Shield horn

Schildhorn is a headland in the Grunewald landscape protection area in the Berlin district of the same name, Grunewald, in the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district . The 110 meter wide peninsula protrudes 400 meters into the Havel and forms a small bay, the Jürgenlanke .

The Schildhorn, the Jürgenlanke and the listed ensemble Wirtshaus Schildhorn were the favorite destinations of the Berlin Sunday excursionists in the 1880s. The decline in excursion gastronomy after the Second World War led to a loss of functionality and attractiveness of the area, which the Berlin Senate was only able to partially compensate despite targeted countermeasures.

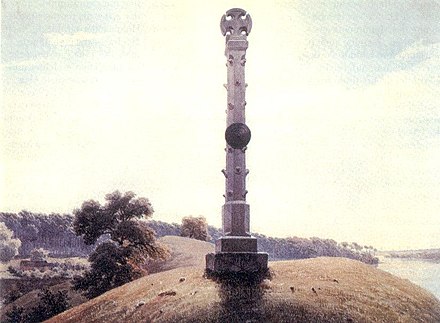

In addition to the Havel landscape and the gastronomy, the visitor attraction is the shield horn monument, which Friedrich August Stüler designed based on pencil sketches by Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia in 1845. The memorial belonged to a sculptural group of three with which the king wanted to mark turning points in the state's history in the “often dead uninteresting areas” of the Mark Brandenburg . It still exists but has largely been forgotten. The column, also known as the “Schildhornkreuz”, symbolizes the Schildhorn legend from the 19th century about the Slav prince Jaxa von Köpenick , who is said to have fled here in 1157 in the founding year of the Mark Brandenburg from Albrecht the Bear through the Havel. In gratitude for his salvation, Jaxa confessed to Christianity and hung his shield and horn on a tree. Since then, the headland has been called Schildhorn.

Geography and geology

Location and transport links

Schildhorn and Jürgenlanke are located in Berlin's Grunewald forest on the eastern bank of the Havel between the southern Kuhhorn and the northern DLRG water rescue station Postfenn. The peninsula protrudes in a northerly direction into the Havel, which here expands to a chain of lakes, and runs towards the Pichelswerder peninsula, around 800 meters away . The opposite western bank of the Havel with the Spandau districts Gatow and Wilhelmstadt (Weinmeisterhöhe locality) is around 600 meters away. Inland in an easterly direction is the Saubucht Revierförsterei and after another 400 meters on the Schildhornweg follows the so-called cemetery of the nameless , the Grunewald-Forst cemetery . After another 1.5 kilometers, the Teufelsfenn nature reserve joins with the Teufelssee . Several hiking trails, including the Schildhornweg, lead from the Grunewald to the headland.

The peninsula and the bay are connected to the road network exclusively via the Havelchaussee , which runs slightly above the slope. Two spur streets lead down from the Chaussee. One leads to the Schildhorn Yacht Club and the second, the street Am Schildhorn, past the small Schildhornbaude restaurant to a public parking lot, which is just before the peninsula at the historic Schildhorn inn. Its in-house pier only occasionally head for smaller ships on excursions.

Part of the Teltow

Geologically and culturally , Schildhorn belongs to the Teltow , which runs out to the west in the Havel lowlands. The Havel separates the Weichsel Ice Age Teltow plateau from the northwestern Nauener Platte with Gatow and parts of Wilhelmstadt. While the basement moraine plate of the Teltow is largely flat and undulating and is determined by glacial till, exceptionally thick (20 meters and more) meltwater sands from the advancing phase of the inland ice dominate the Grunewald . In the area around Schildhorn, the advancing ice has also strongly compressed (disturbed) the sands, so that here a moving relief of a compression / terminal moraine determines the landscape.

In particular, the northern edge of the 61 meter high Dachsberg - adjacent to the Schildhorn peninsula - shows a mighty compression. Schildhorn follows the western foothills of the Dachsberg, separated only by a narrow depression at the foot of the headland. Immediately after the playground there, the sands rise again and form the mountain range that defines Schildhorn, which is around ten meters above the surface of the Havel. The ridge of the peninsula is surrounded by a flat, mostly only a few meters wide, shoreline. Up until the end of the 19th century, floods occasionally flooded the small upstream depression and completely separated Schildhorn from the mainland.

Hydrology and climate

The Jürgenlanke has a water surface of around six hectares , the volume is around 120,000 m³. The shallow water depth of an average of two meters and the function of the bay as a natural receiving water of the Havel cause a high level of eutrophication . Due to the lack of flow, there is a very limited exchange of water, which can lead to stagnation of the water. Compared to other areas of the Havel, the bottom of the river is thick (two to six meters) of digested sludge . Due to its shallow depth, lack of current and solar radiation, the Jürgenlanke quickly freezes over in winter.

