for the documentary Komsomol - Förderer der Elektrizität (1932), in which Kowalski did the Theremin was playing.

After the enthusiasm for the theremin as a concert music instrument waned due to the Second World War, a new popular purpose began to establish itself in 1945: as a producer of eerie music and musical effects that make goosebumps in haunted and science fiction films. The theremin had already made a few appearances in pre-war films, for example in King Kong and the White Woman (1933) or Frankenstein's Bride (1935), but only played a supporting role in these soundtracks .

In Hollywood , the theremin was used especially for the representation of extraordinary psychological and supernatural states. The first to concisely the instrument and audibly began, was the composer Miklos Rozsa in The Lost Weekend (The Lost Weekend) by Billy Wilder and in the Oscar-winning score for Spellbound (Spellbound) by Alfred Hitchcock emerged, both in 1945 . The doctor and thereminist Samuel Hoffman was responsible as a soloist for the interpretation of these two soundtracks as well as for almost all subsequent science fiction soundtracks . In particular, the album Music Out of the Moon , published by Hoffman, reached hundreds of thousands of listeners and years later flew to the moon with Apollo 11 . The theremin was particularly prominent as a solo instrument with the science fiction films of the 1950s. In The Thing from Another World , from 1951, the theremin stands for the eerie and possibly threatening aliens. Bernard Herrmann's soundtrack for The Day on which the Earth stood still is stylistically based on a soundtrack similar to Das Ding , but further reduces and concentrates it so that the theremin comes more into focus. In Danger from Space (1953), soundtrack by Irving Gertz , Herman Stein and Henry Mancini , the vibrati from theremin and organ play a central role in the soundtrack, alongside shrill strings, an energetic bass and harp glissandi.

After the theremin was mainly used in the 1940s and 1950s to express authority and external threats, it was already so well established in the late 1950s and 1960s that it was parodied and used for comical effects. In the film, The Delicate Delinquent by Frank Tashlin from 1957 with Jerry Lewis in the title role of this discovered a theremin in an empty office and experimented some time around. In the sitcom Mein Unkel vom Mars , the eponymous uncle and Martian can extend and retract his antennas, among other things. This is accompanied by theremin music in the series.

The theremin was present on television in the 1960s primarily through science fiction programs, for example it played a prominent role in Dominic Frontiere's soundtrack for the television series Outer Limits - The Unknown Dimension , as well as a few years later in the soundtrack for the series Lost Between Alien Worlds .

Moog Theremin and Pop Music in the Mid-20th Century

In the 1950s, theremin construction developed into a popular hobby project for hobbyists and electronics tinkerers. Construction kits were also available in stores, as were building instructions that were printed in relevant magazines such as Radio Craft and Radio News . One of these hobbyists was Robert Moog , who was then young . He had been putting together Theremine as a hobby since he was 15. At 19 he began to publish articles about the theremin himself, and together with his father founded the R. A. Moog Co., which sold theremins and kits to other hobbyists by mail order from the basement. As a student at Columbia University , he assembled Theremine in his spare time and sold it to help finance his studies.

Moog began to study the instrument intensively and eventually replaced the vacuum tubes of the Termen Theremin with the then new transistor technology for the Theremin. The device became smaller and cheaper. Due to changed physical requirements, it was now also possible to use other input devices to control the Theremin. Moog expanded the instrument's range to five octaves and began using it for experimental music such as the John Cages pieces .

From these approaches he developed the Moog synthesizer , which revolutionized electronic music; after Moog temporarily separated from its production, he has been producing theremins again since the 1990s, Moog Music is now the world's largest theremin manufacturer.

The renewed theremin found its way into pop music. In 1966, the Beach Boys used the Tannerin for Good Vibrations , a (no longer contactless) Theremin variant with a tape manual, which brought the instrument into the charts worldwide and sparked new interest in the instrument among other professional and amateur musicians. A year later, created Captain Beefheart with Electricity one of the first songs of psychedelic rock , with incisive use of a theremin. The instrument had a second worldwide success in the Led Zeppelin recording Whole Lotta Love from 1969, in which a siren-like theremin played by Jimmy Page complements the guitar work. Lothar and the Hand People built the instrument into their set of instruments in 1965.

