Lauriacum

| Legion camp Lauriacum | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Lauriacum b) Lauriaco c) Lauriaci |

| limes | Limes Noricus |

| section | Route 1 |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Severan , 205 to 5th century |

| Type |

a) Legion camp b) Fleet fort |

| unit |

a) Legio II Italica , b) Classis Lauriacenses , c) Auxiliares Lauriacenses ? d) Lanciari Lauriacenses , e) Vigiles et exploratores |

| size | 539 × 398 m (2.1 ha) |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Square system with truncated corners and internally attached towers, the rest of the trench of the NE corner (western railway route) and foundation walls of a residential building near the St. Laurenz basilica visible above ground |

| place | Enns |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 13 ′ 0 ″ N , 14 ° 28 ′ 30 ″ E |

| height | 281 m above sea level A. |

| Previous | Lentia Fort (west) |

| Subsequently | Legion camp Albing (east) |

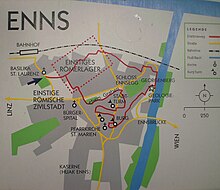

Lauriacum was a legion base and an important Roman city on the Danube Limes in Austria . It is located in the area of today's Enns district of Lorch in Upper Austria , Linz-Land district .

From a road station at a crossroads of important trade routes, Lauriacum developed into the largest and most important military base in the province of Noricum through the stationing of a legion at the transition from the 2nd to the 3rd century AD. Where there was initially only a small Roman settlement at a ford across the Enns , the Legio II Italica built a legion camp after the abandonment of an older facility in Albing around 200 AD , which was used as headquarters and next to Virunum for the following 400 years (in the area of today's Zollfeld near Maria Saal ) and Ovilava ( Wels ) served as the administrative seat for the Roman province of Noricum . The legionary camp was subsequently also part of the Limes security system and was probably continuously occupied by Roman troops from the 3rd to the 5th century. An extensive civilian settlement formed around the camp in the north and south-west, which was presumably elevated to a municipality in the early 3rd century and in the 5th century became the bishop's seat of northern Noricum - the only historically verifiable one to date. Grave fields have also been identified in numerous places inside and outside the settlement areas.

In late antiquity it became the base of a patrol boat flotilla and the production site of a state shield factory . Even after the border in Noricum and Raetia was abandoned as a result of the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire , Lauriacum once again played a historically significant role in the evacuation of the Roman population by Severin von Norikum as a refuge and assembly point. Most of the ancient building fabric fell victim to the extraction of stone material in the Middle Ages and modern times, various building activities, agricultural use and soil erosion. The best preserved ancient and early medieval evidence are the remains of their predecessor buildings in the lower church of today's St. Laurenz Basilica in Lorch. The majority of the excavation finds are presented in the Lauriacum Museum .

Surname

The name Lauriacum originally comes from the Celtic and was derived from the personal name Laurios (suffix -acus or -acum ) and translated roughly means 'among the people or clan of Laurios' (* Lauriakon) . In the course of time it changed over the medieval forms of the name Loriaca / Loraha - Lorich to today's Lorch. The river names Anisus (Aist) and Lauriacum, which are documented in ancient written sources, have been preserved to this day in a blurred form as "Enns" and "Lorch".

Lauriacum is also mentioned in many ancient sources, such as B. in

- Itinerarium Antonini (6 ×), dem

- Codex Theodosianus , dem

- Codex Justinianus , the

- Passio beatissimi Floriani martyris (9th century), dem

- Martyrologium Hieronymianum , the

- Tabula Peutingeriana , where Lauriacum is referred to as Blaboriciaco (or Laoriaco ), it is probably a copyist error of the medieval copyist in which

-

Notitia Dignitatum a military, a naval base and a shield factory are listed, the

last time Lauriacum is in the - Vita Severini by Eugippius, in this biography of the saint recorded in 511, the oppidum , or the civitas or urbs Lauriacum is also mentioned several times (Lauriacum, Lauriaci, Lauriaco) .

Roman emperors stayed in the camp for late antiquity at:

- Ammianus Marcellinus and im

- Codex Theodosianus mentioned.

Location and strategic importance

Due to the topographical conditions and its location on two important roads, the location was ideally suited for the construction of a military base. In Roman times the river branched into several arms here, as the alluvial debris of the Bleicherbach (Stallbach) had raised larger gravel islands and terraces that sloped north to the Danube. The legionary fortress and civil town stood protected from flooding on one of these terraces west of the banks of the Enns in a plain near the Danube, which here forms the northern zone of the Traun-Enns-Platte to the Linzer Feld and slopes in the northwest towards the Bleicherbach valley. The watercourses of the Enns ( Anisus or Anisa ) and Bleicherbach had also raised two mudslides, on which an auxiliary fort is said to have stood before the legionary camp was established (see below). A little further to the east is the spur of the Georgenberg , which drops steeply towards the banks of the Enns and could be used by the Romans as a quarry, as well as the Tabor northeast of Enghagen , a granite ridge that was also used for stone extraction. In addition, due to its fertile loess soils, the location could easily be supplied with food from the surrounding area.

Lauriacum was also located at the crossroads of the most important traffic routes in the province of Noricum, a central junction whose military, political and, above all, economic importance can be described as equally important. An essential prerequisite for an administrative center was always good transport links to the other civitas in the province. The Limesstrasse and the Danube waterway ( Danuvius ) led directly past Lauriacum . The mouth of the Aist ( Agista ) was exactly opposite the legionary camp on the north bank of the Danube. Since prehistoric times, a trade route has led from here to the Moldau and from there to free Germania. Lauriacum was the bridgehead of this trade route on the right of the Danube, the so-called "Freistädter Steg". The Noric iron and salt from the Alpine regions were transported to the Danube and traded on the rivers Enns and Traun .

Securing these connections to the hinterland was essential given the troubled barbarian tribes in the north. From here, the crew had a good view of the Danube between the mouths of the Traun and Enns and their opposite bank. As in the Albing camp, the main task of the crew here was to keep under control the Aist valley, which was used by the enemy in the Marcomann War. In addition, there was the guarding of the Enns bridge and the control of the Limes road.

Roads and long-distance connections

Several important waterways and traffic routes led directly past Lauriacum :

- the Danube,

- the Enns,

- the Limesstrasse,

- the "Norische Reichsstraße" and

- a road to Steyr.

Several findings show a dense Roman road network around Lauriacum , here in particular the Limes road leading from west to east, the via iuxta Danuvium , which ran past the legionary camp to the south and was the most frequented Roman road in the Danube valley. It was the east-west connection between Pannonia, Noricum, Raetien and ran parallel to the Danube. It is still followed today by the Alte Landstraße, which came from Kristein, the Stadlgasse and the Mauthausener Straße. To the east of the legionary camp there was probably also a bridge over the Enns, as ancient graves were found in Ennsdorf, which suggest a continuation of the ancient road on the eastern bank of the Enns. Another ancient road branched off at the southwest gate, which is now covered by the Mitterweg.

Another long-distance connection led between Stadtberg and Eichberg further into the Ennstal. Two north-south connections were found in the north, one of which apparently led directly to the banks of the Danube. Excavations north of the legionary camp between 2005 and 2007 uncovered another stretch of ancient road that ran parallel to the north side of the camp.

In the Antonine Itinerary is Lauriacum as the end point of the road to Aquileia indicated that met here at the Limes road. This road, the Via Julia Augusta , led from Aquileia, through the Canal Valley over the Plöckenpass into the Drautal, where at St. Peter im Holz ( Teurnia ) or Seeboden a branch branched off to Salzburg ( Iuvavum ) and so the Eastern Alps on the shortest route crossed. From the old provincial capital Virunum the road ran through the Görtschitztal, Neumarkter Sattel, Rottenmanner Tauern (1700 m) with a stopover in Wieting (Carinthia) (Candalicas) over the Pyhrnpass ( Windischgarsten / Gabromagus ) to Wels / Ovilava from where you follow the Limesstraße Took Lauriacum . In the Tabula Peutingeriana, much more recent routes are given, it shows a significantly shorter road through the Canal Valley and the course from Virunum northwards via Friesach through a gorge , with the road station Noreia .

