Monthly pictures

Monthly pictures (also called monthly works ) are visual representations of the months of the occidental calendar put together in a closed cycle . Monthly picture cycles represent a classic theme of premodern European fine arts and are particularly prominent as part of the picture programs of the Gothic cathedrals , the late medieval book illumination and the secular wall decorations of the early modern period.

The monthly pictures are often closely related to the representations of the twelve signs of the zodiac . They are closely related to the four-part cycles of the seasons . They are assigned a decisive role in the development of post - ancient landscape and genre painting in Europe.

overview

The “classic basic form” of the monthly picture cycles contains the twelve representations of the months, which constitute an agricultural calendar in the broadest sense ( see below ) and to which the zodiac signs of the corresponding period are assigned. The design can be done schematically on a single page or as a four-, six-, twelve- or twenty-four-part cycle. The signs of the zodiac can be contrasted with the monthly representations as independent units, for example in their own medallions, but can also be integrated as far as desired into the monthly images themselves, for example as a scenic component. Through this connection of the seasonal activities with the processes in the sky, the earthly course of the year and the person acting in it were placed in the cosmic order set by God . The signs of the zodiac can also be missing, but this is far less the case than it appears: many illustrations in the literature "suppress" them because they were depicted spatially separated by the artist (e.g. on the opposite page in a handwriting ).

While the earliest cycles initially symbolic or with specific attributes fitted, used frontal half- or full figures, developed during the Middle Ages slowly small genre scenes, mostly by month typical, existentially significant for the respective time country -, hunting -, forestry - or domestic operations, later also enjoyable activities. In both forms of design reference is made to the seasonal vegetation cycle in a variety of ways by referring to it with various clear symbols, attributes or the illustration of seasonal production processes - the so-called “monthly work” or later “monthly joys”.

The context ( sacred or profane ), the purpose ( didactic or ornamental ) and of course the individual intentions of the artist or client are decisive for the specific characteristics of a cycle . But even if the monthly picture cycles between the early Middle Ages and the middle of the 15th century show individual differences in content and composition for each month, the overall concept remained remarkably uniform despite recognizable differences.

The ripening, harvesting (slaughtering) and the further processing of natural products during a normal course of the year determined the design of the early calendar orders and thus the monthly picture cycles. Since the individual compartments soon for the months right with seasonal fixed subjects were connected to new elements were initially difficult to enforce. Due to the constancy of the motifs, the monthly pictures thus form an independent iconographic type. Stylistic and compositional changes over the centuries, however, also indicate a gradual further development until after 1420 the content and intentions began to change more strongly.

With the Très Riches Heures (around 1412/16) the character of the cycles changed fundamentally. The early monthly pictures had shown more or less static people or personifications with attributes or symbolic functions, from which small actions had developed, which above all brought representative seasonal work into the picture for the respective period. In this book of hours by the Duke of Berry , for the first time every single picture of the month took up an exclusive, complete page in a manuscript . Even if such individual sheets remain recognizable as part of an overall concept that can only be understood in context, the overall cycle can no longer be directly grasped by the arrangement on individual pages (similar to the calendar sheets, which however still include the monthly pictures in their own special context) . However, such comparatively large-format picture systems also led to newly available design spaces that allowed the artists to break up the traditional topic specification with additional motifs, for example in the background of the pictures. In the centuries that followed, the concept of elaborated, expanded and more variable scenes in the manuscripts gradually gained acceptance. The motifs - especially in panel painting - slowly detached themselves from the context of the monthly cycles and developed further as independent subjects.

history

antiquity

The early civilizations like to visualize the time rhythm of the annual cycle by depicting the seasons or signs of the zodiac. The earliest representations of individual months are only known from the 1st century AD . Caesar's calendar reform of 46 BC Chr. Was the decisive factor in the development of a European tradition of monthly pictures, since the replacement of the lunar month by the solar month simplified and standardized the agricultural planning and organization processes, which are always dependent on the solar year.

The earliest monthly picture cycles are divided into two original lines of tradition. The Greek tradition gives the sequence of " pagan " liturgical festivals in the annual cycle. Fragments of the oldest monthly picture cycles that are still preserved today can be found in Athens , for example as an Attic frieze on the metropolitan church of Hagios Eleutherios ( Panagia Gorgoepikoos ). Each month, gods and cult activities were assigned, which suggests a function as an illustrated festival calendar . Even then, the Dionysus festivals, which revolved around vegetation and harvest, held a special position. The tendency towards the personification of abstract terms and ideas later made it easier for Christianity to accept and adapt , as this later made it easy to combine spiritual meaning and Christian-religious symbolism .

The Roman tradition consists mainly of profane motifs of agricultural work, which are based on bucolic scenes. The representations were probably based on the enthusiastic longing for the ideal of a "simple" and "natural" life in the country. They were often part of the furnishings of bourgeois Roman villas and thus served primarily decorative purposes. The necessary prerequisites for a general interest in monthly pictures had been created by the Roman clip-on calendars, which had already used pictures of the planetary gods and signs of the zodiac as symbolic rulers over days, weeks and months (chronocrators) .

Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

The basic prerequisite for the continuation of the monthly painting tradition and its Christianizing transformation in the early medieval manuscripts was the partial preservation of educational and cultural assets of antiquity in the West. The calendar from 354 (also called Chronograph des Philocalus or Fasti Philocaliani ), which has been preserved in several copies since the 9th century and which has no visible Christian influences, plays a key role . It represents the earliest work, which, in addition to a calendar, also includes a twelve-part cycle of monthly pictures, which is accompanied by four-line explanatory verses of the month .

The protagonists of the ancient festival cycle have not been replaced by Christian symbols, but by religious “neutral” figures and attributes of the seasonal works. This was possible because the original festival circle had already referred to seasonal conditions. A “Christianization” of the meaning of the overall context of the monthly picture cycles only took place very gradually in the course of the following centuries. The development tended increasingly towards the creation of small scenes that were characterized by agricultural work in the broadest sense.

