Wild man

The Wild Man is from the early Middle Ages until the beginning of the modern era in popular belief the Germanic and Slavic -speaking countries a anthropomorphic creatures. He was described or portrayed as a solitary prehistoric man , endowed with tremendous strength, heavily hairy, naked or clad only with moss or leaves . His way of life was on the one hand half-animal and primitive, on the other hand it was also heavenly and close to nature. Uninhabited or uninhabitable forest and mountain areas were considered his preferred place of residence.

Wild men are a specifically Central European form of a mythical or superstitious notion of half-human forest dwellers that occurs in all cultures worldwide. These beings appear first as wild people ( Silvani in Middle Latin ) or wild people, later personified as wild men and wild women or as wild women :

“ The different views of forest men and wild men, which have grown out of customs and literature, have condensed in the fine arts into the representation of a wild, hairy person, often clad in loincloths. These beings, who in the literal translation illustrate the wild, include all versions of these legendary figures. This characterization persists through all stylistic epochs. "

In the texts and illustrations, the wild man often has a metaphorical meaning. It stands for the wild, the threatening nature, for the conquered nature, for traditional cultural stages of development of humans and for certain characteristics of men that are perceived as primeval. In the Middle Ages, the wild man went from a myth of popular belief, an archetype of chaos, to a symbol for desirable character traits in the stories of the upper class of society.

Manifestations

Wild men, and less often wild women, appear

- in legends, fairy tales and in medieval literature ( epic ),

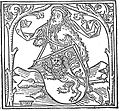

- since the middle of the 14th century in symbolic representations of medieval art on tapestries, minne boxes, choir stalls, reliquary boxes, tiles, stained glass, graphics,

- as a symbol in card games, as a common figure or more often as a shield holder in coats of arms , as coin images, as a house symbol and as a man figure in the framework,

- as a figure at parades, celebrations and rituals, represented by a disguised person,

- as namesake for parcels and mountains , for mining facilities such as pits and tunnels, for mining towns and later also for gastronomic facilities such as hotels and restaurants.

- as a metaphor for certain character traits of people or men and especially in the international literature of the 1980s as a metaphor for aspects of the gender role of men in the redefinition of the distribution of gender roles in the course of the upheaval in social conditions.

properties

- Wild men are human and not transcendent beings, that is, they are not beings from another, for example the divine world, who materialize at will in this world and can appear in different shapes and then disappear again. Since wild men are unable to do this, they can also be captured by humans. Wild men may have superhuman abilities, sometimes such as magic or vision, but are themselves biological beings who are vulnerable, can be shot at and injured. You can have a sex and family life. Only in the archaic legends of the Alpine region (mainly Tyrol ) do wild men have certain characteristics of ghost beings and natural demons.

- Wild men are human, not animal beings. They have - apart from the intense hair growth ( hypertrichosis ), their great physical strength and their nakedness , which can also occur in normal people - no animal characteristics. They have no goats' feet, no tails and no horns . In representations and in the stories, the wild man is always barefoot and - unlike animals - armed with a club or a torn tree.

- Wild men are usually inferior to humans when their great physical strength is rendered harmless. This can be done through sexual seduction, but also through female virtue, through alcohol, through magic, through combat with professional military training and armament, through long-range weapons or other particularly intelligent measures. Then you can lock them up and keep them in a cage like animals, prisoners or madmen. However, expectations of uncovering the mystery of their wildness are fundamentally disappointed.

- It was only at the beginning of the modern era that the wild men became custodians of mostly metal treasures (a role that was previously attributed to the magical and technologically superior dwarves ). That was the point in time when people had to systematically develop the last uninhabited areas in the Middle Ages in order to access the mineral resources that were waiting to be discovered in the mountains that were previously avoided as inhospitable and wild. Here they encountered the wildness of nature, from which they were able to steal their treasures through previously unknown measures. Typically, for the first time, it is also miners who meet the Wild Man, not hunters , as is usually the case .

Interpretative approaches

It is no longer possible to reconstruct whether old memories of the times when several species of hominini still existed side by side in the ideas of the wild man that are widespread worldwide . It is true that modern humans (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) lived in the immediate vicinity in Central Europe for around 10,000 years and, at least in a certain time window before the split of the Eurasian populations, produced common offspring, which is in the genetic makeup of today living Eurasian populations can be detected, but due to the large time gap between the extinction of the last Neanderthals 30,000 - 25,000 years ago and the first written figure of a wild man in the Gilgamesh epic more than 20,000 years later, no verifiable connection can be made. This applies all the more to the spread of the topos in early medieval to modern Europe.

Some references in the Old Testament speak for the explanation that the stories of the Wild Man are based on the transition period from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic Age, when humans developed from hunters and gatherers to farmers and ranchers . The old biblical stories have a certain expressiveness here, as they come from the area in which agriculture was first developed ( see Fertile Crescent ). Genesis 2: 5–33 is about the quarrel between the twin brothers Esau , the older, instinctive, hairy, the hunter, and Jacob , the younger, the self-conscious, fine-skinned, urban, intellectual, Mother Rebekah's more sophisticated favorite son . The competition between agriculture and hunting shows the superiority of the new form of society: The hapless hunter Esau has to sell his inheritance rights to his brother Jakob, who is active in agriculture and thus economically superior, in order to have anything to eat. Jacob, God's chosen one, became the progenitor of the twelve tribes of Israel. The hairy Esau came away empty-handed and became the progenitor of a mountain people.

