Islam: Difference between revisions

→Five Pillars of Islam: - stagger this pictures for variety - revert if you disagree |

move "Dome of the Rock" picture to appropriate location and expand caption |

||

| Line 259: | Line 259: | ||

===Others=== |

===Others=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the [[Kharijites]]. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites, which was itself divided into numerous sub-sects, is the [[Ibadi]] sect. Ibadism is distinguished from Shi'ism by its belief that the leader should be chosen solely on the basis of his faith and not on the basis of descent, and from the Sunni in its rejection of [[Uthman]] and [[Ali]] and strong emphasis on the need to depose unjust rulers. Ibadi Islam is noted for its strictness, but, unlike the Kharijites proper, Ibadis do not regard major sins as automatically rendering a Muslim an unbeliever. Most Ibadi Muslims live in [[Oman]].<ref name="JAW"> John Alden Williams(1994), p.173</ref><ref> Encyclopedia of Islam, al-Ibāḍiyya</ref> |

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the [[Kharijites]]. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites, which was itself divided into numerous sub-sects, is the [[Ibadi]] sect. Ibadism is distinguished from Shi'ism by its belief that the leader should be chosen solely on the basis of his faith and not on the basis of descent, and from the Sunni in its rejection of [[Uthman]] and [[Ali]] and strong emphasis on the need to depose unjust rulers. Ibadi Islam is noted for its strictness, but, unlike the Kharijites proper, Ibadis do not regard major sins as automatically rendering a Muslim an unbeliever. Most Ibadi Muslims live in [[Oman]].<ref name="JAW"> John Alden Williams(1994), p.173</ref><ref> Encyclopedia of Islam, al-Ibāḍiyya</ref> |

||

== Islam and other religions == |

== Islam and other religions == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{main|Islam and other religions}} |

{{main|Islam and other religions}} |

||

Revision as of 19:04, 17 April 2007

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Islam (Arabic: ) is a monotheistic religion originating with the teachings of Muhammad, a 7th century Arab religious and political figure. It is the second-largest religion in the world today, with an estimated 1.4 billion adherents, spread across the globe, known as Muslims.[1] The word Islam means "submission", referring to the total surrender of one's self to God (Arabic: [[Allah|الله, Allāh]]), and a Muslim is "one who submits (to God)".[2]

Muslims believe that God revealed the Qur'an to Muhammad and that Muhammad is God's final prophet. The Qur'an and the traditions of Muhammad in the Sunnah are regarded as the fundamental sources of Islam.[3][4] Muslims do not regard Muhammad as the founder of a new religion, but as the restorer of the original monotheistic faith of Adam, Abraham, Jesus, Moses, and other prophets. They hold that part of the messages of these prophets became distorted over time either in interpretation, in text, or both.[5][6][7] Like Judaism, and Christianity, Islam is an Abrahamic religion.[8]

Today, Muslims may be found throughout the world, particularly in the Middle East and North, West and East Africa. Some of the most populous majority-Muslim countries are in South and Southeast Asia. Other large communities can be found in Central Asia, China, and Russia. Only about 20 percent of Muslims originate from Arab countries.[9] Islam is the second largest religion after Christianity in many European countries, such as France, which has the largest Muslim population in Western Europe and the United Kingdom.[10][11]

Etymology and meaning

The word "islām" is "the infinitive of the fourth form of the Arabic triconsonantal root s-l-m meaning 'to submit,' 'to surrender'."[12] Thus Islam effectively means submission to God. Followers of Islam are expected to submit to God by worshiping him, following his commands and avoiding polytheism.[2] The word "islam" is also based upon the Arabic word for peace (salam) and could be applicible to the religion of Islam if it is taken to mean that "true peace resides in submission to God." [13]

The word 'islām takes a number of different meanings in the Qur'an. In some verses (ayat), the quality of Islam as an internal conviction is stressed, for example: "Whomsoever God desires to guide, He expands his breast to Islam."[14][2] Other verses establish the connection between islām and dīn (usually translated as "religion"), and assert that only the surrender of one's self to God can render unto him the worship which is his due: "Today, I have perfected your religion (dīn) for you; I have completed My blessing upon you; I have approved Islam for your religion."[15] The final category of verses describe Islam as an action (of returning to God), more than simply a verbal affirmation.[16][2]

Beliefs

Muslims believe that God revealed his final message to humanity through the Islamic prophet Muhammad via the angel Gabriel.[17] They consider Muhammad to have been God's final prophet, the "Seal of the Prophets", and the Qur'an to be the revelations he received in his 23 years of preaching.[18] Muslims hold that all of God's messengers since Adam preached the message of Islam — submission to the will of the one God. To Muslims, Islam is the eternal religion, described in the Qur'an as "the primordial nature upon which God created mankind".[19][20] Furthermore, the Qur'an states that the proper name Muslim was given by Abraham.[21][20]

As a historical phenomenon, however, Islam was originated in Arabia in early 7th century.[20] Islamic texts depict Judaism and Christianity as prophetic successor traditions to the teachings of Abraham. The Qur'an calls Jews and Christians "People of the Book", and distinguishes them from polytheists. However, Muslims believe that parts of the previously revealed scriptures, the Tawrat (Torah) and the Injil (Gospels), had become distorted as indicated in the Qur'an — either in interpretation, in text, or both.[22]

Islamic belief has six main components — belief in God; his revelations; his angels; his messengers; the "Day of Judgement"; and the divine decree.[23][24]

God

The fundamental concept in Islam is the oneness of God (tawhīd): monotheism which is simple and uncompounded, not composed or made up of parts.[25] The oneness of God is the first of Islam's five pillars, expressed by the Shahadah (testification). By declaring the Shahadah, a Muslim attests to the belief that there are no gods but God, and that Muhammad is God's messenger.[26]

In Arabic, God is called Allāh. Etymologically, this name is thought to be derived from a contraction of the Arabic words al- (the) and Template:ArabDIN (deity, masculine form) — Template:ArabDIN meaning "the God".[27] The word Allāh is also used by Arab speaking Christian and Jewish people to refer to God.[28] According to F. E. Peters: "The Qur'an insists, Muslims believe, and historians affirm that Muhammad and his followers worship the same God as the Jews ([Quran 29:46]). The Quran's Allah is the same Creator God who covenanted with Abraham."[29] However, Muslims reject the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, seeing it as akin to polytheism. God is described in a chapter (sura) of the Qu'ran as: "...God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him".[30]

Qur'an

The Qur'an is considered by Muslims to be the literal word of God, and is the central religious text of Islam. It has also been called, in English, the Koran and, archaically, the Alcoran. The word Qur'an means "recitation".[31] Although the Qur'an is often referred to as a "book", when Muslims speak in the abstract about "the Qur'an", they usually mean the scripture as recited in Arabic rather than the printed work or any translation of it.[32] Muslims believe that the verses of the Qur'an were revealed to Muhammad by God through the Angel Gabriel on numerous occasions between the years 610 and his death on July 6 632. Modern Western academics generally hold that the Qur'an of today is not very different from the words Muslims believe to have been revealed to Muhammad, as the search for other variants has not yielded any differences of great significance.[33] The Qur'an occupies a status of primacy in Islamic jurisprudence,[34] and Muslims consider it a definitive source of guidance in to live in accordance to the will of God.[31] To interpret the Qu'ran, Muslims use a form of exegesis known as tafsir.[35][34]

Most Muslims treat paper copies of the Qur'an with veneration, ritually washing before reading the Qur'an. [36] Worn out Qur'ans are not discarded as wastepaper, but are buried or burnt. [37] Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Qur'an in the original Arabic, usually at least the verses needed to perform the prayers. Those who have memorized the entire Qur'an earn the right to the title of Hafiz.[38] [39]

Muslims believe that the Qur'an is perfect only as revealed in the original Arabic. Translations, they maintain, are the result of human effort, and are necessarily deficient. This deficiency arises from differences in human languages, the human fallibility of translators, and not least because the inspired style found in the original would be lost. Translations are therefore regarded only as commentaries on the Qur'an, or "interpretations of its meaning", not as the Qur'an itself. Almost all modern, printed versions of the Qur'an are parallel text ones, with a vernacular translation facing the original Arabic text.[31]

Muhammad

Muhammad (c. 570 – July 6 632), (also Mohammed, Mohamet, and other variants), was an Arab religious and political leader who propagated the religion of Islam. Muslims consider him the greatest prophet of God, and the last recipient of divine revelation. He is viewed not as the founder of a new religion, but as the last in a series of prophets, the restorer of the original monotheistic faith of Adam, Abraham and others which had become corrupted.[40][7] For the last 23 years of his life, beginning at age 40, Muhammad reported receiving revelations from God. The content of these revelations, known as the Qur'an, was memorized and recorded by his followers.[41]

During this time, Muhammad preached to the people of Mecca (which included his relatives and tribal associates), imploring them to abandon polytheism. Although some people converted to Islam, Muhammad and his followers were subsequently persecuted by the leading Meccan authorities. After 13 years of preaching in Mecca, Muhammad and the Muslims performed the hijra (emigration) to the city of Medina. There, with the Medinan converts (Ansar) and the Meccan migrants (Muhajirun), Muhammad soon established his political and religious authority. By 629, he was powerful enough to return to Mecca and assert control in the bloodless Conquest of Mecca.

