sailing

Sailing is the movement of a sailing ship or a sailing boat using wind energy . For many centuries, sailing ships were of great importance for trade and transport, warfare and fishing worldwide. Towards the end of the 19th century they began to be displaced by machine-driven ships, which were less dependent on the weather conditions and made possible shorter journey times, fewer personnel and thus lower transport costs.

Today, in the developed world sailing is almost exclusively as a recreational activity or competitive sport operated, though war and trade navies continue to sail training vessels entertain train their offspring. In other, less developed regions, on the other hand, sailing ships have partially retained their economic importance to this day. From the Persian Gulf, for example, dhows are carrying loads to India and Africa as they did hundreds of years ago .

In the course of time, sailing ships have developed in many different designs and sizes, whereby a basic distinction can be made between displacers (mostly larger and heavier ships) and gliders (mostly small, light and fast boats). The spectrum ranges from the one-person dinghy to yachts and catamarans to tall ships with a crew of several dozen. A variety of sailing maneuvers has been developed for the different types of ship, which are brought to perfection in sporting competitions . A basic understanding of the structure of the ship and the physical principles of sailing is helpful for this. Depending on the size of the ship and the area in which the vessel is sailing, basic nautical skills and knowledge of various legal regulations and conventions are also required.

history

See also: History of the Development of the Sailing Ship , History of Seafaring , Roman Navy , History of Viking Shipbuilding .

antiquity

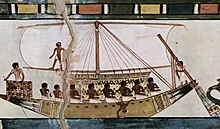

The first known depiction of a ship with a sail is on an Egyptian funeral urn from Luxor from the time 5000 BC. To find. The Egyptians used ships with a mast and a large square sail primarily for trips on the Nile , but also for trips across the Mediterranean and the Red Sea . The sail was already pivoted so that the ships could sail even in sideways wind.

In the South China Sea around 3000 BC. Chr. Outrigger canoes developed and the colonization of Polynesia used. Further developments of these multihull boats, such as pirogues and proas , are still used today in regattas or as commercial vehicles.

The Phoenicians and Greeks developed from around 1000 BC Two basic types of seaworthy sailing ships: the cargo ship with a spacious hull and a large square sail and the galley , which had a mast with a medium-sized square sail for cruising, but was rowed with oars during a sea battle and in calm conditions .

In the centuries that followed, sailing ships were used for numerous voyages of discovery and conquest. For example, the Greek historian Herodotus reports on the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II , who lived in 596-594 BC. A first circumnavigation of Africa (clockwise) initiated by Phoenician seafarers. The Greek geographer Skylax undertook around 508 BC. A voyage of discovery from the mouth of the Indus to the Arabian Gulf and on around the Arabian Peninsula to the Red Sea and Egypt. Around the year 470 BC The Carthaginian ruler and admiral Hanno the navigator sailed westward from Carthage, through the Strait of Gibraltar along the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Guinea . His Periplus (trip report) is handed down within a Greek manuscript of the Codex Palatinus Graecus . The Greek navigator Eudoxos from Kyzikos undertook 120 to 117 BC. An exploration trip to India and recognized the importance of the monsoon winds for sailing in the Indian Ocean .

At the turn of the century , the Romans also used combined rowing and sailing ships for war and trade purposes. The bowsprit as part of the rigging is considered to be an essential further development of this period . With the expansion of trade between Syria and Italy in goods from the Far East , attacks by pirates on merchant ships also increased sharply. In 102 BC The plague of the Cilician and Cretan pirates became so bad that Rome decided to take countermeasures. The speaker Mark Antony the Elder made a move against Cilicia , but with only moderate success. At all times of the Roman Empire, the Roman fleet was of relatively little importance in relation to the importance of the land army.

Viking Age and Middle Ages

The Saxons and Angles, who emigrated as Anglo-Saxons towards the end of the Roman Empire across the North Sea to England, had longships with a mast and a square sail. The Vikings perfected this type of ship from the 6th century to the 8th century. The development of a functioning rigging was the most important technical advance in shipbuilding . In conjunction with the slim, double-ended ship type, the Viking ships could reach speeds of up to 20 knots (37 km / h).

