Economy of india

| India | |

|---|---|

|

|

| World economic rank | 7th (nominal) (2016) 3rd ( purchasing power parity , PPP) (2016) |

| currency | Indian rupee (INR, ₹) |

| Trade organizations |

WTO , G-20 |

| Key figures | |

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

US $ 2,256 billion (nominal) (2016) US $ 8,662 billion (PPP) (2016) |

| GDP per capita | 1,723 US $ (nominal) (2016) 6,616 US $ (PPP) (2016) |

| GDP by economic sector |

Agriculture : 17.3% Industry : 29.0% (of which construction : 7.7%, manufacturing industry 16.6%) Services : 53.7% (2016-17) |

| growth |

6.6% (2016/17, estimate) 7.6% (2015/16) 7.2% (2014/15) |

| inflation rate | 5.1% (2016/17, estimate) |

| Foreign trade | |

| export | US $ 276.5 billion (2016) |

| Export goods | in the period 2016/17: technical goods 24% gems / jewels 16% crude oil products 11% confection Textiles 6% |

| Export partner | In billion US $:

|

| import | 382.7 billion US $ (2016) |

| Import goods | in the period 2016/17: petroleum / petroleum products 23% electron. Devices 11% Machines 8% Gold 7% |

| Import partner | In billion US $:

|

| Foreign trade balance | - US $ 106.2 billion (2016) |

| public finances | |

| Public debt | 69.7% of GDP (2016, estimate) |

| Budget balance | −3.8% of GDP (2016/17, estimate) |

The Indian economy is in relation to the nominal gross national income of about 2.049 billion US dollars in 2014 to ninth in the world. In terms of gross domestic product (GDP) purchasing power parity (PPP), according to calculations by the International Monetary Fund , India was third in the world in 2016 , after the United States and the People's Republic of China . India is a managed economy . The extensive state regulations of the domestic economy and the comprehensive protection of the economy from foreign competition have been gradually reduced, especially since the early 1990s. Economic growth accelerated to 6.4% on average between 1995 and 2005. In the decade between 2005 and 2015, the growth rate was even higher. In 2017, India was the fourth fastest growing economy in the world at 7.2%. Only the comparatively small economies of Ethiopia , Uzbekistan and Nepal were ahead of India .

In the Global Competitiveness Index , which measures a country's competitiveness, India ranks 40th out of 137 countries (as of 2017-2018). In 2017, the country was ranked 143rd out of 180 countries in the index for economic freedom .

historical development

British colonial times

In the pre-colonial period, a highly developed handicraft shaped the economy of the cities. There was a well-developed trade network ( India trade ), which enabled the export of high-quality goods (e.g. spices, fabrics) to East Asia, East Africa, Europe and the Middle East. However, the vast majority of the population made their living in agriculture .

The English gained a foothold in the coastal areas of northern India in the 17th century. For the British East India Company , which had extensive trading privileges, the cloth trade proved to be particularly profitable. In weaving mills, especially in Bengal , she had textiles made for export to England . In the early 18th century, the company controlled almost all of its motherland's exchange of goods with India. From 1765 on , the practically powerless mogul Shah Alam II granted her the right to levy taxes in the province of Bengal. With the Industrial Revolution in England towards the end of the 18th century, industrially manufactured British textiles replaced handicraft production in India. The consequences were mass unemployment and the impoverishment of the Indian weavers' boxes. In the 19th century, more and more industrial goods poured into the Indian market, displacing artisanal local goods. The craft was soon limited to low-value products that did not justify the high transport costs from Great Britain to India, as well as a few local luxury goods such as jewelry and silk .

In view of the enormous sales opportunities for their own products, the British showed no interest in the industrialization of India. Indigenous industry has been slow to develop in India. It all began in Bombay , the center of the cotton trade. The first spinning mill was founded there in 1854. The young cotton industry was exposed to enormous competitive pressure from British mass-produced goods, so that it was only able to survive by producing coarse cloth for the poorer population at prices that British suppliers could not undercut because of the long transport route. In the late 19th century, industrial cloth production expanded into the hinterland of Bombay and what is now Gujarat . By the First World War , India's cotton industry had grown to be the fourth largest in the world. However, it was only able to completely oust the British competition after the war.

At about the same time as the cotton industry, the jute industry developed in Bengal . A Briton set up the first jute spinning mill in Calcutta in 1855 . From the 1880s the industry experienced an upswing. After the First World War, exports of industrially processed jute exceeded those of raw jute for the first time. However, the division of British India into India and Pakistan gave the jute industry a setback, as the main cultivation areas were in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh ), while processing was almost exclusively limited to the Greater Calcutta area in the Indian part of Bengal.

In addition to the textile industry, which employed more than half of all industrial workers, only steel production became more important even before independence. In 1907 Jamshedji Tata founded the first and until the 1950s the only Indian steelworks in Sakchi , later renamed Jamshedpur in his honor , which produced rails for railway construction. As in the case of the textile industry, the First World War led to the interruption of British imports of goods and thus gave the steel mill a boost. After the war, it gained a dominant position on the Indian steel market.

When the British gave India independence in 1947, the country was a barely industrialized agrarian state . The traditional handicraft had not been able to withstand the superior British industry. Only in a few metropolises had an industry worth mentioning developed. Agriculture had only been a source of taxation for the British and remained underdeveloped, inefficient and overstaffed. On the other hand, the colonial rulers created a fairly well-developed railway network and modern administrative structures.

Socialist orientation 1947 to 1991

Promotion of heavy industry

After independence in 1947 , Jawaharlal Nehru and Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis built a socialist planned economy with market economy elements. The concept for this had already been worked out together with the industrialists Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata and Kumar Birla before independence and was laid down in the Bombay Plan in 1944 . With the aim of overcoming widespread poverty, the state should create the basis for steady growth. The domestic industry should be protected against foreign competition and heavy industry should be particularly encouraged. The creation of jobs was not only intended in large-scale industry, but mainly in small businesses, which were therefore given special support. Since 1951, the economic goals have been set in five-year plans under the supervision of a planning committee. The main focus of Nehru's economic policy was directed towards the expansion of industry. To this end, the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 divided all economic sectors into three categories. The first category ( Schedule A ) included 17 key industries that were to be reserved exclusively for the state. These are:

- Armor (weapons and ammunition)

- Nuclear energy

- Iron and steel

- Heavy cast and forged parts made of iron and steel

- Heavy industrial plants and machines for the iron and steel, mining , machine tool construction and other key industries

- Heavy electricity systems including large water and steam turbines

- Hard coal and lignite mining

- Mineral oil extraction

- Iron ore , manganese ore , chrome ore , gypsum , sulfur , gold and diamond mining

- Extraction and processing of copper , lead , zinc , tin , molybdenum and tungsten

- Minerals used in the production and use of nuclear energy

- Aviation industry

- air traffic

- Rail transport

- shipbuilding

- Telephones and telephone cables, telegraphy and radio technology (with the exception of radio receivers )

- Power generation and distribution

Private companies were not allowed to set up new businesses in these areas, but existing private businesses remained.