By the time of his death in 632, Muhammad had succeeded in bringing the Arabian peninsula under Islamic rule. Despite his exalted status in Muslim thought, Muslims believe that Muhammad was merely human.[42][43]

Sunnah

Sunnah literally means "trodden path" and it refers in common usage to the normative example of Muhammad. This example is preserved in traditions known as hadith ("reports"), which recount his words, his actions, his response to the words and actions of others, and his personal characteristics.[44] By the time of the classical Muslim jurist, ash-Shafi'i (d. 820), the Sunnah had come to play an significant role in Islamic law, and Muslims were encouraged to emulate Muhammad's actions in their daily lives. The Sunnah also became a key exponent in clarifying understanding of the Qur'an.[45] The authentic hadith are considered by Muslims to be an authoritative source of revelation, second only to the Qur'an, because they represent divine guidance as implemented by Muhammad.[46]

Angels

Belief in angels is central to the religion of Islam, beginning with the belief that the Qur'an was dictated to Muhammad by the chief of all angels, Gabriel. They are seen as the ministers of God, and in some cases the agents of revelation. According to Islamic belief, angels were created from light, and do not possess free will.[47] They are completely devoted to the worship of God and are tasked by him with certain duties, such as recording every human being's actions, placing a soul in a newborn child, maintaining aspects of the Earth's environment, and taking the soul at the time of death. Angels are described in the Qur'an as "messengers with wings — two, or three, or four (pairs): He [God] adds to Creation as He pleases..."[48][49] Angels sometimes but not usually assume human form, and can intercede on man's behalf.[50][51][52]

Resurrection and judgment

A fundamental tenet of Islam is belief in the "Day of Resurrection", yawm al-Qiyāmah (also known as yawm ad-dīn, "Day of Judgment" and as-sā`a, "the Last Hour"). The trials and tribulations preceding and during Qiyāmah are described in the Qur'an and the hadith, as well as in the commentaries of Islamic scholars such as al-Ghazali, Ibn Kathir, and al-Bukhari. Muslims believe that God will hold every human, Muslim and non-Muslim, accountable for his or her deeds at a preordained time unknown to man.[53] Traditions say Muhammad will be the first to be brought back to life.[54] The Qur'an emphasizes Bodily resurrection, a sharp break from the pre-Islamic Arabian understanding of death (although certain Islamic philosophers like Ibn Sina have interpreted the relevant verses symbolically).[55][56] Resurrection will be followed by the gathering of mankind, culminating in their judgment by God.[57]

The Qur'an states that some sins can condemn someone to hell. These include lying, dishonesty, corruption, ignoring God or God's revelations, denying the resurrection, refusing to feed the poor, indulging in opulence and ostentation, and oppressing or economically exploiting others.[58] Muslims view paradise as a place of joy and bliss,[59] but despite the Qur'an's descriptions of the physical pleasures to come, there are clear references to an even greater joy — acceptance by God (ridwan) (see [Quran 9:72]).[60] There is also a strong mystical tradition in Islam that places these heavenly delights in the context of the ecstatic awareness of God.[61][clarification needed]

Divine decree

Another fundamental tenet of Islam is the belief in divine preordainment (al-qadaa wa'l-qadr), meaning that God has full knowledge and decree over all that occurs. This is explained by Qur'anic verses such as "Say: 'Nothing will happen to us except what Allah has decreed for us: He is our protector'..."[62] Muslims believe that nothing in the world can happen, good or evil, unless it has been preordained and permitted by God. Man possesses free will in the sense that he has the faculty to choose between right and wrong, and thus retains responsibility over his actions. Muslims also believe that although God has decreed all things, the evils and calamities that are decreed are done so as a trial, or because they may lead to a later benefit not yet apparent due to mankind's lack of comprehension. Therefore, divine preordainment does not suggest absence of God's indignation against evil and disbelief.[63][64] According to Islamic tradition, all that has been decreed by God is written in al-Lawh al-Mahfuz, the "Preserved Tablet".[63]

Five Pillars of Islam

The Five Pillars of Islam is the term given to the five core aspects of Islam, as understood by most Muslims. Shi'a Muslims accept the Five Pillars, but also add several other practices to form the "Practices of the Religion".

Shahadah

The basic creed or tenet of Islam is found in the shahādatān ("twin testimonies"): Template:ArabDIN, or "I testify that there is none worthy of worship except God and I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of God."[65] As the most important pillar, this testament is a foundation for all other beliefs and practices in Islam. Ideally, it is the first words a newborn will hear, and children are taught to recite and understand the shahadah as soon as they are able to understand it. Muslims must repeat the shahadah in prayer, and non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.[66]

Salah

The second pillar of Islam is salah, the requirement to pray five times a day at fixed times.[67] Each salah is performed facing towards the Kaaba in Mecca. Salah is intended to focus the mind on God; it is seen as a personal communication with God, expressing gratitude and worship. According to the Qur'an, the benefit of prayer "restrains [one] from shameful and evil deeds".[67][68] Salah is compulsory but some flexibility in the specifics is allowed depending on the circumstances.[69] For example in the case of sickness or lack of space, a worshiper can offer salah while sitting, or even lying down, and the prayer can be shortened when traveling.[69]

The salah must be performed in the Arabic language to the best of each worshiper's ability, although any extra prayers (du'a) said afterwards need not be in Arabic. The lines of prayer are to be recited by heart (although beginners may use written aids), and the worshiper's body and clothing, as well as the place of prayer, must be cleansed.[69] All prayers should be conducted within the prescribed time period (waqt) and with the appropriate number of units (raka'ah). While the prayers may be made at any point within the waqt, it is considered best to begin them as soon as possible after the call to prayer is heard.[70]

Zakat

Zakat, or alms-giving, is the practice of charitable giving by Muslims based on accumulated wealth, and is obligatory for all who are able to do so. It is considered to be a personal responsibility for Muslims to ease economic hardship for others and eliminate inequality.[71] Zakat consists of spending a fixed portion of one's wealth for the benefit of the poor or needy, including slaves, debtors, travelers, and others. A Muslim may also donate more as an act of voluntary charity (sadaqah), in order to achieve additional divine reward.[72]

There are two main types of zakat. First, there is the zakat on traffic, which is a fixed amount based on the cost of food that is paid during the month of Ramadan by the head of a family for himself and his dependents. Second, there is the zakat on wealth, which covers money made in business, savings, income, and so on.[73][74][75] In current usage zakat is treated as a 2.5% levy on most valuables and savings held for a full lunar year, as long as the total value is more than a basic minimum known as nisab (3 ounces or 87.48 g of gold). As of 16 October 2006, nisab is approximately US $1,750 or an equivalent amount in any other currency.[76]

Sawm

Three types of fasting (Sawm) are recognized by the Qur'an: Ritual fasting ([Quran 2:183]), fasting as compensation or repentance ([Quran 2:196]), and ascetic fasting ([Quran 33:35]).[77]

Ritual fasting is an obligatory act during the month of Ramadan.[78] Muslims must abstain from food, drink, and sexual intercourse from dawn to dusk during this month, and are to be especially mindful of other sins.[78] The fast is meant to allow Muslims to seek nearness to God, to express their gratitude to and dependence on him, to atone for their past sins, and to remind them of the needy.[79] During Ramadan, Muslims are also expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam by refraining from violence, anger, envy, greed, lust, harsh language, and gossip; in other words, they are expected to try to get along with each other better than normal. In addition, all obscene and irreligious sights and sounds are to be avoided.[80]

