Cave temples in Asia

Cave temples are underground sacred buildings carved into the rock or placed in a natural cave . Cave temples and monolithic rock temples carved out of the stone are a form of early natural architecture and rock construction , a construction technique in solid rock that is closely related to sculpture . The most extensive artificially created cave temple complexes (subterranea) arose in India , where about 1,200 systems are occupied, and in the neighboring regions of Asia .

The basic shape of the cave temples in Asia has been around since the second century BC. BC in western India from the predecessor of the mountain hermit of the world-turned Shramana movement ( Sanskrit , m., श्रमण, śramaṇa , Pali , m., Samaṇa , mendicant monk), a free-standing hut or cave as a dwelling for ascetics . Central design principles are presumably derived from the example of wooden outdoor structures that are no longer preserved today.

Cave temples spread along the long-distance trade routes from South Asia to Central and East Asia. In Southeast Asia, instead of artificial caves, mostly natural caves were used as underground sanctuaries . The UNESCO World Heritage List includes numerous cave temples in Asia, including Ajanta , Elephanta , Ellora and Mamallapuram in India, the Mogao , Longmen and Yungang Grottoes in China, Dambulla in Sri Lanka and Seokguram in South Korea.

In addition to the Asian lines of development, cave temples and other, sometimes much older rock structures also appear in other ancient cultures such as Egypt , Assyria , the Hittite Empire , Lycia and the Nabataeans .

Forerunners and rock architecture worldwide

Already in prehistoric times, caves served people as refuge, burial or cult sites. The marking of the cave changed it from a fascinating place to a holy place. During the later period of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, ritual inauguration, permanent marking (for example in the form of cave painting ) and regularly repeated rites were part of ritual use. Prehistoric rock art can be found in around 700,000 locations in 120 countries and includes more than 20 million figurative representations.

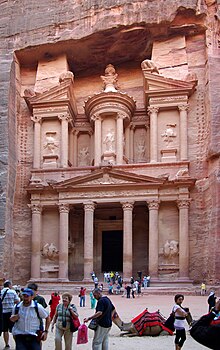

Since the time of the early advanced civilizations , artificial rock structures appeared as a new construction method in North Africa, Small, Middle East, Central, South and East Asia. They served as a place of residence, protection and depot ( Cappadocia in today's Turkey ), as grave caves ( Petra in Jordan ) or as temples and monasteries (India). Rock structures of the pre-Columbian civilizations of America are occasionally referred to as cave temples, for example Kenko with a Puma altar near Cusco or the Cuauhcalli temple near Malinalco in Mexico State (16th century AD).

Among the most striking complexes worldwide are the monumental rock temples of the Egyptian pharaonic empire , the temples of Abu Simbel (here also under the name Speos ). The Great Temple of Ramses II in Abu Simbel on the western bank of the Nile was built around 1280 BC. The temple complex, which includes a sanctuary and various chambers, was completely cut into the rock massif.

Other rock structures are preserved mainly in Asia Minor and the Middle East. Hittite sanctuaries were established in the 15th to 13th centuries BC. Carved out of the rock in Yazılıkaya in today's Turkish province of Çorum . In the 5th century BC The Lycians built hundreds of rock tombs in southern Anatolia (for example near Dalyan , Muğla Province, Turkey) . The Nabataeans also fought in Petra (Jordan) between 100 BC. And 150 AD temples and tombs in the rock. Christian cave settlements with extensive residential complexes and rock-hewn churches were created in Göreme in the Turkish Cappadocia (since the 4th century AD), in Matera in southern Italy (early medieval) and in the 12th to 13th centuries in Lalibela in northern Ethiopia.

Buddhist cave temples in India

Caves in early Buddhism

Buddhist cave temples represent an underground variant of the Buddhist monastery and temple complex , which goes back to the habitation of the ascetic Shramana movement since the epoch of the Upanishads (8th to 7th centuries BC) as well as to ancient Buddhist meditation sites. The historical Siddhartha Gautama retired as a young wandering basket before attaining enlightenment for meditation in caves (according to tradition, for example in the Dungeshwari cave near Bodhgaya in Bihar). As a Buddha he occasionally used a cave near Rajagriha as a meditation site, such as the Pali Canon , an early record of the Buddha's discourses from the 1st century BC. Chr., Handed down ( DN , chap. 16,3, chap. 21 and 25). This cave was identified by the Chinese pilgrim monk Faxian in the 5th century AD as Pippala Cave on Mount Vebhara (Vulture Mountain).

The Pali Canon names natural caves (Pali, kandara ) as common places of retreat for members of the Buddhist order ( MN , Ch. 27, 38, 39 and more), who were able to meditate there largely shielded from sensory stimuli. Also the First Buddhist Council , which was held shortly after the Buddha's death in the 5th century BC. According to Buddhist tradition, it was carried out at Rajagriha in a hall in front of the Sattapanni cave on the north slope of Vebhara Mountain. In view of the principle of "homelessness" of the Buddhist order, the natural protective function of caves played an important role in the development of the Buddhist cave temples. Cave temples offered better protection against the weather than the self-built free-standing rain huts made of bamboo and mats, which served as refuges during the rainy monsoon season and were demolished again after the monsoon ended.

