History of the Italian Army

The present-day Italian state was created during the Risorgimento in 1861 when the old Italian states were incorporated into the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont ruled by the Savoyards . The last king of Sardinia-Piedmont, Victor Emmanuel II , was under this name, and while maintaining this number, the first king of Italy . The Piedmontese institutions were then extended to the whole of Italy and renamed "Italian", which is why almost all the institutions of today's Italian state are older than the latter itself.

The Italian army celebrates its "birthday" on May 4th each year, the day the Piedmontese army was renamed the "Italian Army" ( Esercito Italiano ) by a ministerial decree of May 4th 1861. The renaming does not represent a historical break, it merely documents the expansion of the Piedmontese army . The older (Piedmontese) regiments of the Italian army, some of which are well over 300 years old, as well as some branches of the army (the Carabinieri founded in 1814 or the Bersaglieri established in 1836 ), are the bearers of the traditions against which the Italian army sees itself today .

The origins

It was the Italian philosopher and military theorist Machiavelli who, in his work Der Fürst 1512, was the first in Italy to publicly call for the formation of standing armies or at least the creation of militia groups that were to be recruited from the ranks of the citizens of the respective states. He sharply criticized the mercenary armies who inflicted material and especially social and moral damage on Italy. Changing assignments for different princes and their mercenary leaders often led to a lack of discipline among the mercenaries.

Towards the end of the brilliant Italian renaissance , Italy became the pawn of foreign powers for 300 years and fell into disrepair. Only a few Italian states were able to escape this development, including the Republic of Venice , which fought against Saracens and Turks in the eastern Mediterranean for centuries , and the Duchy of Savoy with its traditional army.

The Counts of Savoy already provided their own contingents of troops during the crusades , which had distinguished themselves in Damascus and Thrace , among others . Under Duke Amadeus VIII in 1430 and 1433 a comprehensive legal and organizational framework was created for the first time for the feudal militias in Savoy and the mercenary troops in Piedmont . Under Charles III. did not succeed in these armed forces in the Italian wars to protect the duchy from the almost complete occupation and devastation by French, but also by Spanish and German-speaking troops of the Habsburgs .

In 1545 Charles III. his military gifted son Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy in the service of Emperor Charles V , in the hope that one day his duchy to come this way again into total possession, which at that time almost all of Piedmont , Savoy to Lake Geneva and the County of Nice had included. Emanuel Philibert, to whom the emperor gradually transferred civil and military leadership tasks, finally defeated the French at St. Quentin with his Spanish troops on August 10, 1557 . This success enabled Emanuel Philibert to enforce the liberation of his duchy in the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 , with the reconstruction of which he began that same year. He moved the capital to Turin and reorganized administration, finances, the university and the military.

1560-1690

Emanuel Philibert issued an edict on December 28, 1560 , with which he ordered the establishment of a militia army that was very progressive for the time . The duchy was divided into eight recruiting districts, each of which had to provide a 2,400-strong infantry unit . From the rural population, the most capable men between the ages of 18 and 50 were selected, who were trained every Sunday on arquebuses , pikes and halberds . Most of the equipment they had to pay for themselves; the duke paid for the bodyguard , cavalry , artillery and fortress garrisons . In the absence of a uniform , the soldiers wore a blue sash as a sign of identification in the first few decades (Italian officers still wear it with their parade uniform today ). In total, the militia had a military strength of around 20,000 men. With a few exceptions, she managed without mercenaries.

Emanuel Philibert's successor pursued a dangerous policy of expansion. In changing alliances they took part in the wars of the major European powers in order to expand their state territorially. Charles Emanuel I fought for the city of Geneva from 1581 to 1602, ultimately unsuccessfully , from 1588 to 1601 for the Margraviate of Saluzzo , between 1612 and 1631 for Montferrat , 1625 and 1631 against Genoa and Spain, and in the Mantuan War of Succession against France . Until 1648 the duchy had to be prevented from becoming the venue of the Franco-Habsburg power struggle during the Thirty Years' War .

In order to adapt the militia originally created for defense purposes to the new political conditions, Charles Emanuel I divided it in May 1594 into a general defense militia ( milizia generale ) and a special militia ( milizia scelta ). For the 8,000 men of the special militia, the recruitment, training and mobilization regulations were tightened. In addition, Karl Emanuel also used mercenaries again. From 1615 the French, Swiss , Germans and others were assigned to the five regiments of the special militia for individual campaigns or formed "foreign regiments". From 1619 individual regiments were permanently preserved. These regiments, initially named after their owners , formed the basis for the small, solid and disciplined standing army ( truppe d'ordinanza ) in the 17th century , which was first comprehensively organized as such under Charles Emanuel II. In 1664.

Five of the eight permanent regiments (four were later disbanded and replaced by new regiments) were given that of a region or city of the duchy instead of the names of their owners. With this, the duke strengthened his authority over the previous owners. The guard regiment set up in Turin in 1659 , which much later assumed the name Granatieri di Sardegna , was given priority over some older permanent regiments in 1664 . The eight standing regiments were initially divided into up to 17, then into up to 25 small companies , in which no foreigners were allowed to serve.

In 1664 Karl Emanuel II introduced uniforms for the Guard Regiment with the azure-blue skirts typical of the House of Savoy , plus white collars and red trousers. In 1671 the infantry received gray skirts, the colors of the lapels and other details indicated that the uniforms belonged to the individual regiments. With the cavalry, the basic colors were based on heavy and light cavalry, the details in turn according to regiments. The uniforms of the artillery always remained blue. In 1672 all infantry regiments, which until then consisted of a third of pikemen, were fully equipped with muskets and bayonets . The switch to flintlock shotguns took place by 1690 . The saber was basically retained.

