African religions

After Christianity and Islam, the group of African religions forms the third largest religious complex in Africa , which comprises a large number of ethnic religions , cults and mythologies that exist in various forms on this continent and which, despite their differences, have numerous basic similarities. Since the Arab regions of North Africa have been Islamized since the early Middle Ages , this article refers in principle to sub-Saharan Africa .

Preliminary remark

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica , the number of followers of traditional religions was around 100 million in 2003, although this number is steadily declining due to intensive missionary work by Christians and Muslims.

To this day, almost 3000 different ethnic groups with at least 1000 different languages and numerous different cultural areas live on the continent . The consideration of the African religions must therefore be correspondingly detailed, especially their general religious foundations within the framework of their eco-social network of relationships. The presentation of the religious foundations must, however, be restricted to the extent that a time frame is to be set upwards, which relates roughly to the time up to the middle of the 19th century, when the period of massive European colonization began. Current conditions, on the other hand, are not primarily relevant for the assessment, since the religious patterns in Africa have changed rapidly since then, although many of these ethnic religions have remained alive up to our day, and sometimes have once again shaped culture under the influence of increasing African self-confidence.

The change of tense between the present and the past in the following description reflects this fact, because it is / has never been more precisely determined whether certain religions are still complete, partially, in traces, no longer or again and in the form described or in more or more less syncretistic form exist / existed. It was therefore deliberately left as it was as a content criterion and, as a primarily folk religious, sometimes class-specific factor of uncertainty , constitutes another essential characteristic of African religions as they are presently presented.

As is typical for all ethnic religions, some commonalities can be described, but the basic rule is that the African religions are also separate belief systems, which are often difficult to distinguish from one another only for uninitiated third parties.

Basic religious phenomena and concepts of African religions

Cavendish notes, “In general, African religions must be spoken of ... in the past tense. Most Africans have willingly or under duress adopted Islam (e.g. in North and West Africa, Sudan, and Somalia) or Christianity (in most of Central and South Africa). Very few tribes like the Yoruba in Nigeria, who are particularly conscious of their cultural tradition , have managed to preserve their original religion with a complete pantheon . ”However, these high religions are often only a thin varnish, especially in the area of popular religiosity outside the big cities in which the old religions have been preserved in part syncretistically , and in reclusive peoples one can still find them in their pure form.

- General characteristics:

- Generalized, Christianity and Islam are religions of the cities. African religions are more widespread outside the cities.

- The religions permeate all areas of life and do not form a separate world. Every event in life is attributed to supernatural causes. Religion is acquired as a birthright, religious conversion is not provided. The bond to individual stages of life is intense.

- The idea of a life force that connects the world with the metaphysical world is central.

- The African religion is life-affirming and has little love for asceticism. Their greatest value is all-round harmony, especially within the framework of the social community such as family, clan, clan, tribe, lineage, etc.

- In popular belief, however, there is also a lot of fear of ghosts, ancestors, magic, etc.

- Gods : All these peoples have the idea of a high god or creator god who is beyond human imagination and inaccessible, sometimes also appears as ancestral spirit or lord of animals or earth lord. This deity is often gender neutral, sometimes male or female. In some cases, such as the Yoruba of West Africa, a systematized polytheistic pantheon has developed, which also includes cultural heroes .

- Cosmogony : It is central to all African beliefs and contains the origins of peoples and their former migrations. She further explains the basic ideological questions of every culture such as the origin of life and death, the nature of society, the relationships between man and woman and of the living and the dead etc. Social values are mostly expressed in myths, legends, sagas, fairy tales, and puzzles the like encrypted; they are therefore often not easy to interpret for outsiders, as they often convey specific historical, local and sociological content.

- Myths : The African myths have themes that are common to many peoples and differ within Africa mainly in the details, not in the basic ideas. Most of them deal with the origin and death of man and a few customs. Some tell of creation, of the loss of paradise and immortality. However, Christian elements also seem to have penetrated some of these myths. Anthropozoomorphic hybrid beings are particularly present in African mask art . There are also myths about ghosts, magic and witches , diseases, etc. Thereby references to other continents and their myths stand out. Another myth is the social order and its origins. In West African myths in particular, twins play an important role, as do river gods and demons.

- Community : The African religions consistently emphasize the importance of community and place far less emphasis on the importance of the individual. Since they emphasize the factors that shape community, religions differ from one another above all when societies also do so. This is not only typical of West Africa, but more or less applies to all peoples of the continent. According to the colonial rulers, one of the main reasons for this behavior, which is unusual for Europeans, lies in the fact that Africa has very little fertile soils, which means that, in contrast to other continents, especially Europe, the relationship to the soil was poor. In contrast, the cohesion of the community, especially human work, was all the more valuable for the survival of the community. This applies not only to nomadic hunters and gatherers , for whom this attitude is more or less natural, but also to the rural population as a whole.

- Ancestors : There is a general idea of ancestral spirits and spirits of the dead, which under certain circumstances can acquire divine qualities. The ancestors, who are often viewed as members of the family, have their place among the most important cosmic powers, and especially in the West African religions they largely determine their character, have a protective and helping effect in everyday life, like the guardian figures in numerous African cultures also demonstrate figuratively. However, not every dead person achieves the status of an ancestor. Ancestors behave in a similar way to guardian spirits. With the help of people, dreams or visions capable of being a medium, the ancestors can express their wishes, which then have to be fulfilled as far as possible. However, there is by no means everywhere ancestor worship in the narrower sense of an ancestral cult. In fact, the African concept of God seems to have emerged from ancestral cult.

- The idea of being possessed by ghosts, especially in the media , also exists among some peoples, especially in Central Africa and the Nilotic language area , but is found in principle everywhere in Africa. Trance or ecstasy and séances , mostly through dances etc., never through drugs, are common. The obsession can be positive and used by medicine men or negative as a result of being taken over by a hostile spirit that must then be driven out. Eliade defines as follows: "The essential difference between magicians and the inspired is that the magicians are not" possessed "by the gods and spirits, but on the contrary have a spirit available to do the actual magical work for them."

- Spirits : The most important spiritual powers are usually connected with things or beings that people deal with on a daily basis or that they know from the past. Different types of spirits are assigned to different levels: air, earth, rivers, forests, mountains, thunder, earthquakes, epidemics, etc. The spirits are often personifications of these natural conditions or they are the souls of these natural phenomena (→ animism ) . Many spirits are involved in the family history.

- Magic , sorcery and witchcraft : To this day, the belief in witchcraft and sorcery is strong and served and serves above all to explain all kinds of misfortunes and misfortunes to people who were well aware of their limited control of nature and society. With the Yoruba , witches and wizards are also seen positively. Witches are always female among the West African peoples. Talismans are common for defense.

- Mystical Power : Belief in it is pan-African. People have different degrees of access to it. If it is used against others, it is considered spell or witchcraft, against which the community then defends itself. Often this power is used to achieve certain positive goals (until today for example in politics, in football etc.). West African voodoo is an example of this, which reached the Caribbean as a cultural souvenir from the slaves. (For Rastafari , Candomblé , Umbanda and other African-American religions , the starting point is similar, but usually more complicated.)

- Fortune telling and oracles , even ordals, are widespread, as is the magical influence of the weather and healing magic. As in other cultures, theterm medicine man is indicative of this.

- Religious actors : In most societies in Africa these are priests , clan and lineage elders, rainmakers, fortune tellers, medicine men, etc. Very few of them are professional specialists, rather they draw their authority from age, descent or social position and are only for responsible for the welfare of the group they preside over, which may for example be an extended family , lineage, local community, or clan , tribe or chieftainship . The medicine man, like the fortune teller, often goes through a long apprenticeship. The relationship between these actors and otherworldly powers is often personal and very close.

- Rites : They are used everywhere for certain stages of life, i.e. pregnancy, birth, initiation, marriage, death and burial and can be very different locally.