In the industries of the second category ( Schedule B ) - including pharmaceutical and parts of the chemical industry , all industries that processed metals except those of category A (e.g. aluminum ), as well as road and sea transport - both the state and private companies were allowed to participate actuate. The main role was initially intended for the private sector, but in the long term the state should take control.

The third group ( Schedule C ) comprised all branches of the economy that should be open to the private sector. In addition to agriculture and handicrafts, this included the processing industry ( motor vehicles , etc.) and the consumer goods industry ( textile , food and luxury goods industries , etc.). Here too, however, the state reserved the right to economic activity.

India thus became a “mixed economy ” in which central administrative elements based on the model of the Soviet Union exist alongside market-economy features.

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Period | 1951-1956 | 1956-1961 | 1961-1966 | 1969-1974 | 1974-1979 | 1980-1985 | 1985-1990 | 1992-1997 | 1997-2002 | 2002-2007 | 2007–2012 | 2012-2017 |

| Economic growth 1951 to 1990 according to plan periods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning period | Average annual growth rate | ||

| gross domestic product | Primary sector 1 | Industry | |

| 1951-1956 | 3.6% | 2.9% | 6.1% |

| 1956-1961 | 4.3% | 3.4% | 6.5% |

| 1961-1966 | 2.8% | −0.1% | 6.9% |

| 1966-1969 | 3.9% | 4.4% | 3.6% |

| 1969-1974 | 3.4% | 2.7% | 3.9% |

| 1974-1979 | 4.9% | 3.6% | 6.4% |

| 1979-1980 | −5.2% | −12.3% | −3.3% |

| 1980-1985 | 5.7% | 5.8% | 6.1% |

| 1985-1990 | 5.6% | 3.6% | 6.5% |

| 1951-1990 | 4.0% | 2.8% | 5.6% |

| 1990-1992 | 3.4% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 1992-1997 | 6.3% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 1997-2002 | 5.6% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 2002-2007 | 8.7% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 2007–2012 | 7.1% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 1991-2012 | 6.6% | k. A. | k. A. |

| 1 includes agriculture, forestry, livestock, fishing, mining | |||

|

Source for the years 1950–90: Bronger (1996), p. 183, for the years since 1990: Indian Planning Commission |

|||

Another characteristic of the economic system in independent India before 1991 was the extensive licensing provisions that were created as an instrument of state influence on the private sector. Private companies were only allowed to set up or expand new businesses after a state license had been granted, often in connection with extensive requirements. In addition, the government reserved various control mechanisms, such as price controls. In the event of violation of the applicable provisions, private companies could be nationalized. The politician C. Rajagopalachari coined the nickname License Raj ("license rule") in reference to the British colonial rule ( British Raj ) for the strongly regulatory license system .

In order to promote the development of the domestic industry, the access of foreign products and investors to the Indian domestic market was made more difficult. There are protective tariffs introduced and even imposed import bans. With this strategy ( import substitution ) foreign products should be replaced by goods from own production. They wanted to save foreign currency and create jobs for their own people. In 1973 a provision came into force according to which foreign investors were only allowed to operate in joint ventures with Indian majority stakes.

As early as the early 1960s, the system was criticized as not being open and market economy enough. The main problem was the lack of technical progress and the lack of foreign capital. Nevertheless, the industrialization of India advanced. In the 1950s, for example, three large steelworks were put into operation in Durgapur , Bhilai and Rourkela .

"Green Revolution"

The first major economic crisis occurred in the mid-1960s. Until then, agriculture had been neglected by the state, although it still employed more than two thirds of the population. Although the Indian government implemented land reforms after independence by limiting land ownership, the regulations could easily be circumvented. In essence, an almost feudal system remained in the country , with many small farmers who practiced little more than subsistence farming and a few powerful landowners. These conditions have persisted to this day, especially in the east of the country. In addition, the lack of machinery and capital hindered agricultural development. Two years of drought in a row, 1965 and 1966, led to considerable crop failures, and the resulting price increases ultimately led to a crisis.

The crisis, which caused grain imports to rise to over 10 million tons annually, prompted the Indian government to radically revise its agricultural policy. The increases in yields achieved in the 1950s were mainly due to an expansion of the area under cultivation, but not to fundamental structural changes in agriculture. From the mid-1960s onwards, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was aiming for rapid, sustainable increases in income with a huge modernization program - known as the “ Green Revolution ”. The main measures included the introduction of resilient high- yielding varieties, the massive use of pesticides , mineral fertilizers and agricultural machinery, and the expansion of irrigation areas through the construction of dams, canals and wells.

In fact, the “Green Revolution” was extremely successful in terms of its objective, namely the significant increase in agricultural production, especially in wheat production . The social effects are assessed very differently, however. The increased income from agriculture largely benefits large landowners, while smallholders have so far had little share of it.

New methods were mainly used in regions that promised quick success. Since high-yielding varieties of wheat are easier to grow and far less demanding than corresponding rice varieties , the focus was on the wheat-growing areas in northwest India, such as Punjab and Haryana , which developed into the “breadbasket” of India. But this also exacerbated the regional disparities in productivity. It was only later that there was success with rice.

With the shift of the state investment focus to agriculture, industrial growth slowed between 1966 and 1974 to less than 4% on an annual average compared to more than 6% in the two preceding decades. With the exception of the recession year 1979/80, it returned to its old values from the mid-1970s.

First attempts at liberalization and the economic crisis from 1989 to 1991

At the same time, economic policy remained strongly oriented towards the domestic market. With isolation from the world market, India's share of world trade, which in 1950 was 2.4%, fell to less than 0.5%.

Timid liberalization approaches in foreign trade under Rajiv Gandhi from the mid-1980s onwards showed little success. Instead, over-regulation and corruption curbed India's economic development.

Rising government spending on defense and subsidies as well as falling tax revenues led to an economic and financial crisis between 1989 and 1991. The crisis manifested itself in high inflation rates, rising national debt , the withdrawal of capital , especially from Indians living abroad, and a shortage of foreign exchange stocks . India's international credit rating fell significantly. In addition, the temporarily high oil price as a result of the Second Gulf War in 1990/91 had a devastating impact on India's foreign trade balance, which has to meet most of its oil requirements through imports.