In 1685, the eight regiments were divided into two battalions each to better manage the many companies . The twelve regiments of the special militia had only one battalion. In 1685 the first grenadiers were introduced , which formed the battalion's elite companies and, after 1814 , were grouped together in the aforementioned guard regiment .

Towards the end of the 17th century, five cavalry regiments emerged from smaller cavalry units , three of which consisted of dragoons . Due to the high costs and the later practice of generally excluding smaller horses from military use, the Piedmontese cavalry remained relatively small in terms of quantity.

Some regiments of the standing army were disbanded by the end of the 18th century. Only the following regiments have remained active under various names up to the most recent times or still exist in the Italian army . It should be noted that the infantry regiments were divided from 1832 onwards to form brigades .

Infantry :

- Regiment "Du Cheynez" (1619), "Monferrato" (1664), "Casale" (1821), 11./12. Inf.rgt. (1839)

- Regiment "Fleury" (1624), "Savoia" (1664), 1st / 2nd Inf.rgt. "Ré" (1839) (1946: "S. Giusto")

- Regiment "Catalano Alfieri" (1636), "Piemonte" (1664), 3rd / 4th Inf.rgt. "Piemonte" (1839)

- Regiment "Guardie" (1659), "Granatieri Guardie" (1816), 1st Rgt. " Granatieri di Sardegna " (1852)

- Regiment "Lullin" (1672), "Saluzzo" (1680), " Pinerolo " (1821), 13./14. Inf.rgt. (1839)

- Regiment "Fucilieri di SAR" (1690), "Aosta" (1774), 5th / 6th Inf.rgt. " Aosta " (1839)

- Regiment "Nizza di SAR" (II) (1701), "La Marina" (1714), 7./8. Inf.rgt. "Cuneo" (1839)

- Regiment "Desportes" (1703), "Alessandria" (1796), "Acqui" (1821), 17./18. Inf.rgt. (1839)

- Regiment "La Regina" (1741), 9./10. Inf.rgt "Regina" (1839) (1946: "Bari")

- Regiment "Sardegna" (1744), "Cacciatori Guardie" (1816), 2nd Rgt. "Granatieri di Sardegna" (1852)

- (Regiment "Sarzana" or "Genova" (1815), "Savona" (1821), 15./16. Inf.rgt. "Savona" (1839))

Cavalry :

- Regiment "Dragons Bleus" (1683), "Dragoni del Genevese" (1821), "Genova Cavalleria" (1831)

- Regiment "Dragons Jaunes" (1690), "Dragoni di Piemonte" (1691), "Nice Cavalleria" (1832)

- Regiment "Cavaglià" (1692), "Piemonte Reale Cavalleria" (1692), "Piemonte Cavalleria" (1946)

- Regiment " Savoia Cavalleria " (1692), "Cavalleggeri d.Sav." (1819), "Savoia Cavalleria" (1832)

- Regiment "Dragoni di Sardegna" (1726), "Cavalleggeri d.Sar." (1808), to Carabinieri (1822)

- (Regiment "Dragoni di Piemonte" (1828), "Lancieri di Novara" (1832))

- (Regiment "Aosta Cavalleria" (1774/1831), " Lancieri di Aosta " (1832))

- (Regiment "Cavalleggeri di Saluzzo" (1849/50))

The artillery , which initially consisted of civilian skilled personnel , had already been transferred to the militia by Charles Emanuel I in July 1625. Charles Emanuel II reinforced the force and built an arsenal in Turin . In 1726 an artillery battalion was established, which consisted of four gunnery companies as well as a mine and a technical company. In 1743 it was enlarged to an artillery regiment, which was divided into heavy siege artillery and light field artillery . In 1775 this regiment formed the Corpo Reale di Artiglieria with artillery units that were directly assigned to the infantry and smaller special units .

1690-1814

Even after the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, France tried various power-political means to defend itself against the Habsburg embrace . This also included keeping the Dukes of Savoy in their own camp by controlling the fortresses of Pinerolo and Casale Monferrato . Tired of French tutelage, Viktor Amadeus II joined the Augsburg Alliance in 1690 after Louis XIV had previously forced the use of Piedmontese troops in Flanders and demanded the surrender of the citadel of Turin. The attempt to stop the following French invasion failed in August 1690 at Staffarda with heavy losses. In 1691 the Duke succeeded in defending Cuneo . Because the French were tied to the Rhine , Viktor Amadeus was able to advance into the Dauphiné in 1692 and besiege Pinerolo and Casale Monferrato in 1693. In October 1693 he was defeated by Marshal Catinat's troops in the Battle of Marsaglia near Orbassano , but the French did not take advantage of their success. Viktor Amadeus had lost the rest of his field army and was now waging a guerrilla war with his militia for years. In 1696 he concluded a territorially advantageous separate peace in Turin, which, however, politically tied him back to France.

