harpsichord

| harpsichord | |

|---|---|

| French harpsichord from Donzelague, Lyon 1716 | |

| classification |

Chordophone keyboard instrument |

| Musician | |

| Category: Harpsichordist , List of Harpsichordists | |

The harpsichord [ ˈtʃɛmbalo ] (Italian: clavicembalo , French: clavecin , Dutch: clavecimbel , English: harpsichord , Spanish: clavecín , Portuguese: cravo ) is a keyboard instrument that had its heyday in the 15th to 18th centuries would have. Its range is smaller than that of the modern piano , but it can often be expanded with 4-foot registers, sometimes 16 and 2-foot registers. The harpsichord stands out from the piano with its bright, overtone-rich sound. In contrast to the piano, the strings are not struck with hammers , but plucked with picks - so-called quills . Because the keystroke has no significant influence on the volume of the sound, the articulatory and agogic design of the game is all the more important.

Etymology and names

Harpsichord is originally a short form for harpsichord , with Italian clavicembalo on medieval Latin clavicymbalum back (medium latin clavis "" button cymbalum " cymbal "). A subsidiary form in Italian was gravicembalo .

The historical German name Clavicimbel (modern spelling: Klavizimbel ) has been out of use since the second half of the 20th century. A systematic name that encompasses all the different types of harpsichords would be plucked piano , although the terms keel piano and keel instrument are more common. Harpsichords in the common wing-shaped design are also called keel wings . In historical sources the harpsichord is commonly known in its heyday to about 1800 mostly as a wing called while still quite new fortepiano in the 18th century as a fortepiano or pianoforte was known. Only after the harpsichord was completely out of fashion, at the beginning of the 19th century, the name wing was transferred to the wing-shaped pianoforte , as is still common today.

The usual plural form in technical language is harpsichord . The modern Duden lists both harpsichords and harpsichords as plural forms (as of 2019).

Sound generation

The harpsichord can be described as a " plucked instrument with a keyboard ". The sound is generated via keys and is based on the plucking of strings using thorn-shaped picks , so-called "quills" (formerly bird quills, hence the name, or leather picks, nowadays mostly industrially manufactured quills made of the plastic Delrin ). The keels are in movable "tongues"; these are mounted in "jumpers" or "docks"; the jumpers in turn stand up on the rear key ends and are guided in a "rake". When the key is struck, the jumper moves upwards and the keel plucks the string. When the key is released, the jumper falls back; thanks to the movable tongue, the keel scrapes past the string; a felt flag, which is also attached to the jumper, dampens the string. The keels are wearing parts and can be replaced and voiced by the player himself .

The strings are almost always made of metal, usually brass or iron . Brass sounds warmer, darker and a little louder; Iron is a bit more silvery, lighter and finer. Many harpsichords use brass for the bass range and iron for the middle and high registers. But there are also harpsichords that are completely covered with brass strings, especially instruments of Italian design. Only the rare lute harpsichords were covered with gut strings.

All good harpsichords have a certain touch dynamic - the differences in volume that can be measured between individual tones are very small. Therefore, other measures for shaping the sound play an important role. Like an organ , a harpsichord can have registers , i.e. H. have different sets of strings that can be switched off and on. This allows the volume and timbre to be changed. Since the registration can only be used over a large area, the musical performance is essentially designed via the articulation (also leaving harmony tones in chord breaks, the so-called "legatissimo") and via the agogic .

Most harpsichords have a lute pull , switchable damping that imitates the plucking of a lute . Other ways of influencing the sound were tried out with neighboured harpsichords. For example, English harpsichords from the period after 1760 (among others by Kirkman and Shudi ) had what is known as a cover sill that can be opened or closed using a pedal. The dynamic effect can only be compared to that of an organ swell to a limited extent.

Some harpsichords of the 20th century, mostly in a detent design, that is, with a body that is open at the bottom, sometimes allow dynamic changes within a register by changing the position of the keels to the strings. So the strings are torn stronger or weaker. However, this facility has not proven its worth.

Main designs

The large shape of the harpsichord and at the same time the narrower meaning of the word harpsichord is the "keel wing". The two important smaller forms are called " virginal " and " spinet ".

Keel wing

With the actual harpsichord in the shape of a wing ("keel wing"), the strings run in the extension of the keys; the keyboard with the action is at one end of the strings. Occasionally, there are also pedal keyboards used historically and in modern instruments . The clavicytherium has an upright wing shape .

One-manual harpsichords

One-manual harpsichords - instruments with a single keyboard - sometimes have two different strings ( registers ). These usually sound at the same pitch (8 ') with different timbres. (The normal pitch is called "eight feet" (8 '), based on the pipe lengths of pitch-analogue organ registers.) The different sound is created by different touch points on the keels: The closer the touch point to the middle of the string, the fuller and rounder the tone ; the second register with the marking point closer to the key sounds a bit lighter and more silvery. The two registers can be played individually or simultaneously, ie "coupled". These types of instruments were particularly common in Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries, but they were also found in other countries.

Early Italian harpsichords in the 16th and early 17th centuries often originally had two registers at different pitches; and also the harpsichords of the famous Ruckers- Couchet dynasty in Antwerp, which was active from around 1580 to 1655: In addition to a string cover in the normal 8 'position, there was a second, which was shorter and sounded an octave higher. This register is called "four feet" (4 '). The historical fact of this 8'-4 'disposition was not known for a long time, because many original instruments were e.g. In some cases it was rebuilt in the 17th century and the four-foot register was exchanged for a second eight-foot register, or a third string cover was even installed (often in the 18th century for Ruckers harpsichords).

Two manual harpsichords

Harpsichords with two manuals usually have three strings, two different sounding 8 'and one 4' registers. Two-manual harpsichords with this 8'-8'-4 'disposition were in use at least from 1648 (see illustration on the right), apparently first in France , later also in England , Germany and the southern Netherlands (today's Belgium ). Usually each of the two manuals had an 8 'register; the 4 'register could only be played by one manual, which then had the old Ruckers disposition 8'-4'. In addition there was usually a lute.

The registers could only be operated by hand; It was not until around 1760 that arrangements were made that could be used to re-register during the game: in France using knee levers ( genouillères ), in England using pedals ( machine-stop ). Many of these instruments had a so-called sliding coupler , with which one could play the two “eight-footed” or all three registers at the same time by moving a manual. This also enables forte piano or echo effects between the manuals. In England, Germany and Flanders in particular, so-called dogleg jumpers were used instead of the sliding belt : An 8 'register had stepped jumpers that could be operated from both manuals.

Registers and moves

Few harpsichords have been built with a fourth register in a sixteen foot position (16 '), almost exclusively by harpsichord builders in Hamburg, Saxony and Thuringia. Such instruments are also significantly longer than normal harpsichords because of the 16 'strings. A 2 'register was almost even rarer.

So-called nasal registers , sometimes also called cornet pull or nasat register , were much more common . These have a bright, somewhat pointed, nasal sound that is reminiscent of the tongue registers (krummhorn, trumpet, etc.) or the cornet or nasat registers of an organ. They were built especially in southern German-Austrian instruments of the early 17th century, also in some instruments by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass , and in late Flemish harpsichords by Dulcken and by Kirkman or Shudi ( Tschudi ) in England, where they were called lute-stop and almost occurred in every instrument.

The English name lute-stop for the Nasalregister should not be confused with the lute in Flemish, French and German harpsichords, which has a very different sound and England harp-stop (= "Harfenzug") was called (nowadays: buff-stop ) . The lute stop is not a register (string reference), but a switchable damper that makes the sound of a group of strings or an entire register softer and louder-like.

In France, from the 1760s onwards, an additional 8 'register was sometimes built in, which was filled with picks made of soft buffalo leather instead of quills . This was called peau de buffle and produced a particularly soft, supple tone. It was even claimed that light dynamic shading was possible with it.

Leather picks were also sometimes used in England, but they were made of a somewhat harder material than in France. In some instruments registers with metal picks have been found, mostly made of brass, e.g. B. in a South German claviciterium from around 1620 ( Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg ) and in a French spinet by Pierre Kettenhoven, Lyon 1777 ( Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe , Hamburg). The oldest surviving English harpsichord by Lodewijk Theewes from 1579 ( Victoria and Albert Museum , London) probably also had at least one metal register.

Virginal

With the virginal the strings run across the keys. The housing shape is either polygonal or rectangular with the keyboard on the long side where the bass strings are. The key levers (under the soundboard) get longer and longer from left to right, or from bass to treble. Virginals usually only have one register. The sound is relatively full, round and tends to be a bit bell-shaped. Most virginals have their keyboard on the left or in the middle. In Flanders virginals were also built with the keyboard to the right; these are called muselars and have a dark, bell-shaped, flute sound.

