Roman military camp

The Roman military camp ( Latin Castrum , plural Castra ; for: fortified place), also fort (from Latin castellum , diminutive of castrum ), was an essential element of the Roman army . The following statement has been passed down from Tacitus : “The camp is the special pride of the soldiers. It is their fatherland that is home to their soldiers ”. Military institutions, especially the castles, were the "physical manifestation of Rome" wherever the empire appeared in the world. In addition to its function as a starting point for military operations or as a short-term location before battles, the permanent garrisons in particular played an important role in the Romanization of the conquered areas due to their economic strength and their technical progress, which was previously unknown in many places. Numerous city foundations that still exist today go back to Roman military sites.

The size of the facilities was based on the respective requirements, with garrisons as well as supply depots. Military sites are also known that may have had special tasks to do, among other things. Another important factor for the size of Roman forts is the historical development in connection with the structural structures, as their appearance has changed significantly over the centuries due to changed military strategies.

swell

In addition to the archaeological excavations on the architectural remains, the written records in particular form an essential basis for understanding Roman camps. Two ancient writings on military theory are particularly important. One is an incompletely preserved short text entitled De munitionibus castrorum (From the fortifications of the forts), which comes from a collection compiled by a surveyor named Hyginus Gromaticus . Hygin, however, is not the author of this military writing of unknown origin. Therefore it is also referred to as pseudo-hygin in the specialist literature in connection with De munitionibus castrorum . The period of origin of this writing is associated with the 1st or 2nd century AD. The other work, Epitoma rei militaris (Outline of Military Affairs), is by Flavius Vegetius Renatus and was written in the 4th century AD. Vegetius draws on a multitude of sources, some of which are much older, that span more than half a millennium of Roman military history. However, since he does not name these sources individually, many aspects of a centuries-long development of the Roman army are mixed up in the scriptures to form a surrogate that is largely indistinguishable today. This font is therefore used very carefully in research. Another author, the Greek historian Polybius , gives details of Roman marching camps from the end of the 3rd to the middle of the 2nd century BC. His writings, the Historiae , deal with the period from 264–146 BC. He is known for his description of the rise of Rome, at that time still a republic, to the leading power in the Mediterranean area, and for his eyewitness account of the capture of Carthage in 146 BC. A hundred years later, Caesar mentions many details about the construction of the camps in his time. The military system of the imperial era becomes tangible through Flavius Arrianus , known as a historian during the time of Emperor Hadrian . In addition, documents, letters and certificates as well as stone inscriptions found during excavations are an important source.

Basic forms during the principle time

The permanent fort complexes of the imperial era had their origin in the field camps of the Roman Republic. These could be divided into two categories: marching and temporary camps, which also included winter camps ( hiberna ). Numerous camps from the late republic and early imperial era were adapted to the site and often had irregular floor plans. The internal development mostly followed a standardized pattern. The structure of such a camp was strictly standardized, as it had to be rebuilt in the evening after each march. For this it was necessary that the large number of people who took part in a military operation knew at all times what to do and how to find their way around the camp. These processes always followed the same mechanism, which made any kind of inquiries superfluous. Therefore, a quick and professional warehouse construction and dismantling was guaranteed even in exceptional situations.

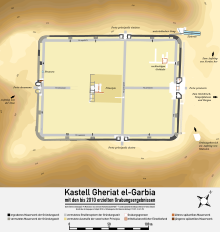

The observance of the rectangular or square basic shape as well as the interior development of a fort could already deviate significantly from the standard scheme in the lightly fortified, long-term camps of the late Republic, if the conditions made it necessary. In particular, the standing camps during the conquests in Germania at the time of Augustus (31 BC – 14 AD) deviate significantly from the standard concept in some cases. With the expansion and reinforcement of the borders during the following generations, the requirements will be handled much more tightly. With the social and political upheavals of the 3rd century, following fundamental military reforms, new, more individually manageable basic models for the construction of forts prevail, which not only try to make the best possible strategic use of the chosen location, but also in favor of the previous barrack-like garrison character abandon fortress-like construction methods.

The Roman forts of the early and middle imperial period were laid out according to an apparently highly standardized basic scheme until the 3rd century AD. In their layout they followed the principle of the older marching camps. The very often rectangular fortification of the camp had mostly rounded corners in which there were watchtowers. The area between the Via principalis and the Porta praetoria was called praetentura (front camp), the area between the back of the staff building and the Porta decumana was called raetentura (rear camp ).

In all four directions, a gate usually opened, through which the four main camp streets led at right angles and converged at the center of the fort. The most important arterial road was Via praetoria , which led to the main gate ( Porta praetoria ; 5). The Praetorial Front , the side of the camp facing the enemy , was also located there . The via principalis dextra and the via principalis sinistra led to the two narrow sides at the end of which the porta principalis dextra (4; the right gate) and the porta principalis sinistra (6; the left gate) lay. At the back was the Via decumana , which corresponded to the Porta decumana (7). At the intersection of the two main streets, called Locus gromae , after the measuring instrument Groma , with which the camp was measured from here, was the Principia (1), the staff building. The praetorium , the commander's house and the granary ( Horreum ) were mostly to the left or right of the staff building . According to Hygin, the Via quintana runs parallel to the Via principalis , but behind the median of the camp (Latera praeetorii) . Another important street is in the Intervallum , the space between the defensive wall and the adjoining interior of the fort. There the Lagerringstrasse (Via sagularis) leads around all the buildings of the facility. There could be a wide variety of facilities within the fortification, depending on the respective requirements.

