Garri Kimowitsch Kasparov

|

|

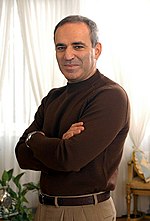

| Garry Kasparov (2007) |

|

| Surname | Garri Kimowitsch Kasparov |

| Association |

|

| Born | April 13, 1963 Baku , AsSSR |

| title |

International Master (1979) Grand Master (1980) |

| World Champion | 1985-2000 |

| Current Elo rating | 2812 (February 2021) |

| Best Elo rating | 2851 (July 1999) |

| Tab at the FIDE (English) | |

Garri Kimowitsch Kasparov ( Russian Га́рри Ки́мович Каспа́ров , scientific transliteration Garri Kimovič Kasparov , born April 13, 1963 as Garik Weinstein in Baku ) is a Soviet or Russian world chess champion and chess author of Armenian and Jewish descent. He grew up in the Azerbaijani SSR . In 2014 he accepted Croatian citizenship.

Kasparov was the official world champion of the FIDE world chess federation from 1985 to 1993 . After separating from this organization in a dispute in 1993, he remained the holder of this title recognized by most of the chess world until 2000. On March 10, 2005, Kasparov, at the top of the world rankings, officially ended his professional chess career. He is considered one of the strongest players in chess history.

Kasparov has been a Russian opposition activist since retiring from chess. He was chairman of the United Citizens' Front and founded, among other things, the opposition alliance " The Other Russia ", which was not allowed to participate in the 2007/2008 parliamentary and presidential elections on the grounds that it was not a party. On December 13, 2008, he founded the extra-parliamentary opposition movement Solidarnost together with Boris Nemtsov .

Chess career

Childhood and adolescence

Kasparov was born as Garik Weinstein in Baku on April 13, 1963 . His mother Klara Schagenovna Kasparjan (1937-2020) was Armenian and came from Nagorno-Karabakh , an Armenian-populated enclave in Azerbaijan. She was a music teacher. His Jewish father Kim Moissejewitsch Weinstein (1931–1971) played the violin and was the brother of the Azerbaijani composer Leonid Weinstein . Both parents had a college education and from an early age let their son enjoy an atmosphere of intellect and education.

When he was five years old, Kasparov, whose mother tongue is Russian, learned the rules of chess from his father . In Kasparov's own words: “I had never played chess before, but I watched intently how they struggled [...] and finally gave up in resignation. The next morning I showed them the move that led to the solution. ”From the age of seven, Garik Weinstein received regular chess lessons in the Palace of the Young Pioneers in Baku.

In 1971, his father died of malignant lymphoma at the age of 39 . When Kasparov was twelve years old, his mother changed his name from Weinstein to Kasparow, the Russified variant of her maiden name Kasparjan ( Armenian Գասպարյան).

At the age of ten he entered the chess school of three-time world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik . He became Kasparov's chess foster father and at the same time a role model, trainer and critic. At the age of 15 Kasparov took on a kind of assistant function in the chess school and received an honorary certificate from the President of the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijani SSR . In 1976 and 1977 he was junior champion of the Soviet Union .

In 1979 Kasparov received the title of International Master . As early as 1980, the then 17-year-old was awarded the title of Grand Master , and in the same year he won the Junior World Championship in Dortmund . The influential Azerbaijani politician Heydər Əliyev promoted Kasparov from 1979.

The way to the world championship

The Russian Anatoli Karpov replaced the American Bobby Fischer as world chess champion in 1975 . The Soviet chess federation expected that the other Soviet chess grandmasters would support Karpov in his further world championship fights, but not compete against him. The young Garry Kasparov opposed this. He refused to provide his chess analysis to Anatoly Karpov for his 1981 world championship match against Viktor Korchnoi . In order to prevent Kasparov in the subsequent world championship cycle from challenging world champion Karpov, he was refused to leave the country to play in the candidates' tournament against Viktor Korchnoi in 1983 because of alleged security concerns. With that, Kasparov was eliminated from the candidates' tournament to challenge the world champion. Korchnoi did not want to go through without a fight and therefore suggested a new match against Kasparov. This match came about and was won convincingly by Kasparov. This cleared the way for the world championship bouts against Anatoly Karpov.

World championship fights

FIDE world championships

Kasparov convincingly qualified as a challenger to the world champion in the 1983/84 candidate fights. In the quarter-finals he defeated Alexander Beliavsky 6: 3 in Moscow , in the semi-finals in London Viktor Korchnoi 7: 4 and in the final in Vilnius ex-world champion Vasily Smyslow 8.5: 4.5. Kasparov's competition against Anatoly Karpov for the 1984 World Chess Championship began on September 10, 1984 in Moscow. The game was played according to the mode that had been in use since the 1978 World Cup: those who won six games first should become world champions, draws did not count. After Karpov took the lead with 4-0 wins, Kasparov changed his competition tactics. Instead of continuing to attack impetuously and unsuccessfully, he played for a draw and wanted to hold out as long as possible. Karpov managed to win the fifth after a long series of draws, but then the world champion showed signs of exhaustion. He lost more and more physically and mentally, lost 11 kilograms and had to be hospitalized several times while Kasparov remained fit.

Kasparov shortened the deficit to 3-5 within a few games, before the match on February 15, 1985 after 48 games with over 300 hours of play was canceled without a result. The cancellation took place under circumstances that have not yet been clarified by the then FIDE President Florencio Campomanes , who officially justified it with “consideration for the health of both players”. In his 1987 autobiography Politische Partie , Kasparov accused Campomanes, his adversary Karpov and those responsible for chess in the USSR of plotting against him. At the same time, however, he admitted that his chances of winning the title had increased significantly due to the unsuccessful termination. FIDE scheduled a repetition of the competition under a different mode in Moscow in October 1985. The number of games was limited to 24, the winner should be whoever scored 12.5 points first, including draws. A result of 12:12 should count as the title defense of the world champion. In this second world championship fight in 1985 Kasparov won 13:11. On November 9, 1985, he became the 13th and, at the age of 22, the youngest world champion in chess history.