However, this development from a directly sacred meaning to (superficially) rather profane themes did not prevent the images of the month from being integrated into liturgical manuscripts - apparently as a symbolization of earthly time . This context of use also testifies to the great importance of the natural rhythm of the year and the seasons for the fulfillment of life in the agrarian society of the early Middle Ages.

The miniatures in two Salzburg manuscripts from around 818 ( Clm 210 and Vienna, ÖNB , No. 387) are among the oldest known monthly picture cycles in early medieval manuscripts . In a Byzantine Ptolemy manuscript from the Vatican (Rome, mid-9th century), the Carolingian copy of an ancient manuscript (the so-called Leiden Germanicus ) shows the transition from representative personifications to monthly labor.

An important pivotal point for the development of the monthly pictures is the martyrology of Wandalbert von Prüm (created after 850), which like the calendar of 345 also contains monthly poems. Other important manuscripts that show monthly picture cycles are the Sacramentary of Fulda (10th / 11th century, SBB-PK , theol. Latin 2 ° 192), the Ms. Cott. Julius A VI ( Winchester , 11th century; London, Brit. Mus. ) And the festival calendar of Saint-Mesmin (around 1000; London, Brit. Mus.); later also the landgrave psalter (13th century; LB Stuttgart ) and Elisabethpsalter (13th century; Cividale ).

High Middle Ages

An important literary influence for the high and late medieval monthly pictures is the agricultural handbook of Palladius from the 4th century, which dealt with the work of the individual months and often during the Middle Ages, also by scholars such as Albertus Magnus , Vinzenz von Beauvais or Petrus de Crescentiis , was used. It has survived in over 60 manuscripts and has even been translated into various vernacular languages.

In northern Italy and France, the monthly representations have been realized since the 12th century, primarily as part of the large portal programs of Gothic church buildings; very often they appear together with the signs of the zodiac in a prominent position as drapery sculptures in the arched area of an important portal . Art History major cycles are found in central western architectural monuments of the Middle Ages as the Amiens Cathedral (western facade, left side portal to 1230), Autun Cathedral , Cathedral of Chartres (eg Portail Royale , tympanum, ca. 1145-55), Abbey Saint- Denis (western vestibule, approx. 1140/50) and Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris (western facade, Marienportal , approx. 1220/30), at Reims Cathedral , at Strasbourg Cathedral (western building, walls of the right portal, begun in 1276), at St. Mark's Basilica in Venice (main portal) and at the basilica Sainte-Marie-Madeleine of Vézelay (vestibule, central portal, relief of the tympanum, consecration of the choir 1104).

Monthly representations can also be found inside the churches, for example as wall paintings, as part of the carvings on the choir stalls or other furnishings, such as the font from Eschau (Strasbourg, Musée de l'Œuvre Notre-Dame ).

Thanks to their circular shape, which can best accommodate a closed, basically endless cycle, the large rose windows of the Gothic cathedrals were a particularly suitable place to illustrate the course of the year with the monthly representations. The geometric structure allowed the synoptic representation of the different cosmological systems of the Middle Ages, for example the parallelism of the course of the year to liturgical salvation history , month saints , apostles . The most prominent example of this genre is the rose window in the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Lausanne (1235), which offers an encyclopedic representation of medieval cosmology in a circular scheme. Other art-historically significant glass windows can be found e.g. B. in the cathedral in Chartres. Month pictures are in northern Italian floor mosaics with concentric calendar display of the 11th and 12th centuries obtained, for example, in San Michele Maggiore in Pavia , in the Cathedral of Otranto , in the Basilica of San Savino in Piacenza (colored mosaics, crypt , 12th century) and in the cathedral in Aosta . In the 12th and 13th centuries there are also significant reliefs in northern Italy, such as the original first column gallery of the Baptistery in Parma (after 1196) by Benedetto Antelami or the cycle of reliefs on the Basilica of San Zeno in Verona ( portico ). Wall painting (no calendar) dominated in Germany at this time. An example of a painted monumental calendar is the triumphal arch in Notre-Dame de Pritz , Dep. Mayenne (2nd half of the 13th century).

Late Middle Ages

The newly installed clocks in the churches and town halls have also been equipped with cosmological or astrological programs since the late Middle Ages . Examples of images of the month can be found around the dial in Rostock's Marienkirche (1379 or 1472) or (later) on the town hall in Prague . These cycles correspond to traditional iconography.

After the sacred, the monthly picture cycles also conquered the secular building in the late Middle Ages. They were now permanently present in public space. An outstanding example are the 24 depictions as part of the program of the Fontana Maggiore fountain in Perugia (1275–1278), which were designed by Niccolò and Andrea Pisano . The Zurich town house to long cellar probably possessed since the early 14th century by a decoration with monthly pictures, as the monastery Wienhausen . The Trieste fresco cycle is one of the most important murals of the International Style around 1400 . The paintings that have been preserved suggest a close relationship to the image programs of the manuscripts and cathedrals.

After the city hall church had replaced the Gothic cathedral, monthly images were created primarily for manuscripts, often as part of illustrations of the calendar boards in calendar works, books of hours and prayer books . This change of media caused a fundamental change in the function and design of the cycles. They became enriching, luxurious book decorations that could be used for private contemplation of the course of the year in pictures. In addition, the aim was often to have a visibly entertaining effect. These aspects can be clearly seen in the case of the miniatures in the Duke of Berry's books of hours . The monthly pictures of the Très Riches Heures (1412/16) with the exact reproduction of the royal castles "for their own sake" are also among the first "realistic" depictions of landscapes and buildings in Europe since antiquity.

15th to 18th century

After illuminated manuscripts of the Eclogues and the Georgica of Virgil had been produced as early as the beginning of the 15th century , which contained miniatures of an idealized country life, the enthusiastic idea of "simple country life" came back into fashion - not unlike the Roman tradition . Subsequently, based on the developments at the French court , the depictions of the “monthly work” in the richly illustrated books of hours from Flanders were gradually replaced by scenes with “monthly joys”.

