History of Emden

The history of Emden begins around 800, when Frisian merchants set up a trading post at the mouth of the Ems . The history of the city is inextricably linked with the port of Emden , which has been the economic basis of the community since the settlement was founded and whose ups and downs were and are linked to the economic situation of the city. Political decisions made elsewhere were often the trigger for the rise or fall of the Emden trade. Emden was shaped by Calvinism . At the time of the Eighty Years' War , many Dutch religious refugees poured into the city and made Emden a stronghold of north-western European Calvinism. With their trade connections, they brought the city at times great prosperity. Political ties with the Netherlands did not end until East Frisia fell to Prussia in 1744, and cultural ties continued for more than a century. Industrialization began in the late 19th century. Emden has been the economic center of East Frisia and the largest city in the region for centuries . In the past centuries, Emden has developed a certain special role within East Frisia, which in some cases still has an impact today. Since the Prussian district reform of 1885, the city is the only one in East Friesland to be independent .

Prehistory and early history up to the conquest by the Frisians

Due to multiple shifts of the coast, finds from prehistoric times are sparse in today's urban area of Emden. This makes a more detailed investigation of the sites, which are mainly in the area of the Emden port or in today's Dollart , difficult.

The earliest evidence of the presence of humans are two disc or core axes that were found during dredging work in the Emden harbor and that are dated to the Proto-Neolithic . Finds are missing for the next 1,000 years, which is attributed to a transgression . Further finds are only available from the funnel beaker culture, when a regression made the presence of people in today's urban area possible again.

On the other hand, there was apparently no permanent settlement of people. While the opposite left bank of the Ems in the period from 7th to 3rd / 2nd Century BC BC was already densely populated, such evidence is missing on the right bank. These early settlements were due to flooding in the 3rd / 2nd centuries. Century BC Chr. Abandoned again.

Around the birth of Christ, the Chauken took over the land again . In the area of the city of Emden, a residential area in the area of the old town as well as four settlements on Wurten on the former Emsufer on the eastern edge of the city have been verified. These settlements, too, were apparently abandoned after another period of increased flooding in the 2nd or early 3rd century AD, as was the coastal land on both sides of the Ems in the 4th / 5th century. Century was largely abandoned by humans. In the 7th century and here intensified in the second half, a repopulation of the river began to march through the Frisians after the floods had subsided. The Frisians partly used the fallow sausages from previous settlement periods, partly they built new ones. A new type of mainly trade-oriented settlements emerged, which was taken over by the Franks after the conquest of Friesland .

Development of the trading center (around 800 to 13th century)

After the integration into the Franconian Empire , Emden was in the 8th / 9th. It was founded in the 19th century as a Frisian trading post at the confluence of the Aa (Ehe) in the Eemese (Ems) and was given the name Amuthon . While older trading centers in the vicinity were founded by the local population, Emden apparently owes its existence to the general expansion of trading centers under Franconian rule on the North Sea. For Emden this meant a connection to Westphalia , as Emperor Charlemagne assigned the area around the settlement to the new diocese of Münster and the county in Emsgau gave the Westphalian Cobbons as a fief. There is only sparse evidence of Count activities by the Cobbons in Emden. The patronage of Cosmas and Damian through today's Great Church , the previous building of which is considered the oldest church in the city, can possibly be traced back to them, because Essen and Werden , as important centers of veneration for these two saints at that time, were under the control of the Cobbons.

Emden was founded as a settlement on what was then the right bank of the Ems, near the confluence of a creek , from which the city of Emden developed. For this purpose, a wurt was poured out, which has been increased over the centuries and today is 250 by 300 meters in size. This oldest settlement center in Emden lay parallel to the old river bank. It was a Langwarf on which a one- street settlement lay and which had a harbor in a tidal creek, the rest of which is now the council district. The houses on the Wurt were built using the stave construction technique (cf. stave church ) and the vast majority of them were used as living and work space, only a few were used for agriculture.

Successors to the dignity of Counts in Emsgau were the Counts of Werl around the year 900 . From this point onwards, the Emden Wurtsiedlung was generously expanded. The trading center and place of handling of goods, protected by the Franconian Empire, increased its importance as a mint considerably around the middle of the 11th century. How great the influence of the Counts von Werl was on this is unclear. On the other hand, the use of the coin rack by the Counts of Werl is certain . From the 11th century on, pennies appeared, named AMVTHON and HERIMAN (the third Count of Werl) as the mint . In 1063 Bernhard II von Werl was deprived of the count's rights in Emsgau and initially transferred to Bishop Adalbert von Bremen . Later, the Counts of Werl tried to regain ownership through a campaign against the Frisians. Here found Bernhard II. And his son Hermann death. The county constitution gradually dissolved and the Frisian municipalities strengthened, even if coins were still minted in Emden and Emden was first mentioned in 1244 as a customs post. In the year 1252, through various lords, the county was bought by the bishops of Munster, who were exposed to constant clashes with the Frisians. These ultimately resulted in a contract, the so-called Bischofsühne von Faldern , in which questions of canon law and trade were regulated. Count's rights and claims to the Emsgau were no longer mentioned here, even if they played a role until modern times and were only compensated by Count Edzard I in 1497 through payments and the granting of privileges.

Time of the chiefs (13th to early 15th centuries)

After the bishop's atonement, the power of the Münsteraner was limited to the Emden settlement, while the state community continued to grow in strength and came together in Larrelt , which at that time was not yet part of Emden . In the period that followed, the bishops no longer exercised their rights in the city themselves, but resorted to the local Abdena family, whom they made their representatives in the city. Their first representative known by name, Wiard Droste tho Emetha , had a castle built in the place for the first time around 1300. Under the rule of the chief family of the Abdenas, Emden developed into an urban settlement in the narrower sense until shortly after 1400 and was first referred to as such in 1390 by the Abdena themselves and in 1392 by the Dutch.

The Abdenas succeeded more and more in emancipating themselves from the bishops of Munster. This was also expressed in the coins they minted on their behalf. While in the middle of the 14th century these were still provided with a blessing bishop and a head of St. Paul , the Emden pfennigs of the late 14th century now showed a lion ascending to the right, the heraldic animal of Abdena and the initial W. of the minting authority Wiard (III.). His son Hisko finally coined Witten, called nova moneta de Emeda , with the heraldic lion and the indication of his full name and title of a provost and chief of Emden. Customs rights also fell to the Abdena in 1362 at the latest. From this point on, the first evidence of extensive trade relations with the place is available, according to which Emden ships and merchants visited the markets in Lübeck , Hamburg , Haren , Friesoythe and Harderwijk and were supported by Hisko with a letter of safe conduct from 1390 . Of great importance for the further economic development of Emden was the stacking requirement , which was introduced by the Abdena around 1400.

The decline of the cooperative-like state communities and the subsequent strengthening of other East Frisian chief families led to a long-lasting period of feuds between mutual alliances, in which the help of the Vitalienbrüder was used. Chief Hisko provided the pirates with shelter and a trading post in his area. The Hanseatic League , which was particularly affected by this , sent a punitive expedition to East Friesland, whereupon Hisko changed sides and handed over the city and castle of Emden to the Hanseatic troops on May 6, 1400, but was able to save his chief title in this way. After the punitive expedition and the conclusion of a settlement in Faldern Monastery , the castle was returned to Hisko.

Trade in the port continued to develop well. The Lazarushaus (first mentioned in 1403), which probably remained the only leprosy hospital in East Frisia, was probably built during this time . There, those infected with leprosy were isolated from the rest of the population in order to prevent the disease from spreading. The Lazarushaus (also called Ziekenhuis ) existed until around 1603 and was located at the Herrentor. This means that it was outside the jurisdiction of the city court at the time of its establishment and until the city's expansion in 1570. Later the building, which probably also had a chapel, presumably served as a poor house. Today there is a hotel on the site of the former Lazarus House.

