feminism

Feminism ( derived from French féminisme from Latin femina 'woman' and -ism ) is a generic term for social, political and academic currents and social movements that, based on critical analyzes of gender orders , for equality , human dignity and self-determination of all people of all sexes as well stand up against sexism and try to implement these goals through appropriate measures. In addition, feminism referson political theories that - beyond individual issues - focus on the totality of social conditions, a fundamental change in the social and symbolic order and gender relations. At the same time, they allow interpretations and arguments for social criticism .

Feminism experienced its boom in Europe with the emancipation efforts of women in the course of the Enlightenment ; around the world it is repeatedly used in connection with general civil rights and freedom movements. Feminism makes it clear that the ideal of equality for all people, as it was spread primarily through the bourgeois emancipation from the feudal system , does not correspond to everyday experiences of women. Accordingly, a conflict is diagnosed between the enlightenment claim to equality on the one hand and the reality of life of women in modern times and modern on the other. On this basis, feminism also includes the demand not only to formally (legally) postulate equality between women and men , but also to contest those concrete conditions in which this promise has still not actually been kept. To this end, sat feminists and feminists with the philosophical arguments for and against the unequal treatment apart and developed different feminist theories and approaches as critical cultural and social analysis. However, a uniform feminism, the definition of which would have worldwide validity, is not necessarily a desirable goal nowadays, since women come from different cultures and social conditions that can shape them more than gender.

term

Term used in medicine and zoology

In medicine and zoology, “the presence or development of female sexual characteristics in men or in male animals” is classified as a medical disorder that has been referred to as feminism , feminization or feminization since the mid-19th century .

The pathologization of bodies that were not clearly bisexual was the result of growing pressure in the 19th century for bourgeois gender roles to be clearly bisexual . The scientific specialist publications were characterized by the fear and disgust of the male experts of degeneration or the development of a preliminary stage or accompanying symptom of infantilism and intellectual disability . The cases were seen as very rare, but transitional cases as common. The Belgian botanist Emile Laurent (1861–1904) spoke of hermaphroditic formations, feminism, hermaphrodism , feminism, but also of masculinism . Feminism was used as a generic term for physical developments in men, such as the increased formation of breast tissue ( gynecomastia ) or the underdevelopment of testicles or penis ( hypoplasia ).

Extension of meaning in French in 1872: féministe

The meaning of the word feminism has expanded in French . In writing, the word as féministe can be traced for the first time in 1872 in the book L'Homme-femme (literally The Man-Woman ), in which Alexandre Dumas the Younger replied to an article by the French diplomat and writer Henri d'Iveville .

“ Feminists , if you allow me this neologism , have the best intentions when they assure you that the whole evil lies in the fact that one does not want to recognize that women belong entirely to the same level as men and because their upbringing is not the same gives and does not grant the same rights as men; the man misuses his superior strength, etc. (...) In fact, the male sex has used its strength almost first of all to restrict the female sex, which is indispensable to him, as far as possible and to subordinate itself; for the man noticed only too early that he had the freedom of the woman, even in a paradisiacal stay, to pay too dearly. "

Dumas' book met with a wide response in the increasing gender-political debate and was also translated into German in the same year under the title " Mann und Weib ". The French publisher and journalist Émile de Girardin confirms Dumas' new word in his answer. Since feminisme had been a term for a medical pathology in French up to then , he accused Dumas of making women look ridiculous and discrediting their efforts to emancipate:

"So here is the woman whose emancipation you are fighting against by ridiculing her and calling those who disagree with you" feminists "! Feminist ! That's how it should be."

Historical background

With the French Revolution and the Declaration of Human and Citizens' Rights (1789), gender relations in the western world became an increasingly discussed topic. In the 1830s the words socialism and individualism and only in 1872 the word feminism emerged in order to be able to discuss the new political issue of gender relations and gender politics .

The gender ratio was also discussed between men, because numerous men also advocated equality for women. These included, for example, the social philosopher Charles Fourier (1772–1837). For the first time, he defined the degree of women's liberation as a measure of social development and formulated: "Social progress [...] takes place on the basis of the progress made in women's liberation."

Due to countless circular references, the origin of the word was wrongly attributed to the social philosopher Charles Fourier (1772-1837) for a long time . In his work, however, the word cannot actually be proven.

As early as the beginning of the 20th century, countless sub-terms emerged for the generic term feminism, such as bourgeois feminist, Christian feminist, radical feminist, male feminist.

Self-description of women's rights activist Hubertine Auclert 1882

The first women's rights activist to use the term as a self-description was the French Hubertine Auclert in 1882 . At the International Congress for Women's Work and Efforts in Berlin in September 1896, which Lina Morgenstern , Minna Cauer and Hedwig Dohm helped organize, 1,700 participants from Europe and the USA debated the status of women's issues. The French delegate Eugénie Potonié-Pierre briefed the press on the term feminism and what it means. From then on it found increasing international distribution.

International spread of Gallicism

In order to discuss the central gender political issue of women's emancipation , the terms féministe and féminisme were quickly adopted in other languages ( Gallicism ). Feminism was used as synonyms for women's emancipation and for movements and people who proclaimed women's rights

“Feminism” was hardly used in Germany under the Empire, with the exception of the feminist pioneer Hedwig Dohm and the radical wing of the bourgeois women's movement around Minna Cauer, Anita Augspurg , Lida Gustava Heymann and Käthe Schirmacher . However, it was rejected by the majority of the German women's movement, on the one hand to distinguish it from France, on the other hand because the term was used early on by opponents of feminism to devalue the emancipation movement. (See anti-feminism )

The first mention of the term in Great Britain is documented for the years 1894/1895. It has been in use in the United States since 1910. In the 1920s it also found its way into the Japanese and Arabic languages.

In Germany, the term “women's emancipation” was far more common than feminism until the middle of the 20th century. It was only with the Second Women's Movement in the 1970s that the term spread as a positive self-description for members of the movement. Since the late 1970s, the term "feminism" has been used more often than "women's emancipation"

“The vision of feminism is not a 'female future'. It's a human future. Without role constraints, without power and violence, without male bundling and femininity. "

Differentiation between feminism and the women's movement

The terms feminist and feminism are Gallicisms : at the end of the 19th century, the words féministe and féminisme were adopted from French into German . From the beginning this led to a change in meaning in the form of a narrowing of meaning as meaning deterioration (pejorization) .

The basic principles of equal human dignity and equal rights for women , based on the spirit of the French Revolution , caused “unrest” in German-speaking countries from the start. The words feminism and feminist had a “smell of radicality” and were rarely used to describe themselves, but mostly “derogatory and denouncing by the opponents of women's emancipation”. It was only with the second wave of the women's movement in the 1970s that the terms were increasingly used for positive self-designation. However, the German terms feminism , feminist and feminist still have a strong negative connotation to this day, and only a few people like to identify with them openly, as this often leads to serious devaluations to this day.

Until the end of the 19th century, the most common generic term in German was the word Frauenfrage , after which it was replaced by the word women's movement . The generic term feminism is used much less in German. In contrast to German, the generic term féminisme or feminism is the main term used in French and English .

Today, the terms feminism and women's movement are often used synonymously in colloquial language as well as in specialist language . In the technical language, there are individual attempts to delimit the content, e.g. feminism as a theory and policy-related part of the women's movement.

Today's intellectual, social, political, religious and academic currents and social movements that stand up for the interests of women hardly use the terms women's movement or women’s movement to describe themselves , but rather the terms feminism and feminist . The term women's movement today is not associated with the women's movement or feminism of the present, but that of the past. In this respect, the “times of the women's movement” are considered to be closed and their goals to a certain extent “out of date”, while those of feminism in the current times of neoliberalism are not.

