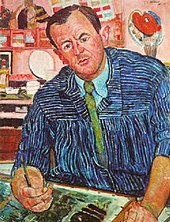

George grosz

George Grosz (born July 26, 1893 as Georg Ehrenfried Groß in Berlin ; † July 6, 1959 there ) was a German - American painter , graphic artist , caricaturist and opponent of the war. George Grosz's socially and socially critical paintings and drawings of Verism , most of which were created in the 1920s, are assigned to the New Objectivity . These works are characterized by sometimes drastic and provocative representations and often by political statements. But his work also has expressionist , dadaist and futuristic traits. Typical subjects are the big city, its absurdities (murder, perversion, violence) and the class contradictions that show up in it. In his works, often caricatures, he mocks the ruling circles of the Weimar Republic , takes up social differences and criticizes in particular the economy, politics, the military and the clergy.

life and work

Childhood and youth

Grosz was born in 1893 as the son of the innkeeper Karl Ehrenfried Groß and his wife Marie Wilhelmine Luise, nee. Schultze, born in Berlin. In 1898 the family moved to Stolp in Pomerania. After the father's death in 1900, the mother moved with him back to Berlin for a short time, but in 1902 he returned to Stolp, where the mother took over the management of an officers' mess.

Grosz attended secondary school there until 1908, where he was supported by his art teacher. As a child he copied drawings from magazines and read adventure and detective stories with enthusiasm. He was particularly interested in images depicting dramatic scenes. “The horror panorama paintings at the fairs and shooting festivals made an indelible impression on me.” In his autobiography A Small Yes and a Big No , he continues to describe the conditions at school that he perceived as harassing and violent. After he had returned the favor to a trainee lawyer with a slap in the face, he had to leave school.

At the Royal Saxon School of Applied Arts in Dresden , which he was allowed to attend from 1909 after arguments with his mother, he said he did not learn anything useful. “Our main work was the reproduction of plaster casts in their original size.” However, he made the acquaintance of Otto Dix .

After graduating, he went to Berlin in 1912 and studied at the arts and crafts school with a state scholarship; he was a student of Emil Orlik there . Berlin was the center of progressive art and culture. In addition to Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh , modern artists such as Pablo Picasso , Henri Matisse and André Derain were shown in the art dealerships . Grosz not only visited exhibitions, but also fairgrounds and other amusement venues, where he made sketches. He drew for "Witzblätter", but also at the same time from nature in the arts and crafts school. In the spring of 1913 he went to Paris for the first time for eight months, where he studied the Parisian atmosphere and people. He took life drawing lessons in the Colarossi studio . Japanese woodcuts , caricatures, especially from Simplicissimus, and the realists Honoré Daumier and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are considered important sources of influence during this period . In 1914 he received the second prize from the educational establishment of the Museum of Applied Arts of the Royal Museums.

Influence of the First World War on his work

After the beginning of the First World War , Grosz volunteered as an infantryman in the army in November 1914 in order to avoid the front-line deployment, which is usually associated with compulsory conscription. He was dismissed as unfit for service in May 1915. “For me, war was horror, mutilation and annihilation.” As a strict opponent of war, like his friend, the artist John Heartfield , formerly Helmut Herzfeld, he no longer wanted to bear a German name. Therefore he called himself George Grosz since 1916 . By choosing an English name, he wanted to set an example against the patriotically heated anti-English mood in the Empire; there was also a certain enthusiasm for America. Grosz drew many critical war scenes during this time.

“I drew soldiers without a nose, war cripples with cancerous steel arms […] A colonel who, with his trousers unbuttoned, hugged a fat nurse. A hospital assistant who pours all kinds of human body parts from a bucket into a pit. A skeleton in recruit gear that is being examined for military suitability. "

Grosz described himself as a “modern battle painter” and had also obtained images of works by the classic battle painter Emil Hünten for study purposes . Franz Pfemfert , editor of the left expressionist weekly Die Aktion , published a drawing and a poem by George Grosz in July and November 1915.

Grosz's level of fame rose further in 1916 through the publication of three full-page drawings in the newly published magazine Neue Jugend (called "Heft Sieben" under military censorship) and an article about him by Theodor Däubler in Die Weiße Blätter , one of the most important journals of literary expressionism. He came into contact with art patrons , including Harry Graf Kessler and later Felix Weil . In retrospect he wrote self-critically that the work of art had become a commodity, and in 1916 he temporarily played the role of an ambitious artist towards the patron, flattering himself depending on what the respective person wanted to see and hear.

In 1917 Grosz was finally drafted. According to his own statement, he was supposed to be shot as a deserter and was only saved by the intervention of Count Harry Kessler. He was transferred to a mental hospital and released on May 20 as "unusable". He went back to Berlin and plunged into big city life there. In 1917 he completed his early major work “Metropolis”. It describes the city as unleashed chaos - diverging streets, people wandering aimlessly, an apocalyptic hubbub around the Central-Hotel at Friedrichstrasse station, everything soaked in blood-red paint. The painting hangs today in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. The oil painting Dedication to Oskar Panizza (1918) in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart is in a similar style .

Dadaism

Grosz was, together with John Heartfield and Wieland Herzfelde , the founder of the Berlin Dada scene. Together with Richard Huelsenbeck , the Swiss Dada initiator, he organized the first Dada evenings in 1917 in the Berlin Secession on Kurfürstendamm. During the First World War, Dadaism had spread across Europe. Through targeted provocations and alleged illogic, artists everywhere protested against the war and the bourgeoisie and artists who think in terms of authority. They contrasted the enthusiasm for war with pacifist positions and led the previously prevailing bourgeois values into the absurd. Meetings were held for an entrance fee, at which the audience was sometimes rude insulted for their money. There were frequent fights and the police were present. Artistic actions were partly improvised. One of the catchphrases was: “Dada is pointless.” The members accepted functional titles, so Grosz became “Propagandada”. In 1920 he helped organize the First International Dada Fair in Berlin and exhibited there. There he exhibited the surrealist painting A Victim of Society , a collage on canvas. Under the later title Remember Uncle August, the Unhappy Inventor , it hangs today in the Center Georges-Pompidou . In this phase he also took on the artistic influences of Cubism and Fauvism .

Politically oriented work

In 1919, under the influence of the November Revolution, he became a member of the KPD and the November Group and put his art at the service of the proletariat: artists had the task of participating in the struggle for freedom. Compared to his early Dadaist works, the subject changed from pub, street and city scenes to bitterly angry depiction of the political opponent. During this time he created his great political picture Germany, named after Heinrich Heine 's epic verse of the same name , a winter fairy tale : In the middle a staid reserve officer as a typical German philistine with roast pork, beer and the local gazette. Below three “pillars of society”: priest, general, professor. The world wavers around the citizen, a sailor serves as a symbol for the revolution. In addition, there is a prostitute, everything a reflection of the time in which the entire value system seemed to fall apart. A silhouette of Grosz himself at the bottom left. This picture was also one of the highlights of the First International Dada Fair in 1920. It has been lost after 1933.

He was co-founder of four politically radical journals, everyone his own football (one issue in February 1919), The bust (1919-1924), the opponent (1919-1924) and The bloody Ernst (1919), in the Malik-Verlag published were. Until 1930, Grosz illustrated for papers on the far left, including the KPD's satirical magazines, Eulenspiegel and Roter Pfeffer . He also drew for The Porcupine (1925 to 1928), edited by Hans Reimann , and the Simplicissimus (1926 to 1932). The publications in cross-section from 1922, the sheet of the gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim , contributed to his growing popularity .

He never limited himself to a purely party-political satire. In addition to his explicitly political work, he continued to draw late Dadaist and (only) socially critical illustrations. Among them are the lithographs - drawings, vignettes, initials and endpapers - for Alphonse Daudet's The Wondrous Adventures of Tartarin of Tarascon . He also illustrated many other literary works, including a. to Heinrich Mann , Walter Mehring and Upton Sinclair . In addition, from 1929 onwards, entirely non-political articles appeared for the Ulk supplement of the Berliner Tageblatt .

