Direct democracy in Germany

Elements of direct democracy were first introduced in Germany in the Weimar Republic . Only three referendums took place at the national level. Only the one on the expropriation of the princes and the plebiscite against the Young Plan made it to the referendum , neither of which was able to achieve the approval of the majority of voters required for constitutional changes.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, direct democratic procedures are weakly developed at the federal level . Article 20 (2) of the Basic Law emphasizes popular sovereignty and states: “All state authority comes from the people. It is exercised by the people in elections and votes [...]. ”While“ elections ”always refer to personnel decisions,“ votes ”represent direct decisions by the state people on factual issues. Nevertheless, the Basic Law only provides for referendums in two very narrow cases: On the one hand, when the Basic Law is replaced by a new constitution, and on the other hand, in the case of a restructuring of the federal territory , in which only citizens entitled to vote in the affected areas are entitled to vote. Apart from these two exceptions, federal politics is designed as a purely representative system.

Direct democratic instruments are much more firmly anchored at the state level. When the German federal states were founded after 1945, eight state constitutions were adopted by referendum . All state constitutions passed up to 1950 contained direct democratic procedures, eight of which included people's legislation . The later constitutions renounced it. The hurdles for people's legislation were raised so high that, apart from a few votes on territorial changes, a referendum was only held in Bavaria in 1968. Outside of Bavaria there was not a single one until 1997. In the first decades of the Federal Republic of Germany, only mandatory constitutional referenda played a role in Bavaria and Hesse. From 1989/90 a new dynamic began in the development of direct democracy at the state level. By 1996, the people's legislation was incorporated into all state constitutions. The legislative procedure for initiatives from the people at the state level is usually designed as a three-stage popular legislation , beginning with a popular initiative or a petition for a referendum , followed by a referendum and concluded with a referendum. The legal regulations vary greatly; the required quorums as well as deadlines and subject exclusions are of decisive importance . In Bavaria and, more recently, in Berlin and Hamburg , referendums are therefore held in significant numbers, while the hurdles to do so in other countries are considered to be almost insurmountable. Referendums on simple laws that the state government or parliament can set up in some countries hardly play a role .

Also since the early 1990s, citizens' petitions and referendums have prevailed at the municipal level , which until 1990 only existed in Baden-Württemberg. At the same time, the direct election of mayors and district administrators prevailed. However, elections of representatives are usually not counted as part of the direct democratic procedure even if they are immediate.

The largest constitutional obstacles to the introduction of direct democratic instruments at the federal level set in Germany's political system of federalism and particularly pronounced in the Federal Republic of precedence of the Basic Law . The democratic theory arguments do not differ in the German debate fundamentally from those in other countries. However, negative attitudes towards the introduction of nationwide referendums are often justified with the " Weimar experience ", while positive attitudes often go hand in hand with party criticism or react to it.

History of direct democracy in Germany

Direct democratic demands in the 19th and early 20th centuries

In the age of the Restoration , the reception of radical democratic French, Swiss or American masterminds of direct democracy in Germany had no place. This also applies to the few remaining oligarchic written republics . In the pre- March period, German representatives of the democratic movement such as Moritz Rittinghausen , Julius Fröbel , Johann Jacoby and Hermann Köchly articulated direct democratic demands for the first time. However, after the revolution of 1848 in the Frankfurt National Assembly , their proposals had no chance even in the circle of the democratic left, the “ Donnersberg faction ”. The Liberals had an aversion to the " people " as a mass guided by lower instincts, which, as in the French Revolution , could be incited and prone to violent excesses. Instead, the system of parliamentary representation based on the British model was widely accepted.

It was not until after 1860, the labor movement in Germany was formed, the proposals Moritz Rittinghausens found of a broad following and went 1869 in the Eisenach program and 1875 in the Gotha Program of the SPD one. In the early 20th century, representatives of left-wing liberalism began to consider direct democratic procedures.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had rejected popular legislation with reference to the social structure and political immaturity of large sections of the German population that would have favored conservative and reactionary forces. They propagated a council democracy , which represents a special form of democratic directness. Her main concern was the (re-) entanglement of economy and politics in the sense of a socialist production community, the democratic-theoretical aspects took a back seat. The concept was implemented briefly in the Soviet republics after the First World War and the November Revolution . Basic democratic and direct democratic instruments in the council model were people's assemblies , the imperative mandate , the connection of elected representatives to the will of the people through the permanent option of voting out and the principle of rotation , plebiscites and referendums. The Munich Soviet Republic in particular gained importance, but on 2/3 May 1919 after less than a month dejected.

Weimar Republic

Referendums and referendums in the Weimar Republic

Direct democratic instruments were first introduced in Germany in the Weimar Republic . Articles 73 to 76 of the Weimar Constitution determined the basic direct democratic procedures. The exact regulations were laid down in the law on the referendum of June 27, 1921 and in the Reich voting regulations of March 14, 1924.

The constitution granted the population the right to submit a bill to parliament with the signatures of at least ten percent of the eligible voters by means of a referendum. If Parliament did not agree to this, a referendum was held, the success of which depended on 50 percent of the electorate taking part and, moreover, the majority of the participants voting in favor. The Reichstag could demand a referendum if a constitutional amendment it had decided on was rejected by the Reichsrat . In addition, a third of the members of the Reichstag could initiate a referendum on a passed law. In this case, the support of five percent of the electorate was also necessary. Finally, the Reich President was able to order a referendum on a law passed by the Reichstag. Only the Reich President could initiate a referendum on the budget, tax laws and pay regulations.

Basically, the political system of the Weimar Republic was designed as a parliamentary democracy and a party democracy . In normal political situations, neither the popularly elected Reich President nor the people's legislation, but the Reichstag, should be the organ of legislation and control of the Reich government. The direct democratic procedures were rather intended as a corrective counterweight to party democracy and to “ parliamentary absolutism ” in individual cases and thus as a supplement to the representative system. In addition, the hope played a role of being able to educate the people through active participation in political culture and responsibility and to create acceptance for democracy. In the given desolate situation and in view of the weak democratic tradition in Germany, this was an optimistic plan. The key spokesmen for the democratic parties were aware of the risk, but were convinced that the Weimar Constitution as a whole would have little chance of lasting existence without a comprehensive democratization of the population. The introduction of direct democratic procedures was also not based on a model in the constitutional order of another similarly large and inhomogeneous state.

Only three plebiscites took place at the national level, only two of which made it to the referendum. These bills were, not without controversy, classified by the Reich government as changing the constitution and could not achieve the necessary approval of the majority of those entitled to vote. However, both would have failed even with the participation quorum of 50 percent for simple laws. In 1926, the expropriation of the princes, supported by the KPD and SPD , failed due to the quorum, although the debate escalated into one of the most comprehensive political disputes in the Weimar Republic. The popular initiative “Against the building of the armored cruiser” , supported by the KPD, failed in 1928 with 1.2 million signatures, even at the signature quorum. The referendum against the Young Plan , which had been supported by the NSDAP and DNVP , also failed significantly in 1929 with only 14.9 percent participation. In practice, the referendums were mostly organized by the opposition parties. In view of the high participation and approval quorum, the tactic of the respective opponents of the referendums was not to fight for a majority, but to boycott the vote.

In most countries, direct democratic procedures found their way into the respective state constitution, as it existed at the national level. With the first referendum in German history, the Baden state constitution was adopted on April 13, 1919 . This remained the only constitution of the Weimar Republic passed through a referendum. Up to 1933 a total of twelve direct democratic votes were held in the federal states, most of which were aimed at the premature dissolution of parliament. Such a referendum was only successful once, when the Oldenburg State Parliament was dissolved in 1932. The other attempts, including the referendum to dissolve the Prussian state parliament brought about by anti-democratic right-wing parties and organizations ( Stahlhelm , DNVP, NSDAP and others) and the KPD , failed because of the necessary quorum.

