History of church building in East Frisia

The history of church building in East Frisia ranges from the wooden Christian sacred buildings of the 10th century to the present day. In the districts of Aurich , Leer and Wittmund as well as in the independent city of Emden , around 250 churches of different architectural styles have been preserved. In addition to 125 Romanesque and Gothic churches, there are also places of worship from the Baroque and Historicism periods . The Romanesque churches can be assigned to narrower periods due to the different building materials and the different types of construction. A special feature are the Romano-Gothic churches , a transitional style that is hardly widespread beyond the borders of parts of the Netherlands and East Frisia. All style epochs dominate mounds built hall churches of brick and separately standing bell towers.

historical overview

In the area of East Frisia, with the appearance of Liudger and Willehad in the 8th century, Christian missionary activity, albeit not very successful, is documented for the first time . The first and still wooden chapel in East Friesland, presumably consecrated in 791 in Leer , is said to go back to Liudger, although it has not been archaeologically proven. As a result of the Christianization of large areas along the Dutch and German North Sea coast, which the Franks were increasingly promoting, East Friesland was finally added to the dioceses of Bremen and Münster . The prosperous monastery landscape that developed thereafter reached its heyday in the 12th and 13th centuries. The existence of a total of around 30 religious branches has been proven for East Frisia . The Premonstratensians and Johanniter were strongly represented .

The majority of medieval monastery churches were either abandoned in the pre-Reformation period as a result of storm surges or were abolished in the course of the Reformation. The rest of them fell victim to armed conflicts such as those on the part of Balthasar von Esen .

In the 12th and 13th centuries there was a lot of building activity outside of the monasteries, especially in the area of the stone churches, which resulted in more than 100 Romanesque and early Gothic sacred buildings. Famine and plague epidemics in the 14th century and at the beginning of the 15th century led to a decline in building activity and the partial decline of the previously highly developed architecture. In the 15th century there was again an architectural boom, as a result of which even small villages with a few dozen inhabitants received their own church buildings in the Gothic style or older churches were extensively rebuilt. The catastrophic floods 1509 / 1510 / 1511 and the dramatic changes which brought the Reformation with it, meant that no new churches emerged in the 16th century.

Since the Thirty Years' War and the Christmas flood of 1717 had devastating effects on East Frisia, few new buildings were built in the 17th and first half of the 18th century, especially in the north. In contrast, 20 of a total of 25 baroque churches were built in the south and east of East Frisia , as new villages were created through land reclamation and peatland colonization . From the middle of the 18th century, East Frisian church construction experienced a further heyday, when many parishes received baroque or classicist buildings. In the 19th century, new church buildings in the style of classicism or historicism (especially neo-Gothic ) replaced older predecessor buildings or supplied the newly founded villages.

Building materials and spread

The use of the building materials reflects a chronological development within the Romanesque era. The first pre-Romanesque wooden churches from the 10th and 11th centuries were replaced by Romanesque stone churches from the middle of the 12th century, preferably made of tuff stone in the west and granite in the east. With the introduction of brick construction in the 13th century, numerous late Romanesque sacred buildings were built and replaced the materials previously used. The brick has remained the characteristic building material for churches in East Frisia up to the present day.

Foundations

Already in pre-Christian times the backfill of a few meters high artificial elevations, the terps , made possible the settlement of the regularly flooded marshland of the North Sea. In a joint effort by the local rural community, the soil found was dug, piled up and lightly compacted. In the Krummhörn in particular, large collections of dwellings, the so-called terp villages , were created in this way . In the Christian era, these old foundation techniques were used to build much heavier churches.

Due to the technical possibilities at the time, the heaped ground could only be insufficiently compacted and it was therefore often unsuitable as a foundation for the entire church building. For this reason, a move was made to build the nave and bell tower at a greater distance from each other. When one section of the building was sinking, destabilization of the other could be largely avoided. However, this separation did not prevent the static impairment caused by subsidence in the floor after storm surges in the individual parts of the building itself, which in stone-built churches often resulted in cracks in the masonry and collapsing vaulted ceilings . In addition to the low level of compaction in the soil, the often missing horizontal anchors at eaves height were another factor. Under the roof load, outwardly directed forces acted on the masonry crowns, which could lead to considerable external inclinations of the outer walls.

Wood

The first wooden churches were built from the 10th century, as there were very few natural stones in the Frisian area. They were built in large numbers in the 10th and 11th centuries and were renovated using the same construction method until the 13th century. Archaeological investigations have been able to detect wood residues from the pre-Romanesque period in many places or at least made their earlier existence probable. For the East Frisian area in the Diocese of Bremen alone, the existence of 50 wooden churches could be confirmed for the 11th century, which were usually 4-8 meters wide and 17-20 meters long. The presumably thatched first wooden churches were pure post structures with corner and center posts and a threshold-based plank floor, later threshold-based half-timbered or post structures or their mixed forms. Post constructions had thresholds that were buried or placed on rows of rocks. There was a stone altar in the sometimes slightly drawn-in, but otherwise just closing choir room.

Tufa

Starting in the middle of the 12th century, the wooden churches were replaced by stone churches. While in the Romanesque period granite square churches were predominant in eastern East Friesland, which belonged to the diocese of Bremen , the first stone churches made of tuff were built in the west, which was part of the diocese of Münster . The tuff used for this, Laacher See - Pyroklastika der Nette - Trass layers, was cut to size at the mining site in the Eifel and then shipped on barges down the Rhine and along the Dutch coast to East Friesland and partly to Denmark . Areas close to the coast, such as the Krummhörn, were particularly suitable for importing the tufa from the Middle Rhine, since further overland transports were not necessary. In the 12th century, easy access for barges in the Harle Bay , which was still open at the time, explains the accumulation of tuff stone churches.