Overview

Feminism advocates a social structure in which the oppression of women, which it has analyzed as a social norm , has been eliminated and gender relations are characterized by equality. For the historian Karen Offen , such an understanding of feminism also includes men whose “self-image is not based on domination over women.” Feminism regards the social systems that have prevailed in history up to now as androcentric and interprets this fact as structural patriarchal rule . On this basis, currents and forms have developed that partly complement each other, but also contradict each other.

Whereas in the 1970s the term “feminist science” was common, since the 1980s the assessment has gained ground that scientific institutions and theory building in individual subjects can be criticized from a feminist point of view (feminist criticism of science), but that science itself cannot be feminist . Feminist philosophy of science and feminist research make it their task to make the previous omissions of female history and the achievements of women visible and to make feminism fruitful for all fields of science. To date, no unified feminist theory has emerged, and it is debatable whether this is possible.

The philosopher and social scientist Christina Thürmer-Rohr wrote about feminist research :

“Feminist research does not fill any gaps, it is not an as yet missing ingredient in the common research subjects in the form of the unsophisticated or wrongly cultivated woman. It lies across all of these 'objects'. It is lateral thinking, counter-questions, contradiction, objection. "

The political and social movement of feminism repeatedly ran into crises. The withdrawal into the private was followed by some feminists turning to the esoteric, to a “new femininity”, which is now partly interpreted as a separate direction of feminism, partly viewed as a further development of traditional difference feminism, but also criticized as depoliticization.

Successes of feminism can be described above all in the areas of political and legal equality, such as the introduction of women's suffrage, education, sexual self-determination, human rights for women and the emancipation of women and girls from prescribed life courses and role models.

In the course of other equality movements such as the Afro-American civil rights movement or the independence struggles in the colonial areas, feminism later also grappled with the question of the philosophical consequences of the differences between the experiences of women from different social classes, with different skin colors or with Western and non-Western origins to have. This first criticism of a universal experience and a common interest of all women was later followed by currents that were primarily devoted to questioning gender categories: the philosophical and political debate had revealed their dynamism and malleability, which some feminists took as an opportunity, their fundamental ones Eligibility to discuss. Nevertheless, the reference to the female gender and the goal of fair participation remain important resources of feminist argumentation and politics to this day.

Goals and themes of feminism

Goal: Recognition and respect for equal human dignity for women

The fundamental goal of feminism and the women's movement is the fulfillment of modern basic social principles that have been increasingly spreading since the French Revolution , including for women. It is first about the basic principle of “recognition of their equal human dignity ” for women, through which the fundamental “principles of freedom and equality of all people ” for women come to the fore.

The “invocation of human dignity” causes a “ taboo removal ” of asymmetrical social gender orders , in which dignity is a “gender-related defined concept”. On the basis of “ role-related expectations of decency” , the dignity of men is considered to be honest , the dignity of women as modesty . In everyday life, behavior is then rated as 'worthy' or 'unworthy' with the help of gender stereotypes . If, on the other hand, human dignity is considered inviolable regardless of gender, there is no justification for violating it. In this respect, the basic principle of human dignity promotes better observance of fundamental rights to freedom and equality.

British writer and journalist Rebecca West sarcastically summed up the central importance of recognizing and respecting the human dignity of women . Its formulation in an article in the British newspaper The Clarion in 1913 became one of the most famous quotes describing the fundamental goal of feminism:

“I never found out exactly what feminism actually is myself. I only know that I am called a feminist whenever I am not mistaken for a doormat or a prostitute. "

To this day, the recognition of and respect for the human dignity of women is not only an implicit goal in a number of issues, but is often also explicitly named - for example in the case of sexist advertising , sexual harassment and sexual violence , pornography , prostitution , reproductive rights or the right of asylum .

Sub-goals and topics

On the basis of this fundamental feminist goal, numerous, sometimes opposing currents have developed, all of which are summarized under the umbrella term of feminism. The central debates of feminism are different in different countries and are subject to change. From the 1960s onwards, the following topics were taken up, for some of which the feminist pioneers at the end of the 19th century had fought:

- Equal rights (political equality, women's suffrage , education, marriage and divorce law)

- Economic and social function of housework / reproductive work ( housewifeization , care work )

- Equality (e.g. quotas for women , wage discrimination , work-life balance )

- Women's rights as human rights (e.g. female genital mutilation )

- Violence against women

- Women as accomplices in violent relationships, e.g. B. Women as accomplices in National Socialism

- Construction or deconstruction of gender identity

- Feminist language criticism

- Women's Biography Research

- Relationship of gender, class , ethnicity ( intersectionality )

- Sexual self-determination ( rape , sexual abuse , lesbian women)

- sexism

- Reproductive self-determination (e.g. termination of pregnancy )

- Feminist science criticism

- Women's studies and gender studies in all scientific areas

- Women's networks , women's peace movement (since the first women's movement).

On the history of feminism

Beginnings

Early ideas of European feminism can be found in the writings of Marie Le Jars de Gournay , who proclaimed human rights as early as the 17th century. But the writings of Christine de Pizan , Olympe de Gouges , Mary Wollstonecraft and Hedwig Dohm are also considered early works of European feminist philosophy avant la lettre .

Feminism as a theory and worldview first emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when constitutions with catalogs of fundamental rights were passed in the wake of the bourgeois revolutions . However, women were only provided to a limited extent as bearers of these fundamental rights. Olympe de Gouges protested against this in France . In 1791 she compared the 17 articles of the Declaration of Human and Civil Rights , which only related to men, with her women's rights in 17 articles, which contained the famous sentence:

«La femme a le droit de monter sur l 'échafaud; elle doit avoir également celui de monter à la Tribune »

“The woman has the right to climb the scaffold. Likewise, it must be granted the right to climb a speaker's platform "

Political participation rights, which were initially fought for or granted in the revolution, were soon restricted again. After publicly attacking Robespierre and calling for a vote on the form of government, Olympe de Gouges was executed at the instigation of the Revolutionary Tribunal in 1793 . 1792, the English writer Mary Wollstonecraft published her work Vindication of the Rights of Woman (The Defense of Women's Rights ), in which she analyzed the situation of women caught in a net of false expectations. She advocated that women can train to sustain themselves. Women could e.g. B. be doctors just like men. Marriage should be based on friendship, not physical attraction. Their goal was to achieve full civil rights for all women.

First wave

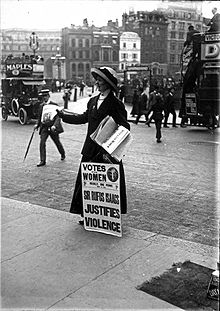

Around the middle of the 19th century, the first wave of feminism and the women's movement emerged in many countries in Europe, the USA and Australia. British suffragette Josephine Butler has been campaigning against the Contagious Diseases Acts since 1869 , under which prostitutes were monitored by the state, but the suitors were not controlled. As a result, women alone, not their male customers, were responsible for the spread of sexually transmitted diseases . Such double standards have been combated not only in Great Britain but also in other countries . The abolitionism movement widely questioned international social and sexual conventions that had never been publicly discussed before.

In 1882 , in the magazine La Citoyenne, which she edited, Hubertine Auclert developed the term feminism as a political guiding principle against the masculinism that, in her opinion, was prevalent in French society at the time . In 1892 there was a congress in France with the word feminism in the title, and in 1896 Eugénie Potonié-Pierre reported at the International Women's Congress in Berlin that the term had gained acceptance in the French press. In the next few years the term also spread internationally; it was sometimes used synonymously with the women's movement, also by their anti-feminist opponents.

The German socialist Clara Zetkin demanded at the Second Congress of the Socialist International in Copenhagen in 1910: "No special rights, but human rights". A year later, women took to the streets for the first time in Germany, Austria, Denmark and Switzerland. Your central demand: introduction of women's suffrage and participation in political power. With the exception of Finland , women were not allowed to vote in any European country at that time, but only after the First World War . The representatives of the First Women's Movement strove for political equality with men and an end to civil law relationships between father and husband, equal pay for equal work, access for women to the university and all professions and offices.