Referendums on territorial changes based on the Versailles Treaty

On the basis of Articles 88, 94 and 104 of the Treaty of Versailles were in a number of border areas with significant national minorities referendums held. The decision was made in each case as to whether the voting areas should remain with Germany or join the neighboring countries of Denmark or Poland. Other assignments of territory were carried out without referendums.

Several referendums in Schleswig in February and March 1920 indicated that North Schleswig should in future belong to Denmark, while Central Schleswig should continue to belong to the German Empire. In the voting area Marienwerder (West Prussia province) and in the Allenstein voting area (East Prussia province), an overwhelming majority voted to remain with Germany on July 11, 1920. On March 20, 1921, further referendums followed in Upper Silesia and a small part of Lower Silesia . While in Lower Silesia there was also a clear majority in favor of remaining with Germany, the result in Upper Silesia was territorially very inconsistent. In the larger western part of the province, a clear majority favored staying with Germany, while the smaller eastern part around Katowice with its valuable coal mines voted just as clearly in favor of joining the Polish Republic. To address this dilemma, an ambassadorial conference in Paris decided to divide Upper Silesia along the so-called Sforza Line , with western Upper Silesia remaining as a province with Germany and the smaller eastern part of the Polish Autonomous Voivodeship of Silesia .

time of the nationalsocialism

During the dictatorship of the National Socialists , the referendum law of July 14, 1933 replaced Articles 73–76 of the Weimar Constitution, which were not formally repealed. It made it possible for the Reich government to initiate a referendum, the subject of which could be not only laws but also “intended measures” in general. The quorum and thus the possibility of veto through a boycott of votes were abolished. Since only a positive vote was binding, the referendums were simply referendums .

On this basis, four referendums were carried out, which, however, did not have "intended measures" as their content, but were intended to legitimize acts that had already been carried out. The first to take place on November 12, 1933, was a referendum on Germany's withdrawal from the League of Nations . On August 19, 1934, there was one about the head of state of the German Reich , with which the offices of Reich President and Reich Chancellor were combined and transferred to Adolf Hitler as Führer and Reich Chancellor . In addition, there was the referendum on March 29, 1936, authorizing the occupation of the Rhineland, and on April 10, 1938, the referendum on the reunification of Austria with the German Reich on the connection of Austria . The participation rate was between 95.7 percent and 99.7 percent, the approval rate between 88.1 percent and 99.0 percent.

Due to the disregard of the principles of a democratic vote , newly created democracy concepts and “ folk- plebiscite” concepts of the state, these referenda are considered to be an abuse of direct democratic procedures. They had the function of pseudo-legalistic acclamations of previously taken decisions of the imperial government. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that the vast majority of Germans agreed to the voting proposals out of conviction.

Referendum question as the last Germany in the wake of the Versailles Treaty was on 13 January 1935 the Saar plebiscite on the membership of the under League of Nations mandate standing Saar voted. The vote resulted in a majority of 90.7 percent for Germany, so that the Saar area was annexed to the German Reich.

GDR

The first direct democratic vote in the post-war period took place in the Soviet occupation zone before every state election. The referendum in Saxony on June 30, 1946 envisaged the expropriation of large landowners, war criminals and active National Socialists without compensation . With a participation of 93.7 percent, 77.6 percent voted for the law and 16.6 percent against.

The constitution of the German Democratic Republic of 1949 determined referendums and referendums as instruments of the legislature , which should stand alongside the People's Chamber on an equal footing . Accordingly, ten percent of the electorate or the recognized parties and mass organizations could apply for a referendum. A simple majority was required to pass the bill. The People's Chamber could also be dissolved by a referendum.

Referendums were also anchored in the constitutions of the five countries of the Soviet occupation zone and the GDR that were passed in 1946/47 . In the constitution of the state of Thuringia of December 20, 1946, it said: "The people realize their will through the election of the people's representatives, through referendums, through participation in administration and jurisdiction and through comprehensive control of the public administrative organs." were incorporated into the other state constitutions.

The statutory provisions on referendums remained theoretical. In the only referendum in GDR history, a new constitution was voted on in 1968. The initiative came from the Central Committee of the SED . On April 6, 1968, the draft constitution was approved by referendum, which, however, did not correspond to democratic principles without the possibility of a secret vote and free discussion. Nevertheless, a relatively large number of citizens dared to object. Instead of the usual results of 99 percent approval for elections in the GDR, approval of 96.37 percent of the votes cast and 3.4 percent of votes against was shown even in the official result. Three days later, the new constitution officially came into force, in which the possibility of a referendum was no longer included. The People's Chamber, on the other hand, could still decide to hold a referendum.

In addition, in the 1950s there were two referendums that were not provided for in the constitution and aimed at propaganda. In 1951, with a turnout of 99.42 percent, 95.98 percent of those who voted were against rearmament in the Federal Republic and in favor of a peace treaty , while 4.02 percent voted against. Despite a ban by the authorities of the Federal Republic of Germany, a parallel vote took place there, in which, according to the organizer, the KPD-affiliated Main Committee for Public Polls, 6,267,312 people took part, which would have represented a turnout of around 20 percent. 94.42 percent of those who voted should have voted “yes” and 5.58 percent with “no”. After the Federal Republic of Germany had ratified the General Treaty and the Treaty establishing the European Defense Community (EDC) with the three Western powers France, Great Britain and the USA, which later did not come into force , the People's Chamber decided to conduct another referendum in 1954. With a turnout of 98.60 percent, 93.46 percent voted for a peace treaty and a withdrawal of the occupation troops, 6.54 percent voted for the EVG. A parallel survey in the Federal Republic did not take place this time.

After the upheavals in autumn 1989 , the Central Round Table set up a working group on the “New Constitution of the GDR”, which was supposed to work out a draft constitution by the Volkskammer election on May 6, 1990. After the election date had been brought forward to March 18 and the central round table had dissolved immediately afterwards, the working group handed the draft to the newly elected members of the People's Chamber on April 4, 1990. The draft constitution provided for extensive opportunities for direct democratic participation. At this point, however, significant decisions had already been made, and the composition of the People's Chamber, in which the CDU had become by far the strongest party, differed significantly from that of the Round Table, so that the draft no longer played a role in the rapid course of the unification process. The People's Chamber refused to refer him to the committees even for further advice. In the last municipal constitution of the GDR from May 1990, the referendum was anchored, which was included in all municipal codes of the new federal states after reunification .

Federal Republic

post war period

Decisions in the creation of the Basic Law

The Frankfurt documents that emerged from the London Six Power Conference and passed on July 1, 1948, provided for a constitution to be ratified by referenda in the federal states . To underline its provisional character and the German division not to cement, the prime ministers of the countries decided in the three western zones but on the Knights fall conference from 8 to 10 July 1948, the term "constitution" to dispense and the " Basic Law “To be ratified by the state parliaments instead of a referendum. The constitutional convention at Herrenchiemsee , which met from August 10 to 23, 1948, agreed on the stipulation that there should be no referendum in the constitution to be drawn up, but that there should be an obligatory referendum in the event of changes to the Basic Law . The Parliamentary Council after controversial debate of this recommendation, and decided to include more no plebiscitary elements in the Basic Law, but entirely on the representative democracy to prevail.

In retrospect, this decision was interpreted as the result of specific experiences from the Weimar Republic. More recent research, however, emphasizes that it was essentially time-related. The most important reasons for the negative attitude were therefore the fear of an abuse of referendums by the SED or the KPD in the emerging Cold War , the provisional character that the Basic Law should have, and the difficulties that referendums would have in view of the destroyed infrastructure in the Post-war period . The parties fluctuated between affirmation in principle and rejection of direct democracy based on the situation, but none of the parties in the Parliamentary Council refused to accept direct democratic procedures in general. Rather, the Parliamentary Council wanted to protect the young democracy from itself for a transitional period and put direct democracy into " quarantine ", but did not want to rule out direct democratic procedures once and for all.

