Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

| Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370) | |

|---|---|

|

The Malaysia Airlines Boeing 777-200ER with the registration number 9M-MRO at Paris-Charles-de-Gaulle Airport , 2011 |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | reason unknown |

| place | last civil radar contact: 7 ° 1 ′ 12 ″ N , 103 ° 40 ′ 48 ″ E last military radar contact: 6 ° 35 ′ 52.8 ″ N , 96 ° 17 ′ 38.4 ″ E |

| date | March 8, 2014 |

| Fatalities | 239 (officially declared dead) |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 777-200ER |

| operator | Malaysia Airlines |

| Mark | 9M-MRO |

| Departure airport |

Kuala Lumpur Airport , Malaysia |

| Destination airport |

Beijing Airport , People's Republic of China |

| Passengers | 227 |

| crew | 12 |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

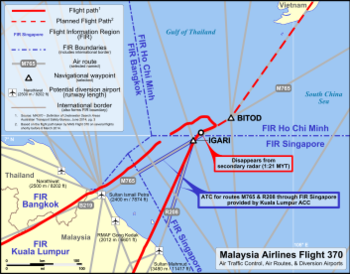

Departure and destination airports and the last known position of flight MH370 |

The Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 ( flight number MH370 and via code share with China Southern Airlines CZ748 ) was an international scheduled flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing , where a Boeing 777 of Malaysia Airlines on March 8, 2014 at 01:21 local time from monitoring of the air traffic control of the Subang airport disappeared. The plane has been missing since then.

After the authorities initially assumed a plane crash in the Gulf of Thailand , it became known in the course of the following days that the plane had apparently changed course and was still sending automatic signals to a satellite up to seven hours after it had disappeared from civil air surveillance . The satellite connection was temporarily interrupted, but about an hour after the disappearance, the aircraft logged back into the ground station. The flight accident investigators assume that the communication systems were switched off at the border with Vietnamese airspace and that a person on board first steered the aircraft back towards Malaysia , then along the Thai border and around the island of Penang across the Strait of Malacca . The aircraft then orbited Indonesia and presumably continued to fly on autopilot in a southerly direction over the Indian Ocean until the flight ended west of Australia . Based on circumstantial evidence, the investigators believe it is likely that the aircraft crashed into the ocean without a driver after the fuel ran out; the search area was narrowed down with this assumption. There was great confusion for hours in air traffic control in the countries involved, and it remains unclear to what extent the Malaysian military, which in any case remained inactive, was informed of the incident.

The final report was published on July 30, 2018. Together with this report, the French authorities' analysis of the flaperone , which was discovered by chance on July 29, 2015 as the first piece of debris, was released after years of delay. The analysis of the damage at this flap wings suggests it that MH370 was not at the time of the crash is under the control of a pilot.

Despite the most expensive search operation in the history of aviation, with costs of almost 150 million euros, the wreck and the flight recorder have not yet been found. Numerous states took part in the search, which initially focused on the waters bordering Malaysia and, from March 17, 2014, on the southern Indian Ocean. Since then, Australia coordinated the search for the missing plane. By April 28, 2014, 4.5 million km² of sea surface had been searched before the search for floating debris was discontinued due to insufficient prospects of success. From May 21 to November 5, 2014, a sea area of 150,000 km², calculated using the satellite and radar data, was mapped in order to prepare an extensive deep-sea search for the wreck using sonar and underwater vehicles. This deep-sea search began on October 6, 2014 and was discontinued on January 17, 2017, after 120,000 km² of seabed had been searched. The private company Ocean Infinity signed a contract with the Malaysian government on January 10, 2018, to search for the wreck in the area further north on the basis of payment only in the event of success (no cure, no fee) . This search began on January 21, 2018 (CET) and was also discontinued with an announcement on May 29, 2018, without any evidence of the wreck being discovered.

Since the main wreck has not yet been located, flight MH370 is the only modern jet aircraft missing to date that was carrying passengers at the time of the accident. In addition, no physical evidence has been found of some commercial aircraft to date , but a large-capacity jet that was carrying passengers at the time of the accident was never thought to have disappeared for so long. It was not until July 29, 2015, 508 days after the disappearance, that a first piece of debris washed up was found by chance. The historically longest search to find the first pieces of debris from a passenger jet took ten days on Adam Air Flight 574, which crashed in 2007 .

For Malaysia Airlines, the incident was the worst accident to date, before the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight 17 over Ukraine four months later cost even more lives. So far no official cause for the disappearance of flight MH370 has been given. It is considered one of the greatest puzzles in aviation history.

plane

The aircraft of type Boeing 777-200ER with the air vehicle registration 9M-MRO and serial number 28420 was equipped with two engines of the type Rolls-Royce Trent 892 equipped. It offered space for 282 passengers (35 in Business Class, 247 in Economy Class) and had a range of around 12,800 km. The machine was delivered on May 31, 2002. She was therefore not particularly old at the time of the incident, at eleven years and nine months. The left engine was newer than the right, and the engines had different fuel consumption. The registration certificate had to be replaced in 2006.

The machine was subjected to an A-check on February 23, 2014 , during which no abnormalities were discovered. The aircraft has completed over 53,400 hours of operation and 7,526 flights. However, the aircraft was involved in an aircraft accident on August 9, 2012 when it collided with the tail of another aircraft while taxiing at Shanghai-Pudong Airport , causing the right wing tip to tear off.

Passengers and crew

| nationality | number |

|---|---|

|

|

152 |

|

|

50 |

|

|

7th |

|

|

6th |

|

|

5 |

|

|

4th |

|

|

3 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

| Total (15) | 239 |

|

1 of which 12 crews 2 used stolen passports of an Italian and an Austrian 3 initially listed under mainland China , |

|

There were twelve crew members and 227 passengers from 15 nations on board.

The crew of twelve consisted entirely of Malaysians. The 52-year-old flight captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah has worked for Malaysia Airlines since 1981 and is very experienced with over 18,000 flight hours. As an examiner, he was authorized to conduct flight simulator tests for pilots. The 27-year-old first officer Fariq Abdul Hamid had been with Malaysia Airlines since 2007 and had 2,813 flight hours. This flight was the first officer's first flight on a Boeing 777 after successfully completing his type retraining, i.e. the first flight without an additional co-pilot trainer. The captain was the first officer's trainer on this flight.

Around two thirds of the 227 passengers were citizens of the People's Republic of China . Among them were a group of 19 artists who was on his way back from an exhibition of their work in Kuala Lumpur, and a well-known kung fu - Stuntman . 38 passengers came from Malaysia. Passengers also included 20 Chinese and Malaysian Freescale Semiconductor employees .

The passengers also included two young Iranians who were traveling with stolen passports. They provided the identity of an Austrian or an Italian whose passports had previously been stolen in Thailand . The two people had connecting flights from Beijing to Amsterdam and from there onward flights to Frankfurt am Main and Copenhagen . Also because the flights of the two had been booked by a third party in a Thai travel agency and paid for in cash, a terrorist background was initially considered. However, just a few days after the machine went missing, the international police organization Interpol announced that it was apparently only illegal immigrants. Interpol expressed incomprehension about the fact that the two passengers could get on board , although the passport thefts were stored in the Stolen and Lost Travel Documents Database .

There were contradicting statements about whether other people with false passports were on board. The director of the civil aviation authority said on March 10 that there were concerns about five passengers who had not flown. The head of the Malaysian police, however, said the following day that all passengers who had booked the flight flew with them and that the possibility is being checked whether a syndicate has provided the two stolen passports. A Chinese citizen whose passport number matched that of a passenger with a different name on the passenger list never boarded the plane, the Chinese police discovered.

At the end of May 2016, it became known for the first time that numerous Malaysian officials at Kuala Lumpur airport, possibly linked to a people-smuggling syndicate, had repeatedly sabotaged the electronic passport verification system. The computers were also hacked from the outside, you could see this by moving cursors . These manipulations and system crashes, in which the passports were only manually stamped, had continued since 2010. It was only in July 2014 that an electronic system for comparing passport numbers with Interpol was introduced in response to the security deficiencies at MH370.