Development in the Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union itself, the theremin developed completely differently. Lew Termen himself had disappeared by 1964 and then began to work in the field of science again. Konstantin Kowalski was the main interpreter of the instrument. Despite the official rejection of modern music, he was able to play over 3,000 solo concerts between 1920 and 1980. He used an adapted tube theremin in which the right hand set the pitch, a pedal set the volume and various buttons that could be operated with the left hand could produce different effects. Between 1971 and 1976 he and Lev Sergejewitsch Koroljow developed a theremin with transistors. Among other things, this had a visual display of the pitch.

Kowalski himself had several students and played mainly Russian folklore, Soviet political songs and some popular classical pieces for the electronic ensemble of Russian television and radio. After Kowalski died in the early 1980s, Lydia Kavina took over his position in the electronic ensemble. On the other hand, Oleg Andrejew performed at the Theremin for the electronic ensemble of the Soviet Army . His repertoire mainly consisted of popular melodies from various genres.

Termen when he could, and Kowalski had several students who in turn trained new thereminists on a few occasions. An attempt to establish a state theremin center in Moscow in the early 1980s failed. The most influential of the students became Termen's great niece Lydia Kavina . She has also taught master classes in Germany and the United Kingdom since the late 1980s . After new pieces for the theremin were occasionally composed in the second half of the 20th century, their number increased significantly in the 1980s, after Kavina, a professional interpreter for new music, appeared. During the years of perestroika the Russian Association for Electroacoustic Music was organized, which researched Termen's work and enabled him to travel to conferences himself. Since 1992 there has been an electronic music studio at the Moscow Conservatory .

Renaissance since the 1990s

After the highs in the 1960s, the theremin disappeared from the wider public for a few decades. Occasional film appearances such as 1978 in the vicious circle Alpha can be recognized primarily as a reference to earlier films.

After the theremin had largely been pushed out of the public consciousness since the 1970s, a small renaissance began in the 1990s. After perestroika it became possible again in Russia to deal with the artistic avant-garde of the early 20th century. In 1988 Brian Eno composed the piece For her Atoms , which Termen's great-niece Lydia Kavina recorded. In 1992, the Moscow Conservatory established a theremin center. Termen himself was able to travel abroad again. The American filmmaker Steven Martin arranged a US trip to Termens, which brought him together with Clara Rockmore and led to a joint appearance. One year later, Martin's documentary Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey about Termen and the Theremin was released, which among other things won the prize for the best documentary at the Sundance Film Festival in 1994 and thus drew the attention of people around the world to the instrument and its history.

For Lev Termen's centenary in 1996, there were celebrations in Russia and honors and retrospectives around the world that reinforced the interest that was just beginning. While these were primarily aimed at scientists and professional musicians, amateurs began to discover the instrument more and more since the late 1990s. In addition to being reused in films, the Internet also contributed to this , in which, since the late 1990s, there have been instructions for building simple theremins, as well as game instructions and music examples.

The technology and music historian Hans-Joachim Braun explains this return of the theremin, among other things, with the “performative turn”, the replacement of a concentration of text in culture towards an increased emphasis on the performance, as found in various art styles of the late 20th century , but also in newer music. The contactless theremin is particularly effective in this type of performance. In addition, it is the only instrument that has been invented in recent times that requires a completely new and different playing technique than traditional instruments. As a result, many pop bands would use the theremin primarily for live performances, where it was particularly effective. Composer and musician Bob Ostertag, on the other hand, sees the small theremin renaissance as a counterbalance to the dominance of the laptop computer , which has disembodied electronic music more and more, so that there is no longer any connection between the movements of the artist and the music produced let.