The era of Emperor Ashoka

The actual construction of artificial cave temples from "grown" rock was only initiated in the era of Maurya Emperor Ashoka , who in the 3rd century BC. Founded corresponding, initially still quite elementary facilities for the ascetic community of the Ajivika (for example the Lomas Rishi Cave near Barabar ). The Buddhists developed these preforms into elaborate centers of monastic life with increasingly rich relief decorations . With the support of wealthy Buddhist laypeople, they created the basic form of Indian rock architecture during the centuries before and after the birth of Christ, which spread widely along the trade routes during the following millennium. A connection between the older Egyptian, Hittite or Lycian rock architecture of the west and the younger, considerably more numerous Indian rock structures has not yet been clearly proven.

Origin context

The emergence of the Indian cave temple complexes took off after cautious beginnings in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. A considerable upswing with the growing prosperity of the handicraft classes of western India. One of the main reasons for this was the increased trade with the Roman Empire from the first century AD onwards, especially on the Indian craftsmen ( Skt. , M., शूद्र, shudra ) who formed the low castes within the impermeable Brahmin society Buddhism, because of its appreciation, also attracts lay professors as fully valid candidates for healing, because of the factual devaluation of caste membership (Skt., वर्ण, varnas ) and the rejection of costly Vedic sacrificial rituals.

In contrast to Hinduism , Buddhism and its monastic communities were primarily based on urban culture. Influential city merchants' guilds donated the money to build and equip entire monasteries, as the foundation inscriptions show. The monasteries in turn financed the local traders through loans. In addition, the founding of temples in Hinduism and Buddhism is one of the spiritually meritorious acts (Skt., Puṇya ). The competition between different craft guilds for the design of their foundations led, particularly during the period of the Gupta dynasty , which ruled over northern and central India from 320 to 650 AD, to a considerable boom in Indian rock building, sculpture and painting Works in the later often orphaned cave temples have survived.

The cave monasteries, which were given to the religious as permanent loan , were supplied by the Buddhist lay supporters of the surrounding villages and settlements, who offered the begging monks food, medicine and clothing. The daily routine in the Buddhist monasteries was strictly structured. After waking up before sunrise, the monks rose with a song or the recitation of an edifying verse, cleaned the monastery and procured the necessary drinking water. The daily routine also included flower donations in a joint gathering, a begging round to buy food, a meal, meditation exercises, text study and attending teaching presentations.

Structural structure and engineering

Strictly speaking, early Buddhist rock architecture is not a temple in the traditional sense of complexes, "which appear to be comparable in terms of their structural form (monumentality, stone construction) or their religious function (home of a god or goddess)". Early Buddhism did not know of any sanctuaries and buildings dedicated to a divine power. Despite the primary function of Buddhist rock structures as a monastery complex, the general designation cave temple has established itself equally for Buddhist and Hindu underground sacred buildings. In the case of Buddhist rock structures, it ties in with the temple-like structure of the Chaitya Hall and its orientation towards a holy of holies .

The Buddhist cave monasteries and cave temples of South, Central and East Asia are characterized by two central building types: buildings that house or enclose Buddhist sacred objects and buildings of monastic life.

- The first building type includes the three-aisled, basilica- like prayer hall (Chaitya Hall), which serves the meritorious transformation of the bell-shaped central sanctuary ( stupa ).

- The second design includes the meditation and living halls of the Buddhist monks ( Vihara ) and their ancillary facilities.

Common structural elements in the outer area of the Buddhist temple and monastery caves are portico (vestibule), side chapels, pillar verandas, courtyards and open stairs.

The Chaitya or prayer hall (from Skt., Caitya-gṛha ; Pali, cetiya , sanctuary) stands in the center of the Buddhist temple complex. The three-aisled Chaitya Hall is separated by two rows of columns into a central nave , the ceiling of which is designed as a barrel vault with a wooden or stone rib ceiling , and two aisles. The hall is used to accommodate a mostly richly decorated reliquary (Skt., स्तूप, stūpa ; Pali, thupa , hill, originally in the sense of a burial mound), which is surrounded by a walkway for ritual bypassing. An elaborate wooden facade with one or more gates was originally placed in front of the Chaitya Hall . In interaction with a horseshoe-shaped window above the entrance gate of the hall, the wooden facade ensured that the stupa niche in the semicircular apse at the end of the hall was wrapped in atmospheric light effects.

The monastery rooms are located in the vicinity of the Chaitya Hall. The living areas of the monks (Skt./Pali, n., विहार, vihāra , place of residence, domicile) include, in addition to common rooms, a number of narrow living cells (Skt., Bhikṣu-gṛha ) for two people each. The monk cells are arranged around a courtyard or a central columned hall (Skt., मण्डप, maṇḍapa ). Other elements of the monastery building are cisterns , magazines and other side rooms for practical purposes. The cave monasteries of Mahayana Buddhism, the second main class of Buddhism, which emerged between the 5th and 8th centuries AD, contain richly decorated rows of columns as well as cult picture chapels or smaller hemispherical stupas. They are adorned with large murals depicting the life and pre-existences of the historical Buddha. In many cases, the layers of paint that decorated the temple complex over a large area were later worn away by weathering.

In terms of structural engineering, the rock wall was first worked vertically across the width of the planned cave. The façade was then marked and work began on carving into the rock from above. The excavation work was gradual. The top step always reached deepest into the rock. When the rear wall was reached, the ceiling was completed, which meant there was no need for scaffolding. While the stonemasons worked their way down through the rock from above and left out planned columns and sculptures, the facades were completed at the same time. The only tools the stonemasons had at their disposal were a pickaxe, hammer and chisel.

