Bavarians

Bajuwaren (also Baiuwaren ) is the original name form of the Baiern , the population of a tribal duchy that emerged in the middle of the 6th century and comprised most of Old Bavaria , Austria and South Tyrol . Under the rule of the Agilulfinger dukes , initiated by the Franconian royal family, the "people of the Bavarians" developed from a very mixed population. It was only at this time that the late Roman population (with very diverse older roots) and the numerous newly added elements of other origins, including those from the Hunnic and above all Germanic regions, grew together to form a Bavarian tribal people.

etymology

The origin of the name of the Bavarians is disputed. The most widespread theory is that it comes from the putative Germanic compound * Bajawarjōz (plural). This name has been passed down as Old High German Beiara, Peigira and, Latinized , Baiovarii . It is believed that this is an endonym . Behind the first link Baio is the ethnicon of the previous Celtic tribe of the Boier , which is also preserved in the Old High German landscape name Bēheima 'Böhmen' (Germanic * Bajahaimaz 'home of the Boier', late Latin then Boiohaemum ) and in the onomastic connecting points ( Baias, Bainaib , etc.) .

The second link -ware or -varii of the resident designation Bajuwaren comes from ancient Germanic * warjaz 'residents' (cf. Old Norse Rómverjar 'Römer', old English burhware 'city dwellers'), which belongs to defend ( ancient German * warjana- ) (cf. also Welsh gwerin 'crowd'). The name 'Baiern' is therefore interpreted as 'inhabitant of Bohemia'. A more general interpretation, which does not imply the origin from Bohemia, is that of “people of the land of Baja”.

According to another theory not supported by science, the name is said to come from the Latin Pagus Iuvaris . Iuvara was the Roman name for the Salzach, a river that flows in the border area of today's Bavaria and Austria and was thus the settlement area of the Bavarians. Pagus is a Latin term for region / district or governorship.

origin

In the Middle Ages the Bavarians were regarded as descendants of the ancient Boier . Older research was based on Marcomanni as those "men from Bohemia" who had become the eponymous part of Bavaria.

In the current discussion, the Bavarians are identified by some with an Elbe-Germanic group of finds, which is called Friedenhain-Prestovice after the most important sites of their cremation burial sites and the special ceramics . The settlement area of this group extended from Neuburg an der Donau to Passau . In addition to the Elbe Germanic and Romanesque settlers, whose influence can be demonstrated in the Salzburg region and in Tyrol up to the 7th century, this group is considered to be another nucleus of the later Baiovarii.

Time and again, attempts are made to trace the Bavarians back to a Romanesque origin. Mostly Germanized water and place names serve as alleged evidence of ancient Roman origin. The large number of purely German names contrasts with relatively few names of ancient Romanesque origin. The linguistic analysis based on etymology and the Germanization period shows that Romansh survived in the foothills of the Alps as islands until the beginning of the 9th century and, in isolated cases such as around the city of Salzburg, until the middle of the 11th century. The thesis of an alleged Romanesque origin of the Bavarians, on the other hand, cannot be proven with the help of either the language or the names.

Presumably the Bavarians developed as a mixture of different peoples. They settled the land between the Danube and the Alps not in one big hike, but in individual spurts. There the various immigrants grew together to form the Bavarians described by Jordanes in his Gothic story in 551 and shortly afterwards by the poet Venantius Fortunatus . Both sources unanimously report that east of the Suebi and east of the Lech lies the land of Baiuaria . The inhabitants of Baiuaria are called Baibari or Baiovarii.

In any case, in modern research there is no longer any talk of a closed immigration and land grabbing of a quasi-finished people. It is assumed that the Bavarian tribes were formed in their own country, i.e. the country between the Danube and the Alps. In the Lex Baiuvariorum , in which the old popular law of the Baier tribal duchy was summarized from 635, the noble families of Huosi , Trozza , Fagana , Hahiligga and Anniona are expressly mentioned in addition to the ducal family of the Agilolfinger . These could be the ranks of the former tribes who had secured special rights in the new duchy.