Up until the end of the 20th century, some authors (such as Mircea Eliade, Michael Harner or David Lewis-Williams) tried to expand their shamanism concepts - whose original ideas refer to the shamans of Siberia - to include Africa. Especially for Africa, however, it has been criticized that there is no "shamanic soul journey" , a calling by the spirits and certain characteristic utensils that are considered to be a prerequisite for these concepts.

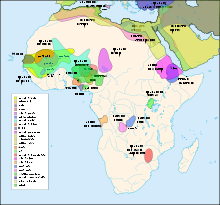

Classification according to Hermann Baumann

A regional classification, expanded by cultural criteria, was made in Baumann's posthumously published standard work "The People of Africa and Their Traditional Cultures" from 1975, which despite its age offers a good overview, as Baumann and his co-authors were still able to observe many phenomena at the time, which have largely disappeared today. (As far as possible, he deliberately aims at the pre-colonial status before the middle of the 19th century.) This combination also seems to be the most convenient to use when considering the African religions and given the multiple overlaps and overlaps.

If one takes into account the enormous regional inconsistency of ethnic, linguistic and cultural groups in Africa, there is inevitably a structure for Africa that should not be predominantly geographical, but rather oriented towards cultural phenomena, as presented by Sergei Alexandrovich Tokarev , against the background of the respective Forms of society and their strategies of subsistence identified three culturally distinguishable ethnic groups for Africa that are relevant to religious problems, as also postulated by Baumann (see below).

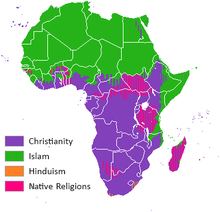

The division into spheres of the major religions must also be observed: predominantly Islam in the north, predominantly Christianity in the south , although this distribution is not unambiguous as there are sprinkles of the other religion on both sides. The fact that these major religions also exerted a considerable influence on the old religious ideas need not be emphasized in view of the similarity of this phenomenon to other comparable processes worldwide.

Taking into account the Baumannian cultural provinces of Africa, there is a sociologically relevant division into three main groups:

- Group I: The nomadic hunter-gatherers who know neither farming nor cattle breeding: " Bushmen " (now called San ), pygmies , Hadza .

- Group II: The peoples of Black Africa , i.e. the agricultural and livestock farming population of South, Equatorial Africa and Sub-Saharan North Africa ( Sudan Zone ), which make up the overwhelming majority of Africans: Khoikhoi , Bantu peoples , and the different language groups belonging to the peoples of Sudan and the region of the great lakes.

- Group III: The ancient and predominantly Islamic civilized peoples in North and Northeast Africa (see North Africa and History of North Africa ). However, this group is only marginally relevant here, insofar as there are syncretisms with the prevailing Islam and pre-Islamic remains of faith.

Group I: nomadic hunter-gatherers

As in the following sections, only the basic features and most important phenomena are presented here, but not the overall structures of the respective religions of the individual ethnic groups and the similarities already described in the previous section. Individual, often very small splinter groups, most of which have acculturated to their rural neighbors anyway and about which little is known, are discussed below in connection with the respective rural neighbors, as far as information is available about them. Overall, there are the following larger groups of predators in Africa:

- Steppe game hunters (salt steppes, dry savannas):

- In SW Africa: San, Bergdama, Kwisi

- In East Africa: Dorobo, Hadza, etc.

- Forest game hunters ( tropical rainforest , rarely wet savannah ):

- Pygmies and Pygmoids (Congo, Rwanda)

The San, Hadza and Bergdama are discussed as representative for the first group, the pygmies for the second, since the best information about religion is available for these peoples.

- A Khoisan- speaking group of steppe game hunters in the arid savannahs of South Africa, presumably remnants of a once much stronger indigenous population who were later displaced by cattle nomads and farmers who later invaded. They live in clan associations.

-

Totemic ideas are recognizable in the myths and the animal names of the clans and in the rock drawings, which show many anthropozoomorphic figures (see above). They were very afraid of the Gaua , the ominous spirits of the dead, but no actual ancestor cult.

A hunting magic cult is typical. Prayers are addressed to natural phenomena such as the moon. What is striking is the worship of the Mantis or Praying Mantis, the Mantis Ngo or Cagn standing with an invisible heavenly Spirit in touch and also acts as a culture hero. As Kaang , she is a creator deity among the Lesotho San and can transform herself into different shapes, and also takes care of the physical well-being of her creatures. Other animals such as the rain bull Khwa have a strong mythological reference or are patrons of the tribal initiation. Belief in power and soul mix with the San with an emphatically magical thinking (belief in magic). - The medicine man being associated with the magical world is very pronounced in all San. Medicine men are said to provide rain, for example, by conjuring up the rain bull; they could turn into animals. A distinction is made here between good and bad wizards. They are healers who try to get the spirits under their control through dance and ecstasy or to influence what happens in nature through analogy magic. Wizards go through a long training and have their own ceremonial costume. They see the spirits of the dead and speak to them to ask for help, make amulets and act as fortune tellers. Their magic arrows are feared.

- Steppe game groups of equatorial Africa

These are nomadic, mostly very small hunter-gatherer groups in northern Tanzania : the Hadza , the Aasáx , the Omotik-Dorobo and the Akie-Dorobo

The religion of the Hadza is minimalist. They place little value on rituals, and their way of life offers little room for mysticism, ghosts or thoughts about the unknown. There is also no special belief in the hereafter, nor does priests, necromancers or medicine men. God is seen as dazzlingly bright, tremendously powerful and important for life and is equated with the sun. The most important Hadza ritual is the epeme dance on moonless nights. The ancestors should come from the bush and take part in the dance.

- Mountain Dama ( Damara )

- This hunting people, formerly also known as "Klipkaffer" (but they also keep goats), live in the inaccessible regions of the mountains of South West Africa. They live in family clans and build their shipyard, called semi-nomadic settlements, around a sacred tree (shipyard tree) and a sacred fire.

The head of the family is also the religious head. There are no chiefs or tribes, but there is a healer. Initiations were common as "hunter consecration". The woman's position was strong. - As with San and Khoikhoi, the fear of death is central . The dead man's path to the hereafter is seen as dangerous and arduous. When the dead have reached the afterlife called “Gamabs Werft”, they are immortal and happy. Gamab is the central figure in the religion of the Mountain Dama , a kind of omniscient, omnipotent, supreme divine being. Wizards seek advice from him, but he also has dark, terrifying aspects and is lord of the dead, who feed on the flesh of the deceased. The dead can also wreak havoc as ghosts, and funeral customs aim to prevent this from happening. In addition, the dead can smuggle the living germs into the body.

- The magician called Gama-oab , Gamab's man, can suck these magical pathogens out of the body again after he has learned in a conversation with Gamab where these germs come from. At the same time, he learns about Gamab's future plans and can warn the villagers and give them repellent if necessary, so he acts as a fortune teller. These wizards are called by Gamab without their being able to defend against them. By singing magic songs they get into a trance, and their mind can then go to far away countries, even to the countries of Gamab itself beyond the stars, that is to say a heavenly journey. The bystanders read the future from the features of the ecstatic and learn all sorts of useful things after waking up.

The Mbuti pygmies of the Ituri forest are representative and best researched.

- The forest is at the center of religion and life as a whole.

- Patrilineally organized hunter-gatherer groups (hunters headed by an elder) who live in the Congo and some other areas of Central Africa, but have also become hackers and planters under the influence of neighboring cultures. Small local groups are usually united to form a totem clan, which, however, has no common head.

