asceticism

Asceticism ( ancient Greek ἄσκησις áskēsis ), occasionally also asceticism , is a term derived from the Greek verb askeín (ἀσκεῖν) 'practice'. Since ancient times , it has been used to describe a practice in the context of self-training for religious or philosophical motivation. The aim is to achieve virtues or skills, self-control and strengthening of character. The practitioner is called an ascetic (Greek ἀσκητής askētḗs ).

An ascetic training includes discipline both in terms of thinking and volition and in terms of behavior. This includes on the one hand the persistent practice of the desired virtues or abilities on the one hand, and on the other hand the avoidance of everything that the ascetic believes stands in the way of achieving his goal. The starting point is the assumption that a disciplined way of life presupposes the control of thoughts and drives. The most noticeable effect on life is the voluntary renunciation of certain comforts and pleasures that the ascetic considers to be a hindrance and incompatible with his ideal of life. In most cases, the renunciation primarily affects the areas of luxury goods and sexuality. In addition, there are measures for physical and mental training, in some cases also exercises in enduring pain.

In today's parlance, the words ascetic , ascetic, and ascetic are used when voluntary abstinence is practiced for the purpose of attaining a higher-value goal. Religious or philosophical motives can take a backseat or be omitted entirely.

Appearances and characteristics

In religious studies , numerous practices of self-control and renunciation fall under the concept of asceticism. Ascetics are people who have dedicated themselves to a form of life determined by permanently selected ascetic practices. Many ascetics have written texts in which their way of life is presented, often idealizing and advertising. In recent research, various cross-cultural proposals for defining asceticism are discussed, including its definition as "an at least partially systematic program of self-discipline and self-denial".

In numerous religions and in the norms of behavior of many indigenous peoples , asceticism is assessed positively and - often according to fixed rules - practiced temporarily or permanently, individually or collectively. Often there are limited ascetic exercises, such as observing certain periodically recurring periods of penance, fasting or mourning or abstinence and hardening in the context of preparation for rites of passage .

The aspects of voluntariness and the deliberately pursued overarching goal are always included, at least in theory. Therefore, someone who leads a modest, poor-enjoyment life under the coercion of external circumstances such as food shortages and poverty is not considered an ascetic. However, asceticism is often part of strict religious or social norms that are mandatory for members of certain groups or, in some cases, for all believers. The transition between voluntariness and coercion, mere recommendation and regulation associated with the threat of sanctions is therefore fluid.

Manifestations of asceticism, which occur in different combinations, are:

- Temporary or permanent renunciation of all or some stimulants and in particular avoidance of intoxicants

- Food asceticism (fasting or restricting the diet to what is absolutely necessary)

- sexual abstinence (temporary or permanent as celibacy )

- Avoidance of cosmetics and personal hygiene (for example, washing, beard and hair cutting; the hair is completely or partially shaved or it is no longer cut at all)

- Modest or coarse, uncomfortable clothing, in some cases nudity

- sleep deprivation

- voluntarily enduring cold or heat

- hard place to sleep

- Renunciation of property, voluntary poverty, begging

- Withdrawal from normal social community

- Classification in the group discipline of a religious or ideological community that demands the renunciation of personal needs

- Obedience to a spiritual authority figure such as an abbot or guru

- Waiver of communication ( confidentiality )

- Restriction of freedom of movement ( retreat , hermit cell)

- Homelessness, "homelessness" (permanent wandering, pilgrimage)

- physical exercises such as the Japanese running ascetic in the Kaihōgyō ritual , long standing, persistent sitting in special positions

- physical pain and wounds that the ascetic inflicts on himself, as a special form of asceticism.

Motivations

There are many reasons for asceticism. A motive is a fundamentally critical attitude towards the world. In elaborated religious and philosophical systems of teaching, the background of the demand for asceticism is usually a more or less pronounced rejection of the world; The sensually perceptible world is not classified as absolutely bad in all ascetically oriented systems, but it is usually considered threatening, questionable and inherently very poor. Therefore, the ascetic wants to reduce his internal and external dependence on her as much as possible by curbing or eliminating his desires and expectations directed towards sensual enjoyment and by practicing frugality. The pursuit of virtue provides positive motivation, which from an ascetic point of view can only be successful if the desired virtues are constantly practiced through ascetic practice. In religions that assume life after death , the ascetic striving for virtue serves primarily to prepare for a better future existence in the hereafter . Some ascetics who hope for an advantageous position in the hereafter want to qualify for it through their asceticism. They expect some otherworldly reward for their earthly renunciation. A motif more closely related to this world, which also appears in world-affirming teachings, is the need to gain a superior attitude towards the vicissitudes of fate through practice. You want to be better able to face the challenges of life. The goal is inner independence and freedom from fears and worries. Another aspect is gain in power: In the case of magicians, shamans and members of secret societies , ascetic practices for a limited period of time should serve to acquire magical abilities. The practitioner can hope for power over his surroundings and a high social rank.

Asceticism comes in many variants and gradations from moderate to radical. The degree of skepticism towards enjoyment fluctuates accordingly. Radical ascetics generally judge sensual pleasure negatively. They think it is inherently incompatible with their philosophical or religious goals and only creates undesirable dependencies. Therefore they want to eradicate the desires directed towards it as completely as possible. In moderate variants of asceticism, enjoyment is not rejected under all circumstances, but one just wants to put an end to dependence on it.

Relationship to the environment

In many religious traditions, ascetics enjoy a special reputation. They are ascribed excellent, sometimes superhuman abilities, consulted as religious authorities and expected from them spiritual advice and instruction, sometimes healing. Literature that glorifies renunciation encourages such expectations. The reputation of wisdom or holiness gives the ascetics an extraordinary prestige. They are given veneration and gratitude, and it is considered honorable and meritorious to support them materially. However, this prestige proves to be problematic as it opposes the ascetic flight from the world and can undermine the integrity of the prestige bearers. A dilemma arises: the more rigorously and successfully the asceticism, the more social attention the practitioner will find. The more famous he becomes, the more often he is sought out by admirers and those seeking advice, and the more important his authority becomes. But then it becomes all the more difficult to continue the world-fleeting practice that established the gain in prestige. It can only succeed if special efforts are made to remove or at least reduce social integration. This proves difficult, however, because fame haunts whoever tries to escape it.

A high religious value is attached to the ascetic life, but it does not represent a direct model for the life of the ordinary citizen. Rather, it is precisely the otherness of the ascetic way of life that establishes the prestige of the ascetic and, despite all the popularity of his person, an unbridgeable distance to it Environment created. He is admired but not imitated. After all, one can participate in his life by giving him gifts. The ascetic's belonging to his family of origin, which shares in his prestige, creates a different relationship to the lifeworld of the social environment. In ancient Christianity, for example, there was a strong awareness of the permanent enhancement of family honor by an admired ascetic family member.

The dangers of fame are strongly warned in the literature that gives instructions on renunciation. In contrast to other types of prestige, ascetic prestige is fundamentally undesirable, at least in theory. It threatens to create arrogance and is portrayed as a plague. Any striving for reputation is even more harmful and condemnable. This problem is discussed in ascetic texts from western and eastern cultures, and strategies are developed which are intended to prevent the creation of prestige. The religious scholar Oliver Freiberger uses Eastern and Western sources to differentiate between four approaches to dealing with the ascetic dilemma. The first and most radical option is to flee to a truly secluded area and thus cut off any social interaction. The second way is to create “anti-prestige”: the ascetic tries to get the world to turn away from him. To this end he makes a fool of himself. He is so offensive that he is thought to be insane, or he tries to appear simple and stupid to make him despise. The third option is different behaviors with which the ascetic maintains his inner distance despite being close to the population. The fourth approach is the institutionalization of prestige: the ascetic appears as a member of an order, and the prestige is shifted from the individual to the order.