In the old legends of the Alpine region , wild men represent, among other things, the difficult to tame and unpredictable nature, which made particularly difficult for people in inhospitable areas before industrialization . Man felt himself at the mercy of the forces and personified them in a number of legendary figures, including the Wild Men (e.g. in Wildon , Styria).

Wild men in Christianity stand outside of creation and the plan of salvation. They are figures of the lower mythology , which in the church understanding serve to symbolize the virtuous victory over them and thus over the wild, the base and the vicious. In the imagination of medieval man, wild was seen as that which stood outside human culture, community, custom and norm. In addition, it was considered the desert and the undeveloped, the confused and the ominous. For this reason, the wild men appear in the late Middle Ages not infrequently in Shrovetide , where, together with the other fools, they represent the representatives of the distance from God and thus the devil . The wild man and the wild woman can be seen as these representatives together with fool and devil, for example, on a vaulted console of the Holy Cross Minster in Rottweil .

The courtly literature of the Middle Ages contrasted the knights, who were regarded as social role models, with various frightening figures as contrasting figures, against whom the knights could then display their ethical and combative superiority. These figures included dragons and giants as well as wild men.

At the beginning of the early modern age , the aspect emerges that overcoming nature, here in the form of the wild man, opens up opportunities for wealth for people. The development of inhospitable areas through the courageous advance of the miners was linked with legends of overcoming wild men who guarded metal mineral resources . This led to the use of the wild man motif on coins and in coats of arms. They became a symbol of the wealth that had been won from nature and are proudly displayed to this day.

Similar phenomena

Forest and mountain spirits

Forest and mountain spirits in the broadest sense appear in legends and fairy tales throughout Europe and beyond. These beings are portrayed as being significantly more powerful than the Wild Man. They are considered the masters of nature and can be influenced by humans, but not destroyed. The Schrat seems to resemble the Wild Man in some ways. The Rübezahl is at home in the Giant Mountains and the Skogsfru in Scandinavia . These are ghost figures that can appear in various forms. They are able to transform and also simply to disappear. As a rule, they have magical powers or control over the forces of nature. Rübezahl is considered the lord of the mountains . It can cause storms to which the person is then helplessly exposed. There are stories in which he is ripped off by people, but Rübezahl cannot be caught or imprisoned ( see also: Naturgeist , Waldgeist , Berggeist ).

Insane or outcast

In ancient stories, for example in the Bible or in medieval poetry, there are reports of people who, due to misfortune or God's punishment, go mad and have to live wild as an animal without understanding. This can also include ripping off their clothes and walking naked into the wilderness. Outcast, confused and lost are depicted in the depictions similar to Wild Men, but in contrast to these, crawling on all fours.

Such a punishment hits the figure of Nebuchadnezzar from the account in Dan 4,1–34 . Nebuchadnezzar is an arrogant tyrant who persecutes the Jews . A heavenly voice announces the deepest humiliation to him. He goes mad and has to live like an animal and eat grass for seven years.

In a German translation of the Bible from 1480 it is said about him: And crawled uff henden and uff feet and ran almost a boum uff of the hundred elen high what and gray in sin hor and was in sin negel as bird clowns. ( Biblical histories in two volumes, St. Gallen, Vadiana Ms.343 c, fol 264 v.)

In the Welsh Merlin legend and the Latin Vita Merlini based on it , the poet Myrddin meets such a fate: When his master is killed in a battle, he loses his mind, runs into the woods and speaks to an apple tree and the pigs. He lives like this for 50 years until he is healed by a miracle spring.

A haunting description can also be found as a central plot turning point in the Middle High German Arthurian novel Iwein by Hartmann von Aue . The Arthurian knight Iwein misses a deadline set by his wife and thus loses her favor. Thereupon he flees from the farm, becomes addicted and ekes out his life in the forest as an unclothed maniac:

dô wa sîn riuwe alsô grôz

daz im in daz hirne schôz

an anger ande a tobesuht,

he broke sîne site and sîne zuht

and tender abe sîn want, because

he was blôz sam a hand.

sus he ran across gevilde

naked to the wild.

(Loosely translated: His remorse grew so great that anger and rage shot into his brain. He forgot decency and education, tore his robe from his body until he was completely bare. So he ran across the field naked into the wilderness. )

In the Middle High German verse novella Der Busant (“The Bussard”) by an unknown Alsatian author from the 14th century, the lost Prince of England vegetates wild in the forest. In this love story about the prince and princess of France, the prince goes mad after being separated from his mistress. In a carpet scene from the late 15th century he is depicted as a hairy wild figure crawling on all fours. Life without the beloved is portrayed as inhuman and wild. In the end, the couple find each other again and marry.

"Wilder Mann" was the common name in the 19th and early 20th centuries for a criminal who was taken to an asylum for mental insanity and not punished. To “play” or “mark” the Wild Man was to simulate a mental illness as the accused in order to evade punishment.

Wild children

As Wolf children or feral children is often referred children foundlings , the long isolated grew up for a time by people at a young age and therefore differ in their learned behavior from normally grown children. In rare cases, wolf children have been adopted by animals and lived with them.

There are numerous stories and legends about wolf children, but so far scientists have only been able to study a few real cases. At least 53 wild children have been found since the mid-14th century.