- Their most important religious and magical ideas are related to hunting and they revere a forest spirit as the master of the animals . The Bambuti and other groups of the Ituri forest, where the most original pygmies live, mostly only know kin totems, which are considered the origin of the kin, mostly animals, occasionally also plants. Individual totems are also occasionally selected. Totems may not be eaten or used in any other way, but they are consistently inedible or difficult to hunt animals. Certain spiders and beetles as well as the chameleon are considered messengers of God. After the death of the clan leaders who act as religious heads, the soul is embodied in the totem animal . The soul then becomes the advisory spirit of the dead. A funeral cult is hardly developed and is mainly presented as an exposure to the dead. There is no actual cult of the dead.

- The belief in both beneficial and disastrous powers of nature is alive. The Mbuti wear powerful amulets. At the center is the belief in a life force that is passed on from the elder to all members of the community. The power comes from the deity who is invoked through rites such as dances around the sacred fire and chants as well as the sound of the lu-somba trumpet.

- Initiations , which are understood as communication with the magical power that is indispensable for a hunter, are central . Initiations and the associated male secret societies are unknown to the Gabon pygmies.

- There is the idea of a high god who lives in the forest and is not expressly worshiped, but whom one asks and to whom one sacrifices. It appears in the rainbow and in the sun and, as a giant elephant, is the support of the sky. Among the Gabon pygmies, as kmwum, he is identical to the lord of the animals and is then also worshiped. But sometimes he also teases the pygmies. Totem ceremonies are common, they also serve healing purposes.

- All in all, there is a world of ideas that is difficult to separate from animistic and non-animistic thoughts , from the living corpse to multi-layered ideas of the soul and spirits of the dead that appear in dreams and are even sacrificed. The fear of ghosts and ghosts is predominant. A personally defined medicine man is unknown.

Group II: Rural and pastoral populations of sub-Saharan Africa

The cultures and ethnicities of this second large religious group, which are characterized by an agrarian subsistence strategy as farmers and / or shepherds with corresponding religious forms and occasionally old sacred kingdoms, prove to be extremely heterogeneous and confusing, but generally follow the criteria mentioned above. The division of the state, which is partially incomplete or only present in relics, follows the division into cultural provinces progressing from south to north, as made by Hermann Baumann. In the process, ethnic groups with their basic religious features in connection with their most important social and economic factors are represented paradigmatically within the framework of the large geographic-ethnic regions. The region includes the modern states of South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, Angola, Zambia and Madagascar.

- The Khoisan speaking peoples of South Africa

- ! Kung-San ( ǃKhung ): See above. They are hunter-gatherer nomads.

- Bergdama: See above. They are hunter-gatherer nomads.

- " Hottentots ": A discriminatory collective term used by the Boers for the first time in the colonial era for the Khoi Khoi ethnic family living in South Africa and Namibia , to which the Nama , the Korana and Griqua ( Orlam and Baster ) belonged. Ranchers with a strong hunter component; however, the economic transitions to the San are fluid. The Cape and Eastern Khoikhoi are now extinct. Their religion is similar to that of the San: fear of the dead, honoring the ancestors, but no ancestral cult, anthropozoomorphic, malicious spirits of the dead, high god, personification of natural forces, divine, sometimes as creators, sometimes as tricksters appearing cultural heroes ( Tsui Goab, Heitsi-Eibib, Gaunab ), some of which act as rain bringers, moon cult. Oracle.

- The Southeast Bantu

The best-known groups are the Zulu belonging to the Nguni , the Sotho , Swazi , South Africa-Ndebele and the Zimbabwe-Ndebele , Tsonga , Batswana , Venda and the Shona, also known as Matable . They live in South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe as ranchers and farmers and have a complex social system with tribal chiefs .

Their religion has an intense ancestral cult as its center ; every clan has its ancestral gods to whom sacrifices are made. Heaven and world creation gods are of little importance. There are also cultural heroes, archaic heroes, nature spirits and tricksters . An actual animism in the sense of animated stones, trees or other natural phenomena does not appear, but the idea of soul spirits who can be in such places. The human soul is something else, a kind of life force that can leave the body during sleep (dreams). There is a great fear of magic by wizards and witches as well as transformable animal spirits. Specialists practice divination . Among the Nguni, male and female magicians ( sangomas ) summon ancestral spirits in trance evoked by dancing . Secret societies and the associated dances such as the Nyau dance of the Chewa have a social regulatory function and a religious background based on ancestor worship .

A cultural intermediate area with different peoples like Danda , Karombe , Lungu , Karanga etc., who lived or live mainly as hunters and cattle breeders and developed a complex polygamous social system with a relatively strong position of women in religion.

In religion, animal worship is sometimes important. Individual cattle were considered representatives of the ancestors, and an ancestral cult was pronounced. The focus is on a rain cult as a fertility cult, which is ruled by priestesses. A somewhat diffuse high god exists. Mwari appears as the rain god , who later partially degenerated into a cave and oracle god. Correspondingly, there was fortune-telling up to and including an intestinal inspection. In addition to the cult of rain and ancestors, the cult of possession ( Mashawe ) plays a major role. The stars were connected with the ancestors.

- The Southwest Bantu

Peoples who mostly live as cattle breeders in southwest Angola and northern Namibia :

-

Kwisi and Kwepe : Remnants of hunter-gatherer peoples who, like the Kwepe, also keep livestock and about which little is known. They resemble the Mountain Dama (see there).

Religion: The ancestors are sacrificed, a high god who is also responsible for hunting success is worshiped. The fortune telling nature is pronounced. One does not know foreign spirits. Among the Kwepe, the cult applies above all to the deceased and the sacred cattle. -

Himba , Kuvale and Herero : A group of peoples who keep livestock, the Himba occasionally also cultivate crops (millet), as do the Herero.

Religion: Himba and Kuvale are culturally very similar. The Kuvale also know sacred cattle. The lion is considered to be the rebirth of the souls of the dead, and lion magic is common. The Himba know the healing trance performed by women , in which spirits are expelled from the sick, as well as the intestinal inspection as an oracle. There are also hunting rituals.

The Herero settle around a sacred shrub as a symbol of the primeval tree from which people came. Fire is also sacred. The chief is also considered holy and has a priestly function. There is a sacred cattle ritual and an intense ancestor cult. Certain aspects of culture and religion are considered Nilotic . - Ambo and Nyaneka-Humbi : Shepherd planters with a matrilineal clan organization. The clans mainly have animal names, as is characteristic of totemism, but without the associated myths of origin and taboos . The dead are at the center of the cult. Even Kalunga , the high god of the ambo, is occasionally considered to be an ancestral god connected to the earth. Foreign demons induce obsession in women. Such women form a cult association. Medicine men are partly transvestites, they and homosexuals also play an essential role in the cult of possession . The Herero-Kuval group practices a cattle cult , mostly as an ancestor cult. The Nyaneka, Humbi and Handa also celebrate numerous cattle festivals. The milk of the holy cows must not be consumed with the meat (cf. Judaism).

-

Mbundu and mbundized shepherds: At the Mbundu, maize and millet cultivation, small and large animal husbandry. Patrilinear, remnants of a matrilinearity are present. Hierarchical chief rule; the village chiefs are responsible in the matrilineal line for the ancestral altar and the spirit hut of the family spirit. Totemism occurs only among the royal families.

High God is Suku . He created the world, but is far away, but often also stands for the head of the spirits of the dead. One of the spirits is the ghost ocilulu , which arises from the shadow of the living, is the cause of illness and is absorbed by the person concerned in a trance. Spirits of paternal relatives are more harmless than those of maternal relatives. Ahamba are the peaceful spirits of the long dead. There is also a family founding spirit, hunting demons and even a master of the animals . The medicine man ocimbanda works with a fortune-telling shaker. Witches are feared; their power is passed on matrilinearly.

The mbundized pastoral peoples still have remains of a hunter culture. In general, however, little is known about them. The high god steps back behind the cults of possession and the cults of the dead / ancestors. Believe in a realm of the dead under the earth with underworld gods.

- The Zambezi Angola Province

Together with the southern Congo province, which is differentiated by the formation of large states, it forms the central Bantu province and is culturally relatively homogeneous with the character of a “cattle breeding complex”.