Marching camp

The camp of Polybius

The evening marching camp of the Roman army, which is surrounded by ramparts and ditches, looks quite different according to the two traditional plans. That of Polybius in the 2nd century BC. The building block-like concept presented in BC is intended for a double legion, cavalry, allies, auxiliary troops and bodyguards, a total of 18,600 men. This blueprint of a square camp measuring around 600 × 600 meters (2017 Roman feet) with a gate on each long side, could also be calculated down to smaller troop contingents without difficulty. From the future location of the Praetorium , the Feldherrenzelt, the surveying of the area grid was started, whereby multi-colored flags were used in the area. The area in front of the general tent was called Principia . After this word, the camp road that intersected this square in its center was given the name Via principalis . This street at Polybios was about 30 meters (100 feet) wide. The Via praetoria , however, should only be half the width. To the left and right of the praetorium were the forum and the quaestorium . The tents of the partially mounted bodyguards, the Equites and Pedites extraordinarii, are also adjacent to the left and right . The twelve legionary tribunes were camped in front of these institutions along the Via principalis , six per legion . Behind these facilities, the location was intended for auxiliary troops of all kinds. On the opposite side of the via principalis , space was created for the two legions and for the allies. While the legionaries were staggered along the Via praetoria , the allies camped in the remaining space between the Intervallum and the legions. The interval, the remaining uninhabited space inside the camp by the troops, was around 60 meters (200 feet wide) at Polybios. The space was needed in order not to restrict the soldiers' freedom of movement in the event of a defense, to keep the tents out of the reach of projectiles and to keep the cattle and the booty safe.

The camp of the pseudo-hygin

Only many generations later, from the end of the 1st or 2nd century AD, is another ideal model for the Roman marching camp handed down by the pseudo-Hygin. The obvious differences between this camp and the camp of Polybius could indicate a conceptual development of the marching camps, which must certainly have existed, since the Roman army had been moving since the 2nd century BC. Chr. Had changed significantly in its structure and military technology. The 687 × 480 meters (2320 × 1620 feet) large rectangular night camp of the font De munitionibus castrorum , also equipped with ramparts and ditches, is intended for three legions, auxiliary troops and the imperial bodyguard, a total of around 40,000 men, and had rounded corners (playing card shape) . As the crew and area information already shows, this castrum was much more densely occupied than its Republican predecessor. The trench around the camp should be excavated at least five feet (1.50 meters) deep and three feet (0.90 meters) wide. The excavated material was then used to create an earth wall 2.40 meters (8 feet) wide and 1.80 meters (6 feet) high, which was located inwardly behind the trench and was intended to protect the camp. Depending on local conditions, turf and stones could also be used in the wall for fastening. The parapet had to consist of wooden posts or wattle. In the scriptures, the posts could refer to the pila muralia, which are sharpened on both sides and which were evidently carried on mules by every parlor community ( contubernium ) , the smallest unit of the Roman army. In front of the four gates, one of which was on each side of the complex, the legionaries had to dig short trenches (titula) slightly offset from the main trench , which were supposed to make it more difficult to penetrate the camp directly. The via principalis , which connected the inlets on the long sides ( porta principalis dextra and porta principalis sinistra ), should be measured with a width of almost 18 meters (60 feet). The porta praetoria facing the enemy on one of the narrow sides was connected at right angles to the via praetoria , which ran through the front camp, with the via principalis . Just behind the intersection that had Praetorium in Latera praetorii his location to find. This median should also house the auguratory for the acts of sacrifice and the tribunal for the commander's speeches. The tents of the staff and the imperial bodyguard (praetorians) had to stand next to it in the median . The outer areas of this part of the camp were to be reserved for the first legionary cohorts and the vexillarii (standard bearers) of the two privileged legions. In the praetentura , the legionary legions and tribunes had to be made way along the via principalis . Other facilities in this part of the camp were supposed to be the Scholae (meeting places ) of the first legionary cohorts. Then the cavalry quarters had to follow, and then the first legionary cohort of the not so noble legion. In addition, the forge (Fabrica) , the military hospital (Valetudinarium) and the animal clinic (Veterinarium) were housed in the front camp. According to De munitionibus castrorum , the navy, pioneers and reconnaissance planes also had their campground here. The latera praetorii should end at the back with the via quintana . The retenture began behind it . The quaestorium was located there directly behind the praetorium . In addition to the administration, this area was intended for the accommodation of the camp prefect. In addition, the auxiliary troops had to camp here and space had to be made for the booty and prisoners. The 2nd to 10th cohorts of the three legions, which were considered to be the elite, were housed with their tents directly along the wall, thus enclosing all other camp facilities. This is an important difference to the camp of Polybios, where not the legion, but the allies and auxiliary troops sat outside. Between the legionary cohorts in the outer zone and the wall, the Lagerringstrasse was planned at an interval of 18 meters (60 feet) . The smaller back alleys along the rows of tents were called Viae vicinariae and were between 10 and 20 feet (around three to six meters) wide.

Stand camps, garrisons

The republican marching camp formed the structural basis for the permanent garrisons that only emerged in the early imperial era . This standardized conception, which varies depending on the size of the fortifications, was retained until late antiquity . At the latest under Emperor Diocletian (284–305 AD), completely new forms of architecture were introduced. Fortress-like bases with changing floor plans replaced the previous standardized barracks.

Early to Middle Imperial Era

Stand bearings were built for a more or less long-term use. In many cases it was enough for the Roman military to design the facilities as pure wood and earth forts with earth walls and to renew them from the ground up at intervals of 20 to 30 years. At a certain point in time, only important parts of a structure in these garrisons, such as the flag shrine in the staff building (Principia) or heated rooms at the commandant's house, were built in stone, while the other structures were made of wood. Some camps built using the wood-earth technique, such as the small fort Burlafingen on the Danube, have not received any permanent internal structures despite a useful life of around ten years. Mostly because of unforeseeable circumstances, many investments were made in the construction of a stone fort, whereby there were all possible gradations of the stone expansion depending on the degree of importance. As a rule, at least the fencing has been fixed accordingly in these systems. Especially in the Roman border regions it can be observed that the first wood-earth camps were often largely expanded using stone technology. While the crew barracks of the auxiliary troops garrisons were mostly built as half-timbered buildings in such fortifications, the permanent legionary locations were mostly built entirely in stone. In many cases, particular emphasis was placed on impressive gate structures and representative staff buildings. Many of the halls erected in the Principia were in no way inferior in terms of their dimensions and the spans of the ceilings of great urban architecture.

