House of Commons

| Joint logo of the upper and lower houses | Palace of Westminster |

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Seat: | Palace of Westminster |

| Legislative period : | 5 years |

| First session: | January 20, 1265 (English Parliament) January 1, 1801 (United Kingdom Parliament) |

| MPs: | 650 |

| Current legislative period | |

| Last choice: | December 12, 2019 |

| Chair: |

Speaker Lindsay Hoyle |

| House of Commons of the 58th British Parliament | |

| Distribution of seats: |

As of July 16, 2020

Government (362) 2 Deputy Speakers do not take part in votes. |

| Website | |

| www.parliament.uk | |

The House of Commons (HoC), usually called the British House of Commons in German (officially: The Honorable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland assembled in Parliament ; German: "The honorable, in Parliament assembled commoners of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ”) is the politically decisive second chamber of the British Parliament . The lower house determined by legislation and the state budget , the Government of the United Kingdom is responsible to him, and a prime minister only remains in office, as he has his support. In addition to the House of Commons, the Crown and the Upper House, the House of Lords , belong to Parliament. Both chambers meet in the Palace of Westminster .

The lower house has 650 members , the Members of Parliament ( MP ). The members of parliament are elected by relative majority in their respective constituencies, the constituencies , and remain in office until parliament is dissolved. The Fixed-Term Parliaments Act of 2011 provides a five-year term. An early dissolution of the lower house is only possible by a parliamentary resolution with a two-thirds majority or a vote of no confidence. Most of the ministers are also members of the lower house, as have all prime ministers since 1963.

De Montfort's Parliament from 1264, a council of the king, which for the first time also included bourgeois representatives, is considered the origin of today's lower house . It developed into an independent chamber of the English parliament in the 14th century from the assembly of the representatives of the mostly trading cities and has existed without interruption ever since. Initially, there were only English MPs in the lower house. Since the 16th century Welsh , since the Act of Union 1707 Scottish and since 1801 also Irish members were added. At the beginning of its history, the lower house was the least significant part of parliament. From the 17th century, however, mainly as a result of the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution , it gradually rose to become the predominant branch of the legislature . His competencies today go beyond those of the crown as well as those of the upper house. Since the Parliament Act of 1911, the House of Lords can no longer reject draft laws of the House of Commons, but can only use a suspensive veto against them.

history

Origin and development until the early 19th century

Parliament developed from the royal council , which advised the king during the Middle Ages. This advice, which always met for a short time, consisted of clerics , high nobles ( peers ) and low noble representatives of the counties ( counties ), as "knights of the county" ( Knight of the Shire ) were described. The main task of the council was to approve the taxes proposed by the crown. Often, however, the council asked for popular complaints to be resolved before it could vote on taxation. From this the legislative powers developed.

In the model parliament of 1295, representatives of the boroughs , i.e. the rural towns and cities, were also allowed. It thus became the custom for each county to send two knights (Knights of the Shire) and each town two citizens (Burgesses) . At first, the representatives of the cities were almost completely powerless. While the representation of the counties was firmly regulated, the monarch could, if he pleased, grant or withdraw voting rights to the cities. Any visible striving for independence by the citizens would have led to their city being excluded from parliament. The knights of the county were in a better position, but they too were less powerful than their aristocratic fellow MPs in the one-chamber parliament. The division of parliament into two houses happened in 1341 during the reign of Edward III. The knights and the burghers formed the lower house, while the clergy and nobles formed the upper house ( House of Lords ).

Though it remained subordinate to both the Crown and the Lords, the House of Commons acted with increasing audacity. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Peter de la Mare, complained about the oppressive tax burden, requested a listing of royal expenses and criticized the King for his leadership of the military. The House of Commons even set about removing some of the royal ministers. The brave speaker was imprisoned, but soon after the death of King Edward III. released. During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II , the House of Commons began again to depose misguided Crown Ministers. It insisted on being able to control not only taxation but also public spending. Despite these gains in authority, the House of Commons remained less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

The influence of the crown increased through the civil wars of the late 15th century, while the importance of the high nobility declined. In the years that followed, the two chambers of parliament were able to retain little authority, and the absolute supremacy of the monarch was renewed. In the 16th century, under the Tudor dynasty , the power of the crown even increased. On the other hand, King Henry VIII, at the instigation of his chief minister Thomas Cromwell , granted parliament for the first time a say in church and constitutional questions in order to achieve the separation of the English Church from Rome. From 1603, after the accession of the House of Stuart , both the absolutist aspirations of the crown and the self-confidence of the parliament continued to grow. Under the first two Stuart monarchs, James I and Charles I , the crown increasingly came into conflict with the House of Commons over taxation, religion and royal powers.