The Schildhorn and the Jürgenlanke lie in a moderate climate zone in the transition area from the Atlantic climate of Northern / Western Europe to the continental climate of Eastern Europe. The climate corresponds to that of the Berlin outskirts. As part of the Grunewald, the Schildhorn is one of the inner-city "cold islands".

See the Climate section in the main article: Berlin

Protected areas, flora and fauna, leisure

Landscape and water protection area

Berlin's first official conservationist, Max Hilzheimer , applied for protection ordinances in the 1920s for various areas in the city of Greater Berlin , which was founded in 1920 , including the Schildhorn nature reserve . The city did not implement the application for the Schildhorn. Since 1963, the peninsula has been part of the 3063 hectare Grunewald landscape protection area, which was created by ordinance of June 12, 1963. With the zoning plan from 1978, the city of Berlin assigned the entire Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke area the status of public green space , with the result that, with the exception of catering facilities, new buildings are no longer possible. The Schildhorn is not one of the Natura 2000 areas ( FFH and SPA ) that have been designated within the LSG Grunewald since the 1990s . The headland is located in the water protection area of the Tiefwerder waterworks . The inner circle around the Schildhorn fountain gallery is inaccessible as water protection zone I.

Flora and fauna

A dense and protected reed belt surrounds the strip of land on the headland. The embankments and the ridge are largely shaped by a mixed forest , the trees of which consist primarily of Scots pines , oaks and, after the felling in the Middle Ages and after the Second World War, pioneer trees such as sand birch , mountain ash and robinia . Wild roses and occasional late bird cherries grow in the shrubbery and bank bushes . Ruderal plants such as stinging nettle , the evening primrose species Oenothera speciosa or kahles Bruchkraut dominate the herb layer . The turf areas have high proportions of ryegrass and annual bluegrass . Standing and lying dead wood is represented in large numbers, providing a habitat for a large number of organisms and being of great importance for the protection of species of the numerous beetles . Some dead and dying trees are overgrown with hops . Immediately to the north, the Schildhorn is followed by a meadow landscape , in which there are remnants of the once extensive pale willow - black alder - alluvial forest and dense riparian willow bushes . The Jürgenlanke has isolated stocks of sea and pond roses . Due to the heavy eutrophication of the often foul-smelling bay, algal blooms occasionally occur.

Numerous ducks and reed warblers breed in the reed beds , including the endangered great reed warbler . The relatively fine, mostly sandy substrate provides an ideal habitat for the larvae of the common wedge damsel , a dragonfly from the river damsel family . Songbirds dominate the forest and the occasional great spotted woodpecker can be heard. From the class of reptiles , the slow worm and the sand lizard are represented. Small mammals are at home on the Schildhorn, while the numerous wild boars , deer and badgers in the Grunewald rarely make their way to the peninsula.

Beach and paths

At the tip of the headland, the otherwise narrow strip of shoreline widens and Schildhorn extends into an approximately 100-meter-long stretch of beach. The much-visited beach has the historic Schildhorn water rescue station, which is operated by the DLRG and whose footbridge leads far into the Havel. The station is the second oldest water rescue station in Berlin after the rescue service from 1908, which is located below the Grunewald Tower around 1.6 kilometers south . Schildhorn is a detour and “Knowledge Point 07” part of the well-signposted and information boards on the Havelhöhenweg (section 1). The hiking trail leads past the Jürgenlanke and then down into the narrow depression at the foot of Schildhorn. In front of the playground in the depression, the path divides and circles the peninsula on the narrow strip of shore in both directions. In the middle of the rear playground area, stone stairs lead to the Höhenückenweg, at the end of which is the shield horn monument.

The playground equipment on the spacious forest playground is largely made of wood. In addition to some of the usual play equipment such as swings, slides or climbing nets, there are wooden figures such as a small horse with a horse-drawn carriage. With the concept of the square and a child-friendly information board entitled “Playground Schildhorn - Prince Jaczo on the trail”, the Berlin Senate Department wants to encourage children “to immerse themselves in the world of Jaczo”. However, the board contains the widespread misinformation about naming: "Prince Jaczo hung his shield and his horn on a tree here, and thus gave the shield horn its current name".

history

etymology

The Schildhorn legend suggests that the name Schildhorn goes back to them, and some depictions and poems expressly emphasize this naming (see below). However, the derivation has not been proven. Rather, the name is etymologically based on the translation of a Slavic word as shield and on the Middle Low German geographical term horn for headland, promontory; Almost all the names of larger bank projections on the Havel lakes end in -horn, for example Kuhhorn, Breitehorn or Weinmeisterhorn. According to Gerhard Schlimpert, the defining word shield may also be derived from the shape of the headland, the ridge of which, viewed from the Havel, resembles the shape of a shield. It is more likely, however, that shield is the translation of the Slavic waterfield name Styte , whose basic Polish form Ščit is based on the original Slavic ščitž = shield . The Styte was located in the immediate vicinity of the Schildhorn and is recorded in the Spandau Hereditary Register in 1590 and 1704 as Die Styte . In Slavonic , the field name was still alive in the 1930s.