Fasting during Ramadan is not obligatory for several groups for whom it would be excessively problematic. These include pre-pubescent children, those with a medical condition such as diabetes, elderly people, and pregnant or breastfeeding women. Observing fasts is not allowed for menstruating women. Other individuals for whom it is considered acceptable not to fast are those in combat and travelers who intended to spend fewer than five days away from home. Missing fasts usually must be made up soon afterwards, although the exact requirements vary according to circumstance.[81][82][83][84]

Hajj

The Hajj is a pilgrimage that occurs during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the city of Mecca. Every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so is obliged to make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in his or her lifetime.[85] When the pilgrim is around ten kilometers from Mecca, he must dress in Ihram clothing, which consists of two white sheets.[86] Rituals of the Hajj include walking seven times around the Kaaba, touching the Black Stone, running seven times between Mount Safa and Mount Marwah, and symbolically stoning the Devil in Mina, among others.[86]

The pilgrim, or the hajji, is honored in his or her community. For some, this is an incentive to perform the Hajj. Islamic teachers say that the Hajj should be an expression of devotion to God, not a means to gain social standing. The believer should be self-aware and examine his or her intentions in performing the pilgrimage. This should lead to constant striving for self-improvement.[87]

Islamic law

The Sharia (literally: "the path leading to the watering place") is Islamic law, determined by traditional Islamic scholarship.[88] In Islam, Sharia is viewed as the expression of the divine will; the total and unqualified submission to God's will is considered to be the fundamental tenet of Islam. Sharia "constitutes a system of duties that are incumbent upon a Muslim by virtue of his religious belief".[88]

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from broad topics of governance and foreign relations all the way down to issues of daily living.[89] Islamic laws that are covered expressly in the Qur'an are referred to as hudud laws. They include the five crimes of theft, highway robbery, intoxication, adultery and falsely accusing another of adultery, each of which has a prescribed hadd punishment that cannot be forgone or mitigated.[90] The Qur'an and Sunnah also detail laws of inheritance, marriage, and restitution for injuries and murder, as well as rules for fasting, charity, and prayer. However, the prescriptions and prohibitions may be broad, so their application in practice varies. Islamic scholars, the ulema, have elaborated systems of law on the basis of these broad rules, supplemented by the hadith, which report how Muhammad and his companions interpreted them.[91]

Fiqh, or "jurisprudence", is defined in Islamic thought as the knowledge of the practical rules of the religion. The jurist Ibn Khaldun, further describes this as "Knowledge of the rules of God which concern the actions of persons who own themselves bound to obey the law respecting what is required (wajib), forbidden (mazhr), recommended (mandūb), disapproved (makruh) or merely permitted (mubah)."[92][citation needed] The method Islamic jurists use to derive rulings is known as usul al-fiqh ("legal theory", or "principles of jurisprudence"). According to Islamic legal theory, law has four fundamental roots, which are given precedence in this order: the Qur'an, the Sunnah (actions and sayings of Muhammad), the consensus of the Muslim jurists (ijma), and analogical reasoning (qiyas).[93]

The formative period of Islamic jurisprudence stretches back to the time of the early Muslim communities. In this period, jurists were more concerned with pragmatic issues of authority and teaching than with theory.[94] Progress in theory happened with the coming of the early Muslim jurist ash-Shafi'i, who codified the basic principles of Islamic jurisprudence in his book ar-Risālah. The book details the four aforementioned roots of law while specifying that the primary Islamic texts (the Qur'an and the hadith) be understood according to objective rules of interpretation derived from scientific study of the Arabic language.[95]

Community

Mosques

A mosque is a place of worship for Muslims. Muslims often refer to the mosque by its Arabic name, masjid. The word "mosque" in English refers to all types of buildings dedicated to Islamic worship, although there is a distinction in Arabic between the smaller, privately owned mosque and the larger, "collective" mosque (masjid jami), which has more community and social activities and amenities. The primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer. Nevertheless, mosques are also important to the Muslim community as meeting place and a place of study.[96] They have evolved significantly from the open-air spaces that were the Quba Mosque and Masjid al-Nabawi in the seventh century. Today, most mosques have elaborate domes, minarets, and prayer halls, demonstrating Islamic architecture.

Etiquette

There are numerous practices which fall into the category of Adab, or Islamic etiquette. This includes saying bismillah ("in the name of God") before meals, using only the right hand for eating and drinking, greeting others with "as-salamu `alaykum" ("peace be unto you"), and saying Alhamdulillah ("praise be to God") when sneezing, among others.[97][98] Hygienic practices include clipping the mustache, shaving the pubic and underarm hair, cutting nails, and cleaning the nostrils and the mouth. Islamic etiquette also prescribes specific ways of cleaning the body after elimination, and requires abstention from sexual relations during menstruation and the puerperal discharge. Furthermore, Muslims are also required to perform a ceremonial bath (ghusl) following menstruation, childbirth, or sexual intercourse. Male offspring are also circumcised, in accordance with Islamic practice.[99][98] Islamic burial rituals include the funeral prayer of the bathed and enshrouded dead body, and burial in a grave.[100][98]

Dietary laws

Muslims, like Jews, are restricted in their diet. Prohibited foods include pig products, blood, carrion,[101] and alcohol.[102] Excepting fish, all consumed meat must come from a herbivorous animal slaughtered in the name of God by a Muslim, Jew, or Christian. Food permissible for Muslims is known as halal food.

Islamic calendar

The formal beginning of the Muslim era was chosen to be the Hijra (the migration from Mecca to Medina of Muhammad and his followers) because it was regarded as a turning point in the fortunes of Muhammad's movement.[103] Reportedly it was Caliph Umar who chose this incident to mark the year 1 AH (Anno Hegira) of the Islamic calendar,[104] corresponding to 622 CE.[103] It is a lunar calendar,[103] "with nineteen ordinary years of 354 days and eleven leap years of 355 days in a thirty-year cycle".[105] It is synchronized only with lunations and not with the solar year. Therefore, Islamic dates cannot be converted to CE/AD dates simply by adding 622 years.[105]

Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar. The most important festivals in the Islamic calendar are Eid Al-Fitr (Arabic: عيد الفطر) on the 1st of Shawwal, marking the end of the fasting month Ramadan, and Eid Al-Adha (Arabic: عيد الأضحى) on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah, coinciding with the pilgrimage to Mecca.[106][98]

Jihad

Jihad is literally struggle in the way of God and is sometimes referred to as the sixth pillar of Islam, although it occupies no official status as such.[107] Within the realms of Islamic jurisprudence, jihad usually refers to military exertion against non-Muslim combatants.[108][109] In broader usage and interpretation, the term has accrued both violent and non-violent meanings. It can refer to striving to live a moral and virtuous life, to spreading and defending Islam, and to fighting injustice and oppression, among other usages.[110]

The primary aim of jihad is not the conversion of non-Muslims to Islam by force, but rather the expansion and defense of the Islamic state.[109][111] Muslim scholars condemned secular wars as an evil rooted in humanity's vengeful nature.[112] In the classical manuals of Islamic jurisprudence, the rules associated with armed warfare are covered at great length.[109] Such rules include not killing women, children and non-combatants, as well as not damaging cultivated or residential areas.[113] More recently, modern Muslims have tried to re-interpret the Islamic sources, stressing that jihad is essentially defensive warfare aimed at protecting Muslims and Islam.[109] Although some Islamic scholars disagree about how jihad should be pursued, there is consensus among them that the concept of jihad will always include armed struggle against persecution and oppression.[114] Some Muslims believe that Muhammad regarded the inner struggle for faith a "Greater Jihad" than even fighting by force in the way of God.[115]

History

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled History of Islam. (discuss) |

Early years and the Rashidun caliphate

Islam began in Arabia in the 7th century under the leadership of Muhammad, who united the many tribes of Arabia under Islamic law. With Muhammad's death in 632, there was a moment of confusion about who would succeed to leadership of the Muslim community. With a dispute flaring between the Medinese Ansar and the Meccan Muhajirun as to who would undertake this task, Umar ibn al-Khattab, a prominent companion of Muhammad, nominated Abu Bakr: Muhammad's intimate friend and collaborator.[116][117] Others added their support and Abu Bakr was made the first caliph, literally "successor", leader of the community of Islam.