Garry Kasparov defended his world title in three further encounters with Karpov: In 1986 there was a revenge competition in London (the first 12 games) and Leningrad (the last 12 games) after FIDE surprisingly reintroduced the world champions' revenge privilege , which had been abolished in 1963 . Kasparov defended his title with 12.5: 11.5. In 1987 the two opponents played their competition in Seville : With a win in the 24th game, Kasparov managed a 12:12 and the tie defended the title. In 1990 Karpov was again qualified through the candidate fights. Kasparov won the competition , half in New York City and half in Lyon , with 12.5: 11.5.

PCA World Championships

In 1993 there were disputes between Kasparov and the world chess organization FIDE , which then withdrew the world title from him. Kasparov then founded the new Professional Chess Association (PCA) with Grandmaster Nigel Short, who was qualified as a challenger, and won the PCA World Chess Championships in 1993 in London against Nigel Short (6 wins, 1 loss, 13 draws) and in 1995 in New York City against Viswanathan Anand (4 wins, 1 loss, 13 draws).

Braingames as the "successor" of the PCA

The PCA disbanded after hosting the 1995 World Chess Championship. The short-lived World Chess Council , which was also founded by Garry Kasparov in April 1998 as a successor organization , did not succeed in securing the financial framework for holding a world championship. In the following years there was neither an organization nor a sponsor who wanted to organize a world championship with Kasparov. In 2000, Braingames sponsored Kasparov's last world championship match . To the surprise of the chess world, Kasparov lost it to Vladimir Kramnik (2 defeats, 13 draws). Still, he continued to dominate many tournaments until his retirement in 2005.

The 2002 Prague Accord

In the course of efforts to unite the two competing world championships again, Kasparov, Kramnik and representatives of FIDE met in Prague in May 2002 and agreed a plan of association that provided that Kasparov and the winner of the 2001/2002 FIDE World Championship in Moscow, Ruslan Ponomarjow , was to compete in a competition, the winner of which was to meet the winner of Kramnik's world championship match with the winner of the Braingames Candidates Tournament - this was Péter Lékó . But this competition did not take place.

Competitions against chess programs

Kasparov competed several times against chess programs in competitions with tournament time . In the 1980s he had claimed that he would never be defeated by a chess program. In 1989 he played two games against the IBM- built computer Deep Thought , both of which he won. In 1996 Kasparov defeated his successor Deep Blue in a match over six games with 4: 2, but lost with the first competition game as the first world chess champion ever under tournament conditions against a chess program. The following year Kasparow lost to Deep Blue in the rematch with 2.5: 3.5. Kasparov considered the possibility that unauthorized human interference might have taken place. The allegation was based in part on the fact that IBM did not give him any insight into the computer logs at the time. However, these were published later.

In 2003 Kasparov played two competitions with tournament time against PC chess programs. The match against Deep Junior over six games ended 3: 3, the encounter with Deep Fritz over four games ended 2: 2.

Kasparov against the world

A similar media-rich event was a game " Kasparov versus the World ", which was played online in 1999 via the Internet portal MSN and in which both sides had 24 hours for each of their moves. A team made up of the four young chess talents Étienne Bacrot , Florin Felecan , Irina Krush and Elisabeth Pähtz as well as Grandmaster Daniel King analyzed and commented on the current position and suggested moves. Anyone could vote on the Internet for the next move of the world team, with the move with the most votes. The hard-fought game ended after four months on the 62nd train with the victory of Kasparov.

Kasparov's withdrawal from chess

In November 2004 Kasparov won the Russian national championship. A match planned for 2003 against the then FIDE world champion Ruslan Ponomarjow did not materialize, as did a competition planned for 2005 with the subsequent FIDE world champion Rustam Kasimjanov . Kasparov blamed FIDE for these circumstances and declared his withdrawal from professional chess after the Linares tournament on March 10, 2005. He explained that at almost 42 years of age, it was becoming increasingly difficult for him to play through a tournament without errors and that he felt that he no longer belonged. At that time, Kasparov led the world rankings with an Elo rating of 2812 points.

In May 2010, Kasparov confirmed that he had no regrets about his withdrawal.

Later games, coaching and chess politics

Although Kasparov had withdrawn from tournament chess in order to devote himself to politics in Russia , he gave a few other high-profile performances, for example a simultaneous event with seven other chess and FIDE world champions at the 200-year anniversary tournament of the Zurich chess society in 2009 , where he Got 23 out of 25 points.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the 1984 World Chess Championship , Kasparov played a rapid and blitz chess match against Anatoly Karpov in Valencia in September 2009 . In rapid chess Kasparov won 3: 1 (+3 = 0 −1), in blitz chess with 6: 2 (+5 = 2 −1). In the press conference before the match, he commented on the rivalry with Karpov that had existed for many years. Despite all their differences, both would have always valued each other professionally. Their personal relationship improved in 2007 when Kasparov was imprisoned in Russia and Karpov visited him in prison.

Since February 2009 Kasparow has been working with the young Norwegian grandmaster Magnus Carlsen to support him on his way to the top of the world rankings. There were several training sessions in Moscow, Oslo, Croatia and Morocco during the year. In addition, Kasparow advised Carlsen on the tournament preparation and granted him access to his opening database. To cover the cost of the training, Carlsen sponsored NOK 4 million . In 2011, Kasparov also worked with Hikaru Nakamura for a short time . In 2009 Kasparov was awarded the title FIDE Senior Trainer.

In 2010 Kasparov supported his former rival Anatoly Karpov in his ultimately unsuccessful candidacy for the office of FIDE President. In June 2011 he set up the Kasparov Chess Foundation Europe based in Brussels. The organization wants to promote school chess in Europe.

In October 2013, Kasparov announced that he would run for FIDE President in 2014. He lost this election on August 11, 2014 with 61 votes to 110 against the previous incumbent Kirsan Ilyumschinow . On October 21, 2015, FIDE announced that Kasparov had been banned from holding offices or positions within the World Chess Federation for two years due to his attempts to buy votes in the run-up to the 2014 presidential elections. Former General Secretary Ignatius Leong , who, according to the verdict, had received half a million US dollars from Kasparov for ten plus one votes, was sentenced to the same sentence.