A one-sheet calendar by Johannes von Gmunden from the 2nd half of the 15th century in the woodcut technique (misleadingly called the xylographic calendar from 1439 ) offers the first known print of the monthly pictures. Soon afterwards, the number of massively printed, often inferior quality and greatly simplified monthly picture cycles in cheap single-sheet and farmer's calendars grew in numbers.

At the end of the 15th century calendar manuscripts and prints were produced, richly endowed with medical, astrological and cosmological images. Important production sites are Strasbourg, Leipzig and Nuremberg; Countless manuscripts are known from Upper Germany. This century saw the most important calendar reform of modern times, which also brought the agricultural harvest year and the sky year (star circle) back into line and signaled the Catholic Church's global claim to interpretation and validity. Because from 1582 there was a hesitant adoption of the Gregorian calendar in Europe and with the consequences of the expeditions beyond.

Art-historically significant Month of cycles of this period are the earlier than Sforza Hours called Black Book of Hours of Charles the Bold , the last Duke of Burgundy, which originated in Flanders in 1470 (Vienna, Austrian National Library, no. 1856), the pictures of Lucas Cranach . Ä. according to the calendar of Philocalus as well as the working calendar for the year 1483 from the office of Peter Drach in Speyer, which contains monthly work ascribed to the master of the house book . Also known are the illustrations by Urs Graf zu Kunsperger's calendar and the pictures by Hans Sebald Beham for the Calendarium historicum (1557) by Michael Beuther .

In addition to the tradition of calendar illustration, which reached its peak with Simon Bening , several graphic cycles from Germany are known from the 16th century , such as the copper engraving cycle Das Bauernfest by Sebald Beham, which presents a “twelve month dance”. Pieter Bruegel the Elder Ä. translated the monthly pictures in his famous (probably) six-part cycle The Seasons into panel painting. He combined the representations of landscape and seasonal changes, taking up and citing countless elements of the monthly representations.

Due to the poor tradition, it can only be assumed that countless tapestries from the early modern period probably had cycles of monthly pictures. From the 17th century there are tapestries from the Netherlands and occasionally from Italy - and paintings are known to follow, such as B. a tapestry based on designs by Jan van den Hoecke from Brussels around 1650 (now Vienna). The Nuremberg JB Herold made twelve gun barrels ("monthly barrels") around 1708 , each of which bears a different picture of the month (Vienna, Heeresgesch. Mus. ), Similar gun series were also cast for the Electors of Saxony (today Königstein ).

Further reception

At the beginning of the 18th century, the tradition of monthly picture cycles slowly disintegrated in favor of the four-part cycles of the seasons, which had coexisted parallel to the monthly representations since antiquity and influenced each other iconographically. Since then, only a few cycles of importance have been known, such as the cycle of medallions at Prague City Hall by Josef Mánes from 1864, the idyllic woodcuts by Moritz von Schwind for the calendar of 1844 or the depictions by the Viennese Anton Krejacar from the 20th century.

The individual subjects had often become independent in the early modern period and established their own iconographic traditions that were soon no longer directly related to their origins. Apart from “neighboring” pictorial traditions, which could have had a compromising effect on the representations, some motifs and motifs are also of downright “ archetypal ” quality for European culture : depictions of the sower, the plowing farmer or the hunt cannot automatically appear on the monthly pictures but were also always productive as part of a collective image memory independently of this tradition.

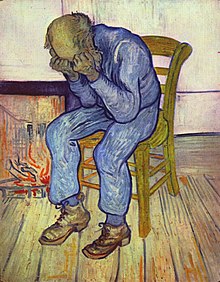

Modern examples of a revival of the classic iconography of the month, such as John Collier's May ride of the Guineverle, are rare individual cases. A particularly notable case is Vincent van Gogh's On the Threshold of Eternity from 1890. Here the artist takes up what is perhaps the most frequently depicted motif of the monthly pictures, the “thermal image”. If a cycle was used at the same time to allegorically depict the ages of man, the cold motif was also always the image of old age. In the Middle Ages, this was associated with the qualities of cold and dry (the element earth , the "evil" planet Saturn , the disease and the temperament of melancholy ); it was assumed that old people would be cold and happy to sit by the fire. Van Gogh took up the old iconography in this sense and reinterpreted it.

A comprehensive art-historical review of the monthly painting tradition is still pending. Therefore there is a lack of a binding systematization of the entire tradition and an adequate overview of the historical development lines of the monthly series and their reception up to the present.

Monthly motifs

The assignment of the activities necessary for food production in nature to the corresponding month has occupied the largest part of the cycles since the early Middle Ages. Traditional work in agriculture and forestry is heavily dependent on the weather, which means that the exact dates can vary considerably. It can be assumed that the monthly cycles reflect long-term average experience. Furthermore, the climatic differences in the various regions of Europe are responsible for the deviations in the sequence of agricultural work processes in the cycles. The processes of the "German" series of the Middle Ages correspond to the local climatic conditions of the time. However, there is no binding order in the adaptable cycles.

Of course, the limitation of the representation to a selected activity for one month does not correspond to the reality of life. Until the late Middle Ages, however, the formal principle restricted the images to a single topic per month and also largely to elementary processes. They are “simple” activities that lead to “simple” earnings. In this way, however, a compartment occupied by a certain monthly work was blocked for other content. This also led to certain quasi-automatisms of the monthly work sequence based on the natural sequence of work processes.

Thematic groups

loaf

The monthly pictures, which deal with grain production, occupy the largest space in the medieval cycles. The first plowing and sowing of summer grain usually took place in March - the division of grain cultivation into summer and winter sowing required plowing of the fields at that time.