Also striking, according to the two, is the re-mystification and re-ritualization of Western culture, which has set in since the 1970s and New Age culture. The performances of Clara Rockmore were often described as seance-like, she was considered the "high priestess of the theremin." The theremin with its non-contact, seemingly magical playing style is also available, as well as through the sounds generated by the theremin, which are often ghostly or can be described as unreal. The minimalist tone, which is often similar to singing, makes the Theremin particularly suitable for calm, meditative music.

The theremin also reflects the spirit of optimism of the modernism of the 1920s as well as a certain romantic and strongly aesthetic concept of technology that hardly exists today. Young performers would be attracted by the optimism about the future that the Theremin exuded at the time, as well as by the nostalgic return to a time when technology could still combine with the aesthetic ideals of romanticism.

The theremin also returned to film music, accompanied by a general renewed interest in the science fiction films of the 1950s and 1960s. The 1994 film soundtrack for Ed Wood, composed by Howard Shore , contains a prominent theremin played by Lydia Kavina. After 1994, various films took up the use of instruments: Mars Attacks (1996) contains pieces in which a theremin and Ondes Martenot appear. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005) by Danny Elfman uses the instrument, also The Machinist (2004). It is particularly exaggerated in the film 11:14 , in which the film music composer Clint Mansell uses the highest and lowest notes of the theremin for the most common and bizarre scenes, thus creating an alienation effect.

In 2007 the Theremin was on the list of the TEC Hall of Fame, which was launched by the TEC Foundation for Excellence in Audio in 2004 and is intended to honor and honor products and inventions that have made a significant contribution to the advancement of audio technology.

Usage today

New music

In the present, Lydia Kavina , Termen's great niece, who learned to play the theremin with him, appears as the leading virtuoso on the theremin. Her 1999 release Music from the Ether collected important compositions and pieces of recent times. The German Barbara Buchholz , a former student of Kavina, continued to work with her, but also went her own way, e.g. B. with a Theremin that can call up samples via MIDI . In 2006, Buchholz and Kavina published touch! don't touch! , for which contemporary composers were won over to compose for the theremin.

Other thereminists who perform in concert are Pamelia Stickney and Rob Schwimmer , Dorit Chrysler , and Carolina Eyck .

Composers who write for the theremin are Kalevi Aho , Jorge Antunes, and Kyoshi Furakawa . In 2000 Christian Wolff published his Exercise 28 for theremin, violin , horn and double bass .

The theremin is also used in music theater , e.g. B. in Olga Neuwirth's opera Bählamms Fest or John Neumeier's ballet The Little Mermaid .

In art, for example, the multimedia artist Eric Ross uses a theremin with a MIDI output. The composer Alvin Lucier works in the border area between science and art, his work concentrates on acoustic phenomena of the sound perception of the audience, his performances are often more reminiscent of a physics class than a stage appearance.

Popular music

Some musicians play the instrument or use it regularly in their pieces. Adrian Stout , member of the 'Brechtian Street Opera' band The Tiger Lillies , plays the theremin. The theremin is also used for pieces of music from the German music project Qntal . The minimal electro band Welle: Erdball uses the theremin for various pieces of music and also uses it for live performances. Panos Tsekouras plays the theremin in the Greek band Mani Deum .

The French musician Jean-Michel Jarre uses the theremin in some of his pieces. For example, he played at the Jarre concert in China or Oxygene in Moscow on a MOOG theremin - Big Briar Series 91. He also played the theremin in Gdansk , Poland at his concert in memory of Solidarność . It will also be used in one piece on his 2010 tour. The Italian electronic music composer Jean Ven Robert Hal uses the theremin in Laser Hal 1 (Part 1) .

In pieces by Tom Waits you come across the theremin again and again, both integrated in individual numbers and as part of the orchestra in various musical theater pieces such as Alice . It was played by Lydia Kavina during the performances in Hamburg's Thalia Theater .