Further life in Berlin

He had his first solo exhibition in 1920 at the New Art Gallery in Munich , which was led by Hans Goltz , a pioneer of modern art. As early as 1918 he had signed an exclusive agency contract with him, which he renewed in 1920. In 1922, when he first supplied drawings to the Düsseldorf art dealer and patron Alfred Flechtheim for the magazine Der Cross , he terminated his contract with Hans Goltz. In the same year, on May 26, 1920, he married Eva Louise Peter and moved with her to the Berlin district of Wilmersdorf . Grosz lived in this area with his family until January 1933, when he moved to the USA. They have the sons Peter (* 1926) and Martin, called Marty (* 1930). In 1922 Grosz undertook a five-month trip with Maxim Gorky to the Soviet Union because of a book project , during which he also had an audience with Lenin and visited Trotsky . Under these impressions he left the KPD because he rejected any form of authoritarianism and dictatorship and criticized the economic conditions for the broad masses of the people, but remained true to his views. In 1923, Alfred Flechtheim became the art dealer of George Grosz, who exhibited regularly in his galleries in Düsseldorf and Berlin and thus also earned a regular income. From 1924 to 1925 and again in 1927 he traveled to France. There he created works of art such as portraits and landscapes , also to earn a living . In 1924 he exhibited in Paris. In 1925 he took up oil painting again with a portrait of the writer Max Herrmann-Neiße - one of the main attractions of the Mannheim exhibition New Objectivity in the same year. The city art gallery in Mannheim acquired it. In 1926 he completed another of his main works: Supporting Society . With the title he alludes to Henrik Ibsen 's drama of the same name. In this allegory of German society in the Weimar Republic, he caricatures three representative types: a lawyer, with a hat and a monocle, recognizable as a corps brother riding eternally eastward, no blindfold like Justitia, but without ears; a journalist, recognizable to his contemporaries as press czar Alfred Hugenberg , helmeted with the proverbial chamber pot as an expression of his restricted posture, newspapers under his arm and hypocritically a palm frond in his hand; a Social Democratic MP, the pamphlet “Socialism is work”, the SPD's slogan at the time, under his arm and the shit he kept steaming in his head, and a schnapps-nosed military chaplain who preached peace while behind his back already murder and manslaughter rule by Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten and Wehrwolf (Wehrverband) . Today it can be viewed in the National Gallery in Berlin . In the same year he also made the oil painting Solar Eclipse : Hindenburg is sitting at the conference table, in the other seats headless cabinet members, and from behind a representative of big business blows him the slogans. Meanwhile, the people in the shape of a donkey devour the lying press products. Since 1968 the picture has been hanging in Huntington, New York, Collection of the Heckscher Museum of Art; he had originally sold it in his Huntington township to pay a car bill; today it is the most valuable picture in the collection. Both pictures move in the style of the new synthetic realism , as Heinrich Vogeler developed it in his complex pictures . In 1927 the Prussian Academy of the Arts dedicated a special exhibition to Georg Grosz. In 1928 he was awarded a gold medal for his portrait of Max Schmeling at the art show on the occasion of the Olympic Games in Amsterdam ; in Düsseldorf he received the gold medal for German art . George Grosz took part in 1929 as a full member of the German Association of Artists in the DKB annual exhibition in the Cologne State House on Rheinpark with Berlin at Night and The Music Clown Herbert Williams . At the end of 1931, Alfred Flechtheim was forced to terminate his contract with Grosz, probably due to his economic situation, which was very tense due to the global economic crisis and the increasing number of racist attacks on his galleries; Grosz himself did not want to take him back in 1932 in order to maintain his economic flexibility.

Theater and stage design

With Fritz Mehring and John Heartfield, Grosz organized a political puppet show in the cabaret Schall und Rauch in 1920 , to which he contributed the puppet designs, and together with John Heartfield developed sets and costumes for George Bernard Shaw's play Caesar and Cleopatra . This was followed up in 1930 a number of stage sets for theaters in Berlin, including the proletarian theater of Erwin Piscator , the Volksbühne and the German Theater . He achieved groundbreaking innovations with the premiere of Paul Zech's The Drunk Ship and, above all, with the world premiere of the stage version of Jaroslav Hasek's novel The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk in 1928 on the adventurous Piscator stage on Nollendorfplatz. He introduced cinematic effects and projections, and a double treadmill with life-size figures based on drawings by Grosz was used. In 1930 he designed the sets and figurines for the first performance of Arnold Zweig's play The dispute over Sergeant Grischa in the Theater am Nollendorfplatz (guest performance by the German Theater under the direction of Max Reinhardt ).

Portfolios

At an early stage Georg Grosz contrasted the type of "easel painter" with that of the journalistic draftsman, who he felt was more contemporary and modern. The political intentions of many of his works also called for popularization and wider dissemination. In his friendship with the publisher Wieland Herzfelde , he found the conditions for this in cooperation with Malik-Verlag , just as, conversely, his work and the photo montages by John Heartfield represented the artistic framework of the publisher. From 1917 to 1928 he published six graphic portfolios there, an anthology with original graphic claims and also illustrated numerous books. As early as 1916, the first George Grosz portfolio was published by the Berlin printer Hermann Birkholz, who also printed for the Malik Verlag, founded in 1917. In 1920 the portfolio God with us was published , an account of German militarism that was exhibited at the First International Dada Fair . Images from it were included in the volume The Face of the Ruling Class in 1921 . In 1921 the portfolio Im Schatten appeared , followed by Die Räuber the following year . The first portfolio of the two shows the oppressed and pauperized proletariat, the second a cynical psychogram of the upper class. There were cheaper expenses for trade union organizations. In 1922/23 Malik-Verlag published a comprehensive collection: Ecce Homo . 16 colored watercolors and 84 black and white drawings were combined in a portfolio or as a bound book edition to provide an overview of the oeuvre from 1915 to 1922. Grosz's wife Eva and Wieland Herzfelde put together the portfolio thematically, not chronologically. It is a furious succession of types and scenes that symbolize the decline of society: angular, dull military skulls, decadent upper-class bohemians, lustful financial magnates, half-naked prostitutes, lust killers after a deed - a merciless cross-section, above all of higher society like them represented him. In 1925 the folder Der Spiesser-Spiegel was published with 60 drawings, and in 1928 the folder Background , which contains 17 drawings from the animated film for the Schwejk performance.

In America, Grosz published the first portfolio Interregnum in 1936 with 64 drawings from the years 1927–1936 and a color lithograph ( The Muckraker ). With her, however, he could not build on the success of Ecce Homo . One reason for this could have been the high price of $ 50 and the low circulation of 300 copies, but also that his depictions did not position himself in a partisan way (left), like the majority of intellectuals, but instead attacked fascism and communism in equal measure Has. It wasn't until 1944 that it appeared with George Grosz. Drawings from him another portfolio in the USA.

Grosz's work and the judiciary

Grosz was subjected to numerous grueling court cases during the Weimar period. As early as 1921 he was sentenced to a fine of 300 marks for “insulting the Reichswehr ” on the basis of the portfolio God with us exhibited at the Dada art fair in 1920 . A fine of 600 marks was also imposed on his publisher Wieland Herzfelde by Malik-Verlag. A captain of the Reichswehr had filed the complaint because he had found the Dada exhibition in general and Georg Grosz's portfolio in particular as systematic agitation and despicable denigration.

In 1923 another trial was opened for "attacking public morality" under Section 184 of the Criminal Code, the fornication section. Seven color and 27 black-and-white images from Ecce Homo were confiscated in April and charges were brought in December for the distribution of indecent writings. In 1924 Georg Grosz, Wieland Herzfelde and Julian Gumperz were sentenced to a fine of 500 marks each. Five watercolors and 17 drawings had to be removed from the portfolio; the corresponding plates and molds should also be made unusable. The positive oral statements of the invited experts, including the Reichskunstwart Edwin Redslob , and the written report by Max Liebermann could not change anything. The decisive factor for the judges was “the sense of shame of normal people”.

The folder Der Spiesser-Spiegel was also very controversial, but no complaint was made. However, this happened thirty years later, in 1955 when the Arani publishing house was reissued. The public prosecutor's office examined a public nuisance, but then took the view that the papers could "not necessarily be regarded as lewd, it was a borderline case" and dropped the case.