Flight history

Regular flight phase and break in communication

The aircraft took off on March 8, 2014 at 12:42 a.m. local time (4:42 p.m. UTC on March 7, 2014) from Kuala Lumpur International Airport . It should have arrived at the destination airport in Beijing, 4350 kilometers away, around 06:20 a.m. (same time zone, 10:20 p.m. UTC). Before departure, the captain of MH370 had requested the usual amount of fuel of 49,100 kg for the flight, which corresponds to a maximum flight time of a good seven and a half hours. Two minutes after permission to take off, he was requested by air control to give up the standardized departure route and fly directly to waypoint IGARI. At around 01:01 a.m., the cruising altitude of 10,700 meters (35,000 feet) was reached according to a radio message.

At 01:07 the last ACARS report of the current aircraft data (which showed nothing unusual and a normal flight plan to Beijing) was sent to the ground station. The next transmission should have been at 1:37 a.m., but it did not take place. ACARS sends position and status reports at intervals as well as error messages or reports about incidents, such as switching off the transponder or flight plan changes, in real time. Seconds after the last ACARS transmission at 01:07, the master reported the cruising altitude for the second time within a few minutes without being asked and received a radio confirmation from the ground. When the half-hourly ACARS report failed to appear, the Malaysia Airlines control center should have contacted MH370 via text message or satellite call. The repeated announcement of the cruising altitude is an anomaly, which does occur occasionally and the cause of which could not be clarified. However, once the cruising altitude has been reached, it is basically possible for one of the pilots to be able to leave the cockpit.

" Goodnight Malaysian 370 " were the last words transmitted by radio to the Malaysian air traffic control in Kuala Lumpur from the cockpit at 01:19:30, spoken by the captain, who communicated with the ground from the start. According to the airline's regulations, the first officer takes over the radio communication during taxiing and transfers it from take-off if he has been assigned the role of pilot flying. A voice analysis showed that the captain was not under stress or worried. Immediately beforehand, he had been asked to contact the Vietnamese control center in Ho Chi Minh City . In doing so, he did not confirm the radio frequency previously communicated.

A few seconds after the aircraft had flown over the IGARI waypoint, the Mode S symbol initially disappeared at 1:20:36 a.m. and the MH370 position symbol at 01:21:13 a.m. from the secondary radar of air traffic control in Kuala Lumpur. At about the same time (no later than 1:22 a.m.) the disappearance of the position symbol was also recorded by the secondary radar in Vietnam (on the island of Con Son in the south) and in Thailand, as well as by the military radar. It later turned out that this was a consequence of the inactive transponder, which can be switched off from the cockpit. A Malaysian military radar showed that at this point in time the machine initially continued to turn right in the direction of the next planned waypoint BITOD, but immediately thereafter turned constantly to the left. At that time the weather was unremarkable and almost cloudless.

A simulation of this turn showed that it was flown manually and with a very steep bank angle ( roll angle ) of 30–32 °. The autopilot was then reactivated. This maneuver can be carried out by one pilot alone.

Flight over the Strait of Malacca

It was not until March 15, 2014 that it was confirmed that after the transponder signal had gone out, an unknown flying object had left traces in the radar data of the Malaysian armed forces , which were to be located in the northern Strait of Malacca with flight direction Andaman Islands . By comparing them with satellite data from Inmarsat , these radar traces could be clearly assigned to flight MH370. Previously, the Malaysian military had only said that there was a possibility that MH370 was reversed. On March 18, ten days after the plane disappeared, a spokesman for the Thai Air Force said that an unidentified plane heading for the Straits of Malacca was also detected by the Thai radar in the period in question (from 1:28 a.m.). Since it was moving outside of Thai airspace, nothing further was done. This information was initially not passed on because no one was asked about it - although the search could have been delayed as a result. The last sighting by Malaysian military radar was finally 02:22 from Penang , Malaysia, when the signal ended “abruptly”, soon after the waypoint MEKAR. With the publication of the interim report on March 8, 2015, it was also announced that the machine had appeared four times in the surveillance room of the civil primary radar in Kota Bharu . The assignment to individual radars is not always clear in the report.

The Malaysian defense minister, acting minister of transport and cousin of the prime minister, Hishammuddin Hussein , complained on March 19 that not all of the countries in question had yet made their radar records available. The interim report dated March 8, 2015 states that the Indonesian military in Medan did not provide any information on the question of whether MH370 was sighted after the U-turn, although the aircraft entered the airspace of Indonesia after the alleged southern turn. The Indonesian radar data could therefore have excluded or confirmed the assumption of a southern flight route. In the days after the disappearance, the Indonesian military had declared that they had not discovered the aircraft in Banda Aceh in the north-west of Sumatra or in Sabang on the offshore northernmost island of Weh "over Indonesian territory". A little later, however, a spokesman for the Indonesian Ministry of Security said it was possible that the plane was traveling west over the Andamans and only flew south outside of the radar detection. It is possible that the two radars were switched off that night, but the spokesman described this as a "rumor". In contrast, the Indian radar on the Andaman and Nicobar archipelagos is not continuously in operation and may have been switched off at this time.

A senior Malaysian official told CNN on April 6 that the analysis of the radar data from neighboring states led to the conclusion that the aircraft had moved north of Indonesian airspace before it turned south. This could have been done with the intention of avoiding the Indonesian radar. However, Hishammuddin Hussein said this was "untrue". It is therefore unclear when exactly the aircraft flew south. The frequency shifts of the satellite communication at 18:40 were initially understood to mean that it must have flown south before this time. But they can also be explained by a descent at this time. In this case, MH370 could have crashed northeast of the search area calculated by the ATSB.

A British sailor whose yacht was near Banda Aceh, northwest of Sumatra at the time in question , reported to the Australian Coordination Center in May that she may have seen MH370 at about half the height of conventional airliners. If the observation is correct, she may be the last person to see MH370.

During this phase, the aircraft moved conspicuously along existing flight routes or waypoints used in civil aviation and changed direction in the process. According to a report by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau ( ATSB ) on June 26, 2014, it was flying west near the VAMPI, MEKAR, NILAM and possibly IGOGU waypoints around the time it disappeared from waypoint IGARI. In contrast to this, media reports from March 14th assumed that it had moved north from VAMPI in the direction of the GIVAL waypoint and from there north-west in the direction of the IGREX waypoint, which leads to Europe. In the final report, the ATSB finally stated that MH370 had flown through four more waypoints or flown close to them on the way to Penang. A flight segment on the airway N571 to VAMPI is (meaning Emirates flight 343) through the route of another aircraft, the 33 nautical miles behind MH370 was even documented exactly. The changes in direction were probably made by reprogramming the flight computer into which these waypoints can be entered.

With the advance publication of a study on behalf of the Australian government, it became known at the end of 2015 that Australia only had the digital radar recordings available until 02:01:49 a.m. with coordinates and altitude information continuously at 10-second intervals when the aircraft was heading towards the waypoint VAMPI moved. For the subsequent course of the flight, there is only a report on a position indication at 02:22:12, which is considered to be inaccurate due to the distance vision technology. However, a recording leaked to the press , which was presented to the relatives on March 21, 2014 in the Lido Hotel in Beijing, shows this penultimate and last radar blip as well as other blips between the waypoints VAMPI and MEKAR with time stamps. A high-ranking ATSB employee speculated that there were no digital recordings for the course of the flight after 6:01 p.m., but perhaps only video recordings or snapshots. According to the final report, continuous data from the Malaysian military radar is available until 02:03:09 a.m., then again from 02:15:25 a.m. to 02:22:12 a.m. This information contradicts the picture shown in the Lido Hotel.