Direct democratic procedures in the first state constitutions

| Introduction of referendums and citizens' decisions in the federal states |

||

|---|---|---|

| country | folk decisive |

Citizens' decision |

| Bavaria | 1946 | 1995 |

| Hesse | 1946 | 1993 |

| Bremen | 1947 | 1994 (districts) |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 1947 | 1994 |

| Baden (South Baden) | 1947 | - |

| Württemberg-Hohenzollern | 1947 | - |

| Berlin | 1950 (to 1975) / 1995 | 2005 ( districts ) |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 1950 | 1994 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 1974 | 1955 |

| Saarland | 1979 | 1997 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 1990 | 1990 |

| Brandenburg | 1992 | 1993 |

| Saxony | 1992 | 1993 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 1992 | 1990 |

| Lower Saxony | 1993 | 1996 |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 1994 | 1993 |

| Thuringia | 1994 | 1993 |

| Hamburg | 1996 | 1998 ( districts ) |

The constitutional deliberations in the countries and the debate about the Basic Law influenced each other, not least because most of the members of the Parliamentary Council were also active in a country's constituent assembly. All pre-constitutional state constitutions provided for direct democratic procedures based on the model of the Weimar imperial and state constitutions, whereby the required quorums were significantly increased except in Bavaria. After the adoption of the Basic Law, only the constitution of North Rhine-Westphalia incorporated the people's legislation, but the relevant regulations had already been passed by a large majority in July 1948. Likewise, in 1947 seven were to October state constitutions adopted by referendum, then only that of North Rhine-Westphalia in June 1950. The rest were adopted by the diets.

In Hesse, Rhineland-Palatinate and Bremen, the referendum on the state constitution was also used in special votes on individual controversial articles. In Hesse this concerned Article 41 on the possibility of socialization, in Rhineland-Palatinate Article 20 on the organization and role of schools in the state and in Bremen Article 47 on the question of employee participation.

Stagnation of direct democracy in the Bonn Republic

The federal level until reunification

In 1958, the SPD parliamentary group requested a non-binding “referendum on nuclear armament of the Bundeswehr” as a confirmative referendum by the sovereign parliament, which did not require any constitutional change. The government majority rejected the request. The SPD-led Hessian state government opposed the request from Bonn to stop referendums initiated by local authorities, but failed before the Federal Constitutional Court.

The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung , which is close to the CDU, assessed the demand made by the NPD for referendums at the federal level and the direct election of the Federal President in 1969 as a "demand for the elimination of the present-day stability of democracy in the Federal Republic", since this is done by renouncing such direct democratic ones Elements could have been achieved.

The rejection of plebiscitary elements at the federal level by the Parliamentary Council was not questioned in the Bundestag for a long time. In its final report submitted in 1976, a study commission for constitutional reform rejected all forms of direct participation in factual questions with broad consensus.

It was only when the Greens, founded in 1980, moved into parliament after the parliamentary elections in 1983 that the issue of direct democracy was raised again in the Bundestag. In 1983 the Greens introduced a bill to conduct a consultative referendum on the stationing of medium-range nuclear missiles as part of NATO's double decision . Attempts to use the possibilities of the people's legislation in Hesse and Baden-Wuerttemberg for appropriate initiatives failed because of the federal competence in matters of defense. The “Aktion Volksentscheid”, founded by a group of the Greens, sent a collective petition to the Bundestag in 1983 to introduce popular legislation at the federal level. She argued that the introduction of people's legislation did not require any constitutional amendment, as Article 20 of the Basic Law already allowed this. On the recommendation of the Petitions Committee , the plenum declared the petition against the votes of the Greens to be closed because of constitutional concerns.

Direct democracy in the countries until 1989/90

In the case of the restructuring of the federal territory , i.e. when the federal states were amalgamated or split up, an obligatory referendum was stipulated by the Basic Law in 1952 when the federal state of Baden-Württemberg was founded . At the municipal level, Baden-Württemberg, where the citizens' initiative was introduced into the municipal code in 1955 , is the “motherland of direct democracy”.

In 1955 a confirmative referendum was held in Saarland , which at the time did not belong to Germany . In the referendum , 67.7 percent of those entitled to vote spoke out against autonomy within the framework of the European Saar Statute as an extra-state special territory of the Western European Union . The Saarland government then entered into negotiations with the German federal government, and Saarland joined the Federal Republic of Germany on January 1, 1957.

In 1968 Bavaria saw the first referendum on community schools based on a referendum. Outside of Bavaria, apart from a few votes on territorial changes, there was not a single one until 1997.

In 1974 Baden-Württemberg and in 1979 the Saarland introduced the people's legislation, whereby the prescribed quorums were set extremely high. In Berlin, on the other hand, the referendum, which was never put into concrete terms by an executive law and consequently never applied, was deleted from the constitution in 1974.

Expansion of direct democratic procedures since 1989/90

Legislative initiatives in the Bundestag

| Legislative initiatives to introduce nationwide referendums |

||

|---|---|---|

| year | initiative | approval |

| 1992 | Green | |

| 1998 | Green | |

| 1999 | PDS | |

| 2002 | SPD / Greens | 63.38% |

| 2006 | PDS | |

| 2006 | FDP | |

| 2006 | Green | |

| 2010 | left | 9.81% |

| 2013 | SPD | |

| 2014 | left | |

| 2016 | left | |

The Joint Constitutional Commission set up after reunification worked out proposals for the introduction of three-tier national legislation at the federal level. No other topic of the deliberations was so in the center of public interest, as 266,000 petitions to the Constitutional Commission show. In the commission, the motions of the SPD and the Greens for the introduction of a popular initiative, referendum and referendum received simple majorities, but the two-thirds majority required to amend the Basic Law did not materialize. The widespread demand for a final referendum on the Basic Law and its reform in accordance with Article 146 of the Basic Law also failed. A motion by the SPD to amend Article 146 of the Basic Law so that a referendum should decide the question of the seat of the Bundestag and the federal government was also unsuccessful.

In November 1992 and March 1998 the Greens, and in June 1999 the PDS unsuccessfully introduced bills for nationwide referendums in the German Bundestag. After the victory of the SPD and Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen in the Bundestag election in 1998 , the introduction of direct democratic procedures at the federal level was included in the coalition agreement . In March 2002, the red-green government introduced a corresponding draft law to introduce three-stage national legislation at federal level in the Bundestag. This received a majority of 63.38 percent and thus only just failed due to the required two-thirds majority. The PDS, 14 members of the FDP, including the party chairman Guido Westerwelle and the parliamentary group chairman Wolfgang Gerhardt , as well as the CDU member and former Federal Minister Christian Schwarz-Schilling also voted for the motion by roll call . In 2003 and 2004, the FDP introduced two requests for a referendum on the adoption of a European constitution in the Bundestag. In 2006, the PDS , the FDP and Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen, each with separate bills, made new attempts for a nationwide referendum, another followed in 2010 by Die Linke . In 2012, the CSU put a motion for a resolution on referendums at federal level on fundamental questions of European policy in the Bundesrat. In June 2013, the SPD again introduced two bills on people's legislation to the Bundestag. In March 2014, the Left took another attempt with a draft law to introduce the three-stage people's legislation, which was largely based on the proposals of the association Mehr Demokratie .