Late antiquity

In the course of the 3rd century numerous changes took place in the Roman Empire, which also affected the military. Because of the increased pressure that Rome was exposed to in the north and east (cf. Sassanids ), the border defense was reformed. Many of the older limites were abandoned and more easily defended borders, especially rivers, were withdrawn. In late antiquity, a new type of fort arose that no longer had much in common with those of the early and middle imperial period. The transition can be clearly seen at the forts along the Rhine, Danube and the Saxon coast . The new military bases were much more fortified than the castles of the first two centuries AD and often already resembled medieval castles . Endre Tóth sees the origin of the early U-shaped and fan-shaped towers of the 3rd century in the Balkan provinces of Moesia and Scythia. The technical discussion on the development of individual structures in late antique castles has not yet been concluded. This type of military architecture remained common until the 6th century. The emperors Diocletian , Valentinian I and Justinian I in particular carried out large fortress building programs .

The reduction in the size of the fort areas, which can often be observed, or the adaptation of the buildings to new troop structures and often fewer units, resulted in the demolition and conversion of the previous interior development in the late period. The flag sanctuary of the Middle Imperial Principia of the Pannonian fort Százhalombatta-Dunafüred (Matrica) was converted into a rubbish pit in the post-Valentine period.

Peculiarities of late antique military buildings

- Conversions

Conversions to small forts : Many border forts from the Principate's time were greatly reduced in size during late antiquity. On the Danube Castle Abusina in Bavaria one is burgus particularly well preserved.

Conversions : The Middle Imperial fort Donaukastell Intercisa received fan- and U-shaped towers in late antiquity, gates were walled up and the praetorium expanded like a palace.

- New building schemes

Further developments : The rear Limes fort Nag el-Hagar, built in Egypt around 300 AD, with its late antique palace complex and an unusual principia with an octagonal flag sanctuary

Castle-like fortresses : The large Danube fort Castra ad Herculem follows the natural structure of the rock on which it stands. Late 3rd or early 4th century; Interior development from the late 4th century

... the same new idea was followed by the small Bürgle near Gundremmingen on the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , which was founded at the end of the 3rd century and presented itself as a castle-like fortress

Quadriburgi : The Danube fort Visegrád-Gizellamajor, built between 337 and 361, is a quadriburgus with four fan towers in Hungary, has the same design as ...

... the small fort Tetrapyrgium excavated in Syria , which was built in 324 at the earliest

The small tripolitan fort Gasr Bularkan shows another typical building type of the Quadriburgus , which is dated shortly after 275/280

- Burgi

Mighty tower-like fortifications, often in tight chains, were introduced to secure borders and served as a base for small units. In this construction, these burgi date from the reign of Emperor Valentinian I (364–375)

- Ländeburgi

Types of smaller standing storage

The auxiliary forts are also found among the smaller types of camps. This means that there were auxiliary troops in the occupation. Principia , commandant's house and crew quarters were mostly found in the same location at Alen, cohort and numerus forts as at the legionary camp.

Alenkastelle

The riding troops of the Alen consisted either as ala quingenaria of almost 500 or as ala milliaria (double Ala) of up to 1000 men. With the space required for the horses, storage sizes of up to 60,000 m² were achieved. Typical for mounted units were barracks rooms (occupancy six or eight men) with access to the immediately adjoining horse stables.

Cohort fort

Roman auxiliary units were basically organized in three basic types: the infantry cohort ( cohors peditata ), the cavalry squadrons ( ala ) and the cohors equitata , which is often translated as "partially mounted". Each of these three types occurs as a standard unit with a nominal 500 men (what the Romans called quingenaria ) or as an enlarged unit with a nominal 1000 men ( milliaria ). The terms quingenaria and milliaria were probably used only as approximations and not as exact units of size. The size and internal structure of these units remains a mystery, but some were obviously large enough to be spread out over multiple locations. Archaeologists often assume that a single centuria and officers or two turmae and their officers occupied a single barrack block. A typical cohort fort can be found in Hesselbach (Odenwaldkreis) .

With a size of 6000 to 8000 m², about 150 men of the reconnaissance units ( Numbers ) were accommodated in numerus castles .

Small fort

Small forts were often only 300 m² in size. The manning ranged between 12 and 80 men. In the original form there was only a gate and a moat. The interior was either arranged in a U-shape, or with two opposite gates, the crew barracks were to the left and right of the street. Often it was not military reasons for the construction of such small forts, but a control function of the movement of people and goods at entry points into the Limes area.

Burgi

Burgus ( lat. , Pl. Burgi ) or turris is a Germanic name, borrowed from the Romans, for tower-like smaller forts from late antiquity , some of which were also provided with an outer structure and surrounding ditches. Commodus built watchtowers along the borders to help guard them. Inscriptions record the construction and the purpose of the towers to monitor bands of robbers who regularly invaded the northern provinces.

Facilities in a fort

Reinforcement made of wood and earth structures

The Romans protected themselves in the marshes with ramparts, ditches, stakes and wicker fences. The wooden pila muralia (wall spears), which in addition to their function as double-sided pointed piles could also have been used as road barriers, were found in very good condition at some Roman garrison types from the imperial era, such as the east fort Welzheim . At what point in time and how extensively the Roman army made use of these stakes is unknown. The Pila found so far have been made very differently despite a basic standardization of their appearance. The heights and the diameter varied considerably. It is assumed that the piles found were driven with the tip of one side into the crests of the marching camps.

In the 1st century AD in particular, many permanent military sites were not always protected by stone walls. Due to the different conditions found on site, the Romans defended these camps with different techniques, including Lilia . The system of two opposing stone wall shells, the space between which was subsequently filled with pounded earth, was used as a stable and safe construction. The Roman military adapted this basic concept to the respective circumstances. So turf bricks (Caespites) were cut out and used instead of stone walls; elsewhere, different wooden constructions took on this function. Mud walls and vertical turf walls with stone filling were also built, as at Hod Hill Fort in southern England . One of the many possibilities was dry stone wall shells filled with earth, such as those found at Fort Hesselbach (construction phase B) .

All these buildings had parapets with battlements made of wooden beams or wattle, the defenders stood on the wall. Defense towers or defense platforms were also installed. In order to ensure that these wood-earth structures stood securely, a stable and dry surface had to be provided. Therefore beds made of brushwood, twigs, wooden beams and stones were used. The walls themselves could also be stiffened with wooden inlays such as beams, brushwood and branches. The stairs to these facilities could be ramps or stairs.

