Flight and expulsion of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe 1945–1950

The flight and expulsion of Germans from the German eastern regions and from East Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe during and after the end of the Second World War from 1945 to 1950 includes flight , expulsion and the forced emigration of large parts of the German-speaking population groups resident there. It affected 12 to 14 million Germans in the eastern regions of the German Reich and German-speaking residents from East Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. It was a consequence of the National Socialist tyranny and war crimes in East Central Europe and Southeast Europe during the Nazi era and the territorial loss of the German Reich, which the victorious powers ( USA , Soviet Union , Great Britain ) determined at the Potsdam Conference in 1945.

history

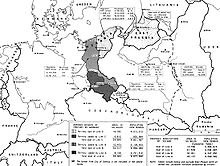

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Josef Stalin pushed through the separation of the eastern Polish territories , which had been occupied by the Soviets between 1939 and 1941 , to the Soviet Union . Eastern Poland became Polish in the wake of the Riga Peace Treaty in 1921. The area belonged to "Old Poland" until 1793 . With the secret Polish-Soviet treaty of July 27, 1944 (signed with the Lublin Committee ), the Soviet government recognized that “the border between Poland and Germany on a line west of Swinoujscie to the Oder, with Szczecin remaining on the Polish side, continues The course of the Oder up to the confluence of the Neisse and from here on the Neisse to the Czechoslovak border is to be determined ”; The second border treaty of August 16, 1945 with the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity also contained this stipulation. A common assumption is that the surrender of the eastern territories of the German Reich to Poland was intended from the beginning to compensate for the loss in the east. But this declaration only later became part of the Soviet rationale. The Polish territories were heterogeneous ethnic, while in the big cities like Lemberg (Lvov) and Vilnius (Wilno) dominated the Poles, in the countryside except in the area around Vilnius Belarusians and Ukrainians . Poles, Belarusians and Ukrainians made up the largest ethnic groups , with the Poles around Vilnius, the Belarusians between Njemen (Memel) and Pripet, and the Ukrainians south of the Pripet in the majority.

In fact, since 1939, Polish communists have been claiming German territories without a significant proportion of ethnic Poles and demanding the removal of Germans from these areas.

The bourgeois Polish government- in- exile in London laid claim to parts of East Prussia and Silesia in which there was a Polish minority. The claim for a Oder-Neisse line had a history going back to 1917 and was nourished by Stalin's promise in 1941 to Władysław Sikorski that the future western border of Poland would be the Oder. In Polish research on the West , these ideas were put on a basis of argumentation going back to the 10th century in response to German research on the East . This resulted in the establishment of the "Ministry for the Reclaimed Territories", which existed until 1949, at the end of the war .

The flight and expulsion of Germans from the countries east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse was preceded by the mass deportation and murder of Jews, Poles and Russians in the areas conquered by the Wehrmacht in World War II . Millions of people were brought to the German Reich for forced labor . Ethnic Germans from South Tyrol and Russian Germans were resettled in the conquered areas in the east of the imperial border and were supposed to form new "German settlement islands" there (see General Plan East ).

As early as the summer of 1941, the Polish and Czechoslovak governments- in- exile demanded border corrections in London after the victory over the German Reich. This should expressly include the removal of the German population from these areas and also from the rest of the state . The Polish government in exile justified its demand that the German territories should be a compensation for the loss of goods and people during the occupation, and referred to the crimes of the National Socialists in the General Government . Stalin expected that the Soviet Union, with the expulsion and expropriation of millions of Germans vis-à-vis Poland and Czechoslovakia, would be able to act as a permanent guarantee of a new status quo . With this in mind, Tsarist Russia and later the Soviet Union had already used expulsions as a means of politics in the North Caucasus . In 1944 Stalin had some hill tribes ( Balkars , Chechens , Ingush and others) deported to Central Asia.

The requested expulsion of the Germans was tried to legitimize with a reference to the behavior of the German occupiers. There were also socio-economic goals , especially in Poland . Large areas of Eastern Central Europe were then considered overpopulated.

In a legal opinion that was drawn up on behalf of the Bavarian State Government in 1991 with regard to the Sudeten Germans , the UN international law advisor Felix Ermacora came to the following conclusion: “The expulsion of the Sudeten Germans from their ancestral homeland from 1945 to 1947 and the externally determined resettlement after the Second World War contradicted this not only the self-determination promised in the Atlantic Charter and then in the UN Charter , but the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans is genocide and crimes against humanity that are not statute-barred. "

Potsdam resolutions

Border issues

At the Potsdam Conference in 1945, the new state borders in East Central Europe were only temporarily established by the Allies , when the German areas on the other side of the Oder and Neisse were subordinated to Polish and Soviet administration. A “final handover” - to the Soviet Union - “subject to the final determination of the territorial questions in the peace settlement” is only explicitly mentioned for the “(Section VI.) City of Königsberg and the adjacent area”. According to the protocol, the governments of the USA and Great Britain declared that they would support the Soviet claim to the area around Koenigsberg (northern East Prussia) at an upcoming peace conference , while such a declaration in favor of Poland is not documented.

Section IX.b (Poland) stipulates that “the formerly German territories [...] including the part of East Prussia that is not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics [...], and including the area of the former Free City of Danzig come under the administration of the Polish state and in this respect should not be regarded as part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany " , whereby " the final determination of Poland's western border is to be postponed until the peace conference " .

A few weeks earlier, the Soviet Union had transferred administrative sovereignty over these areas to Poland.