Under Charles I, these disputes took on such fundamental forms that they could only be resolved by the English Civil War . After the victory of the Parliamentary Army under Oliver Cromwell , the king was convicted of traitor and beheaded in 1649. The House of Commons abolished the Crown and House of Lords and established the English Republic for 11 years . Although in theory it was the highest state organ, Cromwell ruled as lord protector in a dictatorial manner. Therefore, it was two years in 1660, according to his death, to the restoration of the monarchy and the House of Lords. For this, King Charles II had to make concessions to the House of Commons, which his father had strictly refused to accept. His brother and successor Jacob II was declared deposed in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution . Despite continued strong powers, the subsequent kings had to be careful to conduct politics in accordance with the parliamentary majority in the lower house.

In the 18th century, the office of prime minister developed. Soon the modern view prevailed that the government would only remain in power as long as it had the support of parliament. However, the support of the House of Commons for the government only became crucial later. The custom for the Prime Minister to come from the House of Commons also developed later.

The House of Commons went through an important period of reform in the 19th century. The crown had made very irregular use of its prerogative of granting and withdrawing voting rights to cities. Furthermore, some anomalies had developed in the city councils. Thus some once important cities had slipped into insignificance, so-called rotten boroughs . Nevertheless, they had retained their right to send two representatives to the House of Commons. The most notorious example was Old Sarum , which only had 11 eligible voters. In total, there were 46 constituencies with fewer than 50 voters, 19 more with fewer than 100 voters and another 46 with fewer than 200 voters. At the same time, large cities like Manchester did not have their own representative, but their electoral residents could vote in their county, in this case Lancashire . Also, there were so-called "pocket-boroughs" (pocket boroughs) - small electoral districts, which were controlled by a few wealthy landowners and aristocrats, whose candidates were elected without exception. In this way, z. B. the respective Duke of Norfolk over eleven, the Earl of Lonsdale over nine parliamentary seats. These mandates were given to younger sons, but could also be sold or rented, e.g. B. for £ 1,000 a year.

Reform Act of 1832

The House of Commons tried to remedy these anomalies through a reform law in 1831. At first, the House of Lords was unwilling to pass the law. However, it was forced to give way when Prime Minister Charles Gray, 2nd Earl Gray advised King William IV to appoint a large number of new members to the House of Lords who were positive about the law. Before the king could take action, however, the Lords passed the Act of 1832. The Reform Act of 1832 deprived the crumbling cities of voting rights, created uniform electoral conditions in all cities, and gave large-population cities adequate representation. However, it preserved many of the pocket-sized boroughs . In the following years, the lower house increasingly claimed decision-making powers, while the influence of the upper house had suffered from the crisis in the course of the reform law. The power of the cartridge in the pocket boroughs had also declined. The lords were now more and more reluctant to reject laws that had been passed by large majorities in the House of Commons. It also became a generally accepted political practice that the support of the House of Commons was sufficient for the Prime Minister to remain in office.

Many other reforms were introduced during the second half of the 19th century. The Reform Act of 1867 lowered the property threshold at which someone was eligible to vote in the cities, reduced the number of representatives from the less populated cities and granted new parliamentary seats to several emerging industrial cities. The electorate was expanded by the People's Representation Act of 1884, lowering the property threshold required for electoral law in the counties. The seat redistribution law of the following year replaced almost all constituencies with several representatives with constituencies with only one representative.

Parliament Act of 1911

The next important phase in the history of the House of Commons came in the early 20th century. The Liberal government, led by Herbert Henry Asquith , introduced a series of social welfare programs in 1908. Together with the costly arms race with Germany , the government was therefore forced to increase its income through tax increases. That is why the Treasury Secretary, David Lloyd George, presented a so-called “people's budget” in 1909, which provided for higher taxes for wealthy landowners. However, this unpopular measure was rejected in the predominantly conservative House of Lords.

In the election campaign for the January 15 / February 10, 1910 election, the Liberals made the powers of the House of Lords their most important campaign issue and thus achieved their re-election. Asquith then suggested that the powers of the House of Lords be severely restricted. The legislative process was briefly interrupted by the death of King Edward VII in May 1910; It was soon under George V continued. After the general election in December 1910 , the Asquith government was able to pass the law that curtailed the powers of the House of Lords. The Prime Minister, with the monarch's approval, suggested that the House of Lords could be flooded with the creation of 500 Liberal Peers if it refused to pass the law. The same measure had already enabled the Reform Act of 1832 to be passed. The Parliamentary Act of 1911 came into force soon afterwards, removing the legislative equality of the two houses of parliament. The House of Lords was now only allowed to postpone most legislative acts for a maximum of three parliamentary sessions, or for a maximum of two years. With the Parliament Act of 1949 this was restricted to either two parliamentary sessions or a maximum of one year. With the passage of these laws, the lower house has become the more powerful chamber of parliament.

Originally, the MPs received no income for their office. Most of those elected to the House of Commons had private income, while a few depended on financial support from wealthy patrons. Early Labor MPs often drew union revenue, but this was banned by a 1910 House of Lords decision. As a consequence, a clause was inserted in the Parliamentary Act of 1911 that introduced diets for MPs. Government ministers had previously been paid.