For this reason, the duchy stood on the side of France and Spain when the War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701. In 1703 France suspected Viktor Amadeus of maintaining secret contact with Prince Eugene of Savoy , who had led the Austrian troops in northern Italy. Several Piedmontese regiments were disarmed on the orders of Louis XIV. In 1704, Viktor Amadeus declared war on France and Spain, whose troops were also in the Duchy of Milan . This was followed by a costly multi-front war that soon pushed the Piedmontese back into their fortresses, which they defended with extraordinary tenacity. The citadel of Turin, built by Emanuel Philibert in the 16th century, withstood several sieges. The French troops bound here were defeated in September 1706 in the Battle of Turin by Prince Eugene and Viktor Amadeus. Over the next five years, Piedmontese and Austrian troops repeatedly invaded southern France. The peace negotiations that began in 1712 ended with a great success for Viktor Amadeus: In 1713 he received Sicily, along with smaller areas in northern Italy, and thus the long-sought royal dignity. After the Spaniards landed an invading army on the island, against which the few Piedmontese associations had no chance, Viktor Amadeus accepted Sardinia and its crown as a replacement in 1720 .

In the War of the Polish Succession , King Charles Emanuel III fought . with his troops on the side of France. In 1733 he conquered Milan , in 1734 he fought with the French at Parma against the Austrians. The battle of Guastalla was decided mainly by Piedmontese militia units. At the end of 1734 the Piedmontese conquered Milan again, and at the beginning of 1735 Tortona . The peace brought territorial expansion in the east.

In the Austrian War of Succession , Sardinia-Piedmont was again on the Austrian side. Charles Emanuel III. liberated Savoy from the Spaniards in the winter of 1742 . In 1744 the French and Spaniards invaded Piedmont at the Stura di Demonte , but were so weakened at Madonna dell'Olmo that they had to break off the siege of Cuneo and retreat across the Alps under pressure from the militias. In the following two years the Piedmontese and Austrians fell on the defensive. The decisive factor was the Austrian success at Piacenza in 1746 . In 1747, the Assietta battle put an abrupt end to French expansion efforts.

In the course of the wars of succession, the Piedmontese army had grown to over 55,000 men, which represented a considerable economic burden for the not exactly prosperous kingdom with its 2.5 million inhabitants. The peace target strength was set at 30,000 soldiers after the end of the war; for cost reasons, the actual strength in the following decades was generally around 21,000 men. Initially, numerous “foreign regiments”, especially those with personnel from other Italian states, were dissolved. The ten national infantry regiments of the standing army, consisting of recruited or force-recruited soldiers, generally again had two battalions, the third battalions provided the militia in the event of war. The cavalry and artillery regiments remained almost unchanged. The special militia, renamed "Provincial Militia" in 1713, comprised twelve regiments again in 1752. They consisted of only one battalion, plus a large garrison company and, in the event of war, a second battalion. The provincial militia, which became part of the field army during the war, were recruited from men between the ages of 18 and 40 who were fit for military service. During their four-year service, they were called in for several short military exercises every year, otherwise they stayed with their families. All men capable of military service who did not belong to the standing army or the provincial militia formed the general militia during the war. It was organized in companies whose chiefs came from the bourgeoisie . During the war, these companies served as personnel reserves, protected special objects or carried out so-called partisan operations . Among other things, they served well during the siege of Cuneo in 1744. In the Alps, the general militia proved extremely useful, as the terrain favored their mode of fighting. The Waldensian militias were notorious and, in view of the persecution of Protestants, they always showed exceptional fighting power. The mountain militias were also valuable in the educational role, as they quickly provided precise information about troop movements in the Alps.

During the long period of peace until 1792, the Savoyans carried out some military reforms under the influence of the Seven Years' War . In 1756, the Royal Academy in Turin concentrated only on the training of junior officers . Viktor Amadeus III. opened the officer corps from 1775 to the bourgeoisie. Bourgeois officers with useful training and experience served primarily in the artillery and in technical units, while the nobility tended to command the infantry and especially the cavalry. Viktor Amadeus issued numerous regulations , but some of them were so detailed that they often stifled the independent initiative of commanders and subordinates. In 1774, he combined the artillery regiment with the artillery units of the infantry battalions and other smaller units that had existed since 1760 to form the "artillery corps". In 1774, a light infantry force , the Legione Truppe Leggere , was created, from which the Guardia di Finanza later emerged. This troop protected the borders in peacetime and pursued smugglers , in the war they secured the movements of the line infantry and took on reconnaissance tasks . It largely replaced the militia in these areas. In 1786 Viktor Amadeus set up two additional provincial militia regiments and another light infantry force, the hunters ( Cacciatori ), which a few years later distinguished themselves in the Alps. All regiments received a small hunter company in addition to their fusilier and grenadier companies . During the war, the hunter companies were strengthened and combined into independent battalions. In 1786 permanent command levels were established above the regiment.

By the end of the Wars of Succession, the uniforms of the armed forces and their regiments had diversified in color very strongly. In 1751, azure blue uniform skirts were introduced throughout the army , only bicorns , collars, lapels , buttons and other details remained different. In 1782 the army received new, 148 cm long rifles with 51 cm long bayonets .

After the French Revolution , Sardinia-Piedmont was also engaged in combat with French revolutionary troops from 1792 and took part in the First Coalition War . After the counties of Nice and Savoy were quickly lost, the Piedmontese army fought in the western Alps until 1796 , often on their own, as the Austrians were mainly interested in protecting their duchy of Milan . In 1796 the allies had to give way to the military phenomenon Napoleon . Piedmont was finally occupied and the army disbanded. The House of Savoy , with a few remaining associations and the tiny navy, withdrew to its possession Sardinia by 1814 , which had successfully defended itself against French invasion attempts in 1793 . Napoleon established a "Republic of Italy" dependent on him in northern and central Italy, which he converted into a kingdom in 1805, whose crown he wore until 1814. He set up an " Italian Army " for the first time , which fought under the Italian tricolor in the Napoleonic Russian campaign, among other things. Apart from name and color, this Napoleonic army has no direct reference to today's Italian army.