Settlement history until 1860

With some certainty there had been a Yugoslav settlement on the Schildhorn since the 12th century, which lasted into the early German period. The first written mention of the peninsula under the name “Schildhorn” can be found in the Spandau hereditary register in 1590 (“[...] where a yarn train of the Havel fishermen is called 'the Schildhorn'”). A document from 1608 in the Potsdam State Archives contains the spelling “Schilthorn” and in 1704 it says, again in the hereditary register, “Schildthorn”. As the first map, the Oesfeld map of the area around Berlin from 1786 shows the peninsula under the name Schildhorn. The statistical-topographical description of the entire Mark Brandenburg from the year 1805 by Friedrich Wilhelm August Bratring has in volume 2 the indication "Schildhorn, establishment of some Büdner, near Spandau". In 1845 Friedrich Wilhelm IV had the shield horn monument erected on the tip of the headland. In addition, until the end of the 1850s, Schildhorn and Jürgenlanke “[…] consisted only of a few thatched fishermen's houses and a wood-keeper's hut in the royal forest depository, from which the wood felled in the Grunewald was floated across the Havel." Statistics by Richard Böckh records the Schildhorn in 1861 for the first time with two houses and a directory from 1897 names an inn for the first time. All of the buildings and facilities that were built later are not located on the Schildhorn itself, but just before the peninsula on the banks of the Jürgenlanke.

Favorite destination of Berliners in the 1880s

The construction of the Havelchaussee between 1879 and 1885 connected Schildhorn, which was about thirteen kilometers as the crow flies from the Berlin city limits at the time, with the Berlin road network. After the opening of the Wannseebahn in 1874 and especially after the opening of the Grunewald train station in 1879, which was built especially for excursion traffic, Schildhorn became a favorite destination for Sunday excursions in Berlin. Tens of thousands of Sunday excursionists are said to have arrived at Grunewald train station in the 1880s and visited the forest, and in particular the Schildhorn. The construction of the first restaurant hall of the inn on the Schildhorn in 1881 took into account the large number of visitors. Since the picnic was particularly popular at that time , guests were allowed to consume the food they had brought with them in the tavern until the 1950s.

The listed ensemble Wirtshaus Schildhorn

The building of the inn are since 1985 as "local historically important and rare ensemble, [...] which reflects an interesting chapter of historicist of residential and hospitality architecture," as a monument under protection. The entire ensemble was built from 1865 in several construction stages on half a Büdnergut on Jürgenlanke.

- The first buildings in the 1860s and 1870s were three late classicist houses facing the street. The house Am Schildhorn No. 3 was built in 1870 by a signpost and equipped with four relief medallions with symbolic representations of the seasons.

- Based on designs by C. Jacob, a hall-like, single-storey restaurant hall followed in 1881 with a light half-timbered construction with whitewashed bricks in the compartment , which served as an event and conference room for up to 250 people. The building is closed by a flat gable roof , the open roof structure of which is one of the significant features of the interior.

- A second hall with glazed arcades from 1894 probably goes back to designs by A. Merker. The plastered building , in the neo-renaissance style, has large arched windows in the facade with pilasters in between and a wide, dominating cornice with a high attic . The event room for 80 to 100 people has a gallery bar. Attached is a winter garden with a terrace facing the water, which is lined with towering rubber trees. A flat gable roof also closes this hall at the top.

These structures are largely preserved on the outside.

Decline in excursion restaurants and other facilities

By 1900, three large excursion restaurants had established themselves: Schröder, Richter and Ritzhaupt. With the decline in excursion gastronomy after the Second World War , Schildhorn and Jürgenlanke lost their attractiveness. In 1965, IG Bau built the Hotel Haus Schildhorn for its non-profit recreation facility (GEW) on the southern site of the former and demolished Ritzhaupt house, the property of which ends just before the peninsula. The garden restaurant is open to the public. The northern restaurant burned down in part, so that only the middle area of the former Richter house remained as a historical restaurant. Numerous tenant changes accompanied the further history of the last inn. In the 1970s there was a Wienerwald branch here . When this branch also gave up, an urban and landscape planning report from 1980 prevented the planned demolition of the historic halls. After a temporary closure, a foreclosure auction took place under a new tenant in 2003 , after the number of visitors to Grunewald had declined again as a result of German reunification and the opening of the Berlin Wall .