After the end of the Viking Age, the Hanseatic Cog was developed from the wider, open merchant ships in the north . It had only one mast and formed the backbone of the long-distance trade of the Hansa. Towards the end of the Middle Ages two- and three-masted ships were also built. From them the caravel was developed in Spain and Portugal , with which Christopher Columbus , Ferdinand Magellan and Vasco da Gama undertook their voyages of discovery. At the beginning of the 15th century, the Chinese admiral Zheng He made numerous voyages in the Indian Ocean to East Africa.

Modern times

Since the 17th century more and more specialized forms were used, including ships of the line (as warships with several cannon decks) and frigates (lightly armored ships of increased speed). The shipbuilders developed more and more sophisticated sails. The ships were leaner, had more depth and could always higher the wind sailed. The increase in merchant shipping in the 19th century brought the fast, sleek clippers , which reached average speeds of up to 18 knots.

The use of iron ( steel from around 1890 ) as boat building material heralded the age of the great windjammers . In 1902 and 1911 respectively, the Prussians and the France , the largest sailing ships of all time, were launched. At the same time, sailing ships were increasingly replaced by the more maneuverable and economical steam and later motor ships . Today, sailing ships are almost exclusively used as training ships or sports boats in industrialized nations . The largest sailing ship currently in operation is the Royal Clipper , which is a luxury cruise ship.

For leisure purposes, sailing boats were used on a larger scale from the beginning of the 18th century, especially at court and by wealthy business people in England and the Netherlands. In 1720, the first yacht club was founded in Cork, Ireland , and in 1749 the Prince of Wales started the first regatta involving a trophy. In the second half of the 19th century, several important sailing regattas were launched, such as the America's Cup in 1851 and the Kieler Woche in 1882. Germany's first sailing club was founded in 1835 under the name Tavernen-Gesellschaft in Stralau (since 1920 a District of Berlin), but did not last long. The oldest existing German sailing club, the Rhe sailing club , was founded in Königsberg in 1855 . The first Olympic sailing competition was held in 1900 . While sailing began as an elite sport for rich people for reasons of cost, it has now increasingly developed into a popular sport .

Parts of a sailing ship

Regardless of its size, every sailing ship consists of three main components: one or more hulls , the sails and the rig .

The fuselage can be made of steel , aluminum , glass fiber reinforced plastic (GRP) , concrete or wood . Ships with one hull ( yachts and dinghies ) are also called "monohulls", in contrast to Proas , catamarans and trimarans , which consist of two or three parallel , connected hulls and are called " multihulls ". The hull usually has a fin firmly attached to the hull on its underside - the keel or the sword, which is mainly variable in depth . These components should reduce the drift (drifting) of the ship in side winds (see hull shapes and stability ) and ensure the stability of the ship when lying on its side ( heel ). Furthermore, on the underside of the hull or, in the case of smaller boats, at the end of the hull, the or rarely the oars . On deck it is connected to a tiller or a steering wheel , which is used to steer the boat.

The sails are generally divided into square sails and pitched sails . Square sails are the sails that stand transversely to the midship plane and are therefore particularly suitable for sailing with wind from behind (aft wind). For sailing diagonally against the wind, when cruising , they are only capable of large turning angles in relation to sloping sails. Therefore, with the exception of traditional ships , they are no longer or only rarely in use today.

In contrast to this, the sloping sails, which are attached with their leading edge ( luff ) in the midship plane, for example on the mast, also allow the ship to sail diagonally against the wind (close to the wind ). There are even finer subdivisions according to the shape of the sail, e.g. B. in latin sails , lug sails , spritsail , gaff sails and high sails .

A modern Bermuda rig can set a course of up to 30 degrees with a drift of up to 0 degrees , a classic Schratrigg a course of 45 to 50 degrees with a drift of about 5 degrees and a Rahrigg can courses to the wind of about 60 degrees at 10– Reach 15 degrees of drift.

The large, bulbous, mostly colorful spinnaker , also simply called "Spi", occupies a special position, as it cannot be assigned to either the group of square sails or the group of pitch sails. It is only held at its three corners and is mainly used to offer a large attack surface for aft winds.

As previously sail material was cotton used. Today it has largely been replaced by polyester fabric , and in modern regatta ships also by aramid fiber fabric (trade name Kevlar ) or laminates .