In addition, the folklore of many cultures contains an abundance of biting and humorous stories about the abuse of ascetic prestige. False ascetics, charlatans, who feign asceticism are portrayed in order to exploit people's gullibility and gain prestige and money. The figure of the swindler who feigns renunciation and is in reality greedy and voracious or sexually interested is a popular motif in narrative literature. The appearance of such deceivers creates ridicule and discredits asceticism.

Traditions of Indian origin

In India ascetics apparently appeared as early as the epoch of the Indus culture (3rd and early 2nd millennium BC). The oldest known religious-philosophical systems, in which radical or moderate asceticism form an essential part, arose in India: Jainism , Buddhism and Hinduism .

Hinduism

In the older writings of the Vedic religion , which began in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, After the immigration of the Aryans , asceticism occurs only sporadically. In the Upanishads , which were written in the first half of the 1st millennium BC. Began, but the technical term for asceticism, tapas (in Sanskrit "heat" or "embers"), already plays an important role. What is meant is the inner glow that the ascetic creates through his efforts (śrama) . One of the exercises is to expose yourself to the sun and light fires around you. Tapas is said to give the practitioner extraordinary strength and power; one wants to rise above the limits of what is usually possible. This endeavor is about the strengthening aspect of asceticism, which is also an essential sub-goal in yoga . In addition, the world rejection and the strived for liberation from the material world is a core component of the asceticism concepts developed in India. Ideals of the ancient Indian ascetic way of life, which continue to have an effect up to the present day, are the acquisition of truth, the non- acquisition and the non-violation ( ahiṃsā ) .

In the Dharmasutras (handbooks of religious precepts) written around the 5th or 4th century BC Were recorded, there is precise information about the way of life of a "forest dweller" (vānaprastha) and a wandering ascetic (parivrājaka) . These were ascetics who - often only at an advanced age - either withdrew to the loneliness of the forest or wandered around begging. They performed demanding physical exercises, the aim of which was to “cleanse” or “dry out” the body and at the same time to achieve a calm basic posture and to maintain it even under the most difficult conditions. There were detailed rules for the diet and clothing of the ascetics and for the implementation of the principle of non-possession. All unnecessary talking was strictly to be avoided.

Many Indian sages ( Rishis ) practiced and recommended an ascetic way of life. Traditionally, ascetics are highly respected in Hindu society. They appear as yogis, sadhus (“good people who reach the goal”) or sannyasins (“renunciate”), as fakirs or as followers of tantrism .

Famous modern ascetics like Ramakrishna († 1886) and Ramana Maharshi († 1950) also became known in the West. Mahatma Gandhi († 1948) achieved a particularly strong broad impact , who gave the traditional Hindu ideal of asceticism a new, long and strong impetus through his role model.

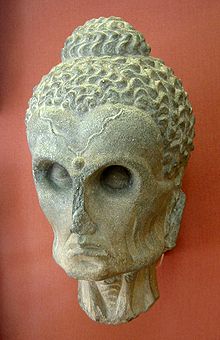

Buddhism

The founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama , who, according to current research, was in the late 5th or early 4th century BC. Died, initially practiced a very strict asceticism, which he broke off when he came to the conclusion that it was useless. Thereupon he formulated the Buddhist doctrine as differentiating it from the ascetic practices of the Brahmanic monks and Jainism , which he rejected. He proclaimed the "middle way" ( Pali : majjhimā paṭipadā ) between the two extremes of what he saw as exaggerated asceticism and an unregulated enjoyable life. This path was originally conceived for bhikkhus (monks, literally “beggars”) and contained ascetic provisions for monastic life, but no self-tormenting practices. The body should not be harmed or weakened.

The concept of the ascetic was known to the early Buddhists. They spoke of samaṇa ("one who makes an effort"). The rules included dispossession, the simplest of clothing, complete sexual abstinence, renouncement of intoxicating drinks and the obligation to eat everything that is placed in the begging bowl. The monks did not have a permanent residence, they wandered around all year with the exception of the rainy season. That is why they were also referred to as "moved into homelessness". Ascetic exercises, which were not prescribed to the monks and nuns, but were recommended in stricter directions, were called dhutaṅgas ("means of shaking off"). These were restrictions in nutrition, clothing and living conditions, some of which went far beyond the generally practiced abstinence of the members of the order. Dhutaṅgas are still valued today in the " Thai forest tradition ".

Jainism

Jainism is the one among the religions that arose in India which places the toughest demands on asceticism on its followers - both monks and nuns as well as lay people . Numerous strict regulations must be observed, especially with regard to nutrition, enjoyment is frowned upon and there is a lot of fasting. The commandment of consistent non-violence ( ahiṃsā ) extends to dealing with all forms of life, including harmful insects and microorganisms. This brings with it a multitude of restrictions and inconveniences in everyday life, because accidental damage to living beings of all kinds must also be prevented by taking precautionary measures. There is also a rigorous control of thoughts.

The aim of asceticism (tava) is to avoid sinful entanglements which, according to the Jaina doctrine, generate harmful karma and thus cause the continuation of a painful existence. The aim is a radical possible separation of the soul ( jiva ) from this side of the world. Through renunciation the believers want to bring about their redemption . They want to escape from this world and gain access to a transcendent hereafter, in which they then finally remain. Their role models are the Tirthankaras , famous ascetics like Parshva and Mahavira , who, according to the Jainas' belief, have achieved this goal.

The prerequisite for success is not only the preservation of external ascetic discipline, but also the eradication of harmful impulses such as pride. This aspect is illustrated by the legend of the proud ascetic Bahubali , whose efforts failed despite perfect external self-control until he recognized and overcame his pride. Harmful passion, which hinders the ascetic life, shows itself according to the Jaina doctrine in the four forms anger, pride, deception and greed. Anger arises from the experienced or anticipated removal of pleasant things or from bringing in unpleasant things, as well as from being hurt. Physical and mental merits and achievements as well as social rank give rise to pride or conceit; ascetic practice and elitist knowledge make religious people conceited. Deception or deception is anything that contradicts the truth: both your own turning to errors and bad ways of life and the misleading of others. Each of the four passions leads to karma and must therefore be completely eliminated. This happens through asceticism, which includes the defense (saṃvara) of the threatening bad influences and the eradication (nijjarā) of the karma that has already flowed towards you . Means of defense include enduring the twenty-two challenges, including hunger, thirst, heat, cold, stinging insects, insults, abuse, rejection and disease.

Among the various directions in Jainism, the most radical is that of the Digambaras ("air-clad"), in which the monks, following the example of Mahavira, live completely naked. A possible climax of asceticism is ritual death through voluntary starvation. The Jainas attach great importance to the statement that this ritual, known as sallekhana , is by no means a suicide.

Greek and Roman philosophy and religion

Asceticism in general and in philosophical usage

In ancient Greek , the verb askein originally referred to a technical or artistic production or processing, the careful operation or practice of a technique or art. It was in that sense that Homer used it . With regard to the human body, it was a matter of fitness through gymnastics or military training; Warriors and athletes were called ascetics. In the field of ethics , áskēsis was understood as a training with the aim of acquiring wisdom and virtue through practice and thus realizing the ideal of aretḗ (ability, excellence) also in the spiritual sense. The transferred meaning (exercise of virtue or efficiency) is already attested in Herodotus . The pre-Socratics Democritus stated: "More people become capable through practice (ex askḗsios) than through natural disposition ." Even with the early Pythagoreans (6th / 5th centuries BC), moderation and self-control as well as the willingness to renounce were core components the philosophical way of life aimed at the perfection of virtue. In this milieu asceticism also had a religious meaning; ascetic acts meant “following God”.