Developments in federal states and municipalities since 1989

Two developments in 1989/90 led to a period of expansion of direct democracy in the federal states and municipalities: on the one hand, the upheavals in the GDR and, on the other hand, the constitutional reform in Schleswig-Holstein after the Barschel affair set a new dynamic in the development of direct democratic procedures in progress. With the SPD-ruled Schleswig-Holstein in 1989, a federal state reintroduced popular legislation for the first time and set relatively low hurdles. The introduction of the popular initiative as the first step in a three-phase process was new . 1997 saw the first referendum outside Bavaria based on a referendum in Schleswig-Holstein. In addition, Schleswig-Holstein was the second state after Baden-Württemberg to create far-reaching forms of participation with low hurdles with the referendum and referendum .

In all of the new state constitutions of the East German federal states passed between 1992 and 1994 through a constitutional referendum, referendums and referendums were anchored according to the Schleswig-Holstein model. Lower Saxony, Berlin and Hamburg followed this example until 1996, so that people's legislation has since been anchored in all federal states. The existing regulations were reformed in Bremen, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate.

A planned amalgamation of the federal states of Berlin and Brandenburg , for which the Basic Law stipulated an obligatory referendum as a reorganization of the federal territory, was rejected by the population in 1996. Several referendums have attracted a lot of attention, especially in recent times. These include the referendums Pro Reli in Berlin (2009), on the protection of non-smokers in Bavaria and on the school reform in Hamburg (both in 2010), on the disclosure of the partial privatization agreements with the Berliner Wasserbetriebe and Stuttgart 21 (both 2011) and on the Remunicipalisation of the Hamburg and Berlin energy supply (both 2013). Nevertheless, even in countries with relatively low hurdles, people's legislation remained an exception with little practical importance and did not result in any fundamental change in the parliamentary system or party democracy.

The municipal constitution of the GDR , in which the referendum was anchored in May 1990, initially continued to apply even after the re-establishment of the new federal states and accession to the Federal Republic. All new municipal regulations in the new federal states took over the provisions of the GDR municipal constitution on direct democratic procedures. As with the people's legislation at the state level, all territorial states followed this development up to 1997. Citizens' petitions and referendums in Bavaria were added to the municipal code in 1995 by referendum on the initiative of the association Mehr Demokratie . By 2005, the city-states had also introduced referendums in their districts.

The design of direct democracy in the Federal Republic

The position of referendums in the Basic Law

The Basic Law has no right of initiative for the people. However, Article 20, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law regulates : “All state authority comes from the people. It is exercised by the people in elections and votes [...]. ”Since“ elections ”always relate to people and“ votes ”always relate to factual issues, people's legislation is in principle covered by the Basic Law. In Art. 76 GG, however, the legislative procedure is set out without “the people” being mentioned there. The Federal Constitutional Court and the vast majority of constitutional lawyers interpret this contradiction today in such a way that plebiscites can be introduced at the federal level, but only after Article 76 of the Basic Law has been supplemented with appropriate wording.

The Basic Law provides for an obligatory referendum for two cases: first, when the federal territory is reorganized in accordance with Article 29 of the Basic Law, in which only citizens entitled to vote in the affected areas are entitled to vote, and second, when the Basic Law is replaced by a constitution ( Article 146 GG). The obligatory nationwide referendum according to Article 146 of the Basic Law on a new constitution was planned by the Parliamentary Council in the event of German reunification . Since the Federal Government decided in 1990 to prevent reunification via Art. 23 GG a. Art. 146 of the Basic Law has not yet come into effect to bring about F. - that is, via the accession of the new federal states to the federal territory. But regardless he bids to continue that a comprehensive revision of the Constitution or drafting a new constitution mandatory in a nationwide constitutional referendum would have to be confirmed.

Direct democracy in the federal states

People's legislation

| Obstacles of the people's legislation in the countries with simple laws |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| country | Referendum | Referendum | |

| quorum | Deadline |

Approval quorum |

|

| BW | 10% |

6 months, free collection plus 3 months official registration within the deadline |

20% |

| BY | 10% | 14 days, official registration | - |

| BE | 7% | 4 months, free collection and registration | 25% |

| BB | approx. 3.8% | 6 months, official registration | 25% |

| HB | 5% | 3 months, free collection | 20% |

| HH | 5% |

21 days, free collection and registration |

- |

| HE | 5% | 2 months, official registration | 25% |

| MV | approx. 7.5% | 5 months, free collection | 25% |

| NI | 10% | min. 6 months, free collection | 25% |

| NW | 8th % |

1 year, free collection plus official registration in the first 18 weeks |

15% |

| RP | approx. 9.7% | 2 months, free collection and official registration |

25% participation quorum |

| SL | 7% | 3 months, official registration | 25% |

| SN | approx. 13.2% | 8 months, free collection | - |

| ST | 9% | 6 months, free collection | 25% |

| SH | approx. 3.6% | 6 months, free collection and registration | 15% |

| TH | 8 or 10% |

2 months official registration or 4 months free collection |

25% |

Popular legislation is anchored in the constitutions of all federal states . This is understood to mean those direct democratic processes in which the right of initiative in the legislative process lies with the people. Most countries have a three-tier national legislation . Bavaria and Saarland, on the other hand, practice a two-stage process of people's legislation .

The design of the direct democratic procedure differs more strongly in the federal states than any other area of the state government systems and is accordingly differently effective. While, for example, in Bavaria , Berlin and Hamburg is comparatively citizen-friendly and thus more frequent referendums take place, the barriers to initiatives from the people by circumferential in Hesse or in Saarland topic exclusions on the obligation to official registration or short collection periods up to almost insurmountable quorum so high that there has never been a referendum. The people's legislation in the federal states is restricted by the transfer of powers to the federal government and increasingly to EU institutions.

The popular initiative is the first stage in the three-stage national legislative process. With it, the people have the opportunity to bring a matter determined by them into the deliberations of the state parliament in the form of a signature campaign . The latter must deal with the proposal in plenary, but is free to decide whether to approve or reject the proposal. If the state parliament does not accept the initiative, a referendum takes place. In the two-stage process, the popular initiative either does not exist at all, or it is just like a non-binding mass petition . Instead, a petition for a referendum is sufficient to set it in motion.

The next stage is the referendum . The subject of a referendum must always be a formal law that falls within the legislative competence of the country and for which there is no subject exclusion . All state constitutions exclude the so-called “financial triad” of budget laws , taxes and salaries from the people's legislation - which in many federal states also indirectly affects financially effective laws. It is also regulated differently whether there is compensation for the costs incurred by the initiators in the referendum, analogous to the reimbursement of election campaign costs .

If the state parliament rejects a successful request, there is a referendum in which a binding vote is taken. In practice, the required approval or participation quorums are the greatest hurdle for the initiators. 6 of the 24 referendums (up to July 2018) " failed ", which means that they failed due to the required quorum despite the sometimes overwhelming approval. While those referendums that take place together with federal or state elections had an average turnout of 61.8 percent, those without such a link only had 34.1 percent of those entitled to vote. State governments repeatedly tried to hinder referendums by exploiting this fact. After two severe defeats in referendums in 2004, the Hamburg CDU succeeded in ensuring that referendums no longer have to take place together with elections. However, the Hamburg Constitutional Court repealed this change, so that Hamburg is still the only country in which voting is expressly linked to elections. The Berlin Senate set the date for the referendum on the remunicipalisation of Berlin's energy supply on November 3, 2013, although it would have been possible to combine it with the Bundestag election on September 22, 2013 and the additional date resulted in costs of 1.4 million euros . With an approval of 83.0 percent, the referendum just failed to meet the required quorum.

Mandatory parliamentary / government referendums and referenda

There is a mandatory referendum only in Bavaria and Hesse on all constitutional issues. Here, all constitutional amendments passed by parliament must be confirmed in referendums, most recently in October 2018 in Hesse on 15 constitutional amendments.