The rig (sometimes also called rigging ) includes mast and boom as well as standing and running rigging . In this context, good means something like cordage. The standing rigging is almost always made of steel wire and supports the mast. These include the stage , which hold the mast forwards and backwards, and the shrouds, which give it lateral support. All ropes on the ship that are used to adjust the sails are referred to as running rigging. These include in particular traps with which sails are set and recovered, and sheets with which the angle of attack of the sails to the wind is changed. Depending on the type of rigging , ships have one ( sloop , cutter ) or several masts ( yawl , ketch , schooner ) each with one or more sails.

Physical basics of sailing

Propulsion of a sailing ship

A sailing ship is propelled by two effects: by wind pressure on the sail and by air flow around the sail, which pulls on the sail due to the negative pressure. In practice, both effects usually overlap, with one or the other predominating depending on the course to the wind. When the ship is moving, the counterforce to propulsion is essentially the water resistance that acts on the hull. The main propulsion results from the transmission of the wind pressure to the mast (s) and sheets that guide the sails, and the force is in turn transmitted to the hull . The fuselage is practically "pulled along".

Wind pressure on the sail

If the wind hits the sailing ship from behind (on a downwind course ) or diagonally behind (on a downwind course), the sailing ship is driven by the resistance that the sails oppose to the wind. The air flow is interrupted and the wind tries to "push away" the resistance. This type of propulsion is best used by the square sails formerly used on tall ships . Tall ships, too, drove faster on a downwind course than on a downwind course, as most of the sails in the latter are in the slipstream of the rearmost sails. Modern sailing ships with sling sails are not particularly well suited for propulsion by drag, as the sling sails lack sail area, especially in the upper, more effective area. In order to compensate for these disadvantages, large, bulbous sails such as spinnakers or gennakers are also used in the course area Before the Wind to Half Wind .

Wind flow on the sail (wing effect)

Sailing ships are able to sail diagonally against the wind and cruise up . This allows goals to be achieved that are against the wind direction. While having fore- the greatest efficiency. In terms of flow technology, sails behave similar to the wing of an airplane. The curvature (the belly) of the sail causes complex aerodynamic processes and currents around the sail. Essentially, they cause the air to be deflected from its original direction. This requires a force. This force is partly converted into propulsion and partly into drift to leeward and - through the resistance of the keel or sword under water - into heeling (inclined position of the ship).

The angle of incidence of the wind is not only determined by the course angle of the ship to the actual wind, but also by its own speed. The effective wind relevant for the sails, the apparent wind, will always come in earlier than the true wind. Since the speed of the apparent wind also increases with the boat speed, it is possible to sail faster than the wind .

stability

An essential task of the keel or sword is to oppose the laterally acting wind pressure on the sail with a resistance under water in order to reduce the drift to leeward . The resulting lean angle of the boat is called heeling . A boat can also be heeled by rough seas. The stability of a boat is understood as its ability to compensate for this heeling and to return to an upright position on its own. This can be done in two different ways: on the one hand through dimensional stability , in which the hull shape of the boat favors a return to the starting position, and on the other hand through weight stability , in which a low-lying ballast keel forces the boat back into the upright position.

In weight-stable yachts , the ballast keel generates an erecting torque that becomes stronger with increasing heel. Such a boat has a low initial stability , but a high final stability , and can only capsize under very severe wind and sea conditions . In contrast, in dimensionally stable boats, such as a dinghy , the heel is compensated for by the buoyancy of the hull and the crew's weight is shifted to windward ( riding out ). Since the heel also reduces the wind pressure in the sail, a lean angle can be compensated up to a certain degree in this way. With increasing heel, however, the righting torque is reduced , which can ultimately lead to capsizing.

Sailing maneuvers and sailing practice

trim

The trim of a ship is its “settings”, such as the weight distribution on the ship, the position of the sails in relation to the wind and more or less strong tension on different lines. The trim influences, among other things, the speed of the ship, the heel , the course stability of the ship and its behavior in sea conditions . A distinction is made between weight trim , sail trim and mast trim.

Weight trimming is accomplished by shifting the weight of the crew, by moving keel constructions or by pumping water from various ballast tanks. In this way, on the one hand, the inclination (heeling) of the ship and, on the other hand, the correct weight distribution in the ship's longitudinal direction can be set.

