Heinrich Zille

Heinrich Rudolf Zille (born January 10, 1858 in Radeburg near Dresden , † August 9, 1929 in Berlin ) was a German graphic artist , painter and photographer . In his art, the Zille, known as Brush Heinrich , preferred themes from Berlin folk life, which he portrayed both locally patriotic and socially critical.

Live and act

Childhood and youth

Heinrich Zille was the son of the watchmaker Johann Traugott Zille and his wife Ernestine Louise, b. Heinitz, a miner's daughter from the Ore Mountains . It was first claimed 15 years after his death that the father had previously worked as a blacksmith. The reason can be that Heinrich Zille should be established as a draftsman from among the people, for which, however, neither his own profession, lithographer nor that of his father, both of which are more associated with the petty bourgeoisie. Certificates prove that the claim is false. The South African politician Helen Zille claims to be related to Heinrich Zille's paternal family. Heinrich Zille was born in the small Saxon town of Radeburg (near Dresden ) in a back building of what is now Markt 11, on which a plaque commemorates him. After his birth the northern side of the market burned down in the same year, and the Zilles moved to what was then the “Stadt Leipzig” inn, now Heinrich-Zille-Straße 1. Heinrich Zille lived there until he was three years old.

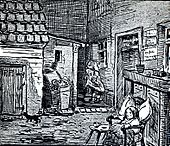

In September 1861, his father bought a plot of land in Dresden for 5000 Taler and moved there with his family. A year and a half later, the property was sold on for a profit of 600 thalers. For the time after that, the family can be identified at four addresses in the Saxon state capital. When in the summer of 1868 the twice-yearly citizen taxes did not materialize, the authorities became aware of the family's departure. In the meantime, she lived in Berlin until Heinrich was 14 years old under poor conditions in a basement apartment at 17 Kleine Andreasstrasse, near the Schlesisches Bahnhof . Heinrich Zille earned additional money by delivering milk, rolls and newspapers and other porter and messenger services.

Zille was impressed by William Hogarth's engravings , which he had discovered in penny magazines . At school he began to take drawing lessons; he had to pay the costs himself. His private drawing teacher, Anton Spanner, encouraged him in a conversation about his career aspirations to become a lithographer: "When you become a lithographer, you sit well dressed with a collar and tie in the room. You don't sweat and don't get dirty hands. What do you want even more?" According to his father's wishes, Zille was originally supposed to be a butcher , but he couldn't see any blood, so he apprenticed to the stone draftsman Fritz Hecht on Alte Jakobstrasse .

Apprenticeship and professional years

At the same time Heinrich Zille took up studies with the painter, illustrator and caricaturist Professor Theodor Hosemann at the Royal Art School . Hosemann was a humorous and precise artistic observer of the old Berlin petty bourgeois and philistine. Hosemann gave the student Zille the advice on the way: “You'd better go out into the street, outside, observe yourself, that's better than copying me. Without wanting to become an artist, you can always use drawing in life; without being able to draw, no thinking person should be. "

After completing his studies, Zille first worked in various companies from 1875: he drew women's fashions, patterns for lighting fixtures, kitsch and advertising motifs, and portrayed work colleagues for his pleasure or for a fee. Another professional armor was Zille in lithography institution "Winckelmann & Sons", where he met as a journeyman various graphic techniques: color print , zincography , producing clichés , retouching , Ätzradierung and finally light pressure and photogravure . At Winckelmann, Zille worked with the later animal painters Oskar Frenzel and Richard Friese . On October 1, 1877, he got a job as a journeyman with the “ Photographische Gesellschaft Berlin ” on Dönhoffplatz , where he was to remain employed for thirty years, with interruptions due to military service. Since the printing technology was still in its infancy around the turn of the century and there was still no perfect picture printing on the letterpress press - the autotype had just been developed in 1880 - the retouchers made photographic recordings of the originals, which were corrected in detail with the retouching tools.

military service

From 1880 to 1882, Zille completed his military service as a grenadier with the Leib-Grenadier-Regiment, first Brandenburg No. 8 , in Frankfurt (Oder) and as a guard in the Sonnenburg prison (today Słońsk ). These years were an unpleasant experience for Zille, which he recorded in numerous notes and sketches during his free time. Once he noted: “We were distributed to the companies, if you came into the rooms, the bugs were already lurking. Garbage dismantled in the beds, chopped straw. Bad food. Instead, the officers polluted a cloaca of barracks yard flowers and jokes every day. […] It was part of the team training that a lieutenant's spoon was allowed to point to the picture of my loved one on the inside of the door with the sneering question: 'Your pig?' "