Abu Bakr's immediate task was to avenge the recent defeat by Byzantine (also known as Eastern Roman Empire) forces, although a more potent threat soon surfaced in the form of a number of Arab tribes who were in revolt after having learned of the death of Muhammad. Some of these tribes refused to pay the Zakat tax to the new caliph, whilst other tribes touted individuals claiming to be prophets. Abu Bakr swiftly declared war upon, and subdued these tribes, in the episode known as the Ridda wars, or "Wars of Apostasy".[116]

Abu Bakr's death in 634 resulted in the succession of Umar as the caliph, and after him, Uthman ibn al-Affan, and then Ali ibn Abi Talib. These four are known as the "khulafa rashidūn" ("Rightly Guided Caliphs").[118] Under them, the territory under Muslim rule expanded greatly. The decades of warring between the neighboring Persian and Byzantine empires had rendered both sides weakened and exhausted.[2] Not only that, it had also caused them to underestimate the strength of the growing new power, and the Arabs' superior military horsemanship. This, coupled with the precipitation of internal strife within Byzantium and its exposure to a string of barbarian invasions, made conditions extremely favorable for the Muslims. Exploitation of these weaknesses enabled the Muslims to conquer the lands of Syria and Palestine (634—640), Egypt (639—642); and, towards the east, the lands of Iraq (641), Armenia and Iran (642), and even as far as Transoxiana and Chinese Turkestan.[2]

Emergence of hereditary caliphates

Despite the military successes of the Muslims at this time, the political atmosphere was not without controversy. With Umar assassinated in 644, the election of Uthman as successor was met with gradually increasing opposition.[119] He was subsequently accused of nepotism, favoritism and of introducing reprehensible religious innovations, though in reality the motivations for such charges were economic.[119] Like Umar, Uthman too was then assassinated, in 656. Ali then assumed the position of caliph, although tensions soon escalated into what became the first civil war (the "First Fitna") when numerous companions of Muhammad, including Uthman's relative Muawiyah (who was assigned by Uthman as governor of Syria) and Muhammad's wife Aisha, sought to avenge the slaying of Uthman. Ali's forces defeated the latter at the Battle of the Camel, but the encounter with Muawiyah proved indecisive, with both sides agreeing to arbitration. Ali retained his position as caliph but had been unable to bring Mu'awiyah's territory under his command.[120] When Ali was fatally stabbed by a Kharijite dissenter in 661, Mu'awiyah was ordained as the caliph, marking the start of the hereditary Ummayad caliphate.[121] Under his rule, Mu'awiyah was able to conquer much of North Africa, mainly through the efforts of Muslim general Uqba ibn Nafi.[122]

There was much contention surrounding Mu'awiyah's assignment of his son Yazid as successor upon the eve of his death in 680,[123] drawing protest from Husayn bin Ali, grandson of Muhammad, and Ibn az-Zubayr, a companion of Muhammad. Both led separate and ultimately unsuccessful revolts, and Ummayad attempts to pacify them became known as the "Second Fitna". Thereafter, the Ummayad dynasty continued rulership for a further seventy years (with caliph Umar II's tenure especially notable[124]), and were able to conquer the Maghrib (699—705), as well as Spain and the Narbonnese Gaul at a similar date.[2]

The gains of the Ummayad empire were consolidated upon when the Abbasid dynasty rose to power in 750, with the conquest of the Mediterranean islands including the Balearics and Sicily.[2] The new ruling party had been instated on the wave of dissatisfaction propagated against the Ummayads, cultured mainly by the Abbasid revolutionary, Abu Muslim.[125][126] Under the Abbasids, Islamic civilization flourished. Most notable was the development of Arabic prose and poetry, termed by The Cambridge History of Islam as its "golden age."[127] This was also the case for commerce, industry, the arts and sciences, which prospered especially under the rule of Abbasid caliphs al-Mansur (ruled 754—775), Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786—809), and al-Ma'mun (ruled 809—813).[128]

Fragmentation

Baghdad was made the new capital of the caliphate (moved from the previous capital, Damascus) due to the importance placed by the Abbasids upon eastern affairs in Persia and Transoxania.[128] It was at this time, however, that the caliphate showed signs of fracture and the uprising of regional dynasties. Although the Ummayad family had been killed by the revolting Abbasids, one family member, Abd ar-Rahman I, was able to flee to Spain and establish an independent caliphate there, in 756. In the Maghreb region, Harun al-Rashid appointed the Arab Aghlabids as virtually autonomous rulers, although they continued to recognise the authority of the central caliphate. Aghlabid rule was short lived, as they were deposed by the Shiite Fatimid dynasty in 909. By around 960, the Fatimids had conquered Abbasid Egypt, building a new capital there in 973 called "al-Qahirah" (meaning "the planet of victory", known today as Cairo). Similar was the case in Persia, where the Turkic Ghaznavids managed to snatch power from the Abbasids.[129][130] Whatever temporal power of the Abbasids remained had eventually been consumed by the Seljuq Turks (a Muslim Turkish clan which had migrated into mainland Persia), in 1055.[128]

During this time, expansion continued, sometimes by military warfare, sometimes by peaceful proselytism.[2] The first stage in the conquest of India began just before the year 1000. By some 200 (from 1193—1209) years later, the area up to the Ganges river had been conquered. In sub-Saharan West Africa, it was just after the year 1000 that Islam was established. Muslim rulers are known to have been in Kanem starting from sometime between 1081 to 1097, with reports of a Muslim prince at the head of Gao as early as 1009. The Islamic kingdoms associated with Mali reached prominence later, in the 13th century.[2]

The Crusades and the Mongol invasions

Islamic conquest into Christian Europe spread as far as southern France. After the disastrous defeat of the Byzantines by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Christian Europe, at the behest of the Pope, launched a series of Crusades and captured Jerusalem. The Muslim general Saladin, however, regained Jerusalem at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, also having defeated the Shiite Fatimids earlier in 1171 upon which the Ayyubid dynasty had been conceived.[130][131]

The wave of Mongol invasions, which had initially commenced in the early 13th century under the leadership of Genghis Khan, marked a violent end to the Abbasid era. The Mongol Empire had spread rapidly throughout Central Asia and Persia: the Persian city of Isfahan had fallen to them by 1237. With the election of Khan Mongke in 1251, sights were set upon the Abbasid capital, Baghdad. Mongke's brother, Hulegu, was made the head of the Mongol army assigned with the task of subduing Baghdad. This was achieved at the Battle of Baghdad in 1258, which saw the Abbasids overrun by the superior Mongol army. The last Abbasid caliph, al-Musta'sim, was captured and killed; and Baghdad was ransacked and subsequently destroyed. The cities of Damascus and Aleppo fell shortly afterwards, in 1260. Any prospective conquest of Egypt was temporarily delayed due to the death of Mongke at around the same time.[130]

With Mongol conquest in the east, the Ayyubid dynasty ruling over Egypt had been surpassed by the slave-soldier Mamluks in 1250. This had been done through the marriage between Shajar al-Durr, the widow of Ayyubid caliph al-Salih Ayyub, with Mamluk general Aybak. Military prestige was at the center of Mamluk society, and it played a key role in the confrontations with the Mongol forces. After the assassination of Aybak, and the succession of Qutuz in 1259, the Mamluks challenged and decisively routed the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in late 1260. This signalled an adverse shift in fortunes for the Mongols, who were again defeated by the Mamluks at the Battle of Homs a few months later, and then driven out of Syria altogether.[130] With this, the Mamluks were also able to conquer the last of the crusader territories.

