Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli (also Huldreych , Huldreich and Ulrich Zwingli ; born January 1, 1484 in Wildhaus ; † October 11, 1531 in Kappel am Albis ) was a Swiss theologian and the first Zurich reformer . The Reformed Church emerged from the Zurich and Geneva Reformations (→ Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Switzerland ).

His theology was carried on in the second generation by Heinrich Bullinger and Johannes Calvin .

Names

Contrary to some popular assumptions, Zwingli's baptismal name in memory of Saint Ulrich of Augsburg is "Ulrich". Only with time did Zwingli himself begin to change his first name to Huldrych (also Huldreich or Huldrich); this probably as a humanistic - folk etymological gimmick and contrary to the linguistic etymology, according to which Ulrich is derived from Old High German uodal " Erbbesitz " and rīch "mighty".

According to Heinrich Bruppacher, the family name "Zwingli" is a name for a residence for the not uncommon locality name "Zwing, Twing", which also occurs in Toggenburg and originally referred to a " fenced in piece of land". This declaration was also taken up again by Ulrich Gäbler . Ulrich Zwingli himself sometimes thought of “Zwilling” or “Zwinge” and therefore called himself humanistic in some texts - Latinized “Geminius” or “Cogentius”. Martin Luther and other opponents, on the other hand, sometimes spoke of the "Zwingel", since he forced the Holy Scriptures in his sense.

biography

Birth and education

Ulrich Zwingli was the son of the farmer and Ammann Johann Ulrich Zwingli (1454–1513) and Margaretha Bruggmann (around 1458–1519), widowed Meilin, who was married to Zwingli for the second time, as the third child of his parents. The house where he was born is now a museum.

Zwingli had at least nine siblings. Zwingli left his home village of Wildhaus in Obertoggenburg at the age of six and lived for the next four years as a student with his uncle, the dean Bartholomäus Zwingli, in Weesen . In 1494 he switched to the Latin school in Basel and later to the Latin school in Bern . Because of his great musicality, the Dominicans would have liked to take him into their monastery there, but his father was against it.

Zwingli left Bern in 1498 and began studying at the University of Vienna at the age of fifteen ; there he enrolled as «Vdalricus Zwinglij de Glaris». He studied at the artist faculty , where he received a kind of basic training in the seven liberal arts ( septem artes liberales ) after the then usual course . In the summer semester of 1500 he appeared a second time, this time as "Vdalricus Zwingling de Lichtensteig" in Vienna.

Under the same name he can be found in 1502 at the University of Basel and his actual theology studies began. From 1502 to 1506 he studied there and graduated with the title Magister artium . After completing his master's degree, he studied theology for another six months and then, like many of his contemporaries, switched to church practice without having completed a theology degree . Zwingli was ordained a priest in September 1506 .

Pastor in Glarus (1506–1516)

In the late summer of 1506, Zwingli was elected the leading pastor in Glarus as "Lord of the Church" . On September 21, 1507, he was introduced to his office with a solemn dinner. There were probably various reasons why the 22-year-old Magister was appointed. For one thing, Zwingli was probably recommended to them. On the other hand, the people of Glarus wanted to choose their priest themselves and not accept the proposal of the Bishop of Constance . In fact, the influential Zurich canon of the Zurich Provost, Heinrich Göldi (1496–1552), was supposed to take over the profitable benefice , d. H. receive the income of the parish from the bishop. Göldi had already transferred a considerable sum to Constance. Göldi would have become the owner of the benefice and formally pastor of Glarus, but he did not want to move to Glarus, as he viewed the position and its income merely as an investment. The people of Glarus were not interested in a benefice hunter, which is why they urgently needed their own candidate, who they found in Zwingli. After Zwingli was elected, it became difficult for Göldi to take over the pastoral office against the will of the Glarus people. In order not to go away empty-handed, Göldi asked for a high severance payment. Zwingli had to borrow money from the Glarnern to do this, and paying off the loan bothered him for a long time.

When it came to lending, the people of Glarus were quite generous. They seem to have been a little less accommodating at the rectory ; the people of Glarn were clearly aware of its inadequacies. When Zwingli asked for his release in 1516, they promised him, if he stayed, that they would build a better rectory.