The easy workability of the porous tuff rock was offset by its poor durability in the harsh North Sea climate. As a result, tuff stone churches , such as the former Larrelter, Groothuser and Rysumer churches , were later extensively rebuilt or replaced by brick buildings. There are other churches with tuff stone in Arle , Nesse and Stedesdorf and in the adjacent Wesermarsch (for example Langwarden , Blexen and Wremen ).

Granite and field stone

In the extreme east of East Frisia and especially in neighboring Jeverland , builders used colorful granite boulders and boulders as building materials from the 12th and 13th centuries. During the Ice Age, these had been carried along as guide attachments from Scandinavia and were occasionally available in the Geest . The stones were first split with heavy tools and then built with the flat surface facing outwards. Only the front side was rectangular in shape, while the largely unworked round side between the outer and inner walls remained in a casting compound made of shell limestone mortar. This mortar consisted largely of previously slaked lime , burnt mussel schill , which was additionally provided with cut-offs from granite processing and field stones. Due to the poor adhesion of the mortar to the smooth granite of the round half of the split stones, they pushed out of the wall over time, so that they later had to be fixed with iron anchors.

The St. Marcus Church , built as a single-aisled apse hall in Marx at the end of the 12th century, made of colorful granites of different sizes, is one of the oldest and best-preserved granite square churches in East Frisia. Other churches of this type are in Asel , Marx , Middels and Buttforde (with vaults). Field stone churches were built in the district of Ammerland in Rastede , Westerstede , Wiefelstede and Bad Zwischenahn . Outside of East Frisia, there are well-preserved stone churches in Midlum and Dorum .

In addition to the mortar problems, the processing of granite turned out to be very difficult due to the extreme hardness with the tools of the time, so that in many cases only the substructure or base of the church was made from this material. To erect statically less demanding parts of the building, people then resorted to importing other, mostly cheaper building materials such as tuff or bricks. The churches in Remels (granite, tuff stone), Ardorf and Etzel (granite, brick), Arle, Resterhafe , Westerholt (foundation made of granite blocks), Blersum , Horsten and Leerhafe (foundation and base made of granite blocks) are examples of this mixed construction method .

Sandstone

In the area of the lower Weser, from the 12th and 13th centuries, church buildings made of Weser sandstone can be found up to the western Jade bank . The sandstone was easy to work with and was a popular building material for the window lintels in granite ashlar churches . Preserved Weser sandstone churches can be found in the Wesermarsch ( Abbehausen , Berne , Dedesdorf , Rodenkirchen ). In East Friesland, the Burhafer Church was originally a sandstone building.

Brick

The brick sat down as a new building material only from the 13th century through than one of religious orders the art learned to burn weatherproof made of mud bricks. In this way, with the help of wandering brick masters, the blanks, which were cut into wooden molds, could be burned into red bricks in large piles . The majority of the historic churches in East Friesland are brick churches, which penetrated into the fertile marshland in the 13th century, where the clay-containing building material was abundantly available and where one was protected from flooding since the dyke was built. Near the coast, agriculture and livestock were added to maritime trade, so that the churches here were particularly representative and lavishly designed.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the earliest brick churches with eastern character were built in Hage and Victorbur . In the area of the Ems , the first Romanesque churches made of brick can be found in the first half of the 13th century in Bunde (nave), Bingum , Ditzum , Emden (large church) , Leer (St.-Liudger) , Midlum and Weener (later several Extension conversions), further brick buildings from this period in Aurich-Oldendorf , Bagband , Canum , Dunum , Freepsum , Holtrop , Horsten, Strackholt , Suurhusen , Tergast , Uttum , Westerholt and Wiegboldsbur . The first characteristics of the early Gothic can be seen in the churches in Eilsum , Marienhafe and Pilsum . Romano-Gothic brick churches from the second half of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century can be found in Bangstede , Bunde (transept and choir of the Kreuzkirche), Campen , Engerhafe , Grimersum , Hatzum , Ochtelbur , Osteel , Roggenstede , Stapelmoor and Westeraccum .

Of the relatively few late Gothic churches in East Friesland from the 15th century, those in Hinte , Rysum , Weener (choir) and the Norder Ludgerikirche (high choir) are the most important. The brick has remained the characteristic building material of East Frisian churches up to the present day.

Building epochs and designs

Romanesque

The first wooden churches, which emerged from the 10th century, were simple hall churches, geosted, with a rectangular floor plan and a straight, sometimes retracted choir end. The Romanesque successor buildings made of stone were built on the same floor plan, but usually extended and closed with a semicircular apse. While the hard granite walls did not allow any decorative elements, the tuff stones from the Eifel also imported the Middle Rhine architectural style. It is possible that stonemasons from the Middle Rhine also accompanied the transport and built the church on site. As a result, the first stone churches with their very different floor plans , but usually with a tower, entrance portals and three small arched windows on the long sides as well as the eastern, semicircular apse , were of high quality. The windows were characterized by funnel-shaped reveals. The characteristic small high-seated windows on the long sides were often extended to larger ogival arched windows in the Gothic or to large round arched windows in the Baroque. Most likely the Romanesque windows on the north side have been preserved.