Rise of the Ottomans

The Seljuk Turks fell apart rapidly in the second half of the 13th century, especially after the Mongol invasions in Anatolia.[132] This resulted in the establishment of multiple Turkish principalities, known as beyliks. Osman I, the founder of the Ottoman dynasty, assumed leadership of one of these principalities (Söğüt) in 1281, succeeding his father Ertuğrul. Declaring an independent Ottoman emirate in 1299, Osman I led it to a series of consecutive victories over the Byzantine Empire. By 1331, the Ottomans had captured Nicea, the former Byzantine capital, under the leadership of Osman's son and successor, Orhan I.[133] Victory at the Battle of Kosovo against the Serbs in 1389 then facilitated their expansion into Europe. The Ottomans were firmly established in the Balkans and Anatolia by the time Bayezid I ascended to power in the same year, now at the helm of a swiftly growing empire.[134]

Further growth was brought to a sudden halt, as Bayezid I had been captured by Mongol warlord Timur (also known as "Tamerlane") in the Battle of Ankara in 1402, upon which a turbulent period known as the Ottoman Interregnum ensued. This episode was characterized by the division of the Ottoman territory amongst Bayezid I's sons, who submitted to Timurid authority. When a number of the territories recently conquered by the Ottomans regained independent status, potential ruin for the Ottoman Empire became apparent. However, the empire quickly recovered, as the youngest son of Bayezid I, Mehmed I, waged offensive campaigns against his other ruling brothers, thereby reuniting Asia Minor and declaring himself the new Ottoman sultan in 1413.[130]

At around this time the naval fleet of the Ottomans developed considerably, such that they were able to challenge Venice, traditionally a naval power. Focus was also directed towards reconquering the Balkans. By the time of Mehmed I's grandson, Mehmed II (ruled 1444—1446; 1451—1481), the Ottomans felt strong enough to lay siege to Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium. A decisive factor in this siege was the use of firearms and large cannons introduced by the Ottomans (adapted from Europe and improved upon), against which the Byzantines were unable to compete. The Byzantine fortress finally succumbed to the Ottoman invasion in 1453, 54 days into the siege. Mehmed II, entering the city victorious, renamed it to Istanbul. With its capital conceded to the Ottomans, the rest of the Byzantine Empire quickly disintegrated.[130] The future successes of the Ottomans and later empires would depend heavily upon the exploitation of gunpowder.[135]

Early modern period

Islam reached the islands of Southeast Asia through Indian Muslim traders near the end of the 13th century. Samudera Pasai and Peureulak (located at Aceh, Indonesia) is the first Southeast Asian port kingdom that convert to Islam circa 13th century. By the mid-15th century, Islam had spread from Sumatra to the nearby Malay peninsula Malacca and other islands from Java, Brunei to Ternate. In 15th century Demak Sultanate set the first Islamic rule on Java on the expense of weakening Hindu Majapahit empire. The conversion of the Malaccan ruler to Islam marked the start of the Malacca Sultanate. Although the sultanate managed to expand its territory somewhat, its rule remained brief. Portuguese forces captured Malacca in 1511 under the naval general Afonso de Albuquerque. With Malacca subdued, Aceh Sultanate and Brunei established themself as the centre of Islam in Southeast Asia. Brunei sultanate remains intact even to this day.[130] Throughout areas under its territorial dominance, Islam cemented itself within the cultures under the Muslim empire, resulting in the gradual conversion of the non-Muslim populations to Islam.[2] Such was not entirely the case in Spain, where a series of confrontations with the Christian kingdoms ended in the fall of Granada in 1492.[2]

In the early 16th century, the Shi'ite Safavid dynasty assumed control in Persia under the leadership of Shah Ismail I, upon the defeat of the ruling Turcoman federation Aq Qoyunlu (also called the "White Sheep Turkomans") in 1501. The Ottoman sultan Selim I quickly sought to repel Safavid expansion, challenging and defeating them at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. Selim I also deposed the ruling Mamluks in Egypt, absorbing their territories into the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Suleiman I (also known as Suleiman the Magnificent), Selim I's successor, took advantage of the diversion of Safavid focus against the Uzbeks on the eastern frontier and recaptured Baghdad, which had previously fallen under Safavid control. Despite this, Safavid power remained substantial, with their empire rivalling the Ottomans'. Suleiman I also advanced deep into Hungary following the Battle of Mohács in 1526 — reaching as far as the gates of Vienna thereafter, and signed a Franco-Ottoman alliance with Francis I of France against Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire 10 years later. Suleiman I's rule (1520—1566) signified the height of the Ottoman Empire, after which it fell into gradual decline.[130]

Meanwhile, the Delhi sultanate in the Indian subcontinent had been destroyed by the Timurid prince Babur in 1526, marking the start of the Mughal Empire — its capital in Agra. Babur's death some years later, and the indecisive rule of his son, Humayun, brought a degree of instability to Mughal rule. The resistance of the Afghani Sher Shah, through which a string of defeats had been dealt to Humayun, significantly weakened the Mughals. Just a year before his death, however, Humayun managed to recover much of the lost territories, leaving a substantial legacy for his son, the 13 year old Akbar (later known as Akbar the Great), in 1556. Under Akbar, consolidation of the Mughal Empire occurred through both expansion and administrative reforms.[130]

Formation of modern nation-states

By the end of the 19th century, all three Islamic areas of influence had declined due to internal conflict and were later destroyed by Western cultural influence and military ambitions. Following World War I, the remnants of the Ottoman Empire were parceled out as European protectorates or spheres of influence. The new states of Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan were formed from these protectorates. Alongside Arab nationalism the political movement known as Islamism was established.[citation needed] Oil reserves were discovered in Muslim-majority countries such as Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. After the second world war the state of Israel was established and a long conflict with Arab nations ensued. The world economy has become dependent on oil and this has enriched some Muslim-majority countries (such as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States) but continuing conflict has prevented other countries from benefitting fully from this natural resource. [citation needed]

Islamic civilization

Islam is not only a faith, but also a culture. Being the faith of a quarter of humanity, one can find a diversity of cultures, peoples who adhere to Islam, and the areas they inhabit, all of which make Islam a global culture.[136]

Art and architecture

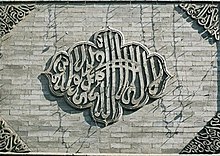

The term "Islamic art and architecture" denotes the works of art and architecture produced from the 7th century onwards by people (not necessarily Muslim) who lived within the territory that was inhabited by culturally Islamic populations.[137][138] Islamic art frequently adopts the use of geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as arabesque. Such designs are highly nonrepresentational, as Islam forbids representational depictions as found in pre-Islamic pagan religions. Despite this, there is a presence of depictional art in some Muslim societies, although this is not widespread. Another reason why Islamic art is usually abstract is to symbolize the transcendence, indivisible and infinite nature of God, an objective achieved by arabesque.[139] Arabic calligraphy is an omnipresent decoration in Islamic art, and is usually expressed in the form of Qur'anic verses. Two of the main scripts involved are the symbolic kufic and naskh scripts, which can be found adorning the walls and domes of mosques, the sides of minbars, and so on.[139]From between the eighth and eighteenth centuries, the use of glazed ceramics was prevalent in Islamic art, usually assuming the form of elaborate pottery.[140]

Perhaps the most important expression of Islamic art is architecture, particularly that of the mosque.[129] Through it the effect of varying cultures within Islamic civilization can be illustrated. The North African and Spanish Islamic architecture, for example, has Roman-Byzantine elements, as seen in the Alhambra palace at Granada, or in the Great Mosque of Cordoba. The role of domes in Islamic architecture has been considerable. Its usage spans centuries, first appearing in 691 with the construction of the Dome of the Rock mosque, and recurring even up until the 17th century with the Taj Mahal. And as late as the 19th century, Islamic domes had been incorporated into Western architecture.[141][142]

Science and technology

Muslim scientists made significant advances in mathematics and astronomy. The mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, from whose name the word algorithm derives, contributed significantly to algebra (which is named after his book, kitab al-jabr).[143] In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China many centuries before it was known in the West.[144][145] Iron was a vital industry in Muslim lands and was given importance in the Qur'an.[146][147] The knowledge of gunpowder was also transmitted from China to Islamic countries, through which it was later passed to Europe.[148] Knowledge of chemical processes (alchemy) and distilling (alcohol) also spread to Europe from the Muslim world. Numerous contributions were made in laboratory practices such as "refined techniques of distillation, the preparation of medicines, and the production of salts."[149] Advances were made in irrigation and farming, using technology such as the windmill. Crops such as almonds and citrus fruit were brought to Europe through al-Andalus, and sugar cultivation was gradually adopted by the Europeans.[150]

Muslim physicians contributed significantly to the field of medicine, including the subjects of anatomy and physiology: such as in the 15th century Persian work by Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn al-Faqih Ilyas entitled Tashrih al-badan ("Anatomy of the body") which contained comprehensive diagrams of the body's structural, nervous and circulatory systems; or in the work of the Egyptian physician Ibn al-Nafis, who proposed the theory of pulmonary circulation. Abu'l Qasim al-Zahrawi (also known as Abulcasis) contributed to the discipline of medical surgery with his Kitab al-Tasrif ("Book of Concessions"), a medical encyclopedia which was later translated to Latin and used in European and Muslim medical schools for centuries. Other medical advancements came in the fields of pharmacology and pharmacy.[151]

Islamic philosophy

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of Islamic culture."[152] Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims.[152] The Persian scholar Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (980-1037) had more than 450 books attributed to him. His writings were concerned with many subjects, most notably philosophy and medicine. His medical textbook was used as the standard text in European universities for centuries. His work on Aristotle was a key step in the transmission of learning from ancient Greeks to the Islamic world and the West. He often corrected the philosopher, encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of ijtihad. His thinking and that of his follower ibn Rushd (Averroes) was incorporated into Christian philosophy during the Middle Ages, notably by Thomas Aquinas.