During the two years of service he created episodic pictures of soldiers with a predominantly humorous character, but many of these works have been lost. Zille later processed his own military experiences in his "anecdotal soldiers and war pictures", which were published during the First World War, in 1915 and 1916, as a series under the titles "Vadding in France I u. II "and" Vadding in Ost und West "appeared. The satirical, albeit predominantly patriotic, illustrated volumes were often viewed as glorifying war, and as a result, at the suggestion of his friend Otto Nagel , Zille created the more haunting anti- war images of war jam , which, however, were only published in small numbers long after the war and have since lost their relevance.

family

After being released from the military, Zille returned to the Photographic Society . Soon afterwards he got to know Hulda Frieske, daughter of a master needle maker and teacher. Both married in Fürstenwalde on December 15, 1883 , after Frieske had turned eighteen on September 22. The couple moved into a basement apartment in Boxhagen-Rummelsburg on Grenzweg (today: Fischerstraße, see → Berlin-Rummelsburg ); In 1884 the daughter Margarete was born in the apartment Lichtenberger Kietz 13. In 1886 the family had to cope with the death of a daughter who did not survive the birth, in 1888 son Hans was born in Türrschmidtstraße, where the Zilles had moved in 1887, followed by son Walter in 1891 in Mozartstraße (today: Geusenstraße). All of the Zilles' quarters were in the same eastern suburb of Berlin, in the Victoriastadt in Lichtenberg. The last stage took the family to a three-room apartment in Berlin-Charlottenburg in Sophie-Charlotten-Straße 88, 4th floor in 1892 . Heinrich Zille lived here for almost 40 years, until his death. This apartment was closer to Zille's place of work because the Photographic Society had meanwhile moved to the new Westend villa district . This time was to be one of the most creative phases in Zille's work. Even if he himself did not believe in success as an artist, he continued to devote himself to his drawings and studies in his free time. In terms of drawing style, Zille was still influenced by the journal Die Gartenlaube .

The South African politician Helen Zille is his great niece.

Zille as a photographer

Between 1882 and 1906 Heinrich Zille also turned temporarily to photography. The fact that he himself was active in photography outside of his workplace was first revealed in 1967 by Friedrich Luft's book Mein Photo-Milljöh. 100x Alt-Berlin recorded by Heinrich Zille himself claims. In Zille's apartment on Sophie-Charlotten-Str. 88 “418 glass negatives, some glass positives and over 100 photographs, of which no more negatives can be found”, were found again in a chest of drawers. The photos were known in the family and some of them had already been published. These pictures do not show the dressed up imperial side of Berlin, but the everyday life of Berliners in the backyards or at the annual markets. However, it cannot be proven whether Heinrich Zille is the author of these photographs. Doubts arise in particular from the lithographer's refusal to use technical equipment to create images. Another argument against Zilles' own photographs is that there was not a single camera in his estate. The fact is that he was employed as a lithographer at the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin for 30 years (until 1907) and worked there, among other things, in the photo laboratory. However, it is disputed whether he ever took photos. He is said to have used the studios of August Gaul and August Heer for the nudes attributed to him from 1900/03 . These recordings show what is happening in the studio, the models and artists at work. It is noteworthy that the animal sculptor August Gaul as photographer and Heinrich Zille as his developer in the photo laboratory can be proven at that time. Zille saw the camera as a “photographic notepad” for his graphic studies, for which he also used postcard motifs and press photos, among other things.

"Zille sein Milljöh"

At the turn of the 20th century, Heinrich Zille began more and more consciously to discover scenes from the proletarian lower class for himself as a subject . Zille found his "Milljöh" in the backyards of the tenements , side streets and barracks of the working-class neighborhoods . In 1907 Zille was dismissed from the Photographic Society for this reason . This hit the fifty-year-old hard: He was bitter, indignant and deeply dismayed. Friends of Zille, who were artists, especially Paul Klimsch , but also Max Liebermann , saw his dismissal calmly or optimistically, because they believed in Zille's artistic potential. It should take time for Zille to understand that he was on the threshold of a completely new phase of life: away from decades of workshop life and towards real life outside the front door. He remembered the words of his former professor: "Better go out into the street ...".