1814-1861

After the end of Napoleonic rule, Victor Emanuel I returned from Sardinia to Turin. In addition to Sardinia, Nice, Piedmont and Savoy, his kingdom, which now had four million inhabitants, also included Liguria , which the Congress of Vienna had struck him in order to establish an effective buffer state between France and the Austrian Empire . With an edict of May 21, 1814, the state order of 1796 and with it the army were restored. The Carabinieri troop was created in 1814 to safeguard the traditional social structure . As early as 1816, the recruiting system had to be reorganized according to the Napoleonic model in order to counteract the shortage of personnel and the heterogeneous composition of the officers 'and non-commissioned officers' corps. In 1821 there was an uprising against Restoration and absolutism in Piedmont , in which Crown Prince Karl Albert of Savoy and parts of the army were also involved. Some regiments were disbanded or renamed as a result and their military privileges were curtailed. The purges of 1821 resulted in an increase in the proportion of reactionary officers who placed antiquated regulations, befitting behavior and individual bravery in the foreground, while the precise study of modern military-scientific literature was dismissed as (subversive) bourgeois nerd. The negative effects on the leadership qualities of the staff officers and especially on that of the generals remained noticeable for decades. The artillery officers, who were always well-trained, remained excluded from this development, but they only achieved a position of priority in the generals much later.

From 1831, Karl Albert reformed his country as king (the Statuto Albertino from 1848 remained the Italian constitution until 1948 ) and also his army profoundly. The "Albertine reforms" shape the face of the Italian army to this day. Already in 1814 it was planned to use the old, z. Regiments named after the Piedmontese provinces. It was only Karl Albert's Minister of War, Emanuele Pes di Villamarina , that put this into practice. From the regimental staffs, brigades emerged in 1831, which took over the names and traditions of the old regiments, which in turn were divided and formed two new infantry regiments. The two new regiments were initially numbered 1 and 2, and then in 1839 they were numbered continuously. As a result (taking into account the incident of 1821) the following picture emerged for the army:

- Infantry (three partially active battalions and one reserve battalion per regiment):

- Brigade " Granatieri di Sardegna ": 1./2. Grenadier Regiment ("Guardie", 1659)

- Brigade "Re": 1./2. Inf.Rgt. ("Fleury", 1624)

- Brigade "Piemonte": 3rd / 4th Inf.Rgt. ("C. Alfieri", 1636)

- Brigade "Aosta" : 5./6. Inf.Rgt. ("Fucilieri", 1690)

- Brigade "Cuneo": 7./8. Inf.Rgt. ("Nice", 1701)

- Brigade "Regina": 9./10. Inf.Rgt. ("Regina", 1741)

- Brigade "Casale": 11./12. Inf.Rgt. ("Du Cheynez", 1619)

- Brigade "Pinerolo" : 13./14. Inf.Rgt. ("Lullin", 1672)

- Brigade "Savona": 15./16. Inf.Rgt. ("Genova", 1815)

- Brigade "Acqui": 17./18. Inf.Rgt. ("Desportes", 1703)

The provincial and general militia were abolished in their previous form in 1816. Since then, these and similar terms have only stood for personnel reserves for the standing army. In 1831 all independent hunter battalions were dissolved, while the hunter companies of the line regiments were initially retained. The elite troops of the Bersaglieri ( riflemen ), founded in 1836, were assigned to higher staffs as an independently operating troop. By 1859, each of the 10 infantry brigades had a Bersaglieri battalion.

- Cavalry (six, later five squadrons per regiment):

- 1st regiment "Nice Cavalleria" ("Dragons Jaunes", 1690)

- 2nd regiment "Piemonte Reale Cavalleria" ("Cavaglià", 1692)

- 3rd Regiment " Savoia Cavalleria " (1692)

- 4th regiment "Genova Cavalleria" ("Dragons Bleus", 1683)

- 5th Regiment "Lancieri di Novara" ("Dragoni di Piemonte", 1828)

- 6th Regiment " Lancieri di Aosta " ("Aosta Cavalleria", 1774/1832)

In 1832 the artillery consisted of eight divisions ("brigades", battalion strength), the few engineering troops were given the status of a branch of arms in 1824 .

Two infantry brigades, a cavalry regiment and artillery, genius and supply units formed a division (1-5) during the war. The cavalry regiments could also be combined into cavalry brigades or assigned to the two army corps (I and II). A division (with the guards) basically formed the reserve and was directly subordinate to the high command. After 1860 the lists of the Piedmontese regiments, brigades, divisions and army corps were simply extended. Structurally, the enlarged army remained essentially unchanged until 1918.

In 1832 the Piedmontese army had a peacetime strength of 31,594 men and 3,798 horses. 23,140 men (73.3%) served in the infantry, 4,674 in the cavalry (14.8%) and 3,027 in the artillery (9.5%). The low actual strengths of the units were detrimental to training, and during mobilization the officers could no longer cope with the high military strengths. In the case of mobilization, the target strength rose to 67,802 men, with general mobilization to 117,000 soldiers. 90% of the army was stationed on the mainland, where the units changed locations on average every two years. These problems and habits also persisted into the 20th century.

