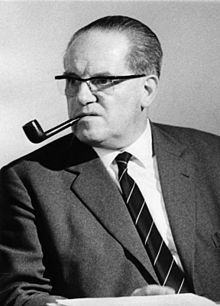

Herbert Wehner

Herbert Richard Wehner (born July 11, 1906 in Dresden , † January 19, 1990 in Bonn ) was a German politician ( KPD 1927–1942, SPD from 1946). From 1966 to 1969 he was Federal Minister for All-German Issues , then until 1983 Chairman of the SPD parliamentary group .

After initial membership in the social democratic youth organization SAJ, he first switched to the young anarcho-syndicalists of the SAJD in 1923 , which he left in 1926 to become a member of an anarchist organization. After he had left this again, he joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in 1927 , became a member of the state parliament in Saxony in 1930 and rose to become a member of the KPD's central committee in exile . After the National Socialists came to power in Germany, he was in exile at the Hotel Lux in Moscow from 1937 to 1941 . Wehner escaped the Stalinist purges , but there are indications that he denounced other German communists - possibly to save his own life. In 1941 he was sent to Sweden to lead the communist resistance against the Nazi regime in Germany; this provided an opportunity to escape the realm of danger and betrayal. In 1942 Wehner was arrested and experienced the end of the war in a Swedish prison. During this time he was expelled from the KPD on charges of having evaded the party mandate.

Coming to Hamburg in 1946 , Wehner became one of the leading members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . Because of his past, he officially stayed mostly in the second row, for example as deputy party and parliamentary group leader . Even if he came to the reformers late, as a party organizer he significantly supported the party's change from a clientele to a people 's party and the commitment to integration with the West , the market economy and the Bundeswehr ( Godesberg program ). After the SPD lost power in the federal government in 1982, Wehner no longer ran for the Bundestag in the following parliamentary elections in 1983 , which meant that he also gave up his position as parliamentary group leader.

Life

Herbert Wehner was born as the son of the shoemaker Robert Richard Wehner (1881–1937) and his wife, the tailor Alma Antonie Wehner, born. Diener (1881–1945), born in the house at Spenerstraße 13 in the Dresden district of Striesen . His father was a soldier in World War I and then joined a loose association of social democratic , socialist and communist soldiers.

Wehner was married three times: in 1927 he married the actress Lotte Loebinger (1905–1999). In his second marriage from 1944 he was married to Charlotte Burmester, nee Clausen, the widow of the communist resistance fighter Carl Burmester . After her death in 1979, he married her daughter - his stepdaughter - Greta Burmester in 1983 , so that she too could be looked after . She had served her stepfather as a secretary and supervisor for decades and gave up her job in return. After Wehner's death and the reunification of Germany , Greta Wehner moved to Dresden and founded the Herbert and Greta Wehner Foundation in May 2003.

Wehner died on January 19, 1990, after suffering for many years from multi-infarct dementia caused by his diabetes . It was a diabetic circulatory disorder of the brain stem. In honor of his lifetime achievement, an act of mourning took place in Bonn on January 25, 1990 . His remains found their final resting place next to those of his second wife Charlotte Burmester in the castle cemetery in Bonn-Bad Godesberg.

Early political activity

While still at school, Wehner had become a member of the Socialist Workers' Youth (SAJ), local group Striesen-West. In 1923 he resigned to become a member of the anarcho-syndicalist youth group Syndicalist-Anarchist Youth of Germany (SAJD). As a reason for his decision to turn his back on social democracy for the time being, he later stated that the SPD had supported the invasion of the Reichswehr into his home country of Saxony and thus betrayed the united front . The Reich government under Gustav Stresemann had sent troops to Saxony that year to end the coalition of the SPD and KPD in the Saxon state government. Within the SAJD he was sent to the 5th Reich Conference as a delegate in 1925. He quickly came into conflict with the SAJD as a whole, among other things he campaigned for the armed, revolutionary struggle (which the SAJD rejected in the majority) and turned against a trade union course, which he considered too reformist. Under Wehner's influence, the entire Dresden-Ost group left the SAJD in February 1926, re-formed as an “Anarchist Tatgemeinschaft” and joined the Red Aid as a whole . This anarchist group, which saw itself as Bakuninist , published the newspaper "Revolutionäre Tat" in 1926, the majority of which were written by Wehner.