It is also assumed that the machine changed speed and altitude several times during this flight phase. The reliability of the altitude information is considered to be limited, however, since the presumed changes in flight altitude were not transmitted via transponders , but were measured by military and civil primary radars, some of which were far away . In contrast to very exact values for the horizontal position, even minor atmospheric effects clearly distort the measured flight altitude of a detected object. First, the New York Times reported on March 15, 2014, citing American officials who viewed the radar records that, according to the military radar, the machine made a significant change in altitude shortly after it disappeared and rose from the original 10,700 to 13,700 meters - clearly higher than permitted for this type of aircraft. After the U-turn, it then dropped rapidly and unevenly over Penang to an altitude of about 7,000 meters, well below the normal cruising altitude . The data on the altitude of the aircraft are also unreliable because the radar was not precisely calibrated to the temporary atmospheric conditions. Therefore, the assumption of an uneven descent was later doubted, rather the machine is said to have flown undamaged and controlled. The official interim report made only punctual information on the flight altitude based on data from the civil primary radar, namely that the MH370 was only slightly above the original cruising altitude at 01:30 a.m. and lost altitude discontinuously in the next 10 minutes and also flew significantly faster than before Disappearance (up to 529 kn above ground, measured at 1:39:59 a.m.). The Australian agency ATSB responsible for the search discarded the altitude information from the military radar (between 5,000 and 50,000 feet) because it is incompatible with the speed of MH370 and uses an altitude of 9,150 meters (30,000 feet) to calculate the fuel consumption during this phase . A study carried out on their behalf came to the conclusion that the aircraft was traveling a little lower and faster until the penultimate radar sighting at 6:02 p.m., and later a little higher and slower again.

According to press reports, an alleged contact with the co-pilot's mobile phone was recorded in Penang during this phase of the flight . The co-pilot is said to have switched it on again after having switched it off in accordance with regulations before departure, and thus possibly tried to make a call. Calls from people on the aircraft, however, were not registered. Hishammuddin Hussein denied these reports. It was not until the final report of the ATSB from October 2017 that this information was officially confirmed for the first time. The device's access to the network was registered by a cell tower on Penang at 01:52 a.m., about 30 minutes after the aircraft had left the intended route.

Suspected flight in the direction of the southern Indian Ocean

From March 13, 2014, the first press reports announced that the plane southwest of the Indonesian island of Sumatra had apparently changed direction again and had then continued to fly for hours. In a statement on March 15, 2014, Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that it would have arrived in Beijing at 8:11 a.m. on March 8, 2014 (00:11 a.m. UTC), more than an hour after the plane was scheduled to arrive in Beijing that a complete handshake of the aircraft with the ground station was carried out via a satellite. This means that the ground station sent an automatically generated hourly request to the satellite data unit of the aircraft, which was automatically replied by the latter. However, this does not allow the aircraft to be precisely located. According to the transit times of the signal (BTO values), the aircraft was in one of two " corridors " at this time . The northern corridor extends over northern Thailand to Kazakhstan, the southern one leads over Indonesia to the open sea of the southern Indian Ocean .

Late in the evening of March 24th, the Prime Minister announced that a refined analysis of the satellite data had revealed that the flight of the lost Boeing 777 in the southern Indian Ocean, west of Perth , had ended. From the last opened position there was no longer any possibility of landing.

To determine the course, the frequency shift caused by the Doppler effect in the signals emitted by the aircraft was measured (BFO values); from this the movement of the machine relative to the satellite could be determined. The additional storage of the frequency shifts was introduced by the operator Inmarsat following the accident on Air France flight 447 , as it was very difficult to locate the wreck even then. The satellite connection is used to transmit, among other things, the ACARS data, which, however, were no longer sent. A comparison with the signals from other B777 aircraft and their Doppler effects revealed the southern corridor to be the only plausible possibility of origin. The respective distances to the satellite were known from the BTO values of a total of five complete handshakes . These handshakes or pings were generated automatically by the ground station to test the availability of the connection. The hourly timer was reset by two satellite phone calls made . Since the two calls were transmitted over different channels, no BTO values are available for them. However, there are BTO values for the logon initiated by the aircraft from 02:25 local time (18:25 UTC).

The analysis of this data was continued in the following months and the alleged crash area was relocated several times. On the basis of this data it cannot be clarified where exactly MH370 is to be located on the seventh arch line, so that there is an extremely large area. The incomplete handshake at 08:19 a.m. local time (00:19 a.m. UTC), more precisely a logon from the aircraft, was later interpreted to mean that the fuel had run out at this point and the satellite connection had failed, but was restarted automatically by emergency power has been. The analysis was carried out by investigators from various countries and has led to a scientifically appraised publication by Inmarsat employees, in which the mathematical principles are presented. A basic assumption for the southern search area was that the autopilot was deliberately programmed to a straight line into the southern Indian Ocean. The former northern search area was chosen on the assumption of a continuation flight after completing a certain flight route, which does not fit well with the first ping rings. A balancing position is the Inmarsat hotspot ( 34 ° 42 ' S , 93 ° 0' O ), which assumes that the first waypoint ISBIX was southwest fly Sumatra. At the time of the accident flight, the Australian over-the- horizon radar JORN was not in operation.

End of flight theories

In order to narrow down the search area, the ATSB assumed on the basis of a simulation that the aircraft, after running out of fuel, began to descend more and more steeply and thus crashed near the seventh arc line. Under pilot control, however, the aircraft could have glided up to about 230 km beyond the seventh arc line. Initially, up to 40 km to the left and 60 km to the right of the arch line were searched for. The area was later expanded to 75 km (40 nautical miles ) in both directions.

On the basis of an analysis by Boeing of the last, incomplete handshake , the ATSB also assumes that the satellite data unit was again supplied with power from the auxiliary power unit (APU) after both engines failed and therefore logged back into the ground station. Accordingly, the right engine failed first, and the aircraft could not have been higher than 29,000 feet afterwards. 15 minutes later, at 8:17:30 a.m., the left engine also failed, with the result that the auxiliary engine and ram air turbine started. Since the auxiliary power unit only provides electricity for about two minutes and the electrical systems for the hydraulic control then fail, the scenario of a controlled splashdown is unlikely. In contrast to the previous logon (from 02:25 a.m.), there was no longer any message from the flight entertainment system that would have been expected at 08:21:06 a.m. Either this was switched off from the cockpit, the auxiliary power unit went out, the aircraft had already crashed or, due to an unusual flight position, was already outside the line of sight of the satellite.

The assumption of a steep fall is supported by the Doppler effect value of the satellite signal during the last incomplete handshake , as this indicates a fast vertical direction of movement. However, at least the last of the two values is considered to be possibly distorted by the logon process. The frequency shifts of these two BFO values were compared with previous data from 9M-MRO. The international team of investigators found that the shifts were caused by the warm-up phase of the oscillator . Other factors are the error tolerance of the BFO values and the unknown direction of the aircraft. Despite these uncertainties, the rate of descent for the first BFO at 8:19:29 a.m. can be narrowed to 3,800 to 14,200 and that of the second at 8:19:37 a.m. to 14,600 to 25,000 feet / minute. An examination of the two well-preserved right wing flaps (see below) showed that the outboard flap was very likely retracted in the wing and the flaperon was probably in a neutral position. This suggests an uncontrolled crash.

In a book published in May 2018 (MH370: Mystery Solved) , retired Canadian aviation accident investigator Larry Vance argues that the ATSB withheld important information about the damage to the wing flaps in order to maintain the initial assumption of an uncontrolled crash. In his opinion, if served at high speed, the right flaperon and outboard flap would not be as well preserved. The erosion damage on the two trailing edges also suggested that both flaps came into contact with the water in the landing configuration after the engines initially fell off. Neither piece of debris showed any characteristic features that could speak for flutter damage , with which the proponents of the theory of an uncontrolled fall want to explain the condition of the flaps. Instead, the damage pattern is characteristic of extended flaps and horizontal wing position when in contact with the water. Other debris, such as the fragments of the tail fin and tail units, as well as the parts from the interior do not support the thesis, but can also be explained by the fact that the tail unit was hit by debris and parts were washed out of the interior. The last incomplete handshake was not caused by the end of fuel, but by an unknown manual intervention by the pilot in the electronics. At a hearing in the Australian Senate, Peter Foley, who had led the unsuccessful search by the ATSB, ruled out that the wing flaps were in land configuration, but he did not disagree with the possibility that MH370 could touch the water in a controlled and horizontal wing position and sit down so explain the damage to the flaps. A splash down before the end of fuel and with functioning hydraulics, as would be expected from a professional pilot, is, however, very unlikely in view of the reboot and the Doppler values.