As far as religion and myths are concerned, the Zambezi-Angola area is little out of the ordinary among the Bantu. The importance of the rain doctors in the dry south, the reincarnation idea with transformation into animals, the intense obsession and the power of the harmful magicians are important .

- At the top are indifferent high gods with a minor cult, including sub- gods without a systematized polytheism having developed. Their character varies within the area.

- In addition to the natural and functional spirits , the deceased form a middle class between humans and gods. One sacrifices them in ancestral hut, guard figures are common. Cult trees are important here. Man lives on as the spirit of the dead who cares for the living of the clan and is sacrificed to it. They are related to the high gods and are mostly only forms of transformation of one aspect of the living, so that there can be several for one deceased. There is the idea of a heaven beyond. In the eastern part of the province there is a belief in rebirth in animals.

- In addition to the spirits of the dead, as in many parts of East Africa in particular, there are also natural and functional spirits , which often act as mediators. Bush spirits with a rather fabulous character often act as vengeance spirits of the animals. In addition, there are heroes and gods of nature.

- The obsession is divided into two main groups:

- Mediative obsession : The obsessed is the medium of spirit power here. As a tribal medium, it establishes a connection between you and the tribe members and takes care of the interests of the tribe, state, etc. Typical for this are certain professional groups such as fortune tellers, doctors, hunters, etc., who all have to incorporate the necessary ancestors in a trance. Fortune telling is more common in the west than in the east. Narcotics are not used here, clapping, drumming and dancing are enough to create a trance.

- Afflictive obsession: The alien spirit usually invades against the will of the person concerned as a serious illness, in which the obsession can also become chronic. Here, too, trance and revelation are decisive, only that there is no medium and the person concerned temporarily becomes the possession of the spirit.

- Magic: The ideas of magical powers and actions as well as the people who specialize in them do not differ significantly from those in the rest of Africa. Death and illness are in the foreground. Hunting magic is widespread, in the past there was also war magic, while magic field builders are rarer. The opponents are the medicine men, who trigger positive effects, and the harmful wizards and witches, whose power is often innate. Harmful wizards often practice necromancy and can transform themselves or their victims into animals, usually lions or hyenas, in order to make them subservient. Further auxiliary beings are anthropozoomorphic snake spirits. Another type of magician is the fortune teller, who, thanks to his gift of obsession with oracles, gives the medicine man diagnostic and other clues for his work. Regionally different techniques are used for fortune telling, but no animal oracle and no intestinal inspection. Ordals occur.

- The myth is little developed and only appears more clearly in dynastic areas with a king ancestor cult, as was the case in most of the early African states.

- South Congo

In this area, which stretches from the Atlantic to Lake Tanganyika and from the plateaus in the north of Brazzaville to the southern border of Zaïre , live savannah peoples who once belonged to the ancient states there and have preserved corresponding cultic remains. Field cultivation (maize or cassava ) as savanna planting or forest planting with slash and burn are the economic basis. Pets are known. Hunting is seldom practiced, and fishing is mostly done by women. Matrilinearity prevails, but patrilinearity also occurs. Luba , Tio , Lunda and Hemba are the best known of the numerous ethnic groups.

The religions of the area are similar down to the linguistic names. All believe in an anthropomorphic creator god , to whom no cult is dedicated, but who is invoked individually. Belief in spirits is widespread. Nature spirits are invoked by the chiefs, cults are also dedicated to them, which are often in the hands of magicians.

Ancestral belief is also widespread; the dead live underground or in the ocean; some ancestors are dangerous. Sometimes the ancestors fulfill the functions of the nature spirits. The ancestors are sacrificed and they have their own sanctuary.

The fear of witches is common. Protection against them is achieved through magic drugs, which are the focus in many places. The fortune teller medicine men use oracles to explore the cause of the respective witchcraft. Rites are sacrifices that are accompanied by taboos, plus prayers, formulas and ceremonial gestures. They aim to preserve fertility and the blessing of the hunters or are invocations of the ancestors etc. There are also social rites such as initiations, burials etc.

- Northern Congo and Gabon

For the pygmies living there see up under the hunter cultures.

- The West:

In this area with planter populations, the influences from the south and north, west and east cross each other, so that a very heterogeneous cultural image emerges. In the northern region, the coastal Bantu and seven other population groups live in particular, in the northern and eastern region around 40 peoples, but who have a uniform understanding of their origins with a scientifically high degree of uncertainty, which is not least the result of the numerous, no longer comprehensible migratory movements of these peoples is. Characteristic of their subsistence strategies is simple hacking , the so-called tropical shifting cultivation , which was the result of the low fertility of the rainforest soils after clearing, as well as wild cultivation, which does not require any further maintenance measures and does not have any stock management. Goats and sheep are kept, but no large animals. Hunting plays a subordinate role, except for the Pygmies and other hunter-gatherers. The economy is semi -self-sufficient and requires an exchange of own products, which takes place in the so-called "women's border market trade". There is no state organization whatsoever in social life. In the north the patrilineal , in the south the matrilineal family association or the clan is the highest social unit. Secret societies and initiations are typical.

The religion is characterized by an ancestral cult, which surpasses the god cult in importance. Images of ancestors are widespread as guardian figures, and people believe in the powerful influence of ancestors on this world. Patrilineal worship is separated from matrilineal worship. Fertility cults are also common with their rites. The phenomenon of obsession , which is often associated with the worship of earth, water and rock spirits , has persisted in the women's associations. The belief in witches and magic power ( likundu ) is also widespread . In the meantime, massive Christian influences have triggered partly syncretistic religious phenomena , such as the bwiti cult that emerged from the ancestral cult. The old solar and creator deities were also displaced in this way. Overall, "a magical, non-animistic world of ideas (ancestral cult, hunting magic, magical beings) dominates, which is of course interspersed with animistic elements (nature, possessed spirits), especially in the sphere of influence of maternal tendencies."

- The central part:

The grass savannah predominates in the north, the equatorial rainforest in the south. The north is inhabited by Bantu tribes, especially Mongo and Ngombe , the south by groups who speak non-Bantu languages. Ngombe and Mongo share most of the ethnic characteristics, and the two smaller groups, the river people and residents of the Ngiri area, generally follow this pattern. Most races are patrilineal and polygynous . The social basis is the lineage with clan structure.

The religion is determined by the well-known factors High God, who is regarded by the Ngombe as a tribal cream, ancestral beliefs, spirits of the dead that can occasionally transform into animals, obsession, traces of totemism, magic and the practices associated with it, fear of witches.

The non- Bantu, especially the Ngbandi , Ghaya-Ngbaka , Banda and Mbaka have different cultural patterns and beliefs, which, however, seem to be strongly influenced by those of the dominant Bantu. The ancestor cult in particular is more pronounced.

Another group are the pygmoids known as Batwa , who live from hunting and exchange their prey with the Mongo for crops and live with the Mongo in a kind of client relationship. Since the colonization they have largely given up their nomadic way of life and culturally adapted to the Mongo.

- The East:

The population is very heterogeneous and comprises three major groups:

-

The peoples of the Balese / Komo area: The area includes the large equatorial forest east of Kisangani . Shifting cultivation is practiced. Patrilinearity. Unity is the village that is sometimes led by a chief, which also represents a religious unit.

Like the other peoples of the region, religion is determined by the following principles: high and creator God, sometimes a bringer of culture. Both sometimes flow together with the ancestors, because the ancestor cult was cultivated everywhere. Protection spells with amulets were common. Death or misfortune has been attributed to witchcraft. Fortune tellers / healers announced their oracles. -

The intermediate sea Bantu of the Kivu area: Central part of the extreme east of the Republic of the Congo; a wooded savannah with great differences in altitude (100 to 1900 m). Several peoples live there, including the Shi, Furiru, Havu, dogs, Tembo, Yira, as well as the Hutu and Rundi . They speak all of the East Bantu languages and raise cattle. Patrilinearity. Strongly centralized society with chief chiefs and a class of nobility.