After graduating from secondary school in 1924, Wehner began a commercial apprenticeship in Dresden. Because of his radical political activities, he lost his job in 1926.

In August 1925 he met Erich Mühsam at an anti-militarist rally in Dresden. Joint work, including on solidarity campaigns for the councilor communist Max Hölz, intensified their relationship. In mid-1926 Wehner moved into Mühsam's apartment and worked on his newspaper “ Fanal ”. During this time, Wehner was also active as a speaker for the Anarchist Association Berlin (AVB) and contributed to the newspaper “Der Freie Arbeiter”, the organ of the Federation of Communist Anarchists in Germany. In the spring of 1927, however, Wehner turned against Mühsam, because he refused to work as a journalist in the “Fanal”. After Wehner moved out in March, Mühsam accused Wehner of stealing the cash register and the membership files of the AVB.

In 1927 Wehner became a member of the KPD and in the same year full-time secretary of the Red Aid of Germany in Dresden. A rapid rise followed within the party organization. He was elected to the Saxon state parliament in June 1930 and there, supported by Rudolf Renner , the political leader of the KPD district of Saxony, immediately deputy chairman of the parliamentary group. Wehner also assumed important functions in the Saxon party organization from 1929 onwards. This rapid ascent ended abruptly when Renner was replaced in February 1931. At the beginning of March 1931, the new district chief Fritz Selbmann not only ensured that Wehner was removed from all party functions, but also that he was recalled from Saxony. In June 1931 - after repeated requests from the party - Wehner also resigned his seat in the state parliament and moved to Berlin. There he received no political party function, but took on subordinate tasks as an employee of the organizational department of the Central Committee headed by August Creutzburg for a year before he was appointed Technical Secretary of the Politburo in July or August 1932. As such, he prepared the meetings of the Politburo and kept the minutes.

After the Reichstag fire , Wehner went underground, where, as head of the “liaison system”, he was responsible for passing on the party leadership's instructions to the party districts. By autumn 1933, all leading members of the KPD, with the exception of Thälmann's successor John Schehr, left Germany. The domestic line still used by Schehr in October 1933 included Wilhelm Kox , Siegfried Rädel , Robert Stamm , Lambert Horn and a few others as well as Wehner. As senior advisor, Wehner headed important party districts such as Berlin-Brandenburg and Wasserkante. From June 1934 he worked in the same position in the Saar area , where he worked with Erich Honecker , the senior advisor responsible for the KJVD . In 1935 Wehner was arrested in Prague and deported to the Soviet Union . Here he took part in the VII World Congress of the Communist International . Wehner, the 1934/35 the group around Walter Ulbricht and Wilhelm Pieck during the clashes with the "left" majority of the party leadership ( Hermann Schubert , Fritz Schulte , Wilhelm Florin , Franz Dahlem had and others) support, was presented at the conference in Brussels in the Central committee elected and at the same time candidate of the Politburo. He left the Soviet Union in November 1935 with the task of implementing the new political line in the KPD section leadership in Western Europe.

Moscow exile (1937 to 1941)

In January 1937, Wehner was ordered to Moscow . His code name, under which he also published a number of articles in the German-language party newspaper Deutsche Zentral-Zeitung (DZZ) appearing in Moscow , was Kurt Funk . He lived in the emigrant hotel Lux . Wehner escaped Stalin's Great Terror , to which many German communists in exile fell victim. Historical research has shown that he, for his part, made material available to Soviet agencies in Moscow on the political “misconduct” of German communists who then fell victim to the Great Terror.

The incriminating documents in Moscow were documented in two books by Reinhard Müller and then by Spiegel after Wehner's death. The most important facts concern the following people:

- Helmut Weiß , a young Jewish writer from Dresden who had emigrated to Moscow and a member of the KPD, was sentenced to ten years in the Gulag after Wehner had called on the “appropriate authority”, which, according to the circumstances, was called the Stalinist secret police NKVD , to call Weiß and his “harmful Book "to examine.