The Glarus parish included several villages, in addition to Glarus Riedern , Netstal , Ennenda and Mitlödi . Together with Riedern, the main town had around 1300 inhabitants. Zwingli was responsible for the spiritual care together with three or four chaplains . Little is known about Zwingli's activities in Glarus. The few testimonies reveal no criticism of the church. He read mass and gave absolution . In 1512 he wrote to Pope Julius II and asked for indulgences for the people of Glarus. Zwingli was also a field preacher and took part in the campaigns of the Italian wars from 1512 to 1515 , in particular the battle of Marignano , the Glarus for the Pope against the French in Lombardy .

The farmer's son Zwingli seems to have been very close to the people. In the course of time he got to know all of his churchmates. Zwingli had found more than just official access to individual families. So the clergyman took on the sponsorship of various children. Zwingli's unbroken ecclesiasticalism is also evident in his efforts to bring an alleged splinter of Christ's cross to Glarus, which he succeeded in doing. The old Glarus parish church had to be expanded in order to keep the splinters worthy. Zwingli also campaigned for this with success. In 1510 the cross chapel, which got its name from this splinter of the cross, was added. The Glarus people spoke for a long time about the Zwingli Chapel and not the Kreuzkapelle.

During the Glarus years, Zwingli underwent intensive training. With great zeal he studied many works of the ancient classics and the Church Fathers . He also learned Greek and was able to read the original text of the New Testament , which Erasmus of Rotterdam had published in a critical edition in 1516. Through the humanist Erasmus, Zwingli learned to look for and recognize a different meaning in the biblical texts. Thereby he found a new, liberating approach to the Holy Scriptures . Despite the seclusion of the Glarus mountain valley, Zwingli was in close contact with the scholars of his time and was therefore always informed about the publication of new books. At the end of his time in Glarus, Zwingli owned the then significant number of over 100 books.

Zwingli wanted to pass on his knowledge. At his instigation, the rural community agreed in 1510 to found a Latin school . At this secondary school the boys were able to acquire a basic knowledge of Latin and did not have to attend a school abroad. Zwingli was elected teacher. Zwingli's students included a number of important Glarus people: Valentin Tschudi , Zwingli's successor in Glarus, Aegidius Tschudi , chronicler and politician, and probably also Fridolin Brunner , who later became the reformer of Glarus .

In the Glarus and federal politics at the beginning of the 16th century there was a heated argument as to whether they should work with the Pope, the Emperor or the French. In Glarus, the main focus was on whose service the young people of Glarus should enter as mercenaries . Zwingli always took the side of the Pope, whereupon he showed his appreciation with an impressive papal pension of 50 guilders . Zwingli, who was there as chaplain of the approximately 500 Swiss soldiers, urged unity in a sermon on September 7, 1515 in Monza . In October 1515, after the defeat against the French in the Battle of Marignano , which was devastating for the Swiss , the federal policy of great power ended. Afterwards the French agreed with the Confederates in the "Eternal Peace" of 1516 an advantageous peace that lasted until the French invasion of 1798 : The Confederates received a large sum from France, received privileges in trade with France and the Duchy of Milan and enjoyed an economically advantageous one Pay alliance. Zwingli voted against it and continued to support the French opponent, the Pope. In Glarus as in the Confederation , the mood turned in favor of the French party. The position of the papal party man and propagandist Zwingli therefore became untenable.

Zwingli had to give way in 1516 despite great support from the population and was given leave for three years.

Folk priest in Einsiedeln (1516–1519)

In 1516 Diebold von Geroldseck appointed Zwingli as a people priest and preacher in the Maria-Einsiedeln monastery, famous as a place of pilgrimage , where he began on April 14, 1516. In view of the abuses of popular piety there, he began to preach against pilgrimages and the papal indulgence preacher Bernhardin Samson , who had been in Switzerland since 1518 . He even called on the Bishops of Morals and Constancy to improve the Church according to the guidance of the divine Word. At the same time, however, based on his experiences in the Italian campaign, he also took up the cause of the demoralization of the people through the so-called Reislauf , as the Swiss military service in foreign pay was called at that time. As a consequence of his participation in the war in Lombardy, he took over Erasmus' conviction: "The war seems sweet to the uninitiated" - "Dulce bellum inexpertis" , a sentence that Zwingli used in his proverbs of Erasmus of Rotterdam .

After the waves, which Zwingli had to leave Glarus for , had smoothed out, he should have taken over the pastoral office there again; but in 1519 he decided to accept an appointment at the Zurich Grossmünster instead. The intensive studies and his experiences in Glarus as well as in Einsiedeln had changed the priest, who had previously been very loyal to the church. The development that had started in Glarus took Zwingli in new directions, and he became a sharp critic of the ecclesiastical situation at the time.