In the conflict between the East Frisian chiefs, Keno II. Tom Brok succeeded in conquering the castle in Emden in 1414. Hisko had to flee to what is now the Netherlands and was only able to return to his hometown after the fall of the last tom Brok , Ocko II , where he died shortly afterwards. He was succeeded by his son Imel. Even after tom Brok was overthrown, the dispute over supremacy in East Frisia continued. Two parties were established, the Freedom League of the Seven East Friesland under the leadership of the later Count and Princely Family Cirksena and the Focko Ukenas party . This also included Imel, who once again called the Vitalien Brothers to Emden to secure his position. The up-and-coming Cirksena sensed their chance and in 1433 they linked themselves independently with the city of Hamburg. This wanted to put an end to the East Frisian toleration of pirates once and for all and therefore relied on a strong sovereign in East Frisia. With the help of the Hanseatic League, the Cirksena conquered the town and castle of Emden in 1433, where a Hanseatic garrison was established. The Hamburgers had the city provided with stronger fortifications and set up a council of citizens by upgrading the board of presumably four judges, which was comparable to that of a district. The drainage of the surrounding area was also reorganized and concentrated on Emden. The city, which was cut off from the surrounding area for a long time by the clashes of the chiefs, was able to flourish again economically during this time, as trade with the Hanseatic League was open to it.

In 1439 this garrison withdrew and the city was handed over to the Cirksena in good faith , which meant that the city formally remained in the possession of the Hamburgers and the Cirksena should initially only keep it and return it to Hamburg if requested. Tactical considerations in connection with the Hanso-Dutch War , which raged from 1438 to 1441, played a role here. Under the Cirksena the city building was formally completed, because from 1442 the city had mayors. Emden, on the other hand, did not have a proper town charter. In its place stood a series of regulations that can be traced back to the 14th century, which mainly concerned the Emden trade and regulated the access of foreign merchants. While the city council met up the koplude hus until at least 1453, evidence of its own town hall above the bridge gate on Delft can be found for the first time from 1459. In 1458 Ulrich Cirksena had the castle expanded considerably.

First residence of the Cirksena (1464 to 1561)

Ulrich Cirksena was in 1464 by Emperor Friedrich III. enfeoffed with the dignity of count over East Frisia. The solemn ceremony took place in the now defunct Franciscan monastery in Emden . Ulrich I von Ostfriesland, as he was called from then on, made the Emden Castle his main residence. The city fortifications were greatly expanded under the Cirksena. With the construction of a new sewer , Hinte , Osterhusen and Westerhusen were cut off from the sea and thus lost their function as ports. The city continued to grow during this time and since the second half of the 15th century it has expanded further and further north, where a second, the Neuer Markt , was finally created.

Because of the stacking obligation, there was an economic war with Groningen and Münster, which only ended when the Roman-German King and later Emperor Maximilian I confirmed this privilege in November 1494 and stipulated that all ships up or down the Ems downwards at the city of Emden there the defeat must hold . In the meantime, the political and economic relationships between the state and the city had become so firmly established that, after long requests and payment of the very high fees, in 1495 the emperor awarded the city the coat of arms , which is still in use today Grafenhaus shows. The top half of the coat of arms shows a virgin eagle , the heraldic figure of Cirksena.

Around 1500 Emden had around 3,000 inhabitants, making it by far the largest urban settlement in East Frisia. The city also played a leading role in the economic life of the region. Emden was the transshipment point from sea to inland shipping . The connection up the Ems to Westphalia in particular played a major role here. Down the Ems, the Emden area in the North Sea was delimited by Amsterdam , Hamburg and Dithmarschen and hardly went beyond the Wadden Sea ; In contrast, the city has not yet had an active share in the offshore trade. Shipbuilding was also not yet well developed, so that at that time the Emder were buying a large part of their ships abroad.

The second Cosmas and Damian flood on 25./26. September 1509 not only drowned several villages in the Dollart, this storm surge also created a new river bed for the Ems. Instead of flowing in a wide curve past the Emden city center, the main arm of the Ems now took the direct route to the North Sea, with only a side arm flowing past the Emden city center with the port. In the following more than three centuries, the city therefore had to struggle with the increasing siltation of the port. This did not happen overnight, so that the city could still rise to its greatest heyday in the 16th and early 17th centuries. The economic decline afterwards, however, had a natural cause in this flood disaster.

The Reformation found its way into Emden around 1520. The lead was Georg Aportanus , who was called to Emden by Count Edzard I , where he was supposed to raise his sons Enno and Johann and where he had a vicarie at the Great Church in Emden . From 1524 at the latest, he began to appear publicly in the evangelical sense. Under the protection of the count, he opposed the old-believing priesthood, and a strong contrast arose, so that he was forbidden to preach in the pulpit. Convinced of the correctness of his faith, he preached outside the city gates. The citizens of Emden then demanded his reinstatement in the church, which the followers of the old doctrine ultimately had to follow. The following period was characterized by religious liberality and political neutrality, also because the ruling counts and later princes of East Frisia were too weak to enforce a particular creed . The Reformation made Emden an important place for printing. The rebaptism of 300 adults in an anteroom of the Great Church in 1530 marked the beginning of the Anabaptist movement in north-west Germany and the Netherlands . During this time, the first Jews also settled in Emden . They are mentioned for the first time in 1558 and 1571. From 1589, the city of Emden kept a register of protection money with the names of the Emden Jews.

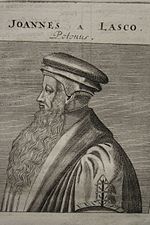

In 1543, the East Frisian Countess Anna appointed the European reformer Johannes a Lasco as the first superintendent in Emden. Lasco held this office until 1549 and was back in Emden in 1554/55. He formed a presbytery of preachers and elders in the Emden parish , founded the Coetus of the Reformed preachers in East Frisia in 1544 , co-authored the “Great Emden Catechism” in 1546 and wrote the “Small Emden Catechism” in 1554, which continued in East Frisia into the 20th century has been used. At times it looked as if Emden could become a third Reformation center alongside Geneva and Wittenberg . After a Lasco, reformers like Albert Hardenberg worked in the city .

The East Frisian Count Edzard II , who was strictly Lutheran, moved his residence from the reformed center of Emden to Aurich in 1561, which remained the seat of government in the following centuries.

The "Golden Age" (1561 to 1611)

The first religious refugees and their sympathizers left the Netherlands as early as the mid-1540s, when the Spanish kings Charles V and Philip II violently suppressed the Reformed. The city received a significant boost in its development from the freedom struggles in the Netherlands . As a result, between 1570 and 1600, up to 6000 Reformed Dutch refugees poured into Emden. The merchants and craftsmen sought refuge in the Calvinist city, which had retained political neutrality and economic independence. In addition, the tolerance of the Mennonite minority expressed a certain religious tolerance. Countess Anna supported the settlement of the refugees. Their large number led to logistical problems, but in the medium term contributed significantly to the prosperity of the city. By accepting these exiles, East Friesland, but especially Emden, was strongly shaped politically, economically and religiously. In 1660, grateful descendants of the refugee families donated a relief with the “Schepken Christy” (“Schiffchen Christi”) and the inscription: “Godts kerck, vervolgt, verdreven” on the east portal of the Great Church, which was called “moederkerk” (“mother church”) , heft Godt hyr trost Gegeven "(" The Church of God, persecuted, driven out, God has given consolation here "). The portal survived the bombing raids in 1943 unscathed. Today the sailing ship with the inscription is the seal of the Evangelical Reformed Church . Due to the common Dutch language, the refugees were integrated in the large Reformed community and shaped it. In addition, a French Reformed community emerged, which retained its independence until the 19th century.