The high alpine location of the Tauern crossing made it likely that a detour via the Amber Road ( Aquileia-Carnuntum ) had to be made in the winter months , so that Lauriacum was only reached two weeks later. The passage from Murtal into Ennstal via St. Michael - Trieben pass might have cost two additional days if the snow-covered Tauern Pass was impassable.

Research history

The Roman roots of Enns have been known since the Middle Ages. However, systematic and scientifically accompanied excavations did not begin until the early 20th century and continue to this day. During the first excavation campaigns, the investigation of the military camp received more attention than the civil town. More intensive excavation work, extending to all parts of the ancient area, began in the 1950s.

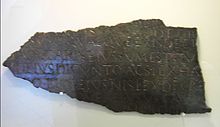

In 1321 the first known discovery of an inscription stone (tombstone) was made by the monk Berchthold from Kremsmünster during the renovation of the Lorch basilica. The ruins of Lauriacum were then mentioned by the humanist and Bavarian court historiographer Johannes Aventinus in his Bavarian Chronicle as " ... a large and powerful imperial city with a two-mile ring wall. " In 1765 one found u. a. a Roman mosaic floor that was lost again. In the early 18th century the remains of the wall are described by an English traveler, Richard Pococke . Kremsmünster Father Josef Gaisberger and P. Wieser carried out the first experimental excavations in the palace garden around 1851/52, which led to the uncovering of "pillared vaults"; it was the remains of a hypocaust of the camp bath. The vaults rested on pillars made of granite, under which was a floor made of crushed broken bricks. The pillars were recovered and then taken away. Essays on these excavations were written by Joseph von Arneth in 1857–1861 and published in 1856. Many small finds also found their way into the pockets of antique collectors and were thus lost to science forever, others ended up in private or public collections and were later brought together again by the Lauriacum museum association founded in 1892.

The inner area of the camp, which was almost completely undeveloped at the time, was excavated by Colonel Maximilian von Groller-Mildensee to 4/5 before the First World War . Around 1900, the foundations of the camp wall were uncovered in the area of the southwest gate at a depth of 1.5 m. From 1904, under the direction of Max von Groller's (KuK Limeskommission), scientific excavations took place for the first time, which he was to lead until his death in 1920. In 1904 z. B. three inward projecting intermediate towers and the corner tower in the north are excavated. In 1919 Groller edited and published reports and drawings by the engineer M. Niedermayer (today in the Schlossmuseum Linz), which were also the main sources for Joseph von Arneth. Most of the find drawings were also taken from this work. After the end of the First World War, Alexander Gaheis and Josef Schicker in particular did research in Lauriacum. In 1936 Erich Swoboda discovered the early Christian church built into the camp hospital .

After the Second World War (1951–1959) the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Upper Austrian State Museum ( Walter Jenny , Hermann Vetters , Lothar Eckhart ) dug together on the area of the civil town. In the first years after the Second World War, numerous building projects also made extensive documentation by Josef Schicker necessary, but this was never published. From the 1950s onwards, due to the increased building activity, there were again more reports of Roman finds, including the first evidence of Sigillata pottery in Mauthausener Straße. Ämilian Kloiber mainly researched the grave fields around Lauriacum . In the 1960s, Lothar Eckhart discovered the previous Roman building (peristyle house) under the St. Laurence Basilica, which was converted into a church in late antiquity. From 1964 on, the canal work allowed a more extensive archaeological investigation, as well as in 1976 when a new indoor swimming pool was built in Enns. A search excavation carried out by Lothar Eckhart in 1968 after the amphitheater of the legionary camp was unsuccessful. Since the 1970s, the Austrian Federal Monuments Office (BDA) under Hannsjörg Ubl has mainly carried out emergency and rescue excavations. In 1977 Hermann Vetters presented a newly revised plan of the camp, and in 1986 it was reworked by Kurt Genser . From 1994 onwards there were again large-scale excavations in the legionary camp itself, with new knowledge about the surrounding wall, the flag sanctuary of the Principia, the transverse hall in the south, the team barracks and the colonnades lining the Via principalis . For the first time, it was also possible to detect civil structures that had been erected in the last decades of the 4th century. Due to ceramic finds, the continuous settlement of the square could be up to the 7th / 8th centuries. Century can be confirmed beyond doubt.

From 1995 to 2004 an ancient settlement area could be recorded that extends to Kristein. Between 2004 and 2006 around 150 burials were recovered in the “Kristein-Ost” cemetery. A burial field was laid out here even before the legionary camp was built, cremation burials outweighed simple burials in the ground, individual ancient components refer to larger grave structures ( columbaria ). The ancient road surface could also be observed in several places. The burial place seems - with a few exceptions - to have been in use until the Middle Imperial Period (100–300 AD). A dense occupancy could be found especially on Kristein-Ost. It was noticeable that the graves hardly overlapped, so they must have been marked at the time. In the former “Mitterweg” corridor (today's Johann-Hoflehner-Weg), body graves were dug, some of which were sunk near the mid-imperial settlement horizon. In the northern area, a larger craft square was excavated, the so-called "pottery quarter" of the civil settlement. The extent to which the civil settlement and the late antique burial ground overlap cannot yet be determined with certainty. 2003–2006 the old village center of Lorch, at the northern tip of the legionary camp, was dug. In 2007, the excavation trenches of the north gate tower of the porta decumana were found during construction work at the Walderdorffstrasse intersection - near the Bleicherbach .

The Plochbergergrund excavation between 2013 and 2014, archaeologically examined parcels 103, 100 and 101, carried out by the Archeonova excavation company under the direction of Wolfgang Klimesch. The plots were fully exposed over a period of seven months and an area of 8005 m² was covered in this way. A total of twelve buildings and over 200 pits or trenches were found there. The excavators assumed that the area would be built in late antiquity (turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries). From 2014, the area between Pfanner-Werken (Fabrikstrasse) and Mitterweg, which was still undeveloped, was recorded geomagnetically and partly with georadar, and evidence of dense development with a network of paths, primarily small-scale artisanal settlement, as well as an as yet unknown grave road west of Lagerhausstrasse . In the course of a factory expansion of the Büsscher & Hoffmann company , in Lorch directly west of the train station, the civil town could also be examined more extensively in March to September 2015 directly north of the old legionary camp. A good 150 meters of a road that runs along the northern edge of the legionary camp was uncovered on an area of approx. 12,000 m². In addition to several remains of buildings from the 3rd – 4th Numerous coins, ceramics, fibulae and metal objects were found in the 19th century. The Austrian Archaeological Service (ARDIG) carried out this archaeological excavation campaign in Upper Austria, which was the largest in terms of area at the time. The work was accompanied by excavations and an open day. The area was subsequently built over again. Since April 2016, archaeologists from the Upper Austrian State Museum and the University of Salzburg have been excavating one of a total of twelve Roman lime kilns in Lauriacum / Enns on the edge of the terrace facing the Danube.