Notation

The final definition of the spelling with y for the territory of the new state of Bavaria , the kingdom of 1806, which now also included Bavarian Swabia and Franconia , goes back to the philhellenic Bavarian King Ludwig I , so it is just a "fad of the king". In the period before that the country was also called Bairn, Bayrn, Bayren and Beyern. In linguistics , a strict distinction is made between the Bavarian language and population, which are written with i , and the political territorial unit of Bavaria , which is written with y . This spelling applies today to both the former Kingdom of Bavaria and its successors to today's Free State of Bavaria and its historical predecessors such as the former Duchy and Electorate of Bavaria , even if they were spelled differently at the time.

The language

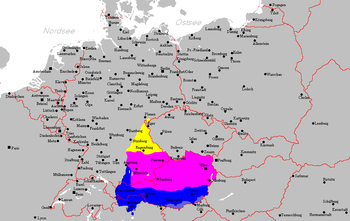

The Bavarian dialects are spoken in the east of the Upper German- speaking area and are therefore also referred to as East Upper German . Within Bavarian a distinction is made between North Bavarian, Central Bavarian and South Bavarian. The best-known feature that distinguishes High German, which includes Upper and Middle German, from other West Germanic languages, is the Old High German phonetic shift .

The Bavarian-speaking area in the Free State of Bavaria includes the administrative districts of Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria and Upper Palatinate, the territory of Austria with the exception of Vorarlberg, also South Tyrol, the Cimbrian and Carnic language islands in Upper Italy and the southern Vogtland in the Free State of Saxony. In 2009, UNESCO classified the Bavarian language as endangered and therefore worthy of protection.

In the specific Bavarian vocabulary there are also Greek influences that are conveyed through the Gothic mission:

- Ertag for 'Tuesday', from the ancient Greek weekday name Árēos hēméra 'Day of Ares ';

- Pfinztag for 'Thursday', from Gothic * paíntē dags , from the ancient Greek weekday name pémptē hēméra 'fifth day' (counted from Sunday); see. from the same tribe in Neo-Greek Pentikosti ( Πεντηκοστή ), Pentecost '.

religion

At the time of the ethnogenesis of the Bavarians, there was already a coexistence of various beliefs. From the Goths , the Arian variant of Christianity quickly spread to neighboring tribes and to the groups from which the Bavarians had emerged in the 6th century.

About after 530 the tradition of grave goods in Bavarian row graves changed. Numerous excavations have shown how the Bavarians buried their dead:

- The women were buried with their jewelry according to the Bavarian tradition.

- From the 5th century onwards, weapons were suddenly placed in the graves of men as gifts - a custom that existed among Bavarians, Alemanni and in other areas of late Roman cultural continuity. In the old settlement area of the Teutons, the Germania magna , this custom was unknown at the same time.

From 615 on, proselytizing by Irish-Scottish monks to the Catholic variant of Christianity began. The saints Eustasius , Agilus and Emmeram of Regensburg were of particular importance. Catholic bishoprics were established in the Bavarian duchy around the year 700, the oldest of which was Salzburg (696), later Regensburg (around 700), Freising (716), Passau (739) and Eichstätt (mid / 2nd half of the 8th century). The final followers of Arianism were probably only persuaded to convert after the victory of the Franks over the Lombards, which were closely associated with the Bavarians, in 774 . The overthrow of the likewise Arian Lombards by the already Catholic Franks meant the final end of Arianism in Europe. Catholic Christianity has slowly established itself among the Bavarians - through cultural exchange with the Romans since the final phase of the Western Roman Empire until the final integration of Bavaria into the Franconian Empire in 788. In addition, remnants of non-Christian traditions could possibly also be preserved under a Christian context.