From 1927 to 1932 Grosz had to face five legal disputes, including one charge of blasphemy ; in addition, there was a follow-up process and negotiations about the confiscation and rendering unusable of the incriminated drawings. The occasion was the drawing shut up and continue to serve , which depicts Christ on the cross with a gas mask. It had previously been shown in the stage set under the background projections during the production of the play The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk by Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht in Berlin in 1927 and published by Grosz with two further drawings in the portfolio entitled Background . The blasphemy charge ended in 1931 with an acquittal. The "Grosz case" was dealt with in two sessions of the Reichstag and five sessions of the Prussian state parliament. Numerous artistic and political associations expressed solidarity with the defendants publicly and through letters to the courts. Journalists from party and church papers, art and literary magazines dealt with it all over Europe. Even the Quaker denomination appeared as a reviewer in this process for the only time in its history. The positive opinion is remarkable, as the Quakers have a rather skeptical relationship to art. Grosz, however, attested that the picture had an inflammatory and moving visual effect and denied the existence of a clear boundary between artistic and religious intuition.

Concept of art

In his essay, Instead of a Biography , first published in 1921, Grosz takes a critical look at the contemporary concept and business of art. Art is referred to as a “banknote factory” and “stock machine” for “aesthetic fools” depending on the bourgeois class. It also serves as the “escape [...] into a purer paradise without party and civil war.” The artist mostly comes from the lower classes and has to adapt to the “bigwigs”. Either he receives monthly money from a patron or he falls for the art dealer who sells the latest fashions. As the “creator” he believes he is high above the “banausen” who laugh at the pictures by Picasso and Derain , but only creates supposed profundity, far removed from any reality. He also rejects abstract art and expressionism . He bitingly deals with the “individualistic” artists: “Are you working for the proletariat , who will be the bearers of the coming culture? [...] Your brushes and pens, which should be weapons, are empty straws. ”He himself takes the side of the“ oppressed ”and wants to“ show the real faces of their masters ”, in a visual language that everyone can understand. At the beginning of the 1930s, Grosz was one of the most notorious artists in Germany and the most sought-after illustrator. His name was closely linked to the cultural and artistic modernity of the Weimar Republic. He was considered a "communist" artist; his works were bought by museums and shown in numerous exhibitions, some of which were aimed at workers. He and his family were the subject of reports in numerous magazines, feature sections advertised his opinion, and bourgeois magazines adopted his more harmless drawings from clowns, jazz musicians and farmers. Futurism , Cubism and New Objectivity - his work included essential parts of Classical Modernism . Against this background, in 1931 he reaffirmed his view of contemporary art as part of the bourgeois, capitalist fraud that upholds the status of the ruling class and surrenders artists to the mercy of the art dealers.

Relocation to the USA and late work

From June to October 1932 Grosz was given a teaching position for the Art Students League of New York . He accepted it, also because of his worsened financial situation, and taught a nude class. He decided to leave Germany for good and emigrated to the USA on January 12, 1933; his children followed in October. Immediately after the seizure of power at the end of January, his studio was stormed, possibly to be found in his apartment. As early as March 8, 1933, nine days after the Reichstag fire, George Grosz was expatriated as the first and initially only of 553 public figures who were immediately recorded. His works that remained in Germany fell into the hands of the National Socialists, who confiscated them as “ Degenerate Art ”, sold them off cheaply abroad or destroyed them. Of 170 works from the Berlin period, around 70 have been lost, over 50 of which he had sent over the years to his gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim, who himself had to flee at the end of May 1933 and close down his gallery.

In 2003, the Grosz family sued the Museum of Modern Art and the Bremen Kunsthalle, accusing them of having illegally appropriated paintings, including the MoMA because of the second portrait "Max Hermann-Neisse (1927). The museum responded to the defense Limitation period back; the picture hangs in the Museum of Modern Art to this day, as does “The Painter and His Model.” The same applies to two pictures in the Bremen Kunsthalle, “Stilleben mit Okarina” (1931) and “Pompe funèbre” (1925 ), and several other works in other museums.

In America, Grosz first lived in Bayside, New York, and from 1947 in Huntington, New York, in a house he bought in 1952. He created around 280 paintings in the United States. In addition to around 100 nudes, he also painted Images of Hell, a series of apocalyptic scenes and war images, which he began in 1937 under the influence of the Spanish Civil War and which he passionately continued in view of the destructive violence of German National Socialism. He was disillusioned that the “proletarian masses” had not defended themselves against Hitler in 1933 , horrified by the murder of Erich Mühsam, whom he valued, and stunned by the reports of emigrants who had escaped from the concentration camps. An outstanding example of these pictures is Cain, or Hitler in Hell (1944, Gallery David Nolan, New York): an oversized Adolf Hitler sits on a rock in front of a gloomy war inferno, amid a pile of small skeletons. After the end of the war, a number of disturbing images under the impression of the atomic threat should be included in this series.

Compared to many other German emigrants, Grosz was also successful in America, both in terms of the sale of his pictures and through his almost continuous, if increasingly unpopular, teaching activity at the Art Students League of New York, which ensured his material existence. After a four-year hiatus, he took it up again in 1949. He had regular exhibitions - three in his year of arrival alone - and published drawings, e.g. B. in the satirical magazine Americana , the Vanity Fair and the Life . In 1945 he won the 2nd prize in the Painting in the United States exhibition at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in 1945 with the painting The Survivor (1944). However, this could not stand up to the comparison to his controversial but very high reputation in Germany. In the USA he was largely perceived as a German artist and with his works did not achieve the level of recognition and analytical sharpness of representation as in Germany. His romantic view of America and his status as a guest citizen would not have allowed that at all at first, even if both changed over time. After the end of the war in 1945, his late work became increasingly decorative and apolitical. He sometimes painted delicate, harmonious watercolors, still lifes , nudes and landscapes that no longer achieved the fame of his early work. He himself described his late work as more artistic compared to his earlier known political works, and referred to a return to the old masters. Grosz was elected an Associate Member (ANA) of the National Academy of Design in New York in 1950 .

In 1954 he was elected a member of the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Letters and received its Gold Medal for Graphic Arts in 1959.

In June 1938, Grosz became an American citizen. In 1946 his autobiography A little yes, and a big no was published, which only appeared in German in 1955 with the title Ein kleine Ja und ein große Nein . In this book his deep conflict becomes clear; it is written in a tone of semi-ironic bitterness. He is no longer openly committed to his early, politically and culturally aggressive work, but makes a clear cut between the two phases of life. For example, he describes the Dada movement rather half-heartedly, which he denies any aesthetics and which he describes as the "art (or philosophy) of the garbage can". However, this did not prevent him from making a 40-page series of Dadaist collages shortly before his return to Germany in 1957. He stood by his contradictions and defended them with the verses of Walt Whitman : I contain multiplicity; why shouldn't I contradict myself? He suffered from depression and was increasingly prone to alcoholism.

After Grosz was appointed a member of the West Berlin Academy of the Arts in post-war Germany , he returned to Germany in 1959 at the insistence of his wife Eva. Only a few weeks later, at almost 66 years of age, he died on July 6th in Berlin, the city of his birth, after falling down stairs as a result of being drunk.

The burial took place on July 10, 1959 in the Heerstraße cemetery in today's Berlin-Westend district. Eva Grosz was buried next to her husband three years later. By resolution of the Berlin Senate , the final resting place of George Grosz (grave location: 16-B-19) has been dedicated as an honorary grave of the State of Berlin since 1960 . The dedication was last extended in 2016 by the now usual period of twenty years.

The son Peter Michael Grosz , an internationally recognized aviation historian, died in September 2006. The son Marty is still one of the most famous musicians of classical jazz in the USA.

George Grosz's estate is cared for by the Houghton Library at Harvard University and the archive of the Berlin Academy of the Arts.

During his time, George Grosz's work had a strong influence on other representatives of the New Objectivity in Germany and painters of social realism in the USA; His students in the USA in 1955 included James Rosenquist and Jackson Pollock . To this day he is an important role model for political cartoonists and illustrators; his work was and is still shaping the socio-political image of the Weimar Republic. George-Grosz-Platz on Berlin's Kurfürstendamm was named after him in 1996 and was completely renovated in 2010. A mosaic board with his signature was embedded in the floor and an information column was installed.