The reconstruction of such a fort is currently being built in Pohl .

Gates (portae)

As a building inscription on one of the gates of the Tripolitan Fort Gholaia from the year 222 testifies, the soldiers showed great willingness to work on the construction work. The text from Gholaia describes the meaning of the towering gates as follows: "As the precious stone is set in gold, the gate adorns the camp."

No gates were erected in the marshals. The titulum (protective ditch) or the outer and inner clavicle (a kind of parapet with a small ditch) in front of the entrances was intended as a barrier to approach. Gate buildings, of which the Roman camp usually had one on each of its two flanks and front sides, only became common with the more solid and solid forts. These four entrances had their own names that were repeated at each garrison. The gate facing the enemy was called Porta praetoria , the rear entrance was called Porta decumana and the two side gates were called Porta principalis sinistra and Porta principalis dextra . The gate buildings of the early and middle imperial period were similar in plan. With the emergence of new gate and fort shapes in late antiquity, which could also have round or polygonal towers, the designs of the garrisons and wooden military sites will have deviated significantly more from one another due to construction. At many locations from the Middle Imperial Period, it was found that the Porta decumana was designed as a rear outlet or inlet significantly smaller than the three other gateways.

In their simplest construction, which can occur in wooden and stone forts, no tower of any kind was used. Small forts in particular show this type of construction more often, but they have been observed several times, especially with the wooden auxiliary garrisons, although there are variants. Research is difficult to determine whether one or the other gate had a tower or not. If so, this tower was directly above the entrance. Archaeologically verifiable, however, are mostly only the post holes, which allow little knowledge about the former superstructure. The same applies to the stone castles. Here, too, the foundations rarely provide information about the rising masonry.

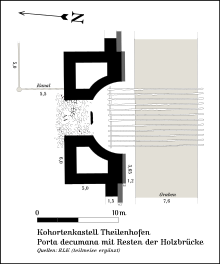

Even with the wooden and stone gates with square or rectangular, laterally flanking towers, several types can be distinguished. There were gates in which the side towers were flush with the wall, in others the towers protruded more or less far from the fort wall. The latter type of construction can already be observed in the Flavian period (69–96 AD), but initially remains rarer and is initially more of an element that emphasizes the architecture. It was only after the middle of the 2nd century that these gate tower structures were fastened more frequently and more massive. Its prominent feature can already be used under Emperor Commodus (180 to 192 AD) to add loopholes on the sides, as was the case at Niederbieber Castle. Another, seldom seen gate variant from the middle imperial period is the U-shaped gate, as it was also used on city gates. The best-known military example dates from around 170 AD and was built in monumental form as the Porta Praetoria of the Legion Fort Castra Regina (Regensburg). This gate was possibly a model for replicas at other Rhaetian auxiliary locations, such as the Schirenhof and Weissenburg castles. A concave curvature such as the one excavated at the Theilenhofen cohort fort is even rarer. This building belongs to the Antonine era. Other well-known examples can be found at the legion camp in Carnuntum, Austria, and at the Lambaesis legion camp in Algeria.

One- or two-lane entrances were possible for all variants. The one or two-story battlement was located above the vaulted driveway. This could be roofed, with windows or open, with parapets and battlements. The towers, which were mostly at least two-story, were also roofed over according to the weather or equipped with a crenellated wreath. The roofing could be done with clay tiles and slate sheets. This cannot be proven, but wood shingles or thatched roofs are quite conceivable for lighter towers, for example . But even in the case of permanent military installations, brick or stone shingles are often missing, so that an alternative, perishable roof covering can also be expected here. Based on the still upright castle gates or drawings that early researchers made of gates that were still better preserved at the time, as well as on the basis of findings that were collected throughout the former Roman Empire, a relatively clear picture of the basic gate design can be obtained today, albeit with many details the details of most garrison sites will forever remain unknown. The Romans used the arch very often when building window openings. It can be proven in a number of gate structures through the discovery of wedge stones. An architectural peculiarity of the fortifications on the Main and the Odenwald Limes was the arched accentuation of the wall openings by stone window or lintel lunettes. The corresponding window or the corresponding door in this region had a horizontal end at their apex over which a semicircular, ornate lunette was walled in. Such lunettes were also dug up in the rubble of the camp gates at Birdoswald Castle in the north of England. Among the rich architectural material, which has been discovered many times during archaeological investigations, there are very often cornices that subdivide the defensive wall and gates horizontally, as well as partly decorated window and door lintels that reveal the design features of different garrison sites. At the legionary camp Bou Njem in today's Libya, the top wedge stone on the single-lane north entrance was decorated with a Roman eagle. An important element, which was not only found on the main access roads, was the often monumental building inscription which at least indicated under which emperor and by which troop the construction had been carried out. The troop commander, the governor and sometimes even the consuls in office were often named, making it possible to date the inscription to the exact year. This gives research the time to erect the stone structure in question. These inscriptions were usually embedded in the center above the arches of the driveway. The gate structures like the entire defensive walls of a fort were at least very often plastered white. In order to simulate a particularly impressive appearance, regular, larger ashlar stones were imitated on this plaster by scratching the plaster. These incisions were then redrawn with red paint. At the Ellingen fort, only a simple white plaster could be found, although the excavators left it open as to whether there was a red joint line. The inscriptions were covered with bright white stucco, with the recessed letters and numbers also being filled in with red. In some forts on the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes, as well as along the Danube border, gold-plated metal letters torn from the composite were mostly found, which are often associated with the visit of Emperor Caracalla to the imperial border, which took place in 213 AD. It is therefore known that there were honorary and architectural inscriptions in this form. The entrances to the stone towers were always at ground level and could be on the back of the tower or on its flank under the gate passage. From there, the soldiers not only got to the upper floors, because the ground floor also served as a lounge for the gate guard.

At the end of the 3rd century, at the beginning of late antiquity, completely new fortress-technical concepts for the fixed Roman military sites can be proven. Even at that time, the new standards were being implemented even in distant provinces, as the round gate towers of the southern English forts on the Saxon coast show.