Socrates and Plato

Socrates (469–399 BC) was regarded as a model of virtue . His student Xenophon praised his self-control (enkráteia) and found that Socrates had made it the furthest of all. He had shown the greatest perseverance in the face of frost and heat and all toil and regarded self-control as the basis of virtue, since without it all efforts would be in vain. Xenophon stressed the need for mental and physical exercise as a means of achieving such self-control; according to his account, Socrates claimed that by practicing, the naturally weak could outperform the strong if they neglected training. A detailed description of the self-discipline of Socrates and his perseverance in enduring hardships and hardships was given by his famous student Plato in the literary dialogue symposium . However, this exemplified philosophical asceticism met with criticism from contemporaries. So the comedy poet Aristophanes mocked the lifestyle of the circle around Socrates; he saw it as an absurd fad.

Plato advocated a simple and natural way of life as opposed to the exuberant one, which he censured. But he did not mean a return to a more primitive level of civilization, but purification of everything excessive. This creates prudence and inner order in people. The necessities of life are to be satisfied, but not those that go beyond what is necessary. Like his teacher Socrates, Plato emphasized the importance of gaining self-control. By asceticism, he understood spiritual exercises that relate to thinking and willing and aim at aretḗ (fitness, virtue, “being good”): One should practice “justice and the rest of the virtue”. Practicing like this, one should live and die, that is the best way of life. In the discussions at that time about upbringing and character formation, the weight and interaction of three factors were discussed: the natural disposition, instruction and practical training (áskēsis) .

Stoa

With the Stoics , ascetic "practice" was given a prominent role in the philosophical way of life. With them, the aspect of abstention and renunciation was in the foreground. Asceticism was seen primarily as a spiritual discipline. The physical aspects were also important, but secondary. Physical practices without a spiritual basis and purpose were considered useless; an outward, demonstrative asceticism aimed at impressing others was resolutely rejected. Mastery of thoughts and urges should free the stoic philosopher from the tyranny of changeable states of mind and thus give him inner peace and freedom. The aim was "apathy" ( apátheia ) : suppression of painful and destructive affects such as anger, fear, envy and hatred, ideally freedom of the mind from any excitement. The apathy understood in this way was considered in the Stoa as a prerequisite for ataraxia (composure, imperturbability). The stoic ascetic ideal was well received in the Roman Empire . The Stoic Epictetus gave detailed information about the necessary exercise steps. A prominent Stoic ascetic was Emperor Mark Aurel . The imperial stoics demanded the fulfillment of civic duties, which, according to them, also for philosophers belonged to marriage and child witnessing.

Cynic

A particularly radical asceticism was the main characteristic of the Cynics . They understood this to mean, above all, physical hardening, which should lead to the strengthening of willpower, and renunciation of the values and comforts of a civilized way of life. Cynical philosophers led a wandering life. They reduced their possessions to the bare minimum that they could fit in their satchel. The needs were radically limited to the basic. The Cynics did not associate the ideal of poverty with a devaluation of the body, sexuality and enjoyment; one should be satisfied with the little that one had, but one could enjoy it. As part of their consistent rejection of the prevailing moral concepts, the Cynics advocated and practiced sexual permissiveness and spontaneous instinctual satisfaction. The immediate satisfaction should make the hope of future pleasure superfluous and thus prevent the emergence of avoidable needs. Diogenes of Sinope , a prominent Cynic, is said to have remarked that it was a mark of the gods to be needless and of godlike people to need little. According to anecdotal tradition, Diogenes lived in a barrel. The Cynics cultivated their outsider role in society and among philosophers: their main interest was in physical functions, they were not interested in civic duties, and they were offensive with their provocatively unkempt appearance. Even in the 4th century, Emperor Julian polemicized against the Cynics of his time, although he himself was a staunch ascetic.

New Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists

The neo-Pythagoreans of the imperial period represented a completely different expression of the ascetic ideal . In Neo-Pythagorean-oriented circles the ideal of lifelong sexual abstinence of the philosopher was propagated, as can be seen in the biography of the New Pythagorean ascetic Apollonius of Tyana , written by Philostratus in the early 3rd century .

The philosophy that dominated late antiquity , Neoplatonism , was ascetic from the start. With the Neoplatonists, the goal of liberating the soul from the prison of the body and its return to its purely spiritual home, the intelligible world, was in the foreground. The prerequisite for this was the extinction of body-related desires. The Neoplatonist Porphyrios reports that the Roman senator Rogatianus was so impressed by the Neoplatonic doctrine that he renounced his senatorial title, gave up all his possessions and released all his slaves. The letter of Porphyrios to his wife Marcella is an advertising pamphlet ( Protreptikos ) for an ascetic philosophical way of life.

Religious abstentions

For a number of cults from Greek and Roman antiquity, renunciation exercises are attested. In the Greek religion, abstinence played a greater role than in the Roman. Fasting customs and sexual asceticism by religious officials were widespread. Temporary abstention regulations applied to the participants in the mystery cults , whose ordinations were only given after a period of preparation that was associated with waivers. However, all these prohibitions aimed at cultic purity were only ritual rules from which no ascetic ideal of life developed. However, there are approaches to such an approach among the Orphics . They practiced the "Orphic life", a way of life that included the observance of abstinence instructions and the thought of man's responsibility before the Godhead.

Judaism

Judaism originally had few ascetic traits, as the world as God's creation was viewed positively and enjoyment was viewed without mistrust. Some regulations for a limited abstinence and regulation of enjoyment in the time of the Tanach were not rooted in ascetic ideas, but in old magical ideas. This included the belief in the ritually polluting effect of sexual intercourse, which the priests were therefore forbidden before ritual acts. Wine consumption was also prohibited before the sacrificial service. Fasted in preparation for receiving divine revelation.

The formation of an ascetic mindset began with the advent of the collective penitential fast, which was publicly ordained as an expression of repentance in order to quench the wrath of God and avert his judgment. The idea arose that joint or individual fasting was pleasing to God and therefore increased the effectiveness of prayer or caused God to finally answer a prayer that had not been answered before. Fasting became a meritorious work for which wages were expected.

In the early Roman Empire, the Platonically influenced theologian Philo of Alexandria raised a philosophically based demand for asceticism. For him the patriarch Jacob and Moses were exemplary ascetics. In Philo's time there was already an ascetic tendency in Judaism; He depicts the life of the " therapists ", a community of Egyptian Jews who gave up their property and withdrew from the cities to sparsely populated areas for a common ascetic life. The Essenes , a group of pious Jews who renounced personal possessions and led a simple, frugal life with community of goods, were also ascetic . Flavius Josephus tells of them that they viewed pleasure as a vice and saw virtue in self-control and overcoming passions. They refused to reproduce and instead adopted other children.

In medieval Jewish philosophy, under the influence of Neoplatonism and the ascetic currents of Islam ( Sufism ), ideas and concepts of renunciation that rejected the world gained in importance. The Jewish exile consciousness contributed to the intensification of such tendencies. A moderate asceticism in connection with a neo-Platonic worldview can be found, for example, in the book of the duties of the heart by Bachja ibn Paquda and in the treatise Meditation of the Sad Soul by Abraham bar Chija , a negative evaluation of sensual pleasures in Maimonides and in Kabbalah . Maimonides' son Abraham quotes authors of Sufism in his Compendium of Servants of God . The earlier prevailing opinion that asceticism as a whole was and remained alien to Judaism is being corrected in more recent research, and various ascetic impulses among medieval Jewish authors are being examined. What these Jewish advocates of asceticism have in common is that they rejected withdrawal from society. They expected the ascetic to take part in social life and fulfill his social tasks.