As part of the series “ German Painting of the 20th Century ”, the Deutsche Bundespost issued a 100-Pfennig special postage stamp with the motif In the Cafe in 1993 .

Works (selection)

Oil paintings, watercolors, collages

- 1914 Pandaemonium , Indian ink, pen. Privately owned

- 1915 riot of the mad , ink, pen, art library, SMPK, Berlin

- 1915/16 Memory of New York , lithograph, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart , Graphic Collection, Stuttgart

- 1916 suicide , Tate Gallery , London

- 1916 The Lovesick , Art Collection North Rhine-Westphalia , Düsseldorf

- 1916/17 Big City , Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Lugano

- 1916/17 lust murder in the Ackerstrasse , offset printing, art library, SMPK, Berlin

- 1916/1917 Metropolis , Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum , Madrid. Oil on canvas (100 × 102 cm)

- 1917 Explosion , The Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1917/18 Dedication to Oskar Panizza , Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart (before Heinrich Kirchhoff collection )

- 1917/19 "Germany, a winter fairy tale". Whereabouts unknown.

- Watercolor as a sketch for the picture 1918: 2010 discovered from the legacy of gallery owner Hans Koch in 2010

- 1918 John the Woman Killer , Hamburger Kunsthalle , Hamburg.

- 1918 The girl dealer , Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt , watercolor, reed pen and ink.

- 1918 parasites (Fischer, 1966, no.20).

- 1919 Beauty, I want to praise you , Galerie Nierendorf , Berlin, watercolor, pen and ink.

- 1919 A Victim of Society , Collage, Estate of GG

- 1920 Untitled , Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf ( online on the museum's website ).

- 1920 Republican automata , watercolor, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- 1920 Daum marries her pedantic automation George in May 1920, John Heartfield is very glad of it , watercolor, collage, Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin.

- 1920 Orgy , watercolor, pen and ink, watercolor, pen, ink, Galerie Pels-Leusden, Berlin.

- 1921 Gray Day , National Gallery, Berlin.

- 1922 Methusela , watercolor, Indian ink, bronze paint. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Around 1923 In the prime of life , watercolor, Sprengel Museum Hannover .

- 1924 She only cleans up , pencil.

- 1925 Portrait of the writer Max Hermann-Neisse , Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim .

- 1926 The pillars of society , oil on canvas, Neue Nationalgalerie , Berlin.

- 1926 Solar eclipse , Heckscher Museum of Art , Huntington (New York).

- 1926 Portrait of Max Schmeling , Axel Springer Verlag , Berlin.

- 1926 Inside and outside , private collection.

- 1927 La Pointe rouge de Marseille (landscape), Princeton, NJ, Estate of GG

- 1927 Self-portrait as Warner , oil on canvas, Berlinische Galerie ( oneline at berlinischegalerie.de ).

- 1928 The agitator , Stedelijk Museum , Amsterdam.

- 1937 Remembering , Minneapolis Institute of Art ( online at museum website ).

- 1937 Myself and the Barroom Mirror , private property ( online at davidnolangallery.com ).

- 1937 The Muckraker ( The Mud Digger / Debunker ), Oil, Estate of George Grosz.

- 1942 I was Always Present ( The rider / I was always there ), oil on canvas, Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington (New York).

- 1943 I'm glad I came back ( I'm glad to be back ), oil on pressboard, Tempe, Arizona State University.

- 1944 Cain, or Hitler in Hell ( Kain, oder Hitler in der Hölle ), Deutsches Historisches Museum , Berlin ( online at davidnolangallery.com ).

- 1944 The Survivor ( The Survivor ), oil, private ownership.

- 1946 The Pit ( The Hellmouth / The Pit ), Wichita Art Museum, Wichita, Kansas.

- 1946 Juggernaut ( Moloch ), in the collection of the Chrysler Corporation , Detroit, in New York.

- 1946/48 Enemy of the Rainbow ( The Enemy of the Rainbow ), watercolor, private collection.

- 1947/48 Waving the Flag ( with waving flag ), watercolor, Whitney Museum of American Art , New York ( online whitney.org ).

- 1948 Uprooted, the Painter of the Hole ( Uprooted, the painter of the hole ), watercolor, Busch-Reisinger Museum , Harvard Art Museums , Cambridge, MA ( online of harvardartmuseums.org ).

- 1949 The Crucified Ham ( The Crucified ham ), oil on canvas, The Students League of New York Gallery.

- 1958 Grosz as Clown and Variety Girl ( Grosz as a clown and vaudeville Girl ), Collage, George Grosz Estate, Princeton, New Jersey.

Publications

Dada Berlin Magazines (Editor)

- Everyone has their own football , Wieland Herzfelde u. George Grosz (Ed.), 1 number, Malik-Verlag, Berlin 1919.

- The bankruptcy , Wieland Herzfelde u. George Grosz (Ed.), 11 issues in 10 issues, Berlin, Zurich, Vienna, 1919–1924 ( online at archive.org ).

- Der bloody Ernst (satirical magazine), John Höxter (Ed., No. 1 and 2), Carl Einstein (Ed., No. 3–6), George Grosz (Ed., No. 3–5, Illustrator), No. 1–6, 1919 (online at archive.org: No. 1 , No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , No. 6 ).

Book illustrations

- Wieland Herzfelde : tragic grotesques of the night - dreams. Malik Verlag, Berlin 1920.

- Richard Huelsenbeck : Fantastic prayers. Malik Verlag, Berlin 1920.

- Hermynia Zur Mühlen : What Peterchen's friends tell. Fairy tale. Malik Verlag, Berlin 1921; Reprint: Fey Verlags GmbH, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-88361-010-0 .

- Richard Huelsenbeck: Doctor Billg at the end. Kurt Wolff Verlag, Munich 1921.

- Alphonse Daudet: The Adventures of Mr. Tartarin of Tarascon. Erich Reiss Verlag, Berlin 1921.

- Alfred Richard Meyer : Lady Hamilton or Die Posen-Emma or from the maid to beefsteak à la Nelson. Fritz Gurlitt Verlag, Berlin 1923.

- Heinrich Mann : Kobes. 1925.

- Pierre Mac Orlan : Port d'eaux-mortes. With 8 original lithographs by George Grosz. Au Sans Pareil, Paris 1926.

- Hans Reimann : Saxon miniatures. With 14 drawings by George Grosz, 1928.

- Bertolt Brecht : The three soldiers. A children's book, with drawings by George Grosz, 1932.

Folders, illustrated books, essayistic texts

- First George Grosz portfolio. 9 lithographs, Barger, Berlin 1917.

- Small George Grosz portfolio. 20 lithographs, Malik, Berlin 1917.

- (Richard Huelsenbeck :) Dadaist manifesto . Flyer from 1918, signed by Grosz and others; printed in Der Zweemann , Issue 3, January 1920, pp. 15-16 ( online at The International Dada Archive , uiowa.edu ).

- "God with us". Political portfolio, 9 lithographs, Malik, Berlin 1920.

- George Grosz and John Heartfield: Der Kunstlump , in: The opponent , I, 1920, Issue 10-12, pp. 48-56 ( online at princeton.edu ); Reprinted in Schneede, The Twenties. Pp. 50-58.

- Instead of a biography , in: The opponent , II, 1920/21, booklet 3, pp. 68–70 ( online at princeton.edu ), dated August 16, 1920; at the same time in Willi Wolfradt: George Grosz. Leipzig 1921. Revised in George Grosz and Wieland Herzfelde: Art is in danger. 1925; Reprinted in Schneede, The Twenties. Pp. 61-64.

- About my new pictures , (with pictures) in: Das Kunstblatt , V, 1921, Issue 1, pp. 10–16 ( online at iaddb.org ); Reprint in Grosz: Entry ticket to my brain circus. Memories, writings, letters. Pp. 75-78.

- In the shade. 9 lithographs, Malik, Berlin 1921.

- The face of the ruling class. 55 political drawings by George Grosz, ed. Julian Gumperz, Malik, Berlin 1921 ( Small revolutionary library , No. 4).