In August, the "harvest moon", the grain was usually harvested again. Typical of the harvest is the reaper who, equipped with a hand sickle , firmly grips and cuts the ears - a method in which particularly few grains are lost. The sometimes torn clothes of the workers indicate that they belonged to the lowest social class of day laborers who performed this activity. They often walked barefoot or only in pantyhose-like leggings so as not to trample the valuable grains. They usually wore a whetstone on their belts in a special sheath that was filled with water. The scenes can also show piles of straw being raked together and sheaves tied. Later, the depiction of a break from working in the field, which can eventually turn into a lavish, festive picnic followed by a nap, takes up more and more space.

In September or October, plowing takes place again and part of the harvest is sown again as winter seed. Here, a sower is often depicted wearing a sheet over his arm, from which he throws the seeds into the freshly plowed furrows. A sack of seeds is usually close by. Often the field is not plowed, but the sowing is worked into the ground with the help of a primitive frame harrow dragged by a draft animal to protect it from the birds, which can also be shown in the picture.

In addition, in the autumn months threshing the grain with flails and cleaning the threshed grain from the chaff by throwing it up with shovels or special baskets, and in the winter months baking the bread - usually by pushing the dough blanks into an open oven with a bread pusher be. Finally, in the January or February picture, the grain usually appears prepared, e.g. B. as a loaf of bread or rolls on the (festive) table again.

Wine and fruit

The production of wine has two relatively fixed places in the cycle: the pruning and grafting of the vines in April or May and the grape harvest in September or October. In addition, there are sometimes also the work on fruit trees and the fruit harvest as motifs.

The corresponding monthly picture in spring, which is located in the vineyard or in the fruit tree population, originally only consists of the representation of a single person deep in the work with a tool. Over time, the scenes become more and more extensive, often the activities in the vineyard and on the fruit trees are brought together in a single picture. The pruning of the plants, various earthworks, fertilizing as well as the transport, the setting and the subsequent fastening of the vines to the vine stakes can also be included. The grape harvest is shown either as picking, pressing or a combination of both processes. The harvesting of the grapes is presented early on as group work based on the division of labor. The berries are harvested by pickers and collected in baskets or carrying boxes , which are brought to the press by porters or on wooden carts. Sometimes the wine press in large vats - almost always the traditional form by crushing with the feet, very rarely also mechanically - and the filling of the must into barrels can also be seen in the picture. Only later are the bottling of the wine, the so-called test drink, and the sale of the end product discussed.

Wine not only served as a symbol for the high standard of living of the landlord , but was also an indispensable part of the altar sacrament for the clergy . The vine can always be understood as a Christian symbol, all the more so in a cycle that focuses on the basis of the other sacrament of the altar, bread. The illustration of the sower can always be associated with the parable of “Christ as the sower” ( Mk 4,3–8, Mt 13,1–8, Lk 8,5–8).

flesh

The scope of the subject complex meat production fluctuates considerably in the cycles. The ( acorn ) fattening of pigs is often assigned to the month of November . The pictures show the pigs driven into the oak forests, and you can often see how the shepherds use long poles to cut the acorns from the treetops.

In December, cattle or pigs are usually slaughtered or sold and sausages are prepared . The most common way to stun - sometimes even a cattle - is to hit the skull with a blunt object (back of an ax, hammer). An alternative scene shows the butcher kneeling on the pig while cutting the animal's throat. A helper usually collects the draining blood in a long-handled crucible for further processing. Straw and brooms are often already ready to scarf and remove the bristles. A table and various butcher's tools can also be part of the scene.

Another motif for the winter months is hunting . Mostly the killing of game ( wild boar , deer ) or the return with the prey is shown, often on horseback and with a pack of hunting dogs . Some cycles also depict bird hunting , fishing with nets or traps or trapping.

The mowing , i.e. the hay harvest, which was used to produce (winter) cattle fodder and thus indirectly to obtain meat, is shown in June and July. The cultivation of the soil does not apply to the cultivation of grain, which would have been too late for the summer and too early for the winter. As the name "fallow month" suggests, plowing in June is used to break up the fallow areas that are used as pasture for cattle. Keeping them free from unwanted weeds and grasses required plowing up to three times between June and September.

In the winter months, the preparation of meat or sausages (on the open hob) or their consumption at the table is sometimes shown.

Wood

Felling and carrying wood as an activity in one of the winter months of November or December is rather loosely anchored in tradition. Logging in the forest - like hunting - cannot be assigned to the rural-agricultural sphere. In the forestry profession, wage laborers were usually employed, as farmers obliged to do labor were hardly supervised and could have caused considerable damage in the sensitive forest. The workers are shown at work with long-handled axes or hand hatchets. Sometimes a team of horses is ready to transport the wood in a large stake wagon .

In the “cold motif” of January or February there is always an (often older) person who - often covered in thick covers - warms himself by the fire. This so-called Janus warms itself with the fire -type shows the use and consumption of the obtained product "wood" for heat generation. The motifs of the winter feast and the fireplace can also coincide. In later cycles, this double motif is then transformed into a "cozy" domestic, often familiar scene. January and February can also be used for a summarizing “preview and overall view” of the annual cycle, as the artist incorporates references to all topics of the monthly representations in this beginning of the year picture.

Later additions to the topic include chopping and sawing firewood in January and transporting wood by donkey or ship.

Festivals

As special months, May and April break through the sequence of works with the topos des locus amoenus . In the garden or in cultivated nature, the troubles of the mere supply of basic foodstuffs are transcended. The May picture is ornament and a station of relaxation and joy within the cycle.

The basic form of this picture is the representation of a person holding a green twig or two in his hands. These so-called April floridus figures (whose history goes back to the ancient Robigalia ) can also be found in the Tacuina sanitatis and in the iconography of the four seasons. Flowers and green leaves have conventionally carried the meanings of renewal and rebirth with them since ancient times .

Another type is the courtly May ride, a custom that was mainly cultivated in the late Middle Ages: on May 1st, people went on horseback in small groups to welcome spring. Traditionally, people dressed in green robes and equipped themselves with green branches. This motif was particularly liked to vary and embellish: the later cycles show lovers, boat trips, picnics, dances and even tournaments ; musicians often accompanied the activities of the May picture. Based on these representations, the amusements and beautiful moments of the year have been increasingly emphasized in the cycles since the end of the 15th century. In the 16th century, the focus often shifted to the bourgeois-urban sphere, with gardening in the spring being a particularly popular scene.