In July 2017 it was announced that Kasparov would receive a wildcard for the rapid chess and blitz tournament in St. Louis . The tournament, which is part of the Grand Chess Tour 2017 , had a very strong field of 10 participants, including vice world champions Karjakin , Caruana , Nakamura and Aronjan , who won the tournament. It was Kasparov's first participation in a competitive chess tournament since his retirement 12 years earlier. While Kasparov only got a sobering 8th place in rapid chess, he still achieved an even point account in blitz chess and came in fifth.

Elo development

Since Kasparov has only played blitz and rapid chess games since his resignation in 2005, which are rated separately, his rating has remained unchanged at 2812 since 2005.

|

|

Contribution to the development of chess

skill level

Kasparov's skill level is outstanding in chess history. Kasparov's Elo rating of 2851, which was achieved in 1999, was only surpassed by Magnus Carlsen in December 2012 , although the values in the world's top were increasing ( Elo inflation ). In ranking lists of retrospectively calculated historical Elo numbers , Kasparov usually came first, sometimes second behind Bobby Fischer , the world champion from 1972 to 1975.

Play style

Kasparov's chess style is dynamic and aggressive - in this he resembles his chess role model Alexander Alekhine , the world champion from 1927 to 1935 and from 1937 to 1946. Due to his aggressive chess style and his quick-tempered temperament, Kasparov was known in the chess world as the "Beast of Baku" designated.

Kasparov was also known for his excellent preparation for duels - here he resembled his second role model Mikhail Botvinnik , the world champion from 1948 to 1957, from 1958 to 1960 and from 1961 to 1963.

Opening preparation

Kasparov's knowledge of opening theory was superior to comparable knowledge of all other contemporary grandmasters and former world champions. As a result, he often achieved advantageous positions in his games above average after the opening. Among other things, he was considered one of the best experts on the Najdorf variant in the Sicilian Defense .

An example of Kasparov's preparation for the opening is the Kasparov Gambit , which he developed himself and which brought him an important victory in the 1985 World Championship match against Anatoly Karpov . In his world championship fights against Karpow , a theoretical dispute lasting over many games developed in several openings, including the Grünfeld-Indian Defense , which contributed a lot to the further development of the variants. In addition, Kasparov occasionally used less popular openings to surprise his opponents. In 1995 he defeated Viswanathan Anand with the almost forgotten Evans Gambit in just 25 moves. In the world championship fight against Wladimir Kramnik in 2000, however, he did not succeed in finding a promising variant against the Berlin defense of the Spanish game , which turned out to be a decisive factor in his defeat.

In his last tournament in Linares in 2005 he played with Black against Rustam Kasimjanov in the Merano system of the Slavic Defense 1. d2 – d4 d7 – d5 2. c2 – c4 c7 – c6 3. Nb1 – c3 Ng8 – f6 4. e2 – e3 e7 –E6 5. Ng1 – f3 Nb8 – d7 6. Bf1 – d3 d5xc4 7. Bd3xc4 b7 – b5 after the known moves 8. Bc4 – d3 Bc8 – b7 9. 0–0 a7 – a6 10. e3 – e4 c6 – c5 11. d4 – d5 Qd8 – c7 12. d5xe6 f7xe6 13. Bd3 – c2 c5 – c4 14. Nf3 – d4 Nd7 – c5 15. Bc1 – e3 e6 – e5 16. Nd4 – f3 Bf8 – e7 17. Nf3 – g5 den new move 17.… 0–0! that he had prepared together with his second Yuri Dochojan and with the support of the Junior chess program . In Informator No. 93, this train was recognized as the best innovation .

Contributions to chess literature

Kasparov wrote numerous chess books. From 2003 to 2006 he published a five-volume series of books on the history of the world chess champions before him under the title My great Predecessors , the German translation of which was published in seven volumes under the title Meine große Vorkampfs . He also wrote under the overall title Kasparov on Modern Chess, first with Revolution in the 70s, a volume on the development of various opening systems, then two volumes ( Kasparov vs Karpov 1975-1985 and Kasparov vs Karpov 1986-1987 ) about the first four world championship fights against Anatoly Karpov .

Game examples

- Lautier - Kasparow, Linares 1994

- Deep Blue - Kasparow, Philadelphia 1996, 1st competition game

- Kasparow - Topalow, Wijk aan Zee 1999

List of tournament results (excluding rapid and blitz chess)

| competition | place | Result / score | rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | |||

| USSR Youth Championship | Vilnius | 5.5 / 9 (+4 = 3 −2) | 7-10 place |

| 1976 | |||

| USSR Youth Championship | Tbilisi | 7/9 (+5 = 4 −0) | 1st place |

| Regional championship tournament of the AsSSR | Baku | 6.5 / 13 (+4 = 5 −4) | |

| Cadet World Championship (today: U18) | Wattignies | 6/9 (+5 = 2 −2) | 3rd-6th place |

| 1977 | |||

| USSR Youth Championship | Riga | 8.5 / 9 | 1st place |

| USSR Youth Spartakiad (team tournament) | Leningrad | 4/7 (+3 = 2 −2) | on the 1st board for Azerbaijan |

| Cadet World Championship (today: U16) | Cagnes-sur-Mer | 8.5 / 11 (+7 = 3 −1) | 3rd place |

| 1978 | |||

| Sokolski Memorial Tournament | Minsk | 13/17 (+11 = 4 −2) | 1st place |

| Semi-finals (Otborotschnij) for the USSR championship | Daugavpils | 9/13 (+6 = 6 −1) | 1st place |

| 46th USSR Championship | Tbilisi | 8.5 / 17 (+4 = 9 −4) | 9th place |

| 1979 | |||

| International tournament | Banja Luka | 11.5 / 15 | 1st place |

| USSR Spartakiad (team tournament) | Moscow | 5.5 / 8 | on the 2nd board for Azerbaijan |