Jon Spencer from the Blues Explosion formerly of the same name also uses the theremin again and again, especially often during live performances, but uses it more as an effects device than as a musical instrument.

The French singer and composer Émilie Simon is often supported in her performances by the IRCAM lecturer and researcher Cyrille Brissot with various experimental instruments, including a laser theremin.

The Australian electronic / crossover band Angelspit uses a Doepfer A-178 Theremin module with a corresponding modular synthesizer for their live performances .

The Australian post-rock band Heirs used the theremin early on at live concerts. Today it is an integral part of their mystical, eerie overall sound.

In his project Seerosenteich (2012), Philipp Poisel also uses a theremin in one piece.

Sting played on the tour with orchestra (2010) for the track Moon Over Bourbon Street from the CD Live In Berlin on a theremin.

Singer and guitarist Aaron Gregory also plays the theremin for the doom metal band Giant Squid .

The French singer Zaz plays a theremin herself in several songs on her live tours in 2016 and 2019.

The German dark rock band Lord of the Lost uses a theremin in several pieces of their 2016 album Empyrean .

jazz

Barbara Buchholz has also introduced the theremin into the jazz context on various occasions , for example in collaboration with the Jazz Big Band Graz . Pamelia Stickney also improvises with various jazz formations, including John Zorn , Brad Mehldau and Ravi Coltrane . Keyboardist and producer Travis Dickerson regularly uses a theremin in his projects (e.g. on the album Iconography with Bryan Mantia , Vince DiCola and Buckethead ). The theremin is also used by Gilda Razani in the bands The Dorf and About Aphrodite.

watch TV

Christopher Franke used a theremin for the music for the Babylon 5 TV film The Gate to the Third Dimension .

The music for the English crime series Midsomer Murders (Eng. Inspector Barnaby ) uses the theremin (played by Celia Sheen ) almost continuously, especially as a soloist in the title music, and should therefore be the most extensive application in television music.

In 2009 Barbara Buchholz took part with the Theremin at Supertalent on RTL . She was eliminated in the semifinals of the show.

In the fourth season of The Big Bang Theory , the protagonist Sheldon Cooper plays on a theremin.

In episode 484 Homer with the Finger Hands (Season 22, Episode 20) of the series The Simpsons , Milhouse van Houten plays for Lisa Simpson on the theremin. In episode 327 , Guess Who Comes to Dinner (Season 15, Episode 14), Artie Ziff plays a theremin in the Simpsons' attic.

Also in season 3 of the American Horror Story series, subtitled Coven , the witch Myrtle Snow uses a theremin.

Instruments developed from the theremin

Over the decades there have been some theremin-inspired instruments such as the Clavivox Ethonium or the Croix Sonore . In the decades of its existence, the theremin has initiated numerous instruments that build on the theremin, but significantly modify it. Some, like the Tannerin of the Beach Boys, try to simplify the operation of the instrument by regulating the volume control or even the pitch generation through a haptic input. The volume can then be regulated, for example, using an additional pedal. Others rely on new mechanisms of operation or sound generation based on the basic idea.

Simplified theremine

In the 1980s, the Russian engineer Vyacheslav Maximow and Termen created the Tonica , a simplified theremin that was primarily intended for use with children. However, they only made 25 copies of this instrument, which sold out immediately.

The Japanese Masami Takeuchi invented the matryomin in 2000: a theremin which he built into a matryoshka . Like some other mini retreats, this one has only one pitch control antenna. The field in which this instrument can be played is also smaller, but Takeuchi sees this as an advantage, since it makes it easier for several Matryomin players to play together. In 2010 a Matryomin ensemble was founded. The Japanese conceptual artist Yuri Suzuki developed another theremin . He designed a theremin that is operated by a swimming jellyfish.