- Man is not good - but a cattle , in: Catalog for the exhibition George Grosz , Galerie von Garvens, Hanover, April 1922; Reprinted in Schuster (ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Catalog, Berlin 1994, pp. 540-541.

- A new naturalism? A round question , in: Das Kunstblatt , VI, 1922, Issue 9, Grosz's answer on pp. 382–383 ( online at iaddb.org ); Extracts reprint of the survey in: Schneede, The Twenties. Pp. 115-124.

- With a brush and scissors. 7 Materializations, Malik, Berlin 1922.

- The robbers. Nine lithographs on sentences from Schiller's Räuber , Malik, Berlin 1922.

- Billing follows! 57 political drawings, Malik, Berlin 1923 ( Small Revolutionary Library , No. 10).

- Ecce homo. 84 lithographs and 16 watercolors, Malik, Berlin 1923; Reprint 1992.

- Processing , (with images) in: Das Kunstblatt , VIII, 1924, Issue 2, pp. 32–38 ( online at iaddb.org ); Reprint in Grosz: Entry ticket to my brain circus. Memories, writings, letters. Pp. 81-86.

- Brief outline , in: Situation 1924. Artistic and cultural manifestations , Ulm undated (1924), pp. 22–24; Reprinted in: Schneede, The Twenties. P. 125.

- Paris as a city of art , in: Europa-Almanach 1925. Eds. Carl Einstein and Paul Westheim, Kiepenheuer, Potsdam 1925 (Reprint 1993), pp. 42–46; under the title Paris impressions also in George Grosz and Wieland Herzfelde: Art is in danger. Berlin 1925; Reprinted in English in: Flavell, George Grosz. A biography. Yale University Press 1988, pp. 310-311 ( Impressions of Paris ).

- George Grosz and Wieland Herzfelde: Art is in danger. Three essays. Malik, Berlin 1925; Reprint: Athenäum, Königstein im Taunus 1981. Contains: Grosz / Herzfelde: Art is in danger (1925); Grosz: Pariser Impressions (published under the title Paris als Kunststadt in: Europa-Almanach 1925. Potsdam 1925); Grosz: Instead of a biography (first published in: Der Demokratie , II, 1920/21, Heft 3; revised 1925). Reprint of the essay Art is in Danger in: Schneede, The Twenties. Pp. 126-137.

- The Spiesser mirror. 60 Berlin pictures after drawings. With a self-portrayal of the artist. Carl Reissner Verlag, Dresden 1925 ( online at slub-dresden.de ), modified edition 1932. Contains an autobiographical text by Grosz (pp. 5–12) and the text Der Spiesserbiologe by Walter Mehring (pp. 13–14).

- Mein Leben , in Prozektor ( headlight ), VI, No. 14, Moscow 1928, pp. 16-18; Reprinted in: Schneede, The Twenties. P. 153.

- Background. 17 drawings by George Grosz for the performance of Schwejk in the Piscator stage, Malik, Berlin 1928.

- Marginal drawings on the topic , in: Blätter der Piscatorbühne , No. 3 ( shoulder to shoulder , additional cover title: The adventures of the good soldier Schweijk ) Bepa-Verlag, Berlin 1928, (text by Grosz: 2 pages) without pagination.

- Jugenderinnerungen , in: Das Kunstblatt , XIII, 1929. Part 1 ( With photos and drawings from his youth ): Issue 6, pp. 166–174 ( online at iaddb.org ); Part 2: Issue 7 ( online at iaddb.org ), pp. 193–197; Part 3 ( With illustrations from the notebooks, 1927-1929 ): Booklet 8, pp. 238–242 ( online at iaddb.org ).

- Memories of life , in: Art and Artists , XXIX, 1930/31. Part 1: Issue 1 (October 1930), pp. 15–22 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ); Part 2: Issue 2 (November 1930), pp. 55–61 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ); Part 3: Issue 3 (December 1930), pp. 105–111 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ).

- The drawn. 60 sheets from 15 years, Malik, Berlin 1930.

- The new face of the ruling class. 60 new drawings, Malik, Berlin 1930.

- Above all, love. 60 new drawings, Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1930. With a foreword by Grosz; Reprinted in English in: Flavell, George Grosz. A biography. Yale University Press 1988, p. 312 ( Love Above All ).

- Das fein Milljöh , in: Der Cross Section , XI, 1931, Issue 1 (January), pp. 14-17 ( online at arthistoricum.net ).

- Among other things, a word for German tradition (part of the article against the degradation of the spirit by Paul Westheim), in: Das Kunstblatt , XV, 1931, issue 3, pp. 79–84 ( online at iaddb.org ); Reprinted in Schneede, The Twenties. Pp. 277-280.

- Art is over, dear! (Contribution to the article The art goes to bread ), in: Berliner Tageblatt , December 25, 1931, 4th supplement.

- Letters from America , in: Kunst und Küntler , XXXI, 1932. Part 1: Issue 8 (August), pp. 273–278 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ); Part 2: Issue 9 (September), pp. 317–322 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ); Part 3: Issue 12 (December), pp. 433–443 ( online at uni-heidelberg.de ).

- Self Portrait of the Artist , in: Americana , 1st year, November 1932, No. 1, p. 22; Reprinted in Jentsch: George Grosz. The artist's eye. Weingarten 2002, p. 56.

- American manners , in: Der Cross Section , XIII, 1933, Issue 1 (January), pp. 16-19 ( online at arthistoricum.net ).

- Interregnum. 64 drawings and 1 color lithograph ( The Muckraker ), Black Sun Press, New York 1936 (German Propylaen-Verlag, 1976). With the introduction by John Dos Passos : Satire as a Way of Seeing ; under the title Grosz Comes to America in: Esquire , September 1, 1936, pp. 105, 128, 131 ( online at esquire.com ).

- George grosz. Drawings. 49 drawings and 3 watercolors. H. Bittner, New York 1944. With the introduction by Grosz: On My Drawings (pp. 5-8); Reprinted in Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. Pp. 317-319; German translation (abridged) About my drawings in Grosz: Entry ticket to my brain circus. Memories, writings, letters. Pp. 175-178.

- 30 Drawings and Watercolors. Erich S. Herrmann, New York 1944; Reprint: Paul L. Baruch, New York 1948. With an introduction by Walter Mehring.

- A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace , text by Grosz in the catalog for the exhibition A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace, 1914–1946. George Grosz , Associated American Arts Galleries, New York 1946; Reprinted in Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. Pp. 320-321.

-

A Little Yes and a Big No. The Dial Press, New York 1946.

- A small yes and a big no. His life told by himself. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1955; Rowohlt, Reinbek 1974, 1983, ISBN 3-499-11759-2 . With a chapter on the trip to the Soviet Union, 1922, which was in the Americ. EA missing; Verlag Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-89561-332-6 .

- Manhattan fantasy. Planned but not implemented addition to the German edition of the autobiography from 1955. Manuscript, Goerge – Grosz – Archive, Cambridge / Mass .; published in English translation in: Flavell, George Grosz. A biography. Yale University Press 1988, pp. 279-282 ( A Manhattan Fantasy ).

- George grosz. 48 illustrations after paintings, watercolors and drawings, edited by Imre Hofbauer. Nicholson and Watson, London and Brussels 1948. With an introduction by John Dos Passos ( Introduction , pp. 9–10) and a text by Hofbauer ( The Artist and Germany , pp. 11–13).

- I Teach Fundamentals , letter to the students of the Cleveland Institute of Art , written on the occasion of the George Grosz exhibition there, in: College Art Journal , Vol. 9, No. 2 (Winter, 1949–1950), pp. 199–201 ( online at jstor.org ).

- Ade, Witboi , 47 black and white reproductions, 4 colored sheets, 14 text illustrations, Ed. Walther G. Oschilewski . Arani-Verlag, Berlin-Grunewald 1955. With an overall appraisal of the artist von Oschilewski.

- The Arts in America , in: The American Peoples Encyclopedia. Yearbook. Events and Personalities of 1957. Spencer Press, Chicago 1958, pp. 110-113.