In 2008, the excursion restaurant has a large summer garden for up to 1000 guests right on the Havel / Jürgenlanke, a 50-meter-long boat landing stage, a beach bar and beach chairs. While the union hotel adjoins the pub area to the south, the Schildhorn yacht harbor follows to the north with a long jetty with around 65 berths and a restaurant.

Loss of function and attractiveness

The expert opinion on an overall urban and landscape planning concept for Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke from 1980, commissioned by the Berlin Senate, established a loss of functionality and attractiveness of the area, with the result that the Schildhorn "more and more threatened to lose its face and the impression of The proposed countermeasures could only be partially implemented due to conflicts of interest between landscape protection, water protection, monument protection, excursion gastronomy, water sports (marina) as well as hiking and bathing tourism. In particular, the expansion to the new recreational focus and the focus on water sports could not be realized. The Berlin Senate took the report into account with partial measures such as the construction of new paths, the erection of information boards and the dismantling of a wild, unapproved campsite.

Communal affiliation

Schildhorn belonged to the sphere of influence of the independent city of Spandau until 1920 , which is significantly older than the Berlin founding parts Cölln and Berlin. The Yugoslav settlement on the Schildhorn was already part of the settlement chamber in the catchment area of the Slavic Spandau Castle . Even under German rule, the Teltower Heide , later the Grunewald Forest, was subject to duty and service according to the Landbuch of Karl IV. Of 1375 at Spandau Castle. The Teltower Heide was later named Spandower Heide and from 1792 Spandauer Forst , not to be confused with today's Spandauer Forst . At that time Schildhorn was part of the Spandau office . According to a map of the Teltowischen Creis , in 1788 all areas outside Berlin south of today's Heerstraße and thus also the southern Spandower Heide with Schildhorn belonged to the Teltow district . Pichelswerder , bordering to the north, remained in the Osthavelland district . Schildhorn became part of the Grunewald-Forst estate . It was not until Greater Berlin was founded in 1920 that the manor district and Schildhorn came to Berlin in the newly founded 9th district of Wilmersdorf .

Schildhorn Spandau remained connected by mail and telephone at the beginning of the 20th century. As a rule , the location information from this time is Schildhorn near Spandau and the telephone numbers were assigned to the Spandau Telephony Office . Since 2001, Schildhorn has been part of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district, which was founded by the merger of the previous districts of Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf .

The shield horn legend

The shield horn legend, often referred to as the shield horn legend, forms the background for the shield horn monument and was depicted in numerous stories, poems and paintings. The historical background of the folk tale is the last battles between Slavs and Germans, after which the Ascan Albrecht the Bear founded the Mark Brandenburg in 1157 . The legend goes back to oral tradition and existed in various embellishments and variations in terms of time, place and person. According to Wilhelm Schwartz, the legend is said to have been told in Pichelsdorf and other villages along the Havel as well as in Lietzow as a “partly contradicting folk tradition”. The oldest, still very short, transcript comes from Jacob Paul von Gundling from the year 1730. Instead of Jaxa von Köpenick , Gundling placed the Slavic prince Pribislaw , who had already died in 1157, at the center of the events. As the best-known variant, the Schildhorn or Jaxa version gradually gained acceptance since the 1830s, which is very likely based on research by the archivist and historian Adolph Friedrich Johann Riedel , who replaced Pribislaw with Jaxa in 1831. In short, the most famous version of the legend has the following content:

On his flight from Albrecht the Bear, Jaxa is said to have swum across the Havel on his horse. When he threatened to drown and the Slav god Triglaw did not answer his plea for salvation, he called on the hitherto hated Christian god in his need. With the help of the Christian God he reached the saving bank at Schildhorn, converted to Christianity out of gratitude and left his shield and horn on a tree. Hence the peninsula is called Schildhorn.

The shield horn monument

The most important artistic representation of the Jaxa saga is the shield horn monument, which the architect Friedrich August Stüler designed based on pencil sketches by Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia in 1845.

Background and designs

Three monuments for the “dead uninteresting” sandbells of the Mark

In the course of the Romantic period around 1830, in the Vormärz period, history painting from the Marks began, which was expressed, for example, in the works of the landscape painter Carl Blechen . The "patriotic novels" by Willibald Alexis are considered to be the most popular variety in Brandenburg literature. Inspired by his travels through Italy and southern Germany, the musically gifted "romantic on the throne", Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Made the decision to "revive the often dead uninteresting areas" of the march "with the erection of [...] meaningful monuments". Three turning points in the country's history were intended to breathe history into the remote "sand bells" and offer travelers incentives; For all three turning points, Friedrich Wilhelm IV made pencil sketches by hand:

- Memorial (burial chapel) for Joachim Friedrich in the Grünau Forest, in memory of the elector who died there in 1608 (not preserved, probably gave way to the expansion of the railway area at Grünau station in 1942).