- In 1937, Wehner at the NKVD charged seventeen people in the USSR under pressure to be connected to the Wollenberg - Laszlo district in Prague. He exposed them to the risk of arrest, banishment and possibly shot.

- Also Grete Wilde and George Brückmann (code name: Albert Müller), the members of the Executive Department of the Communist International (Comintern) had been, in turn, Wehner had loaded. In return, Wehner accused them of "violating vigilance for the protection of the Soviet Union" and against "hostile elements" as well as an "unusually liberal attitude towards highly suspicious persons". Wilde died in a prison camp in 1943; Brückmann's trail of life is lost in the gulag .

- Leo Flieg was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of the USSR on March 14, 1939, and executed in Moscow a day later

- Erich Birkenhauer , former secretary of Ernst Thälmann, whom Wehner had alleged complicit in Thälmann's arrest, was executed on September 8, 1941 in Orjol.

- Hugo Eberlein was shot dead in Moscow on October 16, 1941.

- Wehner repeatedly drew attention to Max Diamant , a member of the SAP management and confidante of Willy Brandt, in the “expertise” required of him . Wehner denounced him as a "determined Trotskyist , dangerous and conspiratorial". The NKVD could not get hold of him because he was in exile in France, but - as Wehner also informed the secret service - his parents Michail and Anna Diamant lived in the USSR. The father was arrested in 1937 and died.

Exile in Sweden (1941 to 1945) and return

In 1941, Wehner traveled to Sweden, which was neutral at the time, on behalf of the party . From there he was supposed to be smuggled to Germany by means of informers in order to organize the communist resistance against National Socialism there. In 1942 he was arrested in Stockholm and sentenced to one year in prison for espionage and then, on appeal, to one year in prison. One of his cell neighbors in Långholmen Central Prison was Arno Behrisch .

It is often assumed that Wehner used the Swedish prosecution to evade the party mandate to organize the communist resistance in Germany. Thereupon he was expelled from the KPD by the Politburo of the KPD under the direction of Wilhelm Pieck . During his internment, according to his own admission, he broke with communism .

In 1946 he returned to Germany and immediately became a member of the SPD in Hamburg. Here he also worked as an editor for the social democratic newspaper Hamburger Echo . He soon belonged to the closest circle around SPD chairman Kurt Schumacher . In 1948 Wehner became a member of the district executive committee of the SPD in Hamburg.

Member of the Bundestag and Federal Minister

In the 1949 federal election he was elected to the German Bundestag as a member of the Hamburg VII constituency. For this constituency (later called Harburg or Bundestag constituency Hamburg-Harburg ) he was directly elected member of the Bundestag until 1983. He was also deputy chairman of the SPD parliamentary group from 1957 to 1958 and from 1964 to 1966 . From 1958 to 1973 he was also Deputy Federal Chairman of the SPD.

From 1949 until his appointment as Federal Minister in 1966, Wehner was chairman of the Bundestag committee for all German and Berlin issues, and from June 1956 to 1957 deputy chairman of the committee for foreign affairs. From 1953 to 1966 Wehner chaired the working group for foreign policy and all-German issues of the SPD parliamentary group.

From 1952 to 1958 Wehner was also a member of the European Parliament .

On Wehner's idea, June 17th was also the day of German unity . After the uprising of June 17 , the CDU / CSU parliamentary group proposed a “National Day of Remembrance” on June 24, 1953, and just a few days later the SPD demanded that June 17 be elevated to a “national holiday”. In a committee meeting on July 2, 1953, the CDU, led by Konrad Adenauer , initially spoke out against the holiday. June 17th should only be a national day of remembrance for the German people. The opposition SPD, led by its committee chairman Herbert Wehner, insisted on the introduction of a public holiday. It was Herbert Wehner who suggested the name “Day of German Unity”.

Wehner was largely involved in the internal party implementation of the Godesberg program , through which the SPD finally turned away from Marxism in 1959 and also developed programmatically into a people 's party . With his keynote address in front of the Bundestag on June 30, 1960, he also heralded the SPD's change of course in foreign policy towards ties to the West and recognition of membership in NATO .