In the documented cases, the integration of these children into human society was not particularly successful (e.g. Victor von Aveyron , Kaspar Hauser ).

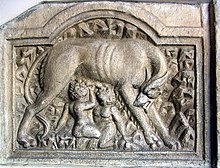

Disregarding these historical experiences, legendary heroes are often said to have had a childhood outside of human civilization, as if that were a prerequisite for superhuman achievements. In Roman mythology , Romulus and Remus are suckled by a she-wolf, a very popular motif in European and Oriental sagas, because similar stories are reported by the Slovak warriors Waligor and Wyrwidub , the founder of the ancient Persian Empire, Cyrus , and the legendary hero Dietrich von Bern in Germanic mythology . The biblical Moses was also hidden in the reeds for a time before he was found and received a special education. ( See also: The legend of the she-wolf Asena )

In modern literature there are sympathetic fictional characters who were raised by animals but who can still stand on their own in human society. The most famous include Tarzan from the books of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mowgli from the Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling .

Chimeras human / animal

As early as the Paleolithic there are paintings and sculptures that point to the idea of intermediate stages between humans and animals.

Transformations of people into wolves ( werewolf ) appear many times in antiquity, for example in the Gilgamesh epic , among the Greeks, the Romans and the Scythians .

In ancient Greece there were numerous stories about human-animal hybrids. The best known of these beings are the satyrs , the fauns and the centaurs , all of which are characterized by animal body features.

Isidore of Seville (560–646) tried in the early Middle Ages to systematize these beastmen according to their ability to evangelize. In the high Middle Ages, Albertus Magnus placed the monkeys, pygmies , dog-men and satyrs between humans and four-legged animals.

When a living great ape , a chimpanzee , came to Holland from Africa in 1641 , it was believed that the link between humans and animals had been found.

The doctor Georg Bauer ( Georgius Agricola , 1494–1556) collected bones in mines in the Ore Mountains, which were used to recognize fossils (for more details see under primates, research history ).

In 1546, at the Council of Trent , the Church explicitly emphasized that Adam was the first man and that there were no other men created by God before him. Isaac de La Peyrère (1596–1676) criticized this thesis and pointed out that Adam's children found women. He used the thesis of the pre-Adamites (pre-humans, primitive humans) as God's test creation. The hairy Esau , who Rebekah sired with a prehistoric man, was said to be Homo Sylvestris , according to Edward Tyson (1650–1708) .

Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707–1788) put the age of the earth at 75,000 years and thus contradicted the church-calculated date of the creation of the world, which was 3000 to 7000 BC. Chr. Lay. In this long period of 75,000 years, an extinction of life forms is conceivable. Carl von Linné (1707–1778) united the apes and humans in his Systema Naturae 1758 in a separate order, the primates . Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (1744–1821) founded the theory of evolution , which Charles Darwin (1809–1882) helped to achieve with his work On the origin of species .

Cryptozoology

In many cultures around the world there are reports of "hominoids" who are said to live in forest and mountain areas. These beings include, for example, the Yeti , the Yeren , the Bigfoot and the Orang Pendek . These beings are described as biologically between humans and apes. Their existence has not yet been proven, however, as the existing testimony as well as photos and films about this phenomenon are not scientifically recognized outside of cryptozoology .

Mention in texts

The basic pattern

The figure of the wild man appears in various legends and fairy tales . It is noticeable that a similar dramaturgy can be found from ancient Sumer to Grimm's fairy tales from the 19th century. People who dare to venture out of civilization into the wilderness for gainful reasons, in agricultural society they are hunters, in the early modern era miners, report observations of a wild man (sometimes accompanied by a wild woman) who is naked, hairy and with equipped with superhuman powers. His shape is otherwise completely human, but his way of life is more reminiscent of that of an animal. Normal attempts to get in touch with him or to catch him will fail. Only special measures that have not yet been tried lead to success. The wild man comes into the sphere of influence of civilized people, but does not reveal his secret. There remains a certain disappointment, the project is not going to the complete satisfaction of the executors. In the modern versions, however, by overcoming the wild man, people gain control of huge metal treasures.

The best-known stories based on this model are the ancient Sumerian Epic Gilgamesh, the Harz saga of the founding of the city of Wildemann and the Grimm fairy tale Der Eisenhans .

Gilgamesh

A wild man appears in one of the oldest literary works of mankind. In the Gilgamesh epic from ancient Sumer , the being Enkidu is created by the gods, endowed with long hair, fur all over his body and superhuman powers. He comes from the uninhabited steppe near human settlements and is spotted by a hunter grazing with the antelopes and going to water with them. After all, he lets himself be civilized by having sex with a " temple whore ".

- Enkidu ate the food until he was full. He drank the beer, seven mugs full, and he was cheerful. His heart rejoiced and his face shone. He washed his shaggy body with water and anointed himself with oil - and became a man.

Medieval epic

The figure of the wild man occurs frequently in secular literature of the Middle Ages, early examples (as Schrat ) already in Old High German glosses, since the 11th century, here at Burchard von Worms for the first time the wild woman, then increasingly in the 14th and declining since the 15th century. Heinrich von Hesler describes them as people who live in forests, waters, caves and mountains, at Chrétien de Troyes , in "Le Chevalier au Lion ou le roman d'Yvain", around 1170, the knightly titular hero changes temporarily into a savage Man, and can only be "cured" by the lady of his heart, Hartmann von Aue describes him in Iwein as a giant Moor, in the Arthurian novel Wigalois a wild woman is described. In other courtly novels, too, the wild people, with their rough, unbridled manner, form a counterworld to courtly life.