Synodal activity since the foundation of the diocese in 739 has been accompanied by Bavarian regional synods under Duke Tassilo in Dingolfing around 770 AD and Neuching in 772. Bishop Arn von Salzburg invites you to a council held in 799 in Reisbach , an important Bavarian town in the early Middle Ages. This was the first time and place handed down to the Bavarian Metropolitan Synod of Bishops. Bishops, abbots, priests, archpriests and deacons from all over Bavaria were on their way to what is now Lower Bavaria on early medieval streets and paths .

history

Early history

In the year 15 BC BC the legions of Rome conquered the northern Alpine foothills as far as the Danube . The continuity of the field names and place names proves that the Celtic population must have been in the country at this point in time, as the oppidum of Manching near Ingolstadt shows, but the Germanic tribes had not yet made their home there. The archaeological evidence points in large parts of today's Bavaria to an "almost deserted wasteland" for that time (S. Rieckhof, Das Keltische Millennium. ). Only in the more inaccessible hill and mountain regions did a Celtic and pre-Celtic old European population evidently remain. Strabo names the Helvetii to the west of Lake Constance , and the Vindelikers to the east as inhabitants of mountain heaps, while Raeter and Noriker lived in the actual Alpine region (Strabo, Geographica , VII).

During the centuries-long rule of the Romans resulted from immigration and settlement a strong population growth , and by the Constitutio Antoniniana the Emperor Caracalla all free inhabitants of the from the year 212 Roman provinces the Roman citizenship was granted - even in Rhaetia and Noricum . These romanized provincial citizens are called provincials . The two relics referring to Boier in the country also date from the Roman period : a Roman military diploma , which was awarded to the soldiers of a Spanish cavalry unit (a so-called Ala ) in Raetia, whose father Comatullus was a Boio , and a ceramic shard, in which Boio was carved.

Literary references to the Celtic Boers were formulated by Strabo and Tacitus . Strabon mentions the deserted wasteland of the Bojer on Lake Constance as well as Bujaemum in the Hercynian forest (Strabon, Geographica , VII, 1), from which Tacitus then becomes Boii and Boihaemum . When Tacitus was rediscovered at the court of Charlemagne , these terms then became a model for the state of Beheim and its Slavic inhabitants as "Beheimi" = Bohemia ( see Einhard ).

Many Roman provincial residents left the Roman provinces north of the Alps in 488 on the orders of Odoacer . In eastern Raetia as well as the Danube-Noricum, this withdrawal of the Romans amounted to a partial depopulation of the country, because with the original Roman masters their servants , maidservants and slaves moved with them to their new homeland, Italy . Other parts of the ruling class from the entire Roman rulership remained in the country and mixed with the local population. Karl Bosl therefore speaks of the “Mediterranean substrate” that formed the basis for the population of what would later become Bavaria. However, it was vaulted and penetrated by Germanic tribal groups, as the German presence today shows. However, in view of the various and small references to Marcomanni, Goths or Lombards, research could not agree on a single derivation of the Bavarian warriors. So a settlement with members of different tribes is to be assumed, up to Saxony and Swabia, as can be seen in isolated place names (Sachsenkam, Schwabing).

Neighboring peoples of the Bavarians were:

- Thuringians in the north

- Franconia in the northwest

- Alemanni in the west

- Novels in the south

- Lombards in the south

- Avars in the southeast

- Slavs in the east

Today the area in which Bavarian dialects are spoken extends to

- the Bavarian administrative districts of Lower Bavaria , Upper Bavaria , Upper Palatinate , the north-eastern part of Swabia and the south-eastern parts of Middle Franconia and Upper Franconia

- the Austrian federal states Burgenland (excluding Croatian- speaking areas), Carinthia (excluding Slovenian-speaking areas), Lower Austria , Upper Austria , Salzburg , Styria , Tyrol (excluding Tannheimer Tal) and Vienna

- the autonomous Italian province of South Tyrol (excluding the Ladin area)

- the Swiss community of Samnaun in the Inn Valley.