The damage analysis of the Direction générale de l'Armement (DGA), which was only released on July 30, 2018, and which examined the flaperon on behalf of the French judiciary (the written version dated July 26, 2016), comes to similar results. The French investigators believe they can rule out the possibility that the flap separated from the wing due to flutter during the flight , since in this case the leading edge would have hit the water first and would have to be significantly more damaged. However, since the lower surface of the trailing edge was pushed upwards, it is obvious that this area may even hit the water first in the extended position for landing and the flaperon broke off the wing at the leading edge . The authors criticize the fact that Boeing was not ready to provide sufficient data to finally confirm this hypothesis. This declaration assumes that the aircraft was under the control of a pilot at the time of the crash. The newspaper Le Monde had already reported on this on September 4, 2014, when the French victims' relatives were informed of interim results. The captain of a Boeing 777 in the Asian region and instructor Simon Hardy (who wants to see an emotional farewell to the hometown of the captain of the MH370 at Penang) considers it possible that the pilot of MH370 intercepted the aircraft after the last satellite connection, transferred into a gliding flight and in this way could have covered up to about 100 nautical miles.

The final report casts doubt on the assumption that the flaperon was deployed for ditching, since since then the other findings described above have been added, which show that the flaps were not in the landing configuration. Rather, joint damage to the flaperon and outboard flap indicates that both were aligned in the same way. Nevertheless, the debris from the interior also indicates that the aircraft was breaking apart, either on impact with the water or still in the air, with none of the debris showing traces of explosives.

Air traffic control reactions

The immediate reactions to the loss of radar and radio contact have led to criticism of the Malaysian authorities as well as to legal battles by relatives . The processes have not yet been investigated or clarified, but the rough timing is known. The communication protocols of the air traffic controllers at the air traffic controls involved were published in the interim report of March 8, 2015. Information from the control center of Malaysia Airlines and logbook entries from the duty manager of the Malaysian air traffic control in Kuala Lumpur had already been summarized in the first preliminary report . The responsible department was understaffed between midnight and 6 a.m., at 3 a.m. there was a change in staff. The emergency was only declared while the new controller was on duty. He was apparently barely informed about the incident.

An initial request from the Vietnamese air traffic control in Ho Chi Minh City about the whereabouts of the aircraft was made at 1:39 a.m., i.e. not, as prescribed, within five minutes of handover. Ho Chi Minh City had previously tried unsuccessfully to contact the plane by radio and also asked planes nearby to do so without receiving a response. According to the air traffic controller's statement, MH370 disappeared at waypoint BITOD (in Vietnamese airspace), this error was only cleared up at 05:20. At 01:41 a.m., Kuala Lumpur tried to reach MH370 without success, but the superior on duty did not trigger an alarm phase (uncertainty phase) , through which the air traffic control of neighboring countries would have been informed of the missing aircraft , as prescribed . At 02:03 a.m., Malaysia Airlines control center sent a text message to the aircraft via ACARS, requesting it to contact Ho Chi Minh City. The uplink of the message was immediately displayed as interrupted because the connection with the satellite data unit was not working at the time . The further attempts that were carried out automatically at two-minute intervals for the next 40 minutes also remained without an answer. The automatic downlink message from ACARS to the ground indicated "failed". In the interim report, however, the ACARS protocol from the network provider SITA only lasts until 02:15 a.m., in the Inmarsat data only two such attempts are recorded, probably because the connection is automatically logged out. In any case, from 02:25 the satellite connection to the aircraft was available again. Only after the publication of the final report did it become known, on the basis of previous independent investigations, that the Ministry of Transport had suppressed a second message sent by the Malaysia Airlines control center in all reports. This message was sent around 02:39 am and read: “Dear MH370, please confirm the test message. Regards Operation Center " (DEAR MH370. PLS ACK TEST MSG. RGDS / OC)

If radar or radio contact is lost, it is mandatory to clarify which country is responsible for initiating further measures. Nevertheless, at 02:04 a.m. in Ho Chi Minh City, Kuala Lumpur reported from the Malaysia Airlines control center that the aircraft was over Cambodia and thus outside of Vietnamese airspace. Ho Chi Minh City then contacted air traffic control in Cambodia, which stated that the plane was not in their airspace. At 02:06 the ACARS position report reported that the aircraft was not logged into the satellite system. Nonetheless, at around 02:15 a.m., the Malaysia Airlines control center confirmed to the line manager in Kuala Lumpur that MH370 was in Cambodia, as noted in its logbook, and indicated that a signal exchange was taking place. At 02:19 a.m., Ho Chi Minh City confirmed, at the request of Kuala Lumpur, that the intended flight route of MH370 should not go through Cambodia but through Vietnam. It remains unclear whether the subsequent request reached Malaysia Airlines. At around 02:35 a.m., i.e. 10 minutes after the satellite connection was back, Malaysia Airlines confirmed at the request of the supervisor in Kuala Lumpur that the text message had reached the aircraft, that it was still sending a position report to the airline and transmitting the coordinates Aircraft was located on the intended route in northern Vietnamese airspace). Kuala Lumpur asked Malaysia Airlines to contact MH370 via satellite phone and then to report back. Immediately afterwards, Kuala Lumpur passed the coordinates on to Ho Chi Minh City, where the information was checked and later Kuala Lumpur was informed that the plane could not be contacted. At 2:40 a.m., Malaysia Airlines called the cockpit for the first time. Since the satellite connection was working again since 02:25, the call was put through but not answered. At around 3:30 am, Malaysia Airlines informed Kuala Lumpur that the position report was based on a forecast of the planned flight route in Flight Explorer and was "not reliable" to determine the position of MH370. This is also noted in the manager's log. At 3:56 a.m., the Malaysia Airlines control center informed the new Kuala Lumpur air traffic controller that there was no news yet, but they wanted to try to contact the aircraft. It is unknown whether Malaysia Airlines ever informed air traffic control or any other authority that the two ACARS messages failed and the call went through but was not answered.

Military sources told Reuters that the Butterworth military base in Penang (on the Malaysian west coast) was informed by civilian air control in Kuala Lumpur around 2 a.m. that the plane was missing. Based on the information provided by Kuala Lumpur, it was assumed that it had technical difficulties and was therefore on its way to an airport. A corresponding flying object was discovered on the military radar. Since it was rated as “not hostile”, nothing was done. It flew out over Penang Airport and out to sea after previously flying over Kota Bharu Airport on the east coast.

At 5:09 a.m., the Singapore control center inquired on behalf of Hong Kong about the absence of MH370 in Chinese airspace. In response to a telephone request from Kuala Lumpur at 5:20 a.m., the Malaysia Airlines control center reported that, given the last radio contact, MH370 had never left Malaysia airspace. The air traffic controller in Kuala Lumpur, who started work after 3 a.m., confirmed this message. He also announced that he would wake up his supervisor to check when the last contact took place. Ho Chi Minh City had already tried unsuccessfully to speak directly to the supervisor at 4:25 a.m.

The then head of Malaysia Airlines, Hugh Dunleavy , said in an interview that he received an emergency message around 4 a.m. and then went to the control center in Kuala Lumpur. In the first few hours, all those responsible at Malaysia Airlines assumed that the plane had been deflected off course and continued to fly for hours, but not that it had crashed. Since there was no communication from MH370, at subsequent meetings with relatives he assumed that there was no kidnapping case in which the government was negotiating with a kidnapper.