Development towards a monumental building

The development of the cave temples led, in view of the increasing strength of the Vedic-Brahmanic religion, to the expansion of the Buddhist cave temple into a monastery school. Already in Ajanta (caves 6 and 27) a multi-storey cave had been carved out of the stone - probably based on unpredictable wooden monastery buildings. In addition to the Chaitya Hall and the Vihara, there is a large one in Ellora (three-story cave 12, Tin Thal, and Cave 11, Do Thal), Bagh ( no.5 ), Dhamnar ( no.11 ) and Kholvi ( no.10 ) Chapter House (Dharmashala, Skt., Dharma , teaching [Buddhas]; shala , teaching place).

While the Chaitya and temple halls were mainly used for ceremonies such as the Pradakshina (Skt.), I.e. the ritual transformation of the stupa with the intention of acquiring spiritual merit, and the monastery rooms of the Viharas mainly served as meditation and dwelling places, the Dharmashala is with long rows of stone benches designed as a large Buddhist teaching and sermon hall. On one level of the Ellora monastery school, up to 30 listeners, seated in rows between the pillars, could follow the interpretations of a Buddhist teacher.

Distribution in India

So far, about 1,200 Buddhist, Hindu and Jain temple caves are known in India, of which about 1,000 are in the state of Maharashtra , others in Andhra Pradesh , southeast of Maharashtra, and in the northwestern states of Gujarat , Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh . The oldest known cave temples emerged in the context of the Shramana movement around the 3rd century BC. In the later northeastern state of Bihar (eight caves in Barabar, Nagarjuni and Sita Marhi near Rajagriha, today: Rajgir).

Several cave and rock temple complexes with different religious backgrounds, which have been intensively developed for archaeological and tourist purposes, are part of the UNESCO World Heritage list :

- Ajanta (Buddhist, 2nd century BC to 7th century AD, 29 caves), located in the vast Wagora river valley and accidentally rediscovered by a British cavalry officer in 1819,

- Ellora (Buddhist, shivaitisch -hinduistisch, jainistisch, about 6.-12. Century n. Chr., 34 cavities), beaten 2 kilometers in length away from a basaltic rock wall,

- Elephanta on Gharapuri Island near Mumbai (Hindu, 9th to 13th century, disputed dating, four caves), all in the Indian state of Maharashtra,

- The temple district of Mamallapuram on the Coromandel coast near Chennai, Tamil Nadu (Hindu, 7th – 9th century AD, 17 monolithic rock temples), the beacons of which were used by the seafarers of the Pallava dynasty as a navigation aid.

Other Buddhist cave temples in India:

| State | city | Cave temple | Time of origin | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | Kamavarapukota | Guntupalli | 2nd century BC Chr. | |

| Gujarat | Junagadh on the Saurashtra Peninsula , Talaja and others | 1st to 4th century AD | ||

| Madhya Pradesh | Chandwasa | Dhamnar | 4th to 6th century AD | almost 50 caves, a Hindu monolith temple |

| Dhar | Bagh | 5th-7th Century AD | 9 caves, formerly extensive wall paintings | |

| Maharashtra | Aurangabad | Aurangabad Caves | 6th to 7th century AD | 10 caves in two groups |

| Bhomarwadi | Pitalkhora caves | 2nd to 1st century BC Chr. | ||

| Konkan region | Kuda, Karhad, Mahad, Sudhagarh and others | |||

| Lonavla | Bhaja and Karla caves | 2nd century BC BC to 5th century AD | Bhaja: 18 caves | |

| Maval (Kamshet) | Bedsa caves | 1st century BC Chr. | ||

| Mumbai | Junnar and Kanheri | 1st century BC Until 2nd century / until 9th century AD | 150 caves and at least 109 caves | |

| Mumbai ( Salsette ) | Mahakali caves (also: Kondivita caves) | about 20 caves in basalt rock | ||

| Nasik | Pandu Lena (Pandavleni) | 1st and 2nd centuries AD | 33 caves | |

| Raigad | Kondane Caves | 1st century BC Chr. | ||

| Rajasthan | Jhalawar | Kholvi and Binnayaga | 5th century AD |

Hindu cave temples in India

Hindu Counter Reformation

Under the influence of the Hindu bhakti teaching (Skt., F., भक्ति, bhakti , devotion, love), tantric , i.e. esoteric elements had found their way into the Buddhist cave temples. In a Buddhist cave in Ellora (No. 12), the four-armed goddess Cunda is added to the Buddha statues as a new element. The Buddhist temple hall in Aurangabad, cave 7, adapts the spatial narrowness of the Hindu temple and shows a chapel equipped with erotic dance scenes . This far-reaching adaptation to the Hindu formal language was connected with the rise of Hinduism from the 4th century AD. The Hindu "Counter-Reformation" resulting from the weakening of the Indian empires went hand in hand with the development of a vital Hindu rock architecture and finally brought building activity on Buddhist cave temples to a largely standstill in the 7th and 8th centuries AD.