The first brick churches around 1200 were mostly designed as simple, flat-roofed one-room churches or as apse halls (examples are the Rheiderland churches in Bingum, Ditzum and Midlum). Initially, the new building material was a cheap substitute for the imported natural stones granite and tuff. Just a few decades later, architecture in the wall structure is characterized by rich decorative elements such as pilasters or pilasters , plinths, eaves cornices and arched friezes , as in the nave in Bunde and particularly rich in Victorbur and Hage. During the Gothic period, the apses were often replaced by a polygonal choir closure or torn down due to dilapidation.

These new design elements, which were also used in other Romanesque churches in the last quarter of the 12th century, were used on the nave of the Ansgarikirche in Hage , which was built around 1180 to 1190. A little above half the height of the wall there are pilasters that divide the wall into five fields, each with a small arched window that is enclosed by a narrow round bar. The pilasters suddenly merge into a cross-arched frieze , above which a triple German band forms the wall closure. The mighty west tower was added 50 years later. The Romanesque forms emerge in the pilaster strips, the arched friezes and the arched openings.

In a second phase, hall churches with vaults were built from the middle of the 13th century, under the influence of Westphalia mostly three yoke domical vaults , especially in the Romano-Gothic churches. Only a few of these vaults have survived, such as in Eilsum, Campen (richly decorated), Canum, Pilsum, Stapelmoor and Westeraccum ( ribbed vaults ). Only the choir vaults have been preserved in Visquard and Engerhafe. The oldest vault shows the crypt of the otherwise demolished Liudgerikirche in Leer. In many other churches the vaults collapsed over the centuries or were torn down and replaced by wooden barrel vaults (Bunde, Dornum ) or wooden flat ceilings (Roggenstede, Westochtersum ). The shield arches still bear witness to the original construction.

Romano Gothic

The Romano-Gothic is a transitional style from the 13th and 14th centuries, which only developed as an independent architectural style in the province of Groningen and in western East Frisia. Occasionally it is also referred to as "early Gothic". This architectural style developed clearly from the Romanesque, but has specific characteristics that set it apart from purely Romanesque churches. The Romano-Gothic church building in East Friesland are built exclusively of brick and have a wall outline with horizontally spaced-apart planes on which blend African serve as decoration. The gable triangles of the transept are also equipped with niches. The initially small arches are recessed in the wall and have round profiles. Sometimes wall reinforcements and buttresses are used, which point to the Gothic. The east side, in particular, can be designed decoratively with glare fields, diamond patterns in the gables, oculi , groups of three windows , consoles and arches . Various decorative elements anticipate the Gothic, but not its construction principles. Inside, eight-part cross-rib vaults are used, which are flattened at the top so that the ribs form a circle in the center. A development has taken place within the Romano-Gothic, with the oldest examples showing a greater use of niches and gable decoration than the younger ones. Gradually, these were used less, the windows were larger and formerly round arches were replaced by pointed arches, until finally purely Gothic elements were used. Seven single-aisle churches were given the shape of a cruciform church through a transept. The cruciform church in Marienhafe was formerly three-aisled and two other cruciform churches have been demolished: the Andreaskirche in the north and the old Magnuskirche in Esens .

An early example of a Romano-Gothic hall church is the Dreifaltigkeitskirche in Collinghorst (around 1250). The east gable of the Grimersum church is structured by staggered panels, the group of three windows below is flanked by two panel niches. The pilaster strips running down to the ground are almost completely covered at the yoke boundaries and corners by modern buttresses. The Vellager church , a hall church from the 13th century, is of small arched windows and dentil frieze coined. The Groß Midlumer Church (around 1270 to 1280) is a rectangular hall church with a semicircular east apse, which still has the original high-seated small arched windows on the north side.

St. Mauritius in Reepsholt was completed in three construction phases in the 13th century. The hall church was given a cruciform shape through a narrow transept. In the lower area, which consists of granite blocks up to a height of four meters, there are still the round-arched portals, while the upper brick zone and the choir from the third construction phase (around 1300) have pointed-arched windows. The transept gables are decorated with round panels with a herringbone bandage and a three-pass frieze, which you would otherwise not encounter in East Friesland, but in the Dutch Friesland. The 7 / 10 polygonal choir plan goes back to Westphalia influences.

The only choir tower church in northern Germany is the Eilsumer Church . In a first construction phase, the tower above the square choir with late Romanesque semicircular blind arches and arched friezes was completed around 1240. Similar to Pilsum, the long sides of the ship, which was built around 1240 to 1260, are divided by two levels with round-arched blending arcades, larger, flat arches at the bottom and small, deeper arches at the top with narrow round-arched windows that were later extended downwards. Inside, the domical vaults with their pointed girdle and shield arches and narrow cross ribs already have Gothic features. Sandstone blocks can be found in the masonry. In addition to the Gothic Association, there is also a Märkischer Verband .

The eastern part of the Reformed Church in Bunde, with its more elaborate design than the nave (around 1200), is clearly Romano-Gothic and dates from around 1270 to 1280. The walls of the choir are divided into two levels on the outside: The lower area has continuous Arched arcades. They are built as blind arches with capitals on round bars with oculi in the middle . In the upper part of the east wall there is a triple pointed arch window, which is flanked by two blind windows with cloverleaf arches with a checkerboard and herringbone pattern . Blind windows with round arches are incorporated into the side walls. The original diamond pattern has been preserved on the northern gable .