Both historically and today, virginals were often referred to differently depending on the country and epoch - mostly as a spinet. In Italy they were called spinetta or arpicordo (16th – 17th centuries), in France épinette (historically and today); Virginals with the keyboard on the left or in the middle were also called spinettes in Flanders and Holland (16th – 17th centuries).

spinet

In the actual spinet - also called transverse spinet - the keyboard is located at one end of the strings, like the keel wing, but these run at an angle to the direction of the keys and are usually shorter than the keel wing. This results in a space-saving, mostly more or less triangular, inclined shape of the instrument. The spinet is a house instrument, tonally similar to the keel wing, but almost always with only one manual and one register.

The transverse spinet was probably invented by Girolamo Zenti , from whom the earliest of these instruments has survived (1631, Brussels, Musée Instrumental); in France this instrument was called espinette à l'italienne ("spinet in Italian manner"). It was particularly popular in England in the late 17th and 18th centuries and is called bentside-spinet in English-speaking countries . 14 spinets have also survived from Johann Heinrich Silbermann (1727–1799).

Special designs

Octave harpsichords, quarto harpsichords, transposing harpsichords etc. a.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, harpsichords were not only built in the usual 8-foot position, but also in other pitches. 4-foot and quart instruments were relatively common. On a 4-foot instrument - called an octave harpsichord, octave spinet , ottavino or ottavina - all notes sound an octave higher, on quart instruments a fourth higher than on 8-foot instruments. The actually intended pitch cannot always be determined because it depends not only on the length of the instrument, but also on factors such as the thickness of the original strings (the thicker the string, the deeper the tone), the material of the original strings (a Iron strings can be stretched more than a brass string and then sound higher) or the relevant pitch .

Examples of instruments in a 4-foot position can be found in the Musée de la Musique in Paris (octave harpsichord by Dominicus Pisaurensis, Venice 1543, see illustration) or in the Hamburg Museum of Art and Crafts (octave spinet by an unknown harpsichord maker, Italy around 1650). The oldest surviving example of a harpsichord built north of the Alps, also the first known instrument with a transposition device, is so small that it must have had a higher pitch (harpsichord by Hans Müller, Leipzig 1537, exhibited in the Roman Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali) .

The famous Ruckers family in Antwerp built keel instruments (harpsichords and virginals) in a wide variety of sizes and tones. These instruments were named after their length with Flemish measures: there were keel instruments in 6 voet , 5 voet , 4 voet , 3 voet , and 2 voet 4 duimen . Between approx. 1570 and 1650 they also built two-manual harpsichords, the manuals of which were tuned a fourth apart: the upper manual sounded a fourth higher than the lower; the two manuals could not be used at the same time. Such instruments are called transposing harpsichords using a modern term , because it is believed that the purpose of these harpsichords was precisely to facilitate transposing from one key to the other. All of the Ruckers' two-manual harpsichords were exclusively transposing harpsichords, but only two harpsichords have survived in their original condition: Both are by Ioannes Ruckers and date from 1637 (Rome, Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali) and from 1638 (Edinburgh, Russel Collection, No. 6). All other former Ruckers transposing harpsichords were changed from the end of the 17th century and converted into the "normal" two-manual harpsichords that are still known today (see above).

Instruments with "broken" upper keys

From around 1550, there were various theories and experiments, especially in Italy, to revive the ancient music of the Greeks, or at least to bring the (then) modern music closer to the ancient. Since Greek music is said to have had more than the regular semitones of the medieval church tones , there was no enharmonic mix-up in the commonly used (1/4 decimal point) mean tone tuning for keyboard instruments , only the semitones c sharp, e flat , f sharp, g sharp and b flat, keyboard instruments with more than the usual 12 keys per octave were invented in this context.

For this purpose, some of the upper keys for the semitones were "broken", that is, one could e.g. B. play the note G sharp, and on the back part of the same key the note As, which is a separate note in the mid-tone tuning.

The simplest and most practical of such instruments (including organs) only added the most important and most widely used semitones, i.e. the tones A flat (on the G sharp keys) and D flat (on the E flat keys). More luxurious variants also had broken keys for the semitones: D flat (on C sharp), G flat (on F sharp), and possibly A sharp (on B flat). Such harpsichords (and virginals) were made relatively frequently in Italy until about the middle of the 17th century. But they were probably rebuilt a lot later.

There were even 19-step instruments that, in addition to the aforementioned broken upper keys, had small keys for the ice (between E and F) and for the his (between B and C). This type of keel instrument was called cimbalo cromatico . Their invention goes back to ideas of the Italian composer and theorist Gioseffo Zarlino , who mentioned a tuning with 19 notes per octave in his work Le istituzioni harmoniche as early as 1558 ; Francisco de Salinas is also said to have played a 19-step instrument constructed according to his plans, and Michael Praetorius mentions such an instrument in 1619 in Syntagma musicum .

Music for cimbalo cromatico was written by the Neapolitan composers Giovanni Maria Trabaci and Ascanio Mayone ; also Gian Pietro Del Buono , Adriano Banchieri , and the Englishman John Bull . The instrument was also used by composers such as Guillaume Costeley and Charles Luython , and most likely by Carlo Gesualdo and other Italian madrigalists around 1600. Johann Jakob Froberger may also have composed some pieces for an instrument with broken upper keys, at least for the tones A-flat / G sharp and D flat / it, e.g. B. the Capriccio FbWV 516 (1656), and the famous Lamentation faite sur la mort tres douloureuse de sa majesté Impériale Ferdinand le troisieme… (1657).

The most extreme case of a chromatic keyboard instrument was the so-called archicembalo (or arcicembalo ): an instrument with 36 keys in the octave, which was invented by the Italian music theorist Nicola Vicentino (in: L 'antica musica ridotta alle moderna prattica. Rome 1555). The Venetian harpsichord maker Vito de Trasuntino built a Clavemusicum omnitonum with 31 keys per octave on behalf of Count Camillo Gonzaga in 1606 - the only such instrument that still exists today (today in the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica in Bologna ).

Harpsichords and virals with broken upper keys were only built until around 1650 because, on the one hand, the fashion for chromatic and enharmonic experiments waned, and on the other hand, in the second half of the 17th century, practicable tunings emerged (e.g. from Werckmeister ) with which enharmonic confusion was possible and with the help of which one could play more unusual keys of the slowly developing major-minor system even on normal, simple keyboards.

Broken upper keys were also used on instruments with the short bass octave , especially the one on C / E for the notes F sharp and G sharp.

Travel embali

The French Jean Marius invented a three-part, collapsible traveling harpsichord, which he called clavecin brisé ("broken harpsichord"), and received a 20-year royal patent from the Académie des Sciences for it on September 18, 1700 . These practical instruments have a length of approx. 130 cm and a width of approx. 75 cm, and a circumference of GG – e 3 with a short bass octave . Some instruments have been preserved in various museums; a copy in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum Berlin belonged to Sophie Charlotte , Queen of Prussia and grandmother of Frederick the Great. The Italian harpsichord maker Carlo Grimaldi (verifiable: 1697–1703) also left an undated traveling harpsichord.

Claviorgana and other combination instruments

Sometimes harpsichords were combined with other instruments. The best-known example of this was the claviorganum, a combination of organ positive and harpsichord that was apparently particularly popular in the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. There is archival evidence that the Spanish Infante Don Juan owned two claviórgana as early as 1480 , the same applies to Philip II of Spain (according to the inventory from 1598). The earliest (fragmentary) preserved English harpsichord by Lodewijk Theewes (1579, Victoria and Albert Museum, London) is part of a claviorganum.

Some instruments also had a shelf , apparently particularly in the southern German-Austrian region (e.g. Claviorganum by Josua Pockh 1591, Salzburg Cathedral Museum ).

In the late 18th century there were instruments that were a combination of harpsichord and fortepiano ; or a combination of harpsichord and tangent piano in both cases, the respective registers can be played not only individually but also together.

In the 17th century the Ruckers built some large box-shaped instruments that combine a harpsichord with a virginal (see below); this is simply firmly integrated in front of the (actual) hollow side of the harpsichord. So there are two keyboards that cannot be played by the same person at the same time: the harpsichord keyboard on the narrow side and the virginal keyboard on the long side.