- ( “You mistake me for an after dinner speaker”. ) Grosz's speech of thanks for the award of the “Gold Medal for Graphic Arts” from the Academy of Arts and the National Institute of Arts and Lettes , New York, May 20, 1959. Sound document (archive the American Academy of Arts ); German transcription including audience reaction (laughter, clapping in the wrong place) published in Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Catalog, Berlin 1994, pp. 309-311.

Posthumous publications, reprints, letters

- George grosz. 108 black and white reproductions, 6 colored sheets. Edited by Herbert Bittner. Arts, New York 1960; German DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1961. With an introduction by Ruth Berenson and Norbert Mühlen as well as a text by Grosz.

- Homeland figures. Drawings. Ed. Hans Sahl . Fischer Bücherei, Frankfurt 1966. With an introduction by Sahl: George Grosz or The Expulsion from Paradise (pp. VII – XXXII).

- Reprint: The Face of the Ruling Class (1921) & Settlement Follows (1923). Makol, Frankfurt 1972. With an introduction by Grosz: Instead of a biography (1921).

- Interregnum. Reprint of the American edition from 1936. Propylaen-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Vienna 1976.

- The world is a luna park. 232 black and white reproductions and 16 color plates, Ed. Uwe M. Schneede. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1977 (licensed edition by the Pinkus Cooperative, Zurich). With an introduction by Schneede.

- Letters 1913–1959. Edited by Herbert Knust. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1979, ISBN 3-498-02428-0 .

- Oh gaudy world, you Lunapark. Collected poems. Edited by Klaus Peter Dencker. Hanser, Munich / Vienna 1986.

- Entry ticket to my brain circus. Memories, writings, letters. Edited by Renate Hartleb . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-378-00261-1 .

- Ulrich Becher and George Grosz: Message in a bottle. Story of a friendship. Correspondence between Becher and Grosz from 1932–1959, published by Uwe Naumann , Michael Töteberg . Lenos Verlag, Basel 1989, ISBN 3-85787-186-5 .

- Expensive macaroni! Letters to Marc Neven DuMont 1922–1959. Edited by Karl Riha . Argon, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-87024-803-3 .

- Grosz-Berlin. Autobiography, pictures, letters and poems. Edited by Marcel Beyer , Karl Riha. Edition Nautilus Lutz Schulenberg, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-89401-223-4 .

- George Grosz / Hans Sahl: So long with a handshake. Letters and documents. Edited by Karl Riha. Luchterhand Literaturverlag, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 978-3-630-86811-0 . Letters from the years 1950–1959, with two essays by Sahl about Grosz: Die Stockmenschen (1950) and George Grosz or The Expulsion from Paradise (1966).

- The Sketchbook of George Grosz. Edited by Peter Nisbet. Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge / Mass. 1993, ISBN 0-916724-83-2 .

- Ralph Jentsch: George Grosz. The artist's eye. Photographs New York 1932. Art publishing house Weingarten, Weingarten 2002, ISBN 3-8170-2539-4 . In addition to Grosz's photographs, it contains extensive documentation by Jentsch and a text by Grosz from Americana , November 1932: Self Portrait of the Artist (p. 56).

- Hermann Borchardt - George Grosz. "Let's bury the hatchet!" The correspondence. Edited by Hermann Haarmann , Christoph Hesse and Lukas Laier. Wallstein, Göttingen 2019 (series: akte exil. New follow, vol. 2), ISBN 978-3-8353-3490-8 .

Exhibitions and catalogs

- George Grosz , 59th exhibition of the Galerie Neue Kunst / Hans Goltz, Munich, April - May 1920 (10 paintings, 11 watercolors, 40 drawings, 40 graphics). Catalog: The Ararat. First special issue: George Grosz.

- George Grosz , Galerie von Garvens, Hanover, April 1922 (10 paintings, 7 collages, 27 watercolors, 56 drawings and graphics). The catalog contains von Grosz's text: Man is not good - but a cattle .

- Participation in the exhibition Neue Sachlichkeit. German painting since Expressionism , Kunsthalle Mannheim, June 14 - September 18, 1925, then at the Saxon Art Association Dresden, City Museum Kunsthütte in Chemnitz, Art Association Erfurt and Art Association Dessau.

- Special exhibition George Grosz (as part of the spring exhibition ), 5 paintings and 11 works on paper, Prussian Academy of the Arts, Berlin, April / May 1927.

- Participation in the autumn exhibition , 8 works on paper, Prussian Academy of the Arts, Berlin, November / December 1927.

- George grosz. A Survey of His Art from 1918 to 1938 , The Art Institute of Chicago, December 15, 1938 - January 15, 1939.

- Paintings, drawings, prints, by George Grosz , The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 7 - November 2, 1941 ( documentation on the MoMA website ), traveling exhibition, at ten other locations (State University of Iowa, Des Moines Fine Arts Association etc.) from January 4, 1941 to March 29, 1942.

- A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace. Associated American Arts Galleries, New York 1946. Catalog for the exhibition A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace, 1914–1946. George Grosz , Associated American Arts, New York, October 7-26, 1946. With the text A Piece of My World in a World Without Peace by Grosz; Reprinted in Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. Pp. 320-321.

- The Stick Men. New Watercolors by George Grosz , Associated American Arts, New York, April 12 - May 1, 1948.

- Impressions of Dallas by George Grosz. Catalog for the exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, October 4 - November 9, 1952 ( online at dma.org, PDF ).

- John IH Baur: George Grosz. Edited by Whitney Museum of American Art 1954 ( online at archive.org ). Exhibition catalog: Whitney Museum of American Art, January 14 - March 7, 1954; William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, May 1 - May 31, 1954; The Pasadena Art Institute, June 25-July 25, 1954; San Francisco Museum of Art, August 17 - September 19, 1954.

- George grosz. Watercolors, drawings, graphics , Meta Nierendorf Gallery, Berlin, May 12th - July 3rd, 1958, traveling exhibition with the following stations: Kunstvereine Pforzheim, Munich and Frankfurt, Art Cabinet Dr. Hanna Grisebach , Heidelberg, Marseille, Nice, Düsseldorf Art Museum.

- George Grosz 1893-1959. Catalog for the exhibition at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, October 7th - December 30th, 1962.

- Galerie Meta Nierendorf: Without inhibitions - face and downside of the years 1914–1924. Berlin 1962. Catalog for the exhibition at Galerie Nierendorf, Berlin, October 8, 1962 - January 17, 1963.

- documenta III. International exhibition. Catalog, Volume 1: Painting and Sculpture , Volume 2: Hand Drawings , Volume 3: Industrial Design, Graphics , Kassel / Cologne 1964. Works by Grosz were shown in the Hand Drawings Department at documenta III in Kassel in 1964 .

- New Gallery of the City of Linz: George Grosz 1893–1959. Exhibition catalog, Linz 1965.

- George Grosz drawings and lithographs , exhibition catalog, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett, 31.7. - 13.11.1966

- Wieland Herzfelde / German Academy of the Arts in Berlin (ed.): The Malik-Verlag 1916–1947. Exhibition December 1966 - January 1967. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar, 1967.

- Uwe M. Schneede (Ed.): George Grosz. Life and work. Hatje Cantz, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-7757-0102-8 . Publication on the occasion of the exhibitions: Kunstverein Hamburg, October 4 - November 23, 1975; Frankfurter Kunstverein, December 5, 1975 - January 25, 1976; Kunstverein Braunschweig, February 7th - March 21st, 1976; Landesmuseum Münster, April 3 - May 16, 1976; Museum of the 20th Century Vienna, June 2 - July 18, 1976; Badischer Kunstverein Karlsruhe, September 3 - October 17, 1976; Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, October 31 - December 19, 1976; Haus am Waldsee Berlin, January - March 1977.

- George grosz. Works in Oil. Ed. Heckscher Museum, Huntington, New York 1977, ISBN 0-89062-054-7 . Catalog for the exhibition at the Heckscher Museum, July 1 - September 4, 1977. With a text by Eva Ingersoll Gatling (museum director).

- Goethe House New York: Malik Verlag - Berlin, Prague, New York. Exhibition catalog, New York, 1984.