The Stapelmoor church in the shape of a Greek cross without right angles dates from around 1300 and is considered one of the most important sacred buildings in East Frisia. Compared to the architecturally similar cruciform church in Bunde, the church in Stapelmoor was spared any major alterations. The outer complex has pointed arched windows and portals, console friezes under the eaves, stair friezes on the transverse gables and the usual triplet window on the east side. Inside, the east and west yokes are closed with an eight-rib domical vault and the three transept yokes with rib-less domed vaults.

The Hatzum St. Sebastian Church (end of the 13th century) with two blind windows on the south wall was originally a cruciform church. Crossing pillars , shield arches and wall reinforcements point to the original eight-rib vault . At the bottom of the choir walls remains of the arched arcature are still visible.

Unique for East Friesland is the crossing tower of the Pilsum Kreuzkirche from the transition period, which was built around 1300 as part of a third construction phase and with its panel structure already indicates the emerging Gothic. The oldest structure from around 1240 is the nave, which is characterized by a two-storey panel structure with the upper, smaller arches rising slightly towards the center. In the last quarter of the 13th century the transept and choir were added. The transept is divided into three almost square yokes and has a diamond pattern made of brick bars on the gables for decoration, and on the east side a round arch frieze between corner pilasters. The choir consists of a square yoke and a semicircular apse, the wall of which is divided by three windows and inside and outside with arched panels. Builders from Marienfeld Abbey designed the vaults over the crossing, choir and transept.

The Marien-Kirche in Marienhafe is a particularly impressive example of its own . Drawing on the structural forms of the Osnabrück Cathedral and French models, it was built from 1250 to 1270 as a monumental three-aisled basilica . The torso of the former system with transept and six-storey tower was preserved as the shortened and lowered main nave and the four-storey tower. A rich sculptural building sculpture with mythical creatures and monsters in 48 niches, choir and transept and 200 sandstone reliefs adorned the eaves around the church, the remains of which are kept in the tower museum. The long sides are divided into three fields by pilaster strips and blind arches, each of which has two pointed arched windows, while the east wall is decorated with blind windows. The interior is characterized by heavily profiled wall pillars and a double-shell top arcade with a walkway. Until it was partially demolished in 1829, the former Sendkirche was the largest and most important sacred building in East Frisia and far beyond that in the entire coastal area of the North Sea.

The Warnfried Church in Osteel also dates from the 13th century, was architecturally based on the Marienhafer Church and also shared its fate: of the original cruciform church with transept and choir, only the shortened nave remained after a partial demolition in 1830; half of the six-storey tower was demolished. As in Marienhafe, there was originally a walkway in the two-shell walls, while statues were placed outside in 47 niches.

The final examples of this construction period include the Werdum St. Nicolai Church with its corner pilasters and the richly decorated cornice from 1327. The choir of the Rhauder Church , which is difficult to date, also points to the with its arched windows, the polygonal floor plan and the buttresses Transition style.

Gothic

Compared to the Romanesque with the small arched windows and the uniform wall structure, the larger pointed arched windows and the new plastic design of the walls are characteristic of the Gothic . A new vault construction with steeper rib vaults and the help of supporting pillars on the zygomatic arches made it possible to use less stone material. After the Gothic period, no stone vaults were built in East Frisia until the late 19th century. The polygonal choirs, which often took the place of the semicircular Romanesque apses, are characteristic of the Gothic building epoch. Only in Hage and Holtgaste there are late Gothic choir additions with a rectangular floor plan.

Compared to the elaborate Romano-Gothic architectural style, a simpler type of building in the early Gothic was widespread in rural areas, such as in Campen, Freepsum, Loquard , Uphusen , Upleward and Visquard . The floor plans were again made simpler and dispensed with an apse. In western East Frisia, nine Romanesque village churches were replaced by Gothic successor buildings in the 15th and early 16th centuries; others received only a Gothic choir.

In the Greetsieler and Manslagter churches (both around 1400), a decline in the previous high level of architecture can be seen in the low building height, the poor quality of the walls and the sparse decorative elements, which are distributed quite arbitrarily over the simple facades. Buttresses and vaults were dispensed with in both churches. The panels are set off by simple recesses, while the pointed arch windows only have sloping reveals without profiles.

Visible from afar, the high choir of the Norder Ludgeri Church characterizes the largest sacred building in East Friesland, which is designed as a three-nave cathedral structure. After the Romanesque transept collapsed around 1445, a new one in Gothic style was performed. At the same time the choir was built, which towers over the rest of the building with a top height of 21 meters. A vaulted ambulatory surrounds the aspiring central nave, which is divided into three zones with profiled pointed arches: below arches between the high choir and the gallery , in the middle blind niches and as a conclusion the top window with sloping reveals. The ribbed vault rests on 13 round pillars, above whose capitals the pear-shaped vaulted ribs start, which finally end in keystones.

The late Gothic polygonal choir extension of the Georgskirche in Weener replaced the original apse since 1462. Light falls into the room through three large, ogival windows. The consoles in the choir still bear witness to the original vault. From the chancel you can still see the large triumphal arch , which is pointed arched. The model for many churches in this area was the Martinikerk in Groningen , where a monumental high choir was built between 1445 and 1481.

The rear church from around 1500 is considered to be the most important late Gothic church building in East Frisia, along with the Norder Ludgeri Church. Stylistic similarities exist with the north Dutch monastery of Ter Apel and the East Frisian group of Larrelter , Petkumer and Twixlumer churches . It is possible that the rear church was built on the model of the Benedictine monastery church of Sielmönken , which was consecrated in 1505. The well-preserved brick church with a polygonal choir is characterized on the outside by strong pillars, windows with sandstone tracery made of fish bubbles and pointed arches as well as a surrounding coffin cornice . The windows of the north wall are partly bricked up, partly originally designed as blinds. The simply designed interior is structured by four yokes with belt arches. In the choir there is a three-pointed star vault , the shield and belt arches of which extend to the floor, while in the nave the net vaults with intermediate ribs rest on chalice consoles .