The winter time, which is associated with fear of hunger, cold and illness, was "defused" in the monthly picture cycles in January or February with a festival of richly decorated tables. The January iconography with the often double-headed Janus is based, among other things, on the popular New Year's custom of providing the tables with plenty of food on this day and leaving them untouched overnight, in the analogy wish that the table would be just as richly loaded for the rest of the year may be. The winter festive table is always richly set for contemporary conditions, bread and poultry are almost always found, often valuable crockery, salt kegs , pots and cutlery made of metal. Often, due to the valuable equipment and the available house staff, it can be seen that the meal takes place in rooms that are either assigned to the sphere of the patricians or the nobility. What is striking is the frequent addition of dogs and cats to the scene, which challenge symbolic-allegorical interpretations. Later additions also put depictions of the Emmaus supper and domestic scenes of the Holy Family in this context.

Others

The books of hours of the 16th century begin to expand the original subject of the monthly picture cycles considerably. They show largely idealized contemporary urban and village life in small genre scenes. These are initially compared to the actual monthly picture on the opposite page in the calendar sections, which generally comprise two pages per month during this period. This was often done using groups of images that could be arranged next to and on top of one another by appropriate framing or clever spatial division of the page. Later they became increasingly independent or combined with the classic monthly representations and formed the material for early genre painting, especially in the Netherlands .

New scenes since around 1500 include going to church in winter, snowball fights, sleigh rides and hustle and bustle on frozen ice surfaces, work in the bourgeois garden at the house, various games for children, young people and adults (sports games) and bathing fun; but also extensions of the work such as milking and buttering, the fruit harvest, the sheep shearing and the cattle drive, the hunt for birds, rabbits and fish as well as the transport or sale of goods.

It is also important to record which groups of people and activities cannot be seen in the monthly pictures: craftsmen , for example, only appear very rarely and, up to a certain point in time, do not appear in the cycles at all; Even if there are examples of images of sheep shearing in monthly pictures from Carolingian times, the concerns of (cattle and) sheep breeders have only been regularly included in the cycles since the end of the 15th century. Depictions of religious festivals, which were celebrated in abundance in this epoch, can never be found in the actual monthly picture tradition, apart from extremely rare cases.

People

In the history of artistic portrayals of farmers in Europe, far into modern times, they were portrayed as anonymous, socially subordinate people who earned their living with the help of work in rural areas. They can usually be recognized by their specific devices and workhorses and their often simple, brown or gray clothing. In art, the status of the peasants was traditionally represented in a way that did not serve their own interests, but rather reflected the wishes, fears and attitudes of the client - that is, the “powerful” and wealthy. In the late medieval monthly picture cycles, the rural population functioned primarily as a decorative accessory intended to entertain the better-off public, freed from the actual toil of agricultural work . However, it is surprising that until the 16th century the farmers seemed to work completely independently in the pictures without any recognizable supervision.

According to Gen 3:19, hard field work is the man's job, so the absence of women in the early monthly cycles is not uncommon. It was only later that they were shown, without misogyny , primarily within their domains at the time, i. H. with housework , textile production , food preparation and childcare . As part of rural work patterns, they were occasionally shown up to the 12th century for spinning , milking, sowing, harvesting and poultry farming.

As far as can be seen, working children are rarely seen in the early monthly pictures, but the introduction of this motif into the tradition in the 15th century can be seen as a realistic element, as it could possibly have reflected actual conditions of the division of labor . The portal sculptures had already revealed differences in the sociological structures by showing a division of tasks between younger and older protagonists. Here, however, one must always reckon with the mixing with the pictorial tradition of the ages, so that the old man in January or the young man in May represent an allegorical element and not a sociological fact. For the later period it is particularly true that the presence of children and animals can in a certain way contribute to the “belittling” of a scene.

Landscape and architecture

In the 14th century, the landscape began to emancipate itself in European art, although initially it is only present in fragments. In the 15th century it became more and more important, especially in panel painting. With the monthly pictures in the Limburg brothers' books of hours , the genre of the “architectural picture ” begins, which aims to reproduce a particular building as accurately as possible and with correct perspective. Both in the tradition of the monthly cycles and in parallel in Sienese painting, the hunting books and bestiaries of the time, a new sense of precise observation of nature and perspective of spatial perception developed, which is fully developed with the Breviarium Grimani (around 1510).

Even if botanically assigned flowers and fruits or city panoramas with recognizable building views showed a clear tendency towards naturalism , the symbolic meaning of natural things in painting was retained for a long time (for example in the still lifes or the Dutch genre scenes well into the 18th century ). A characterization of the images as "realistic" can therefore generally only refer to the representation of the people and their immediate activities or equipment. Italian scientific works with exemplary character, such as the Herbare or the Tacuina , on the other hand, often showed illustrations with a considerable naturalistic claim, that is, based on a precise observation of reality .

Monthly verses

Images of the month are often passed down in connection with popular verses of the month. In the calendar of 354 , Latin verses of the month accompanied the images of the month. In the cycles of early medieval manuscripts months poems are to be found, such as the Latin calendar poem De duodecim menses nominibus signis culturis aeris que qualitatibus of Wandalbert Prüm or couplets of Carmina Salisburgensia . There are also pictures of the month at Cisiojanus -Merkversen, which appeared in the 13th century and used as calendar donkey bridges to help date the immovable saints and holidays of the Roman Catholic Church.