Wealthy and senior men were able to evade long military service by appointing voluntary substitutes ( surrogazione ) and paying a fee. The non-stop military service, which lasted eight years, was done by volunteers, substitutes, those born in Sardinia, unemployed and determined by lot. All other men capable of military service were members of the provincial militia for 13 to 16 years. Depending on the type of weapon, they served one to three years in an active unit, for the next six to ten years they belonged to these units as reservists and were only called up for a short military exercise once a year, for the last four to eight years they were in their reserve battalions Regiments assigned. Over time, the length of military service decreased continuously.

Since the Napoleonic era, a national feeling developed in Italy , which was in part bloody suppressed by Austria , which ( legitimized by the Congress of Vienna ) occupied Lombardy and Veneto and controlled the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (torture in the Bohemian fortress of Spielberg, 1848 Popular uprisings in Milan , Brescia , Venice and also in Cadore ). Under the leadership of Piedmont and his Prime Minister Cavour , with the support of volunteer corps Garibaldi , France and England succeeded in the Italian wars of independence from 1848 to 1870 to create the modern Italian nation state (vs. Metternich : "Italy Geographical term!"). Because of the political circumstances, the threat situation and the associated time pressure, it was not possible to build up a really new state apparatus that was as federal as possible in line with the circumstances in the various parts of the country. Instead, the quite progressive Piedmontese system of government and administration was transferred centrally to the whole of Italy in 1861, with fatal consequences, especially in those areas that were not subject to compulsory taxes or military service, that is, that could not do anything with the modern Piedmontese administrative concept and thus the King of Italy regarded only as another foreign ruler who proclaimed freedom, but even had to levy a tax on bread (meal tax) because of the hardship of the new state.

1861-1918

The armies of the other Italian states, like in Tuscany or in Naples, a z. Some had a long history of their own, were disbanded and incorporated into the Piedmontese army, which was now called the "Italian Army". In southern Italy in particular, the army continued to be referred to as "Piedmontese" after the unification and was fought in years of guerrilla warfare ( brigantaggio ), which the deposed Neapolitan Bourbons supported as best they could. The enforcement of general conscription proved to be problematic up until the First World War.

From 1860 onwards, the additional brigades of the line infantry were traditionally named after the provinces or cities from which the new contingents came. The "Alpenjäger" Garibaldi, a free charter group, became the Brigade "Alpi" (51st / 52nd Inf.Rgt.), After the occupation of the rest of the Papal States became the Brigade "Roma" (79th / 80th Inf.Rgt. ) educated. For political reasons, local recruitment of the line infantry was later dispensed with, which had a significant impact on their performance. The " Alpini " (1872) , on the other hand, were a real re-establishment .

From 1872 to 1877 the basic military service was gradually reduced from five to three years, which was seen as the absolutely necessary minimum. With a population of 25 million and an army of 200,000 men, general conscription was not equally feasible for everyone after three years of service. Following the Prussian model, the Landwehr and Landsturm were introduced as "Mobile Militia" and "Territorial Militia", which had existed in Sardinia-Piedmont for centuries under the names Provincial Militia and General Militia. Here those conscripts completed a short training course who could not or would not be integrated into the standing army. In addition, the militia also included the reservists who had served in the standing army and were then assigned to the reserves of their active units. The leading personnel of the militia came mainly from the contingent of one-year-old volunteers . The reintroduction of militia units to complement the standing army proved to be out of date. Even in Prussia, the Landwehr had lost a lot of its importance at the time. At best, the mobile militia could secure the rear space, the territorial militia even proved to be unsuitable for the internal police tasks assigned to it. Both survived until the First World War, but served primarily as a personnel reserve for the field army.

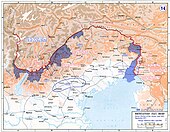

By 1914, the Italian army had 12 army corps (I-XII; with artillery , engineers , cavalry and Bersaglieri as corps troops ), 24 divisions (1-24), 47 line infantry brigades with 94 regiments (1-94) and a grenadier brigade with 2 regiments. The 8 alpine regiments were organized separately. The peace target strength in 1914 was 275,000 soldiers, the war target strength was just under 1,100,000 men, but the necessary equipment was lacking. During the First World War , the army was considerably enlarged in the course of general mobilization . In 1915 there were 35 infantry divisions (14 army corps), in 1916 the number rose to 43 divisions (18 corps), in 1917 to 65 divisions (26 corps), and in 1918 after the defeat of Karfreit, the number rose to 55 divisions (24 corps). There were also four cavalry divisions. The 30 cavalry regiments usually operated on foot, only in autumn 1917 and in autumn 1918 there were larger mounted deployments (see: List of Italian regiments ).

The Italian army was sent to war against Austria-Hungary (and from 1916 also against Germany ) by nationalist government circles and the crown against the will of the majority of the population and the members of parliament , although it was actually with Austria and Germany in the Triple Alliance was allied. Italy had signed this treaty in 1882 in order to reassure itself of its Mediterranean policy against France. In 1914, it justified its declaration of neutrality, with good reason, by stating that the Triple Alliance was an assistance agreement in the event of an attack by parties outside the treaty, whereas Austria had declared war on Serbia with Germany's place after the assassination attempt in Sarajevo . The Austrian Balkan policy had already harmed Italian interests in the Balkans and prompted both sides to take measures that contradicted not only the spirit but also individual provisions of the treaty. There was also tension because of the Italian claims to Austrian territories with an Italian majority in Trentino as well as in Istria and Dalmatia ( Irredenta ). The Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf , for his part, had been calling for and preparing a preventive war against Italy since 1907 .