Sail trimming and mast trimming require a high level of knowledge and experience as many trimming devices influence each other. Important trim options include the angle of the sail to the wind (adjustable via the sheets ) and the belly of the sail (adjustable, among other things, via the tension of the leeches and the boom vang ). The position, inclination and bending of the mast also play a role (controlled by the backstay or forestay ). The optimal trim of a sail depends on the wind strength, the sea state and the course of the ship to wind and waves. The goal of trimming also plays a role, such as high speed, a high course close to the wind or comfortable behavior in the sea.

Courses to the wind

In the case of sailboats, the direction of travel is designated according to the position of the boat in relation to the apparent wind , as the direction and position of the sail depend on this. The course of a ship to the wind is, strictly speaking, the angle between the direction in which the bug is (the right direction of advance ), and the direction from which the apparent wind comes from. In practice, a qualitative distinction is only made between upwind course (wind at an angle from the front), half wind course (wind from the side), space sheet course (wind at an angle from behind) and downwind courses (wind from exactly behind). Depending on the course, the propulsion by the current on the sail or the propulsion by propulsion predominate (see above ).

Sailing maneuvers

A sailing maneuver is generally referred to as any process in which the course of the ship to the wind or the guidance of the sail are changed. A detailed description of the sailing maneuvers listed here can be found in the respective main articles.

Course changes

Turning the boat to the wind (with the bow facing the wind direction) is called luffing . The opposite movement, with the bow away from the wind, is called falling away . A turn of the bow tip through the wind so that the sail is flown against from the other side is called a turn . The opposite process of turning the stern with the wind is called jibing . A special form of the turn is the Q-turn (also known as the “cow turn”), which can be used instead of a jibe. A destination that is in the direction from which the wind is blowing can be reached by crossing (also called crossing ), i.e. moving on the wind at an angle in the direction of the destination with regular turns .

A shoot-up is the act of turning the boat beyond luffing with the bow tip into the wind. This is the only way to bring a sailing ship to a standstill. However, this condition is not stable because the ship picks up stern voyage due to the wind from the front and quickly drops to one side with a slight sideways wind.

Turning and bending is called a maneuver and its result, in which the foresail is set back (on the "wrong" side of the ship, namely the windward side ). As a result, the boat is very calm and almost across the wind and only moves a little forwards and leeward . Shifting a sail means moving the sail to the other side of the ship on a downwind course without changing course.

A man overboard maneuver is used to bring the boat back to a person who has gone overboard. There are different versions of this maneuver, which are more or less applicable depending on the type of boat, current sail guidance and wind and sea conditions.

Sail guidance

Before a sail can be used, it must be attached , that is, attached to the rig, if it doesn't stay permanently attached anyway. To sail, the sail must be set (that is, usually pulled up); it is recovered at the end of the journey or when changing sails .

Reefing is also part of the sail handling : In order to reduce the heeling of the boat in strong winds or storms, the area of a sail exposed to the wind can be reduced. When the wind subsides , the sail can be reefed , i.e. the sail area can be increased again. There are different reefing systems, each with their advantages and disadvantages. The lower part of the sail is gathered in several stages on the tree with a binder and fixed there. With a furling , however, the sail is continuously rolled into the mast or in / around the tree. A headsail with a furling system is wrapped around the forestay , which is then often designed as an aluminum profile around the actual wire rope. Winding is often supported by a reefing line that is guided endlessly around a drum, or in the case of large yachts by means of electric or hydraulic drives.

If the sail area is still too large when the wind continues to increase, special storm sails must be set ( storm jib as headsail and Trysail instead of the main sail) or the sails must be recovered completely (see weathering ).

Heavy weather sailing

Strong winds or storms represent a particular challenge for the crew of a sailing ship. In order to avoid excessive heeling or capsizing , the sail area is reduced by reefing . If sailing in the true sense of the word becomes impossible due to ever higher wind speeds, attempts are often made to stabilize the ship by laying it around. If the sea is so heavy that it is no longer possible to bend it , all sails are recovered and the ship billows from the top and rigging , which means that the ship is driven only by the wind power onto the rig, from wind and waves. The helmsman thereby has the difficult task of the tail to keep the ship to oncoming wave and a broaching prevent.