The introduction of the Reformation in East Frisia ended the Gothic construction phase.

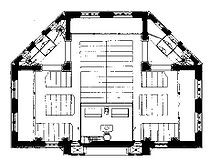

Baroque

East Frisia was affected by the consequences of the Spanish-Dutch War (1568–1648). As a result, there was hardly any building activity during the Renaissance. One of the few examples from the time of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) is the New Church in Emden (1643–1648), which, like the Emden Town Hall (1574–1576) , was destroyed in the Second World War. The red brick church from the early Baroque was built as a Protestant central building based on the model of the Amsterdam Noorderkerk , but still shows some signs of the Renaissance . It is considered to be the most important Protestant church building in East Frisia. Opposite the Norderkerk, which has four arms of equal length on the plan of a Greek cross , the south wing was dispensed with in Emden, so that a T-shaped preaching church with a centralistic tendency was created. The gable ends are provided with two large arched windows in the lower area. Above this, at the transition to the gable triangle, a round window is attached, which is closed off by a decorative tympanum . Light bands of ashlar loosen up the outer walls. The two triangular gussets between the arms of the cross are filled with annex buildings , which reinforce the impression of a central building through their diagonal outer wall.

As a rule, the baroque new buildings are small hall churches with arched windows and walls structured by pilasters, which were built in this form until the Classicism period. Compared to the southern German baroque, the northern German expression is much simpler, but still has typical baroque characteristics. An example of such a baroque village church is the St. Maria Church in Marienchor from 1668. The rectangular hall church has four arched windows with pilasters on the long sides and two eastern arched windows. Instead of the east apse there is a small west tower with a pyramid roof, which is decorated with an eaves cornice and pilaster strips. In between, small paired round arches serve as acoustic arcades.

As with the Great Church (1785–1787) and the Luther Church in Leer, the Protestant character of East Frisia is reflected in cross-shaped central buildings. The Great Church in Leer is based on the models of the New Church in Emden and the Amsterdam Noorderkerk. The octagonal floor plan has the shape of a Greek double cross, the cross arms of which are filled by annex buildings. Open round arches allow access to the inside of the church and to the surrounding galleries. Large arched windows supply the annex rooms with light. Round-arched double windows are installed in the gable ends under a round window. The bell tower consists of a square basement on which two tapering octagonal floors rest, which lead into an open lantern . The wind vane in the shape of a three-masted sailing ship, the "Schepken Christi", is the symbol of the Reformed Church.

The Luther Church in Leer from 1675 only took on the shape of a cruciform church through various extensions over the course of more than two centuries. Since the side arms are connected to the nave by three large round arches on free pillars, the church is dominated by the nave, while the wings appear separated. The shape of the bell tower on the west side clearly resembles the tower of the Great Church: an octagon is erected over a square base, above which the octagonal open lantern rises, which is closed by an onion-shaped helmet. It is crowned by a swan, whose small world crown on the swan neck gratefully reminds of Frederick the Great , who approved the western extension in 1766.

The Mennonite Church in the North (1662) was originally a patrician house, which was converted into a church building in 1795. The baroque Carolinensieler Church (1776) is the only church that was built on a dike. Several baroque churches replaced older predecessor buildings, such as the Woltzetener (1727), the Bedekaspeler (1728), Heseler (1742), Cirkwehrumer (1751), Nortmoorer (1751), Westerburer (1753) and the Amdorfer Kirche (1769), as the Romanesque or Gothic buildings were obviously lost or had suffered damage from acts of war or flooding. The interior of many East Frisian churches is now baroque.

classicism

Compared to the baroque display of splendor, classicism reveals itself to classical antiquity, which is reflected architecturally in clear forms with geometric structures and a bright room design. The main features are representative entrance portals with triangular gables, supporting columns and lunette windows . In East Frisia, however, the transition from baroque to classicism is fluid and in individual cases can hardly be seen.

The Reformed Church (1812-1814) and the Lambertikirche (1833-1835) in Aurich were both built according to plans by Conrad Bernhard Meyer . The Reformed Church is the only classicist central building in the Ems-Weser area and, with its four Tuscan columns under the triangular gable above the entrance portal, is based on the Roman Pantheon . A round skylight in the large semi-dome, which rests on eight Corinthian columns, provides the circular interior with ample light. However, the Lamberti Church as saloon and preaching church designed not their rectangular plan faces east , but is oriented transversely to the north. Segmented arched windows and lunettes illuminate the room, which is equipped on three sides with a circumferential gallery supported by columns with Doric capitals.

Smaller classicist village churches in particular are characterized by a great continuity with baroque architecture. The long sides of the church in Grotegaste (1819) are divided by pilasters into four wall fields, each with a large arched window, as was also the case in the Baroque. The Forlitz-Blaukirchen church (1848) has three round arched windows without pilasters on each of the simple long sides. The west tower is more richly designed with a pointed helmet and large, arched glare fields on three sides of the tower. They are broken through by two acoustic arcades under a small round screen. A bezel is attached above the west portal.