In the communication on the Tripartite Conference in Berlin, they are clearly distinguished from the four zones of occupation , which are described in Section III. as “all of Germany”, which (III.B.14.) “is to be regarded as an economic unit”. III.A.2 .: "As far as this is practically feasible, the treatment of the German population must be the same throughout Germany." This also applies to section "XIII. Proper transfer of German parts of the population ", that the" transfer of the German population or parts of the same who remained in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary "should be temporarily interrupted and" the Allied Control Council in Germany will initially address the problem with special consideration of the question of fair distribution these Germans should check the individual occupation zones ”.

The scarcity of the wording was used from the spring of 1946 to claim that the separation was not meant to be final, since the settlement of territorial issues, such as the "final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland", was reserved for a peace settlement. Attempts by the Soviet Union to regard the Potsdam resolutions as the final decision in this respect were opposed by the United States and the expulsion, which was already under way, was not accepted by the agreement.

Forced resettlement

The resettlements should be done in a "humane manner"; Francis E. Walter's report to the US House of Representatives noted that the transports were by no means in accordance with this provision. In fact, the international control meant that the forced resettlement from the beginning of 1946 took place in a much more orderly form than in the so-called wild expulsions in the weeks and months before and immediately after the conference . Nevertheless, there were numerous crimes against the German civilian population and very many deaths in internment camps and prisons.

The areas of displacement were:

- Parts of the German Empire awarded to Poland by the Allies , such as southern East Prussia , eastern Pomerania and the Neumark Brandenburg and Silesia ;

- the northern part of East Prussia, which had been added to the Soviet Union in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement and incorporated into the Russian republic ( RSFSR );

- Areas that have been denied to the German Reich since 1919, but in which Germans still lived (for example the Memelland , West Prussia , East Upper Silesia and the territory of the Free State of Danzig );

- the Baltic states (already contractually agreed in 1939/40);

- the Sudeten region , the southern Bohemian Forest and southern Bohemia and southern Moravia, i.e. the northern, southern and western peripheral areas of Czechoslovakia;

- Prague , Brno , Olomouc and German language islands (for example the Schönhengstgau with the cities of Mährisch Trübau , Zwittau and Landskron in Central Bohemia and Moravia as well as Jihlava );

- several regions in Southeastern Europe, especially in Hungary , Romania ( Transylvania , Banat ), Croatia ( Slavonia ), Serbia ( Vojvodina ) and Slovenia ( Maribor (Marburg a. d. Drau) , Ljubljana (Laibach) , Celje (Cilli) , the Gottschee ( Kočevje ), see also Yugoslavia ).

Figures on flight and displacement

Around 12 to 14 million Germans and citizens of German origin from various countries between 1944/45 and 1950 were affected by flight and displacement. Several hundred thousand people were imprisoned in camps or had to do forced labor - sometimes for years.

| area | Refugees and displaced persons | Share in the total population |

|---|---|---|

| Soviet occupation zone | 4,379,000 | 24.3% |

| American zone of occupation | 2,957,000 | 17.7% |

| British zone of occupation | 3,320,000 | 14.5% |

| French zone of occupation | 60,000 | 1.0% |

Photo taken in the occupation zones in Germany, as of December 1947.

Whether not only the people who fell victim to the crime are to be regarded as displacement victims, but also those who, for various reasons, did not survive the displacement or only survived the displacement for a few years is controversial. For a long time, around 2.1 million deaths were assumed under the influence of the IDPs . All unsolved cases were interpreted as deaths and all deaths as displacement-related. Since the basis was the mathematical difference between the statistical data from 1939 and data from 1948, this difference also included the East German Jews killed in the extermination camps . The Federation of Expellees is nevertheless continue to expect some two million dead. Some recent estimates only speak of up to 600,000 confirmed fatalities between 1944 and 1947. The Freiburg historian Rüdiger Overmans emphasizes that for reasons of conscientiousness only dead can be counted as dead, while unclear cases need to be clarified. He gives the number of deaths that were proven or at least made plausible on the basis of the registrations and investigations in the post-war period at around 500,000.

A large number of women of all ages were raped by members of the Red Army (estimates put the number at around two million).

A large part of the private property of the East and Sudeten Germans was confiscated without compensation, and German public and church property in these areas was also expropriated. In addition to the 14 million refugees and displaced persons, there were more than four million German or German-born repatriates , especially from the late 1950s .

In 1950 the Federal Statistical Office determined a total of around twelve million displaced persons in the two German states. On the basis of the difference between the resident population of the displaced areas at the end of 1944 and the displaced persons recorded in 1950, the Federal Statistical Office determined 2.2 million “unresolved cases”, which as “displacement losses” are often equated with fatalities. In 1974 the Federal Archives reported at least 600,000 confirmed deaths as a direct result of the crimes related to the displacement. The problem is that, for example, 130,000 fatalities are given for Czechoslovakia, whereas the German-Czech historians' commission cites 15,000–30,000 victims of displacement. However, these figures do not include the people who died in the immediate post-war period on the escape migrations or in the emergency shelters in Germany or during deportations to the Soviet Union due to exhaustion and exhaustion, poor hygiene, inadequate nutrition or insufficient heating material. The question of the extent to which these fatalities should be included in the total number of people who have been displaced is controversial. While the Berlin historian Ingo Haar, for example, accuses the Association of Expellees of deliberately arguing with excessive numbers of victims, Overmans criticizes on the one hand the political instrumentalization of the numbers and on the other hand the fact that the experts have so far avoided the discussion of numbers.