In the cabinet of the grand coalition under Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger , Wehner became Federal Minister for All-German Issues in 1966 ; in this office he had a considerable share in the ransom of political prisoners from the GDR . In 1966, Wehner was ready to support the majority suffrage for the formation of the grand coalition , which the SPD had traditionally opposed. The SPD party congress of 1968 postponed the reform, however. Like Erich Mende, many may have seen Wehner's “brilliant move” in the behavior of the Social Democrats: The SPD leadership deceived the Union about the electoral reform in order to get into the government.

The social democratic chief strategist was actually not to blame for irritations about his attitude. Even after the 1969 Bundestag election , Wehner maintained that he was in favor of a relative majority vote, but at the same time insulted the CDU's desire for a joint between the grand coalition and electoral reform, for example in an interview on the evening of the 1969 Bundestag elections with the oft-quoted words: "... that was Already nonsense before the election and that’s still 'nonsense' ... after the election. "

Chairman of the SPD parliamentary group 1969–1983

Wehner would have liked to continue the grand coalition with the Union after 1969 as he was not sure whether his party would be able to take on the role of the leading government partner. But he loyally followed Brandt's course of a social-liberal coalition and moved from the cabinet to the head of the SPD parliamentary group. He stayed there for the entire duration of this coalition. He quickly gained the reputation of a "disciplinarian" who kept the parliamentary group at the side of the government led by Chancellor Brandt.

Wehner played a part in the fact that Brandt did not lose his office despite a narrow and crumbling parliamentary majority. When CDU leader Rainer Barzel tried to be elected Chancellor by the Bundestag in April 1972 , Wehner ordered the parliamentary group to stay away from the vote. With one exception, only members of the government of the SPD voted. In this way, Wehner prevented the opposition from buying votes among members of the parliamentary group that he feared. In the end, contrary to expectations, Barzel was missing two votes for the necessary majority and three votes for his previous calculations. Wehner himself admitted in a television interview in 1980 that this success had not been legally achieved, but did not want to comment on the more precise circumstances:

“I don't think about it because then the special side of our democracy comes to light; then I'm dragged on to courts. No, no, this was dirty, and you had to know that. A group leader needs to know what is happening and what is being tried to pull the rug out from under a government. The government itself does not have to know any of this. "

However, Wehner was not necessarily satisfied with Brandt's administration. Especially after winning the Bundestag election at the end of 1972 , the rounding off of the New Ostpolitik and the stalling of domestic reforms (also for financial reasons, see 1973 oil crisis ), Brandt seemed to have lost his original vigor.

When Brandt came under pressure in 1974 in the course of the Guillaume affair , Wehner's attitude seemed to have had a major influence on Brandt's resignation. Brandt could have remained Chancellor, and Wehner promised to support him if Brandt was fighting for his office. It is sometimes claimed that Brandt feared that the GDR had incriminating material about his way of life. In any case, on the occasion of Brandt's resignation, the difference between a Brandt supporter like Egon Bahr , who shed tears, and Wehner, to whom the participation of the SPD in government was more important than Brandt's chancellorship, was clear to the public . Wehner's remarks “The Lord likes to bathe lukewarm” and “What the government lacks is a head” have been handed down to us. The statement “The gentleman likes to bathe lukewarm” is said to have only been made in a confidential circle on the return flight and the headline “What the government lacks is a head” was a mutilating of a longer relative clause that distorted the meaning.

According to Egon Bahr, Wehner is said to have even worked against Brandt with Erich Honecker to ensure “that the division of Germany was preserved indefinitely”. Hans-Jürgen Wischnewski is said to have said as an ear witness of a telephone call from Honecker to Wehner zu Bahr: “You, According to the way the uncle (note: Wehner is referring to) spoke, I don't know where his loyalty lies. ”Brandt remained party chairman, Federal Minister Helmut Schmidt took over the chancellorship, both of which Wehner is said to have wanted.

On 30./31. May 1973 Wehner traveled together with FDP parliamentary group leader Wolfgang Mischnick to a secret meeting with Erich Honecker in the GDR. At Hubertusstock Castle in Schorfheide , humanitarian issues relating to German-German relations were discussed. In that year Wehner also initiated the establishment of the Working Group for Employee Issues (AfA) in order to give the interests of employees in the SPD people's party a sharper profile again.