Heinrich Zille only began to work as a freelance artist after his dismissal and now found the style that was so typical for him , which, with its Berlin-based texts, short stories and bon motes , made his drawings so original. In the meantime, the “Brush Heinrich”, as he was affectionately known, was no longer a stranger to Berlin and already enjoyed a certain fame as a virtuoso portrait draftsman. With their mocking social criticism of the Wilhelmine era, Zille's work did not always meet with approval. Tragedy and abyss were hidden behind his sometimes bitterly angry drawings: "If I want, I can spit blood in the snow ...", a consumptive girl boasts of other children. An officer angrily commented on an exhibition with the classic sentence: "The guy takes away the joy of life!"

The Secession and success as an artist

At the turn of the century Heinrich Zille was able to exhibit his first drawings and publish them in magazines such as Simplicissimus , Jugend - Münchener Illustrierte Wochenschrift für Kunst & Leben and Die Lustigen Blätter . Soon one became aware of “the newcomer” in the Berlin artist circles. The art critic Hans Rosenhagen valued Zille as “a new phenomenon, which attracts attention with a series of realistic and humorous colored drawings 'from dark Berlin' and a highly drastic 'spring miracle'.” During this time he was a friend of his sculptor August Kraus Model for the bust of the knight Wedigo von Plotho, which was unveiled as part of a monument on Siegesallee in 1900.

In 1903 Zille was accepted into the newly founded Berlin Secession , an artist group that had split off from the academic art business that had dominated the academic art world at the instigation of Max Liebermann , Walter Leistikow and Franz Skarbina . Heinrich Zille was also an early member of the German Association of Artists , which was also founded that year ; his membership can be found for the first time in the membership directory of the third annual exhibition of the DKB in 1906 in the Grand Ducal Museum in Weimar . Zille became a protégé and a good friend of Liebermann. In the same year Zille began to work on the Munich satirical magazine " Simplicissimus " published by Th. Th. Heine and Albert Langen . He got to know the Norwegian draftsman Olaf Gulbransson . This was followed by Jugend (1905) and finally the Lustige Blätter , published by Dr. Eysler & Co. Berlin published the first popular milieu drawings of Zille's Kinder der Straße and Berliner Rangen (both 1908) as part of the Künstlerhefte series , which initiated Zille's high-circulation publications. With the portfolios Mother Earth (1905) and Twelve Artists' Prints (1909) with heliogravures of hand drawings and etchings, Zille finally achieved national fame as one of the best German draftsmen. In 1914 he brought out his second illustrated book "Mein Milljöh". The public success as a freelance artist came at just the right time for Zille in view of his dismissal from the Photographic Society . Gallery owners tried to find the "professor with nickel glasses", and occasionally Zille also sold works to private collectors and created murals for various localities and beer cellars. Despite all the respectable successes, the Berlin National Gallery did not acquire a large number of drawings from him until 1921.

In 1910, Zille and Fritz Koch-Gotha were awarded the Menzel Prize of the Berliner Illustrirten Zeitung for their artistic achievements. In 1913 around 40 artists, including Zille, left the Berlin Secession and founded the Free Secession . Zille became a board member; Honorary President was Max Liebermann. At Liebermann's suggestion, Zille finally became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1924 when he was appointed professor . Despite all his fame, Zille always remained relatively indifferent to the numerous honors that were offered to him. This did not change when his first picture books were successfully published in the midst of the privations of World War I , and the artist remained humble in later years.

Zum Nussbaum (postcard from 1923)

Later years and death

After the war, Zille increasingly suffered from gout and diabetes . On June 9, 1919, Zille's wife Hulda died at the age of 54. His son Hans and his beloved daughter-in-law Anna also died early. Anna, wife of Zille's son Walter, died of a pulmonary embolism just a few months after Heinrich Zille in December 1929 , the son Hans died in 1934.

When his wife died, Heinrich Zille decided to keep the apartment at Sophie-Charlotten-Straße 88 until his death: “My walls should be my home until I die.” The house was later listed as a historical monument. Of the three children Grete, Hans and Walter, Zille had only one granddaughter, Anneliese Preetz-Zille, the daughter of his son Hans.

The son Walter kept the apartment on Sophie-Charlotten-Straße for a while in the spirit of his father, but liquidated it in the post-war years for financial reasons.

In the last years of his life, Heinrich Zille published drawings in the Berlin satirical magazine Ulk . He reached the height of his popularity a year before his death with the celebrations for his 70th birthday. In Märkisches Museum one was retrospective of his works under the title "Zille career" issued.