Air traffic control in Kuala Lumpur activated the rescue coordination center at 5:30 a.m., more than four hours after disappearing from the radar screen (the search was coordinated by the military). From there, an hour and two minutes later , the emergency was broadcast via the Aeronautical Telecommunications Network , an international network of air traffic controls in the individual countries. The relevant document from the Rescue Coordination Center received from the Civil Aviation Authority did not contain an official stamp. The first Malaysian rescue plane took off at 11:30 a.m. According to regulations, the rescue coordination center should have been informed by the line manager on duty within three minutes of the arrival time in Vietnamese airspace (01:22 a.m. planned or 01:21 a.m. actually) and the military should also have been contacted.

After the plane missed the scheduled arrival in Beijing at 06:20 a.m. local time (22:20 UTC), the supervisor in Ho Chi Minh City asked to speak to the supervisor in Kuala Lumpur at 06:36 a.m. in vain. At 6:50 a.m. Singapore also wanted to speak to the supervisor, but he was busy. Singapore also asked for confirmation that Malaysia Airlines are still trying to contact the missing plane. At 7:13 am, the Malaysia Airlines control center attempted to contact MH370 for the second time via satellite phone . At 7:24 a.m., the airline finally published a press release on its Facebook page that MH370 had lost contact with the control center in Kuala Lumpur at 2:40 a.m., i.e. at the time of the first unsuccessful call by the airline, and that a search has now been carried out - and rescue operation had been initiated. At this point in time, MH370 was still in the air and logged into the Inmarsat satellite. The call therefore went through but was not answered.

The final report of July 30, 2018 contains some additional information on these processes, but without providing a complete explanation. The responsible Vietnamese air traffic controller was only asked about the process on September 10, 2014. He had no explanation as to why he did not contact MH370 within five minutes, but stated that he had contacted other aircraft on an emergency frequency which was not supported by records. This may have caused a delay. Nor could he explain why he mentioned waypoint BITOD (in Vietnamese airspace) as a reference point, which led to further confusion about jurisdiction. Kuala Lumpur should have noticed a distress phase and subsequent phases at 2:27 when the notification from Vietnam was made, but did not do so. At 2:00 am, the responsible radar pilot informed the superior who was in the sleeping and rest room at that time via another pilot. The supervisor then phoned the control center of Malaysia Airlines, where he was told that according to the flight explorer MH370 was over Cambodia. The conversation was not recorded. The supervisor was satisfied and returned to the relaxation room at 2:30 a.m., where he remained until 5:30 a.m. (when the first alarm was triggered). The Malaysia Airlines controller later stated that neither he nor the other staff on duty were sufficiently trained to know that it was just a projection. The MH370 radar blip appeared on the primary radar of the civil aerial surveillance of Kuala Lumpur, but was not perceived in real time. During this time, contrary to the regulations, the responsible area was occupied by people who were insufficiently trained. When the airline announced at 3:30 a.m. that the flight projection was not reliable, Vietnam was responsible. There is no record of Malaysian air traffic control reporting to the military. On the same day, however, the military identified the unannounced radar echo display with MH370 and therefore did not send any interceptors, as the aircraft did not pose a threat.

The day after the final report was published, the Director of the Civil Aviation Authority of Malaysia announced his resignation. The new transport minister Anthony Loke announced an internal investigation.

Search for the machine

Search around Indonesia and Malaysia

The naval forces and sea scouts from Australia , Vietnam , Indonesia , India , Malaysia , Thailand , Singapore , New Zealand , Japan , the People's Republic of China , the Philippines and the United States participated in the search and rescue operation . Both the United States' National Transport Safety Authority , from which three of the passengers on board came from, and the American manufacturer Boeing , which produced the aircraft, had offered their support.

First, the aircraft was searched for in the vicinity of the last radio contact. The Vietnamese Navy had reported that the aircraft had crashed about 280 km from the Thổ Chu Islands over the Gulf of Thailand (between Malaysia and Vietnam) or that the signal from the machine had broken off there. However, the Vietnamese Deputy Minister of Transport said that the Vietnamese air traffic control notified the Malaysian authorities of the change of direction on the same day, but received no response. A few hours after the disappearance, the chief of Malaysia Airlines said the aircraft had been captured by air traffic control east of Malaysia by 02:40 a.m. The alleged allegation that a Malaysian military radar had spotted MH370 at 02:40 a.m. near Pulau Perak , an island in the Strait of Malacca, was soon denied by the Malaysian military. However, the Malaysian military informed Defense and Transport Minister Hishammuddin Hussein on March 8 at 10:30 a.m. that according to radar records, MH370 could have flown over the Strait of Malacca . Two ships stationed there as well as an aircraft were asked for clarification.

Objects floating in the sea that had been sighted by reconnaissance or satellites in the area of the suspected crash site could either no longer be found after detailed investigations or could not be identified as belonging to the aircraft. An oil film about 20 kilometers wide in the alleged crash area near the fishing port of Tok Bali in the state of Kelantan turned out to be marine fuel after chemical analyzes of samples .

The sea area to be searched was extended to the Strait of Malacca by Malaysia the day after the machine disappeared, as it now appeared possible that the aircraft had changed course to the west, as the Malaysian military said on March 11th. The People's Republic of China announced on March 10th that it would be participating in the search for the machine with ten satellites equipped with high-resolution cameras. On the same day, the expansion of the search zone was announced. On March 12, a total of 42 ships and 35 aircraft were involved in the search, about a third of them in the Strait of Malacca and the rest in the South China Sea . Since then, the Indian coast guard has also participated and searched the Andaman Sea and the Nicobar Islands . The crowdsourcing platform Tomnod also made current satellite images available; millions of Internet users took part in the search.

Maldivian newspaper Haveeru reported on March 18 that residents of Kudahuvadhoo had sighted a low-flying airliner in colors similar to that of the missing plane about an hour after the alleged time of the crash, the Maldivian military commented on the following day with the statement no indication of a radar echo from MH370 was received in the region concerned, neither from the military nor from the civilian radar of the airports. According to research by Florence de Changy ( Le Monde ) , neither the time nor the direction show any connection with MH370, rather it is said to have been an aircraft of the local airline. According to research by self-financed private investigator Blaine Gibson, however, it could not be clarified which aircraft it was.

Search in the southern Indian Ocean

The Roaring Forties

On March 13, the Wall Street Journal reported that the engines of the missing plane had sent data packets more than four hours after the last radar contact. Although the Malaysian Defense Minister and acting Minister of Transport Hishammuddin Hussein initially denied this report, citing information from Malaysia Airlines, as "incorrect", it later turned out to be partially correct: According to information from the BBC on March 14, 2014, the satellite system of the British company Inmarsat still had Receive automatically generated signals of readiness for communication (so-called handshakes ) from the MH370 up to five hours after the last radar contact . However, these handshakes were not sent from the engines themselves. A spokesman for the Pentagon said on March 14th that the plane could have gone down in the Indian Ocean, the United States wanted to move the search there.

After the last ping signal of the machine from one of the two corridors became known, the search for wreckage in the South China Sea was stopped on March 15, 2014. The search now focused on the regions surrounding the two corridors. In the following weeks the search area was relocated several times after the analyzes of the satellite data had been passed on to Australia . In addition, the search for debris floating on the sea, in contrast to the search for flight recorder signals emanating from the seabed, had to take into account the ocean currents, which are difficult to calculate.

The southern corridor was searched under the coordination of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) . The Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak had asked the Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott to coordinate the search in the southern corridor, as this search area is in the Australian Sea Rescue Area . On 17./18. On March 8th, the People's Republic of China began a systematic search of the corridor on its territory. At that time, a total of 25 countries took part in the search. In the event that the aircraft had flown into the northern corridor, the investigators hoped to obtain further information by analyzing the military radar data of the states that it should have flown over, in particular the People's Republic of China. However, no such evidence was found in the days that followed.