Almost at the same time, the term androcentrism was developed by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in her book “The Man-Made World or Our Androcentric Culture” in 1911 . It was criticized there as a specific form of sexism , in which the feminine is understood as "the other", "that which deviates from the norm".

The first wave of feminism ebbed in the 1920s. Basic demands such as women's suffrage were met in some countries. As a result of the introduction of women's suffrage, the female MPs not only dealt with the further enforcement of access to previous male professions, such as judicial office, but also with social legislation and dealing with prostitution and antisociality. In the Great Depression that began in 1929, competition for jobs intensified, and women were usually the first to be laid off. Numerous factors now worked together to restore women to their traditional place.

The demands for women to study were accepted in many countries towards the end of the 19th century, but initially only very few women studied, like Rosa Luxemburg . The first full professor in Germany was Margarete von Wrangell ; the second Mathilde Vaerting , she was excluded from university service by the National Socialists in 1933, as did Marie Baum and Gerta von Ubisch, among others . As the first female physicist in Germany, Lise Meitner became the first female professor at Berlin's Humboldt University in 1926. Like many other Jewish scientists, she had to emigrate and was unable to continue her academic work in Berlin. She fled to Sweden in 1938.

Women during the Nazi era were given limited study opportunities; Between 1933 and 1945, the National Socialist, and especially the racial, laws led to a decisive break in university employment and career opportunities for women. Women's organizations were dissolved or brought into line . Anita Augspurg and Lida Gustava Heymann , pioneers of the first women's movement and opponents of the Nazi regime, had to live in exile in Switzerland from 1933; Alice Salomon was forced into exile in 1939.

After two world wars, the restoration of rigid gender roles and the model of marriage and the nuclear family as the dominant way of life were an important part of an alleged "normalization" of living conditions. Although women had coped with life on their own under the most difficult conditions in the war and post-war period, this included the clear instruction to return to home and family as a true place of female destiny. In all western industrial nations that were involved in World War II, a restructuring of traditional gender relations took place in the post-war period.

Second wave

“The feminist movement began in the sixties / seventies with the thesis that women - beyond biology - have something in common, namely a violent history of damage and exclusion that has marginalized them, defines them as inferior people excluded public participation and exposed it to everyday violence. "

The formation of the women's movements in West Germany and other European countries was preceded by the American women's movement, the Women's Liberation Movement (Women's Lib). When the first autonomous women's groups were hesitantly constituted in the Federal Republic, a broad network of women's organizations and women's groups had already developed in the United States. The first new feminist grouping was the National Organization for Women (NOW) founded in June 1966 .

In order to understand the significance of the feminist awakening since the 1960s in the Federal Republic of Germany, one has to consider the conditions for women. In the mid-1960s, girls, especially from working-class and rural families, were clearly underrepresented in secondary schools, and significantly more men than women studied. There were hardly any female scientists or university lecturers at universities. Women were hardly represented in political representation either, although the inclusion of equality in the Basic Law was largely thanks to politicians like Elisabeth Selbert . Only every third woman was gainfully employed; the distribution of professions largely followed gender-specific stereotypical attributions, such as the so-called low - wage groups and “ women's professions ”. The general legal situation of women did not correspond to that of men. The husband, as the legally defined “head of the household ”, was able to make binding decisions on his own. Until 1962, women were not allowed to open or dispose of their own bank account without their husband's consent. Still to 1977 who wrote Civil Code provides that a woman needed her husband's permission for their own careers. Even when he allowed it, he administered their wages. In divorce law , the principle of guilt applied, so that housewives who were “guilty” divorced were often left without any financial support. Marital rape was covered by the construct of conjugal duty, abortion was forbidden, and childcare was largely the responsibility of women.

The second women's movement in West Germany began with a tomato throw. In a lecture on September 13, 1968 at the 23rd delegates' conference of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS), Helke Sander accused the SDS men of not going far enough in their social criticism because they ignored the discrimination against women. The SDS itself is the reflection of a male-dominated social structure. Since the comrades were not ready to discuss this speech and wanted to go back to the agenda, Sigrid Rüger threw tomatoes in the direction of the board table and met Hans-Jürgen Krahl . On the same day, women founded “women's councils” in the various regional associations of the SDS. Soon afterwards women's groups split off from the SDS, and an autonomous women's movement with new forms of organization such as women's centers emerged. This started a storm on the diverse forms of institutionalized inequality: “Division of labor, role ascriptions, patterns of representation, laws, theory and interpretation monopolies, sexual politics and heterosexism. These dimensions of inequality were thematized in very different ways in the women's movement - autonomously or institutionally; provocative or mediating; radical or moderate. ”For the active equality of women, new political models had to be“ invented ”first. What was new about the second women's movement was the extent to which it questioned the mundane. One of the slogans was " The personal is political " (Helke Sander).

Contraception, abortion, sexuality, violence, abuse

In 1971, in protest against the prohibition of abortion in Section 218, a movement was formed that went far beyond the feminist discussion groups: We have had an abortion ! , Aktion 218 , which however remained without structures and fixed location; Both were first brought about by the women's centers, which were founded in many cities in the Federal Republic from 1973, the first being the West Berlin women's center in 1973 .

Self-determination about female sexuality was a central topic there: advice on abortion , trips to Holland (to abortion clinics), campaigns for the gentle suction method and the deletion of § 218 tied up forces at the beginning. The group “Bread and Roses” around Helke Sander wrote the women's handbook No. 1 on the side effects of the birth control pill in 1973 . In protest against the common practice of gynecologists (then only men), women explored their bodies themselves with a speculum and mirror (see: Vaginal Self-Examination ) and formed self-help groups , inspired by the work of the Boston group Our Bodies Ourselves . They published this experience in the book Hexengeflüster and founded the Feminist Women's Health Center FFGZ. In addition to the problems with contraception , women in the women's centers discussed their sexual experiences and the essay The Myth of Vaginal Orgasm by the radical feminist Anne Koedt , which women from the women's center in West Berlin translated and published.

The women's centers literally 'discovered' the problem areas of rape , domestic violence , and sexual abuse : they discussed private matters publicly, showed their bruises, took care of the victims and named the perpetrators. The lawyer Alexandra Goy introduced the secondary lawsuit for abused and raped women who - although "only" witnesses in court - were able to question the perpetrator through their legal counsel. Activists of the women's centers created protective facilities such as emergency calls , women's shelters and self-defense for women.

Structures

The orthodox and dogmatic left saw the women's question as a 'side contradiction ':

“First the main contradiction - that between wage labor and capital - must be resolved, then the oppression of women would also be abolished. Since women's emancipation would later set itself up, it was not worth founding women's groups, unless as a 'water heater' - as the training of women was called at the time - to recruit them for the party. "

A comrade from a K party depressed an imminent abortion:

“The women I asked for advice dismissed it as a triviality, but for me it was a pretty big problem. I couldn't tell the men I worked with. Then it became clear to me that you can't do anything with them as a human being. Such problems were simply not to be addressed because there was a strict separation between private sphere and political work, and I was forced to solve this problem in my private sphere. "

“These hierarchical and dogmatic structures on the left sucked up the rebellious potential and stifled it. [...] The women's movement and citizens' groups had to start all over again: with their own concerns. […] The women's movement in the women's centers was an educational movement which, through the means of self-exposure (self-accusation, abortion on television, publicizing sexual abuse), brought unsustainable conditions to light and broke taboos. "

All of these discoveries were only possible because these women's centers were structured fundamentally differently than all political groups of the 1970s, such as the Socialist Women's Association: There all new women had to undergo a year-long training in Marxist texts before they could turn to topics of their own choosing.