Until the first centuries AD, Hindu temples were built exclusively from non-durable building materials, especially wood and clay. However, the first Hindu cave temples and free-standing stone temples took up the style of their predecessors. Due to the inflow of funds from Hindu donors, Hindu cave temples have been increasingly modeled out of the rock in several Indian regions since the 7th century AD, including in today's Karnataka ( Badami , Buddhist, Hindu, Jainist, 6th to 8th centuries AD ., Four cave temples), Madhya Pradesh ( Udaigiri ), Maharashtra ( Pataleshwar in Pune ), Orissa (Gupetswar) and in Tamil Nadu (see Pallava architecture ). In addition to Elephanta and Ellora in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent, the Hindu Mamallapuram near Chennai in southern India is also a UNESCO World Heritage site. Some Jain temples built at the same time are located in Maharashtra (Ellora), Madhya Pradesh ( Udayagiri and Gwalior) and in eastern Orissa ( Udayagiri and Khandagiri in natural caves).

Classic temple structure

The function of the Hindu cave temples as a sanctuary and ritual site for the performance of a puja (Skt., F., पूजा, pūjā, honoring ), fire and sacrificial ceremonies, recitations and other religious acts led to the development of numerous different forms of construction, in their center consistently the divine stands as an object of worship. Hindu cave temples are also shaped by tendencies that have been developed in the field of outdoor construction. The Hindu temple is spatially divided into Garbhagriha as the main room and Mandapa as the vestibule. The Garbhagriha (Skt., Garbha , mother's womb) is a mostly unlit cult chapel that contains the Holy of Holies, the image of the deity or the linga , a symbol closely related to the Hindu deity Shiva. In front of the Garbhagriha, one or more mandapas are lined up in an axis as entrance or temple halls with column colonnades. The monk cells of Buddhist complexes are omitted in Hindu cave temples.

On the basis of the extensive Hindu cave temples of Ellora in Maharashtra, according to Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke, several central building types of Hindu cave temples can be distinguished that are widespread:

- Buildings that can be derived from a cave veranda with a direct connection to the Holy of Holies (for example in Badami and Ellora),

- Temples that imitate the floor plan of a courtyard house with an inner square column (in Elephanta, Ellora and Mamallapuram) and

- Cave temples that are directly derived from the contemporary Hindu open-air structure (Ellora and Mamallapuram).

Due to the triumphant advance of Hindu temple construction in the West Indies since the 7th century AD, the last variant is of particular importance. Hindu cave temples of the last type of construction largely follow the ground plan of the Hindu outdoor temple structure of the south Indian type with the Holy of Holies (Garbhagriha), temple tower (Skt., विमान, vimāna ), entrance and temple hall (mandapa) and occasionally a small pavilion with the Image of the humpback bull Nandi , the mount of Shiva. A further development of this variant of Hindu cave temples is the Kailasanatha temple, a monolithic rock temple in Ellora. This free-standing rock temple in a rock pit, which is closed to the outside by a monumental two-storey portal structure , is probably the most impressive Hindu rock temple with a side length of 46 meters.

Cave temples in other regions of Asia

Spread over the Silk Road

The extensive Buddhist and Hindu cave temple complexes of ancient India have been imitated in numerous regions of Asia since the second century AD. Buddhism came from India to Central Asia along the long-distance trade routes, particularly the northern route of the Silk Road . In the area of today's Afghanistan , cave temples with Persian influence emerged in and around the Bamiyan valley with its side valleys Kakrak and Foladi ( Koh-e Baba mountains, since the 2nd century AD, around 20,000 caves), near Haibak in Bactria (Hazar Sam, since 2nd century AD, about 200 caves) and at Jalalabad (Haddah, Allahnazar, Baswal, 2nd - 5th centuries AD, 150 caves, Dauranta, since 2nd century AD) . Chr., Kajitulu and Siah-Kok).

The cave temples spread to China via Central Asia , most intensely during the Northern Wei Dynasty in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. In the course of this expansion in a northerly direction, emerged between the 4th and 9th centuries (Northern Wei Dynasty , Sui Dynasty and Tang Dynasty ) along the Silk Road and the basins of the Yellow River and the Yangtze River numerous extensive Buddhist temples ( Dunhuang , Kuqa , Turfan and others), which emancipated themselves from their Indian models.

Structural features

In addition to cult and teaching niches and monk cells, the cave temples emerging along the Silk Road are also characterized by a stupa placed in the center, which is often represented by a square central pillar. This bears Buddhist statues and was ritually wandered around (Pradakshina) by monks and lay Buddhist followers with the intention of collecting salvation. The ceiling constructions of the Chinese cave temples are particularly varied, including ceilings in the shape of an inverted bucket, an octagon or a flat checkerboard ceiling.

In the well-preserved Mogao grottoes , the ceiling fields are often filled with painting and thus embody the cosmological idea of the sky dome. Overall, the Chinese cave temples are characterized by more numerous wall and ceiling paintings than their Indian models. In the cave temples of Kizil and in Bamiyan , the popularity of the “ lantern ceiling ” is striking , a central ceiling area that is filled with squares that decrease in size towards the top.

The interior of Central and East Asian cave temples is mostly completely covered with groups of figures, reliefs and ornaments carved out of stone. From this rich abundance of figures, larger configurations stand out in niches, in particular the colossal statues of the seated Buddha as ruler of the world and his standing companion figures that dominate in Yungang and Longmen .