In Baden-Württemberg, Bremen and Saxony the parliament, in North Rhine-Westphalia the parliament or the government can call a referendum if a constitution-amending law fails in the parliamentary procedure.

Baden-Württemberg, Hamburg and Rhineland-Palatinate know special cases of referendums with which simple laws can be presented to the people. In Baden-Württemberg, this can be done through joint action by a parliamentary minority (one third) and the state government. In Hamburg, two thirds of parliament and the government can jointly call a referendum. Rhineland-Palatinate knows a combination of a parliamentary minority (one third) and the signatures of 5 percent of the electorate.

A correction referendum, analogous to the optional referendum in Switzerland, with which a law that has already been passed can be subjected to a further decision at the request of the people, is available for certain political issues in Hamburg and Bremen.

In addition to a referendum on a new constitution, the reorganization of the federal territory is the only referendum case that is regulated in the Basic Law. The referendums required for this will only take place in the affected areas.

Dissolution of parliament and popular action

The state constitutions of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Berlin, Brandenburg, Bremen, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate provide for the possibility of plebiscitary dissolution of parliament . The quorums for a successful referendum are higher for a motion to dissolve the state parliament than for legislative initiatives. In the history of the Federal Republic, no referendum with the aim of dissolving parliament has yet been carried out.

Only in Hesse there is the instrument of the public complaint . This can be used to request a review of a law or a statutory ordinance for its constitutionality . For this, one percent of the electorate must support the application. In 2007, the review of the law introducing tuition fees was demanded by a public complaint. Such an abstract judicial review complaint is otherwise reserved for constitutional bodies.

Jurisprudence on popular legislation

The Bavarian Constitutional Court first carried out a normative review of a people's law in 1997 when it examined the 1995 law on the introduction of the municipal referendum, which was passed through a referendum . He declared one provision to be unconstitutional and null and void , and two other provisions, at least in combination, to be inconsistent with the constitution. In 1999 the Senate of the Bavarian Constitutional Court decided that the constitution required a quorum of 25 percent. In doing so, he changed a case law practiced since 1949 that the legislature was not allowed to set up a quorum according to the constitution. In 2000 he decided that the content of the popular initiative “Fair referendums in the country” contradicted the basic democratic idea of the constitution. The increasingly restrictive jurisprudence of the Bavarian Constitutional Court ensured a great response and critical evaluations in the legal literature.

An important fundamental legal question is whether referendums can also decide questions that affect budget law, or whether this is a privilege of parliaments. A unanimous line of the jurisprudence of the constitutional courts of Bremen , Schleswig-Holstein and Brandenburg prohibits such direct democratic projects that have a significant impact on the state budget. The Federal Constitutional Court found in one case that a referendum had to be rejected because 0.7 percent of the budget was affected.

Direct democracy at the local level

| Obstacles to referendums and referendums | ||

|---|---|---|

| country | Citizens' petitions (signature hurdle) |

Referendum (approval quorum) |

| BW | 4.5-7% | 20% |

| BY | 3–10% | 10-20% |

| BE ( districts ) | 3% | 10% |

| BB | 10% | 25% |

| HB (City of Bremen) | 5% | 20% |

| HH ( districts ) | 2-3% | no quorum |

| HE | 3–10% | 15-25% |

| MV | 2.5-10% | 25% |

| NI | 5-10% | 20% |

| NW | 3–10% | 10-20% |

| RP | 5-9% | 15% |

| SL | 5-15% | 30% |

| SN | 5-10% | 25% |

| ST | 4.5-10% | 20% |

| SH | 4-10% | 8-20% |

| TH | 4.5-7% | 10-20% |

In all federal states, a matter can be brought before the municipal council at the municipal level using the instrument of the citizens' initiative . Takes not this desire, the voters, in a referendum vote directly on the application. The municipal council can also bring about a referendum by means of a council request .

Citizens' petitions and referendums are the exception in local politics in some federal states, as a number of subject areas are excluded from the decision and because the required quorum is often difficult to achieve. How high the hurdles are for a referendum varies greatly between the individual states, with the relevant regulations being determined by the respective state parliament. In Bavaria there were 1,786 referendums up to 2017, in Saarland, however, none at all. Between 1956 and 2017 there were a total of 6,261 referendums and 1,242 referendums initiated by the municipal councils. More than half of the direct democratic processes at local level took place between 2003 and 2017, around 300 per year in recent years. The participation in referendums averaged 50.2 percent. Participation fell as the number of inhabitants increased, which makes it difficult to achieve the required approval quorum in large cities.

The resident or citizen application lies in the border area between mass petition and plebiscitary participation. With him, drafts can be submitted to the municipal representation, but he does not have an immediate decision-making effect. Other forms of participation such as citizens' assemblies , question times or informal round tables belong even less to the area of direct democracy, since they are not aimed at binding decisions. The authority of the decision-making bodies to act remains unaffected.

In parallel to the implementation of direct democratic procedures at the municipal level, direct elections of mayors and district administrators have been established in Germany since the early 1990s . Whether the direct election is a direct democratic procedure is controversial and is mostly denied, since personnel decisions do not represent an intervention by the electorate in specific political issues, but only interventions in the representative system. Otherwise become part deselection rated as the participation rights go beyond this the normal level of empowerment in representative democracy. The hurdles for recalling directly elected mayors are much higher than for referendums. A spectacular example was the referendum on the voting out of the Lord Mayor of Duisburg in February 2012.

Other direct democratic areas

Approaches to citizen participation at the European level

With the Treaty of Lisbon , the European Citizens' Initiative was adopted, with which Union citizens can get the European Commission to deal with a specific topic. For this purpose, a total of one million valid statements of support must be collected in a quarter of all EU member states in twelve months . The European Citizens' Initiative is made easier by the option of collecting signatures online . It has been available for use since April 1, 2012.

Since the Commission is free to decide independently of a European Citizens' Initiative, this is only a weak direct democratic procedure that is largely like a mass petition . There are no binding votes, i.e. a Europe-wide referendum. Likewise, there is no instrument that can put an issue on the European Parliament's agenda .

Strike votes in parties and trade unions

Direct democratic procedures also play a role within non-governmental organizations. The strikers guidelines of the German Trade Union Federation (DGB) provide a strike a strike ballot before the union members affected by the labor dispute. According to the statutes of most trade unions in Germany, at least 75 percent of all affected voting members must vote secretly.

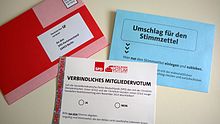

More recently, especially the experiment political parties reinforced with members deciding to the inner-party democracy to strengthen. The Greens took on a pioneering role , for whom grassroots democracy was a defining point of orientation and who, when they were founded in 1980, included membership decisions on factual and program issues in their statutes. In the Berlin Alternative List there was no system of delegates until the early 1990s, but decisions were generally made at plenary meetings . The Hessian state association decided in 2013 at a state assembly on the acceptance of the coalition agreement with the CDU. In the run-up to the 2013 Bundestag election , the party members of Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen voted in a membership decision on the issues that should be given priority in the election campaign and in possible coalition negotiations. In 2000 the Greens in Baden-Württemberg held their first virtual party congress without delegates .

The SPD introduced the member survey in 1993, the results of which are binding. Ten percent of the party members can request a membership decision. A corresponding attempt to hold a ballot against Agenda 2010 and thus against the then incumbent SPD party chairman and Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder failed. The most spectacular case of direct democratic participation by party members was the SPD's member vote on the 2013 coalition agreement in December, which decided whether Germany would be governed by a grand coalition . The turnout was about 78 percent.