Theories

In the 1970s, feminists began to deal theoretically with social inequality and the term 'work'. The founders of the women's centers came from the socialist left and initially read Friedrich Engels The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State and August Bebel's Women and Socialism , but criticized them.

Inspired by the Wages for Housework Congress (Italy 1971) and the book The Power of Women and the Overthrow of Society (1973 in German) by Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James , a controversial feminist discussion about the nature of housework and its nature began in West Germany Function for reproduction. The women's research emerging at the time was about “making visible the private work of women that was previously invisible”.

The texts of American feminists, especially Kate Millett's Sexus and Reign and Shulamith Firestone 's Women's Liberation and Sexual Revolution , which analyzed the power imbalance between the sexes, raised awareness .

Authors of the First Women's Movement in German-speaking countries had to be rediscovered by the New Women's Movement, including Anita Augspurg and Lida Gustava Heymann . Early writings with great influence were also Mathilde Vaerting : Frauenstaat und Männerstaat (1921) and Bertha Eckstein-Diener : Mothers and Amazons (1932). Both texts opened a glimpse of supposedly historical matriarchal forms of society, which showed that patriarchy and feminine secondary status are not natural and universal. Both books were brought into circulation as pirated prints by the West Berlin Women's Center. Among other things, they provided arguments against Simone de Beauvoir's assertion: “This world has always belonged to men…” Books by contemporary women authors on early history that were received were In the Beginning Was the Woman (1977) by Elizabeth Gould Davis and Les femmes avant le patriarcat (1976) by Francoise d'Eaubonne. Well-known feminist authors such as Marielouise Janssen-Jurreit and Ute Gerhard warned against matriarchal escapism , according to Cäcilia Rentmeister , giving time without further historical research or considering contemporary matrilineal societies.

Later, the intellectual feminist currents that were fundamental in West Germany emerged, such as socialist feminism, equality feminism, difference feminism and separatist lesbian feminism. (See: The emergence of lesbian feminism ) The European emancipation thinking , but also impulses from other Western European countries, especially France, from the USA and the so-called Third World influenced these currents.

Third wave

While there has been talk of the end of second feminism in Germany since 1989, new feminist initiatives have emerged locally and globally that are known as the third wave of feminism . Their starting point was the World Conference on Women , organized by the United Nations since 1975 , which provided a platform for international networking for feminists in the Third World . The philosophers Martha C. Nussbaum and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak are among the feminist thinkers who are engaged in questions of transnational politics .

Various authors also view ecofeminism as the third wave of feminism .

In the 1990s, the riot grrrl movement emerged in the USA from a punk context. Elements of the Riot Grrrl movement were also picked up in Germany and turned into the third wave of feminism. Influential authors and activists are Jennifer Baumgardner , Kathleen Hanna and Amy Richards . The young feminists of the third wave work primarily with the Internet and in a goal-oriented manner in projects and networks with a feminist orientation, such as the Third Wave Foundation, which was founded in the USA in 1992 . Internet projects such as Mädchenmannschaft and Missy Magazine emerged in German-speaking countries , a movement that comes under the heading of net feminism .

Since mid-2000, other groups have been articulating themselves in direct actions using artistic and parodic means. These include the Slutwalks , One Billion Rising, and Femen . According to Sabine Hark , this shows “a resolute 'no' […] to sexisms of any kind” and a connection with the forms of protest of feminism of the 1970s.

criticism

The second wave of the women's movement arose in Western Europe and the USA from the criticism of post-war capitalism; it became increasingly professional and institutionalized since the 1970s and was associated with a further development at that time, the rise of neoliberalism . According to Nancy Fraser (in an article from 2013), the women's movement has meanwhile developed into the “stooge of the new, deregulated capitalism ”. With the politicization of the private, there has been a one-sided concentration on cultural “gender identity” ( identity politics ), while economic injustices are given less attention. This fits with neoliberalism, the aim of which was to shift the focus away from issues of social equality. Furthermore, discrimination against women, for example in the labor market, was seen as a distinct phenomenon. However, according to British political scientist Albena Azmanova, these disadvantages are a sign of larger unjust structures that also include other social groups. Within the neoliberal system, the efforts of the women's movement for more participation in the labor market ultimately led to an increase in wage hours per household, with simultaneously falling wages and precarious working conditions. A “ progressive” neoliberalism emerged.

Key Works of the Second Wave

The opposite sex

Long before the start of the New Women's Movement, Simone de Beauvoir had analyzed the female life situation in detail in her highly acclaimed work Le Deuxième Sexe (literally: the second gender; 1951 under the German title The Other Sex ). De Beauvoir's initial questions are: What is a woman? Why is the woman the other ? The philosophical background of their investigation is existentialism ; it fills the void that the socialist approach leaves in understanding the situation of women. The difference between the sexes, which at the same time serves as a justification for the oppression of women, is, according to de Beauvoir, not natural but cultural. The construction of women as the opposite sex can only be explained from the prevailing morals, norms and customs of a culture. In her book, Beauvoir calls on women not to be satisfied with their status as a complement to men and to claim their equality in society in every respect. She campaigned for the demystification of motherhood and the right to abortion . The opposite sex is regarded as the standard work and starting point of feminist philosophy . A key quote from this work reads:

"You are not born a woman, you become one."

The madness of femininity

A book by the American Betty Friedan marked the international new beginning of the second women's movement: The Feminine Mystique was published in New York in 1963 (German: Der Weiblichkeitswahn , 1984). In it she drafted a critical analysis of American society. It showed that advertising, the mass media and other ideology-conveying institutions produced the idea of a fulfilled existence as a housewife and mother, and through numerous interviews it showed how little this ideology corresponded to the actual experience of women. She saw the reduction of women to their roles as housewives and mothers as the cause of the discontent and unfulfilledness of many middle-class women. Instead, Friedan advocated that a woman could only achieve herself if she also considered her own needs. She saw the central key to self-liberation in the employment of women, although this does not exclude marriage and motherhood.

"As for a man, the only way for a woman to find herself is through creative work."

Sex and domination

Kate Millett's work Sexual politics (1969, German Sexus und Herrschaft , 1970) decisively shaped the discourse of radical feminism in the 1970s and 1980s. For the first time, the relationship between man and woman is understood as a relationship of domination and analyzed from this perspective. Kate Millett regards patriarchy as the fundamental relationship of exploitation and oppression, since it occurs as a constant in almost all social formations, including socialist ones. It is therefore above class contradiction. Although Millett also called herself a socialist, she called for immediate and immediate combat against patriarchy, without waiting for a socialist revolution that was not on the agenda. In this struggle men and women are irreconcilable. In other parts of her book, she analyzes the anthropological and religious myths that justify the oppression of women. She also criticizes writers such as D. H. Lawrence , Henry Miller and Norman Mailer , whom she accuses of contributing to the humiliation and submission of women with their patriarchal eroticism. In doing so, she addressed another important topic of feminism in the 1970s, namely its position on sexuality and pornography.

Currents within feminism

Feminism is used in international research as an analytical term for political theories that aim to abolish gender hierarchies or gender differences. There is no single feminist theory, but many different approaches and currents. The undisputed core question of all feminist currents is inequality in the fields of political, economic and intellectual participation as well as the criticism of violence. Feminist theorists from Mary Wollstonecraft to Martha Nussbaum regard being able to lead a self-determined life without violence as a condition for the possibility of freedom and equality for women.

The philosopher Herta Nagl-Docekal summarizes the development of European, feminist thought in three stages: at the beginning there was the emancipation of women, which was based on gender equality; on the second stage there followed the perception of the otherness of the feminine in a positive sense, which is at least equal to, if not superior to, the masculine (difference thinking); then the goal of changing society from the point of view of equal rights for both sexes would arise.