MPs and elections

Each MP represents a single constituency. Before the reforms of the 19th century, there was little correlation between constituencies and the distribution of the population. The counties and cities with their defined boundaries were largely equally represented in the lower house by two representatives each. The reforms of the 19th century resulted in a more even distribution of seats. This began with the Reform Act of 1832. The reforms of 1885 replaced most constituencies with two MPs with those with only one MP. The last constituencies with two MPs were converted in 1948. The university constituencies , which had given the major universities of Oxford and Cambridge their own representation in parliament, were also abolished in the same year. Since then, each constituency has only elected one member of the lower house.

Division of constituencies

The number of constituencies to which each of the four regions of the UK is entitled is a function of the number of voters. There are certain requirements to be considered: Northern Ireland must have 16 to 18 constituencies. Wales is required by law to have at least 35 MPs in parliament. For the islands ( Isle of Wight , Scottish Isles, etc.) there are special rules regarding the size of the constituencies.

Constituency boundaries are set by four permanent and independent Boundary Commissions , one each for England , Wales , Scotland and Northern Ireland . The commissions regularly review the number of eligible voters in the constituencies and propose changes to the constituency boundaries in line with the development of these numbers. When setting out the constituency boundaries, the border commissions take into account u. a. local administrative boundaries. Your proposals are subject to Parliament's approval, but cannot be modified by Parliament itself.

The stipulation is to delimit the constituencies in such a way that the number of eligible voters in the upcoming election does not deviate by more than 5% from the arithmetic mean . In 2016 there were 74,769 eligible voters per constituency, i.e. In other words, there should be no less than 71,031 eligible voters and no more than 78,507 per constituency. We are still a long way from achieving this goal. In 2015, there were major deviations from the ideal of having the same number of eligible voters as possible in the constituencies: As of December 1, 2015, the constituency of Arfon in Wales had only 38,083 eligible voters. In 2015, however, there were more than 91,000 eligible voters in the two largest constituencies (Ilford South and Bristol West).

The United Kingdom is divided into 650 constituencies (as of 2016), of which 533 are in England, 40 in Wales, 59 in Scotland and 18 in Northern Ireland. The House of Commons decided to reduce the number of constituencies to 600 by the next election.

Election date and implementation of the election

Until 2011, the Prime Minister was allowed to choose the time of the dissolution of parliament and thus the time for new elections within a period of 5 years, unless he was forced to do so by a failed vote of confidence. The Tories-Liberal Democrats government under Prime Minister Cameron changed this with the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act. Since then there has been a fixed election date. This should be, if possible, 5 years after the last election date, on the first Thursday in May. The prime minister can, however, introduce a proposal to parliament that he wants to dissolve parliament; if this is accepted, new elections take place. There will also be new elections if the House no longer has confidence in the government (no confidence in Her Majesty's Government).

Each candidate must submit application documents signed by 10 registered voters from their constituency. He is also required to deposit £ 500 , which is only paid back if the candidate receives at least 5% of the votes in his constituency. This bail is intended to prevent joke candidates. One MP from each constituency is sent to the House of Commons. According to the principle of majority voting, the winner is the candidate who has the most votes in his constituency. The votes of the losing candidates are no longer taken into account. Minors, members of the House of Lords, prisoners and persons incapable of doing business are not eligible to vote . To vote, one must be a resident of the United Kingdom, a UK overseas territory , the Republic of Ireland or a member of the Commonwealth of Nations . British citizens living abroad are also eligible to vote for up to 15 years after leaving the UK. No voter is allowed to vote in more than one constituency.

Term of office of the MPs

After the election, the MP regularly serves until the next dissolution of parliament (or until his death). If an MP loses the following qualifications, his seat will become vacant. There is also the option for the House of Commons to expel MPs. However, this option is only used in rare exceptional cases, such as serious misconduct or criminal activities. In such cases, a vacancy can be eliminated by a by-election in the relevant constituency. The same electoral system is used as in the general election.

The term “Member of Parliament” only refers to members of the House of Commons, although members of the House of Lords are also part of Parliament. Members of the 'House of Commons' may add the abbreviation MP ( Member of Parliament ) after their name .

Income of the MPs

The annual salary of each MP has been £ 79,468 as of April 2019. This is the equivalent of around 95,000 euros annually (or just under 8,000 euros per month). In addition, there may be additional salaries for offices that they hold in addition to their mandate, e.g. B. for the office of Speaker (President of Parliament). Most MPs receive between £ 100,000 and £ 150,000 for various expenses (staff costs, postage, travel expenses, etc.) and for maintaining a second home in London if they live elsewhere.

eligibility

There are a number of requirements that candidates must meet for a seat in parliament. Most importantly, an MP must be over the age of 18 and be a citizen of the United Kingdom, a British Overseas Territory, the Republic of Ireland or another Commonwealth of Nations. These restrictions were the British Nationality Act of 1981 (the British Nationality Act) committed. Before that, the conditions were even stricter: According to the Act of Settlement of 1701, only those who had become British citizens at birth were allowed to run for office. Members of the House of Lords were not allowed to become members of the House of Commons.