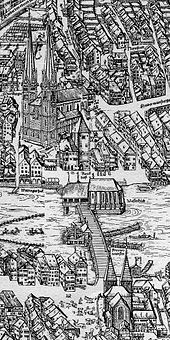

Folk priest at the Grossmünster in Zurich (1519–1531)

Since the Zurich government, like Zwingli, was against mercenaries, this attitude gave him the influential office of people priest at the Grossmünsterstift in Zurich, which he assumed on January 1, 1519. At that time, the Grossmünsterstift was the most prestigious religious monastery in the Diocese of Constance after the cathedral. In his artless but clear, generally understandable sermons, he continuously interpreted the Gospels . The people and the council of Zurich were convinced of this. All preachers in town and country were instructed by the authorities in 1520 to preach the gospel according to Zwingli's interpretation.

In 1519 a plague epidemic broke out in Zurich, which also affected Zwingli in September of that year. He survived the disease but was weak for a year. The experience of illness stimulated him to write poems and songs and is said to have shaped his understanding of God, as he traced his recovery back to God's work.

In 1522 Zwingli published his first Reformation pamphlet against fasting in the Roman church: On discovery and freedom of food . He wrote this work on the occasion of breaking the fast with his friend, the book printer Christoph Froschauer . Zwingli himself was present at the " sausage dinner " after Ash Wednesday, but not involved. With the writing that Froschauer published thousands of times after Easter, Zwingli justified the action, since keeping the fast violates the Christian faith. He pointed out that even in the Catholic Church there is an exception that allows hard-working people to bypass the fasting rules. Christian freedom seemed more important to him than the prohibition of wine and meat, which was an invention of the bishops. Only the words and deeds of Jesus are binding in the church.

He sent the Bishop of Constance a modest and emphatic petition in which he and ten of his comrades declared that they were "firmly resolved with God to preach the gospel without ceasing" and in which they asked for celibacy to be lifted . At that time Pope Hadrian VI tried . nor to prevent Zwingli from taking any further steps against the Catholic Church with a letter acknowledging the piety of the reformer.

Zwingli remained closely connected to the state of Glarus. As a pastor in Zurich, he continued to correspond with various people. He dedicated the main text, Interpretation and Reasons for the Closing Speeches of 1523, to the Landsgemeindekanton . On October 12, 1522 Zwingli even preached again in the parish church of Glarus on the occasion of the primacy of his former student Valentin Tschudi . In this sermon Zwingli's change became clear. What he had previously preached to the Glarnern, he said, was not the truth. The Glarus should refrain from it. Zwingli distanced himself from his proclamation in the Glarus years from 1506 to 1516.

The three Zurich disputations (1523/1524)

When the Dominicans accused Zwingli of heresy in Zurich , the Grand Council invited all theologians who could convict Zwingli of heresy on January 29, 1523 to the first Zurich disputation on Zwingli's theses. Around 600 spiritual and secular people came to Zurich for this purpose. Since the deputies of the Bishop of Constance, namely Johann Faber , only knew how to assert the authority of tradition and the councils against Zwingli's theses , the council of Zurich awarded Zwingli the victory.

At a second religious talk held in Zurich from October 26th to 28th, 1523, there were arguments in the presence of almost 900 witnesses from federal locations about “picture service and mass”. The reason for the second Zurich disputation was the sermon against the veneration of images and the resulting iconoclasm . It was decided that the pictures should be removed within six months so that the people could be prepared for this incision by further sermons. The "iconoclasm", which did not take place suddenly in one day, also led to the " Ittinger storm ".

Another conversation on January 13 and 14, 1524, the third Zurich disputation, also eliminated the mass. In the same year, on April 19, 1524, Zwingli married the 33-year-old widow Anna Reinhart , with whom he had previously lived out of wedlock. With her he had four children: Regula (* July 31, 1524), Wilhelm (* January 29, 1526), Huldrich (* January 6, 1528) and Anna (* May 4, 1530).

The Reformation in Zurich did not only affect religion . The council, with Zwingli's advice, reorganized the school, church and marriage system and issued moral laws . Zwingli had no political office, but had great influence - the council knew that the people would listen to Zwingli's sermons. For the reformer Zwingli the support of the ruling patricians in Zurich was indispensable, he supported the expulsion and murder of so-called Anabaptists like his old companion Felix Manz . The Anabaptists rejected infant baptism as unbiblical and referred to the baptism of the adult Jesus as a contrast foil. The rejection of civil order went too far for Zwingli, he showed no mercy towards Felix Manz and the Anabaptists.