Gnosis

In some of the ancient Gnostic communities, ascetic practices (sexual abstinence, fasting, renouncing meat consumption) were considered necessary for salvation. The motive was radical rejection of the world. Even the Manichaeism , one resulting in the 3rd century, influenced by the ideas of Gnosis religion, stressed the need for austere lifestyle. The Manicheans demanded lifelong sexual abstinence, a life of poverty and frequent and strict fasting from their elite (Latin electi "the chosen").

Christianity

Asceticism has been part of Christian teaching and tradition from the very beginning. It serves the pursuit of perfection in the sense of the Christian doctrine of virtues. As the most radical form of ascetic life, first hermitism and then coinobitic monasticism emerged in antiquity , which was one of the most important factors in cultural history in the Middle Ages. In the age of the Reformation , however, there was a fundamental criticism of the concept of monasticism and thus also of the traditional ideal of asceticism.

New Testament

In the New Testament , the noun asceticism does not appear and the verb askein only appears in one place ( Acts 24:16) in the sense of 'endeavor' without any connection with asceticism. Jesus criticized the practice of demonstrative asceticism (Matthew 6: 16-18), which was common at the time, but this criticism was not directed against asceticism as such, but against its display in order to gain reputation.

Although there is no term, renunciation in the ascetic sense is often and extensively discussed in the New Testament. Examples are in the Gospels of Mark 8:34: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny himself, take up his cross and follow me” (cf. Luke 9:23); Luke 14:26: "If someone comes to me and does not respect father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, even his life, then he cannot be my disciple" (cf. Luke 14:33); Matthew 5:29 f .: “If your right eye causes you to do evil, then tear it out and throw it away! [...] And if your right hand seduces you to evil, cut it off and throw it away! "; Luke 21:36: “Watch and pray without ceasing” (taken up in 1 Thessalonians 5:17 and 2 Timothy 1: 3); Matthew 6: 16-18 (recommending fasting with a promise of heavenly reward for it); Matthew 19:12 (celibacy for the kingdom of heaven); Matthew 19:21: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give the money to the poor; so you will have a lasting treasure in heaven ”. Jesus points out that he is homeless, he "has no place to lay his head" (Matthew 8:20). Luke in particular emphasizes the need for strict asceticism among the evangelists . In addition to justice, he mentions abstinence (enkráteia) as an essential characteristic of Christian teaching.

There are also points in the Gospel of John (John 15:19) and in the first letter of John (1 John 2: 15–17) which can justify an ascetic rejection of the world . In addition, there is the example of the ascetic John the Baptist and his disciples. He preached in the wilderness, ate locusts and wild honey, and fasted his disciples (Mark 1: 4-6 and 2:18; Matthew 11:18).

In the letters of the apostle Paul various ascetic ideas are presented. The vocabulary of the sporting competition ( agon ), in particular the race, is used. Paul compares the toil of living a Christian life to the discipline of athletes who go through hardship to win a fight. The goal is the victory wreath , which the apostle makes an eschatological metaphor . So he writes: “Every competitor lives completely celibate; those do this to win an imperishable, but we do so to win an imperishable wreath. That's why I don't run like someone who runs aimlessly and I don't fight with my fist like someone who hits the air; rather, I chastise and subdue my body ”(1 Corinthians 9: 25-27); “If you live according to the flesh, you must die; but if by the Spirit you kill the deeds (sinful) of the body, you will live ”(Romans 8:13); “That is why I say: let the Spirit guide you, and you will not fulfill the desires of the flesh. For the desire of the flesh is directed against the spirit, but the desire of the spirit is directed against the flesh; both face each other as enemies ”(Galatians 5:16 f.); "All who belong to Christ Jesus crucified the flesh and with it their passions and desires" (Galatians 5:24); “Therefore kill what is earthly about you: fornication, shamelessness, passion, evil desires and covetousness, which is idolatry” (Colossians 3: 5). The asceticism that Paul advocates is Spiritual; he criticizes the tormenting of the body, which in reality only serves to satisfy earthly vanity (Colossians 2:23). The author of the First Letter of Timothy , who opposes the prohibition of marriage and eating, also warns against overemphasizing physical exercise (1 Timothy 4: 8).

Epoch of the Church Fathers

Great Church

From the 2nd century, the term asceticism is attested in Greek theological literature. It was first used in Alexandria , where Philon's influence continued to have an impact. An ascetic trait became noticeable early on in the edifying writings of Christians. Usually one justified the demand for abstinence with the following of Jesus , sometimes also with the expectation of the end times ; one believed to have to arm oneself for the horrors of the coming end times before the end of the world . Another motive was the incessant fight against the devil , which, according to a popular belief at the time, only ascetics can win. In addition, some Christians wanted to anticipate the future way of life in the kingdom of heaven, where there should be no earthly pleasures, and to live like angels if possible .

In the New Testament Apocrypha , especially the apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, which were part of the edifying entertainment literature of early Christianity, great importance was attached to chastity and poverty. The church father Clemens of Alexandria , who was active in the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries, emphasized the importance of ascetic exercise and recommended the eradication of all instinctual impulses. However, he did not interpret the poverty commandment of the Gospels literally, but allegorically : the possessions that one had to give up are the undesirable passions. This view was contradicted by Origen in the 3rd century , who advocated a strictly literal understanding and argued that even a non-Christian, the originally rich Cynic Krates of Thebes , had given away all his possessions in order to gain spiritual freedom; therefore a Christian must really be able to do so. Origen interpreted the following of Jesus so radically that he interpreted the passage in Matthew 19:12, which speaks of voluntarily induced incapacity to marry for the sake of the kingdom of heaven, as an invitation to castration and therefore had himself castrated by a doctor as a young man. His decision, which he later regretted, was imitated. The idea was widespread that Adam's expulsion from paradise was due to his lust for pleasure and that humanity could pave the way into the kingdom of heaven through the opposite behavior, fasting; in late antiquity she represented a. a. the church father Basil the Great . In general, fasting was considered meritorious. Jesus' forty-day fast in the desert (Matthew 4: 2-4), during which he eventually felt hungry but resisted the temptation of the devil , served as a model for the steadfastness required. In the case of educated late antique church fathers such as John Chrysostom , Ambrosius of Milan , Hieronymus , Basilius the Great and Gregory of Nyssa , the influence of Stoic, Cynical and Neoplatonic ideas and models became noticeable in the argument for an ascetic way of life.

In the late 3rd century, the hermitage of the first anchorites spread throughout Egypt . Its most famous and influential representative was the hermit Anthony the Great, often referred to as the father of monasticism . The monks lived for the sake of asceticism in the desert ( desert fathers ), partly in monk cells, partly as wandering ascetics. Nudity was considered the highest level of asceticism; individual hermits realized their ideal of poverty so radically that they did without any clothing.

Anthony the Great regarded asceticism not as a merit, but as a duty. He is convinced that it gives the ascetic the ability to completely fulfill the commandments and makes him worthy of the kingdom of heaven. One of the first requirements for this is the rejection of the "world". This means giving up material possessions and shedding all family ties. The church father Athanasius the Great contributed significantly to the dissemination of these ideas with his biography of Antonius. The first organized monastic communities developed from the Egyptian hermit in the early 4th century . They adopted the ascetic ideal of the hermits in a modified form. The founder of the monastery, Pachomios († 347), played a key role .

The current based on the teachings of the desert fathers was hostile to civilization and education, it rejected the “pagan” cultural tradition. Their attitude forms the opposite pole to the view of the church father Hieronymus, who was exemplary for a different direction in monasticism. Jerome lived ascetic, promoted this way of life and glorified the ascetic desert life, but was at the same time a scholar and loved to spend his time in his extensive library. He became the archetype of the educated Christian who combines asceticism with classical ancient education and scientific work. However, his relationship with traditional educational goods was fluctuating and full of tension.