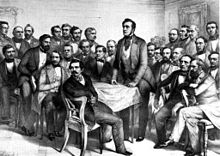

In order to give the widely dispersed Dutch refugee communities a church order , the Emden Synod was convened in 1571 . It was the first national synod of the Dutch Reformed, who developed a three-stage synodal structure based on the principle of subsidiarity . The synod was held from October 4th to 13th, 1571, without public attention and without the participation of the city. The venue was the former armory at Falderntor, which later became the old town hall, which was completely destroyed in the Second World War . The Emden Synod was an important step in the constitution of the Dutch Reformed Church , here the Low German Reformed Church , the forerunner of the Protestant Church in the Netherlands . The preacher Menso Alting promoted the implementation of Calvinism in Emden from 1575 . In the spring of 1578, the Emden Religious Discussion was an important disputation between the Reformed and Mennonites.

The blockade of the Dutch ports by the Spaniards also allowed shipowners and merchants to move to the next safe place. As a neutral port, Emden was able to attract large parts of its trade and, thanks to its technical knowledge, its capital and its trading connections, it temporarily became the largest port in Europe. The city now had trade connections from Westphalia via England to Scandinavia . In 1564 the Merchant Adventurer also temporarily relocated their pile of cloths from Antwerp to Emden, and later to Hamburg.

The population of the city swelled by the large number of refugees, but also by the economic boom that was triggered by them. In 1550 Emden still had about 5000 inhabitants, 20 years later the number had quadrupled.

In order to force the Ems back into its old bed, the city had an approximately 4.5 km long sheet pile wall made of oak logs, the so-called Nesserlander Höft , built from 1581 . This building was completed in 1616.

The city became very wealthy during this time, which is reflected in the town hall , which was built in 1574–1576 according to plans by Antwerp city architect Laurens van Steenwinckel . The construction of the town hall burdened the city with 56,000 guilders.

After several tax increases, in the course of the Emden revolution, the citizens of Emden removed the city council appointed by Count Edzard II in 1595 and took the count's castle. With the Treaty of Delfzijl of July 15, 1595, the count had to undertake to renounce most of his rights in Emden.

The Netherlands supported this company by sending a protection force to Emden, which only withdrew in 1744 after the death of the last Cirksena and the subsequent transition from East Frisia to Prussia. As the “satellite” of the Netherlands, Emden de facto achieved the position of a free imperial city and, with the reformed south-west, joined the Calvinist Church of the Netherlands more and more closely. As a result, Dutch became the standard language of the upper middle class in Emden in the course of the 17th century.

In 1604 Johannes Althusius became the syndic of the city of Emden.

From the Osterhusi Accord to the Peace of Westphalia (1611 to 1648)

Internal political differences between Count Enno III. and the city of Emden, despite repeated attempts at unification, such as the settlement of Delfzijl of 1595, the Emden Concordate of 1599 and the Hague settlement of 1603, since 1609 the Emden estate garrison has been involved in military actions against the count. This led to the occupation of Aurich and Greetsiel by the corporate troops. Under the pressure and mediation of the Dutch States General as guarantor power, a contract was concluded between the count and the estates at a general parliament in Osterhusen on May 24, 1611 , which regulated the mutual relationship in 91 articles. The estates enforced a far-reaching restriction of the count's powers, especially in the financial field, especially tax collection.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, the city had a population of 18,000 to 19,000, including between 5,000 and 6,000 Dutch refugees. From 1606 to 1616, the town builder Gerhart Evert Pilooth , later advised by the Dutch fortress builder Johan van Valckenburgh , brought the town up to date with the latest defense technology by building the Emder Wall . As a result, the city was protected from access by foreign commanders during the Thirty Years' War , while the rest of the county suffered great hardship . Troops of the Protestant military leader Ernst von Mansfeld advanced on the city in 1622 and occupied several villages in the area. However, Mansfeld and his soldiers never set foot in the city itself. Rather, the city officials of Emden let the mercenary leader camped near the city know that they were “confident that we will separate pestilence, hunger and sorrow from one another”. The city itself was in no way affected by the outbreak of the plague in East Frisia, but there were many deaths in the surrounding area.

In the following years, Emden suffered more from the stresses of the war. More and more refugees from the county huddled within its walls. The maintenance of the city fortifications and the Nesserlander Höft also cost huge sums of money, which is why the maintenance work on the sheet pile wall in Dollart had to be abandoned in 1631. The farm was subsequently destroyed again by the floods of the Ems.

In 1621, The Hague issued a peat export ban because the poorly forested country needed the fuel itself. Until then, Emden had covered a large part of its peat needs from Oldambt (Groningen province), and to a lesser extent from Saterland . In the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War, the Saterland peat deliveries also stalled. The four Emden merchants Simon Thebes, Claas Behrends, Cornelius de Rekener and Gerd Lammers therefore sought permission from Count Ulrich II of East Friesland to set up a fen colony to mine the peat. After the count's approval, Großefehn was founded in 1633 , the first feudal settlement in East Frisia. From Großefehn, peat was transported to Emden in small ships.

In the years 1629 to 1631, the city acquired other surrounding splendors on the right bank of the lower Ems. From the property of the Frese family in Uttum and Hinte came the greats Groß- and Klein- Borssum , later also Jarßum and Widdelswehr , for which Emden together paid a little more than 21,000 East Frisian guilders. In 1631, Emden finally acquired the largest area of its glories, Oldersum , including the surrounding villages of Gandersum , Rorichum , Tergast and Simonswolde . The city paid around 60,000 Reichstaler for this. With the exception of the glory of Petkum , Emden ruled the entire lower right bank of the Ems. The acquisitions, made for geographical and strategic considerations, were to serve a further purpose in the future, according to the will of the Emden city tour: With the splendor, Emden hoped to gain a seat and vote in the knighthood curia of the East Frisian landscape from around 1636. However, this request was successfully rejected by the other estates.

The fact that the city was not captured during the war can also be seen in the urban development. Next to the port gate, the only city gate of Emden still preserved today, the New Church was built between 1643 and 1648 according to plans by the Emden council builder Martin Faber . It was the first post-Reformation church building in the city.

Assertion against regional rule, stagnation in economic life (1648 to 1744)

The decades after the Thirty Years' War were marked by ongoing disputes between the East Frisian Count House and the Estates . In addition to the question of maintenance and the power of disposal over the class garrison, there were also tax issues, especially those about the amount and use of the money collected.

“Symptomatic of this is the dispute over the admission to the imperial prince's rank, requested by Count Enno Ludwig in 1654 […]. When asked critically by Emden because of the associated increased representation costs, he still strictly denied in April 1654 that he had taken such an initiative, whereupon the city smugly agreed to send him a copy of an application that had apparently been submitted to the Reichstag without his consent and, by the way, reminded of the saying: Better a rich count than a poor prince . Enno Ludwig and his councilors must have pounded their ears while reading this cheek. "

Enno Ludwig was raised to the personal prince status by the emperor in 1654 after he had died childless, finally his brother Georg Christian to the hereditary. He was thus able to marry the daughter of the Duke of Württemberg, Christine Charlotte , who after Georg Christian's death in 1665 ruled East Friesland as guardian for her son for 25 years. The princess represented an absolutist claim to power over the estates, which the estates eventually rallied behind the city of Emden as the most powerful opponent of sovereignty.

The Netherlands, which were the protector of Emden's interests in relation to the East Frisian Princely House during the city's golden age, had been involved in several wars, especially with England, since the middle of the 17th century, and mostly stayed out of inner-East Frisian disputes. They also approached the East Frisian Count House, which aroused suspicion in the city of Emden and among the estates. In fact, in the 1660s, Münster troops of Prince-Bishop Christoph Bernhard von Galen marched into East Frisia twice , both times with the consent of the East Frisian Princely House. Another invasion of Münster's troops in 1676 finally led to conditions similar to civil war, as Princess Christine Charlotte had the troops sworn in after the bishop had dismissed them. Among other things, the troops conquered the Emden glories, including Oldersum with its castle , in order to collect taxes from the lands that the princess had hoped to get from the city in vain. The Emder responded with the formation of citizens' companies, the state estates took the side of the city. In the following two years there were skirmishes with varying successes on both sides, but with greater successes of the estate troops, until in 1678 the (former) Münster troops withdrew again under pressure from the emperor.