The religion is strongly syncretistic because of superimposition: high and creator god, pantheon of great spirits on / in volcanoes, where the most outstanding men of the deceased live (the others in the underworld). The Nyanga believe in water and land spirits. -

The peoples of the Maniema region: The peoples living there are considered to be mixed race of pygmies and Bantu (see also pygmoids). They belong to a uniform language group. Economy: You know the field of agriculture, but were mainly hunter-gatherers and fishermen. Blacksmithing and pottery were known. Society: patrilineal and segmental. The maternal line was also important and was divided into seven categories. Secret societies were common, and they also formed the basis of the political structure.

In religion there was a creator god who was regarded as the first ancestor or cultural hero. The belief in nature spirits was developed, but the focus was on the ancestor cult, which was developed as a skull cult and connected with requests and sacrifices. Charms were of little importance, but witchcraft was important, as was oracles. There were professional healers, some of whom specialized in certain diseases, as well as fortune tellers.

General characteristics of religion: multiplicity of causes for evils of all kinds, large number of specialists, importance of religious experience in dreams and trance , which was often lived out in one of the covenants, the large number of men and women who were religiously active.

- Madagascar

Madagascar , the third largest island in the world, is relatively sparsely populated. There are 18 different tribes, but they form political units, not cultural ones. These include soil farmers, shepherds (mostly mixed subsistence), fishermen, rice farmers. Due to excessive slash and burn, however, subsistence opportunities are now limited. The social basis is the extended family with elders and the aristocratic class.

Religion: The majority is not Christianized. The old tribal religion is based on the ancestor cult .

- Apart from the shapeless creator god zanahary there are no other gods. Zanahary is very distant as High God and does not intervene in the fate of the individual, but gives and takes life.

- The ancestors are decisive in both good and evil. They are at the same time mediators between this world and the hereafter. Exact ideas about the realm of the dead are unknown. When making sacrifices, God and the ancestors are always invoked.

- Besides the spirits of the dead lolo, there are mountain, water and river spirits, as well as spirits called kokolampy or vazimba , which can harm people.

- Sacrifices that are carried out by priests, as well as many rituals, commands and prohibitions are part of life. The human being consists of body, mind and soul, which can leave the body while sleeping or when unconscious. It becomes holy after death according to social rank.

- Here, too, there is the division between the harmful magician and the medicine man . The latter, however, have since disappeared. Medicine men had a training period of up to 15 years and then went through an initiation at the grave of a dead medicine man, in the course of which they received their insignia. On the highlands, an assistant healer called the spirits, who spoke from the medicine man in a trance and were interpreted by him. There were also fortune tellers (mpisikidy) who often worked with medicine men.

- Magic is an essential religious element. These include the oracles already mentioned ( sikidy ), vintana , a kind of astrological oracle based on Arabic month names, the ancestral oracle fady , which applies to the entire life or at least stages of life as well as the whole group, and finally the amulets called ody .

- Equatorial East Africa

The area, also known as East Bantu , is bounded in the east by the Indian Ocean, in the west by the chain of great lakes around the 30th degree of longitude, the northern border runs along the language border to the Nilots, the southern border around the 12th degree of latitude including the Comoros and the coastal regions inhabited by the Swahili to Cape Delgado . There are mainly highlands and dry savannahs, plus some rainy mountain and coastal regions, but also thorn bush and tree savannas. The area is extremely heterogeneous culturally and ethnically. The most important peoples are the Swahili, East and Northeast Bantu , Mbugu , as well as the hunter groups of Hadza, Aasax Dahalo, Liangulo, Twa and Dorobo, the Kawende and numerous other, mostly smaller, often linguistically characterized groups in this linguistically most heterogeneous group Area of Africa. The clan or clan internal organization is mostly patrilineal. There used to be sacred kingdoms in some places (see History of North Africa ). All forms of economic activity occur: field cultivation (slash and burn, shifting cultivation, field change management), cattle breeding, fishing, hunting, collecting, sometimes mixed.

Religion: Characteristic are conceptions of high gods, with the Sonjo a cultural hero, ancestor worship and cults of possession, fear of witches.

- The very inconsistent notions of high God are “un-Islamic and non-Christian”, the notion of the realm of the dead is diffuse and determined by the cult of ancestors , all in all on this side with the main question as to what extent the dead have an impact on this side. Royal ancestors play an important role in some places, especially in the catchment area of old monarchies.

- Obsession cults are common, especially as obsession with alien spirits. Medicine men and women play an important role in these cults, which are also determined by trance, as they drive out these spirits and are also active as healers.

- Witchcraft and harmful spells due to an innate mystical power are feared, and people accordingly believe in magic that is used by ritual specialists.

- Northeast Africa

An area with a relatively mild climate in the Horn of Africa , Somalia and Ethiopia , in which mainly Ethiopians and immigrant Arabs live in several large ethnic groups, in which the influences of the Christian and Islamic high religions overlap and even larger "pagan" remnants exist or . had:

- The Tigre- speaking ethnic groups of Eritrea and the Bogos : The old beliefs have been largely destroyed by Christianity and Islam. In the cafeteria there are still remains that can be generalized to all northern tribes: The fate of people is linked to the stars, so that numerous cult acts are connected with it. The realm of the dead lies underground and is a copy of this world. The dead souls appear to the living and admonish them. Soul birds are people who have died unfulfilled. There were rain rites with animal sacrifices. Fear of the evil eye, belief in werewolf and fortune telling are still widespread. Among the Bogos, the god's name Jar is reminiscent of the old Kushitic sky god.

- High Ethiopian peoples: The religion of the Amhara and Tigray is determined by the Christian Ethiopian Church . In the rural population, however, remnants such as the werewolf belief have been preserved. The Agau were, until recently, followers of the ancient Cushitic religion and worshiped a god of the sky. The Gurage have retained their pantheon of gods and are the great exception for Ethiopia. The Harari , in turn, are Muslims with an Arab influence.

- Eastern Cushitic speaking peoples: The Somali are superficial Muslims, religious remains are hardly preserved. The same applies to the Afar , where the old cult of the rain sacrifice has been preserved. The Oromo , on theother hand,still cling to their old religious customs. Sky god and earth goddess stand side by side. No priests. The sacrificial priest is the head of the family. There are only vague ideas about death: mostly a sky god and an earth goddess. The smaller ethnic groups also have similar ideas. When fandano -called religion of Hadiya , Christian and Islamic syncretism find.

- Omotically speaking peoples: All groups know an otious sky god. Remnants of a hereditary priesthood are preserved. Cults of obsession priests are practicedeverywhere,especially among the kaffa . A crocodile cult, formerly with human sacrifice, exists. In some groups such as the Gimirra the ancestor cult is pronounced with ancestral spirits to whom sacrifices are made. With the Gimirra, however, the cult of possession is also in the foreground, whereby the priests connect with the spirits of possession during seances.

- West Ethiopian fringe peoples: Here the sky god is often identified with the sun and sometimes celebrated orgiastic and with bloody sacrifices. The most important priestly functionaries among the Kunama are the rainmakers. They live isolated on mountain peaks, and their office is hereditary , as with the Gumuz . Fortune tellers come into contact with the dead souls during phases of possession. Birds and hyenas are considered soul animals. Other ethnic groups are also familiar with the phenomenon of possession with the associated belief in the guardian spirit.

- The nilots

- Niloten: Peoples who live south of the 12th north latitude along the Nile and are in part quite similar linguistically, anthropologically and culturally, as well as peoples in southern Sudan , Kenya , Uganda and Tanzania . The ethnic unity of these peoples, especially the Nuer , Dinka and Luo groups, is reflected in the myths. The landscape is diverse and ranges from dry savannahs to the Sudd swamps to the Central African plateaus and the rivers of the Nile catchment area. Correspondingly, cattle breeding is mostly common, as the soils are unsuitable for farming and periods of flooding and dry seasons alternate.