Escape and expulsion from Czechoslovakia

Resettlement of the displacement areas

Poland

In the areas of post-war Poland abandoned by Germans, Poles who were also resettled from the former eastern Poland (the Vilnius region , which has been in Lithuania since 1945 ), the western third of today's Belarus and western Ukraine ( Volhynia and Galicia ) were settled. Some of these approximately 1.2 million Poles, who were now forcibly resettled, only settled there after the First World War . However, the number of newcomers to the areas that had now fallen to Poland was lower than the German population displaced from there.

Most of the new settlers in the Oder-Neisse areas were Poles from the traditionally Polish areas (“Central Poland”). There were also around 400,000 Ukrainians and not too many Belarusians. The reason for this was that there has always been a significant Belarusian and Ukrainian minority west of today's Polish eastern border, especially in the regions of Białystok (Belarusians) and Przemyśl (Ukrainians). After 1945, the Polish government regarded these groups as potentially unreliable or as possible arguments for new Soviet demands on Poland. Because of this, some of them were forcibly resettled to the east (i.e. from today's Polish area to the areas east of the Bug River that belonged to Poland in the interwar period ), while others were relocated to the west, especially to Lower Silesia and Western Pomerania. This forced resettlement within Poland lasted from the end of April to the end of July 1947, and the politicians and military officials in charge called it “ Aktion Weichsel ”.

In addition to the Polish, Ukrainian and Belarusian new settlers, there were tens of thousands of Polish forced laborers from eastern Poland who had become homeless after 1944/45 due to the displacement of their homeland to the west and who now had to settle in regions that were foreign to them.

Today , almost exclusively Belarusians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Russians live in these somewhat sparsely populated areas after the mass extermination of the Jewish population and the forced relocation of most of the Poles, who often made up the upper class there. A larger Polish minority still lives in the area around Vilnius.

Soviet Union

In the Russian Soviet republic fallen Kaliningrad (until 1945 northern East Prussia with Koenigsberg ) Russians were primarily, but also settled Belarusians and Ukrainians. There were also former soldiers as well as prisoners and forced laborers . The area became a restricted military area, which even Soviet citizens could only enter with a special permit. Around 50 percent of the places were not repopulated. The southern part of East Prussia was placed under Polish administration.

Czechoslovakia

In the Sudeten area, mainly Czechs from the interior, Slovaks , Hungarians , Greek civil war refugees and a large number of Roma from Slovakia were settled. In addition, there were Czechs known as “repatriates” who came from families who had previously emigrated to France , the USA or other countries. Especially after the Roma settled in the border areas, many social conflicts arose , which worsened especially after the Velvet Revolution .

Motives for displacement

The expulsions of Germans from the east had several causes:

- Before the Second World War, German ethnic groups in these states allowed themselves to be instrumentalized for National Socialist purposes; they were ultimately organized entirely according to the Führer principle . The Sudeten German Party , Konrad Henlein operational separatist policy; in addition, Sudeten Germans received Reich citizenship in 1938 .

- The National Socialist expansion, robbery and extermination policy during the Second World War massively destroyed the relations between the German ethnic groups and the respective majority population in Central and Eastern Europe . Partisan groups soon began to act against the German occupiers in the peoples, some of which were viewed and treated as “ sub-humans ” or as people of lower rank by the German “Herrenmenschen” ; the Nazi power apparatus reacted with the most brutal severity, often against completely bystanders. In the Eastern and South-Eastern European countries, the German ethnic groups took on occupation duties. The Czechoslovak government in exile therefore received the Allies' approval for the expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia during the war .

- The expulsion of Germans from what is now Poland's western territories is related to the so-called westward displacement of Poland , the forced resettlement of Poles ordered by Stalin from the areas of eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945 , which made up 43 percent of Polish territory in the period between the two world wars. Some of these areas only became part of Poland, which was re-established in 1918, as a result of the Polish-Soviet War . Many of the ethnic Poles who settled in the new Polish western areas from 1945 came from these areas.

- For some of the Eastern and Central European governments, which often governed within the framework of a party alliance called the “National Front” or “Popular Front”, in which the Communists could set the tone even without a majority, the expulsion of the Germans was a stabilizing and motivating factor. The anti-communism of German voters would have made it much more difficult to implement the “people's democracy” according to Moscow's plans. The Soviet protective power was now also needed to protect itself from the revanchism of the expelled Germans.

- The property of displaced persons was mostly looted “spontaneously” and / or ultimately confiscated without compensation. As the example of Czechoslovakia shows, politicians who decided on the distribution of this wealth were able to gain competitive advantages for their parties.

- With the expulsion of the Germans, some post-war governments also created nationally largely homogeneous states, following on from older, by no means only communist, ideas of ethnic homogeneity. The aim was to get rid of as many pre-war conflicts as possible, which were based on the multinational character of these states as multiethnic states .

Admission in Germany and Austria

In 1944/45 12 to 14 million East and Sudeten Germans came to West Germany , the Soviet occupation zone and liberated Austria . In the post-war period, many fled again - from the Soviet to the American zone of occupation and the British zone of occupation . The Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic faced a seemingly insoluble challenge. As a result of the population shifts, some states and GDR districts such as Mecklenburg doubled their population. In formerly denominationally homogeneous regions with strong traditions of their own - for example Upper Bavaria and the Lüneburg Heath - large population groups now lived with a different lifestyle and a foreign denomination . With Espelkamp , Waldkraiburg , Traunreut , Geretsried , Trappenkamp , Neugablonz and other places, pure refugee communities emerged.

Humanitarian situation

The initial aim was to ensure the survival of the displaced in the face of severe shortages of food, housing and clothing. This has largely succeeded, although in the years up to around 1950 there was a significantly increased mortality rate due to malnutrition and infectious diseases . Rough calculations assume an additional mortality rate of 3 to 3.5 percent over the course of five years; it mainly affected the elderly, small children and people with health problems.