In Syria, a special form of asceticism emerged in the 5th century: the spectacular way of life of the columnar saints (stylites) who took permanent residence on columns. Even in pre-Christian times it was common for a worshiper of the god Dionysus to climb one of the phallic columns in the temple of Hierapolis Bambyke twice a year and stay up there for seven days each time. It was believed that he was close to God at this time. The first column saint, Symeon Stylites the Elder , built the column, which then served as his home.

In broad strata of the people there was great respect for the pillar saints and the admiration of their way of life. In late antiquity, ascetics also enjoyed the highest reputation. Even Antony the Great was so respected that correspondence with him was considered a special honor and even the Roman Emperor wrote to him. Many Christians, including celebrities, went to the desert to seek advice and help from the hermits. In doing so, they thwarted the hermits' desire to live secluded in solitude and, in some cases, caused them to flee to more remote places. For the ascetics, fame was a challenge.

Even noble women opted for an ascetic way of life, often after their widowhood. Some of them stayed in their previous status, some of them entered monasteries. They devoted themselves to physical labor, charitable activities and the study of religious literature.

Christian asceticism met with incomprehension and severe criticism among educated non-Christians from late antiquity. It has been classified as stupidity, disease and madness. There were also critics among Christians. Among them was the at times influential church writer Jovinianus , who believed that fasting was no more meritorious than eating with gratitude and that there was no difference in rank between chaste virgins and wives. Jovinianus warned the ascetic against arrogance. The church father Hieronymus polemicized against him, who was convinced that the ascetic way of life was the most meritorious and superior to any other. From this Jerome derived a ranking; he believed that the ascetics would receive a greater reward than the rest of the Christians in the coming kingdom of God .

Special communities

Christian communities classified as heretical by the large church often represented a more rigorous asceticism than the church officials and writers. One of them was the Montanist movement, which emerged in the 2nd century and was supported by the important writer Tertullian . This theologian had alienated himself from the big church because its abstinence practice was too lax for him. Tertullian called for strict asceticism, which included, among other things, the widow's renunciation of a second marriage. He viewed fasting as the atonement that man had to make for Adam's consumption of the forbidden fruit. Adam had forfeited his salvation because of his eagerness to eat, but now as a Christian one can be reconciled with God, who is angry about the original sin of the first human couple and thus all of humanity.

The groups and individuals who were referred to by their ecclesiastical opponents as encratites (“rulers” or “celibate”) or called themselves that were strictly ascetic . In these circles, the ideal of sexual abstinence was so emphasized that marriage and procreation were considered undesirable or at least suspect and, in particular, a second marriage after the death of the first spouse was rejected. The encratites - including the prominent theologian Tatian - were indeed opposed by the church fathers as heretics, but the demarcation from them proved to be difficult, because the encratic ascetic ideal also had numerous followers within the main church, whose convictions hardly differed from those of the non-church encratites . In the Syrian Church in particular, an encratic understanding of asceticism was the dominant doctrine.

In the religious community founded by Marcion in the 2nd century, which was strongly influenced by Gnostic ideas, sexual asceticism was particularly required; apparently some foods were also requested. The basis for this was the rejection of the creator god, the demiurge , whose facilities and products one wanted to avoid as far as possible.

Medieval Catholicism

Despite the emphasis on an ascetic lifestyle in the epoch of the Church Fathers, the terms “ascetic” and “ascetic” were not taken from Greek into Latin or translated. Therefore, as in antiquity, they were not used outside the Greek-speaking area in the Middle Ages. The most general Latin term for asceticism was disciplina , a term that, however, covered a larger field of meaning. The practices were called "exercises" (exercitia) .

In the Middle Ages, as in late antiquity, the main bearer of the ascetic tradition was monasticism. The basis was initially the Rule of Benedict , written in the 540s . The founder of the order Benedict of Nursia personally practiced harsh asceticism, but the regulations in his rule for the Benedictine order are relatively mild compared to the ancient monastic rules of the Greek-speaking world. The moderation in ascetic practice contributed significantly to the success and continued popularity of the Benedictine expression of monasticism.

In some monasteries of the Franconian Empire and the Longobard Empire, the more ascetic rule of the founder of the Irish monastery, Columban von Luxeuil († 615), applied in the early Middle Ages , but the Benedictine rule finally prevailed in Western Europe. In Irish monasticism, which also spread to the mainland, the tendency to asceticism was particularly pronounced. The Irish ascetics also included numerous wandering monks and hermits . The pilgrimage (Latin peregrinatio ) far from home, the emigration to foreign countries and lonely islands was considered by the Irish as a hard and therefore particularly valued form of asceticism.

The literature from which the early medieval ascetics of Western and Central Europe drew significant suggestions included, in particular, depictions of the life and teachings of the ancient desert fathers. The church father Johannes Cassianus , who had lived in the Egyptian desert and then founded a monastery in Marseille in the early 5th century , played a central role as a mediator of the ascetic ideas of the eastern church monks. In addition to his widespread writings, Latin translations of Greek-language literature paved the way for the spirituality of oriental monasticism.

The inclusions or recluses practiced an increased form of asceticism . This is the name given to men and women who let themselves be locked up or walled up in separate cells , often attached to a church , which they then usually did not leave until their death. The confinement was carried out in a ritual act. Some inclusions lived in the area of a rural monastery, others in the cities. Because of their demanding asceticism, the population showed them special respect; they were very much valued as advisors.

The numerous reform movements of medieval monasticism and the founding of new orders aimed to return to an idealized earlier state and to regain lost standards of value. The struggle of the reformers was directed against the secularization of monastic life. In practice, this meant a new sharpening of asceticism, the weakening of which was lamented as a phenomenon of decline. In this regard, the Benedictine Rule was invoked within the Benedictine order, which must be followed precisely. Such reform impulses included Benedict von Aniane († 821), the Cluniac (10th – 12th centuries) and the Cistercians (from 1098). The Carmelite Order, founded in the 12th century, was based on the principle of ascetic hermitism. The mendicant orders founded in the early 13th century - Franciscans and Dominicans - as well as the community of Augustinian hermits , which arose somewhat later, were also strongly ascetic from the start . With their ideal of poverty (lack of possessions, livelihood through alms) they renewed the way of life of the old wandering basketball. Differences of opinion about the question of how radically the Franciscan ideal of poverty should be realized led to the poverty struggle and shook the order lastingly.

The Order of the Carthusians , which was established in the late 11th century and is still in existence today , has placed particular emphasis on ascetic practice since its foundation. It experienced its heyday in the late Middle Ages . The Carthusian settlements, the Kartausen , combine elements of monastic and hermitic life. The monks and nuns live in the monastery complex of the Charterhouse in separate cells, designed as small individual buildings, in which they also eat their meals; meals are only shared on Sundays and public holidays. Characteristic of the Carthusian monks is the seldom interrupted silence. Their asceticism includes working in the cell, meager eating and strict fasting; Meat food is prohibited.

In addition to abstinence, there were also widespread forms of asceticism in the sense of mortification . The ascetic inflicted severe pain and also wounded his body. On the one hand this was an exercise of penance, on the other hand it was also a means of killing off physical desires. An early and very famous role model for this was Benedict of Nursia. Pope Gregory the Great tells about him in his influential work Dialogi that the devil tempted Saint Benedict by presenting him with the image of a beautiful woman. Then the saint threw himself naked in a thorn and nettle thicket and rolled in it for a long time until his whole body was wounded. With this he put out the tempting fire inside forever. Both clergy and laypeople used a variety of methods of self-torment, in particular scourging ( whipping ) was used (self-flagellation). In the hagiographic literature, the very popular narratives of the lives of the saints, such practices have often been cited and well described as notable achievements. Public self-flagellation was practiced in the late Middle Ages by the flagellants (" flagellants ").