- Cross on Kremmer Damm , in memory of the battles of 1332 and 1412. Renewal of the existing cross, including a base inscription in memory of the Count von Hohenlohe , who died at this point.

- Cross to Schildhorn (Schildhorn monument), for the foundation and Christianization of the Mark 1157.

Royal shield horn sketch for Stüler

The king's favorite object was the shield horn cross, the legend of which “most strongly stimulated the royal imagination in its early Christian content and led to the most idiosyncratic monument solution of the group of three”. Schildhorn probably knew Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Well. The headland lay on the Havel bank of the old Hohenzollern hunting ground . Together with his brothers, especially Prince Carl , the king had revived the hunting tradition in the Grunewald, or in what was then the Spandau Forest , and in the Grunewald hunting lodge .

In 1841 the king ordered draft drawings from Schinkel's student, Stüler, for a "monument on the Schildhorn near Spandau" to be erected. The Prussian court building officer Stüler presented his designs in 1843 and in April 1844 to the royal cabinet councilor Karl Albrecht Alexander von Uhden . The designs did not meet with the approval of the king. Stüler envisaged a griffin , the Pomeranian heraldic animal , for the top of the monument , while the king, according to Uhden, wanted "not the griffin [...] on the column, but either a simple cross or nothing at all". Friedrich Wilhelm IV sketched his ideas by hand in 1844 as shown opposite. With the cabinet order of June 26, 1844, he then officially commissioned Stüler, who had been appointed “architect of the king” two years earlier, to carry out the work. Stüler only slightly varied the specifications of the king and designed an equal-armed cross for the tip.

Building history

Erected in 1845 and inscribed in 1893

In the summer of 1845, the building inspector Christian Gottlieb Cantian completed the sandstone memorial column on the top of the Schildhorn ridge. The strict octagonal column stylizes a tree stump with indicated branches and, according to the art historian Eva Börsch-Supan, resembles a Romanesque column with knots at the Saxon collegiate church in Wechselburg . A round metal shield is attached halfway up. The crowning equal-armed cross symbolizes Jaxa's turn to Christianity. Its circular shape goes back to the Trier market cross from 958, which Archbishop Heinrich I donated as a national emblem . It also ties in with Schinkel's second design for the Ottobrunnen in Pyritz . The memorial turned out to be higher than originally planned, instead of 16 the total height was 24 feet (almost nine meters). The column originally rested on an octagonal plinth , which was drawn in on a square base. In order to hold the base in the soft Teltow floor, Cantian had it anchored on another, flatter and square base made of field stones. The budget of 420 Reichstalers provided by the king was exceeded due to the higher execution. In 1893 the following inscription in Markish-Low German dialect was attached to the massive monument base:

"Grot Wendenfürst, dorch Dine Mut

It is here that the monument is obgebut,

but hite geft kin Fersten more,

De Drever swams with shield and spear."

Former inscription memorial base

"Big turn Prince, by your courage

is built this monument here,

but today there's no more princes,

floating about with shield and spear."

Translation

The inscription was marked with FvB , was renewed in 1910 and was no longer available in 1935 at the latest.

Reconstruction in 1954 and preservation of monuments

After its destruction in 1945, apprentices from the Senate's own stonemasonry workshop in Dahlem, headed by Karl Wenk, reconstructed the monument in 1954 with the help of photographs and four pieces of rubble. The reconstruction was carried out on a pedestal that was higher than the original, which was intended to better accentuate the monument on the Schildhornkuppe, which is now covered with trees. At the beginning of the 21st century, the monument is hidden behind trees, while when it was built it was very clearly visible from all sides and also from the Havel.

With the loss of functionality and attractiveness identified in the 1980 report by the Berlin Senate for the Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke area, the monument, hidden behind tall trees and bushes, was increasingly forgotten. A garden monument preservation report from 1989 classified the neglected monument as worth preserving due to its history and its symbolic content. The proposed measures, such as a better integration into the landscape, the setting up of benches and the installation of information boards, the cleaning of the monument and the repair of cracks and demolitions, were hardly implemented by the administration. Only at the playground and at the foot of the peninsula do more recent information boards on the Havelhöhenweg indicate the monument and its history. The monument area and the monument itself, the base of which is crumbling, also appeared neglected in 2008.