Flowering time in Central and East Asia

Numerous cave temple complexes in Central and East Asia have been preserved, including three Chinese sites with UNESCO World Heritage status:

- the Mogao Grottoes or "Thousand Buddha Caves", part of the Dunhuang Grottoes near Dunhuang ( Gansu Province , 4th - 14th century AD, 492 caves preserved), in which a Daoist monk in 1900 around 50,000 discovered old text documents from the 4th to 11th centuries (today partly owned by the British Museum in London),

- the Yungang or "Cloud Ridge Grottoes" near Datong ( Shaanxi Province , 5th / 6th century AD, 252 caves), designed on the model of the Mogao grottoes and with 51,000 statues and wooden shelters from the Year 1621,

- the Longmen or "Dragon Gate Grottoes" near Luoyang ( Henan Province , 5th – 8th centuries AD, 2,345 caves), whose more than 10,000 sculptures were badly damaged during the Chinese Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976.

The total of over 250 Buddhist and quite rare Daoist cave temple complexes throughout China also include:

| province | city | Cave temple | Time of origin | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gansu Province | 50 km southwest of Lánzhōu | Binglingsi | since 5th century AD | 183 caves |

| Wuwei | Tiantishan Grottoes | 6th century AD | ||

| Guazhou (formerly Anxi) | Wanfoxia | since the 5th century AD | 42 caves | |

| 45 km southeast of Tianshui City | Maijishan | since the 5th century AD | 194 caves | |

| Hebei Province | Handan | Xiangtangshan Grottoes | 6th century AD | |

| Henan Province | Gongyi | Gongxian Grottoes | since 6th century AD | |

| Ningxia Autonomous Region | Guyuan | Sumeru | ||

| Shaanxi Province | Binxian | Dafosi | 7th century AD | 107 caves |

| Province of Shandong | Qingzhou | Tuoshan Grottoes | 6./7. Century AD | 5 caves |

| Province Shanxi | Taiyuan | Tianlongshan Grottoes | 6th century AD | 25 caves, over 500 sculptures |

| Province Sichuan | Guangyuan | Huangze si | 6 caves | |

| Tibet Autonomous Region | circle Zanda | Donggar ruins , Piyang grottoes | 200 caves, 1000 caves | |

| Xinjiang Autonomous Region | Turfan near the Taklamakan Desert | Bäzäklik caves | 5th-9th Century AD | 67 caves |

| Kizil and Kuqa | Kizil grottoes | 3rd - 8th / 9th Century AD | 236 caves recorded (Kizil) | |

| Zhejiang Province | Hangzhou | Feilaifeng Rock Sculptures ( Lingyin Temple ) | 10-14 Century AD | over 470 sculptures in limestone |

In other regions of East Asia only a few cave temples exist, including in South Korea ( Seokguram near Gyeongju , 8th century AD, a cave with 37 sculptures, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and in Japan ( Usuki on the island of Kyūshū , 12th century AD, Buddha statues in tuff ). In Japanese , the Buddhist cave temples are called sekkutsu jiin ( 石窟 寺院 ).

Use of natural caves in South and Southeast Asia

The spread of Theravada Buddhism (Skt., स्थविरवाद, sthaviravāda ; Pali, theravāda , school of the elders) ran from northeast and southeast India to South and Southeast Asia. A second stretch of expansion ran across Myanmar in the north . Both strands eventually met with Mahayana Buddhism, which was spreading from the north. The cave sanctuaries of Sri Lanka and the countries of Southeast Asia developed largely independently and mainly took over the stupas, Buddha statues, lavish wall paintings or the atmospheric lighting effects from their Indian counterparts .

While underground sanctuaries in Myanmar or Indonesia, for example , continued to be created as artificial caves in accordance with the Indian and Chinese types, in Southeast Asia, temples were predominantly built in or near natural caves without costly rock construction. These cave temples were furnished with numerous Buddha statues or Hindu deities, other sculptures and elaborate wall paintings. In many cases, these sanctuaries replaced older animist cult and sacrificial sites that existed in pre-Buddhist times (for example Goa Gajah in Bali or Huyen Khong in Vietnam).

This variant of the cave sanctuaries can be found sporadically in other regions, but primarily in Southeast Asia. The Aluvihara cave temple near Matale (Central Province of Sri Lanka, around since the 3rd century BC, 13 caves with murals and Buddha statues) is of particular importance. Under the auspices of King Vaṭṭagāmaṇī Abhaya was the venue for the 4th Buddhist Council of the Theravada tradition. During the council, the teachings of the Buddha, which had been handed down exclusively orally for centuries, were first put down in writing in the form of the Pali canon.

Heavily frequented pilgrimage destinations

Many of the shrines laid out in natural caves are now heavily frequented places of pilgrimage and sacrifice (for example the Pak-Ou caves in Laos or Pindaya in Myanmar, where Buddha statues are traditionally left behind as offerings), places of historical memory ( Dambulla in Sri Lanka, a former refuge of King Vaṭṭagāmaṇī Abhaya), extensive teaching and meditation centers (Wat Suwan Kuha and Pha Plong in Thailand or Pindaya in Myanmar), burial sites (Pak-Ou caves in Laos), art and museum space ( Batu Caves in Malaysia ) or imposing viewpoints with restaurants (Sam Poh Tong and Kek Lok Tong in Malaysia).