Until the expulsions after the Second World War , this also included the neighboring part of the Sudetenland (from Egerland to South Moravia ), Hungary (near Győr / Raab and Sopron / Ödenburg) and Slovenia ( Abstaller Valley ). In addition, there were and are numerous Bavarian language islands in Italy , Eastern and Southeastern Europe , but also overseas.

Early written references

The oldest evidence for the name of the Bavarians is a passage in the Gothic history published in 551 , the " Getica " ( De origine actibusque Getarum ) by Jordanes . She names Baioras or Baibaros as the eastern neighbors of the " Swabian country" ( regio Svavorum ): " Regio illa Suavorum ab oriente Baibaros habet ... " However, this source is uncertain. Only very late copies of this work have survived. However, it is assumed that Jordanes used a multi-volume work on the history of the Goths by Cassiodorus , which, however, has not survived. Other authors who write about the same time ( Prokop , Agathias , Ennodius von Pavia ) do not mention anything about Bavaria. Gregory of Tours did not know Bavaria around 595 either. Not even Eugippius , who wrote his Vita Sancti Severini four decades before Jordanes , and who had also lived on the "Norican Danube" as a companion of this saint.

The first reliable evidence comes from Venantius Fortunatus , a poeta doctus from Italy . Around 576 he reports of his pilgrimage across the Alps to St. Martin of Tours in 565 and describes how he crossed the Baivaria am Lech ( Liccam Baivaria / Liccam Bojoaria ) coming up from the Inn in the land of the Breonen . Elsewhere he names a Bajoarius or Baiovarius who controlled the roads to the south and further over the Alps at St. Afra near Augsburg and was able to "hinder" the traveler. With his description Venantius Fortunatus provides the first concrete localization of the Bavarians.

Another written mention of the Bavarians as Baioarii can be found in Fredegar , a Frankish chronicler who named Baioarians as the alleged executor of a mass murder of 9,000 Bulgarians and their "wives and children" ordered by the Frankish King Dagobert I for the years around 631/35 .

The fourth naming of the Bavarians took place around 640 by Abbot Jonas von Bobbio , who noted in a biography of Columban of Luxeuil that the Boiae were now called Baioarii . This linguistic equation of Celtic Boiers with the Bavarians formed the literary basis of the long-standing assumption that Boier and Baiern can be identified with one another.

Ethnogenesis

The ethnogenesis (= formation of a tribe) of the Bavarians did not take place until after the population shifts caused by the great migration.

The reign of the Gothic king Theodoric the Great (493-526) in Italy is assumed to be the decisive period . Bavaria was part of the Ostrogothic Empire. In 506 Theodoric opened the northern borders of his Goto-Roman prefecture of Italia to the Alemanni, defeated by the Franks on the Rhine and Neckar . Together with Thuringians living north of the Danube, they then had to protect the “wet border” of the Italia in the north (= High Rhine- Lake Constance- Argen - Iller- Danube) against the Franks (according to Ennodius von Pavia ). The Alemanni now settled the provinces of Raetia and Noricum, up to the two Alemanni storms, initially only up to the Iller, the border of which the Alemanni later overran and moved to the Lech. As archaeological excavations show, the Alemanni also became an ethnic component of the Bavarians over time. The Lech only later became the language and cultural border that is still pronounced today. In addition to the Alemanni, other tribes are mentioned in the research, such as the Marcomanni and the Quadi (which, like the Alemanni, were also part of the Suebi / Swabian tribes - the Quads are later also known under the name Donausueben ) and the Goths. A sole Alemannic settlement is in any case excluded by the dialect border.