Zille suffered a first stroke in February 1929 and a second in May . In the period that followed, the artist increasingly withdrew and had a postcard drawn in shaky handwriting on his apartment door: “I'm sick. Please no visit. "

Heinrich Zille died on the morning of August 9, 1929. He was given a grave of honor by the city of Berlin in the south-west cemetery in Stahnsdorf. Epiphany burial block (field 14, garden point 34/35). Around 2000 mourners followed the coffin. A sign and a stone point the way "to Zille".

reception

Zille is one of the most famous Berliners of the first half of the 20th century and, along with Claire Waldoff , with whom he was friends, is one of the Berlin originals . He has been immortalized in numerous honors in the German capital. With his drawings he reached both the upper educated bourgeoisie and the "normal people", who served him as a grateful subject.

Reflections on the person

“ ... there is a third barge, and this one is my favorite. He's neither a humorist for joke papers nor a satirist. He is completely an artist. A few lines, a few strokes, a little color here and there - and they're masterpieces. "

Heinrich Zille undoubtedly became popular and popular thanks to the joke and satirical papers: soon everyone knew his humorous, sometimes sarcastic, but always unmistakably black captions by heart. But there was another introverted Zille hiding behind the “Brush Heinrich”, whom only his most intimate friends knew and appreciated. Beyond all comedy and laughter, he shielded this privacy from prying eyes. It was in this private world that the unknown drawings and etchings were created , which never found their way into Zille volumes: pairs of peddlers waiting motionlessly, hoping for crumbs, on whose shoulders the whole injustice of society seems to weigh; old brushwood collectors who, stooped and bent in grief, carry with them a load other than that of their boxes ; Then there are numerous nude studies of women workers from the time after the turn of the century, in which there is nothing of tenderness to be found, but robust corporeality; numerous sketched infants and toddlers whose faces seem ancient to the viewer; In addition, early landscape studies and portraits were found in Zille's secret archive. The numerous sensitive “private portraits” of his friends, including Ernst Barlach , August Gaul , Lyonel Feininger , Käthe Kollwitz, Max Liebermann, Otto Nagel and August Kraus , have Zille's tendency towards quick caricatures, but they also reflect the typical, the character of the face contrary.

Käthe Kollwitz and Heinrich Zille had a long friendship. Both lived and worked in Berlin, often met at the academy and had artistic similarities; they devoted themselves, albeit in different ways, to similar topics and subjects.

It was not until 2014 that it became publicly known that the influential publicist Erich Knauf wrote a manuscript for a Zille biography in the early 1930s, which the author was no longer able to publish himself. Under the title “The Unknown Zille” he devoted himself to the life and work of the artist in a critical and holistic way; In particular, he condemned Heinrich Zille's self-marketing in the last years of his life, as well as the use of color and composition in overly narrative works. For example, Knauf wrote:

“The people love kitsch, they are brought up to do it. 'Father Zille' - that is kitsch in larger than life size. This gave the whole Zill topic a twist, which turned this draftsman's way of life and his Milljöh into a sentimental hit. Even where, as in the Zille films, one assumed more honest motives, it became a distorted image. Zille gave his blessing on everything. It brought him money and honor. "

Mother joke and dialect: The Berlinish

The variety of Zille's descriptions of the milieu, humor and anecdotes are a unity of image and mostly handwritten subtitles that are not tied to a specific location. They are apparently easily thrown away milieu studies, paired with crude dialogues in the flippant Berlin dialect without grammatical accuracy. The captions are to be understood more as comments that accompany Zille's view of the backyards and Wilhelmine offices of the turn of the century in an ironic, sometimes sarcastic-macabre way. Many Zille bonmots intensify the caricature's gallows humor, while other quotes try to soften the hopeless dreariness with fatalistic joke almost mercifully: "Don't get drunk and bring the coffin back, the millers need their furniture too."

Even during his lifetime, Zille had his nicknames among Berliners who were keen on formulating: from "Father Zille", the "Brush Heinrich", to " Daumier von der Panke " or " Raffael der Hinterhöfe" to "Herr Professor mit der Nickelbrille". In addition to Zille's professorship, the weekly Fridericus published by Friedrich Carl Holtz added another completely disparaging critique to “Zille seine names”: “The Berlin abortionist Heinrich Zille is elected a member of the Academy of Arts and as such by the Minister of Education, Otto Boelitz [German People's Party. D. Author] has been confirmed. Cover your head, o muse. "

Zille and children

“Father Zille” showed his full participation in the Berlin ranks: he was the godfather of countless Berlin children. Zille's children's drawings have an unadorned liveliness; they are authentic. Zille drew “his children” without any fuss: unwashed, lumpy and filthy with running or bloody noses, which they longingly press flat against the filled shop windows of the affluent society, only to be scared away immediately. “For Zillen know you are dirty,” claimed a Berlin mother. Zille's children quarrel and scramble, rubbing the adults' mouths with cheeky Berlin dialect. Often there are philosophical considerations from a child's point of view, for example in a drawing from the Berlin Christmas market: “Only two jumping jacks are sold today. Mankind no longer has any sense for the harmless! ”.