The towerless Mennonite Church in Leer from 1825 is, apart from the representative portal with triangular gable, kept simple inside and outside in accordance with Mennonite piety. The flat hipped roof is closed off by a strong eaves. The cube-shaped building has three lunette windows on the long sides and two on the west side.

historicism

Unlike the epoch of classicism, historicism is not very uniform. Individual classical elements continue to have an effect in various transitional forms. Various older style epochs are imitated, in East Friesland in particular the Gothic and Romanesque.

The three-aisled St. Magnus Church in Esens (1854) reflects romantic historicism and combines various stylistic features into a unique, closed whole that has remained without parallel. The juxtaposition of the cube-shaped main nave, east transept and west tower as well as the semicircular east apse is reminiscent of classicism, which is underlined by decorative ornaments and the horizontal bands. On the other hand, the interior, with its slender bundle pillars and the wooden and narrow-ribbed cross vault, is reminiscent of a Gothic hall church. The hall church of St. Joseph in Weener (1842/43) with its round arch style is also committed to the romantic historicism of the Schinkel School .

Numerous neo-Gothic church buildings were built in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century as a replacement for previous buildings that were missing or in the newly developed moor areas, for example in Ostgroßefehn (1894/95) and Ostrhauderfehn (1896). Neo-Gothic houses of worship were also built on the islands, such as the Evangelical Island Church (1879) and St. Ludgerus (1893) on Norderney .

The Loppersumer Church is the first neo-Gothic church in East Friesland to have the characteristic main features of this new architectural style: pointed arch windows, stepped buttresses and richly designed cornices as well as a polygonal choir closure. Since the Gothic bell tower was retained, the otherwise typical west tower is missing. The buttresses from this period have a largely decorative function and do not have to absorb any vaulting forces, as the interiors are closed off with wooden hollow or barrel vaults or the roof structure (as in the Holthuser Church ) remains open.

The Church of the Good Shepherd in Münkeboe from 1900 is unusual for East Frisia. It has two side aisles, each closed with three small hipped roofs, a west tower and a polygonal choir. The three-window group, the coffin cornice , the pointed arches and buttresses as well as the tracery are characteristic of the neo-Gothic . The Christ Church in Hollen from 1896 has a transept with two gables.

Compared to the numerous neo-Gothic churches, there are only a few in the neo-Romanesque style . The St. Ludgerus Church in Aurich (1849) has profiled neo-Romanesque windows and a straight choir closure. In the gable above the entrance portal, there are two narrow, paired, arched windows with a round screen in a niche. The gable front is decorated with corner pilasters, an arched frieze and some battlements . The right third of the gable has given way to a tower, which was built into the enlarged building in 1903 and takes up the decorative forms of the gable. The simple neo-Romanesque church in Moordorf from 1893 is designed in a very similar way, which received its west tower in 1908, which was added in the middle. With its simple shapes, the two short transept arms and the round apse as well as the arched windows and the frieze on the long sides and on the tower, the Church of the Holy Guardian Angels on Juist ties in with the architecture of the 13th century. The building is characterized by a semi- rotunda that was added in 1961 and is wider than the nave. It has a continuous ribbon of windows under the eaves and fields delimited by concrete pillars, each with a small round window.

The end of historicism are the Art Nouveau churches on Borkum ( Reformed Church , 1896/97) and Borssum (1912/13), both of which were built according to plans by the architect Otto March . The church in Borkum has the same floor plan as the mountain church in Osnabrück. In Borssum, the nave is adjoined by a transverse western building, from the middle of which the massive western tower rises and dominates the building. The long sides have niches with segmental arches , in which groups of three windows are attached on two levels. The two entrances on the side of the tower are located in high niches that are closed off by a group of three windows with a three-pass arch. The center of the niche is decorated with a curved band, which can also be found in three zones in the gables of the transverse building. Between the entrance niches there are four small arched windows in the lower area of the tower. The same flowing forms of Art Nouveau dominate the church tower, which has four narrow panels with segmental arches in the middle, which are broken through in the lower third by four segmented arched windows. The four round arcades above are closed off by a three-pass arch.

Modern

As a rule, the East Frisian churches were also built in the traditional brick style in the 20th century. There were churches destroyed during the war, especially in Emden, and rarely in the countryside, as in Gandersum . In 1992–1995, the Johannes a Lasco library was built into the ruins of the Great Church in Emden . However, some churches suffered severe damage from bombing, such as in Leer ( Christ Church ), Ditzum and Twixlum , which were repaired after the war.

The sacred buildings of the numerous free churches in East Frisia that were built in the 19th and 20th centuries are usually traditionally designed and clearly recognizable as churches. Stella Maris (1931) on Norderney breaks new ground in terms of architecture and is committed to the New Objectivity style . St. Peter (1970) on Spiekeroog is designed in the form of a polygonal pyramid.

Bell towers

Due to the soft marshland, the bell towers of most churches were built separately so as not to endanger the nave if the heavy towers were tilted on the soft ground by the vibrations of the bells. An extreme example of this is the leaning tower in Suurhusen . Due to the strongly fluctuating groundwater levels and the bell vibrations, there was often persistent subsidence and liquefaction of the thixotropic (clay) soil up to fractures like the leaning tower of Pisa . Bells have been part of the equipment of Christian sacred buildings from the beginning, as the discovery of fragments of a bell in Etzel from around 1000, which had a diameter of 35 centimeters. After ridge turrets for the bells or wooden stacks of bells were used at the beginning , in the 13th century there was a transition to free-standing, usually simply designed bell towers of the "parallel wall type". In these bell houses, two, three or four parallel walls were connected by arches. As in Freepsum , Hinte and Loppersum, the buildings could be two-story and in the west of East Friesland were occasionally more architecturally designed with ornate gables and glare fields, such as in Strackholt . In Midlum (13th century), the parallel wall type is modified to three storeys and divided by three arcades each, a construction that is unique for East Frisia. They were usually placed at the southeast corner of the church, occasionally also at the northeast corner, in Petkum in front of the northwest corner .