Modern Catholicism

In the early modern period , orders were repeatedly split into a milder and a stricter, more ascetic direction (“observance”) or new orders were founded because of dissatisfaction with the secularization of existing orders. In the 16th century the Franciscan order split into the Minorites and the stricter "Observants" ( Ordo Fratrum Minorum ). The Capuchins , who were particularly ascetic, split off from the Observants . In the Carmelite order a "milder rule" was introduced in the 1430s, which provoked internal disputes and was rejected by part of the community. One of Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross initiated reform movement led in the late 16th century to separate the " Barefoot " (barefoot) Carmelites of the "shod", the followers of the old observance. In the 17th century the reform branch of the Trappists ("Order of the Cistercians of the Stricter Observance") was formed in the Cistercian order.

In the course of the Counter Reformation , Ignatius von Loyola , the first general of the Jesuits , designed the retreats (“spiritual exercises”), which were largely completed in 1540 and printed in 1548 with papal approval. According to the author's intention, this is actually a collection of materials, directives and suggestions for spiritual teachers who give their students exercises, not a self-study text for the practitioner. According to the introduction, the aim of the ascetic exercises is to remove all "disordered attachments" from the soul. In their full form, the retreat lasts four weeks. During this time, the practitioner does not devote himself to anything else.

In the fifties of the 17th century, the term theologia ascetica ( ascetics ) was incorporated into Catholic theological terminology. This means the theological reflection on ascetic endeavors. Today the term is rarely used; ascetics is integrated into “spiritual theology”.

In the Catholic theological literature of the 19th and 20th centuries, high esteem for asceticism was often expressed. Manuals and textbooks were published which were specifically dedicated to this topic, including the two-volume Dictionnaire d'ascétisme published by Jacques Paul Migne from 1853 to 1865 . In the first edition of the Lexicon for Theology and Church in 1930 the author of the article on asceticism defined it as “fighting everything in us that stems from sin and leads to sin, suppressing all dangerous natural forces in us, everything sensual and selfish , [...] also some voluntary renunciation of what is permitted, according to the principle of attack as the best defense, which is also valid for instinctual life ”. In the period 1937–1995, the Jesuits in Paris published a comprehensive reference work, the sixteen-volume Dictionnaire de spiritualité. Ascétique et Mystique .

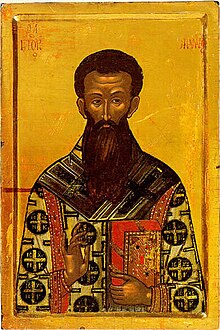

Orthodox churches

In the Orthodox Churches , monasticism sets the tone with regard to asceticism. The monk Maximus the Confessor (Maximos the Confessor, † 662) is one of the authoritative theologians who described the ascetic life . The practices of asceticism are particularly strongly influenced by the aspects that are in the foreground in monastic life: silence, loneliness, waking and fasting. In addition, emphasis is placed on a connection with a spiritual “beauty”. The Russian Orthodox religious philosopher Pawel Alexandrowitsch Florensky (1882–1937) particularly emphasized this aspect . He found that asceticism did not produce a “good” but a “beautiful” personality.

As a spokesman for a religious renewal movement, Florensky, like the influential theologian Sergei Nikolajewitsch Bulgakow (1871-1944), defended the ascetic tradition from which the answer to increasing atheism was to come. Both emphasized the social relevance of the ascetic attitude rooted in Russian popular piety in view of the anti-traditional sentiments of the Western-oriented intelligentsia in pre-revolutionary Russia of the early 20th century. This view was widespread among Orthodox thinkers.

A specifically orthodox form of ascetic practice is hesychastic prayer. This is a prayer practice that was widespread among Byzantine monks as early as the Middle Ages . Its most influential proponent was the theologian Gregorios Palamas († 1359), one of the highest authorities of the Orthodox churches. Hesychastic practice includes body-related instructions such as concentrating on the core of the body and regulating the breath. According to the Hesychast understanding, this is not the mechanical application of a technique aimed at bringing about spiritual results and thus forcing divine grace. Rather, the purpose of the body-related regulations is only to generate and maintain the concentration that is essential for the exercise of prayer. An essential part of the hesychastic experience are light visions of the monks. The praying hesychasts think they perceive a supernatural light.

Reformed churches

For Martin Luther his gradually developed fundamental criticism of monastic asceticism, which he had previously practiced himself diligently, was an important starting point on his path to the Reformation . He saw the ascetic practices of the monks as an expression of a hidden arrogance, namely the (at least implicit) idea that such efforts represent merit and that one can achieve a special degree of holiness with them. Luther condemned such an attitude as righteousness to work .

The Swiss Zwinglians and above all the Calvinists practiced a disciplined lifestyle with ascetic traits from the beginning, which later also various beliefs based on or influenced by Calvinism adopted. Formative elements are the appreciation of hard work, affect control and the rejection of worldly pleasures and consumption that is viewed as luxurious. Devotion to the enjoyment of earthly goods is regarded as the deification of the created and thus as idolatry . Calvinistic asceticism differs from traditional Christian asceticism primarily in that it does not include efforts with which the believer wants to improve his prospect of eternal salvation. This motive is omitted, since according to the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, the bliss or damnation of every person is irrevocably fixed from the outset and in no way depends on merit. The desired ascetic way of life is therefore not a means of gaining salvation, but only a sign of being chosen .

Pietist groups of the 17th and 18th centuries showed themselves to be receptive to ascetic ideas. Asceticism was affirmed as overcoming the world. In this sense, for example, the influential preacher and writer Gerhard Tersteegen (1697–1769) expressed himself , who pleaded for a willing renunciation of all "earthly lust". In the liberal Protestant theology of the 19th and early 20th centuries, however, a decidedly anti-ascetic tendency became noticeable: theologians such as Albrecht Ritschl and Adolf von Harnack combined the criticism of asceticism with its delimitation from Catholicism and Pietism, and Julius Kaftan stated, who Protestantism did away with asceticism as a "foreign body".

Islam

In Islam , asceticism is called zuhd زُهْد(“Renunciation”, “renunciation”), the ascetic as zāhid . This linguistic usage was still uncommon in pre-Islamic times and does not appear in the Koran either; it was only established in the 8th century. What is meant is renunciation of worldly interests in order to concentrate fully on the expected future in the hereafter (āḫira) or on God. For this, the ascetics refer to the Koran, which contains numerous references to the insignificance of this world ( dunya ) and the transience of this life. They understand renunciation to mean turning away from a previously coveted object, which is at the same time turning towards something better recognized. The one who renounces not only gives up externally what he renounces, but also no longer desires it. Muslim ascetics refer to everything that distracts from God and separates people from God as “this world”. So what is meant is not the whole world of sensually perceptible objects as such, but “this world” is only the totality of that which is not related to God and is not taken and used for his sake.

With regard to worldly goods, zuhd means limiting yourself to the bare minimum of food, clothing and all possessions. On the spiritual level it is about renouncing superfluous talking, looking and walking (all kinds of preoccupation with things that are none of your business) as well as freedom from longing for people.

A pronounced asceticism was already practiced in the 8th century in the environment of the Basrian Qadarīya . As a sign of renunciation one ran around in rags or dressed in wool, because woolen clothing was worn by beggars and was considered a sign of humiliation. This form of asceticism was demonstratively non-bourgeois, anti-conventional and provocative. A center of communal ascetics was the island of ʿAbbādān in the mouth of the Karun , on which the present-day Iranian city of Abadan is located.