| 47th USSR Championship | Minsk | 10/17 | 3rd to 4th place |

| 1980 | |||

| International tournament | Baku | 11.5 / 15 | 1st place |

| Youth World Championship (today: U20) | Dortmund | 10.5 / 13 | 1st place |

| Chess Olympiad | Malta | 9.5 / 12 | on the 4th board for the USSR |

| European team championship | Skara | 5.5 / 6 | on the 8th board for the USSR |

| 1981 | |||

| Pravda National Team Tournament | Moscow | 4/6 | on the 1st board for the USSR youth team |

| International tournament | Moscow | 7.5 / 13 | 2-3 place |

| USSR Spartakiad (team tournament) | Moscow | 6.5 / 9 | on the 1st board for Azerbaijan |

| Youth team world championship (U26) | Graz | 9/10 | on the 1st board for the USSR |

| International tournament | Tilburg | 5.5 / 11 | 6-8 place |

| 48th USSR Championship | Frunze | 12.5 / 17 | 1st – 2nd place |

| 1982 | |||

| International tournament | Bugojno | 9.5 / 13 | 1st place |

| USSR championship for club teams | Kislovodsk | 4/7 | on the 2nd board for Spartak |

| FIDE interzonal tournament | Moscow | 10/13 | 1st place |

| Chess Olympiad | Lucerne | 8.5 / 11 | on the 2nd board for the USSR |

| 1983 | |||

| USSR Spartakiad (team tournament) | Moscow | 1/2 | on the 1st board for Azerbaijan |

| Quarterfinals of the candidates: competition with Alexander Beliavsky | Moscow | 6/9 | 6: 3 victory for Kasparov |

| International tournament | Nikšić | 11/14 | 1st place |

| Semi-finals of the candidates: competition with Viktor Korchnoi | London | 7/11 | 7-4 victory for Kasparov |

| 1984 | |||

| Final of the candidates: competition with Vasily Smyslow | Vilnius | 8.5 / 13 | 8.5: 4.5 victory for Kasparov |

| Team tournament USSR against the rest of the world | London | 2.5 / 4 | on the 2nd board for the USSR (opponent in all games was Jan Timman ) |

| Competition for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov | Moscow | 23/48 (+3 = 40 −5) | Competition canceled without result |

| 1985 | |||

| Competition with Robert Huebner | Hamburg | 4.5 / 6 | 4.5: 1.5 victory for Kasparov |

| Competition with Ulf Andersson | Belgrade | 4/6 | 4-2 victory for Kasparov |

| Competition for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov | Moscow | 13/24 (+5 = 16 −3) | 13:11 victory for Kasparov |

| Competition with Jan Timman | Hilversum | 4/6 (+3 = 2 −1) | 4-2 victory for Kasparov |

| 1986 | |||

| Competition with Tony Miles | Basel | 5.5 / 6 (+5 = 1 −0) | 5.5: 0.5 victory for Kasparov |

| Competition for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov | London and Leningrad | 12.5 / 24 (+5 = 15 −4) | 12.5: 11.5 victory for Kasparov |

| Chess Olympiad | Dubai | 8.5 / 11 | on the 1st board for the USSR |

| International tournament | Brussels | 7.5 / 10 | 1st place |

| 1987 | |||

| International tournament | Brussels | 8.5 / 11 | 1st – 2nd place |

| Competition for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov | Seville | 12/24 (+4 = 16 −4) | A 12:12 tie, which means that Kasparov remained world champion |

| 1988 | |||

| International tournament | Amsterdam | 9/12 | 1st place in front of Karpov |

| International tournament | Belfort | 11.5 / 15 | 1st place ahead of Karpow and Jaan Ehlvest |

| 55th USSR Championship | Moscow | 11.5 / 17 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Reykjavík | 11/15 | 1st place |

| Chess Olympiad | Thessaloniki | 8.5 / 10 | on the 1st board for the USSR |

| 1989 | |||

| International tournament | Barcelona | 11/16 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Skellefteå | 9.5 / 15 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Tilburg | 12/14 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Belgrade | 9.5 / 11 | 1st place |

| 1990 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 8/11 | 1st place |

| Competition with Lev Psachis | Murcia | 5/6 (+4 = 2 −0) | 5-1 win for Kasparov |

| Competition for the world championship against Anatoly Karpov | New York and Lyon | 12.5 / 24 (+4 = 17 −3) | 12.5: 11.5 victory for Kasparov |

| 1991 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 9/13 | 2nd place |

| International tournament | Amsterdam | 5.5 / 9 | 3rd to 4th place |

| International tournament | Tilburg | 10/14 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Reggio nell'Emilia | 5.5 / 9 | 2-3 place |

| 1992 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 10/13 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Dortmund | 6/9 | 1st – 2nd place |

| Chess Olympiad | Manila | 8.5 / 10 (+7 = 3 −0) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| European team championship | Debrecen | 6/8 (4-0 = 4) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| 1993 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 10/13 | 1st place |

| French team championship finals | Auxerre | 3/4 (2-0 = 2) | on the 1st board |

| Competition for the world championship (hosted by PCA) against Nigel Short | London | 12.5 / 20 (+6 = 13 −1) | 12.5: 7.5 victory for Kasparov |

| 1994 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 8.5 / 13 | 2-3 place |

| International tournament | Amsterdam | 4/6 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Novgorod | 7/10 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Horgen | 8.5 / 11 | 1st place |

| Final round of the European Cup for club teams | Lyon | 1.5 / 3 (+1 = 1 −1) | on the 1st board for Bosna Sarajevo |

| Chess Olympiad | Moscow | 6.5 / 10 (+4 = 5 −1) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| 1995 | |||

| Valley memorial tournament | Riga | 7.5 / 10 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Amsterdam | 3.5 / 6 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Novgorod | 6.5 / 9 | 1st place |

| Competition for the world championship (host PCA) against Viswanathan Anand | new York | 10.5 / 18 (+4 = 13 −1) | 10.5: 7.5 victory for Kasparov |

| International tournament | Horgen | 4.5 / 9 | 5th place |

| Final round of the European Cup for club teams | Ljubljana | 1.5 / 2 (+1 = 1 −0) | on the 1st board for Bosna Sarajevo |