Radical feminism

The American feminist movement preceded the European feminist movement. One of the first organizations in which women and men united in the tradition of the reform policy of the first women's movement was the National Organization for Women (NOW) founded in 1966 by Betty Friedan among others . In contrast, a so-called radical feminism (originated in the 1960s radical feminism ), the representatives of the student New Left and the civil rights movement ( Civil Rights Movement came). Despite the prevailing equality rhetoric, they saw themselves as discriminated against in these movements as in the rest of society and began to found autonomous women's groups in the big cities, including the New York Radical Women , the Women's Liberation group in Berkeley and the Bread and Roses collective in Boston . that saw itself as anti-capitalist and anti-racist . The New York Radical Women developed the analytical method, consciousness-raising , which women used to explore the political aspects of their personal lives. One of the movement's slogans was Sisterhood is powerful . One of the most important initiators and theorists of radical feminism was Shulamith Firestone . She postulated that at the end of the feminist revolution “not simply the elimination of male privileges, but the gender differences” must come about. Other influential theorists of radical feminism are Catharine MacKinnon and Mary Daly .

Equality Feminism

“Equality” and “difference” are central categories in feminist discourse . Equality feminist theories are primarily critical of rule. They analyze the social reality of the sexes and examine the social construction methods of equality and inequality. In equality feminism (equality feminism or social feminism [see also social feminism of the 1920s ]) the representatives assume a fundamental equality of the sexes and justify the differences between the sexes mainly with social power structures and the socialization of people. This idea was first raised by Simone de Beauvoir in The Other Sex (1949), according to which women are viewed as “the other” and a social construct of men.

According to this theory, there is no such thing as “typically male” and “typically female”, but only behavioral differences between the sexes based on gender-specific socialization and the division of tasks. The aim of this feminist struggle for emancipation is the abolition of all gender-specific social injustices and differences in order to enable people to live according to their individual abilities and preferences, instead of according to socially prescribed gender roles . Well-known representatives of equality feminism include Elisabeth Badinter and, in German-speaking countries, Alice Schwarzer .

This thought was radicalized by some of the feminists grouped around the French magazine Nouvelles Questions Féministes (NQF). While for de Beauvoir anatomy was ultimately a given and part of the situation, they interpreted the biological gender itself as a construct with the purpose of marking the power relations between men and women.

Difference feminism

In difference feminism or cultural feminism, gender diversity is the determining category. The spectrum ranges from those who assume a fundamental essential difference between the sexes, which is usually derived from the biological difference (gender) or the difference resulting from culture and social processes, to those who question the essential nature of the Consider genders irrelevant and make the factual difference that shows up in everyday life the starting point for theories and political action.

Early theorists of difference feminism (around 1900) such as Jane Addams and Charlotte Perkins Gilman argued that the virtues of women are needed in politics and in order to resolve conflicts in society. For example, the assumption that “women are more sensitive and gentle than men” leads to the conclusion that with world domination by more pacifist women, there would be fewer wars and that women would ensure better child-rearing. A classic representative of feminist pacifism was Bertha von Suttner .

The French psychoanalyst and cultural theorist Luce Irigaray , whose starting point are the theories of Freud and Lacan , and the writer Hélène Cixous are among the most important contemporary feminist thinkers of difference . Her goal is to make visible what is special that distinguishes women from men. They are calling for a revolution in the symbolic order of patriarchy that will reevaluate the differences between the sexes. The Italian philosophers around Luisa Muraro , who have formed the group Diotima , also postulate a new symbolic order that is defined by the mother and other women . In Germany, for example, this approach is represented by Antje Schrupp .

The historian Kristina Schulz sums up the differences between equality feminism (social feminism) and difference feminism (cultural feminism) in the second women's movement in France and Germany as follows: "If one argued ... on the part of cultural feminism for a society that recognized the" other ", social feminism aimed at overcoming the "other". If representatives of cultural feminism sought to abolish gender hierarchies , social feminists advocate overcoming gender differences . "

In the more recent feminist theory debate, v. a. in France, the supposed pair of opposites “equality and difference feminism” is discussed as an invention or construction, e.g. B. by Françoise Collin and Geneviève Fraisse . They attribute the strong polarization to the fact that the representatives belong to certain disciplines. Equality feminists lack a theory of the subject , difference feminists lack a social theory .

Gynocentric feminism

The term was coined by the American political scientist Iris Marion Young ( Humanism, Gynocentrism and Feminist Politics , 1985). In the history of feminism, Young distinguishes humanistic feminism , which includes all liberal, socialist and radical currents and which was widespread in the 19th century as in the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, from gynocentric feminism . He criticizes the lack of appreciation of female subjectivity, which is expressed in the devaluation of female bodies, morality and language and is enshrined in the universal , supposedly gender-neutral individuality model of humanism . Against the background of this criticism, gynocentric feminism wants to establish a philosophy of the female experience. According to Young, for example, the American psychologist Carol Gilligan ( In a Different Voice , German: The Other Voice , 1982) developed a gynocentric approach, according to which the woman embodies a different morality than the man due to the experience of motherhood. From this basic assumption, she developed her “philosophy of care”: she contrasts the male ethic of justice with the female ethic of care. Gilligan broke through the dominant feminist discourse tradition until then, according to which the commitment to care was regarded as a medium of oppression of women.

Elisabeth Badinter criticized this approach as a new biologism and called it naturalistic feminism . The French psychoanalyst Antoinette Fouque, who founded the women's group Psychanalyse & Politique in the 1970s and made difference theory fertile for classical psychoanalysis ( Il ya deux sexe , 1995), went beyond Gilligan's differentiated views when she claimed that Women are morally superior to men because of their ability to conceive.

Spiritual feminism

In the years from 1970 onwards, numerous spiritual , esoteric or neo-pagan movements were shaped by feminism and sometimes also matriarchal ideas , which worship the “ great goddess ” in her three forms as girl, mother and wise old man. Some authors interpret this as a gynocentric approach. The historical witch hunt is interpreted under the aspect that it applied to all women. The persecution of witches destroyed gynecology , which is in the hands of women . Depending on the trend, witches are also seen as the last adherents of a religion of the Great Goddess . The simultaneous self-identification as a witch or magician is related to the attempt to acquire this knowledge again. Influential representatives of spiritual feminism are the American Starhawk ( The Spiral Dance. A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Goddess , 1979) and in Germany Luisa Francia and Ute Schiran . Starhawk's ideas influenced the ritual practice of spiritual feminism in Germany.

By Starhawk and other areas categorized Reclaiming tradition , a 1970 created in in California network, work in which women and men from spirituality with political responsibility to join, is American Goddess Movement (German: Goddess movement ) and in Wiccatum justified and integrates ecofeminist ideas.

Ecofeminism

In the course of the international environmental, peace and women's movements from the mid-1970s, eco-feminism emerged. He argues that there is a link between the oppression of women in patriarchy and the exploitation of nature. Well-known theorists include: Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva .

Psychoanalytically oriented feminism

In one of the classics of feminist literature, Sexual Politics , published in 1969, Kate Millett examines and criticizes Sigmund Freud's theories on the nature of women, among others . There she formulates the “theory of sexual politics”, which contrasts the common understanding of politics with politics of the first person .

Juliet Mitchell is an author who uses psychoanalytic categories to search for the causes of the oppression of women . She developed a “feminist interpretation” of Sigmund Freud's works and interprets psychoanalysis as a theoretical explanation of “the material reality of ideas in the historical context of human life” and thus sees Freudian theory as the psychological foundation of feminism.