Liberalization since 1991

After the fall of the Chandra Shekhar government in 1991 due to the rejection of the budget by parliament, a radical rethink in economic policy began. The crisis and slow economic growth in India, which earned it the nickname “elephant” in allusion to the much more dynamic and successful East Asian “ tiger states ”, were attributed to fundamental structural grievances.

With the eighth five-year plan for the years 1992 to 1997, the government under PV Narasimha Rao ( Congress Party ), with Manmohan Singh as finance minister, focused on liberalizing the economy. In contrast to many African and Latin American countries, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) did not have any significant influence on the decision to liberalize, although India used World Bank loans to reduce its national debt, which had risen sharply in the 1980s. In contrast, outstanding Indian economists such as Jagdish Bhagwati and TN Srinivasan, as advisors to the Rao government, played a decisive role in the implementation of the project.

The new economic policy had three main objectives:

Initially, the focus was on coping with the precarious financial situation due to the previous economic crisis. To this end, massive cuts in government spending, primarily through the cancellation of subsidies , were decided.

The second objective should be to liberalize foreign trade in order to increase the small volume of imports and exports. The devaluation of the rupee by 20 percent served as a short-term measure to promote exports . It was hoped that the dismantling of the extensive import restrictions (import quotas) and customs tariffs would lead to a lasting revival of trade relations with foreign countries.

The third main objective was the deregulation of the internal market. Private entrepreneurs were given access to many sectors of the economy that were previously exclusively reserved for the state, such as banking. The enormous number of permits and licenses required to set up and run a private company has been greatly reduced. Regulations that inhibited foreign direct investment ceased to apply. The decisive factor was the abolition of the statutory Indian majority stake in foreign investments, which was introduced in the 1970s and the like. a. provoked the withdrawal of Coca-Cola from the Indian market.

In contrast to the reform programs imposed by other countries by the IMF , privatizations played a subordinate role. The agriculture was initially exempt from the changes, but was later liberalized in some states, including Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh.

The BJP government of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee continued the liberalization efforts started by Congress between 1998 and 2004. In addition, there were labor market reforms and a comprehensive infrastructure program.

Overview of India's economic growth from 1951 to 2014

The following graph shows India's economic growth from 1951 to 2014 according to information from the Central Planning Commission.

Economic growth in the states from 1998 to 2014

| State / UT | 1997- 1998 |

1998- 1999 |

2001- 2002 |

2002- 2003 |

2003- 2004 |

2004- 2005 |

2005- 2006 |

2006- 2007 |

2007- 2008 |

2008- 2009 |

2009- 2010 |

2010- 2011 |

2011- 2012 |

2012- 2013 |

transit cut |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | −1.37 | 12.16 | 4.22 | 2.73 | 9.35 | 8.15 | 9.57 | 11.18 | 12.02 | 6.88 | 4.53 | 11.64 | 7.51 | 5.09 | 7.40 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 3.12 | 3.13 | 15.70 | −4.31 | 10.94 | 16.46 | 2.75 | 5.25 | 12.06 | 8.73 | 9.23 | 3.78 | 4.49 | 4.65 | 6.86 |

| Assam | 0.99 | −0.22 | 2.60 | 7.07 | 6.02 | 3.74 | 3.40 | 4.65 | 4.82 | 5.72 | 9.00 | 7.26 | 5.33 | 6.06 | 4.75 |

| Bihar | −3.85 | 7.59 | −4.73 | 11.82 | −5.15 | 12.17 | −1.69 | 16.18 | 5.55 | 14.54 | 5.35 | 15.03 | 10.29 | 10.73 | 6.70 |

| Chhattisgarh | 3.11 | 5.34 | 6.79 | 2.54 | 8.03 | 5.49 | 3.23 | 18.60 | 8.61 | 8.39 | 3.42 | 10.6 | 6.98 | 5.42 | 6.90 |

| Goa | 2.82 | 22.61 | 4.50 | 7.08 | 7.49 | 10.19 | 7.54 | 10.02 | 5.54 | 10.02 | 10.20 | 16.89 | 20.21 | 4.10 | 9.94 |

| Gujarat | 2.11 | 7.18 | 8.41 | 8.14 | 14.77 | 8.88 | 14.95 | 8.39 | 11.00 | 6.78 | 11.25 | 10.01 | 7.66 | 7.96 | 9.11 |

| Haryana | 1.43 | 5.56 | 7.81 | 6.52 | 9.86 | 8.64 | 9.20 | 11.22 | 8.45 | 8.17 | 11.72 | 7.41 | 8.03 | 5.55 | 7.83 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 6.38 | 7.21 | 5.21 | 5.06 | 8.08 | 7.56 | 8.43 | 9.09 | 8.55 | 7.42 | 8.09 | 8.79 | 7.31 | 6.14 | 7.38 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 5.66 | 5.19 | 1.96 | 5.13 | 5.17 | 5.23 | 5.78 | 5.95 | 6.40 | 6.46 | 4.50 | 5.65 | 7.95 | 4.49 | 5.39 |

| Jharkhand | 26.3 | 5.71 | 2.80 | 4.55 | 3.46 | 15.21 | −3.20 | 2.38 | 20.52 | −1.75 | 10.14 | 15.86 | 4.49 | 7.43 | 8.14 |

| Karnataka | 6.91 | 12.72 | 5.17 | 7.30 | 6.25 | 9.85 | 10.51 | 9.98 | 12.6 | 7.11 | 1.30 | 10.15 | 3.69 | 5.47 | 7.79 |

| Kerala | 2.89 | 7.06 | 7.12 | −3.91 | 11.42 | 9.97 | 10.09 | 7.90 | 8.77 | 5.56 | 9.17 | 6.92 | 7.96 | 8.24 | 7.08 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 5.00 | 6.56 | 13.2 | −0.06 | 16.55 | 3.08 | 5.31 | 9.23 | 4.69 | 12.47 | 9.56 | 6.31 | 9.69 | 9.89 | 7.96 |

| Maharashtra | 5.56 | 3.36 | 4.05 | 6.81 | 8.00 | 8.71 | 13.35 | 13.53 | 11.26 | 2.58 | 9.30 | 11.26 | 4.82 | 6.18 | 7.77 |

| Manipur | 8.77 | 2.16 | 6.81 | −0.46 | 10.84 | 9.7 | 6.35 | 2.00 | 5.94 | 6.48 | 6.99 | −0.58 | 9.79 | 3.95 | 5.62 |

| Meghalaya | 6.13 | 9.87 | 6.89 | 3.79 | 6.78 | 7.11 | 7.91 | 7.74 | 4.51 | 12.94 | 6.55 | 8.57 | 12.58 | 2.18 | 7.40 |