Significant examples of sanctuaries in natural caves are:

| Country | City (province) | Cave temple | Time of origin | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | at Padang Bai | Goa Lawah (Bat Cave) | 11th century AD | Hindu, "with thousands of bats that are considered sacred" |

| also facilities in artificial caves near Ubud on Bali | Goa Gajah (elephant cave) | 11th century AD | probably former hermitage of Shivaite hermits; Buddhist caves destroyed | |

| Laos | at Luang Prabang | Pak-Ou Caves (Tham Ting) | 5th-7th Century AD | two caves, just across the Mekong accessible |

| Malaysia | Selangor near Kuala Lumpur | Batu Caves | Hindu | |

| at Gunung Rapat near Ipoh | the great Sam Poh Tong and Kek Lok Tong | there a total of 14 Buddhist and Hindu cave temples in limestone cliffs | ||

| Myanmar | at Hpa-an ( Kayin State ) | Kawgun cave | about 15th century AD | in limestone cliffs |

| Pindaya ( Shan State ) | Pindaya | more than 8,000 Buddha images | ||

| also artificial caves: near Monywa ( Sagaing Division ) | Po Win Daung (Po Win Mountains) | 17th century AD | 947 caves with Burmese information according to 446,444 Buddha statues | |

| Pyin U Lwin | Peik Chin Myaing | hindu-buddhist | ||

| Sri Lanka | Dambulla (Central Province) | Dambulla | since 1st century BC Chr. | 80 caves, largest temple complex in Sri Lanka (2,100 m²), UNESCO World Heritage |

| Thailand | Province of Phang Nga | Wat Suwan Kuha (monkey cave) | two caves in limestone cliffs | |

| Chiang Dao | Wat Tham (= cave temple) Pha Plong | Meditation center | ||

| at Krabi | Wat Tham Sua (Tiger Cave) | Meditation center with over 260 ordained people | ||

| Vietnam | Mountains Ngu Hanh Son (Marble Mountains) near Da Nang | Huyen Khong Cave | formerly Hindu-Buddhist |

Cave temples in modern times

Shifting a tradition

The Arab conquests of the 8th century, the destruction of monasteries and the expulsion of communities of monks and nuns drastically restricted the expansion of Indian cave temples. At the same time, as mendicant monks and nuns, the religious were dependent on a permanent supply of clothing, food and medicine from lay followers. In many cases, however, lay followers had converted to Hinduism in the course of time. With exceptions such as Dhamnar in Madhya Pradesh and Kholvi in Rajasthan, the active use of Buddhist cave temples decreased due to declining funding from ruling houses and surrounding communities. The gradual decline of Buddhism in India brought monasteries and temples to a standstill. Existing facilities were threatened by destruction in the course of renewed invasions by Central Asian powers from the 12th century.

The use of meditation caves remained a living Buddhist tradition beyond the boundaries of individual teaching areas. In late esoteric Buddhism ( Vajrayana ), the Tibetan Kagyüpa school revived the practice of settling down. The tantric master Milarepa , who is considered one of the greatest poets in Tibet, retired as an ascetic yogi in the 11th century , meditating in cool mountain caves for several years and found numerous imitators. One direction of meditation characteristic of the Kagyüpa is the meditation of the "inner heat" (Tib. GTum mo , Tummo ), which increases the body heat of the meditator. Tummo is said to have protected hermits like Milarepa in the mountain caves of the Tibetan Snow Country, the mean height of which is 4,500 meters, from extreme cold.

The highly developed Indian tradition of rock architecture, which has long shaped its roots, also lived on outside of India. A focus of the development and expansion of cave temples in modern times was South Asia (excluding India) and Southeast Asia. This is proven by numerous large rock and cave temples in Sri Lanka (Degaldoruwa Vihraya, Kandy , 17th century AD and an expansion of the Dambulla cave temples in the 18th century AD to three other caves), in today's Myanmar (Po Win Daung, Tilawkaguru) and in Thailand (Khao Luang near Phetchaburi ), which only emerged or were significantly expanded in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Rediscovery and conversion

In modern times, some of the most important cave sanctuaries, the existence of which had been forgotten, have been rediscovered. Hidden wall paintings, stone reliefs, stupas, statues and sometimes valuable text documents moved through the spectacular discovery of individual sites such as Ajanta in Maharashtra by a British officer in 1819 and the Mogao grottoes near Dun Huang in China by a Daoist monk in 1900 and again the British archaeologist Aurel Stein in 1907. Goa Gajah in Bali was rediscovered in 1923 by a Dutch official and Binglingsi in the Chinese province of Gansu in 1953. Art theft and looting by foreign expeditions were often the immediate result.

In changing forms, cave temples are also part of the Buddhist and Hindu tradition in modern times. In the Aluvihara Temple in Sri Lanka, the Theravada tradition is commemorated annually with the Aluvihara Sangayana Perahara of the Fourth Buddhist Council, at which the Buddha's discourses were first written down on site. On the occasion of the Sixth Buddhist Council (Theravada tradition), a replica of the Sattapanni cave was built in the capital of Myanmar in the middle of the 20th century, where the First Council took place immediately after the Buddha's death. The monumental Maha Pasana Guha offered a total of 2,500 Buddhist monks and 7,500 lay people during the Sixth Council in Rangoon between 1954 and 1956 .

In addition to a spiritual use, individual cave temples were used for political or military purposes in times of war and crisis. In 1904, a political conference was held in the Indonesian Goa Lawah cave in defense of the advancing Dutch. The Huyen-Khong Cave in Vietnam served local fighters as a hospital and shelter during the Vietnam War , as can be seen from the numerous damage to the cave walls. According to a plaque, a Viet Cong women's unit shot down 19 American fighter planes from here.