In the medieval epics of the hero Dietrich von Bern it is reported how the hero fights with various legendary figures - giants and dragons. In the story The Younger Siegenot he also meets a wild man who has caught a dwarf . The dwarf calls Dietrich for help because he fears that the wild man wants to kill him. He describes him as tiufel (New High German: " devil "). Dietrich fights the Wild Man, but his sword cannot pierce his fur-like hair, which looks like armor. Then he tries to strangle the wild man, which also fails. Finally, he can defeat him by means of a spell that is made available to him by the dwarf. It turns out the Wild Man can talk. He willingly gives Dietrich further tips to help him overcome his archenemy, the giant Siegenot.

In the Harz

The legend of the wild man also plays an important role in the naming of the Upper Harz mining town of Wildemann . The city was founded in 1529 by miners from the Ore Mountains , who were commissioned to resume mining in the Harz on a larger scale for the Guelph Dukes. According to the legend, while advancing into the inhospitable Innerste Valley, they spotted a wild man who lived with a wild woman. His traces were located exactly where the largest ore deposits were located (see mine demon ). Attempts to catch him have failed. Nor did he respond to calls. Eventually he was shot at with arrows, which injured him so much that he could be captured. In captivity he neither spoke nor was he persuaded to work; he only seemed to be interested in the deposits of the ore. When it was decided to take him to the Duke, he died of gunshot wounds. Large silver deposits were found at the place where the wild man was caught, and the town of Wildemann was founded. The town's coat of arms shows the Wilder Mann with a Sachsenross , a coat of arms that is widely used by the Guelphs .

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare referred to the character of the half-human, half-animal islander Caliban in the play The Tempest on the type of the wild man.

Giovanni Battista Basile

The Neapolitan Giovanni Battista Basile (1575–1632) put together Pentameron stories and, in some cases, ancient fairy tales in his fairy tale collection. Lo Cunto de'l'Uerco (1634–1636) comes from this collection of fairy tales and was translated by Felix Liebrecht with the title The wild man . This story is a "forerunner" of the fairy tale Tischlein deck dich (now without Wild Man) by the Brothers Grimm , published 200 years later .

Grimmelshausen

In the 18th chapter The wild man, with great luck and a lot of money, is again released from the rogue play The adventurous Simplicissimus by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen from 1668, the protagonist Simplicius, who is on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, is captured by Arab robbers in Egypt. The robbers take the long-haired, bearded and barefoot Simplicius away and clothe him "to shame with a nice kind of moss".

- [...] in this way they led me around as a wild man in the towns and cities on the Red Sea and let me see for money, pretending that they had found me in Arabia deserta, far from all human habitation, and got me prisoner .

In a larger trading town, Simplicius hears various European languages among the audience and reveals himself to the audience. Officials from Alkayr (Cairo) recognize Simplicius. Bassa ( Pascha ), who is staying in the city, condemns the robbers and releases Simplicius into freedom.

Brothers Grimm

" De wilde Mann "

In the earlier editions of Grimm's fairy tales from 1815 on, the Low German story De wilde Mann is included, in which the wild man behaves like an animal because of a curse.

- “Something emoel en wild man, de was verünsket, un genk bie de Bueren in the Goren, un in't grain, un moek everything to shame. You complain to your manor armies you can bet a little more on your lease, and you have to give the manor armies a lot: if you can catch, you should raise a terrible reward. "

- High German: “Once upon a time there was a wild man who was haunted and went to the farmers in the garden and in the corn and put everything to shame. Then they complained to their landlord that they could no longer pay their rent, and then the landlord let all the hunters come to him: whoever could catch the animal should receive a great reward. "

An old hunter eventually gets the "beast" drunk with alcohol so that it can be easily captured and takes it to the Lord.

This early, primeval version is, however, literarily revised by the brothers over time. In the last version from 1856/1857, the Low German story no longer appears. Instead, the fairy tale collection from 1850 contains the story of The Eisenhans .

" The Eisenhans "

In the fairy tale, a king sends several hunters into a forest rich in game to hunt, but none of them ever come back. None of his hunters can get to the bottom of the matter until a strange hunter comes and sees his dog being pulled into a pond by a human hand. The hunter allows the pool to be scooped out, where a wild man appears, who now obviously lets himself be tied up without resistance. In the fairy tale text it is described as follows:

- […] A wild man who was brown around the body like rusty iron and whose hair hung down over his face to his knees.

The wild man is brought to the royal palace and locked up, but is freed again by an insubordination of the eight-year-old king's son. Fearing punishment, the king's son goes into the forest with the wild man, because he promises him:

- You won't see father and mother again, but I want to keep you with me because you set me free and I feel sorry for you. If you do everything I tell you, you should be fine. I have enough treasures and gold and more than anyone in the world.

In fact, the Wild Man has a well that turns anything that falls into him into gold. In the crystal clear water of the fountain you can see a golden fish or a golden snake from time to time. The boy is given the task of protecting this well from contamination, which he fails several times. The Wild Man then sends him away, but promises to help him on his future path.

The boy enters the service of another king and, with the help of the wild man, actually accomplishes such heroic deeds that in the end he is allowed to marry the princess. At the wedding, the wild man appears in the form of another king and explains:

- I am Eisenhans and was cursed into a wild man, but you redeemed me. All the treasures I have should be yours.