| Mizoram | k. A. | KA | 6.52 | 10.39 | 3.19 | 4.15 | 6.97 | 4.78 | 10.98 | 13.34 | 12.38 | 17.18 | −2.55 | 7.23 | 7.88 |

| Nagaland | 7.82 | −4.01 | 11.45 | 9.45 | 5.02 | 6.65 | 10.22 | 7.80 | 7.31 | 6.34 | 6.90 | 9.35 | 8.32 | 6.45 | 6.80 |

| Orissa | 13.14 | 2.45 | 6.29 | −0.65 | 15.15 | 12.61 | 5.68 | 12.85 | 10.94 | 7.75 | 4.55 | 8.01 | 3.78 | 8.09 | 7.90 |

| Punjab | 3.00 | 5.59 | 1.92 | 2.85 | 6.07 | 4.95 | 5.90 | 10.18 | 9.05 | 5.85 | 6.29 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 4.63 | 5.67 |

| Rajasthan | 11.32 | 4.02 | 10.87 | −9.90 | 28.67 | −1.85 | 6.68 | 11.67 | 5.14 | 9.09 | 6.70 | 14.41 | 5.17 | 4.52 | 7.61 |

| Sikkim | 7.14 | 7.06 | 7.88 | 7.31 | 7.89 | 7.72 | 9.78 | 6.02 | 7.61 | 16.39 | 73.61 | 8.70 | 10.77 | 7.62 | 13.25 |

| Tamil Nadu | 8.20 | 4.73 | −1.56 | 1.75 | 5.99 | 11.45 | 13.96 | 15.21 | 6.13 | 5.45 | 10.83 | 13.12 | 7.39 | 3.39 | 7.57 |

| Tripura | 10.27 | 9.91 | 14.07 | 6.41 | 5.88 | 8.14 | 5.82 | 8.28 | 7.70 | 9.44 | 10.65 | 8.12 | 8.69 | 8.70 | 8.72 |

| Uttar Pradesh | −0.09 | 2.75 | 2.17 | 3.72 | 5.27 | 5.40 | 6.51 | 8.07 | 7.32 | 6.99 | 6.58 | 7.86 | 5.57 | 5.92 | 5.29 |

| Uttarakhand | 1.80 | 1.66 | 5.53 | 9.92 | 7.61 | 12.99 | 14.34 | 13.59 | 18.12 | 12.65 | 18.13 | 10.02 | 9.36 | 5.61 | 10.10 |

| West Bengal | 8.25 | 6.36 | 7.32 | 3.78 | 6.20 | 6.89 | 6.29 | 7.79 | 7.76 | 4.90 | 8.03 | 5.78 | 4.72 | 6.72 | 6.49 |

| India as a whole | 4.30 | 6.70 | 5.81 | 3.84 | 8.52 | 7.47 | 9.48 | 9.57 | 9.32 | 6.72 | 8.59 | 8.91 | 6.69 | 4.47 | 6.39 |

Recent development of the Indian economy

Economic Policy of the Singh Government 2004 to 2014

Manmohan Singh was Prime Minister from 2004 to 2014 . As finance minister in the Rao cabinet, he was the main initiator of Indian economic reforms. Singh was a symbol of loyalty and honesty against the background of widespread corruption. During the first government of Manmohan Singh 2004–2009, India achieved an average economic growth of 7 to 8% annually. In the 2009 general election , the government alliance gained votes and Singh formed a second government . In the course of the legislative period, however, the government lost its majority and was then dependent on the support of communists and left-wing socialists. The complicated majority structure made reforms difficult.

Further external liberalization

The government underscored its will to continue the foreign trade liberalization policy by largely liberalizing the conditions for foreign investments in the areas of civil aviation, electricity supply and telecommunications.

Privatization program stopped

According to many observers, efforts to privatize the huge state-owned companies as well as banks and insurance companies slackened considerably during the legislative period. The privatization process stalled under the influence of the communist parties, which had been strengthened by the results of the regional elections in May 2006.

Budget deficit falling only slowly

In the 2004 budget, the government committed itself to greater spending discipline and a reduction in the budget deficit. Successes are slow to show. According to the IMF, the deficit of the central government and the federal states was over 8 percent of the gross domestic product in the 2008 fiscal year .

| Central government and state budget deficits as a percentage of gross domestic product |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal year | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012–13 | 2013-14 |

| Deficit (%) | - 7.2 | - 6.5 | - 5.1 | - 4.0 | - 8.3 | - 9.3 | - 6.9 | - 7.8 | - 6.9 | - 6.7 |

| Source: Reserve Bank of India | ||||||||||

The high budget deficit and the resulting burden of interest payments limited the government's ability to sustainably fight poverty by investing in infrastructure, health and education. A first step in increasing the financial scope for these purposes was the introduction of VAT in April 2005.

Recent macroeconomic situation and development

Production structure: the service sector as a growth engine

For a long time , the engine of growth in India - unlike in China - was not industry but the service economy . Because of this, China is being referred to as the world's future workbench while India will take intellectual leadership.

In fiscal 2005 and 2006, however, industry grew almost as fast as the service sector. According to the country information from the German Foreign Ministry, its contribution to the gross domestic product in 2006 was around 26 percent, but only half as high as the contribution of the service sector, which was around 55 percent. The share of agriculture fell further in 2010 to 17.22 percent.

In terms of the employment structure, India is still an agricultural country. Around 60 percent of the workforce make a living from agriculture. Their income development is still very much dependent on the favorable weather conditions in the monsoon season .

Although industry has developed significantly less dynamically than the service sector for a long time, despite all the obstacles caused by an overflowing state bureaucracy, an efficient middle class of private entrepreneurs has also formed here. In a global comparison, some large private companies are ranked among the top group in their industries (for example the IT companies Infosys , Satyam Computer Services , HCL , Tata and Wipro ; Reliance Industries ; Tata Motors , commercial vehicles; Hero Honda Motors , motorcycles; Hero Cycles , bicycles ). In this respect, India differs significantly from China, where state-controlled companies have a much stronger position than in India.

Strong economic growth

The transition from a socialist-oriented economic policy with extensive state control and regulation to a more liberal economic policy accelerated economic growth . The average growth in India from 1995 to 2006 was around 7 percent.

According to the OECD, growth in gross domestic product accelerated to 9.4 percent overall in the 2006 fiscal year . Production growth in the liberalized telecommunications and air traffic sectors was above average.

In 2006 the value of the gross domestic product at current exchange rates reached almost 880 billion US dollars. India only contributed around 1.5 percent to global production. Adjusted for purchasing power, it was around 6 percent.