Optical theremine

When he presented the Theremin in 1921, Termen had already mentioned the possibility of using the Theremin to create music and visual effects at the same time. Beyond a few experimental devices, this idea did not develop further over the following decades. The theremin developed by Konstantin Kowalski and Lew Koroljew between 1972 and 1976 was particularly influential in the Soviet Union and at times exceeded that of the term theremin in terms of importance. Termen himself helped to patent the instrument. This theremin is operated while seated. The theremin, which worked with transistors, had a pedal for playing the volume and several buttons with which the player could produce staccatos and trills with the left hand . It is possible to set different timbres on this instrument, reminiscent of a cello or an oboe , for example . It also has a display with which the player can read the exact pitch. The plans of both Termens and Kowaljos Theremin appeared in various Soviet electronics magazines during this period and in turn influenced third parties to develop other instruments based on them.

Since theremins are usually played completely contactless and offer the theremin player no visible or tangible orientation points, but only acoustic feedback, playing these instruments in a controlled and precise manner is very difficult and requires a high level of experience and practice. For this reason, various forms of so-called were optical theremins (Engl. Optical Theremin ) developed by additional visual elements like laser beams (by artificial fog made visible), the operation to simplify the instrument.

One of these laser theremins, also known as Termenova , designed by Leila Hasan at MIT , consists of several laser modules that are arranged in remotely controllable, movable sleds on a straight bar, next to which there is a theremin, whose antenna is perpendicular to the bar and thus parallel to the laser beams. Before use, the modules are calibrated to specific pitches by means of a controller , whereupon the mounted lasers are automatically moved into the spatial position (relative to the theremin) to which these pitches correspond when playing the theremin. In addition, when a laser beam is interrupted, the distance between the hand and the laser source is measured, which in turn can be linked to other acoustic effects such as volume control or distortion . These laser theremins have not got beyond the prototype stage.

Contactless instruments with capacitance sensors

The Theremin works on the same principle as capacitive distance sensors. Direct children of the theremin are other non-contact instruments that can also be controlled by changing capacitance in the electric field. The Terpsiton has an enlarged antenna for pitch (and no volume control) so you can (in theory) play it by dancing. However, there is currently only one copy in the possession of Lydia Kavina.

In the meantime, various instruments have come onto the market that have little in common with the theremin in terms of sound, but are inspired by its non-contact way of playing. They often serve as input aids for other electronic instruments. The radio drum and the radio baton , invented by Max Mathews in 1987, for example, function similarly to the theremin, look like a baton and influence a percussion instrument . Starting with Radio Baton, researchers at MIT developed the hypercello , which functions similarly to this instrument and has a wide range of possibilities, but can essentially be played like a cello. The Spirit Chair also came from its Media Lab , which allows a person sitting on a chair to call up a wide range of sounds by moving hands, feet and body. This was used, among other things, in the television program of Penn & Teller .

A special feature are so-called touch keyboards on synthesizers developed by Moog, which use such a capacitance sensor to measure the position of the fingers after pressing the key, which the player can use to influence the sound.

Non-contact instruments with other control mechanisms

In the 1990s, the Russian engineer Georg Pawlow developed a theremin that could be controlled by infrared sensors and thus had a significantly simplified design compared to the capacity-controlled theremins.

Even if the Theremin-like control was the first contactless control, instruments have now become established that can be played just as contactless but technically different. Often these have sensors that respond to ultrasound or optical stimuli. Some instruments work with radar or microwaves . In some cases, the inventors were inspired by the Theremin for the idea, design and operation of the instruments.

Optical techniques of gesture recognition for music control have been rapidly finding their way into music in recent years, but mostly have little or nothing to do with the theremin.

Another special form called "Photo Theremin" works with photocells and reacts to fluctuations in brightness. Such devices are usually a bit smaller and techno DJs occasionally use them in their performances. These instruments, which are popular in the DIY sector, are also known as optical theremins .

The Chimaera, for example, is polyphonic and based on the measurement of magnetic fields . Similar to the Theremin, there is a distance measurement, but with the help of the Hall effect . Several linear Hall sensors in a row detect the movements of permanent magnets that are worn on the fingers and used to generate sound; so they form a continuous two-dimensional interaction space.