Staff building (Principia)

The Principia (plural word) were the administrative and religious center at almost every fortified military site. From the middle of the 1st century BC Until the beginning of late antiquity, its structure followed a standardized floor plan. The importance of this building complex is underlined by its location at the intersection of the most important street axes of a fort. In the literature, the word middle building is therefore also used for this structure. The appearance of this central building has undergone a multitude of changes over the centuries.

Commandant's residence (Praetorium)

On campaigns, the commander of a Roman army was housed in a tent that was set up in the middle of the march. This tent was called the Praetorium . In the more permanent camps of the late republic, as they became known especially through the conquests in Spain, the commander's house developed from this, which at that time was still associated with the Principia . It is possible that the final separation of these two building units did not take place until the early Imperial Era. In camps, however, this unity was still preserved, as the findings of camp B of the enclosure of Masada show (72/73 AD). The layout of the praetorium during the imperial period was mostly based on the architecture of traditional Italian residential buildings in the style of peristyle houses. This architecture was already at home in urban housing in the eastern Mediterranean before the Roman era. In most cases, four wings offering plenty of space were grouped around an elongated, rectangular to square portico courtyard. This scheme was not only implemented in the commandant's houses built in stone, but can also be found in the wood and earth forts. In most auxiliary garrisons of the early and middle Imperial Era, the praetorium was in the Latera praetorii , the median of a fort near the staff building. Peristyle houses for the tribunes were already known to the Augustan legionary camps, but they can be found at the locations of the auxiliaries for the first time during the reign of Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD), for example in the forts Hofheim am Taunus and Oberstimm . Many late antique military sites did not have a special dwelling for the commanding officer, or rather it cannot be clearly identified due to the individual structures of these facilities. But the peristyle house in the castles lasted until the 4th century. In the Romanian fort Dinogetia, structural structures from the late 3rd or early 4th century have been preserved, which correspond to an early and mid-imperial commandant's villa. Something similar was found at Caernarfon Castle , Wales.

It is unknown how many people the commander's household comprised in addition to the servants. If under Augustus even high officers were not allowed to take their wives with them into the garrisons, this ban was later relaxed and lifted for the commanders. Many women may not have followed their husbands directly to the forts in the border regions, others may have lived in larger settlements a little further away or in better developed camp villages that met a higher standard. However, testimonies from families are very rare. The young wife of Publius Crepereius Verecundianus, a cohort prefect of the Pfünz fort near the Limes, died in the settlement of Nassenfels a little further south. In Birdoswald Castle in Northern England on Hadrian's Wall, a tombstone from the beginning of the 3rd century provides information about the presence of the family of the Tribune Aurelius Iulianus at the garrison site. It was built for his one-year-old son. The shoes of women and children, which can occasionally be found in garbage pits and abandoned wells of the forts, for example in the east fort in Welzheim, are no evidence of officer families in the forts. They only bear witness to life in the camp villages.

In many cases, the more privately designed praetorium does not exactly adhere to the grid-like specifications of a fortress from the middle imperial period. Some had more irregular floor plans with opulent bathrooms, as in the Scottish Mumrills fort on Antoninuswall , while others attempted an arcade front facing the street in a straight line of architectural rigor as in Oberstimm. Remnants of painted wall plaster, stone screed floors ( Opus signinum ) and broken window glass, as well as underfloor and wall heating, testify to the comfort that the commanders of the auxiliary troop fort also afforded . In the northern English fort Bewcastle on Hadrian's Wall, the craftsmen had even processed profiled marble slabs. Some praetories had extensions with farm yards that included stables, barns and sheds, others bordered gardens. The earliest example of a commandant's house with an extension is also the Hofheim fort from the middle of the 1st century AD.

Granary (Horreum)

Grain stores could be uncovered at most of the larger permanent fort sites of the imperial era . Even in late antiquity, these buildings can still be traced back to archeology based on their typical appearance. The Horrea stood mostly on the median (Latera praetorii) of a fort, in some cases also in the adjacent area of the Retentura , the rear camp zone, on the Via quintana . A characteristic of the granary buildings is their frequent proximity to the principia ; In some military locations of the 2nd century AD, structural densities can be observed in this context, in which the horreum and the staff building almost merge into one unit. Since in late antiquity, due to the structural individualization of the garrisons, there was often no longer any unequivocal evidence of the commandant's offices or administrative tracts, so no clear statement can be made on this point. Some camps have only one granary, others two or more. In supply camps in particular, almost the entire fort area of Horrea can be built on and only a small section can be left free for accommodation and administration, as in the north English camp South Shields, which was expanded under Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 AD). In some camps double horrea occur, such as in the Niederbieber fort. In the Pfünzer garrison, one of the granaries was even located in front of the gates of the camp.

There are two basic types of horrea . The most famous and frequently used type of oblong-rectangular stone building with mostly strong wall templates and wooden floors, which were supported by stone or wooden pillars or wall girders above the floor level, as well as the so-called courtyard type, in which the rooms are grouped around a rectangular inner courtyard, such as this one at the Aalen fort. Wooden granaries were also known. As was shown in the better preserved Horrea , the entrance to these buildings , which is often on the Via principalis , was preceded by a wooden loading ramp, which was obviously protected from rain by the building's protruding roof. The roof was supported by wooden posts or by stone pillars in the shape of a portico, as demonstrated at Corbridge Fort in Northumberland. The stone foundations of the granary have been preserved there in an excellent way. This made it possible to establish that there were narrow, elongated high ventilation openings at regular intervals, which were again divided in the middle by a simple stone pillar. Instead, there could be wooden and iron grilles on these underfloor ventilation. The purpose of ventilating the stored grain was to keep the bulk material as dry as possible so that it could be stored for a longer period of time. The elevated position above the ground also protects against pests. The grain was poured openly into the Horrea, which is why there was a particularly high pressure on the walls, which was absorbed by the wall templates.