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gives in his work Faust. The second part of the tragedy , published posthumously in 1832, contained a description of the wild men in verses 1240 to 1247 under the heading GIANT :

- GIANTS

- The wild men are called s'

- Well known in the Harz Mountains;

- Naturally naked in all strength,

- They are all huge.

- The spruce trunk in the right hand

- And around the body a bulging band,

- The coarse apron of twig and leaf,

- Bodyguard like the Pope does not have.

In addition to other beings from the saga, the wild man appears as the cousin of the Hellenic shepherd god Pan .

Pictorial representations

Christian iconography

In the ecclesiastical area, the Wild People naturally appear more on the fringes than in the center of the Christian world of images, i.e. more in the outer sculptures of the churches, on choir stalls or grave monuments.

Medieval book illumination and early prints

Numerous courtly epics , including chronicles, moralizing writings, travel and world descriptions, illustrate the strange, uncivilized and unbridled with wild people. In sacred manuscripts they are relegated to the border decorations and initials .

Profane building ornament

Wild men appeared frequently in the wall paintings of public buildings in the Middle Ages, but have largely been lost. In some cities there are statues of wild men as fountain figures, for example on the bronze Fontaine d'Amboise from 1515 in Clermont-Ferrand, at the lamb fountain in Nürtingen or at the "Wilder Mann fountain" in Salzburg (around 1620).

Tapestries

In the 15th century, flourished in Alsace and Switzerland, especially in the Upper Rhine imperial cities of Basel and Strasbourg an independent production of tapestries . The mostly profane tapestries were commissioned by aristocrats and wealthy citizens, who used the knitwear to embellish their late Gothic residences and thus emulated the Burgundian dukes. The main themes on the carpets were love and loyalty. As a condition of pure love between man and woman and as a condition for a godly life, the man of the late Middle Ages considered the taming of wild instincts and impetuous inclinations. According to the old knight ideal, couples were only allowed to meet in love after they had tamed their wildness. This ideal is shown on tapestries when courtly and wild people take part in hunts, conquer mythical creatures or act as a couple.

In a Basel wall hanging (see above) from 1470/1480 with the title Virtuous Lady Tames Wildmann , an elegant, calmly seated young lady is holding a bearded wild man chained to an iron anklet. The wild man tries in vain to escape, but realizes his destiny, raises his left hand, and turns his head back to the beautiful woman with the words: I want to be wild until I get a happy picture ("I will never go wild again, if a female image tames me. ”). The young woman encourages: I truw I wel you zemen wol as I billich sol ("I dare to tame you, as good and cheap as I should."). The man is tamed by the love of the virtuous lady. In the banners, both characters prove that untamed wildness can only be overcome through a mutual promise. The iron chain serves as a sign of taming, it lies loosely in the hand of the lady, since the wildness of the man should not be overcome through a show of strength, but through the love and loyalty of the woman.

heraldry

Representations of wild men (sometimes and comparatively seldom also of wild women) have also been used in coats of arms since early modern times , for example as a common figure or as a shield holder . Wild men in the coat of arms are a strong indicator of mining in the German low mountain range , in alpine regions they often stand for a local legendary figure .

In the 15th century , the first wild men appear as shield holders, where they are depicted as completely hairy, club- swinging creatures running - the coat of arms is hung on a strap around the neck. In addition to the body, the hands and feet are hairy, and in wild women also the breasts. In the 16th century, the way of representation changes: The wild man is presented as an adult, naked, male person, with significantly less body hair, but unkempt hair growth on the head and with an uncut beard. Leafy (oak) branches are often wrapped around the head and loins (leaf wreaths). In the hand the figure carries a rough club, a large branch, a standard or even a small uprooted tree, as in graves . This representation is still common today. In contrast, the coat of arms of the city of Naila shows a wild man with a golden club.

According to a decree of the Prussian State Ministry of February 28, 1881, all of the twelve Prussian provinces showed in their "Great Coat of Arms" a wild man and a knight as a shield holder. The wild man always holds a lance with a pennant in his right hand, with the little coat of arms of Prussia on it, the knight shows the historical coat of arms of the respective province in the same way. In the middle coat of arms , on the other hand, two wild men are depicted holding shields. On the large coats of arms of the principalities of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen and Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , a wild man and a wild woman were to be seen as shield holders. In Bergen op Zoom , Coevorden , 's-Hertogenbosch or Kortrijk , too, two men do this, each of whom lead clubs.

A wild man (Vildmann) can still be seen on the coats of arms of the Finnish province of Lapland and the Swedish landscape of Lapland .

In the great coat of arms, the royal coat of arms of Denmark , two wild men serve as shield holders.