Zille was often certified that his children's drawings were "far from any misery romance". Zille knew exactly what awaited “his Kleenen” when they grew up: “Twenty-three Fennje got a homeworker, and the children went to a match factory and had no more fingernails from the phosphorus and sulfur jar. And you shouldn't even get in between when you have seen how the misery feeds on from generation to generation - where the child is already born as a slave ?! "

Pornography theme

A year before the outbreak of war, Zille's illustrated book Mein Milljöh and the Berliner Luft cycle had already been published. In 1921, the whore conversations followed under the pseudonym W. Pfeifer and with the wrong year 1913. Zille's unvarnished depiction of prostitutes and pornography aroused the displeasure of moral guards and moral apostles in many places. The Casual Stories and Pictures , which were published by Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin in 1919 in a small, numbered edition, were temporarily confiscated. In 1925 Zille was sued in Stuttgart for the publication of his lithograph Modellpause im Simplicissimus , which shows eight undressed girls. Despite the reputation certificates of his artist friends, he was sentenced to pay 150 Reichsmarks and destroy all printing plates. In a monograph on Zille, the author Lothar Fischer said that the subject of pornography was a personal concern of his, and that the whore conversations were “not a by-product of Zille, for example a result of financial hardship, but the topic was a real concern for him. "

The apolitical-political tariff

Zille's life and work justify calling him a socially critical person. At first glance, his drawings appeared to be mere anecdotes and humores, but on closer inspection it becomes clear that he was holding up a socially critical mirror to both Wilhelminism and the subsequent Weimar Republic . Zille, who himself came from a poor working class family and suffered from hunger and hardship as a child, remained down-to-earth as a successful and financially secure artist, always focusing on the worries and sensitivities of the lower class . Zille was socially committed all his life and stood up for the rights of the common people. He observed the influx of the National Socialists with suspicion. To what extent Heinrich Zille can be classified as a political person remains open. He often distanced himself from party politics, for example by repeatedly declaring: “I don't want to be part of politics.” What is certain is that he had similarly thinking people gathered around him in his private circle: for example his artist friend Otto Nagel , who met at an early age Had joined the workers' movement, or Käthe Kollwitz , who was non-party all her life, but described herself as a socialist . In contrast to many of his friends, who were later ostracized as representatives of supposedly “ degenerate art ”, Zille did not live to see the beginning of the Nazi era and thus escaped reprisals such as work, exhibition and residence bans.

time of the nationalsocialism

Zille was far too popular to be branded as a “decomposer” and “enemy of the people”. After Zille's death, the writer and Zille biographer Hans Ostwald published two new Zille volumes in collaboration with Zille's son Hans: Zille's Legacy (1930) and Zille's Hausschatz (1931). He added new captions to the artist's leftover illustrations, which approximated the National Socialist ideology, but probably did not correspond to the artist's intentions. The same applies even more to the new edition of Zille's Hausschatz , edited by Ostwald in 1937 with the help of the SA Standartenführer and journalist Otto Paust , who wrote ideological novels like Volk im Feuer , which was not authorized by his descendants.

Reception after 1945

In the post-war period , the newly founded Kulturbund of what was later to become the GDR in 1945 took advantage of Zille's proximity to the workers' movement for cultural-political propaganda purposes and stylized the almost forgotten Zille and his fellow artists as artists of the people. Since 1949, a bronze plaque commemorating the artist has been attached to Zille's home in Charlottenburg's Sophie-Charlotten-Strasse and is said to date from 1931. The inscription reads: “From September 1st, 1892 until his death, the master of the drawing pencil, the portrayal of Berlin folk life Heinrich Zille, nee. 10.1.1858 Radeburg, died August 9th, 1929 Berlin - His memory - The city of Berlin - 1931. ”An additional note in the rubrum of the plaque states:“ The Zille memorial plaque was given for scrapping after 1933 - saved by workers' hands - renewed in 1949. "

Movie

The name Zille was often used for films about the “poor people of Berlin” at the turn of the century. However, only a few of these productions have anything to do with his life:

The Disreputable by Gerhard Lamprecht from 1925 was created while Zille was still alive with his approval and promoted the commercialization of his name. According to stories by Heinrich Zille, in the year of his death in 1929, Piel Jutzi's film Mother Krausens Fahrt ins Glück was made in his memory, the book being by Willy Döll and Jan Fethke . The film was shot under the protectorate of Käthe Kollwitz. Kollwitz was responsible for the authenticity of the film and created her largest poster for it.