MPs are expelled from the House of Commons if they are subject to personal bankruptcy restrictions (Bankruptcy Restrictions Order) . This applies to MPs from England and Wales. Northern Irish MPs will be expelled if declared bankrupt and Scottish MPs if their property is subject to foreclosure. The mentally ill are also banned from sitting in the House of Commons. Under the Mental Health Act of 1959, two specialists must explain to the Speaker of the House of Commons that the MP concerned has a mental illness before their mandate can be declared vacant. There is also an 18th century common law precedent that the "deaf and dumb" are not allowed to sit in the House of Commons. However, this precedent has not been ruled on in recent years and it seems highly unlikely that it would be upheld by the courts in a hypothetical decision.

Anyone found guilty of high treason may not belong to Parliament until the sentence has been served in full or until he has been fully pardoned by the Crown. Anyone serving a prison sentence of one year or longer is also ineligible. Finally, those who are guilty of certain election-related crimes against the Representation of the People Act 1983 are not allowed to stand for 10 years . There are also other disqualification conditions in the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975. Also holders of high offices in the judiciary, members of the civil service, professional soldiers and members of foreign legislative bodies (with the exception of those of Ireland or the Commonwealth of States), as well as the holders of various crown offices are not eligible to run for the House of Commons. The law largely summarized legal regulations that had already been adopted. Several crown officials have been excluded since the Act of Settlement of 1707. Although ministers are also paid officials of the Crown, they are allowed to exercise their parliamentary mandate.

The rule of excluding certain Crown Officials from serving in the House of Commons was introduced to circumvent another House of Commons decision of 1623 that would not allow MPs to resign. If a member of parliament should now feel the desire to resign, he can apply for appointment to one of two crown offices. These are the offices of Crown Administrator and Bailiff of the Chiltern Hundreds Estate and Crown Administrator and Bailiff of the Manor of Northstead . The Chancellor of the Exchequer is responsible for the appointment and is bound by tradition never to refuse such a request.

organization

Offices

The House of Commons elects a chairman, known as a speaker , at the beginning of each legislative period . If the incumbent is running from the previous legislative period, the House of Commons can re-elect him with a majority by passing a simple motion. As a rule, the major parties do not put up any opposing candidates against an incumbent parliamentary speaker in the general election. New candidates are elected by secret ballot . A designated speaker takes office after obtaining the purely formal approval of the monarch. The Speaker of the House of Commons is supported by three deputies. The highest ranking deputy is the Chairman of Ways and Means . The other two deputies are named first and second deputy chairman of the means and ways. These official titles are derived from the Committee of Means and Ways and were an organ that the chairman once headed. Although the committee was abolished in 1967, the traditional titles were retained. The Speaker of the House of Commons and the Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons are always members of the House of Commons.

While the Speaker of the House of Commons presides over the meetings, he wears a ceremonial black robe. He can also wear a wig. However, this tradition has not continued since the tenure of House Speaker Betty Boothroyd . The Speaker of the House of Commons or his deputy chairs the meeting from a raised chair at the front of the meeting room.

The speaker is also the chairman of the House of Commons Commission, which is responsible for managing the House of Commons. He continues to control the meetings by bringing up items on the agenda, giving the floor and chairing votes. If a member of parliament is of the opinion that a rule of the rules of procedure has been violated, he can complain to the Speaker of the House of Commons. Thereupon a binding decision of the speaker is issued, which cannot be appealed.

The Speaker of the House of Commons can discipline MPs who violate the Rules of Procedure. Thus the Speaker of the House of Commons is far more powerful than his counterpart in the House of Lords, the Lord Speaker . The latter has no disciplinary power at all. Usually the Speaker of the House of Commons and his deputies exercise their office in a non-partisan manner. They quit their party and do not take a position on political issues. If the spokesman tries to be re-elected, he will not campaign and the other larger parties will usually not run against candidates in his constituency. Even after leaving the House of Commons, it is customary to remain non-partisan and not comment on political issues. The Clerk of the House is both the chief procedural adviser to the House of Commons and the top senior official. He is a civil servant and not a member of parliament himself. The House Secretary advises the House of Commons Speaker on House of Commons rules and procedures, signs instructions and official communiqués, and signs and supports draft laws. He is the chairman of the board of management, which consists of the department heads of the six departments of the lower house. The deputy house secretary is known as the clerk assistant . Another incumbent is the Sergeant-at-Arms , whose duties include maintaining legality, order, and security on the parliamentary grounds. The Sergeant-at-Arms wears a ceremonial mace symbolizing the authority of the Crown and the House of Commons. At the opening of each session he steps forward with this mace to the Speaker of the House of Commons as he enters the House of Commons. During the session, the mace rests on the table of the House of Commons.