There is also the "closed type". In Weener and Norden (1230–1250) a street separates the tower from the church. The gables in the north are particularly richly designed, below the small acoustic arcades with three round arched panels on each side, and in the gable triangles with narrow pointed arched windows in clover leaf panels. In the Krummhörn in particular there are bell towers of this type from the late 13th century, such as in Westerhusen and Visquard . The closed building type with its very simple construction has retained its shape for many centuries. Examples are the towers in Canum , Thunum , Resterhafe and Funnix (all from the 13th century), in Leerhafe (14th century), Stedesdorf (1695) and Upleward (1854). The west towers attached to the nave could accommodate high boxes for the local rulers and nobles. If these west towers were expanded for defense purposes, the building was given the character of a fortified church , as in the late medieval Overledinger churches in Esklum , Backemoor and Völlen .

The Reformed Church in Bunde and the Andreas Church in the north originally had two slender choir-flank towers from the mid-13th century, for which common models are assumed. The Vierungsturm in Pilsum (around 1300) and the choir tower in Eilsum (around 1250) are singular for East Frisia . From the Baroque onwards, but especially in the 19th century, western towers with a square floor plan and pointed helmets were preferred (Bunde / Ref. Kirche, 1840; Timmel , 1850; Weenermoor , 1867; Veenhusen , 1869). Occasionally, the tradition of building the bell house separately was retained, in the baroque ( Weener , 1738; Carolinensiel , 1776), classicism ( Grotegaste , 1800; Aurich / Lamberti , 1835), historicism ( Hatzum , 1850) and in modern times ( Gnadenkirche Tidofeld , 1948; Emmauskirche in Bunde, 1967). In Rhaude (14th century) and Ihrhove (15th century) the path to the church and the cemetery leads through the bell tower. The octagonal tower construction with an open lantern in Leer ( Great Church , 1805), Ditzum (1846) and Jemgum (1846), reminiscent of a lighthouse, is unconventional. Near the coast and on the Ems, the church towers of Marienhafe, Ditzum and the Norder Andreaskirche served as navigation marks.

See also

- List of historical churches in East Frisia

- Monastery landscape East Friesland

- Organ landscape East Frisia

literature

- Rolf Bärenfänger: Archeology in churches and monasteries in East Frisia . In: News of the Marschenrat to promote research in the coastal area of the North Sea . tape 46 , 2009, p. 29–34 ( online [PDF; 2.1 MB ]).

- Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches in the East Frisian coastal area . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1986, ISBN 3-925365-07-9 .

- Hermann Haiduck: Beginning and development of church building in the coastal area between the Ems and Weser estuaries up to the beginning of the 13th century . Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1992, ISBN 3-925365-65-6 .

- Peter Karstkarel: All middeleeuwse kerken. Van Harlingen dead Wilhelmshaven . 2nd Edition. Uitgeverij Noordboek, Groningen 2010, ISBN 90-330-0558-1 .

- Gottfried Kiesow : Architecture Guide East Friesland . Verlag Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz , Bonn 2010, ISBN 978-3-86795-021-3 .

- Justin Kroesen, Regnerus Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings . Michael Imhof, Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-159-1 .

- Robert Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . Soltau-Kurier, Norden 1989, ISBN 3-922365-80-9 .

- East Frisian Landscape (Ed.): Kulturkarte Ostfriesland . Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 2006, ISBN 3-932206-61-4 .

- Monika van Lengen: Islands of calm: Churches in East Friesland . Leer 1996, ISBN 3-7963-0335-8 .

- Ingeborg Nöldeke: The stuff that churches are made of. Granite, tuff, sandstone and brick are used as building materials for medieval churches on the East Frisian peninsula . 2nd Edition. Heiber, Schortens 2009, ISBN 978-3-936691-40-5 .

- Ingeborg Nöldeke: Hidden treasures in East Frisian village churches - hagioscopes , rood screens and sarcophagus lids - overlooked details from the Middle Ages . Isensee Verlag, Oldenburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7308-1048-4 .

- Hans-Erich Reineck: Landscape history and geology of East Frisia . Sven von Loga, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-87361-244-5 (Geological Excursions, Vol. 1).

- Hans-Bernd Rödiger, Klaus Wilkens: Frisian churches. Volume 1: In Jeverland and Harlingerland . Mettcker, Jever 1978.

- Hans-Bernd Rödiger, Heinz Ramm: Frisian churches. Volume 2: In Auricherland, Norderland, Brokmerland and in Krummhörn . 2nd Edition. Mettcker, Jever 1983.

- Hans-Bernd Rödiger, Menno Smid : Frisian churches. Volume 3: In the independent city of Emden and in the district of Leer . 2nd Edition. Mettcker, Jever 1990.

Web links

- Monika van Lengen: Churches and Organs . In: Ostfriesland Tourismus GmbH . Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- Doris Reuter: The Genealogy Forum . In: Genealogy forum . Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- Friederike Bungenstock, Klaus-Dieter Meyer: Erratic block churches of the East Frisian-Oldenburg Geest and the Ice Age theories

Remarks

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ a b Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, p. 17f.