1589:

Coat of arms of the Frankfurt Holzhausen1701:

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Prussia1863–1924:

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Greece , Greek version as Herakles , with lion skin1850:

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Denmark1947:

Coat of arms of the Duke of Edinburgh , with lion skin but wreathed on the head1697–1918:

Coat of arms of the Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen , left with female counterpart1871–1918:

Large coat of arms of the German Emperor

Wild men on family crests can be an allegory for many things, such as strength, unrestrainedness, ferocity, closeness to nature or loneliness. The figure can also be an indication of the family's origins, as residents of very wooded areas - with or without a local legend. Since a "talking coat of arms" is recommended for a coat of arms draft, the coat of arms can also indicate family names such as Waldmann, Waldemann, Wildmann or Wildermann. However, the measurement and interpretation of individual symbols or figures on the coat of arms is subject to the respective founder of the coat of arms, so basic statements are hardly possible. On family or personal coats of arms of Central and Northern Europe, the wild man also appears above the helmet as a crest ornament in the "upper coat of arms" (helmet, helmet cover, helmet crown, crest ornament) - mostly as a repetition of the contents of the shield or just to decorate the helmet. Right: Westermann family coat of arms, Barchmann family coat of arms, Dachröden family coat of arms . |

|

|

Coins

Through the mining of silver and ore in the Harz mining, the conversion of the ore into precious metal and finally the production of coins, the figure of the wild man as a coin image ( Wildemannstaler ) found numerous solvers (show coins with the multiple value of a taler, Julius solver), talers , penny pieces and Marien penny . The rulers of the Welfenhaus, the dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , especially the princes of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , used the motif as a symbol for the Harz Mountains.

In 1539, Duke Heinrich the Younger of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel had the first thaler minted with the motif of the Wild Man in the Riechenberg mint to honor the mine of the same name. The motif quickly became popular, and in 1557 Duke Erich the Younger followed in the Principality of Calenberg with his own coinage.

The figures were depicted as hairy, loin-cropped, wreathed giants, armed with a tree in hand. For two centuries, until the end of the 18th century, the wild man was used on Guelph coins, often the wild man was used as the sole image, rarely two wild men.

The Lichttaler of Duke Julius von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel shows the Wild Man with a tree trunk in his left hand and a burning light in his right hand. The burning light on his light coins, which is consumed, fits the motto of Duke Aliis inserviendo consumor ("In the service of others I consume myself").

The "Hausknechtstaler" of Duke August the Younger of Braunschweig-Lüneburg from 1665 with a wild man holding a tree in front of him made the citizens mock: "The wild man sweeps the forest for the Duke".

For the Lüneburg and Wolfenbüttel lines, the representation of the figure was differentiated in such a way that the wild man of the Lüneburg line (since 1692 Electorate of Hanover) holds the tree in his right hand, the wild man of the Wolfenbüttel line holds the tree in his left hand. At the end of the 18th century, in 1789 under Carl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and in 1804 in the Electorate of Hanover (copper pennies), the last mints with individual wild men on the coin side took place.

Between 1790 and 1809, two wild men were minted as shield holders on Prussian thalers. Wild women can sometimes be seen on coins from Schwarzenburg and Denmark.

Figure at parties and parades and in customs

Masquerades and dances were widespread in the courts of rulers and were known to the people. In a so-called Charivari , who in 1393 by the French King Charles VI. was held on the occasion of a wedding, the young monarch and four of his courtiers disguised themselves as wild men using pitch , feathers and tow, and chained themselves to one another. When the Duke Louis of Orléans , brother of the king, approached them with a torch, one of the courtiers caught fire and transmitted the flames to the king and the three other courtiers. The king was able to escape death in flames thanks to the presence of mind of his aunt, the Duchess of Berry, who smothered his burning clothes with her robes. The other four victims died from their injuries. The event went down in history as the Bal des Ardents ("Ball of the Burning", "Ball of the Glowing"). On pictorial representations, people disguised as wild men can always be recognized by their shoes.

The Wild Maa is one of the three heraldic figures of Basel . On the popular holiday " Vogel Gryff ", organized every January by the three honorary societies in Kleinbasels , the Wild Maa serves as the symbol of the "Society for Hearing ". Together with a griffin (“Vogel Gryff”) and a lion (“Leu”), a disguised person appears as a wild man. The three heraldic figures are accompanied by four fool figures ( Ueli ) and tambours .

The Wilde Mändle dance , which was once widespread in the Alpine region, has only survived in Oberstdorf im Allgäu and is performed every five years, the last time in 2010. 13 dancers clad with pine beards from long-established families dance to original, haunting music an impressive sequence of the Part acrobatic images. The oldest archives go back to the year 1811, when the Trier Elector and former Prince-Bishop of the Diocese of Augsburg, Clemens Wenzeslaus of Saxony , visited Oberstdorf with his sister. The residents performed a wild people dance for them and offered them a song of joy: “Be allowed to us! To play the most illustrious in front of you! You noble ones would like to feel a pleasure. ”The dancers also performed their dances in the summer residences as well as in Lindau, Constance and Switzerland. Since the dances were also performed before and later by the people, they changed in favor of the people's taste. The tradition of the Wilde Mändle dance is therefore not to be traced back to the cultic area, but to theatrical role plays of the upper class.

At the Schleicherlauf in Telfs (Austria), a carnival parade that takes place every five years , wild men appear in connection with the figure of the Panzenaff . You have the function of law enforcement officers at this event. The disguise of the performers is completely hung with treebeard , a type of lichen . In front of their face they wear an ugly mask with a long nose, warts and bushy eyebrows. The actors wear black gloves on their hands. They are armed with raw branches. The event has been taking place since the 16th century, but only took on its present form in the second half of the 19th century.

In Italy there is il selvaggio , who is a child scare in a foliage and fur costume .