A sea anchor can be deployed over the bow or stern of the ship in order to reduce the speed of the boat when it runs down in front of the waves . Which storm tactic is most successful depends heavily on the particular boat, the composition and condition of the crew, the prevailing weather conditions and the distance to land (or shallows).

Sailing

There are two different types of sporty sailing: regatta sailing and cruising - comparable to the difference between a bike race and a bike tour. Sailing has been an Olympic sport since the 1900 Olympic Games .

Regatta sailing

Regatta sailing is a competitive sport in which a previously agreed route is driven by two ( Match Race ) or more ( Fleet Race ) boats at the same time. The duration of a competition can range from hours for dinghy regattas to months for offshore regattas. In dinghy regattas, several races are usually carried out in one regatta, the individual results are summarized according to a prescribed procedure to determine the winner. Regattas are usually held according to the racing rules of World Sailing . A regatta is often driven in the so-called "Olympic triangle".

Smaller keelboats and dinghies are usually so-called unit classes (also called one-designs ). These boats are subject to strict restrictions (class regulations) in terms of construction and equipment. This ensures that boats of equal value sail against each other and that the focus is on sailing skills.

In the case of larger yachts, however, the number of boats is too small to have sufficiently large starting fields. Different boats have to sail against each other here. In order to make the competition fair, there are so-called measurement formulas, according to which the speed potential of the boats is theoretically calculated in advance ( IMS , IRC, ORC ) or is determined from empirical values (e.g. yardstick ). Each boat receives an individual race value with which the sailed time is corrected at the so-called "calculated time". The first boat to cross the finish line is therefore often not the winner, as a slower boat may have performed better after the calculated time.

The two largest sailing events in the world are the Kiel Week with regattas in Olympic and non-Olympic boat classes and the Travemünde Week with races in 34 classes. The Warnemünde Week is also of great national importance. These regattas are open to any non-qualified participant, others require prior elimination. Probably the most elaborate regatta is the America's Cup , which has existed since 1851 and is held in protected coastal waters at the choice of the defending champion. Well-known offshore regattas are, for example, the one-hand regatta Vendée Globe around the world, and the Volvo Ocean Race , a circumnavigation that takes place every four years. As in any competitive sport, the logistical and financial outlay for participating in regattas is greater, the more international the event is and the higher your own standards. In order to reduce this effort a little and to have the possibility of regular training with like-minded people, regular regatta sailors are usually organized in sailing clubs.

Cruising sailing

Under cruising usually lasting several days are sailing understood that may be pronounced sporty, more or less, but rather the recovery or the advancement serve as the competition with other boats. Cruising sailing covers a broad spectrum, from short day trips to circumnavigating the world over several years . His fascination lies above all in the intense experience of the surrounding nature and the challenge of coming to terms with its forces and using them for yourself. The concentration on the process of sailing itself, which is necessary for this, has a strong recovery effect from everyday life for many sailors after a short time.

The equipment of a charter yacht is usually designed much more for living comfort and safety than that of a regatta yacht , which is mainly trimmed to be light. A multi-day trip differs from a day trip, which usually ends in the port of departure, mainly because of the significantly higher need for food, drinking water and equipment. When sailing at night, significantly more experience and equipment are required for safety and navigation than for daytime sailing. Long-term trips , especially if they lead out to sea (so-called blue water sailing ), require careful planning and a lot of experience both in seamanship and in crew management, since heavy weather and storms must be expected outside of a period covered by the weather report . In addition, help cannot be requested in an emergency, which is why accidents or damage to the boat must be dealt with by the crew themselves over a longer period of time. Worldwide blue water sailing is still a great adventure today, because it leaves the usual protection and comfort of civilization.

In contrast to regatta sailors, cruising sailors usually organize their trips on an individual basis and are rarely organized in clubs. But there are clubs like Trans-Ocean , which were founded with the purpose of offering blue water sailors bases and contacts all over the world and to facilitate the mutual exchange of messages.