| 1996 | |||

| Competition with the IBM computer Deep Blue | Philadelphia | 4/6 (+3 = 2 −1) | 4-2 victory for Kasparov |

| International tournament | Amsterdam | 6.5 / 9 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Dos Hermanas | 5.5 / 9 | 3rd to 4th place |

| Chess Olympiad | Yerevan | 7/9 (+5 = 4 −0) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| International tournament | Las Palmas | 6.5 / 10 | 1st place |

| 1997 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 8.5 / 11 | 1st place |

| Competition with the IBM computer Deep Blue | new York | 2.5 / 6 (+1 = 3 −2) | 3.5: 2.5 win for Deep Blue |

| International tournament | Novgorod | 6.5 / 10 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Tilburg | 8/11 | 1st place |

| 1998 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 7.5 / 14 | 3rd to 4th place |

| Competition with Jan Timman | Prague | 4/6 | 4-2 victory for Kasparov |

| 1999 | |||

| International tournament | Wijk aan Zee | 10/13 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Linares | 10.5 / 14 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Sarajevo | 7/9 | 1st place |

| 2000 | |||

| International tournament | Wijk aan Zee | 9.5 / 13 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Linares | 6/10 | 1st – 2nd place |

| International tournament | Sarajevo | 8.5 / 11 | 1st place |

| Competition for the world championship against Vladimir Kramnik | London | 6.5 / 15 (+0 = 13 −2) | 8.5: 6.5 victory for Kramnik |

| 2001 | |||

| International tournament | Wijk aan Zee | 9/13 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Linares | 7.5 / 10 | 1st place |

| International tournament | Astana | 7/10 | 1st place |

| Botvinnik memorial tournament, held as a competition with Vladimir Kramnik | Moscow | 2/4 (+0 = 4 −0) | 2-2 draw after tournament games, rapid chess and blitz games were still played. |

| 2002 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 8/12 | 1st place |

| Chess Olympiad | Bled | 7.5 / 9 (+6 = 3 −0) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| 2003 | |||

| Competition with the Deep Junior computer | new York | 3/6 (+1 = 4 −1) | 3: 3 tie |

| International tournament | Linares | 6.5 / 12 | 3rd to 4th place |

| Final round of the European Cup for club teams | Rethymno | 4.5 / 6 (+4 = 1 −1) | on the 1st board for Ladya Kazan-1000 |

| Competition with the Deep Fritz computer | new York | 2/4 (+1 = 2 −1) | 2-2 draw |

| 2004 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 6.5 / 12 | 2-3 place |

| Team tournament Russia against the rest of the world | Moscow | 3.5 / 6 (+1 = 5 −0) | on the 1st board for Russia |

| Final round of the European Cup for club teams | Izmir | 3.5 / 7 (+1 = 5 −1) | on the 1st board for Max Ven Ekaterinburg |

| 57th Championship of Russia | Moscow | 7.5 / 10 (+5 = 5 −0) | 1st place |

| 2005 | |||

| International tournament | Linares | 8/12 | 1st – 2nd place |

Economic activity

Kasparov licensed several chess programs from various companies that were marketed under his name:

- Kasparov's Gambit (1993)

- Virtual Kasparov (2001)

- Kasparov Chessmate (2003)

- Garry Kasparov teaches chess (2005)

In 1995 he founded Kasparov Consultancy together with his long-time manager Andrew Page and the former Air Europe director Peter Smith . The focus was on consulting for joint ventures of Russian and other European companies in the field of aviation .

As a long-term advertising partner of the Center for Microelectronics Dresden , he successfully campaigned for the 2008 Chess Olympiad to take place in Dresden .

Chronology criticism

In addition to preparing for chess tournaments, he devoted himself to many other interests during his active career. Among other things, he is interested in history. According to his own statements, he noticed inconsistencies in the scientifically accepted chronology . He soon became a supporter and financial supporter of the chronological criticism in Russia, which is not recognized in specialist circles, and has also written articles on it.

Political commitment

Democratization

In 1984 Kasparov joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union . He left this again in 1990 and took part in the founding of the Democratic Party , of which he became deputy chairman. A year later he resigned from this party after disputes over the program.

In 1993, Kasparov was involved in the creation of the Party of Russia Election . In the Russian presidential elections in 1996 , he campaigned for the re-election of Boris Yeltsin .

From 1999 Kasparov published a number of political commentaries in US newspapers, such as The Wall Street Journal , from 2004 as "contributing editor" of the newspaper, in which he praised American politics and criticized Russian politics. In 2006, the website of the neo-conservative American organization led Center for Security Policy Kasparov as a member of its Advisory Board National Security Advisory Council (NSAC). In early April 2007 there were public reports of this membership. But in the same month Kasparov described it as a “bureaucratic curiosity” and denied ever having worked for the organization. Shortly thereafter, his name was removed from the NSAC membership list.

Activities in Russia

After retiring from professional chess in March 2005, Kasparov announced that he would now devote his time to politics and writing. He founded the United Citizens Front and became a member of the government-critical party federation The Other Russia .

During Vladimir Putin's first term as President of Russia , Kasparov was involved in Russian politics and made a name for himself as a critic of the Russian President. He became co-founder and chairman of the " Committee 2008: Free Elections " founded in January 2004 , which had set itself the goal of preventing Vladimir Putin from holding another term. In April 2005, Kasparov and Russian Duma deputy Vladimir Ryschkow announced the founding of a new liberal party. During a public appearance in Moscow on April 17, 2005, a chessboard hit Kasparov on the head - a member of a youth organization close to Putin approached him, allegedly asking for an autograph on the board. Vladimir Ryzhkov stepped shortly afterwards on 23/24. April 2005 the Political Council of the Social Democratic Republican Party (RPR), but not Kasparov.

On December 16, 2006, Kasparov held a demonstration against the Putin government in Moscow, which was attended by around 2,000 people. A few days earlier the rooms of the committee headed by Kasparov had been searched in connection with this. Critical media reports in Germany had previously been caused by his discharge from Sabine Christiansen's talk show on December 10, 2006, in which he was supposed to participate via video link. Kasparov accused the Christiansen editorial team of having been unloaded under pressure from the Russian government and that technical problems had only been advanced.