Low per capita income and high unemployment

With a population of around 1.1 billion, the per capita income in 2006 was only around 800 US dollars. If you take into account the higher purchasing power of a US dollar in India, it is around four times as high when adjusted for purchasing power.

In the World Bank classification, India still belongs to the group of developing countries with low incomes.

The average income has risen, but for the poorest sections of the population in rural areas, the increase in production has in many cases not yet brought a significant improvement in the standard of living . Around 80 percent of Indians have less than 2 US dollars a day, around a third have less than one US dollar a day. So far, the growing middle class, which is estimated at 100 to 300 million depending on the definition, and the upper class have benefited from the economic upturn. In the opinion of many observers, the fruits of the upswing have so far mainly been reserved for the well-educated urban elite. The roughly 600 million rural residents largely left empty-handed. It should be recognized, however, that economic growth in India is being driven much more strongly than investment-driven growth in China by the increase in private consumption, which results from overall rising incomes.

If the government wants to prevent a further divergence in the incomes of the social classes, it must above all ensure a sufficient number of jobs - also outside the software laboratories - and improve the education system.

Despite the significantly accelerated growth in recent years, the official unemployment rate is still 9 percent, with a significant number of unemployed who are not recorded by the statistics.

Accelerated price increase

The price increase rose, as measured by the consumer price developments for industrial workers, from 3.8 percent in fiscal 2004 to 5.3 percent in the year of 2006.

| Price increase Increase in the consumer price index for industrial workers compared to the previous year in percent |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal year | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| Price increase | 3.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.5 |

Source: OECD: Economic Outlook December 2007

Slow foreign trade opening, still of little global economic importance

After joining the World Trade Organization in 1995, India increasingly liberalized its foreign trade and opened it up to foreign competitors. This means that Indian companies are exposed to increasing competitive pressure, which benefits their performance. The Indian import tariffs are still among the highest in the world today. They make wholesale products more expensive and thus reduce the competitiveness of Indian exports. And Indian retail is still closed to foreign investors.

India is - at least in comparison with the western industrialized countries and China - not yet very closely integrated into the world economy . The so-called “ degree of openness ” of the Indian economy - the proportion of the sum of its imports and exports of goods and services in the gross domestic product - has increased significantly, but was only 38 percent in 2004 (China: 65 percent).

In trade in goods, the volume of foreign trade more than quadrupled between 1991 and 2004. Nevertheless, India's share of world trade only reached around one percent (share of global goods exports: 0.8 percent; share of global goods imports: 1.1 percent); in contrast, China already has a share of around 6.5 percent.

India also plays a subordinate role in global trade in services. Its share in service exports and imports in 2004 only reached 1.7 percent. The value of production in the Indian service sector is also still low by international standards. In 2003, at just under 300 billion US dollars, it was around a quarter lower than the value of service production in the Netherlands.

In the service sector, in the course of the globalization of the world economy , India is increasingly taking on the tasks of a " back office " for foreign companies that outsource administrative work to India. With its large number of young, well-educated workers, India offers good conditions for this, although it should not be overlooked that around a third of the population cannot read or write. When it comes to IT services, India has even become the world's second largest exporter after Ireland . Not only in the IT sector, but also in other industries, the Indian workforce is considered to be very promising. This includes the financial sector and legal services, as well as the areas of medicine (e.g. in the form of telemedicine ) and pharmacy . Every year around 250,000 young engineers enter the labor market, of which, however, according to some observers, only a quarter can meet the expectations of western companies.

India is running a deficit on its current account , which includes trade in goods and services. In fiscal 2006 it was 1.1 percent of GDP.

| Current account balance as a percentage of gross domestic product |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal year | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| - 0.1 | - 1.1 | - 1.1 | - 2.0 | - 2.1 | - 2.0 | |

Source: OECD: Economic Outlook December 2007

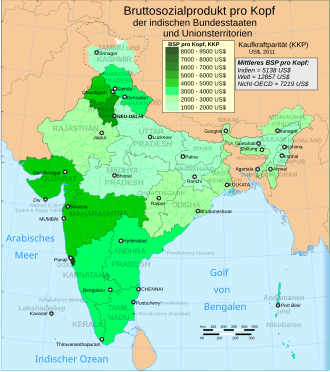

In a long-term comparison, foreign direct investment has multiplied. They rose from just $ 68 million in 1990/91 to around $ 10 billion in 2006/2005. In relation to the Indian gross domestic product, however, this only corresponds to around 1 percent. In China this value was around four times as high, in Brazil and Russia around three times. In addition, foreign direct investment is concentrated in a few of the 28 federal states (particularly Maharashtra , Tamil Nadu , Karnataka , Gujarat , Andhra Pradesh ) and the capital city of Delhi .

There has also been tremendous growth in portfolio investment by foreign companies, which was banned until 1991 and stood at $ 8.9 billion in 2004/05.

Improved international credit

The creditworthiness of India is increasingly rated better by the leading agencies for assessing credit risks against the background of the favorable macroeconomic development. Following the rating agency Moody’s , at the beginning of August 2006 the Fitch agency also raised its credit rating for the Indian state to the lowest so-called “investment grade” . In March 2007, India was ranked 58th out of 174 listed countries behind Bulgaria and ahead of Croatia in the country rating of Institutional Investor .

Long term prospects for the Indian economy

According to a study by the World Bank (“Doing Business”) , the growth and investments of the Indian economy are hindered in particular by the inadequate infrastructure , interventions and requirements of the state bureaucracy and widespread corruption . In addition, there are labor market regulations, which in some areas of the economy, for example, make it very difficult to lay off workers.

Despite these obstacles, the medium and long-term growth prospects of India are assessed as very favorable in view of the growing population with a great need for consumer and capital goods, if the course of economic liberalization is continued. The following are important prerequisites for sustained strong economic growth:

- A high proportion of the Indian population is of working age,

- there is a relatively large number of qualified workers,

- India’s ties to the world economy are becoming ever closer.

India in particular has a favorable age structure of its population - also in comparison with China . The current high proportion of young people in the population will ensure a high proportion of people of working age in the coming decades. The "aging" of the population that is to be expected in Europe and also in China will begin much later in India.

A large supply of qualified workers is already available today. The information on the number of Indian university graduates and the assessment of their qualifications, however, differ greatly from one another. According to management consultancy McKinsey , India has a total of 14 million young university graduates in all disciplines with up to seven years of professional experience. According to the long-time Spiegel editor Olaf Ihlau, India trains 500,000 IT specialists, technicians and engineers every year, Germany just 40,000. The number of Indian students is around nine million. At the same time, however, around a third of the population over the age of 15 cannot read or write. A large proportion of the children still receive at best basic education in poorly equipped state schools. Almost half of the students leave after six classes.