The 1980 selected ninth German Bundestag he was a senior member of. Wehner belonged to Ludwig Erhard , Hermann Götz , Gerhard Schröder (all CDU ), Richard Jaeger , Franz Josef Strauss , Richard Stücklen (all CSU ), Erich Mende (FDP, later CDU), Erwin Lange and R. Martin Schmidt (both SPD) one of the ten members of parliament who have belonged to parliament without interruption for the 25 years since the first federal election in 1949 .

With the break of the social-liberal coalition on September 17, 1982 and the election of Helmut Kohl as Federal Chancellor on October 1, 1982, Wehner served as opposition leader for a few weeks . As a result of the change of government, there were new elections in March 1983 , in which Wehner no longer ran for the Bundestag for reasons of age and health. The SPD candidate for chancellor was Hans-Jochen Vogel , who succeeded him as parliamentary group leader and opposition leader after the election.

rhetoric

Wehner is the member of the Bundestag with the most calls to order . He came in the Bundestag - depending on the source - 57 or 58 warnings. If the complaints as a communist member of parliament are counted during his membership in the Saxon state parliament in 1930/31, Wehner even comes to 75 parliamentary administrative offenses.

On March 22, 1950 he was expelled from the Bundestag President Erich Köhler for ten days of unparliamentary behavior. A group of SPD MPs led by Wehner and Rudolf-Ernst Heiland had chased away MP Wolfgang Hedler , who had been conspicuous for anti-Semitic remarks and who had been excluded from the plenary due to constant disturbances, from the quiet room for MPs. Hedler fell down a flight of stairs and was slightly injured. As an excluded MP, Hedler should not have been in the quiet room.

Wehner dubbed the CDU member Jürgen Wohlrabe as "Mr. Evil Crow", Jürgen Todenhöfer as "testicle killer". Wehner recommended that the SPD MP Franz Josef Zebisch , who complained about the alphabetical distribution of seats that was still common in the 1960s, rename himself “Comrade Asshole”.

Wehner's speeches were criss-crossed with long, nested sentences that were repeatedly interrupted by eruptive utterances. When the CDU / CSU parliamentary group left the plenary hall on March 13, 1975 during his speech in a debate on internal security in protest, the call he made to the parliamentary group became a much-cited expression: “Whoever goes out must come in again! I say cheers to you because you will probably go there [ie to the pub]. ”Before that, Wehner had accused the CDU / CSU parliamentary group:“ When you hear the word Marxist , you feel the way Goebbels operated with it, no different. You are just as stupid on this as it was; only he was very refined Jesuit . "

Against this background, Karl Carstens (CDU) angrily called Wehner the “greatest scold of the whole Bundestag”, and the former CDU General Secretary Heiner Geißler called him - rather appreciatively - the “greatest parliamentary howitzer of all time”.

Journalists were also occasionally victims of his rhetoric: Wehner addressed the ARD reporter Ernst Dieter Lueg during an interview on the evening of the 1976 federal election as “Mr. Lüg” instead of using the correct pronunciation ([ luːk ]) that was widely known at the time. The reporter returned the favor with the words: "Thank you (...) Mr. Wöhner (...)."

During a Bundestag debate in March 1980, he defied the CDU parliamentary group leader at the time , Helmut Kohl , with the swear word he had created himself, “ Düffeldoffel ”.

Honors

In 1973 Wehner received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany , and in 1985 the Hans Böckler Prize . Wehner was made an honorary citizen of Hamburg in 1986, where he had been directly elected member of the Bundestag for Harburg from 1949 to 1983. In 2000, part of a street in the Hamburg-Harburg district was renamed Herbert-Wehner-Platz , on which a plaque on the wall commemorates Wehner. In 2006 a square in Bad Godesberg was named after him, as was the case in 2001 in his hometown of Dresden near the Altmarkt . There is a memorial and a plaque in Spenerstrasse to commemorate the politician. Since 2010, Wehner's grave in the castle cemetery in Bad Godesberg has been an honorary grave of the city of Bonn. The Herbert-Wehner-Bildungswerk in Dresden is named after him, the party headquarters of the Saxon SPD, which is under construction in 2018, will be called Herbert-Wehner-Haus. - In 2000 Wehner was one of the "100 Dresden residents of the 20th century" in the daily newspaper Dresdner Latest News .