Dating

So far, two inscriptions can be used to date the camp: A genius stone from September 18, 191 AD and the fragments of a building inscription from the Principia (staff building) from the early 3rd century AD. Their location suggests that it refers explicitly to the completion of the camp headquarters. With regard to the question of when exactly the legionary camp was set up and moved into, no definitive clarification has been reached to this day. It is possible that its construction was started under Commodus . The above Weihaltar of the highest ranking centurion ( Primus Pilus ) of the II. Italica, M. Gavius Maximus, was found in the canteen of the high altar of the Lorch basilica, so probably not at the original location, it could rather come from Albing . The camp was perhaps largely completed as early as 191 AD; the building inscriptions recovered in 1904 and 1907 suggest that the last interior of the camp was completed around 205 AD. At the location of the vicus (Bundesstrasse 1), the archaeologist Hannsjörg Ubl was able to uncover a building that, according to the evidence of the coin finds, must have been built before the camp was founded. Ubl assumed that it was the first building of the Canabae legionis and not the vicus , since the latter did not extend so far to the west at that time. It was probably created about ten years before the legionary camp was completed. From this finding, the excavators drew the conclusion that construction of the camp should begin around AD 185, the consecration of the flag shrine took place around 191, the Principia were completed in AD 201 and the entire camp around the year 205 AD It is most likely, however, that construction began under Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211 AD), but that construction was only finally completed under his successor Caracalla (212 AD).

development

Pre-Roman times

The fertile soils of the Traun-Enns-Platte have been used for agriculture since the Neolithic Age. After a great wave of Celtic immigration in the 4th century BC At a ford across the Enns, the Celtic oppidum Lauriakon first emerged . According to evidence of the small finds and five coins from the later Iron Age, the Celtic settlement appears to have developed into one of the most important marketplaces in the region in the last two centuries before the turn of the millennium. However, their exact location has not yet been determined. It is believed to be on the ridge, directly below the current town center of Enns. Since excavations are not possible here at the moment, one is dependent on chance finds. In the urban area of Lorch / Enns and the area of the civil town of Lauriacum itself, no relevant indications or traces have been found so far. Only on Georgenberg was an indigenous settlement along the Limesstrasse (today Mauthausener Strasse) and a temple recorded for the 1st century AD. In the Stadelgasse there were other pre-Roman building structures that were in use until the middle of the 2nd century AD.

1st century

Due to the favorable location, a Roman trading post was established as the first outpost under Augustus (27 BC-14 AD). The Romans probably also built a military station or bridgehead to secure the Enns crossing. The road connected the Lentia fort with the St. Panthaleon / Stein fort, which was discovered in 2017. This secured the crossing of the Danube into the Aist valley . An important trade route and gateway for invaders. Perhaps the base on the Enns was occupied by members of the Legio XV Apollinaris (find a tombstone). There could also be another explanation for this: Either the deceased was a soldier who was passing through or was only assigned here for special tasks. After Noricum was officially incorporated into the empire as a Roman province under Claudius (41–54 AD), its Limes had to be reinforced. A large number of wood and earth forts were built along the Danube, which were occupied with auxiliary cohorts . There is no evidence of such an attachment for Lauriacum.

2nd century

A period of peace lasting around 100 years brought an enormous economic and cultural upswing for the region. The first traces of Roman settlement can be found at the northern foot of the Georgenberg , along the old road over the Ennsbrücke (today's Stadlgasse and Mauthausner Straße). They go back to the end of the 1st century, they are simple living and working places in half-timbered construction.

Under Hadrian (117-138), the Roman settlements of Ovilava (Wels) and Cetium (St Pölten ), which were a little further back, were raised to cities ( Municipium ), their territory extending as far as the banks of the Enns. The ever increasing long-distance trade required, above all, a further expansion of the road network, in the course of which the main inner-Norwegian route, which connected the province with Aquileia and the Limes Road, was expanded, the Enns was spanned with a solid wooden bridge. At the same time, a vicus developed on the Plochberger grounds , whose inhabitants, according to the evidence of the finds, must soon have been relatively wealthy. The Celtic indigenous population can be traced back to the Roman Empire. A certain Privatius Silvester had a tombstone chiseled around 100 AD for himself and his daughter Privatia Silvina, who had died at the age of twelve. It is designed according to the Roman model, the inscription in Latin reports on father and daughter, both have Romanized names, but still wear the local costume. It is possible that a stone fort for an auxiliary cohort was built here under Antoninus Pius - as in neighboring Lentia ( Linz ) - but such a fort has not yet been found.

3rd century

After the bloody Rome marcomannic wars was clear that the Noric limes section with the places very confusing, consisting of vast swamps and forests terrain on the north bank of the Danube could not be adequately protected without permanent deployment of a whole legion. Therefore, around 200 AD, the newly established Legio II Italica was first relocated to Albing , but then from there soon to the Enns camp.

The stationing of a whole legion brought with it not only a renewed economic upswing, but also some major administrative innovations for the province. The legion commander ( legatus ) belonged to the senatorial class and thus automatically took over the agendas of a governor . Its official title was legatus Augusti (or Augustorum ) pro praetore provinciae Norici (or Noricae ). The governor was supported by his 100-strong officium , which was made up of members of the legion. He belonged to the rank of former praetors and usually rose to the consulate after his tenure . The camp also advanced to become the official residence of the Norican governor. Some departments of the provincial administration were moved from Virunum to Ovilava , which Emperor Caracalla (211-217) - who perhaps had also visited Lauriacum on this occasion - had meanwhile elevated to a colonia (first-order municipal law).

Lauriacum was now the largest army base between the neighboring legionary camps Castra Regina and Vindobona and was therefore equipped with a well-developed military and civil infrastructure. The canabae legionis soon emerged north of the camp , a first pioneer settlement for the relatives of soldiers, craftsmen and traders who either came here as part of the legion or who moved here a short time later. A rapidly expanding civil town developed west of the camp, which was given lower town charter under Caracalla (211-217).

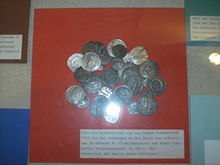

The heyday of Lauriacum, where probably more than 25,000 people lived, ended in the middle of the 3rd century. Destruction that could be traced back to war events is particularly evident in the civil town. After a long period of peace, it was hit by several catastrophes in close succession, which could also be confirmed archaeologically or through careful observation of coins. When the Juthung invaded the town between 213 and 234 AD, the city burned down for the first time, but was then immediately rebuilt. In 270/71 it was plundered again by migrating Juthung crowds and largely destroyed. The camp also suffered severe damage in this attack. A coin hoard from Ennsdorf dates from this time, the coins of which end with Quintillius. This catastrophe also obviously had no lasting consequences, since under Aurelian (270–275) the reconstruction was immediately started again on the old scale. Presumably, the civilian population was able to get to safety in good time, as the residential buildings could be repaired relatively quickly. For the renovation of the forum and the city thermal baths, however, the funds were no longer sufficient, they were probably given up and left to decay. Between 268 and 275 AD, the Juthungen once again plundered and devastated the city and the camp , this time together with the Alamanni .

In the late 3rd century, building activity in the camp and in the city increased again. The province of Noricum was divided into two provinces (Ufer- and Binnenoricum) by Diocletian's imperial reform. The civil administration was now the responsibility of a praeses (governor) who had his official seat in Ovilavis . Departments of Legio II were moved to other locations, which migrated larger groups of civilians. At the end of the century, the legion, which had been greatly reduced by assignments to the Comitatenses or to other Norican castles, was subject to a Dux limitis that was exclusively responsible for the military interests of the provinces of Noricum-Ripense and Pannonia I assigned to it. In addition, a patrol boat flotilla, the classis Lauriacensis, was stationed in Lauriacum .

During this time, St. Maximilian von Celeia , a traveling bishop from Noricum Mediterraneum (roughly today's Slovenia ), is said to have come to Lauriacum . He founded a Christian community here and is also considered the city's first bishop. According to legend, he died a martyr's death in his hometown of Celeia / Celje , because he refused to take part in the sacrificial cult of the old gods. The governor Eulasius had him beheaded on October 12, 281 or 284.

4th century

The presence of two emperors, Constantius II (341 AD) and Gratian (378 AD ) , proves that Lauriacum was still of supraregional importance in this century . The location also appears in the Notitia Dignitatum . Constantius II had a decree ( rescript ) drawn up here on June 24, 341 , which was included in the important collections of laws Codex Theodosianus and Codex Iustinianus .

In the early 4th century, Lauriacum became the scene of the only martyrdom of a Christian saint recorded from Ufer-Noricum. In the course of the Diocletian persecution of Christians, Florianus , the former head of the chancellery (ex principe officii praesides) of the Norican Praeses Aquilinus, died on May 4, 304 after he had been thrown from the Enns Bridge with a millstone around his neck.

Under the reign of Emperor Constantine I (323–337) and his sons, Lauriacum experienced a last, brief boom, which is particularly evident in stone carvings and the grave goods of this time. In the civil town, there was once again a lot of building activity, in which the previous building scheme changed fundamentally. The newly created main street was accompanied on its north side by an approx. 5 m wide arcade, which made the floor plan of the old forum trapezoidal. Instead of the half-timbered buildings of centuria II there was a representative large building (basilica?). All these building measures were probably connected with the stay of Constantius II, who had arrived in Lauriacum on June 24, 341 as part of an inspection trip . A monument was also erected in his honor, a marble head of which has been preserved.