The monument in painting

Numerous photographs and paintings captured the shield horn monument in the picture. The best-known representation is the painting by Eduard Gaertner from 1848, shown above as the opening picture. The picture shows the column three years after its completion, when it was still visible from all directions like a landmark on the then unwooded headland . Gaertner, whose style changed after the death of his patron Friedrich Wilhelms III. had changed from classical architectural painting to a more romantic view of nature and history, also captured the two other monuments of the group of three for the “dead uninteresting” sandbells of the Mark in the picture. The cycle was intended for the royal watercolor collection.

reception

Art criticism

The execution of the monument was heavily criticized. The actor, theater poet and publicist Louis Schneider , a member of the tunnel over the Spree and loyal to Friedrich Wilhelm IV, who died in 1861, as the official reader , criticized the shape of the cross in 1869, among other things. The architect and editor KEO Fritsch cited the shield horn monument in his commemorative speech of January 29, 1900 on the centenary of Stüler's birthday as an example of the less successful work of the master builder. Particularly among the monuments erected by Friedrich Wilhelm IV. There are significant examples of a petty and artistically immature solution: "Let us only remember the monument on the Schildhorn."

Theodor Fontane had already written in 1860:

“[The headland bears at its] foremost point […] a gray-black, whimsical image […], which reminds one half of telegraph posts, half of factory chimneys […]. It would have been sufficient to erect a shield on a tall Greek column and crown this shield with a cross of moderate size. That would have shown ... "the victory of the cross over paganism" [...] in all clarity. Archaeological zeal [...] celebrated its victory at the expense of good taste. The trunk of an old gnarled oak was reproduced in sandstone, creating a figure that was difficult to understand anyway; but the shield hung in the middle of the trunk, which sticks to a post like a disk, creates, viewed from a distance, a completely unclear and enigmatic figure. "

Gregor Geismeier, on the other hand, criticized Fontane's remarks in 1999, because the writer of the Mark missed the historical references to the Trier market cross and the Stiftskirche Wechselburg. Compared to the later monumental sculpture , which reached its climax in the Siegesallee of Kaiser Wilhelm II , the shield horn monument is characterized by idiosyncratic and creative imagination and "an original side piece to the lively discussion about the early history of the fatherland" at the time. The art critic Eva Börsch-Supan, on the other hand, misses the suppleness and the defiance of Stüler's, resolute opposition to the “witty royal dilettante”. Then many a royal monument would have remained a project.

In the time of National Socialism

While the Third Reich had appropriated the founder of the Mark and opponent Jaxas, Albrecht the Bear, at least occasionally for his ideology, there is no evidence that Schildhorn was instrumentalized by National Socialist propaganda. Although Schildhorn marked Friedrich Wilhelm IV. "Turning point in the history of the country", the Christianization of the Mark was in the foreground in the Schildhorn Cross . Pappenheim's contribution to the Spandauer Zeitung of July 13, 1935 on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of the memorial contains no nationalistic content and no patriotic glorifications, while songs of praise for the German Women's Labor Service or the youth in the new Reich fill the editorial environment of the article. In 1937, Eberhard Faden pointed out in the commemorative publication for the 700th anniversary of Berlin that Polish chronicles about the train Jaxas to Brandenburg are silent, and that the Schildhorn legend about the baptism of Jaxas, which gave Friedrich Wilhelm IV the reason to erect the Schildhornsäule, did not occur until the 19th century came up.

At that time it remained so quiet around Schildhorn that Jews were able to hide here as late as 1943. In 2007, the author Inge Deutschkron described in a lecture by the German Resistance Memorial Center how she escaped to the boathouse in Schildhorn. Friends of the author bought the boathouse in 1933 in order to "go in her rowing boat on the Havel without her political conversations being overheard."

literature

Detailed references to the legend in the main article Schildhornsage

Nature, etymology, history, architecture

- Eberhard Bohm: The last 150 years of the Hevellian Alt-Spandau . In: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slavic castle, state fortress, industrial center. Studies on the history of the city and district of Spandau. Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6 , pp. 36-55.

- Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch a. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion to obtain usage concepts for the Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke area in Berlin (West). Client: The Senator for Building and Housing, Berlin 1980

- Kurt Pomplun : Schildhorn - "Favorite destination of the Berlin Sunday excursionists". In: Kurt Pomplun: Of houses and people. Berlin stories. 2nd Edition. Verlag Bruno Hessling, Berlin 1976, pp. 55-59

- Carola Sailer: Garden monument preservation report Schildhornenkmal, Berlin-Wilmersdorf . Client: Senate Department for Urban Development and Environmental Protection, Section III - Garden Monument Preservation. Contractor: HORTEC - garden and landscape planning GbR, Berlin 1989.

- Gerhard Schlimpert : Brandenburg name book, part 3, The place names of the Teltow . Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Weimar 1972, p. 244f.

monument

- Theodor Fontane : Walks through the Mark Brandenburg . Part 1. The county of Ruppin , appendix The Schildhorn near Spandau . Numerous issues.