Statutory Regulations

Training and driving licenses

In coastal and inland waters , each state has its own driver's license and regulations for operating sailboats. In the territorial waters of other states, the skipper needs at least the driving licenses that are required in his native coastal waters. While the port authorities within Europe usually mutually recognize driving licenses for the coastal area, outside Europe clarification is necessary in individual cases. No license is officially required to sail on the high seas . Regardless of the legal regulations, however, charterers of sailing yachts or insurance companies occasionally require proof of additional knowledge from the skipper and sometimes also from the co-skipper. Such additional knowledge can be proven, for example, by voluntary higher certificates for the corresponding shipping area or by confirming nautical miles. The following describes the legal regulations for pleasure craft in the German-speaking area.

Germany

In Germany there are a total of five official driving licenses and two non-official driving licenses that entitle you to drive a sport boat. In general, a driving license is not required to drive a sailing boat without a motor, unless there are other local regulations (see below). For boats with an engine from a total engine output of 11 kW (15 HP ) on inland waterways the sport boat license inland (IZA, international certificate A) and on sea routes the sport boat license sea (IZB, international certificate B) is officially required.

In addition, there are other permits for the sea area, but these are not officially required for private (non-commercial) use of the boat. These certificates serve as proof of qualification e.g. B. towards insurance companies, charter companies or fellow sailors. These are:

- Sportküstenschifferschein (SKS) up to twelve nautical miles (sm) from the nearest country

- Sportseeschifferschein (SSS) up to 30 nm from the baseline and unlimited for the North and Baltic Seas as well as the Black Sea and Mediterranean

- Sporthochseeschifferschein (SHS) for worldwide travel

For commercial use of a yacht, the SKS, SSS and SHS certificates are required by law for the corresponding sea area.

In inland waters that are not subject to the federal government (for example in and around Berlin and on Lake Constance ), additional or different regulations may also apply, for example in Berlin a sports boat license inland (under sail) is required from a sail area of three square meters 14 years can be acquired. On some waterways there is the possibility of driving pleasure craft without a license with a so-called "charter certificate". In order to participate in inland or marine radio and to purchase large-caliber distress signaling equipment , separate evidence and certificates must be acquired. The tests for all relevant driving licenses are carried out by the German Sailing Association (DSV) and the German Motor Yacht Association (DMYV) on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Transport (driving licenses) and the Federal Network Agency (radio certificates).

Austria

Training in Austria takes place in sailing or seafaring schools. The basics of sailing can be learned in the basic sailing course. The junior certificate (age of the candidate up to twelve years) or the basic sailing license (from 12 years) can be acquired through a small final examination.

The A-license of the Austrian Sailing Association (OeSV) is the next higher level of training. It is valid on Austrian inland waters and ends with a theoretical and a practical test. The examination is carried out by examiners appointed by the sailing association. You can take the exam from the age of 14.

Further training steps are planned for sailing at sea. For the final exams of these courses, the completed 18th year of life, the 16th year of age for driving area 1, as well as evidence of already covered nautical miles are required. The license for driving area 1 (day trip and mudflat trip) authorizes you to drive a yacht up to a maximum of 10 meters in length and a maximum of 3 nautical miles from the coast. The certificates of proficiency for driving close to the coast or driving along the coast entitle you to independently drive a sailing yacht in driving area 2 (driving along the coast - up to 20 nautical miles from the coast) or driving area 3 (driving close to the coast - up to 200 nautical miles from the coast). There is a length restriction of up to 24 meters for driving areas 2, 3 and 4. A certificate of competence for driving area 4 is required for independent sailing yachts worldwide. There are various examination centers approved by the Austrian Ministry of Transport and Innovation that conduct examinations that lead to the application for a so-called IC (international certificate). There have been no official Austrian qualifications since 2012.

Switzerland

In Switzerland , too, there are practical and theoretical courses in sailing schools to learn to sail. For sailing boats with a sail area of more than 15 m², a category D driver's license (D license) is required. In order to obtain this certificate, it is necessary to take a theoretical and a practical test. For sailboats with an auxiliary engine of more than six kilowatts , the boat license A (A license) is also required. If you want to sail at sea under the Swiss flag, you need an International Certificate for Operators of Pleasure Craft . Prerequisites for this are the D or A license, a passed theory test and proof of sea experience in the form of 1000 nautical miles driven.