- Museum Villa Stuck Munich / Serge Sabarsky: George Grosz - The Berlin Years. Munich 1986.

- George Grosz, John Heartfield and the Malik Verlag. Ars Libri, Boston / Massachusetts 1994 (Catalog 100). Sales catalog, with an introduction by Peter Michael Grosz (son of George Grosz).

- Peter-Klaus Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Ars Nicolai, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-89479-054-7 . Catalog for the exhibitions: Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie, December 21, 1994 - April 17, 1995; Düsseldorf, Art Collection North Rhine-Westphalia, May 6 - July 30, 1995.

- Vernissage. The magazine for the exhibition. George Grosz in Berlin. Issue 14/1994.

- Back then in Berlin - George Grosz - drawings from the 10s and 20s , Galerie Remmert and Barth, Düsseldorf, October 28th - December 23rd, 1997.

- Juerg M. Judin (Ed.): George Grosz - The Years in America, 1933–1958. Texts by Barbara McCloskey, Ralph Jentsch and Juerg Judin. Hatje Cantz, Berlin 2009, ISBN 3-7757-2434-6 , English edition: ISBN 978-3-7757-2435-7 . Publication on the occasion of the exhibition at Galerie Judin, Berlin, February 28 - April 25, 2009.

- Academy of Arts : Mounted George Grosz. Collages 1917-1958. Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-88331-140-1 . Catalog for the exhibition George Grosz. Correct and anarchic .

- Max Ernst Museum Brühl: George Grosz. «Germany, a winter fairy tale». Watercolors, drawings, collages 1908–1958. Catalog for the exhibition September 11 - December 18, 2011 ( press information on maxernstmuseum.lvr.de, PDF ), Hatje Cantz Verlag 2011.

- Museum of Fantasy , Bernried, 2014: Grosz. War Grotesque - Between Expressionism and New Objectivity.

- Museum Kunstpalast , Düsseldorf , 2014: George Grosz. The great pastime.

- Jan T. Wilms: In search of the human image - reflections on the work of Ernst Barlach, Otto Dix, George Grosz and Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita , in: Jan T. Wilms (Ed.): Menschenbilder - Ernst Barlach | Otto Dix | George Grosz | Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita - Works on Paper, pp. 142–186, English translation of the texts in the booklet, pp. 220–229, Kaufbeuren 2018, ISBN 978-3-9819254-2-5 . Publication for the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Kaufbeuren 2018/2019: Images of People - Ernst Barlach | Otto Dix | George Grosz | Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita - Works on paper .

Bibliographies

- Kjeld Bülow (Ed.): George Grosz 1893–1959. A Bibliography and other check lists. Introduction Robert Cenedella. Booktrader, Copenhagen 1993, ISBN 87-984539-0-4 . Listed: Section A: the portfolios, publications with original graphics and illustrated books (125 numbers, 4 posthumous editions and 4 unrecognized prints,.; With 2 indices); Dept. B: Books on Grosz; Dept. C records the catalogs (not complete); Dept. D: Film u. TV recordings. At 16 full-page. Original lithograph, v. a. Book covers, distributed on art paper and other smaller graphics in the book.

- Lothar Lang: George Grosz Bibliography. In: Marginalien, Zeitschrift für Buchkunst und Bibliophilie , Pirckheimer-Gesellschaft (Ed.), Issue 30, July 1968, pp. 1-42.

literature

- Günther Anders : George Grosz. Verlag der Arche, Zurich 1961.

- Riccardo Bavaj: Between Dadaism and Communism - Art and Ideology with George Grosz during the Weimar period. In: Minerva Institute for German History, Tel Aviv University (ed.): Yearbook 2006 for German History , Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-8353-0009-5 , pp. 122–148.

- Hanne Bergius : Dada's laugh. The Berlin Dadaists and their actions , Anabas-Verlag, Giessen 1989, ISBN 978-3-8703-8141-7 .

- Hanne Bergius: assembly and metamechanics. Dada Berlin - Aesthetics of Polarities (with reconstruction of the First International Dada Fair and Dada Chronology), Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 978-3786115250 .

- Hanne Bergius: Dada triumphs! Dada Berlin , 1917–1923. Artistry of Polarities. Montages - Metamechanics - Manifestations. Translated by Brigitte Pichon. Vol. V. of the ten editions of Crisis and the Arts. The History of Dada, ed. v. Stephen Foster, Thomson / Gale, New Haven, Conn. 2003, ISBN 978-0-816173-55-6 .

- Ralf Georg Czapla : Verism as a critique of expressionism. Otto Dix's “Match Dealer I”, Ernst Toller's “Hinkemann” and George Grosz's “Brokenbrow” illustrations in the context of contemporary art debates. In: Stefan Neuhaus, Rolf Selbmann & Thorsten Unger: Engaged literature between the world wars. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2002, ISBN 3-8260-2395-1 , pp. 338-366.

- Birgit Dalbajewa (Ed.): New Objectivity in Dresden. Sandstein Verlag, Dresden 2011, ISBN 978-3-942422-57-4 , chap. George Grosz , pp. 217-220.

- Kay M. Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 1988, ISBN 0-300-04145-4 . Contains texts by Grosz from the years 1918–1946 (pp. 307–321).

- Jeanpaul Goergen (Ed.): George Grosz. The film half of art. Friends of the German Kinemathek, Berlin 1994.

- Will Grohmann: Grosz, George. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 161 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Ulrich Faure : At the hub of world traffic. Herzfelde, Heartfield, Grosz and Malik-Verlag 1916–1947. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin / Weimar 1992, ISBN 3-351-02400-2 .

- Lothar Fischer : George Grosz . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1976, ISBN 3-499-50241-0 .

- Frank Hermann: Malik. On the history of a publisher. 1916-1947. Droste, Düsseldorf 1989, ISBN 3-7700-0785-9 .

- Hans Hess: George Grosz. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1982.

- Ralph Jentsch: Alfred Flechtheim and George Grosz. Two German fates. Weidle Verlag, Bonn 2008, ISBN 978-3-938803-06-6 .

- Alexander Kluy: George Grosz. King without a country. Biography. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-421-04728-1 .

- Ivo Kranzfelder: George Grosz 1893–1959. Taschen, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8228-6596-6 .

- Wolfgang Maier-Preusker : Book and portfolio works with graphics of German Expressionism. Maier-Preusker, Vienna 2006, ISBN 978-3-900208-37-0 .

- Beth Irwin Lewis: George Grosz. Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic. Madison, London 1971, ISBN 0-299-05901-4 .

- Birgit Möckel: George Grosz in America 1932–1959. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main; Berlin; Bern; New York; Paris; Vienna 1997 (also dissertation, University of Karlsruhe 1996), ISBN 3-631-32307-7 .

- Rosamunde Neugebauer: George Grosz. Power and powerlessness of satirical art. The graphic series “God with us”, Ecce homo and background. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1684-9 (dissertation at the University of Heidelberg ).

- Gerd Presler: George Grosz - With shameless audacity ... , in: Shine and misery of the 20s. The painting of the New Objectivity. DuMont (tb 285), Cologne 1992, pp. 51-55, ISBN 3-7701-2825-7 .

- Marcel Ray: George Grosz , Paris 1927 (German edition: Berlin 1991).

- Uwe M. Schneede: George Grosz. The artist in his company. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1975, ISBN 3-7701-0863-9 .

- That. (Ed.): The twenties. Manifestos and documents of German artists. Edited and documented by Uwe M. Schneede. DuMont, Cologne 1979, ISBN 3-7701-1125-7 . Contains u. a. Texts by Grosz from the years 1918–1931.

- Mario Vargas Llosa : A sad, rabid man. About George Grosz. (1992) Translated from the Spanish by Elke Wehr, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-518-41163-2 .

- Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German communists. Biographical Handbook 1918 to 1945 . 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 , chapter: Grosz, George ( online at bundesstiftung-aufteilung.de ).

- Willi Wolfradt : George Grosz. ( Young Art. Vol. 21) Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1921.