Herbert Wehner Medal

From 1997 to 2013 the trade union ver.di Hamburg - previously the Deutsche Postgewerkschaft , Hamburg region - awarded the Herbert Wehner Medal, endowed with 2000 euros, every two years . With the award, the union honored institutions and people who are committed to fighting right-wing extremist activities, xenophobia and indifference, who have become role models through their commitment and personal courage, and who thus contribute to democracy in Germany.

Works

- Roses and thistles - evidence of the struggle for Hamburg's constitution and Germany's renewal in the years 1848/49. Publishing house Christen & Co., Hamburg 1948.

- Our nation on democratic probation. In: Youth, Democracy, Nation. Bonn 1967, pp. 19-32.

- Bundestag speeches. With a foreword by Willy Brandt , 3rd edition, Bonn 1970.

- Bundestag speeches and contemporary documents. Foreword by Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt , Bonn 1978.

- Change and probation. Selected speeches and writings 1930/1980. (Ed. By Gerhard Jahn , introduction by Günter Gaus .) Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-550-07251-1 .

- Testimony. (Ed. By Gerhard Jahn.) Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-462-01498-6 .

- Self-determination and self-criticism. Experiences and thoughts of a German. Written down in custody in Sweden in the winter of 1942/43. (Ed. By August H. Leugers-Scherzberg , preface Greta Wehner .) Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-462-02340-3 .

- Christianity and Democratic Socialism. Contributions to an uncomfortable partnership. Edited by Rüdiger Reitz, Dreisam Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 1985, ISBN 3-89125-220-X .

literature

- Egon Bahr : Chapter “Wehner” in: You have to tell. Memories of Willy Brandt. Pp. 149–158, Propylaeen, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-549-07422-0 .

- Cicero. Magazine for political culture : special issue “Herbert Wehner” (articles by: Klaus Harpprecht , Nina Hermann, Vanessa Liertz), Potsdam, September 2004, ISSN 1613-4826 / ZKZ 63920.

- Helge Döhring: The anarchist Herbert Wehner. From Erich Mühsam to Ernst Thälmann. In: FAU-Bremen (Ed.): Class struggle on a world scale. From the series: Syndicalism - History and Perspectives. Bremen 2006.

- Ralf Floehr, Klaus Schmidt: Unbelievable, Mr. President! Order calls / Herbert Wehner. la Fleur, Krefeld 1982, ISBN 3-9800556-3-9 .

- Hans Frederik: Herbert Wehner. The end of his legend. VPA, Landshut 1982. ISBN 3-921240-06-9 .

- Reinhard Müller : Herbert Wehner. Moscow 1937. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-930908-82-4 .

- Reinhard Müller: The Wehner files. Moscow 1937 to 1941. Rowohlt, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-87134-056-1 .

- Reinhard Müller: Herbert Wehner. A typical career of the Stalinized Comintern? Also an anti-criticism. In: Mittelweg 36, Vol. 14, 2005, H. 2, pp. 77-97.

- Reinhard Müller: Denunciation and Terror: Herbert Wehner in Exile in Moscow. In: Jürgen Zarusky (Ed.): Stalin - an interim balance from a German perspective. New contributions from research, Munich 2006 (= series of quarterly journals for contemporary history ), pp. 43–57.

- Knut Terjung (Ed.): The uncle. Herbert Wehner in talks and interviews. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-455-08259-9 .

- To the biography

- Claus Baumgart, Manfred Neuhaus (ed.): Günter Reimann - Herbert Wehner. Between two eras. Letters 1946. Kiepenheuer, Leipzig 1998, ISBN 3-378-01029-0 .

- Friedemann Bedürftig (Ed.): The suffering of young Wehner: Documented in a pen friendship in turbulent times 1924–1926. Parthas, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86601-059-1 .

- August H. Leugers-Scherzberg : The change of Herbert Wehner. From the Popular Front to the Grand Coalition. Propylaea, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-549-07155-8 .

- Christoph Meyer: Herbert Wehner. Biography. dtv, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-423-24551-4 .

- Günther Scholz: Herbert Wehner. Econ, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-430-18035-X .