Creed (1525) and Zurich Bible

1525 Zwingli made his profession of faith "from the true and false religion" out that he the French king Francis I sent. With Luther and the other German reformers in agreement on many points, Zwingli proceeded more radically in liturgical matters and rejected the " bodily presence " of Christ in the Lord's Supper . From 1525 the Reformation and the reform of worship in Zurich were completed. The Lord's Supper was celebrated in memory in both forms. Pictures, masses and celibacy were abolished, and there was regular welfare for the poor. This was financed from funds that were released through the secularization of monasteries and spiritual foundations in the ruled area of the city of Zurich. Also in 1525, the previous canons' monastery at Grossmünster was converted into the provost's office at Grossmünster in order to ensure the training of other Reformed theologians. They had to learn Bible exegesis and present the results to the people in German sermons. This trained theologians and helped the people to become rooted in the Bible. As an antistes, Zwingli was the head of the Zurich church .

In close collaboration with Leo Jud , Zwingli re-translated the Bible into the federal language between 1524 and 1529. This translation is known today as the “ Zurich Bible ”. Accordingly, the Zurich theologians completed the complete new translation from Greek and Hebrew five years before Luther's translation of the Bible. The Zurich Bible is thus the oldest Protestant translation of the entire Bible. The work was printed by Christoph Froschauer between 1524 and 1529 . In 1531 he printed a richly illustrated and lavishly designed complete edition. For a long time, this version was the most important edition of the Zurich Bible in terms of text and design.

Politics and Marburg Religious Discussion (1529)

Zwingli rejected Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms , according to which the state was responsible for the "external" and the church for the "internal". Much more, he saw church and state in close cooperation and in this a serious obligation for the authorities. He declared that "the authorities who go beyond the cord of Christ", that is, do not want to take the prescriptions of Christ as a standard, "may be appalled with God". The Landgrave of Hesse , Philip the Generous , who shared Zwingli's far-reaching political views, organized a dispute between Zwingli and Martin Luther in his castle in Marburg , the "Last Supper Controversy in Marburg". Luther harshly rejected Zwingli, however, with the result that the plan of joint Protestant action against the emperor and the pope failed due to theological differences.

Philip the Magnanimous and Zwingli had ambitious plans. In 1530 they wanted to "save the world from the Habsburgs' grasp by a union from the Adriatic to the Belt and the ocean". At that time, Zwingli won this canton for the Reformation as early as January 1528 during a religious talk in Bern . In addition, the First Kappeler Landfrieden in 1529 seemed to have temporarily eliminated the threat of a religious war between Zurich and the five original Catholic cantons .

Death in the Second Kappel War

In 1531 there was a religious war in the Confederation, the Second Kappel War between Zurich and the Catholic cantons of Lucerne , Uri , Schwyz , Unterwalden and Zug . Old believers such as the monks, especially the mendicant orders , had already been expelled from the monasteries. It was also Zwingli who urged the Zurich Council to launch the Second Kappel War against Waldstätte in order to spread the Reformation, if not with conviction, then with fire and sword in central Switzerland . On October 11, 1531, the people of Zurich were defeated, and Zwingli himself fell into the hands of the Catholic Central Swiss during the Battle of Kappel , in which he had participated as a soldier, on the Albis. He was mocked by being offered to make confession again, and then killed. His body was quartered, then burned and the ashes scattered in the wind. Not until 1838 was a monument erected to him in Kappel and in 1885 in Zurich. Heinrich Bullinger became Zwingli's successor in Zurich. He consolidated the Reformed faith and is considered the actual founder of the Reformed Church.

Zwingli's Reformation and its effects

Zwingli's Reformation was based on different assumptions than Luther's and had clear differences in many similarities. While Luther wanted to remove the indulgence trade and other abuses in the church that contradicted his understanding of the Bible, Zwingli only accepted in the church what was expressly in the Bible. That is why the Reformed churches are even more pronounced than the Lutheran churches of the word: no church decorations except Bible verses, even music in the worship service had to be dispensed with - although Zwingli himself was very musical. Music came back to the Zwinglian churches when psalms in German began to spread from Strasbourg .