The Italian Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna let his armies to the battle of Caporetto by old-fashioned methods and brutal applying disciplinary measures against the numerically inferior, but in defense of the Alps - and Isonzofront topographically clearly favored Austrian army run up. Both armies paid a terrifying blood toll , especially in the first eleven battles of the Isonzo . The German-Austrian breakthrough in the Twelfth Isonzo Battle and the collapse of the Italian front east of the Asiago plateau put Italy in an extremely critical position. The defeat, which was fortunately averted, resulted in a purification process in the Italian army. On the shortened front from the Alps via the Grappa-Stock to the Piave there were now fewer, but much better motivated soldiers, led by the new Chief of Staff Armando Diaz in a much more humane and modern way. The Austrian attempt to force a decision on the Piave in the summer of 1918 failed because of the will of these soldiers. In autumn 1918 the various peoples of the Danube Monarchy began to strive for independence. The weakened Austro-Hungarian army, however, fought with all determination until October 30, 1918, especially on Monte Grappa. In the Battle of Vittorio Veneto , which opened on October 24, 1918 , the Italians achieved a breakthrough on October 28, which resulted in the collapse of the Austrian mountain front. The Italian side was demonstrably not responsible for the delays in the armistice negotiations .

In addition to “completing the (territorial) unification of Italy”, the Italian army is also credited with having united the country socially. A total of 5.2 million Italian soldiers served during the war in Italy, the Balkans, France and in smaller secondary theaters of war. With a few exceptions, soldiers from all parts of the country were deployed in the military units, and the shared horrors of years of trench warfare and the critical situation immediately after Good Freit led to an unprecedented level of solidarity, especially in 1918. On the other hand, this process was faced with 680,000 dead and 1.3 million war invalids and wounded, as well as a political and economic crisis that conjured up fascism .

1918-1945

Towards the end of the war, almost all European armies began to disband the brigades and to place three infantry regiments under one division . In Italy this meant a crisis of the "Albertine" army structure and the traditional order and tradition. The two line infantry regiments of the brigades lost their common bearer of tradition and were in some cases quite arbitrarily subordinated to the division commands. All units and large units mobilized from 1915 to 1918 were disbanded, with the exception of the regiments of four line infantry brigades (“Liguria”, “Sassari” , “Arezzo” and “Avellino”), which had distinguished themselves during the war. In the period between the two world wars , efforts were made to motorize smaller parts of the army. In the 1930s, two infantry divisions ("Trento" and "Trieste" ) were motorized and two light tank divisions (" Ariete " and " Centauro ") were set up. The army reform of 1939 ( Ordinamento Pariani ) had catastrophic consequences. The military power of a country was then expressed by the number of its divisions ( Stalin : "How many divisions does the Vatican have ?). It had been Mussolini's intention to gain political influence through these numbers. He believed, also because of the indecisive The course of the war from 1939 to 1940 ( drôle de guerre ), not a long war and in his vanity wanted to secure his place at the negotiating table of the European powers through short-term and short-sighted maneuvers. The Army Chief of Staff Pariani helped him with his concern to put more divisions on paper In Pariani's view, the tripartite divisions were too cumbersome. Instead of making them more mobile through motorization, he took one regiment of infantry from each and thus laid the foundations for more divisions. At the same time, this also made it possible to restore the old Albertine order in the army structure When two line infantry regiments r should form a division together with an artillery regiment and other division troops, this could also bear the name of an old brigade and unite the traditional sister regiments under itself. This is how the originally numbered Italian divisions got names.

A look at the internal structure of these new divisions reveals bad things. In peacetime the third battalions of the infantry regiments were cadre of the traditional tripartite divisions . Only through mobilization were these to be replenished with reservists and the total number of infantry battalions in the division rose from six to nine. With the loss of one regiment per division (1939), the peace holdings fell from six to four battalions. The planned third reserve battalions of the regiments were replenished during mobilization, but were immediately called in to form completely new regiments and divisions.

So it came about that in 1940 the Italian Army entered World War II with numerous divisions that had only two infantry regiments with a total of four battalions, fewer than the old Piedmontese brigades of the 19th century. The divisional artillery regiment also had only two instead of three medium battalions, plus the heavy battalion and an anti-aircraft unit. The new operational doctrine required for this was neither properly completed nor practiced. It provided a linear approach into the depth of the room. One regiment was supposed to advance and in due course be replaced by the other (with the division's classic leadership tasks inevitably being transferred to the corps). For this, however, they had neither the necessary means of transport nor suitable supporting tanks. The level of training of the troops and their other equipment was completely inadequate. The war that Mussolini waged (despite warnings from Chief of Staff Pietro Badoglio , Armaments Commissioner Carlo Favagrossa and others) in accordance with his political calculations and without an overall military strategy had devastating effects on the morale of the troops. The two-part (so-called "binary") division turned out to be a completely wrong construction. Attempts were made to replace the missing third regiments by allocating fascist “ black shirt legions ” and infantry regiments of the so-called (number) series 300. The allocation of Bersaglieri regiments generally showed better results.