The religion shows certain general traits: A mostly otious high and creator god, often called Nyial or Jok , to whom one can turn through the mediation of the mythical tribal founder Nyikang and who expresses himself in all phenomena, even designating the sum of the spirits of the dead. Spirits of the dead can also become malicious and sit in the bones of the dead. Medicine magic is less well known, rather medicinal effects are ascribed to a ghost, and accordingly magic doctors get their power from this or from a Jok himself that drives into them. The same applies to the rain making, in which, among other things, animal sacrifices are common. Fortune telling is common. Special features concern the Dinka and Nuer, where magical elements hardly occur. The Acholi have Bantu influences, which are expressed, among other things, in an increased ancestor cult. The Bor, who belong to the Dinka, also show acculturations with non-Nilotic neighboring tribes in the form of an increased role of magic, witchcraft and sorcery, whereby the fortune-telling patterns were completely adopted. Occasionally, as with the Schilluk, local royal cults still play a role. The religion of the Nuer is largely spiritualized with spirit beings that symbolize various aspects of nature and with an increased importance of earth spirits in divination and magic. The Luo have great angat before the dead.

- Hamito Nilots: There are three main groups:

- The northern group on the Sudan-Uganda border: Mainly Bari , Luluba , Lokoya and Lotuko .

- The central group in NE Uganda and NW Kenya: Mainly Toposa , Turkana , Karamojong and Teso .

- The southern group in W-Kenya and N-Tanzania: Mainly the Nandi and Maasai .

In addition, scattered groups of hunters of the Ligo , Teuso , Dorobo and remains of old planters live in retreat areas . The landscape features dry and salt savannahs. The type of economy fluctuates, depending on the landscape, between planters and cattle nomads, mostly cattle, which are also ritually central. Socially, the tribe, which is often divided into totemic clans, is the main form of organization, albeit without a chief.

The religion is determined by the high god, who is invoked and sacrificed at any time of the day. Ancestral spirits are mediators to him. In the central group, however, the belief in ancestors disappears almost completely, and one does not believe in survival after death. The Maasai of the southern group only believe in the survival of the rich and medicine people, namely as snakes, and have no actual ancestor cult, but believe in a god Engai . Like other ethnic groups in the area, they also have rainmakers and “earth chiefs” who are responsible for earthly matters. Magical rites are particularly well trained. Islamic and Coptic influences occur mainly from the coast, especially among the Maasai.

Little is known about the religion of the small, pygmoid forest hunter groups. They believe in tree, water and nature spirits and are feared for their magical abilities. However, many of them have acculturated to neighboring groups in the meantime (see above).

The Maasai are representative of the southern group . Their social structure is belligerent, the clans are patrilineal and totemistic. The war chief, known as Laibon , has primarily religious functions and acts as a mediator between man and otherworldly powers. The so-called blacksmiths (Haddad) are the lowest caste, but they are feared all the way into the Sahara because of their magical abilities (see below under the Tuareg ).

The religion and culture of the other ethnic groups of the southern group such as Nandi , Kipsikis , Lumbwa and other splinter groups are strongly influenced by the Maasai. The high god is identified in various ways with the sun, ancestral spirits are considered active clan members, snakes are also sometimes considered to be incarnations of the ancestors. In general, the cult of ancestors is very pronounced everywhere.

- The Central African cultural province

What is meant here is the area in the “heart of Africa” north of the cultural province of Northern Congo with roughly the same east-west extent, but with its own cultural character. The area roughly coincides with the Central African Republic , a river-rich country with a semi-humid tropical climate and transition to the rainforest climate as well as moderate altitude differences except in the north. Wet savannahs with poorly fertile soils are typical. The area was repeatedly crossed by peoples and therefore offers a picture of confusing diversity in terms of language and ethnicity. Because of their Islamic culture, two peoples are particularly important: Arabs and Fulbe . In addition, there are 11 other population groups such as Wute, Manja, Banda, Zande etc. The main forms of farming are agriculture and hunting. One differentiates:

- The western marginal cultures with Wute and Mbum: The Mbum had a sacred kingdom with ancestor cult and reincarnation ideas in the foreground. There was a strong fear of wizards and witches, and accordingly magic played an important role. People believed in human-animal transformations. In addition to the sacred kingship, the rage also includes a concept of high god, totemism and values. What is noticeable is a pronounced good-bad dualism in people and spirits.

- The central cultures: ancestor cult with sacrificial creatures and magical complex, reborn spirits of the dead, high god, culture bringer among the Ghaya , among the Mandja , human-animal transformation after death, otious high god and thunderstorm god, fear of dead spirits, totemism. With the Banda the worship of the ancestral spirits is in the foreground. Similar religious patterns can also be found among other peoples. Magic belief shows up everywhere. The Ndogo believe in a soulful world and a supernatural power as well as personal protective spirits. The Zande's belief in magic is particularly pronounced and has a profound effect on their social institutions. Otherwise, their religious life is limited to ancestor worship. In contrast, belief in nature spirits is not very pronounced here. In several of these peoples, the formation of states also led to overlapping rulers with strong social stratification.

- The eastern marginal cultures on the Eisenstein plateau : There is a colorful mixture of different ethnic groups, especially in the east Nilotic cattle breeders, in the north Arab cattle nomads, on the plateau South Sudanese tribes with shifting agriculture. Here and there rain magic occurs with rainmakers ( Makau cult ). The Bongo know as manifestations of Loma , the high god who is also morally demanding in this world and in the hereafter, a lord of the animals, a lord of the forest and the river. Rites of atonement towards the Lord of the Animals are important. He can be influenced by magical means. Fear of witches and the vengeance of the dead. Oracles are common. Ancestral and nature spirits.

- Central Sudan

Central section of Sudan between the Logone and Niger , bordered by the Sahel zone in the north and the tropical rainforest in the south. Predominantly dry savannah, topographically open to the trans-Saharan trade . In the broadcasting area of old territorial states such as Kanem-Bornu and the Hausa states . Outside of this Islamic area in the Niger Benue Depression, “pagan” ethnic groups. Especially hackers, few and only small pets.

Religion: Everywhere there is a belief in a high god, but no cult is dedicated to him unless he also functions as a rain god. Pronounced ancestor cult with a belief in rebirth, occasionally combined with the idea of a judgment of the dead in which the earth god plays an essential role. In the context of the prevailing patrilinearity, the male ancestors are of particular interest. Men's cult associations are common. This is accompanied by agrarian rites , which are always commemorations for the dead, as well as rain rites carried out by hereditary rain priests, who are the supreme religious authority in some tribes such as the Loguda, Yungur, Gabin and Mumuye . The Sahara blacksmiths ( Inadan ) are responsible for the oracles in the Mandara Mountains . Menhirs and megalithic sites are not uncommon in the mountains . Headhunting used to be common. There are various sacred chiefdoms and functional deities with royal ancestors. Belief in guardian spirits representing the ancestors is widespread. An essential phenomenon among others among the Islamic Hausa , the non-Islamic Maguzawa belonging to the Hausa and some neighboring ethnic groups is the obsession with Bori and Dodo spirits, which manifest themselves through the media, women and men, who through music in trance or Ecstasy. The possessed person bears the attribute of his spirit and is his "horse" through which the latter expresses his wishes. In Sudan women cultivate the tsar cult . The cult, which was also widespread in Egypt, was banned there.

- The Cross River Basin and Cameroon Grasslands

The area is inhabited by many Semibantu peoples. The grassland Semibantu have absorbed numerous cultural influences from Sudan, while the woodland Semibantu have remained much more original.

-

Grassland Semibantu: The three main groups are Tikar , Bamum and Bamileke , plus the Bani named after the river of the same name , all of whom are plant farmers.