Clavicytherium

The clavicytherium is a harpsichord with the body upright. The strings are perpendicular to the keys. It is a space-saving variant of the harpsichord, but it requires sophisticated mechanics for the jumpers. The clavicytherium had been known since at least the 1460s. But as early as 1388 John I of Aragon mentions in a letter to Philip the Bold of Burgundy an instrument that "resembles an organ, but that sounds with strings" ( semblant dorguens que sona ab cordes ). If this instrument were to have been a clavicytherium, that would mean that the clavicytherium is perhaps older than the harpsichord.

Also the oldest surviving keel instrument is a small anonymous clavicytherium from around 1470, which probably comes from Ulm and is now in the Royal College of Music in London. Clavicytheria were apparently rather rare, but were built until the 18th century, later also with fortepiano mechanics.

Harpsichord making from the beginning to the 18th century

Beginnings

The first known harpsichord maker and possibly its inventor was the mathematician, astrologer, physician and organist Hermann Poll from Vienna. The Italian nobleman Lodovico Lambertacci describes Poll in a letter addressed in Padua in 1397 as "a very witty man and inventor of an instrument which he calls the clavicembalum ." The next mention of the harpsichord is in 1404 in Eberhart Cersne's Minne Rule . The clavisimbalum was first described in detail in 1440 by Henri Arnaut de Zwolle , as was the clavicordium and an instrument with hammer action called dulce melos (sweet melody). One of the first images is from 1425 and was originally at Minden Cathedral : an angel with a small clavicembalum on his lap. These early forms of the harpsichord were relatively small instruments, as numerous other illustrations before 1500 show. This tradition may explain the relatively widespread use of octave and quarto harpsichords in the 16th and early 17th centuries (e.g. the instruments by Hans Müller in 1537, or by Pisaurensis in 1543 and 1546, see above).

The harpsichord and its relatives virginal, spinet, claviorganum, etc. a. established themselves in the Renaissance (15th to 16th centuries), with different traditions and designs in various European countries.

Italy

In Italy, harpsichords and other keel instruments had been built since 1419, and it was the largest center of harpsichord making, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries. Most of the farmers worked in the large culturally, economically and politically important cities of Venice , Milan , Bologna , Rome , Naples , but also in smaller places. As far as we know today, Italian keel instruments have also been exported to other countries throughout Europe, and around 50 harpsichords and around 100 virginals from the 16th century alone are still preserved today. The earliest surviving harpsichords are also Italian: an instrument by Vincentius from 1515/1516 owned by Pope Leo X (today in the Accademia Chigiana , Siena), and a harpsichord by Hieronymus Bononiensis from 1521 (today in the Victoria and Albert Museum , London ).

Until the 18th century, Italian harpsichords normally had only one manual, mostly with light lower keys (e.g. boxwood ) and dark upper keys (e.g. ebony ); there are exceptions, however, and some instruments have ornate keys with inlays. The instruments were often made of valuable and durable hard woods such as cypress or cedar , and their walls were so delicate and thin that they were placed in a larger case for protection, which was often richly decorated (see right picture by Pietro Faby from 1677 ); This principle of a delicate instrument in an outer box with a lid is called inner-outer in English . As early as the end of the 16th century, thick-walled instruments were sometimes made of softwood, which no longer needed their own case, but were directly connected to this and the lid; These are called false inner-outer with the English technical term , because the harpsichord makers optically often simulated an instrument in a protective case.

The typical Italian harpsichord in the 16th century had an 8 'and a 4' register, but there were also (early) instruments with a single 8 ', and from the second half of the 16th century, harpsichords with the one that is typical today Italian prestigious disposition of two 8 'registers. Many instruments before 1600 had a relatively large range up to f '' ', but with a short octave in the bass, i.e. a range from C / E - f' ''; sometimes also C / E to c '' '.

Many Italian harpsichords have been rebuilt and modernized over time, sometimes several times. This is why most of the instruments that have survived today have the 8'-8 'disposition, which was established around 1630. The range was also often changed and tended to drop by a fourth, i.e. to G to c '' 'or to d' '' - again mostly with a short G octave, or at least with a few missing semitones in the bass.

Italy was also the home of the so-called harpsichord cromatico , and by the end of the 16th century to around 1650, many Italian harpsichords had broken upper keys (see above). Harpsichords with three registers, such as 8'-8'-4 '(e.g. from Giusti 1679 and 1681) or 8'8'8' (e.g. from Mondini 1701), were also less common.

In the 18th century, many fine harpsichords were still being built in Italy, even if sticking to a single manual seemed a bit old-fashioned or limited from the point of view of other European countries. There were still harpsichords of the real inner-outer type alongside those of the false inner-outer type. Instruments with a short octave on C / E were also still being built, on the other hand, the range of instruments increased to 5 octaves from around 1740 (mostly FF - f '' ').

The sound of Italian instruments was a bit “crisp”, but not necessarily as short, “percussive” and uniform as is sometimes claimed. Tonal differences arise a. by different string material, different circumference or by different woods for the soundboard (e.g. cypress or spruce).

Flanders

A second major center of harpsichord construction developed in Flanders , especially in the trading metropolis of Antwerp , from the second half of the 16th century . This is all the more remarkable as very little harpsichord music is known from this region. The first Flemish keel instruments come from Ioes Karest (approx. 1500 - approx. 1560), actually a German from Cologne, they are virginals from 1548 (Brussels, Musée Instrumentale) and from 1550 (Rome, Museo Naz. Degli Strumenti musicali ). The first surviving real harpsichord from Flanders dates from 1584 (Sudbury, Maine, private property), and was built by Hans Moermans (active approx. 1570–1610). From around 1580 onwards, Hans Ruckers (around 1550–1598), the founder of the Ruckers dynasty, which died out around 1650 and was continued by another branch of the family, the Couchets, until around 1680.

The Flemish harpsichords, which have been preserved mainly from the Ruckers since 1584, have, compared to the Italian inner-outer instruments, relatively thick, stable walls made of softwood, with soundboards made of spruce or fir . Their body is significantly wider than that of Italian instruments. Harpsichords of the Ruckers type had a manual and their original disposition consisted of an 8 'and a 4' until around 1650. They had a short octave on C / E, and the range went up to c 3 . There were also instruments with two manuals at different pitches, which are now called "transposing harpsichords", so actually two instruments in one (see above); in these, the upper manual was "normal", the lower manual had an apparent range from C / E to f 3 , but sounded a fourth lower.

The Ruckers instruments also had a standard decoration, which consisted of marbling on the outside and prefabricated wallpaper that simulated inlays on the inside ; The inside of the lid was also "papered" and had a motto, such as B. Soli Deo Gloria (et Sanctum Nomen Eius) (= "Only in honor of God (and in his name)") or Sic Transit Gloria Mundi (= "Thus the glory of the world passes"). The soundboard was (in contrast to Italian instruments) painted with flowers, birds, butterflies and "vermin", and z. Sometimes also with small figures like angels or grotesque dwarf figures, so-called Callotti (after Jacques Callot ). There were also instruments with more valuable decorations, e.g. B. with a cover painting. The lower keys were (originally) white (made of bone), the upper keys were black.

From around 1650 onwards, the couchets also built harpsichords with other dispositions, e.g. B. 8'-8 'or with three registers.

The instruments of the Ruckers and Couchets were so much valued, especially in France and England, that their prices fell on e.g. T. astronomical heights rose. The instruments have also been changed and rebuilt (similar to Italian harpsichords) since the 17th century. T. drastically. The decor was also changed many times. Counterfeits were also built in Paris in the 18th century, e.g. Partly by famous harpsichord makers like Pascal Taskin .

The almost mystified Ruckers harpsichords also had an enormous influence on the harpsichord construction of the 18th century, especially in France and England, but also in Germany.

After the Ruckers-Couchet died out, the most famous South Dutch harpsichord makers in the middle of the 18th century were the Dulcken family in Antwerp and Albert Delin in Tournai. The pitch range of the instruments also increased in the 18th century, until it reached five full octaves around 1740-1750 . Delin's instruments are all single-manual with 8'-8 'lute. The Dulckens have one and two manual harpsichords. The two-manual harpsichords are very long (much longer than e.g. French ones) and they all have a nasal register, i.e. 3 × 8 ', 1 × 4' + lute.

"International Style"

In France, Germany and England one built until about the year 1700 and z. Some of the harpsichords are relatively thin-walled and have a fundamental tone, almost always made of a type of wood typical of the country of origin (e.g. walnut in France, oak and later walnut in Great Britain, etc.). These instruments were made almost as delicately as the Italian ones, they often had walls of medium thickness and usually did not need their own protective case like the instruments from Italy. Because of these characteristics, this group of harpsichords is called an “international style” of the 17th century, although the harpsichords that have survived from these countries also have their own features.