Namesake in geography, mining and gastronomy

Mountains like the Wilde Männle and the Wilde Mann (2577 m, Allgäu Alps , municipality of Oberstdorf ) still bear the name of their inhabitant to this day . In Hinterstein , community Bad Hindelang , there is a "Wild Miss Stone", in the cave or niche long ago the three "Wild Maidens" Rezabell, Stuzzemuzz and Hurlahuzz should have lived. The "Wilder-Mann-Bühel" located in the South Tyrolean municipality of Eppan is a 643 m high hill above the Adige Valley. Its summit is covered by settlement remains that could be dated back to prehistoric times.

As early as 1500, Petrus Albinus reported in the Meißnische Land- und Bergchronik and the Erzgebirge chronicler Johannes Mathesius in the Sarepta of "Bleyfuhren vom Wilden Mann" and "Ore samples on the Wilden Mann" at the time of Otto the Great (936-973). Also near Goslar in the Harz Mountains, mining was already being carried out on the Rammelsberg there in Ottonian times . Monks of the Walckenried monastery discovered further ore deposits in the Upper Harz after the year 1000 . In 1347 the plague raged in the Harz Mountains, whereupon the area became deserted. At the beginning of the 16th century, Duke Heinrich the Younger of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Duke of Guelph, pushed mining in the Upper Harz in the search for iron ore and silver. The Harz mining industry was resumed by miners looking for work, mainly from the Ore Mountains .

In 1529 they founded the Wildemann settlement near Goslar . Wildemann took on the central role in regional silver mining. The Wildermann mine was built in 1532 and shortly afterwards the Wilder Mann and Wilde Frau tunnels . Wildemann became a free mining town in 1534 . It is certain that the miners from the Erzgebirge brought the idea of the Wilder Mann with them to the Harz Mountains. In the mountain town of Freiberg on the edge of the Ore Mountains there was a mine called Wilder Mann as early as 1481, and the Wilder Mann and Wilde Frau pits in Schneeberg . To this day, “Wilder Mann” is a common pit name in mining.

A legendary wild man is said to have founded the city of Marbach am Neckar with the name "Mars Bacchus".

In gastronomy, the wild man used to be a frequent eponym for restaurants and hotels that were either on the edge of mountains and inaccessible forest areas or, more simply, at the gates of a city outside the walls. Johann Andreas Eisenbarth , known as "Doktor Eisenbarth", died on November 11, 1727 at the age of 64 in the Wilder Mann Inn in Hannoversch-Münden. A well-known Viennese coffee house in the 18th district, the Café Wilder Mann, bears the name. In Jakoministraße in Graz there was a home-style inn called “Wilder Mann” that specialized in a cultivated beer culture until the 1970s. A stone statue of the “Wild Man” still stands in the building's inner courtyard.

In Dresden there is the Wilder Mann district in the Pieschen district . Originally, the name only referred to a winery or the associated old tavern, on which the legendary figure of the same name hung since 1710 as the innkeeper chosen by the landlord. With the bar, the name was first transferred to a nearby excursion restaurant and then to the surrounding residential areas on the outskirts of the Trachau and Trachenberge districts . The name of the district is very well known in the region thanks to a tram terminus of the same name and the Dresden-Wilder Mann motorway junction on the A4 .

A street crossing in the center of Kloten near Zurich is called “Zum Wilden Mann”, as are the bus stations at the four forks.

Derived meanings

The term is derived from the following contexts:

- A strut cross on a stand in Alemannic and Franconian half-timbered houses is often referred to as a " man " or "wild man".

- The wild man (der / di wilde man, de wilde) was also a vernacular Cologne author (possibly a clergyman) from the second half of the 12th century who tried to pass on an unadulterated Christian doctrine due to his simple life. The author is known only from his work. His poems Veronica , Vespasianus , Van der girheit , Christian doctrine had no further effect.

- The US-American Franciscan preacher and author of spiritual books Richard Rohr became famous in the early 1980s with the bestseller Der wilde Mann, Geistliche Reden zur Male Liberation (18th edition, Munich: Claudius, 1995, ISBN 3-532-62042-1 , Wild Man's Journey: Reflections on Male Spirituality ) on the topics of "new image of men" and "being a man and spirituality" known in Germany.

- The Chinese Nobel Prize for Literature Gao Xingjian sparked a heated domestic debate in 1985 with his play Yeren ( Chinese 野人 - “The Wild Man”, premiered in the Volkstheater Peking in Hamburg in 1988) and caused a sensation worldwide.

- In 1989 the film comedy Der Wilde Mann by Swiss writer and filmmaker Matthias Zschokke was awarded the Bern Film Prize.

See also

swell

- Aenne Barnstein: The representations of courtly dressing up games in the late Middle Ages. Triltsch, Würzburg-Aumühle 1940, (Munich, university, phil. Dissertation, 1940).

- Richard Bernheimer: Wild men in the Middle Ages. A study in Art, Sentiment, and Demonology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1952, (Octagon Books, New York NY 1979, ISBN 0-374-90616-5 ).

- Karl Haiding: Legends from the wild people. In: Austrian Folklore Atlas . 6. Delivery, part 2. 1979, sheet 115 and commentary.

- Klaus Hufeland: The motif of wildness in Middle High German poetry. In: Journal for German Philology . Vol. 95, 1976, pp. 1-19.

- Karl Löber : Wild people places on the Lahn and in the Westerwald. In: Hessian sheets for folklore. Vol. 55, 1964, ISSN 0342-1260 , pp. 141-164.