Cave temple in an Islamic environment

In the 19th and 20th centuries, new cave temples were completed, especially in Malaysia. Mahayana Buddhists and Daoists from China who immigrated to Malaysia emerged as the initiators of such sacred buildings. The richly furnished Perak Tong Temple (1926) in the Malaysian city of Ipoh, which is predominantly inhabited by ethnic Chinese, was donated and designed by Buddhist immigrants from China, as was the Ling Xian Yan cave temple (since 1967) near Gunung Rapat near Ipoh. The construction of the Daoist Chin Swee cave temple on the Genting plateau in Malaysia was funded by a Chinese businessman between 1976 and 1993. A wave of Islamization that went through Malaysia in the 1970s did not detract from this construction activity, which was mainly carried out by wealthy immigrants.

Individual systems have been refined over decades. The first of the extensive Hindu Batu Caves near the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur was consecrated as a temple in 1891. In 1920 an elaborate wooden staircase was added. A 42.7 meter high statue of the Hindu god Murugan was completed in 2006 after three years of construction and since then has been the center of the Tamil Thaipusam festival every year in February . This "most ecstatic festival of penance and thanksgiving" by the Hindus commemorates the mythical victory of Murugan, the son of the Hindu deities Shiva and Parvati , over three demons.

While the Asian cave temples in their Indian beginnings were mostly lonely retreats for secular ascetics and Buddhist mendicants, in Malaysia several millennia later during Thaipusam they are the focus of one of the most dazzling spiritual events of modern times. The secluded and contemplative life of the monks and nuns in impassable areas has given way to a popular, ecstatic mass procession and their trance-like flagellation rites.

literature

Outside Asia

- Johannes Dümichen : The Egyptian rock temple of Abu Simbal . Hempel, Berlin 1869.

- Rosemarie Klemm : From quarry to temple: observations on the building structure of some rock temples of the 18th and 19th dynasties in motherland Egypt . In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde , Vol. 115 (1988), pp. 41–51.

- Heinrich and Ingrid Kusch: Cult caves in Europe: gods, spirits and demons . vgs, Cologne 2001.

- Hans J. Martini: Geological problems in saving the rock temples of Abu Simbel . Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970.

South asia

- KV Soundara Rajan: Cave Temples of the Deccan. Archaeological Survey of India , Delhi 1981.

- KV Soundara Rajan: Rock-Cut Temple Styles . Somaiya, Mumbai 1998.

- Carmel Berkson: The Caves at Aurangabad. Early Buddhist Tantric Art in India . Mapin Int., New York 1986.

- Herbert Plaeschke and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries . Köhler & Amelang, Leipzig 1982. [on Ajanta and Ellora]

- Bernd Rosenheim : The world of the Buddha. Early Buddhist Art Sites in India . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006.

- Dietrich Seckel : Art of Buddhism. Becoming, wandering and changing. Holle, Baden-Baden 1962.

Central, East and Southeast Asia

- Dunhuang Institute of Cultural Relics (Ed.): The Dunhuang Cave Temples . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1982.

- Reza: The hidden Buddha . Knesebeck 2003. [on Xinjiang]

- William Simpson: The Buddhist Caves of Afghanistan . JRAS, NS 14, pp. 319-331.

- Pindar Sidisunthorn, Simon Gardner, Dean Smart: Caves of Northern Thailand . River, Bangkok 2007.

- Michael Sullivan: The Cave Temples of Maichishan . University of California Press, Berkeley 1969.

Web links

- Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road . Edited by Neville Agnew. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Trust 1997. General map of the cave temples along the Silk Road and beyond on pp. XIV and XV. (PDF; 1.79 MB)

- Murals of the Buddhist cave monasteries in Ajanta (website)

- Hindu cave temples in Ellora (website)

- The International Dunhuang Project (website)

- Mark Aldenderfer: Caves as sacred places on the Tibetan plateau (PDF; 597 kB)

- Cave churches in Cappadocia by Olaf Gerhard & Bernd Junghans (website)

Individual evidence

- ^ Owen C. Kail: Buddhist Cave Temples of India . Bombay: Taraporevala 1975. p. 3.

- ↑ Dorothea Baudy: Art. “Holy Places. I. Religious Studies ”. In: Religion Past and Present (RGG4). Vol. 3, FH. Edited by HD Betz, Don S. Browning, B. Janowski, E. Jüngel. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2003. Sp. 1551f.

- ↑ Emmanuel Anati: Art. "Prehistoric Art". In: Religion Past and Present (RGG4). Vol. 6, NQ. Edited by HD Betz, Don S. Browning, B. Janowski, E. Jüngel. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2003. Sp. 1555–1558, here: Sp. 1556.

- ↑ Other rock temples in Egypt are usually designed as mixed forms, in which part of the temple is carved into the rock and the vestibules, façades and sculptures in front of the temple are peeled out of the natural stone or added as built architecture, including beeches -Wali near Kalabsha , Beni Hasan and Deir el-Bahari .

- ↑ Uwe Bräutigam, Gunnar Walther: Buddha encounter. A trip to the holy places in Nepal and India . Krefeld: Yarlung 2005 (DVD, 11th-15th min.)

- ^ Tarthang Tulku: Holy Places of the Buddha . Berkeley: Dharma 1994. p. 111.