India is increasingly integrating itself into the world economy and taking advantage of the international division of labor. The business language English makes this easier. Due to the low wage level, it will have advantages over foreign competitors in terms of labor costs for a long time to come . High currency reserves and - measured in terms of gross domestic product - relatively low foreign debt make India less vulnerable to global economic crises.

In comparison with its major competitor, the People's Republic of China , India has other important advantages in the growth race, above all the openness and adaptability of a democracy with a largely privately organized market economy:

- In contrast to the state-controlled Chinese economy, the Indian upswing is driven by private companies. Handelsblatt correspondent Oliver Müller sees this as a guarantee for better management of the capital employed: “The mistrust of Beijing's cadres about entrepreneurial commitment beyond their control encourages waste and bad investments. Indians are immediately punished by competition for this, their economy is more careful with capital. ”Another factor contributing to this is that India has a functioning financial market with solid banks; the proportion of so-called bad loans is low in contrast to China.

- The “know-how” of foreign companies is much more respected in India than in China, where foreign investors must fear that new technologies will be quickly copied.

- The Indian legal system is based on the British system and is more familiar to European and American investors than the Chinese legal system.

- Many experts are also of the opinion that Indian democracy promotes India's economic boom. With freedom of expression, separation of powers and a functioning legal system, India, for example, also according to Olaf Ihlau, offers more stability and fewer risks than the one-party dictatorship China, which could get into dangerous turmoil if political opening is due. According to these observers, the fact that India has remarkable social and political stability - despite an unequal distribution of income, high unemployment and many ethnic and religious differences - is due to the integrative power of Indian democracy. One price for Indian democracy, however, is the length of the political decision-making process. Far-reaching decisions and investment decisions require more time in an open society like India, in which different interests have to be taken into account, than in a one-party dictatorship.

Whether India or China will grow faster by 2020 is controversial.

A study by Deutsche Bank presented in May 2005 came to the conclusion that India will achieve the strongest growth of the 34 countries examined by the year 2020 with an annual 5.5 percent. As a justification, the bank refers in particular to the favorable age structure of the growing population. According to United Nations forecasts, the Indian population is likely to rise to around 1.4 to 1.5 billion people by 2030. India will then replace China as the most populous country on earth. While China's population is likely to decline after 2030, India's population will continue to rise to around 1.6 billion by 2050.

In contrast , projections published by the World Bank in 2006 assume that in the period from 2005 to 2020 the annual growth of the Chinese economy at 6.6 percent will be stronger than that of the Indian economy with 5.5 percent.

A long-term study by the US investment bank Goldman Sachs predicts that the gross domestic product of the Indian economy, adjusted for purchasing power, is likely to grow by 8.5 percent annually through 2050. India will overtake Japan - measured by purchasing power-adjusted gross domestic product - and move up from today's fourth to third place after the USA and China.

Even then, the average standard of living in India will still be relatively low. According to Goldman Sachs, the gross domestic product per inhabitant is likely to be only about half as high as in China. Per capita incomes in the G7 industrialized countries and in Russia will be around three to five times higher than in India.

Special developments in the Indian economy

Labor market for highly qualified workers, especially in the IT sector

The competition between local companies and international corporations for talent could lead to a shortage of engineers. McKinsey estimates that there could soon be a shortage of 500,000 engineers. The demand from Indian companies and foreign offshoring companies is gigantic: Indian IT companies such as TCS , Wipro and Infosys hire around 1000 engineers per month. In the past, companies like SAP , Oracle and Microsoft were able to grow faster than in other parts of the world, mainly because of the large availability of software specialists. IBM hired 15,000 new employees in India in 2005.

Indian and foreign IT companies are increasingly avoiding the tough competition for talent in the metropolises and expanding in smaller cities such as Chandigarh , Bhubaneswar and Ahmedabad .

The talent pools are rated as promising not only in the IT sector, but also in other industries. These include finance and lawyers, telemedicine and pharmaceutical research.

250,000 new engineers enter the labor market every year. But only a quarter of them live up to the expectations of western companies - compared to 15 percent among the remaining 2.2 million academics.

Wages in India are still very low but are growing rapidly. In 2005 wage increases exceeded all other countries. According to an estimate by the Hewitt personnel consultancy, they will rise by 14 percent in 2006.

retail trade

India is the country with the highest density of shops in the world. The retail trade is characterized by small dealers who hold 98 percent of the market. Only four percent of the stores are larger than 46 square meters. Most Indians shop in small family-run shops and markets rather than supermarkets. The small businesses are the most important employer in India after agriculture. As a result, the government is reluctant to liberalize the retail sector because it fears that multinational corporations could take over the sector. Indian retail chains such as Pantaloon and Trent , who are against foreign direct investment, argue against market opening. Thus, the retail sector remained closed off while the country as a whole opened up.

Despite the difficult conditions, Metro in India is now building its third wholesale cash & carry store (in the company jargon Cash & Carry ) in Hyderabad . Even Walmart , Carrefour and Tesco want to enter the Indian market. Western companies see great potential in the subcontinent: According to estimates by AT-Kearney, the retail market will grow by 13 percent in 2006 and after that, at 350 billion US dollars, it will not be very developed, but there are more and more wealthy citizens who are in question as customers come. Their number is estimated at up to 300 million.

Wealth and inequality

According to a study by Bank Credit Suisse from 2017, India was ranked 11th worldwide in terms of total national wealth . Total real estate, stocks, and cash holdings totaled $ 4,987 billion. In terms of population, however, wealth is still very low. Per adult it is $ 5,976 on average and $ 1,295 in median (in Germany: $ 203,946 and $ 47,091, respectively). Since 2000, private wealth has more than tripled thanks to the booming stock markets and rising property prices in major Indian cities.

Overall, 14% of the population's total wealth was financial wealth and 86% was non-financial wealth. The Gini coefficient for wealth distribution was 83 in 2017, which indicates extremely high wealth inequality. The top 10% of the Indian population owned 73.3% of the property and the top 1% owned 45.1% of the property. A total of 92.3% of the population had personal wealth less than $ 10,000. At the same time, according to Forbes, there were 131 billionaires in India, which is the third highest number in the world (as of 2018). The richest person in the country was Mukesh Ambani, who had a fortune of 40 billion US dollars and is part of the economically and politically influential Ambani family. It is typical of the country's economy, which is characterized by strong inequality, that in some cases entire sectors of the economy are controlled by individual families.