To the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan then, however, criticizing him from a feminist perspective, to theorists like facing Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray other than that the pre-oedipal and vorsymbolischen to operations. In their theorizing, they focused on the physical and the infantile relationship with the mother. Lacan had worked out the patriarchal structure of language and the symbolic order, but at the same time also fixed it and thus continued a unisex - phallocentric - model of thought. According to Irigaray, there is no real sexual difference in patriarchal society; it is built on the mother's sacrifice. The aim must be - initially within the framework of a "strategic essentialism" - to develop a separate female subject position.

Socialist feminism

Socialist feminism is based on a fundamental equality of the sexes and is skeptical of theories of a natural gender difference. He sees the oppression of women caused by two interacting structures: capitalism and patriarchy . In the second women's movement, it organized itself hierarchically and, as a rule, based on a party, according to the Democratic Women's Initiative . Above all, he advocates the general social rights of women and sees these as a prerequisite or element for overcoming the capitalist system . He also raises the question of unpaid house - and reproductive work and their function for the system of capitalist production. Socialist or Marxist feminism is often associated with the labor movement.

In theorizing, socialist feminism falls back on the Marxist analysis, but below the class contradictions, the gender difference is assumed as the “ main contradiction ” and included in a “materialistic interpretation of history”. The partially resulting demand for the abolition of biological differences between the sexes is called "cybernetic feminism" (also: "cybernetic communism"). Shulamith Firestone and Marge Piercy demanded that genetic engineering should take over reproduction and that women should be freed from the biological necessity of childbirth .

Anarchist feminism

The influences between feminist positions and the history of anarchism have so far been little explored and are limited to a few outstanding people. For the beginnings of anarchism in the mid to late 19th century, for example, Virginie Barbet and André Léo combine anarchist and feminist positions. Louise Michel (1830–1905) was best known for her work during the Paris Commune . In the USA, the feminist Victoria Woodhull (1838–1927) represented anarchist positions within the First International . Emma Goldman (1869–1940) is considered an outstanding figure in American anarchism . She stands for a systematic connection between feminism and anarchism, which also characterized her private life. For her, personal and political freedom for women belonged together - a central idea of feminism in the second half of the 20th century. In 1906 she wrote in the anarchist journal Mother Earth : "Emancipation should enable women to be human in the truest sense of the word." Emma Goldmann relied on the "natural qualities of women", on "unlimited love" and feelings of motherhood. At the same time she fought for the revolution like Clara Zetkin, but was one of the first to criticize the Russian Revolution; she denounced slavery and stood up for civil liberties. While Goldman advocated violence as a political means, at least for a time, Clara Gertrud Wichmann (1885–1922) introduced the principle of non-violence into political discourse in Europe. During the Spanish Civil War , the feminist-anarchist women's organization Mujeres Libres was founded in 1936 . The Anarchafeminism is an embossed in the 1970s flow of radical feminism, which extends this anarchist elements to theory and practice.

Individual feminism

The United States has a tradition of unrestrained liberalism , which has civil liberty as the fundamental value. Individual feminism makes this claim for women. It is divided into the currents of classic liberal or libertarian feminism, which seeks to strengthen the individual rights of women, and egalitarian liberal feminism, which seeks the emancipation of women as individuals and emphasizes personal autonomy.

There are theoretical connections with anarchism or anarchafeminism . One of the most famous representatives is Wendy McElroy .

Deconstructivist Feminism / Post Feminism

Judith Butler , author of The Uneasiness of the Sexes , and other representatives of feminist deconstructivism and post-feminism build on de Beauvoir's equality feminism and go one step further: Both biological sex and gender are social constructs , therefore the gender must be rejected as a classification unit.

At the center of this theory is the difference between people, that is, assumed similarities and gender identities are "dissolved, deconstructed" - the differences between people of one sex are greater than the differences between the sexes. Instead, it assumes that there are as many identities as there are people. The bisexuality assumed in the previous approaches is also disputed from a deconstructivist point of view and replaced by polygenderism.

Post-feminism is closely related to a neoliberal worldview. Contemporary neoliberalism, which also extends to social spheres, understands the individual as an economic actor who acts rationally and in a self-regulated manner. According to an analysis by Rosalind Gill, this notion is ultimately reflected in the post-feminist notion of actively acting, freely making decisions and reinventing themselves, a notion that has supplanted the consideration of political, social or other external influences on the individual.

Feminist science disciplines

The editors of the Feminist Studies describe academic work as feminist if “the normative and empirical complexity of gender relations” is recognized and “given distortions due to interests and stereotypes” are reflected on on this basis. In many scientific disciplines since the end of the 20th century emerged feminist sections to the lack of women - and a gender perspective to within the disciplines explore :

- Feminist Approaches in Ethnology

- Feminist history

- Feminist communication and media studies

- Feminist criminology

- Feminist art history

- Feminist art studies

- Feminist Linguistics

- Feminist literary studies

- Feminist musicology

- Feminist Economy

- Feminist pedagogy

- Feminist Philosophy

- Feminist Psychology

- Feminist psychotherapy

- Feminist Law

- Feminist Sociology

- Feminist Theater Studies

- Feminist theology

Concept of state feminism

“State feminism” is not a feminist current. In political science , this term describes, on the one hand, attempts by states to enforce formal equality between women and men through reforms from above , such as in Turkey as part of the Kemalist modernization project in 1923, in the GDR or in Tunisia since the 1950s .

On the other hand, “state feminism” refers to the institutionalization of women's emancipation efforts in the modern state as well as a specific women's political strategy, which is described by the catchphrase march through the institutions . The Scandinavian countries and Australia are prototypes for this. The so-called state feminism in Finland, for example, where, among other things, the promotion of women within the party has a long tradition, effectively facilitated the political participation of women. Birgit Sauer comes in her study Engendering Democracy. State feminism in the age of the restructuring of statehood (2006) to the result: "[...] women [have] in the past thirty years relatively successfully democratized western liberal democracies from a women's perspective." This shows that not only the proportion of women in political decision-making bodies, but also the "substantive representation in terms of content could be decisively influenced in the sense of a women-friendly output". This development is largely due to the establishment of state institutions such as women's ministries, women's offices or equality officers, who act as mediators between women's groups and women's movements on the one hand and politics and administration on the other.

"The term 'state feminism' describes precisely this phenomenon [...], namely the emergence of state institutions for the equality of women and for the advancement of women."

effect

Feminism has contributed to improving social equality between women and men in Europe and the USA. Since the emergence of the first feminist ideas almost two centuries ago and the resulting women's movement, the situation of women has changed radically. Above all, the introduction of women's suffrage in most European countries at the beginning of the 20th century represented a turning point that considerably expanded the opportunities for women to participate in the political and social life of women. With the emergence of rigid family structures, especially in the second half of the 20th century, the models and lifestyles of many young women, who no longer matched traditional masculinity and traditional images of femininity, also changed. The legal recognition and public scandal of gender-based violence against women promoted broad, cross-gender awareness both against personal attacks on women and against subtle relationships of violence rooted in society. At the international level, based on the World Women's Conferences organized by the United Nations since 1975, women in the Third World have increasingly set up platforms and initiatives that are becoming more and more internationally networked and have attracted worldwide attention to the topic of “Women's Human Rights” excited.

Despite the improvement in many objective indicators of women's quality of life since the 1970s, representative surveys in the US and the EU show a decline in subjective satisfaction among women compared to men. Despite numerous approaches, this paradox has not yet found a satisfactory explanation. Feminism may have encouraged expectations that have not (yet) been met. Furthermore, the higher labor market participation could also have had negative effects, for example due to the difficulty of balancing family and work, although the total working hours of women and men have been falling equally since 1965. The general increase in sexual and family self-determination could also have led to a greater increase in satisfaction among men than among women.