“The duped was Christine Charlotte, who, despite all her efforts, finally found herself without military means of power and still had not come a step closer to her goal of becoming more independent from the estates than her predecessors. For the estates, however, the events of these two years were a bitter lesson. The experience of being largely helplessly exposed to the pressures of national rule when the latter had only a few military in their hands must have been a shock for them, reinforced by the increasingly clear realization that the States General, who in 1672 themselves were with France had stood with their backs to the wall, were only very partially ready or able to stand by them […] […]. It was therefore clear that Emden and the estates needed new protectors if they wanted to maintain their position vis-à-vis national rule in the long term. "

The city found this in Brandenburg-Prussia , which for its part was interested in following the example of the Netherlands and becoming a dominant trading and economic power. For this, the Brandenburgers needed a port on the North Sea. On April 22, 1683 they were able to negotiate a trade and shipping agreement with Emden, a secret agreement was signed between Emden and the estates on the one hand and Brandenburg on the other hand on September 22, 1682. Landed on the night of November 14th to 15th of the same year Brandenburg troops in Greetsiel and established themselves at the castle there. Brandenburg soldiers were also ordered to Emden. Protests by the princess went unheard. The Great Elector then moved his Brandenburg-African Company from Pillau to Emden, which was supposed to share in the company's profits. However, the company failed to achieve economic success, so it was dissolved in 1711. In 1684 the Admiralty of the Kurbrandenburg Navy was established.

The Christmas flood of 1717 caused only minor damage in Emden. In the entire Emden office, 53 fatalities were recorded, 34 completely and 59 partially destroyed houses. More than 900 animals (horses, cows, pigs and sheep) drowned in the floods. Compared to the offices in the north of East Frisia, however, this was little: 282 people died in the north office and 585 in the Berum office. However, the Krummhörn and today's west of the urban area with the villages of Larrelt, Wybelsum, Logumer Vorwerk and Twixlum were badly affected by the flood.

In contrast to the neighboring Oldenburger Land, it took several years to repair the dykes, which is mainly due to a lack of money, but also to a dispute about who should bear the burden. In the more than five years that followed, new storm surges wiped out the partly makeshift repairs to the dikes and flooded the country. Every flood brought salt water with it, which left the soil barren until rain washed away the salt.

In the conflict between the prince and the estates over tax sovereignty, not least to repair the flood damage, the city instigated the so-called appeal war in 1724 , in which it was ultimately defeated. As a result, it was politically isolated and weakened economically. The Emder glories was sequestered . In this situation, the city relied on Brandenburg help to regain its economic position and existing privileges. In return, the East Frisian estates should recognize the Prussian eligibility in East Frisia. On March 14th, 1744, with the conclusion of the Emden Convention, primarily economic regulations were agreed. Furthermore, Prussia relied on the right issued by Emperor Leopold I in 1694 to enfeoff the Principality of East Friesland in the event of a lack of male heirs. Despite the resistance of the Kingdom of Hanover , Prussia was to assert itself in the endeavor for East Frisia.

Prussia, the Netherlands and France (1744 to 1815)

After the death of the last Prince of East Frisia, Carl Edzard from the House of Cirksena (reign 1734–1744), East Frisia fell to Prussia in the course of an expedition . Just a few days after the Count's death, 80 Prussian grenadiers marched from Emden to Aurich and occupied the Count's castle. The arrival of the Prussian administration quickly meant the end of existence as a “state within a state” for Emden.

In 1751, the Prussian King Frederick the Great founded the Emden East Asian Trading Company , whose ships brought overseas goods (especially tea and porcelain ) from the Chinese canton to Emden. For this purpose, the port of Emden was declared a free port , making it one of the oldest in Europe. The outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756, however, brought about the decline of the trading company after a short time, so that it was dissolved in 1765.

In the years 1798 to 1800 the Treckschuitenfahrtskanal, later called Treckfahrtstief , was created between Emden and Aurich , which led through what is now the municipality of Ihlow . With barges , the horses towed were promoted the trek airline mail, cargo and passengers, where the channel has received its name. The horses were changed at the Mittelhaus near Riepe. The hydraulic engineer Tönjes Bley from Horsten was in charge of the planning of the canal . The company was unable to establish itself in the long term, as the plan to run the canal through the entire East Frisian peninsula failed, not least due to insufficient funding. It was only in the years 1880 to 1888 that the plan from the beginning of that century was implemented to continue the canal. It was extended to Wilhelmshaven and henceforth called the Ems-Jade Canal . This came too late for the Treckfahrtsgesellschaft: the construction of roads and railway lines in East Friesland meant the end of regular shipping to Aurich in the 1860s.

As early as 1806, Emden was occupied by Dutch troops. In the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, East Frisia was formally ceded to the Kingdom of Holland . The new sovereigns ended the monopoly of Emden in the Ems shipping, which continued to have an effect for decades: The "Postofrancorecht" (ie the free port) fell, as did the Emden shipping duty on the Ems and the stacking right. The city lost considerable income as a result. In the Reichenbach Convention in 1813 it was determined that East Frisia should fall to the Kingdom of Hanover after the war against Napoleon ended . The Congress of Vienna confirmed this. Great Britain , which is in personal union with Hanover, played a leading role . The British initially prevented Prussia from being re-established in Emden and thus on the North Sea coast.

The Hanoverian period (1815 to 1866)

The February flood of 1825 , which raged on February 3rd and 4th of this year, showed once again how endangered Emden was from storm surges. It only cost one human life, which was very little compared to previous storm surges. Except for a few higher streets on the old terp, the whole city was under water. The material damage was considerable. The February flood was the last severe storm surge to affect the core city of Emden.

In the first half of the 19th century, port handling not only suffered from the increasing silt problem. With the loss of Emden's trading privileges, the city also faced increasing competition from Leer and Papenburg. In 1840, Leer once exceeded the Emden port turnover, which did not happen again before or after. However, the entire East Frisian sea trade was at a low level during this time. The agricultural crisis in several years, with the ensuing collapse in exports of agricultural products, had an impact on one of the port's main handling branches.

The revolution of 1848/49 was also deeply echoed in Emden. Left-wing and right-wing liberals as well as conservatives discussed the “whether” and “how” of German unification in newly founded newspapers. The right-wing liberal Emden shipowner and businessman Ysaac Brons was sent to the Paulskirchenparliament in Frankfurt . There he belonged to the casino faction .

At the local level, liberals demanded the dissolution of the city council and the magistrate and the redefinition according to universal and equal suffrage, but could not prevail. On March 5, 1849, a general workers' association was founded in Emden. For February 1850, the establishment of a “sick drawer”, a kind of health insurance, is reported. In the same year a workers choral society followed. In April of that year the membership of the General Workers' Association was 145, with a total population of around 12,000. The first Emden workers' association was not of resounding political power: It disbanded on May 21, 1851. With him the chest and the choir disappeared.

Emden's infrastructure has been expanded since the 1840s. With financial support from the kingdom, the Emder mainly tackled the problem of increasing silting up of the port. Between 1845 and 1849 the Emden fairway was dug, which re-connected the city's port with the Ems. It was closed by a new sewer that could also be used as a sluice. However, this did not solve the problem of drainage in the hinterland. Furthermore, a decision had to be made between the interests of the city, which mainly consisted of a strong silting of the water for the natural silting up of the port, and the most continuous drainage of the hinterland, which was the concern of the farmers. The decision was largely in favor of the port industry. In the course of the creation of the fairway, the city polder and the Königspolder were diked at the same time, which made the later southern expansion of the port possible.