Imports and exports

Main export and import countries

According to statistics from the Indian Federal Reserve Bank , the main export and import countries in fiscal year 2016/17 were those listed in the table below. India had a significant trade deficit with exports of US $ 276 billion and imports of US $ 382 billion . The largest retail partner was the European Union (10.8% of imports, 17.2% of exports), followed by the United States (5.8% of imports, 15.3% of exports) and the People's Republic of China (16.0 % of imports, 3.7% of exports). Trade with the immediate neighboring countries (Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Maldives, Afghanistan) only accounted for a relatively small proportion (6.9% of exports, 0.7% of imports), as did trade with Africa (4th , 6% imports, 7.2% exports), Latin America (3.7% imports, 4.2% exports) and Russia (1.5% exports, 0.7% imports).

| Country / Region | Exports | Imports | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Million US $ | in % | Million US $ | % | |

| I. Western industrialized countries | 104,930.6 | 37.9 | 107,751.2 | 28.2 |

| A. European Union |

47,599.7 | 17.2 | 41,170.7 | 10.8 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

5,664 | 2.0 | 6,652.2 | 1.7 |

|

|

5,375.4 | 1.9 | 4,610 | 1.2 |

|

|

7,243.1 | 2.6 | 11,485.5 | 3.0 |

|

|

4,944.4 | 1.8 | 3,859.8 | 1.0 |

|

|

5,057.6 | 1.8 | 1,899.4 | 0.5 |

|

|

8,576 | 3.1 | 3,704.2 | 1.0 |

| B. North America | 44,322.3 | 16.0 | 26,174.2 | 6.8 |

|

|

2.008 | 0.7 | 4,072.4 | 1.1 |

|

|

42,314.3 | 15.3 | 22,101.8 | 5.8 |

| C. Asia and Oceania | 7,128.5 | 2.6 | 21,382.2 | 5.6 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

2,964 | 1.1 | 11,131 | 2.9 |

|

|

3,853.9 | 1.4 | 9,746.6 | 2.5 |

| D. other OECD countries | 5,880.1 | 2.1 | 19,024 | 5.0 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

977.9 | 0.4 | 17,244.5 | 4.5 |

| II. OPEC countries | 45,309.9 | 16.4 | 92,445.3 | 24.2 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

2,392.3 | 0.9 | 10,507.8 | 2.7 |

|

|

1,115.7 | 0.4 | 11,700.2 | 3.1 |

|

|

1,494.2 | 0.5 | 4,452.4 | 1.2 |

|

|

5,136.3 | 1.9 | 19,955 | 5.2 |

|

|

31,233.6 | 11.3 | 21,465.4 | 5.6 |

| III. Eastern Europe | 2,820.2 | 1.0 | 9,352.3 | 2.4 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

1,931.7 | 0.7 | 5,554.8 | 1.5 |

| IV. Developing and emerging countries | 120,216.2 | 43.5 | 165,322.3 | 43.2 |

| A. Asia excluding Japan | 88,559.8 | 32.0 | 133,205.7 | 34.8 |

| a). South asia | 19,004.1 | 6.9 | 2,631.9 | 0.7 |

|

|

507.5 | 0.2 | 293.3 | 0.1 |

|

|

6,695.8 | 2.4 | 700.9 | 0.2 |

|

|

489.1 | 0.2 | 134.9 | 0.0 |

|

|

198.2 | 0.1 | 9.2 | 0.0 |

|

|

5,362.1 | 1.9 | 442.1 | 0.1 |

|

|

1,832.3 | 0.7 | 455.7 | 0.1 |

|

|

3,919.1 | 1.4 | 595.9 | 0.2 |

| b). other Asian countries | 69,555.7 | 25.2 | 130,573.8 | 34.1 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

10,207.1 | 3.7 | 61,320.4 | 16.0 |

|

|

14,141.9 | 5.1 | 8,187 | 2.1 |

|

|

4,237.8 | 1.5 | 12,579.9 | 3.3 |

|

|

5,230.8 | 1.9 | 8,932.5 | 2.3 |

|

|

9,561.7 | 3.5 | 7,096.5 | 1.9 |

|

|

3,173 | 1.1 | 5,419.6 | 1.4 |

|

|

3,500.6 | 1.3 | 13,433.5 | 3.5 |

| B. Africa | 19,915.7 | 7.2 | 17,786.5 | 4.6 |

| from that: | ||||

|

|

452.8 | 0.2 | 207.4 | 0.1 |

|

|

2,070.2 | 0.7 | 1,162 | 0.3 |

|

|

2,198.2 | 0.8 | 104.2 | 0.0 |

|

|

3,553.6 | 1.3 | 5,811.7 | 1.5 |

|

|

751.2 | 0.3 | 244.4 | 0.1 |

|

|

1,786.8 | 0.6 | 949.7 | 0.2 |

|

|

237.3 | 0.1 | 744.1 | 0.2 |

| C. Latin America | 11,740.6 | 4.2 | 14,330 | 3.7 |

| V. Others | 772.2 | 0.3 | 365.9 | 0.1 |

| VI. Not further described | 2,498 | 0.9 | 7,504 | 2.0 |

| total | 276,547 | 100.0 | 382,740.9 | 100.0 |

Export and import goods

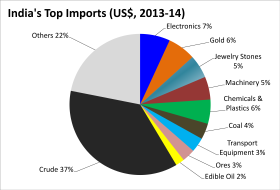

According to data from the Central Bank of India, the import and export goods in 2016/17 were as follows.