Several aircraft from Japan, South Korea and the USA were unable to take off on their planned search flights because overflight rights for Indonesia were not granted. On March 20, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced that satellite images taken on March 16 about 2,500 miles southwest of Perth in the Indian Ocean show parts of the water that could belong to an airplane. Airplanes, naval and merchant ships from several countries were sent to investigate.

The initially eligible area covered approximately 7.68 million km² and is located in the Roaring Forties , the west wind zone , which is characterized by poor weather conditions, rough seas and strong ocean currents to the east. On March 22nd, a cyclone warning was also given for the search area . The search area was about 2500 kilometers from the nearest mainland (Australia), which made the search difficult. Aircraft operating from Perth , Australia, had to fly in about four hours a day and fly back the same time, so that only about two hours a day were available for the actual search. The seabed of the Indian Ocean is shaped in this sea area by the Indian Ridge , which runs from north to south .

From March 22nd to 27th there were reports almost daily that possible wreckage had been sighted on images from Chinese or Thai satellites and on satellite images provided by Airbus Defense and Space . Australian and Chinese search parties announced on March 24 that they may have discovered wreckage in the Indian Ocean. An Australian rescue ship was heading into the area. On March 25, the search was suspended for 24 hours due to bad weather.

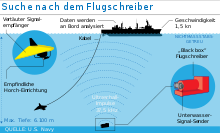

The search for the wreck became a race against time. The flight recorder ("black box") should have been activated after contact with water and should send out ultrasonic signals at regular intervals. The battery capacity of the flight recorder of MH370 should have been sufficient for at least a month. International recommendations that had been drawn up after the crash of Air France Flight 447 in the South Atlantic in 2009, according to which a flight recorder should be active for at least 90 days, had not yet been implemented for MH370. The signal can only be detected from a limited water depth. In the case of greater water depths, the receiver probe must be suspended from an appropriate underwater cable. The range of the signal depends heavily on the conditions of the ground.

The northern search area

On March 28, 2014, the Australian Prime Minister announced that there was evidence that the plane had crashed significantly further northeast and that the search area was being relocated as a result. The new search area was closer to the Australian coast, outside the Roaring Forties, and covered approximately 319,000 km². The international investigation team has analyzed that flight MH370 flew faster between the South China Sea (the last civil radar contact) and the last military radar contact over the Strait of Malacca, thus using more fuel and traveling less far on the southern route than previously assumed. Over 50 objects floating on the sea were sighted that day, only a part of which could be recovered. On March 30, the Australian ship Ocean Shield was finally ordered into the area with a towed pinger locator to track down the flight recorder.

Since April 1, 2014, the Australian Joint Agency Coordination Center (JACC) has been coordinating the search for MH370. It was founded a few days beforehand for this purpose. Under the Chicago Accords , responsibility for the investigation rests with Malaysia, with Australia leading the search for the wreck in the southern Indian Ocean as an accredited member. The British Navy is participating with the submarine HMS Tireless and the survey ship HMS Echo .

On April 5, 2014, a Chinese news agency reported that a flight recorder detector on the Haixun 01 search ship had received a pulsating (sound) signal with a frequency of 37.5 kilohertz, which matched the frequency of the flight recorder on the Boeing 777 ( 25 ° 0 ′ S , 101 ° 0 ′ E ). Apparently the signal was registered by a hand-held hydrophone for a little over a minute. However, a few days later it was ruled out that the signal belonged to the missing aircraft.

On the same day (Australian time zone), another signal was later received from the Australian search ship Ocean Shield , which had meanwhile been ordered to reinforce the Chinese ship, about 300 nautical miles (almost 600 km) away. The reception occurred in the vicinity of the airway M641, of the Cocos according Perth leads. The head of the JACC authority, Angus Houston, described the reception of this signal as “the most promising track so far.” Despite all due caution, the first reception of the Ocean Shield sensor during a turning maneuver at shallow depth lasted 2 hours and 20 minutes, the second reception the return trip (within a radius of approx. 1.5 km) and now at a depth of 3000 m about 13 minutes. On the way back, two different signals were received which “matched the transmissions of the flight data recorder and the voice recorder”. The signals were registered at a frequency of 33.331 kilohertz at regular intervals of 1.106 seconds. As of April 11, 2014, the area in which drifting debris was searched for was newly delimited to 47,000 km².

Two more alleged transmissions were received from the Ocean Shield on April 8th. In order to ensure a trouble-free search, no further ship is used in this area. However, a P-3 Orion aircraft laid out 84 sonar buoys near the Ocean Shield , which could eavesdrop on the ocean at a depth of at least 300 m. Since water-borne sound does not propagate in a straight line but diffusely (depending on numerous factors such as temperature, pressure and salinity), it is difficult to pinpoint the source. It is also assumed that the sea floor is covered with meter-high silt , which can deflect sound waves and hide the wreck. Since the sensor of the Ocean Shield can cover an area six times larger than a diving robot, it is expected that diving robots that can search the ocean floor will only be used when it can be assumed that the flight recorder battery is exhausted. Until then, attempts should be made to limit the area as much as possible. The depth of the ocean floor is estimated at 4500 m. An initially promising signal reception by the P-3 Orion on April 10 could not be confirmed as an additional reference to the flight recorder, but after further analysis was described as "very similar" to the expected signal from a flight recorder. From April 12, the HMS Echo was also in the search area to map the seabed.

After no more signals were detected, the Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott said in Beijing that the signal strength was now rapidly decreasing and that finding at least one of the two flight recorders would be a "daunting task". The resting place of MH370 presumed at that time was the hardly mapped northern edge of the Zenith Plateau on the border with the Wharton Basin .

Underwater search by diving robots

On April 14, Houston, the head was the search teams, announced that now instead of the Towed Pinger Locator of the diving robot Bluefin-21 will used the inserts each lasted 24 hours and the advance in up to 4500 m depth and the seabed using a side view sonar could map. The search for acoustic signals from the flight recorder was thus discontinued. However, an oil spill spotted at the suspected crash site was not found to be aircraft fuel or hydraulic fluid. In the event of failure, a large-scale exploration of the seabed along the suspected flight corridor or the seventh satellite ping arc line was promised for the first time.

Since the Bluefin-21 emerged prematurely on its first use due to a safety lock after the margin line of 4500 m had been exceeded, the device was reprogrammed to penetrate deeper into the ocean "with an acceptable safety risk". The size of the search area was given as a circle with a radius of 10 km.

The search by ship and plane initially continued, but was partially suspended due to bad weather. By April 26, 95% of the area had been searched by the diving robot with no evidence of the aircraft.

Preparation for the deep sea search

On April 28, Tony Abbott and Angus Houston announced that the search was no longer to rescue the wreck but to rescue it (search and recovery) . The search for rubble on the sea will be discontinued, as it should have sunk in the meantime. Up to then a total area of 4.5 million km² had been searched by 29 aircraft and 14 ships. Instead, an extended underwater search is planned, which would cover the entire probable crash zone of 700 by 80 km or about 60,000 km² and could last about eight months. The search is difficult because the entire sea floor in this area is likely to be covered by silt at an unknown height. Tony Abbott said there was still "a considerable degree of confidence" that the signals received were from the flight recorder and so the Bluefin-21 submersible, which had been mapping an area of 400 km² by then, would continue to operate in the area of the received signals used.

After the Ocean Shield had meanwhile returned to Australia to replenish supplies, she left port on May 10th to use the Bluefin-21 to search the area around the first signal received on April 5th. After further analysis, the ATSB is no longer sure whether the last two signals received on April 8th actually came from the flight recorder, so that only the first two signals may be relevant for the search.