In April 2007, Kasparov organized an opposition rally in Moscow. The police arrested him and his companions on the way to the unauthorized rally. A few hours later he was released on payment of a fine of 1,000 rubles (approx. 30 euros ). The philosopher André Glucksmann wrote in Le Figaro on April 25, 2007 that “the soul of Europe does not lie in a few divisions, but in the Other Russia and in Garry Kasparov”.

On May 18, 2007, the EU-Russia summit took place in Samara, Russia , to which some critics, including Kasparov, wanted to come. According to his own statements, Kasparov was detained at Moscow Airport by taking away his passport and flight ticket. He then called Russia a " police state ". German Chancellor Angela Merkel openly criticized the actions of the Russian authorities. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in October 2016 that the proceedings against Kasparov were unlawful.

In July 2007, in The Wall Street Journal , Kasparov compared the Putin government to the mafia , as described in Mario Puzo's novels .

In September 2007, Kasparov called the Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov a "bandit", whereupon the Chechen parliament filed a complaint against Kasparov for insulting.

In the same month Kasparov won a primary for the nomination as a presidential candidate of the opposition alliance The Other Russia in Moscow against Mikhail Kassyanov and the former central bank chief Viktor Gerashchenko . He received 379 out of 498 votes in the first ballot.

In October 2007, Kasparov made several appearances on well-known television programs in the United States, such as The Colbert Report , Real Time with Bill Maher and CNN Late Edition .

On November 24, 2007, a week before the parliamentary elections in Russia, Kasparov was arrested in Moscow after an authorized rally during an unauthorized protest march. Amnesty International called him a " political prisoner " and asked for his immediate release. Kasparov was released after five days in a secret location.

In the run-up to the election, Kasparov's party was considered unpopular and without a chance because the majority of the population saw the liberal economic program as a step backwards towards the privatization phase of the 1990s. On December 12, 2007, Kasparov announced his resignation as he was being severely hindered by the authorities.

On May 4, 2012, he was elected Chairman of the International Council of the Human Rights Foundation (HRF). The police arrested him on August 17, 2012 during a demonstration against the conviction of three members of the punk rock group Pussy Riot , along with around 60 other demonstrators. He was beaten and injured in the process. He was initially charged with violating the right to demonstrate and was acquitted on August 24, 2012.

In early July 2013, Kasparov said he had not returned to Russia since February 2013 because he feared that he would be investigated for political protests and that he could be prevented from leaving, and in March 2014 his website was closed for "inciting illegal acts" locked in Russia.

After the assassination of the opposition politician Boris Yefimowitsch Nemtsov in Moscow in early March 2015, Kasparov gave several interviews and, as chairman of the HRF, gave a statement to the United States Senate's subcommittee on Europe and regional security cooperation entitled “Russian aggression in Eastern Europe: Where is going Putin to Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova next? ”. Kasparov declared in August 2015: "As long as Putin is in the Kremlin, there are no opportunities for peace, because for Putin, peace means the end of his power."

Founding of Solidarnost

On December 13, 2008, Kasparov and Boris Nemtsov founded a new opposition movement under the name Solidarnost . More than 150 delegates from organizations, civil movements and parties, including the liberal Yabloko party , took part in the founding congress in a hotel near Moscow .

Kasparov called on the delegates to save the tarnished image of Russian democracy by taking joint action against the Kremlin leadership. He criticized Moscow's political leadership for having “created a complete dictatorship under the mantra of liberal principles”.

Russian media reported in advance of numerous attempts to disrupt, for example a demonstration by members of a youth organization that was pro-government.

From May 31 to June 3, 2012, Kasparov participated as a representative of the United Civic Front at the Bilderberg Conference , which took place in Chantilly , Virginia .

At the beginning of April 2013, Kasparov resigned from the Solidarnost board, but remained a member of the organization. In November 2013, Kasparov applied for Latvian citizenship because he feared political persecution in Russia. Kasparov received Croatian citizenship in February 2014 .

Awards

In 1991, Kasparov received the Keeper of the Flame Award from the neoconservative American organization Center for Security Policy for his “anti-communist resistance” and “spreading democracy”.

The news magazine Time led Kasparov in 2007 in their list of the 100 most influential people. The editor Richard Stengel called him a "hero" who leads a "lonely struggle for more democracy in Russia".

On September 19, 2007, Kasparov was awarded the newly founded Pundik Freedom Prize endowed with 100,000 crowns in Copenhagen .

In July 2008, Foreign Policy magazine ranked him 18th on its list of the World's Top 20 Public Intellectuals .

In November 2012 Kasparow received the Martin Buber plaque “for his commitment to children in the chess foundation he founded” .

On June 5, 2013 in Geneva, Kasparov received the Morris B. Abram Human Rights Award from the organization UN Watch for his non-violent commitment to human rights in Russia .

The blueprint

His book The Blueprint, written together with Peter Thiel and Max Levchin and published in 2012, diagnoses a stagnation in technological progress and calls for more extensive investments in research and development in order to increase global prosperity.

Private

When Kasparov was seven years old, his father Kim Weinstein died. Then Kasparov put his father's family name off and took his mother's name Klara Kasparova, as it sounded more Russian.

In 1990 there were anti-Armenian pogroms in Kasparov's hometown of Baku , during which he had to leave the city. After that he lived mainly in Russia , but occasionally he also visited Armenia . He has lived in New York City since 2013 .

Kasparov has at least four children and married three times. From 1985 to 1987 he was in a relationship with the 16 years older actress Marina Nejolowa . In 1987 Nejolowa gave birth to a daughter, whose paternity Kasparov denied at the time. From 1989 to June 1995 Kasparov was married to the philologist and interpreter Maria Arapova. Their daughter was born in Helsinki in April 1993 . Kasparov's second marriage, to Julia Wowk, lasted from 1996 to 2005. Their son was born in 1996. Kasparov has been married to Darija Tarasowa since 2005; this is not to be confused with the Wushu athlete of the same name . A daughter was born in December 2006. In July 2015, the couple had a son.