The East Frisian landscape , at that time still the representative body with a political character, got involved financially in road construction from 1840 onwards. In 1842 a road from Emden to Aurich was laid out, which was made of clinker bricks . It was one of the first stone roads in East Frisia. A connection to the north was added two years later. Pewsum was connected to the road network via Hinte in 1859, the route is the forerunner of today's Landesstraße 3 . Nevertheless, the canals to the surrounding villages were the primary traffic routes for decades to come, at least for goods transport. In peat shipping alone, the city authorities recorded between almost 5,000 and almost 6,000 ship movements across the Emden canals in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Village boatmen took over the supply of the surrounding towns with goods from the city and delivered agricultural products in the opposite direction: “From the Sielhafenort, smaller ships, so-called Loog ships, transported the cargo to the inland and supplied the marshland villages (loog = village). The loog ships from the Krummhörn enlivened the canals of the city of Emden until the 20th century. "

During this time the construction of the Hanover West Railway from Emden to Rheine and continuation to Münster took place. The Emden train station was completed on June 20, 1856. East Friesland was connected to the national rail network through the Westbahn - 21 years after the first railroad in Germany. The Westbahn was seen as a "great step for Emden's economic growth". The rail connection brought Westphalia closer to East Frisia. Agricultural products from the region could now be transported more quickly to the south, Westphalia with its growing industry was an important sales area.

A gas works was inaugurated in 1861. The first gas-lit lanterns in Emden started burning on October 10th of that year: "After the railroad and the steamships, this facility was a further harbinger of the emerging industrial age."

Rise to the industrial city (1866 to 1914)

The “return” to Prussia was generally welcomed in Emden and East Frisia. The annexation of the Kingdom of Hanover by Prussia, so many people from Emden hoped, would also bring better times economically. For East Friesland, the “first” Prussian rule from 1744 to 1806 brought a resurgence of peatland cultivation and successful new dykes, for Emden in particular an - albeit modest - revival of trade after decades of stagnation.

The hopes did not go unfulfilled. In the years between the German Wars of Unification and the First World War , Emden recorded a significant upswing in industrial development. A paper mill was opened as early as 1867 (it remained the city's largest employer with around 160 to 180 employees until 1900), followed by the Cassens shipyard in 1875 . In addition, by closing the gap in the railway line (Bremen-) Oldenburg-Leer (1869), a continuous railway connection to the (south) east was created.

The rise to an important port and industrial city is inextricably linked with the name of Leo Fürbringer (1843–1923). He served as Lord Mayor from 1878 to 1913; this period still bears his name today: the “era of Fürbringer”. In those decades the port of Emden was expanded to become the seaport of the Ruhr area, followed by industrial development.

In cooperation with the Emden representative in the Prussian state parliament, Carl Schweckendieck , Fürbringer campaigned for the expansion of the port facilities. Emden benefited from the self-sufficiency efforts of the German Reich : They wanted a separate connection between the Ruhr area and the sea in order to be independent of the Dutch mouth of the Rhine. The port of Emden offered good conditions because it was the westernmost seaport in Germany and the distance from the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area to Emden was shorter than to all other German seaports - with the exception of Papenburg and Leer, which, however, had a significantly shallower Ems fairway.

Apart from the railway line between Emden, Münster and the Ruhr area, which was completed in the 1850s, there were few transport options. In particular, there was no connection for barges. Therefore, between 1880 and 1900 there was a significant expansion of the inland connections of the Emden port. First and foremost, the construction of the Dortmund-Ems Canal (1892–1899) should be mentioned, supplemented by the Ems Lateral Canal from Oldersum to Emden. The Ems-Jade Canal was added between 1880 and 1888 . This connected Emden with Wilhelmshaven and was also intended to drain large parts of the Auricherland . In the course of this construction, the boiler lock , unique in Europe, was built (1886/1887). The seaward accessibility of the Emden harbor was significantly improved in 1888 when the Nesserland lock was inaugurated after a two-year construction period .

The East Frisian Coast Railway opened on June 15, 1883. During the Prussian district reform in 1885, Emden became an independent city .

The Nordseewerke was founded in 1903 , but after just a few years the business ran into financial difficulties - the city of Emden had to intervene to maintain the shipyard and jobs. With the entry of the Ruhr industrialist Hugo Stinnes (1911), the final breakthrough to a modern shipyard was achieved. The large shipyard was Emden's largest industrial company until the early 1970s. In 1913, the Great Sea Lock was inaugurated as another major infrastructure measure . With an internal length of 260 meters, it was considered one of the largest sea locks in the world at that time. With the construction, a new harbor basin was created, the new inland port . Here mainly ores and coal were handled, for or from the Ruhr area.

The port and the new industrial companies could not meet their labor needs from the Emden population alone. In addition to East Frisians who moved to the seaport city from the surrounding area (if they did not commute), workers from other parts of Germany also came to Emden. Since there was not enough living space, a new district was built for the dock workers from 1901, which later in that decade was given the double name Port Arthur / Transvaal . With the increase in industrial operations and port handling, Emden, together with Leer, gradually became the focal point of social democracy in East Friesland. The Social Democrats appeared in public for the first time on October 6, 1889, during the Reichstag election campaign. The largest strike before the First World War occurred in 1905 when around 200 dock workers went on strike between November 18 and December 30. Strikes also broke out in other industries at that time.

The First World War meant a collapse in cargo handling for the port of Emden. Whereas in 1913 this was 1.55 million tons for imports and 1.68 million tons for export, during the war it did not exceed a six-figure sum for imports and exports (exception: in 1918 the export was 1.07 million tons). The port reached its lowest point in 1919, when imports amounted to 414,000 tons and exports to 488,000 tons - values that were only undercut in the 20th century at the end of the Second World War.

The Imperial Navy used Emden as a naval port. In addition to minesweepers, the Nordseewerke also built fish steamers that could also be used to search for mines. The shipyard also repaired numerous naval vehicles. Under the command of Lieutenant Walther Schwieger , the submarine U 20 left the Emden base on April 30, 1915, and sank the Lusitania passenger ship a few days later off the coast of Ireland . The sinking cost the lives of 1,198 people and drove the United States to the Entente side more than before .

The supply situation in the city had to be regulated by a large number of offices. Food was rationed, and the city leaders set up a "usury" to prevent excessive prices. 531 Emden soldiers died in the war.

Weimar Republic (1919 to 1933)

On November 8th, a workers 'and soldiers' council was formed , which took over the military and civil authority in the seaport city. After the invasion of government troops on February 27, 1919, it was triggered on March 1 of that year. In the winter months of 1918/19 there were so-called "bacon parades" from Emden to the farmers in the surrounding villages, where food was stolen.

New social achievements came with the beginning of the Weimar Republic. Outwardly visible sign of a new social policy was the social housing that was promoted in Emden in the 1920s. New districts were created, others were expanded with new apartment blocks. The Friesland colony , which was built by the shipyard for the employees of the North Sea Works , is an example of a workers' settlement that also took into account agricultural self-sufficiency (or food supplement) . The Conrebbersweg district was also created during the Weimar Republic. The settlement houses there comprised plots of a size that also allowed agricultural sideline income. The Emdens civil servants' building and housing association also had new apartment blocks and rows of houses built primarily in the administrative district , as well as the longest block of houses in Emden, which is still in existence today on Petkumer Straße. In addition to the remaining Beamtenbau Club 1924 also from the labor movement, founded out (and also still in existence) was Wohnungsbaugenossenschaft "self-help" was founded. The Herrentorviertel and the western part of the Barenburg district also grew strongly during the years of the Weimar Republic due to the large number of new residential buildings . The infrastructure such as schools and kindergartens or public green areas did not get beyond the planning stage at that time. The Tholenswehr district was also newly laid out in the years of the Weimar Republic , but in contrast to the large housing expansions, it was laid out as a single-family housing estate for high earners.