France

The center of French harpsichord making was in Paris. There were also manufacturing facilities in Lyon and Toulouse. The first mentions of real harpsichords (ie no virginals French épinettes ) can be found in the de la Barre inventory from 1600 and in Mersenne's Harmonie universelle from 1636. The harpsichord experienced a great heyday in the France of Louis XIV and his successors; therefore, to this day, and not only in France, it is often regarded as a typically French instrument.

The first surviving French harpsichord by Jean II Denis (1600–1672) dates from 1648. It is also the first surviving example with two manuals on the same pitch (in contrast to the so-called “transposing harpsichords” of the Ruckers) - a so-called “contrasting harpsichord” “With 8'-8'-4 'and lute. Apart from simpler single-manual harpsichords, this remained the typical standard equipment of a French harpsichord for the next 140 years.

Around 1700, an important turning point gradually took place: triggered by the influence of the Ruckers' instruments, the harpsichords were no longer made of walnut, but mainly of softwood, the body thickness became much thicker and the body wider. In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the range was mostly GG - c '' 'or d' '', very often with a short octave on GG / BH. This range increased in the 18th century, the short bass octave was gradually chromatised and around 1740 to 1750 it reached five full octaves , usually FF-f '' '. All these developments led to ever larger instruments, and the original, somewhat “crisp” tone of the harpsichords from the 16th and 17th centuries was slowly being lost.

In the late period from around 1760 until the revolution , a number of innovations were tried, e.g. B. quills made of soft buffalo leather ( peau de buffle) and also a “machine” to switch registers on and off while playing using toggle levers ( genouillères ).

In contrast to normal Italian and the original jerk harpsichords, French harpsichords always had black lower keys (made of ebony) and white upper keys, and the keys were relatively narrow. The soundboard was painted with flowers and possibly birds. The walnut instruments of the 17th century could be decorated with rich inlays made from other woods. Instruments that were intended for the palais of wealthy aristocrats were often ornately decorated like a fairy tale, depending on the style and epoch with paintings, chinoiseries and gilding.

Franco-Flemish instruments

From the late 17th century onwards, numerous harpsichords by the Ruckers and other Flemish or French builders of the 17th century were subjected to a so-called small (petit) or large (grand) ravalement - one speaks here of Franco-Flemish harpsichords.

In the case of a petit ravalement , the disposition was often changed from 8'-4 ', either to 8'-8' or to 8'-8'-4 '. The keyboard range has been extended by a few tones, e.g. B. from C / E - c '' 'to GG / HH - c' ''. For this purpose, the old keyboard was often exchanged for a new one; the keys were narrower than before to make more space for the new notes. With two-manual transposing harpsichords, the two manuals were brought to the same pitch and the upper manual "filled" with the missing notes.

A grand ravalement was performed to extend the range to five full octaves (usually FF-f '' '). Here it was no longer enough to make the keys narrower, but the entire body of the original instrument had to be widened and rebuilt, possibly also reinforced from the inside. Originally one-manual instruments were often converted into two-manual instruments (e.g. an II Couchet 1680 - Blanchet 1750 (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts)). In the most extreme case, one took (rectangular) soundboards from old Ruckers virginal and built a new "Ruckers harpsichord" around it (e.g. a Ioannes Ruckers 1632 - Jean-Claude Goujon 1757 (France, private property).

Such ravalements were carried out by many very good and well-known farmers, starting with Nicolas Blanchet (1660–1731), through Jean-Claude Goujon (active 1743–1758) to Pascal Taskin (1723–1793). However, these practices occasionally led to genuine forgeries of Ruckers harpsichords á grand ravalement , e.g. For example, Goujon signed a beautiful instrument decorated with gold chinoiserie on black lacquer with “Hans Ruckers 1590” (Paris, Musée de la Musique), which for a long time was thought to be a real Ruckers. It was only during a repair that Goujon's true signature from 1749 came to light; The instrument was also subjected to a ravalement by Joachim Swanen in 1784 . The same applies to a harpsichord, also spectacularly decorated with chinoiserie, in the Hamburg Museum of Art and Crafts (Beurmann Collection), which Taskin spent on an "Anderias Ruckers ... 1636", which he allegedly renewed in 1787 - in truth not a single chip is from Ruckers .

Germany

Only relatively few instruments from Germany have survived from the period before 1700, perhaps because of the devastating destruction of the Thirty Years' War . It is also said, however, that in Germany and Austria the harpsichord building was only an additional income for the organ builder .

The earliest surviving German harpsichord was made by Hans Müller in 1537 (today in the Museo degli Strumenti musicali , Rome). It is marked with the inscription: God's word remains ewick beistan the poor as the rich by Hans Muller cv Leipcik in 1537 . A characteristic of this instrument is the fact that it has two strings of the same pitch, but three registers, two of which pluck the same string, but at a different point. So there are three rows of jumpers, which also diverge in a fan shape towards the bass. This means that the sound quality of the three registers is clearly different, especially in the bass: the register that plucks the strings quite far back has a relatively dark, round, virginal-like sound, the middle one a relatively "normal" silvery harpsichord sound, and the foremost is a nasal register.

Although the next preserved harpsichord from Germany was not built until 1619 by the Stuttgart court builder Johann Maier (1576–1626), more than eighty years later (currently in Salzburg, Museum Carolino Augusteum), it has very similar characteristics that were apparently typically German . The same applies to a number of other instruments, including an anonymous harpsichord with five register colors and lute pull in Munich (Bavarian National Museum), another in Budapest ( Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum ), and an anonymous clavizytherium (approx. 1620) in the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg. The latter has 8'-8'-4 'strings and four different register colors, plus lutes.

In Germany different materials were used for the keys, there were instruments with light lower and dark upper keys and vice versa; some instruments also have tortoiseshell or mother-of-pearl key coverings .

At the time of Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Handel , harpsichords were being built in various German cities. One of the most important centers was Hamburg with preserved instruments from the Hass and Fleischer families and from Christian Zell . Other important harpsichord makers were Christian Vater in Hanover, Michael Mietke in Berlin, the Gräbner family in Dresden, and the Silbermanns in Freiberg and Strasbourg. The Harrass family worked in Großbreitenbach in Thuringia , one of which was preserved in the 20th century (for no reason) and proclaimed an alleged "Bach harpsichord".

The instruments preserved were much less standardized than in other countries, they come in a wide variety of sizes and shapes. An elegantly rounded rear wall that emerges directly and in one piece from the cavity wall was relatively common. Here is a short list:

- There are simple single-manual instruments with two 8 'registers, e.g. B. by Michael Mietke 1702–1704 (Berlin, Charlottenburg Palace) and 1710 (Hudiksvall Sweden); or by Christian Vater 1738 (Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg); or an anonymous from approx. 1715 (Eisenach, Bach House ).

- single-manual harpsichords with 8'-8'-4 'and lute, e.g. B. by Johann Christoph Fleischer 1710 (Berlin, State Institute for Music Research); by Carl Conrad Fleischer 1716 (Hamburg, Museum for Hamburg History) and 1720 (Barcelona, Museu de la Música); by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass 1732 (Oslo, Kunstindustriemuseet); or by Christian Zell in 1737 (Barcelona, Museu de la Música) and 1741 (Aurich, East Frisian Landscape).

- elegant French-oriented instruments with 2 manuals and 8'-8'-4 'lutes, e.g. B. von Mietke 1703–1713 (Berlin, Charlottenburg Palace); or by Christian Zell 1728 (Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe); or by the Gräbners (a total of four instruments in different collections);

- Luxurious instruments with two manuals and imaginative arrangements have been preserved from Hieronymus Albrecht Hass: a 3 × 8 ', 2 × 4' plus lute from 1721 (Göteborg, Göteborgs Museum), and a 3 × 8 ', 1x 4' plus lute from 1723 (Copenhagen, Musikhistorisk Museum). Both harpsichords have a nasal register.

- and finally a few very large harpsichords with 16 ': two by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass from 1734 (Brussels, Musée Instrumental), and a three-manual harpsichord from 1740 (France, private collection); and one by Johann Adolph Hass 1760 (New Haven, Yale Collection). The Harass harpsichord of "approx. 1700 “(Berlin, Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung) perhaps had an original 16 '- but it was changed several times, and the exact original disposition was often discussed.

England

The earliest surviving English harpsichord was built by Lodeweijk Theewes, who immigrated from the Netherlands in 1579 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London); it is part of a claviorganum (see above). This instrument is particularly important because only very few instruments have survived from the era of the English virginalists (approx. 1570–1630). The harpsichord part of the Theewes claviorganum is single-manual and has the disposition 8'-8'-4 '- it is the earliest preserved harpsichord with this disposition. At least one of its registers may have had metal keels, and the instrument apparently also had an arpichordum slide, as is usually found on Flemish Muselar virginals . The Theewes-Claviorganum also had a continuous chromatic range of C – c '' ', at a time when keyboard instruments with almost only a short bass octave were built on the European continent .