- Gregor Geismeier: Stüler's “meaningful monuments” in the market . In: The Mark Brandenburg . Marika Großer Verlag, Berlin 1999, issue 35 (The architect of King Friedrich August Stüler) , pp. 8-14

- Harry Nehls: What will happen to the Jaczo Tower? In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 5, 1999, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 46–54 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- Hainer Weißpflug: Schildhorn Tavern . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (Hrsg.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf . Luisenstadt educational association . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-7759-0479-4 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

- Hans Eugen Pappenheim: 90 years of the column on the Schildhorn . In: Spandauer Zeitung , July 13, 1935. 1st supplement

- Louis Schneider : The Schildhorn Monument . In: Louis Schneider (ed.): Mittheilungen des Verein für die Geschichte Potsdams 4 (IV. Part). Gropius'sche Buch- und Kunsthandlung (A. Krausnick), Potsdam 1869, pp. 275–281

- Felix Adalbert K. Kuhn : Jaczo von Köpenick . (literaturport.de) In: Märkische Sagen und Märchen , Berlin 1843; Depiction of the legend

Web links

- Schildhorn peninsula at Berlin.de

- Schildhorn - the forgotten place . Schildhorn Initiative

- Shield horn monument at City and Culture Guide Berlin

- Schildhorn and Schildhorn Monument. The Grunewald in the mirror of time

References and comments

- ↑ a b Unterhavel area - DLRG Landesverband Berlin e. V. In: berlin.dlrg.de. March 6, 2019, accessed August 31, 2019 .

- ^ Dachsberg . District lexicon on berlin.de

- ^ Ernst Friedel : The German imperial city of Berlin and its surroundings , chapter Schildhorn . In: Ernst Friedel, Oskar Schwebel: Pictures from the Mark Brandenburg . Verlag von Otto Spamer , Leipzig 1881, p. 188

- ↑ Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion ... , pp. 71, 78

- ↑ Overview of the landscape protection areas Senate Department for Urban Development

- ↑ Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning report ... , p. 49

- ↑ Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion… , p. 83f.

- ↑ Carola Sailer: Gartendenkmalpflegerisches Gutachten Schildhornenkmal, ... , p. 28 and tree population plan

- ↑ Red List and List of Breeding Birds in Berlin. Senate Department for Urban Development

- ↑ Havelhöhenweg, route section 1 (PDF) Stößenseebrücke –Schildhorn “right along the water”. Stadtentwicklung.berlin.de, Forsten, Havelhöhenweg. Complete overview of the Havelhöhenweg Havelhöhenweg . Stadtentwicklung.berlin.de, forests

- ^ The Jaczo saga , Havelhöhenweg, point 07. Stadtentwicklung.berlin.de, Forsten

- ↑ Information board on site of the Senate Department for Urban Development, Havelhöhenweg, Schildhorn playground - Prince Jaczo on the trail , status July 2008. The website of the Senate Department Havelhöhenweg, Knowledge Point 07, The Jaczo Sage, contains the same misinformation.

- ^ Eberhard Bohm: The early history of the Berlin area (6th century BC to the 12th century AD) . In: Wolfgang Ribbe (Ed.), Publication of the Historical Commission in Berlin: History of Berlin . 1. Volume, Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-31591-7 , p. 134. As a source, Bohm u. a. to: Herbert Ludat: German-Slavic Early Period and Modern Polish Historical Consciousness , Cologne, Vienna 1969, pp. 24–27

- ↑ Gerhard Schlimpert: Brandenburgisches Namenbuch, Part 3… , P. 244f. Schlimpert refers to Herrmann Patzig: Old place names in the west of Greater Berlin. Its origin and its meaning. Berlin 1926, p. 34.

- ^ Gerhard Schlimpert: Brandenburgisches Namenbuch, Part 3 ... , pp. 244, 310

- ↑ a b Eberhard Bohm: The last 150 years of the Hevellian Alt-Spandau ..., p. 53

- ↑ a b c d e Kurt Pomplun: Schildhorn - "Favorite destination of Berliners ..." .

- ↑ a b Gerhard Schlimpert: Brandenburgisches Namenbuch, Part 3 ... , p. 244

- ↑ Kurt Pomplun: Schildhorn - "Favorite destination of Berliners ...", p. 57 . According to Pomplun, the map was added to Friedrich Nicolai's description of the royal royal cities of Berlin and Potsdam from 1786.

- ↑ All information and quotations from Gerhard Schlimpert: Brandenburgisches Namenbuch, Part 3 ... , p. 244

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- ↑ Schildhorn peninsula . District lexicon on berlin.de

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- ↑ a b Hainer Weißpflug: Schildhorn tavern . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (Hrsg.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf . Luisenstadt educational association . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-7759-0479-4 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

- ↑ a b Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion…. P. 1 (preface).

- ↑ Ferienhotel Schildhorn, website

- ↑ Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion ...