Zwingli lived as a confederate in a political system that was shaped by the local councils. Against this background, he gave the Grand Council the right to "make decisions as a representative of the parish." Heinrich Bullinger , Zwingli's successor in Zurich, reaffirmed this position by granting the “Council of the City of Zurich, composed of Christians, the right and duty” to “regulate all matters of church doctrine and life”. This relationship between the secular congregation and the church was to make a considerable difference to Geneva. There Calvin developed the idea of an independence of the church from state rule based on his experiences with conflicts between the church and the authorities in France and Geneva. Calvin's model later found greater reception because it "[better] corresponded to the persecution situation of Reformed churches".

Zwingli had a different biographical background than the other reformers. He came from a farming family. Like Melanchthon, he was shaped by humanism. But while Luther was a monk and theology professor, Calvin was a lawyer and Melanchthon professor of Greek, Zwingli had always worked as a pastor until his time in Zurich; and also in Zurich he worked as a parish priest.

The effects of Ulrich Zwingli's theology can be seen primarily in German-speaking Switzerland and in Vaud . The success of the Reformation is not without other personalities such as Heinrich Bullinger , Zwingli's successor in Zurich, Johannes Oekolampad and Oswald Myconius in Basel , Berchtold Haller in Bern, Sebastian Hofmeister and Erasmus Ritter in Schaffhausen , Joachim Vadian and Johannes Kessler in St. Gallen and Johann Comander in Graubünden is conceivable.

In Germany only the Reformed churches in Bad Grönenbach , Herbishofen and Theinselberg can be traced back directly to Zwingli's work. The other Reformed churches are - as can be seen from the Heidelberg Catechism - more strongly influenced by Calvin's thinking.

Zwingli's relationship to the Anabaptist movement is often seen as the downside of his work . At Zwingli's insistence, the Zurich Council either had all of the city's Anabaptists expelled or drowned in the Limmat after being captured and tortured . One of the first victims among the Swiss Anabaptists was Felix Manz . He was also on bad terms with Balthasar Hubmaier , who lived in nearby Waldshut in Upper Austria , and did not want to give him asylum when he fled from the Habsburgs . The persecution of the Anabaptists continued for generations. Only in 2004 did a reconciling meeting between Zurich Reformed and Anabaptists take place.

Monuments

Zwingli's best-known monument was designed by the Austrian sculptor Heinrich Natter and inaugurated on August 15, 1885 in front of the Wasserkirche in Zurich, after a design by Ferdinand Schlöth from Basel was initially planned for execution. The opening speech was given by Antistes Diethelm Georg Finsler , the official speech by Mayor Melchior Römer .

Zwingli statue at the Zwingli Church (Berlin)

Several church buildings from the 20th century are named Zwinglikirche and are reminiscent of the Reformer.

Zwinglistrassen are common. For example, in 1903 a street in Dresden was named after Zwingli, which is now also indicated by an explanation board under the street sign with further information about the person. In Berlin, Zwinglistraße in Moabit's “Reformatorenviertel” is reminiscent of Zwingli.

To the north-east of his birthplace Wildhaus, in the Alpstein massif between the cantons of St. Gallen and Appenzell Innerrhoden, lies the Zwingli Pass, which is named after him . It is accessed by hiking trails.

Zwingli had objected to being named in front or in the back of the Bible.

Portrait gallery

After Zwingli's death, numerous portraits were made, almost all of which are based on those of the Zurich painter Hans Asper . There is no portrait painted during Zwingli's lifetime. Zwingli is usually portrayed in black costume with a black "reformer hat".

Stained glass window in the Strasbourg Church of the Redeemer (detail)

Zwingli and the music

According to a contemporary chronicle, Zwingli played eleven instruments: lute , harp , Trumscheit , bagpipe , dulcimer , pipe , violin , Rebec , French horn , zinc and Schwegel . He achieved special mastery on the lute and flute, he was also referred to as "Lutenschlaher" and "Evangelical whistler".

Philatelic

With the Initial Issue 2 May 2019 which gave German Post AG and Swiss Post to commemorate a Swiss-German joint stamp Huldrych Zwingli - 500 Years of Zurich and Upper German Reformation in the nominal value of 85 cents and 150 euro cents with a picture of Zwingli and the text Does God's sake something brave! out. The design comes from the graphic artist Matthias Wittig from Berlin.

As early as 1969, the Swiss Post issued a stamp with the portrait of Huldrych Zwingli in the Famous People series with a face value of 10 cents.