Boardroom

Like the House of Lords, the House of Commons meets in the Palace of Westminster in London. The meeting room looks small and modest and is decorated in a green tone. In contrast, the Lord's Chamber is red and lavishly furnished. There are benches on either side of the chamber, divided by a central aisle. These furnishings are reminiscent of that of St. Stephen's Chapel, which was used as a conference room until it was destroyed by fire in 1834. The speaker's chair is at the head of the chamber. In front of it is the table of the house on which the ceremonial mace is placed. The secretaries (clerks) sit at the blackboard near the speaker in order to be able to advise him on procedural questions if necessary. The members of the government sit on the benches to the right of the speaker and the opposition MPs on the benches to the left of the speaker.

There is a red line on the carpet in front of the rows of benches on either side. These two red lines are two sword lengths apart. Traditionally, MPs are not allowed to cross this line during the session. This is to prevent a member of parliament from attacking the political opponent on the opposite side, possibly physical. Government ministers and key opposition leaders sit on the front benches and are known as front benchers . Other MPs are backbenchers (backbenchers) called. Not all MPs can sit in the House of Commons at the same time: there are only seats for 427 of the 650 MPs. MEPs arriving late must stand near the entrance to listen to the debates. Sessions in the Chamber of Commons take place Monday through Thursday, some also on Fridays. During times of national emergency, the House of Commons may also meet on Saturdays.

The House of Commons has sometimes met at Westminster Hall since 1999 ; this is also located in the Palace of Westminster. The debates at Westminster Hall generally deal with indisputable or bipartisan issues. Debates that later lead to votes must continue to be held in the main chamber. Sessions at Westminster Hall are held every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. They consist of a morning session and an evening session on each of these days.

Access to the meetings

Meetings of the House of Commons are public. However, the House of Commons may decide at any time by voting to exclude the public from the meeting. The traditional objection of a member of parliament who wanted a closed session was I spy strangers (“I see strangers”). This was then automatically followed by a corresponding vote. However, this tradition was abolished in 1998 as it was commonly used to delay and interrupt debates. Since then, MPs who wish to be excluded from the public have had to make a formal request. Public debates will be broadcast on radio and television as well as via live stream on the Internet. They are also recorded in writing; the protocol is called Hansard . Interested citizens can attend the debates without prior registration in the Visitors' Gallery (formerly: Strangers' Gallery ), access is via the visitors ' entrance on Cromwell Green .

Sessions of the House of Commons were often interrupted by angry protesters who tossed items into the chamber from the visitors' gallery or other galleries. Examples of such items are leaflets, manure, flour, and a canister of tear gas . Even MPs have occasionally disrupted parliamentary sessions. For example, in 1976 Tory MP Michael Heseltine grabbed the mace and brandished it during a heated debate. Probably the most famous disruption to a parliamentary debate was caused by King Charles I , who entered the chamber with a detachment of armed men in 1642 to arrest five MPs from the anti-monarchical faction. This action was seen as a serious breach of Parliament's privilege.

Since 1642 it has been a strictly observed custom that no monarch enters the lower house. Another tradition grew out of Charles I's actions: the annual opening of parliament in the Upper House Chamber, during which the monarch reads the government declaration in the presence of the members of both chambers. The Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod (a House of Lords) is responsible for calling the House of Commons into the House of Lords Chamber. As soon as he appears to deliver his call-up, the doors of the Chamber of Commons slam shut in front of him. This symbolizes the right of the House of Commons to advise without interruption. Only after the gentleman Usher has knocked on the door three times with his black baton is he allowed in.

Debates and votes

During the debates, the MPs are only allowed to speak after they have been given the floor by the speaker or the respective presiding deputy. Traditionally, the speaker alternately gives members of the government and the opposition the right to speak. Ordinarily, the prime minister, the opposition leader and other leaders of both camps are given priority over other MPs when several rise to speak at the same time. Until 1998, all was Kronräten (Privy Councilors) granted a priority; this was changed with the modernization of the procedure in 1998.

The speeches are formally addressed to the chairman, using the introduction "Mr Speaker", "Madam Speaker", "Mr Deputy Speaker" or "Madam Deputy Speaker". Only the respective chairperson may be addressed directly in the speeches. References to other MPs may only be made in the third person . Traditionally, this is not done using the name of the member of parliament, but by naming his or her constituency, e.g. B. "The Honorable Member of Parliament for (constituency)". The Speaker of the House of Commons enforces the rules; he can warn and punish MPs who deviate from the rules. Disregarding the speaker's instructions is considered a serious violation of the house rules. This can lead to the person concerned being excluded from the session, see naming (parliamentary procedure) . In the event of serious disorder, the speaker can adjourn the parliamentary session without voting.