Around 350 the civil town was again badly damaged by a fire, who was responsible for it is unknown. The reconstruction was tackled again immediately, but lasted until the reign of Valentinian I (364-375). The last major renovation and reinforcement of the fortifications (towers and gates) of the camp took place under his rule. The bricks for this were supplied by the Second Italian Legion, which operated two large brick factories in Schönering near Wilhering and St. Pantaleon. The construction work may have been ordered by his son Gratian (367–383), whose presence in Lauriacum at this time is also documented in literature.

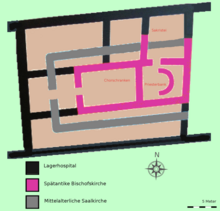

Christians living on the Noric Danube are mentioned for the first time in 304 AD. After the recognition of the Christian cult as the state religion, a Christian community established itself in Lauriacum , which in the late 4th century built a church in the ruins of the former camp hospital (later the Maria am Anger church). During excavations under the Basilica of Lorch , another early Christian church building was found, in which the relics of the companions of Florianus may have been venerated. So far, they are the oldest archaeologically proven churches on the Austrian section of the Danube. The Vita Severini also mentions the head of the community, Constantius von Lauriacum , who is the only early Christian bishop in Austria known by name .

The design of the grave monuments in particular shows that the population structure was subject to major changes during this time. The first novels probably migrated from Lauriacum as early as the end of the 2nd century after being destroyed . In the 4th century, however, a large part of the wealthier also apparently left the city, who were always the clients of larger and more elaborately designed grave structures. The recycling of old materials suggests increasing impoverishment and a shift in religious attitudes. At the same time, more and more Germanic elements come to the fore in the grave goods. From the last third of the 4th century onwards, settlement activities decreased significantly, the suburbs were largely abandoned, and the civilian population probably withdrew to a large extent behind the walls of the legionary fortress, the regular occupation of which had already greatly decreased in number through detachments. Instead, burial grounds were created in the abandoned civilian settlement areas.

5th century

In 401, the Vandals probably burned down again on their way to Gaul, the city and the camp, which were nevertheless partially rebuilt afterwards (e.g. the church in the camp hospital). In 451 Lauriacum was plundered by the army of Attila, king of the Huns, moving to Gaul . After the heavy defeat of the Huns and their allies in the Catalan fields , they then almost completely devastated the city and camp on their journey to Italy. The reconstruction measures were limited to the most necessary repairs or the construction of modest new buildings made of wood and clay, which were no longer based on the old floor plans. When the rest of the civil town, which was already in a bad state of disrepair, burned down a little later, the last inhabitants fled or saved themselves in the former legion camp, which was gradually transformed into a fortified small town ( oppidum ). The vicus also seems to have been abandoned at the turn of the 4th to the 5th century.

With the dissolution of the last remnants of administrative and army structures in the middle of the 5th century, the Roman rule over Noricum ends after almost 500 years. Lauriacum became the vanishing point for the novels who fled Quintanis (Künzing) and Batavis (Passau). After evacuation of almost all Castle residents on the upper Danube by Severin it was the last major stronghold of the novels in the west of the province. Despite a successful night attack by the Alamanni , it was clear that this fortress could no longer be held in the long term. Severin therefore settled with a large part of the Provençals even further to the east, to the Favianis, who had to pay tribute to the Rugians under their King Feletheus . From there, after Severin's death (482), most emigrated to Italy around 488 on the orders of the new ruler in Ravenna , Odoacer , king of the skiers . But today it is considered certain that in the legionary camp a residual population, even if numerically not very large, persevered and adhered to their Christian-Roman traditions. This is supported by the use of the grave field at Ziegelfeld until the 7th century and the discovery of a warrior grave from the 8th century.

Early Middle Ages - Modern Times

In a report on the stay of Worms Bishop Ruprecht around 696 in Lauriacum it is - like the bishop's residences in Worms and Regensburg - referred to as civitas ("city"), which suggests a greater regional significance of the place. The wall of the legionary camp must therefore have been largely preserved in the early Middle Ages and have fulfilled its fortification function. The local field name "The Castle" testifies to this. Within the fort, the area around the former camp headquarters was called “ In der Pfalz ” ( etymologically, palatium = palace). A larger group of novels was also represented here. The trip of the head of the church to Lorch is, however, controversial due to the fact that it was recorded much later, as well as whether he still encountered an intact Christian community there. The continuity of the settlement can be recognized primarily by the retention of the place name, which reappears in a Franconian document from 791 as " Lorahha ". The Frankish king, Charlemagne, assembled his army in Lorahha in September of this year for his first campaign against the Avars. Lorahha was - it seems - continuously inhabited from the time of Severin to the establishment of the Avarian Mark by Karl, settlement activities from the 6th to the 8th century could be proven on the basis of finds (ceramics). After the smashing of their empire, Lorahha was from the year 805 one of the market places where, under the supervision of a Frankish Comes (border count), the Avars and Slavs were officially allowed to trade. In 900 a fortification was built to protect against the Hungarian invasions. Most likely, it was mainly a matter of repair and reinforcement work on the old camp wall, which was able to fulfill its protective function until the High Middle Ages . Its importance as a border fortress ended with the establishment of the Babenbergermark from the year 976. In economic terms, however, the favorable location of the settlement at the mouth of the Enns became increasingly important due to the rapidly increasing trade with Hungary, Eastern and Southeastern Europe after 1060. The camp wall is likely to have existed - at least in part - until the 16th century. Their final destruction was probably not caused by the effects of the war, but rather by neglect, natural decay and the stone robbery for the expansion of the city of Enns, which finally began increasingly in the High Middle Ages (after 1212). A particularly large amount of the building fabric was destroyed during the Thirty Years' War when Erdschanzen were thrown up on the former camp area. Then the field of ruins was systematically ransacked and plundered by treasure graves until well into the 19th century - similar to Carnuntum . The today demolished church Maria am Anger, which was once integrated into the hospital of the legionary camp, was a late antique episcopal church and was preserved until 1792. It is named in the 12th century as the " Church of St. Mary in Lauriacum Castle " and was granted parish rights. The associated cemetery was laid out in the 10th century. The St. Laurenz basilica developed from a church in the late antique civil town.

Auxiliary fort

Efforts had been under way since the 19th century to find the legionary camp's predecessor. The archaeologists Friedrich von Kenner (1834–1922) and Alexander Gaheis (1869–1942) suspected it to be in the “… area of the great fortress” , while the amateur archaeologist and terra sigillata specialist Paul Karnitsch (1905–1967) tried in the early 1950s also in the reconstruction of this fort. After some excavation investigations on the brick field (Hanuschgasse / Zieglergasse), south of the legionary camp, Karnitsch believed to have found two buildings of the canabae of the auxiliary camp there, which is why he suspected a camp in the form of an oblong , northeast-oriented rectangle, because: "... the The shape of the area was drawn out according to the defined part of the ditch and the existing streets. ” Karnitsch also calculated an area of 71.04 × 124.32 m, i.e. s. 8831.69 m² without making any claim for the accuracy of his analyzes. With regard to the crew, Karnitsch came to the conclusion that only a small crew with a crew of perhaps two centurions (centuria = 100 men) could have been in this auxiliary troop camp. To date, however, no inscription or other find is known to confirm the presence of an auxiliary force prior to the arrival of the Legion. Kenner, too, was convinced that Emperor Vespasian (69–79) could not have left the mouth of the Enns entirely without military protection. As proof of his thesis, he used a tombstone from the 1st century on which a soldier of the Legio XV Apollinaris , T. Barbius A. f. Quintus (see also section development / note 7). However, these views were resolutely contradicted by Ubl and Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger due to the lack of solid archaeological evidence. Since large-scale archaeological excavations are excluded due to the modern overbuilding of the area in question, this matter will probably not be able to be resolved satisfactorily in the near future.