See also

- List of reformers

- History of the city of Zurich

- Reformation , Reformed Churches , Evangelical Lutheran Churches , Reformation in Memmingen

- Evangelical Reformed Churches in Switzerland

- Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Switzerland

Works

- Of the ardor and fryness of the spyses […], April 1522

- Interpretation and justification of theses or articles , 1523

- From the touff. From the widertouff. And from kindertouff, 1525

- Commentarius de vera et falsa religione , 1525

- Amica exegesis, 1527

- Fidei ratio, July 1530

- Sermonis de providentia Dei anamenema, August 1530

- Christianae fidei brevis et clara expositio ad regem christianum, July 1531

- Total expenditure

- Zwingli's Complete Works first appeared in Folio, Zurich, 1545 and 1581, re-edited by Johann Melchior Schuler and Johannes Schulthess , Zurich from 1828 to 1842, 8 volumes; also supplements 1861.

- Huldreich Zwingli's complete works; the only complete edition of Zwingli's works, edited by Emil Egli with the assistance of the Zwingli Association in Zurich. 21 volumes (several of which are divided into partial volumes), Berlin / Leipzig and Zurich 1905–2013 (Corpus reformatorum 88–108).

- Huldrych Zwingli, writings. Edited by Th. Brunnschweiler et al. Theologischer Verlag, Zurich, 1995, 4 volumes

- Choose

- Edwin Künzli: Selection of his writings . Theological Publishing House Zurich, Zurich 1962.

- Ernst Saxer: Selected writings in New High German rendering with a historical-biographical introduction. Neukirchener Verlagsgesellschaft, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1988.

Remembrance day

Zwingli's day of remembrance is October 11th in the Evangelical name calendar .

literature

- Hans Ulrich Bächtold: Huldrych Zwingli, writings. Edited by Thomas Brunnschweiler and Samuel Lutz. Zwingliverein, Theologischer Verlag Zurich 1995, ISBN 978-3-290-10977-6 , Volume IV, pp. 495-497

- George Casalis : Zwingli (Ulrich) . In: La Grande Encyclopédie . 20 volumes, Larousse, Paris 1971–1976, pp. 14813–14815 (French).

- Emil Egli : Zwingli, Ulrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 45, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1900, pp. 547-575.

- Ulrich Gäbler : Huldrych Zwingli. An introduction to his life and work . Beck, Munich 1983. ISBN 3-406-09594-1 (kt.) And ISBN 3-406-09593-3 (left) (= Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1985). TVZ, Zurich 2004 3 ; ISBN 3-290-17300-3

- Martin Haas: Huldrych Zwingli . Zwingli-Verlag, Zurich 1969.

- Berndt Hamm: Zwingli's Reformation of Freedom . Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1988, ISBN 3-7887-1276-7 .

- Boris Hogenmüller: ZWINGLI, Ulrich (also Huldreych, Huldrych or Huldreich), Zurich reformer. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 33, Bautz, Nordhausen 2012, ISBN 978-3-88309-690-2 , Sp. 1585-1600.

- Walther Köhler : Huldrych Zwingli . Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1943, 2nd edition 1954, reprint 1983.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Locher : The Zwinglische Reformation in the context of the European church history . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen and Zurich 1979, ISBN 3-525-55363-3 .

- Gottfried Wilhelm Locher: Huldrych Zwingli . In: Martin Greschat (ed.): Figures of church history, Volume 5: The Reformation I . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne / Mainz 2 1994; Pp. 187-216; ISBN 3-17-013695-X (complete edition).

- Christian Moser: Huldrych Zwingli. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Oswald Myconius : Narrationem de vita et obitu Zwinglii . Zurich 1532. Newly published by Ernst Gerhard Rüsch: On the life and death of Huldrych Zwingli (German-Latin) . Fehr, St. Gallen 1979.

- Matthias Neugebauer: Ulrich Zwingli's ethics. Stations - Basics - Concretions. TVZ, Zurich 2017, ISBN 978-3-290-17892-5 .

- Peter Opitz : Ulrich Zwingli. Prophet, heretic, pioneer of Protestantism. TVZ, Zurich 2015, ISBN 978-3-290-17828-4 .