- ↑ Hans Wolfgang Schumann: Buddhism. Donors, schools and systems . 4th edition. Munich: Diederichs 1997. pp. 55f., 130.

- ^ Mario Bussagli: India, Indonesia, China . Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1985. p. 85.

- ^ AL Basham: History of Doctrines of the Ajivikas. London: Lucac 1951 (Reprint: Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass 1981).

- ↑ Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1987. S. 153.

- ↑ Klaus Fischer , Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1987. S. 94.

- ↑ Richard Gombrich: Buddhism in ancient and medieval India. In: Heinz Bechert, Richard Gombrich (ed.): The Buddhism. Past and present . Munich: CH Beck ³2008. Pp. 71–93, here p. 84.

- ↑ Gabriele Seitz: The visual language of Buddhism. Düsseldorf: Patmos 2006. p. 88.

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. p. 13.

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. pp. 43f.

- ↑ Bernhard Maier : “Temple. I. Religious Studies ”. In: Religion Past and Present (RGG4). Vol. 8, TZ. Edited by HD Betz, Don S. Browning, B. Janowski, E. Jüngel. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2005. Sp. 131f.

- ↑ Alexander B. Griswold: "Burma". In: Alexander B. Griswold, Chewon Kim, Pieter H. Pott: Burma, Korea, Tibet . Baden-Baden: Holle 1963 (Art of the World). Pp. 7–58, here: p. 22.

- ↑ Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1987. P. 91.

- ↑ Klaus-Josef Notz (Ed.): The Lexicon of Buddhism. Basic concepts, traditions, practice . Vol. 1: AM. Freiburg 1998. p. 35.

- ^ Mario Bussagli: India, Indonesia, China . Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1985. p. 75.

- ↑ Klaus-Josef Notz (Ed.): The Lexicon of Buddhism. Basic concepts, traditions, practice . Vol. 2: NZ. Freiburg 1998. pp. 504f.

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. p. 42.

- ^ Owen C. Kail: Buddhist Cave Temples of India . Bombay: Taraporevala 1975. pp. 17-27.

- ↑ Cf. Bernd Rosenheim: Die Welt des Buddha. Early Buddhist Art Sites in India . Mainz: Philipp von Zabern 2006. p. 75.

- ↑ Bernd Rosenheim: The world of the Buddha. Early Buddhist Art Sites in India . Mainz 2006. pp. 183-185.

- ↑ See the overview of cave temples and other Indian monuments of the state monument protection authority Archaeological Survey of India Archived copy ( Memento of the original from June 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Owen C. Kail: Buddhist Cave Temples of India . Bombay: Taraporevala 1975. pp. 7-10.

- ^ Tarthang Tulku: Holy Places of the Buddha . Berkeley: Dharma 1994. p. 288.

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. p. 16.

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. pp. 78–120, here: p. 78.

- ^ Tarthang Tulku: Holy Places of the Buddha . Berkeley: Dharma 1994. pp. 331-352. In contrast to India and Afghanistan, cave temples in the area of today's Pakistan and in the Himalayan region (for example Luri Gompa in today's Nepal ) were only created in smaller numbers.

- ^ Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road . Edited by Neville Agnew. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Trust 1997, p. 4. ( PDF ( Memento of June 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Classical Chinese Architecture . Edited by the Chinese Academy of Architecture. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft 1990. p. 11.

- ↑ See: Dietrich Seckel: Art of Buddhism. Becoming, wandering and changing. Baden-Baden: Holle 1962. pp. 136f.

- ↑ See the overview maps of cave temples along the Silk Road and in other regions in: Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road . Edited by Neville Agnew. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Trust 1997. pp. XIV and XV. ( PDF ( Memento of June 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Chewon Kim: "Korea". In: Alexander B. Griswold, Chewon Kim, Pieter H. Pott: Burma, Korea, Tibet . Baden-Baden: Holle 1963 (Art of the World). Pp. 59–149, here: pp. 94f.

- ↑ " sekibutsu 石 仏 " in the Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System .

- ↑ Manfred Auer: From Bangkok to Bali. Thailand - Malaysia - Singapore - Indonesia. Travel manual. Cologne: DuMont 1987. p. 266.

- ↑ Manfred Domroes: "Conceptualizing Sri Lanka's Geodiversity for Tourism Exemplified by a Round Tour". In: Manfred Domroes, Helmut Roth (edd.). Sri Lanka. Past and Present. Archeology, Geography, Economics. Selected papers on German research. Weikersheim: Margraf 1998. P. 168-197, p. 183-184.

- ↑ In neighboring Cambodia , cave temples are not very common. An exception is Phnom Chhnork near Kampot (7th century AD).

- ↑ Herbert and Ingeborg Plaeschke: Indian rock temples and cave monasteries. Ajanta and Ellura. Vienna, Cologne, Graz: Böhlau 1983. p. 37.

- ↑ Gabriele Seitz: The visual language of Buddhism. Düsseldorf: Patmos 2006. pp. 192f., 196.

- ↑ Manfred Auer: From Bangkok to Bali. Thailand - Malaysia - Singapore - Indonesia. Travel manual. Cologne: DuMont 1987. p. 105.

- ↑ Manfred Auer: From Bangkok to Bali. Thailand - Malaysia - Singapore - Indonesia. Travel manual. Cologne: DuMont 1987. p. 137.