In Emden, due to the socio-economic structure of the city, there was not only a strong social democratic movement during the Weimar Republic, the Communist Party was also very active and was able to achieve above-average results in elections in a comparison of the Reich (see table). There was "(...) considerable communist influence among the dockworkers, the workforce of the fish processing plants and shipyards, the sailors of the herring fishing fleet (...)."

In 1921 and 1922 there was a global economic slump . On July 3, 1922, the mark was still a hundredth of the value of August 1914, on October 3, 1922 only a thousandth, until finally in November 1923 the rate for one US dollar was 4.2 trillion marks. When the Rentenmark was introduced, the prosperity of the peasants and their financial reserves had melted away except for meager remnants. To make matters worse for Emden was that the occupation of the Ruhr area by France cut off the city from its lifeline and paralyzed local industry, namely shipbuilding . All of this led to the strengthening of the radical political wing. In the city of Emden, which is characterized by its shipping industry, the KPD profited from the layoffs at the shipyards.

On August 11, 1928, high school student Johann Menso Folkerts founded the local branch of the NSDAP . If it was initially ignored in elections, its share in the elections increased considerably by 1933. The National Socialists also grew at the local level. Among other things, they made use of the financial situation: The city was heavily in debt in the late years of the Weimar Republic (and beyond). Although many of the residents were by no means poor, the magistrate did not raise taxes to reduce debt. On the contrary, the tax rates remained well below the average for neighboring cities. The NSDAP therefore spoke of mismanagement in election campaigns.

time of the nationalsocialism

The last free municipal council elections of the 1930s took place on March 12, 1933. The NSDAP already benefited from freedom and press restrictions and won most of the seats, if not the absolute majority of the votes. She came, however, "from the state" (after the previous elections in 1929 she was not represented in the city council) to 13 seats. The black-white-red battle front won eight seats in the city council, the SPD seven, the KPD six and the DDP one. In July 1933, the MPs demanded the removal of Mayor Mützelburg. The National Socialists regarded him as unreliable because he had acted against them as a police senator. The young district leader, Johann Menso Folkerts, stood out in particular . In a meeting about personnel matters on October 16, 1933 in the town hall, Folkerts accused the mayor of sabotaging personnel policy. The Lord Mayor Mützelburg was forcibly dragged out of his office by a crowd of NSDAP supporters and SA men and forcibly led through the city. He then resigned from his post “for health reasons”. Hermann Maas became the new mayor in November, but a split relationship with Folkerts and many quarrels ultimately cost him his job in Emden. Therefore, in 1937 the mayors of Emden, Delmenhorst and Wilhelmshaven exchanged rings. Maas went to Delmenhorst, the local mayor Wilhelm Müller to Wilhelmshaven and his mayor Carl Renken to Emden.

In March 1933, political opponents were taken into " protective custody " by the National Socialists . This primarily concerned communists. The mayor asked the regional president in Aurich whether he could have 13 communists transported to concentration camps. For the communist underground movement, the port of Emden was an important “transshipment point” from 1933 to 1937. In the first wave of persecution in the spring of 1933, communists, social democrats and trade unionists from all over the Reich arrived there who were unable to be seen there because of the heavy surveillance of the port of Bremen. With the help of Dutch communists, they were transported across the Wadden Sea to the neighboring country. The communist underground movement remained active for several years. This only ended in 1937 with the mass arrest of around 70 people involved.

The time of displacement and discrimination began for the Jewish population. This caused many of the local Jews to flee. Among the Jews who had fled in 1933 was Max Windmüller , who later joined the resistance of the Westerweel group in the Netherlands under his code name Cor and saved many Jewish children and young people. According to newspaper reports, 130 people emigrated from 1933 to 1938, 50 moved to other cities. According to another source, 430 Jews were still living in the city on September 1, 1938, which would mean that around a quarter of the Jewish population had left Emden between 1933 and autumn 1938 - before the Reichspogromnacht.

On the night of November 9-10, 1938, the Emden NSDAP and the SA took part in the riots against the Jews, ordered by the Reich leadership of the National Socialists and organized by the local party commanders . The synagogue was burned down and all male Jews were deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp , from which they could only return after weeks. The discrimination continued. At the end of January 1940, an initiative by East Frisian district administrators and the municipal authorities of the city of Emden led to the instruction of the Gestapo control center in Wilhelmshaven, according to which Jews were to leave East Frisia by April 1, 1940. 1941 belonged Emden to the first twelve towns in the kingdom, from which Jews in the East deported were. The last Jewish residents were deported in 1942.

On March 31, 1940, Emden was attacked and bombed by British aircraft for the first time. Probably the biggest catastrophe that ever took place in Emden was the bombing by Allied bomber units during the Second World War , when more than 80 percent of the city area was destroyed on September 6, 1944. Allied bomber units dropped about 1,500 explosive bombs, 10,000 incendiary bombs and 3,000 phosphor bombs in several waves.

At the end of the war, 1,121 soldiers in Emden lost their lives, and 316 residents of the city were killed in air raids and other war effects. The devastating bombing raid on September 6, 1944 completely destroyed 78 percent of the 10,000 houses at the start of the war or made them uninhabitable. In addition to the town hall, the (only) hospital, eight out of ten schools and several bridges were among the destroyed buildings. In addition, around 55 percent of the city's industrial and commercial enterprises were destroyed.

Reconstruction (1945 to 1964)

After the end of the war, most of the evacuees were unable to return to the bombed-out city. "At the district council conference on June 15, 1945, the Mayor of Emden asked not to put any pressure on those evacuated from Emden to return to Emden, as accommodation in Emden would run into great difficulties."

After the war ended, the Netherlands considered annexing large parts of Germany, including Emden. In addition to a few border strips, the Netherlands then made specific claims, especially on the Dollard, the mouth of the Ems and Borkum . Emden's port was to be "drained" by piling up and the diversion of the river bed in order to divert maritime trade to Delfzijl. However, the annexation failed due to the resistance of the Western Allies.

In addition to removing the rubble (much of which was used for road construction in rural East Frisian communities, but some inner-city canals were also filled with it) and managing the shortage, political life in the city also had to be reorganized. The choice of the Canadian city commander Newroth fell on Georg Frickenstein as the new mayor. Frickenstein was already active as a liberal politician in the Emden magistrate during the Weimar Republic. He gathered reliable politicians around him, but died early during the reconstruction: as early as September 1946. His successor was Egon Rosenberg, who was born in Emden until the first local election in October 1946, who was eventually replaced by Hans Susemihl after that election . The social democrat, who came from Mecklenburg and had lived in Emden since 1908, remained in office until 1952 when Rosenberg replaced him for a legislative period. From 1956 to 1964 Susemihl was again Lord Mayor. Under these city leaders, the reconstruction was pushed ahead, whereby the badly damaged city received a lot of help from outside. During his visit to Emden in 1948, Lower Saxony's Prime Minister Hinrich Wilhelm Kopf left the dedication in Low German in the city's Golden Book: “Wi staht dorvör, wi möt da dör” ( “We stand in front of it, we have to go through there” ).

The reconstruction of the city dragged on until the 1960s - at the beginning of that decade there were several barracks in the city because living space was still scarce. One of the most prominent residents of such a barrack camp today was the Emden-born director Wolfgang Petersen . Between the currency reform of 1948 and 1960, around 700 new apartments were built in Emden every year, a total of around 9,000. Around 6,000 of them were built with the help of around 40 million DM in federal and state aid. The basis for the reconstruction was an urban development plan, which provided for a careful rebuilding on the old urban plan, but with wider street spaces - a plan that is well received by architectural historians. In 1958 the Martin Luther Church was consecrated as a replacement for the Lutheran church that was bombed during the war on the same site. When it was consecrated, it was the largest new church in the Hanover State Church.