At the FDP , the federal executive carried out two ballots in 1995 and 1997 on the great bugging attack and on general conscription . In 2011 there was the first membership decision enforced by the grassroots in the party. The so-called euro-skeptics wanted to assert against the party leadership that the party prevented the establishment of a permanent euro rescue package . However, they failed because of the quorum of 33.3 percent of party members. In contrast to other parties, where personnel issues are generally decided more often by primary election , the FDP only knows members' decisions on factual issues.

The CDU statute also allows members to be questioned on personnel and factual issues, but this can only be initiated by the party leadership. It has been anchored in the statutes of the CSU since 2010. The Pirate Party broke new ground with the LiquidFeedback software .

Debate about the introduction of referendums at federal level

Democratic theoretical considerations, interpretations of the “Weimar experiences” and empirical democracy research

Theodor Heuss , who later became Federal President, received much applause during the deliberations of the Parliamentary Council and for a long time afterwards for the thesis that referendums are a “bonus for every demagogue ”. The German people in particular lack democratic maturity. In the Bonn Republic, this line of argument became independent of a social criticism that shaped a negative image of direct democracy: The people as a mass are easily seduced, they basically lack the competence to oversee complex decisions, and they are less committed to the common good than to their own interests and tend to have mood swings. Direct democratic procedures are anti- compromise, the majority principle can result in anti-minority laws in referendums . Opponents of referendums at the federal level assume that the representative system of the Federal Republic has proven itself and that changes pose a threat to parliamentary democracy and federalism. The lawyer and political scientist Ernst Fraenkel was particularly influential, who saw the people's legislation as a fundamental threat to the party state .

This attitude is often justified with the "Weimar experience". The thesis of the erosion of democracy in the Weimar Republic by the popular initiative became a commonplace after 1945 with considerable historical relevance. The post-war era was characterized by a "plebisphobia". Ernst Fraenkel put it in 1964: “At the time of its birth, the Weimar Republic committed itself to a plebiscite type of democracy; at the hour of her death she received the receipt. "

Recent research in contemporary history has largely rejected this thesis. The specific design of the direct democratic procedure was problematic. In particular, the high participation quorum made it easy for opponents of a referendum to bring it down by boycotting the democratic process instead of fighting for a majority in the vote. The already weak anchoring of democracy in society was thus reinforced. The remarkably few and also unsuccessful referendums and referendums have in practice remained sidelines of the political debate. Representative democracy, especially in the Reichstag elections , offered the extremists greater opportunities for agitation and mobilization.

Today, empirical democracy research emphasizes the structure-conserving and integrating function of direct democracy rather than simply assuming a destabilizing effect, as was previously the case. However, this only applies to functioning democracies. The extraordinary stability of the Bavarian political system is often associated with the lively direct democracy in Bavaria , through which the decades of dominance of the CSU can be corrected if necessary. The same finding is diagnosed with a view to direct democracy in Switzerland , which has contributed to stable politics and the maintenance of federal structures and where no more “wrong decisions” are made overall than in purely representative systems.

A positive attitude towards direct democratic procedures often results from the diagnosis of a long-growing and widespread political and especially party disenchantment in Germany , which has developed from an outsider position into common knowledge since the early 1990s. The representative system is in a crisis, the democratic control of the political class no longer works, parliamentary decisions lack legitimacy , the political elite acts self-centeredly, so that reforms are blocked. One of the main reasons cited is that at the federal level, beyond the general election every four years, no participation of the electorate in political decisions is provided. The lack of nationwide referendums and referenda is therefore sometimes assessed as a democratic deficit or a participation deficit.

The question of system compatibility

All advocates of direct democratic elements at the federal level aim to supplement representative democracy with direct democratic procedures. The subject of discussion is often, but not exclusively, the adoption of the three-tier national legislation as it exists in the federal states. The clear preference for people's legislation is not a German peculiarity, because in Europe Switzerland , Liechtenstein, Lithuania , Latvia , Croatia , Bulgaria , Slovakia and Hungary give the people a right of initiative in the legislative process. Procedures based on the model of the Swiss optional referendum and mandatory constitutional referendums are also discussed . Although no direct democratic procedure in the narrower sense, referendums "from above", with which the Bundestag can propose a law for a referendum, and non-binding referendums are also discussed.

From a constitutional point of view, some authors see a problem in the state principle , which requires the states to participate in legislation. The so-called “ eternity clause ” of Art. 79 Para. 3 protects this basic element of the state order laid down in Art. 20 Para. 1 against changes by the constitutional legislature. A right of consent of the Federal Council would not be compatible with a referendum, but most constitutional law experts today take the view that the Basic Law only requires the states to participate in legislation in principle, without making any statements about how this should be structured. A solution could be the adoption of the Swiss model, which in addition to the absolute majority of those voting (so-called " popular majority ") acceptance of the legislative initiative in the majority of cantons (so-called " cantons calls"). The majority of the national people would then correspond to the casting of the Federal Council votes of the respective country. Other considerations include the involvement of the Federal Council in the acceptance or rejection of popular petitions or in the preparation of a competition proposal from the Bundestag. In some cases, it is doubted that such proposals take sufficient account of the Länder's right to co-design. On the other hand, there are voices that indicate that fundamental participation by the federal states allows exceptions. If referendums remain a rare exception, according to this reading it would be permissible to focus solely on the result of the federal vote. In the case of optional constitutional referenda , referendums initiated by parliament and optional referendums , this problem would be completely eliminated, since the Federal Council would be involved in the legislative process in advance.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the constitutional principle goes particularly far with the final binding decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court. In order to be compatible with the system, laws resulting from referendums would have to be subject to the primacy of the Basic Law. A preliminary examination of the draft laws by the Federal Constitutional Court is therefore being discussed.

The competing legislation of referendums and parliamentary resolutions can be problematic. The Schleswig-Holstein state parliament caused a stir in 1999 when it reversed a negative referendum on the reform of German spelling after just under a year. At the local level, this problem is solved by setting certain deadlines in which referendums cannot be changed by the local council.

The party-political debate

For three decades, the politics of the Federal Republic was dominated by a three-party system made up of CDU / CSU , SPD and FDP , for which the introduction of nationwide referendums, and even the discussion about them, were considered taboo. The social-liberal coalition led by Willy Brandt, under the motto “ Dare more democracy !”, Did nothing to change this attitude . Even representatives of the New Left in the extra-parliamentary opposition did not rely on referendums, as these could also serve conservative forces.

It was not until the 1980s that a broader discussion about the compatibility of the Basic Law with direct democratic procedures began. Since German reunification, the debate has gained momentum and led to a clear change in opinion. Today all established parties except the CDU advocate the inclusion of direct democratic procedures in Germany's political system at the federal level. What is striking is the contradiction between the empirical finding, mainly obtained through comparative political science and polling research , that referendums have a predominantly conservative, slowing and sometimes anti-minority effect, and the fact that left and left-liberal politicians in particular support direct democracy.

The pioneers were the Greens , founded in 1980 , who, after entering the Bundestag in 1983, addressed direct democratic procedures again in parliament for the first time. A group of the Greens founded an "Aktion Volksentscheid" in 1983, the demands of which were incorporated into the Greens' election manifesto for the 1987 Bundestag election. With Gerald Haefner one of the founders in 1987 moved into the Bundestag. Häfner later co-founded the association Mehr Demokratie , became its spokesman for the board and a driving force in his parliamentary group on the subject of direct democracy.

After the Greens introduced the issue to the Bundestag, the SPD declared itself ready to discuss the principles of the introduction of direct democratic elements into the Basic Law, despite constitutional concerns. Since 1986 the SPD has also been advocating referendums and referendums at the federal level, initially cautiously, and finally included the demand in its Berlin program in 1989 . On the way there, there were some fierce controversies within the party.

In 2010 and 2014, the Left introduced its own bills on people's legislation in the Bundestag and in 2012 on referenda on changes to the European treaties . In 1999 and 2006, the PDS introduced legislative proposals for national legislation at federal level.