Movie

- 1960: George Grosz 'Interregnum . For an Oscar -nominated documentary (29 minutes) of Charles and Altina Carey

- 1976: George Grosz. A production by Saarländischer Rundfunk / Fernsehen (45 minutes) 1976. Script and direction: Klaus Peter Dencker

- 1991: It's nice in the labyrinth - George Grosz in America. Documentary by Norbert Bunge and Christiane Fischer-Defoy

- 2009: The human pig in sight - The longing of George Grosz. Animated documentary by Alexander Urban

Web links

- Literature by and about George Grosz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about George Grosz in the German Digital Library

- Search for George Grosz in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Newspaper article about George Grosz in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Lutz Walther: George Grosz. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- 28 paintings ( Memento from February 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) in Olga's Gallery

- The reasoning , comment on the judgment for blasphemy by Ignaz Wrobel alias Kurt Tucholsky in the Weltbühne , March 19, 1929

- Publications by Grosz in the International Dada Archive, University of Iowa

- George Grosz in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Materials by and about George Grosz in the documenta archive

- George Grosz Archive in the Archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- The color of tears: the First World War from the perspective of painters

- New Objectivity - The Modern Age, a Madhouse Exhibition review Brühl 2011

- George Grosz in HeidICON illustrations of the Simpl

- GROSZ. KRIEG GROTESK - Between Expressionism and New Objectivity Exhibition from July 6th - November 2nd 2014 in the Museum der Phantasie , Bernried

- exilarchiv.de ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- davidnolangallery.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ Grosz, 1955, p. 18

- ↑ Grosz, 1955. p. 60

- ^ Hans-Albert Walter: German Exile Literature 1933–1950. Volume 1: The prehistory of exile and its first phase. Volume 1.1: The mentality of the Weimar Germans / The “politicization” of the intellectuals. Stuttgart, Weimar, 2003, p. 510.

- ↑ Grosz, 1955, p. 101

- ↑ Grosz, 1955, p. 103

- ↑ Remember Uncle August, the Unhappy Inventor. In: centrepompidou.fr. Retrieved November 16, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Grosz, 1955, p. 116

- ↑ Thomas Kliemann: - Culture - The philistine horror. In: General-Anzeiger. December 31, 1998, accessed November 16, 2019 .

- ^ Genocchio, Benjamin (April 3, 2005). “Heckscher Museum Decides Not to Sell Grosz Painting”. The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2011

- ↑ kuenstlerbund.de: Ordinary members of the German Association of Artists since it was founded in 1903 / Grosz, George ( Memento from April 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on March 21, 2016)

- ↑ Catalog of the Deutscher Künstlerbund Cologne 1929. May – September 1929 in the State House , M. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1929. (p. 19: Grosz, George, Berlin . Cat. No. 108, Fig. Cat. No. 109 on p. 63 )

- ↑ Jentsch, Ralf; Alfred Flechtheim and George Grosz, Bonn 008, page 61ff.

- ↑ For the background and reception of Interregmum see Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. Pp. 155-173 ( Background to Interregnum ). The content of the portfolio is documented in Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Catalog, Berlin 1994, pp. 479-487.

- ^ Hanne Bergius: Dada Berlin . In: Trends of the Twenties. 15th European Art Exhibition Berlin 1977 . (Catalog) Dietrich Reimer Verlag Berlin, Berlin 1977; P. 3/72

- ^ Der Tagesspiegel , Berlin, from October 28, 1955

- ^ Review of the dissertation by Gisbert Laube: Der Reichskunstwart. History of a cultural authority 1919–1933 by Christian Welzbacher on uni-heidelberg.de

- ^ Reproduction ( memento of May 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) in the scienzz magazine

- ↑ George Grosz: Shut up and keep serving! , Der Tagesspiegel , July 2, 2001

- ↑ Ursula Scheer: The man on the cross wants to tell us something. In: FAZ , January 31, 2015, p. 13

- ↑ Claus Bernet, in the article Art, Religion and Quakerism ; in: The Independent Fried of July 2, 2009

- ↑ Michael Sontheimer: Displaced images . In: Der Spiegel . No. 13 , 2009, p. 148-149 ( online ).

- ↑ Jentsch, Ralph; Alfred Flechtheim and George Grosz, Bonn 008, page 118 ff.

- ↑ Jentsch, Ralf; Alfred Flechtheim and George Grosz, Bonn 008, page 96ff.

- ↑ Judin, Juerg (ed.); George Grosz, The Years in America 1933-1958; New York 2009

- ↑ nationalacademy.org: Past Academicians "G" / Grosz, George ANA 1950 ( Memento from January 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed June 25, 2015)

- ↑ Members: George Grosz. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ^ Letter from Walter Mehring to Erwin Piscator, December 8, 1959, in: Erwin Piscator: Briefe. Volume 3.2: Federal Republic of Germany, 1955–1959 . Edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2011. p. 784

- ↑ There were depressing reports about the circumstances of Grosz's death: “Böff drunk himself to death, yesterday Wieland Herzfelde was with me and reported absurdities about the end. He is said to have fallen hard in front of a new building, to have groaned all night, no doctor could be moved. In the morning workers helped his wife to carry the dead man up. The doctor rushing up laconically noted the heartbeat. ”Erwin Piscator's letter to Felix Gasbarra , September 8, 1959, in: Erwin Piscator: Briefe. Volume 3.2: Federal Republic of Germany, 1955–1959 . Edited by Peter Diezel. B&S Siebenhaar, Berlin 2011. p. 740

- ↑ Grosz buried yesterday . In: Hamburger Abendblatt . Saturday / Sunday, 11./12. July 1959. S. 9. Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial places . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 . P. 487.

- ↑ Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection: Honorary Graves of the State of Berlin (as of November 2018) (PDF, 413 kB), p. 29. Accessed on November 10, 2019. Recognition and further preservation of graves as honorary graves of the State of Berlin (PDF , 205 kB). Berlin House of Representatives, printed matter 17/3105 of July 13, 2016, p. 1 and Annex 2, p. 5. Accessed on November 10, 2019.

- ↑ George Grosz papers, Harvard University ( Memento of July 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) as well as the George Grosz Archive in the Archive of the Academy of Arts .

- ^ Print easily accessible in Berghof (Red.): Art in the persecution: Degenerate art (exhibition) 1937 in Munich. 18 examples. Neckar, Villingen 1998, without ISBN, large format

- ↑ 100 masterpieces. “Metropolis” by George Grosz (1893–1959). In: TV hearing and seeing 36/2011, p. 31

- ^ FAZ of August 28, 2010, page 36

- ↑ Information from Birgit Möckel: George Grosz in Amerika 1932–1959. P. 564 and Heckscher Museum (ed.): George Grosz. Works in Oil. New York 1977, p. 26. Fig. In George Grosz. Works in Oil. P. 17.

- ↑ Fig. In Heckscher Museum (Ed.): George Grosz. Works in Oil. New York 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ Fig. In Heckscher Museum (Ed.): George Grosz. Works in Oil. New York 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ Fig. In: Birgit Möckel: George Grosz in Amerika 1932–1959. P. 305.

- ↑ Fig. In: Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Berlin 1994, p. 380.

- ↑ Information from Ralph Jentsch: George Grosz. Chronicle of life and work , in: Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Berlin 1994, p. 552. Fig. In: Birgit Möckel: George Grosz in Amerika 1932–1959. P. 314.

- ↑ Fig. In: Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Berlin 1994, p. 442.

- ↑ Fig. In: Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Berlin 1994, p. 443.

- ↑ Fig. In: Schuster (Ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Berlin 1994, p. 382.

- ↑ Fig. In: Flavell: George Grosz. A biography. , P. 290.

- ↑ According to a comment on a reprint of the Dadaist Manifesto in Huelsenbeck (ed.): Dada Almanach (Erich Reiss Verlag, Berlin 1920), Huelsenbeck is the author; ibid., p. 36 ( online at The International Dada Archive , uiowa.edu ).

- ^ Title in Schuster (ed.): George Grosz. Berlin - New York. Catalog, Berlin 1994, p. 309.

- ^ Announcement on the exhibition ( Memento from September 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Announcement on the exhibition ( Memento from September 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 22, 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Grosz, George |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Groß, Georg Ehrenfried (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-American painter, graphic artist and caricaturist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 26, 1893 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 6, 1959 |

| Place of death | Berlin |