- Michael F. Scholz : Herbert Wehner in Sweden 1941–1946. Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-64570-6 .

- Hartmut Soell : The young Wehner. Between revolutionary myth and practical reason. DVA, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-421-06595-0 .

- Wolfgang Dau, Helmut Bärwald , Robert Becker (Eds.): Herbert Wehner. Time of his life. Becker, Eschau 1986, ISBN 3-925-72510-5 .

- Wehner, Herbert . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945. 2., revised. and strong exp. Edition. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

Films about Herbert Wehner

- Wehner - the untold story , docu-drama , 1st part: The night of Münstereifel , 102 min., 2nd part: Hotel Lux , 106 min., 1992/93, script and director: Heinrich Breloer , production: WDR , NDR , First broadcast: ARD , March 31, 1993, with Ulrich Tukur as the young Wehner and Heinz Baumann as the old Wehner.

Audiobook about Herbert Wehner

- You duffel here! by Jürgen Roth , narrator Gert Heidenreich with contributions by Thomas Freitag , Herman L. Gremliza and Dieter Hildebrandt and numerous original recordings. 159: 43 minutes, Verlag Antje Kunstmann GmbH, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-88897-694-0

Web links

- Literature by and about Herbert Wehner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Herbert Wehner in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Irmgard Zündorf: Herbert Wehner. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Christoph Meyer: Wehner, Richard Herbert . In: Institute for Saxon History and Folklore (Ed.): Saxon Biography . December 19, 2005

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Günter Gaus : in conversation with Herbert Wehner (1964) accessed on March 14, 2020.

- Jürgen Kellermeier : Interview with Herbert Wehner. November 26, 1978. Video in: Norddeutscher Rundfunk , October 7, 2009.

- Herbert-Wehner-Bildungswerk Dresden

- Herbert Wehner Archive in the Archive of Social Democracy of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (Bonn)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Herbert Wehner. In: Who's who.

- ↑ Remembering the victims of the Nazi tyranny - stumbling blocks in front of the former Gestapo headquarters. In: Website of the City of Hamburg, press archive, February 25, 2009 (article with information on the death of Carl Burmester).

- ↑ Christian Herrendörfer: tactician, disciplinarian, carter. ARD, July 7, 1986, accessed on February 25, 2018 (relevant part of the video at 23:19 min.).

- ^ Meyer: Herbert Wehner. 2006, p. 476.

- ↑ Previous memorial acts. State files of mourning at federal level since 1954. ( Memento of the original from August 8, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Federal Ministry of the Interior, January 1, 2012 (Mourning Act for Wehner on January 25, 1990).

- ↑ Jürgen Jenko: The anarcho-syndicalist movement (FAUD) in Dresden, Bochum 2004, master's thesis, p. 61.

- ^ Helge Döhring: No commands, no obedience !, The history of the syndicalist-anarchist youth since 1918, a propos publishing house, Bern, 1st edition 2011, pp. 199–205.

- ↑ See Meyer, Christoph, Herbert Wehner. Biography, 3rd edition Munich 2006, p. 49.

- ↑ See Müller, Reinhard, Herbert Wehner - Moscow 1937, Hamburg 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ See Mammach, Klaus, Resistance 1933–1939. History of the German anti-fascist resistance movement at home and in emigration, Cologne 1984, p. 48.

- ↑ See Scholz, Michael F., Herbert Wehner in Schweden 1941–1946, Berlin 1997, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ See Müller, Moscow 1937, p. 57.

- ↑ Reinhard Müller: Picky attention to detail. Reinhard Müller on Christoph Meyer's Wehner biography. In: Der Spiegel . Special, 7/2006.

- ^ Document 18: Herbert Wehner: Records for the NKVD. December 13, 1937. In: Herbert Wehner Moscow 1937. Reinhard Müller, Hamburg 2004, pp. 469 and 482.

- ↑ On Brückmann see Reinhard Müller: Die Wehner. Moscow 1937 to 1941. Berlin 1993, p. 399.

- ↑ a b c Uwe Bahnsen : Wehner's picture gets scratches Die Welt, June 2, 2013

- ^ Müller, Reinhard: Herbert Wehner - Moscow 1937, Hamburg 2004, pp. 492, 493

- ↑ Christoph Meyer: Herbert Wehner and June 17th. In: HGWSt.de , January 13, 2012.