After the catastrophic course of the war and Mussolini's dismissal, Italy concluded an armistice with the Allies in September 1943 . Hitler then ordered the occupation of Italy and the disarmament of the Italian armed forces. Several Italian military units offered armed resistance as ordered. Especially in the Balkans the resistance of isolated associations ended tragically (cf. German massacre of the Italian “Acqui” division on the Greek island of Kefalonia ), elsewhere (e.g. on Sardinia ) one could assert oneself. Numerous Italian soldiers had to do forced labor in Germany as so-called military internees . The German approach led to the declaration of war by the Badoglio government on the German Reich in October 1943 . Parts of the remaining army decided to continue fighting on the German side, while five divisions ("Cremona", "Legnano", "Mantova", "Friuli" and "Folgore") took part in the war of liberation with the Allies. These five divisions formed the basis of the new Italian army after the war . With the abolition of the monarchy, it lost the attribute "royal".

1945-2005

Paradoxically, only ten years after its total collapse , the Italian army reached the highest level of performance in its history. There were three reasons for this: American military aid, a new understanding of the concept of training, and a sensible army structure. The main focus of the new army was in northeastern Italy because of the threat posed by the Warsaw Pact armies . There a total of three tank divisions , four infantry divisions (all with names and regiments of different "origins"; see also the list of large Italian units ) and five Alpini brigades were set up in three corps :

- III. Corps ( Milan )

- "Centauro" armored division ( Novara )

- Legnano Infantry Division ( Bergamo )

- Infantry Division "Cremona" ( Turin )

- IV. (Mountain) Corps ( Bozen )

- Alpine Brigade "Taurinense" ( Turin )

- Alpine Brigade "Orobica" ( Merano )

- Alpine Brigade "Tridentina" ( Brixen )

- Alpine Brigade "Cadore" ( Belluno )

- Alpine Brigade "Julia" ( Udine ) ("Julia" up to 10,000 men strong)

- V Corps ( Vittorio Veneto )

- Armored Division "Ariete" ( Pordenone )

- Panzer Division "Pozzuolo del Friuli" ( Palmanova ) (soon reduced to a brigade)

- Infantry Division "Mantova" ( Udine )

- Infantry Division "Folgore" ( Treviso )

In the event of a defense, the three corps should be subordinate to the NATO command "Landsouth" in Verona . There were also others in central and southern Italy, e.g. T. larger associations. For a certain time there was still a VI in Bologna . Corps with the infantry divisions "Friuli" ( Florence ) and "Trieste" (Bologna). The divisions of this corps were soon reduced to brigades and, together with the paratrooper brigade "Folgore" ( Livorno ; not Inf. Div. Of the V Corps), were placed under a regional command in Florence. In Rome was the infantry division " Granatieri di Sardegna ", in southern Italy the infantry divisions "Avellino" ( Naples ), "Pinerolo" ( Bari ) and "Aosta" ( Messina ), but they were gradually reduced to brigades and the functions of one Territorial armies. In particular, the infantry divisions in the north had three infantry regiments and tank units, one field artillery, one anti-tank artillery and one anti-aircraft artillery regiment, as well as other division troops .

The tensions with Yugoslavia because of the Trieste and Istria question and the Italian minority there, as well as the vivid memories of the expulsion of the Italian population from Istria and Dalmatia at the end of the war, led to war preparations in the mid-1950s. In Padua a staff of the 3rd Army was formed with the best heads of the generals , which should take over the command of the corps independently of the NATO command "Landsouth". (The 3rd Army led the corps on the lower Isonzo from 1915 to 1917. After Goodfreit, it was also able to retreat in an orderly manner to the Piavel line by sacrificing a cavalry brigade near Pozzuolo del Friuli , which it then defended. The 3rd Army was at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto was significantly involved.) Finally, the conflict was defused diplomatically in 1955 (return of Trieste) and completely resolved in 1975 by a treaty (confirmation of the course of the border, minority rights). Something similar happened in South Tyrol in the sixties, albeit with a different omen .

From 1955 until the great army reform of 1975, the operational readiness of the army fell steadily. Above all, the lack of funding for necessary modernizations and the relatively low actual status of the associations contributed to this. The 1975 reform, which brought Italy to the NATO brigade standard, meant a drastic cut for the traditionally regimental Italian army. Accordingly, the divisions should no longer be organized in regiments , but in mixed brigades with battalions . While the combined arms battle was previously only possible through the exchange of parts of the respective “monoculture regiments”, the brigades, mixed from the start, institutionalized this cooperation, so to speak, “from the start”. Although there were brigades in Italy before 1975, these were rather smaller divisions with a regiment and support units for special or territorial tasks. According to the new structure, the infantry brigades had three mechanized infantry battalions and one tank battalion, plus an armored artillery battalion. With the tank brigades it was exactly the opposite, but in Italian tank brigades there were usually only two tank battalions with one Bersaglieri battalion and one tank artillery battalion. The Alpini Brigades had three to four mountain infantry battalions and two mountain artillery battalions . This structural reform was implemented by transforming a number of regimental staffs into brigade staffs and by making the battalions independent. Has never been digested in the Italian army to transfer the regiment traditions and names on battalions, as well as the fact that a lieutenant colonel commander should be. So was in favorable cases z. B. from the 66th Infantry Regiment "Trieste" (which fought a legendary defensive battle near Enfidaville in Tunisia in 1943; today part of the airmobile brigade "Friuli" ) a 66th Infantry Battalion "Trieste", in unfavorable cases due to terminology related to the type of weapon, for example from the Cavalry regiment " Cavalleggeri di Saluzzo" a "squadron group Cavalleggeri di Saluzzo" (armored reconnaissance battalion). With the Alpini regiments, whose battalions and also companies are more independent, such contractions seemed entirely impossible. It was similar with the Bersaglieri. The 1975 reform continues to this day. The battalions were renamed regiments again from 1991, although they still only have battalion strength (there is similar in France and Great Britain). In 1986 the four remaining divisional commands were dissolved and all brigades were directly subordinated to the three corps or the military regions. Because of the natural spaces in Italy, this rationalization, in which the corps troops were reorganized and the brigades each received a logistics battalion, seemed sensible. In 1989 the army had 26 brigades (five tank brigades, nine mechanized and five motorized infantry brigades, five Alpini brigades, one airborne brigade and one rocket artillery brigade), which were subordinate to the three corps mentioned and five of seven military regions.