The reconstruction of the city was completed around the mid-1960s. The most symbolic was the opening of the town hall in 1962. The reopening took place on September 6th, exactly 18 years after the heaviest bombing. Since the end of the 1960s, Emden - as in many other large cities in Germany - has focused on massive development with high-rise buildings. The former union-owned Neue Heimat group played a prominent role in this. In the districts of Barenburg and Borssum in particular , several high-rise buildings were built by the mid-1970s. Among other things, the so-called glass palaces , the largest residential buildings in East Frisia, were built in Barenburg . At the time, city planners assumed that the population of Emden could grow to 75,000.

In addition to housing construction, massive investments in school construction were necessary. Between 1952 and 1975, more than one and a half dozen new buildings and extensions were built in the school system. Eight new gyms were also built. In addition, the new hospital was inaugurated in 1953 and has since been named after the former mayor Hans Susemihl.

Politically, the reconstruction was initially carried out under the leadership of the SPD, which, however, was replaced from 1952 to 1956 by a bourgeois bloc, which also provided the mayor. From 1956 to the end of the 1990s, the SPD ruled again and, in view of election results of more than 50 and sometimes more than 60 percent of the valid votes cast, did not need a coalition partner. In the local elections in 1972, the Social Democrats achieved a record two-thirds of the vote.

The era of the economic miracle also left its mark on Emden: Already at the beginning of the 1950s, ships were launched again at the Emden shipyards ( Nordseewerke , Cassens-Werft and Schulte & Bruns , the latter no longer exists) after the occupying powers lifted corresponding restrictions had. Emden shipping companies also resumed operations in the early 1950s. In 1959 the Frisia oil works were built, but they were closed again at the end of the 1970s. Only at the beginning of the 1990s was the production of naphtha restarted briefly before the refinery was dismantled. The port transshipment also benefited from the reconstruction: Ore transshipment played a dominant role for the smelters in the Ruhr area: In 1959, 84 percent of German ore imports by sea passed through the port of Emden.

Economic recovery, infrastructure and setbacks

In 1964, after internal party disputes , Hermann Schierig replaced Hans Susemihl as Lord Mayor. During Schierig's tenure (until 1973) extensive economic developments took place and, thanks to good tax revenues, the city's infrastructure was expanded. The planning for the largest industrial settlement in the history of the seaport city, however, had already begun before 1964: The Volkswagen group had found what it was looking for in the Larrelter Polder when looking for a production site near the sea and port and began building the Volkswagen plant in Emden in 1964 . Production started as early as December 1964, and by 1965 the car factory had 3,000 employees. The number of employees rose in the following years to more than 8,000 (1971).

The further expansion of the port also progressed: Overall, the state of Lower Saxony, as the owner of the Emden port, invested around 100 million D-Marks between 1948 and 1973, which went into the construction of new and enlargement and deepening of existing port basins as well as the construction of new quays and handling facilities. The ore handling, especially for the smelters in the Ruhr area, reached its peak in 1964 with 9.7 million tons, but remained in the following years always over five million tons. By contrast, the handling of coal stagnated, and the handling of grain was often subject to fluctuations. After the construction of the VW plant, however, the car handling was added: in 1971 almost half a million vehicles were handled, almost without exception for export to the USA.

In the 1970s, the city of Emden reached its current geographical extent. Larrelt , Uphusen and Harsweg were incorporated into the municipality as early as 1945/46 under pressure from the British occupying forces , but in the course of Lower Saxony's municipal reform in 1972, the urban area was again considerably expanded. With the expansion to include Wybelsum , Logumer Vorwerk , Twixlum , Widdelswehr and Petkum and the flushing of the Rysumer Nacken an der Knock (communal incorporation on January 1, 1976), the city reached its current size of 112 square kilometers. Since then, agricultural land has made up the largest proportion of the urban area, although agriculture only plays a very subordinate role in terms of value creation and the number of jobs in the city.

The city's cultural offerings were expanded to include the North Sea Hall (built in 1972) and the New Theater (also in 1972). The new Emden Hauptbahnhof was inaugurated in 1973. Emden has also been the location of a technical college since 1973 . A new part of the city was built around the technical college from 1977 (start of planning) .

At the Knock in the west of Emden, a landfall station for natural gas from Norwegian fields was built in the North Sea in the mid-1970s. In 1977 the first gas was landed. At that time, the first considerations for the construction of the Dollarthafen - a gigantic port expansion project, which was never implemented due to the resistance of the neighboring Netherlands, fell. Environmentalists also fought vehemently against the project.

Around the middle of the 1980s, the increased turn to tourism began. In 1984 the museum ship Amrumbank (a former lightship) and in 1988 the rescue cruiser Georg Breusing were moored in the Ratsdelft , the oldest part of the Emden harbor . On October 3, 1986, the then Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker opened the Kunsthalle Emden , which was built on the initiative of Emden publicist Henri Nannen . The Johannes a Lasco Library has been located in the Great Church in the heart of the city since 1995 . The East Frisian State Museum was renovated at the beginning of the 2000s and brought up to date with the latest museum pedagogical standards.

Emden has not been a garrison town since 1996 : The NBC Abwehr Battalion 110 withdrew, and the Karl von Müller barracks has been empty since then. Since that year Emden, once one of the first naval ports in Germany, no longer has any military facilities.

In the first decade of the 21st century, Emden - like other port cities - turned its urban planning back to the water and the city center, while in earlier decades the population's urge for greenery and space was given in. On former port areas that are no longer used for transshipment, new, central (and in some cases exclusive) residential areas as well as hotel and office buildings have been created - a development that is not yet complete.

Archives, libraries and museums

Emden has a city archive that is considered one of the most comprehensive municipal archives in Lower Saxony. The documents, writings and files kept there go back to the end of the 15th century. Among other things, there is the certificate for the award of the city coat of arms in 1495. The Aurich location of the Lower Saxony State Archives , which is responsible for the East Frisian area, also houses archive material on East Frisian history, which also contains a large number of documents etc. from the Emden and East Frisian regions History houses. The North-West Lower Saxony Economic Archive collects historically valuable documents from the region's economic life. The Johannes a Lasco Library is a specialist library on the history of Calvinism in Europe. The East Frisian State Museum is a museum about the history of the city of Emden and the East Frisia region and shows how they are embedded in European history. Specialized catalogs are published for individual special exhibitions.

literature

The standard work on the history of the city of Emden is a three-part compendium as part of the twelve-volume treatise Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches , which was first published in 1974 by Deichacht Krummhörn and published by Leeraner Verlag Rautenberg. The possibly misleading chronology of the publication results from the fact that the period from early history to 1750 was subsequently divided into two volumes in order to do justice to the importance of the city in the 17th century.

- Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen , Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters : History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dike, vol. 10).

- Bernd Kappelhoff: History of the city of Emden from 1611 to 1749. Emden as a quasi-autonomous city republic. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 11).

- Ernst Siebert, Walter Deeters, Bernard Schröer: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to the present. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1980, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 7).

Further works on the history of the city of Emden include:

- Reinhard Claudi (Ed.): Stadtgeschichten - Ein Emder Reading Book 1495/1595/1995 . Gerhard Verlag, Emden 1995, ISBN 3-9804156-1-9 . A work published on the 500th anniversary of the award of the city's coat of arms with contributions by several authors, some of which highlight chronological, some thematically important aspects and times of the city's history.

- Dietrich Janßen: September 6, 1944. Emden goes under. Wartberg Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2004, ISBN 3-8313-1411-X . Using interviews with contemporary witnesses and documents from the Allies and the Wehrmacht, the bombing war, the day Emden was destroyed in World War II and the capture by Allied troops are described.

- Axel von Schack, Albert Gronewold: Working alone, you won't get tired of it. On the social history of the city of Emden 1848-1914. Verlag Edition Temmen, Bremen 1994, ISBN 3-86108-233-0 . The authors have shed light on the industrialization of the city and the beginnings of the Emden workers' movement.

The following works deal with individual aspects of the history of the city of Emden:

- Marianne Claudi, Reinhard Claudi: Those we have lost - life stories of Emden Jews . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988, ISBN 3-925365-31-1 . One of the standard works on the former Jewish community in the city of Emden.