The DEFA - Musical Zille and ick from 1983 directed by Werner W. Wall Roth is based only on the Zille milieu, but has little in common with Zille's biography.

Heinrich Zille - TV film commissioned by ZDF 1977, directed by Rainer Wolffhardt , with Martin Held as Zille, Stefan Wigger as Liebermann - describes Zille's life in selected stations. It is thanks to Martin Held's haunting game that this film allows Zille as a person in “his milieu” to become an eyepiece of the time and society in which the artist lived. Held met Zille in his childhood in Berlin.

Zille's life is portrayed in the 1979 film Brush Heinrich by Hans Knötzsch .

The documentary In Zilles Scheunenviertel Experienced (1986) accompanies a school class on the trail of Zille's milieu.

Awards and honors

Further honors in his hometown are shown under Radeburg / Personalities .

On February 4, 1970, Heinrich Zille was posthumously appointed 80th honorary citizen of Berlin as "Milljöhs' picture chronicler" by the Berlin magistrate . He is also remembered at the following places :

Museum (since 2002)

- Zille Museum, Propststraße 11 (in the Nikolaiviertel ), Berlin-Mitte

Monuments

- Köllnischer Park (at the Märkisches Museum), Berlin-Mitte

- Poststrasse (in the Nikolaiviertel), Berlin-Mitte

- Volkspark Prenzlauer Berg (part of a relief), Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg

Honor grave

- Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf (Protestant), Bahnhofstrasse, Stahnsdorf

Memorial plaques

- Propststrasse 3, Berlin-Mitte

- Zille residential building, Geusenstrasse 16, Berlin-Rummelsburg

- Zille residential building, Sophie-Charlotten-Straße 88, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf

- Memorial stone Zille parental home location, Fischerstraße 8, Berlin-Rummelsburg

- Zille birthplace, Markt 11, Radeburg

- Memorial stone, Zille-Hain, Radeburg

- Relief by Prof. August Kraus , Zille residential building, Heinrich-Zille-Strasse 1, Radeburg

- Relief at the location of the former residential building, Dresdner Str. 107, Freital

Parks

- Heinrich-Zille-Park, Berlin-Mitte

- Zille-Hain, Radeburg

Settlements and street names (selection)

- Heinrich-Zille-Siedlung, Berlin-Moabit

- Zillestrasse , in Berlin-Charlottenburg

- Zillestrasse, Frankfurt am Main

- Zillestrasse, Wolfsburg

- Zillepromenade Lichtenberg

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Ludwigsfelde

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Dresden

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Hanau

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Radeburg

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Lauchhammer

- Father-Zille-Weg, Radeberg

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse , Radebeul

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Stahnsdorf

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Wiesbaden-Schierstein

- Heinrich-Zille-Radweg, from the Elberadweg to Radeburg

- Heinrich-Zille-Winkel, Taucha

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Hoyerswerda

- Zillehof, Vienna - Hietzing

- Heinrich-Zille-Platz; Monheim am Rhein

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Halle (Saale)

- Heinrich-Zille-Weg, Medingen (Ottendorf-Okrilla)

- Heinrich-Zille-Weg, Riesa

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Cologne-Esch

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Frankfurt (Oder)

- Heinrich-Zille-Straße Kassel / Niederzwehren

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Bremervörde

- Heinrich-Zille-Strasse, Chemnitz

Schools (selection)

- Zille Elementary School Berlin-Friedrichshain

- Heinrich-Zille-Schule Radeburg , (middle school)

- Heinrich-Zille-Schule Berlin / Kreuzberg (primary school)

- Elementary school Heinrich Zille / Stahnsdorf

Pharmacies

- Heinrich-Zille Pharmacy Berlin-Wedding

Zille on postage stamps and coins

- To mark Zille's 100th birthday, the GDR Post issued two special stamps on March 20, 1958 (Michel no. 624 and 625).