The so-called Graz monthly rules , an early Middle High German translation of versified Latin dietary regulations for the twelve months, which are considered to be the forerunners of the German-speaking Regimina sanitatis of the late Middle Ages, were Germanized again in the 14th century after they were soon forgotten, around 1200, whereby they are closely related to of the medieval tradition in jano claris . The beginning "Escas per janum calidas est sumere sanum" was translated in the late Middle Ages as "In the jenner is healthy / warm food every hour" . These rhymed twelve-month rules are thus a very simple health regime, in which each month is represented by health rules in the form of a hexameter divided into two by rhyme . These are linked to the short verses of the month given below, the contents of which - if the text and picture were handed down together - usually coincide with the corresponding picture of the month, i.e. the sequence and contents of the pictures in the cycle were then determined by the text stanzas .

I am called Jenner / Großtrunck sint me well known.

I hate Hornung / Gestu naked, you regret it.

It is me, hailed Merz / I raise the plow.

I, Apprill, in the right place / The grapevines will despise.

Here I go, proud May / With delicate flowers some lay.

I am called the fallow moon / The plow must be in my hand.

Which ox will now pull / To whom I will give Heus vil.

Now wolauff in the ears / Those who want to learn to cut.

Good Mosts I vil / Whom I want to give.

In all the holy names / sow I was called new seed.

With Holcz one should apply / The winter begins to approach.

I will advise my house with sausages and bratts.

The Latin models of the verses of the month and the health rules were also often added to the pictures in the manuscripts and early prints. Conversely, the monthly pictures were also used to illustrate the extremely widespread dietary treatises, which were structured according to the twelve-month principle (Regimina duodecim mensium) , and were thus placed in a completely new, namely a preventive medical context.

Similar, widespread verses are known from the English-speaking world, which were also passed down in connection with the monthly pictures and which correspond very clearly with the corresponding motifs of the contemporary cycles:

| January February Marche Aprile Maij Junij Julij Auguste September October November December |

By thys fyre I warm my cell phones; |

By this fire I |

Even in later centuries pictures of the month were often accompanied by rhyming texts, especially the series in folk and peasant calendars and copper engravings . These verses were, however, Latin or vernacular new poems of various kinds that do not go back to this old tradition.

Function and meaning

Monthly picture cycles are defined by two complementary elements: firstly, the representations of the signs of the zodiac, which form a clearly defined sequence of time periods, and secondly, the representations of the months, which, as a “human factor”, reflect the activities assigned to them on earth. The relationship between the images of the month and the signs of the zodiac embodies the contrast and the mutual relationship between the earthly (sublunar) and the heavenly (supralunar) spheres.

The actually structureless time , which cannot be represented directly graphically, is brought into order with the help of this complementary connection of elementary activities and the twelve months . The joint representation of the earthly and the heavenly allows the perfect illustration of the medieval conception of the connection between microcosm and macrocosm . Such schemes complete the medieval cosmological representations of the divine order of spatial relationships - the model of the spheres (Sphaera) - through the concretization of the divine order of the temporal relationships that God Noah in Gen 8:22 (“As long as the earth stands, seed should not cease and harvest, frost and heat, summer and winter, day and night ”) after the flood .

The choice of concrete work instead of abstract personifications e.g. B. at the cathedrals points not only to the role of earthly time , but also that of earthly work for the individual and collective path of salvation . The ascending and descending rhythm of the (profane) year becomes visible through the positioning of the monthly pictures in the archivolts of the large portals, at the same time the cyclical recurrence of the periods and their relation to cosmic processes and the history of salvation (the central events of which were mostly shown in the tympanum) . The civil year and the church year , the reality of life and biblical history are linked. The publicly viewable cycles of the months thus offered a spiritual lesson for members of all classes . Only the change in function and meaning caused by the media change from the buildings to the manuscripts led to the fact that the cycles could also serve as decorative accessories in other contexts.

The fact that the work portrayals are limited to those production processes that are related to the life world and interests of the client - namely the clergy and nobility - suggests that the monthly pictures cannot be a pure illustration of the rural working year . The cycles do not deal with a uniformly assigned field of work: In the Middle Ages, viticulture and timber industry were not part of the peasant sphere, but were part of the estate or monastery economy. Monks, on the other hand, were in principle unable to perform all of the monthly work shown because of the hourly prayer that had to be observed . Hunting and riding in May were reserved for the nobility. Thus, the qualification of the monthly pictures as a “peasant work calendar”, which was often read earlier, is a failure, because the activities are neither limited to the tasks of the peasant class nor to the actual agricultural sphere.

The representation of profane work in a prominent place in Christian art , often even as part of central works of medieval Europe, was justified by two considerations: on the one hand, physical work was increasingly viewed as a complementary addition to intellectual work, both of which mitigated the consequences of the Fall should and contribute to the salvation of man. The spiritual work could alleviate the spiritual distress, the physical work the physical distress; it was also a reminder of the human disobedience to God in Gen 3 :17ff. ("Cursed be the field for your sake. With hardship you shall nourish yourself from it all your life.") . At the same time, the increasing appreciation of physical labor, which was promoted by the growing monasticism, resulted in a new understanding of agricultural production for the community. Both led to an acceptance of the practical work, which allowed a representation in the picture.

The "embezzlement" of all the ordinary elements of the medieval pantry such as cabbage, beans, leeks, peas or lettuce in the cycles also indicates that at least in the early medieval cycles it was not primarily about the satisfaction of basic needs, but that there Emphasis on the production of bread and wine in connection with the slaughter process could be interpreted as a subtle religious allusion to the Eucharist .

The visual design of the work in agriculture, which was associated with a lot of effort and dirt, in an aesthetically pleasing form was always associated with difficulties for the artists. Therefore, either the activities were strongly stylized or, in later times, the enjoyable moments (especially the breaks) were emphasized. For the entire tradition, however, it applies without exception that all real social, economic or logistical problems have been systematically excluded. The weather is consistently good, the workers always have the right tools at their disposal, problems or even accidents are never shown. The monthly work takes place in a calm, well-ordered idyll in which people seem to have found their lost paradise again.