Trivia

In 1987, Kasparov underwent a three-day exam organized by Spiegel , which included comprised three intelligence, memory, chess and other cognitive performance tests. In an intelligence test compiled by the psychologist Eysenck for the occasion , Kasparow achieved 135 points, in Raven's progressive matrix test 123 points. He scored below average in the area of ingenuity of the Berlin intelligence structure model .

See also

literature

Works

- Checked by time. Games up to the 1984/85 World Cup . Rau, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7919-0251-2 .

- Political game . Droemer Knaur, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-426-26314-9 .

- Chess as a fight. My games and my way . Updated edition. Falken-Verlag, Niedernhausen 1989, ISBN 3-8068-0729-9 .

- I bet on victory . Rau, Düsseldorf 1989, ISBN 3-7919-0266-0 .

- I always win. World Cup 1990 . Rau, Düsseldorf 1991, ISBN 3-7919-0442-6 .

- Win in chess in 24 lessons . 3. Edition. Rau, Düsseldorf 1992, ISBN 3-7919-0265-2 .

- with Dmitri Plisetski: My Great Predecessors , Part IV (English), London 2003–2006 (about the world chess champions from Steinitz to Karpow).

- Checkmate! My first chess book . Edition Olms, Zurich, ISBN 3-283-00388-2 .

- My great champions - The most important games of the world chess champions , Volumes 1–7, “Edition Olms” publishing house, Zurich.

- Garry Kasparov on Modern Chess: Revolution in the 70's . Everyman, London 2007, ISBN 978-1-85744-422-3 .

- Garry Kasparov on Modern Chess, Part 2: Kasparov vs. Karpov 1975–1985 . Everyman, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-85744-433-9 .

- Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov, Part 1: 1973-1985 . Everyman, London 2011. ISBN 978-1-85744-672-2 .

- Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov, Part 2: 1985-1993 . Everyman, London 2013. ISBN 978-1-78194-024-2 .

- Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov, Part 3: 1993-2005 . Everyman, London 2015. ISBN 978-1-78194-183-6 .

- Garry Kasparov: Strategy and the Art of Living . Piper, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-492-04785-2 .

- Russia after Anna Politkovskaya . Passagen Verlag, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-85165-811-8 .

- Winter is coming. Why Vladimir Putin and the enemies of the Free World must be stopped . Atlantic Books, London 2015. ISBN 978-1-78239-786-1 .

- Why we have to stop Putin. The destruction of democracy in Russia and the consequences for the West , DVA, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-421-04727-4 .

- Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins . Public Affairs, New York 2017. ISBN 978-1-61039-786-5 .

Further publications

- Garry Kasparov: Chess or Machine. The royal game between creativity and programmed intelligence . In: Lettre International No. 91, Winter 2010, pp. 90-93.

Secondary literature

- Alexander Nikitin : With Kasparov to the chess summit . Sportverlag, Berlin 1991. ISBN 3-328-00394-0 .

- Igor Štohl : Garri Kasparov's best chess games . 2 volumes. Gambit Publications, London 2006.

- Robert Huebner : Kasparov's latest contribution to chess history . Journal Schach 2003 / Heft 11, pp. 24–35 and Schach 2003 / Heft 12, pp. 34–48 (Here Hübner takes a critical look at Kasparov's “ My Great Predecessors (Part I) ”).

Web links

- Garry Kasparov at the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Garri Kimowitsch Kasparow in the catalog of the German National Library

- Garri Kasparow at the World Chess Federation FIDE (English)

- Website kasparov.com (English)

- Replayable chess games by Garri Kimowitsch Kasparow on 365Chess.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kasparov celebrated his 40th birthday In: de.chessbase.com. April 14, 2003, accessed November 13, 2019.

- ↑ Garry Kasparov turns 50 In: de.chessbase.com. April 13, 2013, accessed October 24, 2019.

- ^ André Schulz Garry Kasparov on his 55th birthday In: de.chessbase.com. April 13, 2018, accessed November 13, 2019.

- ↑ Kasparov becomes Croat

- ↑ Quoted from G. Kasparow: Politische Partie (1987), p. 27.

- ↑ Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov, Part 1 (2011), p. 11.

- ↑ ChessPro, 2010

- ↑ fide.com: Top 100 Players April 2005 - Archive . Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- ↑ Chessbase , accessed March 21, 2015.

- ^ Rochade Europa 10/2009, p. 10 and p. 78-79

- ↑ Dagobert Kohlmeyer : Kasparov with a bite In: de.chessbase.com. September 23, 2009, accessed July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kasparov vs Karpov Match in Valencia 2009 In: The Week in Chess. September 24, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kasparov and Karpov to play 12 games match in Valencia In: chessdom.com. July 8, 2009, accessed July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kasparov beats Karpov in the anniversary duel In: Spiegel Online. September 25, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Video at Chessvibes.com , September 22, 2009

- ↑ Results of the rapid chess match at chessgames.com

- ↑ Results of the blitz chess match at chessgames.com

- ↑ Kasparov trains Carlsen , Chessbase.de, September 7, 2009

- ↑ Stefan Löffler: Lots of unused ideas , FAZ from December 30, 2009

- ^ Cooperation between Nakamura and Kasparov already over , Chessvibes.com, December 16, 2011

- ^ Kasparov's speech at the Russian Federation Supervisory Board meeting , May 15, 2010

- ↑ Kasparov Chess Foundation Europe launched , Chessvibes.com, June 8, 2011

- ^ Garry Kasparow 2014 FIDE Election , accessed October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Kirsan Ilyumzhinov re-elected as FIDE President . Article on FIDE.com, August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ FIDE Hands Two Year Ban to Garry Kasparov , accessed October 22, 2015

- ↑ Article on chess.com , accessed July 6, 2017.

- ↑ Results and tables , accessed on August 19, 2017.