After a break due to a defect, the Bluefin-21 diving robot was used again from the Ocean Shield on May 22, 2014 . The Chinese ship Zhu Kezhen also began a mission on May 21 to bathymetrically map the seabed in the region . It served as preparation for a subsequent deep-sea exploration. The mission was necessary to prevent underwater vehicles from crashing. The bathymetric survey data that are of interest to science are to be published in databases, the bathymetric data from search phase I (before the fine search using depth sonar) was published in July 2017. The bathymetric survey led to the discovery of previously unknown geographic features , including underwater volcanoes of 2000 m height.

On May 29, the ATSB stated that the search of the diving robot in an area of 850 km² around the reception of the acoustic signals had been completed and the area could therefore be excluded as a resting place for MH370. The extended underwater search should begin in August 2014 and will be projected for 12 months. In addition, the existing data would be analyzed further. A senior officer in the US Navy, Michael Dean, told CNN that the signals may have been generated by the ship or the tow sonar itself. The final report of the ATSB confirms this statement, according to which a defective cable on board the Ocean Shield generated the signals. At the same time, the report is much more skeptical about the hope at the time that the signals actually came from the wreck.

Two underwater monitors from Curtin University had recorded a sound in the Indian Ocean around the time of the last partial satellite handshake , which may have originated from the aircraft, but is more likely of natural origin and the source of which is also suspected a few thousand kilometers to the northwest. This became known on June 2nd.

On June 10, the ATSB signed a contract with the Dutch company Fugro , which specializes in deep-sea research and which, together with the Chinese ship, was to map the seabed around the seventh ping line of the satellite handshake . Australia estimated the search for MH370 to be the equivalent of around 65 million euros by 2016, with China and Malaysia also promising to contribute to the costs.

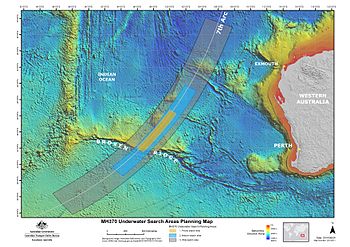

On June 26, 2014, the ATSB submitted a report containing details of the suspected flight route and narrowing the search area for the seabed search. This was defined as an area of 60,000 km², which extended in an arc of 650 km with a width of 93 km northwest of Broken Ridge and was largely identical to the area of the sea surface search of March 28 . It was assumed that the aircraft was steered by the autopilot until the fuel ran out and that the crew was unable to act or did not react in the last phase of the flight towards the Indian Ocean due to a lack of oxygen . There is also the possibility that the autopilot was programmed to cross or traverse flight routes or waypoints that ended at airports in either Australia or the Cocos Islands .

Australia's Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss announced on Aug. 6 that Fugro had also been entrusted with the underwater search for the missing plane. In addition to the two ships provided by Fugro , Malaysia will also participate with four ships. Warren Truss was "cautiously optimistic" about finding the wreck. The search should begin in September 2014, the assumption of costs by Malaysia and other countries is still the subject of negotiations, especially since Malaysia Airlines is still involved in other ways after the alleged downing of flight MH17 . Several companies took part in the tender to search for the machine. Warren Truss and Malaysia's Minister of Transportation Liow Tiong Lai signed a cost-sharing agreement on August 28.

Deep sea search near the seventh arch

On October 6, 2014, the search for the missing aircraft finally entered the announced new phase. The US deep-sea research vessel GO Phoenix began that day to examine the new area for wreckage. The Dutch ships Fugro Discovery and Fugro Equator should also arrive there by the end of October at the latest and support the mission. However, due to technical problems , the Fugro Equator could not start the search until November 21st. The area is extremely rugged. Underwater vehicles were used, which were pulled by the ships and were supposed to use sonar devices, fuel detectors and video cameras to track down signs of the whereabouts of MH370. The ships had enough supplies to each stay at sea for about a month before having to return to port.

On October 8th, the ATSB published a revised report on more recent analyzes of the satellite data and flight simulations, which as a result locates the possible site south of Broken Ridge in the area of the seventh arch. The main reason for this was the evaluation of the BFO values of the first call at 18:40 UTC as indicators of a turn to the south that had already taken place. Alternatively, however, these values can also be explained by a change in the flight altitude at this point in time. The previous search area, which was defined in June, was calculated without this interpretation. The calls themselves contain the frequency shifts (BFO values), but no transit times (BTO values) on the corresponding channel. No further location rings could be generated by these calls. The distances to the satellite are only known for the six hourly handshakes .

The mapping of the sea floor with a total area of 160,000 km² was completed on October 26, 2014 for the deep sea search on the seventh arc. On December 17, 2014, the Australian Coordination Center reported that the ongoing search for wreckage on the sea floor should be largely completed by May 2015, i.e. before the stormy winter months, provided there were no unforeseen delays. The ship Fugro Supporter was sent to the area on January 29 to provide further support . From February 1st to 4th and from March 14th to 16th, the search work was suspended due to cyclone warnings . The GO Phoenix found some objects that could have been created by humans, but hardly resemble aircraft wreckage, but are perhaps shipping containers. A shipwreck was also discovered.

Warren Truss said on March 1, 2015 that the search could not go on forever and that Australia, China and Malaysia are currently discussing whether, in view of the costs, the search in the up to 1.1 million km² area around the can also be carried out after May Priority zone should be continued around. However, on April 16, the participating governments (Australia, China and Malaysia) agreed to continue the search for another year to search an additional 60,000 km². On May 6, it was announced that the underwater search would be suspended for the winter months in the southern hemisphere. Soon after, the Fugro Supporter was withdrawn from the search area. On June 20, the GO Phoenix ended the search in the northern area because their contract was terminated by Malaysia without explanation.

On June 3, the participating governments agreed to end the search if no finds were made in the extended search area of 120,000 km². By then, over 50,000 km² had been searched. It was also announced that the search would generally continue over the winter months.

At the beginning of September a meeting with representatives from Malaysia and Australia took place in Canberra , at which the search operation from the summer months was discussed. The results of the meeting were not disclosed; Chinese representatives canceled despite being invited. At a meeting with Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in November, China's Prime Minister Li Keqiang promised 20 million Australian dollars (around 14 million euros) for the further search for the wreck.

Some objects of medium interest were examined at greater depth by high-resolution sonar at the end of September, as a diving robot could only be used in the summer months. According to the authorities, these did not belong to an aircraft. In November, the search had to be canceled twice due to illness and the Fugro Discovery had to return to port in Fremantle . From November 15, Fugro Equator carried out bathymetric survey work again, as an area was now searched further south and outside the originally surveyed area.

On December 3, 2015, after more than 75,000 km² had been searched, the ATSB published a new report which, based on Bayesian statistics, determined the priority zone in the south of the search area for the remaining 44,000 km². The basis for the calculation was a straight flight course at constant altitude and speed from the southern turn. The search should continue until June 2016. The new area was outside of the hotspot further north , which had been calculated by the British company Inmarsat, on whose data the assumption of the crash in the Southern Indian Ocean was based.

Also on December 3, a new search ship, the Havila Harmony , began to examine particularly inaccessible areas of the sea floor with a diving robot. On December 19, 2015, a find was made by sonar, which was identified by a diving robot on January 2, 2016 as another shipwreck, probably from the 19th century. Further investigations in early 2018 showed that the two wrecks found were the West Ridge and W. Gordon or Magdala - coal freighters that sank in an explosion on board in the last quarter of the 19th century. On January 24, 2016, the Fugro Discovery lost its underwater sonar when the cables tore in a collision with an underwater volcano that towers 2,200 meters above the sea floor. The Fugro Discovery returned to port and prepared a replacement sonar. The lost sonar was successfully recovered by the Havila Harmony two weeks later .

The Chinese ship Dong Hai Jiu 101 left the port of Singapore on January 29 to participate in the search. This ship is operated by the same companies as the previously terminated GO Phoenix . On March 21, the Dong also lost its towed sonar due to a cable break. On April 18, this was recovered with the help of a diving robot . Since May 8th the search with underwater sonar could not be continued due to weather conditions, only on June 15th the Dong could temporarily resume the search work.