Latrines

In order to create a healthy environment at the garrison types, among other things, the Roman military tried to implement the sanitary standards known from Italy in the most remote parts of the empire. Up into the 20th century, epidemics also led to devastating population losses in industrialized countries . Poor hygiene has weakened entire armies around the world, diseases have decimated peoples. These dangers had to be minimized in order to keep the Roman soldiers always effective. The disposal of the faeces was therefore an important aspect . The separate handling of excrement was particularly important at a time when not insignificant parts of the population suffered from intestinal parasites due to a lack of medication. Attempts were made at a number of fort sites to use sewer systems to set up flushing water toilets that minimized or made it unnecessary to clear the toilets manually.

While the officers mostly had their own latrines, the troops had to be content with crew toilets. Evidence of these facilities has not always been successful in the past, but research nevertheless assumes a relatively standardized toilet culture at the fort sites, even if in the short-term camps but also at the military posts fortified in stone, often only or at least partially with simple toilets in the form the “thunder bar” is to be reckoned as it is known to the present day. For this purpose, the Roman military built an elongated pit into the ground and placed a simple wooden structure with seating and a roof over it. After the pit was filled, a new one had to be dug and the old one thrown. This type of latrine was preferably located close behind the defenses on Lagerringstrasse (Via sagularis) . It was proven , for example, at the Künzing Fort on the basis of the pits filled with pits. The cuttings examined there were 1.4 meters deep, 14 meters long and two meters wide. The volume of the room shows that this "thunder bar" has remained in operation for many years. Post holes indicate the wooden superstructure. It could be established that the crew of the fort must have been contaminated with the relatively harmless whipworm Trichuris trichiura, despite the general hygiene measures . Only in larger quantities does this animal, which is still common today, lead to diarrhea and bleeding, and in extremely rare cases even to intestinal obstruction . In the head buildings of the crew barracks, which were inhabited by the centurions and possibly other officers, was their private toilet. The disposal of these facilities was often done through wood-paneled channels. In short-term wood-earth stores, these often ended up in septic tanks; better-developed toilets had a sewage system flushed with sewage. This could also be connected to the communal latrines. The prerequisite for a functional flushing was that the fort had a certain slope, whereby the crew toilet, which needed the most water, had to be at the lowest point. In the southern Dutch fort Alphen aan den Rijn ( Albaniana ) , an early half-timbered barrack from the middle of the 1st century was excavated, in which the centurion's rectangular, 0.9 × 2.5 meter large toilet room with channeled toilet had been preserved. Similar latrines were also in the Castle Valkenburg ( Praetorium Agrippinae ) excavated. The centurion toilet from Alphen aan den Rijn contained the remains of the corn worm, which must have partially infected the grain of the unit. It was ground up during the grinding process and so entered the food chain. In addition, thousands of eggs of the whipworm, the roundworm and, to a much lesser extent, the tapeworm were found . In the early imperial latrine Swiss castle Zurzach which was additionally beef tapeworm found. On the other hand, the excavators only encountered the whipworm in Fort Ellingen .

The crews of the northern English fort Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall owned a particularly elaborate flush toilet in the 2nd century AD Water tank with the help of which flushing was ensured. The process water then flowed into the moat below. In front of the seats there was a shallow channel embedded in the stone tiles on the floor, which carried fresh water. Bending down, the sponges that were used in place of toilet paper could be dipped in and cleaned. The two hand wash basins in the middle of the latrine between the opposite rows of seats were originally fed by a pressurized water pipe. Similar toilet facilities were found in the Saalburg fort and in the Großkrotzenburg am Main fort . Such comfortable sanitary facilities, as in the Roman army, probably had no army again before the 20th century. The roster of a legionary division in Egypt from October 2, 87 AD shows that the soldier M. Longinus A ... was assigned to clean the toilet.

Fort baths

The facilities also included bathhouses and thermal baths with hypocaust heating .

Accommodations

The organizational structure of the Legion was retained in the accommodations. Each group ( contubernium , tent community) had a bedroom with a fireplace and an anteroom for the equipment and any non-free staff. There was also a portico in front of these two rooms. The ten rooms of the Centurie were arranged in a row. At the head end there was the accommodation of the centurion , the optios and the other ranks . The space ratio of simple soldiers to centurions was about 1: 10–1: 12.

More buildings

In addition to the buildings above, a stand storage facility could also include stables , a hospital ( valetudinarium ) and workshops . In addition to the metal workshops, there were sometimes regular building yards in or around the warehouse, as the Legion was also responsible for many construction tasks in their area. Many bricks , even outside of military buildings, have legion stamps.

Warehouse environment

Settlements

A settlement ( vicus ) of civilian escort personnel of the Legion quickly formed around a camp, which ranged from workshops, traders, farms to the partners and families of the officially unmarried legionaries.

This settlement ( canabae ) , together with the actual camp, formed the nucleus for the Romanization of the respective province, whereby the Romanization in the immediate vicinity of the border, due to the larger number of military camps, was usually stronger or faster than in the hinterland. In some cases, for example with the Batavern on the Lower Rhine, a separate military caste developed , which supplemented the respective legion or the entire army for several centuries.

Burial places

The cemetery was also located outside the camp. One of the largest burial sites of this kind was discovered at the Gelduba fort .

Development into cities

Outside almost all fortresses and castles there were civil settlements known as canabae in the case of fortresses and vici in the case of castles. Significant cities often emerged from Roman forts and their vici , although the Romans already used some of the older settlements. The army was able to protect the civilian settlements by keeping the borders and keeping the peace internally through police work. However, from the third century onwards, the pressure to fasten it increased. The complete stagnation of growth and the lack of new construction or expansion of cities from the third century onwards was seen as one of the most compelling evidence of the empire's decline. Instead, there was a boom in the construction of the defensive walls, which undoubtedly required all the attention, effort and expense.

Those cities in which there was a direct imperial interest, or better yet an extended imperial presence with the troops of the field armies housed in the cities, were supported and survived the crisis of the third century. For cities that were not occupied by the emperor and the field armies or were not on important routes, the responsibility for building defenses fell on the inhabitants. Many modern cities emerged in post-Roman times on the periphery of their ancient predecessors and used them as a cheap supplier of building materials.