Roland groove boxes

The Grooveboxes MC-505 to MC-909 from Roland also have a theremin-like sensor (D-Beam), although only the MC-505 can use this to generate sound. The British trip-hop band Portishead mentions a "Thereman" on the line-up for the album Dummy , but a Roland SH-101 was used. In other songs by the group, the theremin is imitated by a Moog synthesizer.

Discographic notes

- Samuel Hoffman (Theremin), Les Baxter , Billy May (Dir.), Harry Revel (Composition): Music Out of the Moon , Perfume Set to Music , Music for Peace of Mind (1947–1949, remastered as a 3-CD box Set 2004); Label: Basta

- Clara Rockmore (Theremin), Nadia Reisenberg (piano): The Art of the Theremin (1992), arrangements a. a. by Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Tschaikowsky, Glasunow, De Falla, Wieniawski; Label: Delos

- Lydia Kavina (Theremin): Music from the Ether (first recording of chamber music and solo works for the Theremin from 1929–1999, including by Martinů, Schillinger, Grainger, Kavina); Fashion records, 1999

- Lydia Kavina (Theremin), Olga Neuwirth (composition), Johannes Kalitzke (cond.), Klangforum Wien: Bählamms Fest (opera); Kairos Productions, 2003

- Lydia Kavina, Barbara Buchholz (Theremin); Chamber ensemble New Music Berlin, Wergo / Schott 6679-2 (CD): Touch! Don't touch! Music for Theremin. by Olga Bochihina, Caspar Johannes Walter, Juliane Klein, Moritz Eggert u. a.

- Barbara Buchholz : Theremin: Russia with Love / Label: intuition, SCHOTT Music & Media GmbH (2006)

- Barbara Buchholz: (Collaborations with: Jan Bang , Tilmann Dehnhard , Ulrike Haage , Arve Henriksen , Alejandro Govea Zappino, Kammerflimmer Kollektief , Jan Krause, Susanna and the Magical Orchestra ): Moonstruck / Label: intuition, SCHOTT Music & Media GmbH (2008)

- Lydia Kavina (theremin), Charles Peltz (cond.), Ensemble Sospeso: Spellbound! Works for theremin and chamber ensemble, a. a. by Miklós Rózsa , Howard Shore , Christian Wolff , Olga Neuwirth ; Fashion records, 2008

- Carolina Eyck: Carolina Eyck plays concert works for theremin , works by 13 different composers, with Giulietta Koch - piano, Rebekka Markowski - violoncello, Wiebke Lichtwark - harp, Magdalena Meitzner - vibraphone / percussion, 2008 SERVI Verlag, Berlin

literature

- Albert Glinsky: Theremin - Ether Music and Espionage . Univ. of Illinois Press, 2000, ISBN 0-252-02582-2 .

- André Ruschkowski: Electronic sounds and musical discoveries . Reclam, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-15-009663-4 (revised and extended edition of “Soundscapes”).

- Peter Donhauser: Electric sound machines: The pioneering days in Germany and Austria . Böhlau Wien, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-205-77593-5 .

- Carolina Eyck: The Art of Theremin Play: Textbook for the Theremin with sheet music, texts and photos, with over 150 exercises and etudes and approx. 20 edited and new pieces of music . SERVI Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-933757-07-X (German edition). ; The Art of Playing the Theremin . SERVI Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-933757-08-8 (English edition).

- Matthias Sauer: The Thereminvox - construction, history, works . epOs-Music, Osnabrück 2008, ISBN 978-3-923486-96-0 .

Web links

- Search for theremin in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Detailed page about the Theremin, with news and discussion forum (English)

- Very extensive portal to the theremin, with news and discussion forum (English)

- Instructions for building your own Theremin on the media art platform netzspannung.org

- Sound sample The swan from Carnival of the Animals at the University of Hamburg

- Open theremin

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Irina Aldoshina, Ekaterina Davidenkova: The History of Electro-Musical Instruments in Russia in the First Half of the Twentieth Century . (PDF; 3.8 MB) Proceedings of the Second Vienna Talk, Sept. 19-21, 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Leon S. Theremin, Oleg Petrishev: The Design of a Musical Instrument Based on Cathode Relays. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Vol. 6 (1996) p. 49.