Contemporary Islam

Commonly cited estimates of the Muslim population today range between 900 million and 1.5 billion people.[153] Only 18% of Muslims live in the Arab world; 20% are found in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 30% in the South Asian region of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and the world's largest single national Muslim community is in Indonesia. There are also significant Muslim populations in China, Europe, Central Asia, and Russia.

Many modern Muslims oppose the social restrictions on women enforced by some Islamic countries such as arranged marriages by male relatives, veiling, and limitations on movement. Halm states that these practices are rooted in patriarchal traditions of Near Eastern societies rather than in Islamic law.[154]

Political religious movements

The term Islamism describes a set of political ideologies derived from Islamic fundamentalism.[155] According to Ziauddin Sardar in Encyclopedia of the Future, "What distinguishes fundamentalism from traditional Islam is the fact that the state, and state power, are fundamental to its vision and represent a paramount fact of its consciousness. Thus, from a total, integrative, theocentric worldview and a God-centered way of life and thought, Islam is transformed into a totalitarian, theocratic world order that submits every human situation to arbitrary edicts of the state."[156] He thinks that although Islamic fundamentalism is the most "talked-about" and politicized aspect of contemporary Islam, it doesn't have any long-term future for several reasons, "largely because as a modern, concocted political dogma, it goes against the history and tradition of Islam".[156]

Islamist terrorism refers to acts of terrorism claimed by its supporters and practitioners to further the goals of Islam. It has heavily increased in prevalence in recent decades, and has become a contentious political issue in many nations. The validity of the Islamic justifications given for these acts is contested by many Muslims.[157][158]

Denominations

There are a number of Islamic religious denominations that are essentially similar in belief, but which nonetheless have significant theological and legal differences. The major schools of thought are Sunni and Shi'a; Sufism is generally considered to be a mystical inflection of Islam rather than a distinct school. According to most sources, present estimates indicate that approximately 85% of the world's Muslims are Sunni and approximately 15% are Shi'a.[159][160] There are a number of other Islamic sects which constitute a minority of Muslims today.

Sunni

Sunni Muslims constitute the largest group in Islam.[161] In Arabic, as-Sunnah literally means "principle" or "path". The Sunnah (the example of Muhammad's life) is the main pillar of Sunni doctrine, as recorded in the Qur'an and the hadith. Sunnis believe that the first four caliphs (leaders) of the Muslim community were the rightful successors to Muhammad.[162] They hold that since God did not specify the leaders of the Muslim community after Muhammad, the leaders had to be elected.[161] Sunnis recognize four major legal traditions, or madhhabs: Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, and Hanbali.[163] All four accept the validity of the others and a Muslim might choose any one that he or she finds agreeable, but other Islamic sects are believed to have departed from the majority by introducing innovations (bidah).[162] There are also several orthodox theological or philosophical traditions. The more recent Salafi movement, adherents of which often refuse to categorize themselves under any single legal tradition, sees itself as restorationist and claims to derive its teachings from the original sources of Islam.[164]

Shi'a

Shi'a Muslims, the second-largest branch of Islam, differ from the Sunni in rejecting the authority of the first three caliphs. Specifically, they believe that the Muslims had no right to elect the leader of the Khilafah.[165] They also disagree about the proper importance and validity of specific collections of hadith, and have their own legal tradition which is called Ja'fari jurisprudence.[166] The concept of Imamah, or leadership, plays a central role in Shi'a doctrine.[167] Shi'a Muslims view the Muslim community as primarily a spiritual community. They preferred to use the word "Imam" rather than "Caliph", believing that the leader of the Muslim community should be a spiritual leader first and a governor second.[168] They hold that leadership in a caliphate should not elected, but should instead consist of divinely appointed descendants of Muhammad through Ali and his progeny. They believe that their first Imam, Ali ibn Abu Talib, was explicitly appointed by Muhammad by divine command.[169]

Sufism

Sufism is a mystical form of Islam followed by some Muslims within both the Sunni and Shi'a sects.[170][171] Sufis generally believe that following Islamic law is only the first step on the path to perfect submission;[citation needed] they focus on the internal or more spiritual aspects of Islam, such as perfecting one's faith and subduing one's own ego.[172] Ghazali remarked that the Sufi life "cannot be learned but only achieved by direct experience, ecstasy, and inward transformation".[173] Most Sufi orders, or tariqas, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a.[171] However, there are some that are not so easily categorized, such as the Bektashi. Sufis are found throughout the Islamic world, from Senegal to Indonesia.[citation needed] Sufism has come under criticism by some Muslims for what they see as an apathy and passivity among Sufis brought about by an excessive focus on the after-life, and by the introduction of innovative beliefs and actions against the letter of Islamic law.[174]

Others

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the Kharijites. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites, which was itself divided into numerous sub-sects, is the Ibadi sect. Ibadism is distinguished from Shi'ism by its belief that the leader should be chosen solely on the basis of his faith and not on the basis of descent, and from the Sunni in its rejection of Uthman and Ali and strong emphasis on the need to depose unjust rulers. Ibadi Islam is noted for its strictness, but, unlike the Kharijites proper, Ibadis do not regard major sins as automatically rendering a Muslim an unbeliever. Most Ibadi Muslims live in Oman.[175][176]

Islam and other religions

The Qur'an contains both injunctions to respect other religions, and to fight and subdue unbelievers during war. The Qur'an claims that "it was restoring the pure monotheism of Abraham which had been corrupted in various, not clearly specified, ways by Jews and Christians."[177] (The charge of altering the scripture may mean no more than giving false interpretations to some passages, though in later Islam it was taken to mean that parts of the Bible are corrupt.)[178]

The modern understanding of tolerance, involving concepts of national identity and equal citizenship for men of different religions, was not considered a value by Muslims in pre-modern times because of being monotheists, Bernard Lewis and Mark Cohen state (See Toleration#Tolerance and Monotheism)[179] Traditionally Jews and Christians living in Muslim lands, known as dhimmis were allowed to "practice their religion, subject to certain conditions, and to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy" and guaranteed their personal safety and security of property, in return for paying the jizya (a per capita tax imposed on free adult males) to Muslims.[180] Dhimmis had an inferior status under Islamic rule. They had several social and legal disabilities such as prohibitions against bearing arms or giving testimony in courts in cases involving Muslims.[181] Many of the disabilities were highly symbolic. The most degrading one was the requirement of distinctive clothing, not found in the Qur'an or hadith but invented in early medieval Baghdad; its enforcement was highly erratic.[182] Persecution in the form of violent and active repression was rare and atypical.[183] They rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and they were mostly free in their choice of residence and profession.[184] The notable examples of massacre of Jews and Christians include the killing or forcibly convertion of them by the rulers of the Almohad dynasty in Al-Andalus in the 12th century.[185] Notable examples of the cases where the choice of residence was taken away from them includes confining Jews to walled quarters (mellahs) in Morocco beginning from the 15th century and especially since the early 19th century.[186] Most conversions were voluntary and happened for various reasons. However, there were some forced conversions in the 12th century under the Almohad dynasty of North Africa and al-Andalus as well as in Persia.[187] The enforcement of the laws of the dhimma was widespread in the Muslim world until the mid-nineteenth century, when the Ottoman empire significantly relaxed the restrictions placed on its non-Muslim residents. These relaxations occurred gradually as part of the Tanzimat reform movement, which began in 1839 with the accession of the Ottoman Sultan Abd-ul-Mejid I.[188]