- Examples

See also

literature

General

- Marcus Junkelmann : The Legions of Augustus . 7th, revised edition. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-0886-8 . (= Cultural history of the ancient world, 33)

- Harald von Petrikovits : The interior structures of Roman legion camps during the principate's time . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1975, ISBN 3-531-09056-9 . (= Treatises of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Volume 56)

- Harald von Petrikovits: The special buildings of Roman legion camps. In: Harald von Petrikovits: Contributions to Roman History and Archeology, Volume 1 . Rheinland-Verlag, 1976, ISBN 3-7927-0288-6 .

- Norbert Hanel : Military Camps, canabae and vici. The archaeological evidence. In: Paul Erdkamp (Ed.): The Companion to the Roman Army. Blackwell, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4443-3921-5 .

- Patricia Southern : The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476, 2nd edition. Amberley, The Hill, 2014, ISBN 978-1-4456-2089-3 .

Germany

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . 4th edition. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 , p. 308 ff.

- Jörg Faßbinder : New results of the geophysical prospection at the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . 4th specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 27./28. February 2007 in Osterburken. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 3), pp. 155–171, especially pp. 163–167.

- Thomas Fischer , Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 .

- Günter Ulbert , Thomas Fischer: The Limes in Bavaria . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0351-2 , p. 94 ff.

- Dieter Planck , Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd completely revised edition, Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 .

- Gerda von Bülow : The Limes on the lower Danube from Diocletian to Heraklios. Lectures at the International Conference, Svištov, Bulgaria (September 1-5, 1998) . Nous, Sofia 1999, ISBN 954-90387-2-6 .

Great Britain

- Richard J. Brewer: Roman fortresses and their legions . Society of Antiquaries, London 2000, ISBN 978-0-85431-274-0 .

- J. Collingwood Bruce's: Handbook to the Roman Wall. Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, 2006, ISBN 0-901082-65-1 .

- Anne Johnson , arr. von Dietwulf Baatz: Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD in Britain and in the Germanic provinces of the Roman Empire. 3rd edition, Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , (Cultural History of the Ancient World, 37)

- David JA Taylor: The forts on Hadrian's Wall: a comparative analysis of the form and construction of some buildings. Archaeopress, 2000, ISBN 1-84171-076-8 .

- Henner von Hesberg : Design principles of Roman military architecture. In: Henner von Hesberg (Hrsg.): The military as a cultural carrier in Roman times. Archaeological Institute of the University of Cologne, Cologne 1999, pp. 87–115 ( writings of the Archaeological Institute of the University of Cologne ).

Hungary

- Sándor Soproni : The last decades of the Pannonian Limes . CH Beck, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-406-30453-2 .

- Sándor Soproni: The late Roman Limes between Esztergom and Szentendre. Akademiai Kiado, Budapest 1978, ISBN 963-05-1307-2 .

- Zsolt Visy : The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-8062-0488-8 .

Individual forts

Germany

- Dietwulf Baatz: Fort Hesselbach and other research on the Odenwald Limes. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-7861-1059-X (Limes research, volume 12)

- Dietwulf Baatz: Roman wall paintings from the Limes fort Echzell, Kr. Büdingen (Hessen). Preliminary report. Publisher Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1968.

- Tilmann Bechert : Germania inferior. A province on the northern border of the Roman Empire . Verlag Pillipp von Zabern, Mainz 2007, ISBN 3-8053-2400-6 .

- Bernhard Beckmann: Recent studies on the Roman Limes fort Miltenberg old town . Verlag Michael Lassleben, Kallmünz 2004, ISBN 3-7847-5085-0 .

- Hermann Heinrich Büsing : Roman military architecture in Mainz . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1982, ISBN 3-8053-0513-3 .

- Thomas Fischer : forts Ruffenhofen, Dambach, Unterschwaningen, Gnotzheim, Gunzenhausen, Theilenhofen, Böhming, Pfünz, Eining . In: Jochen Garbsch (Ed.): The Roman Limes in Bavaria. 100 years of Limes research in Bavaria . Exhibition catalogs of the Prehistoric State Collection 22, 1992, 37 ff.

- Eveline Grönke: The Roman Alenkastell Biricianae in Weißenburg in Bavaria. The excavations from 1890 to 1990 . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2318-2 .

- Norbert Hanel : “The military camps of Vetera I and their camp settlements.” In: Martin Müller, Hans-Joachim Schalles, Norbert Zieling (ed.): “Colonia Ulpia Traiana. Xanten and its environs in Roman times “Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3953-7 , 93-107.

- Martin Kemkes and Markus Scholz : The Roman fort Aalen. Research and reconstruction of the largest equestrian fort on the UNESCO World Heritage Site Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2057-3 .

- Klaus Kortüm : The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . 4th specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 27./28. February 2007 in Osterburken. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 3), pp. 123-139.

- Michael Mackensen , Angela von den Driesch : Early imperial small fort near Nersingen and Burlafingen on the upper Danube . CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-31749-9 .

- Dieter Planck: Welzheim. Roman forts and civil settlement . In: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. 3. Edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 611 ff.

- Dieter Planck: Investigations in the west fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg . Konrad Theiss publishing house. Stuttgart 1989. pp. 126-127.

- Hans Schönberger : Kastell Künzing-Quintana . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1975, ISBN 3-7861-2225-3 .

- Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Aalen Limes Fort . In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes, Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , (= 3rd specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission February 17/18, 2005 in Weißenburg i. Bay.), Pp. 107–121.

- Andreas Thiel: The defense towers of the west fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg. Volume 20. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1999. pp. 94-96.

- Carol van Driel-Murray, Hans-Heinz Hartmann: The east fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis . Theiss, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1077-2 .

- Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg: Electro- and geomagnetic prospecting of the Welzheimer Ostkastell, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg. Konrad Theiss Verlag 1993. pp. 135-140.

- Siegmar von Schnurbein : The Roman military installations at Haltern. Soil antiquities of Westphalia 14, Münster 1974

- Friedrich Winkelmann : The fort Pfuenz. In: Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (ed.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roemerreiches B VII No. 73 (1901).

- Werner Zanier , Angela von den Driesch , Corinna Liesau: The Roman fort Ellingen . Verlag Phillipp von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1264-4 .