- ↑ a b c d Chris Salter, Peter Sellars: Entangled: technology and the transformation of performance. MIT Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-262-19588-1 , p. 186.

- ^ Bob Ostertag: Human Bodies, Computer Music. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Volume 12, 2002, p. 13.

- ^ A b Nicholas Collins: Live electronic music in: Nick Collins, Julio d'Escriván (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to electronic music Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-86861-7 , p. 39.

- ↑ a b c d Chris Salter, Peter Sellars: Entangled: technology and the transformation of performance. MIT Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-262-19588-1 , p. 187.

- ↑ How to play a scale on the theremin Carolina talks Theremin

- ↑ Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco: Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01617-3 , p. 14.

- ↑ a b c d e Thom Holmes: Electronic and experimental music: pioneers in technology and composition. Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-95781-6 , p. 20.

- ↑ a b c Leo Sergejewitsch Theremin: Method of and Apparatus for the Generation of Sounds . U.S. Patent 1,661,058. February 28, 1928, p. 17 ( (here online) ).

- ^ Joseph A. Paradiso, Neil Gershenfeld: Musical Applications of Electric Field Sensing. In: Computer Music Journal. Vol. 21, No. 2, Summer, 1997, p. 70.

- ^ Richard Brice: Music engineering. Newnes, 2001, ISBN 0-7506-5040-0 , p. 99.

- ↑ a b Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs: audio technologies, memory and cultural practices. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 149.

- ^ Richard Brice: Music engineering. Newnes, 2001, ISBN 0-7506-5040-0 , p. 1.

- ^ Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 82.

- ^ Thom Holmes: Electronic and experimental music. Pioneers in technology and composition. Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-95781-6 , p. 19.

- ^ A b c d Natalia Nesturkh: The Theremin and Its Inventor in Twentieth-Century Russia. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Vol. 6, pp. 57-60, 1996, p. 57.

- ↑ a b c d Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 24.

- ^ Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 33.

- ^ A b Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 35.

- ↑ Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco: Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01617-3 , p. 54.

- ↑ a b c d e Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs. Audio technologies, memory and cultural practices. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 143.

- ↑ a b c Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs: audio technologies, memory and cultural practices Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 142.

- ↑ See illustration of a program slip.

- ^ A b c Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 25.

- ↑ Youtube

- ↑ Thom Holmes: Electronic and experimental music: pioneers in technology and composition Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-95781-6 , p. 21.

- ↑ Thom Holmes: Electronic and experimental music: pioneers in technology and composition Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-95781-6 , p. 21.

- ^ A b Peter Hitchcock: Oscillate wildly. Space, body, and spirit of millennial materialism. U of Minnesota Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8166-3150-6 , p. 182.

- ^ Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 45.

- ↑ cit. n. Nicholas Collins: Live electronic music. In: Nick Collins, Julio d'Escriván (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to electronic music. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-86861-7 , p. 39.

- ↑ theremin.info

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs. Audio technologies, memory and cultural practices. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 144.

- ↑ a b Julio d'Escriván: Electronic music and moving image. In: Nick Collins, Julio d'Escriván (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to electronic music. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-86861-7 , p. 160.

- ↑ a b Kristopher Spencer: Film and television scores, 1950–1979: a critical survey by genre. McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3682-8 .

- ↑ Kristopher Spencer: Film and television scores, 1950–1979. A critical survey by genre. McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3682-8 , p. 171.

- ↑ Jeffrey Sconce: Haunted media. Electronic presence from telegraphy to television. Duke University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8223-2572-1 , p. 120.

- ↑ Kristopher Spencer: Film and television scores, 1950–1979. A critical survey by genre. McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3682-8 , p. 215.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Braun: Music and technology in the twentieth century. JHU Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8018-6885-8 , p. 70.