Related faiths

The Yazidi, Druze, Bábí, Bahá'í, Berghouata and Ha-Mim religions either emerged out of an Islamic milieu or have certain beliefs in common with Islam. Nearly always those religions were also influenced by traditional beliefs in the regions where they emerged, but consider themselves independent religions with distinct laws and institutions. The last two religions no longer have any followers. Sikhism's holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, contains some writings by Muslim figures, as well as by Sikh and Hindu saints.[189]

Criticism of Islam

The earliest surviving written criticisms of Islam are to be found in the writings of Christians like John of Damascus (born c. 676), who claimed, among other things, that an Arian monk influenced Muhammad.[190] In the medieval period, Muslims like the poet Al-Ma'arri adopted a critical approach to their own religion.[191] The Jewish philosopher Maimonides contrasted Islamic views of morality to the Jewish approach that he himself elaborated.[192] Medieval Christian ecclesiastical writers emphatically denied the validity of Islamic beliefs, portraying Muhammad as possessed by Satan.[193] In the 19th century, the Orientalist scholar William Muir wrote harshly about the Qu'ran.[194]

In recent years, Islam has been the subject of criticism and controversy, and is often viewed with considerable negativity in the West.[195] Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, have all been subject to both criticism and vilification. Carl Ernst, a scholar in Islamic studies, has dismissed some of this as a product of Islamophobia.[196] Some areas of critique include the issue of Islam's tolerance (or intolerance) of criticism itself, and the treatment accorded apostates in Islamic law.[197] Other criticism focuses on the life of Muhammad,[198] the authenticity and morality of the Qu'ran,[199] as well as the status of women in Islamic law and practice.[200] Notable contemporary critics include Robert Spencer,[201] Daniel Pipes,[202] Ibn Warraq,[203] and Bat Ye'or.[204]

Responses to the critics have come from many corners. According to Islamic studies professor Montgomery Watt, a number of the criticisms directed against Islam and Muhammad surfaced while Islam was considered the enemy of Christendom, and was thus demonized.[205] Norman Daniel adds that such Christian polemic formed the backbone of academic study of Islam, resulting in the prevalence of myths about Islam in the West.[206] Muslim scholars like Muhammad Mohar Ali argue against the criticism directed against Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, responding to theories such as claims of discrepancies in the Qur'an or of Judeo-Christian influences on Muhammad.[207] Other notable Muslim apologists include Ahmed Deedat,[208] Yusuf al-Qardawi[citation needed] and Yusuf Estes.[209]

See also

Notes

- ^ Teece (2005), p.10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Islam", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ Ghamidi (2001): Sources of Islam

- ^ Esposito (1996), p.41

- ^ "If…they [Christians] mean that the Qur'an confirms the textual veracity of the scriptural books which they now possess—that is, the Torah and the Gospels—this is something which some Muslims will grant them and which many Muslims will dispute. However, most Muslims will grant them most of that." Ibn Taymiyya cited in Accad (2003)

- ^ Esposito (1998), p12 - Esposito (2002b), pp.4-5 - Peters (2003), p.9

- ^ a b "Muhammad", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ Gregorian (2003), p.ix

- ^ Esposito (2002b), p.21

- ^ "Muslims in Europe: Country guide". BBC News. 2005-12-23. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Religion In Britain". Office for National Statistics. 2003-02-13. Retrieved 2006-08-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Islam

- ^ Emran Qureshi, Michael Anthony Sells (2003), p.30

- ^

as quoted from the Encyclopaedia of Islam Online, the other two instances beingQuran

andQuran Quran - ^

as quoted from the Encyclopaedia of Islam Online, the other two instances beingQuran

andQuran Quran - ^ i.e. In

andQuran Quran - ^ Watton (1993), "Introduction"

- ^ Encyclopedia of Christianity (Ed. Erwin Fahlbusch), Qur'an

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 30:30]

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Religion, Islam

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 22:78]

- ^ "Tahrif", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ As related in a famous tradition ascribed to Muhammad (see Sahih Muslim 001.0001)

- ^ "Iman", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ "tawhid." Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, 2007

- ^ Ruth Marie Griffith, Barbara Dianne Savage (2006), p.248

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam, Allah

- ^ Encyclopedia of Christianity (Ed. Erwin Fahlbusch), Islam and Christianity, p.759, vol 2

- ^ F.E. Peters(2003), p.4

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 112:1]

- ^ a b c Teece (2003) pp. 12, 13

- ^ Turner, C. (2006) p. 42

- ^ Peters (1991): "Few have failed to be convinced that what is in our copy of the Quran is, in fact, what Muhammad taught, and is expressed in his own words... To sum this up: the Quran is convincingly the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation."

- ^ a b "Qur'an", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ "Tafsir", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Tarek Mahfouz(2006), p.35

- ^ What should be done with a Mushaf (a copy of the Qur’an) that has within it errors (typos) or is ripped? How is a torn Mushaf disposed of?

- ^ Scott Alan Kugle (2006), p.47

- ^ John L. Esposito, Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad (2000), p.275

- ^ Esposito (1998), p.12 - Esposito (2002b), pp.4-5 - Peters (2003), p.9

- ^ The term Qur'an was invented and first used in the Qur'an itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation, that are discussed in Quran#Etymology cf. "Qu'ran", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- ^ "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ [Quran 18:110]

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p.666

- ^ "Sunnah", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ "Hadith", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 21:19])

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 35:1]

- ^ "Djinn", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 45:5] quoted in Sell (2004) p. 228

- ^ "Malā'ika", Encyclopedia of Islam Online.

- ^ Sell (2004) p. 228

- ^ [Quran 74:38]

- ^ Esposito (2003), p.264

- ^ Ibn Sīnā, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sīnā, known in the West as Avicenna, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ "Resurrection", The New Encyclopedia of Islam (2003), p.383

- ^ "Qiyama", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World (2004), p.565

- ^ "Paradise", "Heaven", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ^ Smith (2006), p.89

- ^ "Heaven", The Columbia Encyclopedia (2000)

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 9:51]

- ^ a b Farah pp. (2003) 119-122

- ^ Patton (1900) p. 130

- ^ Husain Kassim, Islam, Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals

- ^ Farah (1994), p.135

- ^ a b Kobeisy (2004), pp.22-34

- ^ See Qur'an [Quran 29:40]

- ^ a b c Hedáyetullah (2006), pp.53-55

- ^ Heniz Halm (Ed. Erwin Fahlbusch), Encyclopedia of Christianity, Islam, vol2, p.752

- ^ Ridgeon (2003), p.258

- ^ "Zakat", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Jonathan E. Brockopp, Tamara Sonn, Jacob Neusner(2000), p.140

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 150

- ^ Jonsson(2006), p.244

- ^ "Zakat Calculator". 2006-10-16. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ^ Fasting, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ^ a b Farah (1994), pp.144-145

- ^ Esposito, Islam the straight path (extended edition), p.91

- ^ Allameh Tabatabaei, Islamic teachings, p.211, p.213

- ^ Khan (2006), p.54

- ^ For whom fasting is mandatory, USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 2:184]

- ^ "Islam." Encyclopædia Britannica, Fasting section.

- ^ Farah (1994), pp.145-147

- ^ a b Hoiberg (2000), pp.237-238

- ^ Goldschmidt (2005), p.48

- ^ a b "Shari'ah." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 7 February 2007 [1]

- ^ Werner F. Menski(2006), p.290, see the quote from El Alami and Hinchcliffe

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Ḥadd

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, S̲H̲arīa

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 150

- ^ Weiss (2002) p. xvii

- ^ Weiss (2002) p. 3, 161

- ^ Weiss (2002) p. 162

- ^ "Masdjid", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ Sunan al-Tirmidhi 1513; Sahih Muslim 2020; Sahih Bukhari 6234; Sahih Bukhari 6224

- ^ a b c d Ghamidi (2001):Customs and Behavioral Laws

- ^ cf. Sahih Muslim 257; Sahih Muslim 258; Sahih Muslim 252; Sunan Abu Da'ud 45, and:

; [Quran 4:43]; [Quran 5:6]Quran - ^ Ghamidi (2001):Various types of the prayer. Also refer to Sahih Bukhari 1254; Sahih Muslim 943

- ^ Esposito (2002b), p.111

- ^ Ghamidi (2001): The Dietary Laws

- ^ a b c F.E.Peters(2003), p.67

- ^ Adil (2002), p.288

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Islam, Taʾrīk̲h̲

- ^ Sunan Abu Da'ud 1134

- ^ Esposito (2003), p.93

- ^ "Djihād", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ a b c d Peters (1977), pp.3—5

- ^ Esposito (2002a), p.26

- ^ Encyclopedia of Christianity (Ed. John Bowden), Islam and Christianity

- ^ The Doctrine of Jihad: An Introduction, Noor Mohammad, Journal of Law and Religion, Vol. 3, No. 2. (1985), pp. 381-397.