Associations and parties

In all zones of occupation , displaced persons made attempts to set up their own organizations to articulate their interests. In the Soviet Occupation Zone / GDR these organizations were suppressed by the police. Until the 1960s, however, informally organized ( word of mouth ) meetings also took place in the GDR. In the western zones and from 1949 in the Federal Republic of Germany , numerous expellees organized themselves into Landsmannschaften , which in 1957/58 united in the Association of Expellees (BdV). In the 1950s and early 1960s, the displaced were a comparatively influential interest group. Refugees and displaced persons were represented in all parties in German politics. A kind of special expellee party existed from 1950 to 1961 in the all-German bloc / Federation of Expellees and Disenfranchised (BHE). The BHE achieved 5.9 percent of the second vote in the federal elections in 1953. He was represented in Adenauer's second cabinet until 1957 with two ministers. From the mid-1960s onwards, the influence of the associations of expellees on federal politics decreased significantly. The BdV did not succeed in preventing the de facto recognition of the Oder-Neisse line as a German-Polish border by the Warsaw Treaty (1970) . Since the 1990s, almost only the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft (SL), supported by Bavaria and the CSU, has played a role as a political force in Germany .

integration

The economic and social integration of the expellees in the two German states took place in a long process. It is controversial which factors were decisive for the integration. Until the 1980s, the importance of the Burden Equalization Act in the Federal Republic and the land reform in the GDR were emphasized. Recent research, u. a. by Michael Schwartz , however, show that the general economic upswing during the 1950s due to the economic miracle in the west and the expansion of industry in the east had a significantly greater effect on the economic integration of the displaced.

There was no smooth, pain-free and harmonious integration of the refugees in either the west or east of Germany. When they arrived in the "West" they were sometimes confronted with contempt. Refugees were often called simply “Polack” because of the rolling “r” in their pronunciation. Nobody was interested in the terrible experiences of the refugees, such as abuse and rape. The problems of integration were not an issue in either part of Germany. The refugees' associations and the Federal Ministry for displaced persons, refugees and war victims were particularly concerned with the integration of displaced persons and refugees .

The historian Andreas Kossert brings in his book Kalte Heimat in the chapter German racism against German expellees examples of sayings about expellees. In particular in Schleswig-Holstein, where the population increased from around 1.59 million in 1939 to 2.65 million in 1946, numerous examples have survived. For example “Gesochse - first seasonal workers for the harvest, then forced labor and finally the refugee pack” or even “In the North Sea with dat Schiet”. The magazine Slesvigeren the Danish minority brought 1947 cartoon "Pied Piper". A flute player with the inscription "Lüdemann" can be seen on it, followed by a large number of rats (inscription: Flygtninge Embedsmänd ) to Sydsleswig ( inscription on the sign ) . By the flute player, the Social Democratic Prime Minister Hermann Lüdemann was meant.

Some of the displaced managed to pick up on earlier professions. For a large part of the displaced people, owning a home was “a social model and a symbol of recognition and 'arriving' in the post-war Federal Republic of Germany”, which contributed to lively building activity.

Cultural integration and the memory of flight and displacement are complex, like economic integration, and have been discussed among historians and journalists in recent years. Cultural integration includes the mixture of Catholicism and Protestantism and the marriages between locals and displaced persons, which already occurred in the immediate post-war period, but were often only generally accepted in the following generation.

Remembrance and processing

The memory of flight and expulsion was reflected in many areas of public life - from the naming of streets or a sponsorship assumption for places in the German eastern territories to the maintenance of dialects, customs and traditions in associations and compatriots to monuments and museums in West Germany , while in the GDR such place names were deleted and comparable activities prevented. Federal Transport Minister Hans-Christoph Seebohm initiated a corresponding naming of motorway parking lots in 1964. The memory of flight and expulsion changed several times after the Second World War in the Federal Republic and the GDR and after 1990 in the unified Germany. The developments and phases of memory are lively discussed in historical studies. According to Michael Grottendieck and other authors, the topic of flight and displacement in the GDR was a "taboo". In the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, too, the thesis is sometimes put forward that flight and displacement have been taboo or marginalized since the 1970s at the latest.

These theses of "taboo" have been contradicted many times. For example, the literary works, for example by Christa Wolf in the GDR or by Siegfried Lenz in the Federal Republic, show that the topic of flight and displacement was dealt with very well. In 2003, Karl Schlögel referred to the numerous museums and home parlors of the associations of expellees in West Germany that had continuously worked on the topic. In 2007 Christian Lotz showed how strongly the memory of flight and expulsion was politically charged by the dispute over the Oder-Neisse border and how intensively the discussions in the GDR and in the Federal Republic were intertwined. He therefore speaks of a "political memory pull" into which the memories of flight and displacement got. Jutta Faehndrich took up this thesis of the “pull of memory politics” at the beginning of 2011 and showed the political formation of memories in West Germany in an examination of homeland books of displaced persons.

The different political and scientific positions on the memory of flight and displacement have been reflected since 2000 in the dispute over a center against displacement . The intention to build such a museum is also a major point of conflict between Germany and its eastern neighbors Poland and the Czech Republic . The Flight, Expulsion, Reconciliation Foundation was established by the German government in 2008 as a memorial to commemorate the expulsion of 60–80 million people decided that were evicted in the first half of the 20th century.