The Standing Orders of the House of Commons do not provide for any formal time limits for the debates. The speaker can, however, withdraw the right to speak from a member of parliament who makes a tedious speech with repetitions or whose speech is irrelevant. The time allotted for debates on specific motions is often limited by informal agreements between the parties. A debate can be restricted by the adoption of a time allocation motion. Such requests are called Fallbeilanträge ( Guillotine Motions) . The House of Commons can also end a debate immediately by passing a motion to close the debate. The Speaker of the House of Commons can reject such a motion if he is of the opinion that it violates minority rights (opposition rights).

When the debate comes to an end, or when the debate has been closed, a vote is taken on the motion in question. The lower house initially votes orally (voice vote): The lower house speaker reads out the motion, and the MPs either answer “Aye” in the affirmative or “No” negatively. The chairman then announces the result. However, if the assessment of the outcome is doubted by a member of the parliament, a vote in the mutton jump procedure (division) takes place . The chairman can, however, reject the doubt if he is convinced that the voice vote is unambiguous. If a mutton jump is carried out, the deputies enter the two anterooms on the respective sides of the lower house chamber. There their names are recorded by secretaries. In each anteroom there are two reporters (plates) who are also MPs. The rapporteurs count the votes of the MEPs.

As soon as a mutton jump is over, the reporters pass the results on to the chairman, who then announces them. In the event of a tie, the chairman himself has the casting vote. The minimum number of the House of Commons for a valid vote by Hammelsprung is 40 votes. If less than 40 MPs have taken part in the mutton jump, it is invalid. If a member of parliament wanted to make a request for the restoration of order (point of order) during a mutton jump , they had to wear a certain hat. This was to indicate that his request did not relate to the ongoing debate. This custom was also discontinued in 1998.

The result of most of the votes is known in advance, as the political parties expect and demand group discipline from their MPs . In every parliamentary group there are certain members of parliament, Whips (literally: “ whips ”), who are supposed to induce the members of their own group to vote in a desired manner. Normally, MPs do not vote against the party wishes, as this would block the way to higher political offices in their parties. Deviants could also be punished by not being nominated as official party candidates in future elections in their constituencies. In severe cases, they can also be expelled directly from their parties, but this is very rarely the case. Revolts by backbenchers who are dissatisfied with the line of the party leadership are not uncommon. In some cases, parties suspend compulsory parliamentary groups ; then their MPs can vote at their own discretion. This is common when voting on questions of conscience (such as abortion or the death penalty).

Committees

The UK Parliament sets up committees for a variety of purposes. A common purpose is to review laws. Committees examine the laws in detail and can also make changes. Laws of great constitutional importance and important financial measures are usually sent to the Committee of the Whole House , a body that, as the name suggests, includes all Members of the House of Commons. Instead of the Speaker of the House of Commons, this committee is chaired by the Chairman or the Deputy Chairman of Means and Ways. This committee meets in the Chamber of the House of Commons.

Most laws are of Standing Committees (Standing Committees) processed, each consisting of 16 to 50 members. The composition of each Standing Committee roughly reflects the distribution of power between the parties throughout the House of Commons. Although "constantly" suggests permanence, membership in the standing committees changes constantly. New committee members are reassigned each time the committee works on a legislative proposal. There is no formal limit to the number of standing committees. However, there are usually no more than ten at a time. Very rarely is a law submitted to a Special Standing Committee. Such a committee behaves very similarly to an ordinary standing committee. In addition, however, it investigates more fully and holds hearings on matters affected by a law.

The House of Commons also has several Departmental Select Committees . Membership in these organs, like that in the standing committees, reflects the strength of the parliamentary group in the House of Commons. Each committee elects its own chairman. The primary function of the oversight committees is to oversee and investigate the activities of a particular government department. In order to fulfill this task, he is allowed to hold hearings and gather evidence. Laws can also be submitted to the supervisory committees, but such an approach is rarely chosen.

A separate special committee is that of the Domestic Committee . The House of Commons committee oversees the administration of the House of Commons and the services given to MPs. Other committees of the House of Commons are Joint Committees, which also include members of the House of Lords, and the Committee on Standards and Privileges, which deals with issues of parliamentary prerogatives and meets when it does about the behavior of individual MPs. There is also the Committee of Selection, which determines membership in the other committees.

Legislative functions

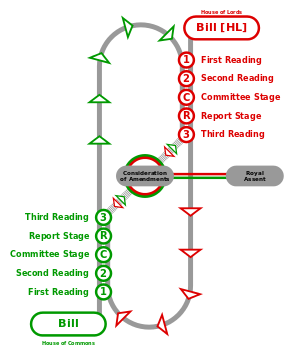

Although bills can be introduced in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, a large part of the laws originate in the House of Commons. Most of the laws are introduced by the government (government bill); those from other members of parliament are subject to strict schedules and tend to have little chance of success.

The predominant position of the House of Commons in the field of legislation by several Acts of Parliament ( Parliament Acts ) secured the monarch to grant Royal Assent to certain kinds of laws directly ( Royal Assent ) may be presented without the previous consent by the House of Lords. The Lords are not allowed to delay a money bill , which is not a bill that, in the opinion of the Speaker of the House of Commons, affects national taxation or public revenues. Furthermore, the Lords may delay most of the other laws that have been introduced in the House of Commons for no more than two parliamentary sessions or a maximum of one year. A law that aims to extend the legislative period beyond five years, however, requires the approval of the House of Lords.