The next surviving instruments are from Hasard 1622 (Knole, National Trust) and from Jesses Cassus (Encinitas, California, private). All three instruments were z. Some of them were made of oak and had a nasal register, and that of Hasard, like that of Theewes, had three registers on one manual.

The only other English harpsichord (as far as we know today) from the 17th century dates back to Henry Purcell's epoch . It is a one-manual instrument by Charles Haward 1683 (England, private property) and, like French instruments, made of walnut, but also has a nasal register at an 8'-8 'disposition. The earliest two-manual harpsichord with an 8'-8'-4 'disposition is made of walnut, it comes from Tisseran 1700 (Oxford, Bates Collection) and has a size of GG / HH -d' ''. Similar instruments with typical international (or French) markings (including medium-thick walls) were built up to around 1725, e.g. B. from Hitchcock , Hancock, Smith, Barton and Slade. A five-octave range of GG – g '' 'sometimes appears relatively early - similar to the much more common English spinets - (W. Smith 1720 (Oxford, Bate Collection) and Th. Hitchcock 1725 (London, Victoria and Albert Museum)).

From around 1720 the English harpsichords came under a certain Ruckers influence. Above all, the body became wider and the walls thicker. The first surviving instrument of this type is from the Dutch émigré Hermann Tabel from around 1721 (Warwick, County Museum). The two most important harpsichord makers of the 18th century were his students: Burckhardt Shudi (originally Tschudi; 1702–1773) and the Alsatian Jacob Kirkman (originally Kirchmann; 1710–1792) from Switzerland . Almost 200 large harpsichords have survived from them and their successors, which are basically similar to those of Tabel. They built five different types of instruments: one-manual harpsichords with 8'-8 '; single-manual with 8'-8'-4 '; the same with the nasal register ( lute-stop ); two-manual harpsichords with 8'-8'-4 '; and the same with nasal registers. The lower keys of 18th century English harpsichords are usually white and the upper keys are black.

The first preserved harpsichord from Shudi from 1729 (Tokyo, Ueno Gakuen College) was a gift from Georg Friedrich Handel to his favorite singer Anna Maria Strada del Pò . Shudi later also counted Joseph Haydn , Friedrich the Great and Maria Theresa of Austria among his customers .

English harpsichords of the 18th century look relatively sober, simple, bourgeois and functional compared to the often imaginatively decorated, aristocratic creations of other countries, but are veneered with fine woods, and some have valuable inlays in the keyboard area. The somewhat profane impression is also created by the angular and purely practical frames in contrast to richly carved baroque frames or elegantly curved rococo legs in other countries. The sound of the Kirkman and Shudi harpsichords is generally thought to be full and imposing. From around 1760 they often had a "machine" ( machine stop ), ie pedals with which registers could be switched on and off during the game, and Venetian swells were also built, a kind of blind that opened slowly or closed, for crescendo and decrescendo effects. The nine-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was allowed to “inaugurate” a Shudi harpsichord with machine-stop during his trip to England in 1765 , before it was sent to Frederick the Great in Prussia.

In 1793 the last known harpsichord was built by Broadwood , the successors of Shudi; Kirkman's last known harpsichord is signed 1800.

Other countries

In addition to the countries mentioned, harpsichords were also built elsewhere, but either in relatively small quantities or only a few have survived. Some countries were heavily influenced by the tradition of another country, e.g. B. the northern Netherlands from the Flemish harpsichord construction, Scandinavian countries in the 18th century from German and especially Hamburg farmers; The few instruments from Switzerland are also influenced by German. Only two late harpsichords have survived from North America , one of them in the English tradition.

Important own traditions and musical centers were in Austria and in Spain and Portugal . Austrian harpsichords were apparently mainly built in Vienna , they were heavily influenced by Italian instruments; and they often had a complicated short octave shape , which is required in some works by Alessandro Poglietti and Joseph Haydn.

Very early on, Spain produced a great deal of important music for harpsichord and other keyboard instruments. There is also documentary evidence of harpsichord makers as early as the 15th and 16th centuries, and from Domenico Scarlatti's time at the Spanish court. But for a long time no Spanish instruments were known. That has changed in the last few decades. In the meantime, some harpsichords are being discussed as originally Spanish, but they are not yet all or generally recognized as such. Some of them also have German features and make a very eclectic impression in general .

Some instruments from the second half of the 18th century are known from Portugal, especially from the Antunes family; they are similar to Italian harpsichords, but also use exotic woods, possibly from Brazil . A harpsichord by Joaquim José Antunes in 1758 (Lisbon, Museu da música) has been used more often for recordings of Portuguese music.

Harpsichord making since the 19th century

Reawakening interest

After a phase of insignificance, the Paris World's Fair in 1889 was an event that ushered in a certain rediscovery of the harpsichord: the French piano makers Tomasini, Érard and Pleyel , surrounded by exotic objects from Africa or Asia and framed by performances by a Javanese gamelan orchestra, each a harpsichord. The three instruments were freely based on a Taskin instrument from 1769.

There were also personalities who made a dishonest profit from the renewed interest in old Kiel instruments, the best known being the instrument dealer and forger Leopoldo Franciolini (1844–1920). He not only refurbished and repaired old instruments, but also wrote the names of famous farmers or freely invented, “sounding” names on anonymous harpsichords and virginals; He made instruments of the 18th century "older" by 200 years in order to increase their value. He changed some instruments heavily and in an unhistorical way, e.g. B. built two- and three-manual keyboards into Italian harpsichords, thereby deceiving not only wealthy private collectors, but also museums all over the world.

New snap harpsichord from the 20th century

The actual rediscovery of the harpsichord in the early 20th century is linked to the rediscovery of baroque music. The work of the pianists and harpsichordists Wanda Landowska and Eta Harich-Schneider should be emphasized, who made the instrument known to a wide audience through active concerts and teaching.

The harpsichord boom, which soon began, produced instruments that were less based on the historical model and more on the "modern" contemporary piano construction. In addition to the instruments for the Paris World Exhibition in 1889, the "Wanda Landowska" model developed in 1912 by the Pleyel company according to the specific wishes of the Polish harpsichordist with two manuals, four registers (16 ′, 8 ′, 4 ′; 8 ′) and six pedals proved to be the best as particularly influential.

- Following the example of the instruments mentioned, the historical "box construction" was replaced by a modern "grid construction". "The historical instrument, like the lute or the violin, has a resonance box that is closed on all sides and is limited at the bottom by a base plate, on the sides by thin ribs and at the top by a very thin, vibrating soundboard." If you look at a harpsichord in historical construction from below, you can see the "base plate". This is different with the harpsichord with a detent construction. Here you can see, as with the wing , the so-called "Rast" or " Raste ": a strong wooden beam construction, consisting of the " frame " (the frame of the Rast) and the "struts" (the struts, which are parallel, radial, star-shaped or are arranged in a grid). Between the beams the view falls directly on the soundboard .

- Looking down from the top of a "modern" Harpsichord, you see, if appropriate metal "pursuit" and a metal "trailer plate" as in a fortepiano in 1850, or a full "cast iron frame" as the modern wing: a stringed Delta of bronzed cast iron . In conjunction with the rest, these reinforcements absorb the tensile forces of the strings.

- The walls of the case were comparatively strong and usually consisted of multilayered veneered wood; and particleboard were used.

- The jumpers were made of brass, had screws for height adjustment and tongue adjustment and moved in a metal rake.

- The registers, pulls and couplings were operated by a series of pedals.

As a result, these instruments were very heavy, and the very thick walls made them a disadvantage in terms of sound - they had an organ-like, metallic-thin and not particularly stable sound. The peg-type harpsichord became less and less important in the second half of the 20th century, but it is the "original instrument" for harpsichord works by composers such as Manuel de Falla , Bohuslav Martinů , Francis Poulenc , Hugo Distler and Bertold Hummel .

Return to the sources

The fact that the sound of the Rasten harpsichords was gradually perceived as too rigid is related to the emergence of historical performance practice in early music . In return to instrument building traditions, building materials were used and craft processes were pursued as they were found and represented on the original instruments, for example the exclusive processing of solid wood for the body. After the Second World War, historically oriented harpsichord makers such as Hugh Gough in England, Frank Hubbard and William Dowd in America or Martin Skowroneck (Bremen), Klaus Ahrend (Moormerland-Veenhusen) and Rainer Schütze (Heidelberg) in Germany came ever more clearly to the fore. Skowroneck became known to an interested audience because the instruments he built for the harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt could be heard on numerous records.