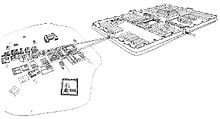

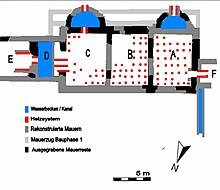

Legion camp

| Findings plan of the legionary camp |

|---|

| Seipel, W. Upper Austria border region of the Roman Empire. Special exhibition of the Upper Austria. State Museum in Linz Castle. , 1987 |

|

Link to the picture |

Most of the camp ( castra legionis ) is now built over or parceled out. In the diagonal between the north-west ( Porta praetoria ) and south-east gate ( Porta principales sinistra ) it is cut through by the route of the western railway.

The floor plan of the multi-phase camp (3 construction periods) was rectangular, with rounded corners (playing card shape) and measured 538 × 398 m, which corresponds to an area of approx. 21.5 ha. With this length it was significantly smaller than the first two campsites of the II. Italica in Lotschitz (SLO) and Albing . The conglomerate rock from the Georgenberg and the granite from the so-called Tabor near Enghagen were used as building materials. The SW-NE orientation of the fence essentially followed the course of the terrace edge, which slopes steeply towards the Danube, in the north and the bank of the Bleicherbach in the west. These natural conditions probably prompted the architects to lay out the storage area as a skew-angled rectangle with a deviation of seven degrees; the interior alignment of the building structures therefore does not meet at exactly right angles. The northern edge of the terrace also determined the course of the decumanus maximus . The course of a section of the enclosing wall and its two upstream ditches can still be traced along the line Römergraben - Bahnhofweg - Teichweg - Lorcher Straße.

The following buildings are known of the interior development:

- the Principia with camp forum,

- the Praetorium,

- the Legate House,

- the officers' quarters,

- Barracks for a total of ten cohorts,

- Barracks for special forces

- the multi-phase camp bath,

- Bazaar-type farm buildings, and that

- Camp hospital.

The area of the fort was divided by a right-angled cross between the two main streets of the camp ( Via principales and Via praetoria ) aligned with the four gates . The main gate was facing the enemy, from here the via principalis led to the main building in the center of the camp, around which the other residential and functional buildings were grouped. The approximately nine meters wide via principales , along which a column colonnade ( porticus ) ran (twelve column bases could still be found in situ in 1908 ) divided the complex into two halves, the front area ( praetentura ) and the slightly larger, rear area Area ( Retentura ). At the level of the Principia, the 160 m long colonnade met an adjacent building to the north (the vestibule of the Principia). Behind the colonnade there were a few more rooms, but their function could not be clarified. Exactly in the center of the camp, the pebbled via principalis intersected with the second main road, the 6.5 m wide via praetoria .

In addition to crew and officer accommodations, the Principia with its flag sanctuary, the camp thermal baths, the hospital as well as administration, workshops, storage and utility buildings were uncovered. A building adjoining the principia in the northwest was probably also used for administrative purposes ( quaesturium ). Another extensive complex on the Via principalis was interpreted as the residence of the camp commandant ( praetorium ). In the southern camp area, rubble columns were discovered that probably belonged to the so-called legate house, the residence of the governor.

On the south-east side of the main street of the camp stood the elongated tribune houses, which served as accommodations for the staff officers of the Legion. To the east of the tribune houses was the camp thermal bath, the interiors of which were divided into a cold, warm and sweat bath. To the north, across the street from Via praetoria , was the camp hospital. Little is known of the buildings north of the hospital. Their remains were destroyed when the western railway line was being built. It is possible that there were magazines and granaries ( horrea ) there. Other wall sections could once have belonged to stable buildings or other farm buildings. The remains of a bazaar-like commercial building and the accommodation of the Immunes , craftsmen or other specialists were also found.

Layers of destruction, which perhaps go back to Juthungen (270–271) or Hun incursions (451) (although still controversial in the professional world), were repeatedly replaced by renovation measures that can be traced back to the early Middle Ages. The construction scheme and structure of the buildings were changed significantly. It has not yet been clarified whether the heavily decimated legionary garrison in the late period of the camp - as is also known from other forts on the Noric Danube - also withdrew to a remnant fort . Lothar Eckhart observed so-called trickle wall trains in the southwest corner on the foundations of the defensive wall that had been completely removed there. According to Hermann Vetters, this could be an indication that only the eastern camp area was used, possibly as a refuge. Some of the camp's buildings seem to have been in use until the Carolingian era.

Wall and moat

The foundation of the encircling wall ( vallum ), consisting of mortared bulk masonry, was about two meters wide and up to one meter deep. In the excavation reports, Groller-Mildensee particularly emphasized its "excellent quality". The wall itself had an average width of 2.10 m and was probably around 6 m high. Its inside consisted of roughly hewn blocks from conglomerate rock extracted from the area (0.88 × 0.47 × 0.47 m). Behind the north wall, the one to two meter wide gravel inner rampart road ( via sagularis ) could be excavated at a distance of 15 m . A sewer lined with bricks with a bottom up to 65 cm wide could also be followed next to Wallstrasse, which then led under the wall to the outside. In Geschwister-Walderdorff-Strasse (southwestern camp wall), a remnant of the support ramp, which was piled up at the rear and which also supported the battlements, was found.

In front of the south-eastern wall, after a berm about 2.5 m wide, there was a double pointed ditch ( fossa ). The inner one was somewhat narrower or shallower (depth approx. 2.8-3 m) and was also somewhat higher than its outer counterpart (depth approx. Five meters), which was probably flooded or completely flowed through by the Bleicherbach. A striking part of the outer trench - 15 m wide and four meters deep - is still preserved today at the northwest corner (north of the western railway line). The trench system was estimated to be 24 meters wide. Near the western wall of the legionary camp, a twelve meter wide and 3.4 m deep section of the trench with a trough-shaped bottom could be observed.

This ditch was largely preserved until the 18th century and was fed by the Bleicherbach.

Towers and gates

The fort wall was reinforced as standard with internally attached, square intermediate towers, north-south side seven towers, west-east side six towers. Together with the four corner and eight gate towers, their number amounted to a total of 36 towers. The intermediate towers were in line with the wall.

Of the four gates, only the one in the southeast, the Porta principales dextra , has been explored to some extent. In 1900 a 75 cm long stone block was first found from this gate, which was interpreted as part of one of the gate towers. In the same place a "... barren fragment of an inscription " was found. The square southern gate tower measured 8.75 × 4.3 m, starting from it the enclosing wall 123 m with two intermediate towers could be followed. In 1908 the northern gate tower was also uncovered, which followed after a gate passage divided by a central pillar ( spina ) at a distance of 12.75 m. The two passages had a width of approx. 5.5 m. In 1920 the outer front of one of the two gate towers, consisting of large stone blocks, was exposed. The flank towers of the gate systems cantilevered about 2 to 2.5 m outwards.

The north-east ( Porta praetoria ) and north-west gates ( Porta principales sinistra ) were destroyed during the construction of the western railway line, and it is believed that they originally reached a height of around 20 m. The south-west gate ( Porta decumana ) is built over today and is therefore inaccessible for excavations until further notice. A canal was found north of the porta decumana , which discharged the wastewater into the Bleicherbach.

Principia

Of the internal camp buildings, the command and staff building is the best explored. It stood at the central survey point of the camp ( locus gromae ). Here was an approximately 630 m² large tetrapylon , the main entrance to the building complex. If you entered the 5447 m² Principia, you first came to a 42 × 48 m courtyard surrounded by a colonnade ( portico ), the flooring of which consisted of a pounded gravel ceiling, followed by an approx. 60 cm high wall that was spaced apart from six meters the pillars, which stood on ashlar plinths, carried; the portico itself was six meters wide and had limestone slabs on the floor. In the south of the courtyard, in front of the flag sanctuary ( sacellum / aedes ), there was a hall-like building wing ( basilica ) covered with a tiled roof. In 1906 fragments of column shafts and capitals of the portico that had been exposed in its eastern area were found. In 2006, during construction work in Kathreinstrasse, its approximately one meter wide cast masonry was cut.