Hungary

- Gábor Finály : Castra ad Herculem. In: Archaeológiai Értesítő. 27, 1907, pp. 45-47 (in Hungarian).

- Endre Tóth : The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia . In Archaeologiai Értesitő 134 . Budapest 2009.

Romania

- Alexandru Barnea: La forteresse de Dinogetia à la lumière des dernieres fouilles archéologiques. In: Studies on the military borders of Rome III. 13th International Limes Congress. Aalen 1983. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0776-3 , pp. 447-450.

Spain

- Adolf Schulten: Numantia: The results of the excavations 1905-1912 . Bruckmann publishing house. 27

Great Britain

- John N. Dore, John P. Gillam: The Roman fort at South Shields, Excavations 1875-1975 . Society of. Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne Monograph 1, 1979.

- Peter Howard: Birdoswald Fort on Hadrian's Wall: a history and short guide . Frank Graham 1976, ISBN 0-85983-083-7 .

- Edward John Phillips: Corbridge: Hadrian's Wall east of the North Tyne. Oxford University Press 1977, ISBN 0-19-725954-5 .

Special topics

- Tilmann Bechert: Roman camp gates and their building inscriptions. A contribution to the development and dating of camp gate floor plans from Claudius to Severus Alexander. In: Bonner Jahrbücher 171, p. 201 ff. Habelt, Bonn 1971.

- Rudolf Fellmann : Principia - staff building . Limes Museum, Aalen 1983, (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany, 31)

Web links

- Saalburg Museum

- A virtual tour through the Feldberg fort

- Castrum Novaesium - The Roman military camp near Neuss

- Klaus Gerteis describes the diorama of the Roman fort in Neuss

- Antikefan - Roman military buildings and systems (private site)

Remarks

- ↑ Histories 3.84

- ↑ Simon James: Rome and the Sword. How warriors and weapons shaped Roman history . WBG, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-534-25598-6 , p. 161.

- ^ De munitionibus castrorum .

- ↑ Vegetius, Epitoma rei militaris .

- ↑ Polybios 6, 26–42 ( English translation ).

- ^ Polybios: History . Ed .: Hans Drexler. tape 1-2 . Old World Library, Zurich 1961.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Roman castles , Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 13-21.

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2014, pp. 318-319 .

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2014, pp. 320 .

- ↑ Duncan B. Campbell: Roman Legionary Fortresses 27 BC - AD 378 . In: Fortress . 3. Edition. tape 43 . Osprey Publishing Ltd., Oxford 2008, p. 33-54 .

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley Publishing, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2016, pp. 325-329 .

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 38-40.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Duncan B. Campbell: Roman Legionary Fortresses 27 BC - AD 378 . In: Fortress . 3. Edition. tape 43 . Osprey Ltd., Oxford 2006, p. 57 .

- ↑ Endre Tóth: The late Roman military architecture in Transdanubia. In Archaeologiai Értesitő 134 . Budapest 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Rob Collins, Meike Weber: Late Roman Military Architecture: An Introduction . In: Rob Collins, Matt Symonds, Meike Weber (Eds.): Roman Military Architecture on the Frontiers. Armies and Their Architecture in Late Antiquity . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2015, pp. 1-5 .

- ^ Péter Kovács : The late Roman Army. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 33.

- ↑ Slow motion / Duisburg excavations / Asciburgium , Museumsverlag Duisburg, 2013 edition, page 88 ff .: "the Roman military"

- ↑ Duncan B. Campbell: Roman Auxiliary Forts 27 BC - AD 378 . In: Fortress . tape 83 . Osprey Ltd., Oxford 2009, p. 24-32 .

- ↑ Tacitus , Agricola 14, 1; 20, 3; Babylonian Talmud , Mo'eds Katan 28b

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2014, pp. 195-196 .

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd completely revised edition. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 . Pp. 94–96, fig.

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Limes Research XII. Studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-7861-1059-X , p. 14.

- ^ Dietwulf Baatz: Buildings and catapults of the Roman army. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-515-06566-0 , p. 62.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 101-103.

- ↑ AE 1995, 01671 .

- ↑ Christof Flügel , Klaus Mühl, Jürgen Obmann and Ricarda Schmidt: “How the precious stone is set in gold, the gate adorns the warehouse.” On the reception of Roman fort gates in the Middle Imperial period . In: Report of the Bayerische Bodendenkmalpflege 56, 2015, pp. 395–407; here: p. 395.

- ^ Dieter Planck: Restoration and reconstruction of Roman buildings in Baden-Württemberg. In: Günter Ulbert, Gerhard Weber (ed.): Conserved history? Ancient buildings and their preservation . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0 , pp. 149-150.

- ^ A b Dietwulf Baatz: The Roman Limes: archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2 , p. 36.

- ^ Marion Mattern: Roman stone monuments from Hesse south of the Main and from the Bavarian part of the Main Limes . Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani. Germany vol. 2,13, p. 31, cat-no. 148.

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Limes Research XII. Studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-7861-1059-X , p. 20.

- ↑ Werner Zanier, Angela von den Driesch, Corinna Liesau: The Roman fort Ellingen. Verlag Phillipp von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1264-4 , p. 23.

- ↑ Barbara horse shepherd : The ceramics of the castle Holzhausen. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-7861-1070-0 , p. 18.

- ^ R. Fellmann: Principia . In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 23 . Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017535-5 , p. 159.

- ^ Hans Schönberger: Fort Oberstimm . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-7861-1168-5 , pp. 80ff.

- ↑ Suetonius, August 24.

- ^ AE 1913, 131 .

- ^ Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB) 1, 1919 = CIL 7, 289 .

- ^ A b Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Roman forts . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 235.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Panis militaris - The food of the Roman soldier or the raw material of power . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2332-8 , p. 26.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Panis militaris - The food of the Roman soldier or the raw material of power . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2332-8 , p. 27.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Panis militaris - The food of the Roman soldier or the raw material of power . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2332-8 , p. 28.

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2014, pp. 483-485 .

- ↑ Patricia Southern: The Roman Army. A History 753 BC - AD 476 . 2nd Edition. Amberley, The Hill, Stroud, Gloucestershire 2014, pp. 485 .