Avoidance rules and lights

According to the international collision prevention rules (KVR), motor vehicles are generally obliged to give way to sailing vehicles. Exceptions apply, for example, to motor vehicles with restricted maneuverability. When sailing vehicles meet each other , the course to the wind and the position of the sails decide which of the two vehicles has to evade. In the coastal area and in inland waterway transport, different regulations apply to the encounter between sailing and motor boats, which (in Germany) are laid down in the Maritime Traffic Regulations and in the Inland Waterways Regulations and are supplemented by local regulations (e.g. the Hamburg Port Regulations) can. In the inland area, the obligation to give way depends, for example, on the course of the fairway and the size of the ships involved.

In addition to the evasive rules, these legal texts also stipulate the use of lights for sailing vehicles. In most cases, sailboats need a red and a green sidelight and a white stern light when they are in motion . On boats less than 20 meters in length, the side lights can be combined in a two-color lantern or, including the stern light, in a three-color lantern in the mast top. A white all-round light is also sufficient for very small sailing boats.

Yacht Customs

Flag management

As a rule, seagoing yachts use the following flags :

- your own national flag on a flagstick at the stern . At sea, a ketch or yawl leads the national in the top of the mizzen mast , a ship with a gaff rig attached to the gaff of the eighth sail (mostly mainsail or mizzen sail),

- abroad, the (smaller) courtesy flag below the starboard - Saling ,

- the club stand of your own sailing club in the mast top of the main mast or under the port saling,

- During a high seas sailing regatta, a (private) racing flag is often used instead of the club stand; the national flag is not used in the race at sea, but only when requested by e.g. B. shown by a warship,

- If necessary, signal flags under the port spreader (when signaling, of course, without the club stand).

- very rarely the national flags of the home countries of crew members below the port spreader, if these are to be specially mentioned or honored.

- After traveling abroad on return to the home port , the host country flags of the countries visited are often set under the starboard spreader in the order of the ports called from top to bottom.

The club stand blows in its place day and night. Some yacht sailors follow the tradition of hoisting the national and host country flags in the morning and lowering them in the evening. This ceremonial is called the flag parade and it seems to be still common in northern European waters.

Rules of courtesy

A number of rules of courtesy have become established among yachting people. This includes, for example, that guest yachts entering a port are shown by locals to find a free berth and that they are ready to provide assistance during the mooring maneuver. If someone wants to go alongside another yacht because there are no more berths available, permission should be obtained and enough fenders should be deployed. It is customary not to refuse this permission as a rule. If you have to climb over a foreign yacht to go ashore, you should go (of course not with dirty street shoes) over the foredeck of the foreign yacht and not through the cockpit in the back of the ship, from where you can see the private rooms.

In domestic and foreign ports often also need for pleasure boats mooring fees as Bringschuld be paid to the harbor master. It is good yacht use not to cheat the harbor dues.

Cultural

Sailing in literature

The sailing literature can be divided into several areas. In addition to the specialist literature that is available on almost every aspect of sailing, there are a number of books that are intended for entertainment, but are primarily aimed at sailors. Often times, these books describe circumnavigations or other sailing trips. Well-known authors are Bobby Schenk , Wilfried Erdmann and Karl Vettermann for the German-speaking area and Adlard Coles and Bernard Moitessier for the English- and French-speaking area.

The third category is historical entertainment literature, in which sailing ships play an important role. For example, was the legend of the Flying Dutchman , an eternally before the Cape of Good Hope crossing ghost ship , by authors such as Heinrich Heine and Wilhelm Hauff treated as well as in several films.

Sailing in Music

Sailing is also repeatedly taken up in music. Since the 15th century at the latest, shanties (work songs for the collective rhythmic work on the rope ), such as the halyard shanty for setting the sails ( Hamborger Veermaster ) or the short drag shanty for short rope work ( What shall we do with the drunken sailor? ) . In 1843 the opera The Flying Dutchman was premiered by Richard Wagner . The topic of sailing also appears occasionally in popular music . Examples include Sailing , made famous by Rod Stewart (1975) and the British television series Sailor , as well as the Caribbean folk song Sloop John B , which was popularized by the Kingston Trio and the Beach Boys (1966). The song La Paloma , composed by Sebastián de Yradier around 1861 , was processed by over 25 performers. Peter Reber wrote many of his most successful titles while traveling the world on a sailing yacht.

The song Sail away was sung in 1992 by Hans Hartz and three years later by Joe Cocker for the advertisement of Beck & Co. with a tall ship with green sails, which has been represented by Alexander von Humboldt since 1988 .