Under customary law that predates parliamentary laws, the House of Commons has prerogative in all matters relating to finance. Only the House of Commons may introduce laws that affect taxation or the state budget (supply) . In addition, budget laws passed in the House of Commons are immune to amendments proposed by the House of Lords. Further, the House of Lords may not amend a law in a way that introduces taxation or a budgetary clause. However, the House of Commons often waives its rights and allows the Lords to make changes with financial implications. Under a separate agreement called the Salisbury Convention, the House of Lords does not seek to oppose legislative proposals put forward by the government in its electoral manifesto .

Relationship with the government

Although the House of Commons does not directly elect the Prime Minister, he is still indirectly controlled by the House of Commons. According to an agreement, the Prime Minister is accountable to the House of Commons and must keep its support. Therefore, once the office of Prime Minister becomes vacant, the sovereign appoints the person most likely to hold the support of the House of Commons. This is usually the leader of the strongest party in the House of Commons. In the present, it is practically a convention that the Prime Minister is always a member of the House of Commons, and not a member of the House of Lords.

The House of Commons can withdraw support from the Prime Minister by passing a vote of no confidence . The House of Commons can also indicate the lack of support by letting the government fail on a vote of confidence . Many other resolutions can also be interpreted as a question of the confidence of the House of Commons in the government. For example, important legislative proposals that are part of the government program or the annual state budget. If these fail, it can be assumed that the government no longer has the necessary support in the lower house. Traditionally, a prime minister was then forced to either resign from office or to ask the monarch to dissolve parliament. The dissolution then leads to early general elections. However, the Brexit-related defeats of the May and Johnson governments have shown that defeats in important votes can initially have no consequences if there are no alternative majorities. The Fixed-Term Parliaments Act 2011 also makes it difficult to dissolve parliament.

If the prime minister's party retains a majority of the seats in the House of Commons in a new election, he can remain in office. On the other hand, the Prime Minister has to resign if his party has lost the majority. After that, the monarch appoints a new prime minister. The Prime Minister can, of course, resign of his own accord without losing the vote. In such a case, the office goes to the new chairman of his party.

At the present time, most of the ministers are members of the House of Commons, not the House of Lords. Under a constitutional convention, all ministers must be members of either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. A few were nominated from outside, but in most cases they became members of parliament shortly thereafter, either by by-election or by peerage entitling them to a seat in the House of Lords. Since 1902, all Prime Ministers have been MPs in the House of Commons. The only exception was the Earl of Home , who, however, renounced his title and was elected to the House of Commons as Sir Alec Douglas Home. Members of the House of Lords are not allowed to be elected as peers in the House of Commons. However, they may forego their upper house seat and title.

No important position in the cabinet has been held by a lord since 1982. Exceptions are the Lord Chancellors and the respective leaders of the House of Lords. At that time Lord Carrington resigned as Secretary of State. However, some ministers of medium importance, such as defense ministers or development aid ministers, were staffed with peers. The fact that membership of the House of Commons is determined by elections rather than by birthright as in the House of Lords is seen as a factor that gives lower house ministers greater legitimacy. The Prime Minister selects the ministers and can decide to dismiss them at any time at his will. However, the formal appointment or dismissal is done by the monarch.

The House of Commons monitors the government by " question time " (Oral / Topical Questions to the .......). These question times take place in almost every meeting of the House. The individual ministers have a different number of question times depending on their importance. The Prime Minister has to answer MEPs' questions every Wednesday (Prime Ministers Questions, PMQ), which is always around 12 noon UK time and takes a little over 45 minutes. The questions must relate to the government activities of the minister concerned, they must not relate to his activities as party leader or ordinary MP. As is customary, members of the ruling party and the opposition take turns asking the questions. When interviewing the prime minister, however, the opposition leader has six questions and the leader of the second largest opposition party has the right to ask twice. In addition to oral questions during Question Time, MPs can also put written questions to the government.

In practice, the House of Commons' oversight of the government is very weak. Because of the majority voting system, the ruling party usually has a large majority in the lower house. Therefore, there is often a limited need to compromise with other parties. The political parties of the present day in Great Britain were so tightly organized in the "pre-Brexit period" that there was little room for MPs to act independently. As a result, the government lost confidence votes only three times in the 20th century - twice in 1924 and once in 1979. Often, however, the government is forced to give in by backbench uprisings. Sometimes the government also lost votes, such as with the Terrorism Act 2006 or with several votes in connection with leaving the EU in 2019 .

However, the government's strong position depends on the government actually being supported by a stable parliamentary majority. After taking office in September 2019, Boris Johnson's government lost seven of seven key votes in the Brexit environment: initially, some Tory MPs did not follow the government line and after they were expelled from the parliamentary group, Johnson no longer had a formal majority.