The most famous early ascetics in Basra were the influential scholar and preacher Hasan al-Basrī († 728) and the teacher of the love of God Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya al-Qaisiyya († 801), who are considered to be the pioneers of Sufism . Sufis are the representatives of an ascetic movement that developed a new ideal of piety in the 8th and 9th centuries that is still followed today. Her demeanor and teachings were found offensive by traditionalists and continue to be highly controversial among Muslims. Sufism, whose name is derived from the typical woolen clothing of the ascetics, calls for particularly consistent renunciation. It is one of the most important cultural and historical phenomena in the Islamic world and has a strong influence up to the present day. For the Sufis, renunciation of the world is a central aspect of religious life, but, in contrast to other ascetic traditions, they place their practice in the service of a radically theocentric piety that consistently rejects everything non-divine: They criticize the turning to the hereafter ( heaven ), there heaven as something created is different from the Creator and therefore distracts from him just like the earthly. Therefore one should not care about this world or the hereafter, but only about God.

The ascetic endeavors of the Sufis are determined by their conviction that the instinctual soul (Arabic nafs ) is a foolish, vicious and shameful entity in people whose wickedness one has to see through and whose covetousness one has to resist if one wants to find access to God. Their malevolent properties are vividly described in Sufi literature and traced back to their addiction to pleasure. The NAFS is portrayed as man's worst enemy. Therefore it is demanded that one should despise it, beware of it, allow it no comfort and rest, punish it and renounce it. The pleasures of this world permitted by religion are also rejected as fateful concessions to desire. The fight against the NAFS does not stop until death .

In Sufism, in addition to combating the instinct to possess, the instinct of validity, the desire for a position of power, for fame and recognition is very important. In ascetics, this instinct shows itself in striving for praise for their piety and for ascetic achievements and in enjoying the popular esteem associated with their status. Sufism literature strongly warns against this. To avoid the associated dangers, Sufis are advised to withdraw. For example, you can avoid celebrity by moving to another location. Consistently avoiding unnecessary talking is also helpful.

The practice of asceticism for some medieval Sufis also included long-term, hard physical exercises such as sleep deprivation, fasting and long standing in prayer. Extreme exercises were, however, controversial among theologians and also in ascetic circles. The principle of renunciation was also subjected to criticism among the Sufis; He considered the "renunciation of renunciation", the attitude of the one who "forgets" to renounce, because he no longer needs to focus his attention on it.

philosophy

Interpretations and evaluations from the 15th to the 19th century

From the 15th century, writers appeared among the Renaissance humanists who defended Epicureanism and considered pleasure ( voluptas in Latin ) to be the greatest good. In doing so, they reversed the order of values prevailing at the time. In particular, proponents of pleasure turned against the way of thinking of a religious current that, since the late 14th century, propagated a strict asceticism based on the model of the church father Jerome. They criticized the ascetic avoidance of pleasure and affirmation of pain as unnatural. Lorenzo Valla was a prominent spokesman in this direction .

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), the founder of utilitarianism , advocated the “principle of utility”, according to which every action should serve the goal of maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering. He regarded the principle of asceticism as that which was absolutely opposed to the principle of utility. It consists of approving actions when they serve to diminish happiness and rejecting them when they increase happiness. Asceticism is advocated by both moralists and superstitious religious people, but for different reasons. The motive of the moralists is the hope to find recognition, so a pursuit of pleasure (pleasure) . For religious people, the motive is their fear of divine punishment, i.e. the desire to avoid suffering. Thus, both actually followed the principle of utility. The educated tended to a moral-philosophical foundation of asceticism, simple minds to a religious one. The origin of the ascetic principle lies in the idea or observation that certain pleasures, under certain circumstances, cause more suffering than pleasure in the long term. From this a rash general devaluation of pleasure and appreciation of suffering was derived.

Immanuel Kant differentiated between two types of asceticism: the "moral ascetics" as an exercise of virtue and the "monk ascetics", which "goes to work with self-torment and flesh crucifixion out of superstitious fear or hypocritical disgust for oneself". He advocated moral asceticism, but only if it was practiced “with pleasure”; otherwise she would have no intrinsic value and would not be loved. The monk saskese, on the other hand, does not aim at virtue, but "enthusiastic sanctification". The ascetic punishes himself, and this cannot happen without a secret hatred of the commandment of virtue.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel opposed a renunciation that demanded "in the monastic imagination" of humans "to kill off the so-called instincts of nature" and "not to incorporate the moral, reasonable, real world, the family, the state" . Hegel countered such asceticism with a renunciation that he considered right. This is "only the moment of mediation, the point of passage in which the merely natural, sensual and finite generally disposes of its inappropriateness in order to allow the spirit to come to higher freedom and reconciliation with itself".

Arthur Schopenhauer accepted the Far Eastern and Christian concept of asceticism. In asceticism he saw the negation and mortification of the will to live. The rejection of the will to live is the result of the insight into the "nothingness and bitterness" of life. The ascetic wanted to break off the sting of lust; he refuses the satisfaction of his desires, so that the sweetness of life does not "excite the will again, against which self-knowledge has revolted". Therefore, he likes to endure suffering and injustice, because he sees in them opportunities to make sure of his world negation. Philosophical reflection is not required for this; An intuitive, immediate knowledge of the world and its essence is sufficient for ascetic practice, and this alone is what matters. It is therefore a matter of indifference whether the ascetic is a philosopher or “full of the most absurd superstition”; only renunciation as such is essential.

In Friedrich Nietzsche's works , in addition to the dominant, very negative assessment of asceticism, there is also a neutral and a positive one. While he strongly condemned exercises to kill off the instincts and sensuality, because they weaken the vital force, he advocated "asceticism" as "gymnastics of the will". He wanted to "naturalize" asceticism again by replacing the "intention to negate" with the "intention to reinforce". He devoted most of his attention to fighting an asceticism which he considered depraved and unnatural. In the third part of his work Zur Genealogie der Moral , Nietzsche asked the question “What do ascetic ideals mean?” In 1887 he answered them one after the other with regard to the artist (with a special focus on Richard Wagner ), the philosophers (with special consideration of Schopenhauer) and Priest and finally turned to the relationship between asceticism and science. He assumed the artists that asceticism meant nothing to them because they did not take it seriously. He accused the philosophers of being blind to the ascetic ideal because they themselves lived from it and therefore could not see through it. The priests are the designers, administrators, mediators and beneficiaries of the ascetic ideal, for them it is a means of power. Science, insofar as it has an ideal at all, is “not the opposite of that ascetic ideal, but rather its most recent and noble form itself”. Nietzsche came to the conclusion that the ascetic ideal owes its attractiveness to the meaning it gives to suffering; the ascetic world negation is a "will to nothing" and people would rather want nothing than not want it.

In his introduction to moral science in 1892, Georg Simmel traced the emergence of the ascetic ideal back to the basic experience that altruistic action is often only possible by giving up and fighting down egoistic drives. According to Simmel's explanation, the value of the positive moral act has been transferred to its frequent accompaniment of sacrifice and the fighting down of immorality. "A shadow of pain, sacrifice and overcoming" was attached to the idea of moral activity. In ancient philosophy, suffering was seen as something indifferent to go through; only in Christianity was it raised to an ethical value. The process of appreciating suffering and bearing then continued in the same direction, until finally the positive purpose of sacrifice receded and renunciation and the infliction of pain appeared as a moral end in itself and a merit in itself. When renunciation became value in itself, the ascetic standpoint was reached. The moment of hardship, of inner resistance, had become the idea of special merit. The value of an end end has been transferred to the means required for it. Simmel illustrated this process with the examples of fasting and chastity. In both cases the renunciation originally served the purpose of promoting the elevation of the spirit to higher goods; later it became the yardstick of perfection. Another aspect for Simmel is the "enhancement of personality" that results from overcoming resistance; defeating an inner resistance creates a feeling of spiritual expansion and strengthening of power.