- The Deutsche Bundespost Berlin published two Zille stamps: in 1957 an 8 pfennig stamp in the series “Men from the history of Berlin” with a portrait of Zille (Michel no. 164), in 1969 a 5 pfennig stamp in the sentence “ Berliner des 19. Jahrhundert ”with a pen drawing by Zille from 1905 showing a cab carriage (Michel no. 330).

- On January 2, 2008, on Zille's 150th birthday, Germany issued a 55-cent special postage stamp.

- Sparkasse Meißen had a commemorative medal minted in gold and silver for Zille's 150th birthday .

astronomy

- In 2000 an asteroid was named after Heinrich Zille: (15724) Zille .

Erich Büttner : Heinrich Zille (1923)

Zille Collection

The art museum of the city of Mülheim an der Ruhr has the largest Zille collection outside of Berlin. The "Themel Collection" with over 300 exhibits was created by Dr. Karl G. Themel, who, as the former attending physician of Zille's son Walter, later worked for many years as chief physician and radiologist at the evangelical hospital in Mülheim an der Ruhr. In 1979 Themel founded the art museum's support group and transferred his collection to the art museum.

Literature (selection)

From Heinrich Zille

- Heinrich Zille - father of the street. An anniversary band. Selected and edited by Gerhard Flügge . The New Berlin, Berlin 1958.

- Whore talks . 7th edition. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-88814-081-5 . (Illustrations and texts from 1921, published under the pseudonym W. Pfeifer, revised new edition from 1981, with a foreword by Winfried Ranke, limited facsimile edition 1979: ISBN 3-88814-045-5 ).

- Children of the street. 100 Berlin pictures. New edition (license from Fackelträger-Verlag, Cologne) Komet, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89836-477-1 .

- My Milljöh. New pictures from Berlin life. New edition (license from Fackelträger-Verlag, Cologne) Komet, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89836-478-X .

- All about the outdoor pool. New edition (license from Fackelträger-Verlag, Cologne) Komet, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89836-476-3 .

- Brush Heinrich paints you. Pictures from Berlin. Selection and text Matthias Flügge. 2nd Edition. Eulenspiegel-Verlag, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-359-00123-0 (first edition 1987).

Digital edition of his works

- Heinrich Zille: Works and writings - All caricature editions - The entire literary work - Over 1500 illustrations. Zeno.org published by Directmedia Publishing, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-89853-611-0 .

About Heinrich Zille

- Nicole Bröhan: Heinrich Zille: A biography . Jaron Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-89773-734-1 .

- Lothar Fischer : Heinrich Zille. In self-testimonials and picture documents . Rowohlt's Monographs Volume 276, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1979, ISBN 3-499-50276-3 .

- Matthias Flügge , Matthias Winzen (Ed.): Heinrich Zille and his Berlin. Types with depth. Athena, Oberhausen 2013, ISBN 978-3-89896-530-9 .

- Matthias Flügge (Ed.): The old Berlin: Photographs 1890-1910. New edition, Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8296-0138-7 .

- Pay Matthis Karstens: Forbidden and falsified. Heinrich Zille under National Socialism . Past Publishing, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86408-134-7 .

- Erich Knauf: The unknown Zille . Past Publishing, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3864081880 .

- Robert McFarland: From Zola's Milieu to Zille's Milljöh: Berlin and the Visual Practices of Naturalism . In: Excavatio , XIII, September 2000, pp. 149-166.

- Otto Nagel : Heinrich Zille - Life and Creation. Henschel, Berlin, 1968.

- Hans Ostwald: Das Zillebuch: mostly first published with 233. Images . Paul Franke, Berlin 1929. Digitized version of the University and State Library in Düsseldorf

- Hans Ostwald (ed.); Hans Zille: Zille's legacy. Paul Franke, Berlin (first edition from 1930).

- Winfried Ranke (Ed.): From Milljöh into the Milieu. Heinrich Zille's rise in Berlin society. Torch bearer, Hannover 1979, ISBN 3-7716-1406-6 .

- Werner Schumann (Ed.): Zille sein Milljöh . Torch bearer, Hanover 1987, ISBN 3-7716-1480-5 (first edition 1952).

- Walter Plathe: Have the honor ... Zille , Eulenspiegel Verlag, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-359-01176-7 .

Television documentaries and games

- This was Zille sein Milljöh (SFB 1981) from Irmgard von zur Mühlen

- Heinrich Zille . TV play with Martin Held (1977)

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich Zille in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinrich Zille in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Heinrich Zille in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Markus Rehnert, Levke Harders: Heinrich Zille. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by Heinrich Zille at Zeno.org .