- Lise Lotte Möller : The Wild People in the graphics of the late Middle Ages. In: Philobiblon. A quarterly for book and graphic collectors. Vol. 8, No. 4, 1964, ISSN 0031-7969 , pp. 260-272.

- Christian Müller: Studies on the representation and function of “wild nature” in German Minne representations of the 15th century. Tübingen 1981, (Tübingen, University, dissertation, 1982).

- Anna Rapp Buri, Monica Stucky-Schürer: Tame and wild: Basel and Strasbourg tapestries of the 15th century. von Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1174-5 .

- Leonie von Wilckens: The Middle Ages and the "Wild People". In: Munich Yearbook of Fine Arts . Vol. 45, 1994, pp. 65-82.

- The wild people of the Middle Ages. Exhibition from September 6th to October 30th, 1963. Museum for Arts and Crafts, Hamburg 1963.

- Roy A. Wisbey: The representation of the ugly in the high and late Middle Ages. In: Wolfgang Harms , L. Peter Johnson (eds.): German literature of the late Middle Ages E. Schmidt, Berlin 1975, ISBN 3-503-01213-3 , pp. 9–34.

literature

- Norbert Borrmann: Lexicon of monsters, ghosts and demons. The creatures of the night from myth, legend, literature and film. The (slightly) different who is who. Lexikon-Imprint-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89602-233-4 .

- Peter Dinzelbacher (Ed.): Specialized dictionary of medieval studies (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 477). Kröner, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-520-47701-7 .

- Charles Fréger: Wild man. With a text by Robert McLiam Wilson . Kehrer, Heidelberg a. a. 2012, ISBN 978-3-86828-295-5 .

- Michael Görden (Ed.): The book of the wild man. The age-old myth - re-examined (= Heyne-Bücher. 19, Heyne-Sachbuch. No. 211). Heyne, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-453-05803-8 .

- Ulrich Müller, Werner Wunderlich (ed.): Demons, monsters, mythical creatures (= Middle Ages myths. Vol. 2). UVK - specialist publisher for science and studies, St. Gallen 1999, ISBN 3-908701-04-X .

- Norbert H. Ott: Wild people. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 9: Werla to Cypress. Attachment. Lexma, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-89659-909-7 , Sp. 120-121.

- Wild people. In: Leander Petzoldt : Small lexicon of demons and elemental spirits (= Beck'sche series. 427). 3. Edition. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49451-X , pp. 190-192.

- Vincent Mayr: Wilde Menschen , in: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, RDK Labor (2019), digital only: Wilde Menschen [07/10/2019], the latest, material-rich presentation on the subject's literature and art history.

Web links

- Old Lexicons

- Wildemann , German dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm

- Wild man . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 16, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 631.

- Man (wilder). In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 20, Leipzig 1739, column 744 f.

- Legends and fairy tales

- Wild man looks at his picture , Sage, Tyrol

- The wild man from Wildon , Sage, Styria

Individual evidence

- ↑ Barnstein, 1940, p. 54.

- ↑ Richard E. Green, Johannes Krause, Adrian W. Briggs, Tomislav Maricic, Udo Stenzel, Martin Kircher, Nick Patterson, Heng Li, Weiwei Zhai, Markus Hsi-Yang Fritz, Nancy F. Hansen, Eric Y. Durand, Anna- Sapfo Malaspinas, Jeffrey D. Jensen, Tomas Marques-Bonet, Can Alkan, Kay Prüfer, Matthias Meyer, Hernán A. Burbano, Jeffrey M. Good, Rigo Schultz, Ayinuer Aximu-Petri, Anne Butthof, Barbara Höber, Barbara Höffner, Madlen Siegemund, Antje Weihmann, Chad Nusbaum, Eric S. Lander, Carsten Russ, Nathaniel Novod, Jason Affourtit, Michael Egholm, Christine Verna, Pavao Rudan, Dejana Brajkovic, Željko Kucan, Ivan Gušic, Vladimir B. Doronichev, Liubov V. Golovanova, Carles Lalueza-Fox, Marco de la Rasilla, Javier Fortea, Antonio Rosas, Ralf W. Schmitz, Philip LF Johnson, Evan E. Eichler, Daniel Falush, Ewan Birney, James C. Mullikin, Montgomery Slatkin, Rasmus Nielsen, Janet Kelso, Michael Lachmann, David Reich, Svante Pääbo: A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. In: Science . Vol. 328, No. 5979, 2010, pp. 710-722, doi : 10.1126 / science.1188021 .

- ↑ vv. 3231-3238; Source: fh-augsburg.de/~harsch .

- ↑ Mayr, 2019, Chapter III.

- ^ Friedrich Sieber: Harzland-Sagen, Jena 1928, p. 65f.

- ↑ Thomas Höffgen: Goethe's Walpurgis Night Trilogy. Paganism, devilism, poetry. The interview on the book, April 2016, accessed on April 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Vincent Mayr 2019, Wild People, digital: Church art .

- ↑ Vincent Mayr 2019, Wild People, digital: text illustration .

- ↑ Vincent Mayr 2019, Wilde people, digital: book illumination and graphics .

- ↑ Vincent Mayr 2019, Wild People, digital: Profane architecture .

- ↑ In detail in Vincent Mayr 2019, Wilde people, digital: tapestries .

- ↑ On heraldic use in detail in: Vincent Mayr, 2019, Chapter IV, B, 2. Here digital: Heraldik .