With the arrival of the new millennium, the question of whether feminism is obsolete has increasingly been asked in the public debate. Today's women are able to “assert themselves with energy, discipline, self-confidence and courage in a society like ours.” As early as the 1990s, many young women tended to view feminism as boring and outdated. At the same time, however, new public, media-supported debates about feminism, gender and sexuality emerged, especially in the Nordic countries. The protest was primarily directed against the commercialized, stereotypical image of the idealized female body, mainly in the fashion world, against continued homophobia in society and against unequal educational opportunities. In Germany, a young generation of journalists is formulating the claim to a “new” feminism that clearly sets itself apart from conventional political feminism.

To what extent these currents are actually the beginning of a completely new feminist self-image or whether feminism of the last 40 years has only continued in a transformed form is still largely disagreed in the current scientific debate.

On the topicality of feminism, Nancy Fraser put it :

"It will not be time to speak of postfeminism until we can legitimately speak of postpatriarchy."

Controversy

Feminism has received criticism from many quarters since its inception. Since the term feminism summarizes various - sometimes contradicting - currents and over the years many writings have been published and many prominent representatives of feminism emerged, we can usually only speak of criticism of partial aspects of feminism.

Of women's rights activists from Asia, Africa, South America and the Arab region to US and European feminist organizations will always Eurocentrism accused: the specific needs of women from different cultural regions, particularly from developing countries, will no consideration, the Euro-centric discourse monopolizing the “women's rights issue” for the specific needs of women from the European-US-American cultural area.

In the early 1980s, when the feminist anti-pornography movement was confronted with the US, sex-positive feminism emerged . In Germany he is represented by Laura Méritt , who initiated PorYes , among others . Like Alice Schwarzer, for example, she rejects conventional porn and advocates alternative images to the offers of the porn industry.

Anti-feminism

Anti-feminism is an umbrella term for intellectual, social, political, religious and academic currents and social movements that oppose individual, several or all feminist concerns.

Often anti-feminism is also a general misogyny associated. So feminists and women's rights were - pejoratively in the 19th century bluestocking called - since the beginning of the women's movement often lack of attractiveness, unfemininity and unduly dominant behavior alleged. The reproaches here came from both men and women, who perceived the break in traditional role models as a problem, since to them the traditional distinction between the sexes seemed irrefutable. The breakout from the gender role is described by critics as a loss of traditional femininity . In earlier times in particular, large parts of the leading social classes fundamentally rejected equal rights for women. Philosophers, theologians, natural scientists, physicians and art historians argued well into the 20th century with the “natural” or “God-given” inferiority of women compared to men and thus justified their subordinate position in society. Until the 1920s, some questioned whether women were people at all (e.g. Max Funke ).

In 1900 a pamphlet by the neurologist Paul Julius Möbius appeared under the title On the physiological idiocy of women , in which the author tries to prove the physiological inferiority of women. According to Möbius, healthy and fertile women were necessarily stupid. Möbius' text was a famous anti-feminist attempt to establish psychological and behavioral norms for women.

An early anti-feminist was Ernest Belfort Bax (1854-1926), who, among other things, questioned women's suffrage.

From the 1970s an anti-feminist men's rights movement emerged in some Western countries . Some of these groups referred to themselves as masculists from the late 1980s , while others were referred to as such in studies. They argue that women in modern societies often enjoy more privileges than men, which is reflected in, among other things, a significantly higher life expectancy and preference for e.g. B. in education policy.

According to Susan Faludi , the anti-feminist backlash movement in the US was not sparked by the achievement of equality, but rather by the very possibility that women could achieve equality. Anti-feminism is a preventive attack that stops women long before the finish line.

See also

further reading

General introductions

- Regina Becker-Schmidt , Gudrun-Axeli Knapp: Feminist theories as an introduction . 5th, supplemented edition. Junius, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-88506-648-4 .

- Ute Gerhard : women's movement and feminism. A story since 1789 (= CH Beck Wissen ). CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-56263-1 .

- Sabine Hark (Hrsg.): Dis / Continuities: Feminist Theory (= Section Women's Research in the German Society for Sociology [Hrsg.]: Series of textbooks on sociological research on women and gender . Volume 3 ). Leske and Budrich, Opladen 2001, ISBN 3-8100-2897-5 .

- Barbara Holland-Cunz : The old new women's question (= Edition Suhrkamp: New social science library ). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-12335-1 .

- Margret Karsch: Feminism for those in a hurry . Construction Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-7466-2067-8 .

- Gudrun-Axeli Knapp : In conflict. Feminist theory in motion (= gender & society ). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-18267-4 .

- Ilse Lenz (Ed.): The new women's movement in Germany. Farewell to the small difference. Selected sources . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16764-0 .

- Nina Lykke : Feminist Studies. A Guide to Intersectional Theory, Methodology and Writing . Routledge, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-415-51658-7 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Karen Offen: "Liberty, Equality, and Justice for Women: The Theory and Practice of Feminism in Nineteenth-Century Europe". In: Renate Bridenthal, Claudia Koonz and Susan Stuard (eds.): Becoming Visible. Women in European History. 2nd edition, Boston et al. 1987, pp. 335-373.

- Bettina Schmitz : The third feminism. Paths of thought beyond gender boundaries . one-subject publishing house, Aachen 2007, ISBN 978-3-928089-45-6 .

Anthologies

- Yvonne Franke, Kati Mozygemba, Kathleen Pöge, Bettina Ritter, Dagmar Venohr (eds.): Feminisms today. Positions in theory and practice. Transcript Verlag 2014, Bielfeld, ISBN 978-3-8376-2673-5 .

- Rita Casale , Barbara Rendtorff (ed.): What comes after gender research? On the future of feminist theory formation. Transcript Verlag, Bielfeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-89942-748-6 .

- María Isabel Peña Aguado, Bettina Schmitz (eds.): Classics of modern feminism. ein-FACH-verlag, Aachen 2010, ISBN 978-3-928089-51-7 .

- Luise F. Pusch (Ed.): Feminism. Inspection of Men's Culture - A Handbook. Frankfurt am Main 1983 (= Edition Suhrkamp. Volume 1192).

- Bettina Roß: Migration, Gender and Citizenship. Perspectives for an anti-racist and feminist politics and political science. VS Verlag Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-8100-4078-9 .

- Alice Schwarzer (Ed.): You are not born a woman. 50 years after the “opposite sex”, women writers and politicians take stock: Where do women stand today? Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-462-02914-2 .

Classics of feminism and feminist philosophy (selection)

- Simone de Beauvoir : Le deuxième sexe (1949); German: The other sex (1951), (translated by Uli Aumüller and Grete Osterwald), 13th edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-499-22785-1 .

- Judith Butler : Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity . 1990, German: The Unease of the Sexes (1991); Suhrkamp, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-518-12433-1 .

- Hedwig Dohm : The anti-feminists. A Book of Defense (1902); Text on project Gutenberg ;

- Shulamith Firestone : The Dialectic of Sex (1970); German: Women's Liberation and Sexual Revolution (1975). Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-596-24701-2 .

- Emma Goldman : Anarchism and Other Essays (1911), therein essays on the women's question; German excerpts: The tragic thing about the emancipation of women . K. Kramer Verlag, Berlin 1987; full edition: Anarchism & Other Essays. Unrast Verlag, Münster 2013, ISBN 978-3-89771-920-0 .

- Olympe de Gouges : Declaration of the droits de la femme et de la citoyenne (1791); German: Declaration of the rights of women and citizens .

- Luce Irigaray : Speculum de l'autre femme (1974); German: Speculum: mirror of the opposite sex . Suhrkamp 1980, ISBN 3-518-10946-4 .

- Kate Millett : Sexual Politics (1959); German: Sexus and domination: the tyranny of men in our society (1971). Ex libris, 1971

- Carole Pateman : The Sexual Contract (1988); German: The gender contract , publisher for social criticism, Graz 1994, ISBN 3-85115-194-1 .