The House of Commons technically retains the right to indict Crown Ministers for crimes. Such charges are heard in the House of Lords, where a simple majority is sufficient for conviction. However, indictment has not been exercised for a long time and has therefore become unusual. The House of Commons now exercises control over the government through other means, such as a vote of no confidence. The final indictment was against Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville in 1806.

Others

Applause and heckling are forbidden in the House of Commons - unlike in the parliaments of many other countries. It is therefore common for MPs to comment on speeches with hear, hear (for approval), aye (“yes”) or no (“no”), which appears to be a loud murmur from the crowd.

In February 2020, a previously unknown door was discovered in the cloister behind Westminster Hall . You could find the hinges of two wooden doors, each three and a half meters high, with a small space in between. This room is said to have been built on the occasion of the coronation of King Charles II in 1661. Inside was handwritten “pencil graffiti”. It is believed that these were left behind by masons who helped restore the building after being damaged by fire in 1834.

Word origin

That the Anglo-Norman commune derived Midland word common or commune meant as an adjective "Collective, together, mean" as a noun "Community, community" and (starting directly from the adjective) "common people, distinct from the persons of rank or dignity" or in the plural "common [non-noble, non-clerical] people; Totality of citizens of a city; Community of free citizens who bear common burdens and exercise common rights; (hence) the representatives of the third estate in parliament, the lower house ”. In the original Anglo-Norman language , the word has survived to this day in the phrase Soit baillé aux communes ("should be forwarded to the Commons"), with which a bill is provided that is to be transmitted from the House of Lords to the House of Commons.

The historian Albert Pollard took a somewhat different derivation in 1920. According to him, commons should also go back to Anglo-Norman communes , but that means civil associations or the counties. The Oxford English Dictionary , the historical dictionary of the English language, can only attest to the word meaning advocated by Pollard from the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas the meanings given in the previous section date from the late Middle Ages, i.e. the time of the establishment of the House of Commons.

literature

- Kenneth Mackenzie: The English Parliament. Pelican Books, 1950.

- TE May, 1st Baron Farnborough: Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third. 11th edition. Longmans, Green and Co. London 1896.

- Parliament. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. 11th edition. Cambridge University Press, London 1911.

- Albert F. Pollard: The Evolution of Parliament. 2nd Edition. Longmans, Green and Co., London 1926.

- Edward Porritt, Annie G. Porritt: The Unreformed House of Commons: Parliamentary Representation before 1832. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1903.

- DD Raphael, Donald Limon, WR McKay: Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice. 23rd edition. Butterworths Tolley, London 2004.

Web links

- House of Commons - official website

- Literature by and about House of Commons in the catalog of the German National Library

- Wahlrecht.de - House election system

- The British Broadcasting Corporation. (2005). "AZ of Parliament."

- The Guardian (2005). "Special Report: House of Commons." ( Memento from February 15, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- The Parliament of the United Kingdom. Parliament Live TV.

- Legislation.gov.uk, Legislation 1267 – today

Individual evidence

- ^ Current State of the Parties. UK Parliament, accessed July 16, 2020 .

- ^ A b Heinrich Theodor Flathe : The age of restoration and revolution. In Wilhelm Oncken (ed.): General history in individual representations. Fourth main division, second part. Grote, Berlin 1883, p. 175

- ^ Boundary Commission for England: Boundary Commission for England announces review of constituencies , press release of February 24, 2016.

- ^ Welsh Government, Statistics & Research: Electoral roll , accessed October 10, 2016.

- ↑ Boundary Commission for England: 2018 Boundary Review initial proposals launched , press release from September 12, 2016.

- ↑ Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, Section 1. Retrieved August 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, Section 2. Retrieved August 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Payment and pensions of MPs in the lower house ( [1] )

- ^ Office and Role of Speaker. www.parliament.uk, accessed March 12, 2019 (English).

- ↑ Rules and traditions of Parliament , accessed September 22, 2019.

- ^ Parliamentlive.tv. Retrieved August 10, 2019 .

- ↑ By Lilit Marcus CNN: Secret doorway discovered under London's House of Commons. Retrieved February 27, 2020 (English).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd edition, 3rd volume: Cham - Creeky. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, pp. 564-567 (article common, a. ), 567 (article common, sb. ) And 572 f. (Article commons, sb. Pl. ).

- ^ Companion to Standing Orders .

- ^ A. F. Pollard: The Evolution of Parliament. Longmans, London 1920, pp. 107-08 (p. 107: Not that the house of commons was ever that house of the common people which it is sometimes supposed to have been. For “commons” means “communes”; and while “ communes ”have commonly been popular organizations, the term might in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries be applied to any association or confederacy. p. 108: The“ communes ”or“ communitates ”[…] were simply the shires or counties of England. )

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd edition, 3rd volume: Cham - Creeky. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, p. 576 (Article commune, sb. ).