After the hall one entered the actual core building, which was divided into eight chambers, the middle one served as a sanctuary with flags. The troop coffers, the imperial statue, the standards and the eagle of the legion were kept here. Here one found the building inscription of the camp, which had been laid in a second use as a floor slab. Due to the different screed heights, Groller divided the main wing into two room groups, Buildings H and M. A coin hoard was found in two heating hoses: in Building M a find of 75 silver coins of Constantine coinage; the other comprised 325 bronze coins. At a doorway, two parts of an inscription plaque were reused as a threshold. It was the building inscription that is used today to date the completion of the interior of the camp.

In the south-eastern area of the Principia, a castellum , a water distribution lock, was also uncovered; it consisted of a square wall made of broken clay bricks in clay mortar and clay soil; a tubule formed the drainage pipe to which a pipe made of wooden pipes connected to iron well boxes. In 1997, in room 1 in the southwest corner of the Principia, a built-in hose heating system was found above a terrazzo floor, the corresponding floor was missing. In 1998 the terrazzo floor of the flag sanctuary was examined; a coin on the floor of the adjoining room dates the last renovation work to a period between the middle and the end of the 4th century. Next to the Principia there was an 89 × 44 m (3916m2) building with an inner courtyard. It could have served as a magazine.

Tribune accommodation

A building complex on the Via principalis , which was cut in 1908 and connected to the colonnade, was further exposed in 1912–1913. Groller assigned the rooms, some of which were equipped with hypocaust heating, to the scamnum tribunorum (living quarters of the six camp tribunes). Two truncated columns suggest that there was also a portico (colonnade) here. A building wing in the north could also be interpreted as a magazine or workshop. Presumably, the buildings had undergone several functions and alterations during the 300-year existence of the camp.

Barracks

The elongated team barracks were oriented in an east-west direction and had been built according to the standard scheme customary at the time. The 0.6 m thick outer walls were made of rubble stones, the partition walls were built using wickerwork ( Opus craticium ). In 1911 barracks excavated near the Principia , south of the Via principalis , it became clear that the foundations consisted of coarse pebbles in a clay compound, on which the rising walls of conglomerate rock, limestone and granite rubble sat. The floor screeds consisted mostly of mortar with brick fragments; sometimes simple heating systems were also installed. Each bedroom for six to eight men ( contubernia ) had two additional rooms as an anteroom, weapons and storage room. They were arranged in rows of ten and could accommodate a whole hundred ( centuria ). For a long time it was assumed that the head structures for the centurions' quarters were missing here; in this camp they did not seem to have been accommodated with the teams, as is usually the case. Subsequent excavations by Hannsjörg Ubl showed, however, that these definitely existed, but that the earlier excavators obviously did not interpret them correctly. The head structures consisted entirely of solid stone masonry, which was almost completely removed in the course of the medieval stone robbery. The highest ranking of the centurions, the Primus Pilus , was housed right next to the Principia. The barracks in the NE corner of the legionary camp, today cut through by the Western Railway and not yet built, had no end structures. The Legion's special forces ( immune ) may have been housed here. This is supported by the fact that they were close to the port and the recently discovered battery of lime kilns.

The barracks of the 1st cohort were located southeast of the Principia and had a more varied floor plan. Each 8 legionnaires shared accommodation. It consisted of a 14 m² storage and weapons room and an approximately 18.5 m² bedroom and lounge. Each barracks should have been divided into 14 such chambers. The first cohort is likely to have been around 700 men. In the area south of the Via principalis , six more crew quarters (buildings VII – XII) were excavated in 1913. To the north of Barrack XII, there were findings from an older building with a hypocaust heating system, which had been partially built over by the barrack. To the north of it was an unobstructed square. From 1996–1997 terrazzo floors and walls of barracks buildings could be documented in two search cuts. In front of a cellar excavation, there were four rows of chambers whose foundations and screeds had also been well preserved. The layers also showed that the earliest construction phase had been destroyed by fire; the next phase was raised with the same orientation. The main street of the camp, the Via principalis. was lined on both sides by the porticoes of the barracks buildings. The streets between the barracks were gravel. Based on the findings from 1912 to 1913, Groller accepted a total of 14 crew barracks for the outermost retenture .

Storage boiler

A building structure that was excavated as early as 1852 and called a hypocaust was examined again in 1908, recognized as part of the camp thermal baths ( thermae ) and the findings documented. With an area of 3000 m², it was the largest Roman bathing building ever discovered in Noricum. Furthermore, the strings of the sewers leading out of the plant could be followed up to the main sewer on the Via principalis . There were also several traces of heating hoses to the west of the camp bath, which Groller attributed to later buildings. In 1913 further surveys were carried out in the area of the camp bath. In the south-east, the remains of three prefurnias of the bathing building were recognized. Structures of an apsidal building were also located, the remains of which were made of mud brick and provided with two layers of painted plaster. Many pieces with remains of wall painting were also found in the vicinity. The course of the walls of the western room E (water basin) could be determined by probing with iron rods.

The camp thermal baths were of the so-called row type and their equipment and structure were very suitable for a high number of visitors. The main entrance was probably in the north on a 2500 m² walled courtyard, the sports and practice area of the thermal baths ( Palästra or Basilica Thermarum ). Perhaps it was originally covered as well. It is possible that there was also an entrance with a portico on the east side, on Via praetoria . The building was oriented to the NE – SW and formed a somewhat warped rectangle measuring 48 × 60 m on a side. Compared to other military hot springs, it was of the normal size for a legionary camp, but it was probably a bit simpler.

On the west side one found one arranged side by side

- Cold bath ( frigidarium / room C), 12 × 21 m), about the same size

- Laubad ( tepidarium / room B), as well as a 16 × 21 m extensive

- Hot bath ( caldarium / room A).

All three rooms were equipped with heatable water basins on the west side. In room C the basin was in an apse, in rooms A and B, however, in two square annexes. Room A was also heated by the large heating chamber in Room J; hollow bricks ( tubules ) were attached to the side walls, which diverted the hot air from the hypocaust upwards through the wall. A 5 × 3 m block of wall may have been the basis of a water tank in which it is estimated that up to 45,000 m³ of water could be heated. Two small chambers still above the dividing wall of J and A were probably also water reservoirs. The basins in A and B were drained through a 0.4 m wide sewer that was connected to the main canal on the main road of the camp.

Hermann Vetters regards the adjoining, elongated room G as a dressing and undressing room ( apodyterium ). According to Alexander Gaheis, it was also equipped with a shallow water basin, which was probably used to wash feet. A 20 × 4 m basin in the 36 × 15 m large room H was probably the cold water basin ( natatio ), it was probably a bathing hall that was covered by a brick barrel roof. A wing close to the SE corner of the bath complex was interpreted as living space for the stokers, since the fire in the prefecture had to be constantly monitored and wood had to be added. A large communal toilet ( latrina ) was found in the north corner of the building complex . Rooms 2–5 were relaxation rooms, rooms 1 and 7 probably served as storage rooms or as a kind of tool shed. Hermann Vetters believed that he could determine at least three construction phases based on the floor plan.

Camp hospital

The sanitary building ( valetudinarium ) measured 95 × 67 m (6365 m²) and was located directly on the Via principalis . Its 60 treatment and hospital rooms, about 30 m² in size, were grouped around an inner courtyard, followed by a corridor that connected to the outer suites of rooms. It was probably equipped with running water, heating and a latrine. The building could accommodate around 400 sick and wounded people. The name of a doctor ( medicus ) of the Legio II Italica , Caellius Arrianus, is also known from an inscription . He probably came from Northern Italy, joined the Legion around 165 and served in Lauriacum until he was retired . Another camp doctor, Tiberius Claudius Saecularis, left his name stamp on an ointment pot. The finds from the camp contained probes, spoons, tweezers and scalpels, which documented the high level of medical care for the legionnaires. In late antiquity, the east wing was used as a church and episcopal episcopium .