- ↑ Numbers according to FIDE Elo lists. Data sources: fide.com (period since 2001), olimpbase.org (period 1971 to 2001)

- ↑ "I like being the beast", November 2002 Gary Kasparov el ogro de Baku Tributo a Garry Kasparov

- ↑ Kasparov - Anand to replay

- ↑ Rustam Kasimdzhanov vs Garry Kasparov , the game to replay, chessgames.com ( Java applet , English)

- ↑ Milan Bjelajac : The Most Important Novelty of Chess Informant 93 ( Memento of March 8, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (17 pages pdf; 373 kB), January 18, 2006, Chesscafe.com

- ↑ ChessPress: Junior World Team Championship in Graz - Clear victory for the Soviet team! Schach-Echo 1981, issue 18, title page.

- ^ Jan C. Roosendaal: Kasparow outclassed the competition . Schach-Echo 1988, issue 6, pages 223 to 225 (report, table, games, photo).

- ↑ Caroline Winkler: World Cup started in Belfort . Schach-Echo 1988, issue 7, pages 259 to 263 (report, table, games).

- ↑ Mobygames

- ↑ Chess master moves in . Flightglobal , February 22, 1995

- ↑ ZMD is looking forward to the Chess Olympiad ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), press release from November 2, 2004.

- ^ Mathematics of the Past

- ↑ a b c d moderator Garri Kimowitsch Kasparow ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), russland.ru , May 7, 2007

- ↑ Website, as of May 24, 2006 ( Memento from April 26, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Interview with Kasparov (Russian)

- ↑ Washington's Fifth Column in Russia - Chess Genius Garry Kasparov, his allies and his Western patrons , December 30, 2011

- ^ Sabine Christiansen Moskauer Technik , Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, December 12, 2006.

- ↑ Tagesschau of April 14, 2007: Russian police beat down demonstrators

- ↑ How many divisions does Garry Kasparov have? Translation by Perlentaucher

- ↑ Serious allegations against Putin

- ^ EU-Russia summit: Open dispute between Merkel and Putin

- ↑ Garry Kasparov wins human rights case against Russia , The Guardian , October 11, 2016

- ↑ Don Putin: To understand today's Russia, read "The Godfather" , July 29, 2007

- ^ RIA Novosti, September 25, 2007

- ↑ Kasparov is to run for the office of President of Russia , Neue Zürcher Zeitung , September 25, 2007

- ↑ Moscow: Russian opposition leader Kasparov arrested

- ↑ Amnesty demands the immediate release of Kasparov. The press, November 28, 2007

- ↑ Garry Kasparov free again. Wiener Zeitung, November 29, 2007 ( Memento from May 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The united Russians must triumph , on jungle.world, November 29, 2007

- ↑ Russian chess legend Kasparov drops presidential bid , accessed June 24, 2014.

- ↑ HRF Elects Garry Kasparov as New Chairman ( Memento from May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Human Rights Foundation , May 4, 2012

- ↑ Breaking news: Kasparov arrested and beaten at Pussy Riot trial , Chessbase , August 17, 2012

- ↑ Eli Lake: Chess Champ Garry Kasparov: 'They Were Trying to Break My Leg' , The Daily Beast , August 17, 2012

- ↑ welt.de: Kremlin critic Kasparov acquitted after protest . August 24, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ↑ Kriti Radia: Chess Grand Master Garry Kasparov Is Latest Russian to Flee , ABCNew , June 6, 2013

- ↑ Critic of the regime: Russia blocks websites of Putin critics , Spiegel, March 14, 2014

- ↑ z. B. Phil Stewart: Hopes for peaceful Russian transition fade with Nemtsov: Kasparov , Reuters , March 2, 2015

- ↑ Garri Kasparov: "Russian Aggression in Eastern Europe: Where Does Putin Go Next After Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova?" (2 pages pdf), March 4, 2015

- ↑ Putin's ideology is an outflow of hatred , RFERL, August 12, 2015, German translation: Garry Kasparov: "Putin's ideology is concentrated hate"

- ^ New Russian opposition movement founded ( Memento of February 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), tagesschau.de, December 13, 2008

- ↑ List of participants of the Bilderberg Conference 2012 ( Memento from June 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on August 3, 2016.

- ↑ Politics Kasparov leaves the Board of Directors of Solidarnost - Emigration plans? , RIA Novosti , April 7, 2013

- ↑ World chess champion applies for Latvian citizenship , Baltic Times, November 5, 2013

- ^ Garry Kasparov emigrates to Croatia

- ↑ TIME MAGAZINE NAMES GARRY KASPAROV AMONG 100 MOST INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), kasparovchessfoundation.org, May 4, 2007

- ↑ Laudation by Michael Elliott, Time

- ↑ Kasparow receives the Danish Freedom Prize for his commitment to democracy ( memento from December 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), Südtirol online, September 19, 2007

- ^ The World's Top 20 Public Intellectuals ( Memento from August 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Martin Buber plaque for Garri Kasparow , Aachener Zeitung, November 17, 2012.

- ↑ Russian Dissident & Chess Champion Wins Human Rights Award , April 8, 2013.

- ^ Information on the book ( Memento from July 11, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), Norton

- ↑ Nicholas Louis: Gary Kasparov May Lose the World Chess Title, but He's Won the Hearts of His Countrymen . People , February 4, 1985. Accessed online August 25, 2012.

- ↑ Biography on Kasparov.com, accessed April 25, 2018.

- ^ Frondienst in the rose garden - Kasparov on his relationship with Marina Nejolowa . In: Der Spiegel . No. 40 , 1987 ( online ).

- ↑ Anna Yudina: Prominent Russians Garry Kasparov. Retrieved on May 19, 2012 (English, paragraph “Family and private life”).

- ↑ Celeb Kids. Retrieved May 19, 2012 (English).

- ^ Garry Kasparov Becomes Father for the Fourth Time. Son Named After Grandfather. July 12, 2015, accessed October 17, 2017 .

- ↑ strokes of genius and blackouts . In: Der Spiegel . tape 52 , December 21, 1987 ( spiegel.de [accessed September 6, 2018]).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kasparov, Garry Kimovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Каспаров, Гарри Кимович (Russian); Kasparov, Garry (English); Kasparov, Garri Kimovič (transliteration); Weinstein, Garik |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian chess player, world chess champion and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 13, 1963 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Baku |