- Gunther Hummerich, Wolfgang Lüdde: Reconstruction - The 50s in Emden . Soltau-Kurier, Norden 1995, ISBN 3-928327-18-6 . Based on a (fictional) family history, but with historically proven facts, the reconstruction of the heavily destroyed city after the Second World War is described - including many details on the economic life of that time.

- Eberhard Kliem: The city of Emden and the navy . ES Mittler Verlag, Hamburg, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8132-0892-4 . Until the end of the 20th century, Emden was one of the most traditional German naval bases. Its importance from the beginnings in the 16th century to the closure of the naval base is described in detail.

- Klaas-Dieter Voss, Wolfgang Jahn (ed.): Menso Alting and his time. Religious dispute - freedom - civic pride. Isensee, Oldenburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-89995-918-5 (publications of the Ostfriesisches Landesmuseum Emden, issue 35). Accompanying volume for the exhibition of the same name in the Ostfriesisches Landesmuseum Emden and the Johannes a Lasco Library Emden from October 7, 2012 to March 31, 2013.

Web links

- The city archive of the city of Emden can be reached on this website .

- The Archaeological Service of the East Frisian Landscape is represented on the Internet and regularly reports news from archaeological research on the history of East Frisia at its address. There are also several entries about research projects from Emden. ( Archaeological Service of the East Frisian Landscape )

- The East Frisian Landscape has also published part of its Biographical Lexicon for East Frisia on the Internet.

Individual evidence

- ^ Wolfgang Schwarz: Die Urgeschichte in Ostfriesland , Leer 1995, ISBN 3-7963-0323-4 , p. 34.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: The prehistory in East Friesland . Leer 1995, ISBN 3-7963-0323-4 , p. 35.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 3.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 4.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 61.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN, (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 13.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 63.

- ^ Henning P. Juergens: Johannes a Lasco in Ostfriesland. The career of a European reformer. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147754-5 , p. 169.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 77.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 71.

- ^ Heinrich Schmidt: Political history of East Frisia . Rautenberg, Leer 1975 (Ostfriesland in the protection of the dike, vol. 5), p. 78.

- ^ Ingeborg Nöldeke: Hagioscopes of medieval village churches on the East Frisian peninsula. An unexpected discovery . In: Die Klapper (Journal of the Society for Leprosy Association), issue 18. 2010. P. 11.

- ↑ a b c Information according to: Gesellschaft für Leprakunde e. V .: Medieval leprosories in Lower Saxony and Bremen ( Memento of the original from July 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ a b c The Emden Lazarus House . In: Emder yearbook for historical regional studies of East Frisia . Volume 14 (1902). Pp. 479-481

- ^ North Frisian Association for Local Lore and Home Love: Friesisches Jahrbuch Emden 1956. P. 80

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 110.

- ↑ a b Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN, (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 140.

- ↑ City of Emden: "Engelke up de Muer" - the coat of arms of the city of Emden ( memento of the original from November 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed January 12, 2010.

- ↑ Klaus Brandt, Hajo van Lengen, Heinrich Schmidt, Walter Deeters: History of the city of Emden from the beginnings to 1611 . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 10), p. 166.

- ^ Henning P. Juergens: Johannes a Lasco in Ostfriesland. The career of a European reformer . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147754-5 , pp. 167ff. ( partly online ).

- ↑ Gerhard Müller: Theologische Realenzyklopädie . Volume 1. De Gruyter, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-11-016295-4 , p. 538.

- ↑ Elwin Lomberg: Causes, prehistory and effects of the Emden Synod of 1571 . In: Evangelical Reformed Church in Northwest Germany (Ed.): 1571 Emder Synod 1971. Contributions to history and the 400th anniversary . Neukirchener, Neukirchen 1973, pp. 14-15. Image under Moederkerk (seen January 13, 2010).

- ↑ Menno Smid: East Frisian Church History . Self-published, Pewsum 1974 (Ostfriesland im Schutz des Deiches, Vol. 6), pp. 194, 199.

- ^ Illustrations before the destruction in: Evangelical Reformed Church in Northwest Germany (Ed.): 1571 Emder Synod 1971. Contributions to the history and the 400th anniversary . Neukirchener, Neukirchen 1973, pp. 198-199.

- ↑ Helmut Glück : German as a Foreign Language in Europe. From the Middle Ages to the Baroque period . De Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-11-017503-7 , p. 313.

- ↑ Bernd Kappelhoff: History of the city of Emden from 1611 to 1749. Emden as a quasi-autonomous city republic. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 11). P. 28.

- ↑ Wolfgang Brünink: The Count of Mansfeld in East Friesland (1622-1624) , published by East Frisian landscape, Aurich 1957 without ISBN, page 136, note the 174th.

- ↑ Bernd Kappelhoff: History of the city of Emden from 1611 to 1749. Emden as a quasi-autonomous city republic. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 11). P. 37.

- ↑ Bernd Kappelhoff: History of the city of Emden from 1611 to 1749. Emden as a quasi-autonomous city republic. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 11). P. 280.

- ↑ Bernd Kappelhoff: History of the city of Emden from 1611 to 1749. Emden as a quasi-autonomous city republic. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1994, without ISBN (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, vol. 11). P. 290.

- ↑ Ernst Siebert: Development of the dyke system from the Middle Ages to the present. In: Hans Homeier; Ernst Siebert; Johann Kramer: Deichwesen (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, Volume 2), p. 334 ff.

- ^ Ernst Siebert, Walter Deeters, Bernard Schröer: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to the present . Rautenberg, Leer 1980 (East Frisia in the protection of the dike, vol. 7), p. 2.

- ↑ "Trecken" is East Frisian Low German and means "to pull".

- ^ Ernst Siebert: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to 1890. In: Ernst Siebert, Walter Deeters, Bernhard Schröer: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to the present . Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1980 (Ostfriesland in the protection of the dike, vol. 7), p. 52f.

- ^ Eckart Krömer: Small economic history of East Friesland and Papenburg. Verlag SKN, Norden 1991, ISBN 3-922365-93-0 , p. 76.

- ↑ Axel von Schack, Albert Gronewold: Work alone, you won't get full. On the social history of the city of Emden 1848–1914. Verlag Edition Temmen, Bremen 1994, ISBN 3-86108-233-0 , p. 30.

- ↑ Axel von Schack, Albert Gronewold: Work alone, you won't get full. On the social history of the city of Emden 1848–1914. Verlag Edition Temmen, Bremen 1994, ISBN 3-86108-233-0 , p. 38.

- ^ Ernst Siebert: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to 1890. In: Ernst Siebert, Walter Deeters, Bernhard Schröer: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to the present. Verlag Rautenberg, Leer 1980 (Ostfriesland in the protection of the dyke, vol. 7), p. 61.

- ↑ Gunther Hummerich: The peat shipping of the Fehntjer in Emden and the Krummhörn in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Emder Yearbook for Historical Regional Studies Ostfriesland, Volume 88/89 (2008/2009), pp. 142–173, here: p 145.

- ^ Harm Wiemann / Johannes Engelmann: Old streets and paths in Ostfriesland (Ostfriesland in the protection of the dike; 8), self-published, Pewsum 1974, p. 169.

- ↑ This is the judgment of the local historian and book author Ernst Siebert in: Ernst Siebert, Walter Deeters, Bernard Schröer: History of the city of Emden from 1750 to the present . Rautenberg, Leer 1980 (East Frisia in the protection of the dyke, Volume 7), p. 54.

- ↑ Gunther Hummerich: On the trail of an Emder street . Cosmas- und Damian-Verlag, Emden 2000, ISBN 3-933379-02-4 (Emder city views, Volume 2), p. 24.

- ^ Heinrich Schmidt: East Frisia in the protection of the dike: Political history of East Frisia . Self-published, Leer 1975, without ISBN, p. 430.