- Martin Sallmann : Zwinglianism. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Hans Schneider : Zwingli's beginnings as a priest. In: Ulrich Gäbler, Martin Sallmann : Swiss Church History, newly reflected. Festschrift for Rudolf Dellsperger on his 65th birthday (= Basel and Bern studies on historical and systematic theology. Volume 73, ISSN 0171-6840 ). Peter Lang, Bern 2011, ISBN 978-3-0343-0430-6 , pp. 37-62.

- Christoph Sigrist : Anna Reinhart and Ulrich Zwingli. From the daughter of an innkeeper to the reformer's wife. Biography of a novel as a diary , Herder Verlag GmbH, 2017, ISBN 978-3-451-06987-1 .

- Rudolf Staehelin : Huldreich Zwingli and his Reformation work. For Zwingli's four-century birthday (= writings of the Association for Reformation History. 3). Hall 1883 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- Rudolf Staehelin: Huldreich Zwingli. His life and work are presented according to the sources . B. Schwabe, Basel 1895 ( archive.org [ DjVu ]).

- James M. Stayer: Zwingli, Huldrych (Ulrich). In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- Alfred Vögeli: Huldrych Zwingli and the Thurgau. In: Thurgauer Jahrbuch , Vol. 45, 1970, pp. 72-102. ( e-periodica.ch )

Reception in film and theater

- Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer : Ulrich Zwingli's death , historical tragedy in five acts, Zurich 1837.

- Gottfried Keller : Ursula . - Novella about the Reformation in and around Zurich as part of the Zurich Novellas . In the 1978 film adaptation of Keller's Ursula by Egon Günther , Zwingli was played by Matthias Habich .

- Huldrych Zwingli - The Reformer. Feature film, 1983, 54 min., Commissioned by the Church Council of the Canton of Zurich ; Production: Condor Films, Director: Wilfried Bolliger ( entire film on YouTube ).

- Andreas Boller , Friedo Dürr , Hans Strub (Director): Helm off! A game about the Huldrych Zwingli syn helmet. - The story of Zwingli's helmet is told in three timelines: timeless, historical and today. Helfereitheater, Zurich 2014.

- Zwingli's legacy . Feature film, 2018, 55 min., Production: Eutychus Production, director: Alex Fröhlich.

- Zwingli . Feature film, 2019, 124 min., Production: C-Films AG, director: Stefan Haupt .

Web links

- Zwingli page of the church information service of the Ev.-ref. Regional Church of the Canton of Zurich

- Huldrych Zwingli works: digital texts

- Huldrych Zwingli letters: digital texts

- Digital copies of Ulrich Zwingli's writings on E-rara.ch

- Publications by and about Huldrych Zwingli in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Huldrych Zwingli in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Huldrych Zwingli in the German Digital Library

- Publications from and about Huldrych Zwingli im VD 17 .

- Texts by Zwingli in the voice of faith

- Zwingli . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 16, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 1018.

- Hans Ulrich Bächtold: Huldrych Zwingli. In: Huldrych Zwingli, writings. Zwingliverein, Zurich, 1995, pp. 495–497 .

- Andreas Main: 500 years of Zwingli in Zurich - “Setting the course in world history”: Interview with Dorothea Wendebourg. In: Deutschlandfunk broadcast “Day by Day”. August 8, 2019 (also as mp3 audio , 20.6 MB, 22:35 minutes).

Individual evidence

- ↑ The signature was found in Zwingli's letter to Konrad Sam of June 20, 1529.

- ^ Heinrich Bruppacher: The family name Zwingli. In: Zwingliana 2 (1905), pp. 33-36.

- ↑ a b Ulrich Gäbler: Huldrych Zwingli. An introduction to his life and work . Beck, Munich 1983, 3rd edition Zurich 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Hans Kläui , Alfred Egli and Viktor Schobinger ( Zurich family names. Origin, distribution and meaning of the names of long-established Zurich families. Zürcher Kantonalbank, Zurich 1994, p. 185) assume the same etymon by using "Zwingli" as a nickname for one, who presses his fellow men, interpret. This meaning is also in Heinrich Bruppacher: The family name Zwingli. Considered in: Zwingliana 2 (1905), pp. 33–36, but rejected for linguistic reasons.

- ↑ Gäbler, p. 30.