At the end of July 2016, Australia, China and Malaysia announced in a joint letter to the relatives that the search would be suspended if no findings were made in the current area. The search could be resumed if credible evidence of the whereabouts of flight MH370 was found.

On August 11th, Fugro Discovery ended the search for MH370. As of November 30, 2016, over 110,000 km² have been searched. The Dong Hai Jiu 101 stopped the search on December 3rd. Due to the weather-related delays, the search was extended to January 2017. Some sonar contacts were clarified more closely by a diving robot. Afterwards, some models of the flaperon (see below) should be exposed with satellite receivers in order to obtain new information about the crash location with the help of long-term drift data.

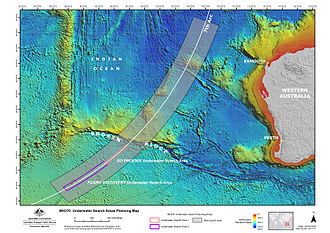

In a report dated December 20, 2016, the ATSB concluded that the search in the estimated area had been completed with at least 95 percent confidence. The assumption of a straight flight path after the southern turn can thus be largely ruled out. The ATSB assumes that a different autopilot mode was set instead, which causes an arc-shaped flight path in increasing proximity to the magnetic south pole. On the basis of drift studies of the debris found and the areas of the sea surface searched for floating debris, the ATSB suspects that MH370 crashed in the former northern search area along the arc line between the 36th and 32nd parallel. This area was partially explored until June 2015 and then abandoned. The assumption of a wider crash area was also called into question again in this report; instead, based on the investigations into the wing flap parts and the last two BFO values, it is very likely that MH370 will reach within 15, at most 25 nautical miles and not, as previously assumed, must have crashed within 40 nautical miles to the left and right of the bow. A special probability arises for the 35th parallel in the immediate vicinity of the Inmarsat hotspot. The search was finally stopped on January 17, 2017. The total cost of this search phase was approximately A $ 200 million, with Australia bearing $ 60 million and China paying $ 20 million, with Malaysia paying the majority. In comparison, the search for Air France 447 only cost 21 million euros. On October 3, the ATSB's 440-page final report on the search for MH370 was finally published.

Resumption of the search through Ocean Infinity

Back in August 2017, the US private company Ocean Infinity , which specializes in deep-sea research, offered the Malaysian government to search for the wreck of the MH370 and only receive a bonus if it was successful (no cure, no fee) . Negotiations have continued since then. The Australian Ministry of Transport announced the continuation of the search on October 19, 2017. The contract was finally signed on January 10, 2018. $ 20 million has been pledged if MH370 is found within the first 5,000 km², for each additional 10,000 km² this sum increases to $ 30 million and $ 50 million. If the wreck is located outside of the 25,000 km² proposed by the ATSB, even $ 70 million will have to be paid. Ocean Infinity should first search the area preferred by the ATSB (around 35 ° S), then that determined by oceanographers at Western Australia University based on drift studies (around 32.5 ° S). If necessary, the search should continue to at least 30 ° S, as interested private individuals and independent experts (IG) coordinated by Victor Iannello see this area as promising based on various considerations. Up to eight autonomous diving robots at the same time should comb the entire area from the Norwegian Seabed Constructor within 90 days of searching .

The search began on January 22nd. Only the times in which the Seabed Constructor operates in the search area count to the 90 search days . The refueling and return to Fremantle cycle is 26 days each. The search should therefore continue until mid-June. By April 8, the Seabed Constructor had searched the three priority areas proposed by the ATSB in a total area of 38,214 km² without success. A remote-controlled diving robot with an infrared camera was used on April 4, but only discovered geological formations, as well as at two other points that were investigated from close up on April 10. On April 17, it was reported that the proposed search zone had been significantly expanded from latitude 29 ° S to 26 ° S. As of May 22nd, a total of 96,200 km² had been searched.

The Barisan Nasional party alliance, led by Prime Minister Najib Razak , lost the Malaysian parliamentary election on May 9, 2018 after Najib was accused of corruption. This is the first time the government alliance has lost power since Malaysia's independence. The election winner and former Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad was sworn in as the new Prime Minister on May 10, 2018. He then fulfilled his election promise to have the sentence against Anwar Ibrahim (issued on the day MH370 disappeared) annulled, so that the way for the successor to Anwar after about two years is free. Mahathir then terminated the contract with Ocean Infinity on May 29, 2018. The designated successor Anwar has announced that it will reopen the case and, in particular, investigate the severely delayed reaction of air control, the military and the airline. Should new clues arise, the search could be restarted. On May 29, 2018, Ocean Infinity announced that the search would expire, also in view of the unfavorable winter weather conditions.

Finds of alluvial debris

Flaperon on Reunion Island in July 2015

On July 29, 2015, almost a year and a half after the disappearance, a resident near Saint-André on the island of La Réunion found an approximately two meter long alluvial wreckage covered on both sides with barnacles ( sessile crustaceans ) during cleaning work . A pilot friend identified it as a possible right wing flap ( flaperon ) of a Boeing 777. Such a component consists mainly of carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) with a honeycomb core made of aramid and is therefore easy to float. The age and origin of the animals were examined on site. The regional newspaper Le Journal de l'île de la Réunion published a close-up of the washed up part, on which the number 657-BB can be seen, which is assigned to the Flaperon Leading Edge Panel of a Boeing 777 according to the Boeing maintenance manual . On July 31, Martin Dolan, the head of the Australian agency responsible for the search, ATSB, said it was "very likely" that the wreckage belonged to the missing aircraft, as no other case of a missing Boeing 777 flaperon was known.

The part of the wreck arrived on August 1st in Toulouse at the DGA Techniques aéronautiques center , where the judicially ordered assessment took place from August 5th. Both Malaysia and Australia had demanded the return of the find, but France refused, as an investigation by the French judiciary had already been initiated in March 2014. Starting in May 2014, an initial suspicion of aircraft hijacking and manslaughter (détournement d'aéronef aggravé par la mort d'une ou plusieurs personnes) and aircraft hijacking in connection with terrorism (détournement d'aéronef en relation avec une entreprise terroriste) was investigated . The background is the death of four French citizens on board the machine. The debris was also found on French territory. In order to clarify whether the part of the wreck belongs to the missing aircraft, representatives of all countries involved in the investigation were flown in.

On August 5, 2015, the Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak confirmed that the international experts had "conclusively confirmed" that the part of the wreckage found belonged to the missing Malaysia Airlines plane. This is physical evidence that the flight ended in the southern Indian Ocean. The Deputy Public Prosecutor of Paris, Mackowiak, spoke of a "very strong presumption" that had arisen due to common technical characteristics. According to the Malaysian Minister of Transport, it was a maintenance seal and paint that matched the documents from Malaysia Airlines. On August 19, the investigative team had completed the first phase of the investigation and should be reported on in due course. On September 3, 2015, the French public prosecutor finally confirmed that a number inside the flaperon could be linked to the serial number of the wing flap of the missing aircraft. The newspaper Le Monde also reported on a reception of family members of the four French on board MH370 by the French President François Hollande on the same day. The family members are said to have been informed that the wreckage did not show any traces of explosives. The analysis of the barnacles of the species Lepas anatifera showed that their colony must have settled on the part of the wreck in temperate or tropical waters with temperatures of at least 18 degrees Celsius. The flaperon should be driven slightly below the water surface.

As a result of this find, the coast and adjacent waters of La Réunion were intensively searched by the authorities and residents, a number of items were handed over to the police and relevant finds were examined by the international team of investigators on site, but without success. The Coast Guard of Mauritius examined the surroundings with aircraft and boats, and also in Madagascar , the Comoros , the Seychelles and the Maldives was sought. On August 17th, the search for floating debris off La Réunion was stopped after 10,000 km² of sea surface had been searched. Some of the finds reported in the Maldives also did not come from an airplane after examination.