During their defensive struggle against Byzantium , the Goths of Italy left all the areas they ruled north of the Alps to the kings of the Franks in order to at least gain neutrality from them. This is how Raetia and Norikum became Franconian. However, there was no significant population influx. The Franks contented themselves with the military security of the area. Three years later they conquered the northern plains of Italy and the Inner Norikum ( Noricum Mediterraneum ) to the borders of the Roman province of Pannonia . An exchange of letters from that time, in which the Franconian Theudebert I praised his own abundance of power over his rival from Ostrom , Justinian (so-called “Theudebert letter” from the year 539/40), is also significant for the early history of the Bavarians. The Frankish king names Norsavorum gentes (Noric-Swabian families), who would have reconciled with his rule.

The Bavarians were gradually subjected to Christianization . In the Benedictine monastery Niederaltaich (founded in 731 or 741 AD) the so-called Lex Baiuvariorum was written down on 150 parchment pages in Latin as a body of law .

For a long time Regensburg was considered the capital of Bavaria and was the most important residence of the Agilolfingers. In the late Carolingian period (from 816) the city became the first center of the East Franconian Empire , from which the Holy Roman Empire emerged.

Around 870 Archbishop Adalwin von Salzburg referred to the Bavarians as bagoari in his letter De Conversione Bagoariorum et Carantaniorum .

Even if the exact course of the political process is in the dark, it stabilized the various Elbe Germanic and East Germanic ethnic groups, and ultimately led to that ethno-cultural commonality that is to be assessed as ethnogenesis.

Dukes of the Bavarians

The rulers of the Bavarians were provided by the ducal family of the Agilolfinger :

- Duke Garibald I (555 – approx. 591), first proven Duke of Bavaria

- Rex Tassilo I. (591–610) In 591 Tassilo I was used as rex (king) by the Frankish king Childebert over Bavaria .

- Duke Garibald II (approx. 610–630?)

- Duke Fara (approx. 630–640) a Frankish Agilolfinger, his rule in Bavaria is not secured

- Duke Theodo I (approx. 640–680)

- Duke Lantpert (680)

- Duke Theodo II (approx. 680–725?). Pope Gregory II wrote to his legate about the Baiwaria ( in Baioaria ), naming Theoto as “first” of the tribe there ( Primus de gente eadem ) and also as “Duke of the tribe of Baiern” ( dux gentis Baioariorum ). As lord of an archdiocese to be established for Bavaria, he called him dux Provincae (Liber Pontificalis, quoted from Alois Schmid). He divided Bavaria among his four sons during his lifetime.

- Duke Theudebald (approx. 711–719)

- Duke Grimoald II (approx. 702–725)

- Duke Tassilo II (approx. 716–719)

- Duke Theudebert (Theodo III) (711 – ca. 719)

- Duke Hugbert (approx. 725-736)

- Duke Odilo (736-748), an Alemannic Agilolfinger, established dioceses. Had to submit to the Frankish Carolingians

- Duke Grifo (approx. 748) In 741, in Karl Martell's last will, Grifo was assigned a part of the Franconian Empire, in Bavaria a usurper

- Duke Tassilo III. (748-788), Tassilo III. reached a position of power that no other Agilolfinger had held before him. Afterwards, he was forcibly incorporated into the Frankish empire of Charlemagne.

The Bavarian People's Law

The Lex Baiuvariorum (also Lex Baiuwariorum , Lex Bajuvariorum or Lex Baivariorum ) is the codification of the Bavarian people's law, which was created between the 6th and 8th centuries , i.e. the oldest collection of legal provisions of the early Bavarian tribal duchy . The text is in Latin and contains fragments of Bavarian style. It is the oldest and most important monument of the Bavarians.

The Lex Baiuvariorum contains 23 articles of legal provisions and procedural rules on criminal, procedural and private law, some separately for the individual classes ( clergy , nobles , free , freed , unfree ) as well as principles for the administration of church property.

The application of the Bavarian tribal law is attested to the 12th century, and it was still in the 11th century in inneralpin- Tyrolean area in practice, as the tradition of books of the Bishopric of Brixen prove.

Museums and exhibitions

- Lower Bavarian Archaeological Museum in Landau: History of the Bavarians

- Bajuwarenhof Kirchheim (The aim of the Munich archaeologists project is to make the life of the people of the 6th and 7th centuries tangible in a practice-oriented and scientifically sound manner.)