The conception of the medieval monthly pictures as “ everyday scenes” or artistic “snapshots” is naive, because the laborious production processes associated with the annual cycle were brought into a form by the artists that should paint the satisfactory picture of a harmonious world and a well-ordered society . The apparent realism of the cycles is therefore deceptive, as the genre-like monthly pictures are more close to the tradition of the “romanticizing” transfiguration of country life (“ideal world”). As a fiction , they can only be used as a historical source , also due to their often purely decorative use, for the medieval world with the greatest reservations, for example in detail for agricultural historical realism . The use of the monthly picture cycles to illustrate an alleged "everyday life in the Middle Ages" is not permitted, at least from a source research perspective.

See also

- Cycle of the months (Trento, around 1400), monthly pictures in the Palazzo Schifanoia (Ferrara, 1470), monthly pictures of the Très Riches Heures (1410–1416)

- Shepherd poetry , agricultural history , food culture in the Middle Ages

- Lunar calendar (astrology)

- Calendar

- Tacuinum sanitatis , Hortulus Animae (landscape and garden depictions)

literature

Overview representations

- Walter Achilles: Monthly picture cycles in Hildesheimer splendid manuscripts of the 13th century. (= Sources and documentation on the history of Hildesheim. 14). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 2003, ISBN 3-8067-8595-3 . (A well-founded analysis of early monthly picture cycles from an agricultural historical perspective. The posthumously published, art-scientifically convincing little volume impresses with a wealth of surprising results)

- Shane Adler: Months. In: Helene E. Roberts (Ed.): Encyclopedia of comparative Iconography: Themes depicted in works of art. 2 volumes. Chicago et al. 1998, ISBN 1-57958-009-2 , pp. 623-628. (A chronological representation of the development of the iconography of the months, which extends beyond the tradition of monthly pictures. Contains a helpful extensive list of important works of art)

- Curt Gravenkamp: Images of the month and signs of the zodiac on cathedrals in France. (= The Art Mirror ). Scherer, Willsbach et al. 1949, OCLC 257570950 .

- Wilhelm Hansen: Calendar miniatures of the books of hours: Medieval life in the course of the year. Callwey, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7667-0708-6 . (The German-language standard work, which offers an extensive, thematically sorted collection of images, unfortunately only a few color tables. In a comment section, all images are discussed sorted by handwriting and location. An alphabetically structured image lexicon makes this extensive volume particularly useful. In terms of content, only a few Make something out of date)

- Bridget Ann Henisch: The Medieval Calendar Year. Pennsylvania State Univ. Press, University Park, PA 1999, ISBN 0-271-01904-2 . (A deeply in-depth, easily readable historical mentality investigation of individual questions of the late medieval tradition of monthly pictures with many illustrations. Also deals with questions of gender studies. In the meantime, the 2nd edition has been published and in the English-speaking world it is practically a standard work)

- Derek Pearsall, Elizabeth Salter: Landscapes and Seasons of the Medieval World. Elek, London 1973, ISBN 0-236-15451-6 .

- Teresa Pérez-Higuera: Chronos: Time in the Art of the Middle Ages. Echter, Würzburg 1997, ISBN 3-429-01941-9 .

- Gerlinde Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni / Monthly pictures: From antiquity to romanticism. Gursky, Halle 1999, ISBN 3-929389-30-4 . (Knowledgeable and broad-based art-historical study, which is probably the most important overview presentation in German at the moment)

- Colum Hourihane (Ed.): Time in the medieval world: Occupations of the months and signs of the zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. Princeton University, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9768202-3-9 .

- James Carson Webster: The Laboratories of the Months in Antique and Mediaeval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century. (= Princeton Monographs in Art and Archeology. 21). Princeton 1938. (Repr. New York 1970. (Northwestern University Studies in the Humanities 4))

Individual examinations

- Gerhard Binder: The calendar of Filocalus: An illustrated edition of the Roman festival calendar from the 4th century AD. In: Wilhelm Geerlings (Hrsg.): The calendar: Aspects of a story. Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-73112-2 , pp. 61-95.

- Ursmar Engelmann: The monthly pictures of Santa Maria del Castello in Mesocco. Herder, Freiburg a. a. 1977, ISBN 3-451-17324-7 .

- The Très Riches Heures by Jean Duc de Berry in the Museé Condé in Chantilly. Einf. U. Come from Jean Longnon u. Raymond Cazelles . Special edition. Prestel, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-7913-0979-X , esp. Plates 2-13 and pp. 171ff.

- Festivals and customs from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: The Augsburg Monthly Pictures. Editor Christina Langner. Text contributions Heinrich Dormeier u. a. Chronicle, Gütersloh u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-577-14375-2 . (Elaborate and scientifically supervised illustrated book, which also deals with the monthly tradition of images in general; the images are excellent and the texts are based on the latest research)

- Ortrun Riha : 'Master Alexander's monthly rules'. Investigations into a late medieval regime duodecim mensium with critical text output. (= Würzburg medical historical research. 30). Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1985. (Medical dissertation Würzburg)

- Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: The Elisabethpsalter in Cividale del Friuli: Illumination for the Thuringian Landgrafenhof at the beginning of the 13th century. (= Monuments of German art ). Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-87157-184-9 , esp.p. 113ff. u. Fig. Pp. 87–91.

Books

- Dieter Matti : Monthly pictures - companion through the year. Desertina, Chur 2014, ISBN 978-3-85637-460-0 .

Web links

Most of the works and cycles mentioned in this article are clearly arranged on the Commons page.

- Monthly pictures of the Renaissance from Augsburg. ( Memento from February 6, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) an online exhibition of the German Historical Museum

- Medieval Rural Life in the Luttrell Psalter. ( Memento from January 3, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- The Zodiac and Labors of the Months Window , the stained glass window in Chartres with individual comments

- An Anglo-Saxon Calendar ( Memento of March 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Commentary on the entire program ( memento of April 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) of the large rose window of the Lausanne Cathedral (French)

- An extensive collection of monthly pictures on "flickr"

- Robert Reinick: The course of the year in children's life (all months in poems and illustrations; PDF file; 944 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ D. Pearsall, E. Salter: Landscapes and Seasons of the Medieval World. 1973, p. 144.