Idioms

Some sailing-specific expressions from the sailor's language have passed into everyday language. For example, a well- dressed person is dressed very conspicuously. Someone can show up (show up), take off the sails (give up), tease someone (explain) or take the wind out of their sails ( take away the basis for arguments).

Related sports

The windsurfing , in which only one sail is attached to a narrow board, similar from a physical standpoint sailing with a planing dinghy . In both cases, the water resistance is very low, and the trim is largely done by shifting body weight, which requires a good sense of balance. The same evasive rules apply to windsurfers as to dinghies , and the driving license regulations are very similar. There are experiments like the Océankite , which propel a real hull with a stunt kite like in kitesurfing .

When ice sailing is sailing on frozen lakes and rivers. Due to the low frictional resistance of the sled's runners on the ice, speeds of over 100 km / h can be achieved. Another variant is sand sailing , which is practiced on sand. By eliminating the water resistance, these mostly three-wheeled vehicles reach speeds of up to 130 km / h (for comparison: a sailing dinghy rarely reaches over 20 km / h).

With wind skating , the sail is attached to a longboard and can be driven ashore on smooth surfaces.

See also

literature

Textbooks for beginners

- Roland Denk: Learning to sail with questions and answers . Delius Klasing , Bielefeld 2003, ISBN 3-7688-1480-7

- Roland Denk: Right sailing . BLV, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-405-16234-3

- Peter Günzl, Markus Brandstötter, Ronald Höfer: Sailing: The new course. Orac, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-7015-0454-7 (Austrian BFA inland)

- Heinz Overschmidt, Ramon Gliewe: sports boat license, inland sails, engine . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2004, ISBN 3-7688-0657-X (German SBF inland )

Standard works

- Thomas Bock (staff), Petra Krumme (editor): seamanship. Yachting manual . 30th edition. Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-7688-3248-9 .- Published since 1929 with changing employees by the German High Seas Sports Association "Hansa" , initially with the subtitle "Handbook for Sailors (and Motorboat Drivers)", since the 13th edition 1969 as "Handbook for Yachting".

- Roland Denk: Sailing Guide . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2004, ISBN 3-7688-1556-0

- Bobby Schenk : Cruising sailing . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2003, ISBN 3-7688-1426-2

- Malte Philipp: Regatta sailing . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-7688-1602-8

- Peter Bruce, Adlard Coles: Heavy Weather Sailing . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2000, ISBN 3-7688-1240-5

Lexicons and dictionaries

- Joachim Schult: Sailors Lexicon . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld - Various editions since 1977, e.g. B. 13th edition 2008, ISBN 3-7688-1041-0

- Roland Denk: Sailing Lexicon . With 1389 technical terms. BLV-Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich, Bern, Vienna 1974. ISBN 3-405-11346-6

- C. Doberman: The dictionary of water sports English German / German English . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 1987, ISBN 3-7688-0505-0

Sailing magazines

- palstek - technical magazine for sailors . Palstek, Hamburg 1.1985 ff. ISSN 0936-5877

- segeln - The magazine for sailors . Year Top Special, Hamburg 1971 ff. ISSN 0342-7528

- marina.ch - The nautical magazine of Switzerland, Los media GmbH, Bern 2007 ff.

- Yacht . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 1.1904 / 05 ff. ISSN 0043-9932

- yachtrevue - Austria's magazine for water sports . NEWS, Vienna 1.1977 ff. ISSN 1013-7823

Web links

Associations

more links

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Kühl: Yacht building and yacht sailing . Salzwasser-Verlag, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-86195-587-0 , p. 388 (reprint of: 1st edition, Wedekind, Berlin 1910).

- ↑ Jens Ruppenthal: How the sea lost its horror: Measurement and appropriation of the maritime natural space in the German Empire . In: Alexander Kraus, Martina Winkler (eds.): Weltmeere: Knowledge and perception in the long 19th century . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-52531-713-6 , pp. 215–232, here p. 229.

- ↑ Max Vinner: Boats of the Vikingshipmuseum. Vikingeskibmuseet, Roskilde 2013, ISBN 978-87-85180-63-6 .

- ↑ Sportseeschifferscheinverordnung: SportSeeSchV