Since the 1980s, the FDP has also been in favor of strengthening citizens' participation rights. In the black-yellow coalition , however, she voted with the coalition partner against all corresponding legislative proposals by the opposition parties. In the opposition, on the other hand, in 2003 and 2006 the FDP brought in its own motions for a referendum on the EU constitution and people's legislation.

All legislative initiatives have so far failed due to the categorical rejection of the CDU, without which a constitution - changing two-thirds majority has never been possible. There are only a few voices within the CDU who are positive about direct democratic procedures at the federal level. However, the Saarland regional association decided in May 2003, under the leadership of the later Federal Constitutional Judge Peter Müller , to include the demand for three-stage national legislation in its program. The CSU has come to terms with the people's legislation in Bavaria and advocates referendums at the federal level on fundamental questions of European policy. During the coalition negotiations between the Union and the SPD after the 2013 federal election , Federal Interior Minister Hans-Peter Friedrich (CSU) and the SPD's parliamentary manager , Thomas Oppermann , formulated a far-reaching proposal for nationwide referendums. The proposal failed because of the CDU's veto .

Among the smaller parties, the Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) in particular drove referendums. It plays a role that the ÖDP has its strongholds in Bavaria, where direct democracy is more firmly anchored in the political system than in other federal states. The ÖDP uses direct democratic procedures as instruments of the extra-parliamentary opposition . So she initiated for example in 1996 and 1997, the popular initiative "Lean State without the Senate" that caused the dissolution of the Bavarian Senate of the year 1999/2000, 1998 and 2010, the successful referendum "For real Non smoking protection" . Some small and splinter parties have made the introduction of direct democratic elements one of their central themes. These include the Sarazzi party - for referendums , the independents ... for citizen-oriented democracy , active democracy direct , the direct democracy initiative , the party of reason , the right-wing populist party Die Freiheit , the national-conservative party from now ... democracy through referendum or the electoral association for Referendums .

Developments in Politics and Law

The prevailing opinion in jurisprudence until the 1980s was that the Basic Law forbade direct democratic elements at the federal level beyond the scope of Art. 29 , Art. 118 and Art. 146 and that these were in principle not compatible with the Basic Law and the representative system of the Federal Republic . A normative content of the provision of the Basic Law that the people exercise state power “in elections and votes” was denied. The leading constitutional lawyer Theodor Maunz commented, with a view to constitutional reality , that the words chosen in Art. 20 GG “[... correspond] more to a traditional formulation than to the current constitutional situation”.

In political science and political philosophy , party criticism began to increase in the 1960s . However, direct democracy only slowly came into focus. So put Karl Jaspers , the introduction of direct democratic elements in the Basic Law, although for discussion, but remained reserved on the issue.

With the presentations by Thomas Oppermann and Hans Meyer at the German Constitutional Law Teachers Conference of 1974, the discussion received a new impetus. In order to compensate for the deficits of party democracy, they proposed a reform package, which also included the incorporation of popular legislation into the Basic Law. However, only a few constitutional lawyers like Christian Pestalozza continued to have a positive relationship with direct democracy.

With the constitutional discussion in the course of reunification and parallel to the actual increase in the importance of direct democracy, there has been a significant increase in scientific publication activity since the early 1990s. At the same time, there was a change of heart among constitutional lawyers and political scientists . As early as 1992, in the public hearing of the Joint Constitutional Commission, all but one of the experts spoke out in favor of at least a cautious plebiscitary opening of the Basic Law.

European integration and the debate about nationwide referendums

The European level in Germany therefore contributed to the increased awareness of the population for nationwide referendums, because far-reaching integration decisions such as the Maastricht , Nice and Lisbon treaties or the treaty on a constitution for Europe triggered referendums in several states. In Germany, the CSU, the FDP, the Left and the AfD in particular advocate referendums in the event of the cession of essential sovereign rights of the Federal Republic of Germany to the EU. In principle, this position is represented by all established German parties, with the exception of the CDU. With the exception of the CDU, the NPD and a few small parties, most of the parties running for the 2014 European elections in Germany called for the introduction of EU-wide joint referendums.

In September 2000, the responsible EU commissioner , Günter Verheugen , brought referendums to the table for the eastward expansion of the EU . Germany must not repeat the mistake that it made with the euro , which it "introduced behind the back of the population".

Although the European Citizens' Initiative stands between a mass petition and a popular initiative, it has been welcomed by proponents of direct democracy as an important step towards more citizen participation and a reduction in the European Union's democratic deficit.

Organizations and campaigns for direct democracy

For the civil rights organization Humanist Union , founded in 1961, one of its most important goals is the introduction of more direct democracy. In 1971 Joseph Beuys founded the organization for direct democracy through referendum . In 1986, the Green politicians Lukas Beckmann and Gerald Häfner initiated the “referendum against nuclear facilities” campaign, which was signed by more than 580,000 people. The omnibus for direct democracy has been driving through the Federal Republic of Germany since 1987 in order to promote the debate about nationwide referendums based on the Swiss model.

In 1988 the interest group Mehr Demokratie e. V. founded. Almost all direct democratic initiatives and campaigns, as well as most petitions at the state level, which are intended to strengthen plebiscitary instruments, originate from him. The association collected 1.1 million signatures for nationwide referendums and handed them over to the Joint Constitutional Commission in 1993 . During the election campaign for the 2013 federal election, the association collected more than 100,000 signatures for the introduction of the nationwide referendum.

In June and October 1990 the Foundation for Participation in the Evangelical Academy Hofgeismar organized a technical discussion on direct democracy. This resulted in the "Hofgeismarer Draft", in which the results of the debate of the 1980s were bundled and which was of decisive importance for the discussion in the federal states and which became the basis for later proposals in the Bundestag.

After the draft constitution of the Central Round Table in the GDR had played no role in the unification process, East and West German supporters of a new constitution founded the “ Board of Trustees for a Democratically Constituted Federation of German States ” in June 1990 . Their draft constitution, presented in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt in July 1991, contained a three-stage national legislative process. A broad public could not be mobilized for a debate on the reconstitution of the Federal Republic through a referendum on a new constitution. However, the draft played a role in the constitutional committees of the federal states and in the negotiations on a constitutional reform.

The internationally oriented non-governmental organization Democracy International , based in Cologne, has set itself the goal of strengthening direct democracy and citizen participation worldwide.

Survey results

In surveys as early as the 1970s, around half of those questioned were in favor of the possibility of nationwide referendums, and approval has increased significantly since then. This development is associated with a decline in approval of other institutions for political decision-making, in particular with growing skepticism towards the parties and the “ party state ”. In East Germany, however, as general dissatisfaction with parliamentary democracy increased, so did the desire for direct democratic instruments until 2000, after which it rose sharply again.

| Polls: referendums at federal level? | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| survey | Result | Proponents by party preference | ||||||||||

| date | Institute | Yes | No |

CDU / CSU |

SPD | Green | left | FDP | AfD | Pirates | Others | No answer / non-voter |

| April 2017 | Infratest | 72% | 24% | 64% | 68% | 64% | 85% | 64% | 83% | - | ||

| October 2016 | Infratest | 71% | 26% | 59% | 61% | 62% | 85% | 73% | 81% | - | - | 85% |

| October 2016 | YouGov | 75% | 15% | 75% | 82% | |||||||

| January 2015 | Forsa | 72% | 23% | 87% | ||||||||

| November 2013 | Emnid | 84% | 13% | 83% | 88% | 83% | 95% | 78% | - | - | - | 81% |

| March 2013 | Emnid | 87% | 11% | 88% | 91% | 82% | - | - | - | - | 97% | 85% |

| February 2013 | Infratest | 66% | 12% | |||||||||

| January 2012 | Forsa | 74% | 26% | 66% | 71% | 79% | 85% | 66% | - | - | - | |

| November 2011 | Infratest | 74% | 26% | 60% | 72% | 82% | 90% | - | - | 83% | - | - |

| July 2010 | Infratest | 76% | 21% | |||||||||

| July 2010 | Forsa | 61% | 34% | 47% | 64% | 63% | 85% | 55% | - | - | - | |

| June 2009 | Forsa | 68% | 26% | 65% | 63% | 66% | 72% | 55% | - | - | - | |

| April 2004 | Forsa | 84% | 13% | |||||||||

| April 2002 | Emnid | > 80% | ||||||||||

| 2000 | 51% (west) 47% (east) |

|||||||||||

| 1993 | 60% (west) 66% (east) |

|||||||||||

| 1990 | 56% (west) 62% (east) |

|||||||||||

| August 1986 | infas | > 50% | ||||||||||

| 1973 | > 60% | |||||||||||

See also

literature

- Frank Decker : Governing in the party state . VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-531-17681-9 , pp. 165-216.