Fabrica

Craft businesses, the production of which caused fire and flying sparks, were usually located in the camp villages. Those who z. B. were indispensable in a siege, had their locations in the camp. From 1914 to 1916, Colonel Groller excavated a 47 × 37 m (1739 m²) building in the northern part of the camp that once stood directly on Wallstrasse. Inside was a large amount of molten metal lumps of copper and bronze. There were probably some melting or casting furnaces here in Roman times. Wood ash was everywhere on the ground. Groller interpreted two adjoining rooms as work rooms. Based on these findings, he was of the opinion that he had discovered the remains of the Lauriacensis scutaria shield factory mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum ( fabrica scutaria ) . Behind the Principia there was a 37 × 12 m (444 m²) building, which was also equipped with melting furnaces (finds of crucibles and slag), probably also a metalworking workshop.

garrison

No evidence of a predecessor of the Legio II Italica has yet been discovered. A soldier of the Legio XV Apollinaris is mentioned on a tombstone, but this finding alone is not enough to locate a first century castle here.

The following occupation units could be detected for Lauriacum :

| Time position | Troop name | comment | Illustration |

| early 3rd to 5th centuries AD |

Legio secunda Italica (the second legion of the Italians) |

Most of the brick stamps and inscriptions go back to the activities of the legio II Italica , whose vexillations from Lauriacum also took part in numerous work assignments or military actions throughout the empire. | |

| 4th to 5th century AD |

|

In the course of Constantine I's army reform in the early 4th century, the Legio II Italica was split up into several, independently operating units, which were either taken over into the Comitatenses or distributed as a limit to other Noric forts ( Schlögen , Linz ).

In the Notitia Dignitatum the late antique occupation units for Lauriacum (including the workers of the shield factory) are listed, which were under the command of the Comes Illyrici (Count of Illyria) and the Dux Pannoniae Primae et Norici Ripensis (military leaders of Pannonia I and Ufernoricum). The javelin throwing unit was probably originally part of the Legio II Italica . She was enlisted in the Illyrian field army sometime between 395 and 420. In 1508 a building inscription - now lost - is said to have been found in Ybbs , which tells of the building of a burgus in 370 by auxiliary soldiers from Lauriacum under the command of a certain Leontius. This unit is not mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum. The stone was allegedly discovered directly on the banks of the Danube. Every now and then it is mentioned that it should originally come from Enns. The fleet members stationed in the camp were called Liburnarians ( Liburnae ) after their barge-like boats , performed primarily the tasks of pioneers and were also used for patrols on the Danube ( Danuvius ). |

|

| 5th century |

|

According to the Vita Sancti Severini , the defense of Lauriacum was probably taken over by a vigilante at the end of the 5th century . She regularly sent out patrols and guarded the walls. Whether it could have been a troop of legion veterans or Germanic federates is not clear from the sparse information in the vita. Apparently the bishop (Constantius) residing in Lauriacum directed the defense of the settlement in the legionary camp. |

Figurine of a late Roman officer of the 5th century, Museum Lauriacum

|

Civil settlements

The civilian settlements spread north, west and south of the legionary camp. They covered the area between Stadtberg, Kristein, Eichberg and Enghagen. The settlement areas to the west, south-west and south of the camp are referred to in research as

- "Civil town",

- "Pottery Quarter" and

- "Plochbergergrund settlement / Stadlgasse".

The sections to the west and south stood on a gravel terrace. At the time of their greatest expansion in the 3rd century, they covered an area of around 85 hectares. Since 2014, the areas north of the legionary camp in particular have been investigated using geomagnetic measurements. Their data provided numerous new insights. Between the Pfanner factory premises and Mitterweg, densely built-up Roman settlement areas, areas used by craftsmen and a network of paths could be identified. The measurements were largely confirmed by subsequent excavations. Much of the area of the city center west of the legionary camp lies under the cemetery of the Basilica of St. Laurence and is not accessible for archaeological research. Despite the findings of related fragments of inscriptions, the legal status of the civil town has not been secured, as the inscription finds that have become known to date do not name any officials or administrative structures required for this. Destruction shortly after 250 marks the beginning of a downward trend that ends in the late 4th century with the abandonment of the settlement areas outside the legionary camp.

The settlement area was divided into six zones by the archaeologists:

- Zone 1/2: They are located to the west and south of the legionary camp on a raised gravel terrace and their larger buildings are recognizable with wall paintings and elaborate heating systems. Public buildings (e.g. forum and thermal baths) in Zone 1 are likely to be the area that - possibly - was raised to the rank of Municipium under Caracalla (211–217 AD) . The remaining areas remained under military administration ( canabae ).

- Zone 3: It was located on the western periphery of the camp or in the north and is characterized by smaller buildings (mine huts, smelting furnaces and earth cellars). They were often equipped with economical installations.

- Zone 4: Its area consists of pit huts and earth cellars in a wood-earth construction.

- Zone 5: This part of the civil settlement housed numerous melting furnaces.

- Zone 6: Located on the Kristeiner Bach and a now silted up river ox. The port of Lauriacum must have stood here, the existence of which is secured by the mention of a fleet prefect in the Notitia Dignitatum , but was not localized until the most recent geophysical surveys.

Canabae

On the somewhat lower north bank terrace facing the Danube, there was a little-explored smaller settlement with widely scattered groups of houses that in places reached as far as the side arms of the Danube at that time. The buildings were much simpler, if at all, only one room had a heating system, the walls were made of wood or timber framework with mud plastering. The area was also used for agriculture. Finds of Roman masonry north of the legionary camp were found early on. Above all, the street leading out of the main gate, discovered in 1920, suggested a settlement area on both sides of it. Sigillata finds were documented by Erwin Ruprechtsberger in the 1980s. From 1994 the research took place in large-scale excavation campaigns by the Federal Monuments Office and resulted in the uncovering of streets and evidence of a loosened settlement structure. During inspections it was found that this extended to today's alluvial forest on the Danube. In 2006, remains of Roman settlements were identified east of the camp. The final results of the archaeological investigations indicated two major destruction events in this civilian settlement.

As early as the middle of the 2nd century, gravel roads and buildings were built north of the legionary camp and oriented towards the camp; this fact points to the planned construction. The creation of this canabae legionis probably took place with or before the completion of the legion camp. The extent and chronology of the settlement were only partially understandable. In addition to the residential buildings, workshop buildings and kilns could also be observed. Most of them were half-timbered buildings with additional timber frame structures that have several construction phases; fire horizons and leveling layers could also be determined on them. The last Roman building activities can be dated to the first half of the 5th century. Settlement layers and masonry findings also came to light a little south of the legionary camp. South of the legionary camp, some remains of the wall came to light again during excavations in the ancient grave field at the so-called brick field, but also continuous layers of settlement. At many sites where the canabae were found , they were reused as burial sites after the settlement was abandoned.

Vicus

The earliest Roman settlement could be made out along Limesstrasse (Stadlgasse), on today's Mauthausener Strasse and Reintalgasse. Possibly it was the building of a street station because it was at a traffic junction. The finds all date back to the late 1st century, long before the legionary camp was built. Little is known about its extent; in the west (south of today's Stadlgasse) there was a cemetery (mostly cremation burials) that was abandoned around the middle of the 2nd century. Around this time, however, there was increased construction activity in the vicus, along the Stadlgasse half-timbered houses were built, which stretch on both sides to Mauthausener Straße and overlay older structures. The ceiling fresco " Amor and Psyche " , which is now in the Enns Museum, comes from these houses . Among other things, the trading house of the barbers from Aquileia in the Lauriacenser Vicus also seems to have had a trading post that exported salt, iron and precious metals from Noricum . From the middle of the 4th century the houses were abandoned; but only in very few cases could it be determined that this was caused by fire. Later timber frame constructions could no longer be precisely classified chronologically. In their area there were also body burials from later periods. The development structure investigated in 2013–2014 immediately south of Stadlgasse showed a strip-shaped parceling, in which the buildings are oriented with their narrow side facing the street. However, it was not the classic strip house development, but corridor houses. The development was loose with relatively large gaps between the individual buildings. In addition, different construction techniques could be identified. There are corridor houses with stone foundations, as well as buildings with a foundation layer made of wooden beams in which only one room was built on a stone foundation.