- ↑ Menno Smid : East Frisian Church History . Self-published, Pewsum 1974, ISBN 3-925365-07-9 , pp. 11–18 (East Frisia under the protection of the dike; 6).

- ↑ Coastal areas like the Krummhörn were mostly Christianized in the Carolingian times.

- ^ Horst Haider Munske , Nils Århammar : Handbuch des Frisian: Handbook of Frisian Studies. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-484-73048-X , p. 543.

- ↑ Menno Smid: East Frisian Church History . Self-published, Pewsum 1974, ISBN 3-925365-07-9 , pp. 105 (East Frisia under the protection of the dike; 6).

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches. 1986, p. 153.

- ^ Bauverein Neue Kirche Emden eV: Bau-Brief . Issue 2, 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 27f.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 14f.

- ↑ The foundation of the church building was less stable when on clay soil or heather sods instead of fine sand fell back.

- ↑ See, for example, about the filling of the church hill in Ihrhove, which was surrounded by a ditch: Hans Joachim Albers, Heinrich Schaa, Heinz Schipper, Hermann-Josef Schleinhege: Ihrhove im Mittelalter. Archaeological, historical and scientific search for traces . 1Druck, Leer 2011, ISBN 978-3-941578-19-7 , pp. 176 f .

- ↑ When the Tergaster church was excavated in 2003, the foundation walls of the original apse were exposed. They are 0.77 m thick and are occasionally supported by boulders below.

- ↑ Christian Müller: Post-establishment and foundation improvement . Thesis. Weimar 2009 ( online , PDF), viewed February 8, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e Reineck: Landscape history and geology of East Frisia . 1994, p. 148.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Rolf Bärenfänger : Archeology in churches and monasteries in East Friesland . 2009, p. 30 ( online , PDF).

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 43f.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 46f.

- ↑ a b c Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, map in the appendix “Distribution of building and material types in the 12th and 13th centuries on the East Frisian peninsula”.

- ↑ Friederike Bungenstock, Klaus-Dieter Meyer: Foundlingsquader-Kirchen of the East Frisian-Oldenburg Geest and the Ice Age Theories , accessed on March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 22.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, pp. 10-12.

- ^ Hans-Erich Reineck: Landscape history and geology of East Frisia . 1994, p. 150.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 13.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 48.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 23.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Helmut Mudder: The most crooked church tower in the world - Old Church in Suurhusen , Suurhusen 2008.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Gottfried Kiesow: Architectural Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 284f.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 50.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, pp. 18-21.

- ^ Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, pp. 105f.

- ^ Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 107f.

- ↑ Gottfried Kiesow: Architectural Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 97.

- ^ Ortschronisten der Ostfriesische Landschaft : Eilsum (PDF; 46 kB), viewed June 8, 2012.

- ^ Ostfriesland.de: Sights in Bunde , seen June 8, 2012.

- ^ Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 104.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 150f.

- ↑ Ortschronisten der Ostfriesischen Landschaft : Pilsum, municipality Krummhörn, district Aurich (PDF; 51 kB), viewed June 8, 2012.

- ^ Reformiert.de: Ev.-ref. Municipality of Pilsum , seen June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Gottfried Kiesow: Architectural Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 223f.

- ↑ Gottfried Kiesow: Architectural Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 230.

- ↑ Michael Heinze (Rhaude.de): The Rhauder Church , seen June 8, 2012. Kiesow: Architekturführer Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 182, however, dates the choir extension to the 15th century.

- ^ Bauverein Neue Kirche Emden eV: Bau-Brief . Issue 2, 2006, p. 7f.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 157.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 54.

- ↑ Kroesen, Steensma: Churches in East Friesland and their medieval furnishings. 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, pp. 151-153.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 61.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 86.

- ^ Homepage of the Weener parish: History of our church , as seen on June 8, 2012.

- ^ Walter Hilbrands : On the history of the reformed church in Weener . In: Church council of the evangelical reformed community Weener (ed.): Festschrift 300 years of the Arp Schnitger organ . H. Risius, Weener 2010, p. 66 .

- ↑ Gottfried Kiesow: Architectural Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 109f.

- ^ Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 167.

- ^ Hermann Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 169.

- ↑ a b Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 66f.

- ^ Karl-Ernst Behre, Hajo van Lengen: Ostfriesland. History and shape of a cultural landscape . Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0 , p. 278.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Monika van Lengen: Rheiderland churches. Journey of discovery to places of worship from eight centuries in the west of East Frisia . H. Risius, Weener 2000, p. 21 .

- ↑ leer.de: Reformed Church , seen June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 138.

- ↑ The Great Church in Leer , as seen June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 135.

- ↑ Homepage of the Lutherkirche Leer: Church , as seen June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Van Lengen: Islands of Tranquility. 1996, p. 81.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia. 1989, p. 71.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Lamberti Foundation Aurich: Architecture , seen June 8, 2012.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 130.

- ↑ Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 72f.

- ↑ a b Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 73.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 173.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland . 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ a b Noah: God's houses in East Frisia . 1989, p. 74.

- ^ Ostfriesischer Kurier from April 30, 2010 ( Memento from April 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 143.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, pp. 143-146.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 148.

- ^ Haiduck: The architecture of the medieval churches . 1986, p. 20.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 159.

- ↑ denkmalschutz.de: Ev.-ref. Eilsum Church , accessed March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Kiesow: Architecture Guide Ostfriesland. 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Reinhard Ruge (text), Ev.-luth. Ludgerigemeinde Norden (ed.): The Ludgerikirche to the north. Norden 2000, p. 3.