The Beneš decrees , the legal basis for the expulsion, resettlement and expropriation of the Sudeten Germans, were explicitly excluded from the scope of the Lisbon Treaty in order to gain the approval of the Czech Republic. The reason for this was fears that displaced Sudeten Germans could file claims for restitution and compensation before international courts. Efforts to bring German-Czech closer together on the issue of displaced persons are still making headway: On June 3, 2010, a memorial plaque for the massacre of the German population in June 1945 was unveiled in the Postoloprty cemetery ( Postelberg ) . In December 2010 Horst Seehofer made an official visit to the Czech Republic as the first Bavarian Prime Minister since 1945.

In the Franconian town of Hof , the Bavarian Vogtland Museum deals with the issue of flight and expulsion of Germans in a differentiated manner.

Federal Expellees Act

The Federal Displaced Persons Act (long title: Act on the Affairs of Displaced Persons and Refugees ; BVFG) defines the term displaced person in Section 1 as follows:

“A displaced person is anyone who, as a German citizen or a German national, has his place of residence in the formerly under foreign administration of the German eastern areas or in the areas outside of it. ' Outside the borders of the German Reich' is the main difference to the definition of expellees ] the borders of the German Reich according to the territorial status of December 31, 1937 and lost these in connection with the events of the Second World War as a result of expulsion, in particular through expulsion or flight Has. In the case of multiple domiciles, the domicile that was decisive for the personal living conditions of the person concerned must have been lost. In particular, the domicile at which the family members lived is to be regarded as the determining residence within the meaning of sentence 2.

- Anyone who is a German citizen or a German national is also expelled

- left the areas referred to in paragraph 1 after January 30, 1933 and took up residence outside the German Reich because, for reasons of political opposition to National Socialism or for reasons of race, belief or ideology, National Socialist measures of violence were perpetrated against him or threatened him

- was resettled from areas outside of Germany on the basis of the intergovernmental agreements concluded during the Second World War or during the same period as a result of measures taken by German agencies from areas occupied by the German Wehrmacht ( resettlers ),

- after completion of the general expulsion measures before July 1, 1990 or afterwards by way of the admission procedure before January 1, 1993, the formerly under foreign administration, Gdansk , Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania , the former Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia , Hungary , Romania , Bulgaria , Yugoslavia , Albania or China , unless he resides in these areas after May 8, 1945 without having been expelled from these areas and having returned there by March 31, 1952 established ( resettlers ),

- without having had a place of residence, continuously exercising his trade or profession in the areas mentioned in paragraph 1 and had to give up this activity as a result of displacement,

- lost his place of residence in the areas mentioned in paragraph 1 in accordance with Section 10 of the Civil Code through marriage, but had retained his permanent residence there and had to give it up as a result of displacement ,

- in the areas mentioned in paragraph 1 as the child of a wife falling under number 5 according to § 11 of the Civil Code, but had a permanent residence and had to give up this as a result of displacement.

- A displaced person shall also be deemed to be anyone who, without being a German citizen or a German national, has his place of residence as the spouse of a displaced person or, in the cases of paragraph 2 No. 5, as the spouse of a German national or German national, who has permanent residence in the areas mentioned in paragraph 1 Has lost territories.

- Anyone who has stayed in the areas mentioned in paragraph 1 as a result of the effects of the war is only expelled if the circumstances indicate that they wanted to settle in these areas permanently even after the war or if they moved into these areas after December 31 Left in 1989. "

The debate on the concept of displacement since 1950

In the German-speaking area, the term mostly denotes the expulsion and flight of German-speaking populations from border areas with a non-uniform population history or isolated predominantly German-speaking areas in the former East German areas, Poland, today's Czech Republic and other states of Eastern Europe after the end of the Second World War.

The term expulsion or displaced person did not gain acceptance until the end of the 1940s and only became the official, and in certain cases legally fixed, designation of this process (displaced person ) or of those affected by it in the Federal Republic of Germany . Until then, forcibly resettled Germans were not conceptually differentiated from the totality of refugees ( see Displaced Persons ), and sometimes - as in later National Socialist parlance - referred to as "evacuees".

The use and exact meaning of the term expulsion have been controversial in Germany since the late 1980s, as the delimitation between (violent) expulsion and (non-violent) emigration has increasingly been questioned. By some politicians and publicists, the thesis was set up, the concept of expulsion denote merely a form of forced migration and come mainly as a German loan word in international research (in English expulsion or expellees ), while outside Germany otherwise rather deportees or refugees ( refugees) is spoken. Added to this is the confrontation of the Cold War, because in those nations that caused the Germans to flee and expel from 1944/1945 onwards, terms that are more trivial are chosen, such as the Czech word odsun (German: “Deportation by removal”) and the term transfer ("Transfer"). Even within Germany, the term expulsion and expellee was not always taken for granted. Indeed, initially the term “escape” and “refugee” prevailed, and in the Soviet occupation zone and in the GDR the terms “ resettlers ” or “former resettlers” and “new citizens” were used specifically . In 1950 there were about 4.3 million people there.

An independent designation of this group as “expellees” was, according to the objection, less justified by evident facts than it was owed more to the logic of legal and political expediency: On the one hand, due to their German citizenship (in the case of expellees from the former German eastern regions and from the Sudetenland) or as ethnic Germans - a different legal status than non-German deportees and refugees. On the other hand, the choice of this term offered several politically and socially desirable options: It created a distance between German deportees and those deported by the Germans - Jews, Poles, Czechs, Russians, etc. In this way, it enabled a victim discourse in the Federal Republic of Germany that led to a profound debate made more difficult by National Socialism.