- ↑ dip21.bundestag.de (pdf, full text)

- ↑ see also Der Spiegel 39/1963, page 39 and interview in the same issue (pp. 38 to 50).

- ↑ Erich Mende: The FDP. Data, facts, background. Stuttgart 1972, p. 229.

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , September 29, 1969, p. 1.

- ↑ Herbert Wehner Interview 1969 election evening on YouTube .

- ↑ Andreas Grau: In search of the missing votes 1972. On the aftermath of the failed vote of no confidence in Barzel / Brandt. Historical-Political Messages, Archive for Christian Democratic Politics, Böhlau Verlag Cologne, No. 16, December 30, 2009, p. 4 (PDF; 108.56 kB).

- ^ Manfred Görtemaker : History of the Federal Republic of Germany. From the foundation to the present . CH Beck, Munich 1999, pp. 553-554.

- ^ Alfred Cattani: Herbert Wehner - controversial to this day. In: nzz.ch. July 22, 2006, accessed February 25, 2018 .

- ↑ "What the government lacks is a head" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 41 , 1973 ( online ).

- ↑ Christoph Meyer: The Myth of Treason. Wehner's Ostpolitik and the mistakes of Egon Bahr. In: bpb.de. December 19, 2013, accessed February 25, 2018 .

- ↑ Bahr: You have to tell. 2013, p. 155.

- ↑ Bahr: You have to tell. 2013, p. 156.

- ↑ a b With foil and mallet ( Memento from December 30, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). In: Text archive of the German Bundestag.

- ^ A b Günter Pursch : Even members of parliament are only human ... The culture of political debate in 50 years of the German Bundestag . In: Blickpunkt Bundestag No. 07/1999 ( version in the web archive of the German Bundestag 2006 ).

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Politics of the Past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. 2nd edition, Munich 1997, p. 318.

- ^ The Goebbels comparison by Herbert Wehner on YouTube , March 13, 1975.

- ↑ Negotiations of the German Bundestag, 7th electoral period, Stenographic Reports, Vol. 92, 155th Session, p. 10839.

- ↑ Heiner Geißler: Goldene Ente 2003. Laudation for Ottmar Schreiner. In: State press conference Saar.

- ↑ Herbert Wehner vs Mr. Lüg Lueg on YouTube , October 3, 1976 (interview with Ernst Dieter Lueg).

- ↑ Peter Köhler : The best quotations from politicians: More than 1,000 concise sayings. Ingenious and curious. Schlütersche, 2008, p. 193.

- ↑ Announcement of awards of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. In: Federal Gazette . Vol. 25, No. 43, March 9, 1973.

- ^ Christoph Meyer: Wehner, Richard Herbert. In: Saxon Biography , December 19, 2005.

- ↑ Dresden now has a Herbert-Wehner-Platz. In: HGWSt.de , July 12, 2001.

- ↑ Honorary grave for Herbert Wehner. In: HGWSt.de , September 10, 2010.

- ↑ Start of construction for the Wehner house. ( Memento of the original from August 2, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Sächsische Zeitung , May 29, 2017.

- ↑ 100 Dresden residents of the 20th century . In: Dresdner Latest News . Dresdner Nachrichten GmbH & Co. KG, Dresden December 31, 1999, p. 22 .

- ↑ There is no resistance without memory: Herbert Wehner Medal. In: Hamburg.verdi.de , November 26, 2013.

- ↑ The model of Herbert Wehner. ver.di recognizes anti-fascist engagement. In: website of ver.di - United Service Union, June 28, 2011.

- ↑ Date of conversation after Christoph Meyer: Who was Wehner really? Introductory lecture, Herbert-Wehner-Bildungswerk, July 11, 2014, p. 6 (PDF). There are also other information according to which the conversation should have been conducted in 1979 or 1980, for 1979 the NDR website, for example OCLC 313712142 , Der Spiegel or Wolfgang Gödde for 1980 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wehner, Herbert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wehner, Herbert Richard (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politicians (KPD, SPD), MdL, MdB, MdEP |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 11, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dresden |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 19, 1990 |

| Place of death | Bonn |