- ^ Maududi. "Human Rights in Islam, Chapter Four". Retrieved 2006-01-09.

- ^ Ghamidi (2001): The Islamic Law of Jihad

- ^ "BBC - Religion & Ethics - Jihad: The internal Jihad". Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ a b Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.57

- ^ Hourani (2003), p.22

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.74

- ^ a b Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.67

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), pp. 68-72

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.72

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.79

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.80

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.92

- ^ Lewis (1993), p.84

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p.105

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 2B (1977), pp.661-663

- ^ a b c "Abbasid Dynasty", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ^ a b "Islam", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Applied History Research Group, University of Calagary, "The Islamic World to 1600", Last accessed January 1, 2007

- ^ Esposito (2000), p.57

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A (1977), p. 263

- ^ Koprulu, Leiser (1992) p. 109

- ^ Koprulu, Leiser (1992) p. 111

- ^ Armstrong (2000) p.116

- ^ Islam, Encyclopedia of the Future

- ^ Ettinghausen (2003), p.3

- ^ "Islamic Art and Architecture", The Columbia Encyclopedia (2000)

- ^ a b Madden (1975), pp.423-430

- ^ Mason (1995) p.1

- ^ Grabar, O. (2006) p.87

- ^ Ettinghausen (2003), p.87

- ^ Ron Eglash(1999), p.61

- ^ Toby E. Huff(2003), p.74

- ^ The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia(2004), p.143

- ^ Qur'an [Quran 57:25]

- ^ John M. Hobson(2004), p.130

- ^ William D. Phillips(1992), p.76

- ^ Trevor Harvey Levere(2001) , p.6

- ^ Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and power: the place of sugar in modern history, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986, pp.23-29.

- ^ Turner, H. (1997) pp. 136—138

- ^ a b "Islamic Philosophy", Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998)

- ^ "Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ Heniz Halm, Encyclopedia of Christianity (Ed. Erwin Fahlbusch), Islam, vol2, p.753

- ^ Tore Kjeilen. "Islamism". Encyclopedia of the Orient. LexicOrient. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ a b "Islam", Encyclopedia of Future

- ^ Harun Yahya. "Islam Denounces Terrorism". Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ "Muslims Against Terrorism". Muslims Against Terrorism. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ Esposito (2002b), p.2

- ^ "Sunni and Shia Islam". Country Studies. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ a b Britannica Encyclopedia, Sunnite

- ^ a b The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.306

- ^ Britannica Encyclopedia, Shariah

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.275

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Shi'ite

- ^ Seyed Hossien Nasr (1994), p.466

- ^ F.E.Peters(2003), p.136-137

- ^ F.E.Peters(2003), p.139-140

- ^ F.E.Peters(2003), p.133

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.302

- ^ a b Library of Congress Federal Research Division, Afghanistan: A Country Study , 2001, p.150

- ^ Jacob Neusner(2003), p.150-151

- ^ F.E.Peters (2003), p.249

- ^ Bryan S. Turner(1998), p.145

- ^ John Alden Williams(1994), p.173

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, al-Ibāḍiyya

- ^ Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1, (1977) pp.43-44

- ^ Watt (1974), p.116

- ^ Lewis (1997), p.321; (1984) p.65; Cohen (1995), p.xix

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp.10,20

- ^ Lewis (1987), p. 9, 27

- ^ Lewis (1999), p.131

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp.8,62

- ^ Lewis (1999), p.131

- ^ Lewis (1984), p. 52; Stillman (1979), p.77

- ^ Lewis (1984), p. 28

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp.17,18,94,95; Stillman (1979), p.27

- ^ "1839–61", The Encyclopedia of World History Online

- ^ Parrinder (1971), p.259

- ^ Sahas (1997), pp.76-80

- ^ Warraq (2003), p. 67

- ^ Novak (February 1999)

- ^ Gabriel Oussani. "Mohammed and Mohammedanism". Catholic Encyclopedia (1910 version). Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- ^ Toby Lester (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". The Atlantic Monthly.

- ^ Ernst (2004), p.11

- ^ Ernst (2004), p.11

- ^ Bostom, Andrew (July 21, 2003). "Islamic Apostates' Tales - A Review of Leaving Islam by Ibn Warraq". FrontPageMag.

- ^ Warraq (2000), p. 103

- ^ Ibn Warraq (2002-01-12). "Virgins? What virgins?". Special Report: Religion in the UK. The Guardian.

- ^ Timothy Garton Ash (10-05-2006). "Islam in Europe". The New York Review of Books.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Andrew Bostom (10-15-2006). "Scrutinizing Muhammad's example and teachings". The Washington Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lockman (2004), p. 254

- ^ Rippin (2001), p. 288

- ^ Cohen (1995), p. 11

- ^ Watt (1961) p. 229

- ^ Seibert (1994) pp. 88-89

- ^ Muhammad Mohar Ali. "The Biography of the Prophet and the Orientalists".

- ^ Westerlund (2003)

- ^ Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu (11-17-2003). "Ramadan Awareness Event Designed To Debunk Negative Images". Advance, University of Connecticut.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Accad, Martin (2003). "The Gospels in the Muslim Discourse of the Ninth to the Fourteenth Centuries: An Exegetical Inventorial Table (Part I)". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 14 (1). ISSN 0959-6410.

- Adil, Hajjah Amina (2002). Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam. Islamic Supreme Council of America. ISBN 978-1930409118.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Al-Juwayni, Imam Al-Haramayn (2001). A Guide to Conclusive Proofs for the Principles of Belief. Ithaca. ISBN 978-1859641576.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Armstrong, Karen (2000). Islam: A Short History. Modern Library. ISBN 978-0679640400.

- Brockopp, Jonathan (2000). Judaism and Islam in Practice: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 0415216737.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Cohen, Mark R. (1995). Under Crescent and Cross. Princeton University Press; Reissue edition. ISBN 978-0691010823.

- Eglash, Ron (1999). African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2614-0.

- Ernst, Carl (2004). Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5577-4.

- Esposito, John (1996). Islam and Democracy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510816-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Esposito, John (2000a). Muslims on the Americanization Path?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513526-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Esposito, John (2000b). Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. 978-0195107999.

- Esposito, John (2002a). Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195168860.

- Esposito, John (2002b). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515713-3.

- Esposito, John (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512558-4.

- Ettinghausen, Richard (2003). Islamic Art and Architecture 650-1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300088694.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Eyre, Edward (1934). European Civilization: Its Origin and Development. Oxford University Press.

- Farah, Caesar (1994). Islam: Beliefs and Observances (5th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0812018530.

- Farah, Caesar (2003). Islam: Beliefs and Observances (7th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0764122266.

- Fouracre, Paul (ed.) (2006). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521362917.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Ghamidi, Javed (2001). Mizan. Dar al-Ishraq. OCLC 52901690.

- Goldschmidt, Jr., Arthur (2005). A Concise History of the Middle East (8th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813342757.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Grabar, Oleg (2006). Islamic Art And Beyond. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0860789225.

- Gregorian, Vartan (2003). Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-3282-1.

- Griffith, Ruth Marie (2006). Women and Religion in the African Diaspora: Knowledge, Power, and Performance. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801883709.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hedayetullah, Muhammad (2006). Dynamics of Islam: An Exposition. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1553698425.

- Hobson, John M. (2004). The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521547245.

- Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India. Encyclopaedia Britannica (UK) Ltd. ISBN 978-0852297605.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Holt, P. M. (1977a). Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291364.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Holt, P. M. (1977b). Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291372.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hourani, Albert (2003). A History of the Arab Peoples. Belknap Press; Revised edition. ISBN 978-0674010178.