Some leading representatives of the German expellees, namely the chairman of the Silesian Landsmannschaft, Herbert Hupka , and the president of the Federation of Expellees , Wenzel Jaksch (Hupka until 2000, Jaksch until his death in 1966), were Social Democrats. The SPD represented the interests of the German expellees until about 1964 in the same way as the CDU and CSU . In particular, for years the SPD was convinced that not only the expulsion itself was a crime, but that any recognition of the Oder-Neisse line as a new German-Polish border would have to be assessed as a political injustice. In this context, Willy Brandt , Herbert Wehner and Erich Ollenhauer's appeal for the Silesians' meeting in Germany in 1963 , which is often quoted later, is also related : “Renunciation is treason, who would deny it? 100 years of the SPD means 100 years of struggle for the right of peoples to self-determination . The right to a homeland can not sell off for a mess of pottage you. The SPD's policy changed from around 1965, when the new Ostpolitik was developed, should never be played behind the backs of compatriots who were expelled from their homeland or who had fled their homeland! In his government declaration of 1969, Willy Brandt openly indicated his willingness to recognize the Oder-Neisse line as the German-Polish border.

In the 1950s, the conceptual distinction between “normal” deportees and German expellees made it easier to maintain the demand for a revision of the Oder-Neisse line . The demand for this revision served not least to integrate the expellees into West German post-war politics. The aim was to prevent the expellees from turning to an even greater extent to parties in which former National Socialists gathered at the time, such as the SRP , the DP , and the All-German Bloc / Federation of Expellees and Disenfranchised.

The Federal Constitutional Court has, however, represented a different legal opinion: After the areas were east of Oder and Neisse either by the decisions of the Potsdam Conference in July / August 1945, by the Warsaw Treaty of 1970 international law effective from Germany as a whole separately. From this point of view of constitutional and international law, the 1950s and 1960s were not about German territorial claims against Poland, but rather controversial Polish territorial claims from the past against Germany.

In the GDR, on the other hand, the forcibly resettled people were referred to as resettlers , a group-specific special status in social law was given in particular in the distribution of expropriated areas during the land reform of 1946 and in the "Law for the Further Improvement of the Situation of Former Resettlers in the German Democratic Republic" of September 8th Fixed in 1950, but in contrast to the long-term law on expellees in the Federal Republic of Germany only remained relevant until the early 1950s. Furthermore, as early as 1950 in the Görlitz Agreement , the GDR recognized the Oder-Neisse Line as a "peace border" between the GDR and Poland. All parties represented in the Bundestag, with the exception of the KPD , filed for legal custody against this act and described it as "null and void".

Contemporary research differentiates between successive events of flight, displacement and forced relocation. Today some historians refer to the phenomenon referred to as forced migration . This linguistic usage is based on the formulation of the then Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker , who in his speech on the 40th anniversary of the end of the war on May 8, 1985, described the expulsion of the Germans as "forced migration".

However, in view of its anchoring in the public (not only German) consciousness - also from the point of view of the political left - it is practically impossible to completely drop the concept of displacement. It seems more desirable to classify this term in the overall context of forced relocations in the 20th century, as it has been increasingly carried out recently. Long debates about terms have the effect of pushing politically sensitive questions such as the number of murders and rapes in this event to the edge of the discussion.

In addition, the political left seems fruitful to attempt to view displacement and any form of forced migration in the context of general migration. Allegedly, a clear distinction between forced resettlement, flight and “voluntary” migration can often not be made.

On the other hand, recent studies on the integration of displaced persons allegedly show that the way in which displaced persons are treated and behaved show more parallels than differences to other migrant groups. Concrete differences, such as the demands made by the German expellees to this day to clarify the fate of several hundred thousand missing people without a trace, right of return, right of home , return of property and recognition of their fate as a crime against humanity within the meaning of the statutes of the International Court of Justice of Nuremberg , according to this point of view, should not hide the great parallels between German “forced migrants” and foreign immigrants in Germany. Nevertheless - according to this point of view - the specifics of forced migration will still have to be taken into account.

The expulsions in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo in the 1990s pushed this German discussion into the background. The belief that displacement and migration are two fundamentally different things regained the upper hand. Linked to this was the return to the concept of displacement defined at the beginning. Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder declared in his greeting on the Day of Homeland in Stuttgart on September 5, 1999: "Every act of expulsion, no matter how different the historical background may be, is a crime against humanity."

Peter Glotz quoted Roman Herzog in 2001 : “No injustice, however great it may have been, justifies other injustices. Crimes are crimes even if they have been preceded by other crimes. "

A different point of view is probably held predominantly in Polish politics. In an interview, the then opposition leader Jarosław Kaczyński , who failed in re-election and was defeated by Donald Tusk , said that “ Germany is one hundred percent to blame for its own fate as a displaced person ”.

See also

- Wounded and refugee transports across the Baltic Sea in 1945 , concerning the repatriation of Germans from areas of East and West Prussia not yet occupied by the Red Army by the Navy

- Refugee camp in Denmark 1944–1949

On issues of expropriation and displacement:

- Bierut decrees regarding the Germans in the eastern regions of the German Empire (except in the part of East Prussia annexed by Russia)

- Beneš decrees regarding the Sudeten Germans

- AVNOJ resolutions regarding the Yugoslav Germans and Yugoslav labor or internment camps

- Wolf Child (Second World War)

literature

- RM Douglas: "Correct transfer". The expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War. Translated from the English by Martin Richter. 2nd, revised edition, Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-62294-6 (Original title: Orderly and Humane. The Expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War. Yale University Pres, 2012, ISBN 978-0- 300-16660-6 ).

- Erhard Schütz , Elena Agazzi (ed.): Homecoming: A central category of the post-war period. History, literature and media. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-53379-4 , pp. 257-268.