- Hermann K. Heussner, Otmar Jung (ed.): Dare to dare more direct democracy. Referendum and referendum: history - practice - proposals. 2nd Edition. Olzog, Munich 2009, ISBN 3-7892-8252-9 .

- Otmar Jung: Basic Law and referendum. Reasons and scope of the decisions of the Parliamentary Council against forms of direct democracy . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1994, ISBN 3-531-12638-5 .

- Andreas Kost: Direct Democracy . Springer, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 3-531-15190-8 .

- Andreas Kost (ed.): Direct democracy in the German countries. An introduction . VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14251-8 .

- Frank Rehmet: Referendum report 2019 . (PDF; 25 kB) Published by Mehr Demokratie e. V., Berlin 2019.

- Frank Rehmet u. a .: Citizens' initiative report 2018 . (PDF) Ed. By Mehr Demokratie e. V. in cooperation with the Research Center Citizen Participation, University of Wuppertal and the Research Center Citizen Participation and Direct Democracy, University of Marburg. Berlin 2018.

- Frank Rehmet, Tim Weber: 2016 referendum ranking . (PDF); 11 kB Published by Mehr Demokratie e. V., Berlin 2016.

- Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Legal bases and legal reality of direct democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany and its countries . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 3-8329-3350-6 .

- Theo Schiller, Volker Mittendorf (ed.): Direct democracy. Research and Perspectives . Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-531-13852-9 .

- Christopher Schwieger: People's legislation in Germany. The academic handling of plebiscitary legislation at the Reich and federal level in the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich and the Federal Republic of Germany (1919–2002) . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11518-X (also dissertation University of Tübingen).

- Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct Democratic Elements in German Constitutional History. Berliner Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8305-1210-4 .

Web links

- More democracy e. V.

- Research center for citizen participation and direct democracy at the Philipps University of Marburg

- Research center for citizen participation at the Bergische Universität Wuppertal

- German Institute for Direct Material Democracy at the Technical University of Dresden

- Database of petitions and referendums

- Omnibus for direct democracy

- Wolf Schünemann: Justified Skepticism or Exaggerated Caution? The direct democratic reluctance of the Basic Law on YouTube , accessed on June 23, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 36 f.

- ^ A b Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Theo Schiller: Direct Democracy. Frankfurt / Main 2002, p. 28.

- ^ Andreas Kost: Direct Democracy. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Article 73 ff. Of the Weimar Constitution on wikisource.

- ↑ Law on the referendum of June 27, 1921 .

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, pp. 133-135.

- ^ A b c d Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 134 f.

- ^ Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 182.

- ^ Law on referendum of July 14, 1933 ; Christopher Schwieger: People's legislation in Germany. Berlin 2005, p. 202 ff.

- ^ Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Christopher Schwieger: People's legislation in Germany. Berlin 2005, p. 333.

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 162 f.

- ^ Christopher Schwieger: People's legislation in Germany. Berlin 2005, p. 218.

- ↑ Martin Broszat, Hermann Weber (ed.): Documentation. Referendum in Saxony June 30, 1946. In: SBZ-Handbuch. Munich 1993, p. 395.

- ↑ Constitution of the GDR of April 6, 1968 , Art. 3 Paragraph 3 and Art. 87 Paragraph 1.

- ^ Constitution of the GDR of April 6, 1968 , Article 83, Paragraph 3.

- ^ Constitution of the GDR of April 6, 1968 , Art. 56, Paragraph 2.

- ^ Constitution of the State of Thuringia of December 20, 1946 , Art. 3, Paragraph 2.

- ^ Constitution for the Mark Brandenburg of February 6, 1947 , Art. 2, Paragraph 2; Constitution of the State of Mecklenburg of January 16, 1947 , Art. 2; Constitution of the State of Saxony of February 28, 1947 , Art. 2 Paragraph 2; Constitution of the Province of Saxony-Anhalt of January 10, 1947 , Art. 2 Para. 2.

- ^ Bernhard Vogel, Dieter Nohlen, Rainer-Olaf Schultze: Elections in Germany. Berlin 1971, p. 282.

- ^ Constitution of the German Democratic Republic of April 6, 1968 , Article 53.

- ^ German Democratic Republic, June 5, 1951: Against remilitarization, for peace treaty 1951 , database and search engine for direct democracy.

- ↑ a b Federal Republic of Germany, ??. May 1951: Against remilitarization, for peace treaty 1951 , database and search engine for direct democracy.

- ^ German Democratic Republic, June 29, 1954: Peace Treaty / European Defense Community , database and search engine for direct democracy.

- ^ A b Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 214.

- ↑ Draft of a constitution of the German Democratic Republic , Art. 98, Working Group New Constitution of the GDR of the Round Table, Berlin, April 1990.

- ↑ a b Theo Schiller, Volker Mittendorf: New Developments in Direct Democracy. In: Direct Democracy. Edited by Theo Schiller and Volker Mittendorf, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Frank Decker : Governing in the party federal state. Wiesbaden 2011, p. 188.

- ↑ Reinhard Schiffers: "Weimar Experiences": Still an orientation aid today? In: Direct Democracy. Edited by Theo Schiller et al. Volker Mittendorf, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 74 f .; Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct Democratic Elements in German Constitutional History. Berlin 2006, p. 192; Frank Decker: Governing in the party state. Wiesbaden 2011, p. 186.

- ↑ Reinhard Schiffers: "Weimar Experiences": Still an orientation aid today? In: Direct Democracy. Edited by Theo Schiller et al. Volker Mittendorf, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 74 f.

- ^ Otmar Jung: Basic Law and Referendum. Opladen 1994, p. 329 f .; Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 209 ff.

- ↑ Gunther Jürgens, Frank Rehmet: Direct Democracy in the provinces. In: Dare more direct democracy. Edited by Hermann K. Heussner a. Otmar Jung, Munich 1999, p. 210 f.

- ^ Andreas Kost: Direct democracy at the local level. In: Andreas Kost, Hans-Georg Wehling (Hrsg.): Local politics in the German states. 2nd Edition. Wiesbaden 2010, p. 393.

- ^ Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 260.

- ^ Johannes Rux: Direct Democracy in Germany. Baden-Baden 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Hanns-Jürgen Wiegand: Direct democratic elements in the German constitutional history. Berlin 2006, p. 243.

- ^ Christopher Schwieger: People's legislation in Germany. Berlin 2005, p. 316.

- ↑ Bernhard Gebauer (ed.), Analyzes and documents on the discussion with the NPD, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 1969, p. 17.

- ^ Eckhard Jesse : Democracy in Germany. Edited by Uwe Backes and Alexander Gallus, Cologne a. a. 2008, p. 290.