- Bavarian museum Waging am See

- Gäubodenmuseum - permanent exhibition "Found Bavaria!"

swell

- Gaius Iulius Caesar , Tacitus: Reports on Germans and Germania . Edited by Alexander Heine. Phaidon, Essen 1986, 1996. ISBN 3-88851-104-6

- Annales regni Francorum

- Eugippius: The Life of Saint Severin . Phaidon, Essen 1986. ISBN 3-88851-111-9

- Gregory of Tours : Franconian history . Phaidon, Essen 1988. ISBN 3-88851-108-9

- Isidore: History of the Goths, Vandals and Sueven . Phaidon, Essen 1990. ISBN 3-88851-099-6

- Jordanes : Gothic story . Phaidon, Essen 1986. ISBN 3-88851-076-7

- Paul Deacon : History of the Lombards . Phaidon, Essen 1992. ISBN 3-88851-096-1

- Procopius : Gothic war . Phaidon, Essen 1997. ISBN 3-88851-230-1

- Prokop: vandal war . Phaidon, Essen 1985. ISBN 3-88851-030-9

- Tacitus : Germania . VMA, Wiesbaden 1981, 1990.

literature

- Csanád Bálint: The archeology of the steppe . Böhlau, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-205-07242-1 .

- Heinrich Beck , Stefanie Hamann, Helmut Roth : Bajuwaren. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 1, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-004489-7 , pp. 601-627.

- Karl Bosl : Bavarian History . Ludwig, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-7787-2116-X .

- Wilhelm Bruckner: The language of the Lombards . Trübner, Strasbourg 1895.

- Rainer Christlein : The Alemanni . Theiss, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-8062-0890-5 .

- Falko Daim (Red.): Huns and Avars . Catalog of the Burgenland exhibition. Halbturn, Eisenstadt 1996.

- The Celtic Millennium . Catalog. Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1514-7 .

- The Roman Limes in Bavaria . Catalog. Munich 1992, ISBN 3-927806-13-7 .

- The Alemanni . Catalog. Theiss, Stuttgart / Zurich / Basel 1977, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X .

- The Bavarians . Catalog. Rosenheim and Mattsee. House of the Bavarians. History, Munich 1988.

- The chronicle of Fredegar and the Frankish kings . Phaidon, Essen 1986, ISBN 3-88851-075-9 .

- The Franks . Catalog Reiss-Museum Mannheim. von Zabern, Mainz 1996/97, ISBN 3-8053-1813-8 .

- The Romans in Bavaria . Nicol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-11-6 .

- The Romans between the Alps and the North Sea . Rosenheim catalog. Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-927806-24-2 .

- Alfred Friese: On the history of the rule of the Franconian nobility . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-913140-X .

- Brigitte Haas-Gebhard : The Baiuvaren: Archeology and history. Regensburg 2013, ISBN 3-7917-2482-7 .

- Alexander Heine (Ed.): Teutons and Germania in Greek sources . Phaidon, ISBN 3-88851-148-8 .

- Joachim Herrmann : Archeology in the GDR . Theiss, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-8062-0531-0 .

- Benno Hubensteiner : Bavarian History . 17th edition, Rosenheim 2009, ISBN 3-475-53756-7 .

- Karl Jordan : Selected essays on the history of the Middle Ages . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-912050-5 .

- Hans Peter Kuhnen: Stormed - Cleared - Forgotten . Württembergisches Landesmuseum, 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1056-X .

- Hans Losert , Andrej Pleterski: Altenerding in Upper Bavaria. Structure of the early medieval burial ground and “ethnogenesis” of the Bavarians . scrîpvaz, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-931278-07-7 .

- Bernhard Maier : The Celts . CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-46094-1 .

- Wilfried Menghin : The Lombards . Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0364-4 .