In religion, the cult of the ancestral or chief's skull, which is partly associated with its own priesthood, has supplanted the cult of high god, which includes sacrifices and oracles, among other things. The high god is also partly the creator. Wandering spirits of the dead can bring disaster. -

Woodland Semibantu: Especially the Ibibio and Ekoi groups . They are also planters.

The high god plays a central role in their religion, with the individual ideas differing considerably among the strongly fragmented tribes. An ancestor cult with sacrificial altars is also very pronounced. The dead ( Ekpo ) live underground and sometimes go around. Some ethnic groups have a pronounced individual and clan totemism with taboos and the idea of spirits of the dead that have become animals ( Ndem ). The belief in wizards and witches is widespread. The life force ideology shows itself in the belief that when one comes into possession of parts of a person, one gains power over him.

- The East Atlantic Province

It is also known as the Upper Guinea Province. According to Baumann, this is where “ancient Nigritian substrate culture mixes with ancient Mediterranean and Young Sudanese layers”. The often excellent soils (e.g. Niger Delta ) with a hot, humid tropical climate have led to distinctive rural cultures. The ethnic structure, for which monarchical states are typical everywhere, comprises four main groups, for which, apart from the first and the ethnic groups living on the Guinea coast, farming without large livestock farming is typical (hunting hardly plays a role):

- the lagoon people (especially fishing)

- the Anyi - Akan group with some ancient kingdoms. The Ashanti (Asante) are best known here .

- the ewe ; they are fishermen too

- the Yoruba , Igbo , Idjo , the Kingdom of Benin and the Edo (also fishermen).

Religion: Heaven and earth deities as well as a high god who usually appears as creator dominate the beliefs of the 2nd to 4th group.

All in all, in this area you can find pretty much all known forms of expression of the African world of faith, i.e. belief in supernatural powers with an animistic primer, belief in magic with fetishes, amulets, jujus, talismans. The boundaries between souls, spirits and deities are blurred, because they all have the supernatural forces in common, but a distinction is made according to function and motivation (high or low, good or bad, etc.).

Belief in the beneficial and beneficial activities of the dead souls or spirits is the basis of the ancestor cult, which here forms the highest expression of religious sentiment. Sacrifice is common. A totemism can still be found among the Anyi-Akan, the Ewe and Edo. A snake cult in connection with ancestor worship is widespread, especially among the Ashanti and Dahome .

The belief in the ability of humans to transform into animals is also widespread. In addition, a myriad of fairytale-like, partly useful, partly harmful beings such as bush demons, giants, elves and gnomes appear. There are fertility cults , some of them phallically oriented, everywhere .

The Yoruba religion is particularly important for Africa today. Interesting here is the 401-strong, genealogically ordered Yoruba pantheon, which, with its warring gods, reveals its origins from the archaic high cultures and whose multicolored myths report the gods' stay on earth, but nothing about the high god. The Yoruba religion is based on a four-tier hierarchy of spiritual beings. The Supreme Being is Olodumare or Olorun stands above a hierarchical order of lower deities, to which temples and shrines are assigned, while the High God is only invoked. Ancestor worship and oracles like the Ifa oracle are central. The Oro and Egungun mask dances serve to worship the dead. Shrines of nature symbols such as rocks, trees, rivers, etc., with cult images can be found everywhere. The cosmos consists of the world of human beings on this side and the other world of spirits, into which one can, however, come through dreams and visions. The orisha myths, which refer to individual deities and often develop local forms in which social functions such as marriage, etc. are represented, are essential . The main god also appears in local differences. In Oyo, the storm god Shango was the main deity, in Benin the Edo religion developed in parallel . The priests, necromancers and healers of the Yoruba religion are called Babalawo .

- The West Atlantic Province

It includes the coastal area and the nearby hinterland from the northern border of Senegal to the center of the Ivory Coast . In terms of landscape and climate, there are mangroves and coastal forests , savannahs and tropical jungles. The climate is influenced by the trade wind.

According to Baumann, there are 77 ethnic groups, including the Wolof , Dyola , Temne , Mende , Lebu and numerous others. The basis of the economy is field cultivation as chopping with slash and burn, and here and there gardening (with the Dyola and Flup ). Fishing is very important, as is hunting. From a social point of view, the kingship, which appears sacred, played an important role among the Wolof, who were heavily divided into classes. In addition, there were numerous small principalities, especially among the Dyola, where the king was also the priest of the protective demon of his area. There are chiefs elsewhere.

Religion: The belief in a heaven and creator god is more or less strong. In addition, there are earth and water gods as well as local demons, depending on their lifestyle. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, belief in the hereafter plays a role in a dead land in a place that is difficult for the soul to reach (mountain, seabed, etc.). Reincarnation and renewal processes of the soul occur. The most important is generally the cult of the ancestors, with the ancestors interfering in worldly matters and expecting sacrifices. This goes hand in hand with the secret societies known as Poro for men ( Bondo for women ). The most important cult object is the mask, which represents the Bund demon and is the embodiment of all ancestral souls. Above all, admission initiations are common, in which the covenant demon devours the novice and then spits him out again, born again. During the intermediate period called the Bush Age, the initiates are spirits and are considered ancestors. In addition, numerous special societies sometimes carry out cannibalistic customs. Some totemic societies assume the ability to transform the members into the totem animal (crocodile or leopard). Above all, Islamic influences (Wolof and Lebu) can be observed alongside weaker Christian influences with some sects.

- The Oberniger Province

The Oberniger Province is bounded in the north by the Sahara and in the south by the Guinea Forest. Accordingly, the north presents itself with dry savannas, while the south becomes more and more humid and merges into the tropical rainforest via gallery forests and wet savannas. The area is traversed by Senegal and Niger, which in its delta are extremely rich in fish and offer fertile soils. Most of the time, agriculture is common, often with elaborate irrigation systems, and livestock is also farmed in the heights of the Fouta Djalon Mountains. In this area, starting from the western Sudan zone, large states were formed in the Middle Ages, including the Ghana , Songhair and Mali empires (see History of North Africa ).

Ethnically , the tribes mostly belong to the Mandes language group . These are mainly the Bambara , Soninke , Dogon , Fulbe , Malinke , Tukulor and others. Agriculture predominates in the economy, as well as cattle-breeding, especially by some Fulbe groups, especially the Bororo (also called Fulani or Peul), as well as collecting, fishing and hunting. After the collapse of the old empires, society is mostly organized into families, clan lineages and tribes, partly patrilineal, partly matrilineal.

Religion is primarily determined by a complex and extensive system of myths, including primeval, creation, culture-bringer, descent and twin myths. The Dogon and Bambara people have 5 souls with different functions and characteristics, and personal altars are erected for them, as well as the ancestors, whose worship is the focus of religion, especially the cult of the village founders. Closely connected with this is the totemic cult of the mythical clan ancestors, the Binu cult , which is dedicated to the Yeban , pre-human beings, and which is primarily a vegetation cult . Closely related to this are the numerous secret societies with masks in the cultic center (mask societies of the Dogon and Bambara). Particularly interesting here is the Holey cult , an obsession cult that also refers to pre-human beings, the Holey. These take possession of a dancer in trance and use him as a medium. The Songhai priests are famous for their magical power and make amulets, fight soul-eating witches, etc.

Islam , which is primarily regarded as the religion of the afterlife, has had an influence in this area, but with a primarily external effect (prayers, clothing, fasting, law, etc.). The holey cult and also the cult dedicated to the zin ( djinn ), in which the cults of the ancient landlords and water lords, are of far greater importance. Here, as in the entire course of the Niger, so-called féticheurs play an important role in the non-Islamic folk religion that exists everywhere parallel to Islam . They appear primarily as fortune tellers and have a strong relationship with river spirits and the goddess of the river.