From 1991 to 1993, logistics troops directed Operation Pelikan , a humanitarian aid mission in Albania .

In 1991 the number of brigades was reduced to 19, the structure of the army remained largely unchanged. Far-reaching reforms in the entire armed forces took place in 1997. The army, which had been reduced to 150,000 men and 13 brigades, received new command structures, the corps staff new names and tasks, and the supporting areas and units were almost completely reorganized. The quantitative reduction did not initially bring any significant qualitative improvement in the equipment, because the defense budget in the 1990s served as a kind of quarry for other priorities. The higher proportion of well-trained regular soldiers who have been tried and tested in foreign missions had a positive effect. For the planned introduction of a professional army, the personnel and career structures were reformed and the army was also opened up to women without restrictions. After the dissolution of two other combat brigades ( Tridentina , Centauro ) in Northern Italy in 2002 and the continued good development of the volunteer share, nothing stood in the way of a suspension of compulsory military service on June 30, 2005.

Brigades of the Italian Army in 2000 |

Professional army

The actual strength of the Italian army remained above the target strength of 112,000 soldiers even after the conversion. Problems such as the excessive number of generals, staff officers and portepee non-commissioned officers who could no longer be used appropriately were foreseen. In the absence of special early retirement regulations or other alternatives, they often had to be “parked” in a wide variety of offices that were actually supposed to be closed. With regard to the team career, it had already been seen before the reform that the numerous volunteers from southern Italy were often only looking for a job or only wanted to serve the specified minimum period of service that had been introduced as a prerequisite for an application to the police .

This problem was counteracted on various levels: In addition to the already high hurdles for officer applicants, the university entrance qualification was also introduced as an entry requirement for higher non-commissioned officers. Motivated and qualified civilians who had been turned down due to a lack of vacancies were now trying to advance through the team career. In this way, the high school graduation rate was increased in this area. In the case of the remaining applicants for the team career, unsuitable volunteers were consistently rejected, which, given the sufficient number of applicants, did not result in any major recruitment problems. After a short time, a completely new, positive mood and a new self-confidence developed in the army, which was gradually registered in society, which now also paid tribute to the armed forces for their missions abroad. The proportion of well-trained volunteers who were not just looking for a job increased, as did the number of applications from northern Italy.

Due to insufficient funding for investments, plans were made to reduce the size of the army by around 10,000 soldiers as early as 2006. The insight that the high personnel costs are mainly caused by redundant older professional soldiers and not so much by young temporary soldiers resulted in a more cautious approach to downsizing.

See also

- Italian army

- List of Savoyard and Sardinian regiments of the early modern period

- List of major Italian associations

- List of Italian regiments

- List of Italian peacekeeping operations

- Italian war crimes in Africa

- History of the Italian Air Force

- Italian naval history

literature

- Georg Christoph Berger Waldenegg: The reorganization of the Italian army between 1866 and 1876. Prussia as a model. (Dissertation Heidelberg 1989; Heidelberger Abhandlungen zur Middle and Modern History, New Series, Vol. 5) Winter, Heidelberg 1992, ISBN 3-533-04531-5

- Hans Jürgen Pantenius: Conrad von Hötzendorf's idea of attack against Italy. A contribution to coalition warfare in the First World War. (Diss. Munich 1982, 2 vol.) Böhlau, Cologne, Vienna a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-412-03983-7 .

- Gerhard Schreiber: The Italian military internees in the German sphere of influence 1943–1945. (Ed. Military History Research Office , Freiburg i. B.) Oldenbourg, Munich, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-486-55391-7 .

- Stefano Ales: L'armata sarda e le riforme albertine (1831–1842). (Ed. Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore Esercito-USSME) USSME, Rome 1987.

- Nicola Brancaccio: L'esercito del vecchio Piemonte (1560-1859). Stabilimento poligrafico per l'amministrazione della guerra, Rome 1922.

- Vittorio Cogno: 400 anni di storia degli eserciti sabaudo e italiano - repertorio generale 1593 - 1993. Edizioni Fachin, Trieste 1995.

- Giovanni Antonio Levo: Discorso dell'ordine et modo di armare, compartire et exercitare la militia del Serenissimo Duca di Savoia. Turin 1566.

- Giorgio Rochat, Giulio Massobrio: Breve storia dell'esercito italiano dal 1861 al 1943. Einaudi, Turin 1978.

- Filippo Stefani: La storia della dottrina e degli ordinamenti dell'esercito italiano. (Ed. Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore Esercito-USSME, 3 vols.) USSME, Rome 1986.