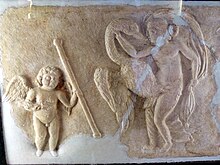

Ceiling fresco: As a special gem, an almost completely preserved Roman ceiling fresco is exhibited in the Enns Roman Museum, which comes from the house of an obviously wealthy citizen on the southern edge of the older vicus of Lauriacum . The ceiling fresco was recovered from the ancient rubble in the 1970s in a painstaking seven-year process and was partially reassembled. Although all parts of the fresco were there, it could not be completely finished because the restorers would have needed another ten years and - as is so often the case - no more funds were granted for it. The 4.80 × 5.80 m fresco is geometrically structured by strong lines. The main part of the picture is occupied by a medallion with a floating group of people. It is connected to the edge zone, in which animal figures and flowers are depicted, by broad lines that divide the entire fresco into several smaller picture fields. In the four corners of the verge you can see the allegories of the four seasons.

According to the usual interpretation, the central medallion depicts the couple Amor and Psyche, whose love story is passed down in Apuleius ' novel "The Golden Donkey" ( Asinus aureus ).

Municipium

The largest and most important civil settlement developed along two streets that point towards the south-west gate of the camp. Since this coincides with the via principalis of the camp, the city may have developed at the same time as the legionary fortress. The two main streets were connected by some cardines . On the southern edge of the built-up area there was a thermal bath, an adjoining building with apses is interpreted as a meeting house of a youth association ( collegium iuventus ). In the west, houses and warehouses, workshops and small businesses (pottery) expanded. According to Hermann Vetters, the extensive and complex excavation findings made it possible to differentiate between a total of seven development phases and six layers of destruction.

The civil city is also remarkable in another point: In contrast to the other Roman cities of comparable size known in Austria, it did not emerge from an older, indigenous settlement, but was evidently - just like the camp - also laid out according to plan (see also Planting city ). It is also noticeable that the division into insula and a uniform street grid such as B. in Virunum / St. Veit or Flavia Solva / Wagna near Leibnitz or Cetium / St. Pölten, here, at least not recognizable at first glance, was present. The development was mostly loose and irregular, the buildings more like small farms than urban building complexes. It was dominated by a scattered arrangement of groups of houses or individual buildings with magazines, small shops, workshops and handicraft businesses that mainly produced for local needs. Most of the timber-framed buildings had only one upper floor, and some of their rooms could be heated. In addition, there were larger villa-like houses with hypocaust heating , house heaters and elaborate, comfortable furnishings up to polychrome (multicolored) frescoes.

Its first phase naturally falls into the Severan period when the legion camp was established. It has several groups of houses surrounded by streets (so-called Centuriae ) with an area of approx. 90 × 90 m, which were raised in half-timbered construction. The city center was formed around today's Basilica of St. Laurenz and the Lorcher cemetery that surrounds it, just below the northern spur of the Georgenberg, situated on an alluvial terrace on the left bank of the Enns and southwest of its confluence with the Danube. This level descends to the west in the direction of Kristeinbach and borders on the Stadtberg and Eichberg in the south. The trade routes converging from all directions in this region favored the rapid development of the camp city (in addition to the presence of the 6,000-strong legion).

Centers of public life were u. a. the Forum ( Forum venale ), the city thermal baths and some smaller temples that were situated on the eastern edge of the city, near the legion camp (today the St. Laurenz cemetery). According to Lothar Eckhart, the Capitol with the Temple of Jupiter was located on the site of today's Lorch Basilica. The “city center” was also not particularly densely built up, which is particularly astonishing since Caracalla presumably granted the place second-order city rights ( Municipium as opposed to Colonia ).

The roads, some of which were provided with a canal system, only had a simple gravel surface. At the roadside, residential and commercial buildings were lined up, some of which had porticos . Water pipes, which took up some springs on the Eichberg, supplied the city with fresh water or the demand was met from house wells. Most of the buildings were made of stone, others were half-timbered and had only stone foundations. Some of them were heated by hypocausts and equipped with wall paintings or stucco decorations. In some cases there is also evidence of frescoed ceilings. Bronze plaques were attached to the public buildings such as B. the document of the city charter whose fragments were found together with 11 other fragments from other panels during excavations. The city's theater, presumed to be on the northwest slope of the Eichberg, has not yet been discovered.

In the densely built-up western part of the city, mainly storage buildings ( Horreum ), residential and commercial buildings were observed, and a Jupiter Dolichenus temple stood on a small square . In the Mitterweg area, the so-called “pottery district”, a collection of handicraft businesses, was excavated. These production facilities, which are located on the outskirts of the civil town because of the high risk of fire, could be identified primarily by their kilns, which were dug into the gravel soil. The pottery kilns (partly still with false fire residues) and some metal smelting furnaces (slag residues) were originally protected from the weather with simple wooden stud roofs ( post pits ), and they were also surrounded by walls. However, many of them could not be clearly assigned to their function.

Another focal point of public life was the southern part of the city with taverns and a bathing building of the so-called "row type" (see below). A house equipped with apses and three large, heated halls in the west was probably the meeting place for the city's militarily organized youth association ( Collegium iuvenum ). Further to the south-east of the city, there were a number of groups of buildings in a loosely structured structure that stretched to the foot of the Eichberg . Along the Roman road leading further into the Ennstal, which ran through a depression between Eichberg and Stadtberg, there were larger residential buildings, some with luxurious interiors. Settlement continued even further west of the core of the civil town in the form of loose buildings.

In the 5th century, the civil settlement was destroyed several times and finally largely abandoned, most of its residents probably withdrew to the camp. In the ruins, only temporary emergency shelters were built by a group of novels (Severin's refugees from Raetia?) From the area of the upper Danube. These people buried their dead right next to their huts, while the ancestral oppidum population continued to bury their dead in the brick field. The presence of Germanic groups could also be seen in the finds.

Legal status

The assumption that the settlement was actually given the lower town charter ( Municipium ) in the early 3rd century is still controversial among experts. Hartmut and Brigitte Galsterer are of the opinion that the related bronze plate fragments (see illustration) were transported from another town to Lauriacum to be melted down as scrap metal in the shield factory. Their theory is essentially based on two points, namely that no city councils or the place name are mentioned in the inscription and that the fragments in terms of typeface and type of metal ( lead bronzes ) also have a different quality. Metallurgical investigations by the Atomic Institute of the University of Vienna have meanwhile confirmed the inhomogeneity of the fragments. Furthermore, no municipium Lauriacum is mentioned in the numerous inscriptions found in Enns . The ancient historian Ekkehard Weber , on the other hand, advocated the status of the civil town as a municipality ; he was convinced that the corresponding inscriptions must be found in the city center - presumably under the St. Laurence basilica. The o. E. The theory of procrastination is not comprehensible for him, the different quality of the fragments could - in his opinion - be due to a fire disaster or something similar. In addition, Lauriacum was the seat of a bishopric in late antiquity . As a rule, these had their residences in the important and larger cities, as at that time they had mostly already taken on administrative functions.

Forum Venale

It was the hub of the city's public and business life. The 57 × 64 m large forum venale (Centuria I) was the large market square of the civil city, which essentially consisted of a courtyard enclosed by buildings and colonnades. In the west there was a market hall ( basilica ) equipped with underfloor heating . In the middle of the 40.8 × 28.5 m large square - according to findings of bronze fragments, according to conclusions - there was also a life-size, bronze emperor statue. Next to the forum stood a little temple with the front facing the street as a place of worship for a no longer known deity.

Centuria II

On the opposite side was the Centuria II with a larger administrative complex that was built in late antiquity. Shops and craft workshops were also housed here. Among them was u. a. the house of a snail dealer in whose shop the remains of a cleaning basin (purgatorium) could still be found. In Constantinian times, the building complex of Centuria II was torn down and replaced by a 60 × 40.4 m half-timbered building with a central projection, partly heated halls and a U-shaped hall structure. In the inner courtyard there was a podium (tribunal) , which was probably used for jurisdiction.

City spa