Harpsichords in historical box construction have a very present, vibrating and far-reaching tone, which sounds more lively and less metallic than instruments with a peg construction. The historical models for this design are z. B. Original instruments by Ruckers (Flemish, 17th century), Giusti (Italian, 17th century), Mietke (northern German, early 18th century) or Taskin (French, 2nd half of the 18th century).

Today the historical construction is preferred by the leading harpsichordists, the relevant institutes and institutions for early music at the music academies and the harpsichord lovers in general.

Electronic variants

Some keyboards and electric pianos are equipped with harpsichord sounds. The Japanese company Roland offers an electronic harpsichord which, in addition to the sound, also simulates the feel of the game and offers a choice of several historical moods . Another electronic option is the GrandOrgue software , which works with samples of original harpsichords; old moods can also be used here.

Harpsichord music in the 15th to 18th centuries

overview

The harpsichord and its relatives virginal, spinet, claviorganum, etc. a. established themselves in the Renaissance (15th to 16th centuries). Early solo literature mainly consisted of intabulations of well-known melodies, songs, chansons , motets and madrigals , which are often decorated with exuberant ornamentation, as well as dances, e.g. B. by Attaingnant (1536), by Italian dance masters such as Facoli, Radino and Picchi , or by the German Jacob Paix .

From the early repertoire before around 1560, the works of the blind Spanish organist and keyboard virtuoso Antonio de Cabezón stand out due to their special quality, who in addition to the aforementioned genres also composed some artistic variations and so-called tientos - fugue-like original compositions in the style of a motet. The tiento became the typical form of Spanish and Portuguese keyboard music. Hundreds of pieces from the 16th and 17th centuries have survived, often very artistic and virtuoso, by composers such as Francisco Correa de Arauxo , José Ximénez, Pablo Bruna , Joan Bautista Cabanilles , and by the Portuguese António Carreira and Manuel Rodrigues Coelho and Pedro de Araújo , as well as many anonymous composers.

In Italy there was a first musical heyday with the two organists from San Marco, Claudio Merulo and Andrea Gabrieli . Many of their ricercari, canzones, and toccatas are not only suitable for the organ. Merulo's richly decorated canzones and toccatas in particular were groundbreaking in their time and were recommended by his student Girolamo Diruta as rehearsals for an elegant play on the harpsichord.

Another school of keyboard music arose shortly before 1600 in Naples, with the two main masters Ascanio Mayone and Giovanni Maria Trabaci . Their style already belongs to the early baroque and had a considerable influence on the music of the influential Girolamo Frescobaldi , who developed the toccata even more freely, composed artistic capricci and canzons, and left behind many variation partitas and dances. After Frescobaldi, the most interesting Italian harpsichordists were Bernardo Storace , who mainly left behind works of variations, Passacagli and a well-known Ciaconna; also Bernardo Pasquini, who composed an extensive harpsichord oeuvre - in addition to the forms mentioned, also small suites.

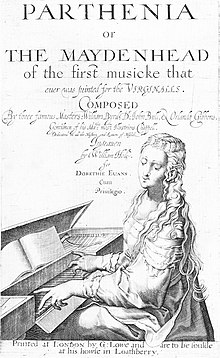

The standard repertoire for harpsichord and virginal includes the often highly virtuoso music of the English “virginalists” who worked between around 1570 and 1630, above all William Byrd , John Bull , Giles Farnaby and Peter Philips . In England at that time, the term virginalls meant all types of keel instruments, not just virginals. The Dutch organist Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck also wrote some attractive works for harpsichord, especially variations.

Under Louis XIV (1638–1715) the harpsichord became one of the favorite instruments of the French until the 1780s. The most important French clavecinists were Jacques Champion de Chambonnières , Louis Couperin , Jean-Henri d'Anglebert , François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau . They wrote suites that mainly consisted of dances and later of character pieces.

The most important German composer of harpsichord music before Bach was Johann Jakob Froberger , who composed many suites in addition to toccatas, ricercari, canzones and capricci. There is also a lot of interesting music for the harpsichord by composers such as Dieterich Buxtehude , Johann Caspar von Kerll , Johann Pachelbel , Johann Krieger and others. a. The first works that explicitly require a two-manual harpsichord come from Johann Kuhnau (including the Biblical Sonatas ). He is also considered to be the first to write explicit multi-movement sonatas for harpsichord.

Many works that are considered the highlights of music history today, such as B. fugues and suites by Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel or the highly virtuoso sonatas Domenico Scarlatti , originally written for the harpsichord.

In the 18th century the first concerts for harpsichord and orchestra were made, especially by Joh. Seb. Bach and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach , but also by Francesco Durante , Thomas Augustin Arne , Georg Anton Benda u. a. Handel's organ concerts can also be played on the harpsichord as an alternative. The harpsichord was sometimes used “obligatory” in chamber music, too; Johann Sebastian Bach's sonatas with transverse flute, viol or violin, and also the very different Pièces de clavecin en concert (1741) by Jean-Philippe Rameau have a place of honor .

Important works of the late period are: In France a. a. the works of Jacques Duphly ; in Germany the sonatas and fantasies of Bach's sons Carl Philipp Emanuel , Wilhelm Friedemann , Johann Christian and Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach , as well as by Georg Anton Benda and Johann Schobert ; in Austria early and middle works by Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ; in England the sonatas by Pietro Domenico Paradies and Thomas Arne ; in Spain the sonatas by Padre Antonio Soler .

In the baroque music until the beginning of the 19th century, the instrument was used not only for solo works, but especially to carry the improvised basso -Begleitung in chamber music, opera and orchestral music, which the harpsichord with his silvery glittery or rushing sound a characteristic Gives coloring.

Towards the end of the 18th century the harpsichord gradually was prepared by the hammer piano repressed (Forte Piano) - z expect yet. B. Mozart and Clementi especially in early and middle “piano works” with a reproduction on the harpsichord, and Beethoven's early and middle piano sonatas are also originally titled “for the harpsichord or the pianoforte” ( pour le clavecin ou pianoforte ), although Beethoven himself certainly preferred the piano. Because of its penetrating sound, the harpsichord continued to be used as a continuo instrument in opera until the early 19th century . B. in operas by Rossini .

Great composers

- Germany : Jacob Paix , Hans Leo Haßler , Christian Erbach , Heinrich Scheidemann , Samuel Scheidt , Johann Jakob Froberger , Matthias Weckmann , Dieterich Buxtehude , Johann Pachelbel , Benedikt Schultheiß, Johann Krieger , Georg Böhm , Johann Kuhnau , Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer , Christoph Graupner , Georg Friedrich Händel , Johann Sebastian Bach , Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

- Austria : Johann Caspar von Kerll , Alessandro Poglietti , Franz Matthias Techelmann, Georg Muffat , Johann Joseph Fux , Gottlieb Muffat , Joseph Haydn , Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- France : Pierre Attaingnant , Jacques Champion de Chambonnières , Louis Couperin , Jean-Henri d'Anglebert , Nicolas Lebègue , Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy , Louis Marchand , Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre , François Couperin , Jean-Philippe Rameau , Jean-François Dandrieu , Louis-Claude Daquin , Jacques Duphly , Claude Balbastre .

- Belgium : Peter Philips

- Netherlands : Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck , Pieter Bustijn

- England : William Byrd , John Bull , Giles Farnaby , Thomas Tomkins , Orlando Gibbons , Matthew Locke , Giovanni Battista Draghi , John Blow , Henry Purcell , Thomas Arne

- Italy : Andrea Gabrieli , Claudio Merulo , Marco Facoli, Giovanni Picchi , Antonio Valente , Giovanni Maria Trabaci , Ascanio Mayone , Ercole Pasquini , Girolamo Frescobaldi , Michelangelo Rossi , Bernardo Storace , Bernardo Pasquini , Azzolino Bernardino della Ciaia , Alessandro Scarlatti , Domenico Scarlatti , Giovanni Battista Sammartini , Giovanni Battista Martini , Pietro Domenico Paradise , Muzio Clementi

- Spain : Antonio de Cabezón , Hernando de Cabezón, Francisco Correa de Arauxo , José Ximénez, Juan Cabanilles , Antonio Soler

- Portugal : António Carreira , Manuel Rodrigues Coelho , Pedro de Araújo , Carlos Seixas , Frei Jacinto do Sacramento, Francisco Xavier Baptista

For English virginalists see also: Fitzwilliam Virginal Book .

For French harpsichord music see also: Pièces de clavecin .

Harpsichord music of the 20th century (selection)

- Helmut Bieler : Dialogue for two harpsichords (1971); Wave strikes for recorders, viols and harpsichord, performed for three instrumentalists (1978)

- Frederick Delius : Dance for Harpsichord (1929), Universal Edition, Vienna

- Violeta Dinescu : Prelude for harpsichord (1980)

- Hugo Distler : Concerto for harpsichord and 11 solo instruments (1930–1932)

- Thomas Emmerig: Johann Sebastian Plus for flute, violin, violoncello and harpsichord (1974)

- Manuel de Falla : Concerto per clavicembalo (o pianoforte), flauto, oboe, clarinetto, violin e cello (1926), Max Eschig, Paris

- Jean Françaix : Concerto pour Clavecin et Ensemble Instrumental (1959)

- Philip Glass : Concerto for Harpsichord and Chamber Orchestra (2002)

- Ron Goodwin : Theme melody or soundtrack for the Miss Marple films with Margaret Rutherford (1960s).

- Hans Werner Henze : Six absences pour le clavecin (1961)

- Bertold Hummel : Concerto Capriccioso for harpsichord and chamber orchestra (1958)

- Wolfgang Jacobi : Concerto for harpsichord and orchestra op. 31 (1927), music publisher CF Kahnt, Lindau

- Viktor Kalabis : Concerto for harpsichord and strings, dedicated to the harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková

- György Ligeti : Continuum for harpsichord (1968); Hungarian Rock , Chaconne for harpsichord (1978)

- Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf : Pegasos for harpsichord (1991)

- Frank Martin : Concerto for harpsichord and small orchestra (1951/52)

- Bohuslav Martinů : Concerto for harpsichord and small orchestra (1935)

- Peter Mieg : Concerto per clavicembalo e orchestra da camera (1953)

- Francis Poulenc : Concert champêtre for harpsichord and orchestra FP49 (1927–1928), for Wanda Landowska, dedicated to Richard Chanelaire

- Isang Yun : Shao Yang Yin (1966)

- Ruth Zechlin : Crystals for harpsichord and string orchestra (1975); Lines for harpsichord and orchestra (1986); Amor und Psyche , great chamber music with harpsichord (1966); Venetian Harpsichord Concerto (1993); 14 pieces for harpsichord / spinet (1957–1996)

See also the chronology of recorded compositions in Martin Elste: Modern Harpsichord Music - A Discography. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT; London 1995, pp. 275–288 (see bibliography below)

Harpsichord maker (selection)

Historical

- Germany: Hans Müller, Johann Maier, Michael Mietke , Gottfried Silbermann , Hieronymus Albrecht Hass , Gräbner (family), Fleischer, Christian Vater , Christian Zell

- France: Denis (family), Vaudry, Vincent Tibaut, Donzelague, François-Étienne Blanchet , Henri Hemsch, Pascal-Joseph Taskin

- Belgium: Ioes Karest, Lodewijck Grouwels, Ruckers (family; Antwerp), Dulcken (family), Albert Delin

- England: Lodewijk Theeuwes (Theewes), Benjamin Slade, Joseph Tisseran, Hitchcock , Hermann Tabel, Jacob Kirckman (German descent from Alsace as Jacob Kirchmann), Burkhardt Tschudi (Shudi), John Broadwood & Sons

- Italy : Venice : Dominicus Pisaurensis (or Venetus), Trasuntino , Giovanni Celestini , Giovanni Antonio Baffo; Milan : Annibale dei Rossi; Bologna : Giuseppe Maria Goccini; Rome : Hieronymus Bononiensis, Giovanni Battista Boni, Girolamo Zenti , Giovanni Battista Giusti , Giacomo Ridolfi; Florence : Vincentius Pratensis, Vincentio Querci, Giuseppe Mondini , Antonio Migliai, Bartolomeo Cristofori , Giovanni Ferrini, Vincenzo Sodi; Naples : Honofrio Guarracino; Messina : Carlo Grimaldi

- Spain: Maestre Enrique, Pedro Bayle, Mohama Mofferiz ("The Moor of Saragossa"), Pedro Luis de Bergaños (around 1629), Bartolomeu Angel Risueño (around 1664), Domingo de Carvaleda († 1684), Bartolomé Jovernadi (around 1635) , Pablo Nassare, Domingo Carballeda, Diego Fernández, Juan de Marmol

- Portugal: Antunes

Contemporary

- Germany: Klaus Ahrend, Ammer , Matthias Griewisch, William Jurgenson, Dietrich Hein, William Horn, Detmar Hungerberg, Matthias Kramer, Eckehart Merzdorf, Neupert, Georg Ott, Volker Platte, Gerhard Ranftl, Sassmann, Klemens Schmidt (Bayreuth), Martin-Christian Schmidt , Rainer Schütze, Martin Skowroneck , Sperrhake / Passau, Thiemann, Michael Walker, Kurt Wittmayer.

- Italy: Konrad Hafner ( South Tyrol )

- Switzerland : Bernhard Fleig, Jörg Gobeli, Markus Krebs, David Ley, Mirko Weiss

More can be found in the category: Harpsichord maker .

Harpsichordists

See: List of Harpsichordists and Category: Harpsichordist

Collections of historical keel instruments

The following list only contains collections that are accessible to the public; there are of course also important original instruments and collections in private hands.

- Belgium: Musée Instrumental ( IVme Département des Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire ) Brussels, Vleeshuis Museum Antwerp (Ruckers instruments).

- Denmark: Musikhistorisk Museum og Carl Claudius' Samling Copenhagen.

- Germany: State Institute for Music Research Prussian Cultural Heritage Berlin, Museum of Art and Industry Hamburg (Beurmann Collection), Museum for Musical Instruments of the University of Leipzig , German Museum Munich, German National Museum Nuremberg, Württembergisches Landesmuseum Stuttgart.

- England: The Benton Fletcher Collection ( Fenton House ) London, Museum of Instruments ( Royal College of Music ) London, Victoria and Albert Museum London.

- Italy: Museo degli Strumenti Musicali ( Castello Sforzesco ) Milan, Museo Nazionale degli strumenti musicali Rome.

- Netherlands: Gemeentemuseum The Hague.

- Austria: Museum Carolino Augusteum Salzburg, Musical Instrument Museum of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna.

- Portugal: Museu da Música Lisbon.

- Scotland: Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments ( University of Edinburgh ) Edinburgh.

- Switzerland: Basel Historical Museum .

- Spain: Museu de la Música Barcelona.

- USA: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments New Haven, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, Smithsonian Institution Washington DC

Similar instruments

literature

- Willi Apel : History of organ and piano music until 1700. Edited and afterword by Siegbert Rampe . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2004 (originally 1967).

- Andreas Beurmann: Historical keyboard instruments - The Andreas and Heikedine Beurmann collection in the Museum of Art and Industry Hamburg. Prestel, Munich a. a. 2000.

- Susanne Costa: Glossary of Harpsichord Terms, (English - German). Verlag Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main 1980.

- Martin Elste: Nostalgic music machines. Harpsichords in the 20th century. In: Kiel pianos. Harpsichords, spinets, virginals. Inventory catalog with contributions by John Henry van der Meer , Martin Elste and Günther Wagner. State Institute for Music Research Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 1991, pp. 239–277.

- Martin Elste: Compositions for nostalgic music machines. The harpsichord in 20th century music. In: Yearbook of the State Institute for Music Research Prussian Cultural Heritage 1994. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1994, pp. 199–246.

- Martin Elste: Modern Harpsichord Music - A Discography. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT; London 1995. ISBN 0-313-29238-8 .

- Igor Kipnis (Ed.): Harpsichords and Clavichords. Volume 2 of Encyclopedia of Keyboard Instruments. Routledge, New York / Oxford 2007, ISBN 0-415-93765-5 .

- Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003. (Engl .; with a detailed bibliography on the subject of harpsichord and keel instruments.)

- Edward L. Kottick, George Lucktenberg: Early Keyboard Instruments in European Museums. Indiana University Press, Bloomington / Indianapolis 1997. (Eng.)

- Bernhard Meier: Old keys - represented on the instrumental music of the 16th and 17th centuries. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2000.

- Hanns Neupert: The harpsichord. A historical and technical view of the keel instruments. 3. Edition. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kasel / Basel.

- Grant O'Brian: Ruckers - A harpsichord and virginal building tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1990.

- Edwin M. Ripin, Howard Schott, John Koster, Denzil Wraight, Beryl Kenyon de Pascual, Grant O'Brian u. a .: Harpsichord. In: Stanley Sadie (Ed.): The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians , 2nd edition. 2001, pp. 4-44.

- Christopher Stembridge: Music for the "Cimbalo cromatico" and other Split-Keyed Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Italy. In: Performance Practice Review, 5, no. 1, 1992, pp. 5-43.

- Christopher Stembridge: The "Cimbalo cromatico" 'and other italian Keyboard Instruments with nineteen or more divisions to the Octave ... In: Performance Practice Review, 6, no. 1, 1993, pp. 33-59.

- John Henry van der Meer: harpsichord, clavizitherium, spinet, virginal. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG) , subject part, vol. 2. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel / J.-B.-Metzler-Verlag, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 487-528.

- Denzil Wraight, Christopher Stembridge: Italian Split-Keyed Instruments with fewer than Nineteen Divisions to the Octave. In: Performance Practice Review, 7, no. 2, 1994, pp. 150-181.

- Denzil Wraight: Italian Harpsichords. In: Early Music, 12, no.1, 1984, p. 151.

- Denzil Wraight: The Stringing of Italian Keyboard Instruments, c. 1500 - c. 1650. Dissertation. Queens University, Belfast 1997.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ There were sometimes no register levers on historical instruments from Italy. On harpsichords like this, both registers always sounded simultaneously.

- ↑ This mainly led to the development and invention of opera around 1600.

- ↑ for the chromatic chanson Seigneur Dieu ta pitié.

- ↑ because the notes D and E sound on the corresponding upper keys.

- ^ For example, in Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

- ↑ That was u. a. with different string material: brass sounds a little deeper than the iron that was apparently used previously.

- ↑ These two registers cannot be used (not coupled) at the same time.

- ↑ It might make sense to point out that there was no exact separation of Austria and Germany in the historical period mentioned, because at that time they belonged to the German Empire and the Kaiser in Vienna was the German Kaiser. The assignment of some composers to just one country is therefore problematic. So stood Froberger z. B. 20 years in the imperial Habsburg service and lived for years in Vienna despite his travels. Kerll also worked in both Vienna and Munich, and Mozart's birthplace Salzburg was not even part of Austria's territory at the time. So it is not surprising that the music of all composers named under Austria was then (internationally) considered "German". On the other hand, the very international Handel spent a large part of his life in England, was naturalized there, wrote English vocal music and is rightly regarded there as an English composer.

- ↑ Although Philips was English, he lived in Brussels for most of his life.

- ↑ Draghi was Italian, but lived in England, and his music is completely un-Italian, but English.

- ^ D. Scarlatti lived in Portugal for 10 years and in Spain for 28 years. Much of his music shows Spanish influences, and he can be considered the head and founder of Iberian keyboard music.

- ↑ Paradies worked in London, and his virtuoso sonatas are influenced not only by Scarlatti but also by French music.

- ↑ Mohr here probably in the meaning of "Maure".

Individual evidence

- ^ Duden online: Harpsichord and Clavicembalo

- ↑ See key word: "Flügel, Clavicimbel." In: Heinrich Christoph Koch : Musical Lexicon. Frankfurt 1802, pp. 586-588.

- ↑ Duden online: harpsichord

- ↑ Kiel pianos. Harpsichords, spinets, virginals. Inventory catalog with contributions by John Henry van der Meer , Martin Elste and Günther Wagner . State Institute for Music Research Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 1991 (see in it the contribution by JH van der Meer).

- ↑ Ulrich Michels (Ed.): The Kiel instruments. In: dtv atlas on music. Boards and texts. Systematic part , volume 1. Munich 1994, p. 37.

- ↑ Article Kiel instruments. In: Brockhaus Enzyklopädie , 19th edition 1990, Volume 11, p. 669.

- ↑ Duden online: Kielflügel

- ↑ Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach : Attempt on the true way of playing the piano , first part, Berlin 1753 and second part, Berlin 1762. Facsimile -new edition by Bärenreiter, Kassel et al., 1994. Examples: 1st part, introduction: § 13, p. 9; and § 15, pp. 10-11; 2nd part, introduction, § 1, p. 1; and § 6, p. 2.

- ↑ See key word: "Flügel, Clavicimbel." In: Heinrich Christoph Kochs: Musikalisches Lexicon. Frankfurt 1802, pp. 586-588.

- ^ Duden online: Harpsichord .

- ↑ Reference to www.kalaidos-fh.ch with downloadable scientific study (as of April 1, 2018).

- ↑ Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 371-375.

- ↑ Martin-Christian Schmidt: The pedal harpsichord - an almost forgotten keyboard instrument. In: Cöthener Bachhefte , 8th contributions to the colloquium on the pedal harpsichord on 18./19. September 1997. Publisher: Bach memorial site Schloss Köthen and the Historical Museum for Mittelanhalt. Köthen 1998. Summary. ( Memento of December 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 87 kB) Retrieved on December 28, 2011.

- ↑ Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 71-75. Kottick refers to the extensive research of Denzil Wraight, who examined all extant Italian harpsichords, published numerous articles and wrote a scientific paper on them. See u. a. Denzil Wraight: Italian Harpsichords. In: Early Music, 12, no. 1, 1984, p. 151; and: Denzil Wraight: The Stringing of Italian Keyboard Instruments, c. 1500 - c. 1650. Dissertation. Queens University, Belfast 1997.

- ^ Grant O'Brian: Ruckers - A harpsichord and virginal building tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1990, pp. 40-41. Also: Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, p. 112.

- ↑ A two-manual instrument by Jean Denis II (Issoudun, Musée de l'Hospice Saint-Roch) is dated 1648 and is considered to be the earliest preserved French harpsichord. See Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, p. 163. Another harpsichord in the Beurmann collection in Hamburg was estimated by Beurmann himself to be “around 1630”, but this has not been verified. See Andreas Beurmann: Historical keyboard instruments - The Andreas and Heikedine Beurmann collection in the Museum of Art and Industry Hamburg. Prestel, Munich a. a. 2000, pp. 100-102.

- ↑ Martin-Christian Schmidt : The 16 'register in the German harpsichord construction of the 18th century. Grotesque or remarkable appearance with practical performance relevance? In: Eszter Fontana (Hrsg.): Festschrift for Rainer Weber. Halle 1999, ISBN 3-932863-98-4 . Pp. 63-72. (= Scripta Artium , Vol. 1. Series of publications from the Leipzig University's art collections).

- ↑ Susanne Costa: Glossary of Harpsichord Terms - Glossary of Harpsichord Terms (English - German). Verlag Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt 1980, p. 64f ( lute-stop, lute - cornet slide ... nasal register ... )

- ↑ South German harpsichords like Maier's harpsichord (1619) in the Carolino Augusteum Museum in Salzburg also have the registers arranged in a fan shape; they diverge towards the bass. This means that the 3 registers (with 2 strings) are very different. The nasal register and the dark register pluck the same string in different places. Therefore these two registers cannot be used at the same time. See Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 179-189.

- ↑ Four of six surviving instruments: a large, two-manual harpsichord from 1723 with an 8'-8'-8'-4 'disposition in Copenhagen, Musikhistorisk Museum; probably a similar harpsichord from 1721 in Göteborg, Göteborgs Museum (this instrument was later converted into a piano, the original arrangement was reconstructed by Lance Whitehead); and the two large 16 'harpsichords from 1734 in Brussels, Musée Instrumental, and from 1740 in a private collection in France. See Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 308-312.

- ↑ There is also a 17th century English harpsichord by Jesse Cassus with a lute stop . See Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 203 (Cassus), 285 (Dulcken), and p. 370 (Kirkman and Shudi).

- ↑ It is said to have been invented either by Pascal Taskin or by Claude Balbastre . Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, pp. 276 & 506 (footnote 80).

- ^ Andreas Beurmann: Historical keyboard instruments - The Andreas and Heikedine Beurmann collection in the Museum for Art and Industry Hamburg. Prestel, Munich a. a. 2000, pp. 109–111, here: p. 111 ( Mechanics ).

- ↑ Edward L. Kottick: A History of the Harpsichord. Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ Edwin M. Ripin, Denzil Wraight, Darryl Martin: Virginal. In: Stanley Sadie (Ed.): The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians , Vol. 26, 2nd edition, 2001, p. 780.

- ↑ Edwin M. Ripin, Denzil Wraight, Darryl Martin: Virginal. In: Stanley Sadie (Ed.): The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Vol. 26, 2nd edition. 2001, p. 780. Grant O'Brian: Ruckers - A harpsichord and virginal building tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1990, p. 35 and p. 311. (O'Brian quotes Klaas Douwes: Grondig Ondersoek van de Toonen der Musijk. Franeker, 1699; Facsimile: Amsterdam, 1970, p. 104f.)