Analyzes in 20th Century Philosophy

Max Scheler differentiated between “morally genuine asceticism”, in which a “positive good” is sacrificed for the sake of a higher value, and the “pseudo-asceticism of resentment ”, in which what one denies oneself is devalued at the same time or beforehand and for annulled.

Arnold Gehlen assigned a threefold meaning to asceticism: as a stimulant ( stimulant ), as a discipline and as a sacrifice. It has a stimulating effect, because with the "constriction of the attack surfaces for external stimuli" and concentration on a few motives, an inner relief is associated and intuitive powers and happy energies are released. The inhibitory performance of asceticism brings with it a concentration and an increase in the intensity of the feeling of presence and self-power. This explains , for example, Maximilien Robespierre's ascetic attitude . If such asceticism is used for social purposes, it shows itself as a discipline and gives "a way to dignity for everyone". The third meaning of asceticism is religious: sacrifice. The entire life orientation of the religious ascetic is "geared towards keeping the contact with suffering, and indeed in the conviction that it is in line with the 'whole' of existence". Concentrating on one's own salvation and that of others must, like any ethical absoluteness, release "a latent aggressiveness of a high degree". Because of the religious prohibition of violence, this cannot discharge to the outside world and must therefore turn against the religious ascetic himself. His self-sacrifice is his “processing of the masses of aggression”.

Michel Foucault described asceticism as an exercise in oneself, as a kind of one-on-one struggle that the individual wages with himself without needing the authority or presence of another. For Foucault, the starting point of his extensive study of the history of sexuality was the question of the relationship between asceticism and truth. From his perspective, successful asceticism is the test criterion of practical truth, of the assumptions that the individual considers true and correct. It is a way of tying the subject to the truth. The hearer sees in him the truth that the speaker says. Asceticism turns speaking true into a way of being of the subject. Truth becomes possible only through asceticism. According to a definition given by Foucault in a lecture in 1981/82, philosophical asceticism is a certain way in which the subject of true knowledge constitutes itself as the subject of right action and settles itself in a world. This subject gives itself a world as a correlate, which is perceived, recognized and handled as a test.

Foucault analyzed the “technologies of the self” that humans use in order to acquire knowledge about themselves and to change in a desired sense. He compared the self-techniques - including asceticism - of Platonic and Stoic philosophy with those of late antique Christianity and contrasted these ancient concepts with modern moral concepts. According to his presentation, both the pagan philosophers and the Christian theologians of antiquity emphasized the maxim "Take care of yourself", their concern was the concern for yourself. This is where their approach differs from the morality that is dominant today. Today selflessness is demanded and thus the self is rejected; one looks for the rules for acceptable behavior in relationships with others. In contrast, for the ancient ascetics from the epoch of Hellenism, care for oneself was a universal principle that requires lifelong effort and is the prerequisite for meaningful social activity. The Stoics wanted to grasp the truth through self-inquiry and transform it into a principle of action. For them, asceticism did not mean renunciation, but a self-control that is achieved through the acquisition of truth. Believing that observation and self-transformation were essential, the philosophers agreed with the Christian ascetics, but the Christians did so from a different point of view and with a different goal. With them one should recognize one's sins - especially the sexual ones - in order to then confess them. Thus the believers were forced to "decipher themselves with regard to the forbidden" and to renounce their own self in an obedient relationship. This renunciation asceticism made repentance a way of life. Her goal was not to create identity, but to break with it and turn away from the self. From this arose the Christian moral tradition, the legacy of which, according to Foucault's analysis, is the modern social morality of selflessness. With its disregard for the self, modern morality practices its own form of asceticism.

The initial question from Peter Sloterdijk is: "Where do the monks go?" He stated that an "ascetic belt" stretched across the earth from India to Ireland, the "scene of a tremendous secession from the standards of cosmic normality". With his book Weltfremdheit , Sloterdijk wanted to do preparatory work for an anthropological derivation of the possibility of flight from the world. According to his interpretation, the early Christian monks oriented themselves on the "desert principle". Hermitism and community asceticism of the desert monks were necessary aspects of the "transition of pagan societies to imperial monotheism". Only in the desert could “the monarchy of God develop into the new psychagogical law”. The monks wanted to weaken the world as the third separating God and man to the point of annulment; the meaning of their way of life was the "attack on the third in general". This was combined with a “ metaphysical alert”, an unprecedented fight against sleep - “being awake is everything”. The contrast to this is the modern western civilization. For Sloterdijk it is based on the rejection of the desert principle and on the “absolute establishment of thirdness”: “The modern age is the age in which the world is everything that may be the case.” Modernity means “diversion of flight into the world even as promised, coming, better ones ”.

sociology

Emile Durkheim

Émile Durkheim dealt in his 1912 study The Elementary Forms of Religious Life with asceticism. He saw it as a phenomenon of "negative cult", a system of renunciation based on religious prohibitions. According to Durkheim's model, the negative cult contains only the inhibition of activities, but nevertheless has “a positive effect of the highest importance on the religious and moral nature of the individual”. When man gets rid of everything that is profane in him and withdraws from worldly life, he can overcome the barrier that separates the sacred from the profane and come into close contact with sacred things. This is the only way to gain access to the positive cult, to the practice of bilateral relationships with the sacred. He is then no longer what he was before, he is no longer an ordinary being. Whoever has purified and sanctified himself by removing himself from the profane is on the same level as the religious forces. Forms of such asceticism are, for example, fasting, night watch, seclusion and silence.

According to Durkheim's account, any observance of a religious prohibition which compels one to forego useful things or ordinary activities has to a certain degree an ascetic character. Since every religion has a system of prohibitions, each is more or less ascetic; they differ only in the extent to which this approach is developed. Asceticism in the true sense of the word is when the observance of restrictions and renunciation develops in such a way that it becomes the basis of a real life discipline. The system of prohibitions can even expand so that it finally encompasses all of existence. Then it is no longer subordinate to this as preparation for a positive cult, but comes first. Durkheim calls this "systematic asceticism". Anyone who is a “pure ascetic” in this sense earns a reputation for special holiness. In some societies he is considered equal to or superior to the gods.

Since abstinence and privation are inevitably connected with suffering and the detachment from the profane world is violent, the negative cult must cause pain. This experience has resulted in a positive evaluation of such pain. They are expected to have a sanctifying effect. This has led people to artificially create pain in order to gain the powers and privileges that one hopes for from the negative cult. The pain itself has become the content of ascetic rites and is understood as a kind of distinction. By overcoming pain, the ascetic gains extraordinary powers. He gets the impression that he has risen above the profane world and has achieved a certain degree of domination: “He is stronger than nature because he has silenced it.” This principle is exemplified by the life of the great ascetics, theirs Role model spurs effort. They form an elite that puts the goal in front of the crowd.

According to Durkheim's findings, asceticism does not only serve religious goals; rather, religious interests are "only the symbolic form for social and moral interests". Not only do belief systems call for contempt for pain, but also society, which inevitably demands constant sacrifices from individuals. On the one hand, society increases people's strengths and lifts them above themselves, on the other hand, it constantly “rapes” their natural desires. Hence there is an asceticism "inherent in every social life and designed to survive all mythologies and all dogmas". In this secular asceticism Durkheim sees the "purpose of existence and the justification of what the religions of all times have taught".

Max Weber

Max Weber dealt with the issue of asceticism in many of his writings, with the modern situation in the foreground. He dealt with it from both a religious and economic sociological point of view. In his work, The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism , he presented his view in detail. It essentially agrees with that of his friend Ernst Troeltsch .