- Wilfried Menghin: Early history of Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-8062-0598-1 .

- Johannes Merz, Robert Schuh (Ed.): Franconia in the Middle Ages . Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7696-6530-9 .

- Friedrich Prinz : The history of Bavaria . Piper, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-492-23348-1 .

- Ludwig Schmidt : The West Germans . CH Beck, Munich 1938, 1970, ISBN 3-406-02212-X .

- Wilhelm Störmer : The Baiuwaren . CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-47981-2 .

- Karl Heinz Stoll: Myth of Bavaria. The literary invention of a chimera . Sequence media production, Fuchstal 2005, ISBN 3-935977-60-3 .

- Wilhelm Wattenbach , Ernst Dümmler , Franz Huf: Germany's historical sources in the Middle Ages . Phaidon, Essen 1991, ISBN 3-88851-129-1 .

- Peter Wiesinger , Albrecht Greule : Bavaria and Romanes. On the relationship between the early medieval ethnic groups from the perspective of linguistics and name research. Narr / Francke / Attempo, Tübingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-7720-8659-5 .

- Friedhelm Winkelmann , Gudrun Gomolka-Fuchs: Early Byzantine culture . Book guild Gutenberg, Frankfurt am Main 1987/1990, ISBN 3-7632-3525-6 .

Web links

- The Bavarians (re-enactment project to depict Bavarian life and culture around 580)

- Bavarian clothing, jewelry and weapons

- Early Bavarian goods in the Ingolstadt region - Friedenhain Group

- Kemathen's tomb - an early Bavarian town

Remarks

- ↑ The first real Bajuware. Retrieved August 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Brigitte Haas-Gebhard : The Baiuvaren: Archeology and History. Regensburg 2013, ISBN 3-7917-2482-7 . P. 192.

- ↑ Ludwig Rübekeil : The name 'Baiovarii' and its typological neighborhood. In: The beginnings of Bavaria. From Raetien and Noricum to the early medieval Baiovaria . St. Ottilien, University of Zurich 2012, p. 152. online .

- ↑ Ludwig Rübekeil: Diachrone Studies , p. 337 f.

- ↑ Vladimir Orel: A Handbook of Germanic Etymology . Brill, Leiden 2003, p. 449.

- ↑ Brigitte Haas-Gebhard : The Baiuvaren: Archeology and History. Regensburg 2013, ISBN 3-7917-2482-7 . P. 192

- ↑ The origin of the Bavarians. Retrieved October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Peter Wiesinger , Albrecht Greule : Baiern and Romanen. On the relationship between the early medieval ethnic groups from the perspective of linguistics and name research. Narr / Francke / Attempo, Tübingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-7720-8659-5 .

- ↑ Historical facts about the Bavarians. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015 ; accessed on October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ The Bavarians. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 14, 2015 ; accessed on October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ The Bavarian store. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; accessed on October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Early Bavarians Part 4 - The Bavarians as members of a general Elbe Germanic culture. Retrieved October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ The history of the Vilstal. Retrieved October 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Manfred Renn, Werner König: Kleiner Bayerischer Sprachatlas , Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich, 2006, ISBN 3-423-03328-2

- ^ Benno Hubensteiner: Bavarian history. Bavarian beginnings. 9th edition, 1981, ISBN 3-7991-5684-4 , p. 31.

- ^ Heinrich Kunstmann: Preliminary investigations into the Bavarian Bulgarian murder of 631/632. The facts. Echoes in the Nibelungenlied. (= Slavic contributions 159). Sagner, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-87690-241-X , p. 11.

- ↑ See Paulus Diaconus

- ^ Hubensteiner: Bayerische Geschichte , Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 17th edition 2009, pp. 44–48.

- ↑ Hannes Obermair : The right of the Tyrolean-Trientin 'Regio' between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages . In: Concilium Medii Aevi 9 (2006), pp. 141-158, reference pp. 149-150 DOI: 10.2364 / 1437905809107 .