- The Upper Volta Province

It describes the culturally and economically uniform area of the population groups in the center of the Niger Arc in Upper Volta and the adjacent sub-areas of the neighboring states. The similar environment (Trockenwald- and humid savannah) has the rainfed result with herd livestock and subsidiary hunting, to fishing and gathering. The long-established population was largely able to preserve its culture despite being layered by the culture of the pre-Islamic founders of the state and by Islam itself. An ethnic breakdown is hardly possible because of the large number of peoples and their strong intermingling and interlinking of the settlement areas. A rough distinction is therefore made (whereby ethnic and linguistic groups are not congruent):

- Northern group: Mainly the old Songhai people

- Eastern group: Numerous heterogeneous small groups

- Central group: Gurunsi , Lyela and others

- Northwest group such as Bobo and Lobi language group

- Southwest group: mainly Senufo and Kulango .

- Southeast group: Refuge for ancient peoples.

- Togo remnants.

The most important major social structure is the lineage clan, which is linked by a common ancestor. The structure is strictly patriarchal, women are not capable of cult. There are councils of elders based on the principle of seniority in the higher-level associations.

Religion: The elder of the clan also acts as a priest in the central ancestral cult and is called the earth lord. Superordinate and often esoteric cult associations perform initiation rites. Earth cults are common. Two impersonal, but not otiose, ritually revered gods, partly functioning as rain gods, as representatives of heaven and earth are the starting point of a partly layered cosmogony . The human distance of the high and heaven gods makes mediators necessary, as the wife of the high god, the earth goddess, as well as the ancestors appear. The earth cult also contains a bush cult as a hunting substrate in which the bush god still plays a role as lord of the game, who also has to be invoked for hunting luck and punishes sacrilege, with bush spirits acting as gamekeepers. Bush sanctuaries are dedicated to him, which also take on a totemic character and can thus be transferred to the clan. The idea of the outer soul ( alter ego ) also emerges, which is shared with an animal, whose fate then affects it back. In addition to this earth and sky cult, there is an ancestral cult on the basis of complex ideas of soul and reincarnation with a dualistic basic structure (body / life force - spirit / soul). Magic, for example through rainmakers, is imparted through the ancestors. Matrilinear inherited fortune-telling, also by medicine men, is widespread, as is the fear of witches (they eat souls and drink life force).

The traditional ideas were not significantly influenced by the state-building cultural classes. The Islam has been able to put before the colonial period only in the Songhai- and Fulani States Foot. Christianity has had little success.

Group III: Old, predominantly Islamic civilized peoples of North and Northeast Africa

In these peoples, Islam has mostly dominated for centuries, especially since the wave of Arab immigration from the Nile Valley that began in the 14th century, and it has largely displaced the old forms of religion, of which, however, numerous remains and syncretistic phenomena can still be observed.

- Northeast Sudan

In the north the thorn savannah of the Sahel zone , otherwise characteristic of the Sudan zone . Further south there are good prerequisites for cattle nomads with transition to the rain-green savannah, further south beyond the 10th degree of latitude, because of the tse-tse fly, it is no longer possible to keep livestock, but instead farming. The 23rd parallel forms the southern border of the Islam zone. The local caravan routes were the origin of the later local kingdoms. Accordingly, there are four large population groups, all of which are more or less Islamized:

- Ethnic groups with state, sometimes even Christian traditions such as Kanem-Bornu and Dar Fur : Kanembu , Bulala , Fur , Dadjo and others. a. The Kanembu have been Islamized for a long time. In addition to Islam, the Kotoko also practice belief in nature spirits, phenomena of possession, magic and totemic rites as remnants of the old Sao culture . The Fur still know an ancestral cult, stone, fertility and snake cults. They have the idea of nature spirits, the transformation of humans into animals and magical practices, similar to the wadai . The former inhabitants of Baguirmi still practice the margai cult, performed by priestesses in a trance, in addition to agrarian rites and believe in the earth lord and lord of the river.

- Arabs and Arabized tribes between the Red Sea and Lake Chad : All Sudan Arabs are Muslims; they train religious brotherhoods. They are mostly semi-nomadic camel and cattle breeders like the Kababish of Wadi Howar , plus transhumance farmers, for whom farming is more important than keeping livestock. The fields are often on the unused land of the neighboring non-Arab Africans, whose landlord sometimes receives a small tribute. The ancestors are important for the position in the clan. Here and there cult sites for nature spirits are preserved, amulets are popular. Belief in witches and the fear of the Evil Eye as well as numerous magical practices are known that do not necessarily go back to contact with the surrounding population, but may have beenbrought back from Arabiaas remnants of the Altarabic religion .

- Hill tribes: Hadjerai , Nuba . The Islamization is barely pronounced. Their religious life is dominated by the spirit cult, because spirits are mediators between man and God. They are being sacrificed. There are obsession phenomena. Rainmakers play a major role with the Nuba. There are also ancestral and spirit cults (partly with obsession phenomena), fear of witches, and magic.

- Shari - Logone peoples: Massa , Sara -Laka group. Islamization is hardly pronounced. The agrarian rites of the Lord of the Earth are of the greatest importance. One believes in river spirits, family and twin spirits and practices an ancestral cult with sacrifices. Belief in witches, oracles and ordals are important.

- Sahara and Sahel zone

The peoples who live there partly as nomads and semi-nomads, partly as oasis farmers are Islamized throughout. There are six main groups, of which only the first three are relevant:

-

The black African populations: The bale (Bideyat) living mainly in Ennedi , the Tubu (Sahara: Daza; Sahel: Kreda) living between the Tibesti and Lake Chad and the Kanuri of the Fachi and Bilma oases . The Baele have best preserved their pre-Islamic beliefs of all peoples Sahara. With them an ancestor cult is still alive, which refers to the mythical founder of sound, at whose seat (rocks etc.) sacrifices are made and requests are made. Above it stands an otious god edo who is not identical with Allah and to whom there is no sacrifice. Life comes from him and he takes it again.

The Tubu also know an ancestral cult, albeit Islamized, as well as pre-Islamic agrarian rites, magical practices, geomancy and ordal as well as remnants of a sun cult . According to their belief, man has two souls. The soul of the dead strokes the graves at which sacrifices are made. The dream soul, on the other hand, wanders around in dreams; They can catch evil looks. Overall, a particularly large number of pre-Islamic customs have been preserved among the Tubu, and in the Tibesti there are numerous stone circles that go back to pre-Islamic places of worship where sacrifices are made to this day. Belief in spirits is also widespread.

-

Sahara Berbers: Tuareg and Moors .

- The Berbers , although they are entirely Islamic, have numerous pre-Islamic customs such as sowing and harvesting customs, when the Berber tribes in the Atlas Mountains march across the fields in solemn parades with dancing, music and prayers and thus pay homage to the Earth Mother . They regard the earth as a divine bride and the rain as a husband, which constantly penetrates them. Other fertility rites are common, and the divine primal power is accordingly feminine. Occasionally, there are orgiastic copulation ceremonies. Summoning dances take place near springs, fig trees, and cork oaks, which are believed to be the seat of earth demons. Even before the Islamic Ashura festival , the farmers make sacrifices, light fires in the mountains and dance around the flames, an ancient Mediterranean rite (not unlike the European solstice fires ). Even the pre-Islamic role of women as priestesses of an earthly mother goddess has survived in remnants, and some women are still considered sorceresses today, and even apart from large settlements there are even female saints ( Taguramt ). Here Islam is partly just a varnish, under which old customs have been preserved, and nature remains populated by powerful demons and spirits that have to be appeased. Old sacrificial sites are still frequented. The role of the old magical priests has now been taken over by the marabouts (Berber: Aguram ), who are sometimes considered saints, and they are indispensable as mediators between this world and the beyond, because they practice the old pre-Islamic magic under Islamic whitewash. As snake charmers, they still practice ecstasy here and there. They are therefore anathema to most orthodox Islamic scholars.