- ↑ Schildhorn tavern, homepage

- ↑ Schildhorn yacht harbor; the aerial photo on the entrance side shows an overall view of Schildhorn and Jürgenlanke. Homepage

- ↑ Karl Ludwig, Falk Trillitzsch u. a .: Schildhorn / Jürgenlanke. Urban and landscape planning expert opinion ... , pp. 32ff, 46f, 59

- ↑ Felix Escher: Spandau in the shadow of the fortress . In: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slavic castle, state fortress, industrial center. Studies on the history of the city and district of Spandau. Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin 1983, pp. 160-209, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6 , p. 166

- ↑ See the picture postcard from 1902 reproduced in the development chapter .

- ^ Wilhelm Schwartz: The Schildhorn near Spandau and the last Wendenkönig. In: Mittheilungen des Verein für die Geschichte Potsdams 4 (IV. Part). Published by Louis Schneider, Gropius'sche Buch- und Kunsthandlung (A. Krausnick), Potsdam 1869, p. 282.

- ^ Entry by Ludwig Persius in his diary on November 5, 1844; reproduced from: Gregor Geismeier: Stüler's "meaningful monuments" in the Mark , in ..., p. 8.

- ↑ The term "sand bells" goes back to Friedrich II : "Forester, why are the sand bells not sown?" (Reise through Rhinluch , 1779).

- ↑ Very detailed description by Hans E. Pappenheim: Joachim-Friedrich-Gedenkstätte , slightly modified version. , originally in: The Bear of Berlin. Yearbook 1965. Festschrift for the centenary of the Society for the History of Berlin, pp. 195–224.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gregor Geismeier: Stüler's "meaningful monuments" in the market . In: …

- ^ Regina Hanemann, Jürgen Julier: On the history of the construction of the Grunewald II hunting lodge. From 1708 to the present. In: Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Berlin (Ed.): 450 Years of the Grunewald Hunting Lodge 1542–1992 , Part I. Articles, pp. 57–81, pp. 63, 66

- ↑ a b c Harry Nehls: What will happen to the Jaczo Tower? In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 5, 1999, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 46–54 ( luise-berlin.de - presentation and quotations).

- ↑ a b Eva Börsch-Supan, Dietrich Müller-Stüler: Friedrich August Stüler: 1800–1865. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-422-06161-4 , p. 975

- ↑ a b c Hans Eugen Pappenheim: 90 years pillar on the Schildhorn ...

- ↑ Schildhorn monument ( memento of July 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) bildhauerei-in-berlin.de

- ↑ Monument on the Schildhorn peninsula . District lexicon on berlin.de

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- ↑ Carola Sailer: Gartendenkmalpflegeisches Gutachten Schildhornenkmal, ... , p. 4, 36

- ↑ Schneider read a. a. on the hunting dinner after the autumn Hubertus hunts "in a witty way the protocol of the day." (Regina Hanemann, Jürgen Julier: On the building history of the hunting lodge Grunewald II. From 1708 to the present . In: Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Berlin (Ed.): 450 Years Jagdschloss Grunewald 1542–1992 , part I. Articles, p. 57–81, p. 66)

- ↑ KEO Fritsch : For the hundredth birthday of August Stülers. Commemorative speech on January 29, 1900 at the Architects' Association in Berlin. (39 pages.). Quoted from: Hans Eugen Pappenheim: 90 years of the column on the Schildhorn ...

- ^ Theodor Fontane: Walks through the Mark Brandenburg . Part 1. The county of Ruppin. , Appendix The Schildhorn near Spandau . Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, Munich 1971, Frankfurt / M. / Berlin, ISBN 3-485-00291-7 , pp. 529-533. Fontane visited the Schildhorn on April 28, 1860. First publication of the Schildhorn essay in Morgenblatt for educated readers No. 34 of August 19, 1860. (Gotthard Erler, Rudolf Mingau (Ed.): Walks through the Mark Brandenburg in 8 volumes . Structure Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-351-03104-1 (part of the Great Brandenburg Edition ), Volume 6, p. 591, comments by Gotthard Erler.)

- ^ Eva Börsch-Supan: Berlin architecture according to Schinkel, 1840-1870 . Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-7913-0050-4 , p. 697 ff.

- ^ Lutz Partenheimer : Albrecht the bear . 2nd Edition. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-16302-3 , p. 8

- ↑ Eberhard Faden: Berlin in the Middle Ages . In: Max Arendt , Eberhard Faden, Otto-Friedrich Gandert : History of the City of Berlin. Festschrift for the 700th anniversary of the Reich capital . Mittler, Berlin 1937, p. 51

- ^ Final spurt - Foundation July 20, 1944. In: stiftung-20-juli-1944.de. July 20, 1944, accessed August 31, 2019 .

Coordinates: 52 ° 29 ′ 46.18 " N , 13 ° 11 ′ 43.03" E