- ↑ Heribert M. Nobis: Time and Cosmos in the Middle Ages. In: Albert Zimmermann (Ed.): Mensura: Measure, number, number symbolism in the Middle Ages. Half volume 2. (= Miscellanea Mediaevalia. 16,2). Berlin et al. 1984, p. 274.

- ^ JC Webster: The Laboratories of the Months in Antique and Mediaeval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century. 1938, p. 94.

- ↑ G. Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni / monthly pictures: From antiquity to romanticism. 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Shane Adler: Months. 1998, p. 626.

- ^ BA Henisch: The Medieval Calendar Year. 1999, p. 184.

- ↑ For the signs of the zodiac see Hans Georg Gundel : Zodiakos. Zodiac images in antiquity: Cosmic references and ideas of the afterlife in everyday life in ancient times. (= Cultural history of the ancient world . 54). Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1324-1 .

- ↑ G. Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni / monthly pictures: From antiquity to romanticism. 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ G. Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni / monthly pictures: From antiquity to romanticism. 1999, p. 8f. u. 13.

- ↑ on this Ellen Beer : The rose of the cathedral of Lausanne and the cosmological circle of images of the Middle Ages. (= Bern writings on art. 6). Bern 1952.

- ↑ Joachim M. Plotzek: prayer book. 2nd illustration. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 4, Col. 1160f.

- ↑ Hans Ottomeyer et al. (Ed.): Birth of Time: A History of Images and Concepts. Exhibition at the Museum Fridericianum Kassel from December 12, 1999 - March 19, 2000. Wolfratshausen 1999, p. 229.

- ^ Ernst Zinner: Directory of the astronomical manuscripts of the German cultural area. Munich 1925.

- ↑ Norbert H. Ott, U. Bodemann, G. Fischer-Heetfeld (ed.): Catalog of the German-language illustrated manuscripts of the Middle Ages. Volume 1: 1. Ackermann from Bohemia - 11. Astrology / Astronomy. Munich 1991.

- ↑ the detailed examinations and evidence from Inge Herold: Pieter Bruegel: Die Jahreszeiten. Prestel, Munich et al. 2002.

- ^ W. Achilles: Monthly picture cycles in Hildesheimer splendid manuscripts of the 13th century. 2003, p. 13.

- ^ W. Achilles: Monthly picture cycles in Hildesheimer splendid manuscripts of the 13th century. 2003, p. 44.

- ^ W. Achilles: Monthly picture cycles in Hildesheimer splendid manuscripts of the 13th century. 2003, p. 21.

- ^ Teresa Pérez-Higuera: Medieval Calendars. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1998, p. 109.

- ^ W. Hansen: Calendar miniatures of the books of hours: Medieval life in the course of the year. 1984, p. 267.

- ↑ Dieter Harmening: Superstitio: Traditional and theoretical-historical studies of church-theological superstition literature of the Middle Ages. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1979, p. 125.

- ↑ dog. and cat. In: Lothar Dittrich, Sigrid Dittrich: Lexicon of animal symbols: Animals as symbols in painting in the 14th – 17th centuries. Century. (= Studies on international architecture and art history. 22). Petersberg 2004.

- ↑ z. BW Hansen: Calendar miniatures of the books of hours: Medieval life in the course of the year. 1984, p. 70, figs. 24-26.

- ^ Dieter Hägermann: Sheep. II. Economy. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 7, Col. 1433.

- ^ Margaret A. Sullivan: Peasantry. In: Helene E. Roberts (Ed.): Encyclopedia of comparative Iconography: Themes depicted in works of art. Volume 2, Chicago et al. 1998, pp. 709f.

- ^ Helmut Hundsbichler: Bauer, Bauerntum. C. Everyday rural life. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 1, Col. 1572ff.

- ^ BA Henisch: The Medieval Calendar Year. 1999, pp. 37, 136, 147f., 167ff. u. 200.

- ↑ D. Pearsall, E. Salter: Landscapes and Seasons of the Medieval World. 1973, p. 139 u. 145.

- ↑ G. Binder: The calendar of Filocalus: An illustrated edition of the Roman festival calendar from the 4th century AD 2002, pp. 84-95.

- ↑ G. Strohmaier-Wiederanders: Imagines anni / monthly pictures: From antiquity to romanticism. 1999, p. 29.

- ^ W. Achilles: Monthly picture cycles in Hildesheimer splendid manuscripts of the 13th century. 2003, p. 19ff.

- ^ Wolfgang Hirth: Regimina duodecim mensium in German-language text witnesses of the high and late Middle Ages. In: Medical History Journal. 17, 1982, pp. 239-255.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: In Jano claris. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 665.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: The Grazer early Middle High German monthly rules and their source. In: Gundolf Keil u. a. (Ed.): Specialist literature of the Middle Ages. Festschr. for G. Eis. Stuttgart 1968, p. 139ff.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: In Jano claris. In: Author's Lexicon . 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Sp 373ff.

- ↑ Ortrun Riha : The dietary regulations of the medieval monthly rules. In: Josef Domes et al. (Hrsg.): Light of nature: Medicine in specialist literature and poetry. (= Göppingen work on German studies. No. 585). Festschr. for G. Keil. Göppingen 1994, p. 341.

- ↑ Rossell Hope Robbins (ed.): Secular Lyrics of the XIVth and XVth Centuries . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1955, p. 62.

- ↑ Deviating from this, Ewa Sniezynska-Stolot: The Ptolemaic worldview and medieval iconography. In: Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte. Volume XLVI / XLVII, Part 2, 1993/94, pp. 700ff. (Monthly work as a representation of the constellations that accompany the signs of the zodiac, so-called Paranatellons )

- ^ Marion Grams-Thieme: Presentation of the year, seasons. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 5, Col. 277-279.

- ^ W. Hansen: Calendar miniatures of the books of hours: Medieval life in the course of the year. 1984, pp. 40f.