- Dieter Blumenwitz : Flight and Expulsion. Heymanns, Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-452-20998-9 .

- Felix Ermacora : The Sudeten German Questions. Legal opinion. Langen Müller, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7844-2412-0 .

- Heike Amos: The SED's policy of expellees 1949–1989. Series of the quarterly books for contemporary history , special issue. Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59139-2 .

- Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East. Causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-596-12784-X .

- Jutta Faehndrich: A finite story. The home books of the German expellees (= visual history culture. Volume 5). Böhlau, Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20588-1 , also dissertation at the University of Erfurt 2009.

- Eva Hahn , Hans Henning Hahn : The expulsion in German memory. Legends, myths, history . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-77044-8 .

- Louis Ferdinand Helbig : The tremendous loss. Flight and Expulsion in German-Language Fiction of the Post-War Period. Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-447-02816-5 .

- Helga Hirsch : Heavy luggage. Flight and displacement as a life theme. With a foreword by Olga Tokarczuk . Edition Körber Foundation , Hamburg 2008, ISBN 3-896-84042-8 .

- Dierk Hoffmann, Marita Krauss , Michael Schwartz (eds.): Displaced persons in Germany. Interdisciplinary results and research perspectives. Munich 2000.

- Andreas Kossert : Cold home. The history of the German expellees after 1945. Siedler, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-88680-861-8 .

- Piotr Madajczyk, Paweł Popieliński (eds.): Social Engineering. Between totalitarian utopia and “piecemeal pragmatism”. Warsaw 2014 ( PDF , 3.9 MB, accessed on May 10, 2015).

- Rainer Ohliger: Human Rights Violation or Migration? To the historical place of flight and expulsion of the Germans after 1945 . In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 2 (2005), pp. 429–438.

- Steffen Prauser, Arfon Rees: The Expulsion of the “German” Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the 2nd World War. European University Institute, Florence 2004.

- Jürgen W. Schmidt (Ed.): When the homeland became a stranger ... Flight and expulsion of Germans from West Prussia. Essays and eyewitness reports (= Wissenschaftliche Schriftenreihe Geschichte. Vol. 14). Köster, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-89574-760-1 .

- Michael Schwartz: Displaced persons in double Germany. Integration and Remembrance Policy in the GDR and in the Federal Republic. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . Volume 56, 2008, pp. 101-151 ( digitized version ).

- Matthias Stickler : "East German means all German". Organization, self-image and political objectives of the German expellee associations 1949–1972. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-1896-6 .

- Alfred de Zayas : 50 theses on displacement. Inspiration Un Limited, London, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-9812110-0-9 .

- Alfred de Zayas: The nemesis of Potsdam . Herbig, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7766-2454-X .

- Walter Fr. Schleser : The citizenship of German people according to German law. In: German citizenship. 4th edition, Verlag für Standesamtwesen, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-8019-5603-2 , pp. 75-118 (with map booklet along with an overview of the number of people belonging to the German people in their former settlement areas).

- Arnold Suppan : Hitler - Benes - Tito. Conflict, war and genocide in East Central and Southeast Europe (= Internationale Geschichte / International History. Volume 1). 3 volumes. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-7001-7309-0 ; 2nd corrected edition 2014.

Web links

- Documentation from the Federal Agency for Civic Education

- Documentation by the German Historical Museum

- Federal Institute for Culture and History of Germans in Eastern Europe (BKGE)

- Foundation Flight, Expulsion, Reconciliation (SFVV) ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Expellees, refugees, prisoners of war, homeless foreigners: 1949–1952 , Federal Minister for Expellees, Bonn 1953

- Refugees and displaced persons in Ingolstadt after 1945 (Ingolstadt City Museum)

- The memory of flight and expulsion (contemporary history online from the Center for Contemporary History Potsdam, January 2004)

- Helga Hirsch : Collective Memory in Transition bpb , April 11, 2005

Individual evidence

- ↑ The largest three language groups (Poles, Ukrainians and Belarusians) together made up between 80 and 85% of the population, the rest consisted of Jews (approx. 9%), Lemks , Bojken , Hutsuls , Poleschuken, Russians (less than 1%) , Lithuanians , Czechs, Germans (up to 2%) and the like a. According to the Polish census of 1931 and Mały rocznik statystyczny 1941 (Small Statistics Yearbook 1941), London 1941.

- ^ Roland Gehrke: The Polish idea of the west up to the re-establishment of the Polish state after the end of the First World War. Genesis and justification of Polish territorial claims against Germany in the age of nationalism. Herder Institute, Marburg 2001, ISBN 3-87969-288-2 , p. 139.

- ↑ Detlef Brandes : The way to expulsion 1938-1945. Plans and decisions to “transfer” Germans from Czechoslovakia and Poland . Oldenbourg, Munich ²2005, ISBN 3-486-56731-4 , p. 177 f.

- ^ Robert Brier: The Polish "Western Thought" after the Second World War 1944–1950 . Digital Eastern Europe Library: Geschichte 3 (2003), p. 25 (PDF; 828 kB).

- ^ Communication on the Tripartite Conference in Berlin, IX.b.

- ↑ Cf. on this the statements of the American Foreign Minister George C. Marshall at the Moscow Foreign Ministers' Conference in 1947: Documents on American Foreign Relations. Vol. IX, January 1 – December 31, 1947 [1949], p. 49.

- ↑ Francis E. Walter: expellees and refugees of German ethnic origin. Report of a Special Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, HR 2nd Session, Report No. 1841. Washington, DC, March 24, 1950.