- ↑ Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco: Analog Days. The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01617-3 , p. 15.

- ↑ Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco: Analog Days. The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01617-3 , p. 16.

- ↑ David John Cole, Eve Browning, Fred EH Schroeder: Encyclopedia of modern everyday inventions. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-313-31345-8 , p. 118.

- ↑ Jimmy Guterman: Maximmog. In: Mark Frauenfelder: Make. Technology on Your Time. O'Reilly Media, 2005, ISBN 0-596-10081-7 , p. 45.

- ↑ Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco: Analog Days. The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01617-3 , p. 87.

- ^ Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 227.

- ↑ a b c The Theremin and Its Inventor in Twentieth-Century Russia. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Vol. 6, pp. 57-60, 1996, p. 58.

- ^ A b c d Natalia Nesturkh: The Theremin and Its Inventor in Twentieth-Century Russia. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Vol. 6, pp. 57-60, 1996, p. 59.

- ↑ Kristopher Spencer: Film and television scores, 1950–1979. A critical survey by genre. McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3682-8 , p. 244.

- ^ A b c Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance. The evolution of sound in the electronic age. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 26.

- ↑ a b c Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs. Audio technologies, memory and cultural practices. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 147.

- ^ Bob Ostertag: Human Bodies, Computer Music. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Volume 12, 2002, p. 12.

- ^ TECnology Hall of Fame 2007. NAMM Foundation , accessed August 12, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c Hans-Joachim Braun: Pulled Out Of Thin Air? The Revival of the Theremin. In: Karin Bijsterveld, José van Dijck: Sound souvenirs. Audio technologies, memory and cultural practices. Amsterdam University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8 , p. 145.

- ^ Travis Dickerson - Iconography

- ↑ Mark J. Prendergast: The ambient century: from Mahler to trance: the evolution of sound in the electronic age Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7475-4213-9 , p. 62.

- ↑ Matryomin

- ↑ Olivia Solon: Artist Plays Theremin With a Jellyfish . Wired UK, 29th September 2010

- ^ Leon S. Theremin, Oleg Petrishev: The Design of a Musical Instrument Based on Cathode Relays. In: Leonardo Music Journal. Vol. 6 (1996), p. 50.

- ↑ Dynamic Visual Guides for Free-Gesture Musical Interaction. Massachusetts Institute of Technology , accessed April 8, 2010 .

- ^ Leila Hasan: Visual Frets for a Free-Gesture Musical Interface. (PDF; 1 MB) Massachusetts Institute of Technology , June 3, 2003, accessed April 8, 2010 .

- ^ A b Joseph A. Paradiso, Neil Gershenfeld: Musical Applications of Electric Field Sensing. In: Computer Music Journal. Vol. 21, No. 2, Summer, 1997, p. 69.

- ↑ Article and interview with Lydia Kavina ( memento of the original from November 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on thereminvox.com

- ^ A b Joseph A. Paradiso, Neil Gershenfeld: Musical Applications of Electric Field Sensing. In: Computer Music Journal. Vol. 21, No. 2, Summer, 1997, p. 71.

- ^ Joseph A. Paradiso, Neil Gershenfeld: Musical Applications of Electric Field Sensing. In: Computer Music Journal. Vol. 21, No. 2, Summer, 1997, pp. 84-87.

- ^ Sergi Jorda: Interactivity and live computer music. In: Nick Collins, Julio d'Escriván (Ed.): The Cambridge companion to electronic music. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-86861-7 , p. 98.

- ↑ Chimaera, the poly-magnetophonic theremin . Retrieved October 11, 2014. Hanspeter Portner: CHIMAERA - The Poly-Magneto-Phonic Theremin - An Expressive Touch-Less Hall-Effect Sensor Array . In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression . Goldsmiths, University of London, pp. 501-504. Link (PDF) Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ↑ Interview with Adrian Utley (Portishead)