| Import goods | Value in US $ million |

percent |

|---|---|---|

| Raw cotton , textile waste | 944.9 | 0.2 |

| Vegetable oils | 10,890.9 | 2.8 |

| legumes | 4252.7 | 1.1 |

| fruits and vegetables | 1776.6 | 0.5 |

| Pulp and waste paper | 974.7 | 0.3 |

| Textile yarn, fabrics | 1500.8 | 0.4 |

| fertilizer | 5028.4 | 1.3 |

| Sulfur and iron pyrite | 131.1 | 0.0 |

| Metal ores and other minerals | 6168.4 | 1.6 |

| Coal, coke , briquette | 15,715.2 | 4.1 |

| Crude oil, refined oil | 86,865.7 | 22.7 |

| Wood and wood products | 4892.9 | 1.3 |

| Leather and leather products | 936.0 | 0.2 |

| Organic and inorganic chemicals | 16,578.4 | 4.3 |

| Dyeing and tanning materials | 2282.0 | 0.6 |

| Artificial resins, plastic materials | 11,961.1 | 3.1 |

| Chemicals and chemical products | 5366.5 | 1.4 |

| Newsprint | 850.3 | 0.2 |

| Pearls, precious stones , semi-precious stones | 23,848.8 | 6.2 |

| iron and Steel | 11,689.9 | 3.1 |

| Non-ferrous metals | 9871.7 | 2.6 |

| Machine tools | 3035.9 | 0.8 |

| electrical and non-electrical machines | 28,662.5 | 7.5 |

| Transportation equipment | 21,224.4 | 5.5 |

| Project goods | 2106.3 | 0.6 |

| Professional instruments, optical goods | 3848.8 | 1.0 |

| Electronic goods | 41,941.0 | 11.0 |

| Medical and pharmaceutical products | 4997.6 | 1.3 |

| gold | 27,490.4 | 7.2 |

| silver | 1838.2 | 0.5 |

| Other consumer goods | 25,068.9 | 6.5 |

| Total imports | 382,740.9 | 100.0 |

| Export good | Value in US $ million |

percent |

|---|---|---|

| tea | 734.4 | 0.3 |

| coffee | 845.2 | 0.3 |

| rice | 5773.9 | 2.1 |

| Cereals other than rice | 212.3 | 0.1 |

| tobacco | 961.7 | 0.3 |

| Spices | 2887.5 | 1.0 |

| Cashew | 790.7 | 0.3 |

| oil cake | 800.7 | 0.3 |

| Oilseeds | 1361.7 | 0.5 |

| fruits and vegetables | 2439.9 | 0.9 |

| Cereal preparations, processed foods | 1272.6 | 0.5 |

| seafood | 5918.1 | 2.1 |

| Meat, dairy products, poultry | 4389.4 | 1.6 |

| Iron ore | 1525.3 | 0.6 |

| Mica , coal and other ores | 3536.7 | 1.3 |

| Leather and leather products | 5183.0 | 1.9 |

| Ceramic products, glass | 1861.8 | 0.7 |

| Precious stones and jewels | 43,509.6 | 15.7 |

| Medicines and pharmaceutical products | 16,829.4 | 6.1 |

| Organic and inorganic chemicals | 12,425.9 | 4.5 |

| Technical goods | 67,132.6 | 24.3 |

| Electronic goods | 5959.4 | 2.2 |

| handcrafted or spun textile products | 9893.6 | 3.6 |

| Yarns, textiles and manufactured textiles | 4559.7 | 1.6 |

| Assemblies of all textiles | 17,452.8 | 6.3 |

| Jute products | 311.3 | 0.1 |

| Carpets | 1494.0 | 0.5 |

| Manual work without carpets | 1926.9 | 0.7 |

| Products made from crude oil | 31,622.3 | 11.4 |

| Plastic and linoleum | 5816.1 | 2.1 |

| Other goods | 17,118.7 | 6.2 |

| Total exports | 276,547.0 | 100.0 |

literature

German

- Oliver Müller: India as an economic powerhouse. Opportunity and challenge for us. Hanser Verlag, 2006, 302 pages ISBN 3-446-40675-1

- Olaf Ihlau: World power India. The West's New Challenge; Siedler Verlag Munich, 2006; ISBN 3-88680-851-3

- German Society for Foreign Policy (Ed.): Internationale Politik, Issue 10/2006

- Johannes Wamser: Location India. The subcontinent as a market and investment destination for foreign companies. Lit Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8766-9 .

- Dirk Bronger, Johannes Wamser: India - China. Comparison of two development paths. Lit Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-9156-9 .

- North-South network of the DGB Bildungswerk (ed.): “... you can't see those in the shade. Informal Sector in India " (2007)

English

- Roel van der Veen: India's Road to Development; The Hague, Clingersael Institute, Clenkenael Diplomacy Paper 6, 63 pp. June 2006, ISBN 90-5031-107-5

- Innovation Norway: International Business Report India 2006 ( PDF )

- India's National Innovation System: Key Elements and Corporate Perspectives, Working Paper, TU Hamburg-Harburg. ( PDF ; 614 kB)

Web links

- India News Business - India business news with monthly PDF newsletter

- Handelsblatt Special Economic Power India

- German Bundestag (ed.): The Parliament, No. 32-33 / 2006, August 7, 2006; Enclosure: India - A continent is breaking up

- Foreign trade portal Bavaria: Links to economic information on India

- Foreign trade portal ixpos: India, Market of the Month, April 2006

- Federation of German Industries: India on the way to becoming an economic powerhouse, April 2006 (PDF file; 51 kB)

- Indian economy - the medium to the growth market

- KAS foreign information (5/10): Förstmann, Rabea / Gregosz, David: "India's economic policy and the need for an economic model"

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Report for Selected Countries and Subjects. International Monetary Fund, accessed April 29, 2017 (American English).

- ↑ a b Report for Selected Countries and Subjects (GDP, PPP and nominal change in percentage). Retrieved April 30, 2017 (American English).

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database, June 2017. IMF, accessed June 10, 2017 (American English).

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database (June 2017) GDP per capita (KKB). IMF, accessed June 10, 2017 (American English).

- ^ Sector-wise contribution of GDP of India. Statisticstimes.com (data source: Ministry for Statistics and Program Implementation), accessed December 26, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d India: 2017 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff report; and Statement by the Executive Director for India. International Monetary Fund, February 22, 2017, accessed December 26, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Table 134: Direction of Foreign Trade - US Dollar. Federal Reserve Bank, September 15, 2017, accessed December 25, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Table 128: Exports of Principal Commodities - US Dollar. September 15, 2017, accessed December 30, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Table 130: Imports of Principal Commodities - US Dollar. Reserve Bank of India, September 15, 2017, accessed December 30, 2017 .

- ↑ GDP ranking | Data. In: data.worldbank.org. Retrieved April 22, 2016 .

- ↑ India is the world's 4th fastest growing economy; but why you might not care about the other three. Financial express, September 19, 2017, accessed October 29, 2017 .

- ↑ At a Glance: Global Competitiveness Index 2017–2018 Rankings . In: Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018 . ( weforum.org [accessed December 6, 2017]).

- ↑ Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom. Retrieved December 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Five Year Plans. Government of India Planning Commission, accessed April 21, 2016 .

- ↑ GDP at Factor Cost at 2004-05 Prices, Share to Total GDP and% Rate of Growth in GDP (31-05-2014). (PDF) Accessed in 2015 .

- ↑ Growth Rate - GSDP% (Const. Prices) as per States / UTs from 1997-98 to 2013-14. (PDF) Indian Planning Commission, accessed on February 20, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Table 242: Combined Deficits of Central and State Governments (As Percentage to GDP). Reserve Bank of India, September 15, 2017, accessed December 27, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c OECD: Economic Outlook December 2007

- ↑ Global Wealth Report 2017 . In: Credit Suisse . ( credit-suisse.com [accessed January 1, 2018]).

- ^ Meet The Members Of The Three-Comma Club. Forbes, March 6, 2018 (English).