- ^ Tomáš Staněk : Internment and Forced Labor. The camp system in the Czech lands 1945–1948. From the Czech. by Eliška and Ralph Melville. With an introduction by Andreas R. Hofmann. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-56519-5 .

- ↑ Bernd Faulenbach: The expulsion of the Germans from the areas beyond the Oder and Neisse. For scientific and public discussion in Germany. In: From Politics and Contemporary History (B 51-52 / 2002; online )

- ↑ See also Federal Statistical Office: The German losses in displacement. Wiesbaden 1958.

- ↑ Johannes-Dieter Steinert: The great escape and the years after. In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (Ed.): End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review. Published on behalf of the Military History Research Office , Munich 1995, ISBN 3-492-12056-3 , p. 561.

- ↑ On the criticism of the old information at a glance: Ingo Haar, Extrapolated Ungluck , The number of German victims after the Second World War is exaggerated. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung of November 14, 2006.

- ↑ We want to dissolve the blockade that was not caused by us ( memento of April 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), Bund der Vertrieben, March 4, 2009.

- ^ Deutsches Historisches Museum: Mass exodus 1944/45 .

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The number of displacement victims needs to be researched anew. Historians doubt official figures . In: Deutschlandfunk , Kultur heute , December 6, 2006.

- ↑ Helke Sander, Barbara Johr: BeFreier and Liberated. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-596-16305-6 .

- ^ Displacement and eviction crimes, 1945–1948. Report from the Federal Archives of May 28, 1974. Archives and selected reports from experiences. Cultural Foundation of the German Displaced Persons , Bonn 1989, ISBN 3-88557-067-X .

- ^ Opinion of the German-Czech historians' commission on the expulsion losses. Prague – Munich, December 18, 1996. Printed in: Jörg K. Hoensch, Hans Lemberg (Ed.): Encounter and Conflict. Highlights from the relationship between Czechs, Slovaks and Germans 1815–1989. Essen 2001, pp. 245–247.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Interview with Ingo Haar Deutschlandfunk, November 14, 2006

- ↑ BdV: "Hair" -streaking numbers of the historian Ingo Haar ( Memento from June 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.dradio.de/dlf/sendung/kulturheute/571295/ Rüdiger Overmans: The number of displacement victims has to be researched anew. Historians doubt official figures.

- ^ A b Heike Amos: The SED's policy of expellees 1949 to 1990. Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, pp. 32–41.

- ↑ Matthias Stickler: "East German means all German". Organization, self-image and political objectives of the German expellee associations 1949–1972. Düsseldorf 2004.

- ↑ Michael Schwartz: Displaced persons in double Germany. Integration and Remembrance Policy in the GDR and in the Federal Republic. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (2008) issue 1, pp. 101–151; see. also Dierk Hoffmann, Marita Krauss, Michael Schwartz (eds.): Displaced persons in Germany. Interdisciplinary results and research perspectives. Munich 2000.

- ↑ Hilke Lorenz: Home out of the suitcase - From life after flight and expulsion. List, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-548-61006-1 .

- ↑ Patrice G. Poutros, Refuge in Post-War Germany. Politics and practice of refugee admission in the Federal Republic and GDR from the late 1940s to the amendment of the Basic Law in the United Germany from 1993 , pp. 853 ff. In: Jochen Oltmer (Ed.): Handbook State and Migration in Germany since the 17th Century , De Gruyter, 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-034539-1 . P. 877 .

- ^ Andreas Kossert: Cold home. Munich 2009, chapter “German racism against German expellees”, pp. 71–86.

- ↑ Reinhold Weber , Karl-Heinz Meier-Braun : Brief history of immigration and emigration in Baden-Württemberg , Der Kleine Buch Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-7650-1414-7 . P. 113 .

- ^ Art campaign "93 Street Signs" Polish street names in Friedrichshain . Berliner Zeitung , August 24, 2015.

- ^ [1] Warthe in the Westerwald

- ↑ Michael Grottendieck: Equalization without differentiation? Prevention of organizations of displaced persons in the context of an establishing dictatorship. In: Thomas Großbölting u. a. (Ed.): The establishment of the dictatorship. Transformation processes in the Soviet occupation zone and in the early GDR. Münster 2003, pp. 191-221.

- ↑ Michael Schwartz: Expulsion and politics of the past. An attempt on divided German post-war identities. In: Germany Archive (1997), pp. 177–195; Herbert Czaja: On the way to Germany's smallest? Marginalia on 50 years of Ostpolitik. Frankfurt am Main 1996.

- ↑ See the documents in Louis Ferdinand Helbig: The monstrous loss. Flight and Expulsion in German-Language Fiction of the Post-War Period . Wiesbaden 1988.

- ↑ Karl Schlögel: Europe is not just a word. On the debate about a center against displacement. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft (2003), Issue 1, pp. 5–12.

- ↑ Christian Lotz: The interpretation of the loss. Political memory controversies in divided Germany about flight, expulsion and the Eastern Territories (1948–1972). Cologne 2007.

- ↑ Jutta Faehndrich: A finite story. The home books of the German expellees. Cologne 2011.

- ↑ Appointment: Prime Minister Horst Seehofer's trip to the Czech Republic ( press release from the Bavarian State Government ). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 27, 2018 ; accessed on June 26, 2018 . dated December 17, 2010.

- ↑ Seehofer in the Czech Republic - friends who did not know about each other , Klaus Brill , in: Süddeutsche Zeitung of December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Speech by Peter Glotz (2001)

- ↑ Polen-Rundschau.de: Kaczynski against compromise in the matter of expulsion from January 8, 2008 ( Memento from March 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Dr. Jutta Faehndrich at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography ( Memento from February 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive )