Women in the military

Women in the military have played significantly different roles in the military over the centuries ; In earlier epochs, most cultures and states severely restricted or completely denied access to the armed forces for various reasons. Nevertheless, there are many individual examples in military history of women who fought in various tasks in the armed forces of their countries. In many cases, however, the women involved were only able to do this by disguising themselves as men .

Most states now admit women to their armed forces. However, the majority of these states still place a restriction on participation in combat operations . A conscription for women exists in 2017 in the countries Bolivia , China , Eritrea , Israel , North Korea , Norway , Sweden , Sudan and Chad .

Women in the war before the 20th century

Women as combatants

The image of women warriors who take part in battles on an equal footing with men can be found in Nordic and Greek myths ( Valkyries , shield maids , Amazons ). The ancient world of gods knows numerous armed goddesses ( Artemis / Diana or Athene / Minerva ), as well as other mythologies ( e.g. Kali , Durga , Andraste ). The Amazon myth is linked by Herodotus with the actually existing Sarmatians , who, according to him, descended from Scythians and Amazons. In fact, Sarmatian women graves with weapons were found, which at least proves the high status of these women, even if the evidence for Sarmatian women warriors such as Amage is thin.

Aside from myths, only a few cases before the 20th century reported of the open participation of women in armies. However, the participation of women in resistance wars or sieges was often handled less strictly - well-known examples are the American Margaret Corbin and the Spanish Agustina de Aragón , who fired guns as civilians and were then recognized as soldiers. The individual cases of “hero virgins” like Jeanne d'Arc or the disguised Eleonore Prochaska , who were subsequently mythically charged, are different . In cases like Philis de La Charce and Jeanne Hachette , even small combat missions were legendarily embellished by civilians; these women declared heroines. Martial law separations between combatants and non-combatants did not become established until the late 17th century: if the entourage or a city was attacked, women also participated in combat operations.

Women as commanders in ancient times

The role of women as a military leader is also seldom documented, even in the event that she ruled her country. In numerous cases, the role of these women was either exaggerated into heroic form or degraded by opponents, and the testimonies are too fragmentary for reliable information.

- In Egypt , female pharaohs were also the chief commanders of the armed forces: Ahhotep I led the liberation struggle against the Hyksos in the 17th century BC and Hatshepsut had military campaigns carried out for almost 22 years in the 15th century. However, this does not prove personal participation in the field.

- In China, in the 13th century BC, Queen Fu Hao is said to have taken over her husband's armed forces and led them victoriously in several battles. In the 2nd century, Huang Guigu was an army leader under Qin Shihuangdi .

- In the Middle East there were several rulers known for their warfare such as the Assyrian Šammuramat (9th century BC), the massage queen Tomyris (6th century BC) and the ruler Palmyras Zenobia (2nd century).

- Jingū is passed down from Japan as the legendary ruler who led an invasion of Korea.

- The city founder Messene and the fleet commander Artemisia I have come down to us as commanders from Greece .

- From Great Britain, Geoffrey von Monmouth reported on the legend queens Gwendolen and Cordelia, who drew and won against men at different times. Historically, however, is Boudicca , who led the British Iceni tribe against the Roman army in the year 60.

- Triệu Thị Trinh is known from Vietnam as a military leader in the rebellion of 248 against the Chinese Empire.

Disguised as men

Soldiers disguised as men, despite their occasional celebrity, represented rather historical exceptional cases, so that no generally valid statements are possible. Some have already been recruited in disguise without others knowing about them; still others had confidantes or smuggled in to replace a fallen fighter. However, female soldiers were only perceived as a scandal when the all-male professional army had emerged. Accordingly, there are very different reports on the treatment of female soldiers after their gender has been discovered - depending on the region, customs and any combat skills already demonstrated, they were punished, banished from the army or even honored. In favorable cases, they were even allowed to continue fighting until the end of the war and later received pension payments - this practice is incompletely documented until the beginning of the 19th century. In other cases, however, the actual gender was only determined after the combatants had died.

Dahomey

A prominent example of a female premodern army was in the West African kingdom of Dahomey , which had a women's army from the 17th to its fall in the 19th century. This troop was led by officers and strictly separated from the male army.

There are various and unsecured information on the history of the formation of this women's army. The elite corps of women mainly formed the palace guard. Since men were not allowed into the palace, it is believed that the women's army was originally formed to protect the royal harem . Another popular theory is that a female fake force (set up to deceive the enemy), contrary to expectations, proved its worth in a battle.

The participation of the royal elite troops in the capture of Ouidah in 1730 was attested . A hundred years later, King Gezo is said to have used the women's regiments for the first time in regular battles, presumably to strengthen his palace guard in domestic political disputes. Out of a total of 12,000 soldiers, there were 5,000 women warriors who were referred to as "Amazons" in the western world.

Hakka culture and Taiping uprising

In the Hakka culture in southern China , fighters and advancement to the ranks of officers were not uncommon. During the Taiping uprising , which was largely supported by Hakka , female fighters camped separately from men, in accordance with the Christian ideology of leader Hong Xiuquan . Since female soldiers were considered a specialty around the world, not least in China, at that time, numerous reporters focused on this fact. However, the Taiping uprising is no longer considered to be an actual emancipation achievement.

Women as motivators in battle

It is said of various combat organizations that women on the edge of the battlefield cheered the fighters on. Corresponding reports can be found about the Teutons in Tacitus ' Germania , according to which the entire family association took part in fights. In the pre- and early Islamic Arab tradition, it was customary for priestesses to accompany the fighting and cheer them on with music and shouting during the battle. In the Battle of Maiwand , the young woman Malalai is said to have contributed to the victory of the Afghan troops through her singing; she is now honored as a national heroine.

Women in the train of the early modern age

Women as well as civilian suppliers, traders and craftsmen were an integral part of the entourage in Europe from the 16th to 18th centuries and thus played a decisive, albeit indirect, role during the war. From around 1500 until the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, mercenary armies were the order of the day, specially hired for wars. The wives of officers, mercenaries or craftsmen accompanied them, prepared the food, took over warehouse services or even digging work and were generally active as service providers in the camp. Thus there were maids , cooks, nurses, shopkeepers and sutlers , prostitutes and day laborers in the mercenary troop, who often followed the mercenaries with their children and looked after them and participated in the booty. There were special officers to organize the entourage, such as the so-called whore women or comparable positions.

After the excesses of the Thirty Years' War, standing armies were formed and the armies became more professional. With the advent of army logistics and quartermasters , the entourage was to be streamlined, which had previously grown to one and a half times the size of the fighting troops and, with its corresponding material consumption, represented the army's weak point more than ever. In the event of war, the careful planning often came up against structural limits: The Prussian Army provided places for soldiers 'wives in the barracks and brought them into the field during the Seven Years' War . The officially small entourage was still supplemented by additionally hired or attracted (also female) staff.

However, women and children in the wake of the army were increasingly seen by the commanders as the main reason for lack of discipline among the troops and crime in the camp. Prostitution, illegitimate relationships and finally the presence of women were increasingly prevented by regulations until women were completely banned from the self-image of modern European armies at the beginning of the 19th century.

Hospital staff

Due to the historical situation of exile from the entourage, women were no longer tolerated as nursing staff in hospitals in many countries until the 19th century . In England around 1850 the nurse - just outside of the religious orders active in charity - had the bad reputation of alcoholism, unreliability and prostitution. But male nurses were also rarely well trained, and occasionally slightly wounded people without basic knowledge were used as nurses. On the occasion of the conditions in the field hospitals of the Crimean War , the Briton Florence Nightingale set in motion a fundamental reform of the nursing, health and medical services, fighting against corresponding social resistance and prejudice. There was also a corresponding movement in the USA during the Civil War , with prominent representatives being Clara Barton , Mary Edwards Walker and Dorothea Dix . As a nursing staff, a single field of activity was again possible for women in the military from the end of the 19th century, but mostly without a corresponding rank.

Women in the military from the 20th century

A decisive counter-movement against the displacement of women from the war in the 18th and 19th centuries can only be demonstrated in several countries from the First World War , when military success depended more than before on the industrial production of the countries involved in the war. Thousands of men who had previously worked in armaments factories, among other things, were called up for military service. Because of the need to continue production, women were employed to a considerable extent in the companies concerned. There they took on jobs that were previously reserved for men. After the war ended, a large proportion of women returned to traditional roles . In World War II was repeated this development, but on a larger scale. In addition, for the first time, there was a significant number of women in the armed forces of some of the participating countries. As a rule, special, separate units were created for this, such as the Women Airforce Service Pilots in the USA . In all such cases, these units were only meant to be temporary and were initially abolished after the war.

Australia

Women were primarily used as auxiliary personnel in Australia during World War II. This began with the formation of the WAAAF (Women's Auxiliary Australia Air Force) , which existed from March 1941 to December 1947 and was also the largest of the women's services. It had been discussed since January 1940 because Australia could not meet the obligations of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan without mobilizing additional forces . By August 1945, 27,000 women had signed up to the WAAAF.

Based on this model, the AWAS ( Australian Women's Army Service ; comprised 20,000 women in 1944) and the WRANS ( Women's Royal Australian Naval Service ; comprised 3000 women) were formed, which, like the WAAAF, were gradually wound up again after the end of the war until 1947. The Australian Women's Land Army , which was a voluntary agricultural worker during the World War, was not a military organization .

As early as the Korean War , women were recruited from 1951 onwards, albeit on a much more modest scale. The newly established WRANS limited women's service to Australian naval bases with initially 250 positions. It was retained as a permanent institution in 1959 and expanded to almost 700 positions by 1970. Instead of the WAAAF, the WRAAF (Women's Royal Australian Air Force) was created in 1951 , but this never achieved greater importance and was incorporated into the normal RAAF in 1977. Instead of the AWAS, the WRAAC (Women's Royal Australian Army Corps) was founded in 1951 . The female military personnel recruited in this way were deployed in various service, administration, teaching and logistics activities. By the end of the 1970s, it was largely integrated into the normal military apparatus.

With the law, which banned discrimination based on sex in 1984, the last separate structures (especially with WRANS and RAN ) were dissolved. From 1992 almost all positions could be filled regardless of gender. Only women were not allowed to take part in combat missions until 2013; women are currently not represented in the Special Forces either .

Germany

Empire

In 1918, a voluntary group of 100,000 women was trained as telephone operators, radio operators and telegraph operators in the Reichsheer . Although they were not part of the army, they were subject to military discipline and jurisdiction . They were supposed to replace the male soldiers in a news force. The end of the war prevented this and they were no longer used.

time of the nationalsocialism

During the National Socialist era , boys and girls received pre-military training. The Defense Act of 1935 stated:

"In the war, every German man and woman is obliged to serve the fatherland beyond compulsory military service."

This laid the foundations for the civil and armed use of women in World War II. As part of the compulsory national labor service , women also became civil servants . They enabled the Wehrmacht to outsource many military areas of responsibility. Although women were excluded from the soldier's profession due to National Socialist ideology, several hundred thousand girls were forcibly used as flak helpers during the war .

GDR

In the NVA , the principle of equality applied. Although women were in principle exempt from military service, all branches of service were open to them on a voluntary basis. At first they could only enter the lower rankings up to ensign. From the year 1984, however, the first female were officers in the officers' academies trained. The highest known rank of a female NVA officer was a colonel . However, there are no known general ranks that would have been awarded to women. With the abolition of the NVA in 1990 and the integration of military personnel into the structures of the Bundeswehr, women were faced with the problem that they had no legal right to exist there. With Order No. 41/90, Defense Minister Rainer Eppelmann ordered the immediate dismissal of all female members of the army with effect from September 30, 1990, with the exception of the medical service. For some posts they were given the opportunity to take up a new civilian employment contract. Female officers and ensign students were integrated into the civilian vocational preparation system and were able to continue their studies as civilians at the NVA teaching institutions.

Federal Republic

After the Bundeswehr was founded in 1955, women were initially excluded from all military tasks. The Basic Law of the young Federal Republic of Germany stipulated in Art. 12a : " You (women) may under no circumstances do service with a weapon ". The strict ban was based on the experience of the Nazi state . However, since the Basic Law stipulates the separation of armed forces and civil defense administration , women worked in civil functions for the Bundeswehr from the start. In 2003 there were 49,700 women (over a third of civilian employees).

On February 19, 1975, the Federal Cabinet of the Helmut Schmidt government approved the proposal of the then Defense Minister Georg Leber to employ licensed doctors, dentists , veterinarians and pharmacists as medical officers in the Bundeswehr. After changing the Soldiers Act and the Military Disciplinary Code , the first five female medical officers began their service on October 1, 1975. This exception was made because medical soldiers are not considered combatants under international law and are therefore not allowed to be attacked or to fight. Since defense out of self-defense or as emergency aid for non-combatants is allowed, these women were also given basic training on the weapon.

In June 1988, Defense Minister Rupert Scholz decided that women could pursue all careers in medical and military music service . So far, only women with a license to practice medicine have been employed in the respective careers of the medical service, but no officer candidates . On June 1, 1989, 50 female medical officer candidates began their service with the armed forces for the first time with the drafted recruits . From January 1991, career groups for NCOs and men in the medical service and in the military music service were opened for women. On April 1, 1994, Verena von Weymarn became the first woman in the Bundeswehr to become general physician . She was the first of five women in the general rank to date. The others are Gesine Krüger , Erika Franke , Almut Nolte and Nicole Schilling . In October 2013 Franke became the first woman to achieve the rank of general staff doctor, Krüger the second (2016). Nevertheless, the principle remained that women should be excluded from working with weapons.

A radical change in this situation did not occur until the new millennium through a decision of the European Court of Justice , which on January 11, 2000 in the Tanja Kreil ./. The Federal Republic of Germany ruled that the German legal provisions that completely exclude women from working with weapons violated the Community law principle of equality between men and women . Since January 1, 2001, all career paths in the Bundeswehr have been open to women without restriction. This was made possible by a constitutional amendment, which was necessary after the judgment of the ECJ. Since then it has been stated in Article 12a of the Basic Law: “ You (women) may under no circumstances be obliged to serve with a weapon ” (previously : “ You (women) may not under any circumstances serve with a weapon ”). The implementation of the ECJ ruling has been regulated since January 1, 2005 by the law enforcing the equality of soldiers in the Bundeswehr . According to a decision by the Federal Constitutional Court, the fact that the general conscription that existed until June 2011 only affected men does not contradict the principle of equal rights of Art. 3 GG.

22,665 women soldiers serve in the Bundeswehr, 5,795 of them officers (June 2020) . Overall, they make up 12.4% of all soldiers. Based on experience in other armed forces, the Bundeswehr expects the proportion of women to rise to around 15% in the coming years.

Women are still represented in the Bundeswehr medical service by a large margin . 35.5% of the women are employed there. According to its own statement, the Federal Government has no knowledge that the integration of women in the country's armed forces, apart from individual cases, leads to problems. For women, there are lower physical performance requirements for the entrance test and later professional practice.

France

In 2010 the proportion of women in the French armed forces was 15.2%. Women are allowed to serve in all units except on submarines and in the counter-insurgency of the gendarmerie . Nevertheless, the proportion of women in certain units is still very low, including the Marine Infantry (Commandement des Fusiliers Marines Commando) (9 women soldiers = 0.4%). Women are still denied access to the French Foreign Legion , even if there are some female officers who have been transferred to the Foreign Legion by the French army for administrative tasks. Susan Travers was the first and to date only woman to officially serve in the French Foreign Legion. She took part in battles in World War II and the Indochina War.

After the suspension of compulsory military service at the end of 2002, the mandatory military registration was extended to girls.

Great Britain

The first unit of the United Kingdom's armed forces in which women played a role was the Women's Royal Air Force , an auxiliary unit of the Royal Air Force which existed from 1918 to 1920. Today, of the 196,650 soldiers in the United Kingdom, 17,900 are women, including 3,670 officers. This corresponds to a share of 9.1% and 11.2% for officers.

Israel

Some women already served as transport pilots during the Palestine War. Even then, many women took active part in combat operations due to the lack of personnel, but later they were denied service in combat units.

In Israel women have also been subject to compulsory military service since the founding of Israel . However, one third of women are exempt from service, mostly for religious reasons (no obligation to provide evidence required). Instead, they serve in a variety of technical and administrative support posts. Israel is one of the few countries in the world that provides for military service for women, but at two years of age it is shorter than the three-year military service for men and also pays better. Participation in combat operations, which was only made possible again by a court ruling from 1994, remains voluntary.

That year, Alice Miller, a Jewish immigrant from South Africa, told the Supreme Court of a landmark decision that the Israeli Air Force should open its pilot training to women. During the War of Independence and the Sinai Campaign , women had already flown transport machines, but the Air Force later closed its ranks for women. Alice Miller then failed the recruitment test, but despite this, due to her initiative, numerous uses were opened to women. The first female fighter pilot received her pilot's badge in 2001. Since 2005, 83% of the military posts have been open to women, including service in the artillery and on warships (with the exception of submarines), but there are only 2 combat battalions made up of both sexes . In the Caracal Battalion , named after a cat whose sexual dimorphism is low, 70% of the soldiers are now women. A total of around 450 women serve in combat units of the Israeli security forces, very often in the border police. However, the use in combat units for women remains voluntary.

In 2002, 33% of the two lieutenant ranks and 21% of the captains and majors , but only 3% of the senior officers were women. With a controversially discussed decision, the women's corps command was dissolved in 2004 on the grounds that it was a contradiction and an obstacle to the full integration of women as normal soldiers without special status in the armed forces. However, at the insistence of feminists , the chief of staff retained the post of adviser on women's affairs.

At the end of 2011, the proportion of women in the Israeli military was 33%, in officers 51%, in combat troops 3% and 15% in technical personnel.

Norway

The proportion of women in 2009 was around 7%. Since 2009 women have also been obliged to be examined , but military service has remained voluntary. In 2015, general conscription was also introduced for women, with a large majority in parliament . Only the Christian Democratic Party (10 out of 169 seats) voted against. The first women will be called up from 2016. Norway was the first army to set up a special unit with women only with the Jegertroppen in 2014.

Austria

Women are not placed on an equal footing with men in the course of general conscription , but have been able to voluntarily serve in the armed forces since 1998 and have the right to terminate this service. They have lower physical performance requirements for entrance tests and in later professional practice (see Swiss Army ). In 2010, 348, slightly more than 2% of the total of almost 15,000 professional soldiers are women, including 70 competitive athletes. Despite the high level of interest at the beginning, the targeted several thousand female soldiers could not be reached.

The share of female civil servants is around 30%.

Already in the time of imperial Austria there were women in the Austrian armed forces, but they all pretended to be men in order to be able to take up their service with the weapon. During the First World War , Viktoria Savs and Stephanie Hollenstein became acquainted with their work at the front. From the time before, Johanna Sophia Kettner and Lieutenant Francesca Scanagatta should be mentioned at this point.

The first officer of the Austrian Armed Forces was Sylvia Sperandio .

Poland

In April 1938, the conscription law provided exceptions for voluntary service by women in the medical service, in the anti-aircraft artillery and in communications. In 1939, a military training organization for women was set up under the command of Maria Wittek .

During the Nazi occupation , several thousand women in the Home Army supported the Polish resistance against Germany. This prompted the German occupiers to set up separate prisoner-of-war camps for over a thousand women after the Warsaw Uprising was put down in 1944 .

Since a new law from 2004, all areas of the Polish Army are open to women. The number of female military personnel on June 30, 2007 was 800.

Sweden

Women have also served in the Swedish military for over 80 years . The military volunteer organization for women " Svenska Lottakåren ", founded in 1924, is part of the Swedish armed forces, in which the service providers mainly perform civilian tasks, as well as transport, IT support, organization, crisis management and much more. In exceptional cases, as well as during the Second World War, the women in Lottakåren also did standby duty with weapons. Today the organization has around 18,000 members.

With the entry into force of the Swedish Equal Opportunities Act in 1980, women were admitted to service in the Swedish Air Force , and in the following year for officer service in the Army and Navy . A reform in 1989 provided for all positions and tasks to be allowed for women, including in combat operations at the front. Since then women may officially hold any civil and military service of the Swedish Armed Forces, and it was possible only five years later, the basic military training the military to make to perceive without subsequent officer training. The Swedish Defense University (Försvarshögskolan) conducts gender research with a focus on the situation of soldiers and other female personnel in the Swedish armed forces.

Of the total Swedish military personnel, 18% are women. With 444 professional officers in 2007, they accounted for around 5% of the civil servants in the Swedish armed forces, while around 40% of the Swedish armed forces were women, and in the same year 5% of the Swedish soldiers deployed abroad or on standby duty were women.

Switzerland

At the beginning of the Second World War, the women's service was founded in Switzerland . It existed until 1985; from 1986 to 1994 it was called Military Women's Service . Even today fit-for-duty Swiss women can do voluntary military service, but since 2007 they have had to meet the same physical performance requirements as men. There is also the Red Cross Service , in which women do voluntary military service.

Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union , due to the military emergency at the beginning of the German-Soviet war , women were also deployed directly to the front, while the image of caring women was still propagated on the home front. Although the majority of the approximately 800,000 women in the Red Army were radio operators or paramedics, there were also special facilities in which snipers, leadership cadres and pilots were trained. The night witches' bomber pilots were a notorious air force also in Germany . After the "Great Patriotic War" these women were demobilized again.

The National Socialist regime saw the equal commitment of men and women as evidence of the degeneracy of Soviet society. Soviet women soldiers ( defamed as shotgun women in Nazi language ) were to be shot immediately after capture.

Turkey

Even though women were admitted for the first time in 1955, the proportion of women in the Turkish armed forces in 2003 was 0.1% according to NATO reports. This rate rose to 3.95% in the following year and was 0.9% in 2014.

United States

Women in the USA were given regular access to the US Army , even if only temporarily, at the beginning of the USA's entry into World War II. At that time, separate units for women were set up in the armed forces of the United States Armed Forces : The Women's Army Corps (WAC) as part of the US Army began in May 1942. This was followed in August 1942 by the WAVES as part of the US Navy and in September 1942 by the Women Airforce Service Pilots , whose primary task was to conduct transfer flights for the US Air Force in order to keep male pilots free for combat missions. The United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve followed in April 1943 . All of these units were originally intended to be temporary and were largely, if not completely, demobilized after the end of the war.

Permanent access to all branches of the armed forces was granted to American women three years after the end of World War II when the Women's Armed Services Integration Act came into force on June 12, 1948 . Restrictions were gradually lifted in the following decades. Since the late 1970s, women have been allowed to study at the military academies and serve on unarmed ships, as well as fly transport and tanker planes. After serving thousands of women in the Gulf War , President Clinton lifted many of the remaining restrictions in 1994 and allowed women to serve on armed ships and pilot fighter jets. Today all areas of the United States Armed Forces are open to women with the exception of service as crews on submarines . Their share in the armed forces is around 14% 60 years after the opening. Of the officers in the general rank, 5% are female, which is 57 in absolute numbers. On November 14, 2008, Ann E. Dunwoody was the first woman in the USA to be raised to the rank of general . She headed the US Army Materiel Command (AMC) with responsibility for procurement, deployment and logistics for the Army.

For the previous restrictions on submarines, the prevailing tightness there and the associated extensive compulsion to forego almost any privacy for the staff were named. However, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates approved a move away from this stance in February 2010. One of the reasons given for this was that more space was available on newer submarine classes such as the SSBNs or SSGNs .

The sense of excluding women from combat missions with ground troops is now controversial because in asymmetrical warfare a clear separation of front and support units is often not possible. As before after the Gulf War, the experiences from the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have led to the removal of almost all remaining restrictions. From 2016, women are to be fully integrated into service in all combat units such as the infantry.

In 2011, the proportion of women in the Air Force was 19%, in the Navy 17%, in the Army 13% and in the Marine Corps 7%.

Well-known soldiers

- Joan of Arc

- Jacqueline Cochran

- Eileen Collins

- Tammy Duckworth

- Ann E. Dunwoody

- Lynndie England

- Kara Fatma

- Erika Franke

- Sabrina Harman

- Marcelite J. Harris

- Kenau Simonsdaughter Hasselaer

- Grace Hopper

- Mariam al-Mansuri

- Gesche Meiburg

- Andrea Leitgeb

- Anna Lühring

- Jessica Lynch

- Eleonore Prochaska

- Verena von Weymarn

criticism

Physical performance

On average, women have around two thirds of the physical capabilities of men. In the military sector, women are often given significantly lower physical performance criteria in recruitment and fitness tests. In the Swiss Army, this preference was reversed in 2007.

The Social Science Institute of the Bundeswehr has compiled the international situation regarding the physical performance of women in combat operations and behind the lines:

Women have an average of 55% of the muscle strength and 67% of the endurance capacity of men. The top 20% of women have the same physical capabilities as the worst 20% of the average male population. Only 3% of 65,000 US Army soldiers examined who had to perform physically demanding tasks performed as required. 45% of female marines in combat training are unable to throw a hand grenade so far that they would not injure themselves or their comrades.

Demands for more training for women soldiers showed that men were much better trained in joint training programs. The men increased their leg strength by 38% compared to the women and their stamina by 48%. The differences in upper body strength were even clearer. The men increased by 270% compared to the women, and the endurance by 473%. A higher training load has a variety of effects.

During an operation, the military medical service requires an average of ten women to achieve the same performance as six men with stretchers. Changing tires on the truck is difficult due to the weight of the tires. The same applies when unloading heavy equipment or team tents. In the Second Gulf War (First Iraq War) , Cpt. Mary Roou explained the possibilities of protecting her supply unit from enemy fire as follows: “ There is no way that women can dig foxholes or as many as may be required, as men! "(German:" There is no way that women foxholes dug in sufficient number, as it could Men "!)

After a successful lawsuit against the British Air Force, female soldiers will be allowed to take smaller steps (69 instead of 76 centimeters) than their male comrades when marching. The longer stride had damaged the back and pelvis. In the future, women soldiers will set the pace in troops made up of men and women. Former Defense Secretary Gerald Howarth described the case as “ This case is completely and utterly ridiculous - it belongs in the land of the absurd. "(German:" ... completely ridiculous - it belongs in the land of the absurd. ")

In January 2014, the US Marines suspended the planned introduction of pull-up tests for female soldiers because "a little more than half of the women who took part in a training course did not manage to do three pull-ups, but the army did not want to create any insurmountable hurdles for women." To be able to lift one's own weight, a measure of the strength in the upper body and in combat is necessary to rescue comrades, to be able to climb over a wall and to carry heavier ammunition. In combat, US marines have their own equipment of around 40 kg, and gunners have an additional 25 kg.

Concerns about troop morale and combat effectiveness

After the Palestinian War , Israel excluded women from combat units. The main reason for this decision were incidents in which male soldiers were protecting their female comrades instead of ending the unit's mission. When female soldiers fell in action, the morale of the troops suffered significantly more. Furthermore, the opposing Arab troops hesitated longer to surrender to women. It was also found that women in captivity were exposed to higher risks than their male comrades, namely the risk of being raped. Although female recruits were admitted to combat units in 2007, their share of these amounts to around 3% - even though women make up 33% of the Israeli armed forces .

In 2011, 35.8% of the male and 15.8% of the female German soldiers complained about a loss of combat strength due to the inclusion of women.

A long-term study by the US Marine Corps found that units made up of women and men are not as strong as all-male units. In 69% of the tasks, all all-male units were better than the mixed ones. Only in 1.5% of the exercises were the mixed units better than all male units.

Other concerns

Female veterans have a suicide rate six times higher than women who never served in an army. The suicide rate among male veterans, however, is less than twice that of male non-veterans.

A study on the integration of women in the Austrian Armed Forces showed that female soldiers are exposed to a three times higher risk of bullying than their male colleagues.

Studies have shown that women are more than twice as likely to have musculoskeletal injuries when they are on duty. The female skeleton is also less dense and more prone to breakage. In the English army, pelvic fractures have often been found and they have now stopped conducting joint training courses for soldiers.

One third of 450 women soldiers questioned reported urinary incontinence during exercise and combat exercises. This has an impact on the additional provision of hygiene and health facilities for female soldiers during combat operations, where extremely primitive conditions often prevail.

Movies

- Field diary - Alone among men . Documentary by Aelrun Goette, Germany 2001: about four women in the Bundeswehr

- Soldier Girls. Documentary by Nick Broomfield , USA 1981

- Swing Shift - temporary love . Drama by Jonathan Demme, USA 1984: about women in the armaments industry during the Second World War

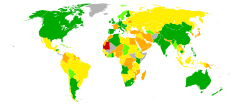

Share of women in the military worldwide

The following list contains data from different countries at different times:

| country | Women | year | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

33.0% | 2011 | 51% officers, 3% combat troops, 15% technical personnel. Conscription for women. |

|

|

> 30.0% | 2014 | own information, not verified |

|

|

30.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

23.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

23.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

> 20.0% | 2014 | own information, not verified |

|

|

~ 20.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

~ 20.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

17.3% | 2007 | |

|

|

17.3% | 2007 | |

|

|

15.5% | 2010 | |

|

|

15.3% | 2007 | |

|

|

14.3% | 2009 | Reserve 23.7%, National Guard 14.0% |

|

|

13.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

13.0% | 2009 | Women in officer rank 7% |

|

|

12.8% | 2000 | |

|

|

12.4% | 2020 | When assessing their physical performance, women receive a gender bonus. In October 2019, 30,691 of the 81,814 civilian employees were female (37.51%). |

|

|

12.2% | 2006 | |

|

|

12.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

12.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

~ 10.0% | 2014 | Desired quota: 30% |

|

|

~ 10.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

9.3% | 2007 | Women in officer rank 11.2% (2006) |

|

|

9.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

8.7% | 2007 | |

|

|

8.3% | 2006 | |

|

|

8.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

7.0% | 2009 | In 2014, general conscription was also decided for women. Women have been drafted since mid-2016. |

|

|

6.4% | 2007 | |

|

|

6.0% | 2006 | |

|

|

5.7% | 2010 | |

|

|

5.7% | 2006 | |

|

|

5.6% | 2007 | |

|

|

5.4% | 2007 | |

|

|

5.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

5.0% | 2009 | |

|

|

3.1% | 2006 | |

|

|

3.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

2.6% | 2007 | |

|

|

2.5% | 2015 | Conscription for men only. Lower physical performance requirements apply to women. 29.5% female civil servants. |

|

|

1.0% | 2014 | |

|

|

1.0% | 2007 | |

|

|

0.1% | 2014 | Desired quota: 10% |

| country | Women | year | Remarks |

See also

literature

- The woman as a soldier. The “Gorch Fock” scandal, Minister zu Guttenberg and the use of women in the armed forces . IfS , Schnellroda 2011, ISBN 978-3-939869-17-7 .

- Jens-Rainer Ahrens, Maja Apelt, Christiane Bender (eds.): Women in the military. Empirical findings and perspectives on the integration of women in the armed forces . VS Verlag , 2005, ISBN 3-8100-4136-X .

- Svetlana Alexandrovna Alexievich: The war has no female face . Henschel, Berlin 1987, ISBN 978-3-362-00159-5 .

- Women in military service . In: Defense . Issue 11, 1965, pp. 576 ff .

- Women in national defense . In: Information for the troops . Volume 4, 1975, pp. 50 ff .

- The women in World War II . In: Library for Contemporary History (Ed.): Annual bibliography . Stuttgart 1964.

- Rüdiger von Dehn: Images of women in US propaganda . In: Military History Research Office (ed.): Military history . Issue 4, 2009, ISSN 0940-4163 , p. 8 .

- Wolfgang Fechner: No chance for women? The new training and use catalog . In: loyal . Issue 8, 1975.

- Ursula von Gersdorff : women in military service. 1914-1945 . DVA , Stuttgart 1969, DNB 456654356 .

- Luise Hess: The German women's professions in the Middle Ages . Neuer Filser-Verlag, Munich 1940, DNB 580173550 .

- Uta Klein : Military and Gender in Israel . Campus , Frankfurt a. M. et al. 2001, ISBN 3-593-36724-6 .

- Margarete Schickedanz: German women and German misery in the world war . Leipzig / Berlin 1938, DNB 361691025 .

- Armin A. Steinkamm (Ed.): Women in military armed service. Legal, political, sociological and military aspects of the deployment of women in the armed forces with special consideration of the German Federal Armed Forces and the Austrian Federal Armed Forces (= military service and society. Volume 6). Nomos, Baden-Baden 2001, ISBN 3-7890-7407-1 .

- Ludger Tewes : Red Cross Sisters. Her use in the mobile medical service of the Wehrmacht 1939–1945. Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-506-78257-1 .

- Werner Winterstein: The employment of women in the German armed forces from 1914 to 1945 . In: Bundeswehrverwaltung . 1976.

- Jasna Zajcek: Among soldiers. A front report . Piper , 2010, ISBN 978-3-492-05369-3 .

English:

- Kirsten Holmstedt: Band of Sisters. American Women at War in Iraq . 2007, ISBN 0-8117-0267-7 .

- Alison Morton: Military or civilians? The curious anomaly of the German Women's Auxiliary Services during the Second World War . 2012.

- Jessica Amanda Salmonson: The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era . 1991, ISBN 1-55778-420-5 .

- James E. Wise, Scott Baron: Women at War. Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Conflicts . 2011, ISBN 1-59114-972-X .

- Janis L. Karpinski: One woman's army. The Commanding General of Abu Ghraib tells her story . with Steven Strasser. Hyperion, New York 2005, ISBN 978-1-4013-5247-9 (English).

- Helena Carreiras, Gerhard Kümmel : Women in the Military and in Armed Conflict (= series of publications by the Social Science Institute of the Bundeswehr . Volume 6 ). 1st edition. Springer VS , Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15834-1 (English, limited preview in the Google book search).

Web links

- Bundeswehr : Women in the Bundeswehr: Europe made it possible. In: Bundeswehr.de. October 31, 2019 (dates).

- NATO : Gender perspectives in NATO Armed Forces. In: NATO.int. Portal page August 22, 2019 (English; with links to dates).

- Christine Eifler: A quiet opening: female soldiers in the Bundeswehr. In: Science and Peace. 2002, No. 2: Women and War (on the social impact of women in the Bundeswehr).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Central Intelligence Agency (CIA): Field Listing: Military service age and obligation. ( Memento of May 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: The World Factbook . April 23, 2009, accessed December 12, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d Report: Indepth - international: Female Soldiers: Women in the military. ( Memento of May 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: CBC News Online . May 30, 2006, accessed December 12, 2019.

- ↑ a b Report (APA): Norway introduces compulsory military service for women: The first women can be called up from 2016. In: dieStandard.at . October 15, 2014, accessed December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Message: Military service: Sweden reintroduces conscription. In: Zeit Online . March 2, 2017, accessed December 12, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d Back then , October 2002 edition "Women in War"

- ↑ a b Ulf Hagemann: The Kingdom of Dahomey between the slave trade and the French colony , first published: October 1, 2002 at geschichte.uni-hannover.de (accessed on July 29, 2016)

- ↑ Dagmar Hemm: Ways and wrong ways of women's liberation in China Edition global Munich, 1996. ISBN 3-922667-33-3 . P. 23.

- ↑ RJQ Adams: Arms and the Wizard. Lloyd George and the Ministry of Munitions 1915-1916 . Cassell & Co Ltd., London 1978, ISBN 0-304-29916-2 , Particularly, Chapter 8: The Women's Part.

- ^ Mazoe Ford: Women in the Australian Defense Force: the progress from challenges to choices . ABC , April 22, 2015.

- ↑ Defense Act of April 21, 1935, Paragraph 1, Paragraph.

- ^ D'Ann Campbell: Women in Combat: The World War Two Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union. In: Journal of Military History (April 1993), 57, pp. 301-323.

- ↑ Order No. 41/90 of the Minister for Disarmament and Defense on the termination of the service of female members of the NVA from September 7, 1990, source No. BA-MA, DVW 1/44497, Hans Ehlert (Ed.): Army without Future. The end of the NVA and German unity . Ch. Links Verlag , Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86153-265-4 , p. 483 .

- ^ Judgment of the ECJ in case C-285/98

- ↑ a b Federal Ministry of Defense: Bundeswehr personnel figures . July 2020, accessed on July 30, 2020 (as of June 2020).

- ^ Federal Ministry of Defense: Bundeswehr personnel figures . July 2020, accessed on July 30, 2020 (as of June 2020).

- ↑ bundestag.de on January 18, 2012: Federal government evaluates the integration of women in the armed forces positively ( Memento from October 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Can you use the Bundeswehr? Spiegel Online , March 25, 2014, accessed September 3, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Journée de la femme: "Femmes présence indispensable". French Armed Forces , March 8, 2011, accessed December 7, 2015 (French).

- ^ Jürgen König: Election campaign with the reintroduction of compulsory military service. Deutschlandfunk , August 24, 2016, accessed on September 23, 2017 .

- ↑ Defense: The French Way to the Professional Army. French Embassy in Berlin , December 11, 2015, accessed on September 23, 2017 .

- ^ Women in the Armed Forces. History of Women in the British Armed Forces. (No longer available online.) 2006, archived from the original on June 7, 2011 ; accessed on June 12, 2013 .

- ↑ http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4687095,00.html

- ↑ http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/jpost/doc/319488656.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jul%2015,%202005&author=ARIEH%20O%27SULLIVAN&pub=Jerusalem%20Post&edition=&start . = & desc = Coed% 20combat

- ^ A b Israel Defense Forces : More female soldiers in more positions in the IDF. December 30, 2011, accessed January 15, 2012 .

- ^ Compulsory military service. (No longer available online.) Norwegian Armed Forces , January 16, 2012, archived from the original on November 5, 2013 ; accessed on April 27, 2013 (English).

- ↑ a b Norway introduces conscription for women. DiePresse.com , June 14, 2013, accessed June 16, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Marie Melgård, Karen Tjernshaugen: Stortinget vedtar verneplikt for kvinner 14 June . In: Aftenposten . April 21, 2013, ISSN 0804-3116 (Norwegian, online [accessed April 27, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Norwegian women opposed to gender-neutral military service. The Norway Post, April 23, 2013, accessed April 27, 2013 .

- ↑ Article 9a, Paragraph 3 of the Federal Constitutional Law “Every male citizen is obliged to serve. Citizens can voluntarily serve in the armed forces as soldiers and have the right to terminate this service. "

- ↑ a b c Same fitness assessment for men and women. (No longer available online.) Swiss Army , 2007, archived from the original on January 28, 2016 ; Retrieved on December 3, 2011 (TFR = Test Fitness Recruiting): "Since women in all branches of service have to meet the same minimum physical requirements as men, they are now also assessed the same way at TFR."

- ↑ a b Review of physical performance. (PDF; 252 kB) Heerespersonalamt, p. 1f , accessed on December 4, 2015 .

- ↑ a b Physical and mental fitness as a prerequisite. (No longer available online.) Federal Army , archived from the original on April 12, 2016 ; Retrieved December 21, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Report: Working worlds: Army not attractive for women. In: The Standard . March 6, 2010, accessed December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Symposium "WoMen serving together". Federal Armed Forces , October 12, 2011, accessed on November 13, 2011 : "Currently, almost 400 women are serving in the Armed Forces, that is just under two percent, a percentage that needs to be increased, according to the consensus on the podium."

- ↑ 949 of Beilagen XXII. GP - Government Bill - Materials. (PDF; 280 kB) Austrian Parliament , May 17, 2005, p. 7 , accessed on November 14, 2011 .

- ↑ Oliver Mark: Women in the Army: Long march through the minefield. derStandard.at , November 9, 2011, accessed on November 9, 2011 : “ derStandard.at: The armed forces have been open to women for 13 years. Why didn't you manage to make your job more attractive during this time? Moosmaier: Only in the last few years have more measures been taken. This year, for example, there were invitations to 480,000 young women as part of “Girl's Day”. 528 were with us for a day to try things out, which ultimately resulted in 50 new registrations for the training service. "

- ↑ Federal Ministry for National Defense and Sport (BMLVS): 6.4 Civilian employees. (PDF) In: Weissbuch '10. 2011, accessed December 21, 2011 (Female Officials, Contract Agents and Apprentices).

- ^ M. Ney Krwawicz, Women Soldiers of the Polish Home Army. Retrieved July 20, 2020 .

- ^ Department of Kadr MON. (No longer available online.) Polish Armed Forces , 2009, archived from the original on January 4, 2009 ; Retrieved June 12, 2013 (Polish).

- ↑ a b c statistics. (PDF; 2.4 MB) Swedish Armed Forces , accessed June 12, 2013 (Swedish).

- ^ The Swedish Armed Forces. In: www2.mil.se/sv/. Swedish Forces, 2013, accessed August 31, 2013 (Swedish).

- ↑ Om Försvarsmakten. (No longer available online.) Swedish Armed Forces , archived from the original on June 17, 2008 ; Retrieved June 12, 2013 (Swedish).

- ↑ Felix Römer: Violent gender order. Wehrmacht and "Flintenweiber" on the Eastern Front 1941/42, in: Soldatinnen. Violence and gender in war from the Middle Ages to the present day (Ed .: Franka Maubach, Silke Satjukow, Klaus Latzel). War in History 60, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2011, pp. 331–351

- ↑ a b c d e f NATO : Percentages of female Soldiers in NATO countries' Armed Forces (2001–2005). (PDF: 80 kB; 4 pages) In: NATO.int. July 13, 2006, p. 1 , accessed December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ NATO -Report 2014: Summary of the National Reports of NATO Member and Partner Nations, 2014. NATO HQ, Office of the Gender Advisor, International Military Staff, March 7, 2016 (English; PDF: 6.3 MB, 143 pages on nato.int ).

- ↑ Today's Women Soldiers. United States Army , accessed May 25, 2013 .

- ^ Dietrich Alexander: First US soldier becomes four-star general. In: The world . June 24, 2008, accessed December 12, 2019.

- ↑ NDMS: New Debate on Submarine Duty for Women. (No longer available online.) In: ArmedForcesCareers.com. 1999, archived from the original on September 27, 2007 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ^ Ann Scott Tyson: For Female GIs, Combat Is a Fact. The Washington Post , May 13, 2005, accessed May 25, 2013 .

- ^ Philip Gold, Erin Solaro: Facts about women in combat elude the right. Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 17, 2005, accessed May 25, 2013 .

- ^ Women on the military frontline. BBC News , March 29, 2007, accessed May 25, 2013 .

- ↑ http://www.stripes.com/news/marine-corps-to-create-experimental-task-force-with-25-percent-women-1.272610

- ↑ Lolita Baldor: A female Navy Seal? Not yet. (No longer available online.) The Washington Post , June 1, 2011, archived from the original on September 26, 2017 ; accessed on May 25, 2013 .

- ↑ Key indicator method for activities such as pulling, pushing. EU-OSHA , accessed November 6, 2013 .

- ↑ State Committee for Occupational Safety and Health (Ed.): Instructions for the assessment of working conditions when pulling and pushing loads . LV 29. Saarbrücken 2002, ISBN 3-936415-25-0 , p. 21 ( PDF; 1.7 MB [accessed December 8, 2015]).

- ↑ Josef Kerschhagl: Appendix 3: Basics - manual load handling . Ed .: Central Labor Inspectorate. Vienna July 24, 2001, p. 11 ( PDF: 695 kB, 23 pages at Arbeitsinspektion.gv.at ( Memento from September 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) [accessed on May 25, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Stephan Maninger: Helena Carreiras, Gerhard Kümmel : Women in the Military and in Armed Conflict (= series of publications by the Social Science Institute of the Bundeswehr . Volume 6 ). 1st edition. Springer VS , Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15834-1 , Women in Combat: Reconsidering the Case Against the Deployment of Women in Combat-Support and Combat Units, p. 9–27 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Physical problems: British Army corrects stride length for female soldiers. Spiegel Online , November 24, 2013, accessed November 25, 2013 .

- ↑ Mark Nichol: Female RAF recruits get £ 100,000 compensation each ... because they were made to march like men. Daily Mail , November 23, 2013, accessed November 25, 2013 .

- ↑ US Marines suspend pull-up tests for female soldiers. derStandard.at , January 3, 2014, accessed on January 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Barbara Boland: Female Marines Not Required To Do 1 Pull-Up. cnsnews.com, December 27, 2013, accessed January 6, 2014 .

- ^ Edward N. Luttwak: "Men moved to protect the women members of the unit instead of carrying out the mission of the unit."

- ↑ Michael Borgstede: Middle East: Because of hard - Israel and its soldiers. In: welt.de . July 13, 2008, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ http://www.idf.il/1086-14000-EN/Dover.aspx

- ↑ Laura Réthy: Bundeswehr survey: Every second soldier does not want women in the force. In: welt.de . January 24, 2014, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Gerhard Kümmel: Troop image without a lady? Status of integration of women in the Bundeswehr. ZMSBw, 2014, accessed in 2020 .

- ^ Marine Corps Force Integration. Marines, 2020, accessed 2020 .

- ↑ Facebook, Twitter, Show more sharing options, Facebook, Twitter: Marine Corps study says units with women fall short on combat skills. September 12, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-female-veteran-suicide-20150608-story.html

- ↑ https://www.tuwien.ac.at/aktuelles/news_detail/article/6531/

- ↑ https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2394531/marine-corps-force-integration-plan-summary.pdf "During the GCEITF assessment, musculoskeletal injury rates were 40.5% for females, compared to 18.8% for males"

- ^ William Herbert: Effect of Isokinetic Strength Training and Deconditioning on Bone Stiffness, Bone Density and Bone Turnover in Military-Aged Women . In: Defense Technical Information Center . June 2001 ( PDF [accessed February 11, 2013]).

- ↑ Alana D. Cline, G. Richard Jansen, Christopher L. Melby: Stress Fractures in Female Army Recruits: Implications of Bone Density, Calcium Intake, and Exercise . In: Journal of the American College of Nutrition . Vol. 17, No. 2 , April 1998, pp. 128–135 ( full text on jacn.org ( memento of February 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Catriona Davies: Sex equality is the first casualty of war . In: The Daily Telegraph . September 2, 2005, ISSN 0307-1235 ( online [accessed May 29, 2013]): "Girls get injured more often than the boys and take longer to recover. Pelvic fractures are common among the girls because they are often smaller but try to keep up with the boys' stride pattern. We are going to train the girls separately for a three-year trial. We believe we can't quite reduce the injury rate to one-to-one but that we can cut wastage among the girls. "

- ↑ Sherman RA, Davis GD, Wong MF: Behavioral treatment of exercise-induced urinary incontinence amongst female soldiers . In: Military Medicine . Vol. 162, No. 10 , October 1997, p. 690-694 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m SADC Gender Protocol. 2015 barometer. books.google.de . In addition to troops, these figures also include civilian personnel in the armed forces.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o NATO table: Percentages of female Soldiers in NATO nations' Armed Forces (2007). (PDF: 18 kB; 1 page) (No longer available online.) In: NATO.int. September 12, 2007, archived from the original on September 14, 2007 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ^ Rutgers Institute for Women's Leadership: Women in the US Military Services. (PDF: 243 kB; 3 pages) (No longer available online.) In: Rutgers.edu. 2010, archived from the original on December 8, 2012 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c United Nations Development Program (UNDP): UNDP helps Ukrainian Ministry of Defense create new opportunities for women. (No longer available online.) In: UNDP.org.ua. June 16, 2009, archived from the original on February 26, 2012 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ^ Parliament of Australia: Women in the ADF. (No longer available online.) In: APH.gov.au. December 22, 2000, archived from the original on February 7, 2012 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Bundeswehr: Central instruction B1-224 / 0-2: Training and maintenance of individual basic skills and physical performance (training IGF / KLF). (PDF: 822 kB; 34 pages) (No longer available online.) In: Reservistenverband.de. May 21, 2015, p. 24 , archived from the original on October 15, 2018 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ^ Ministry of Defense, UK : History of Women in the British Armed Forces. (No longer available online.) In: MOD.uk. February 2006, archived from the original on June 7, 2006 ; accessed on December 12, 2019 .

- ^ André Anwar: Foreign Policy: Norway's women have to move into the barracks. In: DiePresse.com. August 3, 2016, accessed December 12, 2019 .

-

↑

Inquiry response on the proportion of women in the armed forces:

Austrian Parliament : Inquiry response 6901 / AB. (PDF; 513 kB; 4 pages) In: Parlament.gv.at. January 22, 2016, accessed December 12, 2019 .

Question: Austrian Parliament: Parliamentary Question 7101 / J XXV. GP. (PDF: 85 kB; 2 pages) In: Parlament.gv.at. November 23, 2015, accessed December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Army Personnel Office: Review of physical performance. (PDF: 252 kB; 3 pages) In: Bundesheer.at. November 27, 2012, p. 1/2 , accessed December 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Defense and Sport (BMLVS): 6.4: Civilian employees. (PDF: 4.7 MB; 128 pages) In: Weissbuch '10. 2011, accessed December 12, 2019 .