- ^ Erwin Liebert: Zwingli - Student in Vienna. From: Erika Fuchs, Imre Gyenge, Peter Karner, Erwin Liebert, Balázs Németh: Ulrich Zwingli Reformer. The current series No. 27, pp. 18–19, museum.evang.at [1]

- ↑ Hans Heinrich Göldi. In: Bernese sexes. Retrieved December 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Hans Schneider: Zwingli's beginnings as a priest . In: Ulrich Gäbler , Martin Sallmann : Swiss Church History, newly reflected: Festschrift for Rudolf Dellsperger on his 65th birthday (= Basel and Bern studies on historical and systematic theology, 73). ISSN 0171-6840 . Peter Lang, Bern 2011, ISBN 978-3-0343-0430-6 , pp. 37-62.

- ↑ a b Gäbler, p. 35.

- ↑ Tobias Straumann : The most profitable defeat in Swiss history. In: Tages-Anzeiger . March 17, 2014, accessed December 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Rea Rother: Pest in Zurich. In: Zwingli-Lexikon from A – Z. Reformed Church of the Canton of Zurich, accessed December 27, 2017 .

- ^ Arnd Brummer : Ulrich Zwingli and the Reformation in Switzerland: "The free choice of dishes". In: evangelisch.de . October 22, 2019, accessed December 19, 2019 .

- ↑ On the whole cf. Matthias Reuter: Eating sausages - breaking the fast in 1522. In: Zwingli-Lexikon from A – Z. Reformed Church in the Canton of Zurich, accessed December 20, 2019 .

- ^ Sigmund Widmer : 1484 - Zwingli - 1984. Special edition of the 1983 edition. Theological Verlag, Zurich 1984, p. 71.

- ↑ Jörg Lauster : The enchantment of the world. A cultural history of Christianity. CH Beck, Munich 2014, p. 316.

- ↑ Angelo Garovi: Enigmatic Relationship to Music. In: Kathbern.ch, Internet portal of the Roman Catholic Church in the canton of Bern. June 16, 2016, accessed November 11, 2018 .

- ^ Ulrich Gäbler: Huldrych Zwingli. CH Beck, Munich, 1983, ISBN 3-406-09593-3 , p. 117.

- ↑ a b Ulrich Gäbler: Huldrych Zwingli. CH Beck, Munich, 1983, ISBN 3-406-09593-3 , p. 141.

- ↑ Andreas Main: 500 years of Zwingli in Zurich - “Setting the course in world history”: Interview with Dorothea Wendebourg. In: Deutschlandfunk broadcast “Day by Day”. August 8, 2019, accessed on August 9, 2019 (also as mp3 audio , 20.6 MB, 22:35 minutes).

- ↑ Stefan Hess , Tomas Lochman (ed.): Classical beauty and patriotic heroism. The Basel sculptor Ferdinand Schlöth (1818–1891). Basel 2004; Pp. 71, 73, 212 f.

- ↑ Zurich, who still knows their way around. Orell Füssli-Verlag, 1971.

- ^ Sigmund Widmer: 1484 - Zwingli - 1984. Special edition of the 1983 edition. Theological Publishing House, Zurich 1984, p. 21.

- ↑ Hannes Reimann: Huldrych Zwingli, the musician , 1960, contained in: Music and the Renaissance: Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation , edited by Philippe Vendrix

- ↑ Jürg Freudiger: A 500 year old appeal. In: The magnifying glass. The stamp magazine. Issue 2, 2019, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ^ Postage stamp: Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) reformer (Switzerland). In: colnect.com. Retrieved May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Joachim Schäfer: Huldrych Zwingli. In: Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints. November 4, 2018, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ https://books.google.de/books?id=Yp1kC8Pmd1QC&printsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Feature films Huldrych Zwingli. Evangelical Reformed Church of the Canton of Zurich, accessed on November 15, 2018 .

- ↑ 2014 helmet off! - a game and Huldrych Zwingli syn helmet. Helfereitheater, September 12, 2017, accessed on November 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Short film Zwingli's legacy - Teaser Online. In: zwinglifilm.ch. Retrieved November 15, 2018 .

-

↑ Zwingli Film - IN THE CINEMA from January 2019! Ascot Elite Entertainment, accessed November 15, 2018 . Zwingli. kitag.com, accessed November 15, 2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zwingli, Huldrych |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zwingli, Huldreych; Zwingli, Huldreich; Zwingli, Ulrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss theologian, founder of the Reformed Church in Zurich |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 1, 1484 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wildhaus |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 11, 1531 |

| Place of death | Kappel am Albis |

![Signature of Huldrych Zwingli [1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/44/Signature_of_Huldrych_Zwingli.svg/220px-Signature_of_Huldrych_Zwingli.svg.png)