- Alice Schwarzer : The small difference and its big consequences. Women about themselves - the beginning of a liberation , 1st edition. S. Fischer , Frankfurt a. M. 1975, ISBN 3-10-076301-7 .

- Barbara Seaman : Free and Female. New York 1972.

- Mary Wollstonecraft : A vindication of the rights of woman (1792); German: Defense of the rights of women . Edition: Mary Wollstonecraft: A Vindication of the Rights of Man and A Vindication of the Rights of Women . S. Tomaselli (Ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995

- Virginia Woolf : A Room of One's Own (1929); German A room for yourself (1978), Reclam, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-15-018887-3 or A room of your own . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-596-14939-8 .

History of literature and ideas

- Peggy Antrobus: The Global Women's Movement - Origins, Issues and Strategies . Zed Books, London 2004.

- Donna Landry, Gerald McLean: Materialist Feminisms . Blackwell, Cambridge 1993.

- Gerda Lerner : The emergence of feminist consciousness. From the Middle Ages to the First Women's Movement. Dtv, 1998, ISBN 3-423-30642-4 .

- Sheila Rowbotham : A Century of Women. The History of Women in Britain and the US . Penguin, London 1999.

- Lieselotte Steinbrügge : The moral sex. Theories and literary drafts on the nature of women in the French Enlightenment. 2nd Edition. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel; Metzler, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-476-00834-7 .

- Michaela Karl: The history of the women's movement , Reclam, Ditzingen 2020, ISBN 978-3150196571

Political theory

- Linda Scott: The female capital , Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2020, ISBN 978-3446267800

- Lynn S. Chancer: After the Rise and Stall of American Feminism: Taking Back a Revolution. Stanford University Press, Stanford 2019, ISBN 978-1-5036-0743-9 .

- Carole Pateman (Ed.): Feminist Challenges. Social and Political Theory , Routledge Chapman & Hall 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-63675-9 .

- Marion Löffler: Feminist State Theories. An introduction . Campus Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-593-39530-2 .

- Angela McRobbie: Top Girls. Feminism and the Rise of the Neoliberal Gender Regime. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-16272-0 .

- Gundula Ludwig, Birgit Sauer , Stefanie Wöhl (eds.): State and gender. Foundations and current challenges of feminist state theory . Nomos Verlag, Baden-Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-8329-5034-7 .

- Melanie Groß, Gabriele Winker (ed.): Queer, feminist criticism of neoliberal conditions . Unrast, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-89771-302-4 .

- Seyla Benhabib : The Controversy About Difference: Feminism and Postmodernism in the Present. Fischer TB 1994, ISBN 3-596-11810-7 .

Magazines

- United States

- Ms. (magazine) , since 1972

- Feminist Studies , since 1972

- Gender & Society , peer-reviewed , since 1987

- Hypatia (magazine) , feminist philosophy

- Germany

- Trade journals

- Feminist studies , peer reviewed , since 1982

- Femina Politica - journal for feminist political science (received the Margherita von Brentano Prize in 2000 )

- Streit - feminist legal journal , since 1983

- Schlangenbrut - magazine for women interested in feminism and religion (since 1983)

- Women and Film , feminist film magazine, since 1974

- Querelles , peer-reviewed, since 1996

- Gender , peer-reviewed, since 2009

discontinued: Contributions to feminist theory and practice (1978–2008; the oldest and largest magazine of the autonomous women's movement)

- Popular magazines

- Missy Magazine , since 2008

- We Women - The Feminist Journal , since 1982

- EMMA - The political magazine for women , since 1977

- Clio - Journal for Women's Health, Ed. Feminist Women's Health Center Berlin

discontinued: lesbian press (1975–1982); COURAGE - current women's newspaper (1976–1984), IHRSINN - a radical feminist lesbian magazine , (1990–2004)

- Austria

- Trade journal

- L'Homme. European Journal of Feminist History , peer-reviewed, since 1990

- Labyrinth - International Journal for Philosophy, Feminist Theory an Cultural Hermeneutics, ISSN 1561-8927

- Popular magazines

- dieStandard.at , only available online ( diestandard.at ), since 2000

- An.schlag - the feminist magazine , since 1983

- fiber. material for feminism and pop culture , since 2002

- Switzerland

- FAMA - The Feminist Theological Journal (since 1994)

Web links

- Feminism. In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Scientific articles on topics, theories and philosophy of feminism.

- Jewish Women and the Feminist Revolution. Feminist biographies and timeline on the history of the U.S. women's movement since 1963.

- Luise Pusch (ed.): Fembio. Women biographies.

- The Feminist Theory website. Bibliographies worldwide.

- Political science literature on feminism - theory and practice. In: Annotated Bibliography of Political Science .

- Ilse Lenz: What is feminism? Gunda Werner Institute (Feminism and Gender Democracy) of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, article from May 25, 2018

Notes and individual references

- ↑ Feminism. In: Digital dictionary of the German language .

- ↑ Ilse Lenz: What is feminism? In: gwi-boell.de. May 25, 2018, accessed August 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Sally Haslanger, Nancy Tuana, Peg O'Connor: Topics in Feminism, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Zalta Edward N. (ed.)

- ^ Claudia Opitz : Gender history . Frankfurt a. M. 2010, ISBN 978-3-593-39183-0 , pp. 124 .

- ^ Ute Gerhard : Women's Movement and Feminism. A story since 1789. Beck-Verlag, Munich 2009, p. 6 f.

- ↑ Cf. Barbara Holland-Cunz : The promise of equality. A history of political ideas of modern feminism. In: Barbara Holland-Cunz: The old new women's question. Edition Suhrkamp, 2003, ISBN 3-518-12335-1 , p. 17 f.

- ↑ Feminism. In: Digital dictionary of the German language. Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, accessed on November 30, 2020 .

- ↑ www.spektrum.de .

- ↑ Emile Laurent: The hybrid formations: gynecomastia, feminism, hermaphrodism. 1896, Retrieved November 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Emile Laurent: Les bisexués. Retrieved 1894 .

- ↑ Matthias Heine: Since when has "geil" nothing to do with sex? 100 German words and their amazing careers . Hamburg 2016, p. 55 f .

- ↑ a b c d Karen Offen: On the French origin of the words feminism and feminist. June 1988, accessed August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexandre Dumas (1824–1895): Man and Woman. 1872, p. 93 ff. , Accessed on August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Emile de Girardin: L'HOMME ET LA FEMME - L'HOMME SUZERAIN, LA FEMME VASSALE. 1872, pp. 62 f. , Accessed on August 24, 2020 .

- ^ Charles Fourier: The theory of the four movements and the general provisions. (1808), Vienna and Frankfurt am Main 1966, p. 190.

- ↑ a b Karen Offen: European Feminisms, 1700–1950: A Political History. Stanford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-8047-3420-8 , pp. 19 ff ( limited preview in Google book search); dies .: On the French origin of the words feminism and feminist , Feminist Issues, June 1988, Volume 8, Issue 2, pp 45-51. doi: 10.1007 / BF02685596

- ^ Ute Gerhard: Women's Movement and Feminism. A story since 1798 , Verlag CH Beck, second edition Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-56263-1 , p. 67.

- ^ A b Christiane Streubel: Radical Nationalists. Agitation and programs of right-wing women in the Weimar Republic. (Dissertation) Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 2006 (= series history and gender. Volume 55), ISBN 3-593-38210-5 , p. 65 f.

- ↑ Google Ngram Viewer: Feminism, women's emancipation

- ↑ Guest lecture at the Technical University of Vienna, March 22, 2004.

- ↑ Ute Gerhard: Women's Movement and Feminism: A History since 1789 . Munich 2012, p. 8 .

- ↑ Terms “women's movement”, “women's question”, “women's rights”, “feminism” in books on Google Books from 1860 to 2008. In: Google Books Ngram Viewer. Retrieved December 5, 2017 .