- Heinrich Zille Museum in Berlin

- "Heinrich Zille: The Ephemeral Glory of the Proletariat" , FAZ , January 15, 2008, with picture gallery

- Detlef Zille: Heinrich Zille and Photography - The Doubtful Attribution of Photographs , in: Photo History 130 , 2013

- Pay M. Karstens: "... even though I wanted the house to be photographed ...". Unknown and neglected evidence of Heinrich Zille's photographic activity , in: Fotogeschichte 130 , 2013

- Corina Kolbe: Zilles Berlin. “You can kill with an apartment”. 19 photos on Spiegel Online, January 29, 2015

- List of certificates and documents relating to Heinrich Zille

- Works by Heinrich Zille in the Gutenberg-DE project

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adolf Heilborn: The draftsmen of the people, Käthe Kollwitz, Heinrich Zille, Berlin-Zehlendorf, 1924, p. 58.

- ↑ List of certificates and documents relating to Heinrich Zille

- ↑ Wolfgang Drechsler: Helen Zille: Mutter Courage , juedische-allgemeine.de, September 20, 2007, accessed on July 14, 2017

- ↑ Dresden Latest News, February 29, 2016, p. 14. Press archive

- ↑ f The Zille book by Hans Ostwald in collaboration with Heinrich Zille, Berlin 1929, p 361st

- ↑ a b c d Werner Schumann: The Great Zille Album (1957)

- ^ Heinrich Zille: Jule and her honor guard

- ^ Lothar Fischer: Heinrich Zille . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1979, pp. 32, 143, books.google

- ^ Heinrich Zille Museum: Life and Work ( Memento from October 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Source: Winfried Ranke: Heinrich Zille - Photographien Berlin 1890–1910 , Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1975, p. 43.

- ↑ Hans Ostwald: Zille's legacy, with the collaboration of his son Hans Zille , Berlin 1930, p. 277, p. 279 and p. 451. Gerhard Flügge: Mein Vater Heinrich Zille, based on memories of Margarete Köhler-Zille , Berlin 1955, p. 79 and p. 208.

- ↑ Erich Kranz: Budiken, Kneipen and Destillen, Heinrich Zille and Alt-Berlin , Hannover 1969, pp. 124–127.

- ↑ Photo history magazine: Debatte_Detlef Zille. Retrieved May 2, 2017 .

- ^ Matthias Flügge, in: Heinrich Zille, Berlin around the turn of the century, Photographien, Munich 1993, p. 15

- ↑ Winfried Ranke: Heinrich Zille, from Milljöh ins Milieu , Hannover 1979, p. 233.

- ↑ Rolf Kremming: Heinrich Zille: That was his milieu, pp 11-12

- ↑ Heinrich Zille. The Ephemeral Glory of the Proletariat , faz.net, accessed July 19, 2017

- ^ Hans Rosenhagen: The art . 1902

- ↑ s. Zille, Heinrich in the directory of members of the DKB exhibition catalog 1906 (accessed on May 7, 2018)

- ↑ Zille's house on Sophie-Charlottenstrasse in the Berlin monument database

- ^ The grave of Heinrich Zille knerger.de

- ↑ Erich Knauf: The unknown Zille. Past Publishing, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3864081880 , p. 131

- ^ Heinrich Zille: Children of the street , anthology 1908

- ↑ autograph. To H. Frey 1921 , kettererkunst.de, accessed on January 27, 2014

- ^ Lothar Fischer: artist monograph on Zille. Reinbek 1979

- ↑ The dream of Helen Zille . In: Berliner Zeitung , July 22, 2006; Conversation with Heinrich Zille's great niece Helen Zille

- ↑ Ralf Thies: Ethnographer of the dark Berlin: Hans Ostwald and the big city documents . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2006, p. 278, books.google.de

- ↑ Heinrich Zille memorial plaque berlin.de

- ↑ Heinrich Zille, 1965 ( memento from July 19, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), bildhauerei-in-berlin.de (monument to Heinrich Drake )

- ^ New Zille Memorial in the Nikolaiviertel , Neues Deutschland, January 11, 2008 ( online version )

- ^ Art Museum Mülheim an der Ruhr - Themel Collection ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), museum database kunst-und-kultur.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zille, Heinrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zille, Heinrich Rudolf (full name); Brush Heinrich (nickname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter and draftsman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 10, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Radeburg near Dresden |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 9, 1929 |

| Place of death | Berlin |